Validating Computational Models for Cancer Target Identification: From AI Algorithms to Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the methodologies, applications, and validation frameworks for computational models in cancer target identification.

Validating Computational Models for Cancer Target Identification: From AI Algorithms to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the methodologies, applications, and validation frameworks for computational models in cancer target identification. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of AI and machine learning in oncology, details cutting-edge tools and their practical applications, addresses key challenges and optimization strategies, and establishes rigorous standards for model validation and benchmarking. By synthesizing recent advances and real-world case studies, this resource aims to bridge the gap between computational prediction and robust biological validation, ultimately accelerating the development of novel cancer therapeutics.

The New Frontier: How AI and Computational Biology are Revolutionizing Cancer Target Discovery

The Critical Need for Novel Target Identification in Oncology

The identification of novel therapeutic targets is a cornerstone of advancing oncology care. However, current targeted therapies face significant drawbacks, including a limited number of druggable targets, ineffective population coverage, and inadequate responses to drug resistance [1]. Approximately 90% of clinical drug development fails, with nearly half of these failures attributed to a lack of clinical efficacy, highlighting fundamental issues in target validation and selection [2]. Cancer progression is an evolutionary process where tumor cells behave as complex, self-organizing systems that adapt to microenvironmental proliferation barriers [3]. This complexity arises from intricate interactions between genes and their products, which traditional hypothesis-driven experimental approaches often fail to capture comprehensively [1].

Computational biology has emerged as a transformative approach to address these challenges. By employing artificial intelligence (AI) and mathematical modeling, researchers can now process biological network data to preserve and quantify interactions between cellular system components [1]. These computational models serve as virtual laboratories, allowing for hypothesis testing and therapeutic exploration without the constraints of traditional experimentation [3]. The integration of multi-omics technologies—including epigenetics, genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—provides the essential data foundation for these computational approaches [1]. When effectively validated and implemented, computational models offer unprecedented insights into carcinogenesis and present powerful tools for identifying novel anticancer targets with improved therapeutic potential.

Computational Approaches for Target Identification

Network-Based Biology Analysis

Network-based algorithms analyze biological systems as interconnected networks where nodes represent biological entities (genes, proteins, mRNAs, metabolites) and edges represent associations or interactions between them (gene co-expression, signaling transduction, physical interactions) [1]. This approach provides a quantitative framework to study the relationship between network characteristics and cancer pathogenesis [1].

Key Methodologies and Applications:

- Shortest Path Analysis: Identifies the most direct connections between biological components, potentially revealing critical pathways in disease progression [1].

- Module Detection: Discovers densely connected subnetworks (modules) that often correspond to functional units or disease-related pathways [1].

- Network Centrality: Measures node importance based on its position within the network, helping identify hub genes/proteins critical for network stability and function [1].

- Network Controllability Analysis: Applies control theory principles to identify "indispensable" proteins that affect network controllability. Analysis of 1,547 cancer patients revealed 56 indispensable genes across nine cancers, 46 of which were newly associated with cancer, demonstrating this method's potential for novel disease gene discovery [1].

Machine Learning-Based Biology Analysis

Machine learning (ML) approaches efficiently handle high-throughput, heterogeneous molecular data to mine features and relationships within biological networks [1]. These methods are particularly valuable for pattern recognition in complex datasets and predictive modeling of drug responses.

Applications in Oncology Target Identification:

- Multi-Omics Integration: ML algorithms integrate genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and clinical data to identify molecular drivers of cancer growth and potential therapeutic targets [4].

- Patient Stratification: By combining genomic information with clinical data, ML models identify patient subgroups more likely to respond to specific therapies, enabling precision oncology approaches [4].

- Drug Response Prediction: ML models trained on historical patient data, including genetic information and drug response patterns, can forecast individual patient responses to treatments [4].

- Resistance Mechanism Analysis: ML tools track mutations in real-time by analyzing genomic data from tumor biopsies taken before and after treatment, identifying alterations that drive therapeutic resistance [4].

Structure-Based Computational Approaches

Structure-based methods leverage computational techniques to identify potential drug targets based on molecular structure information.

Inverse Virtual Screening (IVS) has emerged as a promising structure-based approach that decipher protein targets of bioactive compounds. This method can rationalize observed side effects and open new therapeutic strategies by identifying previously unknown target interactions [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Validating Computational Predictions

Common Validation Challenges and Solutions

| Challenge | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate Target Predictions | Noisy or incomplete biological data [6]; Model oversimplification [7] | Implement rigorous data cleaning and validation protocols [6]; Use ensemble modeling approaches that combine multiple algorithms [1] |

| Poor Translational Performance | Discrepancy between in silico models and human biology [2]; Omitting critical biological mechanisms [7] | Incorporate human-derived data (organoids, PDX models) [4]; Enhance models with tumor microenvironment components [7] |

| Inability to Recapitulate Disease Complexity | Lack of multi-scale dynamics [7]; Failure to capture emergent behaviors [7] | Develop multiscale models integrating molecular, cellular, and tissue levels [7]; Implement agent-based models to capture spatial heterogeneity [7] |

| Overhyped AI Expectations | Excessive promise without realistic assessment of limitations [8] | Maintain culture of realism about AI capabilities [8]; Set appropriate expectations about development timelines [8] |

| Resistance Mechanism Oversight | Failure to account for tumor evolutionary dynamics [3] | Incorporate evolutionary principles into models [3]; Analyze pre- and post-treatment biopsies to identify resistance patterns [4] |

Experimental Validation Workflow

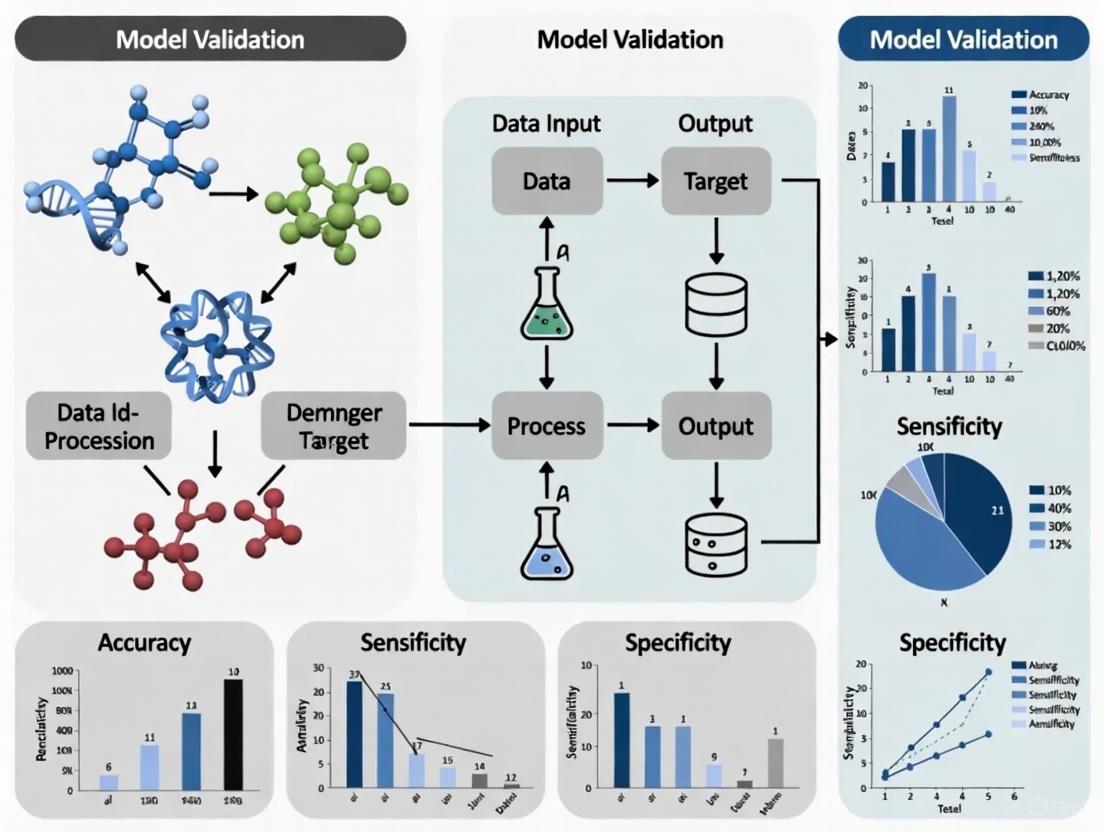

The following diagram illustrates a robust workflow for transitioning from computational predictions to experimentally validated targets:

Data Quality Assessment Protocol

Objective: Ensure biological data quality before computational analysis.

Procedure:

- Data Auditing: Perform comprehensive assessment of data sources for completeness, consistency, and potential biases [6].

- Noise Reduction: Apply appropriate filtering algorithms to remove technical artifacts while preserving biological signals [6].

- Batch Effect Correction: Implement statistical methods to minimize non-biological variations introduced by different experimental batches [6].

- Cross-Validation: Split datasets into training, validation, and test sets to evaluate model performance and prevent overfitting [4].

- Benchmarking: Compare computational predictions against known gold-standard targets to assess predictive accuracy [5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does approximately 90% of clinical drug development fail in oncology, and how can better target identification address this?

A1: Clinical drug development fails due to lack of efficacy (40-50%), unmanageable toxicity (30%), poor drug-like properties (10-15%), and insufficient commercial planning (10%) [2]. Improved target identification addresses these failures by: 1) Enhancing efficacy through better validation of target-disease relationships; 2) Reducing toxicity by identifying targets with better therapeutic windows; 3) Incorporating drug-like property considerations early in target selection; and 4) Ensuring targets have clear clinical and commercial pathways [2] [4].

Q2: What are the most significant limitations of current computational models in cancer target identification?

A2: Key limitations include: 1) Data challenges - handling gigantic datasets, ensuring data accuracy, and integrating different data types [6]; 2) Model complexity - balancing biological realism with computational feasibility [7]; 3) Validation barriers - scarcity of high-quality longitudinal datasets for parameter calibration [7]; 4) Technical expertise - shortage of professionals skilled in both biology and computation [6]; and 5) Standardization issues - lack of uniform databases, software tools, and coding practices across research groups [6].

Q3: How can researchers effectively bridge the gap between computational predictions and experimental validation?

A3: Successful integration requires: 1) Iterative refinement - using experimental results to improve computational models in a continuous cycle [9]; 2) Advanced model systems - employing patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) and organoids that better recapitulate human tumors [4]; 3) Multi-disciplinary collaboration - fostering teamwork between computational biologists, experimentalists, and clinicians [7]; and 4) AI-mediated integration - using artificial intelligence to prioritize the most promising predictions for experimental testing [9].

Q4: What role does the tumor microenvironment (TME) play in computational modeling for target identification?

A4: The TME is critical because: 1) Therapeutic resistance - TME interactions can promote drug resistance independent of cancer cell mutations [7]; 2) Spatial heterogeneity - nutrient and oxygen gradients create distinct cellular subpopulations with different target expression [3]; 3) Immune modulation - immune cell interactions influence tumor progression and treatment response [7]; and 4) Emergent behaviors - cell-cell interactions within the TME can produce unexpected phenomena not predictable from isolated cell studies [7]. Agent-based models (ABMs) are particularly useful for capturing these spatial and dynamic TME interactions [7].

Q5: How can the "overhyping" of AI in drug discovery negatively impact the field?

A5: Overhyping AI creates several problems: 1) Unrealistic expectations - promising rapid breakthroughs that don't materialize, leading to disillusionment [8]; 2) Resource misallocation - investments based on fear of missing out rather than scientific merit [8]; 3) Reduced creativity - overly conservative AI applications that stick too closely to known chemical space [8]; and 4) Long-term setbacks - if AI doesn't deliver promised results, it could "put the field back quite a long way when people stop thinking it can work" [8].

Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Validation

The following table details essential materials and their applications in validating computationally predicted targets:

| Research Reagent | Function in Target Validation | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDXs) | Maintain tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment of original tumors [4] | Preclinical efficacy testing; Biomarker discovery; Drug response prediction [4] |

| Organoids & 3D Culture Systems | Provide physiologically relevant models that recapitulate human tumors [4] | High-throughput drug screening; Personalized therapy testing; Tumor biology studies [4] |

| Fluorescent Ubiquitination-Based Cell Cycle Indicator (FUCCI) | Visualize cell cycle progression in live cells [3] | Study cell cycle dynamics; Drug mechanism studies; Cell division imaging [3] |

| Multi-Omics Datasets | Provide comprehensive molecular profiling of tumors [1] | Target identification; Biomarker discovery; Patient stratification [1] [4] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Enable precise genome editing for functional validation [4] | Gene knockout studies; Functional genomics; Target validation [4] |

Quantitative Data Framework for Target Assessment

Key Parameters for Evaluating Potential Targets

| Assessment Category | Specific Metrics | Optimal Range/Values |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic Evidence | Mutation frequency in cancer cohorts; Germline association with cancer risk; Somatic signature | Recurrent mutations across independent cohorts; Significant GWAS associations [1] |

| Functional Impact | Network centrality scores; Essentiality scores (CRISPR screens); Pathway enrichment | High betweenness centrality; Essential in multiple cancer cell lines [1] |

| Druggability | Binding pocket characteristics; Similarity to known drug targets; Chemical tractability | Defined hydrophobic pockets; Similar to successful targets [2] |

| Therapeutic Window | Tissue expression specificity; Essentiality in normal cells; Phenotype of inhibition | High disease-tissue/normal-tissue ratio; Non-essential in vital tissues [2] |

| Clinical Correlation | Expression association with prognosis; Predictive biomarker potential; Resistance association | Significant survival correlation; Predictive of drug response [4] |

STAR Framework for Drug Candidate Classification

The Structure-Tissue Exposure/Selectivity-Activity Relationship (STAR) provides a systematic approach to classify drug candidates based on critical properties [2]:

The critical need for novel target identification in oncology demands a sophisticated approach that leverages computational power while maintaining rigorous experimental validation. Successful target discovery requires seamlessly integrating network biology, machine learning, and structural computational methods with physiologically relevant model systems and comprehensive data integration. The framework presented here—encompassing troubleshooting guidance, standardized protocols, and systematic assessment criteria—provides a pathway for researchers to navigate the complexities of cancer target validation.

Future advances will depend on overcoming key challenges in data quality, model refinement, and interdisciplinary collaboration. The emergence of AI for Science (AI4S) represents a transformative paradigm that integrates data-driven modeling with prior knowledge, enabling more autonomous and intelligent experimentation [10]. As these technologies evolve, the development of patient-specific 'digital twins'—virtual replicas that simulate disease progression and treatment response—may further accelerate target validation and therapeutic optimization [7]. By adopting these integrated approaches and maintaining realistic expectations about technological capabilities, the research community can significantly improve the efficiency and success of oncology drug development.

The validation of computational models is a critical step in cancer target identification research. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers address specific issues encountered during experiments that utilize core AI technologies: Machine Learning (ML), Deep Learning (DL), and Natural Language Processing (NLP). The following sections are structured to directly support scientists in developing robust, reproducible, and clinically relevant computational findings.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary applications of ML, DL, and NLP in cancer target identification?

- Machine Learning (ML) is often used with structured data. Applications include survival prediction, therapy response forecasting, and identifying molecular subtypes from genomic biomarkers and lab values [11]. For example, ensemble methods can analyze genomic data from sources like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) to uncover novel therapeutic vulnerabilities [12].

- Deep Learning (DL), particularly architectures like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), excels with image-based data. It is used for tumor detection, segmentation, and grading from histopathology slides and radiology scans [11] [13]. Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and transformers are applied to sequential data like genomic sequences for biomarker discovery [11].

- Natural Language Processing (NLP) is key for knowledge extraction from unstructured text. It mines biomedical literature, clinical notes, and medical guidelines to identify relationships between entities, accelerating hypothesis generation [14] [15]. Large Language Models (LLMs) can preprocess clinical notes to improve the extraction of biomedical concepts, which is vital for curating datasets for other models [15].

FAQ 2: My DL model for histopathology image analysis is overfitting. What are the first steps to troubleshoot this?

Overfitting is a common challenge. Begin with the following steps:

- Data Augmentation: Artificially expand your training dataset using techniques like rotation, flipping, and color jittering on your digitized tissue slides.

- Regularization Techniques: Implement methods such as Dropout or L2 regularization within your network architecture to prevent complex co-adaptations to the training data.

- Review Dataset Size and Splitting: Ensure your dataset is large enough and that there is no data leakage between your training and validation sets. A model trained on a small dataset is prone to overfitting [12].

- Simplify the Model: Reduce the complexity of your network (e.g., number of layers or parameters) if your dataset is limited.

FAQ 3: How can I use NLP to generate a testable biological hypothesis for a new cancer target?

A validated approach involves using a foundation model to perform a virtual screen. A recent study provides a protocol:

- Task Formulation: Define a specific biological question. For example, "Find a drug that acts as a conditional amplifier of antigen presentation only in a specific immune-context-positive environment" [16].

- Dual-Context Virtual Screen: Simulate the effect of thousands of drugs across two computational contexts: a disease-relevant environment (e.g., patient samples with tumor-immune interactions) and a neutral control environment (e.g., isolated cell lines) [16].

- Prediction and Filtering: The model predicts candidate drugs that show the desired effect only in the disease-relevant context. This "context split" highlights the most promising and novel hypotheses [16].

- Experimental Validation: The top predictions, such as a specific kinase inhibitor, must be confirmed through in vitro lab experiments to verify the predicted biological effect [16].

FAQ 4: What are the key considerations for preparing multi-omics data for ML models?

- Data Modality Matching: Ensure your data modalities (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, clinical records) are correctly aligned per patient sample.

- Structured Data Conversion: Convert genomic sequences and other complex data into structured formats that ML models can process [11].

- Handling Missing Data: Develop a robust strategy for dealing with missing values, such as imputation or removal, to prevent bias in your model's predictions [12].

- Feature Extraction: Use techniques like radiomics to extract quantitative features from standard medical scans, which can then be used as input for ML models to predict therapy response [13].

FAQ 5: My model's predictions lack interpretability, creating a barrier for clinical adoption. What can I do?

The "black box" nature of some complex AI models is a significant hurdle.

- Leverage Interpretability Tools: For DL models on images, use saliency maps that highlight which regions of a medical image (e.g., a mammogram or pathology slide) most influenced the prediction [11] [17].

- Incorporate Explainable AI (XAI) Methods: Integrate techniques like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) to explain the output of any model [12].

- Use Transparent Models Where Possible: For critical decisions where interpretability is paramount, consider using more interpretable classical ML models (e.g., logistic regression, decision trees) if they provide sufficient performance [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Generalization of a Prognostic Model to External Patient Cohorts

Problem: A prognostic model developed using an ML-driven approach performs well on internal validation but fails on an external cohort from a different clinical site [18].

Solution:

- Check 1: Data Heterogeneity. Investigate differences in data acquisition protocols, patient demographics, and cancer subtypes between the internal and external cohorts. These variations are a common source of performance drop.

- Check 2: Preprocessing Pipeline. Ensure the exact same preprocessing steps (e.g., normalization, gene scaling) used on the training data are applied to the external cohort data. Inconsistency here is a frequent error.

- Action 1: Algorithmic Adjustment. Employ training techniques that explicitly improve generalization, such as domain adaptation or federated learning, which can help models perform better across diverse datasets without sharing raw data [12].

- Action 2: Recalibration. Recalibrate the model's output on a small, representative sample from the external cohort before full deployment.

Issue 2: Failure in Experimental Validation of an AI-Predicted Drug Target

Problem: A small molecule or target identified through a virtual AI screen fails to show efficacy in wet-lab experiments [12] [19].

Solution:

- Check 1: Training Data Fidelity. Scrutinize the quality and biological relevance of the data used to train the AI model. Was it trained on data that accurately represents the disease context? Biased or noisy data leads to flawed predictions [12].

- Check 2: Contextual Mismatch. A leading cause of failure is a mismatch between the in silico context of the model and the in vitro/in vivo experimental conditions. Revisit the biological assumptions built into the AI screen [16].

- Action 1: Focus on Novel, Validated Hits. Prioritize candidates where the AI model has made a novel prediction that was subsequently confirmed in the lab, as this demonstrates true discovery power. For example, the Gemma model identified the CK2 inhibitor silmitasertib as a conditional amplifier of antigen presentation, which was then confirmed in human cell models [16].

- Action 2: Iterative Refinement. Use the experimental results to refine the AI model. Failed predictions are valuable data points that can be used to retrain and improve the next iteration of the model.

Issue 3: Inefficient Mining of Biomedical Literature for Target Discovery

Problem: An NLP pipeline is failing to efficiently extract meaningful relationships between genes, diseases, and drugs from large volumes of scientific literature [15].

Solution:

- Check 1: NLP Task Pipeline. Ensure your pipeline correctly sequences core NLP tasks: Tokenization, Named Entity Recognition (NER) to identify key concepts (e.g., gene names, diseases), and Relation Extraction to understand how these entities are connected in the text [20].

- Check 2: Domain-Specific Tuning. General-purpose NLP models may perform poorly on biomedical text full of specialized jargon. Use or fine-tune models that have been pre-trained on biomedical corpora (e.g., BioBERT, models from resources like LitCOVID) [14] [15].

- Action 1: LLM Preprocessing. Use Large Language Models (LLMs) to preprocess raw text from clinical notes or literature. They can correct spelling, expand acronyms, and standardize terminology, which significantly improves the performance of downstream relation extraction tools [15].

- Action 2: Hybrid Approach. Combine rule-based systems (for well-established relationships) with statistical or deep learning models (for discovering novel associations) to balance precision and recall [20].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Metrics of AI Models in Cancer Detection

This table summarizes the quantitative performance of select AI systems as reported in recent studies, providing a benchmark for model validation [11].

| Cancer Type | Modality | AI System | Key Metric | Performance | Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer | Colonoscopy | CRCNet | Sensitivity | 91.3% vs. Human 83.8% (p<0.001) | Retrospective multicohort [11] |

| Breast Cancer | 2D Mammography | Ensemble of 3 DL models | Specificity | +5.7% vs. Radiologists (p<0.001) | Diagnostic case-control [11] |

| Breast Cancer | 2D/3D Mammography | Progressively trained RetinaNet | AUC | 0.94 (Reader Study) | Diagnostic case-control [11] |

| Colorectal Polyps | Histopathology | Real-time image recognition | Accuracy (Neoplastic) | 95.9% Sensitivity, 93.3% Specificity | Prospective diagnostic [11] |

Table 2: Computational Requirements and Output of AI Techniques

This table helps researchers select the appropriate AI technology based on their computational resources and project goals [11] [12] [19].

| AI Technology | Typical Input Data | Example Tasks in Oncology | Key Algorithms/Models | Computational Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Machine Learning (ML) | Structured data (genomic biomarkers, lab values) [11] | Survival prediction, therapy response, molecular subtyping [11] [18] | Logistic Regression, Random Forests, SVMs [19] | Low to Medium |

| Deep Learning (DL) | Imaging (histopathology, radiology), genomic sequences [11] | Tumor detection & segmentation, de novo drug design [11] [19] | CNNs, RNNs, GANs, VAEs [11] [19] | High (requires specialized hardware) |

| Natural Language Processing (NLP) | Unstructured text (literature, clinical notes) [15] | Named Entity Recognition, Relation Extraction, Literature-based discovery [14] [15] | Transformers, LLMs (e.g., GPT, BioBERT) [15] [20] | Medium to Very High (for large models) |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: ML-Driven Workflow for Tumor Prognosis and Target Discovery

This protocol details a machine learning-driven approach for prognostic model development, molecular stratification, and drug target discovery, as adapted from a recent standardized research protocol [18].

Summary: The procedure involves using transcriptome data to develop a robust prognostic signature, identify molecular subtypes, and prioritize druggable transcription factors through drug sensitivity analysis.

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- Data Preprocessing and Feature Selection: Process RNA-seq data (e.g., from TCGA). Normalize read counts and filter for genes with significant variance. Perform robust gene signature prioritization using co-expression network analysis or similar methods [18].

- Prognostic Model Development: Divide the cohort into training and test sets. Using the training set, train a survival prediction model (e.g., Cox Proportional Hazards model with LASSO regularization) based on the prioritized gene signature. Validate the model's performance on the held-out test set using concordance index (C-index) [18].

- Molecular Subtyping: On the entire dataset, perform unsupervised clustering (e.g., k-means, consensus clustering) on the expression data of the key signature genes to identify distinct molecular subtypes. Train a supervised classifier (e.g., Random Forest) to assign new samples to these subtypes [18].

- Regulatory Network and Master Regulator Analysis: For each molecular subtype, infer a subtype-specific regulatory network. Use master regulator analysis (e.g., using the Algorithm for the Reconstruction of Accurate Cellular Networks, ARACNe) to identify key transcription factors that drive the subtype's gene expression profile [18].

- Drug Sensitivity Analysis and Repurposing: Correlate the expression of master regulators with publicly available drug sensitivity databases (e.g., GDSC, CTRP). Prioritize existing drugs or compounds that are predicted to be effective against a specific molecular subtype, thereby repurposing therapeutic candidates [18].

Protocol 2: Validating AI-Discovered Targets with Experimental Assays

This protocol outlines the critical steps for transitioning from an AI-generated hypothesis to experimental validation, a cornerstone of credible computational research [16].

Summary: After an AI model identifies a potential therapeutic target or drug candidate, this protocol guides the initial in vitro validation to confirm the predicted biological mechanism.

Step-by-Step Instructions:

- Hypothesis Definition from AI Output: Clearly state the AI-generated prediction. Example: "The CK2 inhibitor silmitasertib will synergistically enhance antigen presentation (MHC-I expression) only in the presence of low-dose interferon-gamma (IFN-γ)" [16].

- Cell Model Selection: Choose a relevant human cell model for the cancer type. Using a cell type that was not part of the AI model's training data strengthens the validation [16].

- Design Experimental Arms: Establish at least four treatment conditions:

- Arm A: Vehicle control (DMSO).

- Arm B: AI-predicted drug alone (e.g., silmitasertib).

- Arm C: Contextual signal alone (e.g., low-dose IFN-γ).

- Arm D: Combination (e.g., silmitasertib + low-dose IFN-γ) [16].

- Execute and Measure: Treat cells according to the experimental design. Use a standardized assay (e.g., flow cytometry) to quantitatively measure the relevant outcome (e.g., surface MHC-I expression). Perform multiple biological replicates.

- Analyze for Synergy: Statistically compare the results across all arms. A successful validation is indicated by a significant increase in the outcome measure only in Arm D (the combination), confirming the AI's prediction of a conditional or synergistic effect [16].

Signaling Pathways, Workflows, and Logical Diagrams

Multi-Omics AI Integration Workflow

Diagram 1: A high-level workflow for integrating multi-omics data using AI for cancer target identification.

PD-L1/IDO1 Signaling and AI Modulation

Diagram 2: Key immune checkpoint pathways (PD-L1/IDO1) and their modulation by AI-predicted small molecules.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Experiments

This table lists essential materials and tools used in the AI-driven cancer research pipeline, from computational analysis to experimental validation [18] [16].

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomic Data (e.g., TCGA) | Provides standardized RNA-seq data from thousands of tumor and normal samples for initial model training and discovery. | Developing a prognostic gene signature for gastric tumors [18]. |

| CK2 Inhibitor (e.g., Silmitasertib/CX-4945) | A small molecule kinase inhibitor used to experimentally test AI-generated hypotheses about modulating antigen presentation. | Validating the synergistic effect with low-dose interferon-gamma in neuroendocrine cell models [16]. |

| Digital Pathology Slide Scanner | Converts glass histopathology slides into high-resolution digital images for analysis by Deep Learning models (CNNs). | Enabling AI-powered detection of HRD characteristics (DeepHRD) from standard biopsy slides [17]. |

| Flow Cytometry Assay | A core laboratory technique for quantifying protein expression on the surface (e.g., MHC-I) or inside single cells. | Measuring the increase in antigen presentation on tumor cells after drug treatment [16]. |

| Biomedical NLP Toolkit (e.g., BioBERT) | A pre-trained language model designed to understand biomedical text, improving tasks like Named Entity Recognition. | Extracting relationships between genes, diseases, and drugs from scientific literature at scale [15]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Data Access and Quality Control

- A1: Access issues often stem from browser, tool, or authentication problems. Follow these steps:

- Verify Data Availability: Confirm the file exists in the latest GDC Data Release. The GDC portal and announcements detail available data types and releases [21].

- Clear Browser Cache: Outdated cache can cause portal errors. Clear it and try again.

- Check GDC Status: Check the GDC website for scheduled maintenance or system outage announcements [21].

- Update Data Transfer Tool: Ensure you use the latest GDC Data Transfer Tool (DTT) client. Older versions may have compatibility issues [21].

- Review Access Authority: Controlled-access data requires dbGaP authorization. Verify your approval for the specific dataset.

Q2: After acquiring multi-omics data, what are the first critical steps to ensure data quality before integration?

- A2: Initial quality control (QC) is paramount to avoid propagating technical artifacts.

- Conduct Platform-Specific QC: For each data type (e.g., WGS, RNA-Seq, proteomics), use established pipelines to assess metrics like sequencing depth, mapping rates, and sample-level correlations [22].

- Perform Batch Effect Detection: Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or other methods to visualize data and check for groupings by processing date, sequencing lane, or other technical factors [22] [23].

- Apply Batch Correction: If batch effects are detected, apply correction algorithms like ComBat to remove technical variance without affecting biological signal [22].

- Address Missing Data: Develop a strategy for missing values, which may involve imputation using matrix factorization or deep learning methods, or removal of features with excessive missingness [23].

Troubleshooting Guide: Multi-Omics Data Integration

Q3: When integrating high-dimensional multi-omics data for model training, my models are overfitting. How can I improve generalizability?

- A3: Overfitting in multi-omics is common due to high feature-to-sample ratios.

- Employ Dimensionality Reduction: Use feature selection (e.g., based on variance) or extraction techniques (e.g., autoencoders) before model training to reduce noise [23].

- Utilize Regularization: Apply L1 (Lasso) or L2 (Ridge) regularization within your models to penalize complex, overfit solutions [23].

- Implement Rigorous Validation: Always use held-out test sets and cross-validation. Consider federated learning approaches, which train models across multiple institutions without sharing raw data, to enhance robustness and generalizability [22] [23].

- Incorporate Biological Networks: Use prior knowledge (e.g., protein-protein interaction networks) with Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) for more biologically meaningful integration than simple data concatenation [23].

Q4: How can I handle the challenge of missing data from one or more omics layers in a subset of my patient samples?

- A4: The choice of method depends on the extent and mechanism of missingness.

- For Small-Scale Missingness: Use imputation methods like multivariate imputation by chained equations (MICE) or k-nearest neighbors (KNN).

- For Large-Scale or Complex Missingness: Leverage generative deep learning models, such as Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) or Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which are particularly effective at synthesizing plausible multi-omics data to address missingness and class imbalance [23].

Troubleshooting Guide: High-Throughput Screens and Validation

Q5: My high-throughput drug screen results show high variability and poor reproducibility. What factors should I investigate?

- A5: Technical and biological noise can compromise screen quality.

- Audit Laboratory Protocols: Ensure consistent cell culture conditions, passage numbers, and reagent quality across all assay plates.

- Normalize Plate Effects: Use within-plate positive and negative controls to normalize for edge effects, evaporation, or dispenser errors.

- Employ Robust Statistical Scoring: Use metrics like Z'-factor to assess assay quality and quantify the separation between positive and negative controls.

- Integrate Multi-Omics Data: Correlate drug response with baseline multi-omics data (e.g., mutation status, gene expression) to identify molecular predictors of sensitivity, which can validate screen findings biologically [22] [11].

Q6: How can I validate a target identified computationally from TCGA data using experimental biology?

- A6: Computational findings require rigorous experimental confirmation.

- In Vitro Functional Studies: Use siRNA or CRISPR-Cas9 to knock down/out the target gene in relevant cancer cell lines and assay for changes in proliferation, invasion, or apoptosis.

- Ex Vivo Validation: Correlate target expression or mutation status with patient outcomes (e.g., survival, treatment response) in independent clinical cohorts or patient-derived organoids.

- Leverage Multi-Omics for Context: Integrate proteomic or phosphoproteomic data to understand the target's functional role within signaling networks and identify potential resistance mechanisms [22].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Protocol 1: Multi-Omics Data Preprocessing and Integration for Classifier Development

This protocol outlines a workflow for processing diverse omics data from the GDC to build a robust molecular subtype classifier [22].

- Data Acquisition: Download harmonized Level 3 or 4 data (e.g., gene expression counts, somatic mutations, copy number variations) for your cancer of interest from the GDC Data Portal [21].

- Quality Control (QC):

- Genomics/Transcriptomics: Filter out genes with near-zero counts or variants with low allele frequency. Check for outlier samples using PCA.

- Proteomics: Remove proteins with many missing values. Impute remaining missing values using a method like KNN.

- Data Normalization:

- Apply platform-specific normalization (e.g., DESeq2 for RNA-Seq data, quantile normalization for proteomics data) [22].

- Feature Selection:

- Reduce dimensionality by selecting top variable features or those with known biological relevance to the cancer type.

- Data Integration and Model Training:

- Concatenate selected features from different omics layers into a unified matrix.

- Train a classifier (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machine) using a cross-validated framework to predict known molecular subtypes.

- Model Interpretation:

Protocol 2: Cross-Platform Validation of a Transcriptomic Signature

This protocol ensures a gene expression signature derived from one platform (e.g., RNA-Seq) is valid and actionable on another (e.g., NanoString or RT-qPCR).

- Signature Definition: Define your gene signature from the discovery cohort (e.g., TCGA RNA-Seq data).

- Independent Cohort Selection: Identify a validation cohort with matching clinical data from a public repository (e.g., GEO) or an in-house dataset.

- Data Harmonization:

- Map the signature genes to their counterparts in the validation dataset.

- Apply the same normalization and scaling procedures used in the discovery phase to the validation data.

- Score Calculation: Calculate the signature score for each sample in the validation cohort using the same method (e.g., single-sample GSEA, mean of Z-scores).

- Statistical Validation:

- Test the association between the signature score and the clinical endpoint (e.g., overall survival using a Cox model, or response to therapy using a t-test) in the validation cohort.

- A statistically significant result in the independent cohort strengthens the validity of your computational model.

Table 1: Key NCI Genomic Data Commons (GDC) Data Releases and Content

This table summarizes recent data releases from the GDC, a primary source for TCGA and other multi-omics data [21].

| Data Release | Key Highlights and New Data Projects |

|---|---|

| Data Release 44 | New projects, new cases from existing projects. |

| Data Release 43 | New and updated data sets. |

| Data Release 42 | Release of 8,000+ new whole genome sequencing (WGS) variant calls. |

| Data Release 41 | New data sets for NCI-MATCH Trial arms, whole slide images. |

| Data Release 40 | Additional TCGA WGS alignments and variant calls, WXS and RNA-Seq data for new NCI-MATCH Trial arms. |

| Data Release 39 | New TCGA WGS variants, additional higher coverage alignments, five new projects from NCI’s MATCH program. |

Table 2: AI Model Applications in Oncology Data Analysis

This table categorizes artificial intelligence models by their primary application in processing complex oncology data [11].

| AI Model Type | Primary Data Modalities | Example Applications in Oncology |

|---|---|---|

| Classical Machine Learning (ML) | Structured data: genomic biomarkers, lab values [11]. | Survival prediction, therapy response [11]. |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | Imaging data: histopathology, radiology [11]. | Tumor detection, segmentation, and grading; automatic quantification of IHC staining [22] [11]. |

| Transformers / Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) | Sequential/text data: genomic sequences, clinical notes [11]. | Biomarker discovery, electronic health record (EHR) mining [11]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Biological networks, multi-omics data [22]. | Modeling protein-protein interaction networks to prioritize druggable hubs [22]. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Multi-Omics AI Integration Workflow

Cancer Target Identification & Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Computational Oncology Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Validation |

|---|---|

| siRNA / shRNA Libraries | Gene knockdown to assess the functional necessity of a computationally identified target on cellular phenotypes (e.g., proliferation, apoptosis). |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout Kits | Complete gene knockout for definitive functional validation of a candidate cancer target. |

| Patient-Derived Organoid (PDO) Cultures | Ex vivo models that retain tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment, used for high-throughput drug testing and validating target relevance. |

| Multiplex Immunohistochemistry (mIHC) Kits | Simultaneous detection of multiple protein biomarkers on a single tissue section to validate protein-level expression and spatial relationships predicted by multi-omics models. |

| Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) Assay Kits | For non-invasive monitoring of tumor dynamics and resistance mutations during treatment, validating predictive models of therapy response [22]. |

The traditional single-target paradigm in cancer drug discovery, often guided by serendipitous findings, is increasingly giving way to a more systematic, network-based approach. This shift is driven by the critical challenge of drug resistance, where cancer cells bypass inhibited single targets by activating alternative pathways [24]. Furthermore, analysis of clinical trials reveals a "drug discovery winter," with over 96% of trials focusing on previously tested drug targets and only 12% of the human interactome being targeted [25]. If current patterns persist, it would take an estimated 170 years to target all druggable proteins [25].

Network-based approaches address these limitations by modeling the complex interactions within cancer systems, moving beyond the "tunnel vision" of single-target strategies to a more holistic view of drug mechanisms [26]. These methods leverage computational tools to identify optimal target combinations that can counteract resistance mechanisms by simultaneously targeting multiple nodes in cancer signaling networks [24].

Key Computational Tools and Methodologies

Network Analysis and Target Identification Tools

Table 1: Computational Tools for Network-Based Target Identification

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Validation/Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepTarget [26] | Predicts primary & secondary targets of small-molecule agents | Integrates drug/genetic knockdown viability screens & omics data; open-source | Outperformed RoseTTAFold All-Atom & Chai-1 in 7/8 drug-target test pairs |

| Network-Informed Signaling-Based Approach [24] | Discovers optimal drug target combinations to counter resistance | Uses PPI networks & shortest paths (PathLinker algorithm) | Validated in patient-derived breast & colorectal cancers; resulted in tumor diminishment |

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) [24] | Optimizes drug combination prioritization | Semantic relationships between drug and disease; pathway crosstalk analysis | Identified rare, contingent drug synergies in cancer cell lines |

| Multi-dimensional Bioinformatic Analysis [27] | Identifies key therapeutic targets through integrative genomics | Combines Mendelian randomization, WGCNA, PPI networks, and eQTL/pQTL analyses | Identified and validated EGLN1 as a core causal protective target in high BMI-associated CRC |

Table 2: Essential Data Resources for Network-Based Cancer Research

| Resource Name | Data Type | Application in Network Modeling | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [28] [24] | Multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, etc.) | Provides molecular profiles for 11,000+ tumor samples; identifies shared oncogenic drivers | Publicly available |

| HIPPIE PPI Database [24] | Protein-protein interactions | High-confidence human interactome for network path calculations | Publicly available |

| UCSC Genome Browser [28] | Multi-omics data integration | Copy number variations, methylation profiles, gene/protein expression | Publicly available |

| Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [28] | Gene expression data | Microarray and RNA-Seq data for cross-cancer pattern analysis | Publicly available |

| ClinicalTrials.gov [25] | Clinical trial metadata | Analysis of drug exploration patterns and target selection trends | Publicly available |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the fundamental limitations of single-target approaches that network methods address? Single-target therapies frequently succumb to resistance because cancer cells activate alternative pathways (bypass mechanisms) [24]. Network analysis reveals that this resistance occurs through "local network effects" - when inhibition of one node simply shifts signaling to interacting proteins in the same network neighborhood [25]. Additionally, clinical trial data shows that the current drug discovery paradigm is stuck in a cycle of repeatedly targeting the same proteins, leaving most of the druggable genome unexplored [25].

Q2: How do we select the most relevant protein-protein interaction network for our specific cancer type? Network selection should be guided by confidence scores and biological relevance. The HIPPIE database provides a high-confidence, scored human interactome that has been successfully applied to breast and colorectal cancers [24]. For specific cancer contexts, integrate your own omics data (e.g., from TCGA) to filter networks to cancer-relevant interactions. Always validate that your proteins of interest are represented in the chosen network.

Q3: What computational workflow can we use to identify key bridge nodes in signaling networks? The following diagram illustrates a validated workflow for identifying critical bridge nodes in cancer networks:

Q4: How can we validate that computationally predicted network targets have real biological relevance? Validation requires a multi-step approach: First, use functional enrichment analysis (GO/KEGG) to confirm pathways are cancer-relevant [27]. Second, correlate target expression with patient outcomes using TCGA data. Third, perform experimental validation in relevant models - for example, testing alpelisib + LJM716 combinations in breast cancer PDXs or using in vitro assays to confirm that compounds like Cianidanol inhibit proliferation and invasion in CRC cells [24] [27].

Q5: What are the key metrics for evaluating the performance of network-based target prediction tools? Benchmark computational tools against established methods using metrics like prediction accuracy across diverse datasets, performance in real-world case studies (e.g., drug repurposing predictions), and experimental validation success rates [26]. For example, DeepTarget was benchmarked against RoseTTAFold and Chai-1 across eight drug-target test pairs [26].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Network Construction and Analysis Issues

Problem: Incomplete or low-quality PPI networks leading to inaccurate paths

- Solution: Use integrated, confidence-scored databases like HIPPIE [24]. Filter interactions by confidence score threshold (typically >0.7). Cross-reference with cancer-specific interaction databases to ensure biological relevance.

- Prevention Strategy: Perform sensitivity analysis by comparing results across different PPI resources. Validate that known interactions in your pathway of interest are present.

Problem: Too many potential bridge nodes identified, making prioritization difficult

- Solution: Implement multi-parameter filtering: (1) Calculate betweenness centrality, (2) Check druggability using databases like DrugBank, (3) Verify differential expression in cancer vs. normal tissue, (4) Check association with patient survival [24] [27].

- Prevention Strategy: Define clear criteria for bridge nodes upfront based on network topology measures and biological constraints.

Validation and Experimental Translation Challenges

Problem: Computational predictions fail to validate in cellular models

- Solution: This often indicates poor model specificity. Return to network analysis and: (1) Check if identified paths are active in your specific cell line using expression data, (2) Analyze potential compensatory mechanisms, (3) Consider combination targeting rather than single nodes [24].

- Prevention Strategy: Use cell line-specific omics data to filter networks before analysis. Implement multi-omics integration to ensure identified paths are transcriptionally active.

Problem: Drug combinations show unexpected toxicity despite computational prediction

- Solution: Network models might miss tissue-specific effects. (1) Analyze target expression in healthy tissues, (2) Check for pathway enrichment in essential processes, (3) Use more selective inhibitors or adjusted dosing schedules [24].

- Prevention Strategy: Incorporate tissue-specific networks where available. Perform differential pathway analysis between tumor and normal tissues.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Network-Based Target Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Case | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PathLinker Algorithm [24] | Identifies k-shortest paths in PPI networks | Finding signaling paths between proteins with co-existing mutations | Default k=200 provides balance between coverage and computational cost |

| Alpelisib (PIK3CA inhibitor) [24] | PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway inhibition | Combination therapy in PIK3CA-mutated breast cancers | Resistance common via alternative pathways; requires combination targeting |

| Cianidanol [27] | EGLN1 modulator; natural compound | Targeting high BMI-associated colorectal cancer | Binding affinity: -11.24 kcal/mol; inhibits proliferation, migration, invasion |

| Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDXs) [24] | Preclinical validation of target combinations | Testing network-predicted combinations in physiologically relevant models | Maintains tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment interactions |

| Single-cell RNA Sequencing [27] | Cell-type specific target validation | Identifying EGLN1 enrichment in T cells and intestinal epithelial cells | Reveals tumor microenvironment context of targets |

| LJM716 (Anti-ERBB3 antibody) [24] | ERBB3/herceptin resistance inhibition | Combination with alpelisib in breast cancer targets | Targets resistance mechanism to PI3K inhibition |

Advanced Methodologies: Experimental Protocols for Network Target Validation

Protocol: Network-Based Combination Target Identification

Based on: Szalai B. et al. "Discovering anticancer drug target combinations via network-informed signaling-based approach" [24]

Workflow Diagram:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Collection: Obtain somatic mutation data from TCGA and/or AACR GENIE databases. Focus on primary tumor samples and remove low-confidence variants [24].

- Identify Co-existing Mutations: Perform pairwise analysis across proteins to find statistically significant mutation co-occurrences using Fisher's Exact Test with multiple testing correction [24].

- Network Construction: Download high-confidence human PPI network from HIPPIE. Filter interactions by confidence score threshold.

- Path Calculation: Use PathLinker algorithm (k=200) to compute shortest paths between proteins harboring co-existing mutations [24].

- Bridge Node Identification: Extract all nodes from calculated paths. Calculate betweenness centrality to identify critical bridge nodes.

- Target Selection: Prioritize bridge nodes that connect alternative signaling pathways to prevent bypass resistance.

- Experimental Validation: Test predicted target combinations in patient-derived xenograft models measuring tumor growth inhibition [24].

Protocol: Multi-dimensional Target Validation for Context-Specific Therapies

Based on: Yu X. et al. "Identification and validation of EGLN1 as a key target" [27]

Workflow Diagram:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Causal Inference: Perform two-sample Mendelian randomization to establish causal relationships between risk factors (e.g., high BMI) and cancer outcomes [27].

- Multi-omics Integration: Analyze differentially expressed genes and construct weighted gene co-expression networks (WGCNA) from transcriptomic data.

- Network Analysis: Build protein-protein interaction networks from intersecting gene sets and identify hub genes using topological analysis [27].

- Molecular QTL Integration: Perform eQTL and pQTL analyses to identify causal targets, followed by phenome-wide association studies to assess pleiotropy.

- Mechanistic Elucidation: Conduct single-gene GSEA and single-cell RNA sequencing to understand target function across cell types. Perform gut microbiota mediation analysis if relevant [27].

- Compound Screening: Computational screening of compound libraries followed by molecular docking to identify potential therapeutics.

- Functional Validation: In vitro assays measuring cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and target protein expression changes [27].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Q: My computational model shows high accuracy in validation but fails in biological assays. What could be wrong? A: This often indicates overfitting or a failure to account for biological context. Key troubleshooting steps include:

- Verify Feature Biological Relevance: Ensure the input features (e.g., gene mutations, expression levels) have a documented causal relationship with the cancer phenotype, not just correlation.

- Check Data Leakage: Confirm that no information from your test set (e.g., patient outcomes) was used during the training phase of the model.

- Assay Translation Fidelity: Validate that your in vitro or in vivo assay system accurately recapitulates the human tumor microenvironment relevant to your target.

Q: How can I determine if my model's prediction is statistically significant and not due to chance? A: Implement robust statistical testing.

- Perform Permutation Testing: Randomly shuffle your outcome labels (e.g., "sensitive" vs. "resistant") and re-run your model multiple times (e.g., 1000 permutations). The p-value is the proportion of permutations where the model performance meets or exceeds the performance with the true labels.

- Apply Multiple Hypothesis Correction: If testing multiple hypotheses (e.g., many potential drug targets), use corrections like Bonferroni or Benjamini-Hochberg to control the false discovery rate (FDR).

Q: My visualization diagram has poor readability. How can I improve color contrast for nodes and text? A: Adhere to established color contrast rules.

- For Node Text: Explicitly set the

fontcolorattribute to ensure high contrast against the node'sfillcolor. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) recommend a contrast ratio of at least 4.5:1 [29] [30]. - For Diagram Elements: Avoid using similar colors for foreground elements (like arrows or symbols) and the background. Use a color contrast checker to verify ratios [31].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the minimum validation steps required before a computational prediction can be considered for wet-lab experimentation? A: At a minimum, validation should include:

- Internal Validation: Use cross-validation on the training dataset to assess model stability.

- External Validation: Test the model's performance on a completely independent dataset, preferably from a different source or institution.

- Benchmarking: Compare your model's performance against established baseline methods or random predictors.

Q: Which statistical metrics are most informative for validating a classification model in this context? A: Rely on a suite of metrics, as no single metric tells the whole story.

- AUC-ROC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve): Assesses the model's ability to distinguish between classes across all thresholds.

- Precision and Recall: Crucial when dealing with imbalanced datasets (e.g., few true positives among many candidates).

- F1-Score: The harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single balanced metric.

Q: How can I visually represent my experimental workflow and prediction logic clearly? A: Use Graphviz to create standardized diagrams. The DOT language allows you to define nodes, edges, and their properties systematically, ensuring consistency and clarity in your visual communications [32].

Quantitative Validation Criteria Table

The following table outlines key quantitative thresholds for model validation.

| Validation Metric | Minimum Threshold for Consideration | Target for Clinical Actionability | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC-ROC | > 0.70 | > 0.85 | Area Under the Curve; robust to class imbalance [31]. |

| Precision | > 0.80 | > 0.95 | Measures the fraction of true positives among all positive predictions. |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | > 0.70 | > 0.85 | Measures the fraction of actual positives correctly identified. |

| F1-Score | > 0.75 | > 0.90 | Harmonic mean of precision and recall. |

| p-value (vs. Random) | < 0.05 | < 0.01 | Derived from permutation testing. |

| False Discovery Rate (FDR) | < 0.10 | < 0.05 | Adjusted p-value for multiple comparisons. |

Experimental Protocol:In VitroValidation of a Predicted Cancer Target

Objective: To experimentally validate a computationally predicted cancer gene target for essentiality in a specific cell line.

Methodology: CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout and Viability Assay

sgRNA Design:

- Design 4-6 single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting the exon of the predicted gene.

- Design non-targeting control sgRNAs.

Lentiviral Transduction:

- Clone sgRNAs into a lentiviral vector (e.g., lentiCRISPRv2).

- Produce lentiviral particles in HEK293T cells.

- Transduce the target cancer cell line at a low MOI (Multiplicity of Infection) to ensure single copy integration.

- Select transduced cells with puromycin (2 µg/mL) for 72 hours.

Cell Viability Measurement:

- Seed selected cells in 96-well plates.

- Monitor cell viability for 5-7 days using a CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay.

- Measure luminescence daily.

Data Analysis:

- Normalize luminescence readings to the day of selection (Day 0).

- Compare the growth curve of cells with the target gene knocked out to those with non-targeting control sgRNAs.

- A statistically significant reduction in viability for the target knockout group validates the prediction.

Visualization Diagrams

Model Validation Workflow

This diagram outlines the logical flow from computational prediction to experimental validation.

Signaling Pathway Impact

This diagram illustrates how a predicted target hypothetically impacts a core cancer signaling pathway.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| lentiCRISPRv2 Plasmid | A lentiviral vector for the stable delivery of the CRISPR-Cas9 system and sgRNA for gene knockout studies. |

| Puromycin | A selection antibiotic used to eliminate non-transduced cells and create a pure population of CRISPR-edited cells. |

| CellTiter-Glo Assay | A luminescent assay that measures ATP levels as a proxy for metabolically active, viable cells in culture. |

| HEK293T Cell Line | A highly transfectable cell line commonly used for the production of lentiviral particles. |

| Non-Targeting Control sgRNA | A critical control sgRNA that does not target any genomic sequence, used to account for non-specific effects of the CRISPR system. |

Tools of the Trade: A Deep Dive into Cutting-Edge Computational Frameworks and Their Real-World Applications

Core Concepts and Workflow

What is DeepTarget and what is its primary function?

DeepTarget is a computational tool that predicts the mechanisms of action (MOA) driving a drug's anti-cancer efficacy. It integrates large-scale drug viability screens, genetic knockdown viability screens (specifically CRISPR-Cas9 knockout), and omics data (gene expression and mutation) from matched cancer cell lines to identify both primary and secondary drug targets, as well as mutation-specificity preferences [33] [34] [35]. Unlike structure-based methods that predict direct binding, DeepTarget captures both direct and indirect, context-dependent mechanisms driving drug efficacy in living cells [34].

What is the fundamental hypothesis behind DeepTarget's approach?

DeepTarget operates on the principle that CRISPR-Cas9 knockout (CRISPR-KO) of a drug’s target gene mimics the drug’s inhibitory effects across a panel of cancer cell lines. Therefore, identifying genes whose deletion induces similar viability patterns to drug treatment can reveal the drug's potential targets [34].

The following diagram illustrates the core three-step prediction pipeline of DeepTarget.

Performance and Validation Data

DeepTarget's performance was rigorously benchmarked against state-of-the-art tools across eight high-confidence, gold-standard datasets of cancer drug-target pairs [34] [26]. The following table summarizes its key quantitative performance metrics.

| Validation Metric | Performance Result | Comparative Performance (vs. RosettaFold & Chai-1) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Target Prediction (Mean AUC across 8 datasets) | AUC 0.73 [34] [26] | Outperformed in 7 out of 8 datasets [34] [35] |

| Secondary Target Prediction | AUC 0.92 (vs. known multi-target drugs) [34] [36] | Not directly compared |

| Mutation-Specificity Prediction | AUC 0.78 (distinguishing mutant-specific inhibitors) [36] | Not directly compared |

| Dataset Scale | Predictions for 1,500 cancer-related drugs and 33,000 natural product extracts [33] [26] | N/A |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Data Input and Preprocessing

Q: What are the specific data requirements to run DeepTarget? A: DeepTarget requires three types of data across a panel of cancer cell lines [34]:

- Drug Response Profiles: Viability data for the drug of interest. The source study used data for 1,450 drugs across 371 cancer cell lines from the DepMap repository.

- Genetic Knockdown Viability Profiles: Genome-wide CRISPR-KO viability profiles. The tool uses Chronos-processed CRISPR dependency scores to account for technical confounders.

- Omics Data: Corresponding gene expression and mutation data for the same cell lines.

Q: My gene of interest is not a known direct binding partner, yet it appears as a high-ranking prediction. Is this an error? A: Not necessarily. DeepTarget's predictions can include both direct binding targets and other genes in the drug’s mechanism of action pathway [34]. To distinguish between these, use the provided post-filtering steps (e.g., restricting to kinase proteins for kinase inhibitors) and pathway enrichment analysis to gain a systems-level view [34].

Interpretation of Results

Q: What does the Drug-KO Similarity (DKS) Score represent? A: The DKS score is a Pearson correlation quantifying the similarity between a drug's response profile and the viability profile resulting from knocking out a specific gene [34]. A higher score indicates stronger evidence that the gene is involved in the drug's mechanism of action.

Q: How does DeepTarget define and identify secondary targets? A: The tool identifies two types of context-specific secondary targets [34]:

- Type A: Those contributing to efficacy even when primary targets are present, identified via de novo decomposition of drug response.

- Type B: Those mediating responses specifically when primary targets are not expressed, identified by computing Secondary DKS Scores in cell lines lacking primary target expression.

Q: The tool seems to perform poorly for my drug targeting a GPCR. Why? A: This is a known current limitation. DeepTarget struggles on certain target classes like GPCRs, nuclear receptors, and ion channels [36]. For these, structure-based tools may currently be preferred if high-resolution structural data is available.

Experimental Validation Protocols

A key strength of DeepTarget is the experimental validation of its predictions. Below are detailed protocols for the case study that validated a secondary target.

Protocol: Validating a Predicted Secondary Target (Ibrutinib-EGFR)

Background: DeepTarget predicted that Ibrutinib, a drug whose primary target is BTK, kills lung cancer cells by acting on a secondary target, mutant EGFR, specifically the T790-mutated form [35] [37].

Objective: To experimentally validate that cancer cells harboring the mutant EGFR T790 are more sensitive to Ibrutinib.

Materials:

- Cell Lines: Lung cancer cell lines isogenic for the EGFR T790 mutation (with and without the mutation) [35] [37].

- Drug: Ibrutinib (FDA-approved BTK inhibitor).

- Equipment: Cell culture facility, equipment for measuring cell viability (e.g., plate reader for MTT or CellTiter-Glo assays).

Methodology:

- Cell Culture: Maintain the paired cell lines in standard conditions.

- Drug Treatment: Treat cells with a range of Ibrutinib concentrations.

- Viability Assay: Measure cellular viability after a predetermined incubation period (e.g., 72 hours) using a standard assay.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for Ibrutinib in both cell lines. A statistically significant lower IC50 in the mutant EGFR T790 cell line compared to the wild-type control confirms higher sensitivity and validates EGFR as a functional secondary target [35] [37].

Expected Outcome: Cells with the EGFR T790 mutation will show significantly greater sensitivity (lower IC50) to Ibrutinib, confirming the prediction.

This experimental workflow for secondary target validation is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and resources used in the development and validation of DeepTarget.

| Reagent / Resource | Function in DeepTarget Workflow | Source / Example |

|---|---|---|

| DepMap Data | Provides the foundational drug response, CRISPR knockout, and omics data across hundreds of cancer cell lines. | Dependency Map (DepMap) Consortium [34] [37] |

| Chronos-Processed CRISPR Scores | Provides corrected, high-quality genetic dependency scores, accounting for sgRNA efficacy, copy number effects, and other confounders. | DepMap/Chronos Algorithm [34] |

| Gold-Standard Datasets | Used for benchmarking and validating prediction accuracy against known, high-confidence drug-target interactions. | COSMIC, oncoKB, DrugBank, SelleckChem [34] |

| Open-Source Code | Allows researchers to run the DeepTarget algorithm on their own data. | GitHub Repository (CBIIT-CGBB/DeepTarget) [33] [34] |

| Predicted Target Profiles | Pre-computed predictions for thousands of compounds, enabling immediate hypothesis generation. | Provided for 1,500 drugs & 33,000 natural extracts [33] [26] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary purpose of the DrugAppy workflow? DrugAppy is an end-to-end deep learning framework designed for computational drug discovery. Its primary purpose is to identify druggable oncogenic vulnerabilities and design novel chemical entities against them, significantly accelerating the inhibitor discovery and optimization process. It uses a hybrid model that combines Artificial Intelligence (AI) algorithms with computational and medicinal chemistry methodologies. [38]

Q2: Which specific case studies have validated the DrugAppy workflow? The framework has been successfully validated through two key case studies:

- PARP1 Inhibitors: DrugAppy identified two molecules with activity comparable to the reference inhibitor olaparib. [38]

- TEAD4 Inhibitors: The workflow discovered a compound that outperforms the activity of IK-930, the reference inhibitor for this target. [38]

Q3: What computational tools are integrated into the DrugAppy workflow? DrugAppy is built on an imbrication of several specialized computational tools, each with a specific function [38]:

- SMINA & GNINA: Used for High Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) to rapidly evaluate compound binding.

- GROMACS: Employed for Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to study the dynamic behavior and stability of protein-ligand complexes.

- Proprietary AI Models: Trained on public datasets to predict key parameters like drug pharmacokinetics, selectivity, and potential activity.

Q4: My virtual screening results in an unmanageably high number of hits. How can I refine them? A high number of hits is common. The DrugAppy workflow addresses this by employing a multi-stage filtering process [38]. After the initial HTVS, hits are progressed to more rigorous molecular dynamics simulations using tools like GROMACS to assess binding stability. Furthermore, key parameters such as ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) properties are predicted using AI models to prioritize candidates with desirable drug-like properties early in the process.

Q5: How can I characterize covalent inhibitors, which pose unique experimental challenges? Characterizing covalent inhibitors requires specific protocols. An enzyme activity-based workflow is recommended, which uses continuous assays to monitor time-dependent inhibition. This method streamlines the evaluation of these inhibitors by focusing on their functional impact on enzyme activity, enhancing the reliability and reproducibility of their assessment. [39]

Q6: The AI model's predictions for my novel target seem unreliable. What could be wrong? Unreliable predictions can often be traced to data quality or model applicability. Ensure that the training data used by the model is of high quality and relevant to your specific target. For novel targets with limited data, fine-tuning the model on a high-dimensional, target-specific dataset may be necessary to improve accuracy and generalizability. [40]

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Binding Affinity Predictions during Virtual Screening

Problem: The binding affinity scores (e.g., from SMINA/GNINA) for your top hits are weak or do not correlate with subsequent experimental results.

Solution:

- Check Input Structures: Verify the protonation states and tautomeric forms of both the ligand and the protein binding site residues. Incorrect states can severely impact scoring.

- Refine Scoring Functions: Do not rely on a single scoring function. Use consensus scoring from multiple functions or consider re-scoring top hits with more computationally intensive, but potentially more accurate, methods.

- Progress to Dynamics: Move promising but weak hits to molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. MD can reveal stabilizing interactions that static docking misses and provide a more realistic assessment of binding stability and affinity over time. [38]

Issue: Inefficient Hyperparameter Tuning in AI Models

Problem: The deep learning models used for activity prediction are slow to train and converge to suboptimal performance.

Solution: Implement an advanced optimization framework like optSAE + HSAPSO (Hierarchically Self-Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization). This hybrid approach integrates a stacked autoencoder for robust feature extraction with an adaptive PSO algorithm for hyperparameter tuning. This method has been shown to achieve high accuracy (95.52%) and significantly reduced computational complexity (0.010 seconds per sample). [40]

Issue: High Computational Cost of Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Problem: MD simulations with GROMACS for a large number of hits are prohibitively time-consuming and resource-intensive.

Solution:

- Strategic Sampling: Use the results from HTVS to create a highly focused subset of compounds for MD. Prioritize compounds with diverse chemotypes and strong binding scores.

- Active Learning Workflow: Implement an active learning pipeline that uses machine learning to select the most informative compounds for MD simulation, thereby reducing the total number of simulations required. This approach has been shown to get information from calculations 20 times faster than a brute-force approach. [41]

- Leverage HPC Resources: Utilize high-performance computing (HPC) environments, such as those offered by national supercomputing centers, to run multiple simulations in parallel. [41]

Key Experimental Data and Protocols

The following table summarizes the quantitative results from the case studies used to validate the DrugAppy workflow.

Table 1: DrugAppy Performance in Case Study Validation [38]

| Target | Reference Inhibitor | DrugAppy Discovery | Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| PARP1 | Olaparib | Compound 1 | Activity comparable to Olaparib |

| PARP1 | Olaparib | Compound 2 | Activity comparable to Olaparib |

| TEAD4 | IK-930 | Novel Compound | Activity surpasses IK-930 |

Workflow for Covalent Inhibitor Characterization

This protocol outlines a robust, enzyme activity-based method for characterizing covalent inhibitors, which is crucial for assessing their unique mechanism of action. [39]

Principle: The protocol uses a continuous enzyme activity assay to monitor the time-dependent inhibition that is characteristic of covalent modifiers. The gradual, irreversible (or slowly reversible) inactivation of the enzyme results in a change in the assay signal over time.

Materials:

- Purified target enzyme

- Putative covalent inhibitor compounds

- Enzyme substrate and necessary cofactors

- Assay buffer

- Microplate reader capable of kinetic measurements

Procedure:

- Pre-incubation: In a microplate, prepare a mixture of the enzyme and varying concentrations of the inhibitor in an appropriate buffer. Do not add the substrate yet.

- Time-Course Measurement: Initiate the reaction by adding the substrate to the enzyme-inhibitor mixture.

- Data Acquisition: Immediately place the plate in the reader and continuously monitor the product formation (e.g., by absorbance or fluorescence) over a sufficient period (e.g., 30-60 minutes).

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the reaction velocity (signal slope) versus time for each inhibitor concentration.

- For a covalent inhibitor, you will observe a decrease in velocity over time, as more enzyme molecules become irreversibly inhibited.

- Fit the data to an appropriate model for time-dependent inhibition to determine the inhibition rate constant (k~inact~) and the inhibitor concentration that gives half-maximal rate of inactivation (K~I~).

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

DrugAppy End-to-End Workflow

Covalent Inhibitor Assay Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Databases for the DrugAppy Workflow

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Key Feature / Note |

|---|---|---|

| SMINA & GNINA [38] | High Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) for rapid docking of large compound libraries. | Specialized for robust and configurable docking simulations. |

| GROMACS [38] | Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation software to study protein-ligand complex stability and dynamics. | Provides atomic-level insights into binding modes and stability over time. |

| OncoKB [42] | Precision oncology database providing curated information on oncogenic mutations and treatment implications. | Used to validate the clinical relevance of identified targets and inhibitors. |