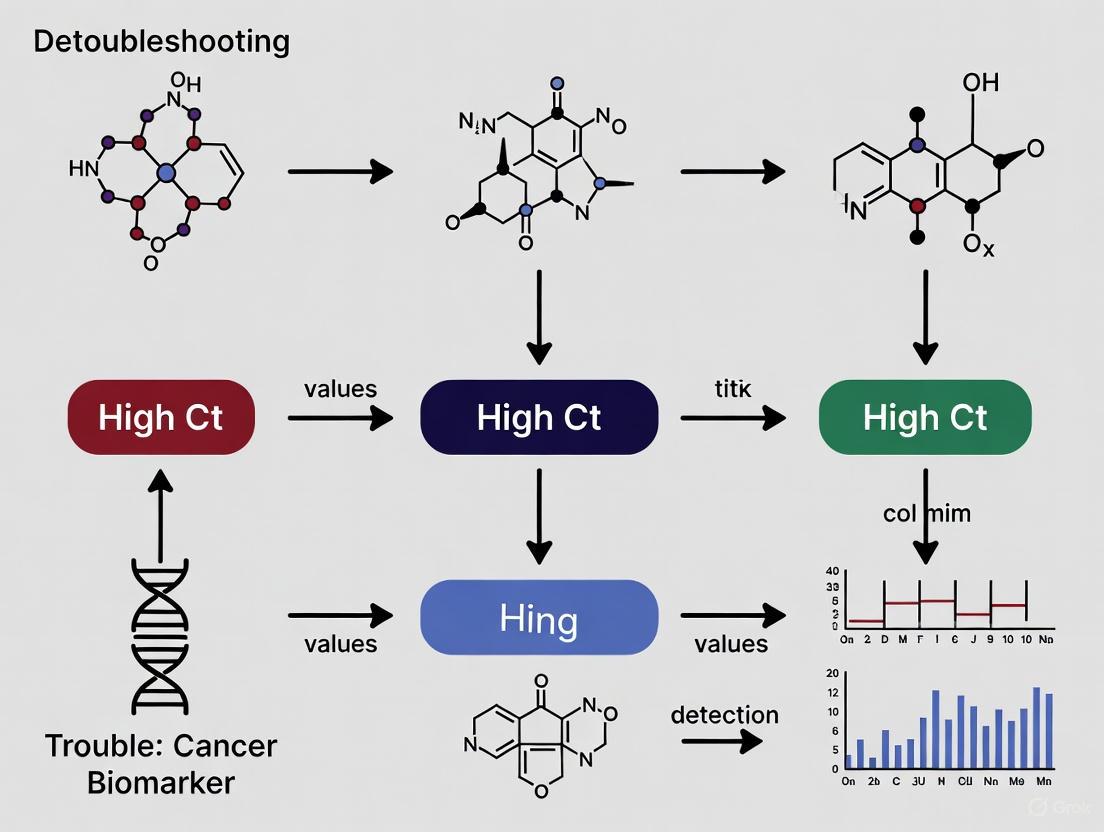

Troubleshooting High Ct Values in Cancer Biomarker Detection: A Strategic Guide for Robust qPCR and dPCR Results

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing the challenge of high cycle threshold (Ct) values in the detection of low-abundance cancer biomarkers.

Troubleshooting High Ct Values in Cancer Biomarker Detection: A Strategic Guide for Robust qPCR and dPCR Results

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing the challenge of high cycle threshold (Ct) values in the detection of low-abundance cancer biomarkers. Covering foundational principles to advanced validation, we explore the biological and technical origins of high Ct values, examine cutting-edge methodologies like digital PCR and next-generation sequencing that enhance sensitivity, detail systematic troubleshooting protocols for pre-analytical, analytical, and post-analytical phases, and establish rigorous frameworks for assay validation and performance benchmarking. By integrating insights from recent advancements in multi-omics and artificial intelligence, this resource aims to empower the development of reliable, clinically translatable biomarker assays for early cancer detection and personalized therapy.

Decoding High Ct Values: Biological and Technical Foundations in Cancer Biomarker Research

What is a Ct Value? The Threshold cycle (Ct) value is a critical metric in real-time PCR (qPCR) that indicates the PCR cycle number at which the fluorescence signal from amplification exceeds a predefined threshold, signifying the detection of the target sequence [1]. This value is central to both qualitative and quantitative analysis, as it is inversely correlated with the starting quantity of the target nucleic acid in the sample; a lower Ct value indicates a higher initial concentration of the target [1].

How is a Ct Value Determined? The determination of a Ct value follows a systematic process [1]:

- Amplification Plot: The real-time PCR instrument generates a plot of fluorescence (ΔRn) versus cycle number.

- Baseline Subtraction: The baseline fluorescence from early cycles is subtracted to normalize the data.

- Threshold Setting: A fluorescence threshold is set within the exponential phase of amplification. This threshold must be above the baseline but within the linear range of the plot to ensure precision and avoid high variability areas.

- Ct Calculation: The Ct value is the cycle at which the amplification curve intersects the threshold.

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between the amplification curve, the threshold, and the Ct value.

The Critical Link Between Ct Values and Low-Abundance Biomarker Detection

In cancer biomarker research, targets like circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and microRNA (miRNA) are often present in exceptionally low concentrations. ctDNA, for instance, can constitute less than 1% of the total cell-free DNA in early-stage cancer, making it a classic low-abundance target [2]. The detection of these biomarkers pushes qPCR technology to its sensitivity limits, directly resulting in high Ct values.

Why does this happen?

- Low Starting Concentration: The fundamental principle of qPCR is that the Ct value is a reflection of the initial target quantity. A scarce target, such as a specific ctDNA mutation or a miRNA molecule, requires more amplification cycles to generate a detectable fluorescent signal. This naturally leads to a high Ct value [1].

- Biomarker-Specific Challenges: ctDNA is not only low in concentration but also highly fragmented, which can further complicate primer and probe binding, potentially reducing assay efficiency and contributing to higher Ct values or false negatives [3] [4].

Consequently, a high Ct value in this context is a direct technical challenge. It operates at the limit of the assay's detection capability, where factors like background noise, inhibitors, and subtle efficiency losses have a magnified impact, threatening the reliability of the result.

Systematic Troubleshooting Guide for High Ct Values

When encountering high Ct values in the detection of ctDNA or miRNA, a systematic investigation is required. The following workflow outlines a step-by-step troubleshooting process, from sample preparation to data analysis.

Step 1: Assess Sample Quality and Nucleic Acid Integrity

- Problem: Degraded or poorly handled samples, especially with fragile targets like miRNA or fragmented ctDNA, are a primary cause of high Ct values.

- Solutions:

- Use Fresh or Properly Preserved Samples: For blood-based ctDNA, use specialized collection tubes that stabilize nucleated cells and prevent background DNA release. Process plasma within a few hours of collection [2].

- Verify Extraction Method: Ensure the nucleic acid extraction kit is validated for your specific biomarker type (e.g., small RNAs for miRNA, or short fragmented DNA for ctDNA). Manually check RNA Integrity Numbers (RIN) or DNA fragment size distribution if possible.

Step 2: Check Nucleic Acid Quantity and Purity

- Problem: Inaccurate quantification or the presence of inhibitors co-purified during extraction can severely hamper PCR efficiency.

- Solutions:

- Quantify with Fluorescence-based Methods: Avoid spectrophotometry (A260/A280) for low-concentration samples, as it is insensitive to degradation and can be skewed by contaminants. Use fluorescence dyes (e.g., Qubit, PicoGreen) that specifically bind to nucleic acids for accurate concentration measurement.

- Perform Dilution Test: Dilute the sample 1:5 and re-run the assay. If the Ct value decreases linearly with dilution, it suggests the presence of PCR inhibitors in the original sample. Re-purify the nucleic acid or use a cleaner extraction method.

Step 3: Verify Reaction Efficiency and Inhibition

- Problem: Suboptimal PCR efficiency, often caused by poor primer/probe design or reaction conditions, prevents robust amplification of low-abundance targets.

- Solutions:

- Run a Standard Curve: Prepare a 10-fold serial dilution of a known positive control or synthetic template. The ideal standard curve has a slope of -3.32, which corresponds to 100% PCR efficiency. A slope between -3.6 and -3.1 (90%-110% efficiency) is generally acceptable. A slope outside this range indicates poor efficiency that must be addressed [5].

- Use Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): For ultra-rare targets like ctDNA, incorporate UMIs during reverse transcription or library preparation. UMIs tag individual molecules, allowing bioinformatic correction of PCR amplification biases and errors, leading to more accurate quantification at high Ct values [2].

Step 4: Optimize Assay Design and Thermocycling Conditions

- Problem: Even a well-designed assay may require fine-tuning for maximum sensitivity against challenging backgrounds.

- Solutions:

- Validate Primer/Probe Specificity: Use tools like BLAST to check for off-target binding. For miRNA, ensure the assay can discriminate between highly homologous family members.

- Consider Probe Chemistry: TaqMan probes are highly specific due to the 5' nuclease activity, reducing background and improving signal-to-noise ratio for low-level targets [5].

- Optimize Annealing Temperature: Perform a temperature gradient PCR to determine the optimal annealing temperature for your primer pair, which maximizes specific product yield.

Step 5: Validate with Appropriate Controls

- Problem: Without proper controls, it is impossible to distinguish between a true negative, a failed reaction, or a false negative due to a high Ct value.

- Solutions:

- Include a Positive Control: Use a synthetic oligonucleotide or a known positive sample at a concentration expected to yield a high Ct value (e.g., Ct 35-38). This verifies that the assay can detect low levels of the target under the current run conditions.

- Use a Internal Control: Spike-in a known amount of an exogenous control (e.g., synthetic non-human RNA or DNA) into each sample during lysis. A high Ct or failure for the spike-in control indicates a problem with the reaction itself (e.g., inhibition), invalidating a negative result for the target [1] [6].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the maximum acceptable Ct value for a result to be considered reliable? There is no universal maximum Ct value. The cutoff is determined by assay validation. You must establish the Limit of Detection (LoD) for your specific assay by testing replicates of a known positive control at low concentrations. The LoD is typically the concentration at which 95% of the replicates are detected. Any result with a Ct value above the LoD's average Ct should be considered non-detectable or indeterminate. For clinically validated tests, this cutoff is strictly defined [6].

Q2: My negative control shows a Ct value. What does this mean? A Ct value in your no-template control (NTC) indicates contamination.

- If the NTC Ct is high (e.g., >38): This suggests low-level contamination, likely from amplicon carryover or contaminated reagents. You should discard the affected reagents, clean workspaces and equipment, and repeat the experiment.

- If the NTC Ct is low: This indicates significant contamination, and all results from the run are invalid. A systematic decontamination of your workflow is required.

Q3: How should I handle high Ct value data in my quantitative analysis? Exercise extreme caution. The widely used 2−ΔΔCT method assumes 100% PCR efficiency, an assumption that often breaks down in later cycles where efficiency can drop, making quantification at high Ct values inaccurate [7] [5]. For relative quantification, it is better to treat samples with very high Ct values as "non-detected" rather than assigning a numerical value. For absolute quantification, ensure your standard curve covers the high Ct range and that the linearity and efficiency are maintained in that region. Advanced statistical models like ANCOVA are recommended over the 2−ΔΔCT method for more robust analysis, especially when efficiency is not perfect [7].

Q4: Are there alternatives to qPCR for detecting targets that consistently yield high Ct values? Yes, more sensitive technologies are available:

- Digital PCR (dPCR): This method partitions a sample into thousands of individual reactions, allowing for absolute quantification without a standard curve. It is significantly more sensitive and robust for detecting rare targets like ctDNA mutations and can reliably detect sequences that yield Ct values >35 in qPCR [2] [5].

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Especially when using error-corrected sequencing methods (e.g., duplex sequencing), NGS can detect very low-frequency mutations with high specificity, overcoming the limitations of qPCR for complex, low-abundance biomarker detection [4] [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents and materials critical for optimizing assays designed to detect low-abundance biomarkers.

| Item | Function & Importance in Low-Abundance Detection |

|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Stabilization Tubes | Preserves sample integrity from the moment of collection, preventing dilution of ctDNA or miRNA by background genomic DNA release from white blood cells [2]. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits (Size-Selective) | Designed to efficiently recover short, fragmented nucleic acids like ctDNA and miRNA, maximizing the yield of the target biomarker [3]. |

| Fluorometric Quantitation Kits | Provides accurate concentration measurements of precious, low-yield samples, which is critical for normalizing input material and avoiding false negatives [7]. |

| TaqMan Assays | The probe-based chemistry offers high specificity, reducing false positives from non-specific amplification, which is crucial when signal is near the background level [1] [5]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Tags individual molecules before amplification, enabling accurate counting and correction for PCR errors and biases, essential for quantifying rare variants [2]. |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) Reagents | Provides an absolute and highly sensitive quantification method, partitioning the sample to overcome PCR inhibition and detect rare targets with superior precision compared to qPCR [2] [5]. |

| Standard Curves & Positive Controls | Validates assay performance, defines the LoD, and is essential for accurate absolute quantification. A low-concentration positive control is vital for verifying high-Ct detection capability [6] [5]. |

FAQs on High Ct Values in Cancer Biomarker Detection

What biological factors can cause high Ct values in ctDNA detection assays?

High Ct values in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) detection can often be attributed to biological characteristics of the tumor itself rather than technical assay failure. The primary biological sources are low tumor DNA shedding and high molecular fragmentation.

Table 1: Biological Factors Contributing to High Ct Values

| Biological Factor | Impact on Ct Value | Underlying Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Low Tumor Shedding | Increases Ct (less template) | Some tumors release minimal DNA into circulation regardless of size [8] [2] |

| Apoptotic DNA Release | Variable impact | Produces short, fragmented DNA (~167 bp) which may be suboptimal for some assays [8] [9] |

| Necrotic DNA Release | Can improve signal | Releases longer DNA fragments; more prevalent in advanced/aggressive tumors [8] |

| Tumor Heterogeneity | Increases variability | Subclones with different shedding rates create fluctuating ctDNA levels [2] |

| Rapid ctDNA Clearance | Increases Ct | Short half-life (16 min to several hours) means levels can change rapidly [2] |

The amount of ctDNA in a patient's blood does not always correlate directly with tumor size. Some tumors are inherently "low-shedders," releasing minimal DNA into circulation, which directly reduces the template available for PCR amplification and results in higher Ct values [8] [2]. Furthermore, the mechanism of cell death affects the quality of the DNA; apoptosis produces short, nucleosome-bound fragments (~167 bp), while necrosis releases longer fragments. The fragmentation pattern of ctDNA can be more complex in cancer patients, and these shorter fragments may not be efficiently detected by all assay designs [8] [9].

How does tumor heterogeneity impact ctDNA levels and detection sensitivity?

Tumor heterogeneity profoundly affects ctDNA detection by creating a dynamic and variable pool of circulating DNA. Spatial heterogeneity means that different regions of a tumor, or different metastatic sites, may shed DNA at different rates [2]. Temporal heterogeneity refers to the evolution of the tumor over time, especially under treatment pressure, where subclones with different genetic profiles and shedding characteristics may emerge [2]. This can lead to inconsistent ctDNA levels and unexpected fluctuations in Ct values across longitudinal monitoring.

What methodologies can improve detection sensitivity for low-abundance ctDNA?

Overcoming the challenge of low-abundance ctDNA requires highly sensitive techniques and optimized workflows. Key methodological approaches include digital PCR (dPCR) and next-generation sequencing (NGS) with error correction.

Digital PCR (dPCR): This method partitions a single PCR reaction into thousands of nanoreactions, allowing for absolute quantification and detection of rare mutations present at very low frequencies (<0.1%) [2]. It is highly sensitive for tracking known mutations.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Targeted NGS panels allow for the simultaneous tracking of multiple patient-specific mutations, providing a more comprehensive view of the tumor burden. To overcome sequencing errors that obscure true low-frequency variants, methods incorporating Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) are essential [2]. UMIs are molecular barcodes tagged onto DNA fragments before amplification, enabling bioinformatic filtering of PCR and sequencing errors. Advanced techniques like Duplex Sequencing provide the highest accuracy by sequencing both strands of the DNA duplex [2].

Fragmentation Pattern Analysis: Exploiting the unique size profile of ctDNA can enhance sensitivity. ctDNA fragments are often shorter than non-tumor cfDNA. Bioinformatic filtering for shorter fragments can effectively enrich the tumor-derived signal [8] [2].

Table 2: Experimental Protocols for Sensitive ctDNA Detection

| Method | Key Procedural Steps | Advantage for Low Abundance |

|---|---|---|

| Digital PCR (dPCR) | 1. Partition sample into thousands of droplets/nanowells.2. Perform endpoint PCR amplification.3. Count positive and negative partitions to calculate absolute concentration. | High sensitivity for known single mutations; ideal for monitoring MRD [2]. |

| NGS with UMIs | 1. Ligate UMIs to each DNA fragment during library prep.2. Perform deep sequencing (>10,000x coverage).3. Bioinformatically group reads by UMI to create consensus sequences and remove errors. | Broad panel allows multi-target tracking; error correction reduces false positives [2]. |

| Size Selection | 1. Extract plasma cfDNA.2. Perform gel electrophoresis or use automated size selection.3. Isolate DNA fragments in the 90-150 bp range for library construction. | Physically enriches for ctDNA by removing longer, non-tumor DNA fragments [8]. |

What are the technical versus biological root causes of high Ct values I should investigate?

A systematic investigation is crucial to diagnose the cause of high Ct values. The following workflow outlines a step-by-step troubleshooting guide to distinguish between technical and biological causes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for ctDNA Analysis

| Item | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free DNA BCT Tubes | Stabilizes blood samples to prevent white blood cell lysis and background cfDNA release. | Critical for pre-analytical phase; prevents false elevation of wild-type DNA [2]. |

| dPCR Master Mix | Provides reagents for highly sensitive partitioned PCR. | Select mixes designed for detecting rare variants in a high-background wild-type DNA. |

| UMI Adapter Kits | Adds unique molecular barcodes to each DNA fragment during NGS library preparation. | Essential for error correction in NGS-based ctDNA assays [2]. |

| Methylation-Specific Enzymes | Enzymes (e.g., for bisulfite-free conversion) to analyze ctDNA methylation patterns. | Provides an orthogonal method for detecting tumor DNA via epigenetic signatures [8]. |

| iRT Standard Peptides | For retention time calibration in LC-MS workflows, ensuring consistent peptide identification. | A key QC component in proteomic analyses of related biomarkers [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are pre-analytical variables and why do they matter for my qPCR results? Pre-analytical variables are all the steps that occur before the sample is analyzed, including collection, handling, transportation, stabilization, and storage. These steps are critical because studies show that 60-70% of all laboratory errors originate in the pre-analytical phase [11] [12]. Compromises during these stages can lead to nucleic acid degradation or the introduction of inhibitors, directly causing high Ct values, failed assays, and unreliable data in cancer biomarker detection.

2. I used a good extraction kit, but my RNA quality is still poor. What could have gone wrong? The quality of your starting material is the foundation for success. Even the best extraction kit cannot fully recover degraded nucleic acids. Key factors affecting quality include:

- Cold Ischemia Time: The time between tissue collection and preservation should be minimized (e.g., less than 1 hour for DNA PCR analysis) to prevent rapid RNA degradation by cellular nucleases [11].

- Fixation Type and Time: For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, fixation in neutral buffered formalin for less than 72 hours is optimal. Prolonged fixation or use of unbuffered formalin causes nucleic acid fragmentation and cross-linking [11].

- Immediate Stabilization: For RNA work, samples should be immediately stabilized using reagents like RNAlater or through flash-freezing to halt nuclease activity [13].

3. My DNA concentrations measure fine, but my NGS results are poor. Why? Spectrophotometric methods (like Nanodrop) measure the concentration of all nucleic acids but do not assess integrity or the presence of inhibitors. Degraded or fragmented DNA, even in sufficient concentration, leads to inefficient library preparation during NGS. One study of FFPE tissues showed that samples with high DNA integrity had an NGS success rate of ~94%, which dropped to ~5.6% for low-integrity samples [14]. Always use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) and integrity assessment (e.g., TapeStation, Bioanalyzer) for sequencing applications [14].

4. How do freeze-thaw cycles affect my samples? Repeated freeze-thaw cycles progressively degrade nucleic acids and proteins. Each cycle causes physical shearing and can lead to inconsistent results between experiments. It is crucial to aliquot samples into single-use volumes to minimize freeze-thaw cycles [14] [12].

5. My Ct values are consistently high (>35) across multiple assays. What is the first thing I should check? The first and most critical step is to check the quality and integrity of your input nucleic acids [15]. High Ct values are often a direct result of degraded RNA/DNA or the presence of PCR inhibitors carried over from the sample or extraction process [16] [17]. Running your samples on a quality control instrument (e.g., Bioanalyzer) to determine the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or DNA Integrity Number (DIN) is the most effective diagnostic step.

Sample-Specific Collection & Storage Guidelines

The table below summarizes evidence-based recommendations for handling common sample types to preserve nucleic acid integrity for downstream molecular assays, including cancer biomarker detection.

Table 1: Pre-analytical Guidelines for Common Sample Types in Cancer Research

| Specimen Type | Target | Short-Term Storage | Maximum Recommended Duration | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Blood | DNA | Room Temperature (RT) or 2-8°C | 24h (RT), 72h (2-8°C) [11] | For RNA, use specialized RNA stabilization tubes (e.g., PAXgene, Tempus) [13]. |

| Plasma | Cell-free DNA (e.g., ctDNA) | 4°C or -20°C | 5 days (4°C), longer at -20°C [11] | Centrifuge soon after collection to separate plasma from cells. Critical for liquid biopsies [18]. |

| Tissue (Fresh) | DNA/RNA | Snap-freeze in liquid N₂ or place in RNAlater | Immediately | Minimize cold ischemia time. RNAlater allows for storage at 4°C for 24h before long-term storage [11] [13]. |

| FFPE Tissue | DNA/RNA | Room Temperature | Years (with degradation) | Limit formalin fixation to 6-72 hours in neutral buffered formalin [11]. |

| Stool | DNA | RT or 4°C | 4h (RT), 24-48h (4°C) [11] | For microbiome studies, use preservative kits to stabilize microbial community DNA. |

| Swabs (e.g., Cervical) | DNA | 2-8°C | Up to 10 days [11] | Store in appropriate viral transport medium (VTM). |

Troubleshooting Guide: High Ct Values in qPCR

High Ct values indicate delayed amplification, meaning it takes many cycles to detect the signal. This is a common problem in cancer biomarker research, often rooted in pre-analytical issues. The following workflow and table guide you through a systematic diagnosis.

Troubleshooting High Ct Values

Table 2: Diagnosing and Resolving Common Causes of High Ct Values

| Problem | Root Cause | Solution | Preventive Measure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Degradation | Extended cold ischemia; improper fixation; repeated freeze-thaw; nuclease contamination. | Re-extract from original sample if possible. For FFPE, use protocols designed for cross-linked nucleic acids. | Minimize time to preservation; use nuclease-free consumables; aliquot samples [11] [14]. |

| PCR Inhibition | Carryover of salts, phenol, ethanol, heparin, or humic acids from the sample or extraction. | Perform a nucleic acid clean-up (e.g., column-based purification, ethanol precipitation). Add a dilution series of your template to detect inhibition [16] [14]. | Ensure complete removal of wash buffers; use high-quality, inhibitor-free reagents; include a sample pre-wash step for complex matrices [14]. |

| Suboptimal Primer/Probe | Primer-dimer formation; non-specific binding; secondary structures. | Redesign primers using specialized software. Optimize annealing temperature via gradient PCR [16]. | Validate all primer sets with a positive control template before using on experimental samples. |

| Template Overload | Excess template DNA can scatter primers and probes, delaying specific binding. | Dilute the sample template (10x to 1000x) and re-run the assay [17]. | Perform accurate fluorometric quantification and establish a standard curve for optimal template input. |

| Low RNA Quality | RNA degradation during handling (very common). | Check RIN value; for degraded RNA, use a 3'-end sequencing method like BRB-seq, which is tolerant of lower RIN values [13]. | Immediately preserve samples in RNAlater or flash-freeze in liquid nitrogen [13]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key reagents and tools that are fundamental for maintaining nucleic acid integrity throughout the pre-analytical phase.

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Pre-Analytical Workflows

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| RNAlater Stabilization Solution | Rapidly permeates tissues to inactivate RNases, preserving RNA at room temp for short periods. | Ideal for field collection or when immediate freezing is impractical. Minimizes need for flash-freezing [13]. |

| PAXgene / Tempus Blood RNA Tubes | Specialized blood collection tubes containing reagents that stabilize RNA at the point of draw. | Critical for reliable gene expression studies from whole blood; prevents changes in transcript profiles [13]. |

| Neutral Buffered Formalin (NBF) | The recommended fixative for tissue histology and molecular pathology. Prevents acid-induced nucleic acid degradation. | Always prefer NBF over unbuffered formalin. Limit fixation time to under 72 hours for optimal DNA recovery [11]. |

| Magnetic Bead-Based Kits | For automated nucleic acid extraction. Provide high consistency and reduce hands-on time/cross-contamination. | Platforms like the Thermo Fisher KingFisher offer reproducible yields and are effective for high-throughput labs [14]. |

| Qubit Fluorometer & Assays | Provides highly accurate, dye-based quantification of DNA/RNA, specific for double-stranded DNA or RNA. | Essential for NGS. Prefer over spectrophotometry for library preparation to avoid concentration inaccuracies [14]. |

| Automated Liquid Handler (e.g., I.DOT) | Non-contact, tipless dispenser for nanoliter volumes. Reduces pipetting error and cross-contamination. | Improves accuracy and reproducibility of qPCR assays by ensuring consistent reagent volumes [16]. |

Limitations of Traditional Biomarkers and the Need for Advanced Detection Platforms

Cancer biomarkers are biological molecules, such as proteins, genes, or metabolites, that can be objectively measured to indicate the presence, progression, or behavior of cancer. They are indispensable in modern oncology for early detection, diagnosis, treatment selection, and monitoring of therapeutic responses [19]. However, traditional biomarkers often disappoint due to significant limitations in their sensitivity and specificity, resulting in overdiagnosis and/or overtreatment in patients [19].

For instance, Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) levels can rise due to benign conditions like prostatitis, leading to false positives and unnecessary invasive procedures. Similarly, CA-125 is not exclusive to ovarian cancer and can be elevated in other cancers or non-malignant conditions [19]. Furthermore, many established biomarkers do not emerge until the cancer is already advanced, reducing their value in early detection [19]. These shortcomings highlight the urgent need for more reliable screening tools and advanced detection platforms.

★ FAQs on Traditional Biomarker Limitations

1. What are the main limitations of traditional protein biomarkers like PSA and CA-125?

The primary limitations are poor sensitivity and specificity. These biomarkers are not exclusive to cancer, as their levels can be elevated in various benign conditions. This lack of specificity often leads to false positives, unnecessary invasive procedures, and patient anxiety [19]. Additionally, their sensitivity for early-stage disease is frequently low, meaning they often fail to detect cancer in its most treatable stages.

2. Why are single-biomarker tests increasingly being replaced?

There is a growing realization that biomarker panels or profiling is more valuable in cancer testing and personalized management than single-biomarker assessments [19]. Cancer is a complex and heterogeneous disease; a single molecule is often insufficient to capture its full biological reality. Multi-analyte panels that combine DNA mutations, methylation profiles, and protein biomarkers have demonstrated a superior ability to detect cancer simultaneously, with encouraging sensitivity and specificity [19].

3. What pre-analytical factors most commonly cause biomarker test failures?

Pre-analytical causes account for about 90% of all failed next-generation sequencing (NGS) cases. A study of 1,528 specimens found that 22.5% failed testing, with 65% of failures due to insufficient tissue and 28.9% due to insufficient DNA [20]. Factors strongly associated with failure include:

- Site and type of biopsy

- Clinical setting (initial diagnosis vs. recurrence)

- Age of the specimen and tumor viability [20]

Table 1: Factors Associated with Failed NGS Testing in a 1528-Specimen Cohort [20]

| Failure Category | Percentage of All Failures | Primary Associated Factors |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Tissue (INST) | 65% (223/343) | Site of biopsy, Type of biopsy, Clinical setting, Age of specimen, Tumor viability |

| Insufficient DNA (INS-DNA) | 28.9% (99/343) | Site of biopsy, Type of biopsy, Clinical setting, DNA purity, DNA degradation |

| Failed Library (FL) | 6.1% (21/343) | DNA purity, DNA degradation, Type of biopsy |

★ Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing High Ct Values in Biomarker Detection

A high Cycle Threshold (Ct) value in quantitative PCR (qPCR) indicates delayed amplification and low template quality or quantity. This is a common challenge when detecting scarce biomarkers, such as in liquid biopsies.

Problem: Ct values are higher than usual (>35) or undetectable in my qPCR-based biomarker assay.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Cause 1: Poor Template Quality or Quantity

- Solution: Check RNA/DNA quality using recommended quality control checks. Use more input total RNA/DNA, or use the template at a lower dilution factor [15]. For DNA, ensure the input is within the functional range (e.g., 100 ng to 1 ng for gDNA); higher Ct values may indicate poor quality, degraded DNA, or inhibitors [21].

Cause 2: Excess Template or Inhibitors

Cause 3: Low or No Expression of Target

- Solution: The corresponding gene may not be expressed above the limit of detection. Use a template known to contain the gene of interest as a positive control to troubleshoot the PCR reagents and experimental procedure [15].

Table 2: Troubleshooting High Ct Values in qPCR Experiments

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| High Ct (>35) in all samples, including positive control | Inefficient reaction setup, degraded reagents | Prepare fresh reagents, run a new standard curve, optimize primer concentrations |

| High Ct only in patient samples | Poor sample quality, presence of PCR inhibitors | Check nucleic acid quality (degradation), dilute sample to reduce inhibitors, purify sample |

| High Ct for one biomarker, others are normal | Low expression of that specific target or suboptimal assay | Validate assay with a known positive sample; consider using a more abundant biomarker |

| Undetermined Ct (not detectable) | Target absent or below detection limit, major reaction failure | Increase input of template RNA/DNA; use a more sensitive technology (e.g., digital PCR) |

★ Advanced Detection Platforms: Moving Beyond Tradition

To overcome the limitations of traditional biomarkers and the technical challenges of qPCR, the field is rapidly evolving towards more sophisticated, multi-omics platforms.

1. Liquid Biopsies and Circulating Biomarkers Liquid biopsies, which analyze circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), circulating tumor cells (CTCs), or exosomes from a blood sample, represent a non-invasive alternative to traditional tissue biopsies [19]. This method permits early detection and real-time monitoring. Key advancements include:

- Enhanced Sensitivity and Specificity: Advances in ctDNA analysis and exosome profiling are increasing the reliability of liquid biopsies for early disease detection and monitoring [22].

- Multi-Cancer Early Detection (MCED): Tests like the Galleri test, which analyzes ctDNA, are designed to detect over 50 cancer types simultaneously and are undergoing clinical trials [19].

2. Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and Multi-Omics NGS-based comprehensive genomic profiling allows for the simultaneous assessment of multiple biomarkers across many genes [19]. This is often coupled with multi-omics approaches that integrate genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and transcriptomics to achieve a holistic understanding of disease mechanisms [23] [22]. This shift toward systems biology promotes a deeper understanding of how different biological pathways interact in health and disease [22].

3. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning AI and ML are revolutionizing biomarker analysis by identifying subtle patterns in large, complex datasets that human observers might miss [19] [23]. These tools enable the integration of various molecular data types with imaging to enhance diagnostic accuracy and therapy recommendations [19]. AI-driven algorithms are being developed for predictive analytics, automated data interpretation, and personalized treatment plans [22].

★ The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Advanced Biomarker Detection

| Item | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits (e.g., QIAamp DNeasy) | Isolation of high-quality DNA/RNA from complex samples (FFPE, blood, stool) | Pre-analytical step for NGS or qPCR; critical for obtaining sufficient, non-degraded material [20] |

| Multiplex PCR Primer Panels | Simultaneous amplification of multiple biomarker targets in a single reaction | Targeted NGS panels for comprehensive cancer gene profiling; increases efficiency and reduces sample input requirements [19] [24] |

| TaqMan Mutation Detection Assays | Allele-specific PCR for detecting known somatic mutations with high specificity | Validated assays for detecting key oncogenic drivers like EGFR, KRAS, and BRAF mutations [21] |

| Synthetic RNA/DNA Controls | Precisely quantified external controls for standard curve generation and assay validation | Determining the limit of detection and ensuring run-to-run reproducibility in qPCR and NGS [24] |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq Kits | Profiling gene expression at the individual cell level | Uncovering tumor heterogeneity and identifying rare cell populations that drive disease [22] |

★ Experimental Protocol: Validating Novel mRNA Biomarkers from Stool for Colorectal Cancer Detection

The following workflow, derived from a 2025 study, details a robust method for identifying and validating novel mRNA biomarkers for detecting colorectal cancer (CRC) and advanced adenoma (AA) from stool samples [25]. This protocol exemplifies the multi-step process required to move from bioinformatic discovery to clinical validation.

Workflow for Stool mRNA Biomarker Validation

1. Bioinformatic Screening & Candidate Identification

- Data Acquisition: Download RNA-seq datasets from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) databases. A combined dataset of 478 colon cancer and 692 normal colon/rectum tissue samples was used [25].

- Data Processing: Perform batch correction to merge datasets using a tool like ComBat-seq. Conduct a differential expression analysis comparing CRC tissue to healthy tissue using edgeR [25].

- Gene Ranking: Rank genes based on stringent criteria:

- Statistical Significance: False discovery rate (FDR) < 0.001.

- Discriminatory Power: Area under the curve (AUC) > 0.9 when comparing CRC to healthy tissue.

- Magnitude of Change: Log2 fold-change > 2.

- Expression Level: High median expression in CRC tissue.

- Output: A prioritized list of candidate genes (e.g., the top 20) for experimental validation [25].

2. Wet-Lab Validation on Clinical Samples

- Sample Cohort: Procure a well-characterized set of clinical stool samples (e.g., 33 CRC, 28 Advanced Adenoma, 53 Controls) [25].

- RNA Extraction & QC: Extract total RNA from stool samples. This is a critical step due to the complex and inhibitory nature of the stool matrix. Perform rigorous quality control.

- qRT-PCR Analysis: Test the expression of the top candidate genes via qRT-PCR across the sample cohort.

3. Analytical and Clinical Validation

- Statistical Correlation: Calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient between tissue and stool expression levels for the candidates (r=0.57, p=0.007 in the source study) [25].

- Performance Assessment: Evaluate the diagnostic performance by calculating the Area Under the Receiver Operator Curve (AUC). The combined 20-gene panel achieved an AUC of 0.94 for detecting CRC and 0.83 for detecting AA [25].

Advanced Methodologies for Enhancing Sensitivity in Low-Abundance Biomarker Detection

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guide

This technical support resource addresses common challenges in liquid biopsy research, providing targeted solutions for issues related to circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), circulating tumor cells (CTCs), and exosomes, with a specific focus on troubleshooting high Ct values in cancer biomarker detection.

Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA)

FAQ: Why are my ctDNA assays yielding high Ct values or failing to detect known mutations?

High Ct values in ctDNA analysis typically indicate a low concentration of the target mutant DNA sequence relative to the wild-type background. This is a common challenge due to the inherent biological and technical complexities of working with ctDNA.

- Primary Cause: Low variant allele frequency (VAF), often below 0.1% in early-stage disease, is the most frequent cause [26] [27]. The amount of ctDNA can be vanishingly low, sometimes less than 1-100 copies per mL of plasma [27].

- Pre-analytical Factors: The use of improper blood collection tubes (e.g., regular EDTA tubes without rapid processing) can lead to genomic DNA contamination from lysed white blood cells, drastically diluting the ctDNA fraction [27]. Factors like recent physical exercise, surgical trauma, or underlying inflammatory conditions in the patient can also increase the background level of wild-type cell-free DNA [27].

Troubleshooting Guide for ctDNA Detection

| Challenge | Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Analytical Sensitivity | ctDNA concentration below assay detection limit [27]. | Use ultra-sensitive methods like droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) or ultra-deep next-generation sequencing (NGS) (>10,000x coverage) [28] [27]. |

| High Wild-Type Background | Contamination from lysed blood cells; patient's physiological condition [27]. | Use cell-stabilizing blood collection tubes (e.g., Streck cfDNA) and process plasma within 2-6 hours if using EDTA tubes [27]. |

| Pre-analytical DNA Degradation | Improple blood draw, handling, or storage [27]. | Use butterfly needles, avoid fine-gauge needles/prolonged tourniquet, and ensure immediate double-centrifugation for plasma separation [27]. |

| Rapid In Vivo Clearance | ctDNA is quickly eliminated by liver macrophages and nucleases [27]. | Research approaches to slow clearance (e.g., interfering with nucleases) are in development to increase yield [27]. |

Detailed Protocol: Optimized Plasma Collection for ctDNA Analysis

- Blood Draw: Use a 21-gauge butterfly needle and avoid prolonged tourniquet use to prevent hemolysis [27].

- Collection Tube: Draw a minimum of 10 mL of blood into cfDNA-specific BCTs (e.g., Streck, PAXgene). For EDTA tubes, process within 2-6 hours of collection [27].

- Plasma Separation: Perform a first centrifugation at 800-1600 RCF for 10 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma from cells.

- Plasma Clarification: Transfer the supernatant to a new tube and perform a second centrifugation at 16,000 RCF for 10 minutes to remove any remaining cellular debris.

- Storage: Aliquot the purified plasma and store at -80°C to prevent freeze-thaw cycles.

Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs)

FAQ: Why is my CTC yield low, and how can I improve capture efficiency and purity?

The extreme rarity and heterogeneity of CTCs make their isolation and detection technically demanding. Low yields can stem from both biological factors and limitations of the chosen isolation technology.

- Primary Cause: CTCs are exceptionally rare, with as few as 1 CTC per billion blood cells, and fewer than 1 CTC per 10 mL of blood in early-stage cancer [29]. Furthermore, CTCs undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), leading to loss of epithelial markers like EpCAM, which are used in many capture technologies [29] [30].

- Technical Challenges: The complex blood environment causes non-specific binding, creating high background noise. High shear stress during isolation can also damage CTCs, reducing recovery and viability for downstream culture [29].

Troubleshooting Guide for CTC Isolation

| Challenge | Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Extreme Rarity | Low abundance of CTCs in blood [29]. | Process larger blood volumes (≥10 mL); use technologies that enable high-throughput processing [29] [30]. |

| Tumor Heterogeneity | Loss of epithelial markers (e.g., EpCAM) due to EMT [29] [30]. | Combine size-based (e.g., microfilters) and label-based (e.g., antibody) methods; use multiple biomarkers (e.g., EpCAM, vimentin) [29] [30]. |

| Low Purity & Viability | Non-specific binding of blood cells; harsh isolation conditions [29]. | Use negative enrichment (CD45+ depletion) or antifouling surfaces; employ low-shear microfluidic devices (e.g., Chip-based systems) [29] [30]. |

| Technical Complexity | Lack of standardized protocols across platforms [29]. | Automate capture and analysis where possible; use preservative tubes for sample integrity during transport [29]. |

Detailed Protocol: Combined EpCAM and Size-Based CTC Enrichment This protocol leverages the CellSearch system for immunomagnetic enrichment followed by microfluidic filtration for high-purity recovery.

- Reagents: Anti-EpCAM coated magnetic beads, anti-cytokeratin (CK) antibodies, anti-CD45 antibodies, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), fluorescence mounting medium.

- Equipment: CellSearch system or equivalent immunomagnetic separator, microfluidic filtration device (e.g., porous membrane filter with 8 µm diameter pores), fluorescent microscope.

Workflow:

- Immunomagnetic Enrichment: Incubate 7.5-10 mL of blood with anti-EpCAM magnetic beads for 15 minutes at room temperature. Place the tube in a magnetic separator and discard the supernatant.

- Washing: Resuspend the bead-bound cells in PBS and place in the magnet again. Repeat washing twice to remove unbound cells.

- Microfluidic Filtration: Resuspend the enriched cell fraction in PBS and load into a size-based microfluidic device. Apply a low pressure to pass the suspension through the filter, retaining larger CTCs.

- Immunofluorescence Staining: Fix the cells on the filter and stain with anti-CK (FITC), anti-CD45 (PE), and DAPI.

- Identification and Enumeration: Identify CTCs as CK+/DAPI+/CD45- under a fluorescent microscope [30].

Exosomes

FAQ: Why is my exosome detection signal weak, and how can I improve sensitivity?

Weak signals often result from low purity of isolated exosomes, inefficient capture on the sensor surface, or suboptimal detection probes.

- Primary Cause: The nanoscale size of exosomes (typically 30-150 nm) and their low concentration in complex biological fluids pose significant challenges for sensitive detection [31] [32]. Inefficient isolation methods or the use of a single, non-specific biomarker can further reduce the signal.

- Technical Challenges: Commonly used methods like ultracentrifugation can co-isolate contaminants like lipoproteins, while immunoaffinity methods can be limited by antibody cost and stability [32].

Troubleshooting Guide for Exosome Detection

| Challenge | Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Abundance & Small Size | Target exosomes are present at low concentrations and are difficult to label [32]. | Use high-affinity capture probes (e.g., aptamers against CD63); employ signal amplification strategies (e.g., enzymatic, nanomaterial-enhanced) [31] [32]. |

| Biomarker Heterogeneity | Reliance on a single marker (e.g., CD9) that is not universally expressed [32]. | Perform multiplexed profiling of several surface markers (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81, EGFR) to capture heterogeneous populations [31]. |

| Low Purity & Reproducibility | Co-isolation of non-exosomal contaminants; tedious procedures [32]. | Combine isolation techniques (e.g., size-exclusion chromatography followed by affinity capture); use nanomaterial-based platforms (e.g., MXenes) for improved purity [32] [33]. |

| Matrix Effects | Signal interference from proteins/lipids in biofluids [33]. | Optimize blocking agents (e.g., BSA); validate assays in the specific biological matrix (e.g., plasma, urine) [31] [33]. |

Detailed Protocol: Paper-Based Vertical Flow Assay (VFA) for Exosome Profiling This protocol provides a rapid, cost-effective alternative to flow cytometry for exosome surface protein profiling [31].

- Reagents: Nitrocellulose membrane, primary antibodies (e.g., anti-CD9, anti-CD63, anti-CD81, anti-EGFR), secondary antibody-ALP conjugate, NBT/BCIP substrate, blocking buffer (1% BSA in PBS).

- Equipment: VFA cartridge, vacuum manifold, smartphone or gel documentation system.

Workflow:

- Exosome Isolation: Isolate exosomes from cell culture supernatant or patient plasma using differential ultracentrifugation or a commercial kit [31].

- VFA Assembly: Place the nitrocellulose membrane into the VFA cartridge.

- Sample Application: Load the exosome sample onto the membrane and apply a gentle vacuum to facilitate perpendicular flow and capture.

- Immunodetection:

- Block the membrane with 1% BSA for 30 minutes.

- Incubate with primary antibody (e.g., anti-CD63) for 20 minutes.

- Wash and incubate with ALP-conjugated secondary antibody for 20 minutes.

- Add NBT/BCIP substrate to develop a colorimetric signal.

- Signal Quantification: Capture an image of the membrane with a smartphone and quantify the spot intensity using image analysis software like ImageJ [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Stabilizing Blood Collection Tubes | Prevents white blood cell lysis for up to 7 days, preserving ctDNA VAF [27]. | ctDNA analysis from shipped blood samples. |

| Anti-EpCAM Coated Magnetic Beads | Immunoaffinity capture of epithelial CTCs from whole blood [30]. | Positive enrichment of CTCs using systems like CellSearch. |

| Microfluidic Chip Devices | Low-shear, high-purity CTC isolation based on size/deformability [29]. | Label-free capture of CTCs undergoing EMT. |

| Aptamers (e.g., CD63 aptamer) | Stable, synthetic alternatives to antibodies for exosome capture [32]. | Functionalization of electrochemical biosensors for exosome detection. |

| MXene (Ti3C2) Nanosheets | 2D material with high surface area and conductivity for biosensing [32]. | Signal amplification in electrochemical exosome sensors. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Normalizes for variability in sample prep and analysis for LC-MS/MS [33]. | Absolute quantification of exosomal proteins. |

Experimental Workflows and Logical Diagrams

ctDNA Analysis Optimization Pathway

CTC Capture Strategy Selection

Exosome Detection and Characterization Workflow

Leveraging Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for Comprehensive Mutation Profiling

FAQs: NGS and qPCR in Cancer Biomarker Detection

Q1: How are qPCR Ct values and NGS quality control interconnected? The Cycle Threshold (Ct) value from qPCR is a critical quality control checkpoint in the NGS workflow. It represents the number of amplification cycles required for a target gene's signal to cross a fluorescence threshold, and it is inversely correlated with the starting template concentration [34]. In the context of NGS library preparation, qPCR is used to accurately quantify the concentration of "amplifiable" library fragments before sequencing, ensuring optimal loading on the sequencer for balanced run performance [35]. Anomalous Ct values can indicate issues that will compromise NGS results, such as low template quality or the presence of PCR inhibitors [34].

Q2: What are the primary sources of error in deep NGS for low-frequency variant detection? Sequencing errors are key confounding factors when detecting low-frequency variants, which are crucial for cancer diagnosis and monitoring. A comprehensive analysis identified that errors are introduced at various steps [36]:

- Sample Handling: Can lead to DNA damage, notably causing C>A/G>T substitution errors [36].

- Enrichment PCR: Target-enrichment PCR can lead to an approximately 6-fold increase in the overall error rate [36].

- Polymerase Errors: Incorrect nucleotide incorporation during amplification.

- Sequencing Chemistry: Platform-specific errors during the sequencing process itself.

The study found that different errors have characteristic rates, with A>G/T>C changes occurring at a rate of about 10⁻⁴, while A>C/T>G, C>A/G>T, and C>G/G>C changes occur at a lower rate of 10⁻⁵ [36].

Q3: What strategies can improve the detection of rare mutations in liquid biopsy? Detecting rare mutant alleles in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) is challenging due to the low abundance of ctDNA and the high error rates of conventional methods. Advanced methods involve using Unique Identifiers (UIDs). These are barcode sequences ligated to individual DNA molecules before amplification [37]. All copies derived from the same original molecule (sharing the same UID) are grouped to generate a consensus sequence, which helps distinguish true low-frequency mutations from random PCR or sequencing errors [37]. Newer PCR-based methods like SPIDER-seq are being developed to enable effective error correction with simpler, more cost-effective amplicon sequencing workflows [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing High Ct Values in Pre-NGS qPCR

High Ct values indicate low initial template concentration or reaction inhibition, which can lead to failed or low-quality NGS results. The table below summarizes common causes and solutions.

| Problem Cause | Specific Examples | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Template Concentration/Quality | Template degradation; insufficient input DNA/RNA [34]. | Increase template input; re-extract nucleic acids; check RNA integrity (RIN > 8) [34]. |

| PCR Inhibitors | Co-purified proteins, detergents from extraction; high concentration of reverse transcription reagents [34]. | Dilute the cDNA template; re-purify DNA/RNA; assess sample purity via A260/A280 and A260/A230 ratios [34]. |

| Low Reaction Efficiency | Suboptimal primer design (dimers, hairpins, mismatches); amplicon too long; unsuitable reaction conditions [34]. | Redesign primers; ensure amplicon length is 80-300 bp; optimize annealing temperature; use a two-step protocol [34]. |

| Reagent/Instrument Issues | Improper reagent mixing; pipetting errors; low polymerase activity or suboptimal buffer [34]. | Mix reagents thoroughly; calibrate pipettes; use a different, high-fidelity PCR kit [34]. |

Guide 2: Mitigating Sequencing Errors in NGS Data

Accurate detection of somatic mutations, especially at low frequencies, requires minimizing and correcting for errors. The following table outlines major error types and their mitigation strategies.

| Error Type / Source | Characteristic Error Profile | Recommended Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Handling & DNA Damage | Elevated C>A/G>T substitutions [36]. | Optimize sample collection and storage; use gentle extraction methods. |

| PCR Amplification Errors | Overall increase in error rates (~6-fold); sequence context-dependent errors [36]. | Use high-fidelity polymerases; minimize PCR cycles; employ UID/barcoding consensus methods [36] [37]. |

| Sequencing Chemistry Errors | Platform-specific base substitution errors [36]. | Trim low-quality bases from read ends; filter low-quality reads; use bioinformatic error-suppression tools [36]. |

| Oxidative Damage | Not specified in results. | Include antioxidant additives in reaction buffers. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: qPCR-Based Quantification of NGS Libraries

Purpose: To accurately determine the concentration of amplifiable NGS library fragments prior to sequencing, ensuring equitable sample representation [35].

Materials:

- SYBR Green or EvaGreen qPCR master mix

- Adapter-specific primers

- DNA standards of known concentration

- Prepared NGS libraries

- Real-time PCR instrument

Method:

- Prepare Standards and Samples: Serially dilute the DNA standards to create a standard curve. Dilute the NGS library samples to within the dynamic range of the standard curve.

- Set Up qPCR Reactions: For each standard and unknown library sample, prepare a reaction mix containing the qPCR master mix, primers, and template.

- Run qPCR Program: Use the following cycling conditions:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- 40 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 7 seconds

- Annealing/Extension: 55°C for 15 seconds [38]

- Data Analysis: The instrument software will generate Ct values for all samples. Plot the standard curve (Ct vs. log concentration) and use it to calculate the concentration of amplifiable fragments in the library samples. Normalize the calculated molarity based on the average library size determined by a method like Fragment Analyzer or Bioanalyzer [35].

Protocol 2: Molecular Barcoding for Low-Frequency Variant Detection

Purpose: To sensitively detect rare mutations (e.g., in ctDNA) by reducing false positives from PCR and sequencing errors [37].

Materials:

- DNA samples (e.g., cfDNA from plasma)

- UID-containing adapters and primers

- High-fidelity DNA polymerase

- PCR purification kit

- NGS platform

Method:

- UID Ligation: Fragment genomic DNA and ligate UID-containing adapters to individual DNA molecules. Alternatively, for amplicon-based methods like SPIDER-seq, use primers with UIDs in the first PCR cycles [37].

- Library Amplification: Amplify the tagged library using a high-fidelity polymerase. The number of cycles should be optimized to avoid over-amplification, which can create artifacts and reduce library complexity [35].

- NGS Sequencing: Sequence the final library on an NGS platform to a sufficient depth.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Demultiplexing: Assign reads to samples based on index sequences.

- Cluster Formation: Group reads that share a common UID, indicating they originated from the same original DNA molecule.

- Consensus Calling: Generate a single consensus sequence for each cluster of reads. A true mutation is one that appears in the consensus of a cluster, while random errors are eliminated through the consensus-building process [37].

Workflow Visualization

NGS Library Preparation and QC Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key reagents and their critical functions in NGS and qPCR workflows for reliable mutation profiling.

| Reagent / Kit | Primary Function | Key Considerations for Quality Control |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies DNA for library construction with minimal errors [36]. | Essential for reducing polymerase-induced errors during PCR enrichment; compare error rates of different polymerases [36]. |

| qPCR Quantification Kit | Precisely measures concentration of amplifiable NGS library fragments [35]. | Use adapter-specific primers for accurate quantification; normalize molarity based on library size from electrophoresis [35]. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Ishes high-quality, intact nucleic acids from tumor samples. | Assess DNA quality via A260/A280 ratio (ideal: 1.7-2.2) [39]; ensure sufficient input mass (>20 ng) [39]. |

| UID/Barcoding Adapter Kit | Tags individual DNA molecules for error correction and rare variant detection [37]. | Critical for liquid biopsy and low-frequency variant applications; enables consensus sequencing to distinguish true mutations from noise [37]. |

| Microcapillary Electrophoresis Kit | Analyzes library size distribution and detects by-products like adapter dimers [35]. | Check for a sharp, dominant peak at expected size; by-products >3% of the total library should be removed by re-purification [35]. |

Digital PCR (dPCR) and its Superior Quantification of Rare Targets

In cancer biomarker detection research, the accurate quantification of rare targets, such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), is paramount for early diagnosis, monitoring minimal residual disease, and guiding personalized therapy. However, researchers often face the challenge of high Ct (Cycle threshold) values in quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR), indicating low target abundance that borders on the limit of detection. These high Ct values introduce uncertainty, poor precision, and hinder reliable quantification. Digital PCR (dPCR) emerges as a powerful solution to this problem, fundamentally reimagining nucleic acid quantification. By providing absolute quantification without the need for standard curves and demonstrating superior tolerance to PCR inhibitors, dPCR is revolutionizing the detection of rare mutations in complex biological samples like plasma, thereby enabling more robust and reliable cancer diagnostics [40] [41] [42].

dPCR vs. qPCR: A Technical Comparison

Core Principles and Workflows

The fundamental difference between the two techniques lies in their approach to quantification.

- Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) relies on measuring the accumulation of fluorescent signal at each cycle during the exponential phase of amplification. The cycle at which the fluorescence crosses a predefined threshold (Ct value) is used, with reference to a standard curve, to determine the relative quantity of the starting nucleic acid material [40].

- Digital PCR (dPCR), in contrast, is an end-point measurement. The reaction mixture is partitioned into thousands of individual micro-reactions. After amplification, each partition is analyzed as either positive (containing the target) or negative (not containing the target). The absolute concentration of the target, in copies per microliter, is then calculated directly using Poisson statistics, without the need for a standard curve [40] [43] [42].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the core process of dPCR for ctDNA analysis:

Comparative Analysis: Key Quantitative Differences

The table below summarizes the critical differences that make dPCR particularly suited for quantifying rare targets.

Table 1: Key Operational Characteristics of qPCR versus dPCR

| Parameter | Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR) | Digital PCR (dPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Quantification Method | Relative (requires standard curve) | Absolute (no standard curve) [40] [43] |

| Detection of Rare Variants | >1% mutant allele frequency [43] | ≥0.1% mutant allele frequency [43] [44] |

| Precision & Sensitivity | Detects down to a 2-fold change [40] | High precision; capable of detecting small fold-change differences [40] |

| Tolerance to PCR Inhibitors | Impacted by inhibitors, affecting PCR efficiency [40] [43] | More tolerant due to sample partitioning [40] [43] |

| Ideal Application in ctDNA | Gene expression, high viral load quantification | Rare allele detection, copy number variation, low-level ctDNA quantification [40] [41] |

Troubleshooting High Ct Values: Transitioning from qPCR to dPCR

High Ct values in qPCR experiments for cancer biomarkers signal low template quality or quantity. The following guide addresses common issues and how dPCR overcomes them.

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Issues in Rare Target Detection

| Problem | Possible Causes in qPCR | dPCR Solutions & Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| High Ct/ Low Signal | Very low abundance of ctDNA in wild-type background [41] | Superior Sensitivity: dPCR reliably detects mutant alleles at fractional abundances as low as 0.01% [44]. |

| Poor Precision/ High Variability | Measurement at the plateau phase of PCR; reaction kinetics variability [40] | Absolute Quantification: End-point measurement and Poisson statistics provide a precise count, eliminating variability associated with reaction kinetics [40] [42]. |

| Inhibition & Poor Accuracy | Carry-over of PCR inhibitors (e.g., from plasma); affects reaction efficiency [45] | Enhanced Robustness: Partitioning dilutes inhibitors into many reactions, making the overall process more tolerant [40] [43]. |

| Need for Standard Curves | Relative quantification requires accurate and stable standard curves [40] | Standard-Free: Provides absolute quantification without reference materials, simplifying workflow and improving reliability [43] [42]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My qPCR assays for TP53 mutations in patient plasma show Ct values >35, making quantification unreliable. Can dPCR help? Yes. dPCR is explicitly designed for this scenario. For instance, a study detecting TP53 mutations in head and neck cancer patients successfully quantified ctDNA with a mutant allele frequency down to 0.01%, far below the reliable detection limit of qPCR [44].

Q2: Are my existing qPCR assays (e.g., TaqMan) compatible with dPCR systems? In many cases, yes. Probe-based qPCR assays, especially TaqMan assays, can often be transferred directly to dPCR platforms with minimal optimization, allowing for a smooth transition of your validated assays [43].

Q3: We work with limited patient plasma samples. How much input DNA does dPCR require? dPCR is well-suited for limited samples. Protocols commonly use between 1-10 ng of cfDNA per reaction. The high sensitivity of dPCR allows for accurate data even from these low input amounts, which is typical in liquid biopsy workflows [41] [44].

Experimental Protocol: Detecting ctDNA in Breast Cancer Plasma via dPCR

The following protocol is adapted from clinical studies profiling mutations in genes like PIK3CA, ESR1, and TP53 in breast cancer patients [41].

Detailed Step-by-Step Methodology

- Sample Collection & Plasma Preparation: Collect blood in K2EDTA tubes. Centrifuge at 800-1600 g for 10 minutes to separate plasma. Transfer supernatant to a fresh tube and perform a second, high-speed centrifugation (16,000 g for 10 min) to remove any remaining cells. Aliquot and store plasma at -80°C until use.

- Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) Extraction: Use commercially available circulating nucleic acid extraction kits (e.g., QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit). Elute DNA in a low-EDTA or EDTA-free buffer to prevent interference with the PCR reaction. A typical starting volume is 2-4 mL of plasma.

- dPCR Assay Setup:

- Design mutation-specific primers and TaqMan probes (FAM-labeled) and a reference assay (e.g., for a wild-type sequence, VIC-labeled).

- Prepare the dPCR reaction mix according to the manufacturer's instructions (e.g., Bio-Rad's ddPCR Supermix for Probes). A typical 20-22 µL reaction contains 1X supermix, primers and probes at optimized concentrations, and 2-8 µL of the extracted cfDNA.

- Partitioning and Emulsification: Load the reaction mixture into a droplet generator. This instrument partitions each sample into 20,000 nanoliter-sized water-in-oil droplets [44], effectively creating thousands of individual PCR reactions.

- PCR Amplification: Transfer the droplets to a 96-well PCR plate and run on a conventional thermal cycler. Use a standard thermal cycling profile: initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40-55 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 sec and annealing/extension at a primer-specific temperature (e.g., 55-60°C) for 60 sec, followed by a final enzyme deactivation step at 98°C for 10 min. A ramp rate of 2°C/sec is standard.

- Droplet Reading and Analysis: Place the plate in a droplet reader, which aspirates each sample sequentially. The reader measures the fluorescence in each droplet (FAM and VIC). Using the manufacturer's software (e.g., QuantaSoft), set thresholds to distinguish positive and negative droplets for each channel. The software automatically calculates the absolute concentration (copies/µL) of the mutant and wild-type DNA based on the fraction of positive droplets and Poisson statistics.

The logical flow of data analysis from droplet reading to final result is shown below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for dPCR

Successful dPCR experimentation relies on a set of key reagents and instruments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for dPCR Experiments

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit | Isolation of high-quality, short-fragment cfDNA from plasma samples. | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit [44]. Critical for obtaining clean input material. |

| dPCR Supermix | Provides optimized buffer, dNTPs, and DNA polymerase for robust amplification in partitioned reactions. | ddPCR Supermix for Probes (no dUTP) [44]. Hot-start enzymes are recommended. |

| TaqMan Assay | Sequence-specific detection of wild-type and mutant alleles. Includes primers and fluorescent probes. | Can be adapted from existing qPCR assays or custom-designed [43]. Uses FAM/VIC dyes. |

| Droplet Generator & Reader | Instrumentation for creating nanodroplets and reading endpoint fluorescence. | QX200 Droplet Digital PCR System [44]. The core hardware of the workflow. |

| Negative Controls | To establish baseline and false-positive rates. | No-Template Control (NTC) and Wild-Type-Only DNA [44]. Essential for assay validation. |

Pre-Amplification Strategies and Probe Chemistry Optimization for qPCR

In cancer biomarker detection research, achieving low, reproducible Cycle threshold (Ct) values is paramount for sensitive and reliable results. A high Ct value indicates delayed amplification, often signaling issues with reaction efficiency or target availability. This technical support center provides targeted troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers optimize their qPCR assays, focusing on robust pre-amplification strategies and refined probe chemistry to overcome the common challenge of high Ct values.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing High Ct Values and Poor Reproducibility

Problem: Your qPCR assay is producing high Ct values (typically above 30 in dye-based assays) with poor reproducibility between technical replicates.

Why this happens: High Ct values can stem from factors related to template quality, reaction efficiency, or the presence of inhibitors [15]. For low-expression genes, which are common in cancer biomarker studies, the inherent low abundance of the target transcript is a primary factor [46].

Solutions:

Optimize the Template:

- Input Amount: If the Ct value for the reference gene is normal but the target gene is high, increase the amount of cDNA template in the reaction. Avoid exceeding 1/10 of the total reaction volume [46].

- Purity and Integrity: Assess RNA integrity via agarose gel electrophoresis and check purity using a spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop). Ensure the A260/A280 ratio is around 2.0 [46].

- Remove Inhibitors: Dilute the sample (10x to 1000x). This can reduce the impact of inhibitors and sometimes even lead to a lower Ct value by scattering oligos that may be bound to non-target DNA [47] [17].

Optimize the qPCR Program:

- Switch from a two-step to a three-step cycling protocol.

- Increase the extension time to improve amplification efficiency for longer or complex amplicons [46].

Refine Experimental Procedure:

- Increase the number of replicate wells (e.g., from duplicates to triplicates or more) to allow for statistical removal of outliers.

- Add inert carrier DNA or RNA to the reaction mix. This minimizes the loss of target molecules by preventing their adhesion to tube walls and pipette tips [46].

Table 1: Summary of Optimization Strategies for High Ct Values

| Factor | Problem | Solution | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template | Low input/ concentration | Increase cDNA input; use less diluted stock [46] | Lower Ct value |

| Presence of PCR inhibitors | Dilute sample (10-1000x) [17] | Improved efficiency, potentially lower Ct [47] | |

| qPCR Protocol | Inefficient cycling | Use a 3-step program; extend extension time [46] | Higher amplification efficiency |

| Reaction Setup | Stochastic variation in low-copy targets | Increase replicate wells; add carrier DNA/RNA [46] | Improved reproducibility |

Guide 2: Optimizing Primer and Probe Chemistry

Problem: Non-specific amplification, primer-dimers, or generally low amplification efficiency are leading to high Ct values and unreliable data.

Why this happens: Suboptimal primer and probe design—including secondary structures, inappropriate melting temperatures (Tm), and non-specific binding—severely reduces PCR efficiency [48].

Solutions:

Primer Design Principles:

- Length and GC Content: Design primers 17-22 base pairs long with a GC content between 30-50% [48].

- Melting Temperature (Tm): Ensure the Tm values for the forward and reverse primers are within 2-3°C of each other [48].

- 3' End Stability: Avoid more than three G/C nucleotides within the last five bases at the 3' end to prevent non-specific extension [48].

- Specificity Check: Use tools like NCBI's Primer-BLAST to verify primer specificity and ensure a single amplicon product [48].

- Exon Boundaries: Where possible, design primers to span exon-exon junctions to prevent amplification of genomic DNA [48].

Probe Design and Validation:

- For TaqMan probes, ensure the probe's Tm is 5-10°C higher than the primers.

- Avoid guanine (G) residues at the 5' end of the probe, as this can quench the reporter dye fluorescence.

Concentration Optimization:

- Empirically test primer and probe concentrations. Using excessively high or low primer concentrations can lead to a significant drop in PCR efficiency and nonspecific amplification [48]. A typical starting concentration is 50-900nM for primers and 50-250nM for probes.

Table 2: Primer and Probe Design Criteria for Optimal qPCR [48]

| Parameter | Optimal Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 17 - 22 bp | Balances specificity and efficient binding. |

| GC Content | 30 - 50% | Ensures stable binding without excessively high Tm. |

| Tm Difference | < 2 - 3 °C | Ensures both primers bind with similar efficiency. |

| 3' End Complementarity | Avoid >3 G/Cs | Minimizes mis-priming and non-specific amplification. |

| Amplicon Length | 50 - 150 bp | Shorter products amplify with higher efficiency. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why are my Ct values too high (>35) or sometimes not detectable at all? [15]

A: Several factors can cause this:

- Biological: The target gene may not be expressed above the assay's detection limit.

- Technical:

- Poor RNA Quality: Check RNA integrity and purity.

- Insufficient Template: Use more input RNA or a less diluted cDNA sample.

- Experimental Error: Always include a positive control template to troubleshoot reagents and procedure.

- Primer-Template Mismatch: If using a vector system, ensure your primers are designed to match the transcribed regions (e.g., not just the UTRs present in the genomic DNA).

Q2: My amplification curves have an unusual shape or are jagged. What does this mean? [47]

A: Abnormal curve shapes often point to specific issues:

- Jagged Signal: Can be caused by poor amplification, a weak probe signal, or mechanical errors like bubbles in the well. Ensure sufficient probe concentration and mix reaction components thoroughly.

- Low Plateau Phase: Can result from limiting reagents, degraded dNTPs/master mix, or an inefficient reaction. Prepare fresh stock solutions and check reagent calculations.

- Unexpectedly Early Cq: Can indicate genomic DNA contamination in an RNA assay, poor primer specificity, or amplification of a multi-copy gene. Treat samples with DNase and redesign primers for specificity.

Q3: How can I validate my qPCR assay to ensure confidence in my results, especially for clinical cancer research? [49]

A: Proper validation is critical. Key parameters to check include:

- Amplification Efficiency: Calculate from a standard curve of serial dilutions. Efficiency should be between 90-110% (slope between -3.58 and -3.10) [48].

- Linearity (R²): The correlation coefficient for your standard curve should be ≥0.980 [49].

- Specificity: Ensure a single peak in the melt curve (for SYBR Green) or a single band of the expected size on a gel.

- Dynamic Range: The range of template concentrations over which the assay is linear and quantitative.

- Inclusivity/Exclusivity: Verify that your assay detects all intended target variants (inclusivity) and does not cross-react with genetically similar non-targets (exclusivity).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Optimized qPCR in Biomarker Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Considerations for Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized qPCR Master Mix | Provides DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffers, and fluorescent dye. | For low-expression targets, use kits specifically validated for high sensitivity and robust detection of low-copy templates [46]. |

| High-Quality Primers & Probes | Specifically amplifies and detects the target sequence. | HPLC or PAGE purification is recommended. Adhere to strict design principles to avoid secondary structures [48]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent for preparing reagents and dilutions. | Ensures the reaction is free of RNases and DNases that could degrade components. |

| Positive Control Template | Plasmid or cDNA with a known copy number of the target. | Essential for assay validation, troubleshooting, and monitoring inter-run variation. |

Experimental Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and troubleshooting high Ct values in a qPCR experiment.

This diagram illustrates the critical relationship between robust primer/probe design and successful qPCR amplification, which is fundamental to avoiding high Ct values.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Analyzing Complex Biomarker Patterns

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General AI Biomarker Concepts

Q1: What is the core advantage of using AI for biomarker discovery over traditional methods? AI-powered biomarker discovery transforms the process from a hypothesis-driven approach to a systematic, data-driven exploration. It uses machine learning and deep learning to analyze high-dimensional datasets (genomic, proteomic, imaging) to uncover complex, non-intuitive patterns that traditional methods often miss. This can reduce discovery timelines from years to months or even days [50].

Q2: In what ways can AI help with troubleshooting high Ct values or other assay inconsistencies? AI models can integrate multiple data types to provide context and alternative validation paths. For instance:

- Multi-modal Verification: If a qPCR assay shows high Ct values, AI can analyze concurrent digital pathology images of the biopsy sample to verify tumor cell content and quality, helping to distinguish a true negative from a failed assay [51] [52].

- Trend Analysis: AI can identify subtle patterns in sample metadata (e.g., storage time, extraction batch) that correlate with assay performance issues, pinpointing sources of technical variability [50].

Q3: What are the different types of biomarkers that AI can help identify? AI platforms are adept at finding several biomarker categories, each with a distinct clinical purpose [50]:

- Diagnostic Markers: Help identify the presence and type of cancer (e.g., AI-identified markers in liquid biopsies).

- Prognostic Markers: Predict the likely course of the disease, such as how aggressive a cancer is, independent of treatment.