Validating RNA-seq with RT-qPCR in Cancer Research: A Comprehensive Guide from Bench to Bedside

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating RNA-seq findings with RT-qPCR in cancer research.

Validating RNA-seq with RT-qPCR in Cancer Research: A Comprehensive Guide from Bench to Bedside

Abstract

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating RNA-seq findings with RT-qPCR in cancer research. It covers the fundamental principles establishing RNA-seq as the modern standard for transcriptome analysis and RT-qPCR as the gold standard for validation. The content explores detailed methodological workflows for both techniques, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and presents rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses. By integrating insights from recent studies and clinical applications, this guide serves as an essential resource for ensuring the accuracy, reliability, and clinical translatability of gene expression data in oncology.

The Essential Partnership: Understanding RNA-seq and RT-qPCR in Modern Cancer Biology

In the pursuit of precision oncology, researchers and drug development professionals increasingly rely on sophisticated molecular tools that can bridge the gap between genetic alterations and their functional consequences. While DNA sequencing reveals the static genetic landscape of tumors, it provides limited insight into which mutations are functionally active in cancer pathogenesis. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has emerged as a transformative discovery powerhouse that dynamically characterizes the complete transcriptome, enabling researchers to identify novel transcripts, detect expressed mutations, and discover robust biomarkers with clinical utility [1]. This capability is particularly valuable for classifying cancer types, predicting treatment responses, and identifying novel therapeutic targets.

The integration of RNA-seq with validation technologies like RT-qPCR creates a powerful framework for translating discovery research into clinically actionable insights. As high-throughput RNA-seq technologies continue to evolve, they offer unprecedented opportunities to unravel the complex molecular mechanisms driving cancer progression, metastasis, and drug resistance. This guide objectively compares the performance of various RNA-seq approaches and provides supporting experimental data within the context of validating RNA-seq findings through RT-qPCR, offering researchers a comprehensive resource for strategic experimental design in cancer research.

RNA-seq Technology Landscape: A Comparative Analysis

RNA-seq technologies have diversified significantly, with each approach offering distinct advantages for specific applications in cancer research. The table below summarizes four principal RNA-seq methodologies, their core principles, key applications, and performance considerations.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of RNA-seq Technologies in Cancer Research

| Technology | Sequencing Principle | Key Applications in Cancer | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-Read (Illumina) | Sequencing by synthesis of short cDNA fragments (75-300 bp) | Differential gene expression, mutation detection, fusion gene identification [2] | High accuracy, low cost per sample, well-established bioinformatics tools | Limited ability to resolve complex isoforms, transcript ambiguity |

| Long-Read (Nanopore) | Direct RNA sequencing via nanopores, full-length transcripts [2] | Novel isoform discovery, complex splicing analysis, transcript structure characterization [2] | Sequences complete transcripts, detects epigenetic RNA modifications, no PCR amplification bias | Higher error rate, requires more input RNA, computationally intensive |

| Single-Cell RNA-seq | Barcoding and sequencing of individual cells | Tumor heterogeneity mapping, tumor microenvironment characterization, rare cell population identification [3] | Unprecedented resolution of cellular diversity, reveals cell-type specific expression patterns | Technically challenging, high cost, sparse data per cell |

| Targeted RNA-seq | Probe-based enrichment of specific gene panels | Expression profiling of signature genes, clinical biomarker validation [4] | Enhanced sensitivity for low-abundance transcripts, cost-effective for focused analyses | Limited to predefined gene sets, potential probe hybridization issues |

Performance Metrics Across Platforms

When selecting an RNA-seq platform for cancer biomarker discovery, researchers must consider multiple performance parameters. Recent studies have systematically evaluated these technologies across critical metrics:

Sensitivity and Specificity: Targeted RNA-seq panels demonstrate enhanced sensitivity for detecting low-abundance transcripts and rare mutations compared to whole transcriptome approaches. In one study, targeted panels identified clinically actionable mutations with a 97.3% sensitivity and 99.8% specificity when validated against reference standards [4].

Accuracy in Mutation Detection: Integrated DNA-RNA sequencing approaches significantly improve mutation detection accuracy. A combined assay analyzing 2,230 clinical tumor samples demonstrated that RNA-seq recovered variants missed by DNA-only testing, particularly in low-purity tumor samples, while also reducing false positives by confirming expression of putative mutations [5].

Reproducibility: Technical reproducibility between replicates is consistently high across platforms. Long-read RNA-seq datasets from pancreatic cancer cell lines showed high correlation between biological replicates (R² > 0.95), indicating robust performance even for complex transcriptomes [2].

RNA-seq Workflows and Experimental Design

Standardized RNA-seq Experimental Protocol

Implementing a rigorous, standardized workflow is essential for generating high-quality, reproducible RNA-seq data in cancer research. The following protocol outlines key steps from sample preparation to data analysis:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Workflows

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in RNA-seq Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization | RNAlater, PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes | Preserves RNA integrity immediately after sample collection, prevents degradation |

| RNA Extraction Kits | AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit, miRNeasy Mini Kit | Isols high-quality total RNA from various sample types (fresh frozen, FFPE) |

| RNA Quality Assessment | Bioanalyzer RNA Integrity chips, Qubit RNA assays | Evaluates RNA quality (RIN scores) and quantity before library preparation |

| Library Preparation Kits | TruSeq Stranded mRNA, NEBNext Ultra II, QuantSeq 3' FWD | Converts RNA to sequence-ready libraries with barcoding for multiplexing |

| Exome Capture Panels | SureSelect Human All Exon, Illumina Exome Panel | Enriches for exonic regions in targeted RNA-seq approaches |

| Sequencing Kits | Illumina NovaSeq reagents, Nanopore SQK-RNA002 | Provides enzymes and buffers for the sequencing reaction itself |

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

- Input Material: Process 10-200 ng of total RNA extracted from tumor tissues (fresh frozen or FFPE) or cell lines. For FFPE samples, assess RNA integrity (RIN > 7.0) using TapeStation 4200 or similar systems [5].

- RNA Isolation: Use specialized kits (e.g., AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit) that maintain RNA integrity while co-purifying DNA for integrated analyses [5].

- Quality Metrics: Confirm RNA quantity using Qubit fluorometry and purity via Nanodrop (A260/280 ratio >1.8). For single-cell RNA-seq, assess cell viability (>90%) before loading on partitioning systems [3].

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Poly(A) Selection: Enrich for mRNA using oligo(dT) magnetic beads (e.g., NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module) to remove ribosomal RNA [2].

- cDNA Synthesis: Perform reverse transcription using strand-switching protocols for full-length cDNA generation, particularly critical for long-read sequencing [2].

- Library Construction: Prepare sequencing libraries using platform-specific kits (e.g., TruSeq stranded mRNA kit for Illumina, ONT cDNA-PCR Sequencing Kit for Nanopore) with unique dual indexing to enable sample multiplexing [5].

- Sequencing Parameters: For NovaSeq 6000 systems, target 30-50 million paired-end reads (2×150 bp) per sample for whole transcriptome analysis, with Q30 scores >90% indicating high-quality data [5].

Bioinformatics Analysis Pipeline

The computational analysis of RNA-seq data requires a multi-step pipeline to transform raw sequencing reads into biologically meaningful results:

Quality Control and Preprocessing: Assess raw read quality using FastQC, then remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases with Trimmomatic or similar tools. For long-read data, apply Porechop for adapter trimming and quality filtering (Phred score <7 or length <200 bp) [2].

Alignment and Quantification: Map processed reads to reference genome (GRCh38) using STAR aligner for short reads or minimap2 for long reads. For transcript-level quantification, use Kallisto or Salmon for pseudoalignment, generating gene-level count matrices [5].

Differential Expression Analysis: Identify significantly dysregulated genes using packages like DESeq2 or limma, applying thresholds of adjusted p-value <0.05 and |log2FC| >0.585 [6].

Advanced Applications:

- Alternative Splicing Analysis: Use rMATS or SUPPA2 to detect significantly differential splicing events from short-read data, or FLAIR pipeline for long-read data to characterize full-length isoforms [2].

- Variant Calling: Detect expressed mutations using RNA-specific variant callers like Pisces, applying filters for tumor VAF ≥0.05 and depth ≥10 reads [5].

- Cell Type Deconvolution: Estimate cellular composition from bulk RNA-seq data using CIBERSORT or similar tools, leveraging single-cell RNA-seq references [6].

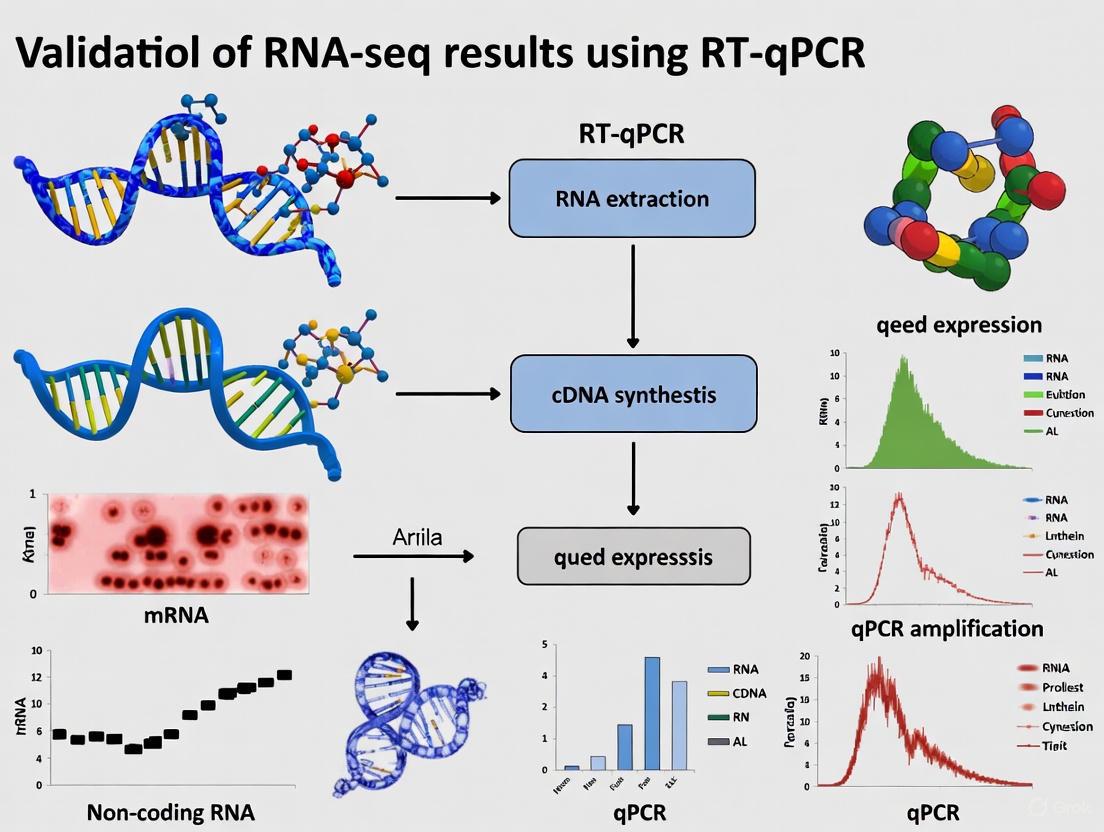

Diagram 1: RNA-seq analysis workflow for cancer research, showing the integrated steps from sample collection to computational analysis and validation.

Validation of RNA-seq Findings: The RT-qPCR Framework

Establishing a Validation Pipeline

The transition from RNA-seq discovery to validated biomarkers requires rigorous confirmation using orthogonal methods. RT-qPCR serves as the gold standard for validating RNA-seq findings due to its superior sensitivity, precision, and cost-effectiveness for analyzing specific targets. The validation framework encompasses several critical phases:

Target Selection and Prioritization

- Identify candidate biomarkers from RNA-seq data based on statistical significance (adjusted p-value), magnitude of expression changes (fold-change), and biological relevance to cancer pathways.

- Prioritize genes with consistent expression patterns across multiple samples and those belonging to coherent biological pathways identified through GO and KEGG enrichment analyses [6].

Experimental Validation Protocol

- Primer Design: Design exon-spanning primers (amplicon size 70-200 bp) to avoid genomic DNA amplification. Validate primer specificity using BLAST and check for secondary structure.

- cDNA Synthesis: Reverse transcribe 500 ng-1 μg of total RNA using high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kits with random hexamers and RNase inhibitor.

- qPCR Amplification: Perform triplicate reactions using SYBR Green or TaqMan chemistry on real-time PCR systems. Include negative controls (no template) and reference genes for normalization.

- Data Analysis: Calculate relative expression using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method with stable reference genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB). Assess statistical significance using Student's t-test or ANOVA.

Performance Assessment

- Evaluate the correlation between RNA-seq and RT-qPCR results using Pearson correlation coefficient (typically R² > 0.8 indicates strong concordance).

- Assess diagnostic accuracy through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, calculating area under the curve (AUC) values for biomarker performance [6].

Case Studies in Validation

Recent studies exemplify the successful application of this validation framework:

Bladder Carcinoma Biomarkers: Single-cell RNA-seq analysis of bladder carcinoma identified 49 genes associated with prognosis. Researchers validated the expression of top candidates (IGFBP5, KRT14, and SERPINF1) using RT-qPCR and western blot in normal (SV-HUC-1) and BC cell lines (T24, J82, EJ, UM-UC-3, 5637, RT112), confirming significant elevation in cancer cells [3].

Breast-Thyroid Cancer Hub Genes: Integrated analysis of transcriptomic data from breast and thyroid cancers identified seven hub genes using machine learning approaches. RT-qPCR validation in patient tumor tissues confirmed that PILRA, Mki67, and UBE2C showed markedly different expression between cancerous and adjacent normal tissues, establishing them as cross-cancer diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers [6].

RNA-seq in Clinical Applications: From Biomarkers to Precision Medicine

Biomarker Discovery and Validation

RNA-seq has dramatically accelerated the pace of biomarker discovery in oncology, enabling the identification of molecular signatures with diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive utility:

Table 3: Clinically Relevant Biomarkers Discovered Through RNA-seq Approaches

| Cancer Type | Biomarker Signature | Clinical Utility | Validation Method | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder Carcinoma | 17-gene prognostic signature (including IGFBP5, KRT14, SERPINF1) [3] | Survival prediction, risk stratification | RT-qPCR, Western blot | Stratified patients into high/low-risk with significant survival difference (p<0.001) |

| Head & Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma | OncoPrism 62-feature immunomodulatory signature [1] | Predicts response to anti-PD-1 therapy | Multisite clinical validation | Specificity 3× higher than PD-L1 IHC, 4× higher sensitivity than TMB |

| Breast & Thyroid Cancers | PILRA, MKI67, UBE2C [6] | Diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers for both cancers | RT-qPCR, IHC in clinical samples | Significant differential expression in tumor vs. normal tissues (p<0.05) |

| Pan-Cancer | PAM50 50-gene signature [7] | Breast cancer classification, treatment guidance | Multiple clinical validations | Accurately classifies breast cancer into intrinsic subtypes |

Integration with Artificial Intelligence

The combination of RNA-seq with artificial intelligence represents a paradigm shift in cancer diagnostics and biomarker discovery:

Machine Learning Classification: Deep learning models applied to RNA-seq data have achieved remarkable accuracy in cancer type classification. One study demonstrated 99.87% accuracy in classifying cancer types using support vector machines on RNA-seq gene expression data [8]. Another approach utilizing convolutional neural networks classified cancer subtypes with approximately 100% accuracy across multiple datasets [9].

Feature Selection: AI algorithms efficiently identify the most informative genes from large-scale RNA-seq datasets. Explainable AI (XAI) approaches have successfully distilled 58,735 input genes down to 99 potential biomarkers for different cancer types, enabling more focused validation efforts [9].

Predictive Modeling: AI-powered analysis of RNA-seq data can predict treatment responses and patient outcomes. For immune checkpoint inhibitors, RNA-based classifiers have demonstrated superior predictive performance compared to traditional PD-L1 immunohistochemistry, with approximately 79% sensitivity and 70% specificity in predicting disease control [1].

Diagram 2: Integration of RNA-seq data with AI for clinical applications in oncology, showing the workflow from raw data to clinical decision support.

RNA-seq has unequivocally established itself as the discovery powerhouse in cancer research, enabling comprehensive characterization of the transcriptome at unprecedented resolution. The technology continues to evolve, with emerging trends including multi-omics integration, single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, and liquid biopsy applications that profile circulating RNA biomarkers. As these advancements mature, the role of RNA-seq in clinical decision-making will expand, necessitating robust validation frameworks like RT-qPCR to ensure translational reliability.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the strategic implementation of RNA-seq technologies—coupled with rigorous validation—offers a powerful pathway to uncover novel cancer biomarkers, elucidate disease mechanisms, and advance precision oncology. By objectively comparing platform performance and providing standardized experimental protocols, this guide aims to support the research community in harnessing the full potential of RNA-seq as an indispensable tool in the fight against cancer.

In the era of high-throughput genomics, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has dramatically expanded our understanding of cancer biology. However, this powerful discovery engine requires a reliable validation mechanism to confirm its findings. Despite the emergence of advanced digital PCR and broader panel-based next-generation sequencing (NGS), reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) maintains its position as the gold standard for validating RNA-seq results in oncology research and clinical diagnostics. Its unique combination of analytical sensitivity, cost-effectiveness, and rapid turnaround solidifies its indispensable role in translating genomic discoveries into clinically actionable insights.

Performance Comparison: RT-qPCR Versus Alternative Methods

The selection of a validation methodology balances multiple factors including precision, throughput, cost, and technical feasibility. The table below provides a systematic comparison of RT-qPCR against other common techniques used in gene expression analysis.

Table 1: Comparison of Gene Expression Analysis and Validation Methods

| Method | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Ideal Use Case in Oncology |

|---|---|---|---|

| RT-qPCR | High sensitivity and specificity; cost-effective; fast turnaround (hours); excellent quantitative capabilities; high throughput potential [10]. | Limited to known/targeted sequences; multiplexing capability is restricted compared to NGS [10] [11]. | Gold-standard validation of RNA-seq findings; high-throughput screening of known biomarkers; clinical diagnostics in time-sensitive scenarios [12] [10]. |

| RNA-seq | Discovery-driven; whole-transcriptome, hypothesis-free approach; can identify novel transcripts and splice variants [13]. | Higher cost; longer turnaround time; complex data analysis and interpretation; requires independent validation [10]. | Exploratory research to define transcriptional landscapes; discovery of novel biomarkers and fusion genes. |

| Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Provides spatial context within tissue architecture; protein-level information; established clinical gold standard for many markers [14] [15]. | Semi-quantitative; subjective interpretation; susceptibility to pre-analytical and analytical variability [12] [15]. | Complementing molecular data with protein expression and localization in tumor tissues. |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) | Absolute quantification without standard curves; high precision for detecting rare variants and minimal residual disease [10]. | Even more limited multiplexing than qPCR; higher cost per sample than qPCR. | Ultra-sensitive detection of low-frequency mutations and circulating tumor DNA. |

RT-qPCR's value is particularly evident in clinical oncology settings. A 2021 comparative study on breast cancer biomarkers found that RT-qPCR showed a high degree of correlation with IHC for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and HER2. Notably, the study suggested that RT-qPCR, with its wider dynamic range and higher reproducibility, could offer a more precise assessment, potentially resolving equivocal HER2 cases and improving Ki67 standardization [12] [15].

RT-qPCR in Action: Validating RNA-seq Discoveries in Breast Cancer

A robust application of RT-qPCR for validation is demonstrated in a 2023 study that developed a novel multiplex RT-qPCR assay to diagnose breast cancer subtypes [14]. The workflow and findings from this study exemplify best practices in the field.

Experimental Protocol and Workflow

The study utilized 61 formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) breast tumor samples, representing various subtypes (Luminal, TN, HER2+, etc.), which were previously classified by IHC [14].

- RNA Extraction: Total RNA was extracted from FFPE samples using a commercial kit, and concentration and purity were assessed with a spectrophotometer [14].

- Multiplex RT-qPCR: The researchers employed a touch-down multiplex RT-qPCR protocol. The assay was strategically divided into three reactions per sample:

- Reaction 1: ESR (ER), PGR (PR), HER2, and the reference gene RPL13A.

- Reaction 2: Ki67 and RPL13A.

- Reaction 3: Angiogenesis genes (HIF1A, ANG, VEGFR) and RPL13A [14].

- Data Analysis: Cycle threshold (CT) values were determined. The ΔCT values for target genes were calculated using RPL13A as the endogenous control and then mathematically inverted and normalized to the IHC scoring scale to enable direct comparison [14].

The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow for validating RNA-seq findings and subtyping tumors using RT-qPCR.

Key Experimental Findings and Data Correlation

The study generated precise quantitative data that underscored RT-qPCR's utility. The table below summarizes the key gene expression findings and their clinical relevance.

Table 2: Key Gene Expression Profiles and Clinical Correlations from a Breast Cancer RT-qPCR Study [14]

| Gene / Marker | Measured Parameter | Clinical/Biological Correlation |

|---|---|---|

| HER2, ESR, PGR, Ki67 | Gene expression profiles | Accurately classified breast cancer subtypes with precision nearly equivalent to IHC [14]. |

| Angiogenesis Genes (HIF1A, VEGFR) | Elevated expression levels | Indicated higher metastatic potential, suggesting utility as biomarkers for assessing tumor aggressiveness [14]. |

| Touch-down PCR Protocol | Significantly lower CT values | Improved annealing efficiency and overall assay accuracy and reliability [14]. |

| Multiplex Assay Format | Simultaneous detection of multiple targets | Enabled comprehensive subtyping and characterization from minimal sample material [14]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Successful RT-qPCR validation relies on a suite of optimized reagents and tools. The following table details key components and their functions for robust assay development.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RT-qPCR in Oncology

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Key Considerations for Oncology Applications |

|---|---|---|

| qPCR Master Mix | Provides optimized buffer, enzymes, and dNTPs for efficient amplification. | Select inhibitor-resistant formulations for challenging clinical samples (e.g., from FFPE, plasma). Prioritize mixes with high sensitivity for low-abundance targets and efficient multiplexing capabilities [10]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA) from RNA templates. | Choose enzymes with high thermal stability to handle RNA with extensive secondary structure. Consider RNase H+ variants for enhanced qPCR efficiency [11]. |

| Reference Genes | Endogenous controls for data normalization. | Critical for accuracy. Must be stably expressed across all sample types and cancer conditions. Tools like GSV software can identify optimal reference genes from RNA-seq data, avoiding traditionally unstable housekeeping genes [13] [16]. |

| Primers & Probes | Sequence-specific oligonucleotides for target amplification and detection. | Design to span exon-exon junctions to avoid genomic DNA amplification. Verify specificity and efficiency. Hydrolysis (TaqMan) or hybridization probes are used in multiplex assays [14] [11]. |

| RNA Isolation Kit | Purifies intact, high-quality RNA from biological samples. | Must be optimized for specific starting materials common in oncology, such as FFPE tissues, cell-free DNA, or fine-needle aspirates, which often yield fragmented or low-concentration nucleic acids [14] [10]. |

In the rigorous field of oncology research, where findings must be reliably translated into clinical practice, RT-qPCR remains the undisputed validation gold standard. Its strengths are not merely historical but are continually reinforced by its quantitative precision, operational efficiency, and practical accessibility. While RNA-seq serves as a powerful discovery platform, RT-qPCR provides the essential verification step, ensuring that transcriptional discoveries are accurate, reproducible, and clinically meaningful. As precision medicine continues to evolve, the synergy between broad-scale sequencing and targeted, reliable validation via RT-qPCR will remain a cornerstone of progress in the fight against cancer.

In translational cancer research, the journey from a basic science discovery to a clinically applicable diagnostic or therapeutic is fraught with challenges. A cornerstone of this process is the rigorous validation of genomic data, ensuring that molecular findings are reliable and actionable. This guide objectively compares two key technologies for gene expression analysis—RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)—within the critical context of validation workflows.

Table of Contents

- Technology Comparison: RNA-seq vs. RT-qPCR

- Experimental Protocols for Validation

- The Validation Workflow

- The Scientist's Toolkit

Technology Comparison: RNA-seq vs. RT-qPCR

RNA-seq has become a powerful discovery tool, but RT-qPCR remains the established gold standard for validating its findings due to its superior sensitivity, simplicity, and cost-effectiveness for targeting specific genes [17] [18]. The following table outlines their complementary roles.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of RNA-seq and RT-qPCR

| Feature | RNA-seq | RT-qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Role | Discovery, hypothesis generation [17] | Targeted validation, clinical testing [17] [18] |

| Throughput | Genome-wide, profiling all genes simultaneously [17] | Low to medium, analyzes one or a few genes at a time [17] |

| Dynamic Range | Large [17] | Large [17] |

| Sensitivity | High | Very High [17] |

| Key Advantages | Detects novel transcripts, fusion genes, and alternative splicing; high reproducibility [17] | High sequence-specificity; considered the gold standard for copy number quantification; cost-effective for targeted work [17] |

| Key Limitations | High cost per sample; complex data analysis requires a bioinformatician [17] | Requires prior knowledge of gene sequence; results can show variability between labs [17] |

| Ideal Use Case | Unbiased discovery of differentially expressed genes and novel pathways in tumor samples [17] | Confirmatory testing of specific gene signatures identified by RNA-seq in a larger patient cohort [19] |

Performance benchmarking studies reveal a strong correlation between the two technologies. One study comparing multiple RNA-seq analysis workflows against whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR data found high gene expression and fold-change correlations (R² > 0.93 for fold-changes) [18]. Approximately 85% of genes showed consistent differential expression results between RNA-seq and RT-qPCR [18]. However, a small, specific set of genes (e.g., those that are smaller, have fewer exons, or are lowly expressed) may show inconsistent results and require careful validation [18]. In specialized applications like measuring the expression of highly polymorphic genes like HLA, the correlation can be more moderate (rho between 0.2 and 0.53), highlighting the need for tailored bioinformatic pipelines and careful interpretation [20].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: RNA-seq Analysis Workflow

RNA-seq data processing involves converting raw sequencing reads into a gene expression count matrix. The following steps are critical [21]:

- Quality Control (QC): Assess raw sequencing reads (in FASTQ format) for potential technical errors, adapter contamination, and base quality using tools like FastQC or multiQC [21].

- Read Trimming: Clean the data by removing low-quality bases and adapter sequences using software such as Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, or fastp [21].

- Read Alignment/Mapping: Map the cleaned reads to a reference genome or transcriptome to identify their genomic origin. Common aligners include STAR or HISAT2. An alternative, faster approach is pseudo-alignment with Kallisto or Salmon, which estimates transcript abundance without full base-by-base alignment [21] [18].

- Post-Alignment QC: Remove poorly aligned or ambiguously mapped reads using tools like SAMtools or Picard to prevent inaccurate quantification [21].

- Read Quantification: Count the number of reads mapped to each gene, producing a raw count matrix. This is done with tools like featureCounts or HTSeq-count [21]. The resulting count matrix is the foundation for identifying differentially expressed genes.

Protocol 2: RT-qPCR Validation Protocol

Validating RNA-seq hits with RT-qPCR requires meticulous execution [22].

- RNA Sample: Use the same RNA samples that were subjected to RNA-seq. Quality is critical: RNA should be high-quality, intact, and free of genomic DNA contamination. Using an RNA stabilization reagent is recommended [22].

- Primer and Probe Design: Design primers (and probes for TaqMan assays) to be sequence-specific. Software should be used to optimize parameters like melting temperature (Tm) and avoid secondary structures. To avoid amplifying genomic DNA, design primers to span an exon-exon junction [22]. Alternatively, use predesigned, validated assays.

- Reverse Transcription and qPCR Setup: Convert RNA to cDNA using a reverse transcriptase enzyme. For the qPCR reaction, use a master mix containing all necessary reagents (polymerase, dNTPs, buffers) to minimize well-to-well variation. Always include essential controls:

- No Template Control (NTC): Contains water instead of template cDNA; checks for reagent contamination.

- No Amplification Control (NAC): Contains RNA but no reverse transcriptase; checks for genomic DNA contamination [22].

- Data Normalization: The accuracy of RT-qPCR relies on proper normalization using stably expressed reference genes (e.g., 18S rRNA). The expression of the target gene is normalized to the reference gene(s) to correct for variations in RNA input and efficiency of the RT reaction [23] [24] [22]. Research shows that using a pre-validated combination of non-stable genes can sometimes outperform single "housekeeping" genes [24].

- Data Analysis: Set the baseline and threshold correctly to determine the quantification cycle (Cq). The PCR efficiency should be between 90–110% for accurate relative quantification using the comparative delta-delta-Ct method [22].

The Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, cyclical process of using RNA-seq and RT-qPCR to move a finding from discovery to clinical application.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful validation experiments depend on key reagents and computational tools.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for RNA-seq and RT-qPCR Validation

| Item | Function | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization Solution | Preserves RNA integrity in fresh tissue samples prior to extraction [22]. | Critical for ensuring that degradation does not skew expression results. |

| Quality Control Tools (e.g., FastQC, MultiQC) | Assesses the quality of raw RNA-seq data and identifies technical biases [21]. | The first essential step in any RNA-seq workflow; poor QC can invalidate an entire experiment. |

| Alignment/Pseudoalignment Software (e.g., STAR, Kallisto) | Maps sequencing reads to a reference genome or transcriptome for quantification [21] [18]. | Choice affects speed and accuracy; pseudo-aligners are faster and require less memory. |

| qPCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed solution containing polymerase, dNTPs, and optimized buffers for qPCR [22]. | Minimizes well-to-well variation and improves reproducibility. Use a mix with a reference dye (like ROX) for further normalization. |

| Validated Reference Genes | Endogenous controls used to normalize RT-qPCR data for technical variability [23] [24]. | Stability must be confirmed for the specific tissue and experimental conditions; using a combination of genes is often best. |

| Predesigned TaqMan Assays | Optimized primer and probe sets for specific gene targets [22]. | Eliminates the need for in-house design and optimization, saving time and ensuring performance. |

| DNA Decontamination Solution | Destroys contaminating DNA amplicons on work surfaces and equipment [22]. | Vital for preventing false positives in sensitive qPCR reactions. |

The path from a genomic discovery to a tool that can impact patient care is complex. By understanding the complementary strengths of RNA-seq and RT-qPCR and implementing a rigorous validation workflow, researchers can enhance the reliability of their data, bridge the gap between bench and clinic, and ultimately contribute to more effective cancer diagnostics and therapies.

In the era of precision oncology, RNA biomarkers have emerged as powerful tools for improving cancer diagnosis, prognostication, and therapy selection. These biomarkers originate from various RNA classes, each with distinct biological characteristics and clinical applications. Messenger RNAs (mRNAs) provide direct insight into protein-coding gene activity, while non-coding RNAs—including microRNAs (miRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and circular RNAs (circRNAs)—regulate complex cellular processes through sophisticated networks. The validation of findings from high-throughput RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) technologies using reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) represents a critical methodological pipeline in biomarker development. This comparative guide examines the four key RNA biomarker classes, their experimental validation, and their integration into clinical cancer research.

Comparative Analysis of RNA Biomarker Classes

Table 1: Comparative overview of key RNA biomarker classes in cancer research

| Biomarker Class | Key Characteristics | Primary Functions | Stability in Biofluids | Representative Cancer Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | Protein-coding transcripts, 500-5000+ nucleotides | Direct template for protein synthesis | Moderate (protected in exosomes) | Stool-based CRC screening [25], multi-gene expression panels [26] |

| miRNA | Short non-coding RNAs, ~22 nucleotides | Post-transcriptional gene regulation, mRNA degradation/repression | High (resistant to RNase degradation) | Serum panels for RCC [27], plasma exosomal for CNS tumors [28] |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNAs, >200 nucleotides | Chromatin modification, transcriptional regulation, miRNA sponging | Variable (cell-type specific expression) | Diagnostic markers in PTC [29], component of ceRNA networks [30] |

| circRNA | Covalently closed circular structures | miRNA sponging, protein scaffolding, translation | High (resistant to exonuclease degradation) | Biomarkers in intrauterine adhesion [31], cancer pathways [32] |

Table 2: Experimental validation data for representative RNA biomarkers across cancer types

| Biomarker | RNA Class | Cancer Type | Detection Method | Performance (AUC) | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20-gene mRNA panel [25] | mRNA | Colorectal Cancer | Stool-based RT-qPCR | 0.94 (CRC), 0.83 (AA) | Early detection of CRC and advanced adenomas |

| 3-miRNA panel (miR-30c-5p, miR-142-3p, miR-206) [27] | miRNA | Renal Cell Carcinoma | Serum RT-qPCR | 0.872 | Differentiating RCC patients from healthy controls |

| 3-miRNA panel (miR-148a-3p, miR-345-5p, miR-4433b-5p) [28] | miRNA | PCNSL vs. GBM | Plasma exosomal RT-qPCR | 0.791 | Differentiating CNS lymphomas from glioblastomas |

| GAS5 [29] | lncRNA | Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma | Tissue RT-qPCR | 0.87 (aggressiveness) | Identifying aggressive tumor subtypes |

| circMET [29] | circRNA | Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma | Tissue analysis | 0.81 (vs. normal) | Diagnostic marker across PTC stages |

| hsacirc0000994 [31] | circRNA | Intrauterine Adhesion | Endometrial tissue RT-qPCR | Functional validation | Promising therapeutic target for fibrosis |

mRNA Biomarkers: Protein-Coding Transcripts in Cancer Diagnostics

mRNAs represent the most directly interpretable RNA biomarker class, reflecting active protein-coding gene expression. Their expression patterns provide valuable insights into cellular states in health and disease. In oncology, mRNA biomarkers can detect aberrant expression of oncogenes, tumor suppressor genes, and genes involved in critical cancer pathways.

A prime example of mRNA biomarker application comes from colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. A recent bioinformatics-driven approach identified a 20-gene mRNA panel for stool-based detection of CRC and advanced adenomas (precancerous lesions). The study utilized publicly available RNA-seq data from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) databases, analyzing 478 colon cancer tissues and 692 normal colon/rectum tissues. Genes were ranked based on differential expression across tumors and expression level in tumor tissue. When validated on 114 clinical stool samples using RT-qPCR, the panel demonstrated an area under the receiver operator curve (AUC) of 0.94 for CRC detection (75.5% sensitivity, 95% specificity) and 0.83 for advanced adenoma detection (55.8% sensitivity, 92.6% specificity) [25].

The PAM50 breast cancer classifier represents another successful mRNA biomarker application, utilizing a 50-gene expression panel to classify breast cancer into intrinsic subtypes (Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2-enriched, Basal-like, and Normal-like), guiding treatment decisions [26]. Similarly, the 50-gene panel known as PAM50 has been effectively used for breast cancer (BC) classification [26].

miRNA Biomarkers: Potent Regulators with Clinical Utility

miRNAs are short non-coding RNA molecules that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally by binding to complementary sequences in target mRNAs, leading to translational repression or mRNA degradation. Their remarkable stability in blood and other body fluids, even under harsh conditions, makes them exceptionally suitable as non-invasive biomarkers [27].

Several miRNA biomarkers have shown promising diagnostic potential across various cancers. In renal cell carcinoma (RCC), a three-miRNA panel (miR-30c-5p, miR-142-3p, and miR-206) demonstrated strong diagnostic performance with an AUC of 0.872, 81.25% sensitivity, and 86.90% specificity for distinguishing RCC patients from healthy subjects. This study employed a rigorous multi-phase approach, initially screening candidate miRNAs from the ENCORI database, followed by RT-qPCR validation in training (28 RCC vs. 28 healthy controls) and validation phases (80 RCC vs. 84 healthy controls) [27].

In neuro-oncology, differentiating primary central nervous system lymphoma (PCNSL) from glioblastoma (GBM) represents a significant diagnostic challenge with therapeutic implications. A recent study identified a plasma exosomal miRNA signature (hsa-miR-148a-3p, hsa-miR-345-5p, and hsa-miR-4433b-5p) that could distinguish these malignancies with an AUC of 0.791. The study combined miRNA sequencing with RT-qPCR validation in 27 PCNSL and 27 GBM patients, followed by functional validation showing that miR-4433b-5p directly targets EGFR, which is differentially expressed between these tumors [28].

lncRNA and circRNA Biomarkers: Emerging Players in RNA Networks

lncRNAs and circRNAs represent more recently characterized RNA classes that function as crucial regulators of gene expression through diverse mechanisms, including participation in competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) networks.

Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs)

lncRNAs exceed 200 nucleotides in length and lack protein-coding potential. They function through various mechanisms, including chromatin modification, transcriptional regulation, and post-transcriptional processing. Their cell type-specific expression patterns make them particularly attractive as cancer biomarkers [30].

In papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), the lncRNA GAS5 was identified as a key diagnostic and prognostic marker through comprehensive ceRNA network analysis. GAS5 expression demonstrated strong diagnostic value in distinguishing high-aggression from low-aggression PTC tumors (AUC = 0.87) and showed association with blood calcium levels, suggesting clinical relevance beyond tumor classification [29].

Circular RNAs (circRNAs)

circRNAs are characterized by their covalently closed circular structure, resulting from back-splicing events. This structure confers exceptional stability due to resistance to exonuclease-mediated degradation. circRNAs function predominantly as miRNA sponges, protein scaffolds, and in some cases, can be translated into peptides [31] [32].

In intrauterine adhesion (IUA), hsacirc0000994 was identified through RNA sequencing and validated via RT-qPCR as significantly upregulated in IUA samples. Functional experiments demonstrated that silencing hsacirc0000994 with siRNA in vitro significantly decreased expression levels of fibrosis markers α-SMA and COL1A1 in human endometrial stromal cells treated with TGF-β1, suggesting a role in modulating fibrosis and positioning it as a promising therapeutic target [31].

Advanced computational tools like CIRI3 have enabled more comprehensive circRNA analysis in large datasets. CIRI3 demonstrates superior performance in circRNA detection and quantification, processing a 295-million-read dataset in just 0.25 hours (8-149 times faster than other tools) while maintaining high accuracy [32].

The ceRNA Network: Integrative RNA Cross-Talk in Cancer

The competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) hypothesis proposes that RNA transcripts (including lncRNAs, circRNAs, and mRNAs) communicate by competing for shared miRNA response elements (MREs). This network represents a complex regulatory layer in cancer biology, where imbalance can drive oncogenesis [30] [29].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of the ceRNA network:

CeRNA Network Core Mechanism. This diagram illustrates how different RNA species (lncRNAs, circRNAs, pseudogenes) compete for binding to shared microRNA response elements (MREs), thereby modulating mRNA expression and protein translation. The balance of these interactions plays a critical role in cancer development and progression [30] [29].

A comprehensive multi-network analysis of PTC constructed a five-layer ceRNA network containing 33 components and an associated transcription factor regulatory network. This integrated approach identified reliable diagnostic markers for PTC, including PKMYT1, E2F1, NFATC1, STAT6, E2F3, LINC02910, GAS5, and TK1, which collectively achieved an AUC of 96.9% for PTC diagnosis [29].

Experimental Workflow: From RNA-Seq Discovery to RT-qPCR Validation

The standard pipeline for RNA biomarker development involves discovery through high-throughput sequencing followed by validation using targeted methods. The following diagram outlines this key experimental workflow:

RNA Biomarker Validation Workflow. This diagram outlines the standard pipeline for RNA biomarker development, from initial sample collection through RNA-seq discovery to final RT-qPCR validation in independent cohorts, ensuring robust and clinically applicable biomarkers.

The critical importance of RT-qPCR validation was demonstrated in the colorectal cancer mRNA biomarker study, where the Pearson correlation coefficient between tissue and stool expression was 0.57 (p-value = 0.007), confirming that tissue transcriptomics can productively identify stool-based mRNA biomarkers with clinical utility [25].

Research Reagent Solutions for RNA Biomarker Studies

Table 3: Essential research reagents and tools for RNA biomarker discovery and validation

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Stabilization | RNA later, TRIzol LS | Preserve RNA integrity in biological samples | Critical for clinical samples with low RNA quality |

| RNA Extraction Kits | RNeasy Mini Kit, miRNeasy | Isolate high-quality total RNA | Select based on RNA size (small vs. large RNAs) |

| Library Prep Kits | NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit | Prepare sequencing libraries | Strand-specific protocols preserve directionality |

| Computational Tools | CIRI3, edgeR, DESeq2, Limma | Detect circRNAs, perform differential expression | CIRI3 offers superior speed for large datasets [32] |

| qPCR Systems | SYBR Green, TaKaRa kits, Bulge-Loop miRNA primers | Quantitative validation of candidates | miRNA-specific primers needed for accurate quantification |

| Reference Databases | TCGA, GTEx, GEO, circBase | Access expression data, annotation | Essential for bioinformatic ranking of candidates [25] |

The four classes of RNA biomarkers—mRNAs, miRNAs, lncRNAs, and circRNAs—offer complementary insights into cancer biology and present unique advantages for clinical application. mRNAs provide direct information about protein-coding potential, while non-coding RNAs regulate complex networks that drive cancer progression. The integration of these biomarkers into ceRNA networks provides a more comprehensive understanding of cancer pathogenesis.

The pipeline from RNA-seq discovery to RT-qPCR validation remains fundamental for biomarker development, ensuring that findings from high-throughput screening are confirmed using targeted, quantitative methods in independent patient cohorts. As computational tools advance and our understanding of RNA networks deepens, RNA biomarkers are poised to play an increasingly prominent role in precision oncology, enabling earlier detection, accurate stratification, and personalized therapeutic interventions for cancer patients.

The field of oncology is undergoing a transformative shift with the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and RNA biomarker research, creating a new paradigm for precision medicine. Cancer continues to be a significant global health challenge, resulting in approximately 10 million deaths annually [33]. The limitations of traditional diagnostic methods and the complexity of cancer biology have necessitated more sophisticated approaches to early detection, prognosis, and treatment selection. RNA biomarkers, including messenger RNAs (mRNAs), microRNAs (miRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), have emerged as crucial molecular signatures that provide deep insights into tumor behavior and therapeutic response [26]. Unlike DNA-based biomarkers, RNA expression profiles capture the dynamic functional state of cells, reflecting both genetic and environmental influences on cancer progression [34].

The implementation of AI, particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms, has revolutionized how researchers analyze complex RNA datasets. AI-powered approaches can efficiently decipher intricate RNA expression patterns, discover novel biomarkers, and elucidate their functional roles in cancer biology—tasks that often exceed the capabilities of conventional statistical methods [26] [33]. This synergy between AI and RNA biomarkers is enhancing every aspect of cancer management, from early detection and subtype classification to prognosis prediction and treatment response monitoring [26]. As the WINTHER trial—the first prospective study in diverse solid malignancies to integrate both genomics and transcriptomics—demonstrated, incorporating RNA expression data increases the number of targetable molecular alterations compared to genomic profiling alone [34]. This review examines the technical landscape of RNA biomarker validation, focusing specifically on the critical relationship between next-generation RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) methodologies, while exploring how AI technologies are transforming biomarker discovery and application in clinical oncology.

RNA Biomarker Classes and Their Clinical Significance in Cancer

The RNA universe encompasses diverse molecular species with distinct functional roles in cancer pathogenesis, making them valuable as diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarkers. mRNAs represent the most extensively studied RNA class, serving as intermediaries between genes and proteins. In cancer research, multi-gene expression patterns have been successfully employed as biomarkers for clinical outcomes. For example, the 50-gene PAM50 panel is effectively used for breast cancer classification, while mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes serve as excellent biomarkers for cancer risk assessment [26].

Beyond mRNAs, non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) constitute a rapidly expanding category of biomarkers with significant regulatory functions:

- MicroRNAs (miRNAs): Short RNA molecules (approximately 18-25 nucleotides) that regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally. They function as oncogenes or tumor suppressors and are stable in bodily fluids, making them ideal non-invasive biomarkers [26] [35].

- Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs): Transcripts exceeding 200 nucleotides that interact with DNA, RNA, and proteins to regulate cellular processes including proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis [26] [35].

- Circular RNAs (circRNAs): Covalently closed loop structures that function as miRNA "sponges," sequestering miRNAs and thereby relieving their repression of target mRNAs [26].

Recent technological advances have also enabled the detection of extracellular RNAs (exRNAs) in biological fluids such as blood, saliva, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid. These exRNAs include miRNA, siRNA, piRNA, snoRNA, tRNA, circRNA, and lncRNA, offering tremendous potential for liquid biopsy applications in oncology [26]. The table below summarizes key RNA biomarker classes and their clinical applications in cancer.

Table 1: RNA Biomarker Classes and Their Clinical Applications in Cancer

| RNA Class | Size/Features | Primary Functions | Clinical Applications in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | Variable length, protein-coding | Information transfer from DNA to protein | Multi-gene signatures for prognosis (e.g., PAM50 for breast cancer classification) [26] |

| miRNA | 18-25 nucleotides | Post-transcriptional gene regulation | Early detection, subtype classification, treatment response monitoring [26] [35] |

| lncRNA | >200 nucleotides | Gene regulation via DNA/RNA/protein interactions | Prognosis prediction, therapeutic target identification [26] [35] |

| circRNA | Covalently closed loops | miRNA spongeing, regulatory functions | Diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers across multiple cancer types [26] |

| exRNA | Various types in biofluids | Cell-cell communication | Liquid biopsies for non-invasive cancer detection and monitoring [26] |

AI-driven approaches are particularly valuable for analyzing these diverse RNA biomarker classes, as ML and DL algorithms can identify complex, non-intuitive patterns from vast transcriptomic datasets that conventional analytical methods might overlook [33]. For instance, AI-powered models have demonstrated effectiveness in categorizing cancer subtypes based on miRNA expression profiles, predicting patient outcomes using lncRNA signatures, and monitoring treatment responses through circulating RNA patterns [26].

Analytical Methodologies: Comparing RNA-seq and RT-qPCR Platforms

The accurate detection and quantification of RNA biomarkers rely on robust analytical platforms, with RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) and reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) representing the principal technologies currently employed in research and clinical settings. Each method offers distinct advantages and limitations, making them complementary rather than competing approaches in biomarker development.

RNA-seq is a high-throughput technology that enables comprehensive profiling of the entire transcriptome without requiring prior knowledge of transcript sequences. This methodology provides an unbiased view of the RNA landscape, allowing researchers to detect novel transcripts, alternative splicing events, fusion genes, and various non-coding RNA species [18] [34]. The key advantages of RNA-seq include its broad dynamic range, sensitivity for detecting low-abundance transcripts, and ability to identify novel RNA biomarkers. However, RNA-seq presents challenges related to data complexity, computational requirements, cost considerations for targeted applications, and technical variability introduced during library preparation [18] [36].

RT-qPCR remains the gold standard for targeted gene expression quantification due to its exceptional sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and cost-effectiveness for analyzing a limited number of targets [18] [36]. This method is particularly valuable for validating biomarker candidates identified through discovery-based approaches like RNA-seq. While traditional RT-qPCR workflows require separate reactions for different RNA biotypes due to their distinct structural features, recent technological advancements have addressed this limitation. The novel SMART-qPCR method enables simultaneous detection of small RNAs (e.g., miRNAs) and long RNAs (e.g., mRNAs, lncRNAs) in a single reaction tube, simplifying workflows and reducing sample requirements to the single-cell level [35].

The following diagram illustrates the key decision points when selecting between these analytical platforms for RNA biomarker studies:

Figure 1: RNA Analysis Platform Selection Guide. The diagram illustrates decision pathways for selecting appropriate RNA analysis platforms based on research objectives, highlighting how both RNA-seq and RT-qPCR feed into AI-powered data analysis for clinical application.

The integration of both platforms often provides the most robust approach to biomarker development, with RNA-seq enabling comprehensive discovery phases and RT-qPCR providing rigorous validation of candidate biomarkers. This complementary relationship is particularly valuable in clinical translation, where RT-qPCR offers a more practical methodology for implementation in diagnostic laboratories [36].

Experimental Data Comparison: RNA-seq versus RT-qPCR Performance Metrics

Independent benchmarking studies provide critical insights into the comparative performance of RNA-seq and RT-qPCR for gene expression quantification. A comprehensive study evaluated five RNA-seq analysis workflows (Tophat-HTSeq, Tophat-Cufflinks, STAR-HTSeq, Kallisto, and Salmon) against whole-transcriptome RT-qPCR expression data for 18,080 protein-coding genes using the well-established MAQCA and MAQCB reference samples [18].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of RNA-seq Analysis Workflows Against RT-qPCR Reference

| Analysis Workflow | Expression Correlation with RT-qPCR (R²) | Fold Change Correlation with RT-qPCR (R²) | Non-concordant Genes* | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salmon | 0.845 | 0.929 | 19.4% | Speed, accuracy for transcript quantification |

| Kallisto | 0.839 | 0.930 | 18.7% | Rapid pseudoalignment, minimal computational requirements |

| Tophat-HTSeq | 0.827 | 0.934 | 15.1% | Established alignment-based approach, reliable gene counts |

| STAR-HTSeq | 0.821 | 0.933 | 15.3% | Accurate splicing alignment, fast processing |

| Tophat-Cufflinks | 0.798 | 0.927 | 16.9% | Transcript assembly and quantification capabilities |

*Non-concordant genes defined as those with discrepant differential expression calls between RNA-seq and RT-qPCR [18]

The benchmarking revealed high overall concordance between RNA-seq and RT-qPCR technologies, with expression correlations ranging from R² = 0.798 to 0.845 and fold change correlations from R² = 0.927 to 0.934 across different workflows [18]. Despite this strong overall agreement, approximately 15-19% of genes showed inconsistent differential expression calls between RNA-seq and RT-qPCR. These discrepant genes tended to share specific characteristics: they were typically smaller, had fewer exons, and showed lower expression levels compared to genes with consistent measurements [18]. This finding highlights the importance of platform-specific validation for particular gene sets.

In clinical applications, particularly for human leukocyte antigen (HLA) expression analysis—critical for cancer immunotherapy—studies have demonstrated moderate correlation between RNA-seq and RT-qPCR (0.2 ≤ rho ≤ 0.53 for HLA-A, -B, and -C) [20]. This moderate correlation underscores the technical challenges in quantifying extremely polymorphic genes and emphasizes the need to account for methodological differences when comparing expression results across platforms or studies.

The emerging SMART-qPCR technology addresses several limitations of conventional approaches by enabling simultaneous detection of miRNAs, mRNAs, and other small non-coding RNAs in a single reaction tube from minimal input material, including single cells [35]. This unified workflow enhances detection efficiency, reduces hands-on time and reagent consumption, and shows strong potential for point-of-care diagnostic applications.

AI-Enhanced Biomarker Discovery: Transforming RNA Data Analysis

Artificial intelligence has emerged as a transformative force in RNA biomarker research, enabling the extraction of clinically relevant insights from complex transcriptomic datasets that would be inaccessible through conventional analytical approaches. Machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms excel at identifying subtle, non-intuitive patterns within high-dimensional RNA expression data, facilitating the discovery of novel biomarker signatures with diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive utility [33].

In cancer diagnostics, AI-powered approaches have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in analyzing RNA expression patterns to improve early detection and classification. For instance, support vector machines (SVMs) and neural networks trained on circulating RNA data can accurately differentiate between benign and malignant breast diseases [26]. Similarly, AI algorithms have proven effective in categorizing cancer subtypes based on miRNA expression profiles, achieving diagnostic precision beyond conventional histopathological methods [26]. These capabilities are particularly valuable for interpreting complex data from liquid biopsies, where AI can detect subtle RNA signatures indicative of early-stage malignancies that might otherwise be missed.

The prognostic applications of AI-derived RNA biomarkers are equally promising. Predictive models utilizing lncRNA signatures have shown considerable effectiveness in forecasting patient outcomes and treatment responses, enabling more personalized intervention strategies [26]. In immunotherapy, AI can identify biomarker signatures that help distinguish patients most likely to respond to checkpoint inhibitors from those who will not, optimizing treatment selection and avoiding unnecessary toxicity [33]. The Predictive Biomarker Modeling Framework (PBMF) employs contrastive learning to systematically extract predictive biomarkers from rich clinical data, with retrospective studies demonstrating significant improvements in patient survival through its predictive capabilities [33].

The following diagram illustrates how AI integrates with RNA biomarker data to enhance clinical decision-making:

Figure 2: AI-Driven RNA Biomarker Analysis Workflow. The diagram illustrates how AI technologies integrate multi-modal data inputs to generate clinically actionable outputs for precision oncology.

Explainable AI (XAI) frameworks represent a particularly significant advancement, as they enhance the interpretability of AI models by providing insights into the specific biomarkers and features driving predictions. For example, an XAI-based deep learning framework for biomarker discovery in non-small cell lung cancer has demonstrated how explainable models can assist clinical decision-making by highlighting the specific RNA biomarkers most associated with treatment response [33]. This transparency builds trust among clinicians and facilitates the integration of AI-derived insights into routine clinical practice.

Integrated Validation Workflow: From RNA-seq Discovery to RT-qPCR Confirmation

The successful translation of RNA biomarkers from discovery to clinical application requires a rigorous validation workflow that leverages the complementary strengths of RNA-seq and RT-qPCR technologies. This multi-stage process ensures that candidate biomarkers identified through high-throughput screening demonstrate robust performance in targeted assays suitable for clinical implementation.

A recommended validation workflow comprises the following key stages:

Discovery Phase: Comprehensive transcriptomic profiling using RNA-seq to identify differentially expressed RNA biomarkers across comparison groups (e.g., tumor vs. normal, responsive vs. non-responsive to treatment). This hypothesis-generating stage leverages the unbiased nature of RNA-seq to detect novel transcripts, splice variants, and non-coding RNAs potentially associated with disease states [18] [34].

Biomarker Prioritization: Application of AI/ML algorithms to identify the most promising biomarker candidates from discovery data. Feature selection techniques can prioritize RNAs based on effect size, statistical significance, predictive power, and biological relevance. Integration with multi-omics data (genomics, proteomics) provides additional context for biomarker selection [33].

Technical Validation: Development and optimization of RT-qPCR assays for selected biomarkers. This stage includes designing specific primers and probes, determining optimal reaction conditions, and establishing performance parameters (sensitivity, specificity, dynamic range, reproducibility) [35] [36].

Biological Validation: Assessment of biomarker performance in independent patient cohorts using RT-qPCR. This critical step verifies that candidate biomarkers maintain their diagnostic, prognostic, or predictive utility across different sample sets and population groups [18].

Clinical Implementation: Translation of validated RT-qPCR assays into clinically applicable formats, such as standardized test kits. This process includes extensive verification studies, compliance with regulatory requirements, and potentially development as companion diagnostics for specific therapies [37].

The SMART-qPCR protocol represents a significant advancement in validation methodology by enabling simultaneous detection of multiple RNA biotypes (miRNAs, mRNAs, sncRNAs) in a single reaction tube from minimal input material [35]. This approach addresses key limitations of conventional methods that require separate workflows for different RNA classes, reducing sample requirements, simplifying procedures, and enabling direct correlation of different RNA species within the same biological context.

For AI-derived biomarker signatures, the validation workflow must also include computational verification to ensure model robustness and generalizability. This involves testing AI algorithms on independent datasets, assessing performance across diverse patient populations, and implementing explainable AI approaches to provide biological plausibility for the identified biomarker patterns [33] [38].

Essential Research Reagents and Technologies for RNA Biomarker Studies

The successful implementation of RNA biomarker research requires specialized reagents and technologies that ensure accurate, reproducible, and clinically relevant results. The following table catalogizes key solutions essential for various stages of biomarker discovery and validation workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies for RNA Biomarker Studies

| Category | Specific Solutions | Key Applications | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction & Quality Control | RNeasy kits (Qiagen), TRIzol reagent, Bioanalyzer/RNA integrity assessment | Sample preparation for downstream analysis, RNA quality verification | Purity (A260/280 ratio), integrity (RIN >7), yield quantification [20] |

| Library Preparation | TruSeq RNA Library Prep (Illumina), Ion AmpliSeq Transcriptome | RNA-seq library construction, target enrichment | Input requirements, compatibility with RNA biotypes, coverage uniformity [36] |

| qPCR Reagents | TaqMan Gene Expression Assays, SYBR Green master mixes, SMART-qPCR reagents | Target validation, expression quantification | Sensitivity (detection limit), specificity, dynamic range, multiplexing capability [35] [36] |

| Reference Materials | Universal Human Reference RNA, Human Brain Reference RNA (MAQC samples) | Platform benchmarking, assay standardization, quality control | Inter-laboratory reproducibility, expression profile stability [18] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | HTSeq, Cufflinks, Kallisto, Salmon, PandaOmics | RNA-seq data analysis, biomarker discovery, AI-powered pattern recognition | Algorithm accuracy, computational efficiency, user accessibility [26] [33] [18] |

The selection of appropriate reagents and technologies should be guided by specific research objectives, sample characteristics, and intended clinical applications. For discovery-phase studies requiring comprehensive transcriptome characterization, RNA-seq platforms with broad dynamic range and minimal technical bias are essential. For clinical validation and implementation, RT-qPCR reagents offering high sensitivity, reproducibility, and compatibility with standardized workflows are preferable [36].

Recent innovations such as SMART-qPCR have expanded methodological capabilities by enabling simultaneous detection of small and long RNAs in a single reaction vessel, overcoming traditional limitations that required separate workflows for different RNA biotypes [35]. This integrated approach reduces sample requirements, simplifies experimental procedures, and minimizes technical variability—particularly valuable when working with precious clinical specimens or limited material such as liquid biopsies.

Quality control remains paramount throughout the biomarker development pipeline. The use of standardized reference materials, such as those established in the MAQC (MicroArray Quality Control) consortium studies, enables robust benchmarking of platform performance and facilitates comparison of results across different laboratories and studies [18]. Implementation of rigorous quality metrics ensures that RNA biomarkers meet the stringent requirements for clinical application in precision oncology.

The convergence of AI technologies with RNA biomarker research represents a paradigm shift in precision oncology, offering unprecedented opportunities to improve cancer detection, treatment selection, and patient outcomes. The synergistic relationship between discovery-oriented RNA-seq platforms and validation-focused RT-qPCR methods creates a robust framework for translating transcriptomic findings into clinically applicable biomarkers. This integrated approach leverages the comprehensive profiling capabilities of RNA-seq while utilizing the sensitivity, specificity, and practicality of RT-qPCR for clinical implementation [18] [36].

Artificial intelligence serves as the critical intermediary in this process, enhancing every stage from initial biomarker discovery through clinical validation. ML and DL algorithms can decipher complex patterns within high-dimensional RNA expression data that elude conventional analytical methods, identifying subtle biomarker signatures with diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive utility [26] [33]. The emerging field of explainable AI further strengthens this approach by providing biological insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying AI-derived biomarker patterns, building clinician trust and facilitating adoption into routine practice [33].

Despite these promising advancements, challenges remain in the widespread implementation of AI-driven RNA biomarkers. Issues of data quality, algorithmic transparency, regulatory alignment, and ethical considerations must be addressed to ensure robust, equitable, and clinically meaningful applications [33] [38]. The establishment of standardized validation frameworks—incorporating both computational verification and wet-laboratory confirmation—will be essential for translating AI-discovered biomarkers into clinically validated assays.

Looking forward, the integration of multi-omics data—combining transcriptomics with genomics, proteomics, epigenetics, and tumor immune profiling—will provide increasingly comprehensive insights into cancer biology and therapeutic vulnerabilities [34]. As AI methodologies continue to evolve and RNA analysis technologies become more sophisticated and accessible, the vision of truly personalized cancer management based on individual molecular profiles moves closer to realization. Through continued innovation and collaboration across computational biology, molecular pathology, and clinical oncology, AI-enhanced RNA biomarker research will play an increasingly central role in reducing the global cancer burden and improving patient care throughout the cancer journey.

From Data to Validation: Step-by-Step Methodological Frameworks for Reliable Results

In cancer research, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become the predominant method for transcriptome-wide analysis, enabling the discovery of novel transcripts and quantification of differential gene expression. A critical challenge in experimental design involves balancing sequencing depth, the number of biological replicates, and read parameters to maximize statistical power while efficiently utilizing resources. This guide objectively compares these design parameters and provides methodologies for validating RNA-seq findings through RT-qPCR, a crucial step for verifying gene expression patterns in cancer studies before proceeding with functional assays.

Sequencing Depth vs. Biological Replication: A Quantitative Trade-off

The allocation of sequencing resources between depth and replication represents one of the most significant design decisions in RNA-seq studies. Empirical evidence strongly favors increasing biological replication over sequencing depth for most experimental scenarios.

Table 1: Impact of Replication and Sequencing Depth on Differential Expression Detection

| Biological Replicates | Sequencing Depth (M reads) | Total Reads (M) | Detected DE Genes | Power Increase | Key Observations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 10 | 20 | 2011 | Baseline | - |

| 2 | 15 | 30 | 2139 | +6% | 50% more reads, minimal gain |

| 3 | 10 | 30 | 2709 | +35% | Same total reads, substantial gain |

| 2 | 30 | 60 | 2522 | +27% | Triple reads/sample, moderate gain |

| 3 | 30 | 90 | 3447 | +35% (vs 2@30) | - |

| 6 | 10 | 60 | ~26% more vs 3@10 | Diminishing returns | Still significant power gain |

Data adapted from Liu et al. (2013) shows that adding biological replicates provides substantially more power for detecting differentially expressed (DE) genes than increasing sequencing depth, with diminishing returns observed only at higher replication levels [39].

Sequencing depth follows a principle of diminishing returns, with studies indicating that 10 million reads often detects approximately 80% of annotated transcripts [40]. Beyond 10-15 million reads per sample, the additional power to detect DE genes decreases substantially, except for low-abundance transcripts which benefit from greater depth [39] [41].

Experimental Design Parameters and Recommendations

Biological vs. Technical Replication

Biological replicates (samples from different biological sources) are essential for capturing population-level variation and enabling robust statistical inference. Technical replicates (repeated measurements of the same biological sample) show minimal variation in RNA-seq and are generally not recommended as they add little power while consuming resources [42] [39]. For accurate measurement of biological variance, each biological replicate should undergo separate library preparation rather than pooling samples before sequencing [42].

Sequencing Configuration: Paired-End vs. Single-End

The choice between paired-end (PE) and single-end (SE) sequencing depends on the research objectives and available resources.

Table 2: Comparison of Sequencing Read Configurations

| Parameter | Single-End Sequencing | Paired-End Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | Lower | Higher |

| Gene Quantification | Sufficient for most DE studies | Enhanced accuracy |

| Splice Junction Detection | Limited | Superior |

| Novel Transcript Discovery | Limited | Significantly improved |

| Isoform Resolution | Limited | Excellent |

| Application in Cancer Research | Suitable when budget constrained, focused on highly expressed genes | Preferred for isoform discovery, fusion genes, comprehensive transcriptome characterization |

For cancer studies investigating alternative splicing, gene fusions, or novel transcripts, PE sequencing is strongly recommended despite the higher cost [42]. For standard differential expression analysis, SE sequencing may be sufficient when combined with adequate biological replication.

Read Length Considerations

While standard RNA-seq utilizes 50-100 bp reads, longer reads (150-300 bp) significantly improve mapping accuracy, particularly for transcript isoform discrimination and genes with paralogs [43]. Longer reads are especially beneficial for resolving complex viral transcriptomes in cancer virology studies and for characterizing fusion genes in oncology research [43].

Experimental Protocols for RNA-seq and RT-qPCR Validation

RNA-seq Library Preparation and Sequencing

A standard RNA-seq workflow for cancer studies should include:

- RNA Extraction and Quality Control: Use high-quality RNA (RNA Integrity Number ≥ 8) extracted from cancer cell lines or tissues. Verify quality using Bioanalyzer or similar systems [39].

- ibrary Preparation: Employ either poly-A enrichment for mRNA sequencing or ribosomal RNA depletion to capture non-coding RNAs. The Illumina TruSeq RNA sample preparation protocol is widely used [39].

- Barcoding and Multiplexing: Incorporate unique dual indices (UDIs) to enable sample multiplexing. This allows distributing samples across sequencing lanes to mitigate batch effects and technical variation [42].

- Sequencing Parameters: For standard differential expression studies in cancer, aim for 20-30 million PE reads (75-100 bp) per sample when using sufficient biological replicates (n≥5) [39] [40].

Validation of RNA-seq Results with RT-qPCR

Validating RNA-seq findings with RT-qPCR remains essential in cancer research, particularly for candidate biomarkers or therapeutic targets.

- Gene Selection: Choose 10-20 significantly differentially expressed genes from RNA-seq analysis, representing various expression levels and fold-changes.

- Reference Gene Validation: Carefully select and validate reference genes for normalization. Commonly used reference genes (e.g., ACTB, GAPDH, RPS genes) may show variable expression under different experimental conditions in cancer cells. For example, in dormant cancer cells generated through mTOR inhibition, ACTB, RPS23, RPS18, and RPL13A expression undergoes dramatic changes, making them unsuitable for normalization [44]. Instead, validate stable reference genes such as B2M and YWHAZ for specific cancer cell types [44].

- Primer Design: Design primers with:

- Amplicon size: 70-200 bp (especially important for FFPE samples)

- Efficiency: 90-110%

- Specificity: Verify with melt curve analysis and gel electrophoresis

- Avoid polymorphic regions in cancer genes [44]

- qPCR Protocol:

- Use 20-100 ng cDNA per reaction

- Perform technical triplicates

- Include no-template controls

- Use SYBR Green or TaqMan chemistry

- Standard cycling conditions: 95°C for 10 min, then 40 cycles of 95°C for 15s and 60°C for 1 min

- Data Analysis: Apply the ΔΔCt method using validated reference genes. Compare fold-change values between RNA-seq and qPCR using correlation analysis (Pearson or Spearman). Studies show high fold-change correlation (R² > 0.93) between RNA-seq and qPCR for the majority of genes, though a subset (approximately 15%) may show inconsistent results [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq and Validation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | RNeasy kits (Qiagen), TRIzol | High-quality RNA isolation from cells and tissues |

| RNA Quality Assessment | Bioanalyzer (Agilent), TapeStation | RNA integrity verification pre-library preparation |

| Library Prep Kits | TruSeq RNA Library Prep (Illumina), NuGEN Ovation | cDNA synthesis, adapter ligation, library amplification |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Ribozero (Illumina), NEBNext rRNA Depletion | Removal of ribosomal RNA for total RNA sequencing |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR Green, TaqMan assays (Thermo Fisher) | Fluorescence-based detection of amplified DNA in qPCR |

| Reference Gene Assays | PrimePCR assays (Bio-Rad), custom-designed primers | Normalization of qPCR data using stable reference genes |

| Reverse Transcriptase | SuperScript IV (Invitrogen), LunaScript | High-efficiency cDNA synthesis from RNA templates |

Analysis Workflow Considerations