The Adenosine A1 Receptor in Breast Cancer: Emerging Target for Therapeutic Intervention

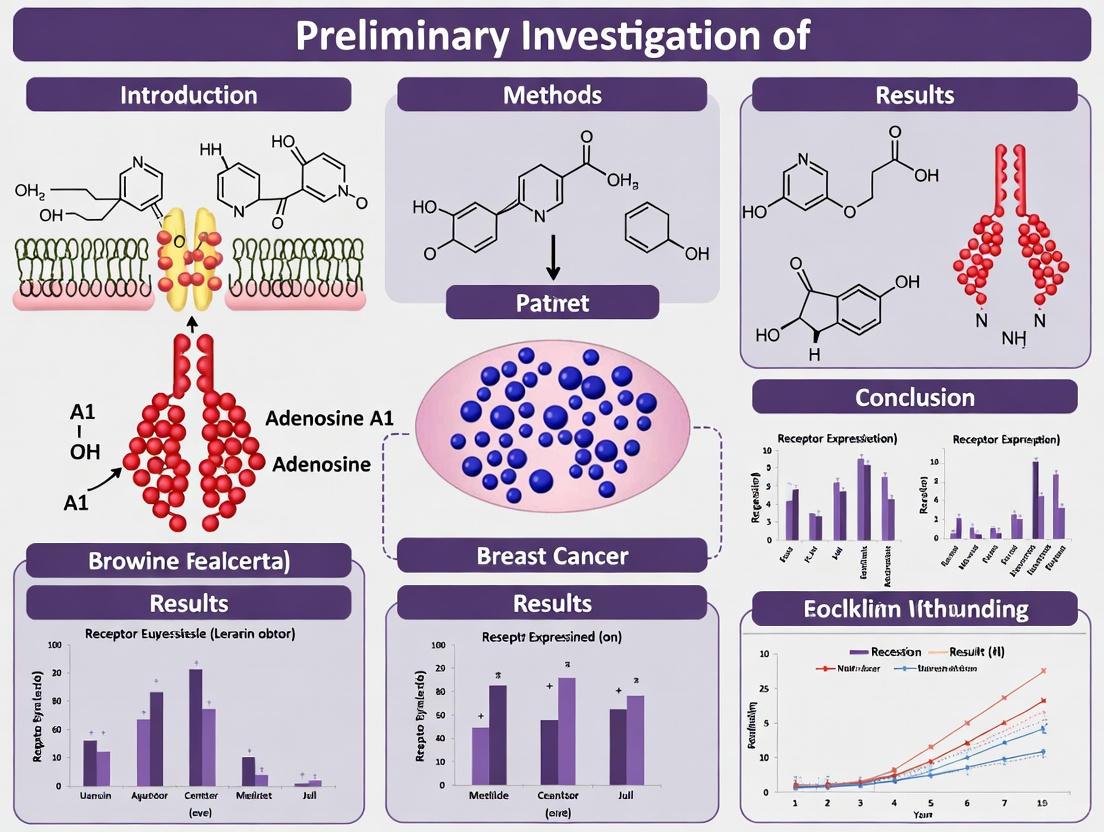

This article provides a comprehensive preliminary investigation into the role of the Adenosine A1 Receptor (A1R) in breast cancer.

The Adenosine A1 Receptor in Breast Cancer: Emerging Target for Therapeutic Intervention

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive preliminary investigation into the role of the Adenosine A1 Receptor (A1R) in breast cancer. Targeting the adenosinergic pathway, particularly the A1R, represents a promising new frontier in oncology. We explore the foundational biology of A1R and its expression within the breast tumor microenvironment, review cutting-edge methodological approaches for investigating this target—from bioinformatics to molecular docking and in vitro validation—and address key challenges in drug development, such as achieving subtype selectivity. Finally, we synthesize validation strategies and comparative analyses with other adenosine receptors, offering a consolidated perspective for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to translate A1R modulation into effective breast cancer therapies.

Unraveling the Role of the A1 Adenosine Receptor in Breast Cancer Biology

Adenosine A1 Receptor Signaling and Downstream Pathways in Cancer

The adenosine A1 receptor (A1AR) is a G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that has emerged as a significant player in cancer biology, particularly in breast cancer. Within the tumor microenvironment, extracellular adenosine concentrations rise, often due to hypoxia and the enzymatic breakdown of ATP by CD39 and CD73 [1]. This adenosine can then activate A1AR, initiating signaling cascades that influence critical cellular processes such as proliferation, apoptosis, and migration. The receptor's role is complex, acting as both a target and a regulator of established oncogenic pathways, including those driven by estrogen receptor-alpha (ERα) [2]. This preliminary investigation frames the A1AR within the context of breast cancer research, synthesizing current understanding of its signaling mechanisms, downstream effects, and emerging potential as a therapeutic target. The following sections provide an in-depth technical analysis of the molecular pathways involved, supported by experimental data and protocols relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

Molecular Biology of the Adenosine A1 Receptor

The A1AR is a class A GPCR characterized by its high affinity for adenosine. Its structure consists of seven transmembrane domains, and it primarily couples to the Gi/o family of G proteins [1]. Upon agonist binding, the canonical signaling pathway involves the inhibition of adenylate cyclase (AC), leading to a reduction in intracellular cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels [3] [1]. Beyond this primary pathway, A1AR activation can also stimulate phospholipase C (PLC), leading to the generation of inositol trisphosphate (IP3) and diacylglycerol (DAG), which in turn modulate intracellular calcium levels and protein kinase C (PKC) activity [1]. In the context of cancer, and specifically breast cancer, A1AR is frequently overexpressed, and its expression is functionally linked to cell viability and the suppression of apoptosis [4] [5]. Intriguingly, in ERα-positive breast cancer cells, A1AR expression is upregulated by estradiol (E2), forming a feed-forward loop that promotes cancer growth [2] [6].

Downstream Signaling Pathways and Functional Outcomes

The activation of A1AR initiates a network of downstream signaling events that culminate in distinct functional outcomes in cancer cells. The diagram below illustrates the core signaling pathways and their biological consequences.

The core A1AR signaling network illustrates how receptor activation influences key cellular decisions. The primary pathway involves the inhibition of adenylate cyclase and a subsequent decrease in cAMP, which reduces Protein Kinase A (PKA) activity. This suppression of the cAMP/PKA axis promotes proliferation and suppresses apoptosis [7] [1]. Concurrently, A1AR can stimulate PLC, leading to PKC activation and calcium release, which further drives proliferation and migration [1]. A critical regulatory node is the reciprocal relationship with ERα, where A1AR enhances ERα transcriptional activity, and in turn, is upregulated by E2 [2] [6]. Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of A1AR leads to the upregulation of the tumor suppressor p53 and executioner caspases, pushing the cell toward apoptosis [4] [8] [5].

Key Functional Consequences in Cancer

Promotion of Cell Proliferation: The A1AR-driven reduction in cAMP and enhancement of ERα activity creates a synergistic pro-proliferative signal. Studies show that A1AR ablation or pharmacological inhibition reduces basal and E2-dependent proliferation in ERα-positive breast cancer cells [2] [6]. Furthermore, overexpression of A1AR in an ERα-negative cell line was sufficient to induce proliferation [2].

Inhibition of Apoptosis: A1AR signaling confers resistance to programmed cell death. Research indicates that the A1AR agonist CPA increases cell viability and reduces apoptosis, an effect correlated with the down-regulation of p53 and caspases 3, 8, and 9 [4] [5]. Conversely, the antagonist DPCPX induces apoptosis by upregulating these key apoptotic molecules [4] [8] [5].

Modulation of the Tumor Microenvironment: While this review focuses on breast cancer cells, it is noted that A1AR on host cells, such as microglial cells in glioblastoma models, can modulate tumor growth [3]. This highlights the potential for A1AR signaling to influence the broader tumor microenvironment.

Quantitative Data on A1AR Modulation in Breast Cancer Models

The effects of A1AR modulation have been quantified in various in vitro studies, primarily using the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line. The tables below consolidate key quantitative findings for easy comparison.

Table 1: Impact of A1AR Ligands on Cell Viability and Apoptosis in MCF-7 Cells

| Ligand | Role | Concentration | Exposure Time | Key Quantitative Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPCPX | Antagonist | 87 nM | 72 h | Significantly induced apoptosis; reduced cell viability | [4] [5] |

| CPA | Agonist | 180 μM | 72 h | Increased cell viability; reduced apoptosis | [4] [5] |

| ODC-MPI-2 | Dual A1AR/ODC Inhibitor | Varies | 48-72 h | Inhibited growth, proliferation, and migration/invasion | [7] |

Table 2: Gene Expression Changes Following A1AR Antagonism with DPCPX

| Gene | Function | Expression Change | Experimental Method | Biological Consequence | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP53 (p53) | Tumor suppressor | Upregulated | Real-time PCR | Promotion of cell cycle arrest and apoptosis | [4] [8] [5] |

| CASP3 | Executioner caspase | Upregulated | Real-time PCR | Induction of apoptotic cell death | [4] [5] |

| CASP8 | Extrinsic pathway caspase | Upregulated | Real-time PCR | Activation of extrinsic apoptosis | [4] [5] |

| CASP9 | Intrinsic pathway caspase | Upregulated | Real-time PCR | Activation of intrinsic apoptosis | [4] [5] |

| ERα | Estrogen receptor | Downregulated (via siRNA) | Western Blot / PCR | Reduced E2/ERα transcriptional activity | [2] [6] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

To investigate A1AR signaling in cancer, a combination of molecular, cellular, and computational approaches is employed. The workflow below outlines a typical integrated research strategy.

This experimental workflow begins with target identification and proceeds through computational and laboratory validation stages. Below are detailed protocols for key methodologies.

In Silico Target Screening and Molecular Docking

Objective: To identify A1AR as a potential therapeutic target and evaluate compound binding affinity.

- Target Prediction: Input the chemical structures of known active compounds into the SwissTargetPrediction database (http://swisstargetprediction.ch), specifying "Homo sapiens" as the species to generate a list of potential protein targets [9].

- Intersection Analysis: Use a online tool (e.g., Venny) to perform an intersection analysis of targets predicted for multiple active compounds to identify common targets, such as A1AR [9].

- Ligand Preparation: Create a ligand library and optimize 3D structures using software like Discovery Studio. Perform energy minimization and assign partial charges [9].

- Molecular Docking: Dock the prepared ligands into the binding site of the A1AR structure (e.g., PDB ID: 7LD3) using a docking program (e.g., CHARMM within Discovery Studio). Use the LibDock score to evaluate binding poses, typically considering scores >130 as indicative of strong binding affinity [9].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

Objective: To assess the stability and dynamics of the A1AR-ligand complex over time.

- System Setup: Use GROMACS 2020.3 with the AMBER99SB-ILDN force field for the protein. Generate ligand parameters using the GAFF force field via ACPYPE. Solvate the system in a cubic box with TIP3P water molecules and add ions (e.g., Cl-) to achieve electrical neutrality [9].

- Energy Minimization: Perform an initial energy minimization step using the steepest descent algorithm to relieve any steric clashes.

- Equilibration: Conduct a 150 ps restrained MD simulation under NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) and NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) ensembles to stabilize the system temperature (298.15 K) and pressure (1 bar) [9].

- Production Run: Execute an unrestricted MD simulation for a defined period (e.g., 15 ns or longer) with a time step of 0.002 ps. Analyze the resulting trajectory (e.g., using VMD 1.9.3) for root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF), and specific ligand-receptor interactions across simulation frames [9].

In Vitro Analysis of Apoptosis and Gene Expression

Objective: To quantify the effects of A1AR ligands on apoptosis and relevant gene expression in breast cancer cell lines.

- Cell Culture and Treatment: Culture MCF-7 cells in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% FBS and antibiotics at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere. Treat cells at ~80% confluence with specific A1AR ligands (e.g., CPA or DPCPX) at their predetermined IC50 concentrations for 24, 48, and 72 hours [4] [5].

- MTT Viability Assay: Seed 10^4 cells per well in a 24-well plate. After treatment, add MTT solution to each well and incubate for 3 hours. Lyse the formed formazan crystals with DMSO and measure the optical density at a specific wavelength (e.g., 570 nm) using a plate reader. Calculate cell viability as a percentage of the control group [4] [5].

- Annexin V/Propidium Iodide (PI) Apoptosis Assay: Harvest at least 4 × 10^5 treated cells, wash with PBS, and resuspend in binding buffer. Stain cells with Annexin V-FITC and PI according to the manufacturer's protocol. Analyze the stained cells using a flow cytometer (e.g., FACScan) to distinguish between live (Annexin V-/PI-), early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-), late apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI+), and necrotic (Annexin V-/PI+) cell populations [4] [5].

- Real-time PCR for Gene Expression: Extract total RNA from treated cells using a kit (e.g., RNeasy Mini Kit). Reverse-transcribe 100 ng of RNA into cDNA. Perform real-time PCR using SYBR Green Master Mix and specific primers for p53, caspases 3, 8, 9, and an endogenous control (e.g., GAPDH). Analyze the data using the comparative CT (ΔΔCT) method to determine relative gene expression levels [4] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Investigating A1AR in Cancer

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Role | Example Usage in Research |

|---|---|---|

| DPCPX | Selective A1AR antagonist | Used to block A1AR activity, leading to reduced proliferation and induced apoptosis in MCF-7 cells; IC50 ~87 nM [4] [5] [7]. |

| CPA (N6-Cyclopentyladenosine) | Selective A1AR agonist | Used to activate A1AR signaling, resulting in increased cell viability and suppressed apoptosis; IC50 ~180 μM [4] [5]. |

| ODC-MPI-2 | Dual A1AR and ODC inhibitor | Used to simultaneously target polyamine synthesis and A1AR signaling, showing synergistic antitumor effects in MCF-7 cells [7]. |

| DFMO (α-Difluoromethylornithine) | Irreversible ODC inhibitor | Used in combination with DPCPX to demonstrate synergistic growth inhibition of MCF-7 cells [7]. |

| siRNA targeting Adora1 | Gene silencing tool | Used to ablate A1AR expression, confirming its role in basal and E2-dependent proliferation and ERα transcriptional activity [2] [6]. |

| A1AR cDNA | Gene overexpression tool | Used in ERα-negative cell lines to demonstrate A1AR-induced proliferation [2]. |

This preliminary investigation consolidates evidence that the adenosine A1 receptor is a significant node in the signaling network of breast cancer. Its dual role as a target and regulator of ERα action, coupled with its ability to suppress p53-mediated apoptosis, positions it as a compelling therapeutic target. The consistent pro-tumorigenic effects of receptor agonists and the anti-cancer effects of antagonists like DPCPX across multiple studies provide a strong rationale for targeting A1AR. Emerging strategies, such as the dual inhibition of A1AR and ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) with molecules like ODC-MPI-2, demonstrate enhanced efficacy and represent a promising avenue for combination therapy [7]. Future research should focus on validating these findings in more complex in vivo models and exploring the translational potential of A1AR-targeted agents, particularly in hormone-dependent breast cancers where the crosstalk with ERα signaling can be exploited for therapeutic benefit.

The A1R within the Immunosuppressive Tumor Microenvironment of Breast Cancer

The adenosine A1 receptor (A1R) is a high-affinity G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) for adenosine, traditionally studied for its roles in the central nervous system and cardiac function [10] [11]. Within the context of the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) of breast cancer, the role of A1R is less characterized compared to other adenosine receptors like A2A and A2B. However, emerging evidence suggests it contributes significantly to the intricate network of immune evasion mechanisms that hinder effective anti-tumor responses [12] [13]. This whitepaper synthesizes current knowledge on A1R expression, signaling, and function within the breast cancer TME, framing it as a critical component of the hypoxia-adenosine immunosuppressive axis and a potential target for therapeutic intervention. A preliminary investigation into A1R reveals a complex role that warrants deeper exploration to fully exploit the adenosine pathway for breast cancer immunotherapy.

Adenosine Metabolism and Signaling in the TME

The immunosuppressive adenosine gradient in the TME is generated through a tightly regulated process. Under conditions of cellular stress, such as hypoxia within the tumor, intracellular ATP is released into the extracellular space [14]. Pannexin 1 (PANX1) channels facilitate this release of ATP [14]. The ecto-enzymes CD39 (ENTPD1) and CD73 (NT5E) then sequentially hydrolyze exATP to AMP and finally to adenosine [12] [14]. In triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) have been identified as a source of these adenosine-generating enzymes [14].

Once produced, extracellular adenosine exerts its effects by binding to one of four adenosine receptors (A1, A2A, A2B, A3) on target cells. These receptors are GPCRs with differing affinities for adenosine; A1R and A2AR are high-affinity receptors, while A2BR and A3R have lower affinity [15] [11]. The A1R signals primarily through Gi/o proteins, leading to the inhibition of adenylyl cyclase and a decrease in intracellular cAMP levels [15] [11].

Table 1: Adenosine Receptors in the Tumor Microenvironment

| Receptor | Gene | Adenosine Affinity | Primary Signaling | General Role in Cancer Immunity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | ADORA1 | High (nM range) | Gi/o → ↓ cAMP [15] [11] | Less defined; potential role in immune cell regulation [13] |

| A2A | ADORA2A | High (nM range) | Gs → ↑ cAMP [15] | Potent immunosuppression; inhibits T-cell and NK cell function [12] |

| A2B | ADORA2B | Low (µM range) | Gs / Gq → ↑ cAMP / ↑ IP3, DAG [15] | Involved in angiogenesis, inflammation; contributes to immunosuppression [12] |

| A3 | ADORA3 | Low (µM range) | Gi/o → ↓ cAMP [15] | Context-dependent roles in promoting apoptosis or survival [12] |

The following diagram illustrates the core pathway of adenosine generation and its immunosuppressive action via the A1 receptor on immune cells in the breast cancer TME.

A1R-Mediated Immunosuppressive Mechanisms in Breast Cancer

While the A2A receptor is often the primary focus in adenosine-mediated immunosuppression, A1R signaling contributes to shaping an inhibitory immune landscape in breast cancer through several mechanisms.

Direct Modulation of Immune Cell Function

A1R is expressed on various innate and adaptive immune cells, including monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and microglia [13]. Activation of A1R on these cells can influence their function within the TME. In the context of breast cancer, high expression of PANX1, which drives adenosine production, is associated with increased recruitment of tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) [14]. These TANs, in turn, express high levels of CD39 and CD73, creating a feed-forward loop for adenosine production and further amplifying local immunosuppression [14]. A1R signaling in other immune cells can inhibit pro-inflammatory responses and potentially promote phenotypes that support tumor growth [13].

Neuronal-like Inhibition in the TME

In the central nervous system, A1R activation provides potent neuronal inhibition through two principal mechanisms: membrane hyperpolarization via activation of potassium (K+) channels, and suppression of synaptic transmission via inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) and synaptic vesicle release [11]. An analogous process may occur within the TME, where A1R signaling on immune cells like T cells could lead to functional hyperpolarization and inhibition of cytotoxic effector functions, such as the release of perforin and granzymes, thereby silencing the anti-tumor immune response.

Investigating A1R in Breast Cancer: Research Landscape

Expression and Prognostic Value

The expression and clinical significance of immune checkpoint genes in breast cancer subtypes are highly variable. A systematic investigation of 50 immune checkpoint genes found that the expression pattern of ADORA2A (A2AR) was not significantly correlated with overall survival in breast cancer patients [16]. However, comprehensive data specifically on A1R (ADORA1) mRNA or protein expression levels across breast cancer molecular subtypes (Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2+, TNBC) and its direct prognostic value remains an area requiring further elucidation. This gap highlights the preliminary nature of A1R investigation in breast cancer.

Research Reagent and Experimental Toolkit

Studying A1R's role requires a suite of specific pharmacological and molecular tools. The table below details key reagents for in vitro and in vivo A1R research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for A1R Investigation

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Function / Specificity | Example Compounds / Identifiers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selective Antagonists | Small Molecule | Competitively blocks A1R to investigate its function | DPCPX, CPT (8-cyclopentyltheophylline) [12] [15] |

| Selective Agonists | Small Molecule | Activates A1R to probe downstream signaling and effects | CCPA, Tecadenoson, Selodenoson [15] |

| Allosteric Modulators | Small Molecule | Binds a separate site to fine-tune orthosteric ligand activity (PAM/NAM) [10] | T-62 (PAM, reached clinical trial for pain) [10] |

| Non-Selective Antagonists | Small Molecule | Blocks multiple adenosine receptors (A1, A2A) | Caffeine, Theophylline [15] |

| shRNA/siRNA | Molecular Tool | Knocks down A1R gene expression for loss-of-function studies | PANX1 shRNA (used in TNBC models) [14] |

Proposed Experimental Workflow for A1R Investigation

A comprehensive research plan to delineate the role of A1R in breast cancer is essential. The following diagram outlines a multi-faceted experimental workflow, from initial assessment to functional validation.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

A1R Expression Profiling via Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

- Protocol: Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) breast cancer tissue sections are deparaffinized and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval is performed by heating slides in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 20 minutes. Endogenous peroxidase is blocked with 3% H₂O₂. Sections are incubated overnight at 4°C with a validated primary anti-A1R antibody. After washing, a species-matched secondary antibody conjugated to HRP is applied for 30-60 minutes at room temperature. Staining is visualized using 3,3'-Diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen, and slides are counterstained with hematoxylin [14].

- Analysis: Staining is evaluated using a composite score based on intensity (0: negative, 1: weak, 2: positive, 3: strong) and frequency (1: 0-10%, 2: 11-30%, 3: 31-50%, 4: 51-75%, 5: 76-100%). The final score is the product of intensity and frequency. Samples can be dichotomized into A1R-high and A1R-low groups based on the median score [14].

Extracellular Adenosine (exADO) Quantification Assay

- Protocol: Breast cancer cell lines (e.g., MDA-MB-231, HCC-1937 for TNBC; MCF-7 for Luminal A) or single-cell suspensions from digested tumor specimens are plated in 24-well plates (2 x 10⁴ cells/well). After adherence, the culture medium is replaced with a fresh, serum-free medium. Cells are incubated for a predetermined time (e.g., 2-4 hours) under normoxic or hypoxic (1% O₂) conditions to mimic the TME. The cell culture supernatant is then collected and centrifuged at 4°C to remove any cellular debris [14].

- Analysis: The cleared supernatant is analyzed for adenosine concentration using a commercial competitive ELISA kit or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS), following the manufacturer's protocol. Values are normalized to total cellular protein content.

T-cell Co-culture and Functional Assay

- Protocol: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) are isolated from healthy donors. CD8+ T cells are purified using magnetic-activated cell sorting (MACS). Target breast cancer cells are co-cultured with activated CD8+ T cells at a predetermined ratio (e.g., 1:5) in the presence of an A1R-selective agonist (e.g., CCPA, 100 nM), an antagonist (e.g., DPCPX, 1 µM), or a vehicle control.

- Readouts:

- Cytokine Production: After 24-48 hours, supernatant is collected, and IFN-γ secretion is quantified by ELISA [17].

- T-cell Proliferation: CFSE-labeled T cells are used. After 3-5 days of co-culture, proliferation is assessed by flow cytometry based on CFSE dilution.

- Cytotoxicity: Real-time cytotoxicity is measured using platforms like Incucyte with caspase-based apoptosis assays.

Therapeutic Targeting of A1R and Future Directions

Targeting the adenosine pathway has emerged as a promising strategy in cancer immunotherapy. While most efforts have focused on A2AR antagonism or inhibition of CD39/CD73, A1R presents a complementary target [12].

Pharmacological Antagonism: Small-molecule A1R antagonists like DPCPX are valuable research tools. However, their therapeutic application may be limited by on-target side effects, particularly in the central nervous system and cardiovascular system, given A1R's physiological roles in reducing heart rate and promoting sedation [12] [10].

Allosteric Modulation: A promising approach to overcome the limitations of orthosteric drugs is the development of allosteric modulators. Positive allosteric modulators (PAMs) can enhance the effect of endogenous adenosine in a context-dependent manner, while negative allosteric modulators (NAMs) can inhibit it. Allosteric ligands can offer superior receptor subtype selectivity and a "ceiling effect" that may spare fundamental physiological signaling, potentially resulting in a safer therapeutic window [10]. The A1R PAM T-62 has previously reached clinical trials for neuropathic pain, demonstrating the clinical translatability of this mechanism [10].

Combination Therapies: Given the redundancy in immunosuppressive pathways, targeting A1R will likely be most effective in combination with other agents. Logical combinations include:

- Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies [18].

- A2AR Antagonists: To achieve broad-spectrum adenosine receptor blockade.

- CD39/CD73 Inhibitors: To reduce the production of the ligand (adenosine) itself [12].

In conclusion, the A1R represents a nuanced and underexplored component of the immunosuppressive network in breast cancer. A preliminary investigation confirms its presence and suggests mechanisms by which it contributes to immune evasion. Future research must systematically define its expression, function, and therapeutic potential using the detailed experimental frameworks and tools outlined herein.

Expression Patterns and Distribution of A1R in Breast Cancer Tissues

The adenosine A1 receptor (A1R, also designated as Adora1) has emerged as a significant molecular player in breast cancer pathogenesis, representing a promising target for therapeutic intervention. Within the context of breast cancer biology, A1R demonstrates a dual regulatory role, functioning both as a target and regulator of estrogen receptor-alpha (ERα) action [6]. This receptor mediates the proliferative effects of estradiol (E2), establishing a critical link between hormonal signaling and purinergic receptor pathways in cancer progression. The therapeutic potential of A1R inhibition is supported by experimental evidence demonstrating that selective A1R antagonists can significantly reduce breast cancer cell proliferation [6]. Recent advances in bioinformatics and computational chemistry have further validated A1R as a key candidate for targeted breast cancer treatment, with studies employing molecular docking and dynamics simulations to design compounds with high binding affinity for this receptor [9] [19]. This whitepaper comprehensively examines the expression patterns, distribution, and functional significance of A1R in breast cancer tissues, providing researchers with essential methodological frameworks for its investigation.

Biological Significance of A1R in Breast Cancer Progression

A1R participates in a feed-forward loop with estradiol and ERα that significantly favors breast cancer growth [6]. In ERα-positive breast cancer cells, estradiol upregulates A1R messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein levels, an effect that can be reversed by the E2 antagonist ICI 182,780 [6]. This regulatory relationship positions A1R as a crucial intermediary in hormonal signaling pathways that drive tumor proliferation.

The functional importance of A1R in breast cancer cell growth has been validated through multiple experimental approaches. Genetic ablation of A1R in ERα-positive cells significantly reduces both basal and E2-dependent proliferation, while A1R overexpression in ERα-negative cell lines induces proliferative activity [6]. Similarly, pharmacological inhibition using the selective A1R antagonist DPCPX effectively reduces proliferation, confirming A1R's role as a mediator of E2/ERα-dependent breast cancer growth [6].

Intriguingly, A1R ablation decreases both mRNA and protein levels of ERα and consequently diminishes estrogen-responsive element-dependent ERα transcriptional activity [6]. This regulatory effect extends to the binding activity of ERα to promoter regions of target genes such as TFF1, resulting in reduced TFF1 promoter activity and mRNA levels [6]. These findings collectively establish that A1R is required for the full transcriptional activity of ERα upon E2 stimulation, highlighting its fundamental role in hormone-responsive breast cancer signaling networks.

Quantitative Expression Profiles and Distribution Patterns

Expression Levels in Breast Cancer Models

Table 1: A1R Expression and Functional Assays in Breast Cancer Models

| Experimental Model | Expression/Effect | Measurement Method | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERα+ breast cancer cells | Upregulated by E2 | mRNA and protein analysis | Enhanced proliferation |

| A1R ablation models | Reduced ERα expression | mRNA/protein measurement | Decreased E2-dependent proliferation |

| A1R antagonist treatment | Inhibited proliferation | Cell viability assays | Reduced cancer growth |

| Molecular docking | Stable binding confirmed | LibDock Score: 148.673 [19] | Rational drug design |

The expression of A1R demonstrates cell-type specificity within breast cancer models. In ERα-positive cells, A1R expression is significantly enhanced by estradiol stimulation, creating a positive feedback loop that amplifies proliferative signaling [6]. This regulatory relationship is particularly relevant in luminal breast cancer subtypes, where hormonal signaling drives tumor progression.

Experimental evidence indicates that A1R targeting generates significant anti-proliferative effects across multiple breast cancer models. Small interference RNA-mediated ablation of A1R consistently reduces proliferative rates, while selective A1R antagonists demonstrate dose-dependent inhibition of cancer growth [6]. The stability of A1R-compound interactions has been confirmed through molecular dynamics simulations, with Compound 5 exhibiting particularly stable binding to the human adenosine A1 receptor-Gi2 protein complex (PDB ID: 7LD3) [9] [19].

Tissue Distribution Patterns

Table 2: A1R Distribution in Breast Tissue Compartments

| Tissue Compartment | A1R Expression Level | Association with Tumor Features | Methodological Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor epithelium | Variable | Correlates with proliferation | IHC, mRNA analysis |

| Stromal compartment | Present | Microenvironment modulation | Immunohistochemistry |

| ERα+ tumors | Elevated | Hormone response | Comparative expression analysis |

| Invasive regions | Context-dependent | Potential invasion role | Spatial transcriptomics |

The distribution of A1R across breast tissue compartments reveals complex patterning that reflects its multifaceted role in cancer progression. While comprehensive immunohistochemical studies specifically detailing A1R distribution patterns in human breast cancer tissues are limited in the available literature, its expression is known to correlate with functional hormone responsiveness [6].

The spatial organization of A1R expression likely influences therapeutic accessibility and drug targeting efficacy. Recent methodological advances in spatial transcriptomics could provide more detailed mapping of A1R distribution patterns across different breast cancer subtypes and tissue regions [20]. Such approaches would help elucidate whether A1R demonstrates preferential expression in specific topological niches within the tumor microenvironment.

Experimental Protocols for A1R Investigation

Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulations

Protocol Objective: To evaluate binding stability between candidate compounds and the human adenosine A1 receptor-Gi2 protein complex (PDB ID: 7LD3) [9] [19].

Step 1: System Preparation

- Obtain the crystal structure of the human adenosine A1 receptor-Gi2 protein complex (PDB ID: 7LD3)

- Prepare the ligand library using Discovery Studio 2019 Client

- Perform docking simulations with CHARMM to refine ligand shapes and charge distribution

Step 2: Molecular Docking

- Analyze binding interactions between compounds and A1R

- Select best poses based on LibDock scores

- Filter targets with scores exceeding 130 for further analysis [19]

- Compound 5 demonstrated a high LibDock score of 148.673 in studies [19]

Step 3: Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

- Conduct MD simulations using GROMACS 2020.3

- Optimize protein structures with AMBER99SB-ILDN force field

- Model water molecules with TIP3P model

- Calculate ligand charges and generate GAFF force field-compatible files using ACPYPE

- Employ cubic boxes with minimum atom-box boundary distance of 0.8 nm

- Hydrate system with SOL water at 1000 g/L density

- Achieve electrical neutrality by replacing solvent water with chloride ions

- Perform initial energy minimization to relax the system

- Conduct 150 ps restrained MD simulation at 298.15 K

- Run unrestricted MD simulations with time step of 0.002 ps for 15 ns, maintaining isothermal-isobaric conditions at 298.15 K and 1 bar pressure [9]

Step 4: Trajectory Analysis

- Analyze motion trajectory of molecule interacting with target using VMD 1.9.3 software

- Capture data every 200 frames from initial to 8220th frame

- Document molecular dynamics throughout timeframe to understand binding process [9]

Functional Validation in Cellular Models

Protocol Objective: To evaluate the functional consequences of A1R modulation in breast cancer cells.

Step 1: Genetic Manipulation

- For A1R ablation: Utilize small interference RNA (siRNA) targeting A1R mRNA in ERα-positive cells

- For overexpression: Introduce A1R expression vector into ERα-negative cell lines

- Validate manipulation efficiency through quantitative RT-PCR and Western blotting

Step 2: Proliferation Assays

- Assess basal and E2-dependent proliferation rates

- Employ cell counting assays or metabolic activity measures (e.g., MTT, WST-1)

- Include selective A1R antagonist (DPCPX) treatment conditions

- Determine IC50 values for inhibitory compounds (e.g., Molecule 10 demonstrated IC50 = 0.032 µM against MCF-7 cells) [9] [19]

Step 3: Transcriptional Activity Assessment

- Measure ERα mRNA and protein levels following A1R manipulation

- Evaluate estrogen-responsive element-dependent ERα transcriptional activity using reporter assays

- Assess binding activity of ERα to target gene promoters (e.g., TFF1)

- Quantify downstream target gene expression (e.g., TFF1 mRNA levels) [6]

A1R Signaling Pathways in Breast Cancer

The adenosine A1 receptor participates in a complex signaling network that intersects with established oncogenic pathways in breast cancer. A1R activation triggers intracellular responses primarily through G-protein coupled receptor mechanisms, influencing key cellular processes including proliferation, survival, and gene expression.

Figure 1: A1R-ERα Feed-Forward Signaling Loop. This diagram illustrates the reciprocal regulatory relationship between A1R and ERα that promotes breast cancer growth. Estradiol binding to ERα promotes A1R expression, while A1R signaling stabilizes ERα and enhances its transcriptional activity, creating an amplification loop.

The cross-talk mechanism between A1R and ERα represents a clinically significant pathway in hormone-responsive breast cancers. This interaction creates a therapeutic opportunity for dual targeting approaches that simultaneously disrupt hormonal and purinergic signaling axes.

Research Reagent Solutions for A1R Investigation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for A1R Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | MCF-7 (ER+), MDA-MB-231 (ER-) | In vitro models | Cellular proliferation, gene expression studies |

| A1R Agonists | N/A | Pathway activation | Study A1R-mediated effects |

| A1R Antagonists | DPCPX | Pharmacological inhibition | Validate A1R-dependent phenotypes |

| siRNA/shRNA | A1R-targeting sequences | Genetic ablation | Determine A1R necessity in processes |

| Antibodies | Anti-A1R, Anti-ERα | Protein detection | IHC, Western blot, immunofluorescence |

| Molecular Biology | qPCR primers, reporter constructs | Expression and promoter studies | Quantify mRNA, measure activity |

| Computational Tools | Discovery Studio, GROMACS, VMD | Molecular modeling | Docking, dynamics simulations, visualization |

The selection of appropriate research tools is critical for rigorous investigation of A1R in breast cancer models. The MCF-7 cell line (ER+) is particularly relevant for studying A1R-ERα interactions, while MDA-MB-231 (ER-) cells serve as useful comparators [9]. The selective A1R antagonist DPCPX has demonstrated efficacy in functional studies, providing a pharmacological tool for target validation [6].

For computational studies, the human adenosine A1 receptor-Gi2 protein complex (PDB ID: 7LD3) serves as a key structural template for molecular docking and dynamics simulations [9] [19]. The integration of these computational approaches with experimental validation creates a powerful framework for advancing A1R-targeted therapeutic development.

The expression patterns and distribution of A1R in breast cancer tissues reveal a receptor with significant pathophysiological importance and therapeutic potential. As both a regulator and target of ERα action, A1R occupies a strategic position in hormone-responsive breast cancer signaling networks. The development of selective A1R antagonists represents a promising avenue for therapeutic intervention, particularly in combination with established endocrine therapies.

Future research directions should include comprehensive tissue mapping of A1R expression across breast cancer subtypes using advanced spatial transcriptomics and proteomics approaches. Additionally, the exploration of A1R's role in the tumor microenvironment may reveal novel mechanisms of cancer-stroma communication that influence disease progression and treatment response. The continued investigation of A1R in breast cancer will likely yield important insights into cancer biology and contribute to the development of more effective, targeted therapeutic strategies.

The Dual Role of Adenosine Receptors in Tumor Promotion and Suppression

Adenosine receptors (ARs), comprising four subtypes—A1, A2A, A2B, and A3—are G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) that serve as the endogenous receptors for adenosine [21]. These receptors play pivotal roles in numerous physiological and pathological processes, with their significance in cancer biology increasingly recognized. The tumor microenvironment (TME) is characterized by elevated adenosine concentrations, often reaching micromolar levels due to hypoxia and extensive ATP breakdown from necrotic cells [22] [21]. This adenosine-rich milieu engages adenosine receptors in complex signaling networks that exert both tumor-promoting and tumor-suppressive effects, creating a dynamic regulatory system that influences cancer progression, immune evasion, and therapeutic responses.

The dual nature of adenosine receptor signaling in cancer presents a fascinating paradox in oncology research. While certain receptor subtypes and their signaling pathways appear to drive tumor growth and immunosuppression, others can trigger cytostatic and apoptotic pathways in malignant cells [22]. This review explores the complex interplay of adenosine receptor subtypes in cancer, with particular emphasis on the adenosine A1 receptor (A1AR) in breast cancer, integrating current understanding of their mechanisms, experimental approaches for their investigation, and potential therapeutic implications.

Adenosine Receptor Subtypes: Structure, Signaling, and Expression

Molecular Characteristics and Signaling Pathways

Adenosine receptors belong to the class A family of rhodopsin-like GPCRs, each possessing seven transmembrane domains with an extracellular N-terminus and intracellular C-terminus [22]. Despite their structural similarities, these receptors couple to different G proteins and activate distinct intracellular signaling cascades:

A1 Adenosine Receptor (A1AR): The A1 receptor primarily couples to pertussis toxin-sensitive Gαi and Gαo proteins [23]. Upon activation, it inhibits adenylate cyclase, reducing intracellular cAMP levels [24] [25] [23]. Additionally, A1AR modulates various ion channels, inhibiting N-, P-, and Q-type calcium channels while activating several potassium channels [25] [23]. The receptor also activates phospholipase C (PLC) via Gβγ subunits, leading to inositol trisphosphate (IP3) production and intracellular calcium mobilization [23].

A2A Adenosine Receptor (A2AAR): In contrast to A1AR, A2AAR couples to Gαs proteins, stimulating adenylate cyclase and increasing cAMP formation [24] [22]. This receptor is highly expressed in immune cells, particularly neutrophils and regulatory T cells, where it contributes to immunosuppressive pathways [21].

A2B Adenosine Receptor (A2BAR): Like A2AAR, A2BAR stimulates adenylate cyclase through Gαs coupling but has lower affinity for adenosine [24]. It is expressed in various cell types, including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and immune cells such as bone marrow cells and basophils [21].

A3 Adenosine Receptor (A3AR): A3AR primarily couples to Gαi proteins, inhibiting adenylate cyclase and reducing cAMP levels [22]. It can also interact with Gq and Go proteins, activating phospholipase C and modulating calcium mobilization [22]. A3AR is overexpressed in numerous cancer types and demonstrates a unique dual role in regulating cell proliferation and death [22].

Table 1: Adenosine Receptor Subtypes and Their Key Signaling Pathways

| Receptor Subtype | G Protein Coupling | Primary Signaling Effects | Adenosine Affinity |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1AR | Gi/o | Inhibits adenylate cyclase ↓ cAMP, activates PLC, modulates K+ and Ca2+ channels | High (nanomolar) |

| A2AAR | Gs | Stimulates adenylate cyclase ↑ cAMP | High (nanomolar) |

| A2BAR | Gs | Stimulates adenylate cyclase ↑ cAMP | Low (micromolar) |

| A3AR | Gi/o | Inhibits adenylate cyclase ↓ cAMP, activates PLC, modulates MAPK/PI3K | Intermediate |

Expression Patterns in Normal and Neoplastic Tissues

Adenosine receptor expression varies significantly across tissues and cell types, influencing their specific roles in physiological and pathological conditions. The A2AAR protein is expressed predominantly in the colon, caudate nucleus, appendix, cerebellum, kidney, and bone marrow [21]. In immune cells, A2AAR levels are higher in neutrophils and regulatory T cells (Treg cells) [21]. A1AR demonstrates widespread distribution throughout the body, with particularly high expression in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum, thalamus, basal ganglia, brainstem, and spinal cord [23]. A1AR protein shows tissue-specific localization in Müller glial cells, oligodendrocyte precursor cells, oligodendrocytes, and excitatory neurons [21].

In cancer tissues, adenosine receptor expression often undergoes significant alterations. A3AR is overexpressed in various malignancies, including melanoma, breast, prostate, liver, pancreatic, and lung cancers, as well as lymphoma, glioblastoma, and malignant pleural mesothelioma [22]. In breast cancer specifically, A1AR has been identified as both a target and regulator of estrogen receptor α (ERα) action, mediating the proliferative effects of estradiol [26]. The A1 receptor is upregulated by estradiol in ERα-positive breast cancer cells, establishing a feed-forward loop that promotes cancer growth [26].

The Dual Nature of Adenosine Receptors in Tumor Biology

Tumor-Promoting Functions

Adenosine receptors contribute to tumor progression through multiple mechanisms that enhance cancer cell survival, proliferation, and immune evasion:

Immunosuppression: The adenosine-rich TME engages A2AAR and A2BAR on immune cells, creating potent immunosuppressive signals [21]. A2AAR activation inhibits the activity of various immune cells, including T cells and natural killer (NK) cells, thereby dampening antitumor immunity [21]. Dual A2A/A2B antagonists like M1069 have demonstrated superior suppression of protumorigenic cytokines and enhanced T-cell stimulatory activity compared to selective A2A antagonists [27].

Angiogenesis Promotion: Adenosine signaling stimulates new blood vessel formation to support tumor growth. A2BAR activation promotes the secretion of pro-angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), CXCL12, and FGF2 [21]. In melanoma models, A2BAR inhibition reduced the number of cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) expressing fibroblast activation protein (FAP) and FGF-2, consequently impairing tumor vascularization [21].

Proliferation and Survival Signaling: In breast cancer, A1AR mediates the proliferative effects of estradiol and is required for full transcriptional activity of ERα [26]. Ablation of A1AR in ERα-positive cells reduces basal and estradiol-dependent proliferation, while A1AR overexpression in ERα-negative cell lines induces proliferation [26]. Similarly, A3AR activation in certain cancer contexts leads to decreased cAMP levels, resulting in reduced phosphorylated PKB/Akt and PKA activity, thereby dysregulating Wnt signaling and promoting tumorigenesis [22].

Tumor-Suppressive Functions

Paradoxically, adenosine receptors can also trigger pathways that inhibit tumor growth and survival:

Direct Antiproliferative and Pro-apoptotic Effects: A3AR demonstrates a concentration-dependent dual functionality. At high (micromolar) concentrations, selective synthetic A3AR agonists exhibit pro-apoptotic effects in both normal and tumor cells [22]. In leukemia and melanoma models, high adenosine levels have demonstrated pro-apoptotic effects [22]. Low adenosine concentrations (<25 nM) have also been reported to inhibit tumor growth in certain contexts [22].

Immunomodulation: While generally immunosuppressive, adenosine receptors can under specific conditions modulate immune responses in ways that may limit tumor progression. A3AR activation inhibits chemotaxis, degranulation, and superoxide anion generation in eosinophils [22]. In monocytes and macrophages, A3AR inhibits TNF-α release through the NF-κB signal transduction pathway [22].

Cell Cycle Regulation: A3AR activation can inhibit tumor growth by regulating the Wnt pathway [22]. Through modulation of glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), A3AR signaling can lead to down-regulation of β-catenin and cyclin D1, key regulators of cell cycle progression [22].

Table 2: Dual Roles of Adenosine Receptors in Cancer Processes

| Cancer Process | Tumor-Promoting Effects | Tumor-Suppressive Effects |

|---|---|---|

| Immune Regulation | A2A/A2B: Suppress T-cell and NK cell activity [27] [21] | A3: Inhibits TNF-α release in macrophages [22] |

| Cell Proliferation | A1: Mediates E2/ERα-dependent proliferation in breast cancer [26] | A3: High agonist concentrations induce apoptosis [22] |

| Angiogenesis | A2B: Promotes VEGF, CXCL12, FGF2 secretion [21] | Low adenosine (<25 nM) inhibits tumor growth [22] |

| Cell Signaling | A3: Dysregulates Wnt signaling via GSK-3β [22] | A3: Regulates Wnt pathway to inhibit growth [22] |

Preliminary Investigation of Adenosine A1 Receptor in Breast Cancer Research

A1AR as a Regulator of Estrogen Receptor α Signaling

The adenosine A1 receptor plays a particularly significant role in hormone-dependent breast cancer, where it functions as both a target and regulator of estrogen receptor α (ERα) action [26]. In ERα-positive breast cancer cells, estradiol (E2) upregulates A1AR mRNA and protein levels, an effect that is reversed by the estrogen antagonist ICI 182,780 [26]. This establishes A1AR as a direct target of ERα signaling. Intriguingly, A1AR also regulates ERα expression and activity, creating a short feed-forward loop that favors breast cancer growth [26].

RNA interference-mediated ablation of A1AR in ERα-positive cells reduces both basal and E2-dependent proliferation, while A1AR overexpression in ERα-negative cell lines induces proliferation [26]. The selective A1AR antagonist, DPCPX, similarly reduces proliferation, confirming A1AR as a mediator of E2/ERα-dependent breast cancer growth [26]. Mechanistically, A1AR ablation decreases both mRNA and protein levels of ERα and consequently reduces estrogen-responsive element-dependent ERα transcriptional activity [26]. Furthermore, A1AR ablation decreases binding of ERα to the promoter of its target gene TFF1, leading to reduced TFF1 promoter activity and mRNA levels [26].

Experimental Approaches for A1AR Investigation in Breast Cancer

Computational and Bioinformatics Methods

Recent studies have employed integrated bioinformatics and computational chemistry approaches to identify critical therapeutic targets and design potent antitumor compounds targeting adenosine receptors in breast cancer [9]. These methodologies include:

Target Screening and Intersection Analysis: Initial screening and target intersection analysis identified the adenosine A1 receptor as a key candidate for breast cancer treatment [9]. Shared targets across multiple anticancer compounds were identified using online tools such as Venny, revealing common pathways in MDA-MB and MCF-7 breast cancer cell lines [9].

Molecular Docking Simulations: Molecular docking with CHARMM force fields has been used to refine ligand shapes and charge distribution while analyzing binding interactions between compounds and the human adenosine A1 receptor-Gi2 protein complex (PDB ID: 7LD3) [9]. Targets with LibDock scores over 130 were selected for further investigation, providing insights into binding mechanisms [9].

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: MD simulations using GROMACS analyzed protein-ligand binding dynamics with optimized protein structures using the AMBER99SB-ILDN force field [9]. Water molecules were modeled with the TIP3P model, and ligand charges were calculated using ACPYPE to generate GAFF force field-compatible files [9]. Simulations typically employed cubic boxes with minimum atom-box boundary distances of 0.8 nm, hydrated with SOL water at 1000 g/L density, with chloride ions replacing solvent water for electrical neutrality [9].

Pharmacophore Modeling: Construction of pharmacophore models based on binding information guides virtual screening of additional compounds with activity against A1AR [9]. These models define key structural features influencing biological activity and facilitate rational drug design.

A1AR Signaling in Breast Cancer

In Vitro Validation Methods

Experimental validation of computational findings involves comprehensive in vitro approaches:

Cell Culture Models: Estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) MCF-7 cell lines derived from human breast cancer tissue are widely used to investigate estrogen dependency and evaluate therapies targeting estrogen signaling pathways [9]. In contrast, MDA-MB cell lines, characterized by lack of estrogen receptor expression (ER-), are employed for studying aggressive breast cancer behaviors such as metastasis and drug resistance [9].

Biological Evaluation: Designed compounds are synthesized and evaluated for antitumor activity using MCF-7 breast cancer cells [9]. For instance, Molecule 10, rationally designed based on pharmacophore models, demonstrated potent antitumor activity with an IC50 value of 0.032 µM, significantly outperforming the positive control 5-FU (IC50 = 0.45 µM) [9].

Mechanistic Studies: The distribution of dynamic binding positions of compounds with targets is analyzed using software such as VMD 1.9.3 [9]. Comprehensive analysis of motion trajectories from molecular dynamics simulations, typically spanning thousands of frames with data recorded at regular intervals, facilitates understanding of molecular binding processes, dynamic behavior, and potential intermediate states [9].

Research Reagent Solutions for A1AR Investigation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Adenosine A1 Receptor Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | MCF-7 (ER+), MDA-MB (ER-) | Model systems for studying A1AR in different breast cancer subtypes [9] |

| A1AR Agonists | CCPA, N6-Cyclopentyladenosine, Capadenoson (BAY68-4986) | Selective activation of A1AR signaling pathways [25] |

| A1AR Antagonists | DPCPX, Rolofylline, CVT-124 | Inhibit A1AR function; study loss-of-function effects [26] [28] |

| Computational Tools | GROMACS, VMD, Discovery Studio | Molecular docking, dynamics simulations, visualization [9] |

| Antibodies | A1AR-specific antibodies | Detect protein expression and localization via Western blot, IHC [26] |

| Gene Silencing Tools | siRNA against ADORA1 | Knockdown A1AR expression for functional studies [26] |

Therapeutic Implications and Future Directions

Targeting Adenosine Receptors in Cancer Therapy

The dual nature of adenosine receptors in tumor biology presents both challenges and opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Several strategies have emerged:

Receptor Antagonists: Selective A1AR antagonists such as DPCPX have demonstrated efficacy in reducing breast cancer proliferation [26]. Dual A2A/A2B antagonists like M1069 counteract immunosuppressive mechanisms of adenosine and reduce tumor growth in vivo, particularly in adenosine-high/CD73hi tumor models such as 4T1 breast tumors [27].

Receptor Agonists: Interestingly, A3AR agonists demonstrate concentration-dependent antitumor effects, with high (micromolar) concentrations triggering apoptotic pathways in cancer cells [22]. This suggests that context-specific agonist administration might harness the tumor-suppressive potential of adenosine receptors.

Combination Therapies: Adenosine receptor antagonists enhance the efficacy of existing treatments. M1069 improved the antitumor activity of bintrafusp alfa (BA) and cisplatin in syngeneic adenosinehi/CD73hi 4T1 breast tumor models [27]. Similarly, combining adenosine receptor inhibition with immunotherapy may overcome resistance mechanisms in the TME [21].

Experimental Workflow for A1AR-Targeted Drug Discovery

Drug Discovery Workflow

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite promising developments, several challenges remain in targeting adenosine receptors for cancer therapy. The dual nature of these receptors, particularly A3AR and A1AR, necessitates careful context-specific therapeutic approaches. Tissue-specific distribution and expression patterns of adenosine receptors complicate systemic administration of targeted therapies. Furthermore, the complex interplay between different adenosine receptor subtypes in the TME may lead to compensatory mechanisms and treatment resistance.

Future research should focus on developing more selective modulators of adenosine receptors, optimizing combination strategies with conventional therapies and immunotherapy, and identifying biomarkers that predict response to adenosine-targeted therapies. Additionally, advanced drug delivery systems that enable tissue-specific targeting may enhance therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target effects.

In conclusion, adenosine receptors, particularly the A1 receptor in breast cancer, represent promising therapeutic targets whose dual nature in tumor promotion and suppression reflects the complexity of cancer biology. Through integrated computational, experimental, and therapeutic approaches, targeting these receptors may yield innovative strategies for cancer treatment.

The adenosine A1 receptor (A1R), a class A G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR), has emerged as a significant regulator in the tumor microenvironment with particularly intriguing implications for breast cancer pathogenesis. Within the context of a broader thesis on the preliminary investigation of A1R in breast cancer research, this technical review synthesizes current understanding of how A1R signaling impacts three fundamental cancer hallmarks: cellular proliferation, apoptotic evasion, and angiogenesis. Adenosine, the endogenous orthosteric ligand for A1R, accumulates to high concentrations in hypoxic tumor microenvironments through the enzymatic conversion of extracellular ATP by CD39 and CD73 [10]. This review examines the mechanistic basis for A1R-mediated oncogenic signaling and its potential as a therapeutic target, providing detailed experimental frameworks for researchers investigating GPCR biology in cancer systems.

A1R Signaling in Breast Cancer Proliferation

Molecular Mechanisms Linking A1R to Proliferative Signaling

The adenosine A1 receptor exhibits a complex functional relationship with estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) signaling in breast cancer, forming a feed-forward loop that drives cellular proliferation. Research has demonstrated that A1R functions as both a target and regulator of ERα action [6]. In ERα-positive breast cancer cells, estradiol (E2) significantly upregulates A1R mRNA and protein expression, an effect that is reversible by the ER antagonist ICI 182,780 [6]. This establishes A1R as a direct transcriptional target of the ligand-activated ERα.

The proliferative influence of A1R signaling has been validated through multiple experimental approaches. Small interfering RNA (siRNA)-mediated ablation of Adora1 (the gene encoding A1R) in ERα-positive breast cancer cells substantially reduces both basal and E2-dependent proliferation [6]. Conversely, A1R overexpression in ERα-negative cell lines induces proliferative capacity, while treatment with the selective A1R antagonist DPCPX (8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine) effectively suppresses proliferation in A1R-expressing systems [6]. Intriguingly, A1R ablation decreases both mRNA and protein levels of ERα itself, consequently diminishing estrogen-responsive element (ERE)-dependent transcriptional activity and expression of endogenous ERα target genes such as TFF1 [6].

Table 1: Experimental Evidence for A1R-Mediated Proliferation in Breast Cancer

| Experimental System | Intervention | Key Findings | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 ERα+ cells | siRNA Adora1 ablation | Reduced basal and E2-dependent proliferation | [6] |

| ERα- cell line | A1R overexpression | Induced proliferation | [6] |

| ERα+ breast cancer cells | DPCPX (A1R antagonist) | Decreased proliferation | [6] |

| MCF-7 cells | Compound 10 (novel A1R-targeting molecule) | IC50 = 0.032 µM (vs. 0.45 µM for 5-FU control) | [9] |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating A1R-Mediated Proliferation

Protocol 1: siRNA-Mediated A1R Ablation and Proliferation Assessment

- Cell Lines: MCF-7 (ERα-positive breast cancer cells)

- A1R Knockdown: Transfect with 50-100 nM validated Adora1-specific siRNA using appropriate transfection reagent

- Controls: Non-targeting siRNA and mock transfection controls

- Proliferation Assay: Assess cell viability at 24, 48, 72, and 96h post-transfection using MTT or CCK-8 assays

- Hormone Stimulation: Treat with 10 nM E2 (with/without 100 nM ICI 182,780) 24h post-transfection

- Validation: Confirm A1R knockdown via qPCR (mRNA) and Western blot (protein) [6]

Protocol 2: A1R Antagonism Studies

- Compound: DPCPX (selective A1R antagonist) at concentrations ranging from 10 nM to 10 µM

- Treatment Duration: 24-96 hours

- Endpoint Measurements: Cell counting, 3H-thymidine incorporation, or flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle distribution [6]

A1R Modulation of Apoptotic Pathways

A1R Signaling and Cell Death Regulation

The adenosine A1 receptor demonstrates context-dependent effects on apoptotic pathways in breast cancer systems. In MCF-7 breast cancer cells, treatment with an A1R agonist modulates the expression of key apoptosis regulators including p53 and multiple caspases [29]. Specifically, studies have documented that A1R agonist treatment influences the expression levels of caspase-3, -8, and -9, core components of the apoptotic machinery [29]. These findings position A1R as a potential regulator of programmed cell death decisions in breast cancer cells, though the precise mechanisms appear to vary based on cellular context and receptor expression levels.

The interplay between A1R and apoptotic regulation extends to other cancer types, suggesting potential conserved mechanisms. In oral squamous cell carcinoma, progression from normal mucosa to dysplasia and invasive carcinoma is accompanied by significant increases in apoptotic indices alongside parallel increases in proliferation and angiogenesis [30]. This coordinated regulation suggests that A1R signaling may function within broader networks that balance cell death and survival decisions in epithelial malignancies.

Table 2: A1R-Mediated Effects on Apoptosis Regulators

| Apoptosis Component | A1R-Mediated Effect | Experimental System | Functional Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| p53 expression | Modulated by A1R agonist | MCF-7 cells | Altered transcription of p53 target genes |

| Caspase-3, -8, -9 | Expression changes | MCF-7 cells | Modified execution of apoptotic programs |

| Apoptotic Index | Increases with disease progression | Oral tissue carcinogenesis | Balanced with proliferation increases |

Experimental Protocols for Apoptosis Analysis

Protocol 3: A1R Modulation and Apoptosis Assessment

- Cell Preparation: Seed MCF-7 cells in 6-well plates (2×10^5 cells/well)

- A1R Modulation: Treat with A1R agonist (e.g., CCPA; 100 nM) or antagonist (DPCPX; 1 µM) for 24-48h

- Apoptosis Detection:

- Annexin V/PI Staining: Use commercial apoptosis detection kit per manufacturer's protocol

- Caspase Activity: Measure using fluorometric caspase activity assays

- Western Blotting: Analyze cleaved PARP, caspases, and p53 expression

- Gene Expression: Quantify mRNA levels of p53 and caspase genes via RT-qPCR [29]

Protocol 4: In Situ Apoptosis Detection in Tissue Models

- Tissue Preparation: Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections (5 µm thickness)

- Apoptosis Labeling: Employ TUNEL assay (in-situ end-labeling of DNA fragments)

- Visualization: Enzyme-based colorimetric detection or fluorescence labeling

- Quantification: Count apoptotic cells in 10 random high-power fields (400× magnification) [30]

A1R Involvement in Tumor Angiogenesis

Angiogenic Signaling Mediated by A1R

While direct evidence specifically linking A1R to angiogenesis in breast cancer requires further investigation, the broader context of adenosine receptor signaling supports a likely role in promoting tumor vascularization. In multiple cancer models, adenosine signaling has been demonstrated to stimulate angiogenesis through various mechanisms, primarily attributed to the A2A and A2B receptor subtypes [29]. These pro-angiogenic effects include upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and other angiogenic factors.

The methodology for assessing angiogenesis in relation to adenosine signaling has been established in other tissue contexts. In oral carcinogenesis, angiogenesis measurement typically involves immunostaining for endothelial cell markers followed by microvessel density quantification [30]. This approach could be readily adapted to breast cancer models to specifically elucidate A1R contributions. The significant increase in vascularity observed during progression from normal oral mucosa through dysplasia to invasive carcinoma demonstrates the importance of angiogenesis in epithelial cancer development [30].

Experimental Protocols for Angiogenesis Assessment

Protocol 5: Microvessel Density Quantification

- Tissue Staining: Perform immunohistochemistry on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded sections using von Willebrand factor (vWF) or CD31 antibodies to highlight endothelial cells

- Microvessel Counting: Identify vascular hotspots at 100× magnification, then count microvessels in three 200× fields

- Quantification Criteria: Any brown-staining endothelial cell or cell cluster clearly separate from adjacent microvessels counts as a single microvessel

- Analysis: Calculate mean microvessel density ± standard deviation across samples [30]

Protocol 6: In Vitro Angiogenesis Assays

- Endothelial Cell Culture: Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) or other relevant endothelial cell types

- Conditioned Media Collection: Culture breast cancer cells with A1R modulators, collect conditioned media after 48h

- Tube Formation Assay: Seed endothelial cells on Matrigel-coated plates, treat with conditioned media, quantify tube formation after 4-16h

- Analysis: Measure total tube length, number of branches, and enclosed areas using image analysis software

Structural Insights and Therapeutic Targeting of A1R

A1R Allosteric Modulators as Therapeutic Opportunities

Recent structural biology advances have revealed novel approaches for targeting A1R with improved selectivity. The crystal structure of A1R bound to adenosine and the positive allosteric modulator MIPS521 ([2-amino-4-(3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl)thiophen-3-yl)(4-chlorophenyl)methanone]) in complex with a Gi2 heterotrimer has been resolved [31]. This structure reveals an extrahelical lipid–detergent-facing allosteric binding pocket involving transmembrane helixes 1, 6 and 7, distinct from the orthosteric adenosine-binding site [31]. Molecular dynamics simulations and kinetic binding experiments indicate that MIPS521 stabilizes the adenosine–receptor–G protein complex, providing a mechanism for its positive allosteric modulation [31].

This structural insight enables structure-based drug design of non-opioid analgesic agents that are specific to disease contexts [31], and similar approaches could be applied to breast cancer therapeutics. Positive allosteric modulators of A1R represent a promising strategy because they enhance the receptor's response to endogenous adenosine only in tissues and disease states where adenosine concentrations are elevated, potentially offering improved therapeutic windows compared to orthosteric agonists [10].

Computational Approaches for A1R-Targeted Drug Discovery

Protocol 7: Molecular Docking and Dynamics for A1R Ligand Discovery

- Protein Preparation: Retrieve A1R structure (PDB: 7LD3), remove crystallographic waters, add hydrogen atoms, assign charges

- Ligand Preparation: Draw candidate compounds, optimize geometry, generate 3D conformers

- Molecular Docking: Use AutoDock Vina or similar software with binding pocket defined by allosteric site coordinates

- Molecular Dynamics: Run simulations using GROMACS with AMBER99SB-ILDN force field for proteins and GAFF for ligands

- Analysis: Calculate binding free energies, monitor conformational changes, identify key interacting residues [9]

Protocol 8: Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

- Pharmacophore Generation: Define spatial features based on known active compounds (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings)

- Database Screening: Filter compound libraries (ZINC, PubChem) against pharmacophore model

- Compound Selection: Prioritize compounds with high fit values and favorable drug-like properties

- Experimental Validation: Test selected compounds in binding and functional assays [9]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Investigating A1R in Breast Cancer

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Experimental Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| A1R Agonists | CCPA, CPA, ADAC | Activate A1R signaling; study downstream effects | Use concentration range 1 nM-1 µM; monitor receptor internalization |

| A1R Antagonists | DPCPX, CPT | Inhibit A1R signaling; validate receptor-specific effects | DPCPX selective at concentrations <100 nM |

| Allosteric Modulators | MIPS521, T-62, TRR469 | Enhance (PAM) or inhibit (NAM) endogenous adenosine effects | Display probe dependence; test with multiple orthosteric ligands |

| Antibodies | Anti-A1R (various hosts), anti-vWF, anti-Ki-67 | Detect protein expression, localization; stain blood vessels, proliferating cells | Validate specificity using knockout controls or competing peptides |

| Cell Lines | MCF-7 (ERα+), MDA-MB-231 (ERα-) | Model different breast cancer subtypes | Monitor receptor expression across passages |

| siRNA/shRNA | Adora1-targeting sequences | Knockdown A1R expression; study loss-of-function | Include multiple distinct sequences to control for off-target effects |

| Computational Tools | GROMACS, AutoDock Vina, SwissTargetPrediction | Molecular dynamics, docking, target prediction | Use updated force fields; validate predictions experimentally |

Visualizing A1R Signaling and Research Approaches

A1R Signaling Pathway in Breast Cancer

Experimental Workflow for A1R Research

The adenosine A1 receptor represents a multifaceted regulator in breast cancer biology, simultaneously influencing proliferative signaling through integration with ERα pathways, modulating apoptotic responses, and potentially contributing to angiogenic processes. The experimental frameworks and technical approaches detailed in this review provide researchers with comprehensive methodologies for investigating A1R function in breast cancer models. The emerging structural understanding of A1R and development of allosteric modulators offer promising avenues for therapeutic intervention with potentially improved selectivity. Future research directions should include elucidating A1R interactions with other adenosine receptor subtypes in the tumor microenvironment, exploring A1R roles in different breast cancer molecular subtypes, and validating A1R-targeting strategies in more complex preclinical models that recapitulate the hypoxic, adenosine-rich tumor microenvironment.

Advanced Methodologies for A1R Target Screening and Compound Design in Breast Cancer

Integrated Bioinformatics and Computational Chemistry for A1R Target Identification

The preliminary investigation of the adenosine A1 receptor (A1R) within breast cancer research represents a promising frontier for therapeutic intervention. This technical guide delineates an integrated framework employing bioinformatics and computational chemistry methodologies for the identification and validation of A1R as a molecular target. We provide detailed protocols for structural analysis, molecular docking, dynamics simulations, and data integration, supplemented by structured tables of quantitative data and visual workflows. This approach aims to establish a foundational pipeline for researchers targeting A1R in the context of breast cancer pathogenesis and treatment.

G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) like the adenosine A1 receptor are critical regulators of cellular signaling and represent a major class of drug targets. The A1R preferentially couples to inhibitory Gi/o heterotrimeric G proteins and has been implicated in numerous disease pathways [32]. Within breast cancer, a complex and prevalent health concern affecting millions worldwide, understanding receptor-mediated signaling pathways offers significant potential for therapeutic advancement [33]. Breast cancer encompasses heterogeneous molecular subtypes with varying receptor expressions (estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 receptors), with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) representing an aggressive subtype with limited treatment options and poor prognosis [34]. The investigation of alternative molecular targets like A1R is thus clinically imperative.

The endogenous agonist for A1R is adenosine, which plays a role in modulating pain pathways and has been investigated as a non-opioid analgesic target [35]. The structure of the adenosine-bound human A1R-Gi complex has been resolved, revealing critical molecular interactions at the orthosteric binding site mediated via transmembrane domains 1 and 2, and intracellular engagement with G proteins [32] [35]. This structural knowledge enables targeted investigation of A1R's role in breast cancer through computational means, integrating bioinformatic analyses of expression data with computational chemistry approaches for ligand discovery and optimization.

Bioinformatics Approaches for A1R Target Analysis

Transcriptomic Data Integration and Analysis

The analysis of A1R expression across breast cancer subtypes requires robust integration of transcriptomic data. RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data from public repositories like the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) often originate from different platforms (e.g., polyA-selected or rRNA-depleted libraries), creating challenges for comparative analysis.

Experimental Protocol: Transcriptomic Data Integration using GEDI R Package

- Data Import: Use the

ReadGEfunction from the GEDI package to import gene expression datasets from multiple sources (e.g., microarray and RNA-seq) [36]. - Reannotation and Merging: Execute the

GEDIfunction to automatically reannotate all gene identifiers to a common standard (e.g., official gene symbols) and merge the datasets into a single expression matrix [36]. - Batch Effect Correction: Apply the

BatchCorrectionfunction to remove non-biological technical variation between datasets using established algorithms like ComBat [36]. - Integration Verification: Utilize

VerifyGEDIto confirm successful data integration. This function employs principal component analysis (PCA) to visualize batch effect removal and uses a logistic regression model with forward stepwise feature selection to validate the integration [36].

For RNA-seq data specifically, gene-level expression estimates can be obtained using high-speed transcript quantification tools like Kallisto. A study on ovine macrophages demonstrated that a combination of reference transcriptome filtering and a ratio-based correction can create equivalent expression profiles from both polyA-selected and rRNA-depleted libraries, enabling meta-analysis [37].

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for transcriptomic data integration and A1R expression analysis:

Structural Bioinformatics and Homology Modeling

The cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of the human A1R in complex with adenosine and heterotrimeric Gi2 protein (PDB ID: 7LD3, resolution: 3.20 Å) provides a foundational resource for structure-based drug design [35]. This structure reveals the orthosteric binding site for adenosine and an extrahelical lipid-facing allosteric binding pocket for compounds like the positive allosteric modulator MIPS521 [35].

Experimental Protocol: Structure-Based Analysis of A1R

- Retrieval of A1R Structure: Download the atomic coordinates for the A1R-Gi complex (7LD3) from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/7LD3) [35].

- Structure Preparation: Using molecular visualization software (e.g., PyMOL, UCSF Chimera), prepare the protein structure by removing the G-protein heterotrimer if desired for ligand docking studies, adding hydrogen atoms, and assigning appropriate protonation states to residues in the binding pocket.

- Binding Site Analysis: Characterize the orthosteric and allosteric binding pockets. Key residues in the orthosteric site can be identified from the structural data, while the allosteric site involves transmembrane helices 1, 6, and 7 [35].

- Molecular Docking: Perform docking simulations of known ligands (e.g., adenosine, MIPS521) to validate the protocol and identify key interacting residues. This serves as a positive control before virtual screening of compound libraries.

Table 1: Key Structural Features of the Adenosine A1 Receptor (PDB 7LD3)

| Feature | Description | Functional/Experimental Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Endogenous Agonist | Adenosine (ADN) | Serves as the natural ligand for orthosteric binding site [35] |

| Allosteric Modulator | MIPS521 (XTD) | Binds extrahelical pocket; stabilizes active receptor-G protein complex [35] |

| G-Protein Coupling | Heterotrimeric Gi2 | Preferential coupling to inhibitory G proteins; structure reveals engagement interface [32] [35] |

| Allosteric Pocket | TM1, TM6, TM7 | Lipid-detergent-facing pocket; target for allosteric drug design [35] |

| Resolution | 3.20 Å | Determined by cryo-EM single-particle analysis [35] |

Computational Chemistry Workflows for A1R Ligand Discovery

Virtual Screening and Molecular Docking

Virtual screening leverages chemoinformatics to identify hit compounds from large chemical libraries by predicting their binding affinity to a target protein like A1R.

Experimental Protocol: Virtual Screening against A1R

- Library Curation: Compile a virtual library of compounds. These can be commercially available libraries (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL) or custom-designed libraries based on known A1R ligands or specific scaffolds [38].

- Ligand Preparation: Prepare the library compounds by generating plausible 3D conformations, optimizing geometry, and assigning correct tautomeric and protonation states at physiological pH.

- Molecular Docking: Dock each compound from the prepared library into the target binding site(s) of the prepared A1R structure (from Protocol 2.2). Grid parameters should encompass the entire orthosteric and/or allosteric binding pockets.

- Scoring and Ranking: Use the docking software's scoring function to rank the compounds based on their predicted binding free energy (e.g., ΔG in kcal/mol). Top-ranked compounds are selected for further analysis.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

MD simulations provide insights into the dynamic behavior of the A1R-ligand complex, complementing the static picture from crystal structures.

Experimental Protocol: MD Simulation of A1R-Ligand Complex

- System Setup: Place the A1R-ligand complex (e.g., from docking studies) in a phospholipid bilayer mimicking the cell membrane. Solvate the system with water molecules and add ions to neutralize the system and achieve physiological concentration.

- Energy Minimization: Minimize the energy of the entire system to remove steric clashes and unfavorable contacts.