Structure-Based vs Ligand-Based Drug Design in Oncology: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of structure-based and ligand-based drug design methodologies, focusing on their applications, challenges, and synergistic potential in oncology.

Structure-Based vs Ligand-Based Drug Design in Oncology: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of structure-based and ligand-based drug design methodologies, focusing on their applications, challenges, and synergistic potential in oncology. It explores the foundational principles of both approaches, detailing key techniques like molecular docking, pharmacophore modeling, and AI-driven methods. The content addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies, supported by case studies including PARP1 and βIII-tubulin inhibitors. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it synthesizes current trends and validates methods through comparative analysis, offering insights into future directions for targeted cancer therapy development.

Core Principles and Data Requirements in Oncology Drug Design

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) is a foundational pillar in modern computational drug discovery, distinguished by its direct use of the three-dimensional (3D) structure of a biological target to guide the design and optimization of small-molecule therapeutics [1] [2]. This approach is particularly powerful in oncology research, where understanding precise ligand-protein interactions can lead to more effective and targeted cancer therapies [3] [4]. This guide provides an objective comparison of SBDD with Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD), detailing methodologies, experimental protocols, and key resources.

Core Principles and Workflow of SBDD

SBDD operates on the principle of "structure-centric" design. The process initiates with the 3D structure of a target protein, often involved in disease progression, with the goal of designing a novel molecule or optimizing an existing one to fit its binding site with high affinity and specificity [1] [2] [5]. The standard SBDD workflow is an iterative cycle consisting of several key stages.

Table: Key Stages in a Standard SBDD Workflow

| Stage | Description | Key Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Target Identification & Validation | Identifying a therapeutically relevant protein target (e.g., an enzyme critical for cancer cell survival) and validating its role in the disease. | Genomic, proteomic studies, and functional assays [1] [3]. |

| Structure Determination | Obtaining the high-resolution 3D structure of the target protein. | X-ray crystallography, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) [1] [2]. |

| Binding Site Analysis | Identifying and characterizing the cavity on the protein where a ligand can bind. | Computational tools like Q-SiteFinder that use energy-based probes [1]. |

| Molecular Design & Docking | Designing new molecules or screening virtual libraries to find hits that complement the binding site. | De novo design, virtual screening, molecular docking [1] [6] [5]. |

| Scoring & Affinity Estimation | Ranking the designed or docked molecules based on their predicted binding affinity. | Docking scores (e.g., Vina score), machine learning-based scoring functions (e.g., DrugCLIP) [6]. |

| Lead Optimization | Refining the top candidate molecules to improve properties like potency, selectivity, and drug-likeness. | Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, free-energy perturbation (FEP) calculations [1] [3] [5]. |

| Experimental Validation | Synthesizing the lead compounds and testing their biological activity and binding in the lab. | In vitro biochemical assays, in vivo testing [1] [3]. |

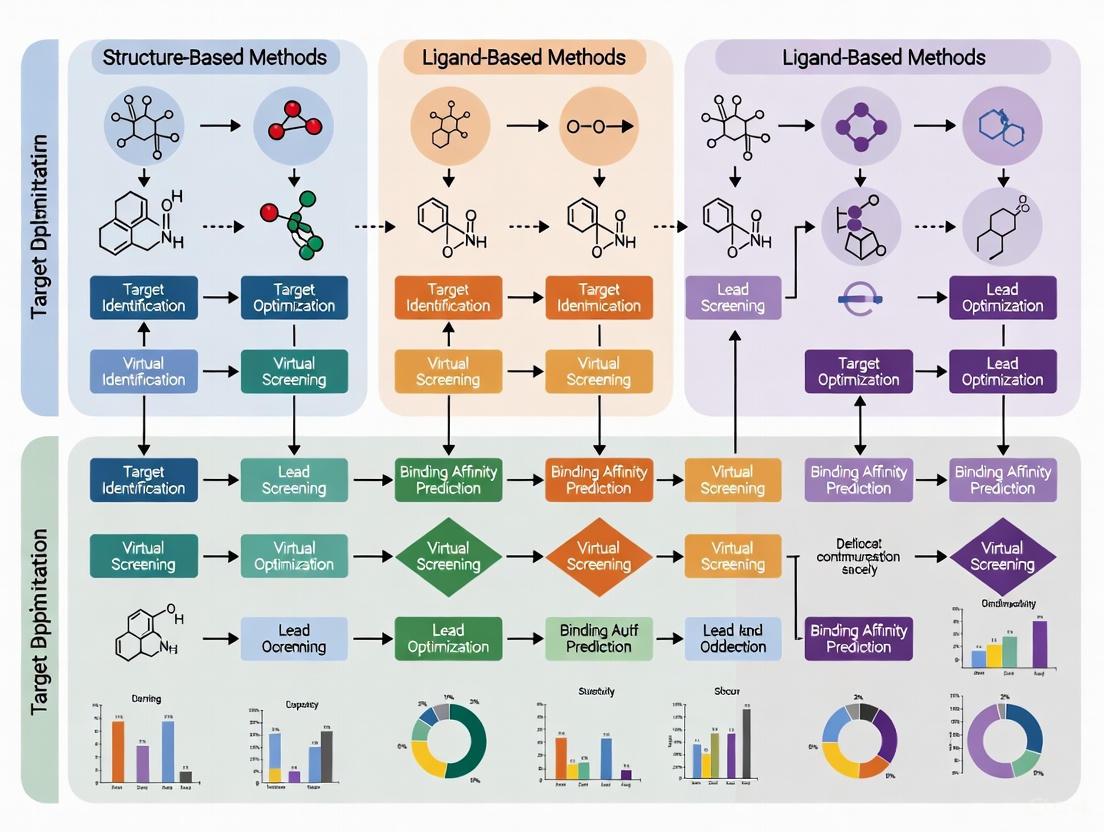

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and iterative nature of this SBDD workflow.

SBDD vs. LBDD: An Objective Comparison for Oncology Research

While SBDD relies on the target's structure, Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD) uses information from known active molecules (ligands) to predict new active compounds, operating under the principle that structurally similar molecules have similar biological activities [2] [5]. The choice between them depends heavily on the available data and the research context.

Table: Comparison of SBDD vs. LBDD in an Oncology Context

| Feature | Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) | Ligand-Based Drug Design (LBDD) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Direct 3D structure of the target protein guides design [2]. | Known active ligands and their properties guide design [2]. |

| Data Requirement | High-resolution protein structure (from X-ray, Cryo-EM, or prediction) [1] [2]. | A set of known active (and sometimes inactive) compounds for the target [5]. |

| Primary Application | De novo drug design, lead optimization, understanding binding interactions [1] [7]. | Hit identification, scaffold hopping, when target structure is unknown [5]. |

| Key Strengths | • Rational design of novel scaffolds.• Provides atomic-level insight into binding mechanics.• Can optimize for affinity and specificity directly [2] [5]. | • Fast and scalable for virtual screening.• Does not require target structure.• Excellent for finding chemically similar actives [5]. |

| Key Limitations | • Dependent on availability/accuracy of protein structure.• Computationally intensive for large libraries.• Scoring functions can be imperfect and prone to overfitting [6] [2] [5]. | • Cannot design truly novel scaffolds outside known chemical space.• Relies on quality/quantity of known actives.• Provides no direct information on binding mode [3] [5]. |

| Representative Techniques | Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamics (MD), Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) [1] [5]. | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR), Pharmacophore Modeling, 2D/3D Similarity Search [2] [5]. |

Experimental Protocols in SBDD

For researchers, the practical application of SBDD involves several well-established computational protocols. Below are detailed methodologies for two critical experiments.

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS) via Molecular Docking

This protocol is used to computationally screen millions of compounds from virtual libraries to identify potential hits [1] [5].

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein from the PDB (Protein Data Bank). Remove native ligands and water molecules (unless critical for binding). Add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and correct for missing residues or atoms using modeling software [1].

- Binding Site Definition: Define the spatial coordinates of the binding pocket. This can be the known active site from a co-crystallized structure or predicted using a tool like Q-SiteFinder, which identifies energetically favorable probe clusters [1].

- Ligand Library Preparation: Prepare a database of small molecules in a suitable format (e.g., SDF, MOL2). Generate plausible 3D conformations for each compound and minimize their energy [5].

- Molecular Docking: Use docking software (e.g., AutoDock Vina) to perform flexible ligand docking into the defined binding site. The algorithm will search for the optimal orientation and conformation (pose) of each ligand [6] [5].

- Scoring and Ranking: The docking software scores each pose using a scoring function that approximates the binding affinity. Compounds are ranked based on their best docking score [6] [5].

- Post-Docking Analysis: Visually inspect the top-ranked poses to analyze key protein-ligand interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts). Select a diverse subset of high-ranking compounds for experimental testing [5].

Protocol 2: Binding Affinity Refinement using Molecular Dynamics (MD)

MD simulations are used to validate docking results and more accurately assess binding stability and free energy [1] [3].

- System Setup: Place the docked protein-ligand complex in a simulation box filled with water molecules (e.g., TIP3P water model). Add ions (e.g., Na+, Cl-) to neutralize the system's charge and mimic physiological ionic strength.

- Energy Minimization: Run a minimization algorithm (e.g., steepest descent) to remove any steric clashes or unrealistic geometry in the initial system, relaxing the structure to a local energy minimum.

- Equilibration: Perform two phases of equilibration under periodic boundary conditions:

- NVT Ensemble: Hold the Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature constant to stabilize the system temperature (e.g., 310 K).

- NPT Ensemble: Hold the Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature constant to stabilize the system density and pressure (e.g., 1 bar).

- Production Run: Execute a long, unrestrained MD simulation (typically tens to hundreds of nanoseconds). The trajectory of atomic coordinates is saved at regular intervals for analysis.

- Trajectory Analysis: Analyze the saved trajectory to calculate:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the stability of the protein-ligand complex.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Identifies flexible regions of the protein.

- Interaction Analysis: Profiles specific interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) over time.

- Binding Free Energy Calculation: Use advanced methods like Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) or Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) on simulation snapshots to compute a more rigorous estimate of the binding free energy than the docking score [3] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful execution of SBDD relies on a suite of computational tools and data resources.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for SBDD

| Item Name | Function in SBDD | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Data Repository | A central, public repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids, providing the initial target structures [1] [8]. |

| AutoDock Vina | Docking Software | A widely used program for molecular docking and virtual screening, providing a scoring function to rank ligand poses [6]. |

| GROMACS | Simulation Software | A high-performance MD simulation package used to simulate the physical movements of atoms and molecules in the protein-ligand complex over time [8]. |

| Proasis Platform | Integrated Data System | An enterprise solution that integrates and manages 3D structural data, binding affinity data, and other SBDD-critical information, transforming raw data into a strategic asset [8]. |

| CrossDocked Dataset | Benchmarking Data | A curated dataset of protein-ligand complexes commonly used to train and benchmark machine learning models for SBDD [6] [7]. |

| SE(3)-Equivariant GNN | AI Model Architecture | A type of graph neural network that respects the geometric symmetries of 3D space (rotation, translation), making it powerful for generating 3D molecular structures [7]. |

In the direct comparison between SBDD and LBDD, SBDD offers an unmatched, rational approach for designing novel therapeutics when a target structure is available, making it indispensable for precision oncology. However, the field is evolving beyond this dichotomy. The most powerful modern approaches integrate SBDD and LBDD [5]. For example, LBDD can rapidly pre-screen vast chemical libraries, and SBDD can then be applied to the top hits for detailed interaction analysis and optimization [5].

Furthermore, the advent of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is profoundly transforming SBDD. Deep generative models like DiffSBDD can create novel, drug-like molecules directly conditioned on protein pockets [7]. These AI models are also being used to develop more reliable scoring functions than traditional empirical scores, helping to bridge the gap between theoretical predictions and real-world applicability [6]. As these technologies mature, combined with the strategic treatment of data as a core product, the target-centric approach of SBDD is poised to drive the next wave of innovation in cancer drug discovery [3] [8].

Ligand-based drug design (LBDD) is a foundational approach in computer-aided drug discovery applied when the three-dimensional structure of the biological target is unknown or unavailable [9] [10]. Instead of directly targeting protein structures, LBDD relies on the chemical information from known active molecules to guide the design and optimization of new drug candidates [11]. The core hypothesis underpinning this methodology is that similar molecules exhibit similar biological activities, allowing researchers to establish a correlation between chemical structure and pharmacological effect through Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) studies [9] [10]. This approach is particularly valuable in oncology research, where rapid identification of novel therapeutic agents is critical, and structural information for novel targets may be lacking initially.

LBDD encompasses several computational techniques, including pharmacophore modeling, quantitative structure-activity relationships (QSAR), and molecular similarity analysis [11]. These methods enable researchers to explore chemical space, predict drug properties, and virtually screen large compound libraries to identify molecules with desired biological activity. By leveraging existing knowledge of active compounds, LBDD significantly accelerates the early stages of drug discovery, from initial hit identification to lead optimization, making it an indispensable tool in the development of oncology therapeutics [10] [11].

Core Methodologies in LBDD

Pharmacophore Modeling

Pharmacophore modeling identifies the essential structural features and their spatial arrangements responsible for a molecule's biological activity [11]. These features typically include hydrogen bond donors, hydrogen bond acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and charged groups that collectively define the molecular interaction capabilities with the target.

- Ligand-based pharmacophore models are derived from aligning multiple known active compounds to identify common chemical features, while structure-based models are generated from analysis of ligand-target interactions in available crystal structures [11].

- Automated generation algorithms like HipHop and HypoGen align compounds and extract pharmacophoric features based on predefined rules and scoring functions, with consensus approaches combining multiple models to improve robustness [11].

- In virtual screening, these 3D pharmacophore models serve as queries to identify potential hits from large compound libraries, often combined with other filters like physicochemical properties or ADME criteria to prioritize experimental testing [11].

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR)

QSAR modeling establishes mathematical relationships between structural descriptors and biological activity through a defined development process [10] [11]:

- Data Collection: Curating ligands with experimentally measured biological activities

- Descriptor Calculation: Generating molecular descriptors representing structural and physicochemical properties

- Feature Selection: Identifying the most relevant descriptors correlating with activity

- Model Building: Applying statistical or machine learning methods to establish mathematical relationships

- Validation: Rigorously testing statistical stability and predictive power

The methodology includes both 2D QSAR approaches that utilize 2D structural features and 3D QSAR methods like CoMFA and CoMSIA that consider the three-dimensional alignment of compounds and calculate field-based descriptors [11]. Recent advances include the conformationally sampled pharmacophore (CSP) approach, which generates multiple conformations of each ligand to create more comprehensive and predictive models [10].

Molecular Similarity and Virtual Screening

Molecular similarity analysis quantifies structural resemblance between compounds using 2D fingerprint-based or 3D shape-based approaches [11] [5]. Common similarity metrics include the Tanimoto coefficient for fingerprints and Tversky index for pharmacophoric features. These techniques enable:

- Scaffold hopping to identify novel chemotypes that maintain biological activity but possess distinct molecular frameworks

- Bioisosteric replacement to substitute functional groups with alternatives having similar physicochemical properties but potentially improved ADME profiles

- Similarity-based virtual screening to identify novel active compounds from large libraries based on their similarity to known ligands [5]

Table 1: Key LBDD Methodologies and Applications

| Methodology | Key Features | Primary Applications | Common Tools/Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Identifies essential spatial features required for activity | Virtual screening, Lead optimization | HipHop, HypoGen, Catalyst |

| QSAR | Mathematical relationship between descriptors and activity | Activity prediction, Compound prioritization | CoMFA, CoMSIA, CSP-SAR |

| Molecular Similarity | Quantifies structural resemblance between compounds | Scaffold hopping, Virtual screening | Tanimoto coefficient, ROCS |

Performance Comparison: LBDD vs. Structure-Based Methods

Direct comparison studies provide valuable insights into the relative strengths and limitations of ligand-based versus structure-based virtual screening methods. A performance evaluation on ten anti-cancer targets revealed that ligand-based methods using tools like vROCS can produce better early enrichment (EF1%), while both approaches yield similar results at higher enrichment factors (EF5% and EF10%) [12]. This highlights the particular value of ligand-based methods for identifying the most promising candidates from large compound libraries.

Structure-based drug design (SBDD), including molecular docking and free-energy perturbation, requires the 3D structure of the target protein, typically obtained through X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy, or predicted using AI methods like AlphaFold [5]. While these methods provide atomic-level insights into protein-ligand interactions and binding affinities, they face challenges with large, flexible molecules and depend heavily on the quality of the target structure [5].

The integration of both approaches creates a powerful synergistic workflow, where ligand-based methods rapidly filter large compound libraries based on similarity to known actives, and structure-based techniques then apply more computationally intensive docking and binding affinity predictions to the narrowed candidate set [5]. This hybrid strategy leverages the complementary strengths of both methodologies to improve efficiency and success rates in early-stage drug discovery.

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Anti-Cancer Targets [12]

| Virtual Screening Method | EF1% Performance | EF5% Performance | EF10% Performance | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ligand-Based (vROCS) | Better results | Similar to structure-based | Similar to structure-based | Speed, scaffold hopping |

| Structure-Based (FRED Docking) | Lower performance | Similar to ligand-based | Similar to ligand-based | Atomic-level insight, pose prediction |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard QSAR Model Development Protocol

The development of a robust QSAR model follows a systematic experimental protocol [10]:

Compound Selection and Data Curation: Select 20-50 congeneric compounds with experimentally measured biological activity (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki) spanning a wide potency range. Ensure chemical diversity while maintaining structural similarity to establish meaningful SAR.

Molecular Descriptor Calculation:

- Generate optimized 3D structures using molecular mechanics (MMFF94) or quantum mechanical methods (DFT with 6-31G* basis set)

- Calculate relevant molecular descriptors including electronic (HOMO/LUMO energies, partial charges), steric (molar volume, polar surface area), and hydrophobic (logP) properties

- For 3D QSAR, align molecules using common pharmacophoric features or binding hypotheses

Statistical Analysis and Model Validation:

- Apply variable selection methods (genetic algorithm, stepwise regression) to identify most relevant descriptors

- Develop model using partial least squares (PLS) regression with cross-validation

- Validate model externally with test set compounds not used in model development

- Define applicability domain to identify compounds for reliable prediction

Integrated LBDD-SBDD Workflow

Combining ligand-based and structure-based approaches follows logical sequential relationships, as illustrated in the workflow below:

Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening Protocol

A standardized protocol for pharmacophore-based screening includes [11]:

Model Generation: Select a diverse set of 15-30 known active compounds with varying potencies. Generate multiple low-energy conformations for each compound using molecular dynamics or systematic conformational search. Identify common pharmacophoric features through ligand alignment.

Model Validation: Validate the pharmacophore model using a test set of active and inactive compounds. Assess screening efficiency using enrichment factors and receiver operating characteristic curves.

Virtual Screening: Screen large compound libraries (e.g., ZINC, in-house collections) using the validated pharmacophore as a 3D query. Apply additional filters including drug-likeness (Lipinski's Rule of Five), physicochemical properties, and structural diversity.

Hit Validation: Select top-ranked compounds for experimental testing. Include structurally diverse hits to explore novel chemical space and enable scaffold hopping.

Successful implementation of LBDD requires specialized computational tools and data resources. The following table details essential components of the LBDD research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for LBDD

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function in LBDD | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound Databases | ChEMBL, PubChem, ZINC | Source of known actives and screening libraries | Annotated bioactivity data, purchasable compounds, structural information |

| Software Tools | OpenEye ROCS, Schrödinger Phase | 3D shape similarity and pharmacophore screening | Molecular alignment, shape-based scoring, feature mapping |

| QSAR Modeling | MATLAB, R, CSP-SAR | Model development and validation | Descriptor calculation, statistical analysis, predictive modeling |

| Descriptor Packages | Dragon, CDK | Molecular descriptor calculation | 2D/3D descriptors, electronic properties, topological indices |

| Conformational Sampling | OMEGA, CONFLEX | Generate representative conformations | Low-energy conformer generation, ring flexibility handling |

Ligand-based drug design represents a powerful approach in oncology drug discovery, particularly when structural information about the target is limited. By leveraging known active compounds through pharmacophore modeling, QSAR, and molecular similarity methods, researchers can efficiently identify and optimize novel therapeutic agents. The integration of LBDD with structure-based approaches creates a synergistic workflow that maximizes the strengths of both methodologies, accelerating the discovery of new cancer treatments. As computational power and artificial intelligence methods continue to advance, LBDD approaches are expected to become even more accurate and impactful in the ongoing fight against cancer.

In oncology drug discovery, the choice between structure-based and ligand-based design methods is fundamentally dictated by the type of data available, each with distinct requirements, applications, and limitations. Structure-based drug design (SBDD) relies on three-dimensional structural information of the target protein, typically obtained through experimental methods like X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), or cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), or increasingly through computational predictions from tools like AlphaFold [2] [5]. Conversely, ligand-based drug design (LBDD) utilizes information from known active small molecules (ligands) that bind to the target, making it applicable even when the protein structure is unknown [2] [5]. The complementary nature of these approaches has stimulated continued efforts toward developing hybrid strategies that integrate both ligand and target information within a holistic computational framework to enhance drug discovery success [13]. This guide provides an objective comparison of their data requirements, supported by experimental data and methodologies relevant to oncology research.

Data Fundamentals and Methodological Approaches

The foundational data required for each approach differs significantly, influencing project feasibility, resource allocation, and methodological choices.

Table 1: Comparison of Core Data Requirements

| Aspect | Structure-Based Methods | Ligand-Based Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data | 3D protein structure (from PDB, AlphaFold, etc.) [14] [2] | Chemical structures and/or biological activities of known ligands [2] [5] |

| Key Techniques | Molecular docking, binding site prediction, free-energy perturbation [15] [5] | QSAR, Pharmacophore modeling, molecular similarity search [2] [5] |

| Ideal Application Scenario | Target structure is known; designing novel scaffolds; optimizing binding interactions [2] [5] | Target structure is unknown; sufficient known actives exist; scaffold hopping [2] [5] |

| Data Availability Challenge | Obtaining high-quality structures for membrane proteins or flexible targets [2] | Bias towards chemical space of known actives; limited novelty [13] [5] |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

A. Structure-Based Binding Site Prediction

Accurately identifying protein-ligand binding sites is a critical first step in SBDD. Benchmarking studies evaluate numerous computational methods using curated datasets like LIGYSIS, which aggregates biologically relevant protein-ligand interfaces from biological units of multiple structures for the same protein, avoiding artificial crystal contacts [15].

Protocol for Benchmarking Binding Site Predictors:

- Dataset Curation: The LIGYSIS dataset is constructed by clustering biologically relevant protein-ligand interactions from the PDBe biological assemblies, ensuring non-redundant interfaces [15].

- Method Execution: Multiple prediction tools (e.g., VN-EGNN, IF-SitePred, P2Rank, fpocket) are run on the dataset using standard settings [15].

- Performance Metrics: Methods are evaluated using metrics like recall (ability to identify true binding sites) and precision. The top-N+2 recall is proposed as a universal benchmark metric, which accounts for the prediction of the true binding site plus two additional potential sites [15].

- Result: A benchmark of 13 methods showed that re-scoring fpocket predictions with PRANK or DeepPocket achieved the highest recall (60%), while IF-SitePred had the lowest (39%). The study highlighted that stronger pocket scoring schemes could improve recall by up to 14% and precision by 30% [15].

B. Ligand-Based Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR)

QSAR is a cornerstone LBDD technique that relates chemical structure to biological activity through mathematical models.

Protocol for QSAR Modeling:

- Data Collection: A set of compounds with experimentally measured activities (e.g., IC₅₀, Kᵢ) for the target is compiled.

- Descriptor Calculation: Molecular descriptors (e.g., physicochemical properties, topological indices, 3D shape) are computed for each compound [2] [5].

- Model Training: Statistical or machine learning methods (e.g., regression, random forest, neural networks) are used to build a model that relates the descriptors to the activity [16] [5].

- Validation: The model is validated using external test sets or cross-validation to ensure its predictive power and avoid overfitting.

- Application: The trained model predicts the activity of new, untested compounds, enabling virtual screening and prioritization [5].

Integrated Workflows and Performance Comparison

Hybrid and Sequential Approaches

Given the complementary strengths of SBDD and LBDD, integrated workflows are increasingly common, typically implemented in sequential, parallel, or hybrid schemes [13] [16] [5].

Table 2: Combined Workflow Strategies and Outcomes

| Strategy | Description | Reported Outcome/Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Sequential | A funnel approach where LBVS rapidly filters large libraries, followed by more computationally intensive SBVS on the narrowed set [13] [5]. | Optimizes trade-off between computational cost and method complexity; improves overall efficiency in screening ultra-large libraries [16] [5]. |

| Parallel | LBVS and SBVS are run independently, and their results are combined using data fusion algorithms to create a final ranked list [13]. | Increases performance and robustness over single-modality approaches; can mitigate limitations inherent in each method [13] [5]. |

| Hybrid | Integration of LB and SB techniques into a unified framework, such as using interaction fingerprints or AI models trained on both data types [13] [16]. | Leverages synergistic effects; can improve prediction of binding poses and biological activity [13] [5]. |

Performance Data from AI-Driven Methods

Recent advances in artificial intelligence are bridging the gap between SBDD and LBDD. The CMD-GEN framework, for instance, uses a coarse-grained pharmacophore point sampling from a diffusion model to bridge ligand-protein complexes with drug-like molecules, effectively leveraging both structure and ligand information [17]. In benchmark tests, CMD-GEN outperformed other methods in generating drug-like molecules and was successfully validated in designing selective PARP1/2 inhibitors for cancer therapy [17].

For pure protein-ligand complex prediction, the AI system Umol can predict the fully flexible all-atom structure of protein-ligand complexes directly from protein sequence and ligand SMILES information [18]. In performance benchmarks on 428 diverse complexes:

- Umol (blind prediction) achieved an 18% success rate (SR, ligand RMSD ≤ 2 Å).

- Umol-pocket (with pocket information) achieved a 45% SR.

- This compares to a 52% SR for AutoDock Vina, which requires a native holo-protein structure as input [18].

Umol also provides a confidence metric (plDDT); at plDDT >80, the success rate for Umol-pocket rises to 72%, demonstrating the utility of internal scoring for identifying high-quality predictions [18].

Diagram Title: SBDD and LBDD Workflow Integration

Table 3: Key Resources for Structure-Based and Ligand-Based Research

| Resource/Solution | Function/Purpose | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [14] | Primary repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids. | Essential data source for SBDD; provides structures for docking, homology modeling, and binding site analysis. |

| SitesBase [19] | Database of pre-calculated protein-ligand binding site similarities across the PDB. | Enables analysis of molecular recognition and structure-function relationships independent of overall fold. |

| LIGYSIS Dataset [15] | Curated dataset of biologically relevant protein-ligand interfaces from biological units. | Standardized benchmark for developing and validating ligand binding site prediction methods. |

| MAGPIE Software [20] | Tool for visualizing and analyzing interactions between a target ligand and all its protein binders. | Identifies interaction "hotspots" from thousands of complexes, useful for de novo design and analyzing molecular evolution. |

| AlphaFold DB & ModelArchive [14] | Databases of highly accurate predicted protein structures. | Provides structural models for targets with no experimentally solved structure, expanding the scope of SBDD. |

| CHEMBL Database [17] | Manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. | Key resource for LBDD; provides chemical structures and bioactivity data for building QSAR and similarity models. |

The decision to employ structure-based or ligand-based methods in oncology research is fundamentally guided by data availability. SBDD offers atomic-level insight for rational design but is contingent on the availability and quality of a protein structure. LBDD provides a powerful, resource-efficient approach when a set of active ligands is known but may be constrained by the chemical diversity of those ligands. Experimental data and benchmarks confirm that the integration of both approaches—through sequential, parallel, or hybrid strategies—mitigates their individual limitations and leverages their complementary strengths. The ongoing integration of artificial intelligence and multi-dimensional data is further blurring the lines between these paradigms, promising enhanced efficiency and success in the discovery of novel oncology therapeutics.

Historical Evolution and Key Milestones in Oncology Applications

The integration of computational methods has redefined oncology drug discovery, transitioning it from a largely serendipitous process to a rational, targeted endeavor. This guide objectively compares the two predominant computational approaches—structure-based drug design (SBDD) and ligand-based drug design (LBDD)—within the context of oncology research. SBDD relies on the three-dimensional structural information of the target protein (e.g., from X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy) to design molecules that fit precisely into its binding site [2]. In contrast, LBDD is applied when the target structure is unknown; it uses information from known active small molecules (ligands) to predict and design new compounds with similar activity [2]. The evolution of these methods, accelerated by artificial intelligence (AI), has dramatically improved the speed and precision of developing oncology therapeutics, from small-molecule inhibitors to immunomodulatory drugs [21] [22].

Historical Timeline of Key Methodologies

The adoption of computational strategies in oncology has followed a clear trajectory, evolving from foundational ligand-based principles to high-resolution structure-guided design and, most recently, to integrated AI-driven platforms.

Table 1: Historical Evolution of Key Computational Methods in Oncology

| Decade | Dominant Paradigm | Key Methodological Advancements | Sample Oncology Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1980s-1990s | Rise of LBDD | Development of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models and pharmacophore modeling [2]. | Optimization of early tamoxifen-like derivatives for breast cancer [23]. |

| 1990s-2000s | Emergence of SBDD | Broad availability of X-ray crystal structures of oncology targets; development of molecular docking algorithms [2]. | Design of inhibitors for kinase domains in various cancers [17]. |

| 2010s | High-Throughput & Hybrid Screening | Combination of LBDD and SBDD in sequential or parallel workflows to improve screening efficiency [16] [5]. | Virtual screening for hard-to-drug targets like the LRRK2-WDR domain in Parkinson's-related cancer risks [16]. |

| 2020s-Present | AI and Deep Learning Integration | Application of deep generative models (VAEs, GANs), transformer networks, and pretrained machine learning scoring functions (ML SFs) for de novo molecular design and binding affinity prediction [17] [21] [24]. | Generation of selective PARP1/2 inhibitors (CMD-GEN) and discovery of novel STK33 inhibitors for cancer therapy [17] [25]. |

Comparative Performance Analysis of SBDD and LBDD

Benchmarking studies and real-world competitions provide robust data for comparing the performance of structure-based and ligand-based virtual screening methods.

Table 2: Virtual Screening Performance Benchmarking for Oncology-Relevant Targets

| Method / Tool | Target | Performance Metric | Result | Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLANTS + CNN-Score [24] | PfDHFR (WT) | Enrichment Factor at 1% (EF 1%) | 28 | Structure-based docking with machine learning re-scoring. |

| FRED + CNN-Score [24] | PfDHFR (Quadruple Mutant) | Enrichment Factor at 1% (EF 1%) | 31 | SBDD effective against resistant mutant variants. |

| AutoDock Vina (alone) [24] | PfDHFR (WT) | Enrichment Factor at 1% (EF 1%) | Worse-than-random | Highlights limitation of classical scoring functions. |

| MolTarPred [26] | General Target Prediction | Recall & Precision | Highest among 7 methods | Ligand-centric method outperformed other target prediction tools in systematic comparison. |

| CACHE Challenge #1 [16] | LRRK2-WDR (Novel Target) | Success Rate | ~1-2% (across all teams) | Real-world benchmark; most successful teams used combined SBDD/LBDD or SBDD-focused strategies. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Virtual Screening with Machine Learning Re-Scoring

This protocol, used to identify antimalarial agents with relevance to kinase targets in oncology, details the benchmarking of docking tools against wild-type and resistant mutant PfDHFR [24].

- Protein Structure Preparation: Crystal structures of the target (e.g., PDB ID: 6A2M for wild-type) are obtained. Water molecules and redundant chains are removed, followed by hydrogen addition and optimization using tools like OpenEye's "Make Receptor." [24]

- Ligand/Decoy Library Preparation: A benchmark set like DEKOIS 2.0 is used, containing known bioactive molecules and structurally similar but inactive decoys. Multiple conformations are generated for each molecule. [24]

- Molecular Docking: Three docking tools (AutoDock Vina, PLANTS, FRED) are evaluated. The docking grid is defined to encompass the binding site, and compounds are docked into the protein structure. [24]

- Machine Learning Re-scoring: The generated ligand poses are re-scored using pretrained ML scoring functions (e.g., CNN-Score, RF-Score-VS v2) instead of relying solely on the docking tool's native scoring function. [24]

- Performance Analysis: Enrichment factors (EF) and area under the curve (AUC) of ROC curves are calculated to measure the ability to prioritize true active compounds over decoys. [24]

Structure-Based Screening with ML Re-scoring Workflow

Protocol 2: Ligand-Based Target Fishing for Drug Repurposing

This protocol employs ligand-centric similarity searching to identify new targets for existing drugs, a key strategy for oncology drug repurposing [26].

- Database Curation: A comprehensive database of known ligand-target interactions is built, typically from ChEMBL. Entries are filtered for high confidence (e.g., confidence score ≥ 7) and well-annotated targets. [26]

- Fingerprint Calculation: Molecular fingerprints (e.g., Morgan fingerprints with a radius of 2 and 2048 bits) are computed for all molecules in the database and for the query drug molecule. [26]

- Similarity Search: The similarity (e.g., Tanimoto similarity) between the query molecule's fingerprint and every molecule in the database is calculated. [26]

- Target Prediction & Ranking: The targets of the top-N most similar molecules in the database are retrieved. The frequency of each target appearing in this set is used to rank the most likely targets for the query molecule. [26]

- Validation: Predictions are validated by comparing against held-out test sets of known FDA-approved drugs or through experimental assays. [26]

Protocol 3: Integrated AI-DrivenDe NovoMolecular Generation

Frameworks like CMD-GEN represent the cutting edge, combining SBDD and LBDD principles through AI to generate novel, optimized molecules for targets like PARP1/2 [17].

- Coarse-Grained Pharmacophore Sampling: A diffusion model samples a 3D pharmacophore point cloud (representing features like hydrogen bond donors/acceptors) conditioned on the protein pocket's structure. [17]

- Chemical Structure Generation: A separate module (GCPG) uses a transformer encoder-decoder architecture to convert the sampled pharmacophore points into a valid 2D chemical structure (SMILES string), constrained by desired molecular properties. [17]

- Conformation Alignment: The 2D structure is placed into 3D space, aligning its functional groups with the original pharmacophore points to ensure complementary fit with the protein pocket. [17]

- Experimental Validation: The top-ranked generated molecules are synthesized and tested in biochemical and cellular assays to confirm activity and selectivity (e.g., wet-lab validation for PARP1/2 inhibitors) [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Oncology Drug Discovery

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Context in SBDD/LBDD |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids. | Foundation for SBDD; provides initial protein structures for docking and modeling [24]. |

| ChEMBL Database [26] | Manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties and their annotated targets. | Core resource for LBDD; used to train QSAR models and for ligand-centric target fishing [26]. |

| DEKOIS 2.0 Benchmark Sets [24] | Collections of known active molecules and matched decoys for specific protein targets. | Used to objectively evaluate and benchmark the performance of virtual screening methods [24]. |

| Machine Learning Scoring Functions (e.g., CNN-Score, RF-Score-VS) [24] | Pretrained ML models that predict protein-ligand binding affinity from complex structures. | Used to re-score docking outputs, significantly improving enrichment over classical scoring functions [24]. |

| Molecular Fingerprints (e.g., Morgan, ECFP4) [26] | Bit-string representations of molecular structure. | Core to LBDD; used for rapid similarity searching and as features in QSAR models [26]. |

| AlphaFold2 Predicted Structures [16] | Highly accurate computational predictions of protein 3D structures from amino acid sequences. | Expands the scope of SBDD to targets without experimentally solved structures [16]. |

Analysis of Oncology Signaling Pathway Targeting

Computational methods are crucial for targeting specific nodes in dysregulated oncology signaling pathways. The successful discovery of a novel STK33 inhibitor, Z29077885, via an AI-driven screen illustrates this application. STK33 inhibition induces apoptosis by deactivating the STAT3 signaling pathway and causes cell cycle arrest at the S-phase, confirmed by in vitro and in vivo studies showing decreased tumor size [25]. This example demonstrates how computational screening can yield hits with defined mechanisms of action within critical cancer pathways.

STK33 Inhibitor Mechanism in Cancer

The historical evolution of oncology applications reveals a clear trend from distinct, siloed SBDD and LBDD approaches toward powerful, synergistic integrations. Modern AI-driven frameworks like CMD-GEN, which coarse-grain structural information into pharmacophores and then generate specific molecules, exemplify this fusion [17]. The future of computational oncology lies in these hybrid models that leverage the complementary strengths of both paradigms—the precision of structure-based design and the generalizability and speed of ligand-based approaches [16] [5]. This will be critical for addressing persistent challenges such as drug resistance and for accelerating the discovery of next-generation, precision oncology therapeutics.

Techniques, Workflows, and Oncology Case Studies

This guide provides an objective comparison of three foundational structure-based drug design (SBDD) techniques—molecular docking, molecular dynamics (MD), and structure-based virtual screening (SBVS)—within the context of oncology research. As the field increasingly shifts from ligand-based to structure-based paradigms, understanding the performance and application of these tools is crucial for developing targeted cancer therapies.

Comparative Analysis of SBDD Techniques at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core purpose, key performance metrics, and primary limitations of each technique, providing a high-level comparison for researchers.

| Technique | Core Purpose & Role in SBDD | Key Performance Metrics & Typical Outputs | Primary Limitations & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | Predicts the preferred orientation (binding pose) and affinity of a small molecule when bound to a target protein [27]. | • Binding Affinity (kcal/mol): Estimated scores (e.g., -35.77 kcal/mol for a strong binder) [28].• Pose RMSD (Å): Measures pose prediction accuracy [28].• Interaction Maps: Identifies key residue interactions (e.g., with Gln123, His250) [28]. | • Static view of binding [27].• Scoring functions can be inaccurate [27].• Often misses protein flexibility and solvation effects [27]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, assessing the stability and dynamics of a protein-ligand complex [3] [28]. | • RMSD (Å): Measures structural stability (<2-3 Å is stable) [28].• RMSF (Å): Quantifies residual flexibility [28].• Binding Free Energy (kcal/mol): Calculated via MM/GBSA/PBSA (e.g., -35.77 kcal/mol) [3] [28].• H-bond Analysis: Number and persistence of H-bonds over simulation time [29]. | • Extremely high computational cost [3].• Sensitivity to force field parameters [3].• Simulation timescales may not capture all biological events [3]. |

| Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS) | Rapidly computationally screens vast libraries of compounds (e.g., 4,561+ molecules) against a target structure to identify potential "hit" molecules [28]. | • Hit Rate: % of promising candidates identified from the library [28].• Enrichment Factor: How well the method prioritizes active compounds over inactives.• Docking Scores: Primary filter for selecting top candidates [28]. | • Quality depends on docking reliability [27].• High false-positive rate; requires experimental validation [3].• Limited by library size and diversity [28]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for implementation, this section outlines detailed, step-by-step protocols for each technique, based on a cited study that identified potential metallo-β-lactamase (MBL) inhibitors [28].

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS)

This protocol describes a machine learning-enhanced workflow for high-throughput screening.

- Library Preparation: Download a library of compounds (e.g., 4,561 natural products from ChemDiv). Prepare the 3D structures of all ligands using a tool like OpenBabel with the MMFF94 force field for 2500 steps to minimize energy and ensure conformational stability [28].

- Target Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., from the Protein Data Bank, PDB: 4EYL). Remove the native ligand and any crystallographic water molecules. Add hydrogen atoms and assign partial charges using software like AutoDockTools [28].

- Machine Learning-based QSAR Pre-screening:

- Train a QSAR model (e.g., using Random Forest or Support Vector Regression) on known active and inactive compounds from a database like ChEMBL.

- Use molecular descriptors (e.g., MACCS keys) generated by RDKit.

- Screen the entire library with the trained model to predict activity and filter out compounds with poor predicted activity [28].

- Molecular Docking:

- Grid Box Definition: Using AutoDockTools, define a grid box centered on the binding site of the co-crystallized ligand. For example, use center coordinates (2.19, -40.58, 2.22) and dimensions 20x16x16 Å [28].

- Docking Execution: Perform docking simulations with AutoDock Vina, setting an exhaustiveness value of 8-16 to balance accuracy and computational time. Generate multiple poses (e.g., 10) per ligand [28].

- Hit Identification and Clustering:

- Rank compounds based on their normalized docking scores.

- Cluster the top-ranking compounds based on structural similarity (e.g., using Tanimoto similarity and k-means clustering in RDKit) to select chemically diverse hits for further analysis [28].

Protocol 2: Molecular Docking for Binding Pose Analysis

This protocol focuses on the detailed analysis of top hits identified from SBVS.

- Refined Docking: For the selected hit compounds (e.g., the best representative from each cluster), perform a more rigorous docking simulation with a higher exhaustiveness value and a greater number of poses to thoroughly explore the binding pocket.

- Pose Analysis and Selection:

- Visually inspect the top-ranked docking poses.

- Prioritize poses where the ligand forms key interactions with the protein's active site residues (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, pi-stacking).

- Select the most biologically plausible pose for each compound for further validation with MD simulation [28].

Protocol 3: Molecular Dynamics for Binding Stability Assessment

This protocol validates the stability of docking results and provides quantitative binding affinity estimates.

- System Setup:

- Place the protein-ligand complex in a simulation box (e.g., a cubic box) with an appropriate buffer distance (e.g., 10 Å).

- Solvate the system using explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P model) and add ions (e.g., Na⁺ or Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's charge [28].

- Simulation Execution:

- Perform energy minimization to remove steric clashes.

- Gradually heat the system to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K) under constant volume (NVT ensemble).

- Equilibrate the system under constant pressure (NPT ensemble) to achieve correct density.

- Run a production MD simulation for a sufficient timeframe (e.g., 300 ns) using software like GROMACS or AMBER. Use a 2-fs time step [28].

- Trajectory Analysis:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Calculate the protein and ligand RMSD to assess the overall stability of the complex. A stable complex will show a plateau in RMSD over time [28].

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Analyze RMSF to determine the flexibility of individual protein residues.

- Interaction Analysis: Use tools to monitor hydrogen bonds and other non-covalent interactions throughout the simulation.

- Binding Free Energy Calculation: Employ the Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) or MM/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area (MM/PBSA) method on multiple trajectory frames to calculate the binding free energy. A more negative value indicates stronger binding [3] [28].

Experimental Workflow for Integrated SBDD in Oncology

The true power of SBDD is realized when these techniques are used in an integrated, sequential workflow. The diagram below illustrates a typical pipeline for identifying and validating a novel oncology drug candidate.

Integrated SBDD Workflow for Oncology Target

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful implementation of these SBDD techniques relies on a suite of specialized software tools and databases. This table details key resources for oncology drug discovery.

| Tool / Resource Name | Primary Function | Key Application in SBDD |

|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina [28] | Molecular Docking | Used for predicting ligand binding poses and calculating binding affinities. |

| GROMACS / AMBER [28] | Molecular Dynamics | Software suites for running all-atom MD simulations to study protein-ligand complex stability. |

| RDKit [28] | Cheminformatics | An open-source toolkit for cheminformatics, used for calculating molecular descriptors (e.g., for QSAR) and structural clustering. |

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) [28] | Structural Repository | The primary global database for experimentally-determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids, essential for obtaining target structures. |

| ChemDiv Library [28] | Compound Database | A commercial library of diverse chemical compounds, often used as a source for virtual screening. |

| ChEMBL [28] | Bioactivity Database | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, used for training QSAR models. |

Molecular docking, MD simulation, and SBVS are complementary pillars of modern SBDD. Docking and SBVS offer speed and high-throughput capability for initial hit discovery, while MD provides deep, dynamic insights into binding stability and mechanisms. For oncology researchers, the strategic integration of these techniques, from initial virtual screening to rigorous dynamics-based validation, creates a powerful pipeline for rational drug design. This approach directly addresses the limitations of ligand-based methods by enabling the design of novel, high-affinity inhibitors against specific cancer targets, even in the absence of known ligand information, thereby accelerating the development of precision oncology therapies [27] [30].

A Primer on Ligand-Based Drug Discovery

In the landscape of modern drug development, particularly in oncology, computational methods are indispensable for accelerating the identification of novel therapeutic candidates. When the three-dimensional structure of a target protein is unavailable or uncertain, researchers turn to Ligand-Based Drug Discovery (LBDD) methods. These approaches leverage the known chemical structures and biological activities of molecules that interact with a target of interest. The core principle, known as the similarity principle, posits that structurally similar molecules are likely to exhibit similar biological effects [31]. This guide focuses on three essential LBDD methodologies: Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR), Pharmacophore Modeling, and Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS), and objectively compares their performance and applications.

Method Performance and Comparative Data

The utility of LBDD methods is demonstrated by their predictive accuracy and efficiency in real-world drug discovery campaigns. The table below summarizes benchmark data for these methods from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of LBDD Methods

| Method | Reported Performance / Outcome | Context / Target | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| QSAR | R² = 0.793, Q² = 0.692, R²pred = 0.653 [32] | SmHDAC8 Inhibitors (Schistosomiasis) | Predictive Capability |

| 3D-QSAR | R² = 0.9521, Q² = 0.8589 [31] | Anti-tubercular Agents (InhA & DprE1) | Statistical Significance |

| LBVS (ML-Based) | ~1000x faster than molecular docking [33] | MAO Inhibitors (CNS Disorders) | Screening Speed |

| LBVS (Similarity Search) | Identified 2 active compounds [34] | Kinase Inhibitors (Fyn & Lyn, Oncology) | Hit Identification |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) Modeling

QSAR models quantitatively link a molecule's physicochemical properties and structural features (descriptors) to its biological activity. A robust QSAR protocol involves:

- Data Set Curation and Preparation: A series of compounds with experimentally determined activity values (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki) is collected from databases like ChEMBL [33]. The activity is often converted to pIC₅₀ (-log₁₀IC₅₀) to create a more normally distributed parameter for modeling [33] [31]. The data set is then divided into a training set (used to build the model, ~70-85% of data) and a test set (used to validate the model, ~15-30% of data) [31].

- Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Selection: Low-energy 3D structures of all compounds are generated. Thousands of molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP, topological indices, electronic properties) are calculated using software like MOE or RDKit [35]. Redundant or irrelevant descriptors are filtered out to avoid overfitting.

- Model Construction and Validation: The model is built by correlating the selected descriptors with the biological activity using machine learning algorithms such as Random Forest [36]. The model's performance is evaluated using the training set (e.g., R², Q²cv) and, crucially, its predictive power is confirmed using the external test set (R²pred) [32].

Pharmacophore Modeling

A pharmacophore is an abstract model that defines the spatial and functional arrangement of features necessary for a molecule to interact with its target. A structure-based protocol using molecular dynamics (MD) is as follows:

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations of the Apo Protein: An experimentally determined structure of the target protein (e.g., from the PDB) without a bound ligand is placed in a solvated box. An all-atom MD simulation is run for tens to hundreds of nanoseconds to capture the protein's flexible and hydrated state [34]. Software like Amber20 with the AMBER-ff19SB force field is typically used [34].

- Analysis of Water Dynamics and Interaction Hotspots: The trajectories from the MD simulation are analyzed to map the dynamics of explicit water molecules within the binding site. Tools like PyRod are used to generate dynamic molecular interaction fields (dMIFs) from the geometric and energetic properties of these water molecules [34].

- Pharmacophore Feature Generation: The dMIFs are converted into pharmacophore features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions). These features represent consensus interaction points that a ligand must fulfill for high-affinity binding, derived directly from the behavior of the solvent in the apo protein structure [34].

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS)

LBVS prioritizes compounds from large libraries based on their similarity to known active molecules.

- Reference Ligand and Database Selection: One or more potent and well-characterized active compounds are chosen as reference or "query" ligands. A screening database, such as ZINC or PubChem, is selected [33] [31].

- Molecular Representation and Similarity Calculation: Molecules are encoded into a numerical format using molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4, MACCS keys) [37] [26]. The similarity between the query fingerprint and every database compound's fingerprint is calculated using a metric like the Tanimoto coefficient [26].

- Hit Prioritization and Validation: Database compounds are ranked based on their similarity scores. Top-ranking compounds are visually inspected and subjected to further computational and experimental validation to confirm activity [34].

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of LBDD methods relies on a combination of software tools and chemical databases.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for LBDD

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in LBDD |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL [26] | Database | Source of curated bioactivity data for model training and validation. |

| ZINC / PubChem [33] [31] | Database | Libraries of commercially available or synthesizable compounds for virtual screening. |

| RDKit | Software/Chemoinformatics | Open-source toolkit for cheminformatics, descriptor calculation, and fingerprinting. |

| Schrödinger Suite [35] [31] | Software Platform | Integrated platform for molecular modeling, QSAR, pharmacophore modeling, and docking. |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) [35] | Software Platform | All-in-one software for molecular modeling, simulation, and QSAR. |

| PyRod [34] | Software/Tool | Generates water-based pharmacophore models from MD simulation trajectories. |

| Amber20 [34] | Software Suite | Performs molecular dynamics simulations to study protein flexibility and solvation. |

| MACCS Keys / ECFP4 Fingerprints [37] [26] | Molecular Representation | Encodes molecular structure into a bit-string for rapid similarity searching. |

LBDD methods provide a powerful and complementary approach to structure-based methods in oncology research. QSAR models offer quantitative predictive power for activity optimization, while pharmacophore modeling provides an intuitive, feature-based framework for scaffold hopping and understanding key interactions. Ligand-based virtual screening, especially when accelerated by machine learning, offers unparalleled speed for exploring vast chemical spaces [33].

The choice between LBDD and structure-based methods is not mutually exclusive. The most successful drug discovery campaigns often integrate both. LBDD excels when structural data is scarce, when seeking novel chemotypes, or in the early stages of screening. As the field advances, the integration of machine learning and dynamics-based approaches, like water-based pharmacophores, is pushing the boundaries of what is possible with ligand-based design, making it an indispensable part of the modern drug hunter's arsenal.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) is fundamentally reshaping oncology drug discovery, marking a transition from traditional, labor-intensive methods to computationally driven, predictive science. Traditional drug development, often requiring over a decade and billions of dollars, is constrained by high attrition rates, particularly in oncology where tumor heterogeneity and complex microenvironmental factors present unique challenges [38]. AI technologies, encompassing machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and generative models, are now capable of integrating massive, multimodal datasets—from genomic profiles to clinical outcomes—to generate predictive models that dramatically accelerate the identification of druggable targets and the optimization of lead compounds [38] [25].

A central dichotomy in computational drug discovery lies between structure-based and ligand-based methods. Structure-based approaches, exemplified by AlphaFold, rely on the 3D atomic coordinates of a biological target to design molecules that fit into specific binding pockets [39] [40]. In contrast, ligand-based methods utilize knowledge of known active molecules to infer the properties of new drug candidates without direct reference to the target's structure [17]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these methodologies, focusing on their applications, performance metrics, and experimental protocols within oncology research, offering scientists a framework for selecting the optimal tools for their specific research challenges.

Comparative Analysis of Structure-Based and Ligand-Based AI Platforms

The performance of AI-driven drug discovery platforms can be evaluated across multiple dimensions, including prediction accuracy, discovery speed, and success in generating viable clinical candidates. The following section provides a structured comparison of leading platforms, highlighting the distinct advantages and limitations of structure-based and ligand-based paradigms.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Leading AI-Driven Drug Discovery Platforms

| Platform / Model | Primary Approach | Key Capabilities | Reported Performance/Impact | Known Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 3 [41] [39] | Structure-Based | Predicts structures & interactions of proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands, and molecular complexes. | Surpasses traditional docking; predicts protein-ligand interactions with remarkable precision [39]. | Struggles with dynamic/flexible regions, disordered proteins, and multi-state conformations [39] [42]. |

| AlphaFold 2 [41] [40] | Structure-Based | Predicts 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences with high accuracy. | Solved 50-year protein folding challenge; >200 million structures predicted [41]. | Suboptimal for virtual screening; structures often fail to capture ligand-induced conformational changes (apo-to-holo) [40]. |

| Exscientia [38] [43] | Ligand & Structure-Informed | Generative AI for small-molecule design integrated with patient-derived biology. | Designed first AI-drug in clinic; design cycles ~70% faster, require 10x fewer synthesized compounds [43]. | No AI-discovered drug approved yet; some programs discontinued due to therapeutic index concerns [43]. |

| Insilico Medicine [38] [43] | Ligand-Based (Generative AI) | Generative models for target identification and molecular design. | Advanced IPF drug from target to Phase I in 18 months (typical: 3-6 years) [38] [43]. | High reliance on data quality; clinical success of candidates still under evaluation [38]. |

| BInD Model [30] | Structure-Based | Diffusion model that designs drug candidates using only target protein structure. | Generates optimal drug candidates without prior molecular data; designs molecules meeting multiple drug criteria [30]. | Novel methodology; independent validation and extensive clinical testing results are pending [30]. |

| CMD-GEN Framework [17] | Structure-Based | Generates 3D molecules via coarse-grained pharmacophore points conditioned on protein pockets. | Outperforms other generative models in benchmarks; validated in wet-lab for selective PARP1/2 inhibitors [17]. | Architecture is complex, involving multiple hierarchical stages [17]. |

Table 2: Clinical-Stage Output of AI Drug Discovery Platforms (as of 2025)

| Company / Platform | Lead Clinical Candidate(s) | Therapeutic Area | Clinical Stage (as of 2025) | Reported Discovery Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exscientia [43] | DSP-1181 (OCD), GTAEXS-617 (CDK7 inhibitor, oncology), EXS-74539 (LSD1 inhibitor) | Oncology, Immunology, CNS | Phase I/II (GTAEXS-617) | "Substantially faster than industry standards" [43] |

| Insilico Medicine [38] [43] | ISM001-055 (TNK inhibitor, Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis) | Fibrosis, Oncology | Phase IIa (Positive results reported) [43] | 18 months from target to Phase I [38] |

| Schrödinger [43] | Zasocitinib (TAK-279, TYK2 inhibitor) | Immunology | Phase III | N/A (Physics-enabled design strategy) [43] |

| BenevolentAI [38] [43] | Novel targets for Glioblastoma | Oncology | Preclinical / Target Identification | N/A |

The quantitative data reveals that structure-based methods like AlphaFold 3 and CMD-GEN provide an unparalleled view of molecular interactions, which is critical for designing selective inhibitors and understanding complex binding mechanisms [39] [17]. Conversely, ligand-based generative platforms such as those from Exscientia and Insilico Medicine demonstrate a profound ability to accelerate the early drug discovery timeline, compressing years of work into months [43]. For oncology researchers, the choice of method depends on the specific research question: structure-based models are superior for novel targets with unknown ligands, while ligand-based models can rapidly optimize chemical matter when active compounds are already known.

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Understanding the experimental and computational workflows is essential for the practical application and critical assessment of these AI tools.

Protocol: Enhancing AlphaFold2 for Structure-Based Virtual Screening

A significant limitation of using standard AlphaFold2 predictions for virtual screening is their frequent failure to capture the ligand-bound (holo) conformation of a protein, leading to suboptimal results [40]. The following protocol describes a method to explore AlphaFold2's structural space to generate more drug-friendly conformations.

- Input Preparation: Begin with the protein's amino acid sequence and generate a standard multiple sequence alignment (MSA).

- MSA Manipulation: Deliberately introduce alanine mutations at key residues within the predicted ligand-binding site in the MSA. This perturbation encourages AlphaFold2 to sample alternative conformations.

- Iterative Exploration and Guidance:

- Generate a series of 3D protein models using the modified MSAs.

- Perform molecular docking simulations of known active compounds and decoys into each generated model.

- Use a genetic algorithm to optimize the MSA mutation strategy. The algorithm selects mutation patterns that maximize the enrichment of active compounds over decoys in docking poses. If sufficient active compound data is unavailable, a random search strategy can be employed instead.

- Output: The result is an optimized AlphaFold2-derived protein structure that is more amenable to structure-based virtual screening, demonstrating significantly improved performance over the raw prediction [40].

Protocol: Selective Inhibitor Design with CMD-GEN Framework

The CMD-GEN framework is designed to overcome challenges in generating stable, active, and selective molecules by leveraging a hierarchical, structure-based approach [17].

- Coarse-Grained Pharmacophore Sampling:

- Input: The 3D structure of the target protein's binding pocket (e.g., from a crystal structure or AlphaFold prediction).

- Process: A diffusion model samples a cloud of coarse-grained pharmacophore points (e.g., hydrogen bond donors, acceptors, hydrophobic features) conditioned on the geometry and chemical properties of the pocket. This step captures the essential interaction pattern required for binding.

- Chemical Structure Generation:

- Input: The sampled pharmacophore point cloud.

- Process: A transformer-based module (Gating Condition Mechanism and Pharmacophore Constraints, GCPG) translates the pharmacophore points into a valid 2D chemical structure (SMILES string) that possesses the functional groups needed to match the features.

- 3D Conformation Alignment and Output:

- Process: A conformation prediction module aligns the generated chemical structure into a 3D geometry where its functional groups precisely match the spatial arrangement of the sampled pharmacophore points.

- Output: A physically meaningful 3D molecular structure with predicted activity and selectivity, ready for further validation. This workflow has been wet-lab validated through the design of highly effective PARP1/2 selective inhibitors [17].

Workflow Visualization: Structure-Based vs. Ligand-Based AI Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the core workflows and logical relationships of the primary AI approaches in drug discovery.

(caption:AI Drug Discovery Workflow Decision Tree)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The effective application of AI in oncology research relies on a suite of computational and experimental tools. The following table details key resources that form the backbone of this research paradigm.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for AI-Enhanced Oncology Discovery

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Relevance to AI Methodology |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Protein Database [41] | Database | Provides free, immediate access to predicted protein structures for over 200 million proteins. | Foundational resource for structure-based design, especially for targets with no experimental structure. |

| AlphaFold Server [41] | Software Tool | Allows researchers to input protein sequences and receive predicted 3D structures and interactions via a cloud-based platform. | Enables custom structure prediction for novel targets or complexes not in the database. |

| ChEMBL [17] | Database | A large, open-source database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, annotated with experimental data. | Critical training data for ligand-based generative models and for benchmarking new compound designs. |

| CrossDocked Dataset [17] | Dataset | A curated set of protein-ligand complexes with aligned structures, used for training and testing machine learning models. | Standard benchmark for training and evaluating structure-based molecular generation models like CMD-GEN. |

| Molecular Docking Software (e.g., AutoDock, Glide) [40] | Software Tool | Computationally simulates how a small molecule (ligand) binds to a protein target and predicts its binding affinity and pose. | Used for virtual screening of AI-generated compounds and for providing feedback in genetic algorithm-guided structure exploration. |

| BInD Model [30] | AI Model | A diffusion model that designs drug candidates and predicts their binding mechanism using only target protein structure. | Represents a state-of-the-art, "prior-free" structure-based design tool for initiating drug campaigns on novel targets. |

The integration of AI and ML into oncology research marks a definitive paradigm shift from serendipitous discovery to rational, data-driven design. Both structure-based and ligand-based methods offer powerful and complementary paths toward this goal. Structure-based approaches, empowered by AlphaFold's revolutionary capabilities, provide an atomic-level blueprint for designing novel, selective inhibitors, especially for previously "undruggable" targets. Meanwhile, ligand-based generative models dramatically accelerate the optimization of drug-like properties and the exploration of vast chemical spaces.

For the modern oncology researcher, the strategic integration of these tools into a unified workflow is key. The future lies in hybrid systems that leverage the structural insights from platforms like AlphaFold 3 and CMD-GEN to inform and constrain the generative power of ligand-based models, creating a closed-loop, self-improving drug discovery engine [44]. As these technologies mature and their predictions are validated through clinical success, they promise to usher in a new era of precision oncology, delivering safer and more effective therapies to patients at an unprecedented pace.

The table below provides a consolidated overview of the performance data for the featured therapeutic strategies, highlighting their mechanisms, efficacy, and research applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Featured Oncology Therapeutic Strategies

| Therapeutic Approach | Specific Agent / Method | Key Molecular Target | Reported Efficacy (IC50 or Model Response) | Primary Clinical/Research Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PARP1-Selective Inhibition | Saruparib (AZD5305) | PARP1 | Preclinical CRR: 75% in HRD PDX models; median PFS >386 days [45] | BRCA1/2-associated cancers; superior antitumor activity vs. non-selective PARP1/2 inhibitors [45] |

| PARP1/2 Inhibition (1st Gen) | Olaparib | PARP1 & PARP2 | Preclinical CRR: 37% in HRD PDX models; median PFS 90 days [45] | HRR-deficient cancers; benchmark for first-generation PARP inhibitors [46] [45] |

| βIII-Tubulin Targeting | Vinorelbine + BET Inhibitor (iBET-762) | βIII-tubulin (TUBB3) | 75% long-term survival in mouse BM model; tumor volume reduction [47] | Breast cancer brain metastases; sensitization strategy [47] |

| Dual EGFR/PARP-1 Inhibition | Compound 4f (Spirooxindole-triazole hybrid) | EGFR & PARP1 | PARP-1 IC50: 18.4 nM; Cytotoxicity IC50: 1.9 μM (HepG2) [48] | Targeted liver cancer therapy; multi-targeted agent [48] |

PARP1 Inhibitors: Mechanism and Clinical Evolution

Core Mechanism of Action and Synthetic Lethality

PARP1 (Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1) is a crucial DNA damage sensor and a primary target in oncology. Its enzyme activity is rapidly activated by DNA single-strand breaks (SSBs), leading to the synthesis of poly (ADP-ribose) (PAR) chains. This PARylation serves as a platform to recruit DNA repair proteins, such as XRCC1, essential for the repair of SSBs via the base excision repair/single-strand break repair (BER/SSBR) pathway [46] [49].

PARP inhibitors (PARPi) exploit a concept called synthetic lethality. They exert their cytotoxic effect through two primary mechanisms:

- Catalytic Inhibition: Blocking PARP1's enzymatic activity, preventing autoPARylation and the recruitment of repair factors, leading to the accumulation of unrepaired SSBs [46] [49].

- PARP Trapping: Stabilizing the PARP-DNA complex at the site of damage, which is more cytotoxic than catalytic inhibition alone. These trapped complexes collide with and stall the replication fork, causing its collapse into highly toxic double-strand breaks (DSBs) [46] [50] [45].

In healthy cells with functional Homologous Recombination Repair (HRR), these DSBs are effectively repaired. However, in cancer cells with pre-existing HRR deficiencies (e.g., due to BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations), the loss of both major DNA repair pathways (SSBR via PARP inhibition and DSBR via HRR deficiency) leads to genomic instability and cell death [46] [49].

The Shift to PARP1-Selective Inhibitors

First-generation PARPi (e.g., Olaparib, Talazoparib) inhibit both PARP1 and PARP2. While clinically effective, their use is limited by toxicity, particularly hematological toxicity linked to PARP2 inhibition, and the development of resistance [46] [45].

Recent research has established that synthetic lethality in BRCA-mutated cancers is primarily dependent on PARP1 inhibition, not PARP2 [46]. This discovery has driven the development of next-generation, highly selective PARP1 inhibitors, such as Saruparib (AZD5305).

Table 2: Comparison of PARP Inhibitor Profiles

| Inhibitor | Selectivity | Key Efficacy Data (Preclinical) | Key Toxicity and Resistance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saruparib (AZD5305) | PARP1-Selective | 75% pCRR; Median PFS >386 days; profound antitumor response in PDX models [45] | Improved safety profile; reduced hematological toxicity; delays resistance [45] |

| Olaparib | PARP1/2 | 37% pCRR; Median PFS 90 days in PDX models [45] | Hematological toxicity (anemia, neutropenia) associated with PARP2 inhibition [46] [45] |

| Talazoparib | PARP1/2 | Most potent PARP trapper (100x more than Olaparib) [50] | Hematological toxicity; non-selective profile [46] [50] |