Virtual Screening of Natural Product Databases: A Modern Protocol for Accelerating Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on establishing a robust virtual screening protocol for natural product databases.

Virtual Screening of Natural Product Databases: A Modern Protocol for Accelerating Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on establishing a robust virtual screening protocol for natural product databases. It covers the foundational principles of virtual screening, explores the unique value and challenges of natural product chemical space, and details the application of both traditional and cutting-edge AI-driven methodologies. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to enhance success rates and dedicates a significant portion to the essential steps of experimental validation and comparative analysis of different techniques. By synthesizing the latest trends and validated case studies, this protocol aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to efficiently identify novel bioactive compounds from nature's vast repository.

Laying the Groundwork: Natural Products and Virtual Screening Fundamentals

The Enduring Role of Natural Products in Modern Drug Discovery

Natural Products (NPs) have served as a cornerstone of medicinal therapy for thousands of years and continue to be an invaluable source for novel therapeutic agents in modern drug discovery pipelines [1]. Well-known examples include the anticancer agent paclitaxel, originally extracted from the Pacific yew tree, and digoxin, a heart medicine derived from the foxglove plant [1]. The evolutionary optimization of these compounds for biological interactions makes them particularly attractive for targeting human diseases. Contemporary drug discovery leverages computational methodologies to systematically mine the chemical space of NPs, with virtual screening emerging as a critical protocol for identifying promising candidates from vast digital libraries in a cost- and time-efficient manner [2]. This application note details an integrated protocol for the virtual and experimental screening of natural product databases, providing a structured framework for researchers to identify novel bioactive compounds.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential databases, software, and resources that form the core toolkit for conducting virtual screening of natural products.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for NP Virtual Screening

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features / Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| SuperNatural 3.0 [1] | Compound Database | A freely accessible database of natural compounds. | Contains 449,058 unique compounds; includes physicochemical properties, vendor information, toxicity, and predicted mechanism of action. |

| ZINC20 [3] [2] | Compound Database | A public repository of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. | A primary source for obtaining 3D structures of purchasable natural products (e.g., 187,119 compounds in a recent study). |

| ChEMBL [1] | Bioactivity Database | A database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. | Provides curated data on molecular interactions and bioactivities, used for predicting mechanisms of action. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [2] | Protein Structure Database | Repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids. | Source of crystallographic structures for molecular docking targets (e.g., PDB IDs: 5NM4, 5P9I, 3LFF). |

| AutoDock Vina [2] | Docking Software | Performs molecular docking to predict ligand-receptor binding poses and affinities. | Widely used for virtual screening; calculates binding energies (in kcal/mol). |

| pkCSM [2] | Predictive Tool | Online server for predicting ADME-Tox (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties. | Used to filter compounds for favorable drug-like behavior and low toxicity. |

| RDKit [1] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Open-source software for cheminformatics and machine learning. | Used for handling chemical information, calculating molecular fingerprints, and similarity searching. |

Integrated Virtual and Experimental Screening Protocol

This protocol outlines a robust pipeline for identifying and validating bioactive natural products, from in silico screening to initial in vitro cytotoxicity assessment, as demonstrated in recent studies [3] [2].

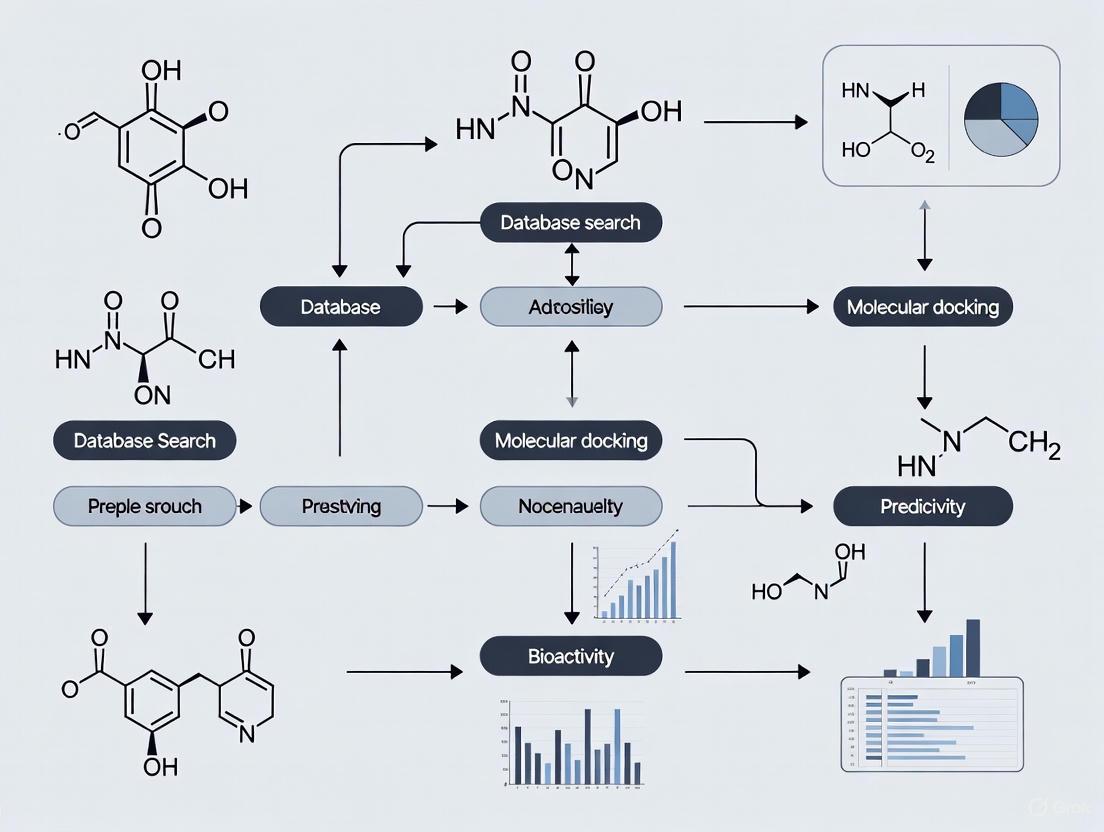

The diagram below illustrates the integrated screening pipeline, showing the logical flow from target selection to lead identification.

Protocol Steps

Step 1: Target Selection and Preparation

- Objective: Select and prepare relevant protein targets for docking.

- Procedure:

- Systematic Review: Conduct a literature review using databases like PubMed/Medline and Scopus to identify and select target proteins strongly implicated in the disease pathology. Apply inclusion criteria (e.g., peer-reviewed studies, in silico docking data) [2].

- Structure Acquisition: Retrieve high-resolution crystallographic structures of the selected targets from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [2].

- Protein Preparation: Prepare the protein structures using software such as MGLTools. This involves:

- Removing water molecules and co-crystallized ligands.

- Adding hydrogen atoms and Kollman charges.

- Defining the active site with a grid box for docking.

Step 2: Natural Product Library Curation

- Objective: Assemble a diverse and readily available library of natural products.

- Procedure:

- Database Mining: Download structures of natural products from databases like ZINC20 or SuperNatural 3.0 [3] [1].

- Compound Preparation: Prepare the ligands for docking using tools like Open Babel. Steps include:

- Generating 3D coordinates.

- Adding hydrogens and optimizing protonation states at physiological pH (e.g., 7.0).

- Converting file formats to be compatible with docking software.

Step 3: Virtual Screening via Molecular Docking

- Objective: Identify top-binding compounds through computational docking.

- Procedure:

- Method Validation (Redocking): Validate the docking protocol by extracting the native ligand from the PDB file, re-docking it into the prepared active site, and calculating the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD). An RMSD value < 2.0 Å is considered acceptable [2].

- Large-Scale Docking: Dock the entire prepared natural product library against each prepared target protein using software like AutoDock Vina [3] [2].

- Hit Identification: Rank all compounds based on their predicted binding energy (in kcal/mol). Select the top 1-15 compounds per target for further analysis, prioritizing those with superior binding energy compared to known controls [3] [2].

Step 4: In Silico ADME-Tox Profiling

- Objective: Predict the drug-likeness and toxicity of the top hits.

- Procedure:

- Property Prediction: Submit the top candidate structures to the pkCSM server or similar tools [2].

- Key Parameter Evaluation: Analyze predicted properties including:

- Intestinal absorption

- Skin permeability

- Total clearance

- AMES toxicity (mutagenicity)

- Hepatotoxicity

- Maximum tolerated dose (human)

- Compound Filtering: Filter out compounds with unfavorable ADME-Tox profiles or proceed to structural optimization if activity is high but toxicity is predicted.

Step 5: Bioisosteric Optimization (If Required)

- Objective: Improve the ADME-Tox profile of promising hits without compromising binding affinity.

- Procedure:

- Fragment Identification: Identify molecular fragments associated with predicted toxicity.

- Bioisosteric Replacement: Use software like MB-Isoster to replace these fragments with bioisosteric groups that have similar physicochemical properties but lower predicted toxicity [2].

- Re-evaluation: Re-dock the optimized compounds and re-run ADME-Tox predictions to confirm improved profiles.

Step 6: Experimental Validation

- Objective: Confirm the in vitro bioactivity of the computationally selected hits.

- Procedure:

- Compound Acquisition: Purchase the selected top natural product candidates from commercial vendors [3] [1].

- Cytotoxicity Assay: Evaluate the cytotoxicity of the compounds against relevant disease cell lines (e.g., MCF-7, MDA-MB-468 for breast cancer) and a normal cell line (e.g., CCD-1064Sk fibroblasts) [3].

- Data Analysis: Calculate potency (e.g., IC50 values) and Selectivity Indices (SI) to identify compounds that are potent against disease cells but less toxic to normal cells. A clear correlation between more negative docking scores and enhanced cytotoxicity is a key indicator of the virtual screen's predictive value [3].

Representative Data and Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR)

A recent study screening 187,119 natural compounds against breast cancer targets yielded the following results, which can be used as a benchmark for expected outcomes [3].

Table 2: Representative Virtual and Experimental Screening Data against Breast Cancer Targets

| Compound ID | Target Protein | Binding Affinity (kcal/mol) | Cytotoxicity (Cell Line) | Selectivity Index (SI) | Key Structural Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C3 | Mutant PIK3CA-E545K | ≤ -8.6 | Potent (MCF-7) | ≥ 2.0 | Planarity, hydrophobic substituents |

| C4 | Overexpressed ESR1 | ≤ -8.6 | Potent (MCF-7) | ≥ 2.0 | Planarity, hydrophobic substituents |

| C5 | Mutant ERBB4-Y1242C | ≤ -8.6 | Potent (MCF-7) | ≥ 2.0 | Planarity, hydrophobic substituents |

| C6 | Overexpressed EGFR | ≤ -8.6 | Potent (MDA-MB-468) | ≥ 2.0 | Planarity, hydrophobic substituents |

| C7 | Overexpressed ERBB2 | ≤ -8.6 | Potent (SK-BR-3) | ≥ 2.0 | Planarity, hydrophobic substituents |

| C10 | Multiple Targets | ≤ -8.6 | Potent | ≥ 2.0 | Planarity, hydrophobic substituents |

Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Analysis: The study identified that molecular planarity and the presence of hydrophobic substituents were key structural drivers of high binding affinity and cytotoxic activity [3]. This information is critical for guiding the selection of compounds from databases and for planning future chemical optimization.

Statistical Analysis of Experimental Results

When comparing experimental results, for instance, the cytotoxicity of hits against different cell lines or versus a control, proper statistical analysis is mandatory. The t-test is a fundamental method for determining if the difference between two sets of data is statistically significant.

- Formulating Hypotheses: The Null Hypothesis (H₀) states there is no difference between the two means being compared. The Alternative Hypothesis (H₁) states that a significant difference does exist [4].

- Choosing the Right Test: First, perform an F-test to compare the variances of the two data sets. If the p-value from the F-test is greater than the significance level (α=0.05), equal variances can be assumed [4].

- Executing the t-test: Use software like Microsoft Excel, Google Sheets (with the XLMiner ToolPak), or specialized statistical packages to perform a two-sample t-test.

- Key Outputs to Evaluate:

- t Statistic: The calculated value of the t-test.

- P-value: The probability that the observed difference occurred by chance. A p-value < 0.05 is typically considered statistically significant [4] [5].

- t Critical Value: The threshold value from the t-distribution. If the absolute value of the t Statistic is greater than the t Critical value, the null hypothesis can be rejected [4].

- Key Outputs to Evaluate:

- Presentation of Results: In publications, results should be presented clearly, often in a table format. Provide the sample size (n), a representative value (mean ± standard deviation or median with quartiles), the difference between groups with its 95% confidence interval (CI), and the exact p-value to three decimal places [5].

Natural products (NPs) have been the most significant source of bioactive compounds for medicinal chemistry throughout history [6]. For instance, from 1981 to 2019, 64.9% of the 185 small molecules approved to treat cancer were unaltered NPs or synthetic drugs containing a NP pharmacophore [6]. The drug discovery process for NPs has been transformed by computational approaches, with computer-aided drug design (CADD) potentially reducing costs and development time [6]. Virtual screening (VS) techniques, including both structure-based (SBVS) and ligand-based (LBVS) methods, have demonstrated remarkable efficiency, with molecular docking achieving a 34.8% hit identification rate for novel inhibitors of protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B compared to just 0.021% for high-throughput screening (HTS) [6].

Natural product databases serve as crucial resources in CADD, enabling researchers to identify potential hit molecules through various virtual screening techniques [6] [7] [8]. These databases facilitate the training of artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms and the development of predictive quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models [6]. Over the past two decades, a proliferation of NP databases has occurred, with approximately 120 databases published between 2000 and 2019 [6]. This application note explores two significant contributors to this landscape—LANaPDB and COCONUT—detailing their features, applications, and protocols for their effective utilization in virtual screening protocols for natural product research.

Database Profiles and Comparative Analysis

Latin American Natural Products Database (LANaPDB)

LANaPDB represents a collective effort from several Latin American countries to unify chemical information on natural products from this biodiversity-rich geographical region [6] [9]. The database was created in response to the extraordinary biodiversity of Latin America, which enables the identification of novel NPs [6]. The initial 2023 version unified information from six countries and contained 12,959 chemical structures [6] [9] [10]. A 2024 update expanded its scope to include 13,578 compounds from ten databases across seven Latin American countries [7].

The structural classification of LANaPDB compounds reveals a distinctive profile dominated by terpenoids (63.2%), followed by phenylpropanoids (18%) and alkaloids (11.8%) [6] [9]. Analysis of pharmaceutical properties indicates that many LANaPDB compounds satisfy drug-like rules of thumb for physicochemical properties [6]. The chemical space covered by LANaPDB completely overlaps with COCONUT and, in some regions, with FDA-approved drugs [6] [9] [10]. LANaPDB is publicly accessible and can be downloaded from GitHub [7] [10].

Collection of Open Natural Products (COCONUT)

COCONUT is one of the largest open natural product databases available without restrictions [11] [12]. Launched in 2021 and significantly updated in 2024 (COCONUT 2.0), it serves as an aggregated dataset of elucidated and predicted NPs collected from open sources [11] [13]. The database was created in response to the lack of a comprehensive online resource regrouping all known NPs in one place [11].

As of its 2020 release, COCONUT contained 406,076 unique "flat" NPs (without stereochemistry) and a total of 730,441 NPs with preserved stereochemistry when available [11]. The database is assembled from 53 diverse data sources and undergoes rigorous quality control and curation procedures [11]. Each NP is assigned a unique identifier (CNP prefix with 7 digits) and an annotation quality score from 1 to 5 stars based on metadata completeness [11]. COCONUT provides comprehensive search capabilities and is freely accessible at https://coconut.naturalproducts.net [11] [13] [12].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of LANaPDB and COCONUT Databases

| Feature | LANaPDB | COCONUT |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Latin American natural products | Universal collection of open natural products |

| Initial Release | 2023 | 2021 |

| Latest Update | 2024 (version 2) | 2024 (version 2.0) |

| Number of Compounds | 13,578 (2024 update) | 406,076 unique "flat" structures; 730,441 with stereochemistry |

| Data Sources | 10 databases from 7 Latin American countries | 53 various data sources and literature sets |

| Structural Classification | Terpenoids (63.2%), phenylpropanoids (18%), alkaloids (11.8%) | Classified using ClassyFire hierarchical system |

| Access | Free download via GitHub | Free access via web interface; bulk download available |

| Unique Features | Geographic specificity; chemical multiverse analysis | Annotation quality scoring; community curation; user submissions |

Table 2: Chemical Space and Pharmaceutical Properties Comparison

| Parameter | LANaPDB | COCONUT | FDA-Approved Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Space Overlap | Overlaps completely with COCONUT and partially with FDA drugs | Overlaps completely with LANaPDB | Partial overlap with LANaPDB in specific regions |

| Drug-Like Properties | Many compounds satisfy drug-like rules of thumb | Wide range of properties; NP-likeness score provided | Reference standard for drug-like properties |

| Molecular Complexity | Moderate to high (especially terpenoids) | Wide range, from simple to highly complex | Generally moderate |

| Structural Diversity | Regionally biased but structurally diverse | Extremely diverse due to multiple sources | Therapeutically optimized but less diverse |

Virtual Screening Workflow Using Natural Product Databases

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive virtual screening workflow integrating natural product databases:

Diagram 1: Comprehensive Virtual Screening Workflow for Natural Product Databases. This workflow integrates multiple NP databases and combines various screening approaches to identify promising bioactive compounds.

Protocols for Database Utilization in Virtual Screening

Protocol 1: Database Acquisition and Preprocessing

Materials and Software Requirements

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item | Specification | Application/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| LANaPDB | Version 2.0 (13,578 compounds) | Region-specific natural product diversity |

| COCONUT | Version 2.0 (>400,000 compounds) | Comprehensive natural product coverage |

| Cheminformatics Suite | RDKit, CDK, or ChemAxon | Structure manipulation and descriptor calculation |

| Scripting Environment | Python 3.8+ with pandas, numpy | Data processing and analysis |

| Structure Visualization | PyMOL, Chimera, or similar | 3D structure analysis and preparation |

| Database Management | MongoDB or SQL database | Efficient storage and querying of compound data |

Procedure

Database Acquisition

- Download the complete LANaPDB dataset from the GitHub repository (https://github.com/alexgoga21/LANaPDB-version-2/tree/main) [7].

- Access COCONUT data via the web interface (https://coconut.naturalproducts.net) or download bulk data in SDF or CSV format [11] [12].

- For COCONUT, utilize the REST API for programmatic access and integration into computational workflows [11].

Structure Curation and Standardization

- Implement a quality control pipeline to check structures for size (between 5-210 heavy atoms), connectivity, correct valence, and bond types [11].

- Standardize tautomers and ionization states following established chemical structure curation pipelines, such as the ChEMBL protocol [11].

- For COCONUT, note that stereochemistry is preserved when available, though unification is performed without stereochemistry due to inconsistent representation across sources [11].

Molecular Descriptor Calculation

- Compute a comprehensive set of molecular descriptors including molecular weight, logP, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, topological polar surface area, and rotatable bonds [6] [11].

- Generate molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP, MAP4) for similarity searching and machine learning applications [6].

- For NPs with sugar moieties, consider generating deglycosylated structure representations using tools like the Sugar Removal Utility to study aglycon effects [11].

Protocol 2: Chemical Space Visualization and Analysis

Materials and Software Requirements

- Dimensionality reduction algorithms (PCA, t-SNE, UMAP)

- Molecular fingerprint generation tools

- Chemical space visualization platforms (TMAP, ChemPlot)

- Programming environment with scikit-learn, matplotlib, or specialized cheminformatics libraries

Procedure

Chemical Space Mapping

- Generate multiple chemical representations using at least two different fingerprint types (e.g., ECFP and MAP4) to create a "chemical multiverse" [6].

- Apply dimensionality reduction techniques (PCA, t-SNE) to project high-dimensional fingerprint data into 2D or 3D visualizable space [6].

- Compare the chemical space of your target database (LANaPDB) with reference sets (COCONUT, FDA-approved drugs) to identify regions of overlap and uniqueness [6] [9].

Property-Based Filtering

- Analyze the distribution of physicochemical properties relevant to drug-likeness (molecular weight, logP, hydrogen bonding) [6].

- Apply drug-likeness filters (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five, Veber's rules) appropriate for your therapeutic target and administration route [6].

- For NP-specific optimization, consider metrics like the NP-likeness score, which is computed for COCONUT compounds using NaPLeS [11].

Structural Diversity Assessment

- Perform structural classification using tools like ClassyFire to understand the chemical class distribution in your dataset [11].

- Calculate molecular complexity metrics and synthetic accessibility scores to prioritize compounds with feasible synthesis pathways [6].

- Identify "privileged scaffolds" – structures capable of providing useful ligands for more than one receptor – which are particularly abundant in NPs [6].

The following diagram illustrates the chemical space analysis protocol:

Diagram 2: Chemical Multiverse Analysis Workflow. This protocol employs multiple fingerprint representations and dimensionality reduction techniques to comprehensively map the chemical space of natural product databases.

Protocol 3: Virtual Screening Implementation

Materials and Software Requirements

- Molecular docking software (AutoDock, GOLD, Glide, or similar)

- Ligand-based screening tools for similarity searching and pharmacophore modeling

- Machine learning frameworks (scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch)

- High-performance computing resources for large-scale screening

Procedure

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS)

- For targets with known active compounds, perform similarity searching using molecular fingerprints to identify structurally similar NPs [6].

- Develop pharmacophore models based on known active compounds and screen NP databases for matches [6].

- Construct QSAR models using available bioactivity data to predict compound activity for specific targets [6].

Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS)

- Prepare protein structures by removing water molecules, adding hydrogens, and defining binding sites [6].

- Generate multiple conformers for each NP to account for flexibility during docking [6].

- Implement consensus scoring strategies by combining multiple scoring functions to improve hit identification reliability [6].

AI-Assisted Screening

- Train machine learning models on existing bioactivity data to predict compound activity [6].

- Utilize AI-based scoring functions for molecular docking, which have demonstrated improved performance in benchmark studies [6].

- Implement deep learning approaches for de novo design of natural product-inspired compounds [6].

Hit Selection and Prioritization

- Apply structural filters to remove compounds with undesirable properties (e.g., pan-assay interference compounds) [6].

- Evaluate synthetic accessibility to prioritize compounds that can be feasibly obtained or synthesized [6].

- Cross-reference selected hits with commercial availability databases to facilitate acquisition for experimental testing [7].

Natural product databases like LANaPDB and COCONUT provide invaluable resources for modern drug discovery efforts. LANaPDB offers regionally specific diversity with its collection of Latin American natural products, while COCONUT provides comprehensive coverage of NPs from diverse sources [6] [11] [7]. The integration of these databases into virtual screening workflows enables researchers to efficiently explore the vast chemical space of natural products and identify promising candidates for experimental validation.

The protocols outlined in this application note provide a framework for leveraging these databases in computer-aided drug design. By following standardized procedures for database acquisition, preprocessing, chemical space analysis, and virtual screening implementation, researchers can maximize the potential of these resources while ensuring reproducible and scientifically rigorous results. As these databases continue to grow and incorporate new features—such as the community curation and user submission capabilities in COCONUT 2.0—their value to the drug discovery community will only increase [13].

The future of natural product research lies in the intelligent integration of computational and experimental approaches. By leveraging comprehensive databases and robust virtual screening protocols, researchers can more effectively navigate the complex chemical space of natural products and accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutic agents.

Virtual screening (VS) is a cornerstone computational technique in modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to rapidly evaluate massive libraries of small molecules to identify promising lead compounds [14]. By using computer simulations to predict how strongly a molecule will bind to a biological target, VS acts as a powerful filter, significantly reducing the time and cost associated with experimental laboratory testing [14]. This is particularly valuable in fields like natural product research, where chemical libraries can contain hundreds of thousands of unique compounds [15] [16].

There are two predominant computational philosophies in virtual screening: Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS) and Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS). The choice between them is primarily dictated by the available information about the biological target and its known ligands [17] [14]. This article delineates their core principles, methodologies, and practical applications within the context of natural product research.

Conceptual Foundations

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS)

LBVS methodologies rely on the principle of molecular similarity, which posits that molecules with similar structural or physicochemical properties are likely to exhibit similar biological activities [17] [14]. This approach is indispensable when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unknown. Instead, it uses one or more known active compounds (e.g., a natural product with demonstrated efficacy) as query templates to search for analogous structures in large databases [18] [16]. The underlying assumption is that compounds similar to the template have a high probability of being active against the same target.

Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS)

In contrast, SBVS requires the three-dimensional structure of the target protein, obtained through methods such as X-ray crystallography, NMR, or cryo-EM [19] [14]. The most common SBVS technique is molecular docking, which computationally simulates how a small molecule (ligand) binds to the binding site of the target protein [19] [14]. The process predicts the optimal binding orientation (pose) of the ligand and evaluates the strength of the interaction using a scoring function, which estimates the binding affinity [19] [14]. SBVS focuses on finding molecules that are structurally and chemically complementary to the target's binding pocket.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of LBVS and SBVS

| Feature | Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS) | Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS) |

|---|---|---|

| Required Information | Known active ligand(s) | 3D structure of the target protein |

| Fundamental Principle | Molecular similarity & Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) | Molecular docking & binding affinity prediction |

| Primary Methods | 2D/3D similarity search, pharmacophore modeling, QSAR [17] [20] | Molecular docking, scoring functions [19] [14] |

| Typical Use Case | Target structure unknown; sufficient known actives available [16] | Target structure is known; exploring novel scaffolds [21] |

| Key Advantage | Fast, high-throughput; no need for target structure [16] [20] | Provides structural insights; can identify novel chemotypes [21] |

| Main Limitation | Bias towards known chemotypes; limited scaffold hopping [17] | Computationally intensive; dependent on target structure quality [17] |

Methodological Approaches and Workflows

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening Workflow

LBVS employs a variety of techniques to quantify molecular similarity. The following workflow outlines a typical LBVS process for screening a natural product database.

Diagram 1: A typical Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS) workflow involves multiple parallel approaches to assess molecular similarity.

As shown in Diagram 1, the process begins with a known active ligand and can proceed through several methodological paths:

- 2D Fingerprint-Based Screening: This is a highly efficient and widely used method. Molecular structures are converted into bit strings (fingerprints) that encode structural patterns, such as the presence of specific functional groups or atom environments [20]. The similarity between the query and database molecules is then calculated using coefficients like the Tanimoto coefficient, with values closer to 1.0 indicating higher similarity [18] [20]. For example, the open-source tool VSFlow can perform this screening using various fingerprints like ECFP4 and similarity measures [20].

- Pharmacophore Modeling: A pharmacophore is an abstract model that defines the essential steric and electronic features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings) necessary for a molecule to interact with a biological target [17] [14]. Database screening involves searching for molecules that possess this arrangement of features.

- Shape-Based Screening: This 3D method assesses the similarity of the molecular volume and shape between a query compound and database molecules [18]. Tools like ROCS rapidly overlay molecular structures to maximize shape overlap, often combined with chemical feature matching (a "color force field") for improved accuracy [18]. VSFlow also includes a shape-based screening mode that combines shape and 3D pharmacophore fingerprint similarity into a composite score [20].

Structure-Based Virtual Screening Workflow

SBVS, primarily through molecular docking, provides a more detailed view of the ligand-target interaction. The workflow is generally sequential and more computationally intensive.

Diagram 2: A standard Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS) workflow using molecular docking, from preparation to advanced validation.

The SBVS workflow involves several critical steps:

- Protein and Ligand Library Preparation: The protein structure is prepared by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and correcting any structural anomalies. The small molecule library is similarly processed, generating 3D structures and optimizing their geometry [19].

- Binding Site Identification: The specific region on the protein where the ligand binds (e.g., an active site) is defined.

- Molecular Docking: This step consists of two parts:

- Pose Prediction: The algorithm places (docks) each ligand from the library into the protein's binding site, generating multiple possible binding orientations (poses) [19] [14].

- Scoring: A scoring function ranks the generated poses based on the estimated binding affinity. This function is typically a mathematical approximation of the intermolecular interactions (van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic interactions) [19] [14]. AutoDock Vina is a widely cited example of a docking program that uses a scoring function to evaluate poses [19].

- Post-Docking Analysis and Validation: The top-ranked hits are visually inspected to analyze predicted binding modes and key interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, pi-stacking). For higher confidence, top hits can be validated with more computationally intensive methods like Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, which assess the stability of the ligand-protein complex over time [22] [16].

Practical Application in Natural Product Research

The integration of LBVS and SBVS is highly effective for discovering bioactive natural products. A representative application is the search for SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (Mpro) inhibitors.

Case Study: Identifying SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Inhibitors from Natural Product Libraries

Objective: To rapidly identify natural products that can inhibit the SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (Mpro), a key viral enzyme, from a large database of over 400,000 compounds [16].

Hybrid Screening Protocol:

- Initial LBVS Pre-filtering: A ligand-based similarity search was performed to narrow down the massive database to a more manageable number of candidates. This step leveraged the speed of LBVS to reduce computational burden [16].

- SBVS for Detailed Evaluation: The filtered compounds were then subjected to structure-based molecular docking against the crystal structure of Mpro (PDB ID: 6LU7). Docking predicted the binding poses and affinity of each natural product within the enzyme's active site [16].

- Interaction Analysis and Hit Selection: The docking results were analyzed to select hits based on two criteria: i) high predicted binding affinity, and ii) formation of key interactions with amino acid residues critical for Mpro function [16].

- Experimental Validation: The top candidates were tested in in vitro protease inhibition assays. This study reported a high success rate, with over 50% (4 out of 7) of the tested natural products showing significant inhibitory activity, validating the computational approach [16].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Virtual Screening

| Tool/Reagent Category | Examples | Function in Virtual Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Natural Product Databases | NuBBEDB [21], Dr. Duke's Database [22], NPASS [22] | Source of natural product structures for screening; provides chemical diversity. |

| LBVS Software | VSFlow [20], ROCS [18], SwissSimilarity [20] | Performs fast 2D/3D similarity and pharmacophore searches against compound libraries. |

| SBVS Software | AutoDock Vina [19], Molecular Docking Programs [14] | Docks small molecules into a protein target and scores their binding affinity. |

| Protein Structure Repository | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of 3D protein structures (e.g., SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, 6LU7) for SBVS [16]. |

| Cheminformatics Toolkit | RDKit [20] | Open-source core library for handling molecules, calculating descriptors, and generating fingerprints. |

Combined and Sequential Screening Strategies

The case study above exemplifies a sequential combination of LBVS and SBVS, where the faster LBVS method is used for initial filtering before the more rigorous SBVS analysis [17] [23]. This strategy optimizes the trade-off between computational speed and structural insight.

Other combined strategies include [17] [23]:

- Parallel Screening: Running LBVS and SBVS independently and then merging the results using data fusion algorithms to create a final ranked list.

- Hybrid Methods: Integrating LB and SB information into a single, unified framework, such as using interaction fingerprints or machine learning models trained on both ligand and structure data.

These integrated approaches leverage the strengths of both methods—the speed and bias toward known actives from LBVS, and the ability to discover novel scaffolds and provide mechanistic insights from SBVS—while mitigating their individual weaknesses [17].

Ligand-Based and Structure-Based Virtual Screening are two fundamental, complementary pillars of computational drug discovery. LBVS, grounded in molecular similarity, offers a rapid and efficient path to identify analogs of known actives, especially when structural data on the target is scarce. In contrast, SBVS, through molecular docking, provides an atomic-level, mechanistic view of ligand-target interactions, facilitating the discovery of novel chemotypes. As demonstrated in successful applications within natural product research, a strategic combination of these approaches, tailored to the available information, creates a powerful pipeline for accelerating the identification of new bioactive compounds from the vast and promising realm of natural products.

Advantages and Inherent Challenges of Screening Natural Product Libraries

Natural products (NPs) and their derivatives have historically been a prolific source of bioactive compounds, constituting a significant percentage of approved drugs worldwide, particularly for cancer and infectious diseases [24] [25]. The structural complexity, diversity, and biological relevance of NPs make them an indispensable resource for modern drug discovery [25]. However, the pursuit of new therapeutics from nature presents a unique set of technical and strategic challenges that require sophisticated protocols to overcome [26]. This document outlines the core advantages of NP libraries, details the inherent challenges in their screening, and provides detailed application notes and protocols framed within a virtual screening paradigm for NP database research. The content is designed to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in leveraging the full potential of NP libraries through integrated computational and experimental workflows.

Advantages of Natural Product Libraries

Natural product libraries offer distinct advantages over synthetic chemical libraries, which are rooted in the evolutionary history and inherent properties of the molecules.

Proven Therapeutic Track Record

A significant proportion of modern small-molecule drugs, including two-thirds of current therapeutics, originate from unaltered natural products, their analogues, or contain natural product pharmacophores [25]. This historical success validates NPs as a premier source for novel lead compounds.

Unparalleled Chemical Diversity and Complexity

NPs exhibit structural features that are often under-represented in synthetic compound libraries. They are frequently characterized by complex ring systems, a high density of chiral centers, significant molecular rigidity, and a rich display of oxygen-containing functional groups [25]. This diversity explores regions of chemical space that are difficult to access through conventional synthetic methods, increasing the probability of identifying novel bioactive scaffolds.

Evolutionary Bias towards Bio-Relevance

Molecules derived from nature have often evolved to interact with biological macromolecules. It has been observed that traditional screening decks are biased toward molecules that proteins have evolved to recognize, such as metabolites, natural products, and their mimicking drugs [27]. This inherent "bio-likeness" was a notable feature of in-stock libraries and High-Throughput Screening (HTS) decks, potentially contributing to their past success [27].

Table 1: Key Advantages of Natural Product Libraries over Synthetic Libraries

| Advantage | Description | Implication for Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Proven Success | Source of a large percentage of approved drugs, especially for cancer and antibiotics [24] [25]. | Higher probability of discovering a viable lead compound. |

| Structural Diversity | High stereochemical complexity, diverse ring systems, and unique scaffolds [25]. | Access to novel chemical space and new mechanisms of action. |

| Bio-Relevance | Evolved to interact with biological targets; traditional libraries showed a bias towards these molecules [27]. | Potentially higher hit rates and better binding affinity for biological targets. |

Inherent Challenges in Natural Product Screening

Despite their advantages, working with NP libraries presents significant hurdles that can complicate screening campaigns and downstream development.

Technical and Logistical Barriers

A primary challenge is the sourcing and supply of raw materials. Collecting source organisms requires adherence to international regulations like the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing (ABS) and national laws, which can be time-consuming [24]. Furthermore, the chemical complexity of crude natural product extracts, which contain a plethora of molecules at varying concentrations, can lead to assay interference from colored compounds, fluorophores, or toxins [24] [26]. This complexity increases the risk of identifying false positives or missing actives due to antagonistic effects.

Challenges in Screening and Characterization

The presence of nuisance compounds in crude extracts has diminished their utility in modern, target-based HTS platforms, leading to a shift towards prefractionated libraries [24]. A major bottleneck is dereplication—the process of early identification of known compounds to avoid rediscovery—which is resource-intensive [26]. Finally, the structural complexity of many NPs, while advantageous for bioactivity, can make their de novo synthesis or large-scale optimization economically challenging [25].

The Diminishing "Bio-Like" Bias in Ultra-Large Libraries

An emerging challenge is the changing nature of virtual screening libraries. With the advent of ultra-large "tangible" or make-on-demand virtual libraries (containing billions of readily synthesizable molecules), the chemical landscape is shifting. Research shows that while traditional in-stock libraries were highly biased toward "bio-like" molecules (metabolites, natural products, drugs), this bias decreases dramatically in larger tangible libraries. One study found a 19,000-fold decrease in molecules essentially identical to bio-like molecules in a 3-billion compound tangible library compared to a 3.5-million in-stock library [27]. Consequently, hit compounds identified from docking these massive libraries often show low structural similarity to known bio-like molecules [27]. This suggests that the success of screening ultra-large libraries may be less dependent on mimicking natural products and more on exhaustive sampling of chemical space.

Table 2: Key Challenges in Natural Product Library Screening

| Challenge Category | Specific Challenge | Impact on Discovery Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Technical & Logistical | Access, collection, and benefit-sharing regulations [24]. | Can delay or prevent access to biodiverse source organisms. |

| Complex mixture nature of crude extracts [24] [26]. | Assay interference; difficult to identify the active component. | |

| Screening & Characterization | Need for prefractionation for modern HTS [24]. | Increases initial cost and time for library production. |

| Dereplication to avoid rediscovery [26]. | Consumes significant time and resources. | |

| Chemical Development | Complex structures hinder synthesis and optimization [25]. | Can make lead optimization and scale-up prohibitively expensive. |

| Virtual Screening Context | Decreasing "bio-like" character in ultra-large libraries [27]. | May alter hit expectations and require new prioritization strategies. |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Building a Quantitatively Guided Natural Product Library

Principle: To maximize the chemical diversity of a natural product library from microbial sources (e.g., fungi) by integrating genetic barcoding and metabolomic profiling to guide sampling depth and avoid redundancy [28].

Reagents & Materials:

- Fungal isolates (e.g., from a soil collection program)

- DNA extraction and sequencing reagents for Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) region

- Materials for liquid culture and metabolite extraction

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) system

Procedure:

- Strain Acquisition and Identification: Acquire fungal isolates from environmental samples. Extract genomic DNA and sequence the ITS barcode region for each isolate. Phylogenetically analyze ITS sequences to group isolates into genetic clades [28].

- Metabolome Profiling: Culture each fungal isolate in an appropriate liquid medium. Perform a standardized metabolite extraction (e.g., using organic solvents like ethyl acetate or methanol). Analyze all extracts using a uniform LC-MS method to detect chemical features based on retention time and mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio [28].

- Chemical Diversity Analysis: Process the LC-MS data to create a data matrix of chemical features across all isolates. Perform multivariate statistical analysis (e.g., Principal Coordinate Analysis, PCoA) to group isolates based on their chemical profiles, forming chemical clusters [28].

- Feature Accumulation Modeling: Treating the collection of isolates as a population, plot a feature accumulation curve. This curve graphs the number of unique chemical features detected against the number of isolates sampled. Use this curve to determine the point of diminishing returns, where sampling additional isolates yields few new chemical features [28].

- Library Construction Decision: Based on the feature accumulation curve and the overlap between genetic clades and chemical clusters, select the minimal set of isolates that captures the maximum chemical diversity for inclusion in the final library. This data-driven approach prevents oversampling of chemically redundant strains.

Diagram 1: NP Library Building Workflow

Protocol 2: A Virtual Screening Workflow for Natural Product Databases

Principle: To computationally prioritize NP candidates from a database for experimental testing using a structured in silico workflow that integrates filtration, docking, and careful examination [29] [25].

Reagents & Materials (Computational):

- 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., from X-ray crystallography or homology modeling)

- A database of natural product structures in a suitable format (e.g., SDF, MOL2)

- Computational software for ligand-based and structure-based screening

Procedure:

- Database Curation: Obtain or assemble a database of natural product structures. Prepare the structures for virtual screening by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states at physiological pH, and generating low-energy 3D conformers.

- Drug-Likeness and Property Filtering: Apply computational filters to remove compounds with undesirable properties. This typically includes assessing for compliance with rules such as Lipinski's Rule of Five or other lead-like criteria to improve the likelihood of favorable pharmacokinetics [27] [25].

- Structure-Based Virtual Screening (Molecular Docking): a. System Preparation: Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and defining the binding site of interest. b. Docking Run: Dock the pre-filtered NP database into the target's binding site using a docking program (e.g., AutoDock Vina, Glide, or RosettaVS [30]). c. Pose Scoring and Ranking: Score the predicted protein-ligand complexes and rank the NPs based on their predicted binding affinity or docking score.

- Hit Selection and Visual Inspection: Select the top-ranking compounds for visual inspection. Manually examine the predicted binding poses to ensure they form sensible interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) and that the binding mode is chemically reasonable. This step is crucial for eliminating false positives.

- Experimental Validation: The final, computationally prioritized hits must be acquired or isolated and subjected to experimental binding or activity assays to confirm bioactivity [25]. The process is iterative, with experimental results informing subsequent virtual screening rounds.

Diagram 2: NP Virtual Screening Workflow

Protocol 3: Creating a Prefractionated Natural Product Library for HTS

Principle: To partially purify complex natural product extracts into fractions to reduce nuisance compounds, concentrate minor metabolites, and improve screening performance in target-based assays [24].

Reagents & Materials:

- Crude natural product extracts (e.g., from plants, microbes)

- Solid-phase extraction (SPE) cartridges or High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system

- Solvents (water, methanol, acetonitrile, ethyl acetate) of appropriate grade

Procedure:

- Crude Extract Generation: Generate a crude extract from the source organism using a standardized extraction protocol (e.g., accelerated solvent extraction or maceration with organic solvents) [24].

- Prefractionation by Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE): a. Load the crude extract onto an SPE cartridge (e.g., C18-bonded silica). b. Elute the absorbed material using a step-gradient of solvents with increasing elution strength (e.g., water, 25% methanol, 50% methanol, 100% methanol, 100% ethyl acetate). This yields 4-6 distinct fractions per extract, each enriched with compounds of different polarities [24].

- Alternative/Automated Prefractionation by HPLC: For higher resolution and automation, use HPLC with a reverse-phase column. Collect fractions based on a fixed time interval (e.g., 96-well plate collection) or triggered by UV signal thresholds. This can generate 10-20 fractions per extract [24].

- Quality Control and Library Storage: Evaporate the solvents from each fraction and redissolve them in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at a standardized concentration. Transfer the fractions to 384-well plates for HTS. Log all fraction data and store the plates appropriately.

- Screening Advantage: The resulting prefractionated library shows improved screening performance due to the concentration of active components, sequestration of common nuisance compounds, and streamlined downstream dereplication and isolation processes [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Featured Experiments

| Item Name | Function/Application | Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| ITS Barcode Primers | Amplification and sequencing of the fungal Internal Transcribed Spacer region for phylogenetic grouping and identification [28]. | Protocol 1 |

| LC-MS Grade Solvents | High-purity solvents for metabolome profiling to minimize background noise and ion suppression during mass spectrometry [28]. | Protocol 1 |

| C18 Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | For the prefractionation of crude natural product extracts based on compound hydrophobicity [24]. | Protocol 3 |

| Preparative HPLC System | High-resolution chromatographic separation of complex extracts into individual fractions for library creation [24]. | Protocol 3 |

| 3D Protein Structure (PDB Format) | Essential structural input for structure-based virtual screening and molecular docking simulations [30] [25]. | Protocol 2 |

| Molecular Docking Software (e.g., RosettaVS) | Predicts the binding pose and affinity of natural product ligands to a target protein for virtual hit prioritization [30]. | Protocol 2 |

Building Your Protocol: Methodologies and Practical Applications

Ligand-based drug design represents a cornerstone of modern virtual screening, particularly when the three-dimensional structure of a biological target is unavailable. These approaches rely on the fundamental principle that molecules with similar structural or physicochemical features are likely to exhibit similar biological activities. Within this domain, pharmacophore modeling and chemical similarity searches have emerged as powerful, computationally efficient methods for identifying novel bioactive compounds from large chemical databases [31]. These techniques are especially valuable in natural product research, where the structural complexity and diversity of compounds present unique opportunities and challenges for drug discovery [32].

Pharmacophores provide an abstract representation of molecular interactions, defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [31]. More simply, a pharmacophore represents the spatial arrangement of chemical features essential for biological activity—a pattern that emerges from a set of known active molecules [31]. The utility of pharmacophore models extends across multiple drug discovery applications, including understanding structure-activity relationships (SAR), virtual screening for novel active compounds, and as constraints in molecular docking studies [31] [33].

Similarity searching methods complement pharmacophore approaches by enabling rapid comparison of molecular structures using various descriptor systems. For natural products, which often possess greater molecular complexity, more stereocenters, and higher fractions of sp³ carbons compared to synthetic compounds, specialized similarity methods are often required to capture their unique chemical features effectively [32].

This protocol details the integrated application of ligand-based pharmacophore modeling and similarity searching for virtual screening of natural product databases, providing researchers with a structured framework for identifying novel bioactive compounds.

Theoretical Foundation

Pharmacophore Feature Definitions

A pharmacophore model captures the essential chemical features responsible for a molecule's biological activity. The most common features include:

- Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD): Functional groups capable of donating a hydrogen bond, typically featuring an electronegative atom with an attached hydrogen (e.g., OH, NH).

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA): Atoms capable of accepting a hydrogen bond, usually electronegative atoms with lone pairs (e.g., O, N).

- Hydrophobic (H): Non-polar regions of the molecule that favor lipid environments (e.g., alkyl chains, aromatic rings).

- Positive Ionizable (PI): Groups that can carry a positive charge under physiological conditions (e.g., amines).

- Negative Ionizable (NI): Groups that can carry a negative charge (e.g., carboxylic acids).

- Aromatic (AR): Planar ring systems with delocalized π-electrons.

- Exclusion Volumes (EV): Spatial regions where atoms are sterically forbidden, typically representing protein atoms.

The specific features incorporated into a model depend on the protein-ligand interaction patterns observed in known active compounds. For instance, a study targeting XIAP protein identified a pharmacophore model containing four hydrophobic features, one positive ionizable feature, three hydrogen bond acceptors, and five hydrogen bond donors based on analysis of protein-ligand complex interactions [33].

Molecular Similarity Principles

The similarity property principle—that structurally similar molecules tend to have similar properties—underlies all similarity-based virtual screening approaches. The effectiveness of these methods depends critically on the choice of molecular representation and similarity metric [32].

For natural products, which often exhibit greater structural complexity and three-dimensional diversity than synthetic compounds, circular fingerprints (such ECFP and FCFP fingerprints) have demonstrated superior performance in similarity searching compared to path-based or structural key fingerprints [32]. These fingerprints capture molecular neighborhoods around each atom, providing a more comprehensive representation of complex molecular scaffolds.

Computational Protocols

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

This protocol outlines the generation and validation of quantitative pharmacophore models using known active compounds, based on methodologies successfully applied to targets including topoisomerase I and XIAP [34] [33].

Step 1: Training Set Compilation

- Select 20-30 compounds with known activity against the target (ideally spanning 3-4 orders of magnitude in potency)

- Ensure structural diversity while maintaining common pharmacophoric features

- Divide compounds into training (~70%) and test sets (~30%)

- For natural products, consider specialized libraries such as the Ambinter natural compound database [33]

Step 2: Molecular Conformation Generation

- Generate representative 3D conformations for each compound

- Use energy window of 10-20 kcal/mol above global minimum

- Maximum of 250 conformations per compound

- Employ algorithms such as Poling or Boltzmann-weighted stochastic search

Step 3: Pharmacophore Model Generation

- Use HypoGen algorithm or comparable methodology

- Define feature mapping based on common chemical functionalities

- Set parameters: minimum 0, maximum 5 features per model

- Generate 10 top-ranked hypotheses

- Select best model based on correlation coefficient, cost analysis, and root mean square deviation (RMSD)

Step 4: Model Validation

- Calculate correlation coefficient for training set predictions (target: R > 0.8)

- Predict activity of test set compounds (target: R > 0.6)

- Determine Fisher's randomization confidence (target: >95%)

- Perform decoy screening using DUD-E or comparable database [33]

- Calculate enrichment factors (EF1%) and area under ROC curve (AUC) (target: EF1% > 5, AUC > 0.7)

Table 1: Pharmacophore Model Validation Metrics from Representative Studies

| Target Protein | Training Set Correlation | Test Set Correlation | EF1% | AUC | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topoisomerase I | 0.92 | 0.85 | N/R | N/R | [34] |

| XIAP | N/R | N/R | 10.0 | 0.98 | [33] |

| LpxH | 0.89 | 0.81 | N/R | N/R | [35] |

N/R: Not reported in the cited study

Chemical Similarity Search Protocol

This protocol describes the implementation of similarity-based virtual screening for natural product discovery, adapting methodologies validated for modular natural products including nonribosomal peptides, polyketides, and hybrids [32].

Step 1: Query Compound Selection

- Identify known high-activity natural product as query structure

- Ensure chemical and biological relevance to target

- Consider using multiple active compounds as queries

Step 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation

- Generate 2D molecular fingerprints for query and database compounds

- Recommended fingerprints: ECFP6, FCFP6, or Pattern fingerprints

- For natural products, consider biosynthetic descriptor systems (e.g., GRAPE/GARLIC)

Step 3: Similarity Calculation

- Compute Tanimoto coefficient between query and database compounds

- Formula: Tc = |A ∩ B| / |A ∪ B|, where A and B are fingerprint bitsets

- Set similarity threshold based on validation experiments (typically Tc > 0.7-0.8)

Step 4: Result Analysis and Validation

- Select top 1-5% of database ranked by similarity

- Assess chemical diversity of hits

- Evaluate scaffold hopping potential

- Validate with known actives not used as queries

Table 2: Performance of Molecular Fingerprints on Natural Product Similarity Search

| Fingerprint Type | Radius/Parameters | Accuracy (%) | Recommended Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECFP6 | Radius 3 | 92.5 | General natural products |

| FCFP6 | Radius 3 | 90.8 | Functional group focus |

| GRAPE/GARLIC | Retrobiosynthetic | 99.9 | Modular natural products |

| MACCS Keys | 166 structural keys | 85.2 | Rapid screening |

| Pattern Fingerprint | Functional patterns | 88.7 | Scaffold hopping |

Data adapted from similarity testing on modular natural product libraries [32]

Integrated Virtual Screening Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete integrated workflow for ligand-based virtual screening of natural product databases, combining both pharmacophore modeling and similarity search approaches:

Workflow for Ligand-Based Virtual Screening

This integrated workflow leverages the complementary strengths of pharmacophore modeling and similarity searching. Pharmacophore approaches excel at identifying compounds that share key interaction features but may possess diverse scaffolds, while similarity searching efficiently finds structurally analogous compounds with potentially conserved biological activity.

Case Study Applications

Discovery of Topoisomerase I Inhibitors

A comprehensive study demonstrated the application of ligand-based pharmacophore modeling for discovering novel topoisomerase I inhibitors [34]. Researchers developed a quantitative pharmacophore model (Hypo1) using 29 camptothecin derivatives as a training set. The validated model was used to screen over one million drug-like molecules from the ZINC database, followed by Lipinski rule filtering, SMART filtration, and molecular docking. This integrated approach identified three potential inhibitory 'hit molecules' (ZINC68997780, ZINC15018994, and ZINC38550809) with stable binding to the topoisomerase I-DNA cleavage complex, as confirmed by molecular dynamics simulations [34].

Identification of Natural Anti-Cancer Agents Targeting XIAP

In another successful application, structure-based pharmacophore modeling was employed to identify natural XIAP inhibitors for cancer therapy [33]. The pharmacophore model was generated from a protein-ligand complex (PDB: 5OQW) and validated with excellent enrichment performance (EF1% = 10.0, AUC = 0.98). Virtual screening of natural product databases followed by molecular docking and dynamics simulations identified three promising compounds: Caucasicoside A (ZINC77257307), Polygalaxanthone III (ZINC247950187), and MCULE-9896837409 (ZINC107434573). These compounds demonstrated stable binding to the XIAP protein and favorable drug-like properties, highlighting their potential as lead compounds for cancer treatment [33].

Modular Natural Product Similarity Searching

The LEMONS (Library for the Enumeration of MOdular Natural Structures) algorithm was specifically developed to address the unique challenges of natural product similarity assessment [32]. This approach enables controlled enumeration of hypothetical modular natural product structures and systematic evaluation of similarity search methods. Comparative analysis demonstrated that circular fingerprints (ECFP/FCFP) generally outperform other 2D fingerprints for natural product similarity searching, while retrobiosynthetic approaches (GRAPE/GARLIC) achieve near-perfect accuracy when applicable [32]. This specialized methodology facilitates targeted exploration of natural product chemical space and enhances genome mining for bioactive natural products.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Ligand-Based Virtual Screening

| Tool Category | Representative Software | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Discovery Studio, LigandScout, Phase | Pharmacophore model generation, validation, and screening | LigandScout excels in structure-based pharmacophore modeling from protein-ligand complexes [33] |

| Molecular Fingerprinting | RDKit, OpenBabel, Canvas | Calculation of molecular descriptors and fingerprints | RDKit provides comprehensive open-source cheminformatics capabilities |

| Similarity Search | Pharmit, ZINC, UNITY-3D | 3D database searching and similarity assessment | Pharmit enables ultra-fast pharmacophore search of large compound databases [36] |

| Conformational Analysis | OMEGA, CONFGEN, MOE | Generation of representative molecular conformations | OMEGA efficiently generates multi-conformer databases for 3D screening |

| Natural Product Databases | ZINC Natural Products, COCONUT, NPASS | Curated collections of natural products | ZINC provides readily purchasable natural compounds with 3D structures [33] |

| ADMET Prediction | SwissADME, admetSAR, PreADMET | Prediction of pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties | Essential for prioritizing compounds with favorable drug-like properties [37] |

Advanced Methodologies and Emerging Trends

The field of ligand-based virtual screening continues to evolve with several advanced methodologies enhancing traditional approaches:

Fragment-Based Screening in Large Chemical Spaces

Novel algorithms such as Galileo enable 3D pharmacophore searching in fragment spaces, including Enamine's REAL Space containing over 29 billion make-on-demand compounds [38]. This genetic algorithm-based approach combines fragment-based drug design with pharmacophore mapping (Phariety algorithm), allowing efficient navigation of ultra-large chemical spaces that cannot be fully enumerated due to combinatorial explosion [38].

AI-Enhanced Pharmacophore Techniques

Machine learning approaches are increasingly being applied to pharmacophore-based screening. PharmacoForge represents a recent innovation using diffusion models to generate 3D pharmacophores conditioned on protein pockets [36]. This method generates pharmacophore queries that identify valid, commercially available ligands while avoiding synthetic accessibility issues common to de novo molecular generation. Similarly, DiffPhore implements a knowledge-guided diffusion framework for 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping, demonstrating superior performance in predicting binding conformations compared to traditional pharmacophore tools and several docking methods [39].

Specialized Similarity Methods for Natural Products

For modular natural products including nonribosomal peptides and polyketides, retrobiosynthetic alignment algorithms (e.g., GRAPE/GARLIC) have shown exceptional performance in similarity assessment [32]. These methods leverage biosynthetic logic to compare natural product structures, effectively identifying compounds originating from similar enzymatic assembly lines even when traditional fingerprints fail to detect meaningful similarity.

Ligand-based approaches comprising pharmacophore modeling and similarity searches provide powerful, computationally efficient methods for virtual screening of natural product databases. When properly implemented using the protocols outlined herein, these techniques can successfully identify novel bioactive compounds with potential therapeutic applications. The integration of these methods with structure-based approaches, ADMET prediction, and experimental validation creates a robust framework for natural product-based drug discovery that leverages the unique structural diversity and biological relevance of natural compounds while mitigating the challenges associated with their structural complexity.

Molecular docking is a foundational computational technique in structure-based drug discovery, used to predict the preferred orientation and binding conformation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target macromolecule (receptor). When applied to the screening of natural product (NP) libraries, docking facilitates the identification of novel bioactive compounds from vast chemical space by prioritizing candidates for further experimental validation [22] [40]. The core objective is to predict the ligand's binding pose—its precise three-dimensional position and orientation within the target's binding site—and often to estimate the strength of this interaction through a scoring function. The integration of these strategies into virtual screening protocols is revitalizing natural product research, offering a powerful method to navigate the structural complexity and diversity of NPs for tackling modern therapeutic challenges such as antimicrobial resistance [41] [42] [40].

Key Concepts and Terminology

Table 1: Fundamental Concepts in Molecular Docking.

| Concept | Description | Role in Virtual Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Pose Prediction | The computational process of predicting the three-dimensional orientation (conformation) of a ligand within a protein's binding site. | Generates plausible binding modes for subsequent scoring and analysis [43]. |

| Scoring Function | A mathematical function used to predict the binding affinity (or a related score) of a protein-ligand complex based on its predicted pose. | Ranks and prioritizes ligands from a large database; crucial for hit identification [44] [43]. |

| Binding Affinity | The strength of the interaction between a protein and a ligand, often quantified by experimental measures like inhibition constant (Ki) or dissociation constant (Kd). | The key property that scoring functions aim to predict; high predicted affinity suggests potential efficacy [44]. |

| Virtual Screening | The in silico evaluation of large libraries of chemical compounds to identify those most likely to bind to a drug target. | Enables the rapid and cost-effective prioritization of natural products for experimental testing [22] [42]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | A simulation technique that models the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. | Used to refine docking poses and assess the stability of protein-ligand complexes under dynamic conditions [41] [42]. |

Application Notes: Docking in Natural Product Research

Protocol for Structure-Based Virtual Screening of Natural Product Libraries

The following workflow details a standardized protocol for screening in-house NP libraries, integrating methodologies from recent studies [22] [42].

Library Curation and Ligand Preparation

- Source: Construct a library of natural product structures from curated databases such as LOTUS, NPASS, or Dr. Duke's Phytochemical and Ethnobotanical Databases [22] [42].

- Preparation: Process the NP structures using a tool like Schrödinger's LigPrep. Steps include:

- Generating plausible ionization states at a physiological pH (e.g., 7.0 ± 0.5).

- Generating possible stereoisomers.

- Performing energy minimization using a force field (e.g., OPLS_2005) to achieve a stable, low-energy 3D conformation for each molecule [42].

Target Selection and Protein Preparation

- Source: Obtain the high-resolution 3D structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Prefer structures with high resolution (< 2.5 Å) and minimal missing residues.

- Preparation (using a tool like Protein Preparation Wizard):

- Add hydrogen atoms and assign appropriate protonation states to residues (e.g., using PROPKA at pH 7.0).

- Remove native ligands and crystallographic water molecules, unless waters are part of a conserved catalytic network.

- Optimize the hydrogen-bonding network.

- Perform a constrained energy minimization of the protein structure to relieve steric clashes [42].

Binding Site Definition and Grid Generation

- Define the spatial coordinates (a "grid box") that encompass the binding site of interest. This can be based on the location of a co-crystallized native ligand or through binding site prediction algorithms.

- The grid dimensions should be large enough to allow the ligand to rotate freely but focused enough to ensure computational efficiency [42].

Molecular Docking Execution

Post-Docking Analysis and Hit Selection

- Pose Clustering: Analyze the top-ranked poses for each compound. Visually inspect the consistency of binding modes, particularly for the highest-ranking compounds.

- Interaction Analysis: Examine the specific molecular interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, pi-stacking) formed between the NP and key residues in the binding site.

- Consensus Scoring: Consider using multiple scoring functions or post-processing methods to improve hit-prediction reliability.

- Selection: Select the top candidates (e.g., 10-50 compounds) based on a combination of favorable docking scores and interaction profiles for further analysis [41] [22].

Validation and Prioritization

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Subject the top-ranked NP-protein complexes to MD simulations (e.g., 50-100 ns) to evaluate the stability of the predicted binding pose over time and under dynamic conditions. Key metrics include Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) and Root-Mean-Square Fluctuation (RMSF) [41] [42].

- Binding Free Energy Calculations: Use methods like MM-GBSA (Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area) on MD trajectories to obtain a more rigorous estimate of binding affinity [42].

- ADMET Profiling: Perform in silico prediction of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties to filter out compounds with unfavorable pharmacokinetic or safety profiles [22] [42].

Performance of Docking and Scoring Methodologies

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Docking and Scoring Approaches.

| Method / Model | Key Principle | Reported Performance (Dataset) | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Empirical scoring function with gradient optimization. | Widely used for pose prediction and virtual screening [41] [22]. | Docking of FDA-approved drugs and NPs against bacterial resistance proteins [41] [42]. |

| Glide (SP Mode) | Hierarchical docking with a robust empirical scoring function. | Used for virtual screening of 1,400+ NPs from LOTUS [42]. | Identification of macrolide resistance enzyme inhibitors [42]. |

| DeepDTA | 1D CNN to process protein sequences and drug SMILES. | Baseline deep learning model for binding affinity prediction [44]. | Predictive model for drug-target interactions. |

| GraphDTA | Represents drugs as molecular graphs to better capture structure. | Improved performance over DeepDTA [44]. | Regression-based prediction of binding affinity values. |

| DeepDTAGen | Multitask deep learning for affinity prediction and target-aware drug generation. | MSE: 0.146, CI: 0.897, r²m: 0.765 (KIBA) [44]. | State-of-the-art for simultaneous prediction and generation. |

Workflow Visualization

Virtual Screening Workflow for Natural Products: This diagram outlines the key stages in a structure-based virtual screening campaign, from initial structure preparation through to the final selection of validated natural product candidates.

Ligand Pose Prediction and Scoring: This diagram illustrates the core computational process of molecular docking, which involves searching the conformational space of the ligand and scoring each generated pose to identify the most probable binding mode.

Table 3: Key Software and Data Resources for Molecular Docking.

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Docking & Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids; the primary source for target receptor structures [42]. |

| LOTUS Database | Database | Open, comprehensive repository for natural product structures and occurrence data; a key source for NP libraries [42]. |

| AutoDock Vina | Software | Widely-used molecular docking and virtual screening software [41] [22]. |

| Schrödinger Suite | Software | Commercial software suite providing integrated tools for protein preparation (Protein Prep Wizard), docking (Glide), and MD simulations [42]. |

| GROMACS | Software | A versatile package for performing MD simulations and energy minimization, used for validating docking results [41] [42]. |

| admetSAR | Web Server | Online tool for predicting the ADMET properties of drug candidates, used for post-docking prioritization [22]. |

| Osiris DataWarrior | Software | Open-source program for structure-based SAR analysis, calculation of molecular properties, and filtering compounds [22]. |

Virtual screening stands as a cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery, providing a powerful and cost-effective strategy for identifying hit compounds from vast chemical libraries. Within this domain, two primary computational philosophies have emerged: ligand-based and structure-based virtual screening. Each method possesses distinct strengths and inherent limitations. However, the integration of these approaches into a hybrid methodology leverages their complementary capabilities, resulting in enhanced hit rates, greater scaffold diversity, and increased confidence in candidate selection. This synergy is particularly valuable in the screening of natural product databases, where molecular complexity and diversity present unique challenges and opportunities for uncovering novel therapeutics [45] [46].

This application note details the practical implementation of a hybrid virtual screening protocol, framed within the context of natural product research. It provides a structured workflow, quantitative performance comparisons of current tools, and a detailed experimental protocol to guide researchers in deploying this powerful strategy effectively.

Core Concepts and Rationale for Hybridization

The hybrid approach mitigates the limitations of one method by leveraging the strengths of the other, creating a more robust and reliable screening process [45].

- Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS) operates without a target protein structure, using known active ligands to identify potential hits based on structural or pharmacophoric similarity. Its strengths lie in computational speed and excellent pattern recognition, making it ideal for rapidly prioritizing compounds in large, diverse libraries, especially when protein structural data is limited or unavailable [45].