Validating Pharmacophore Models with Experimental IC50 Values: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating pharmacophore models through experimental IC50 values.

Validating Pharmacophore Models with Experimental IC50 Values: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating pharmacophore models through experimental IC50 values. It covers the foundational principles of pharmacophore modeling and the role of IC50 as a key potency metric. The guide details methodological approaches for model validation, including decoy set tests, ROC curve analysis, and cost-function analysis. It further addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies to enhance model robustness. Finally, it explores advanced validation and comparative techniques, such as multi-complex-based modeling and machine learning integration, synthesizing key takeaways and future directions for integrating computational predictions with experimental biology to improve the efficiency of drug discovery.

Laying the Groundwork: Understanding Pharmacophore Models and IC50 Validation

The pharmacophore concept stands as a fundamental pillar in modern rational drug design. According to the official IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) definition, a pharmacophore represents "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [1]. This definition emphasizes that a pharmacophore is not a real molecule or a specific association of functional groups, but rather an abstract concept that captures the common molecular interaction capacities of a group of compounds toward their target structure [2]. In practical terms, a pharmacophore describes the key structural features and their spatial arrangement that enable a molecule to bind to its biological target and elicit a biological response.

The historical development of the pharmacophore concept reveals an evolution in understanding. While often erroneously credited to Paul Ehrlich, modern research indicates the term was actually popularized by Lemont Kier in the late 1960s and early 1970s [3]. The concept has since evolved from simple chemical functionality descriptions to sophisticated three-dimensional models that account for molecular conformation and preferred interaction geometries [2]. This conceptual framework has proven invaluable in bridging the gap between molecular structure and biological activity, enabling researchers to identify structurally diverse compounds that share common binding characteristics.

Core Pharmacophore Features and Modeling Approaches

Fundamental Pharmacophore Features

Pharmacophore models abstract specific chemical groups into generalized molecular interaction features. The core feature types include:

- Hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA): Atoms that can accept hydrogen bonds

- Hydrogen bond donors (HBD): Atoms or groups that can donate hydrogen bonds

- Hydrophobic regions: Non-polar areas that favor hydrophobic interactions

- Aromatic rings: Planar ring systems enabling π-π interactions

- Positive ionizable groups: Areas that can carry or develop positive charges

- Negative ionizable groups: Areas that can carry or develop negative charges

These features are typically represented in 3D space with defined geometries and tolerances [3]. For example, hydrogen bond donors and acceptors are often represented as vectors indicating the preferred direction of interaction, while hydrophobic and aromatic features are represented as volumes or points in space.

Pharmacophore Modeling Methodologies

The development of a robust pharmacophore model generally follows a systematic process, with approaches categorized based on available structural information:

Table 1: Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

| Approach | Data Requirements | Methodology | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand-based | Set of known active compounds | Molecular superimposition of active compounds to identify common features | Virtual screening when target structure is unknown |

| Structure-based | 3D protein structure | Analysis of binding site properties and complementary features | Structure-based drug design, virtual screening |

| Complex-based | Protein-ligand complex structures | Extraction of interaction features from crystallized complexes | High-confidence modeling, scaffold hopping |

The standard workflow for pharmacophore model development involves: (1) selecting a training set of ligands with known activities, (2) conducting conformational analysis to identify low-energy conformations, (3) molecular superimposition to align common features, (4) abstraction of aligned molecules into pharmacophore features, and (5) model validation against compounds with known activities [3]. This process can be implemented using software tools such as MOE, LigandScout, Phase, and Catalyst/Discovery Studio [2].

Comparative Analysis: Pharmacophore-Based vs. Docking-Based Virtual Screening

Virtual screening represents one of the most practical applications of pharmacophore models in drug discovery. To evaluate the effectiveness of pharmacophore-based approaches, we compare them directly with molecular docking-based methods across multiple protein targets.

Experimental Protocol for Method Comparison

A comprehensive benchmark study compared Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening (PBVS) against Docking-Based Virtual Screening (DBVS) using eight structurally diverse protein targets: angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE), acetylcholinesterase (AChE), androgen receptor (AR), D-alanyl-D-alanine carboxypeptidase (DacA), dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), estrogen receptors α (ERα), HIV-1 protease (HIV-pr), and thymidine kinase (TK) [4]. The experimental protocol was as follows:

Data Set Preparation: For each target, an active dataset containing experimentally validated compounds was constructed. Two decoy datasets (Decoy I and Decoy II) composed of approximately 1000 compounds each were generated to test screening specificity.

Pharmacophore Model Generation: Pharmacophore models were constructed based on several X-ray crystal structures of each target protein in complex with ligands using the LigandScout program [4].

Virtual Screening Execution: Each compound database was screened using:

- PBVS: Implemented with Catalyst software

- DBVS: Implemented with three docking programs (DOCK, GOLD, and Glide)

Performance Evaluation: Screening effectiveness was measured using enrichment factors (EF) and hit rates (HR), calculated at the top 2% and 5% of the ranked databases [4].

Performance Comparison Results

The comparative analysis revealed significant differences in screening performance between the two approaches:

Table 2: Virtual Screening Performance Comparison

| Target | Screening Method | Enrichment Factor | Hit Rate @2% | Hit Rate @5% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE | PBVS | 24.5 | 22.1 | 18.7 |

| DBVS (Best) | 18.3 | 16.4 | 14.2 | |

| AChE | PBVS | 28.3 | 25.7 | 21.9 |

| DBVS (Best) | 21.7 | 19.2 | 16.8 | |

| DHFR | PBVS | 26.8 | 24.3 | 20.5 |

| DBVS (Best) | 20.9 | 18.5 | 15.9 | |

| HIV-pr | PBVS | 30.2 | 27.8 | 23.4 |

| DBVS (Best) | 23.1 | 20.7 | 17.6 | |

| Average across 8 targets | PBVS | 26.4 | 23.8 | 20.3 |

| DBVS (Best) | 20.6 | 18.3 | 15.7 |

Of the sixteen sets of virtual screens (eight targets against two testing databases), PBVS demonstrated higher enrichment factors in fourteen cases compared to DBVS methods [4]. The average hit rates over the eight targets at 2% and 5% of the highest ranks of the entire databases for PBVS were significantly higher than those for DBVS, establishing PBVS as a powerful method for retrieving active compounds from chemical databases [4].

Virtual Screening Comparison Workflow

Experimental Validation Through IC₅₀ Determination

Case Study: AChE Inhibitor Discovery with Experimental Validation

The ultimate validation of any pharmacophore model comes from experimental confirmation of predicted bioactive compounds. A recent study on acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease demonstrates this validation process [5].

Experimental Protocol:

- Pharmacophore Model Ensemble Development: The dyphAI approach integrated machine learning models, ligand-based pharmacophore models, and complex-based pharmacophore models into a pharmacophore model ensemble capturing key protein-ligand interactions.

Virtual Screening: The protocol identified 18 novel molecules from the ZINC database with promising binding energy values ranging from -62 to -115 kJ/mol.

Experimental Testing: Nine molecules were acquired and tested for inhibitory activity against human AChE, with the control compound galantamine serving as reference.

Results and IC₅₀ Validation: The experimental testing provided crucial validation of the pharmacophore models:

Table 3: Experimental IC₅₀ Validation of AChE Inhibitors

| Compound ID | Structural Features | Predicted Binding Energy (kJ/mol) | Experimental IC₅₀ | Validation Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P-1894047 | Complex multi-ring structure, numerous H-bond acceptors | -98 | Lower than control | Potent inhibition confirmed |

| P-2652815 | Flexible polar framework, 10 H-bond donors/acceptors | -115 | Equal to control | Potent inhibition confirmed |

| P-1205609 | Balanced hydrophobicity, moderate flexibility | -84 | Strong inhibition | Activity confirmed |

| P-617769798 | Rigid framework, limited interaction features | -62 | Higher than control | Weak activity |

| Galantamine (Control) | Natural product framework | N/A | Reference value | Benchmark compound |

The study demonstrated that molecules with higher pharmacophore complementarity generally exhibited lower IC₅₀ values (greater potency), validating the predictive capability of the pharmacophore models [5]. Compounds 4 (P-1894047) and 7 (P-2652815) exhibited IC₅₀ values lower than or equal to the control galantamine, indicating potent inhibitory activity confirmed through experimental testing [5].

Modern Computational Advances in Pharmacophore Modeling

AI-Enhanced Pharmacophore Approaches

Recent advances in artificial intelligence have significantly transformed pharmacophore-based drug discovery:

PGMG (Pharmacophore-Guided deep learning approach for bioactive Molecule Generation): This approach uses a graph neural network to encode spatially distributed chemical features and a transformer decoder to generate molecules. A latent variable is introduced to solve the many-to-many mapping between pharmacophores and molecules to improve diversity [6].

TransPharmer: This generative model integrates ligand-based interpretable pharmacophore fingerprints with a GPT-based framework for de novo molecule generation. The model excels in unconditioned distribution learning and scaffold elaboration under pharmacophoric constraints, demonstrating particular strength in scaffold hopping [7].

PharmacoForge: A diffusion model for generating 3D pharmacophores conditioned on a protein pocket. This approach generates pharmacophore queries that identify ligands guaranteed to be valid, commercially available molecules, addressing synthetic accessibility concerns [8].

Performance Benchmarks of AI-Enhanced Methods

Comparative studies demonstrate the effectiveness of these modern approaches:

Table 4: Performance Metrics of AI-Enhanced Pharmacophore Methods

| Method | Validity Score | Uniqueness | Novelty | Docking Affinity | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGMG | 0.957 | 0.998 | 0.845 | Strong | Flexible generation without fine-tuning |

| TransPharmer | 0.978 | 0.997 | 0.891 | Strong superior | Scaffold hopping capability |

| Traditional PBVS | N/A | N/A | N/A | Moderate | Proven reliability, extensive validation |

| DBVS | N/A | N/A | N/A | Variable | Direct binding site modeling |

In benchmark evaluations, PGMG generated molecules with strong docking affinities and high scores of validity (0.957), uniqueness (0.998), and novelty (0.845) [6]. TransPharmer achieved even higher validity (0.978) while maintaining strong uniqueness (0.997) and novelty (0.891), demonstrating the rapid advancement in the field [7].

Pharmacophore Model Validation Workflow

Essential Research Tools and Reagents

Successful implementation of pharmacophore-based drug discovery requires specific computational and experimental resources:

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Reagent | Category | Function | Example Sources/Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software | Structure-based pharmacophore modeling | Intel:Ligand |

| Catalyst | Software | Pharmacophore-based virtual screening | BIOVIA/Dassault Systèmes |

| ZINC Database | Chemical Database | Commercially available compounds for virtual screening | University of California, San Francisco |

| Binding Database | Bioactivity Data | Experimentally validated IC₅₀ values | BindingDB |

| Protein Data Bank | Structural Data | 3D protein structures for structure-based design | Worldwide PDB |

| Schrödinger Suite | Modeling Platform | Comprehensive molecular modeling environment | Schrödinger LLC |

| AutoDock | Docking Software | Molecular docking for binding affinity prediction | Scripps Research |

| CETSA | Experimental Assay | Target engagement validation in intact cells | Pelago Bioscience |

The evolution of the pharmacophore concept from its historical origins to precise IUPAC standards has established it as a fundamental principle in drug discovery. Through rigorous comparative studies, pharmacophore-based virtual screening has demonstrated superior performance in enrichment factors and hit rates compared to docking-based approaches across multiple target classes. The validation of pharmacophore models through experimental IC₅₀ determination remains crucial, as evidenced by case studies where computationally identified compounds demonstrated potent biological activity. Modern AI-enhanced approaches have further expanded capabilities, enabling more effective exploration of chemical space while maintaining key interaction patterns. As computational methods continue to advance, integration with experimental validation will remain essential for developing predictive pharmacophore models that accelerate drug discovery.

The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) stands as a fundamental metric in pharmacological research and drug discovery, providing a crucial quantitative measure of compound potency. This parameter represents the concentration of an inhibitory substance required to reduce a specific biological or biochemical function by half [9]. Within pharmacophore model validation, experimentally derived IC50 values serve as an essential experimental anchor, verifying that computationally identified molecular features translate to tangible biological activity. This review examines the true meaning of IC50, its methodological determination, relationship to binding affinity, and strategic application in validating virtual screening workflows for robust drug development.

IC50 is a quantitative measure that indicates how much of a particular inhibitory substance is needed to inhibit, in vitro, a given biological process or biological component by 50% [9]. The biological component under investigation can range from purified enzymes and cellular receptors to whole cells and microorganisms. As a measure of functional potency, IC50 provides critical information about the biological effectiveness of a compound under specific experimental conditions, making it indispensable for comparing the potency of different antagonists in pharmacological research [9] [10].

In the context of pharmacophore model validation, IC50 values provide the experimental verification needed to transition from in silico predictions to biologically active compounds. For instance, in virtual screening campaigns aimed at discovering novel inhibitors for targets like Brd4 or Akt2, experimentally determined IC50 values validate whether the pharmacophore features identified through computational methods accurately represent the structural requirements for biological activity [11] [12]. This experimental confirmation establishes a critical bridge between computational predictions and biological relevance, ensuring that identified compounds possess not only structural complementarity but also functional efficacy.

What IC50 Truly Measures: Operational versus Intrinsic Properties

Understanding what IC50 does and does not measure is crucial for its proper interpretation and application in drug discovery.

The Operational Nature of IC50

IC50 is primarily an operational parameter that describes the functional strength of an inhibitory substance under specific assay conditions [13]. It represents the "total" concentration of inhibitor needed to reach 50% inhibition in a particular experimental system [14]. This operational definition distinguishes it from more fundamental thermodynamic constants, as its value can be influenced by numerous experimental variables including:

- Assay duration and conditions

- Cellular context and enzyme concentrations

- Substrate concentrations for enzymatic assays [9] [13]

The concentration-dependent nature of inhibition means that higher concentrations of inhibitor typically lead to progressively lowered biological activity, forming the basis for dose-response curves from which IC50 values are derived [9].

Distinction from Binding Affinity (Ki)

While both IC50 and Ki provide measures of inhibitor potency, they represent fundamentally different concepts:

Table 1: Comparison of IC50 and Ki Parameters

| Parameter | IC50 | Ki |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Functional concentration for 50% inhibition | Dissociation constant for inhibitor binding |

| Nature | Operational, condition-dependent | Intrinsic, thermodynamic |

| Measurement | Derived from dose-response curves | Determined from binding equilibria |

| Dependence | Varies with substrate/enzyme concentration | Constant for a given inhibitor-target pair |

| Units | Molar concentration (M) | Molar concentration (M) |

Ki refers to the inhibition constant describing the binding affinity between the inhibitor and the enzyme, while IC50 is the concentration of inhibitor required to reduce the enzymatic activity to half of the uninhibited value [13]. The relationship between these parameters is mathematically defined by the Cheng-Prusoff equation for competitive inhibition:

[Ki = \frac{IC{50}}{1 + \frac{[S]}{K_m}}]

where Ki is the binding affinity of the inhibitor, IC50 is the functional strength, [S] is the substrate concentration, and Km is the Michaelis constant [9] [13]. This relationship highlights how IC50 values depend on experimental conditions, particularly substrate concentration, while Ki represents an intrinsic property of the inhibitor-target interaction.

Methodological Approaches for IC50 Determination

Accurate determination of IC50 values requires carefully controlled experimental conditions and appropriate analytical methods across different biological contexts.

Experimental Workflows for IC50 Determination

The process of determining IC50 values follows a systematic workflow that can be applied to various experimental systems:

Cell-Based Viability and Functional Assays

In whole-cell systems, IC50 values are commonly determined using viability assays that measure the compound's effect on cellular proliferation or survival. The MTT assay represents a widely used approach that relies on the reduction of MTT to formazan, providing a colorimetric measure of cell viability [15]. In these systems, cells are exposed to a range of inhibitor concentrations, and the resulting data are used to generate dose-response curves from which IC50 values are calculated.

For cellular systems, the percentage of viability is typically calculated as:

[Cell\ viability\ (\%) = \frac{Population{sample}}{Population{control}} \times 100 = \frac{Absorbance{sample}}{Absorbance{control}} \times 100]

The IC50 value denotes the concentration of a compound at which 50% of cell viability is inhibited, serving as a key parameter to assess the effectiveness of potential therapeutic compounds [15]. However, these whole-cell approaches have limitations, as results can depend on the experimental cell line used and may not differentiate a compound's ability to inhibit specific molecular interactions [16].

Biochemical and Biophysical Approaches

For more precise interaction-specific measurements, biophysical techniques like surface plasmon resonance (SPR) can directly determine IC50 values for individual molecular interactions. This approach offers molecular resolution that can help distinguish inhibitors that specifically target individual complexes [16].

In SPR-based inhibition assays, a receptor is captured on a sensor chip, and a fixed concentration of ligand pre-incubated with varying concentrations of inhibitor is injected over the surface. The reduction in binding response with increasing inhibitor concentration is used to calculate the IC50, which can be determined at any point of the association or dissociation phase using standard software such as GraphPad Prism [16]. This approach provides precise characterization of inhibitor potency for specific molecular interactions, complementing cellular activity data.

High-Throughput Screening Applications

In high-throughput drug discovery settings, IC50 determination has been adapted to screen large chemical libraries consisting of 100,000 to over 2 million compounds [10]. In these automated systems, proteins implicated in disease processes are engineered into cells, which are then exposed to compound libraries using liquid handlers. Activity is measured before compound addition to establish baseline inhibition and monitored over time until activity cessation indicates maximal inhibition [10].

Dose-response curves are constructed from wells showing inhibitory effects above a certain threshold, and IC50 values are estimated using logistic regression equations, typically the 4-parameter logistic Hill equation used in dose-response relationships [10]. This high-throughput approach enables rapid potency assessment across vast chemical spaces, though it requires careful optimization to minimize artifacts from liquid handling or reagent interactions.

IC50 in Pharmacophore Model Validation and Virtual Screening

The validation of pharmacophore models through experimental IC50 values represents a critical step in computational drug discovery, establishing a direct link between predicted molecular interactions and biological activity.

Integration with Computational Workflows

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening employs molecular features derived from protein-ligand interactions to identify potential inhibitors from compound databases. The subsequent experimental determination of IC50 values for hit compounds provides essential validation of the pharmacophore model's predictive power [11] [12]. This validation cycle typically involves:

- Pharmacophore model generation based on protein-ligand interactions

- Virtual screening of compound databases

- Hit selection based on molecular docking and drug-likeness filters

- Experimental IC50 determination for validation

- Model refinement based on experimental results

For example, in a study targeting Brd4 for neuroblastoma treatment, a structure-based pharmacophore model was generated and used to screen natural compound databases. The initial 136 identified compounds were further evaluated through molecular docking, ADME analysis, and toxicity assessment, ultimately identifying four compounds with good binding affinity that were stabilized through molecular dynamics simulations [11]. This integrated approach demonstrates how IC50 validation bridges computational predictions and biological activity.

Research Reagent Solutions for IC50 Determination

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Technologies for IC50 Determination

| Reagent/Technology | Function in IC50 Determination | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Label-free quantification of biomolecular interactions and inhibition | Direct measurement of inhibitor potency for specific ligand-receptor pairs [16] |

| MTT Tetrazolium Salt | Colorimetric measurement of cell metabolic activity | Cell viability assays in whole-cell systems [15] |

| Recombinant Proteins | Highly pure protein targets for biochemical assays | Enzymatic inhibition studies and biophysical characterization [16] |

| Validated Inhibitors | Reference compounds with established potency | Assay controls and benchmark comparisons [12] |

| Cell Line Panels | Disease-relevant cellular models | Cellular efficacy assessment and therapeutic potential evaluation [17] |

Critical Considerations and Limitations of IC50 Values

While IC50 values provide essential potency information, their interpretation requires careful consideration of several methodological and conceptual limitations.

Context Dependence and Variability

IC50 values are highly dependent on the experimental conditions under which they are measured [9] [17]. This context dependence manifests in several ways:

- Substrate concentration dependence: For ATP-dependent enzymes, IC50 value has an interdependency with concentration of ATP, especially if inhibition is competitive [9]

- Cellular system variability: Results from whole-cell assays can depend on the experimental cell line used, potentially limiting their ability to differentiate specific interactions [16]

- Temporal dynamics: In cell-based systems, IC50 values can be time-dependent, as both sample and control cell populations evolve over time at different growth rates [15]

Substantial variability in reported IC50 values has been observed even for the same drug and cell line combinations across different studies. For example, literature analysis reveals different IC50 values for 5-fluorouracil in SNU-C4 colorectal adenocarcinoma cells (2.8 ± 0.95 μM versus 3.1 ± 0.9 μM) despite similar experimental conditions [17]. Such variations highlight the importance of standardizing experimental protocols when comparing IC50 values across studies.

Relationship to Therapeutic Potential

While IC50 values provide valuable information about in vitro potency, they represent only one parameter in the complex journey of drug development. Additional factors including cellular permeability, metabolic stability, protein binding, and toxicity profiles collectively determine the ultimate therapeutic utility of a compound [11] [13]. The integration of IC50 data with these additional parameters through comprehensive ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity) analysis provides a more complete picture of a compound's potential for further development [11] [12].

IC50 remains an indispensable parameter in pharmacological research and drug discovery, providing a standardized measure of compound potency across diverse biological systems. Its role in validating pharmacophore models is particularly valuable, establishing experimental verification for computational predictions of biological activity. However, the interpretation of IC50 values requires careful consideration of their operational nature and context dependence. When applied with appropriate understanding of their limitations and in combination with other pharmacological parameters, IC50 values provide critical guidance for compound optimization and selection in the drug discovery pipeline. Their continued evolution through improved assay technologies and analytical approaches will further enhance their utility in translating molecular interactions into therapeutic opportunities.

Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD), particularly pharmacophore modeling, has become an indispensable tool in modern drug discovery, offering the potential to significantly reduce the time and costs associated with bringing new therapeutics to market [18] [19]. Pharmacophore models abstract the essential steric and electronic features necessary for a molecule to interact with a biological target and trigger a pharmacological response [18]. These models are typically generated through either structure-based approaches (using 3D protein structures) or ligand-based methods (using known active compounds) [18]. However, the predictive power of any computational model remains hypothetical until confirmed through experimental validation. This creates a critical "validation gap" between in-silico predictions and biological reality.

The integration of experimental IC50 values—the concentration of a compound required to inhibit a biological process by half—provides a crucial quantitative bridge across this gap [15] [20]. IC50 values serve as a standardized, experimental benchmark for comparing the biological activity of different compounds predicted by pharmacophore models [15]. This review examines the integrated workflows that connect pharmacophore modeling with experimental verification, highlighting protocols, case studies, and the essential reagents that facilitate this crucial bridge in drug development.

Pharmacophore Modeling: Approaches and Validation

Types of Pharmacophore Models

Pharmacophore modeling approaches fall into two primary categories, each with distinct methodologies and applications in drug discovery:

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: This approach relies on the three-dimensional structure of a macromolecular target, often obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy [18]. The process involves analyzing the binding site to identify key interaction points—such as hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and ionizable groups—that are critical for ligand binding [18] [20]. These features are then translated into a pharmacophore hypothesis used for virtual screening. A significant advantage of this method is its ability to identify novel chemotypes without prior knowledge of active ligands [18].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: When the 3D structure of the target protein is unavailable, ligand-based approaches can be employed. This method derives pharmacophore features from a set of known active compounds by aligning them and identifying common chemical functionalities responsible for their biological activity [18]. The quality of the resulting model heavily depends on the structural diversity and conformational representation of the training set molecules.

Validation of Pharmacophore Models

Before deployment in virtual screening, pharmacophore models require rigorous validation to assess their ability to distinguish known active compounds from inactive molecules [11] [20]. The standard validation process involves:

Decoy Sets and ROC Analysis: Models are tested against a database containing known active compounds and decoy molecules (presumed inactives) from resources like the Database of Useful Decoys (DUD-E) [20]. The screening results are evaluated using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves, which plot the true positive rate against the false positive rate [20].

Enrichment Metrics: The Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the ROC plot quantifies the model's overall performance, with values closer to 1.0 indicating excellent discriminatory power [20]. The Enrichment Factor (EF) measures how much more likely the model is to select active compounds compared to random selection, providing additional validation of model quality [11] [20].

Table 1: Key Metrics for Pharmacophore Model Validation

| Metric | Calculation/Interpretation | Optimal Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC (Area Under ROC Curve) | Area under ROC plot | 0.7-0.8 (Good), 0.8-1.0 (Excellent) | Overall model discrimination capability |

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | (Hitselectivity{model} / Hitselectivity{random}) | >1 indicates enrichment | Measure of model efficiency in identifying actives |

| GH Score | Combines true positives and false positives | Closer to 1 indicates better performance | Comprehensive model quality metric |

Integrated Workflows: From In-Silico Prediction to Experimental Confirmation

Comprehensive Workflow Architecture

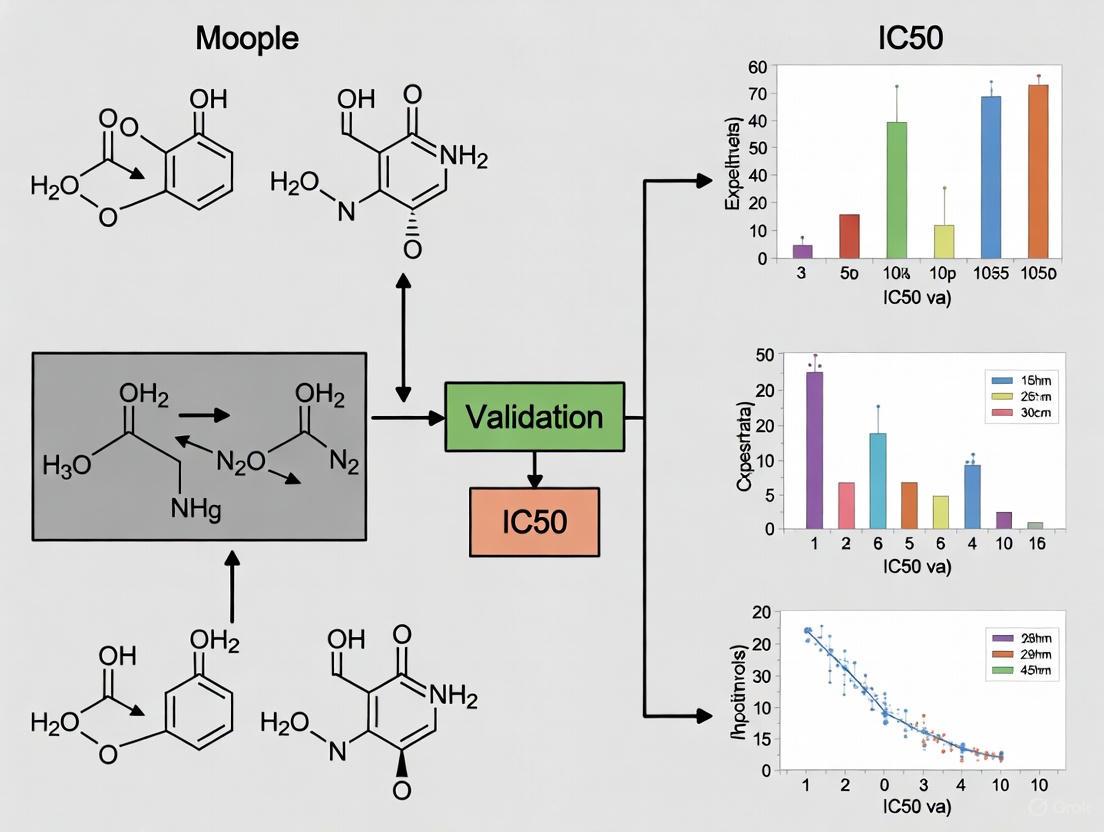

Successful bridging of in-silico and in-vitro approaches requires a systematic, multi-stage workflow. The following diagram illustrates the integrated process from initial model development to experimental confirmation:

Case Studies in Integrated Validation

Several recent studies demonstrate successful implementation of this integrated workflow:

Anti-Cancer Agent Discovery: A study targeting the XIAP protein developed a structure-based pharmacophore model from the protein-ligand complex (PDB: 5OQW) [20]. The model, validated with an excellent AUC of 0.98, was used for virtual screening of natural product libraries. Subsequent molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations identified three promising natural compounds (Caucasicoside A, Polygalaxanthone III, and MCULE-9896837409) with stable binding interactions, suggesting their potential as XIAP-targeted anti-cancer agents [20].

Neuroblastoma Therapeutics: Researchers addressing neuroblastoma developed a structure-based pharmacophore model for the Brd4 protein (PDB: 4BJX) [11]. Virtual screening of natural compound libraries followed by molecular docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulations identified four natural compounds (ZINC2509501, ZINC2566088, ZINC1615112, and ZINC4104882) as promising Brd4 inhibitors with potential therapeutic efficacy against neuroblastoma [11].

SARS-CoV-2 Protease Inhibitors: A structure-based pharmacophore model featuring 9 features was developed to target the SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease (PLpro) [21]. After virtual screening of a marine natural product database and comparative molecular docking, aspergillipeptide F emerged as the top candidate, demonstrating favorable binding interactions across all five binding sites of PLpro, as confirmed by molecular dynamics simulations [21].

Experimental Protocols: Measuring IC50 and Cell Viability

Cell Viability Assay Protocols

The MTT (thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide) assay is a widely used method for assessing cell viability and determining IC50 values in cancer research [15]. The standard protocol involves:

Cell Seeding and Treatment: Cells are seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 100,000 cells/mL in a volume of 100 μL [15]. The chemotherapeutic drug is then added to each well in a range of concentrations, typically using serial dilutions. Each condition should be performed with multiple replicates (typically 3) with independent experiments repeated at least 3 times [15].

MTT Incubation and Measurement: After a specific exposure period (e.g., 24, 48, or 72 hours), the medium is removed and replaced with 50 μL of 0.5 mg/mL MTT solution [15]. Plates are incubated for 4 hours at 37°C, allowing viable cells to reduce MTT to purple formazan crystals. The MTT solution is then removed, and the formazan crystals are dissolved in 100 μL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) [15]. Absorbance is measured at 546 nm using a spectrophotometer [15].

Data Analysis and IC50 Calculation: The percentage of cell viability is calculated by normalizing the absorbance of treated samples to untreated controls [15]. Dose-response curves are generated by plotting percentage viability against drug concentration, and IC50 values are determined using non-linear regression analysis of these curves [15].

Advanced Method: Growth Rate-Based Assessment

Recent advancements in cell viability assessment have introduced more precise parameters that address limitations of traditional IC50 measurements:

Effective Growth Rate Calculation: This method involves calculating the effective growth rate for both control (untreated) cells and cells exposed to a range of drug doses for short times, during which exponential proliferation can be assumed [15]. The cell population as a function of time is modeled as N(t) = N₀·e^(r·t), where r is the growth rate and N₀ is the initial cell population [15].

Novel Parameters: This approach introduces two new parameters for comparing treatment efficacy: ICr₀ (the drug concentration at which the effective growth rate is zero) and ICrmed (the drug concentration that reduces the control population's growth rate by half) [15]. These parameters are time-independent and provide a more direct evaluation of treatment effect on cell proliferation [15].

The following diagram illustrates the IC50 determination process:

Quantitative Data from Validation Studies

Table 2: Experimental IC50 Values from Integrated Validation Studies

| Study Focus | Target Protein | Computational Method | Experimental IC50 | Cell Line/Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XIAP Inhibition [20] | XIAP | Structure-based pharmacophore modeling | Reference compound: 40.0 nM | Various cancer cell lines |

| Brd4 Inhibition [11] | Brd4 | Structure-based pharmacophore modeling | Reference ligand: 21 nM | Neuroblastoma cell lines |

| Breast Cancer [22] | Multiple targets | Network pharmacology + docking | Naringenin demonstrated anti-proliferative effects | MCF-7 human breast cancer cells |

| PLpro Inhibition [21] | SARS-CoV-2 PLpro | Structure-based pharmacophore modeling | Aspergillipeptide F showed strong binding | Virus replication assay |

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

The Scientist's Toolkit

Implementation of the integrated workflows described requires specific research reagents and computational tools. The following table details essential solutions and their applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Application | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| MTT Assay Kit [15] | Cell viability assessment | Measures metabolic activity of cells for IC50 determination |

| Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) [15] | Cell culture | Provides nutrients for cell growth and maintenance |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) [15] | Cell culture supplement | Supplies essential growth factors and hormones |

| DMSO [15] | Solvent | Dissolves formazan crystals in MTT assay; compound solubilization |

| LigandScout Software [11] [20] | Pharmacophore modeling | Generates structure-based pharmacophore models from protein-ligand complexes |

| ZINC Database [11] [20] | Compound library | Source of commercially available compounds for virtual screening |

| AutoDock/AutoDock Vina [21] | Molecular docking | Predicts binding poses and affinities of compounds to target proteins |

| GROMACS/AMBER [11] | Molecular dynamics | Simulates protein-ligand interactions and complex stability |

The integration of in-silico pharmacophore modeling with in-vitro experimental validation represents a powerful paradigm in modern drug discovery. This review has demonstrated through various case studies and methodological frameworks how computational predictions can be effectively bridged with experimental confirmation using IC50 values and cell viability assays. The critical steps in this process include rigorous pharmacophore model validation, comprehensive virtual screening, careful selection of compounds for testing, and implementation of standardized experimental protocols.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on increasing automation of the workflow, improving the accuracy of binding affinity predictions through advanced machine learning algorithms, and developing more sophisticated cell-based assay systems that better recapitulate human physiology [19]. Furthermore, the adoption of novel parameters like ICr₀ and ICrmed may address some limitations of traditional IC50 measurements [15]. As these technologies mature, the bridge between in-silico predictions and in-vitro validation will become shorter and more reliable, accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic agents for various diseases.

In the field of computer-aided drug design (CADD), pharmacophore modeling stands as a pivotal technique for streamlining the drug discovery process. The concept of a pharmacophore, defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [18] [23] [24], provides an abstract framework for understanding essential ligand-target interactions. These models represent key chemical functionalities—such as hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs), hydrogen bond donors (HBDs), hydrophobic areas (H), positively/negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI), and aromatic rings (AR)—as geometric entities in three-dimensional space [18]. By focusing on interaction capabilities rather than specific chemical scaffolds, pharmacophore models enable the identification of structurally diverse compounds with potential biological activity, thereby facilitating critical tasks like virtual screening, scaffold hopping, and lead optimization [18] [23].

The generation of pharmacophore models primarily follows two distinct methodologies, each with specific data requirements and applications. Structure-based pharmacophore modeling relies on three-dimensional structural information of the target protein, often obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or computational modeling [18] [20]. In contrast, ligand-based pharmacophore modeling extracts common chemical features from a set of known active compounds without requiring direct structural knowledge of the target [18] [25]. The selection between these approaches depends largely on data availability, with structure-based methods requiring a reliable 3D protein structure and ligand-based methods necessitating a collection of active ligands with demonstrated biological activity [18].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these two fundamental approaches, focusing on their methodological frameworks, experimental validation protocols, and performance metrics within the context of pharmacophore model validation through experimental IC50 values—a crucial parameter in confirming model reliability and predictive power in drug discovery pipelines.

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Frameworks

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling derives its hypotheses directly from the three-dimensional structure of a macromolecular target, typically a protein or enzyme. This approach requires either an experimentally determined structure (from the Protein Data Bank, PDB) or a computationally generated homology model [18] [20]. The methodology begins with critical protein preparation steps, including the assessment of residue protonation states, addition of hydrogen atoms (often missing in X-ray structures), and evaluation of overall structural quality [18]. Subsequent binding site detection identifies the region where ligand binding occurs, which can be accomplished through manual analysis of co-crystallized ligands or automated tools like GRID and LUDI that sample protein regions for energetically favorable interactions [18].

The core of structure-based pharmacophore generation involves mapping potential interaction points between the protein and putative ligands. When a protein-ligand complex structure is available, pharmacophore features are derived directly from observed interactions, with exclusion volumes (XVOL) added to represent steric restrictions of the binding pocket [18] [20]. In the absence of a bound ligand, the methodology analyzes the binding site topology to identify all possible interaction points, though this typically results in less accurate models requiring manual refinement [18]. A significant advantage of this approach is its ability to differentiate between features critically involved in binding versus those that are not, leveraging direct structural insights [23].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling constructs its hypotheses from the collective analysis of known active ligands, making it particularly valuable when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unavailable [18] [25]. This approach operates on the fundamental principle that compounds sharing common biological activity against a specific target likely possess conserved chemical features with similar spatial orientations [18]. The methodology requires a carefully curated set of active ligands, preferably with demonstrated direct target interaction (e.g., through receptor binding or enzyme activity assays) and structural diversity to ensure a representative pharmacophore [23].

The technical execution involves two primary challenges: handling ligand conformational flexibility and achieving meaningful molecular alignment. For conformational sampling, two main strategies exist: the pre-enumerating method, where multiple conformations for each molecule are precomputed and stored, and the on-the-fly method, where conformational analysis occurs during the pharmacophore modeling process [25]. For molecular alignment, point-based algorithms superimpose atoms, fragments, or chemical feature points using least-squares fitting, while property-based algorithms utilize molecular field descriptors represented by Gaussian functions to generate alignments based on similarity measures [25]. The resulting model represents the common chemical features shared across the training set molecules, all presumed essential for biological activity in the absence of target structural information [23].

Comparative Analysis: Key Differences and Applications

Table 1: Fundamental comparison between structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling approaches

| Parameter | Structure-Based Approach | Ligand-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirement | 3D protein structure (experimental or modeled) [18] | Set of known active ligands [18] [25] |

| Key Advantage | Direct insight into binding interactions; ability to differentiate essential vs. non-essential features [23] | Applicable without target structural information; captures ligand flexibility [18] [25] |

| Primary Limitation | Dependent on quality and availability of protein structures [18] | Requires sufficient number of diverse active ligands; may miss key protein constraints [18] [23] |

| Feature Selection | Based on complementarity with binding site residues [18] | Based on common features across active ligand set [18] |

| Exclusion Volumes | Directly derived from binding site topography [18] [20] | Not inherently included; may be added manually if binding site is known [18] |

| Scaffold Hopping Potential | Moderate (guided by binding site constraints) [18] | High (focuses on features rather than scaffolds) [18] |

Performance Metrics and Experimental Validation

Validation represents a critical step in pharmacophore model development, assessing the model's ability to distinguish active from inactive compounds. Common validation methods include test set validation using known active and inactive compounds, decoy set validation using databases like Directory of Useful Decoys, Enhanced (DUD-E), and Fischer's method for 3D-QSAR pharmacophores [23] [12]. Key quantitative metrics include:

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Measures the enrichment of active molecules compared to random selection [23] [20]. Calculated as EF = (Hitactives / Nactives) / (Hittotal / Ntotal), where higher values indicate better performance.

- Area Under the Curve (AUC): Derived from Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) plots, with values ranging from 0-1 (where 1 indicates perfect discrimination) [20]. Models with AUC values of 0.71-0.80 are considered excellent [11].

- Goodness of Hit Score (GH): Combines recall of actives and precision in hit identification [12].

- Yield of Actives: Percentage of active compounds in the virtual hit list [23].

In prospective virtual screening applications, pharmacophore-based approaches typically achieve hit rates of 5% to 40%, significantly outperforming random selection which often yields hit rates below 1% [23]. For example, specific studies reported hit rates of 0.55% for glycogen synthase kinase-3β, 0.075% for PPARγ, and 0.021% for protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B with random screening, highlighting the substantial improvement offered by pharmacophore-based methods [23].

Table 2: Experimental validation metrics from representative pharmacophore modeling studies

| Study Target | Approach | AUC Value | Enrichment Factor | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XIAP Protein | Structure-based | 0.98 (1% threshold) | 10.0 (EF1%) | [20] |

| Brd4 Protein | Structure-based | 1.0 | 11.4-13.1 | [11] |

| Class A GPCR | Structure-based | N/A | Theoretical maximum (8/8 cases) | [26] |

| Akt2 Inhibitors | Combined (Structure & 3D-QSAR) | N/A | High enrichment reported | [12] |

Experimental Validation with IC50 Values

Validation against experimental half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values provides critical assessment of a pharmacophore model's biological relevance. In this context, known active compounds with experimentally determined IC50 values serve as essential validation benchmarks [20] [12]. The standard protocol involves:

Training Set Curation: Collecting known active compounds with IC50 values spanning multiple orders of magnitude to ensure diverse representation [12]. For instance, a study on Akt2 inhibitors utilized a training set of 23 compounds with activity spanning over 5 orders of magnitude [12].

Test Set Validation: Evaluating the model's ability to correctly identify compounds with potent IC50 values while excluding less active compounds. Successful models should retrieve compounds with lower (more potent) IC50 values early in the screening process [12].

Decoy Set Validation: Assessing model specificity by screening against databases containing known inactive compounds and decoys with similar physicochemical properties but different 2D topologies [23] [20]. The DUD-E database is commonly used for this purpose, with a recommended active-to-decoy ratio of 1:50 [23].

Prospective Experimental Validation: The ultimate validation involves testing model-selected compounds in biological assays to determine experimental IC50 values. For example, a study on XIAP antagonists identified natural compounds through pharmacophore modeling, with subsequent molecular dynamics simulations confirming stability before experimental IC50 determination [20].

Integrated Workflows and Research Applications

Combined Approaches in Modern Drug Discovery

Increasingly, integrated workflows that combine both structure-based and ligand-based approaches demonstrate enhanced performance in virtual screening campaigns. These hybrid methods leverage the complementary strengths of both methodologies, utilizing structural insights to refine ligand-based hypotheses and vice versa [12]. For example, in the discovery of Akt2 inhibitors, researchers developed both structure-based and 3D-QSAR pharmacophore models, using them collectively as 3D search queries for virtual screening [12]. This integrated approach identified seven novel hit compounds with diverse scaffolds, high predicted activity, and favorable ADMET properties [12].

The typical integrated workflow involves:

- Generating independent structure-based and ligand-based models

- Using both models as parallel filters in virtual screening

- Selecting compounds that satisfy both pharmacophore hypotheses

- Applying additional drug-like filters and ADMET analysis

- Conducting molecular docking studies to refine selections

- Experimental validation of top candidates [12]

Application Case Studies

Cancer Therapeutics: Structure-based pharmacophore modeling identified novel natural XIAP protein inhibitors for cancer treatment, with generated models demonstrating exceptional performance (AUC = 0.98) in distinguishing known active compounds from decoys [20]. Similarly, pharmacophore modeling targeting the Brd4 protein in neuroblastoma identified four natural lead compounds with promising binding characteristics and reduced potential side effects compared to chemically synthesized alternatives [11].

Enzyme Targets: In hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD) research, pharmacophore-based virtual screening successfully identified novel modulators, highlighting the method's utility for targeting enzymes associated with specific pathological conditions [23]. These approaches have proven valuable for both therapeutic development and safety assessment, identifying compounds that might disrupt steroid hormone-mediated effects [23].

GPCR Targets: For G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs)—membrane proteins of considerable therapeutic interest—structure-based pharmacophore approaches have shown remarkable performance, achieving theoretical maximum enrichment factors in both resolved structures and homology models [26]. Novel frameworks for automated pharmacophore generation and selection have been developed specifically for GPCR targets with limited known ligands [27].

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for pharmacophore modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [18] | Source of experimentally determined 3D protein structures | Structure-based pharmacophore modeling |

| Compound Databases | ZINC Database [20] [11] | Curated collection of commercially available compounds for virtual screening | Both structure-based and ligand-based approaches |

| Active Compound Repositories | ChEMBL [23], DrugBank [23], PubChem Bioassay [23] | Source of known active compounds and activity data (IC50, Ki, etc.) | Ligand-based modeling and model validation |

| Decoy Sets | DUD-E (Directory of Useful Decoys, Enhanced) [23] [20] | Provides optimized decoy compounds for model validation | Specificity assessment in both approaches |

| Software Platforms | Discovery Studio [23] [12], LigandScout [23] [20] [11] | Comprehensive tools for pharmacophore model generation and virtual screening | Both structure-based and ligand-based approaches |

| Open-Source Tools | RDKit [24] | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit with pharmacophore capabilities | Ligand-based modeling and feature analysis |

Structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling represent complementary methodologies in modern drug discovery, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and application domains. Structure-based approaches provide direct insights into ligand-target interactions but require high-quality protein structures, while ligand-based methods leverage known structure-activity relationships without requiring target structural information. Both approaches have demonstrated significant value in virtual screening campaigns, typically achieving substantially higher hit rates (5-40%) compared to random screening (<1%).

Validation against experimental IC50 values remains crucial for establishing model reliability, with metrics such as AUC, enrichment factors, and goodness-of-hit scores providing quantitative performance assessment. As drug discovery faces increasing challenges of efficiency and effectiveness, pharmacophore modeling—particularly through integrated workflows combining both structure-based and ligand-based approaches—continues to offer powerful strategies for identifying novel therapeutic candidates across diverse target classes, including kinases, GPCRs, and various enzymatic targets.

In computer-aided drug design, a pharmacophore is formally defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [18]. This conceptual framework moves beyond specific molecular structures to describe the essential functional characteristics a compound must possess to interact effectively with its biological target. The most significant pharmacophoric features include hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs), hydrogen bond donors (HBDs), hydrophobic areas (H), positively and negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI), and aromatic groups (AR) [18]. These features are represented as geometric entities—spheres, planes, and vectors—that define the spatial and electronic requirements for bioactivity, enabling researchers to identify structurally diverse compounds that share the same fundamental interaction capabilities [18].

The validation of pharmacophore models through experimental bioactivity data, particularly half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values, forms a critical bridge between computational prediction and experimental confirmation. This review comprehensively compares the performance of structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling approaches, their respective experimental validation methodologies, and their successful application in identifying bioactive compounds across multiple drug target classes.

Comparative Analysis of Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

Fundamental Methodologies and Characteristic Features

Pharmacophore modeling strategies are primarily categorized into structure-based and ligand-based approaches, each with distinct methodologies, output characteristics, and validation requirements.

Table 1: Comparison of Structure-Based and Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

| Aspect | Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling | Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Source | 3D structure of target protein (often from PDB), with or without bound ligand [18] | Set of known active ligands and their experimental activity data (e.g., IC50) [18] [28] |

| Key Features Identified | Direct interaction points from protein-ligand complex (HBA, HBD, H, PI/NI, AR) plus exclusion volumes [18] [29] | Common chemical functionalities across active ligands (HBA, HBD, HY-AL, HY-AR, RA) [28] |

| Experimental Validation | Directly derived from experimental structure (X-ray, NMR); validated via docking scores and MD simulation stability [30] [20] | Dependent on experimental IC50 values of training/test sets; validated via ROC curves, enrichment factors, and QSAR correlation [20] [28] |

| IC50 Correlation | Indirect; used to identify novel compounds subsequently tested for IC50 [20] | Direct; model generation often uses IC50 values, and predictive models estimate IC50 of new compounds [28] |

| Representative Software | LigandScout, Schroedinger's E-Pharmacophores, FLAP, SILCS-Pharm [30] [31] | Discovery Studio HypoGen, RDKit, LigandScout [24] [28] |

Performance Metrics in Virtual Screening

The ultimate validation of any pharmacophore model lies in its ability to identify novel active compounds through virtual screening. Both structure-based and ligand-based approaches have demonstrated excellent performance across multiple targets, though their effectiveness depends on data quality and implementation.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of Pharmacophore Models in Virtual Screening

| Target Protein | Modeling Approach | Validation Metric | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XIAP | Structure-Based (LigandScout) | AUC (ROC Curve), EF1% | AUC = 0.98; Enrichment Factor = 10.0 at 1% threshold | [20] |

| Human Renin | Ligand-Based 3D QSAR (HypoGen) | Correlation Coefficient | r = 0.944 (high correlation between estimated and experimental activity) | [28] |

| Multiple Targets (8 systems) | SILCS-Pharm (Extended) | Screening Enrichment | Superior or comparable to DOCK, AutoDock, and AutoDock Vina | [31] |

| ERα | Structure-Based (LigandScout) + Docking | Binding Affinity (kcal/mol) | Best derivative: -12.33 kcal/mol (compared to -12.25 for 4-OHT) | [29] |

Diagram 1: Workflow comparison of structure-based versus ligand-based pharmacophore modeling approaches, showing divergent data sources but convergent validation pathways.

Experimental Validation Protocols and IC50 Correlation

Structure-Based Model Validation: The XIAP Case Study

The validation of structure-based pharmacophore models typically employs a multi-stage protocol combining computational and experimental techniques. A representative study targeting the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) demonstrates this comprehensive approach [20]:

Model Generation: A structure-based pharmacophore model was built from the XIAP complex with Hydroxythio Acetildenafil (PDB: 5OQW) using LigandScout, identifying 14 chemical features including 4 hydrophobic features, 1 positive ionizable, 3 H-bond acceptors, and 5 H-bond donors [20].

Initial Validation: The model was validated using a decoy set containing 10 known active XIAP antagonists and 5199 decoy compounds from the DUD database. The model achieved an Area Under the Curve (AUC) value of 0.98 and an early enrichment factor (EF1%) of 10.0, demonstrating excellent ability to distinguish true actives from decoys [20].

Virtual Screening & Experimental Confirmation: The validated model screened the ZINC natural compound database, identifying 7 initial hits. Molecular docking refined these to 4 candidates, which subsequently underwent molecular dynamics simulations. Three compounds—Caucasicoside A, Polygalaxanthone III, and MCULE-9896837409—demonstrated stable binding and were proposed as potential lead compounds for XIAP-related cancer therapy [20].

Ligand-Based QSAR Pharmacophore Validation: Human Renin Inhibitors

Ligand-based quantitative pharmacophore modeling utilizes experimental IC50 values to build predictive models, as demonstrated in the discovery of human renin inhibitors [28]:

Training Set Design: A diverse set of 18 compounds with IC50 values ranging from 0.5 nM to 5590 nM was selected to ensure a substantial spread of activity values for meaningful model generation [28].

Model Generation & Statistical Validation: The best quantitative pharmacophore hypothesis contained one hydrophobic feature, one hydrogen bond donor, and two hydrogen bond acceptors, with a high correlation value of 0.944 between estimated and experimental activities. The model was further validated using Fischer randomization and leave-one-out methods to ensure statistical significance [28].

Test Set Validation: The model successfully predicted activities of an external test set containing 93 compounds, confirming its predictive capability beyond the training set. This validation against experimentally determined IC50 values provides confidence in the model's ability to prioritize compounds for synthesis and testing [28].

Addressing Dynamic Stability Through Molecular Dynamics

A significant challenge in structure-based pharmacophore modeling is the reliance on single static structures from crystallography, which may not represent the dynamic nature of protein-ligand interactions in solution. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide a solution to this limitation by incorporating protein flexibility [30]:

Dynamic Feature Analysis: In a study of 12 protein-ligand complexes, MD simulations revealed that pharmacophore features observed in crystal structures displayed varying stability during simulation. Some features present in crystal structures appeared only rarely (<5% of simulation time), suggesting possible crystallographic artifacts, while other features not visible in crystal structures demonstrated high persistence (>90% of simulation time) [30].

Consensus Pharmacophore Generation: A "merged pharmacophore model" approach incorporates features observed either in the experimental structure or any MD simulation snapshot, creating a consensus model that represents the dynamic interaction profile. This method allows researchers to prioritize frequently occurring features and potentially discard rare features that may represent structural artifacts [30].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pharmacophore Development and Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository of experimentally determined 3D protein structures | Primary data source for structure-based pharmacophore modeling [18] |

| Compound Databases | ZINC Database | Curated collection of commercially available compounds for virtual screening | Source of screening compounds for pharmacophore-based VS [20] |

| Validation Datasets | DUD (Directory of Useful Decoys) | Annotated sets of active compounds and property-matched decoys | Validation of pharmacophore model selectivity and enrichment capability [20] [31] |

| Structure-Based Modeling Software | LigandScout | Generation of structure-based pharmacophores from protein-ligand complexes | Identification of key interaction features and exclusion volumes [30] [20] |

| Ligand-Based Modeling Software | Discovery Studio HypoGen | Development of 3D QSAR pharmacophore models | Creation of quantitative models correlating features with IC50 values [28] |

| Dynamics Integration Tools | GROMACS, AMBER | Molecular dynamics simulation packages | Assessment of pharmacophore feature stability under dynamic conditions [30] |

| Virtual Screening Platforms | SILCS-Pharm | Pharmacophore modeling incorporating protein flexibility and desolvation | Enhanced screening considering competitive solvation effects [31] |

Diagram 2: Iterative validation cycle for pharmacophore models, demonstrating the essential role of experimental IC50 values in model refinement and confirmation.

The validation of pharmacophore models through experimental IC50 values represents a critical methodology in modern drug discovery. Both structure-based and ligand-based approaches demonstrate distinct strengths: structure-based models directly leverage structural biology data to identify key interaction features, while ligand-based models efficiently utilize existing structure-activity relationship data to build predictive models. The integration of molecular dynamics simulations addresses inherent limitations of static crystal structures, providing dynamic consensus models that more accurately represent the true interaction landscape.

Successful applications across diverse target classes—including XIAP, human renin, and estrogen receptor alpha—demonstrate that pharmacophore models achieving high statistical validation metrics (AUC >0.9, enrichment factors >10, correlation coefficients >0.94) consistently identify compounds with promising experimental activity. The continued refinement of these methodologies, particularly through the incorporation of protein flexibility and more sophisticated treatment of solvation and entropic effects, promises to further enhance the predictive power of pharmacophore modeling in rational drug design.

A Step-by-Step Protocol for Pharmacophore Model Validation Using IC50

The validation of a pharmacophore model is a critical step in computer-aided drug design, determining its reliability for virtual screening campaigns. A cornerstone of this process is the construction of a rigorous validation dataset, comprising known active compounds and carefully selected inactive decoys. When this dataset is used to generate metrics like the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve and the Enrichment Factor (EF), it provides a quantitative measure of a model's ability to discriminate between ligands that bind to the target and those that do not. Framed within the broader thesis of validating pharmacophore models through experimental IC50 research, this guide objectively compares the performance of different validation approaches and details the experimental protocols that underpin robust model development.

The Critical Role of Active Compounds and Decoys

A well-constructed validation dataset tests the pharmacophore model's ability to identify true binders while rejecting non-binders. This requires two key components:

- Active Compounds: A set of known active compounds, typically antagonists or inhibitors of the target protein, for which experimental activity data (e.g., IC50 values) is available. These actives serve as positive controls.

- Decoy Sets: A collection of molecules that are presumed to be inactive against the target. The quality of these decoys is paramount; they should be chemically similar to the actives (making them challenging to distinguish) but physiologically inactive, testing the model's specificity.

The performance of a pharmacophore model is often validated using the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the ROC curve and the Enrichment Factor (EF). A model with an AUC of 1.0 and a high EF value demonstrates excellent discriminatory power, successfully retrieving actives while filtering out decoys [11].

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics from Published Validations

| Study Target | Number of Active Compounds | Decoy Source | AUC | Enrichment Factor (EF1%) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XIAP Protein | 10 | DUD-E | 0.98 | 10.0 | [20] |

| Brd4 Protein | 36 | DUD-E | 1.0 | 11.4 - 13.1 | [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Dataset Curation and Validation

Protocol 1: Sourcing and Preparing Active Compounds

The first step involves gathering a robust set of confirmed active compounds.

- Literature and Database Mining: Identify active antagonists or inhibitors from scientific literature and public bioactivity databases such as ChEMBL or BindingDB [11] [20]. The activity of these compounds should be confirmed by experimental IC50 values.

- Curation and Standardization:

- Filter the compounds to ensure data originates from original research publications, not reviews [32].

- Remove entries with unclear measurements (e.g., values qualified with ">" or "<", or with incorrect units) [32].

- Resolve duplicates by keeping the original publication's data to avoid redundancy [32].

- Convert all activity values (e.g., IC50, Ki) to a consistent unit, typically the negative logarithm (e.g., pIC50) for analysis [32].

Protocol 2: Generating a Matched Decoy Set

The DUD-E (Database of Useful Decoys: Enhanced) server is a widely used resource for generating property-matched decoys [11] [20].

- Input: Submit your curated set of active compounds to the DUD-E server.

- Process: DUD-E automatically generates decoy molecules that are physically similar but chemically different from the actives. It matches decoys to actives based on molecular weight, calculated logP, and number of hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, but ensures they have different 2D topological structures [20].

- Output: The result is a challenging set of decoys that tests the model's ability to recognize specific pharmacophoric features beyond simple physicochemical properties.

Protocol 3: Model Validation and Performance Calculation

With the active and decoy set prepared, the pharmacophore model's performance can be quantitatively assessed.

- Virtual Screening: Screen the combined set of actives and decoys against your pharmacophore model.

- ROC Curve Generation:

- Enrichment Calculation:

- Calculate the Enrichment Factor (EF), which measures how much more likely you are to find an active compound early in a ranked list compared to a random selection. The formula for EF at a given percentage (e.g., 1%) of the screened database is:

EF = (Number of actives found in top X% / Total number of actives) / X%[11].

- Calculate the Enrichment Factor (EF), which measures how much more likely you are to find an active compound early in a ranked list compared to a random selection. The formula for EF at a given percentage (e.g., 1%) of the screened database is:

- Statistical Validation: Use the collected metrics (AUC, EF) to validate the model. For example, an AUC of 0.98 and an EF of 10.0, as achieved in a XIAP protein study, indicate a high-quality, predictive pharmacophore model [20].

Dataset Validation Workflow

The choice of experimental data for validating actives and benchmarking model performance is crucial. IC50 values are a common metric, but their use requires careful consideration.

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Data for Validation

| Data Type | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Limitations / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public IC50 Data | Assay-specific measurement of half-maximal inhibitory concentration. The most common public bioactivity metric [32]. | High data availability; Essential for building large-scale models [32]. | Variability between labs and assay conditions can introduce noise; Assay details are often not reported in databases, complicating comparison [32]. |

| In-house IC50 Data | IC50 values generated internally using standardized, controlled assay protocols. | High internal consistency; Known and controlled assay conditions. | Costly and time-consuming to produce; Not available for all targets in public domain. |

| Ki Data | Direct measurement of binding affinity, independent of assay conditions. | Can be converted to IC50 using the Cheng-Prusoff equation for competitive inhibition [32]. | Less frequently found in public databases compared to IC50 [32]. |

Statistical analysis suggests that while mixing public IC50 data from different sources adds a moderate amount of noise, it can still be viable for large-scale model validation, especially when data is scarce. Augmenting IC50 data with corrected Ki data (using a conversion factor, often ~2) can also be a reasonable strategy without significantly deteriorating data quality [32].

Table 3: Key Reagents and Resources for Validation

| Item | Function in Validation | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | A primary source for curated bioactivity data, including IC50 values for known active compounds against thousands of targets [32]. | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/ |

| DUD-E Server | Generates property-matched decoy sets for a given list of active compounds, enabling rigorous model validation [11] [20]. | http://dude.docking.org/ |

| ZINC Database | A freely accessible database of commercially available compounds, often used for virtual screening and as a source of decoy molecules [11] [20]. | http://zinc.docking.org |

| IC50 Calculator | Tools that use regression models (e.g., four-parameter logistic curve) to calculate IC50 values from raw experimental data [33]. | AAT Bioquest IC50 Calculator |

| LigandScout Software | Advanced molecular design software used for creating structure-based pharmacophore models and performing virtual screening [11] [20]. | Intel:Ligand |

Pillars of Model Validation

The integrity of a pharmacophore model is only as strong as the validation dataset used to test it. A meticulous approach—curating active compounds with reliable experimental IC50 values, leveraging rigorously matched decoy sets from resources like DUD-E, and employing standardized protocols for performance calculation—is fundamental for establishing model credibility. Quantitative metrics like AUC and EF, derived from this process, provide an objective standard for comparing model performance. As the field advances, the careful preparation of validation datasets remains a non-negotiable practice, ensuring that virtual screening efforts are built on a foundation of statistical rigor and scientific reproducibility.

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening (VS) represents a cornerstone of modern computer-aided drug discovery, enabling researchers to efficiently identify novel bioactive compounds from extensive chemical libraries [18] [23]. This methodology abstracts the essential steric and electronic features necessary for optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target, providing a powerful template for database searching [18]. The ultimate validation of any pharmacophore model lies in its successful application to discover compounds with experimentally confirmed biological activity, typically measured through IC₅₀ values [5] [20]. This guide provides a comprehensive overview of the screening process, from initial model preparation to experimental validation, equipping researchers with practical methodologies for predicting bioactivity.

Core Methodology: The Virtual Screening Workflow

The process of running a virtual screening campaign using a pharmacophore model follows a systematic workflow designed to maximize the identification of true active compounds while efficiently managing computational resources.

Pre-screening Preparation

Model Refinement and Validation Before initiating database screening, ensure your pharmacophore hypothesis has undergone rigorous validation [23]. This includes assessing its ability to distinguish known active compounds from inactive molecules or decoys using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and enrichment factors [20] [34]. A well-validated model should achieve an AUC (Area Under the Curve) value significantly higher than 0.5, with exemplary models often exceeding 0.88 [34]. Additionally, incorporate exclusion volumes to represent the steric boundaries of the binding pocket and prevent clashes with the protein surface [18] [23].

Database Curation and Preparation Virtual screening requires careful preparation of the compound database to be screened. Common sources include the ZINC database (containing over 230 million commercially available compounds), ChEMBL, DrugBank, and specialized in-house collections [20] [23]. Pre-process compounds by: