Synergistic Strategies: Integrating Pharmacophore Modeling with Molecular Docking to Revolutionize Virtual Screening in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integrated approach of pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) and docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) in modern drug discovery.

Synergistic Strategies: Integrating Pharmacophore Modeling with Molecular Docking to Revolutionize Virtual Screening in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the integrated approach of pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) and docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) in modern drug discovery. It explores the foundational concepts of both methods, detailing how their synergistic application creates robust workflows for hit identification, lead optimization, and polypharmacology. We examine practical methodologies, address common challenges and optimization strategies, and present validation studies comparing the performance of integrated versus standalone approaches. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current knowledge to offer best-practice guidelines for implementing these powerful computational techniques to accelerate the development of novel therapeutics, from initial screening to overcoming resistance in complex diseases.

The Core Concepts: Deconstructing Pharmacophore Modeling and Molecular Docking

In medicinal chemistry, a pharmacophore is defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [1] [2] [3]. This abstract representation captures the essential, three-dimensional arrangement of molecular interaction capabilities shared by active compounds, independent of their specific chemical scaffold [4]. It is a conceptual framework that distinguishes the key functional components responsible for biological activity from the structural carrier of those features.

The pharmacophore concept has evolved significantly from its early origins. While often historically linked to Paul Ehrlich's work on "toxophores," modern usage was popularized by Lemont Kier in the late 1960s and early 1970s [2] [4]. Today, pharmacophore modeling is an indispensable component of computer-aided drug design (CADD), enabling critical tasks such as virtual screening, lead optimization, and de novo design by focusing on the common molecular interaction capacities of a group of compounds towards their target structure [1] [3].

Essential Steric and Electronic Features

A pharmacophore model is constructed from a set of fundamental, abstract chemical features that represent the ability to form specific non-bonding interactions with a biological target. These features generalize across different chemical functional groups that share similar interaction profiles.

Table 1: Core Pharmacophore Features and Their Interaction Types

| Feature Type | Geometric Representation | Complementary Feature Type(s) | Interaction Type(s) | Structural Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen-Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Vector or Sphere | HBD | Hydrogen-Bonding | Amines, Carboxylates, Ketones, Alcoholes, Fluorine Substituents [3] |

| Hydrogen-Bond Donor (HBD) | Vector or Sphere | HBA | Hydrogen-Bonding | Amines, Amides, Alcoholes [3] |

| Aromatic (AR) | Plane or Sphere | AR, PI | π-Stacking, Cation-π | Any aromatic Ring [3] |

| Positive Ionizable (PI) | Sphere | AR, NI | Ionic, Cation-π | Ammonium Ion, Metal Cations [3] |

| Negative Ionizable (NI) | Sphere | PI | Ionic | Carboxylates [3] |

| Hydrophobic (H) | Sphere | H | Hydrophobic Contact | Halogen Substituents, Alkyl Groups, Alicycles, weakly or non-polar aromatic rings [3] |

These features are not specific atoms or functional groups, but rather spatial domains where a particular interaction is likely to occur. Vector-based representations are typically used for directed interactions like hydrogen bonding, defining both location and orientation, while spherical representations are used for undirected interactions like hydrophobic and ionic contacts [3]. The spatial relationship between these features—defined by distances, angles, and torsions—is as critical as the features themselves for ensuring accurate molecular recognition.

Pharmacophore Model Generation: Methods and Protocols

Pharmacophore models can be developed through several approaches, with the choice of method depending on the available structural and ligand data for the biological target.

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based methods derive the pharmacophore model directly from the three-dimensional structure of a target protein, typically in complex with a ligand.

Experimental Protocol: Structure-Based Model Generation from a Protein-Ligand Complex

Step 1: Protein and Ligand Preparation

- Obtain the 3D structure of the protein-ligand complex from a source like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [5].

- Using software such as Discovery Studio [5], prepare the structure by:

- Removing extraneous water molecules.

- Completing missing amino acid residues and side chains.

- Correcting bond connectivity and order.

- Adding hydrogen atoms and assigning partial charges.

- Performing energy minimization using a force field like CHARMM [5].

Step 2: Automated Feature Identification

- Employ the "Receptor-Ligand Pharmacophore Generation" module in Discovery Studio [5] or an equivalent tool (e.g., LigandScout [1]).

- Configure the protocol to consider the six standard pharmacophore features: Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA), Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD), Positive Ionizable (PI), Negative Ionizable (NI), Hydrophobic (H), and Aromatic Ring (AR) [5].

- Set parameters, for example: Minimum Features = 4, Maximum Features = 6, Maximum Pharmacophores to generate = 10 [5].

- Execute the protocol to automatically analyze the ligand-protein interactions and map the essential pharmacophore features.

Step 3: Model Validation and Refinement

- Validate the generated model using a decoy set containing known active and inactive compounds [5].

- Screen the validation set and calculate enrichment metrics such as the Enrichment Factor (EF) and the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUC) [5].

- A reliable model typically has an AUC > 0.7 and an EF > 2 [5].

- Manually refine the model by adding or removing features based on biological intuition or additional structural data.

Diagram 1: Workflow for generating a structure-based pharmacophore model.

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

When the 3D structure of the target is unavailable, ligand-based methods can be used to infer the pharmacophore from a set of known active ligands.

Experimental Protocol: Ligand-Based Common Feature Pharmacophore Generation

Step 1: Training Set Selection and Preparation

- Select a structurally diverse set of ligands (typically 15-50) with known activity against the target [6] [7].

- For each ligand, generate a set of low-energy conformations to account for flexibility, ensuring the set is likely to contain the bioactive conformation [2]. Tools like iConfGen or ConfGen can be used for this purpose [7].

Step 2: Molecular Superimposition and Common Feature Perception

- Use software such as PharmaGist or the Common Feature Pharmacophore Generation module in Discovery Studio [8].

- The algorithm will systematically superimpose ("fit") the low-energy conformations of all training set molecules [2].

- The goal is to identify the maximal common set of pharmacophoric features shared by all or most active compounds in their aligned state [4].

Step 3: Hypothesis Generation and Scoring

- The software produces multiple pharmacophore hypotheses, each scored based on how well it aligns the training set molecules and the geometric fit of the common features [8].

- Select the top-ranked hypothesis for further validation.

Step 4: Model Validation

- Validate the model by screening a test set containing both active and inactive compounds [2] [8].

- Assess the model's ability to correctly classify actives (sensitivity) and inactives (specificity). Use metrics like the Fβ-score (emphasizing true positives) and FSpecificity-score (emphasizing true negatives) for virtual screening contexts [6].

Integrated Application Notes

Integrating pharmacophore modeling with other computational techniques creates a powerful workflow for drug discovery, particularly in virtual screening.

Application Note: Integrated Virtual Screening for Dual-Target Inhibitors

A 2025 study successfully identified dual inhibitors for VEGFR-2 and c-Met, two critical cancer targets, using an integrated computational approach [5].

- Objective: Identify novel dual-target inhibitors from the ChemDiv database (1.28 million compounds) with potential to overcome tumor resistance.

- Integrated Workflow:

- Drug-Likeness Filtering: Initial filtering based on Lipinski's and Veber's rules, followed by ADMET prediction [5].

- Pharmacophore Screening: Structure-based pharmacophore models for VEGFR-2 and c-Met were built from PDB complexes and used to screen the filtered database [5].

- Molecular Docking: Compounds passing the pharmacophore filter were docked into the active sites of both VEGFR-2 and c-Met using molecular docking software to assess binding affinity and pose [5].

- MD Simulations & MM/PBSA: Top hits from docking underwent molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (e.g., 100 ns) to evaluate complex stability, followed by MM/PBSA calculations to estimate binding free energies [5].

- Key Outcome: The workflow identified 18 hit compounds. Two compounds, 17924 and 4312, showed superior binding free energies compared to positive controls, marking them as promising candidates [5].

This case demonstrates how pharmacophore modeling serves as an efficient pre-filter before more computationally intensive techniques like docking and MD simulations, streamlining the identification of novel lead compounds.

Table 2: Summary of Key Experimental Results from Integrated Virtual Screening [5]

| Experimental Stage | Key Action/Metric | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Database | Compounds from ChemDiv | ~1.28 Million |

| Drug-Likeness Filter | Application of Lipinski/Veber rules & ADMET | Reduced candidate pool |

| Pharmacophore Screening | Screening with validated VEGFR-2/c-Met models | Hit list for docking |

| Molecular Docking | Docking into VEGFR-2 and c-Met active sites | 18 potential dual-target inhibitors identified |

| MD/MM-PBSA | Binding free energy calculation for top hits | Compounds 17924 & 4312 showed superior energies vs. controls |

Application Note: QPhAR - A Machine Learning-Enhanced Workflow

A novel approach called Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship (QPhAR) integrates machine learning with traditional pharmacophore modeling for improved predictive power [6] [7].

- Objective: Move beyond qualitative pharmacophore screening to build robust, quantitative models that predict biological activity directly from pharmacophore features.

- Protocol:

- Data Preparation: A dataset of molecules with known activity (e.g., IC₅₀, Kᵢ) is split into training and test sets [6].

- QPhAR Model Training: The algorithm generates a consensus "merged-pharmacophore" from the training set. Input pharmacophores are aligned to this consensus, and their spatial information is used to train a machine learning model to predict activity [7].

- Pharmacophore Refinement: The trained QPhAR model automatically identifies and refines the features most critical for activity, creating a model with higher discriminatory power than those derived from simple common feature perception [6].

- Virtual Screening & Ranking: The refined pharmacophore is used for virtual screening. Hits are then ranked by their predicted activity from the QPhAR model, providing a prioritized list for experimental testing [6].

- Key Outcome: This end-to-end automated workflow has been validated on targets like the hERG K⁺ channel, showing robust performance even with small dataset sizes (15-20 training samples), making it highly suitable for lead optimization [6] [7].

Diagram 2: QPhAR automated workflow for quantitative pharmacophore modeling and screening.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Software Solutions for Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

| Software / Tool | Type | Primary Function in Pharmacophore Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery Studio | Commercial Suite | Comprehensive environment for structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore generation, validation, and virtual screening [5]. | Integrated drug discovery workflows. |

| MOE | Commercial Suite | All-in-one platform for molecular modeling, including pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, and QSAR [1] [9]. | Integrated drug discovery workflows. |

| Schrödinger Phase | Commercial Tool | Intuitive pharmacophore modeling for both ligand- and structure-based design; includes screening of prepared commercial libraries [9] [10]. | Virtual screening, scaffold hopping. |

| LigandScout | Commercial/Open | Advanced structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, with capabilities for 3D-QSAR and virtual screening [1]. | Structure-based design, model validation. |

| PharmaGist | Web Server | Ligand-based pharmacophore alignment from a set of input active molecules [8]. | Quick, online ligand-based hypothesis generation. |

| ZINCPharmer | Web Server | Online tool for pharmacophore-based screening of the ZINC database of purchasable compounds [8]. | Rapid virtual screening of commercial compounds. |

| DataWarrior | Open-Source | Cheminformatics program supporting 3D pharmacophore features and QSAR model development with machine learning [9]. | Open-source analysis and modeling. |

Molecular Docking as a Structure-Based Prediction Tool for Ligand Poses and Affinities

Molecular docking is an indispensable computational method in structural biology and drug discovery, primarily used to predict the binding conformation (pose) and affinity of a small molecule (ligand) within a target macromolecule's binding site [11] [12]. By simulating the molecular recognition process, docking provides critical insights into intermolecular interactions, thereby accelerating rational drug design and the identification of novel therapeutic candidates [11]. The core objectives of molecular docking are to predict the optimal binding geometry of a ligand-receptor complex and to estimate the binding strength through scoring functions [12]. This protocol outlines the fundamental principles, methodological considerations, and practical applications of molecular docking, with an emphasis on its integration within a broader structure-based drug discovery framework, particularly in conjunction with pharmacophore-based virtual screening.

Core Principles and Methodological Components

The molecular docking process consists of two primary computational challenges: a conformational search of the ligand's orientational and internal degrees of freedom within the binding site, and scoring of the generated poses to identify the most likely binding mode and estimate binding affinity [11].

Conformational Search Algorithms

Docking programs employ various algorithms to efficiently explore the vast conformational space of the ligand. Table 1 summarizes the main approaches.

Table 1: Common Conformational Search Algorithms in Molecular Docking

| Algorithm Type | Description | Key Characteristics | Example Programs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic Search | Systematically varies rotatable bonds by fixed increments to explore all possible conformations [12]. | Exhaustive but computationally expensive; pruning algorithms avoid atomic clashes [11] [12]. | Glide [12], FRED [12] |

| Incremental Construction | Fragments the ligand, docks rigid core, and systematically rebuilds flexible components [11] [12]. | Reduces complexity by focusing on flexible linkers between rigid fragments [11]. | FlexX [12], DOCK [12] |

| Stochastic Methods | Uses random sampling and probabilistic rules to explore conformational space [11] [12]. | Avoids local minima; computationally intensive for large compound libraries [11]. | AutoDock [11] [12], GOLD [11] [12] |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | A stochastic method that encodes torsions in "chromosomes," applies evolutionary principles (mutation, crossover) [11] [12]. | Uses scoring function as fitness criteria; selects best poses over generations [11]. | AutoDock [11], GOLD [11] |

Scoring Functions

Scoring functions are mathematical models used to predict the binding affinity of a ligand pose by evaluating the intermolecular interactions within the complex. They aim to approximate the binding free energy (ΔG_binding) [12]. The development of more accurate and generalizable scoring functions remains an active area of research, with recent efforts incorporating machine learning techniques to improve predictions [12].

Integrated Docking and Pharmacophore Screening Workflow

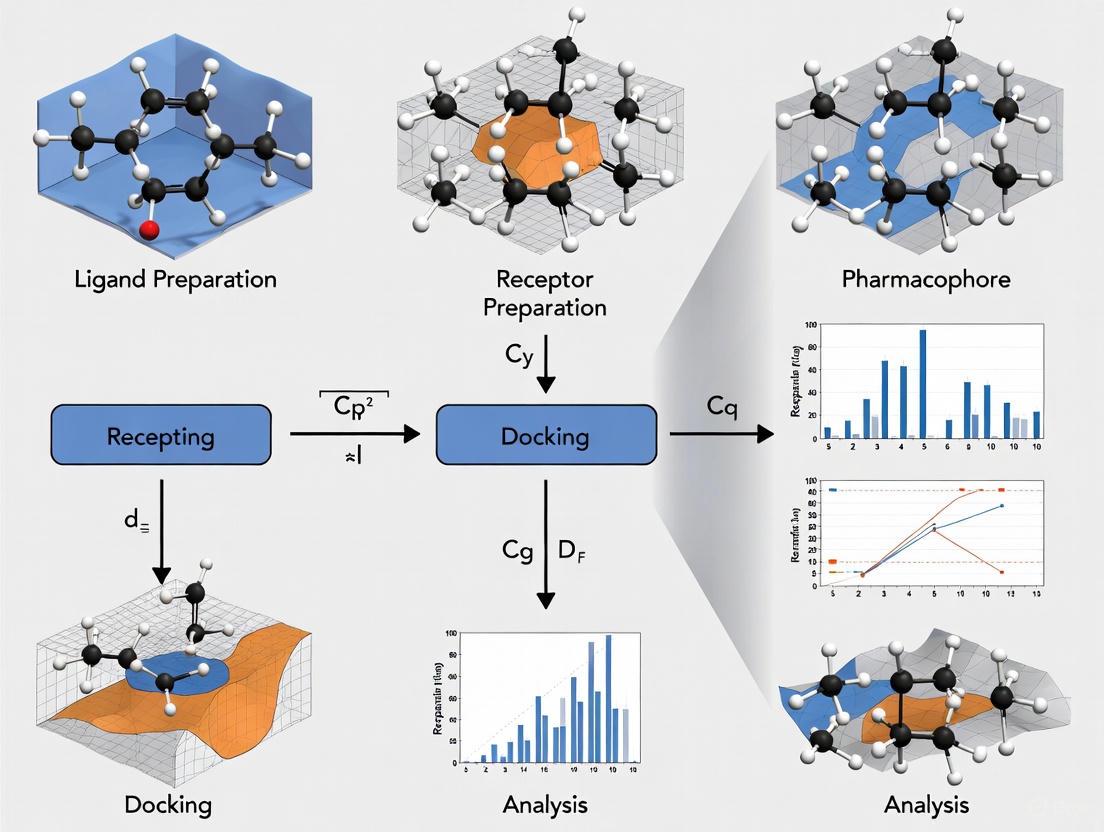

Combining molecular docking with pharmacophore-based virtual screening creates a powerful, multi-stage pipeline for lead identification. The pharmacophore model acts as an initial filter to rapidly eliminate compounds lacking essential chemical features, while docking provides a detailed, structure-based assessment of binding. The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow.

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for pharmacophore-based virtual screening and molecular docking in drug discovery. Key steps include structure preparation, pharmacophore screening, molecular docking, and post-docking analysis.

Protocol: Integrated Pharmacophore and Docking Screening

Objective: To identify potential lead compounds by sequentially applying pharmacophore-based filtering and molecular docking.

Step 1: Target and Ligand Preparation

- Protein Preparation: Retrieve the three-dimensional structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Using a tool like Schrödinger's Protein Preparation Wizard, add hydrogen atoms, assign bond orders, correct for missing residues, and optimize the hydrogen bond network. Finally, perform energy minimization using a forcefield such as OPLS_2005 [13] [14].

- Pharmacophore Model Generation: Extract the co-crystallized ligand from the protein's active site. Using its structural features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, aromatic rings), create a pharmacophore query model. Servers like Pharmit can be used for this purpose [13] [14].

Step 2: Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

- Screening: Use the generated pharmacophore model to screen large commercial or in-house chemical databases (e.g., ZINC, PubChem, Enamine) [13] [14].

- Filtering: Apply filters such as Lipinski's Rule of Five (Molecular Weight < 500, H-bond donors < 5, H-bond acceptors < 10, LogP < 5) to the resulting hits to prioritize drug-like compounds [13] [14].

Step 3: Molecular Docking

- Ligand Preparation: Prepare the filtered hit compounds using a tool like LigPrep. This step involves generating possible tautomers and ionization states at physiological pH (e.g., 7.0 ± 0.5), and performing energy minimization [13] [14].

- Grid Generation: Define the docking grid around the binding site of the prepared protein structure. The grid center is typically based on the coordinates of the native ligand (e.g., X, Y, Z: 8.32, 6.48, 9.1 for EGFR) [13] [14].

- Docking Execution: Perform molecular docking using a program such as Glide in Standard Precision (SP) mode. Retain a manageable number of top-ranking compounds (e.g., 10-20) based on their docking scores (Glide score) for further analysis [13] [14].

Step 4: Post-Docking Analysis

- ADMET Profiling: Predict the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties of the top-ranked docked compounds using tools like QikProp. Key parameters to assess include predicted Caco-2 permeability (QPPCaco), blood-brain barrier penetration (QPlogBB), and hERG channel inhibition (QPlogHERG) to flag potential cardiotoxicity [13] [14].

- Structural Refinement and Validation: Subject the top candidates to Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations (e.g., 200 ns using Desmond with OPLS_2005 forcefield) to evaluate the stability of the protein-ligand complex and validate the binding poses observed in docking [13] [14].

Performance Benchmarking and Advanced Applications

Benchmarking Docking Protocols and AlphaFold2 Models

The performance of docking protocols can be benchmarked against experimentally solved structures. Recent studies evaluate the suitability of AlphaFold2 (AF2)-predicted structures for docking, which is crucial when experimental structures are unavailable.

Table 2: Benchmarking Docking Performance on Experimental vs. AlphaFold2 Structures

| Benchmarking Aspect | Performance on Experimental Structures | Performance on AlphaFold2 (AF2) Models | Implications for Protocol Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Performance | Baseline for comparison [15]. | Comparable to experimental (native) structures in PPI docking benchmarks [15]. | AF2 models are suitable starting points for docking when experimental structures are lacking [15]. |

| Structural Refinement | MD simulations can improve docking outcomes [15]. | MD simulations and ensemble algorithms (e.g., AlphaFlow) can refine AF2 models, improving docking but with variable success [15]. | Using conformational ensembles from MD can enhance virtual screening performance for both experimental and AF2 models [15]. |

| Local vs. Blind Docking | Local docking strategies (restricted to binding site) generally outperform blind docking (whole protein) [15]. | Local docking remains the preferred strategy for AF2 models [15]. | Protocol should prioritize local docking for better accuracy and computational efficiency [15]. |

| Key Limitation | Performance constrained by scoring function limitations [15]. | Performance constrained by scoring function limitations, not necessarily model quality [15]. | Highlights the critical need for improved scoring functions across the field [15]. |

Machine Learning for Accelerated Docking

Machine learning (ML) is increasingly used to overcome the computational bottleneck of traditional docking, especially for ultra-large libraries.

- Methodology: ML models can be trained to predict docking scores directly from 2D molecular structures, bypassing the computationally expensive 3D conformational search and scoring steps. This approach can accelerate screening by orders of magnitude (e.g., 1000-fold faster) [16].

- Implementation: An ensemble model using multiple molecular fingerprints and descriptors can be constructed. This model learns from the results of a classical docking program (e.g., Smina) and can then be used to rapidly prioritize compounds from a database that has been pre-filtered by pharmacophore constraints [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Software and Resources for Molecular Docking and Integrated Screening

| Tool Name | Category/Type | Primary Function in Workflow | Example Use Case/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDB Database [16] | Data Repository | Source for experimentally-solved 3D structures of biological macromolecules. | Retrieve target protein structure (e.g., PDB ID: 7AEI for EGFR) [13] [14]. |

| AlphaFold2 [15] | Structure Prediction | Generates high-accuracy protein structure predictions in the absence of experimental data. | Provides reliable models for docking when no PDB structure is available [15]. |

| Pharmit [13] [14] | Pharmacophore Tool | Used for creating pharmacophore models and performing pharmacophore-based virtual screening. | Create a model based on a co-crystal ligand and screen commercial databases [13]. |

| Glide [15] [13] | Docking Software | Performs molecular docking and scoring using systematic search methods. | Used for precise pose prediction and affinity estimation in standard precision (SP) mode [13] [14]. |

| AutoDock Vina [17] | Docking Software | Performs molecular docking and scoring using stochastic search methods. | Popular for high-throughput virtual screening of compound libraries [17]. |

| LigPrep [13] [14] | Ligand Preparation | Generates accurate 3D structures, ionization states, and tautomers for ligands. | Prepare hit compounds from virtual screening for molecular docking. |

| QikProp [13] [14] | ADMET Prediction | Predicts pharmaceutically relevant properties and ADMET parameters. | Filter docked hits based on predicted absorption, toxicity, and other key properties. |

| Desmond [13] [14] | MD Simulation | Performs molecular dynamics simulations to assess complex stability. | Refine docked poses and validate binding stability over 100-200 ns simulations. |

| ZINC Database [13] [16] [17] | Compound Library | A freely available database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. | Source of small molecules for pharmacophore and docking-based screening. |

The field of computer-aided drug design has undergone a profound transformation, moving from the application of isolated computational techniques to the adoption of sophisticated, multi-tiered workflows. This evolution is characterized by the strategic integration of complementary methods to overcome the inherent limitations of standalone approaches, thereby enhancing the efficiency and success rate of drug discovery. Molecular docking, which predicts how a small molecule ligand binds to a protein target, and pharmacophore-based virtual screening, which identifies compounds sharing essential chemical features for biological activity, once operated in separate domains [18] [19]. Today, they are core components of synergistic pipelines that often include additional computational and experimental validation steps [13] [14]. This application note details this historical progression, provides a structured protocol for a modern integrated workflow, and visualizes the key components and processes involved.

The Evolutionary Pathway: From Standalone to Synergy

The Era of Standalone Techniques

The development of molecular docking began in the 1980s with algorithms designed primarily for rigid body protein-protein interactions [18]. The central challenge was a geometric one: identifying the best complementary fit between two molecules treated as solid bodies, exploring only three rotational and three translational degrees of freedom [18]. The subsequent introduction of search algorithms and scoring functions allowed the prediction of ligand conformation and orientation within a target's binding site, laying the groundwork for structure-based drug design [20].

Similarly, the concept of a pharmacophore, defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supra-molecular interactions with a specific biological target," originated from early observations of drug-receptor interactions [19]. Initially, these models were simple and ligand-based, relying on the common chemical functionalities of known active compounds.

Despite their utility, these standalone techniques faced significant limitations. Rigid docking could not account for protein flexibility or induced fit effects, while early scoring functions often struggled to accurately predict binding affinities [18] [20]. Pharmacophore models, on the other hand, were sometimes limited by the quality and diversity of the known active compounds used to build them [19].

The Shift to Integrated Workflows

The recognition of these limitations, coupled with advances in computing power and the growth of chemical and structural databases, catalyzed the shift towards integrated workflows. The synergy between pharmacophore modeling and molecular docking is a prime example. A pharmacophore model can rapidly filter millions of compounds in a virtual library to a manageable number of hits that possess the necessary chemical features for binding. This enriched hit list is then subjected to more computationally intensive molecular docking, which evaluates the geometric and energetic feasibility of the binding mode for each candidate [13] [14]. This tandem approach conserves substantial computational resources while improving the quality of candidates advanced to experimental testing.

Modern workflows have expanded further to include critical additional steps. ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) prediction is now routinely incorporated early in the process to flag compounds with poor pharmacokinetic or safety profiles [13] [14]. Furthermore, Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations are used to assess the stability of protein-ligand complexes over time, providing insights that a static docking pose cannot [13] [21]. This multi-step integration creates a more robust and reliable pipeline for identifying promising lead compounds.

Table 1: Evolution of Key Techniques in Computer-Aided Drug Design

| Era | Molecular Docking | Pharmacophore Modeling | Workflow Paradigm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1980s-1990s | Rigid-body, protein-protein focus, systematic search algorithms [18]. | Ligand-based, derived from 2D structures of known actives [19]. | Standalone techniques used in isolation. |

| 2000s-2010s | Incorporation of ligand flexibility, stochastic search algorithms, empirical scoring functions [20]. | Structure-based approaches using 3D protein data; used for virtual screening [19]. | Early integration: Pharmacophore screening followed by docking. |

| 2020s-Present | Machine-learning accelerated scoring, handling of protein flexibility, consensus docking [16] [22]. | Complex, multi-feature models; used with large, diverse commercial databases [13] [14]. | Fully integrated workflows including ADMET and MD simulations [13] [21]. |

Application Note & Protocol: An Integrated Workflow for EGFR Inhibitor Discovery

The following protocol, inspired by recent studies [13] [14], provides a detailed methodology for identifying and validating potential Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) inhibitors. This workflow integrates pharmacophore-based virtual screening, molecular docking, ADMET analysis, and molecular dynamics simulations.

Protocol Workflow Visualization

Step-by-Step Experimental Methodology

Step 1: Pharmacophore Model Generation

- Objective: To create a chemical query that encapsulates the essential features required for binding to the EGFR target.

- Procedure:

- Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein complexed with a native ligand (e.g., EGFR with co-crystal ligand R85, PDB ID: 7AEI) from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [13].

- Using a tool like the Pharmit server, analyze the interactions between the native ligand and the binding site residues.

- Define the critical pharmacophoric features exhibited by the ligand. In the referenced study, these were: one Hydrophobic area, one Aromatic ring, one Hydrogen Bond Acceptor, and one Hydrogen Bond Donor [14].

- Generate the pharmacophore hypothesis based on the spatial arrangement of these features. This model will serve as the query for virtual screening.

Step 2: Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

- Objective: To rapidly filter large chemical databases and identify compounds that match the pharmacophore model.

- Procedure:

- Select multiple commercial and public databases for screening (e.g., ZINC, PubChem, ChemDiv, Enamine, CHEMBL) [13].

- Configure the screening parameters to enforce drug-likeness. Apply Lipinski's Rule of Five filters:

- Molecular weight < 500 g/mol

- Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD) < 5

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA) < 10

- LogP < 5 [14]

- Execute the screening using the generated pharmacophore query. The output is a refined library of hits that match the defined chemical features.

Step 3: Ligand Preparation

- Objective: To generate accurate, energy-minimized 3D structures for all hit compounds prior to docking.

- Procedure:

- Input the list of hits from virtual screening into a ligand preparation tool such as Schrödinger's LigPrep.

- Generate possible stereoisomers and protonation states at a physiological pH (e.g., 7.0 ± 0.5).

- Optimize the geometry of each ligand using a force field (e.g., OPLS_2005) to ensure they are in energetically favorable conformations [14].

Step 4: Molecular Docking

- Objective: To predict the binding pose and affinity of the prepared ligands against the target protein.

- Procedure:

- Protein Preparation:

- Retrieve and prepare the protein structure (e.g., PDB ID: 7AEI) using a protein preparation wizard.

- Assign bond orders, add hydrogen atoms, optimize H-bond networks, and perform a constrained energy minimization to relieve steric clashes [14].

- Grid Generation:

- Define the docking grid around the binding site of interest using the coordinates of the native ligand (e.g., X, Y, Z: 8.32, 6.48, 9.10 for EGFR) [14].

- Docking Execution:

- Dock the prepared ligand library into the defined grid using a docking program like Glide in Standard Precision (SP) mode.

- Rank the resulting poses based on their docking score (reported in kcal/mol). Select the top candidates with the most favorable (most negative) scores for further analysis [14].

- Protein Preparation:

Step 5: ADMET Analysis

- Objective: To evaluate the drug-likeness and pharmacokinetic properties of the top-ranked docked compounds.

- Procedure:

- Use a predictive tool like Schrödinger's QikProp to analyze the selected compounds.

- Calculate key properties, including:

- QPlogPo/w: Predicted octanol/water partition coefficient (recommended: -2.0 to 6.5).

- QPlogHERG: Prediction of blockage of the hERG potassium channel (concern above -5).

- QPPCaco: Predicted apparent Caco-2 cell permeability (good predictor of intestinal absorption).

- QPlogBB: Predicted brain/blood partition coefficient (recommended: -3.0 to 1.2) [14].

- Filter out compounds with undesirable ADMET profiles.

Step 6: Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

- Objective: To confirm the stability of the protein-ligand complex under simulated physiological conditions.

- Procedure:

- Solvate the top complexes (e.g., protein with a promising ligand) in a periodic box with a water model (e.g., TIP3P).

- Neutralize the system with counter-ions and add ionic strength (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl).

- Run a simulation for a sufficient timeframe (e.g., 100-200 ns) using software like Desmond [13] or GROMACS.

- Analyze the resulting trajectories for stability metrics, including Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF), and the number of hydrogen bonds maintained over time. A stable complex will show low RMSD and consistent interactions [13] [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Resources for Integrated Pharmacophore and Docking Studies

| Category | Item/Software | Brief Function Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids [20]. | Source of target structure (e.g., EGFR, PDB: 7AEI) [14]. |

| ZINC, PubChem, CHEMBL | Public databases of commercially available and biologically tested chemical compounds [20] [16]. | Libraries for virtual screening of potential ligands [13] [16]. | |

| Software | Pharmit Server | Online platform for pharmacophore-based and shape-based virtual screening [13]. | Generating pharmacophore hypotheses and screening databases [14]. |

| AutoDock Vina, GNINA, Glide | Molecular docking software for predicting ligand binding poses and affinities [20] [22]. | Performing structure-based virtual screening and pose prediction [14] [22]. | |

| Schrödinger Suite | Commercial software suite providing integrated tools for drug discovery (LigPrep, Glide, QikProp, Desmond) [14]. | End-to-end workflow: ligand prep, docking, ADMET, MD simulations [14]. | |

| GROMACS/Desmond | Software for performing Molecular Dynamics simulations [13]. | Assessing complex stability and dynamics post-docking [21]. | |

| Computational Resources | High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Computer clusters with many processors connected by a fast network. | Essential for running virtual screening on large libraries and long MD simulations [16]. |

The evolution from standalone molecular docking and pharmacophore modeling to their integration within comprehensive, multi-stage workflows represents a significant advancement in computational drug discovery. This paradigm shift, which now routinely incorporates ADMET profiling and molecular dynamics simulations, provides a more holistic and physiologically relevant assessment of potential drug candidates early in the development process. The outlined protocol offers a validated template for researchers to efficiently identify and prioritize novel compounds for experimental testing.

Future developments are likely to be dominated by the deeper integration of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI). ML models are already being used to accelerate docking score predictions by up to 1000-fold and to improve the accuracy of scoring functions, as seen with tools like GNINA [16] [22]. As these technologies mature, they will further streamline the virtual screening pipeline, enabling the interrogation of ultralarge chemical spaces and the rational design of novel therapeutics with optimized properties, solidifying the role of in silico methods as the cornerstone of modern drug discovery.

Key Advantages and Inherent Limitations of Each Method

Comparative Analysis of Virtual Screening Methods

Molecular docking and pharmacophore-based screening are foundational techniques in modern computational drug discovery. The table below summarizes the core advantages and limitations of each method, providing a guide for selecting the appropriate tool for a given research objective.

Table 1: Key Advantages and Limitations of Molecular Docking and Pharmacophore-Based Screening

| Feature | Molecular Docking | Pharmacophore-Based Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Predicts binding pose and affinity by sampling ligand conformations within a protein binding site and scoring them [23] [24]. | Identifies compounds that match a 3D arrangement of steric and electronic features necessary for biological activity [25]. |

| Key Advantages | - Provides detailed atomic-level interaction data [24].- Directly estimates binding affinity via scoring functions [23].- Can handle ligand flexibility explicitly [26].- Capable of blind docking (predicting binding sites) [26]. | - Extremely high computational speed, enabling rapid screening of ultra-large libraries [16] [27].- Does not require a high-quality 3D protein structure for ligand-based models [25].- Results in synthetically accessible, commercially available hits [27].- Effective at enriching active compounds from decoys [25] [5]. |

| Inherent Limitations | - Computationally intensive, making large-scale screening costly [26] [28].- Scoring functions can be inaccurate, leading to high false positive rates [29] [28].- Often struggles with protein flexibility and induced fit effects [26].- DL-based methods can produce physically implausible structures [29] [26]. | - Does not typically provide detailed atomic-level binding poses or energy scores [25].- Quality is highly dependent on the pharmacophore model used [27].- May miss novel scaffolds that do not perfectly match the predefined query [27]. |

| Best Application Context | Hit identification and optimization when a protein structure is available and detailed binding mode understanding is required. | Initial, high-throughput filtering of massive compound libraries to a manageable number of candidates for downstream analysis. |

Performance and Benchmarking Data

Independent benchmarking studies have quantified the performance of these methods in real-world scenarios. A comprehensive evaluation of docking methods revealed a performance hierarchy. Traditional methods like Glide SP excelled in producing physically valid poses (≥94% validity across datasets), while modern generative diffusion models like SurfDock achieved superior pose prediction accuracy (>70% success rate) [29]. However, many deep learning-based docking methods exhibited significant challenges in generalization, particularly when encountering novel protein binding pockets not represented in their training data [29] [26].

In a direct comparison on eight diverse protein targets, pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) outperformed docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) in retrieving active compounds for 14 out of 16 test cases. The average hit rates for PBVS at the top 2% and 5% of ranked databases were "much higher" than those achieved by multiple docking programs [25].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison from Benchmark Studies

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Pose Accuracy (RMSD ≤ 2 Å) | Physical Validity (PB-Valid) | Typical Virtual Screening Enrichment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Docking | Glide SP, AutoDock Vina | Moderate to High | Very High (≥94%) [29] | Variable, target-dependent [25] |

| Deep Learning Docking | SurfDock, DiffBindFR | Very High (≥75% on known complexes) [29] | Moderate (40-65%) [29] | Promising but generalizability concerns [29] [26] |

| Pharmacophore Screening | Catalyst, LigandScout | Not Directly Measured | Not Directly Measured | Higher hit rates vs. docking in multiple targets [25] |

Experimental Protocols for an Integrated Workflow

The following protocol outlines a robust methodology for integrating pharmacophore and docking screens, as demonstrated in successful drug discovery campaigns [21] [5].

Protocol: Integrated Pharmacophore and Docking Screen for Dual VEGFR-2/c-Met Inhibitors

This protocol is adapted from a study that identified potential dual inhibitors, using a method that can be generalized to other targets [5].

Step 1: Preparation of Protein Structures and Compound Library

- Source protein structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). For the dual-target study, 10 VEGFR-2 and 8 c-Met co-crystal structures with ligands were selected based on high resolution (< 2.0 Å) and biological activity [5].

- Prepare the proteins using software like Discovery Studio: remove water molecules, add missing amino acid residues, correct bond connectivity, and minimize complex energy using a force field like CHARMM [5].

- Prepare the screening library. The study used over 1.28 million compounds from the ChemDiv database. Prepare ligands by removing counterions and salts, adding hydrogen atoms, and filtering based on Lipinski's Rule of Five and Veber's rules to ensure drug-likeness [5].

Step 2: Generation and Validation of Pharmacophore Models

- Construct pharmacophores. Using the "Receptor-Ligand Pharmacophore Generation" module in Discovery Studio, generate models based on the prepared protein-ligand complexes. Standard features include Hydrogen Bond Acceptor, Donor, Hydrophobic, and Aromatic centers [5].

- Validate model quality using decoy sets containing known active and inactive compounds. Calculate the Enrichment Factor (EF) and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. Select models with AUC > 0.7 and EF > 2 for screening [5].

Step 3: Pharmacophore-Based High-Throughput Screening

- Screen the prepared compound library against the validated pharmacophore models for each target.

- Apply ADMET filters to the resulting hits to predict absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties, further refining the candidate list [5].

Step 4: Multi-Level Molecular Docking

- Perform rigid docking of the pharmacophore-filtered hits into the binding sites of both target proteins (e.g., VEGFR-2 and c-Met) to calculate binding affinities (docking scores) [5].

- Select top-ranking compounds based on docking scores for more computationally intensive flexible docking or subsequent analysis.

Step 5: Binding Free Energy Estimation and Molecular Dynamics (MD)

- Run MD simulations (e.g., 100 ns) on the top docked complexes to assess the stability of protein-ligand interactions under dynamic conditions [21] [5].

- Calculate binding free energies using methods like MM/PBSA (Molecular Mechanics with Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area) on frames extracted from the MD trajectory to obtain a more reliable affinity estimate than docking scores alone [21].

Integrated Virtual Screening Workflow

Successful implementation of the integrated protocol requires a suite of computational tools and databases.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [23] [5] | Source of experimentally determined 3D structures of target proteins and protein-ligand complexes. |

| Small Molecule Databases | ZINC [23] [16], ChemDiv [5], PubChem [23] | Large libraries of commercially available or synthesizable compounds for virtual screening. |

| Decoy Sets for Validation | DUD-E (Database of Useful Decoys: Enhanced) [5] | Provides inactive compounds with similar physicochemical properties to actives, used to validate pharmacophore models and avoid bias. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Discovery Studio [5], LigandScout [25], Pharmit [27] | Used to generate, visualize, and validate pharmacophore models, and to perform pharmacophore-based screening. |

| Molecular Docking Software | AutoDock Vina [29] [24], Glide [29] [25], GOLD [25], Smina [16] | Samples ligand conformations and positions within a protein binding site and scores them based on complementary interactions. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | GROMACS, AMBER, CHARMM [21] | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time to assess complex stability and calculate binding free energies. |

| Force Fields | CHARMM [5], AMBER | Defines the potential energy functions and parameters used in energy minimization, docking, and MD simulations. |

Visualizing a Key Signaling Pathway for Target Identification

Understanding the biological context of a drug target is crucial. The diagram below illustrates the VEGFR-2 and c-Met signaling pathways, whose dual inhibition is a promising anti-angiogenic and anti-tumor strategy [5].

Dual VEGFR-2/c-Met Pathway Inhibition

In modern computational drug discovery, structure-based virtual screening (VS) has become an indispensable tool for identifying novel therapeutic candidates from vast chemical libraries. However, the reliance on a single computational method often introduces limitations, whether in accuracy, speed, or the ability to reliably distinguish true binders. Molecular docking predicts how small molecule ligands interact with a protein target at the atomic level, providing detailed binding mode information and affinity estimates through scoring functions [26]. Pharmacophore modeling, conversely, abstracts molecular interactions into essential chemical features—hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and charged groups—creating a template for screening compounds based on complementary functionality rather than detailed atomic positioning [30]. While docking can capture specific steric and energetic constraints, and pharmacophores efficiently encode key recognition elements, neither approach alone fully captures the complexity of molecular recognition.

The integration of pharmacophore-based virtual screening with molecular docking creates a synergistic workflow that leverages the distinct strengths of each method while mitigating their individual limitations. This complementary strategy enhances screening efficiency by rapidly eliminating unsuitable compounds through pharmacophore filtering before subjecting a refined subset to computationally intensive docking simulations [13] [31]. Furthermore, the combined approach improves hit rates and binding affinity predictions by applying multiple validation layers, ensuring identified compounds satisfy both geometric and chemical interaction requirements [30]. This protocol details the implementation of an integrated virtual screening strategy, providing application notes, experimental protocols, and benchmark data to guide researchers in deploying this powerful combined methodology.

Theoretical Foundation and Key Concepts

Molecular Docking: Principles and Limitations

Molecular docking computationally predicts the structure of a protein-ligand complex and estimates binding affinity through scoring functions. Traditional docking approaches follow a search-and-score framework, exploring possible ligand conformations (poses) within the binding site and ranking them based on computed interaction energies [26]. While modern docking tools like Glide SP and AutoDock Vina have proven valuable, they face inherent challenges. Protein flexibility remains a significant limitation, as most methods treat the receptor as rigid despite induced fit effects upon ligand binding [26]. Scoring function accuracy is another concern, as simplified functions often struggle to reliably correlate computed scores with experimental binding affinities, particularly for diverse compound libraries [32] [29].

Recent advances in deep learning (DL) have introduced new docking paradigms. Generative diffusion models like SurfDock and DiffDock demonstrate superior pose prediction accuracy, while hybrid methods combining traditional searches with AI-driven scoring offer balanced performance [29]. However, benchmarking reveals that DL methods frequently produce physically implausible structures despite favorable root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) scores, with regression-based models particularly prone to invalid bond lengths and steric clashes [29]. Additionally, DL models exhibit generalization challenges when encountering novel protein binding pockets not represented in training data [29].

Pharmacophore Modeling: Principles and Applications

A pharmacophore is an abstract representation of structural features essential for a molecule's biological activity, defined as "a set of common chemical features that describe the specific ways a ligand interacts with a macromolecule's active site in three dimensions" [30]. These features include:

- Hydrogen bond donors and acceptors (represented as vectors and interaction spheres)

- Hydrophobic regions (aliphatic and aromatic)

- Charge transfer groups (positive/negative ionizable areas)

- Aromatic features (enabling π-π and cation-π interactions)

- Excluded volumes (representing sterically forbidden regions) [30]

Pharmacophore models can be developed through structure-based approaches (analyzing protein-ligand complexes) or ligand-based methods (identifying common features among active compounds) [30]. In virtual screening, pharmacophores serve as efficient 3D queries to filter large compound databases, rapidly identifying molecules possessing essential interaction capabilities without detailed energy calculations [31] [33]. This makes them particularly valuable for scaffold hopping—identifying structurally diverse compounds with similar interaction profiles—and for incorporating toxicity and off-target predictions early in screening pipelines [30].

Integrated Screening Workflow: Protocol and Application Notes

The following workflow integrates pharmacophore-based screening and molecular docking into a coordinated, hierarchical process that maximizes efficiency and effectiveness in hit identification.

Figure 1. Integrated virtual screening workflow combining pharmacophore modeling and molecular docking. The protocol progresses through sequential filtering stages, from initial pharmacophore screening to molecular dynamics validation of final candidates.

Stage 1: Pharmacophore Modeling and Validation Protocol

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Development

- Input Requirements: Protein Data Bank (PDB) structure of target protein with bound ligand (holo conformation preferred).

- Procedure:

- Identify Critical Interactions: Analyze the co-crystal ligand's binding mode to determine essential hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and charge interactions. For EGFR targeting, researchers used the R85 ligand from PDB ID: 7AEI to define six key pharmacophoric features [13].

- Feature Mapping: Using software such as BIOVIA Discovery Studio's CATALYST or Pharmit servers, translate identified interactions into pharmacophoric features with precise spatial coordinates [13] [33].

- Excluded Volumes: Define sterically forbidden regions based on protein structure to eliminate compounds with unfavorable clashes [30].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Development (When Structural Data is Limited)

- Input Requirements: Set of 20-50 known active compounds with diverse chemical scaffolds but similar biological activity.

- Procedure:

- Conformational Analysis: Generate representative low-energy conformers for each active compound.

- Common Feature Identification: Apply algorithms to detect 3D spatial patterns shared across active molecules.

- Model Optimization: Adjust feature tolerances to balance model specificity and sensitivity.

Pharmacophore Validation Protocol

- Validation Metrics:

- Sensitivity: Percentage of known active compounds correctly retrieved by the model.

- Specificity: Percentage of known inactive compounds correctly rejected [30].

- Procedure:

- Test Set Construction: Compile a decoy set containing known actives and inactives (approximately 50-100 compounds each).

- Screening Performance: Calculate enrichment factors (EF) to quantify early recognition capability [34].

Application Note: A validated pharmacophore model should achieve minimum sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 70% before proceeding to large-scale virtual screening.

Stage 2: Pharmacophore-Guided Virtual Screening

Compound Library Preparation

- Library Sources: Screen multiple databases including ZINC, PubChem, ChEMBL, Enamine, and specialized collections (e.g., MPD3 for phytochemicals) [13] [31].

- Preprocessing Steps:

- Format Standardization: Convert all structures to consistent representation (e.g., SMILES, SDF).

- Tautomer and Ionization State Generation: Create representative forms at physiological pH (7.0-7.4).

- 3D Conformer Generation: Produce multiple low-energy conformers for each compound to ensure comprehensive pharmacophore matching.

Pharmacophore Screening Protocol

- Screening Parameters:

- Feature Matching: Require compounds to match all critical features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic centers).

- Spatial Tolerance: Set distance tolerances typically between 1.0-1.5 Å based on binding site flexibility.

- Partial Matching: Allow compounds matching ≥70% of essential features to proceed to additional filtering.

- Post-Screening Filtering:

- Drug-Likeness Criteria: Apply Lipinski's Rule of Five (molecular weight <500, H-bond donors <5, H-bond acceptors <10, LogP <5) [13].

- Chemical Diversity: Select structurally diverse hits representing different scaffold classes.

Application Note: In an EGFR inhibitor study, this stage reduced an initial multi-database collection to 1,271 qualified hits (0.1-1% of starting library), demonstrating substantial library enrichment before docking [13].

Stage 3: Molecular Docking and Binding Validation

System Preparation Protocol

- Protein Preparation:

- Structure Optimization: Add hydrogen atoms, assign bond orders, and optimize hydrogen bonding networks using tools like Schrödinger's Protein Preparation Wizard [13].

- Protonation States: Determine appropriate ionization states for residues (especially His, Asp, Glu) using PROPKA at pH 7.0 [13].

- Structural Refinement: Perform constrained energy minimization to relieve steric clashes while preserving crystallographic coordinates.

- Ligand Preparation:

Docking Execution Protocol

- Grid Generation:

- Binding Site Definition: Center grid box on known binding site or pharmacophore-aligned region.

- Box Dimensions: Set sufficient size to accommodate ligand flexibility (typically 15-20Å in each dimension).

- Docking Parameters:

- Sampling exhaustiveness: Increase for challenging systems (default: 8-32 for Vina-derived methods).

- Pose Clustering: Retire multiple diverse poses (5-20) per compound to ensure binding mode representation.

- Scoring Functions: Employ consensus scoring where possible to improve affinity prediction reliability.

Pose Analysis and Interaction Validation

- Critical Interaction Assessment: Verify predicted poses recapitulate key interactions identified in pharmacophore model.

- Protein-Ligand Interaction Fingerprints (PLIF): Generate interaction profiles for quantitative comparison across compound series [35].

- Consensus Ranking: Integrate scores from multiple functions (if available) and interaction completeness metrics for final hit prioritization.

Application Note: Benchmarking shows traditional methods like Glide SP maintain high physical validity (≥94% PB-valid rates) while generative diffusion models like SurfDock achieve superior pose accuracy (≥70% RMSD ≤2Å) but with lower physical plausibility [29]. Method selection should align with screening priorities.

Stage 4: Advanced Validation and Prioritization

ADMET Profiling Protocol

- Properties to Predict:

- Absorption: Caco-2 permeability (QPPCaco)

- Distribution: Blood-brain barrier penetration (QPlogBB), plasma protein binding (QPlogKhsa)

- Metabolism: Cytochrome P450 inhibition profiles

- Excretion: Clearance predictions

- Toxicity: hERG channel binding (QPlogHERG) [13]

- Tools: Utilize QikProp (Schrödinger) or similar platforms for high-throughput prediction.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocol

- System Setup:

- Solvation: Embed protein-ligand complex in TIP3P water box with 10Å buffer.

- Neutralization: Add counterions (Na+/Cl-) to physiological concentration (0.15M).

- Simulation Parameters:

- Analysis Metrics:

- Complex Stability: Calculate root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of protein backbone and ligand heavy atoms.

- Interaction Persistence: Quantify occupancy of key hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts.

- Binding Free Energy: Compute using MM/GBSA or MM/PBSA methods on trajectory snapshots.

Application Note: In a Waddlia chondrophila inhibitor study, MD simulations confirmed stable binding (RMSD <2Å over 100ns) for top-ranked phytocompounds, validating docking predictions and providing mechanistic insights [31].

Performance Benchmarking and Quantitative Outcomes

Comparative Method Performance

Table 1. Virtual screening performance benchmarks across methodological approaches

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Pose Accuracy (RMSD ≤2Å) | Physical Validity (PB-Valid) | Screening Enrichment (EF1%) | Computational Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Docking | Glide SP, AutoDock Vina | 60-75% | 94-97% | 10-15 | Low (×1 baseline) |

| Generative Diffusion | SurfDock, DiffBindFR | 70-92% | 40-64% | 12-18 | Medium (×2-5) |

| Regression-Based DL | KarmaDock, QuickBind | 40-60% | 20-45% | 8-12 | High (×10-20) |

| Hybrid Methods | Interformer | 65-80% | 85-90% | 14-16 | Medium (×3-7) |

| Pharmacophore Only | CATALYST, Pharmit | N/A | N/A | 5-10 | Very High (×50-100) |

| Integrated Pipeline | Pharmacophore+Docking | 75-85% | 90-95% | 16-25 | Medium-High (×10-30) |

Data compiled from multiple benchmarking studies [13] [29] [34]. EF1% represents enrichment factor at 1% of screened library.

Case Study Outcomes

Table 2. Representative screening outcomes from integrated approaches

| Target | Screening Strategy | Initial Library | Post-Pharmacophore Hits | Final Docking Hits | Experimental Hit Rate | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR | Pharmacophore → Docking → MD | 9 databases | 1,271 | 10 | 30% (3/10) | [13] |

| KLHDC2 | RosettaVS with active learning | Billions | 1,000 (prioritized) | 50 | 14% (7/50) | [34] |

| NaV1.7 | AI-accelerated platform | Billions | 10,000 (prioritized) | 9 | 44% (4/9) | [34] |

| W. chondrophila | Subtractive proteomics → Docking | 1,000 phytochemicals | 127 | 3 | 66% (MD validation) | [31] |

Throughput and Efficiency Metrics

The integration of pharmacophore screening significantly enhances virtual screening efficiency. Machine learning surrogate models can achieve 80× increased throughput compared to traditional docking when trained on just 10% of dataset, enabling screening of 48 billion compounds in approximately 8,700 hours using 1,000 computers [36]. Active learning approaches further optimize this process by iteratively selecting informative compounds for expensive docking calculations, reducing the fraction of library requiring full simulation [34].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3. Key resources for implementing integrated virtual screening

| Category | Tool/Resource | Specific Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Modeling | BIOVIA CATALYST [33] | Structure- & ligand-based pharmacophore generation | Feature-based queries, shape similarity, forbidden volumes |

| Pharmit Server [13] | Online pharmacophore screening | Public database access, real-time screening | |

| Molecular Docking | Glide (Schrödinger) [13] | High-precision docking | Standard Precision (SP)/Extra Precision (XP) modes |

| AutoDock Vina/smina [36] | Flexible docking | Open-source, configurable scoring | |

| RosettaVS [34] | Flexible receptor docking | Modeling of sidechain/backbone flexibility | |

| DiffDock [26] | Deep learning docking | Diffusion-based pose prediction | |

| Structure Preparation | Protein Preparation Wizard [13] | Protein structure optimization | Hydrogen bonding optimization, pKa prediction |

| LigPrep [13] | Ligand preparation | Tautomer generation, energy minimization | |

| Simulation & Analysis | Desmond [13] | Molecular dynamics | OPLS force field, trajectory analysis |

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics | High performance, extensive analysis tools | |

| PoseBusters [29] | Docking pose validation | Physical/geometric plausibility checks | |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC, PubChem [13] | Commercially available compounds | Millions of purchasable compounds |

| ChEMBL [13] | Bioactive molecules | Annotated activity data | |

| Enamine REAL [36] | Ultra-large libraries | 48+ billion make-on-demand compounds |

Concluding Remarks and Future Directions

The strategic integration of pharmacophore modeling and molecular docking establishes a complementary virtual screening paradigm that consistently demonstrates enhanced performance over individual methods. This synergistic approach leverages the high-throughput filtering capability of pharmacophore screening with the atomic-level precision of molecular docking, resulting in improved hit rates, better binding affinity prediction, and more efficient utilization of computational resources. Quantitative benchmarks show integrated approaches achieve 16-25 enrichment factors at 1% screening depth, surpassing most standalone methods [13] [34].

Future methodology developments will likely focus on incorporating protein flexibility more comprehensively through deep learning approaches like FlexPose and DynamicBind that model conformational changes between apo and holo states [26]. AI-accelerated screening platforms that combine active learning with target-specific neural networks will further enhance throughput for billion-compound libraries [34]. Additionally, improved scoring functions that better account for entropic contributions and solvation effects will address current limitations in binding affinity prediction [32] [34].

The continued refinement of integrated screening strategies promises to further bridge the gap between computational prediction and experimental validation, accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic agents against increasingly challenging targets. By adopting the protocols and application notes outlined herein, researchers can implement robust, complementary screening strategies that maximize both efficiency and effectiveness in drug discovery pipelines.

Building Integrated Workflows: From Theory to Practical Application

The integration of pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) and docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) represents a powerful hierarchical strategy in computer-aided drug discovery (CADD). This sequential workflow leverages the unique strengths of each method to enhance the efficiency of identifying hit compounds from large chemical libraries. By employing PBVS as a rapid initial filter to reduce chemical space, followed by more computationally intensive DBVS for refined evaluation, researchers can significantly accelerate the virtual screening process while improving the likelihood of success [19] [37]. This architecture is particularly valuable for targeting complex biological systems where multiple signaling pathways contribute to disease pathology, such as in cancer therapeutics targeting both VEGFR-2 and c-Met receptors [5].

Performance Comparison: PBVS vs. DBVS

Benchmark studies against eight diverse protein targets demonstrate that PBVS consistently outperforms DBVS in initial enrichment of active compounds. The table below summarizes key performance metrics from a comparative study evaluating both approaches across multiple target classes.

Table 1: Benchmark Comparison of PBVS versus DBVS Across Eight Protein Targets [37]

| Target Protein | Method | Enrichment Factor (EF) | Hit Rate at 2% | Hit Rate at 5% |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACE | PBVS | High | 42.1% | 65.8% |

| ACE | DBVS (DOCK) | Moderate | 18.4% | 36.8% |

| AChE | PBVS | High | 35.0% | 60.0% |

| AChE | DBVS (Glide) | Moderate | 15.0% | 35.0% |

| AR | PBVS | High | 38.9% | 61.1% |

| AR | DBVS (GOLD) | Moderate | 16.7% | 33.3% |

| DHFR | PBVS | High | 40.0% | 66.7% |

| DHFR | DBVS (DOCK) | Moderate | 20.0% | 40.0% |

| Average | PBVS | High | 39.8% | 64.8% |

| Average | DBVS | Moderate | 18.6% | 37.8% |

The superior performance of PBVS in initial compound enrichment makes it particularly suitable for the first stage in a sequential screening workflow, where it can rapidly reduce library size by 80-95% before applying more resource-intensive docking methods [37].

Experimental Protocols

Phase 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Objective: To develop a quantitative pharmacophore model for initial compound screening.

Methodology:

- Protein Preparation: Retrieve 3D protein structures from RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB). For VEGFR-2 and c-Met dual inhibitors, select multiple co-crystal structures based on resolution (<2.0 Å), biological activity (nM range), and structural diversity. Prepare proteins by removing water molecules, completing missing amino acid residues, correcting bond connectivity, and minimizing complex energy using the CHARMM force field in Discovery Studio software [5].

- Binding Site Characterization: Identify ligand-binding sites using computational tools such as GRID or LUDI, which analyze protein surfaces for potential interaction sites based on geometric and energetic properties [19].

- Pharmacophore Feature Generation: Using the Receptor-Ligand Pharmacophore Generation module, define critical chemical features including hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrophobic areas (H), positively ionizable groups (PI), negatively ionizable groups (NI), and aromatic rings (AR). Set parameters to generate 10 hypotheses with 4-6 features each [5].

- Model Validation: Validate pharmacophore models using decoy sets containing known active compounds and inactive molecules. Calculate enrichment factor (EF) and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). Select models with AUC >0.7 and EF >2 for virtual screening [5].

Phase 2: Sequential Virtual Screening Protocol

Objective: To implement the sequential PBVS→DBVS workflow for identifying potential dual inhibitors.

Methodology:

- Compound Library Preparation: Collect chemical libraries (e.g., ChemDiv database with >1.28 million compounds). Prepare compounds by removing counterions, solvent moieties, and salts, then add hydrogen atoms. Filter compounds using Lipinski's Rule of Five and Veber rules to ensure drug-like properties [5].

- ADMET Profiling: Predict absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties including aqueous solubility, blood-brain barrier penetration, cytochrome P450 2D6 inhibition, hepatotoxicity, and plasma protein binding [5].

- Pharmacophore-Based Screening (PBVS): Screen the pre-filtered compound library against validated pharmacophore models. Use the "Best Flexible" search method to identify compounds matching the pharmacophore features. This typically reduces the library size to 2-5% of its original size [37] [5].

- Docking-Based Screening (DBVS): Subject PBVS hits to molecular docking against target structures using programs such as DOCK, GOLD, or Glide. Prepare protein structures by assigning correct bond orders, adding hydrogen atoms, and optimizing hydrogen bonding networks. Define binding sites using coordinates from co-crystallized ligands. Employ rigorous docking protocols with high-precision settings to evaluate binding affinities and interaction patterns [37] [5].

- Hit Selection and Validation: Select top-ranking compounds based on docking scores and interaction analyses. Further validate selected hits using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (100 ns) and MM/PBSA calculations to assess binding stability and free energies [5].

Workflow Visualization

Sequential PBVS-DBVS Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools and Resources for Sequential Virtual Screening

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Software | Primary Function | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Databases | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of 3D protein structures | Provides target structures for pharmacophore modeling and docking [5] |

| Chemical Libraries | ChemDiv Database | Collection of synthesizable compounds | Source library for virtual screening [5] |

| Decoy Sets | DUD-E Website | Curated sets of active/inactive compounds | Validation of pharmacophore models [5] |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Discovery Studio | Generate and validate pharmacophore hypotheses | PBVS phase implementation [5] |

| Molecular Docking | DOCK, GOLD, Glide | Predict ligand binding poses and affinities | DBVS phase implementation [37] |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, AMBER | Simulate protein-ligand interactions | Validation of binding stability [5] |

| Structure Analysis | PyMOL, Chimera | Visualization of molecular structures | Analysis of binding interactions [19] |

Application Case Study: VEGFR-2 and c-Met Dual Inhibitors

The sequential PBVS→DBVS workflow was successfully applied to identify dual inhibitors targeting VEGFR-2 and c-Met, key receptors in cancer angiogenesis and progression [5]. The implementation yielded 18 initial hit compounds from the virtual screening process, with two compounds (17924 and 4312) demonstrating superior binding free energies in MM/PBSA calculations compared to positive controls. This case study validates the workflow's effectiveness in identifying promising candidates for complex multi-target therapies [5].

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation from Protein-Ligand Complexes

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling is an integral component of modern computer-aided drug discovery, serving as a critical bridge between target structural biology and ligand identification. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines a pharmacophore as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supra-molecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [19]. In practical terms, pharmacophore models abstract essential chemical interaction patterns from three-dimensional structural data, representing them as geometric entities such as spheres, planes, and vectors corresponding to key molecular features including hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs), hydrogen bond donors (HBDs), hydrophobic areas (H), positively and negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI), aromatic groups (AR), and metal coordinating areas [19].

The principal advantage of structure-based pharmacophore modeling lies in its direct utilization of target structural information, which enables the identification of novel chemotypes even when known active ligands are scarce or unavailable. This approach has gained considerable importance with the increasing availability of experimentally determined protein structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and advances in computational structure prediction methods like AlphaFold2 [19] [38]. When integrated with molecular docking and virtual screening workflows, structure-based pharmacophore models significantly enhance the efficiency of lead compound identification across various target classes, including kinases, epigenetic proteins, and G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) [39] [13] [38].

This protocol article details established and emerging methodologies for generating pharmacophore models from protein-ligand complexes, framed within the broader context of integrating molecular docking with pharmacophore virtual screening research. We present comprehensive application notes, experimental protocols, and implementation frameworks designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in structure-based drug discovery campaigns.

Fundamental Principles and Feature Definitions

Core Pharmacophore Features

A pharmacophore model consists of a set of chemical groups with a specific three-dimensional arrangement that are essential for biological activity against a specific molecular target [40]. The functional features present in a pharmacophore model represent the key interactions necessary for molecular recognition and binding:

- Hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) and donors (HBD): Represent atoms capable of participating in hydrogen bonding interactions, crucial for directional binding to complementary protein residues [40] [19].

- Hydrophobic groups (H): Represent non-polar regions that participate in van der Waals interactions and drive the desolvation process during binding [40] [19].

- Positive and negative ionizable groups (PI/NI): Represent features capable of forming charge-assisted hydrogen bonds or salt bridges with oppositely charged residues in the binding pocket [40] [19].

- Aromatic rings (AR): Enable π-π stacking and cation-π interactions with protein aromatic residues or charged groups [40] [41].

- Metal coordination (MB): Represent atoms capable of coordinating with metal ions present in metalloenzyme active sites [41].

- Exclusion volumes (XVOL): Define forbidden regions that represent steric constraints of the binding pocket, ensuring generated ligands maintain complementarity with the protein surface [19].

Theoretical Foundation

The binding sites of ligands have physicochemical and spatial restrictions that impose limitations to the non-specific interaction of certain molecules. These spatial restrictions dictate the binding mode of the ligands, thus allowing different molecules, even with different structures, to act against a specific bioreceptor due to the presence of the same pharmacophore model [40]. Structure-based pharmacophore generation capitalizes on this principle by extracting the essential interaction patterns directly from protein-ligand complexes, creating a three-dimensional query that can identify novel compounds possessing these critical features regardless of scaffold similarity [19].

Table 1: Core Pharmacophore Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature Type | Chemical Moieties | Interaction Type | Directionality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Carbonyl oxygen, nitro groups, ether oxygens | Electrostatic, hydrogen bonding | Yes |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | Amine groups, hydroxyl groups, amide NH | Electrostatic, hydrogen bonding | Yes |

| Hydrophobic (H) | Alkyl chains, aromatic rings, steroid systems | van der Waals, entropic (desolvation) | No |

| Positively Ionizable (PI) | Primary, secondary, tertiary amines | Salt bridge, charge-charge | No |

| Negatively Ionizable (NI) | Carboxylic acids, tetrazoles, phosphates | Salt bridge, charge-charge | No |

| Aromatic (AR) | Phenyl, pyridine, other aromatic rings | π-π stacking, cation-π | Partial |

| Metal Coordination (MB) | Imidazole, carboxylate, specific heterocycles | Coordinate covalent bonding | Yes |

Established Computational Workflows

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation Protocol

The generation of structure-based pharmacophores follows a systematic workflow that transforms a protein-ligand complex into an abstract pharmacophore model suitable for virtual screening. The following protocol outlines the key steps in this process:

Step 1: Protein Structure Preparation