Tumor Mutational Burden Measurement by NGS: A Comprehensive Guide for Cancer Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive examination of Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) as a predictive biomarker for immunotherapy response, focusing on Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) methodologies.

Tumor Mutational Burden Measurement by NGS: A Comprehensive Guide for Cancer Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) as a predictive biomarker for immunotherapy response, focusing on Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) methodologies. It covers the biological foundation of TMB, explores targeted panel sequencing as a practical alternative to whole exome sequencing, addresses critical technical challenges in measurement standardization, and discusses analytical validation approaches. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current evidence and emerging best practices to guide robust TMB implementation in both research and clinical trial contexts, highlighting optimization strategies and future directions for this dynamic field.

The Biological and Clinical Foundation of Tumor Mutational Burden

Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB), defined as the total number of somatic mutations per megabase (mut/Mb) of interrogated genomic sequence, has emerged as a critical predictive biomarker for response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) across multiple cancer types. The clinical significance of TMB stems from its role as a proxy for the generation of tumor-specific neoantigens—novel peptides arising from somatic mutations that are recognized by the immune system as foreign. This technical review examines the standardized definition of TMB, the biological pathway linking mutational burden to neoantigen genesis and antitumor immunity, current methodological approaches for TMB assessment, and the integration of this biomarker into clinical oncology practice. With the FDA's 2020 approval of pembrolizumab for TMB-high (≥10 mut/Mb) solid tumors based on the KEYNOTE-158 trial, standardized measurement and interpretation of TMB has become increasingly essential for translational researchers and drug development professionals.

The quantification of somatic mutations in tumor tissue has evolved from a research curiosity to a clinically validated biomarker that informs treatment selection. TMB measures the total number of non-inherited mutations detected per million bases (Mb) of sequenced genomic DNA [1]. This metric varies significantly across cancer types, with melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and squamous carcinomas typically demonstrating the highest TMB values, while leukemias and pediatric tumors show the lowest levels [1].

The biological rationale for TMB as a predictive biomarker lies in the immunogenic nature of mutation-derived neoantigens. As the mutational burden increases, so does the statistical probability that certain mutations will generate novel protein sequences that can be processed and presented as neoantigens on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules [2]. These neoantigens are recognized as "non-self" by T cells, triggering an immune response that can be augmented by ICIs [3]. The FDA's landmark approval of pembrolizumab for TMB-high solid tumors in June 2020 established TMB as the first pan-cancer biomarker for immunotherapy response prediction [1] [4].

The Biological Pathway: From Somatic Mutations to Antitumor Immunity

The process by which somatic mutations lead to enhanced antitumor immunity involves multiple sequential steps, each with important implications for therapeutic response.

Neoantigen Genesis and Immunogenicity

Neoantigens arise primarily from non-synonymous somatic mutations—including single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions and deletions (INDELs), and gene fusions—that alter protein sequence and create novel peptide sequences absent in normal tissues [2]. These altered proteins are processed intracellularly into peptides, loaded onto MHC molecules, and transported to the cell surface for T-cell recognition. The immunogenic potential of neoantigens depends on multiple factors, including the binding affinity of mutant peptides to MHC molecules, the abundance of resulting peptide-MHC complexes on the tumor cell surface, and the presence of T-cell receptors capable of recognizing these complexes [3].

Not all mutations contribute equally to neoantigen generation. Frameshift INDELs often generate more immunogenic neoantigens compared to SNVs due to more substantial alterations in protein sequence [2]. Microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) tumors, which result from deficient DNA mismatch repair (dMMR) mechanisms, accumulate numerous frameshift mutations that generate shared frameshift neoantigens across cancer types [2]. This explains the particularly high response rates to ICIs observed in MSI-H/dMMR tumors across multiple cancer types [5].

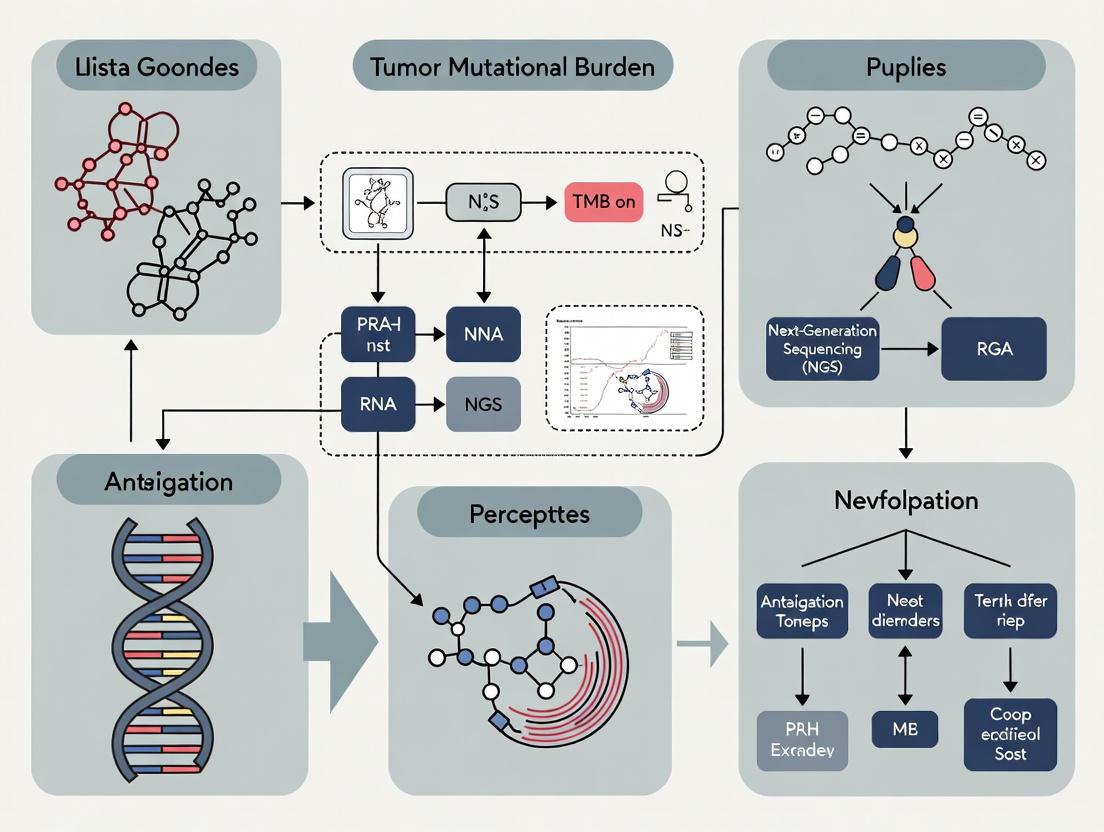

Figure 1: The pathway from somatic mutations to antitumor immunity through neoantigen genesis. Multiple mutation sources contribute to neoantigen formation, which enables immune recognition and is enhanced by checkpoint inhibition.

TMB as a Surrogate for Neoantigen Load

While neoantigen burden (the actual number of immunogenic mutations) would theoretically represent the ideal predictive biomarker, its assessment requires complex analyses incorporating HLA typing, peptide-MHC binding predictions, and T-cell recognition assays [6]. In contrast, TMB serves as a practical and robust surrogate that correlates with neoantigen load across diverse cancer types [3]. Research demonstrates that only a small fraction of somatic mutations (approximately 1-2%) ultimately generate immunogenic neoantigens, but this fraction remains relatively consistent across patients and cancer types [2]. This consistent ratio enables TMB to function as an effective clinical predictor of ICI response.

The relationship between TMB and neoantigen load explains the superior outcomes observed with ICIs in high-TMB cancers. Tumors with higher TMB present a broader repertoire of neoantigens to the immune system, increasing the probability of effective T-cell recognition and killing when immune checkpoints are blocked [4] [1]. This mechanism underpins the association between high TMB and improved response to ICIs across multiple cancer types, as demonstrated in pivotal trials such as KEYNOTE-158 [4].

Methodological Approaches for TMB Assessment

Accurate TMB measurement requires careful consideration of multiple technical factors, including sequencing methodology, bioinformatic processing, and variant filtering criteria.

Sequencing Platforms and Technical Considerations

TMB can be assessed using whole genome sequencing (WGS), whole exome sequencing (WES), or targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) panels, each with distinct advantages and limitations for clinical application.

Table 1: Comparison of TMB Measurement Approaches

| Parameter | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Large Targeted Panels (>1 Mb) | Small Targeted Panels (<1 Mb) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Coverage | ~30-40 Mb (entire exome) | 1.1-2.4 Mb (selected genes) | 0.8-1.0 Mb (limited genes) |

| TMB Correlation with WES | Gold standard | High (R² > 0.9) | Moderate to low |

| Clinical Feasibility | Low (cost, turnaround time) | High | High |

| Tumor Content Requirements | High (>30%) | Moderate (>20%) | High (>30%) |

| Variant Detection Sensitivity | High for coding regions | High for panel regions | Limited by panel size |

| Examples | Research standard | FoundationOneCDx, MSK-IMPACT, TSO500 | Various hotspot panels |

WES represents the historical gold standard for TMB assessment, interrogating approximately 30-40 megabases of coding sequence across ~20,000 genes [4]. While comprehensive, WES remains impractical for routine clinical use due to high cost, long turnaround time, and substantial tissue requirements [4] [1]. Targeted NGS panels covering 1.1-2.4 megabases have emerged as the preferred methodology for clinical TMB assessment, offering an optimal balance of comprehensiveness, cost-effectiveness, and clinical turnaround time [7].

The precision of TMB estimation depends significantly on panel size. The coefficient of variation of panel-based TMB decreases inversely with both the square root of the panel size and the square root of the TMB level [4]. Panels covering at least 1-1.5 Mb of coding sequence demonstrate improved correlation with WES-derived TMB and more reliable classification of TMB-high status [7].

Wet-Lab Protocols and Bioinformatics Analysis

Robust TMB assessment requires standardized wet-lab methodologies and bioinformatic pipelines to ensure reproducible results across laboratories.

Sample Processing and Sequencing

The typical workflow begins with DNA extraction from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue or frozen specimens. FFPE specimens present particular challenges due to formalin-induced DNA damage, which can artifactually inflate TMB estimates if not properly addressed [5] [1]. After DNA extraction and quality control, libraries are prepared using targeted hybridization capture approaches, followed by next-generation sequencing on platforms such as Illumina's NextSeq 550Dx [7].

The Institut Curie protocol exemplifies a rigorous approach to TMB assessment, incorporating sample-specific quality thresholds and variant allele frequency (VAF) filters. Their methodology establishes optimal VAF cut-offs at 10% for FFPE samples and 5% for frozen samples to minimize false-positive mutations while retaining sensitivity [5]. This group also emphasizes the importance of pre-analytical DNA quality assessment, particularly for FFPE samples, where DNA degradation can significantly impact TMB accuracy [5].

Bioinformatic Processing and Variant Filtering

Bioinformatic pipelines for TMB calculation typically include sequence alignment, variant calling, and extensive filtering to exclude germline polymorphisms, sequencing artifacts, and driver mutations that may not contribute to neoantigen formation.

Table 2: Variant Filtering Criteria for TMB Calculation

| Filter Category | Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Variant Type | Non-synonymous SNVs, nonsense mutations, small indels | Synonymous mutations, intronic variants, large structural variants |

| Population Frequency | Absent from population databases (gnomAD, 1000 Genomes) | Variants with population frequency >0.1% |

| Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) | ≥10% for FFPE samples, ≥5% for frozen samples | Below threshold or >95% (potential germline) |

| Mutation Location | Protein-coding regions | Non-coding regions, promoter elements |

| Artifact Filtering | Passes strand bias, base quality, and mapping quality filters | FFPE-induced C>T transitions, sequencing errors |

| Driver Mutations | Included in some panels (MSK-IMPACT) | Excluded in some panels (FoundationOne CDx) |

The FoundationOne CDx algorithm exemplifies a tumor-only approach that includes synonymous mutations while excluding hotspot driver mutations, whereas MSK-IMPACT employs a tumor-normal paired approach with different filtering criteria [1]. These methodological differences highlight the importance of platform-specific validation and the current lack of complete harmonization across TMB assays [4].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for TMB Analysis

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application in TMB Research |

|---|---|---|

| FFPE DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality DNA from archived specimens | Ensures sufficient input material with minimal artifacts for reliable variant calling |

| Hybridization Capture Panels | Target enrichment for NGS | Focuses sequencing on clinically relevant genomic regions; panel size critical for TMB precision |

| UMI Adapters | Unique molecular identifiers | Reduces sequencing errors and improves variant calling accuracy by correcting PCR duplicates |

| Tumor-Normal Pair Analysis | Germline variant subtraction | Distinguishes somatic from inherited variants; requires matched normal tissue |

| Population Databases | Filtering of common polymorphisms | Identifies and excludes germline variants using databases like gnomAD and 1000 Genomes |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Variant calling and annotation | Platforms like Strelka for mutation detection; Kourami for HLA typing in neoantigen prediction |

TMB in Clinical Practice and Therapeutic Decision-Making

The translation of TMB from a research concept to a clinically actionable biomarker has progressed rapidly, culminating in regulatory approvals and inclusion in professional guidelines.

TMB Cutoffs and Predictive Value

The FDA-approved cutoff for TMB-high status is ≥10 mutations per megabase, based on data from the KEYNOTE-158 basket trial demonstrating significantly improved objective response rates to pembrolizumab in patients with TMB-high solid tumors [8] [4]. This pan-cancer threshold provides a standardized approach for patient selection, though evidence suggests optimal cutpoints may vary across cancer types [1].

Retrospective analyses demonstrate a clear relationship between TMB levels and response to ICIs. In one large cohort, patients with TMB ≥20 mut/Mb showed a 58% response rate to ICIs compared to 20% in patients with lower TMB [1]. The association between TMB and outcomes appears continuous rather than binary, with progressively higher TMB levels generally correlating with improved response, though exceptions exist in cancers such as renal cell carcinoma [4].

Integration with Other Biomarkers

TMB provides complementary information to other established biomarkers, including PD-L1 expression and microsatellite instability (MSI). While MSI-H/dMMR tumors typically exhibit high TMB, and MSI status predicts response to ICIs across cancer types, TMB can identify additional patients who may benefit from immunotherapy beyond those with MSI-H [4]. Similarly, the combination of TMB and PD-L1 expression may improve patient stratification compared to either biomarker alone [4] [7].

Emerging Approaches and Future Directions

Recent methodological advances aim to address current limitations in TMB assessment. Liquid biopsy approaches for blood-based TMB (bTMB) measurement offer a less invasive alternative to tissue biopsy, with promising data in non-small cell lung cancer suggesting bTMB ≥20 mut/Mb predicts improved outcomes with ICIs [7]. Additionally, novel methodologies for direct neoantigen identification from circulating tumor cells using apheresis and exome sequencing provide opportunities for minimally invasive neoantigen discovery [9].

The research community has initiated efforts to harmonize TMB measurement across platforms, including the Friends of Cancer Research TMB Harmonization Project, which aims to establish calibration standards and improve reproducibility across laboratory-developed tests [8]. Such initiatives are critical for ensuring consistent TMB assessment and clinical application across testing platforms.

Tumor Mutational Burden, defined as the number of somatic mutations per megabase of sequenced DNA, represents both a biological mediator of antitumor immunity and a clinically validated predictive biomarker for immunotherapy response. The connection between TMB and neoantigen genesis provides a mechanistic foundation for its predictive value, as increased mutational load enhances the probability of immunogenic neopeptide formation and T-cell recognition. Standardized measurement approaches using large targeted NGS panels have enabled TMB's translation into clinical practice, supported by level 1 evidence from prospective clinical trials. Ongoing efforts to harmonize assessment methodologies, refine predictive cutoffs across cancer types, and integrate TMB with complementary biomarkers will further optimize its utility for patient stratification and drug development in immuno-oncology.

Tumor Mutational Burden as a Predictive Biomarker for Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Response

Tumor mutational burden (TMB) has emerged as a significant quantitative biomarker for predicting response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) across multiple cancer types. Defined as the total number of somatic mutations per coding area of a tumor genome, TMB reflects the likelihood of neoantigen formation that can stimulate anti-tumor immune responses [10] [11]. This technical review examines the molecular basis of TMB, standardizes measurement methodologies, evaluates clinical validation evidence, and discusses integration with complementary biomarkers. While TMB shows considerable promise for personalizing immunotherapy, challenges remain in standardization, interpretation across cancer types, and accounting for tumor microenvironment influences that collectively impact clinical utility [10] [12].

TMB represents a quantifiable measure of genetic alterations accumulated within a tumor genome. The underlying hypothesis posits that tumors with higher mutation loads generate more neoantigens - novel peptides resulting from somatic mutations that are recognized as foreign by the immune system [10]. These neoantigens are presented on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, triggering T-cell activation and proliferation. In immunologically competent environments, this increased neoantigen burden enhances tumor immunogenicity and facilitates greater T-cell infiltration, ultimately rendering tumors more susceptible to immune checkpoint blockade [10] [11].

The relationship between TMB and ICI response extends beyond mere mutation quantity. Specific mutation classes, particularly nonsynonymous mutations that alter amino acid sequences, demonstrate stronger correlations with immunogenicity than silent mutations [13]. Additionally, mutational processes influencing TMB vary across cancer types, with ultraviolet light exposure in melanoma, tobacco smoking in lung cancer, and DNA repair deficiencies in various malignancies all contributing to distinct mutational signatures that differentially impact neoantigen quality and immune recognition [13].

Table 1: Key Molecular Processes Influencing TMB

| Biological Process | Impact on TMB | Representative Genes/Pathways |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Damage Repair | Defective repair dramatically increases mutation accumulation | MMR genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2), POLE/POLD1 [11] |

| DNA Replication Fidelity | Polymerase errors increase mutation rate | POLE/POLD1 [11] |

| Carcinogen Exposure | Induces characteristic mutational signatures | Smoking (lung), UV light (melanoma) [13] |

| Homologous Recombination Repair | Deficiency increases genomic instability | BRCA1/2, ATM, RAD51 [10] |

Methodologies for TMB Assessment

Sequencing Approaches and Platforms

TMB measurement methodologies have evolved substantially, with next-generation sequencing (NGS) now representing the standard approach. Whole exome sequencing (WES) interrogates approximately 60 megabases (Mb) of protein-coding regions, providing the most comprehensive mutation assessment [14]. However, practical constraints including cost, turnaround time, and analytical complexity have driven development of targeted gene panels that estimate TMB from smaller genomic regions, typically ranging from 0.8 to 2.0 Mb [10] [14].

The FoundationOne CDx (324 genes) and MSK-IMPACT (468 genes) assays represent FDA-approved comprehensive genomic profiling platforms validated for TMB assessment [11] [13]. These targeted panels demonstrate strong correlation with WES when properly calibrated and provide a practical solution for clinical implementation [14]. Essential technical specifications for reliable TMB measurement include adequate tumor content (typically >20%), sufficient sequencing depth (>500x), and appropriate bioinformatic pipelines for germline mutation filtering [14].

Diagram 1: TMB Analysis Workflow

Blood-Based TMB (bTMB) Assessment

Liquid biopsy approaches for measuring TMB in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) address limitations of tissue sampling, including invasiveness, tumor heterogeneity, and serial monitoring challenges [15] [16]. The Foundation Medicine bTMB assay targets 1.1 Mb of genomic sequence and requires adequate ctDNA representation, typically defined as maximum somatic allele frequency (MSAF) ≥1% [16].

Recent validation studies demonstrate promising correlations between bTMB and tissue TMB, though technical challenges remain. The phase 2 B-F1RST trial evaluated bTMB as a predictive biomarker for first-line atezolizumab in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), finding that bTMB ≥16 (approximately 14.5 mutations/Mb) was associated with improved overall survival (OS) despite not meeting the primary progression-free survival endpoint [16]. Similarly, the DART study in stage III NSCLC reported that high bTMB using both prespecified (8.5 mut/Mb) and median (6.6 mut/Mb) cutoffs correlated with longer progression-free survival following chemoradiotherapy and durvalumab [15].

Table 2: TMB Measurement Methodologies Comparison

| Parameter | Whole Exome Sequencing | Targeted NGS Panels | Blood-Based TMB |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Coverage | ~60 Mb (entire exome) | 0.8-2.0 Mb (selected genes) | ~1.1 Mb (Foundation Medicine) [16] |

| Advantages | Comprehensive mutation detection; gold standard | Clinical feasibility; faster turnaround; lower cost | Minimally invasive; captures heterogeneity; enables monitoring [15] [16] |

| Limitations | Cost; analysis complexity; clinical turnaround | Requires validation against WES; panel size effects | Requires sufficient ctDNA (MSAF ≥1%); analytical sensitivity [16] |

| Clinical Implementation | Primarily research | FoundationOne CDx, MSK-IMPACT | Foundation Medicine bTMB assay [16] |

Clinical Validation of TMB as a Predictive Biomarker

Evidence Across Tumor Types

TMB demonstrates variable predictive value across cancer types, reflecting distinct immunobiological contexts. Consistent evidence supports TMB's predictive utility in NSCLC, melanoma, and urothelial carcinomas, while more limited associations appear in esophageal/gastric cancers and renal cell carcinoma [17] [12].

The phase 3 CheckMate 227 trial established TMB ≥10 mut/Mb as a predictive cutoff for first-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab in NSCLC, with significantly improved progression-free survival versus chemotherapy (7.2 vs. 5.5 months; HR 0.58) [13]. Similarly, a meta-analysis of 26 studies encompassing 5,712 patients demonstrated that high-TMB groups exhibited superior overall survival and progression-free survival with ICI treatment compared to low-TMB groups [10]. However, a VA population study found that while TMB ≥10 mut/Mb predicted improved survival in NSCLC, head and neck cancer, and urothelial cancer, no significant association was observed in melanoma or esophageal/gastric cancer, highlighting that fixed TMB thresholds may not apply universally across tumor types [17].

Tumor-Agnostic Approvals and Limitations

In 2020, the FDA granted accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for unresectable or metastatic solid tumors with TMB ≥10 mut/Mb that had progressed on prior treatments, based on the KEYNOTE-158 trial showing an overall response rate of 29% in the high-TMB cohort [12]. This tumor-agnostic approval represents a significant milestone but has generated controversy regarding optimal cutoffs, clinical utility across diverse malignancies, and absence of overall survival benefit in some analyses [12].

Research suggests that TMB thresholds may need tumor-specific optimization. A Northwestern University study found that in non-ICI-sensitive tumor types (those without FDA approval for ICI monotherapy), a higher TMB cutoff of ≥15 mut/Mb correlated with improved outcomes, whereas the standard ≥10 mut/Mb cutoff sufficed for ICI-sensitive tumors [12]. Additionally, specific mutational contexts influence TMB's predictive value; for instance, MYC pathway mutations and MLL2 alterations were associated with poorer ICI responses despite high TMB, while TERT mutations correlated with better responses [12].

Table 3: TMB Cutoffs and Associated Clinical Outcomes Across Selected Malignancies

| Cancer Type | Key Trial/Study | TMB Cutoff | Clinical Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSCLC | CheckMate 227 [13] | ≥10 mut/Mb | Improved PFS with nivolumab + ipilimumab vs chemo (7.2 vs 5.5 mo; HR 0.58) |

| Multiple Solid Tumors | KEYNOTE-158 [12] | ≥10 mut/Mb | ORR 29% with pembrolizumab; basis for FDA tumor-agnostic approval |

| SCLC | CheckMate 032 [18] | ≥248 mutations/tumor (WES) | Improved 1-year OS with nivolumab + ipilimumab (62.4% vs 23.4% in TMB-low) |

| NSCLC (Blood TMB) | B-F1RST [16] | ≥16 (≈14.5 mut/Mb) | Associated with longer OS with atezolizumab (36.5-month follow-up) |

| Non-ICI-sensitive Tumors | Northwestern Study [12] | ≥15 mut/Mb | Correlated with improved outcomes in tumors not typically ICI-sensitive |

Integration with Complementary Biomarkers

TMB alone provides incomplete predictive information, spurring investigation into multimodal biomarker strategies. PD-L1 expression represents the most established complementary biomarker, with evidence suggesting independent predictive value from TMB [15] [19]. The DART study in stage III NSCLC found that both PD-L1 ≥1% and high bTMB were independently associated with longer progression-free survival following chemoradiotherapy and durvalumab [15].

Specific mutational signatures and pathways further refine TMB's predictive capacity. Deficiencies in DNA damage response pathways, particularly mismatch repair (MMR) deficiencies leading to microsatellite instability (MSI-H), confer exceptionally high TMB and pronounced sensitivity to ICIs [11]. Additionally, mutations in STK11, KEAP1, and NFE2L2 have been associated with immunologically cold tumor microenvironments and resistance to ICIs despite high TMB [15]. These findings underscore the importance of evaluating both quantitative mutational burden and qualitative aspects of the tumor immune microenvironment.

Diagram 2: TMB and Modulating Factors in ICI Response

Emerging Approaches and Future Directions

Novel Predictive Models

Machine learning approaches integrating TMB with routinely available clinical and laboratory data show promise for improving prediction accuracy. The SCORPIO model, developed using data from 9,745 ICI-treated patients across 21 cancer types, utilizes complete blood counts, comprehensive metabolic profiles, and clinical characteristics to predict ICI outcomes [19]. In validation studies, SCORPIO significantly outperformed TMB alone for predicting overall survival (median time-dependent AUC 0.763 vs. 0.503) and clinical benefit (AUC 0.714 vs. 0.546), suggesting that composite models may surpass single-marker approaches [19].

Dynamic TMB assessment represents another emerging frontier. Longitudinal monitoring of TMB during treatment may provide early response indicators, with one melanoma study finding that early on-treatment changes in TMB (ΔTMB) strongly correlated with anti-PD-1 response and overall survival [11]. Liquid biopsy approaches facilitate such serial monitoring and may capture evolving clonal dynamics under therapeutic pressure.

Standardization Challenges and Research Needs

Substantial variability in TMB measurement methodologies, bioinformatic pipelines, and cutoff definitions currently hampers broader clinical implementation [10] [17]. The Friends of Cancer Research TMB Harmonization Project has demonstrated that while laboratory-specific differences exist, appropriate calibration can achieve consistent classification across platforms [10].

Key research priorities include establishing tumor-type-specific optimal cutoffs, validating blood-based TMB approaches, and refining integrated biomarker models that incorporate both tumor-intrinsic and host immune factors [12] [16]. Additionally, greater understanding of neoantigen quality rather than mere quantity may enhance prediction, as immunogenic potential varies substantially across mutation classes [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Key Experimental Resources for TMB Research

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Application in TMB Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, NextSeq | High-throughput sequencing for WES and targeted panels [14] |

| Targeted Panels | FoundationOne CDx, MSK-IMPACT | Clinical TMB measurement; validated against WES [11] [13] |

| Liquid Biopsy Assays | Foundation Medicine bTMB | Blood-based TMB assessment; requires MSAF ≥1% [16] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Mutect2, VarScan, VEP | Somatic variant calling and annotation [14] |

| Reference Standards | Horizon Discovery, SeraCare | Method validation and cross-laboratory standardization |

| Data Resources | TCGA, cBioPortal | Reference TMB distributions across cancer types [14] |

Tumor mutational burden represents a fundamentally important biomarker with validated predictive capacity for immune checkpoint inhibitor responses across multiple cancer types. The biological rationale linking high mutation load to increased neoantigen formation and enhanced tumor immunogenicity provides a compelling mechanistic framework. However, clinical application requires careful consideration of measurement methodologies, tumor-type context, and integration with complementary biomarkers including PD-L1 expression and specific genomic alterations. Ongoing efforts to standardize assessment methodologies, validate blood-based approaches, and develop integrated predictive models will further solidify TMB's role in personalizing cancer immunotherapy and advancing precision oncology.

Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) represents the total number of somatic mutations per megabase (mut/Mb) within a tumor genome's coding region [7]. As a quantifiable genomic biomarker, TMB functions as a surrogate for neoantigen load, with the underlying hypothesis that tumors possessing higher mutation counts are more likely to express neoantigens recognizable by the immune system, thereby enhancing susceptibility to immune checkpoint blockade therapy [7] [20]. The clinical validation of TMB represents a significant advancement in precision immuno-oncology, enabling better identification of patients who may derive exceptional benefit from immunotherapy across diverse cancer types.

This technical analysis examines the foundational evidence from two landmark clinical trials, KEYNOTE-158 and CheckMate 227, which prospectively validated TMB as a predictive biomarker for immunotherapy response. We explore their experimental methodologies, primary efficacy outcomes, and the subsequent impact on biomarker-driven drug development within the context of next-generation sequencing (NGS) research.

KEYNOTE-158: Prospective Validation of TMB in Advanced Solid Tumors

Study Design and Experimental Protocol

KEYNOTE-158 (NCT02628067) was a prospective, multi-cohort, open-label, phase 2 biomarker analysis that evaluated the efficacy of pembrolizumab monotherapy across multiple advanced solid tumors [21]. The trial was conducted across 81 academic and community institutions in 21 countries, enrolling patients aged ≥18 years with selected, previously treated advanced solid tumors (anal, biliary, cervical, endometrial, mesothelioma, neuroendocrine, salivary, small-cell lung, thyroid, and vulvar) who had progressed on or were intolerant to standard therapy [21].

Key Methodological Elements:

- Intervention: Pembrolizumab 200 mg intravenously every 3 weeks for up to 35 cycles

- TMB Assessment: Tissue TMB (tTMB) was evaluated in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples using the FoundationOne CDx assay

- Prespecified TMB-H Threshold: ≥10 mutations per megabase

- Primary Endpoint: Objective response rate (ORR) per RECIST 1.1 by independent central review

- Statistical Analysis: Efficacy was assessed in the treated population with evaluable tTMB data enrolled ≥26 weeks before data cutoff (June 27, 2019) [21]

Key Efficacy Findings and Clinical Outcomes

At data cutoff, 1073 patients were enrolled, with 1066 receiving treatment. Among these, 790 patients were evaluable for TMB and included in efficacy analyses. The TMB-high population (≥10 mut/Mb) comprised 102 patients (13%), while 688 patients (87%) had non-TMB-high status (<10 mut/Mb). After a median follow-up of 37.1 months, the study demonstrated a substantial differential response based on TMB status [21].

Table 1: KEYNOTE-158 Efficacy Outcomes by TMB Status

| Parameter | TMB-High (≥10 mut/Mb) | Non-TMB-High (<10 mut/Mb) |

|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 102 | 688 |

| Objective Response Rate, % (95% CI) | 29% (21-39) | 6% (5-8) |

| Complete Response, n | 4 | 7 |

| Partial Response, n | 26 | 36 |

| Safety Population, n | 105 | - |

| Grade 3-5 Treatment-Related AEs, % | 15% | - |

| Treatment-Related Serious AEs, % | 10% | - |

The robust response rate in the TMB-high subgroup, which was nearly five-fold greater than in non-TMB-high patients, led the investigators to conclude that tTMB could serve as a novel and useful predictive biomarker for response to pembrolizumab monotherapy in patients with previously treated recurrent or metastatic advanced solid tumors [21].

CheckMate 227: TMB as a Biomarker for Dual Immunotherapy in NSCLC

Trial Methodology and Biomarker Assessment

CheckMate 227 was a pivotal phase 3 trial evaluating first-line immunotherapy in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Part 1 of this complex trial specifically examined the efficacy of nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus chemotherapy in patients with high TMB (≥10 mut/Mb), regardless of PD-L1 expression level [22].

Key Methodological Elements:

- Interventions: Nivolumab + ipilimumab versus chemotherapy

- TMB Assessment: Tissue TMB was evaluated using the FoundationOne CDx assay (324 genes)

- Prespecified TMB-H Threshold: ≥10 mutations per megabase

- Primary Endpoint: Progression-free survival (PFS) in the TMB-high population

- Statistical Design: The trial used a hierarchical testing strategy to evaluate multiple biomarker-defined populations [22]

Efficacy Outcomes and Long-Term Survival Data

CheckMate 227 Part 1 demonstrated that patients with high TMB (≥10 mut/Mb) experienced significantly improved progression-free survival with nivolumab plus ipilimumab compared to chemotherapy. Although initial reports indicated no significant overall survival difference in the TMB-high population, subsequent long-term follow-up analyses, particularly in patient subgroups, have confirmed durable clinical benefits [22] [23].

A recent pooled analysis of CheckMate 227 and CheckMate 9LA focusing on patients with tumor PD-L1 lower than 1% revealed substantial long-term benefits for nivolumab plus ipilimumab with or without chemotherapy. After a median follow-up of 73.7 months, the median overall survival was 17.4 months versus 11.3 months (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.54-0.76), with 5-year survival rates of 20% versus 7% favoring the immunotherapy-based regimens [23].

Table 2: CheckMate 227/9LA Pooled Analysis in PD-L1 <1% Population

| Outcome Measure | Nivo+Ipi (±Chemo) | Chemotherapy | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 322 | 315 | - |

| Median OS, months | 17.4 | 11.3 | 0.64 (0.54-0.76) |

| 5-Year OS Rate, % | 20 | 7 | - |

| Median PFS, months | 5.4 | 4.9 | 0.72 (0.60-0.87) |

| 5-Year PFS Rate, % | 9 | 2 | - |

| Objective Response Rate, % | 29 | 22 | - |

| Median DoR, months | 18.0 | 4.6 | - |

The consistency of benefit across key subgroups, including patients with baseline brain metastases (HR = 0.44) and those with squamous histology (HR = 0.51), reinforces the clinical utility of this biomarker-driven approach [23].

Technical Methodologies for TMB Assessment

NGS-Based TMB Measurement Approaches

Accurate TMB quantification requires sophisticated genomic analysis methodologies. The two primary NGS-based approaches for somatic mutation identification in solid tumors are:

- Tumor-Only (TO) Sequencing: Analyzes tumor tissue alone, comparing sequencing data against population databases to distinguish somatic mutations [24]

- Tumor-Control (TC) Paired Sequencing: Simultaneously sequences tumor tissue and matched normal (white blood cells or normal tissue) to directly differentiate somatic from germline variants [24]

Recent comparative studies demonstrate that these different methodological approaches can impact TMB results, particularly near the critical 10 mut/Mb threshold. One analysis of 24 solid tumor samples revealed 92% consistency between TO and TC methods, but statistically significant differences in TMB classification (χ² = 16.667, p < 0.001), highlighting the importance of methodological standardization [24].

Emerging Approaches: Blood-Based TMB Assessment

The development of blood-based TMB (bTMB) represents an emerging approach that circumvents tissue availability limitations. bTMB is derived from circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) using comprehensive genomic profiling. Early clinical data from studies such as MYSTIC and B-F1RST suggested potential utility, though subsequent trials like NEPTUNE and B-FAST (cohort C) failed to meet primary endpoints when using bTMB for patient selection [25].

The CheckMate 848 study evaluated concordance between tissue and blood TMB, demonstrating a statistically significant correlation across 1017 patients, particularly in samples with high maximum somatic allele frequency. However, discordant classification was observed in some cases, with patients exhibiting tTMB-high/bTMB-low status maintaining response rates of 35.0%, while those with bTMB-high/tTMB-low results showed reduced response rates of 9.7% [25].

Research Reagent Solutions for TMB Analysis

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for TMB Biomarker Development

| Research Tool | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| FoundationOne CDx | Comprehensive genomic profiling for tTMB | 324-gene panel; FDA-approved companion diagnostic; validated for TMB assessment in KEYNOTE-158 and CheckMate 227 [21] [22] |

| FoundationOne Liquid CDx | Blood-based comprehensive genomic profiling | ctDNA analysis; provides bTMB score; approved in Japan for cancer genomic profiling [25] |

| TruSight Oncology 500 | Comprehensive genomic profiling for tumor-only TMB | 523-gene panel; utilizes hybrid capture-based NGS; detects multiple biomarker classes [24] |

| MSK-IMPACT | Targeted sequencing for cancer genomics | 468-gene panel; used for institutional genomic profiling and TMB calculation in research settings [20] |

| Shihe No.1 TMB Detection Kit | Tissue TMB detection with matched normal | 425-gene panel; designed for tumor-control paired analysis; includes white blood cell control [24] |

Conceptual Framework of TMB and Immunotherapy Response

Figure 1: Mechanism of TMB-Driven Response to Immunotherapy

Experimental Workflow for TMB Assessment in Clinical Trials

Figure 2: TMB Testing Workflow in Clinical Trials

The prospective evidence from KEYNOTE-158 and CheckMate 227 firmly established TMB as a clinically actionable biomarker for immunotherapy across multiple cancer types. KEYNOTE-158 validated the use of TMB ≥10 mut/Mb as a predictive biomarker for pembrolizumab monotherapy in previously treated advanced solid tumors, while CheckMate 227 demonstrated the utility of TMB for identifying NSCLC patients who benefit from first-line nivolumab-ipilimumab combination therapy.

Ongoing research continues to refine our understanding of TMB, including:

- Standardization of TMB measurement across different NGS platforms and methodologies [24]

- Integration of TMB with other biomarkers (MSI, PD-L1, gene signatures) for improved patient stratification [20] [26]

- Development of blood-based TMB assays to address tissue limitations [25]

- Exploration of TMB heterogeneity and its relationship with underlying mutational processes (APOBEC, DNA damage repair) [20]

These landmark trials represent a paradigm shift in biomarker-driven drug development, establishing comprehensive genomic profiling and TMB assessment as essential components of precision immuno-oncology research. The continued refinement of TMB quantification and interpretation will further optimize patient selection for immunotherapy across an expanding range of malignancies.

Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) Variability Across Cancer Types and Etiologies (e.g., UV, Tobacco)

Tumor mutational burden (TMB), defined as the number of somatic mutations per megabase of interrogated genomic sequence, has emerged as a critical biomarker for predicting response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) across multiple cancer types [4] [27]. Its value stems from the correlation between increased mutation load and enhanced neoantigen formation, which promotes T-cell-mediated anti-tumor immunity when checkpoint signals are inhibited [4] [27]. However, TMB demonstrates remarkable variability across different malignancies, influenced by distinct etiologies including carcinogen exposure (e.g., tobacco, UV radiation) and endogenous mutational processes [4] [28] [29]. This technical review examines the landscape of TMB distribution across cancers, explores the molecular mechanisms underlying etiology-specific mutational patterns, and discusses standardized methodologies for TMB assessment in clinical and research settings. Understanding these variables is paramount for optimizing TMB's predictive value in immunotherapy and advancing personalized cancer treatment strategies.

TMB quantifies the total number of somatic non-synonymous mutations within a tumor's genome, serving as a proxy for its potential neoantigen landscape [27] [30]. The fundamental premise is that tumors with higher mutation loads are more likely to express immunogenic neoantigens that can be recognized by the immune system, particularly when treated with ICIs [4] [27]. The clinical significance of TMB was solidified by the KEYNOTE-158 trial, which led to FDA approval of pembrolizumab for TMB-high (≥10 mut/Mb) solid tumors regardless of histology [4] [8].

The accurate measurement of TMB presents substantial challenges. While whole exome sequencing (WES) represents the gold standard, covering approximately 30-50 Mb of coding sequence, its clinical implementation is hampered by high cost, long turnaround time, and significant tissue requirements [4] [31]. Consequently, targeted sequencing panels have been developed as practical alternatives, though they introduce variability due to differences in panel size, genomic coverage, and bioinformatic pipelines [4] [28]. The coefficient of variation of TMB derived from panel sequencing decreases inversely with both the square root of the panel size and the square root of the TMB level, meaning halving the CV requires a four-fold increase in panel size [4].

Quantitative Landscape of TMB Across Cancers

The distribution of TMB varies dramatically across cancer types, spanning more than a 1,000-fold range from childhood malignancies with approximately 0.1 mutations/Mb to hypermutated tumors exceeding 400 mutations/Mb [31]. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes revealed that nearly all cancer types contain a subset of patients with high TMB, including many rare tumors [28].

Table 1: TMB Distribution Across Selected Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Typical TMB Range (mut/Mb) | Etiological Associations | Representative Alterations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma | Very High (often >100) [31] | UV radiation exposure [4] | BRAF, NRAS mutations [28] |

| Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | Variable (0.6->10.5) [31] [29] | Tobacco smoke (dose-dependent) [29] | TP53, KRAS, EGFR mutations [29] |

| Cervical Cancer | 59% with TMB-high (≥10 mut/Mb) [32] | HPV infection (especially HPV52) [32] | PIK3CA, ARID1A mutations [32] |

| Breast Cancer | Mean: 4.6 mut/Mb; 6.7% with TMB≥10 [20] | Endogenous processes (APOBEC) [20] | PIK3CA, TP53, CDH1 mutations [20] |

| Colorectal Cancer (MSI-H) | Very High [4] | Mismatch repair deficiency [4] [28] | MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 mutations [28] |

Table 2: Impact of Smoking on TMB in Lung Adenocarcinoma [29]

| Smoking Metric | Effect on TMB | Genetic Associations |

|---|---|---|

| Doubling pack-years | Significant increase | Increased KRASG12C; decreased EGFRdel19 and EGFRL858R |

| Doubling smoking-free months | Significant decrease | Increased EGFRL858R mutations |

| Current vs. former smokers | Higher median TMB (40 vs. 24 pack-years) | Distinct pathway alterations |

Large-scale genomic analyses demonstrate that TMB increases significantly with age, showing a 2.4-fold difference between ages 10 and 90 [28]. This relationship highlights the cumulative nature of mutagenesis and may partially explain the varying immunotherapy responses across age groups.

Etiological Factors and Mutational Mechanisms

Exogenous Carcinogens

Tobacco Smoke: Smoking history demonstrates a clear dose-response relationship with TMB in lung adenocarcinoma, with doubling pack-years associated with significant TMB increases after controlling for age, gender, and stage [29]. The mutagenic effects of tobacco carcinogens create a distinct mutational signature characterized by C>A transversions, with specific impacts on cancer-related pathways including increased KRASG12C mutations and decreased EGFR mutations [29].

Ultraviolet (UV) Radiation: Melanoma and other skin cancers exhibit some of the highest TMB values across malignancies, directly attributable to UV-induced DNA damage [4] [28]. This relationship is mechanistically explained by the formation of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and pyrimidine-pyrimidone photoproducts that introduce characteristic C>T and CC>TT transitions at dipyrimidine sites [28].

Endogenous Mutational Processes

APOBEC Mutagenesis: In breast cancer, APOBEC (apolipoprotein B mRNA-editing enzyme catalytic polypeptide) represents the dominant mutational signature in 64.7% of TMB-high cases [20]. TMB-high breast carcinomas with APOBEC signatures demonstrate significant enrichment in KMT2C, ARID1A, PTEN, NF1, and RB1 alterations, and show higher mean TMB (19.6 mut/Mb) compared to those with other signatures [20].

DNA Repair Deficiencies: Deficiencies in mismatch repair (MMR) pathways lead to microsatellite instability (MSI) and hypermutation across multiple cancer types [4] [28]. Similarly, mutations in polymerase epsilon (POLE) and polymerase delta (POLD1) proofreading domains result in ultra-hypermutated phenotypes [28]. A novel finding includes somatic mutations in the promoter of PMS2, occurring in 10% of skin cancers and associated with dramatically increased TMB [28].

Viral Associations: In cervical cancer, high TMB was identified in 59% of cases and was associated with nodal involvement, diabetes, and HPV52 infection, but not with the more common HPV16/18 subtypes or FIGO stage [32]. This suggests HPV type-specific interactions with host genomic stability mechanisms.

Diagram 1: Etiology to Immunotherapy Response Pathway

Methodologies for TMB Assessment

Sequencing Approaches

Whole Exome Sequencing (WES): WES remains the gold standard for TMB measurement, covering approximately 30-50 Mb of coding sequence representing all ~22,000 genes [4] [31]. The typical workflow requires 150-200 ng of genomic DNA from both tumor and matched normal samples to accurately identify tumor-specific variants [31]. At 50× coverage, 95% of single nucleotide variants and short indels with variant allele frequency ≥15% can be consistently detected, though deeper sequencing improves sensitivity in impure or heterogeneous samples [31].

Targeted Gene Panels: Multiple commercially available targeted sequencing panels have been developed for TMB assessment, offering practical advantages including lower cost, faster turnaround, and compatibility with limited tissue samples [4] [31]. The FoundationOne CDx (324 genes, ~0.8 Mb coding coverage) and MSK-IMPACT (468 genes, ~1.14 Mb coding coverage) are FDA-approved panels that demonstrate moderate concordance with WES [4]. The confidence intervals for TMB estimation vary significantly with panel size, with smaller panels (<0.5 Mb) showing substantially increased variance [28].

Standardization Challenges

Harmonizing TMB measurement across platforms represents a critical challenge for clinical implementation [4]. Key variables include:

- Panel size and genomic content: Larger panels (>1 Mb) generally provide more precise TMB estimates [4] [28]

- Mutation types included: Some panels count only non-synonymous mutations while others include synonymous variants to reduce sampling noise [4]

- Bioinformatic pipelines: Variant calling algorithms and germline mutation filtering approaches differ significantly between platforms [4] [31]

- Tumor content requirements: Most assays require minimum tumor cellularity (typically 20-30%) for accurate mutation detection [4] [31]

Diagram 2: TMB Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for TMB Analysis

| Reagent/Platform | Type | Primary Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| FoundationOne CDx | Targeted NGS Panel | Comprehensive genomic profiling and TMB assessment | 324 genes, ~0.8 Mb coding coverage; FDA-approved [4] |

| MSK-IMPACT | Targeted NGS Panel | Tumor mutational profiling and TMB calculation | 468 genes, ~1.14 Mb coding coverage; FDA-authorized [4] |

| Oncomine Tumor Mutation Load Assay | Targeted NGS Panel | TMB estimation from limited tissue samples | 409 genes, ~1.2 Mb coverage; optimized for FFPE samples [4] |

| TruSight Oncology 500 | Targeted NGS Panel | Comprehensive genomic profiling with TMB | 523 genes, ~1.33 Mb coverage; includes DNA and RNA sequencing [4] |

| NetMHCpan | Bioinformatics Algorithm | Neoantigen prediction from mutation data | Predicts peptide-MHC binding affinity; critical for neoantigen load estimation [27] |

| SigMA | Computational Tool | Mutational signature analysis from targeted sequencing | Infers dominant mutational patterns from panel data [20] |

Discussion and Future Directions

The variability of TMB across cancer types and etiologies presents both challenges and opportunities for personalized immunotherapy. While TMB serves as a robust predictive biomarker in lung cancer and melanoma, its utility in breast, prostate, and other malignancies with lower mutational burden remains limited [33]. The differential predictive power across cancers suggests that TMB thresholds may need cancer-type-specific optimization rather than a universal pan-cancer cutoff [4] [33].

Future research directions should focus on:

- Prospective validation of optimized TMB cutoffs specific to cancer types and etiological backgrounds

- Integration of TMB with complementary biomarkers including PD-L1 expression, MSI status, and tumor microenvironment characterization [27] [33]

- Standardization of TMB measurement across platforms through initiatives like the Friends of Cancer Research TMB Harmonization Project [8]

- Development of novel methodologies for neoantigen quality assessment beyond quantitative mutation load [4] [27]

Understanding the complex interplay between environmental exposures, endogenous mutational processes, and DNA repair mechanisms will enhance our ability to stratify patients for immunotherapy and develop novel combination strategies to overcome resistance mechanisms.

TMB represents a dynamic biomarker reflecting the cumulative impact of diverse mutational processes operating across different cancer types. The profound variability in TMB distributions, driven by distinct etiologies including UV exposure, tobacco carcinogens, viral infections, and endogenous mutagenesis, underscores the necessity for context-specific interpretation of TMB values. While technological challenges in measurement standardization remain substantial, ongoing efforts to harmonize methodologies and validate clinical thresholds promise to refine TMB's utility as a predictive biomarker. For researchers and drug development professionals, recognizing the intricate relationship between cancer etiology, mutational signatures, and TMB is fundamental to advancing precision immuno-oncology and developing more effective therapeutic strategies.

The Interrelationship Between TMB, MSI, and PD-L1 Expression

The advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has revolutionized cancer treatment, yet a significant challenge remains: the majority of patients do not respond to these therapies. Predictive biomarkers are therefore critical for identifying patients most likely to benefit from treatment. Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression, tumor mutational burden (TMB), and microsatellite instability (MSI) have emerged as three pivotal biomarkers for guiding immunotherapy. These biomarkers reflect different aspects of tumor biology: PD-L1 represents adaptive immune resistance, TMB reflects tumor immunogenicity, and MSI indicates genomic instability due to deficient DNA mismatch repair.

Understanding the interrelationships between these biomarkers is essential for advancing precision oncology. This whitepaper, framed within the context of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) research, provides a technical examination of TMB, MSI, and PD-L1, detailing their clinical measurements, biological interactions, and combined utility in predicting response to immunotherapy.

Quantitative Landscape of TMB, MSI, and PD-L1 in Cancer

Clinical studies across various cancer types reveal distinct prevalence and interrelationships between these biomarkers. A study of 100 esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) patients provides illustrative data on their distribution and overlap [34] [35].

Table 1: Biomarker Prevalence in ESCC (n=100) [34] [35]

| Biomarker | Prevalence | Classification Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| PD-L1 Positive | 54% (54/100) | Combined Positive Score (CPS) ≥ 1% |

| TMB-High (TMB-H) | 57% (57/100) | > 80% quantile of mutations/Mb |

| MSI-High (MSI-H) | 1% (1/100) | Instability in multiplex PCR loci |

Table 2: Biomarker Overlap in ESCC TMB-H Cases (n=57) [34] [35]

| Biomarker Profile | Number of Cases | Percentage of TMB-H Subset |

|---|---|---|

| TMB-H and PD-L1 Positive | 32 | 56.1% |

| TMB-H, PD-L1 Positive, and MSI-H | 1 | 1.8% |

| TMB-H, PD-L1 Low, and MSI Low | 21 | 36.8% |

The data demonstrates that PD-L1 and TMB-H are frequently expressed in ESCC, whereas MSI-H is rare. Critically, there was no statistically significant association between PD-L1 expression levels and TMB, suggesting they may provide independent predictive information [34]. Furthermore, clinicopathological correlations were observed: PD-L1 positivity was significantly associated with advanced TNM staging, and TMB-H was significantly linked to lymph node metastasis [35].

This pattern of variable association is consistent across other malignancies. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), for instance, high TMB is associated with improved outcomes on ICIs, independent of PD-L1 status [36]. Pan-cancer analyses confirm that elevated TMB, MSI-H, and PD-L1 positivity can identify distinct patient subgroups that benefit from immunotherapy, underscoring the limitation of relying on a single biomarker [37].

Technical Methodologies for Biomarker Assessment

Accurate measurement of these biomarkers is foundational to both clinical decision-making and research. NGS has become a transformative technology, enabling comprehensive genomic profiling from a single assay [38].

PD-L1 Expression Analysis

Experimental Protocol: Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

PD-L1 expression is typically quantified at the protein level using IHC on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor specimens [35].

- Tissue Preparation: FFPE tumor tissue sections are cut at 4-5 µm thickness and mounted on slides.

- Antigen Retrieval: Heat-induced epitope retrieval is performed using Cell Conditioning Solution (CC1, Tris-EDTA buffer, pH 8.0) for 64 minutes at 95°C.

- Staining: Slides are incubated with a primary anti-PD-L1 antibody (e.g., Clone SP263). Detection is achieved using the OptiView DAB IHC Detection Kit, followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin.

- Scoring: PD-L1 expression is evaluated using the Combined Positive Score (CPS), calculated as: CPS = (Number of PD-L1-positive cells [tumor cells, lymphocytes, macrophages] / Total number of tumor cells) × 100 A CPS ≥ 1% is typically classified as PD-L1 positive [35].

An emerging, non-invasive alternative is the detection of exosomal PD-L1 (exo-PD-L1) from blood plasma. Exo-PD-L1 is derived from tumor cells and systemically suppresses T cell activity. Its levels dynamically reflect the tumor's immune status and show promise for predicting resistance to ICIs [39].

Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) Analysis

Experimental Protocol: Next-Generation Sequencing

TMB is defined as the number of somatic mutations per megabase (mut/Mb) of the genome examined [34] [38] [37].

- DNA Extraction: Genomic DNA is extracted from FFPE tissue sections or liquid biopsy samples using specialized kits (e.g., Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit). DNA quality and concentration are assessed (e.g., using Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit and Agilent TapeStation) [35].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: A minimum of 120 ng of DNA is used for library preparation. Target capture is performed using comprehensive gene panels (e.g., a 733-gene panel). Sequencing is conducted on platforms like Illumina, which provides high throughput and low error rates (0.1–0.6%) [38] [40].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Alignment: Sequencing reads are aligned to a reference human genome (e.g., hg19) using tools like BWA.

- Variant Calling: Somatic mutations (missense, nonsense mutations, and coding indels) are identified.

- TMB Calculation: TMB = (Total number of somatic mutations) / (Size of the targeted genomic region in Mb). TMB-H is often defined using percentile-based cut-offs (e.g., > 80% quantile) or a fixed threshold like 10 mut/Mb [34] [36] [37].

Microsatellite Instability (MSI) Analysis

Experimental Protocol: NGS-Based MSI Detection

While PCR-based methods have been the gold standard, NGS-based approaches offer expanded coverage and are highly concordant with traditional methods [40].

- Panel Design: An in-house NGS-based MSI detector (MSIDRL) can be developed by selecting hundreds of robust non-coding microsatellite (MS) loci. A training set of samples with predefined MSI status (e.g., by PCR) is used to establish a baseline [40].

- Sequencing & Analysis: For each MS locus in a sample, the number of reads supporting different repeat lengths is counted.

- Algorithm for MSI Calling: A novel algorithm involves:

- Defining a Diacritical Repeat Length (DRL): The repeat length that maximizes the read count difference between MSI-H and microsatellite stable (MSS) samples in the training set.

- Calculating Background Noise (B~i~): The baseline instability for each locus

iin MSS samples. - Statistical Testing: For each locus

iin a test samplej, the proportion of "unstable" reads (lengths ≤ DRL~i~) is calculated (b~ij~). A binomial test is used to compareb~ij~toB~i~. - Determining MSI Status: The Unstable Locus Count (ULC) is the number of loci significantly more unstable than the background. A ULC ≥ 11 (determined from a pan-cancer distribution) classifies a sample as MSI-H [40].

Diagram 1: NGS-based MSI calling workflow, based on a novel algorithm (MSIDRL) analyzed in 35,563 pan-cancer cases [40]. DRL: Diacritical Repeat Length.

Interrelationships and Biological Mechanisms

The interplay between TMB, MSI, and PD-L1 is complex and rooted in their shared role in anti-tumor immunity, yet they function through distinct mechanisms.

- TMB and Neoantigen Burden: High TMB leads to an increased generation of neoantigens—novel protein sequences that the immune system recognizes as foreign. This enhances tumor immunogenicity and T cell infiltration, creating a microenvironment more susceptible to immune checkpoint blockade [37].

- MSI as a Driver of TMB-H: MSI is a specific genomic signature caused by deficient mismatch repair (dMMR). This failure in DNA repair machinery results in a hypermutator phenotype, profoundly elevating TMB across numerous microsatellite regions [37] [40]. Thus, MSI-H is a direct genetic cause of exceptionally high TMB.

- PD-L1 as an Adaptive Immune Resistance Mechanism: The expression of PD-L1 on tumor cells or its secretion via exosomes is often an adaptive response to IFN-γ and other inflammatory signals released by tumor-infiltrating T cells. Therefore, a T cell-inflamed tumor microenvironment (often associated with high TMB) can drive the upregulation of PD-L1 as a primary mechanism of immune evasion [39].

- Independent and Complementary Biomarkers: Despite these connections, clinical data often show no direct statistical correlation between TMB and PD-L1 levels [34] [35]. This indicates that the processes governing mutational load and immune checkpoint expression are not perfectly coupled. They can be influenced by additional factors, such as tumor heterogeneity, the specific composition of the tumor microenvironment, and the dynamics of exosomal PD-L1 release, which can mediate systemic immunosuppression independent of tumor cell membrane PD-L1 [39].

Diagram 2: Logical relationships between dMMR/MSI, TMB, and PD-L1 expression. dMMR drives MSI-H, which causes high TMB. The resulting immune response triggers PD-L1 expression as an adaptive resistance mechanism [39] [37] [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful research in this field relies on a suite of specialized reagents, assays, and bioinformatic tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biomarker Analysis

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| FFPE Tissue Sections | Preserves tumor morphology and biomolecules for IHC and DNA extraction. | Standard for clinical samples; requires quality control (e.g., Agilent TapeStation) [35]. |

| Anti-PD-L1 Antibodies | Detection of PD-L1 protein expression via IHC. | Clones SP263, 22C3, 28-8; scoring depends on tumor type (CPS or TPS) [35] [37]. |

| NGS Gene Panels | Targeted sequencing for TMB and MSI calculation. | Comprehensive panels (e.g., 733-gene); must cover sufficient genomic space for accurate TMB [38] [40]. |

| MSI Loci Panel | A set of microsatellite loci for NGS-based MSI detection. | Pan-cancer panels (e.g., 7-100 loci) can outperform traditional PCR panels for non-colorectal cancers [40]. |

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality DNA from tissue or liquid biopsy. | Specialized kits for FFPE (e.g., Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit) are essential [35]. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Data analysis for variant calling, TMB, and MSI determination. | Tools like MSIsensor, BWA for alignment, GATK for variant calling [38] [40]. |

The interrelationship between TMB, MSI, and PD-L1 is multifaceted. While these biomarkers are functionally linked through the cancer immunity cycle, they provide non-redundant information. MSI can be a direct cause of high TMB, and the ensuing T-cell response can induce PD-L1 expression. However, the lack of a consistent statistical correlation between them underscores the complexity of tumor-immune interactions and the influence of other factors like exosomal PD-L1.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this has clear implications: a multi-modal biomarker approach is superior to reliance on any single marker for predicting response to immunotherapy. The integration of NGS, which allows for the simultaneous assessment of all three biomarkers from a single assay, is therefore paramount. Future research should focus on standardizing NGS-based biomarker assays, defining universal cut-off values, and further elucidating the dynamic crosstalk between the genome and the immune microenvironment to unlock the full potential of precision immuno-oncology.

From WES to Targeted Panels: NGS Methodologies for TMB Quantification

Whole exome sequencing (WES) has established itself as a fundamental tool in genomic research and clinical diagnostics, particularly in the context of cancer genomics and tumor mutational burden (TMB) assessment. By sequencing the protein-coding regions of the genome, WES provides comprehensive genetic information that enables researchers to identify mutations driving cancer development and progression. Its capacity to detect somatic mutations across all exonic regions has made WES the reference standard for TMB measurement, a critical biomarker predicting response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. However, significant technical and analytical limitations constrain its clinical application. This in-depth technical review examines WES methodologies, its established role in TMB quantification, and the inherent constraints researchers must navigate when implementing this technology in preclinical and clinical cancer research.

Whole exome sequencing is a next-generation sequencing (NGS) approach that targets the protein-coding regions of the human genome, comprising approximately 1% of the total genome but harboring an estimated 85% of disease-causing variants [41] [42]. The methodology involves selectively capturing and sequencing exonic regions from fragmented genomic DNA, generating data that encompasses single nucleotide variants (SNVs), small insertions/deletions (indels), and to a limited extent, copy number variations (CNVs) [42]. The fundamental premise of WES rests on its ability to provide comprehensive genetic information across all known genes without the excessive data burden and cost associated with whole genome sequencing (WGS), positioning it as a balanced solution for large-scale genomic studies [43].

In oncology research, WES has emerged as a particularly valuable tool for characterizing the mutational landscape of tumors. Unlike targeted gene panels that focus on predetermined genomic regions, WES allows for hypothesis-free exploration of all protein-coding sequences, enabling discovery of novel cancer-associated genes and pathways [4]. This agnostic approach is especially relevant for TMB assessment, which requires quantitative measurement of somatic mutations across a broad genomic territory to accurately estimate neoantigen load and predict immunotherapy responsiveness [4] [44].

WES as Gold Standard for Tumor Mutational Burden Assessment

TMB Definition and Clinical Significance

Tumor mutational burden refers to the number of somatic mutations per megabase of interrogated genomic sequence [4]. As a quantitative biomarker, TMB reflects the mutational accumulation within a tumor, which subsequently influences the generation of immunogenic neoantigens presented on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules [4]. These neoantigens enable the immune system to recognize and target tumor cells, providing the mechanistic rationale for the observed correlation between high TMB and improved response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) across multiple cancer types [4] [7].

The clinical validation of TMB as a predictive biomarker culminated in the 2020 FDA approval of pembrolizumab for solid tumors with TMB-high status (≥10 mutations/megabase), based on findings from the KEYNOTE-158 trial [4]. This regulatory milestone established TMB as a pan-cancer biomarker for immunotherapy selection, reinforcing the need for accurate and standardized TMB measurement in research and clinical contexts.

Experimental Protocols for TMB Measurement via WES

The established protocol for TMB assessment using WES involves a multi-step process that requires both tumor and matched normal DNA samples to distinguish somatic mutations from germline variants:

Sample Preparation and Sequencing

- DNA Extraction: Tumor DNA is typically isolated from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections, while normal DNA is obtained from peripheral blood, saliva, or adjacent normal tissue [44]. DNA quality and quantity are assessed using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay).

- Library Preparation: Fragmented DNA undergoes end-repair, adenylation, and adapter ligation. For WES, library preparation incorporates hybridization-based capture using biotinylated oligonucleotide probes that target the exonic regions (approximately 30-60 Mb) [4] [44].

- Sequencing: Captured libraries are sequenced on NGS platforms (e.g., Illumina HiSeq, NovaSeq) to achieve minimum coverage of 100-150x for tumor samples and 30-50x for normal samples [44].

Bioinformatic Analysis

- Alignment: Sequencing reads are aligned to the reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using tools such as BWA-MEM [44].

- Variant Calling: Somatic variant calling identifies mutations present in tumor but not normal tissue using specialized algorithms (e.g., Mutect2, VarScan) [44]. The standard TMB calculation includes coding, non-synonymous mutations (missense, nonsense, indels) while typically excluding synonymous variants unless otherwise specified [4].

- TMB Calculation: The TMB value is derived using the formula:

TMB (mutations/Mb) = (Total number of somatic mutations) / (Size of the coding target region in Mb)

The coding target region for WES is approximately 30-38 Mb, though exact sizes vary by capture kit [4].

Table 1: Commercially Available Large Gene Panels for TMB Assessment

| Laboratory/Panel | Number of Genes | Total Region Covered (Mb) | TMB Region Covered (Mb) | Mutation Types Included |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FoundationOne CDx | 324 | 2.20 | 0.80 | Non-synonymous, synonymous |

| MSK-IMPACT | 468 | 1.53 | 1.14 | Non-synonymous |

| TruSight Oncology 500 | 523 | 1.97 | 1.33 | Non-synonymous, synonymous |

| Oncomine TML Assay | 409 | 1.70 | 1.20 | Non-synonymous |

| TEMPUS Xt | 595 | 2.40 | 2.40 | Non-synonymous |

Source: Adapted from Merino et al. as cited in [4]

Comparative Performance of WES and Targeted Panels

While WES remains the gold standard for TMB measurement in research settings, targeted sequencing panels have gained traction in clinical practice due to practical advantages including lower cost, faster turnaround time, and reduced DNA input requirements [4]. Validation studies demonstrate that large panels (>1 Mb) show strong correlation with WES-derived TMB values, with reported Pearson correlation coefficients ranging from R=0.94 to R=0.98 [44]. However, this correlation strength is highly dependent on panel size and design, with smaller panels showing greater variability, particularly for intermediate TMB values [4].

The precision of TMB estimation improves with larger genomic regions, as the coefficient of variation decreases proportionally with the square root of both panel size and TMB level [4]. This relationship underscores the statistical advantage of WES for TMB quantification, as its larger target size (∼30 Mb versus 0.8-2.4 Mb for panels) provides more stable mutation counts, especially critical for tumors with intermediate TMB levels where clinical classification thresholds have significant therapeutic implications [4] [44].

Technical Limitations of Whole Exome Sequencing

Incomplete Exome Coverage and Capture Efficiency

Despite comprehensive target design, WES does not achieve complete coverage of all exonic regions due to technical limitations in capture efficiency and sequence context challenges:

- Regional Gaps: Current WES technologies typically capture approximately 97% of exons, with about 10% of exonic regions failing to achieve sufficient coverage depth (>20x) to reliably call heterozygous variants [43] [45]. These coverage gaps result from difficulties in capturing regions with extreme GC content, repetitive sequences, or homologous pseudogenes [43] [42].

- Capture Variability: Probe design limitations and hybridization efficiency variations create uneven coverage across the exome, with some clinically relevant genes exhibiting consistently poor capture [43]. This variability necessitates additional validation for genes of interest in specific research contexts.

- Comparative Performance: Interestingly, WGS has demonstrated more complete coverage of the exome than WES itself, highlighting a paradoxical limitation of exome-focused approaches [43].

Restricted Variant Detection Capability

WES is fundamentally limited in its ability to detect important classes of genomic alterations:

- Structural Variants: WES has low sensitivity for detecting structural variations including copy number variants (CNVs), inversions, and translocations [43] [42]. While some CNVs can be inferred from exome data, this requires specialized analytical approaches and remains inferior to detection by WGS or chromosomal microarrays [43] [46].

- Non-Coding Variants: By design, WES excludes the approximately 99% of the genome comprising non-coding regions, including regulatory elements, enhancers, and non-coding RNAs that increasingly demonstrate clinical significance in cancer [43] [46]. For example, non-coding regulatory variants have been shown to explain the majority of cases in TAR syndrome [43].

- Repeat Expansions: WES cannot reliably detect repeat expansion disorders (e.g., Huntington's disease) or other large repetitive elements that require specialized molecular techniques for accurate characterization [43] [46].

- Mitochondrial Genome: Standard WES protocols do not consistently cover the mitochondrial genome, necessitating separate assessment for mitochondrial DNA mutations [45].

Table 2: Variant Types and Their Detectability by Whole Exome Sequencing

| Variant Type | Detectable by WES | Detection Efficiency | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Nucleotide Variants | Yes | High | Affected by regional coverage gaps |

| Small Insertions/Deletions | Yes | Moderate-High | Size limitations (<50bp) |

| Copy Number Variants | Limited | Low | Inference-based, high false-negative rate |

| Structural Variants | No | Not applicable | Requires long-read or specialized technologies |

| Non-Coding Variants | No | Not applicable | By design exclusion |

| Repeat Expansions | No | Not applicable | Requires repeat-primed PCR or long-read sequencing |

| Mitochondrial DNA Variants | Variable | Low | Inconsistent coverage in standard kits |

Analytical and Interpretation Challenges

The analytical pipeline for WES introduces additional layers of complexity that impact result reliability:

- Germline Contamination: In tumor-only sequencing designs, incomplete filtering of germline variants inflates TMB estimates by 3.9-5.8 mutations/Mb on average, potentially leading to false-positive TMB-high classifications [44]. This underscores the necessity for matched normal sequencing in research settings requiring accurate TMB quantification.

- Artifact Management: FFPE-derived DNA exhibits characteristic artifactual mutations resulting from cytosine deamination, oxidation, and other damage processes that must be distinguished from true somatic variants through specialized bioinformatic filters [44].

- Variant Interpretation: The extensive dataset generated by WES (approximately 50,000 variants per exome) creates challenges in prioritizing clinically relevant mutations, particularly for variants of uncertain significance (VUS) that require functional validation [41] [42].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for WES-Based TMB Analysis

| Category | Product/Platform | Specifications | Research Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capture Kits | Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon V6 | ~60 Mb target size | Comprehensive exome capture for TMB reference standard |

| Illumina Nexome | ~40 Mb target size | Streamlined exome sequencing with integrated analysis | |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | High-throughput, 20B reads/flow cell | Large cohort TMB studies |

| Illumina NextSeq 550 | Mid-throughput, 400M reads/flow cell | Moderate-scale TMB validation | |

| Bioinformatic Tools | GATK Mutect2 | Somatic variant caller | Standardized somatic mutation detection |

| BWA-MEM | Sequence aligner | Reference genome alignment | |

| Ion Reporter | Integrated analysis suite | Variant annotation and TMB calculation | |

| Reference Materials | Horizon TMB Reference Standard | Certified mutation load | Assay validation and QC |

| Coriell Institute DNA | Characterized biobank samples | Process control and reproducibility |

Whole exome sequencing maintains its position as the gold standard for tumor mutational burden assessment in research settings, providing comprehensive mutation profiling across protein-coding regions that enables robust correlation between mutational load and immunotherapy response. Its extensive target space offers statistical advantages over targeted panels for TMB quantification, particularly for tumors with intermediate mutation burdens where precise classification carries significant therapeutic implications.

However, researchers must acknowledge and address the technical limitations inherent to WES methodology, including incomplete exome coverage, inability to detect important variant classes such as structural variants and non-coding regulatory mutations, and analytical challenges in distinguishing true somatic events from germline polymorphisms and technical artifacts. These constraints necessitate complementary approaches—including WGS, transcriptomic analysis, and specialized structural variant detection—for comprehensive cancer genomic profiling.