Validating Cancer Biomarkers with Real-Time PCR: Protocols, Optimization, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) for robust cancer biomarker validation.

Validating Cancer Biomarkers with Real-Time PCR: Protocols, Optimization, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) for robust cancer biomarker validation. It covers foundational principles, from biomarker definitions and assay design to advanced applications in minimal residual disease (MRD) detection and liquid biopsies. The content delivers actionable methodologies for troubleshooting common pitfalls, optimizing assay performance, and conducting rigorous analytical and clinical validation. A comparative analysis of qPCR against emerging technologies like digital PCR and next-generation sequencing is also presented, offering a complete framework for integrating qPCR into precision oncology workflows.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Principles of Biomarkers and qPCR in Oncology

Defining Predictive and Prognostic Biomarkers in Precision Oncology

Precision oncology represents a paradigm shift in cancer care, moving from a one-size-fits-all approach to tailored therapeutic strategies based on the unique molecular characteristics of individual tumors. Central to this approach are biomarkers—measurable biological indicators that provide critical information about disease state, trajectory, and therapeutic responsiveness. Predictive biomarkers identify patients who are likely to respond to a specific treatment, enabling therapy selection based on molecular profiling. In contrast, prognostic biomarkers provide information about overall clinical outcomes, such as disease recurrence or progression, independent of the therapy received [1]. The clinical implementation of these biomarkers, particularly through molecular techniques like real-time PCR (qPCR), requires rigorous validation to ensure analytical and clinical utility within well-defined contexts of use [2].

The evolving landscape of cancer biomarker research now integrates multiple technological approaches, from genomic and epigenomic analyses to proteomic and multiplexed assays. DNA methylation biomarkers, for instance, have emerged as particularly promising tools due to their stability, cancer-specific patterns, and early emergence in tumorigenesis [3]. Meanwhile, technological advances in digital PCR (dPCR) offer enhanced sensitivity for detecting rare mutations in liquid biopsies, facilitating minimal residual disease monitoring and therapy response assessment [4]. This document provides a comprehensive framework for the validation and application of predictive and prognostic biomarkers within precision oncology, with particular emphasis on protocols for real-time PCR-based biomarker validation in cancer research.

Biomarker Classification and Clinical Applications

Defined Biomarker Categories and Their Clinical Utility

Table 1: Classification and Clinical Utility of Key Cancer Biomarkers

| Biomarker Category | Definition | Primary Clinical Utility | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive | Identifies patients likely to respond to a specific treatment | Guides therapy selection; predicts treatment efficacy or resistance | PD-L1, MSI-H/dMMR, HER2, TMB, NTRK fusions [1] [5] |

| Prognostic | Provides information about cancer outcomes independent of treatment | Informs about natural disease history; assesses recurrence risk | TIMP1 in colorectal cancer, LDH, S100B in melanoma [1] [6] |

| Diagnostic | Confirms the presence or type of cancer | Aids in initial disease identification and classification | DNA methylation patterns in liquid biopsies [3] |

| Pharmacodynamic | Measures biological response to therapeutic intervention | Assesses target engagement and biological activity of treatment | ctDNA dynamics during therapy [1] |

Clinically Validated Predictive Biomarkers

Several predictive biomarkers have achieved clinical validation and are now standard in oncology practice. Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression is a key biomarker in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), where patients with PD-L1 expression ≥50% experience significantly improved outcomes with pembrolizumab versus chemotherapy (median overall survival: 30 months versus 14.2 months) [1]. However, limitations exist, including assay variability and tumor heterogeneity, as evidenced by the CheckMate-026 trial where nivolumab failed to show similar survival advantages despite PD-L1 testing [1].

Microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) and mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR) reflect defects in DNA repair pathways, resulting in high mutational burden and neoantigen formation. The FDA granted tissue-agnostic approval to pembrolizumab in 2017 based on trials showing MSI-H tumors had a 39.6% overall response rate with durable responses in 78% of cases [1]. MSI-H/dMMR testing is now recommended in guidelines by the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [1].

Tumor mutational burden (TMB), defined as the number of somatic mutations per megabase, reflects neoantigen load and immunogenicity. Pembrolizumab was approved for TMB ≥10 mutations/Mb based on KEYNOTE-158, which showed a 29% objective response rate versus 6% in low-TMB tumors [1]. Gandara et al. reported that TMB ≥20 mutations/Mb was associated with improved survival across cancers (HR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.47-0.58) [1].

Emerging Biomarker Approaches

Beyond single-analyte biomarkers, multi-omics approaches integrate genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data to improve biomarker precision. Bourbonne et al. demonstrated a ~15% improvement in predictive accuracy using multi-omics with machine learning models [1]. Li et al. identified gene clusters associated with durable response to PD-1 blockade [1]. In the Lung-MAP S1400I trial, high CD8⁺GZB⁺ T-cell infiltration predicted better response to nivolumab, while IL-6 and CXCL13 levels were linked to resistance [1].

Machine learning frameworks like MarkerPredict have been developed to identify predictive biomarkers by integrating network motifs and protein disorder features. This tool uses literature evidence-based training sets with Random Forest and XGBoost machine learning models on signaling networks, classifying target-neighbor pairs with 0.7-0.96 leave-one-out-cross-validation accuracy [7]. The resulting Biomarker Probability Score (BPS) helps rank potential predictive biomarkers for targeted cancer therapeutics [7].

Biomarker Validation Framework and Methodologies

Analytical Validation Requirements

The transition of biomarkers from research tools to clinical applications requires rigorous analytical validation. According to consensus guidelines, analytical validation must establish several key performance characteristics [2]:

- Analytical specificity: The ability of a test to distinguish the target from nontarget analytes

- Analytical sensitivity: The ability to detect the analyte, typically defined as the limit of detection (LOD)

- Analytical precision: The closeness of measurements to each other, including repeatability and reproducibility

- Analytical trueness: The closeness of measured values to true values

These validation parameters must be established within a fit-for-purpose framework, where the level of validation is sufficient to support the specific context of use [2]. For clinical research assays, this represents an intermediate level of validation between research use only (RUO) and fully regulated in vitro diagnostics (IVD) [2].

Clinical Validation and Utility Assessment

Beyond analytical performance, biomarkers must demonstrate clinical validity and utility. Clinical sensitivity reflects the true positive rate (correct identification of subjects with the disease), while clinical specificity reflects the true negative rate (correct identification of subjects without disease) [2]. Positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) are particularly important for clinical implementation, though these are dependent on disease prevalence [2].

The context of use (COU) elements provide a structured framework for defining a biomarker's utility, including: (1) what aspect of the biomarker is measured and in what form, (2) the clinical purpose of the measurements, and (3) the interpretation and decision/action based on the measurements [2]. For biomarkers supporting clinical decision-making, formal qualification concludes that a biomarker allows specific interpretation and application according to its COU in clinical product development [2].

PCR-Based Methodologies for Biomarker Analysis

Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

qRT-PCR remains a cornerstone technology for biomarker validation due to its sensitivity, specificity, and quantitative capabilities. The technique monitors amplification in real-time using fluorescent dyes or target-specific probes, allowing quantification of initial target concentration based on the cycle threshold (Ct) value [8].

Table 2: Essential Reagents for qRT-PCR Biomarker Assay Validation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Assay | Quality Control Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Purification | QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit [8] | Isolation of high-quality RNA/DNA from specimens | Yield, purity (A260/280 ratio), integrity (RIN) |

| Reverse Transcription | AgPath-ID one-step RT-PCR reagents [8] | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates | Efficiency, inhibition testing |

| Amplification Master Mix | Applied Biosystems reagents [8] | Provides enzymes, dNTPs, buffers for PCR | Lot-to-lot consistency, reaction efficiency |

| Sequence-Specific Primers | WHO-recommended SARS-CoV-2 primers [8] | Target-specific amplification | Specificity testing, primer-dimer formation |

| Fluorescent Probes | TaqMan probes with ROX reference [8] | Sequence-specific detection, normalization | Probe stability, fluorescence quenching |

| Reference Genes | GAPDH, ACTB, HPRT1 [2] | RNA quality and loading control | Stable expression across sample types |

Digital PCR (dPCR) for Enhanced Sensitivity

Digital PCR represents a significant advancement for detecting rare mutations and analyzing liquid biopsies. dPCR works by partitioning a PCR mixture into thousands of individual reactions, so that each partition contains 0, 1, or a few nucleic acid targets according to a Poisson distribution [4]. Following PCR amplification, the fraction of positive partitions is used to compute the absolute target concentration without need for calibration curves [4].

The BEAMing (Beads, Emulsion, Amplification, and Magnetics) technology, developed by Vogelstein et al., simplified compartmentalization by utilizing water-in-oil droplets to parallelize PCR [4]. This method involves encapsulating individual DNA molecules with magnetic beads coated with primers, permitting PCR amplification within the droplet. Modern dPCR platforms include droplet-based systems (ddPCR) and microchamber-based approaches (QIAcuity, QuantStudio, Digital LightCycler) [4].

dPCR offers particular advantages for liquid biopsy applications, including exceptional sensitivity for detecting rare mutations, absolute quantification without standard curves, and high precision despite low input DNA quantities [4]. These characteristics make it invaluable for monitoring treatment response, detecting minimal residual disease, and analyzing samples with limited tumor DNA content.

DNA Methylation Analysis Techniques

DNA methylation biomarkers are particularly promising for liquid biopsy applications due to their stability, cancer-specific patterns, and early emergence in tumorigenesis [3]. Various methods exist for methylation analysis, each with distinct advantages:

- Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) and reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) provide broad methylome coverage through bisulfite-based chemical conversion [3]

- Enzymatic methyl-sequencing (EM-seq) and emerging third-generation sequencing technologies offer comprehensive profiling without chemical conversion, thereby better preserving DNA integrity [3]

- Targeted methods, including quantitative MSP and digital PCR assays, enable highly sensitive, locus-specific analysis ideal for clinical validation studies [3]

The inherent stability of methylated DNA fragments within the cell-free DNA pool, due to nucleosome interactions that protect them from nuclease degradation, makes them particularly suitable for liquid biopsy applications where sample integrity may be variable [3].

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Validation

Protocol 1: qRT-PCR Assay Validation for RNA Biomarkers

This protocol outlines the validation of a qRT-PCR assay for detecting RNA biomarkers in clinical samples, based on consensus guidelines [2].

Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction

- Sample Collection: Collect samples (blood, tissue, etc.) in appropriate stabilization buffers to preserve RNA integrity. For blood samples, use PAXgene Blood RNA tubes for immediate stabilization.

- RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA using silica-membrane based purification kits (e.g., QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit). Include DNase treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- Quality Assessment: Determine RNA concentration and purity by spectrophotometry (A260/280 ratio ~2.0). Assess RNA integrity using automated electrophoresis (RIN >7 for high-quality samples).

Reverse Transcription

- cDNA Synthesis: Use 100-500 ng total RNA in a 20 μL reaction with reverse transcriptase, random hexamers, and dNTPs. Include no-reverse transcription controls (NRT) to detect genomic DNA contamination.

- Reaction Conditions: Incubate at 25°C for 10 min (primer annealing), 50°C for 30 min (reverse transcription), 85°C for 5 min (enzyme inactivation).

qPCR Assay Validation

- Primer/Probe Design: Design primers and TaqMan probes using bioinformatics tools. Ensure amplicons span exon-exon junctions to avoid genomic DNA amplification.

- Standard Curve Preparation: Create a 5-point, 10-fold serial dilution of synthetic oligonucleotide standards or validated positive control material.

- PCR Amplification: Perform reactions in triplicate using 2X TaqMan Master Mix, primers, probe, and cDNA template. Use the following cycling conditions: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min.

- Validation Parameters:

- Linearity: Assess through standard curve with R² > 0.98

- Amplification Efficiency: Calculate from slope of standard curve (90-110%)

- Limit of Detection (LOD): Determine as the lowest concentration detected in 95% of replicates

- Precision: Evaluate intra-assay and inter-assay CV (<5%)

Protocol 2: DNA Methylation Analysis via Bisulfite Conversion

This protocol describes the detection of DNA methylation biomarkers through bisulfite conversion and qPCR analysis.

Bisulfite Conversion

- DNA Treatment: Treat 500 ng genomic DNA with sodium bisulfite using commercial kits (e.g., EZ DNA Methylation Kit). This converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged.

- Conversion Conditions: Denature DNA (95°C, 30 sec), incubate with conversion reagent (50°C, 12-16 hours), desalt, and desulfonate (room temperature, 15 min).

- Purification: Purify converted DNA using column-based purification and elute in 20 μL elution buffer.

Methylation-Specific PCR

- Primer Design: Design two primer sets—one specific for methylated sequences (binding to CpG-containing sequences after conversion) and one for unmethylated sequences (binding to TpG-containing sequences after conversion).

- PCR Amplification: Set up separate reactions for methylated and unmethylated assays using hot-start DNA polymerase. Include positive controls (fully methylated DNA) and negative controls (unmethylated DNA).

- qPCR Conditions: 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, specific annealing temperature (optimized for each primer set) for 30 sec, and 72°C for 30 sec.

- Data Analysis: Calculate methylation percentage using the ΔΔCt method or standard curve approach with methylated standards.

Protocol 3: Liquid Biopsy Analysis Using dPCR

This protocol outlines the detection of rare mutations in cell-free DNA from plasma samples using dPCR.

Plasma Processing and DNA Extraction

- Blood Collection: Collect blood in EDTA or Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT tubes. Process within 4 hours of collection.

- Plasma Separation: Centrifuge at 800-1600 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Transfer supernatant to a fresh tube and centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 10 min to remove residual cells.

- cfDNA Extraction: Extract cell-free DNA using silica-membrane kits (e.g., QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit). Elute in 20-50 μL elution buffer.

Droplet Digital PCR

- Reaction Setup: Prepare 20 μL reaction mixture containing ddPCR Supermix, target-specific primers/FAM probe, reference primers/HEX probe, and 5-10 μL cfDNA.

- Droplet Generation: Generate droplets using automated droplet generator according to manufacturer's instructions. Typically, 20,000 droplets per sample are generated.

- PCR Amplification: Transfer droplets to 96-well plate and amplify using the following conditions: 95°C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec and 60°C for 1 min, 98°C for 10 min (enzyme deactivation).

- Droplet Reading: Analyze droplets using droplet reader that measures fluorescence in each droplet.

- Data Analysis: Use Poisson statistics to calculate absolute concentration of mutant and wild-type alleles. Report mutant allele frequency as percentage.

Visualizing Biomarker Workflows and Signaling Pathways

Biomarker Development and Validation Workflow

Biomarker Development Pipeline This diagram illustrates the sequential phases from biomarker discovery through clinical implementation, highlighting key transition points requiring rigorous validation.

Predictive Biomarker Signaling Network

Biomarker Signaling Context This network diagram illustrates how predictive biomarkers (blue diamond) function within signaling pathways and relate to molecular drug targets (red octagon).

Clinical Implementation Considerations

Regulatory and Reimbursement Framework

The implementation of biomarker tests in clinical practice requires careful consideration of regulatory and reimbursement frameworks. According to Carelon Medical Benefits Management guidelines, somatic genomic testing is considered medically necessary when several criteria are met [5]:

- The test has established analytical and clinical validity (FDA-approved when available) and is performed in a certified laboratory

- The test has established clinical utility such that results will meaningfully impact clinical management

- There are biomarker-linked therapies approved by the FDA for the specific cancer scenario

- Clinical decision-making incorporates the known impact of genomic alterations on protein function and published efficacy data

For tissue-agnostic testing in metastatic or advanced solid tumors, multi-gene panel testing is medically necessary when specific criteria are satisfied, including the presence of FDA-approved genomic biomarker-linked therapies and lack of satisfactory standard therapies [5]. Approved tissue-agnostic biomarkers include mismatch repair deficiency (dMMR), microsatellite instability (MSI), tumor mutational burden (TMB ≥10 mutations/megabase), and NTRK/RET fusions [5].

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite promising advances, several challenges remain in precision oncology implementation. Currently, only a minority of patients benefit from genomics-guided precision cancer medicine, as many tumors lack actionable mutations and treatment resistance remains common [9]. There is a concerning overemphasis on genomic biomarkers at the expense of other biomarker types, including proteomic, pharmacodynamic, and microenvironmental factors [9].

The field must also address semantic challenges—the distinction between "precision cancer medicine" (more accurately described as "stratified medicine" at present) and true "personalized cancer medicine" which would integrate multiple biomarker layers for truly individualized treatment selection [9]. Future development should incorporate additional biomarker layers, including pharmacokinetics, pharmacogenomics, imaging, histopathology, nutrition, comorbidity, and concomitant medications [9].

Clinical trial design must evolve beyond tumor-agnostic, single-drug approaches to include appropriate controls and more selective patient recruitment based on comprehensive biology. While synthetic controls and real-world data offer promising alternatives, some form of randomized trial design remains necessary to definitively establish clinical benefit [9].

The validation and implementation of predictive and prognostic biomarkers represent a cornerstone of precision oncology. PCR-based methodologies, from qRT-PCR to digital PCR, provide robust platforms for biomarker analysis with the sensitivity and specificity required for clinical application. Successful implementation requires rigorous analytical validation, demonstration of clinical utility, and navigation of regulatory frameworks. Future progress will depend on expanding beyond purely genomic biomarkers to integrate multiple data types, improving clinical trial designs to establish true clinical benefit, and ensuring equitable access to biomarker-guided therapies across diverse patient populations. As these advancements unfold, PCR-based biomarker validation will continue to play an essential role in translating molecular discoveries into improved cancer care.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) remains a cornerstone technology in the molecular diagnostics pipeline, playing a critical role in the development and validation of cancer biomarkers. Its exceptional sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility make it indispensable for translating potential biomarker candidates from discovery platforms into clinically applicable assays. In cancer research, qPCR serves as a vital bridge between high-throughput discovery methods like next-generation sequencing (NGS) and routine clinical implementation, enabling researchers to verify biomarker candidates with precise, quantitative measurements across patient cohorts.

The utility of qPCR spans the entire biomarker development workflow. As noted by Dr. Christopher Mason of Weill Cornell Medicine, "We use RNA sequencing extensively... however, qPCR is the most sensitive method we use to validate gene fusion events, expression changes, or isoform variations. I still consider qPCR the high bar for validation" [10]. This endorsement underscores qPCR's established position as the gold standard for confirmation of biomarker candidates identified through discovery-phase omics technologies. The technique's robustness, relatively low cost, and compatibility with various sample types—from tissue specimens to liquid biopsy sources like blood and urine—make it ideally suited for the rigorous validation requirements of clinical translation.

qPCR Across the Biomarker Development Workflow

The Biomarker Development Pipeline

The journey of a biomarker from initial discovery to clinical application follows a structured pathway with distinct stages, each with specific technical requirements and validation milestones. qPCR contributes uniquely to each phase of this pipeline, providing increasing levels of evidence for biomarker analytical and clinical validity.

Table 1: qPCR Applications Across Biomarker Development Stages

| Development Stage | Primary qPCR Application | Key Technical Considerations | Output Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery & Candidate Identification | Verification of candidates from NGS, microarrays, or bioinformatic analyses | High-throughput capability, multi-gene panels, preliminary assay design | Fold-change expression, p-values, differential expression confirmation |

| Assay Development & Optimization | Primer/probe design, reaction condition optimization, controls establishment | Specificity, efficiency, dynamic range, reproducibility | Amplification efficiency, R² values, CV%, LOD, LOQ |

| Analytical Validation | Establishing assay performance characteristics | Sensitivity, specificity, precision, robustness across operators/instruments | AUC, sensitivity %, specificity %, CV% |

| Clinical Validation | Testing in well-defined clinical cohorts | Blinded analysis, standardized protocols, multi-site reproducibility | Clinical sensitivity/specificity, PPV, NPV, odds ratios |

| Clinical Implementation | Deployment in clinical laboratory settings | SOPs, quality control, regulatory compliance | Turnaround time, success rate, clinical utility metrics |

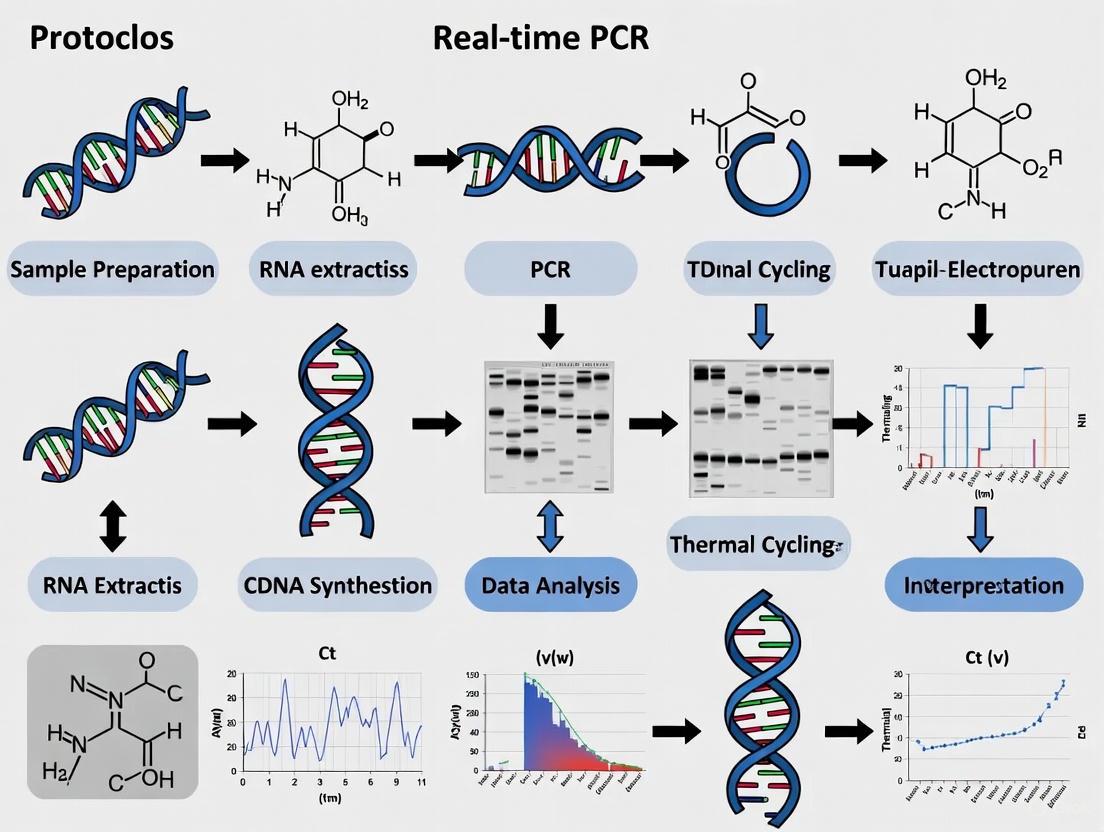

The following workflow diagram illustrates how qPCR integrates into the complete biomarker development pipeline:

Candidate Verification Following Discovery

The initial stage of biomarker development involves identifying potential candidates through high-throughput discovery approaches. Whole transcriptome analysis through RNA sequencing and bioinformatic mining of public datasets represent powerful discovery tools. For example, one study leveraged The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) databases to identify mRNA biomarkers for colorectal cancer, subsequently validating the top candidates using qPCR [11]. This pattern of using qPCR to verify discoveries is consistent across biomarker types, including DNA methylation markers and various RNA species.

qPCR excels in this verification role due to its quantitative nature, which provides precise measurement of expression differences between case and control samples. When research identified a novel five-gene transcriptomic signature for pancreatic cancer through machine learning analysis of 14 public datasets, qPCR validation in peripheral blood samples confirmed the diagnostic potential with an AUC of 0.83 [12]. This demonstrates qPCR's crucial function in confirming that computationally identified biomarkers show measurable differential expression in clinically relevant samples.

qPCR Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Validation

Standard qPCR Protocol for mRNA Biomarker Validation

This protocol details the validation of mRNA biomarkers from peripheral blood samples, adapted from established methodologies in recent literature [12].

Sample Collection and RNA Extraction

- Collect peripheral blood (5 mL) in EDTA tubes under standardized conditions (early morning, fasting participants)

- Process samples within 2 hours of collection to preserve RNA integrity

- Extract total RNA using TRIzol LS reagent following manufacturer's protocol

- Assess RNA quality and quantity using NanoDrop spectrophotometer and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer

- Quality Threshold: Use only samples with RNA integrity number (RIN) >7 for subsequent analysis

cDNA Synthesis

- Use 1 μg of total RNA as input for first-strand cDNA synthesis

- Employ SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System with oligo(dT) primers

- Incubate at 65°C for 5 minutes, then place on ice for 1 minute

- Add reaction mix (5X First-Strand Buffer, 0.1 M DTT, RNaseOUT Recombinant RNase Inhibitor, SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase)

- Incubate at 50°C for 50 minutes, followed by enzyme inactivation at 85°C for 5 minutes

- Dilute cDNA 1:5 with nuclease-free water before qPCR analysis

Quantitative PCR Setup

- Prepare reactions using SYBR Green Master Mix on 96-well or 384-well plates

- Use primer concentrations of 200-400 nM each in final reaction volume of 10-20 μL

- Include triplicate technical replicates for each sample

- Always include no-template controls (NTC) and positive controls

- Thermal Cycling Conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes

- 40 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute

- Melt curve analysis: 60°C to 95°C with 0.5°C increments

Data Analysis

- Determine cycle threshold (Ct) values using instrument software

- Normalize target gene expression to reference genes (GAPDH, ACTB, or panel of housekeeping genes)

- Calculate relative expression using the 2-ΔΔCt method

- Perform statistical analysis using appropriate tests (t-tests, ANOVA, ROC analysis)

Advanced Protocol: Folate Ligand-Targeted qPCR for Circulating Tumor Cell Detection

This specialized protocol demonstrates the adaptation of qPCR for detecting folate receptor-positive circulating tumor cells (FR+ CTCs) in gastric cancer, showcasing the technology's versatility [13].

Folate-Oligonucleotide Conjugate Design

- Design a 30-nucleotide sequence with 5' folate moiety conjugation

- Incorporate iSp9 (Triethylene glycol PEG) spacer between folate ligand and oligonucleotide

- Add phosphorothioate bond at 3' end for nuclease resistance

- Purify conjugated probe using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

Stem-Loop Primer Design

- Design stem-loop RT primer with:

- 5' linear sequence portion (overhung)

- Double-stranded stem region with complementary base pairing

- Single-stranded loop region at 3' end for specific target recognition

- Optimize using RNAfold web server to achieve Gibbs free energy (ΔG) of approximately -23.40 kcal/mol

- Validate through in silico simulations for hybridization capability

CTC Enrichment and Detection

- Enrich CTCs from blood samples by negative depletion of leukocytes

- Label enriched CTCs with folate-oligonucleotide conjugate

- Perform two-step process:

- Step 1: Complementary DNA synthesis when folate-oligonucleotide binds to overhung of stem-loop primer

- Step 2: PCR amplification using forward primer targeting folate oligo and universal reverse primer targeting stem-loop primer

- Optimize annealing temperature for stem-loop primer (40-45°C established as optimal)

Assay Performance Validation

- Establish standard curve using spiked HeLa cells in healthy donor blood

- Validate amplification efficiency (104% achieved in optimized assay)

- Confirm linearity (R² = 0.9970) between Ct values and logarithmic CTC concentrations

- Verify specificity through melt curve analysis and gel electrophoresis

Quantitative Performance Data

qPCR Performance in Validation Studies

Table 2: qPCR Performance Metrics Across Cancer Biomarker Studies

| Cancer Type | Biomarker Class | Sample Type | qPCR Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic Cancer | 5-gene mRNA signature (LAMC2, TSPAN1, MYO1E, MYOF, SULF1) | Peripheral Blood | AUC: 0.83 (Validation cohort) | [12] |

| Gastric Cancer | Folate receptor-positive CTCs | Blood | Linearity: R² = 0.9970, Efficiency: 104% | [13] |

| Colorectal Cancer | 20-gene mRNA panel | Stool | AUC: 0.94 (CRC), 0.83 (Advanced Adenoma) | [11] |

| Various Cancers | Gene fusions, expression changes | Tissue, Blood | "High bar for validation" vs. NGS | [10] |

| Various Cancers | DNA methylation markers | Liquid Biopsies | High sensitivity after bisulfite conversion | [3] |

Comparison with Alternative Technologies

Table 3: qPCR vs. Other Biomarker Validation Technologies

| Parameter | qPCR | Digital PCR | RNA Sequencing | Microarrays |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High (detects <10 copies) | Very High (single molecule) | Moderate | Moderate |

| Throughput | Medium (96-384 wells) | Low-Medium | High | High |

| Cost per Sample | Low | Medium | High | Medium |

| Quantitative Accuracy | High | Very High | Moderate | Moderate |

| Multiplexing Capability | Low-Medium | Low | High | High |

| Ease of Implementation | High | Medium | Low | Medium |

| Best Application | Targeted validation, clinical assays | Rare target detection, absolute quantification | Discovery, novel biomarker identification | Large-scale screening |

The choice between qPCR and digital PCR depends on the specific application requirements. According to Dr. Mason, "We've used both qPCR and digital PCR for MRD. The choice depends on validated panels and known targets. qPCR is favored for its long-standing reliability and general robustness while digital PCR is effective for detecting rarer targets" [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Biomarker Validation

| Reagent Category | Specific Product Examples | Function & Importance | Quality Control Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | TRIzol LS, column-based kits | Maintain RNA integrity, remove inhibitors | RNA Integrity Number (RIN) >7, A260/A280 ~2.0 |

| Reverse Transcriptase Kits | SuperScript III, High-Capacity cDNA | Efficient cDNA synthesis, minimal bias | Efficiency >90%, high yield |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR Green, TaqMan assays | Sensitive detection, robust amplification | Efficiency: 90-110%, R² >0.98 |

| Primers/Probes | Custom-designed, validated sequences | Target-specific amplification | Specificity, no primer-dimer |

| Reference Genes | GAPDH, ACTB, 18S rRNA, PPIA | Normalization, data standardization | Stable expression across samples |

| Quality Control Standards | Synthetic oligonucleotides, reference RNA | Inter-assay comparison, QC monitoring | Consistent Ct values, low CV% |

Implementation in Clinical Workflows

qPCR's transition from research tool to clinical application requires careful consideration of several factors. The technique has demonstrated particular utility in minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring, where its sensitivity enables tracking of mutation levels in patient blood after therapy. As Dr. Mason notes, "qPCR, with its high sensitivity, will fundamentally change how we look at cancer. We will not just treat your cancer; we'll monitor it, look for variations of it, and search for new mutations that arise" [10].

The implementation of qPCR-based tests in clinical settings must address several critical aspects:

Standardization and Reproducibility

- Development of standardized operating procedures (SOPs)

- Implementation of quality control measures across multiple sites

- Establishment of reference materials and calibration standards

- Validation of assay performance in intended-use populations

Regulatory Considerations

- Analytical validation following regulatory guidelines (CLIA, FDA)

- Demonstration of clinical validity and utility

- Documentation of assay reproducibility and reliability

- Establishment of appropriate cut-offs for clinical decision-making

Integration with Clinical Practice

- Determination of clinical scenarios where the test provides actionable information

- Establishment of turnaround times compatible with clinical needs

- Education of clinicians on test interpretation and limitations

- Development of reporting formats that facilitate clinical decision-making

Workflow Visualization: qPCR Experimental Process

The following diagram illustrates the complete qPCR experimental workflow for biomarker validation, from sample collection to data analysis:

qPCR maintains a fundamental position in the biomarker development pipeline, serving as an essential technology for translating potential biomarker candidates from discovery to clinical application. Its robust quantitative capabilities, sensitivity, and reproducibility make it ideally suited for the rigorous validation requirements of clinical translation. As biomarker research evolves toward liquid biopsy applications and multi-analyte panels, qPCR methodologies continue to adapt, with innovations such as ligand-targeted approaches expanding its utility. While emerging technologies like digital PCR and next-generation sequencing offer complementary capabilities, qPCR remains the workhorse for targeted biomarker validation, striking an optimal balance between performance, practicality, and cost-effectiveness for both research and clinical implementation.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) is a foundational tool in molecular biology and oncology research, providing the sensitivity, specificity, and broad quantification range necessary for detecting and validating cancer biomarkers [14] [15]. The reliability of qPCR results depends significantly on the choice of detection chemistry, which fundamentally influences assay specificity, sensitivity, and applicability to different research scenarios. In the context of cancer biomarker validation, selecting the appropriate chemistry is critical for accurately identifying genomic alterations, quantifying gene expression changes, and detecting low-frequency mutations in challenging sample types like liquid biopsies [15] [16].

Two primary detection chemistries dominate the qPCR landscape: the DNA-binding dye SYBR Green and sequence-specific fluorogenic probes, most commonly represented by TaqMan chemistry [17]. SYBR Green provides a flexible and cost-effective detection system that binds indiscriminately to double-stranded DNA, while probe-based methods utilize target-specific oligonucleotides with reporter and quencher molecules for highly specific detection [17] [18]. Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations that researchers must consider when designing experiments for cancer biomarker validation, particularly when working with precious clinical samples where material may be limited and false positives could lead to incorrect conclusions.

This application note provides a comprehensive comparison of these essential qPCR chemistries, detailing their mechanisms, optimal applications, and detailed protocols tailored specifically for cancer research. By understanding the fundamental principles and practical considerations of each system, researchers can make informed decisions that enhance the reliability and translational potential of their biomarker validation workflows.

Core Principles and Mechanisms

SYBR Green Chemistry

SYBR Green-based detection utilizes a fluorescent dye that binds non-specifically to the minor groove of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) [17] [18]. The mechanism relies on the dramatic fluorescence enhancement that occurs when the dye intercalates with dsDNA—typically a 20- to 100-fold increase in fluorescence compared to the unbound state [18]. This property allows researchers to monitor PCR product accumulation in real time without the need for target-specific probes.

The step-by-step process begins with the free SYBR Green dye present in the reaction mixture exhibiting minimal fluorescence due to its unbound state. As amplification progresses during thermal cycling, the DNA polymerase synthesizes new DNA strands, creating dsDNA products. SYBR Green molecules then bind to these newly formed dsDNA amplicons, resulting in a significant increase in fluorescence intensity that is directly proportional to the amount of PCR product generated [17]. This fluorescence is detected by the qPCR instrument at the end of each amplification cycle, providing the characteristic amplification plot.

A critical requirement for SYBR Green assays is post-amplification melt curve analysis to verify reaction specificity [17]. Since the dye binds to any dsDNA present in the reaction, including non-specific products and primer-dimers, the melt curve analysis serves as an essential quality control step. This analysis involves gradually increasing the temperature after amplification while monitoring fluorescence, resulting in a characteristic dissociation curve where specific amplicons display a distinct melting temperature (Tm) based on their length, GC content, and sequence composition. The presence of a single peak in the melt curve typically indicates a specific amplification product, while multiple peaks suggest non-specific amplification or primer-dimer formation that could compromise quantification accuracy, particularly in cancer biomarker applications where false positives must be avoided.

Probe-Based Chemistry (TaqMan)

Probe-based qPCR chemistry employs target-specific oligonucleotide probes labeled with fluorescent reporter and quencher molecules, with TaqMan being the most widely used format [17]. These probes provide significantly higher specificity than SYBR Green because fluorescence generation requires not only successful amplification but also specific hybridization between the probe and its complementary target sequence [17] [18].

The fundamental mechanism relies on Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) and the 5'→3' exonuclease activity of Taq DNA polymerase [17] [18]. A typical TaqMan probe consists of an oligonucleotide complementary to the target sequence, with a fluorescent reporter dye attached to the 5' end and a quencher molecule at the 3' end. When the probe is intact, the proximity of the quencher to the reporter dye prevents fluorescence emission through FRET. During the amplification process, when the probe is bound to its target sequence, the advancing Taq DNA polymerase cleaves the probe due to its inherent 5'→3' exonuclease activity. This cleavage separates the reporter dye from the quencher, allowing the reporter to emit fluorescence that is detected by the qPCR instrument [18].

The process occurs during each amplification cycle: first, the forward and reverse primers anneal to their complementary sequences on the denatured DNA template. Next, the TaqMan probe specifically hybridizes to its target sequence between the primer binding sites. As Taq DNA polymerase extends the primer, it eventually reaches and cleaves the bound probe, releasing the reporter dye and generating a fluorescent signal. With each subsequent cycle, additional reporter dye molecules are cleaved from their probes, resulting in a cumulative increase in fluorescence intensity directly proportional to the amount of amplified target [17]. This mechanism ensures that fluorescence is generated only when the specific target sequence is amplified, eliminating signals from non-specific amplification products and providing superior specificity for discriminating closely related sequences—a critical advantage when detecting cancer-associated mutations or single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs).

Advanced probe variants include TaqMan MGB (Minor Groove Binder) probes, which incorporate a minor groove binder molecule at the 3' end that increases the probe's melting temperature (Tm) [17]. This allows the use of shorter probes while maintaining high specificity, particularly beneficial for discriminating single-base differences in SNP genotyping and mutation detection assays common in cancer biomarker research [17].

Comparative Analysis: Probe-Based vs. SYBR Green Detection

Selecting the appropriate qPCR chemistry requires careful consideration of multiple performance parameters, cost factors, and application requirements. The following comparative analysis provides a structured framework for decision-making in cancer biomarker validation research.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of SYBR Green vs. Probe-Based qPCR Chemistry

| Parameter | SYBR Green | Probe-Based (TaqMan) |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Lower* (Depends on primer specificity and melt curve analysis) | Higher (Requires specific hybridization between probe and target) [17] |

| Sensitivity | Variable* (1-10 copies, depends on template quality and primer design) | High (Consistently detects 1-10 copies) [17] |

| Reproducibility | Medium* (More susceptible to reaction condition variations) | High (Superior consistency across replicates) [17] |

| Multiplexing Capability | No (Single-plex only) | Yes (Simultaneous detection of multiple targets using different reporter dyes) [17] |

| Assay Design & Optimization | Requires extensive primer validation and optimization | Predesigned assays available; minimal optimization required [17] |

| Cost Considerations | Lower setup cost (Only primers required) | Higher setup cost (Probes add significant expense) [17] |

| Primary Applications | Mycoplasma detection, NGS library quantification, telomere length analysis, gene expression with limited targets [17] | Gene expression analysis, miRNA quantification, pathogen detection, copy number variation, SNP genotyping, clinical research [17] |

*Performance highly dependent on template quality and primer design optimization [17].

The specificity advantage of probe-based chemistry stems from its requirement for three specific binding events (forward primer, reverse primer, and probe) compared to only two with SYBR Green, significantly reducing the risk of detecting non-specific amplification products [17]. This is particularly valuable when working with complex samples or closely related gene families. For multiplexing applications, probe-based systems support detection of multiple targets in a single reaction through use of differentially labeled probes, while SYBR Green is limited to single-target detection [17].

From a practical implementation perspective, SYBR Green offers advantages in flexibility and initial cost, as it can be applied to any gene target with appropriately designed primers and requires only standard primer synthesis. Probe-based assays, while more expensive initially, provide predesigned assay options and require less optimization time, potentially offsetting their higher upfront costs in high-throughput settings [17]. For cancer biomarker validation where reproducibility across experiments and laboratories is essential, the superior consistency of probe-based detection often justifies the additional investment.

Applications in Cancer Biomarker Research

SNP Genotyping and Mutation Detection

Probe-based qPCR excels in single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) genotyping and mutation detection, crucial for identifying cancer-associated genetic variations [18]. The technology enables precise discrimination of single-base differences through allele-specific probes labeled with different fluorescent reporters. For example, a FAM-labeled probe can target the wild-type allele while a VIC-labeled probe targets the mutant allele, allowing simultaneous detection in a single reaction [18].

The assay relies on the principle that Taq DNA polymerase's 5'→3' exonuclease activity requires perfect complementarity at the 3' end of the probe. When a mismatch occurs between the probe and template DNA at the SNP position, hybridization is unstable, preventing probe cleavage and fluorescence emission [18]. This precise discrimination makes probe-based qPCR invaluable for profiling oncogenic mutations in genes like EGFR, KRAS, and BRAF, where treatment decisions depend on accurate mutation identification [15]. Multiplexed qPCR panels can simultaneously assess alterations in multiple clinically relevant genes, delivering results faster and using less input material than sequential testing approaches—a significant advantage when working with limited liquid biopsy samples [15].

Gene Expression Profiling

Both SYBR Green and probe-based chemistries are widely employed in gene expression analysis for cancer biomarker discovery, though with different considerations for assay robustness. Gene expression quantification typically follows the ΔΔCT method or the more efficiency-adjusted Pfaffl method, with normalization to appropriate reference genes [14].

Probe-based assays offer superior specificity for distinguishing between homologous genes or splice variants, which is particularly important when measuring expression of cancer-related gene families with high sequence similarity. The R package "rtpcr" provides comprehensive analysis capabilities for qPCR data, accommodating amplification efficiency values and supporting statistical analysis through t-tests, ANOVA, or ANCOVA depending on experimental design [14]. For clinical validation studies where reproducibility across multiple sites is essential, probe-based assays provide more consistent results due to their reduced susceptibility to reaction condition variations.

DNA Methylation Analysis

Epigenetic alterations, particularly DNA methylation changes, represent promising cancer biomarkers for early detection and prognosis. Probe-based qPCR enables targeted methylation analysis of specific CpG islands using bisulfite-converted DNA [18]. The process involves sodium bisulfite treatment, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged, followed by qPCR with primers and probes specifically designed to distinguish methylated from unmethylated sequences [18].

TaqMan probes in methylation assays are designed to complement either the methylated or unmethylated sequence after bisulfite conversion. When the probe perfectly matches the methylated allele, it binds efficiently and generates fluorescence during amplification. Conversely, mismatches with the unconverted unmethylated allele prevent stable hybridization and fluorescence emission [18]. This targeted approach provides a quantitative alternative to genome-wide methylation analysis for validating specific epigenetic biomarkers identified through discovery-phase experiments.

Copy Number Variation (CNA) Analysis

Both chemistries can be applied to copy number variation analysis, which is increasingly recognized as clinically significant in oncology. A 2025 comparative study of real-time PCR and nCounter NanoString techniques for validating copy number alterations in oral cancer demonstrated qPCR's robustness for detecting genomic biomarkers [19]. The study analyzed 24 genes in 119 oral cancer samples and found moderate to substantial agreement between the techniques, with Spearman's rank correlation ranging from r = 0.188 to 0.517 [19].

For CNA analysis, the relative quantification method is typically employed, comparing target gene CT values to a reference gene with known copy number in a diploid genome. Probe-based assays generally provide more reproducible results for copy number determination due to their reduced variability and higher specificity, particularly when analyzing formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples where DNA quality may be compromised.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: SYBR Green-Based Gene Expression Analysis

Principle: This protocol utilizes SYBR Green I dye to detect accumulated double-stranded DNA during PCR amplification, with post-amplification melt curve analysis to verify specificity [17].

Reagents and Materials:

- SYBR Green Master Mix (2× concentration)

- Forward and reverse primers (10 μM working concentration)

- RNA-free DNase/RNase-free water

- cDNA template (diluted to appropriate concentration)

- 96-well or 384-well optical reaction plates

- Optical adhesive seals

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup:

- Prepare master mix on ice: 10 μL SYBR Green Master Mix (2×), 1 μL forward primer (10 μM), 1 μL reverse primer (10 μM), 4 μL nuclease-free water per reaction.

- Aliquot 16 μL master mix into each well of optical plate.

- Add 4 μL cDNA template (20-100 ng total) to each well for final reaction volume of 20 μL.

- Include no-template controls (NTC) replacing cDNA with nuclease-free water.

qPCR Program:

- Stage 1: Enzyme activation - 95°C for 2 minutes (1 cycle)

- Stage 2: Amplification - 95°C for 15 seconds (denaturation) followed by 60°C for 1 minute (annealing/extension) for 40 cycles

- Stage 3: Melt curve analysis - 95°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 1 minute, then gradual increase to 95°C with continuous fluorescence measurement (0.3°C increments)

Data Analysis:

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Multiple peaks in melt curve indicate primer-dimer formation or non-specific amplification—redesign primers or optimize annealing temperature.

- High NTC signals suggest contamination—prepare fresh reagents and use dedicated workspace.

- Poor efficiency (outside 90-110%) requires primer revalidation or concentration optimization.

Protocol 2: Probe-Based SNP Genotyping

Principle: This protocol uses allele-specific TaqMan probes with different fluorescent reporters to discriminate single nucleotide polymorphisms through differential probe hybridization and cleavage [18].

Reagents and Materials:

- TaqMan Genotyping Master Mix (2×)

- TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assay (20×) containing sequence-specific forward and reverse primers plus two allele-specific probes

- DNA template (5-20 ng/μL)

- Nuclease-free water

- Optical reaction plates and seals

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup:

- Prepare master mix: 5 μL TaqMan Genotyping Master Mix (2×), 0.5 μL TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assay (20×), 2.5 μL nuclease-free water per reaction.

- Aliquot 8 μL master mix into each well.

- Add 2 μL DNA template (10-40 ng total) per well for 10 μL final volume.

- Include positive controls for both homozygous and heterozygous genotypes if available.

qPCR Program:

- Stage 1: Enzyme activation - 95°C for 10 minutes (1 cycle)

- Stage 2: Amplification - 95°C for 15 seconds followed by 60°C for 1 minute for 40-50 cycles

- Note: No melt curve analysis required for probe-based genotyping

Endpoint Genotyping Analysis:

- Use the allelic discrimination plot feature in qPCR analysis software.

- FAM and VIC fluorescence measurements at endpoint define three distinct clusters: homozygous allele 1, homozygous allele 2, and heterozygous.

- Manual threshold setting may be required for optimal cluster separation.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Poor cluster separation indicates suboptimal probe design or PCR efficiency—try TaqMan MGB probes for better discrimination [17].

- Failed reactions (no amplification) suggest poor DNA quality or inhibitor presence—purify DNA or dilute template.

- Atypical clustering patterns may indicate rare variants or tri-allelic SNPs—confirm by sequencing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for qPCR Cancer Biomarker Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SYBR Green Master Mix | Provides DNA polymerase, buffer, dNTPs, and SYBR Green dye for detection | Ideal for initial screening and expression analysis of multiple targets; requires melt curve analysis [17] |

| TaqMan Universal Master Mix | Optimized for probe-based assays; contains AmpliTaq Gold DNA Polymerase, buffers, dNTPs | Delivers robust performance across diverse sample types; compatible with various probe chemistries [17] |

| TaqMan MGB Probes | Minor Groove Binder probes with non-fluorescent quencher for enhanced specificity | Superior SNP discrimination; shorter probe length improves mismatch discrimination [17] |

| Inhibitor-Resistant Polymerases | Engineered enzymes tolerant to PCR inhibitors in clinical samples | Essential for direct analysis of blood, FFPE, and other complex matrices without extensive purification [15] |

| Ambient-Stable Master Mixes | Lyophilized or chemically stabilized ready-to-use formulations | Enables decentralized testing; reduces cold chain dependence for resource-limited settings [15] |

| Multiplex PCR Master Mix | Specialized formulation supporting simultaneous amplification of multiple targets | Required for multi-gene panels; minimizes competition between amplifications [15] |

| Reference Gene Assays | Validated control assays for normalization | Essential for reliable quantification; should be stable across experimental conditions [14] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantitative Analysis Methods

Accurate data analysis is paramount for reliable cancer biomarker validation. The two primary mathematical approaches for qPCR data analysis are the Livak (2^(-ΔΔCT)) and Pfaffl methods [14]. The Livak method assumes ideal amplification efficiency (100%) for both target and reference genes, while the Pfaffl method incorporates actual amplification efficiencies for more precise quantification, particularly when efficiencies differ from 100% [14].

The Pfaffl method calculates fold change using the formula: FC = [Etarget^(ΔCTtarget)] / [Eref^(ΔCTref)] Where E represents amplification efficiency (typically 1.8-2.0) and ΔCT is the difference in CT values between treatment and control groups [14].

For copy number variation analysis, the comparative CT method (ΔΔCT) is employed relative to a diploid reference gene, with the formula: Copy Number = 2 × 2^(-ΔΔCT)

Statistical analysis of qPCR data typically employs t-tests for two-group comparisons or ANOVA for multi-group experiments, with appropriate multiple testing corrections for high-dimensional biomarker panels [14]. The R package "rtpcr" provides comprehensive analysis capabilities, including calculation of standard errors and confidence intervals according to established methodologies [14].

Quality Control Considerations

Robust quality control measures are essential for reliable biomarker validation:

- Amplification Efficiency: Should fall within 90-110% (3.6 > slope > 3.1) for reliable quantification.

- Standard Curves: Required for absolute quantification; R² > 0.98 indicates linearity.

- Replicate Consistency: Technical replicates should show minimal variation (CT standard deviation < 0.3 cycles).

- Reference Gene Stability: Must be validated across experimental conditions using algorithms like geNorm or NormFinder.

- NTC Monitoring: Should show no amplification or significantly delayed amplification (CT values > 5 cycles than sample wells).

Automated analysis tools like Auto-qPCR can streamline data processing, providing standardized workflows for amplification efficiency calculation, normalization, and statistical analysis while minimizing manual intervention errors [20].

The selection between SYBR Green and probe-based qPCR chemistries represents a critical methodological decision in cancer biomarker validation research. SYBR Green offers flexibility and cost-effectiveness for applications with lower specificity demands, while probe-based systems provide superior specificity, reproducibility, and multiplexing capabilities essential for clinical translation.

In oncology applications, probe-based qPCR continues to demonstrate particular value for its ability to detect clinically actionable biomarkers at low concentrations, support broader mutational profiling, and deliver rapid results in time-sensitive clinical scenarios [15]. The technology's compatibility with standardized formats, automation-friendly workflows, and established regulatory frameworks further enhances its utility in both research and clinical settings.

As cancer diagnostics evolve toward earlier detection, molecular stratification, and personalized therapy, both chemistries will maintain important roles in the biomarker validation pipeline. Understanding their complementary strengths and limitations enables researchers to implement the most appropriate detection system for their specific application, ultimately advancing more effective cancer diagnostics and therapeutic monitoring tools.

Cancer biomarkers are biological molecules, genes, or characteristics that provide crucial information about the presence, behavior, and potential treatment of cancer. These biomarkers encompass a broad category that includes genes, gene mutations, proteins, or other substances that can be measured in blood, tumor tissue, or other body fluids [21]. They serve as objective indicators of the molecular characteristics of cancer, enabling early diagnosis, prognosis prediction, treatment selection, and monitoring of disease recurrence [22]. The evolution from traditional tumor markers to sophisticated molecular biomarkers represents a fundamental shift in oncology, moving away from one-size-fits-all treatments toward precision medicine approaches tailored to the individual molecular profile of each patient's cancer [21] [23].

The clinical utility of biomarkers spans the entire cancer care continuum, from risk assessment and early detection to monitoring treatment response and guiding survivorship care [23]. Biomarker testing can be used at many stages—diagnosis, treatment, monitoring response, and survivorship—making it a dynamic process essential throughout the patient journey [23]. Progress in improving cancer outcomes increasingly involves precision medicine, with biomarker testing serving as a critical gateway to accessing targeted therapies that can lead to improved survivorship and better quality of life [24].

Classes of Molecular Biomarkers

Genetic Biomarkers

Genetic biomarkers consist of specific mutations, rearrangements, or variations in the DNA sequence that drive oncogenesis or influence treatment response. These include somatic mutations acquired in tumor cells and germline mutations inherited through familial lines. Key examples include EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer, BRCA1/2 mutations in ovarian, breast, pancreatic, and prostate cancers, and the BCR-ABL fusion gene in leukemia and lymphomas [22] [21]. These biomarkers provide critical information for diagnosis, prognostication, treatment determination, and response monitoring [22].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized the detection of genetic biomarkers, allowing clinicians to sequence a tumor's DNA and identify targetable mutations [21]. As one oncology expert explained, "Checking the genetic signatures and profiling with next-generation sequencing tells you what type of mutations are present in the tumor. This is essential to determine what treatment options are unique to the tumor" [21]. This molecular profiling enables the matching of patients with precision therapies most likely to work for their specific disease, moving beyond the indiscriminate approach of traditional chemotherapy [21] [23].

Epigenetic Biomarkers

Epigenetic biomarkers involve modifications that regulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence, with DNA methylation being the most extensively studied. DNA methylation refers to the addition of a methyl group to the 5' position of cytosine, typically at CpG dinucleotides, resulting in 5-methylcytosine [3]. In cancer, DNA methylation patterns are frequently altered, with tumors typically displaying both genome-wide hypomethylation and hypermethylation of CpG-rich gene promoters [3]. Promoter hypermethylation of key tumor suppressor genes is commonly associated with gene silencing, while global hypomethylation can induce chromosomal instability, collectively disrupting normal growth pathways and driving malignant transformation [3].

The clinical appeal of DNA methylation biomarkers stems from several unique properties: these alterations often emerge early in tumorigenesis and remain stable throughout tumor evolution, making them ideal for early detection [3]. The inherent stability of DNA methylation patterns and the relative enrichment of methylated DNA fragments within the cell-free DNA pool also enhance their detectability in liquid biopsies [3]. Research presented at the Molecular Analysis for Precision Oncology Congress 2025 highlights how epigenetic changes represent critical events in cancer initiation, and molecular interrogation techniques combined with machine learning can harness this epigenetic information to enhance diagnosis and patient care [25].

Transcriptomic Biomarkers

Transcriptomic biomarkers encompass changes in RNA expression patterns, alternative splicing events, and non-coding RNAs that reflect the functional state of cancer cells. These biomarkers provide a dynamic view of gene expression activity, capturing the molecular mechanisms driving cancer progression. Recent advances in transcriptomic analysis have revealed robust cancer- and subtype-specific alternative splicing biomarkers that serve as critical regulators in cancer progression [26].

In lung cancer, for example, comprehensive transcriptomic analysis has identified alternative splicing biomarkers that are consistently effective in both tissue samples and cancer cell lines [26]. Regulatory network analysis has revealed RNA-binding proteins such as QKI and SR proteins as key splicing factors, with QKI modulating the splicing of PLEKHA1 exon 15 and SRSF1 regulating the splicing of MKNK2 exon 14 [26]. These splicing events represent potential therapeutic targets and diagnostic tools, providing valuable insights into the key alternative splicing events and their regulatory mechanisms in cancer [26].

Table 1: Major Biomarker Classes and Their Characteristics

| Biomarker Class | Molecular Basis | Key Technologies for Detection | Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic | DNA sequence variations (mutations, rearrangements, copy number changes) | Next-generation sequencing, PCR, FISH | Diagnosis, prognosis, treatment selection, monitoring |

| Epigenetic | DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin remodeling | Bisulfite sequencing, methylation arrays, EM-seq | Early detection, prognosis, monitoring, screening |

| Transcriptomic | Gene expression patterns, alternative splicing, non-coding RNAs | RNA sequencing, microarrays, qRT-PCR | Subtyping, prognosis, therapeutic targeting |

Current Applications in Cancer Management

Diagnostic and Early Detection Applications

The application of biomarkers for early cancer detection represents one of the most promising areas in oncology, with the potential to significantly improve patient outcomes by enabling intervention when treatments are most effective. Early detection aims to identify carcinogenic changes at the earliest stage, when therapeutic intervention can result in improved survival rates and reduced morbidity [22]. Studies have demonstrated that early detection leads to a median overall survival of 38 months compared to 14 months with delayed diagnosis, while also improving quality of life scores from 55 to 75 and reducing severe treatment-related side effects from 18 to 45% [22].

Liquid biopsies have emerged as a particularly promising approach for early detection, offering a minimally invasive source for detecting a broad range of cancer biomarkers [3] [22]. These tests analyze tumor material shed into body fluids, including circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), circulating tumor cells (CTCs), and exosomes [3]. Compared to tissue biopsies, liquid biopsies reflect the entire tumor burden and molecular cancer heterogeneity, are less invasive, and enable repeated sampling for monitoring treatment response and cancer progression [3]. DNA methylation biomarkers in liquid biopsies offer special advantages for early detection because methylation alterations often emerge early in tumorigenesis and remain stable throughout tumor evolution [3].

Prognostic and Predictive Applications

Beyond detection, biomarkers play crucial roles in predicting disease course and treatment response. Prognostic biomarkers provide information about the likely natural history of the cancer, while predictive biomarkers help identify patients who are most likely to respond to specific treatments. For example, in colorectal cancer, a robust five-gene prognostic signature (TIMP1, PCOLCE2, MEIS2, HDC, CXCL13) has been established through bioinformatics analysis and experimental validation [6]. High expression of TIMP1 in this signature is associated with poor prognosis, and functional experiments demonstrated that TIMP1 knockdown significantly inhibited CRC cell proliferation, metastasis, and promoted apoptosis [6].

The evolution of biomarker testing is reflected in the changing landscape of cancer care. As one breast cancer survivor diagnosed in 1994 noted, "Back then, all you got was ER and PR—HER2 hadn't been discovered yet. There wasn't even an internet when I was diagnosed" [21]. Thirty years later, patients need to understand the subtype of their cancer and their biomarker profile to access appropriate targeted drugs [21]. This shift toward precision oncology means that testing for biomarkers allows clinicians to match patients with precision therapies most likely to work for their specific disease [23].

Emerging Applications and Technologies

Innovative approaches are expanding the applications of biomarkers in clinical oncology. Machine learning and artificial intelligence are being applied to analyze complex biomarker data, enhancing predictive accuracy and enabling the integration of multiple data types for improved clinical decision-making [27]. For example, one study used nine different machine learning algorithms to analyze the relationship between 30 epigenetic biomarkers and the risk of diabetes and cancer, finding that epigenetic age acceleration was strongly associated with cancer risk [27].

Single-cell analyses are also providing unprecedented insights into tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment interactions. In high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC), characterized by significant intra-tumor heterogeneity, single-cell RNA-sequencing and single-cell epigenomics have identified 13 recurrent tumor transcriptomic phenotypes from over 200,000 malignant cells [25]. Longitudinal analyses revealed that chemotherapy enriched for cells possessing mesenchymal and inflammatory features while reducing cells displaying proliferative, hypoxic, and interferon-associated states [25]. Such detailed characterization of tumor heterogeneity represents a step toward personalized therapy for these patients.

Table 2: Clinically Validated Biomarkers Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Validated Genetic Biomarkers | Validated Epigenetic Biomarkers | Associated Targeted Therapies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer | KRAS, NRAS, BRAF mutations, MSI-H | MLH1 promoter hypermethylation | Anti-EGFR therapies, Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| Breast Cancer | BRCA1/2, HER2, PIK3CA mutations | - | PARP inhibitors, HER2-targeted therapies |

| Lung Cancer | EGFR, ALK, ROS1, BRAF mutations | - | EGFR inhibitors, ALK/ROS1 inhibitors |

| Leukemia/Lymphoma | BCR-ABL fusion gene | - | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Analysis

Bioinformatics Workflow for Biomarker Discovery

The identification of novel biomarker signatures typically begins with comprehensive bioinformatics analysis of multi-omics data. A standard workflow for biomarker discovery involves several key stages, starting with data acquisition from public repositories such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [6]. Differential expression analysis is performed using tools like the "DESeq2" package in R to identify genes that are significantly upregulated or downregulated in cancer tissues compared to normal controls [6].

Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) can then be applied to identify gene modules with comparable expression patterns and examine the relationship between these modules and specific clinical traits [6]. The "WGCNA" R package is used to construct a gene co-expression network, with a minimum number of genes per module typically set at 30 [6]. Functional enrichment analysis using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways helps identify biological processes and signaling pathways significantly associated with the candidate biomarker genes [6]. Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks can be constructed using the STRING database and visualized in Cytoscape to identify hub genes within the biomarker network [6].

Diagram Title: Bioinformatics Biomarker Discovery Workflow

DNA Methylation Analysis Protocol

The analysis of DNA methylation biomarkers involves specific methodological considerations due to the chemical nature of this epigenetic modification. Various methods exist for DNA methylation analysis, broadly categorized into genome-wide discovery approaches and targeted validation methods [3]. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) and reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) are widely used for biomarker discovery, providing broad methylome coverage through bisulfite-based chemical conversion that converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged [3].

Enzymatic methyl-sequencing (EM-seq), along with emerging third-generation sequencing technologies such as nanopore and single-molecule real-time sequencing, offers comprehensive methylation profiling without chemical conversion, thereby better preserving DNA integrity [3]. This is particularly advantageous for liquid biopsy analyses where DNA quantity is often limited. For clinical validation, targeted methods such as quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) and digital PCR (dPCR) offer highly sensitive, locus-specific analysis, making them suitable for routine clinical use [3]. The selection of appropriate control groups and sufficient independent validation in large-scale clinical studies are critical factors for successful clinical translation of DNA methylation biomarkers [3].

Transcriptomic Analysis of Alternative Splicing

The identification of alternative splicing biomarkers requires specialized transcriptomic approaches. A standard protocol begins with RNA sequencing of patient samples and cancer cell lines, followed by comprehensive analysis of the transcriptomic landscape with a focus on alternative splicing events [26]. Bioinformatics tools are used to identify robust cancer- and subtype-specific alternative splicing biomarkers that are consistently effective across different sample types [26].

Regulatory network analysis with a focus on RNA-binding proteins can reveal key splicing factors such as QKI and SR proteins that modulate specific splicing events [26]. For example, studies have shown that QKI modulates the splicing of PLEKHA1 exon 15, a cancer-specific alternative splicing biomarker, while SRSF1 regulates the splicing of MKNK2 exon 14, a subtype-specific biomarker [26]. Experimental validation of these regulatory relationships typically involves modulation of the identified RNA-binding proteins (overexpression or knockdown) followed by analysis of the resulting splicing changes using RT-PCR or nanoscale liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry.

Research Reagent Solutions

The experimental workflows described require specialized reagents and kits optimized for specific applications. The following table outlines essential research reagent solutions for biomarker discovery and validation studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Biomarker Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Products/Kits | Application Note | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | Plasma cfDNA extraction kits, FFPE RNA extraction kits | Maintain integrity of degraded samples from liquid biopsies or archived tissues | For cfDNA: optimize for fragment length <200bp; For FFPE: include DNase/RNase treatment |

| Bisulfite Conversion | EZ DNA Methylation kits, Premium Bisulfite kits | Complete conversion of unmethylated cytosine to uracil | DNA damage minimization; conversion efficiency validation with controls |

| Library Preparation | TruSeq Methyl Capture EPIC, SMARTer Stranded RNA-Seq | Target enrichment for methylation or transcriptome | Input amount requirements; compatibility with downstream sequencing platforms |

| qPCR/dPCR Reagents | ddPCR Mutation Detection assays, MethyLight reagents | Absolute quantification of rare variants or methylation | Probe design for CpG sites; optimization of annealing temperatures |

| Antibodies | Anti-5-methylcytosine, Histone modification-specific antibodies | Immunoprecipitation-based enrichment | Specificity validation; application in MeDIP-seq or ChIP-seq protocols |

Regulatory and Implementation Considerations

The successful translation of biomarkers from research discoveries to clinical applications requires careful attention to regulatory and implementation challenges. Despite the identification of numerous potential biomarkers in research settings, only a limited number have achieved routine clinical adoption [3]. Searching PubMed with the MeSH terms "Biomarkers" and "DNA Methylation" together with "cancer" returns 6,191 publications since 1996, yet this vast amount of research is not reflected in the number of DNA methylation biomarkers in clinical use [3].

Several factors affect the successful clinical implementation of biomarkers, including the choice of liquid biopsy source, selection of appropriate control groups in both discovery and validation phases, sufficient independent validation, and large-scale clinical studies to demonstrate clinical utility [3]. The variability in overall cell-free DNA among patients with the same cancer type is often larger than the variability between different cancer types, while the fraction of circulating tumor DNA tends to differ more consistently between cancer types and stages—a crucial consideration for diagnostic sensitivity, particularly in early-stage disease [3].

Efforts to expand access to biomarker testing are underway through policy initiatives and educational programs. The American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (ACS CAN) is working to expand insurance coverage of comprehensive biomarker testing, with biomarker testing coverage for state-regulated plans already established in multiple states including Arizona, California, New York, and Texas [24]. Educational initiatives like the Maine Cancer Genomics Initiative (MCGI) are working to bridge knowledge gaps by teaching healthcare providers how to interpret genomic testing and use cancer biomarkers to guide treatment, ensuring that precision oncology treatments aren't limited to major research hospitals [23]. Studies have shown that patients who receive genome-matched treatment based on biomarker testing are 31% less likely to die within one year compared to those who do not receive matched treatment [23].