Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling in Discovery Studio: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to structure-based pharmacophore generation using BIOVIA Discovery Studio, a leading software platform in computer-aided drug design.

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling in Discovery Studio: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to structure-based pharmacophore generation using BIOVIA Discovery Studio, a leading software platform in computer-aided drug design. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of pharmacophore modeling, detailed methodological workflows for virtual screening and lead optimization, strategies for troubleshooting and model refinement, and rigorous validation techniques. By integrating over 30 years of peer-reviewed research, Discovery Studio enables the efficient identification of novel therapeutic candidates through the abstraction of key steric and electronic features from protein-ligand complexes, significantly accelerating the drug discovery process from target identification to lead optimization.

Understanding Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: Core Concepts and Discovery Studio's Role in CADD

The pharmacophore concept stands as one of the most enduring and influential paradigms in medicinal chemistry and computer-aided drug design. At its core, a pharmacophore represents the essential molecular framework responsible for a drug's biological activity. According to the modern IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) definition, a pharmacophore is "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [1]. This definition emphasizes the abstract nature of pharmacophores as patterns of features rather than specific chemical structures, enabling the identification of structurally diverse ligands that bind to a common receptor site [2].

The power of the pharmacophore concept lies in its ability to transcend specific molecular scaffolds and focus on the fundamental interactions necessary for biological activity. This abstraction enables researchers to navigate chemical space more efficiently, identifying novel active compounds through virtual screening and providing critical insights for lead optimization in drug discovery campaigns [3]. In the context of structure-based drug design using tools like Discovery Studio, pharmacophore modeling serves as a critical bridge between structural biology and medicinal chemistry, facilitating the rapid identification and optimization of potential therapeutic agents [4].

Historical Evolution of the Pharmacophore Concept

The conceptual foundation of pharmacophores has evolved significantly over more than a century, with contributions from multiple key researchers shaping our modern understanding.

Key Milestones in Pharmacophore History

Table 1: Historical Evolution of the Pharmacophore Concept

| Year | Researcher | Contribution | Conceptual Advancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1898 | Paul Ehrlich | Introduced concept of "molecular framework" carrying essential features for biological activity | Original concept of specific chemical groups responsible for therapeutic effects [5] |

| 1960 | F.W. Schueler | Used term "pharmacophoric moiety" and expanded to spatial patterns of abstract features | Bridge between original and modern concepts [2] [5] |

| 1967-1971 | Lemont B. Kier | Popularized the modern term "pharmacophore" in publications | Established widespread adoption of the term and concept [2] [5] |

| 1998 | IUPAC | Formal definition of pharmacophore in Recommendations 1998 | Standardized the modern abstract definition used today [2] [1] |

| 2000s-Present | Various Researchers | Computational implementation in software platforms | Transition from theoretical concept to practical drug discovery tool [3] |

The historical trajectory of the pharmacophore concept reveals a fascinating evolution from concrete chemical groups to abstract molecular patterns. Historical accounts frequently credited Paul Ehrlich with originating the concept in the early 1900s, though recent scholarship has revealed that this attribution stemmed from an erroneous citation in the 1960s [5]. While Ehrlich undoubtedly pioneered early concepts of structure-activity relationships, his work did not explicitly use the term "pharmacophore." Instead, contemporary researchers used the term to describe features responsible for biological effects, with Schueler (1960) and Kier (1967-1971) playing pivotal roles in refining and popularizing the modern concept [2] [5].

This historical clarification does not diminish Ehrlich's foundational contributions to medicinal chemistry but rather highlights how scientific concepts evolve through collaborative refinement across generations of researchers. The transition from specific chemical groups to abstract feature-based patterns has significantly expanded the utility of pharmacophores in contemporary drug discovery, particularly in scaffold hopping and de novo design applications [6].

Figure 1: Historical Evolution of the Pharmacophore Concept

Core Features and Methodological Approaches

Essential Pharmacophore Features

The steric and electronic features that comprise a pharmacophore represent the fundamental interactions necessary for molecular recognition and biological activity. These features are defined generically to enable recognition of diverse chemical groups with similar properties [2].

Table 2: Core Pharmacophore Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature Type | Geometric Representation | Complementary Feature | Interaction Type | Structural Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen-Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Vector or Sphere | Hydrogen-Bond Donor | Hydrogen Bonding | Carbonyl groups, ethers, alcohols [6] |

| Hydrogen-Bond Donor (HBD) | Vector or Sphere | Hydrogen-Bond Acceptor | Hydrogen Bonding | Amines, amides, hydroxyl groups [6] |

| Hydrophobic (H) | Sphere | Hydrophobic | Hydrophobic Interactions | Alkyl chains, aromatic rings [2] |

| Positive Ionizable (PI) | Sphere | Negative Ionizable | Ionic Interactions | Ammonium ions, protonated amines [6] |

| Negative Ionizable (NI) | Sphere | Positive Ionizable | Ionic Interactions | Carboxylates, phosphates [6] |

| Aromatic (AR) | Plane or Sphere | Aromatic, Positive Ionizable | π-Stacking, Cation-π | Phenyl, pyridine rings [6] |

In addition to these chemical features, pharmacophore models often incorporate exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints of the binding site, preventing ligand atoms from occupying regions occupied by the receptor [6]. The balance between feature generality and specificity represents a critical consideration in model development—overly general features may increase false positives, while excessively specific definitions may miss structurally novel active compounds [7].

Pharmacophore Generation Methodologies

The generation of pharmacophore models generally follows two principal methodologies, each with distinct advantages and requirements.

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based approaches derive pharmacophore models directly from the three-dimensional structure of a target protein, typically in complex with a ligand. This methodology leverages precise structural information from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy to identify key interaction points between the ligand and binding site [8]. The process involves:

- Analysis of ligand-receptor complex to identify key molecular interactions

- Feature mapping of complementary chemical features in the binding site

- Spatial relationship determination between identified features

- Exclusion volume assignment based on protein structure [6]

Structure-based pharmacophore generation provides critical insights into essential ligand-receptor interactions without requiring multiple known active compounds. This approach has been successfully applied in numerous drug discovery campaigns, such as the identification of novel PD-L1 inhibitors from marine natural products [8] and XIAP inhibitors for cancer therapy [9].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

When three-dimensional structural information of the target is unavailable, ligand-based approaches provide a powerful alternative. This methodology derives common chemical features from a set of structurally diverse known active compounds that bind to the same biological target [3]. The key steps include:

- Training set selection of structurally diverse active molecules

- Conformational analysis to explore accessible low-energy conformations

- Molecular superimposition to identify common spatial arrangements

- Feature abstraction to convert structural alignment to pharmacophore features [2]

Successful ligand-based pharmacophore modeling requires that all training set compounds bind to the same receptor site in a similar orientation, and the quality of the resulting model depends heavily on the structural diversity and accuracy of biological data for the training set molecules [7].

Experimental Protocol: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Using Discovery Studio

This protocol details the generation of structure-based pharmacophore models using Discovery Studio software, specifically tailored for researchers targeting biological macromolecules with known three-dimensional structures.

Receptor-Ligand Complex Preparation

Import Protein Structure: Retrieve the target protein structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) and import into Discovery Studio. For XIAP protein studies, PDB ID: 5OQW has been successfully utilized [9].

Structure Preparation:

- Remove extraneous water molecules, except those mediating critical ligand-receptor interactions

- Add missing hydrogen atoms and assign appropriate protonation states at physiological pH

- Repair missing side chains or loops using protein modeling tools

Ligand Preparation:

- Extract the native ligand from the binding site

- Ensure correct bond orders and formal charges

- Optimize geometry using molecular mechanics force fields

Pharmacophore Feature Generation and Model Validation

Feature Mapping:

- Access the pharmacophore generation module within Discovery Studio

- Select the prepared receptor-ligand complex as input

- Choose appropriate feature definitions based on expected interaction types

- Execute feature mapping to identify potential pharmacophore elements [4]

Model Generation:

- Generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses from the feature map

- Select models with comprehensive feature representation while maintaining chemical relevance

- Incorporate exclusion volumes to represent binding site constraints

Model Validation:

- Employ receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to evaluate model discrimination capability

- Calculate area under the curve (AUC) values, with values >0.7 indicating acceptable performance [9]

- Determine early enrichment factors (EF1%) to assess performance in identifying active compounds from decoy sets [9]

- Validate with known active and inactive compounds not included in model generation

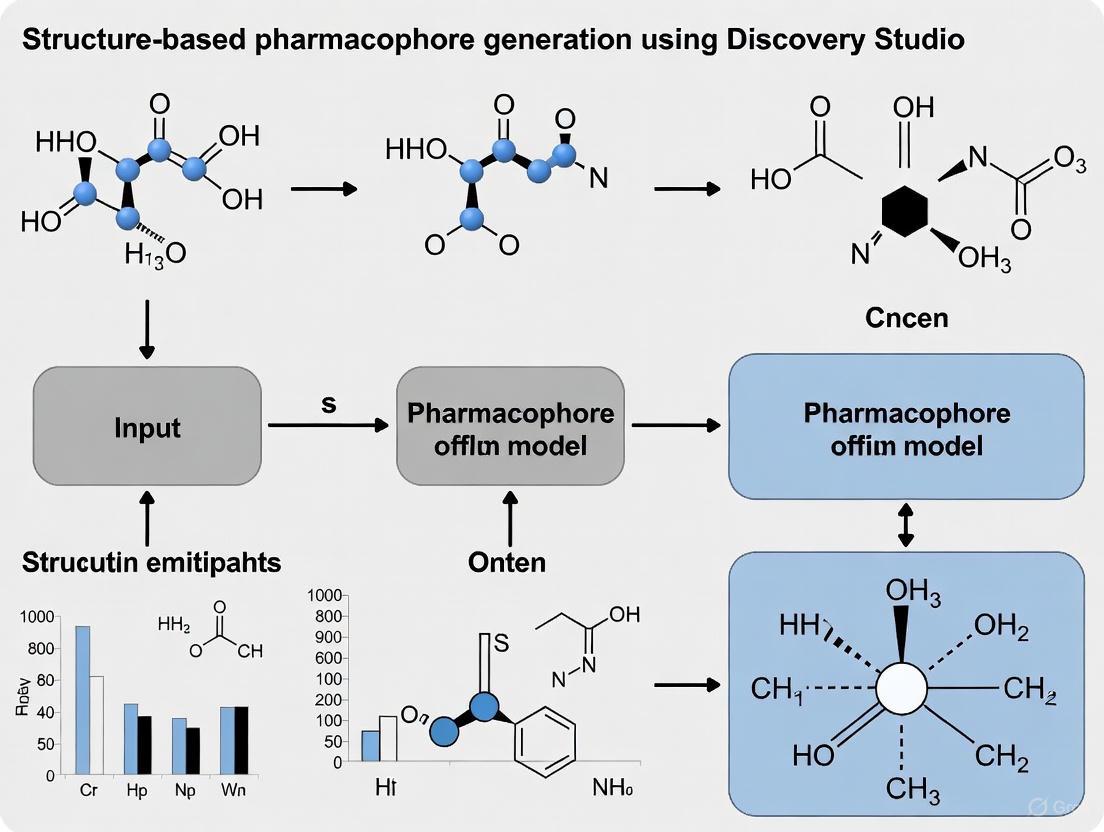

Figure 2: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow in Discovery Studio

Virtual Screening and Hit Identification

Database Preparation:

- Curate 3D compound databases such as ZINC, Marine Natural Products, or in-house collections

- Generate multiple conformers for each compound to ensure comprehensive coverage

- Apply drug-like filters (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) to focus on potentially viable compounds

Pharmacophore-Based Screening:

- Use the validated pharmacophore model as a 3D query against prepared databases

- Apply flexible search algorithms to account for ligand conformational flexibility

- Retrieve compounds matching pharmacophore features within spatial tolerance

Hit Prioritization:

Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore Modeling

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling and Applications

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Platforms | Discovery Studio [4], Catalyst [7], LigandScout [9] | Pharmacophore model generation, validation, and virtual screening | Automated feature identification, support for both structure-based and ligand-based approaches |

| Compound Databases | ZINC Database [9], Marine Natural Product Databases [8] | Sources of compounds for virtual screening | Curated collections with 3D structures, commercial availability information |

| Protein Structure Resources | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [9] | Source of 3D macromolecular structures for structure-based design | Experimentally validated structures with resolution quality metrics |

| Validation Tools | DUD/E Decoy Sets [9] | Pharmacophore model validation | Matched decoy compounds with similar physicochemical properties but dissimilar structures |

| Conformational Sampling Tools | CAESAR, Cyndi [3] | Generation of representative conformational ensembles | Efficient exploration of conformational space with various algorithms |

Applications in Modern Drug Discovery

The utility of pharmacophore modeling extends across multiple stages of the drug discovery pipeline, from initial hit identification to lead optimization campaigns.

Virtual Screening and Scaffold Hopping

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening represents one of the most successful applications of the concept, enabling efficient exploration of vast chemical spaces to identify novel bioactive compounds. Unlike structure-based docking methods, pharmacophore approaches reduce problems associated with explicit molecular flexibility and scoring function inaccuracies [3]. The inherent "scaffold hopping" capability of pharmacophore models allows identification of structurally diverse compounds that share essential interaction features, facilitating the discovery of novel chemotypes with reduced intellectual property constraints [6]. Successful applications include identification of novel Spleen Tyrosine Kinase inhibitors [3] and transforming growth factor-β inhibitors [3] using pharmacophore-based screening approaches.

De Novo Design and Lead Optimization

Pharmacophore models serve as valuable blueprints for de novo design programs, guiding the construction of novel molecular entities that satisfy essential interaction criteria. The NEWLEAD program represented one of the first examples of pharmacophore-based de novo design, generating novel structures that conform to pharmacophore constraints [3]. In lead optimization campaigns, pharmacophore models provide critical insights into structure-activity relationships, highlighting essential features that must be conserved versus regions amenable to modification for improving pharmacokinetic properties or reducing toxicity [3].

Multi-Target Drug Design

The emergence of polypharmacology and network pharmacology approaches has created new opportunities for pharmacophore modeling in multi-target drug design. By identifying common pharmacophore elements across different targets, researchers can design compounds with desired activity profiles against multiple therapeutic targets [3]. This approach is particularly valuable in complex diseases like cancer and neurological disorders, where modulating multiple pathways often produces superior therapeutic outcomes compared to single-target inhibition.

The pharmacophore concept has evolved significantly from its historical roots to become an indispensable tool in modern computer-aided drug design. The transition from concrete chemical groups to abstract feature patterns has expanded its utility in addressing contemporary drug discovery challenges, particularly in scaffold hopping and de novo design applications. Structure-based pharmacophore modeling using platforms like Discovery Studio provides a powerful methodology for leveraging structural biology information to guide efficient compound identification and optimization.

Despite considerable advances, pharmacophore approaches continue to face challenges related to conformational sampling, feature definition, and model validation that warrant ongoing methodological development. The integration of pharmacophore modeling with other computational approaches—including molecular dynamics simulations, machine learning, and free energy calculations—represents a promising direction for enhancing predictive accuracy and expanding applications in drug discovery. As structural information continues to grow through structural genomics initiatives and cryo-EM advancements, structure-based pharmacophore modeling is poised to play an increasingly central role in accelerating therapeutic development across diverse disease areas.

A pharmacophore is defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [7] [10] [11]. It represents the fundamental molecular framework containing the essential chemical functionalities required for biological activity, independent of specific molecular scaffolds [10]. Pharmacophore models abstract specific atoms and functional groups into generalized chemical features, mapping them in three-dimensional space to define the optimal stereo-electronic arrangement for target binding [7] [10].

In modern computer-aided drug discovery (CADD), pharmacophore approaches serve as powerful tools for virtual screening, scaffold hopping, lead optimization, and multi-target drug design [10] [12]. By focusing on essential interaction features rather than specific chemical structures, pharmacophore models enable researchers to identify structurally diverse compounds that maintain the required binding capabilities, significantly accelerating the drug discovery process [12] [13].

Core Pharmacophoric Features and Their Geometric Representation

Fundamental Feature Definitions

The most critical pharmacophoric features include hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrophobic areas (H), and positively or negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI) [7] [10]. These features represent the key molecular interaction capabilities that facilitate binding between a ligand and its biological target through various non-covalent interactions [11].

Table 1: Core Pharmacophoric Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature Type | Chemical Groups | Target Interactions | Geometric Representation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Carbonyl oxygen, nitrogen in heterocycles, ether oxygen | Hydrogen bonding with donor groups | Vector or sphere projecting interaction direction |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | Amine groups, hydroxyl groups, amide NH | Hydrogen bonding with acceptor groups | Vector or sphere with projection point |

| Hydrophobic Area (H) | Alkyl chains, aromatic rings, steroid skeletons | Van der Waals interactions | Spheres representing hydrophobic volume |

| Positively Ionizable (PI) | Primary, secondary, tertiary amines | Ionic interactions with acidic groups | Sphere with positive charge indication |

| Negatively Ionizable (NI) | Carboxylic acids, tetrazoles, acidic heterocycles | Ionic interactions with basic groups | Sphere with negative charge indication |

| Aromatic Ring (AR) | Phenyl, pyridine, other aromatic systems | Cation-π, π-π stacking, hydrophobic interactions | Ring plane with centroid and normal vector |

Spatial Representation and Constraints

In computational implementations, these chemical features are represented as geometric entities—typically as spheres, vectors, or planes with specific spatial constraints [10]. For example, hydrogen bond donors and acceptors are often represented as vectors with specific directions and angles, while hydrophobic and ionizable features are represented as spheres with defined radii [7]. The spatial arrangement of these features creates a unique "fingerprint" that defines the complementary interaction pattern required for binding to a specific biological target [10] [11].

Additional spatial restrictions can be incorporated through exclusion volumes (XVOL), which represent forbidden areas that account for steric clashes with the target binding site [10]. These exclusion volumes are crucial for improving the selectivity of pharmacophore models by eliminating compounds that might have the correct chemical features but incorrect steric properties [10].

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling in Discovery Studio

Theoretical Framework

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling utilizes the three-dimensional structure of a macromolecular target to derive essential interaction features [10]. This approach requires knowledge of the target's structure, obtained through experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy, or NMR spectroscopy, or through computational techniques like homology modeling when experimental structures are unavailable [10] [11]. The recent advances in protein structure prediction, exemplified by tools like AlphaFold2, have significantly expanded the applicability of structure-based pharmacophore modeling to targets without experimentally solved structures [10].

The fundamental principle underlying structure-based pharmacophore generation is the identification of key interaction points within the target's binding site that are complementary to ligand functional groups [10]. These interaction points are then translated into pharmacophoric features that collectively define the optimal binding requirements for potential ligands [10].

Workflow for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation

The generation of structure-based pharmacophores in Discovery Studio follows a systematic workflow that ensures comprehensive analysis of the binding site and accurate feature identification [10] [12].

Diagram 1: Structure-based pharmacophore generation workflow in Discovery Studio

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation from Protein Structures

Objective: To generate a comprehensive pharmacophore model from a prepared protein structure with a defined binding site.

Materials and Software:

- BIOVIA Discovery Studio 2025 [14] [12]

- Protein Data Bank (PDB) structure or homology model

- Validated binding site coordinates

Methodology:

Protein Structure Preparation

- Import the protein structure from PDB format or computational model

- Add hydrogen atoms appropriate for physiological pH (7.4)

- Optimize hydrogen bonding networks using Protonate protocol

- Remove crystallographic water molecules unless functionally important

- Energy minimization using CHARMm forcefield with implicit solvation

Binding Site Characterization

- Execute Binding Site Detection protocol to identify potential binding pockets

- Analyze pocket dimensions, hydrophobicity, and residue composition

- Select primary binding site based on biological relevance and pocket properties

- Generate exclusion volumes to represent protein steric constraints

Pharmacophore Feature Generation

- Run Receptor-Ligand Pharmacophore Generation protocol

- Select feature types: HBA, HBD, Hydrophobic, Ionizable, Aromatic

- Set feature tolerance radii to 1.0-1.5 Å for optimal matching

- Generate multiple hypothesis models with varying feature combinations

Feature Validation and Selection

- Evaluate generated features against known active ligands

- Remove redundant or sterically incompatible features

- Validate feature conservation across related protein structures if available

- Finalize minimal essential feature set for optimal selectivity

Expected Outcomes: A validated structure-based pharmacophore model containing 4-7 essential features with defined spatial relationships, suitable for virtual screening campaigns.

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

Virtual Screening with Pharmacophore Models

Pharmacophore models serve as powerful queries for virtual screening of large compound databases [10] [12]. The abstract nature of pharmacophore features enables identification of structurally diverse compounds that share essential binding characteristics, facilitating scaffold hopping and identification of novel chemotypes [10].

In Discovery Studio, the Pharmacophore Screening protocol allows efficient searching of large compound collections, with the capability to consider the full conformational space of database molecules [12]. The recent 2025 release includes enhancements to the PharmaDB database, which now contains approximately 240,000 receptor-ligand pharmacophore models built from and validated using the scPDB database [14] [12]. This extensive database enables comprehensive off-target activity profiling and drug repurposing studies [12].

Integration with Molecular Dynamics and MM-GBSA

Advanced pharmacophore applications in Discovery Studio integrate with molecular dynamics simulations and binding energy calculations [14]. The Dynamics (NAMD) protocol includes a new "Enable GPU-Resident Mode" parameter in the 2025 release, significantly improving performance on Linux systems for more efficient sampling of conformational dynamics [14].

The Calculate Mutation Energy protocols have been updated to reduce differences in energy values when running on different operating systems, providing more consistent results for binding affinity predictions [14]. These protocols enable refinement of pharmacophore models based on dynamic binding site behavior and energy decomposition analysis.

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function in Pharmacophore Modeling | Discovery Studio Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CATALYST Module | Software Algorithm | Pharmacophore model generation, validation, and screening | Core pharmacophore engine in Discovery Studio [12] |

| PharmaDB | Database | ~240,000 receptor-ligand pharmacophore models for virtual screening | Updated in DS 2025 based on scPDB 2024 [14] [12] |

| CHARMM Forcefield | Molecular Mechanics | Protein and ligand energy minimization and dynamics | Enhanced to handle systems up to 1 million atoms [14] |

| GOLD Docking | Docking Software | Validation of pharmacophore models through molecular docking | Supported in DS 2025 with improved torsion sampling [14] |

| ZDOCK | Protein-Protein Docking | Pharmacophore generation for protein-protein interaction inhibitors | GPU-accelerated in DS 2025 using CUDA 11.4 [14] |

| Exclusion Volumes | Modeling Feature | Represent steric constraints of binding pocket | Critical for structure-based pharmacophore specificity [10] |

Protocol 2: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Generation

Objective: To develop a quantitative pharmacophore model from a set of known active compounds using ligand-based approaches when structural target information is unavailable.

Materials:

- Set of 15-30 compounds with known biological activities (IC50, Ki, or EC50 values)

- BIOVIA Discovery Studio with CATALYST module [12]

- Conformational models for all active compounds

Methodology:

Compound and Data Preparation

- Curate training set with minimum 3 orders of magnitude activity range

- Generate diverse conformational models for each compound using Generate Conformations protocol

- Define activity thresholds for active, moderately active, and inactive classifications

Common Feature Pharmacophore Generation

- Execute Common Feature Pharmacophore Generation protocol

- Select chemical features: HBA, HBD, Hydrophobic, Aromatic, Ionizable

- Set minimum and maximum features to identify (typically 3-5 features)

- Generate multiple hypotheses with varying feature combinations

Quantitative Pharmacophore Model (HypoGen)

- Run HypoGen Algorithm for quantitative model generation

- Input experimental activity values for all training set compounds

- Set statistical confidence level (typically 95-99%)

- Generate top 10 hypotheses ranked by correlation coefficient

Model Validation and Refinement

- Test hypothesis against test set compounds not used in training

- Evaluate predictive accuracy using correlation plot (experimental vs. predicted activity)

- Assess catScramble statistical significance (should exceed 95% confidence)

- Optimize feature tolerances based on validation results

Expected Outcomes: A validated quantitative pharmacophore model capable of predicting compound activity within 0.5 log units of experimental values, with defined feature contributions to binding affinity.

Recent Advances and Future Directions

Integration with Deep Learning Approaches

Recent advances combine traditional pharmacophore methods with deep learning architectures for improved bioactive molecule generation [13]. The Pharmacophore-Guided deep learning approach for bioactive Molecule Generation (PGMG) uses graph neural networks to encode spatially distributed chemical features and transformer decoders to generate molecules matching specific pharmacophores [13]. This approach addresses the challenge of data scarcity in drug discovery by using pharmacophore hypotheses as a bridge to connect different types of activity data [13].

Antibody Paratope Prediction

The Discovery Studio 2025 release introduces new capabilities for antibody paratope prediction, including the Predict Antibody Paratopes protocol and Antibody Paratopes Prediction component [14]. These tools predict antigen binding site residues in antibody CDR loops, extending pharmacophore concepts to biologics and antibody-drug conjugates [14].

Enhanced Molecular Dynamics and Free Energy Calculations

Recent improvements in molecular dynamics protocols in Discovery Studio enable more accurate assessment of binding interactions and free energy landscapes [14]. The Estimate Free Energy Landscape protocol now runs with CSV input data, while the Analyze Trajectory protocol returns non-bond interaction data for trajectories containing more than 10,000 frames [14]. These enhancements support more rigorous validation of pharmacophore models against dynamic binding processes.

The strategic application of pharmacophore modeling, focusing on key features including hydrogen bond acceptors/donors, hydrophobic areas, and ionizable groups, provides a powerful framework for structure-based drug design. Integration of these approaches within BIOVIA Discovery Studio, particularly with the recent 2025 enhancements, offers researchers comprehensive tools for efficient virtual screening and lead optimization. The continued evolution of pharmacophore methods, including integration with deep learning and enhanced dynamics capabilities, promises to further accelerate the drug discovery process across diverse target classes.

The Critical Role of Structure-Based Pharmacophores in Modern Drug Discovery

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling is an indispensable computational technique in modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to rapidly identify and optimize novel therapeutic candidates. A pharmacophore is defined as an abstract description of the steric and electrochemical features essential for a molecule to interact with a biological target and trigger a specific pharmacological response [12]. In structure-based approaches, these models are generated directly from the three-dimensional structure of a target protein, typically in complex with a ligand, mapping key interaction points within the binding site [9]. This methodology has transformed early drug discovery by providing a efficient framework for virtual screening and rational drug design, significantly accelerating the identification of promising lead compounds.

The integration of structure-based pharmacophore modeling into commercial software platforms like BIOVIA Discovery Studio has democratized access to these advanced computational techniques. Discovery Studio utilizes the CATALYST Pharmacophore Modeling and Analysis toolset, which supports comprehensive pharmacophore generation from receptor binding sites and receptor-ligand complexes [12]. The recently released 2025 version includes enhanced protocols such as the Interaction Pharmacophore Generation protocol, which now supports producing a diverse set of pharmacophores in addition to top-scoring pharmacophores, greatly expanding the utility of this approach for exploring multiple binding modes and mechanisms of action [14].

Key Methodological Approaches and Protocols

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation Workflow

The generation of a structure-based pharmacophore follows a systematic protocol that ensures comprehensive mapping of the protein-ligand interaction landscape. The standard workflow implemented in Discovery Studio begins with protein preparation, which involves adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and optimizing the side-chain conformations of residues within the binding pocket. Following preparation, the pharmacophore features are identified based on the interaction patterns between the protein and a bound ligand. These features typically include hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrophobic regions (HyPho), aromatic moieties (Ar), and charged groups [15].

Advanced implementations, such as those described in recent scientific literature, employ sophisticated algorithms to enhance model quality. The O-LAP tool introduces a graph clustering approach where overlapping ligand atoms from multiple docked poses are clustered to form representative centroids, creating shape-focused pharmacophore models that significantly improve virtual screening enrichment [16]. Similarly, emerging AI-driven methods like PharmacoForge utilize diffusion models conditioned on protein pocket structures to generate pharmacophores with optimized properties for virtual screening [17].

Experimental Protocol: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation using Discovery Studio

Objective: To generate and validate a structure-based pharmacophore model from a protein-ligand complex for virtual screening applications.

Materials and Software Requirements:

- BIOVIA Discovery Studio 2025 or later

- Protein Data Bank (PDB) file of target protein in complex with a ligand

- High-performance computing workstation

Methodology:

Protein Structure Preparation:

- Import the PDB structure file (e.g., 5OQW for XIAP protein study) into Discovery Studio.

- Execute the "Prepare Protein" protocol to add hydrogen atoms, assign partial charges, and correct any missing residues or atoms.

- Remove crystallographic water molecules except those involved in key ligand-binding interactions.

Binding Site Analysis:

- Use the "Define and Edit Binding Site" tool to characterize the binding cavity based on the co-crystallized ligand position.

- Analyze key residues involved in ligand recognition and interaction.

Pharmacophore Feature Generation:

- Access the "Interaction Pharmacophore Generation" protocol within the "Ligand and Pharmacophore-based Design" module.

- Set parameters to include hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic features, aromatic rings, and charged groups.

- Generate multiple hypothesis models with diverse feature combinations.

Model Validation:

- Validate generated pharmacophore models using a set of known active compounds and decoy molecules.

- Employ receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and calculate enrichment factors (EF) at 1% threshold to quantify model performance.

- Select the optimal model based on AUC values (models with AUC >0.9 considered excellent) [9].

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If the generated model contains excessive features, adjust the feature tolerance parameters to merge proximal features of the same type.

- For models with poor enrichment factors, consider generating ensemble pharmacophores from multiple protein-ligand complexes.

Case Study: Application in XIAP-Targeted Cancer Therapy

Implementation and Results

A compelling application of structure-based pharmacophore modeling recently demonstrated its utility in targeting the X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein (XIAP) for cancer therapy. Researchers generated a pharmacophore model from the XIAP protein complex (PDB: 5OQW) with a known inhibitor, identifying 14 distinct chemical features including four hydrophobic regions, three hydrogen bond acceptors, five hydrogen bond donors, and one positive ionizable feature [9]. The model was rigorously validated using ROC curve analysis, achieving an exceptional AUC value of 0.98 with an early enrichment factor (EF1%) of 10.0, confirming its superior ability to distinguish active compounds from decoys.

Virtual screening of natural compound libraries against this pharmacophore model identified seven promising hit compounds, with four advancing to molecular dynamics simulations. Three compounds—Caucasicoside A, Polygalaxanthone III, and MCULE-9896837409—demonstrated stable binding profiles, suggesting their potential as lead compounds for XIAP-related cancer treatment [9]. This case study exemplifies the power of structure-based pharmacophore approaches in identifying novel chemotypes from natural product space, particularly for challenging targets like XIAP where conventional drug discovery has been hampered by toxicity issues.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Research Reagent | Function in Workflow | Example Source/Format |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) Structures | Source of experimentally determined protein-ligand complexes for model generation | RCSB PDB (e.g., 5OQW, 2FSZ, 7XVZ) [9] [15] |

| scPDB Database | Curated database of binding sites for pharmacophore generation; contains over 41,000 entries | PharmaDB in Discovery Studio, updated based on scPDB 2024 [14] |

| ZINC Database | Commercially available compound library for virtual screening; contains >230 million compounds | 3D formatted compounds for pharmacophore screening [9] |

| DUDE/DUD-E Database | Benchmarking sets with property-matched decoy compounds for model validation | Enhanced Database of Useful Decoys [9] [16] |

| LigandScout Software | Advanced platform for structure-based pharmacophore modeling and validation | Integrated protocol in Discovery Studio [9] [15] |

Advanced Protocol: Shared Feature Pharmacophore Modeling for Mutant Proteins

Objective: To generate a consensus pharmacophore model capturing essential features across multiple mutant forms of a target protein.

Rationale: This approach is particularly valuable for drug targets exhibiting mutation-driven resistance, such as estrogen receptor beta (ESR2) in breast cancer.

Methodology:

Multiple Structure Compilation:

- Curate multiple PDB structures of mutant variants (e.g., for ESR2: 2FSZ, 7XVZ, 7XWR) [15].

- Prepare each structure using standard protein preparation protocols.

Individual Pharmacophore Generation:

- Generate structure-based pharmacophores for each mutant protein-ligand complex.

- Record feature types and distributions for each model.

Shared Feature Analysis:

- Employ the "Alignment" tool in LigandScout to identify conserved pharmacophore features across all mutant models.

- Generate a Shared Feature Pharmacophore (SFP) model containing features present across multiple variants.

Combinatorial Screening:

- For complex SFP models with numerous features (e.g., 11 features across multiple types), use combinatorial approaches to create multiple query combinations.

- Implement an in-house Python script to distribute features using permutation formulas (e.g., 336 combinations from 11 features) [15].

- Screen compound libraries against all combinations to maximize identification of potential hits.

Key Outcomes: Application of this protocol to ESR2 mutants identified a consensus model with 2 HBD, 3 HBA, 3 hydrophobic, 2 aromatic, and 1 halogen bond donor feature. Virtual screening followed by molecular dynamics identified ZINC05925939 as a promising lead compound with stable binding to wild-type ESR2 [15].

Integration with Modern Computational Workflows

Synergy with Molecular Docking and Dynamics

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling demonstrates remarkable synergy with other computational approaches, creating integrated workflows that enhance virtual screening efficiency. Pharmacophore models serve as excellent pre-filters for molecular docking, significantly reducing the number of compounds that require computationally intensive docking simulations [17]. Recent advancements include shape-focused pharmacophore models that combine the strengths of both approaches by comparing docking poses against cavity-filling negative images of the binding site [16].

The O-LAP algorithm represents a significant innovation in this space, generating pharmacophore models through graph clustering of docked ligand poses. This approach fills the target protein cavity with flexibly docked active ligands, clusters overlapping atoms, and creates models that outperform default docking enrichment in rigorous benchmarking [16]. Similarly, the integration of pharmacophore screening with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations enables thorough evaluation of binding stability, as demonstrated in both the XIAP and ESR2 case studies where MD simulations spanning 200 ns confirmed the stability of identified lead compounds [9] [15].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Structure-Based Pharmacophore Screening in Case Studies

| Study Target | Pharmacophore Features Identified | Validation Metrics | Virtual Screening Results | MD Simulation Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XIAP Protein [9] | 4 Hydrophobic, 3 HBA, 5 HBD, 1 Positive Ionizable | AUC: 0.98, EF1%: 10.0 | 7 initial hits from ZINC database | 3 compounds with stable binding |

| ESR2 Mutants [15] | 2 HBD, 3 HBA, 3 Hydrophobic, 2 Aromatic, 1 XBD | Fit score >86% for top compounds | 4 top hits satisfying Lipinski rules | 1 promising candidate (ZINC05925939) |

| Benchmark Targets [16] | Shape-focused models from docked poses | Improved enrichment vs default docking | Effective in both rescoring and rigid docking | High enrichment in DUDE-Z sets |

Advanced Visualization and Analysis Workflow

The analysis and prioritization of pharmacophore screening results requires sophisticated visualization and multi-parameter assessment to identify truly promising candidates.

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of structure-based pharmacophore modeling is rapidly evolving with several emerging trends shaping its future development. Artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches are being increasingly integrated, as exemplified by PharmacoForge—a diffusion model that generates 3D pharmacophores conditioned on protein pocket structures [17]. These AI-generated models demonstrate competitive performance with traditional methods while offering substantial improvements in generation speed and automation.

The growing emphasis on shape-focused pharmacophore models represents another significant trend. Traditional feature-based models are being supplemented with shape-based approaches that better capture the volumetric aspects of binding sites, leading to improved enrichment in virtual screening [16]. Furthermore, the development of ensemble pharmacophore methods addresses the challenge of protein flexibility by incorporating multiple receptor conformations, providing more comprehensive coverage of potential binding modes.

Recent updates in commercial platforms like BIOVIA Discovery Studio reflect these advancements, with the 2025 release introducing new protocols for antibody paratope prediction and enhanced support for mmCIF file formats that facilitate working with complex structural data [14]. As structural biology continues to generate increasingly complex data on protein-ligand interactions, structure-based pharmacophore modeling remains an essential tool for translating this structural information into actionable drug discovery insights.

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling has established itself as a cornerstone technique in modern computational drug discovery, providing an effective framework for virtual screening and lead optimization. Through integration with structural biology data and advanced computational methods, this approach continues to evolve, addressing increasingly complex challenges in drug discovery. The documented success in targeting proteins like XIAP and mutant ESR2, coupled with ongoing methodological innovations in AI-driven pharmacophore generation and shape-based modeling, ensures that structure-based pharmacophore approaches will remain essential tools in the effort to accelerate therapeutic development and address unmet medical needs.

Discovery Studio's Integrated Environment for Molecular Modeling and Simulation

BIOVIA Discovery Studio provides a comprehensive modeling and simulation suite that integrates over 30 years of peer-reviewed research and world-class in silico techniques into a unified environment for life sciences research [18]. This integrated platform enables researchers to explore biological and physicochemical processes at the atomic level, accelerating drug discovery and development from target identification through lead optimization [19]. For researchers focused on structure-based pharmacophore generation, Discovery Studio offers a seamless workflow that combines molecular dynamics simulations, binding site analysis, and pharmacophore modeling within a single, collaborative environment.

The software brings together specialized modules for simulations, structure-based design, and ligand-based approaches, all accessible through a user-friendly interface with robust visualization capabilities [18] [19]. This integration is particularly valuable for pharmacophore model generation, where understanding dynamic protein-ligand interactions and binding site flexibility significantly enhances model accuracy and biological relevance. The environment supports the entire research workflow—from protein preparation and dynamics simulations to pharmacophore generation and virtual screening—without requiring researchers to master multiple disconnected tools or manage complex data transfer between applications [20] [12].

Core Modules Supporting Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation

Simulations for Dynamic Binding Site Characterization

Molecular dynamics simulations within Discovery Studio provide critical insights into protein flexibility and binding site dynamics that directly inform pharmacophore model generation [20]. The platform utilizes best-in-class simulation programs including NAMD and CHARMm, with GPU acceleration for enhanced performance [20].

- Explicit Membrane Modeling: The Solvate with Explicit Membrane protocol enables researchers to simulate transmembrane proteins in physiologically relevant lipid bilayer environments, with recent enhancements improving equilibration reliability [21]. This is particularly crucial for generating accurate pharmacophore models for membrane-bound targets like GPCRs [22].

- Gaussian Accelerated MD (GaMD): This implementation allows for simultaneous unconstrained enhanced sampling and free energy calculations, helping researchers identify cryptic binding pockets and characterize protein flexibility relevant to pharmacophore feature placement [20].

- Trajectory Analysis: Built-in tools for analyzing MD trajectories enable researchers to identify conserved water molecules, map binding site flexibility, and determine stable interaction patterns that inform pharmacophore feature selection [20].

Table 1: Key Molecular Dynamics Simulation Capabilities

| Simulation Type | Application in Pharmacophore Generation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Explicit Solvent MD | Characterizes solvation effects on binding sites | Solvation with optional counterions; Water molecule tracking |

| GaMD Simulations | Identifies low-frequency binding site conformations | Enhanced sampling without constraints; Free energy calculations |

| Explicit Membrane MD | Models membrane protein binding sites accurately | Pre-equilibrated lipid bilayers; Transmembrane protein solvation |

| QM/MM Simulations | Provides electronic property details for feature modeling | DMol3/CHARMm hybrid; Electronic structure analysis |

Structure-Based Design Tools

The structure-based design module offers specialized tools for binding site analysis and protein-ligand interaction mapping that directly support pharmacophore feature identification [19].

- Binding Site Analysis: Tools for identifying critical residues with non-bond interaction monitors help characterize the chemical environment of binding pockets [19].

- Protein-Ligand Docking: Protocols like CDOCKER provide CHARMm-based docking with flexible ligand refinement, generating protein-ligand complexes that serve as input for structure-based pharmacophore generation [19].

- Fragment-Based Screening: Multiple Copy Simultaneous Search (MCSS) places functional group fragments into binding sites to identify favorable interaction points—a method directly applicable to pharmacophore feature selection [22].

Pharmacophore Modeling and Analysis

The Catalyst pharmacophore modeling toolkit within Discovery Studio supports comprehensive structure-based pharmacophore generation through multiple approaches [12] [4].

- Receptor-Based Pharmacophores: Automatically generate pharmacophores from receptor binding sites by analyzing interaction potentials and feature complementarity [12].

- Complex-Based Pharmacophores: Create pharmacophores from receptor-ligand complexes by extracting key interaction features from solved structures [12].

- Ensemble Pharmacophores: Go beyond classical limitations by exploring multiple binding modes and protein conformations to create comprehensive pharmacophore models that account for structural flexibility [12].

- Diverse Pharmacophore Generation: Recent enhancements include methods for generating diverse pharmacophore models, improving coverage of different binding modes and interaction patterns [23].

Integrated Workflow for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for structure-based pharmacophore generation in Discovery Studio, integrating multiple modules into a cohesive research pipeline:

Workflow Overview: This integrated process begins with protein preparation and proceeds through dynamics simulations, binding site analysis, and automated pharmacophore generation, culminating in validated models ready for virtual screening applications.

Protocol: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation from Dynamics-Informed Binding Sites

Protein System Preparation

- Protein Structure Input: Begin with an experimentally determined or modeled structure (recent releases support AlphaFold2 and OpenFold for predicted structures) [23]. Use the Prepare Protein protocol to add missing atoms, predict ionization states, and assign appropriate protonation states at physiological pH.

- System Solvation: Employ the Explicit Solvation protocol to solvate the protein in a water box with appropriate counterions to neutralize the system. For membrane proteins, use the Solvate with Explicit Membrane protocol with pre-equilibrated lipid bilayers [20].

- System Minimization: Perform energy minimization using the CHARMm force field (CGenFF or charmm36) to relieve steric clashes and optimize hydrogen bonding networks [20].

Molecular Dynamics for Binding Site Characterization

- System Equilibration: Run a multi-stage equilibration protocol gradually relaxing positional restraints on the protein to achieve stable system density and temperature.

- Production Dynamics: Execute production MD simulations using either CHARMm or NAMD engines, with GPU acceleration via OpenMM for improved performance [20]. For enhanced sampling of binding site conformations, implement Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD) protocols.

- Trajectory Analysis: Use the Measure Trajectory Features protocol to calculate RMSD, RMSF, and binding site volume fluctuations. Identify conserved water molecules and stable interaction grids within the binding site [21].

Pharmacophore Feature Identification and Model Generation

- Binding Site Analysis: Use the Binding Site analysis tool to characterize the chemical environment, identifying hydrophobic patches, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, and charged regions.

- Fragment Placement: Run Multiple Copy Simultaneous Search (MCSS) to place functional group fragments in the binding site, identifying energetically favorable positions for key chemical features [22].

- Feature Selection: Based on MCSS results and trajectory analysis, select critical interaction points for inclusion in the pharmacophore model. The Feature Mapping protocol automates identification of possible interaction features within the binding site [4].

- Model Generation: Use the Common Feature Pharmacophore Generation protocol to create multiple pharmacophore hypotheses from the selected features. The algorithm generates and ranks models based on feature consensus and geometric complementarity [4].

Protocol Validation and Selection Framework

Recent research has established rigorous methodologies for validating and selecting optimal structure-based pharmacophore models [22]:

- Enrichment Factor Calculation: Validate models by screening databases containing known active ligands and decoys. Calculate enrichment factors (EF) to quantify performance compared to random selection.

- Cluster-then-Predict Workflow: Implement machine learning-based selection using K-means clustering followed by logistic regression classification to identify pharmacophore models likely to yield higher enrichment values [22].

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate models using AUC (Area Under Curve) values from ROC analysis, with AUC >0.9 indicating excellent discriminatory power [9].

Table 2: Quantitative Validation Metrics for Pharmacophore Models

| Validation Metric | Calculation Method | Performance Standard | Application in Model Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | (Hitssampled / Nsampled) / (Hitstotal / Ntotal) | EF1% > 10 indicates strong enrichment [9] | Primary metric for virtual screening performance |

| Goodness of Hit (GH) | Combines yield of actives and false negative rate | GH approaching 1.0 indicates ideal performance [22] | Balanced metric considering multiple factors |

| Area Under Curve (AUC) | Integral of ROC curve | AUC > 0.9 indicates excellent model discrimination [9] | Overall model quality assessment |

| Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | TP / (TP + FP) | PPV of 0.76-0.88 for high enrichment models [22] | Machine learning classifier performance |

Research Reagent Solutions for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation

Table 3: Essential Research Tools in Discovery Studio for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Research Reagent | Function in Pharmacophore Generation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| CHARMm Force Field | Empirical potential for molecular mechanics calculations | Parameterization for proteins, lipids, small molecules; CHARMM36 and CGenFF support [19] |

| MCSS (Multiple Copy Simultaneous Search) | Fragment placement for interaction mapping | Places functional groups in binding site; Identifies favorable interaction positions [22] |

| CATALYST Pharmacophore Engine | Pharmacophore model generation and screening | Geometric feature-based queries; Shape similarity; "Forbidden" space definition [12] |

| PharmaDB Database | Pharmacophore screening and off-target profiling | ~240,000 receptor-ligand pharmacophore models; Validated using scPDB [12] |

| ZDOCK Algorithm | Protein-protein docking for interface analysis | FFT-based shape complementarity; Predicts binding interfaces [19] |

| DMol3 Module | Quantum mechanical calculations | Density functional theory; Electronic property calculation [19] |

| DELPHI Solver | Electrostatic property calculation | Poisson-Boltzmann equation solver; pKa prediction [19] |

Advanced Applications and Case Studies

GPCR-Targeted Pharmacophore Modeling

G protein-coupled receptors represent a particularly challenging class of drug targets due to their membrane-bound nature and frequent lack of known ligands [22]. Discovery Studio's integrated environment enables successful pharmacophore generation for GPCRs through:

- Homology Modeling: For GPCRs without experimental structures, the MODELER algorithm generates reliable homology models using the integrated comparative modeling workflow [19].

- Membrane-Embedded Simulations: The explicit membrane modeling capabilities create physiologically relevant environments for GPCR binding site characterization [20].

- Fragment-Based Pharmacophore Generation: The score-based selection method applied to MCSS-placed fragments generates high-performing pharmacophore models even without known active ligands [22].

In a comprehensive study across 30 Class A GPCRs, this approach produced pharmacophore models exhibiting high enrichment factors when screening databases containing 569 known GPCR ligands. The machine learning-based selection workflow achieved 82% true positive identification of high-enrichment structure-based pharmacophore models [22].

XIAP Antagonist Identification Case Study

A recent study targeting the XIAP protein demonstrates the power of the integrated Discovery Studio environment for identifying natural anti-cancer agents [9]:

- Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation: Researchers created a pharmacophore model from the XIAP protein active site complexed with a known inhibitor, identifying 14 chemical features including hydrophobic regions, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, and positive ionizable features [9].

- Model Validation: The pharmacophore model demonstrated exceptional discriminatory power with an AUC value of 0.98 and early enrichment factor (EF1%) of 10.0, confirming its ability to distinguish active compounds from decoys [9].

- Virtual Screening: Application of the validated model to natural compound databases identified several promising XIAP antagonists with potential anti-cancer activity [9].

The following diagram illustrates the key protein-ligand interactions captured in the XIAP pharmacophore model, demonstrating how structural informatics guides feature selection:

Pharmacophore Feature Mapping: The XIAP case study demonstrates how binding site analysis translates specific protein-ligand interactions into pharmacophore features including hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, positive ionizable groups, hydrophobic regions, and exclusion volumes.

Recent Advancements and Future Directions

The Discovery Studio environment continues to evolve with significant enhancements in recent releases:

- AI Integration: The 2024 release incorporated AlphaFold2 and OpenFold for protein structure prediction, alongside RFDiffusion and ProteinMPNN for protein design, enabling more accurate structure determination for targets without experimental structures [23].

- Enhanced Simulation Protocols: Recent updates improved explicit membrane modeling equilibration and fixed issues with production dynamics on NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPUs, increasing reliability for membrane protein simulations [21].

- Democratized Machine Learning: New capabilities allow researchers to build and share custom machine learning and 3D models across team members, facilitating collaborative pharmacophore model refinement [23].

The integration of these advanced AI and simulation technologies within the unified Discovery Studio environment promises to further enhance the accuracy and efficiency of structure-based pharmacophore generation, solidifying its position as an essential platform for modern drug discovery research.

Within the framework of structure-based pharmacophore generation, the initial steps of procuring and refining a protein structure are foundational. A pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [10]. Generating a reliable, structure-based pharmacophore model directly depends on the quality and biological relevance of the input protein structure [10]. This application note details the essential protocols within BIOVIA Discovery Studio for transitioning from a raw protein data bank (PDB) file to a fully prepared protein structure, ready for subsequent computational workflows such as pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, and virtual screening.

Core Principles: The Importance of Protein Preparation

Protein structures sourced from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) are experimental snapshots and are not immediately suitable for computational analysis. Using a raw PDB file can introduce significant errors, including distorted binding predictions, false positive docking poses, and a general waste of computational resources [24]. Proper preparation ensures the accurate modeling of molecular interactions by addressing common issues such as missing atoms, incorrect protonation states, and the presence of non-essential crystallographic components [10] [24]. This process is not merely a formality but the cornerstone of meaningful and reproducible in silico research [24].

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

The following protocol describes the standard workflow for protein preparation using BIOVIA Discovery Studio, ensuring the structure is optimized for structure-based pharmacophore generation.

Workflow Diagram

The logical flow of the protein preparation protocol is visualized below.

Detailed Methodologies

Step 1: Load Your Protein Structure

- Action: Within Discovery Studio, navigate to

File → Import → Molecule from PDB[24]. - Rationale: The initial acquisition of the protein structure.

- Protocol Note: It is critical to select a high-resolution structure related to your specific target. The quality of the input structure directly influences the quality of the final pharmacophore model [10] [24].

Step 2: Clean the Protein Structure

- Action: Utilize the "Clean Protein" tool in Discovery Studio [24].

- Rationale: To remove non-essential components that may interfere with subsequent calculations.

- Protocol Details:

- Removes unwanted water molecules, except those potentially involved in key interactions.

- Deletes extraneous ligands and heteroatoms not relevant to the study.

- Resolves alternate conformations of residues to a single, defined state [24].

- Output: A baseline cleaned protein structure.

Step 3: Prepare the Protein for Docking and Pharmacophore Modeling

- Action: Execute the "Prepare Protein" module [24].

- Rationale: To correct structural deficiencies and assign correct chemical properties.

- Protocol Details:

- Adds missing atoms and residues that are absent in the experimental structure.

- Correctly assigns bond orders for all atoms in the structure.

- Adds hydrogen atoms based on the specified physiological pH, which is crucial for correct protonation states of residues [24]. Discovery Studio includes tools for quick and accurate protein ionization and residue pK~a~ prediction for this purpose [20].

Step 4: Minimize the Structure (Optional but Recommended)

- Action: Use the "Minimize Energy" tool with the CHARMm force field [24].

- Rationale: To remove steric clashes and relieve residual structural strain introduced during the preparation steps.

- Protocol Details:

- Run a short, mild energy minimization.

- Critical Warning: Excessive minimization should be avoided to prevent significant deviation from the original, experimentally determined conformation [24].

Step 5: Define the Binding Site

- Action: Use binding site definition tools to specify the region of interest [24].

- Rationale: For structure-based pharmacophore generation, the model is built within the ligand-binding site [10].

- Protocol Details:

- From a Co-crystallized Ligand: If the PDB structure contains a bound ligand, the binding pocket can be defined directly from the ligand's location [24].

- From Prediction: If no ligand is present, use "Define and Edit Binding Site" or other bioinformatics tools (e.g., GRID, LUDI) to predict potential binding pockets based on geometric and energetic properties [10] [24].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential computational tools and their functions within the Discovery Studio environment for the protein preparation workflow.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Preparation in Discovery Studio

| Tool/Feature Name | Function in Protein Preparation |

|---|---|

| Clean Protein Tool | Removes water molecules, extraneous ligands, and heteroatoms; resolves alternate conformations [24]. |

| Prepare Protein Module | Adds missing atoms/residues, assigns correct bond orders, and adds hydrogen atoms appropriate for the target pH [24]. |

| CHARMm Force Field | An empirical force field used for energy minimization to remove steric clashes and for molecular dynamics simulations [20] [19]. |

| Binding Site Definition Tools | Defines or predicts the ligand-binding pocket, which is a prerequisite for structure-based pharmacophore modeling and docking [24]. |

| pK~a~ Prediction Tools | Accurately predicts protein ionization and residue pK~a~ values to ensure correct protonation states during protein preparation [20]. |

Data Presentation and Analysis Parameters

The table below summarizes the key quantitative parameters and decisions involved in the protein preparation protocol, serving as a quick-reference guide for researchers.

Table 2: Critical Parameters and Options for Protein Preparation

| Preparation Step | Key Parameters & Options | Recommendation / Default Value |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Selection | PDB Resolution | Prefer higher resolution (e.g., < 2.5 Å) structures [24]. |

| Protein Cleaning | Water Removal | Remove all but functionally critical water molecules [24]. |

| Protein Preparation | pH for Protonation | Set to physiological pH (e.g., 7.4) unless specified otherwise [24]. |

| Energy Minimization | Force Field | CHARMm [20] [24]. |

| Energy Minimization | Algorithm & Steps | Use a mild minimization protocol to retain crystal structure integrity [24]. |

| Binding Site | Definition Method | From co-crystallized ligand (preferred) or computational prediction [10] [24]. |

A meticulous and systematic approach to protein structure retrieval and preparation is an indispensable prerequisite for successful structure-based pharmacophore generation. The protocols outlined herein, when executed using the robust tools within BIOVIA Discovery Studio, provide a reliable foundation for subsequent computational drug discovery efforts. A well-prepared protein structure ensures that the derived pharmacophore model—a spatial arrangement of features like hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and ionizable groups—accurately reflects the true interaction potential of the biological target [10]. This, in turn, increases the likelihood of identifying valid hit compounds through virtual screening, thereby accelerating the drug discovery pipeline.

A Step-by-Step Workflow: Building and Applying Pharmacophore Models in Discovery Studio

Within the framework of structure-based pharmacophore modeling, the initial preparation and validation of the protein-ligand complex is a critical foundational step. The accuracy and reliability of subsequent pharmacophore generation, virtual screening, and lead optimization in BIOVIA Discovery Studio are entirely contingent upon the structural and energetic soundness of this initial input complex [12]. This protocol details a comprehensive procedure for preparing and validating a protein-ligand complex using Discovery Studio 2025, ensuring the system is optimally configured for robust pharmacophore model generation [14].

Current Software Capabilities: Discovery Studio 2025

The 2025 release of BIOVIA Discovery Studio introduces several enhancements that directly improve the accuracy and efficiency of complex preparation. Key updates relevant to this protocol include:

- Advanced File Handling: Improved support for reading mmCIF file formats, including correct interpretation of biological assemblies and chemical component definitions (CCD), ensuring ligand bond orders and formal charges are assigned correctly from the outset [14].

- Enhanced Force Fields: Updates to underlying libraries and force fields, such as the MODELLER update to version 10.5, provide more accurate homology modeling and loop refinement for structures with missing residues [14].

- Performance Optimizations: GPU-resident mode for Dynamics (NAMD) protocols and the ability to handle systems with up to 1 million atoms in CHARMm enable the study of larger, more complex biological systems [14].

Experimental Protocol

Protein Preparation and Minimization

The following steps ensure the protein structure is structurally sound and ready for complex formation [25].

- Protein Selection and Import: Download the crystal structure of your target protein (e.g., PDB: 6M0J) from the RCSB Protein Data Bank. Import the structure into Discovery Studio.

- Initial Preparation: Execute the "Prepare Protein" protocol. This step automatically inserts missing loops, adds missing atoms, and standardizes residue names.

- Protonation: Apply the "Protonation" step to assign hydrogen atoms appropriate for physiological pH (pH 7.4). This step is crucial for correctly modeling hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions in the pharmacophore.

- Protein Minimization: Subject the prepared protein to a multi-stage energy minimization to relieve steric clashes and geometric strain using the CHARMm force field [20].

- Solvation: Solvate the protein with an explicit water model (e.g., TIP3P) using an explicit periodic boundary condition. Add counterions to neutralize the system's charge.

- Minimization Steps:

- Step 1: Fix the protein backbone and side chains, allowing only water molecules and hydrogen atoms to move. Use the Smart Minimizer algorithm, initiating with the Steepest Descent method until a gradient RMS of 3 is reached, followed by the Conjugate Gradient method.

- Step 2: Fix the protein backbone, allowing side chains, water, and hydrogens to move using the same Smart Minimizer protocol.

- Step 3: Allow the entire system to move without restrictions, applying the Smart Minimizer protocol to achieve a final energy-minimized structure.

- Desolvation: Remove water molecules and ions from the minimized system to obtain the prepared protein for docking or complex analysis.

Ligand Preparation

Concurrently, the small molecule ligand must be prepared to explore its relevant conformational and ionization states [25] [12].

- Ligand Input: Draw the ligand structure using ChemDraw or import a ligand structure from a database (e.g., scPDB, ZINC) in SDF or MOL2 format.

- Ligand Preparation Protocol: Use the "Ligand Preparation" protocol in Discovery Studio.

- Ionization and Tautomers: Set the ionization to generate possible states within a physiological pH range (e.g., 6.5–8.5). Generate canonical tautomers to ensure comprehensive chemical space coverage.

- Isomer Generation: For ligands with undefined stereochemistry, generate isomers for all chiral atoms. The molecular modeling in subsequent steps will identify the optimal isomer for binding.

Active Site Definition and Docking (If Applicable)

For structures where a ligand is not already co-crystallized, docking is required to generate a complex.

- Define Active Site: Based on the crystallographic ligand or known binding site residues, define the spherical docking region. The sphere should be large enough (e.g., 9.9–10 Å radius) to allow ligand flexibility [25].

- Perform Docking: Utilize a docking protocol such as CDOCKER [20] or Dock Ligands (GOLD) [14] to generate plausible binding poses.

- Pose Selection: Select the top-ranked pose based on a combination of docking scores, interaction analysis with key binding site residues, and visual inspection.

Complex Validation

Before proceeding to pharmacophore generation, validate the prepared complex.

- Structural Inspection: Visually inspect the complex for reasonable binding geometry, absence of severe steric clashes, and formation of key interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, pi-pi stacking).

- Energetic Plausibility: For critical complexes, consider running a short molecular dynamics (MD) simulation using the "Dynamics (NAMD)" protocol [14] [20] to assess the stability of the ligand pose and the complex.

Key Enhancements and Fixed Defects in Discovery Studio 2025

Table 1: Recent enhancements in BIOVIA Discovery Studio 2025 relevant to complex preparation and validation.

| Component | Enhancement | Benefit for Complex Preparation |

|---|---|---|

| File Format Support | Enhanced mmCIF reading; biological assemblies correctly named; missing residue info read [14]. | Improved handling of modern PDB entries and more accurate initial model building. |

| Ligand Chemistry | PDB Ligand Bond Orders script upgraded to use CCD files for all ligands from RCSB PDB [14]. | Correct assignment of bond orders and formal charges, critical for accurate electrostatics. |

| Force Field & Methods | MODELLER updated to v10.5; Solvate with Explicit Membrane protocol updated for better equilibration [14]. | More reliable homology models and membrane system preparation. |

| Performance | CHARMm can handle systems with up to 1 million atoms [14]. | Enables preparation and simulation of very large molecular systems. |

Table 2: Selected fixed defects in BIOVIA Discovery Studio 2025 improving reliability.

| Defect ID | Issue Fixed | Impact on Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| DSC-37615 | Simulation Time parameter can now exceed 200 ns in Dynamics protocols [14]. | Allows for longer, more biologically relevant simulation times. |

| DSC-37212 | Prepare Protein protocol no longer fails for inputs with >99999 atoms [14]. | Robust preparation of very large systems, such as multi-protein complexes. |

| DSC-38126 | Inserting a structure from mmCIF no longer creates spurious intermolecular bonds [14]. | Prevents introduction of artifacts during file import. |

Visualized Workflow

Below is a flowchart depicting the logical sequence of the protein-ligand complex preparation and validation protocol.

Workflow for Protein-Ligand Complex Preparation and Validation

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions and software resources for complex preparation.

| Resource / Reagent | Function / Description | Source / Example |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids. | PDB ID: 6M0J (SARS-CoV-2 Spike RBD with ACE2) [25] |

| BIOVIA Discovery Studio | Integrated environment for protein preparation, simulation, and pharmacophore modeling. | BIOVIA Discovery Studio 2025 [14] |

| CHARMm Force Field | A widely used empirical energy function for molecular mechanics and dynamics simulations. | Integrated in Discovery Studio for minimization and MD [20] |

| scPDB / PharmaDB | A curated database of binding sites and pharmacophores derived from the PDB. | Contains >41,000 entries for pharmacophore-based screening [14] |

| ZINC Database | A freely available database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. | Source for natural compounds and drug-like molecules [26] |

| PyMOL / DS Visualizer | Molecular visualization tools for analyzing and rendering prepared structures and complexes. | Used for interaction analysis and figure generation [27] |

Automated pharmacophore feature generation and mapping represents a pivotal phase in structure-based drug design, transforming complex structural data into actionable, three-dimensional chemical interaction models. Within BIOVIA Discovery Studio, this process leverages sophisticated algorithms to systematically detect and map critical interaction features directly from protein-ligand complexes or binding sites, providing researchers with powerful hypotheses for virtual screening and lead optimization [12]. This Application Note details the practical implementation of automated pharmacophore generation protocols within Discovery Studio, specifically focusing on the Receptor-Ligand Complex (E-Pharmacophore) and Annotate Binding Site workflows available to researchers.

The fundamental strength of automated pharmacophore generation lies in its ability to objectively identify essential molecular interactions—including hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, charged centers, and exclusion volumes—while reducing subjective bias inherent in manual model development [28]. With the recent 2025 release of Discovery Studio incorporating enhanced pharmacophore capabilities and improved performance, researchers now have access to even more robust tools for accelerating drug discovery pipelines [14].

Core Capabilities of Automated Pharmacophore Generation in Discovery Studio