Strategies to Minimize False Positives in qPCR Cancer Assays: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Validation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on mitigating false positive results in quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays for cancer detection and monitoring.

Strategies to Minimize False Positives in qPCR Cancer Assays: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on mitigating false positive results in quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays for cancer detection and monitoring. It covers the foundational sources of error, methodological best practices in assay design and wet-lab procedures, systematic troubleshooting and optimization protocols, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing current research and proven techniques, this resource aims to enhance the specificity, reliability, and clinical applicability of qPCR-based cancer diagnostics, ultimately supporting the development of more accurate and trustworthy biomarker assays.

Understanding the Sources and Impact of False Positives in Cancer qPCR

In the realm of molecular oncology, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) stands as a cornerstone technology for detecting cancer biomarkers, monitoring minimal residual disease, and guiding targeted therapy decisions. However, the clinical consequences of false positive results can be profound, leading to inappropriate treatment selections, unnecessary psychological distress for patients, and increased healthcare costs. A false positive result occurs when a qPCR assay incorrectly indicates the presence of a specific cancer-associated mutation or biomarker. In non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), for example, a recent study on EGFR S768I mutation detection revealed an 80% false positive rate when using a commercial qPCR system, with only one of five positive results confirmed by next-generation sequencing (NGS) [1]. Such inaccuracies in molecular diagnosis can directly impact therapeutic decisions, potentially steering patients toward ineffective or even harmful treatments.

The remarkably high sensitivity of qPCR, while advantageous for detecting low-abundance targets, also makes these assays particularly vulnerable to contamination and amplification artifacts [2]. In cancer diagnostics, where results directly influence treatment pathways, ensuring specificity is not merely an analytical concern but an ethical imperative. This technical support center provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with evidence-based troubleshooting guides and FAQs to identify, prevent, and mitigate false positives in qPCR-based cancer assays, framed within the broader context of advancing precision oncology through more reliable molecular diagnostics.

FAQs: Understanding False Positives in Cancer qPCR

What are the primary sources of false positives in qPCR cancer assays?

False positives in qPCR cancer assays predominantly originate from three sources:

- Carryover contamination: Previously amplified PCR products (amplicons) from positive samples or controls can contaminate new reactions, generating false signals. This is particularly problematic in high-throughput laboratories processing numerous cancer samples daily [2] [3].

- Cross-contamination during sample processing: Aerosols created during pipetting, vortexing, or tube opening can transfer target nucleic acids between samples. In one documented case, false positives for Lyme disease led to inappropriate antibiotic therapy and subsequent patient complications [2].

- Assay design issues: Poorly designed primers and probes may bind nonspecifically to non-target sequences or form dimers that generate amplification signals. For instance, the use of primers targeting sequences only 25 bases long was postulated as a reason for false positives in SARS-CoV-2 rRT-PCR kits [2].

What are the clinical consequences of false positives in cancer diagnosis and treatment monitoring?

False positives in cancer qPCR assays can lead to several serious clinical outcomes:

- Inappropriate treatment selection: In NSCLC, false identification of EGFR mutations could lead to unnecessary tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) therapy instead of more appropriate treatments, exposing patients to potential side effects without clinical benefit [1].

- Unnecessary additional testing and procedures: False positives may trigger additional invasive biopsies, imaging studies, or laboratory tests that increase patient risk and healthcare costs [2].

- Psychological distress: Patients and families experience unnecessary anxiety and stress when incorrectly informed about cancer diagnosis or disease progression [2].

- Delayed correct diagnosis: Time and resources spent pursuing false leads can delay identification of the actual molecular drivers of a patient's cancer, potentially compromising outcomes.

How can we validate the specificity of a new qPCR assay for cancer biomarker detection?

Assay validation should incorporate multiple strategies:

- In silico specificity checks: Regularly verify primer and probe sequences via BLAST search against databases like NCBI to ensure specificity and minimize cross-reactivity with non-target sequences [2].

- Experimental controls: Include no-template controls (NTCs) to detect contamination and non-specific template controls to identify primer-dimer formation or non-specific amplification [3].

- Comparison with orthogonal methods: Confirm positive results using alternative technologies such as next-generation sequencing (NGS), especially for rare mutations like EGFR S768I where qPCR systems have demonstrated high false positive rates [1].

- Dilution series analysis: Evaluate assay performance across a range of target concentrations to establish limits of detection and identify potential low-level contamination issues [4].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Common Causes of False Positives

Problem: Consistent False Positives Across Multiple Samples

Potential Cause: Environmental contamination of laboratory equipment, reagents, or workspace with amplicons or positive control material.

Solutions:

- Implement physical separation: Establish distinct pre-PCR and post-PCR areas with unidirectional workflow to prevent amplicon carryover [2].

- Enhance decontamination protocols: Clean workspaces and equipment with 10% sodium hypochlorite (minimum 10 minutes contact time) followed by 70% ethanol or 1M hydrogen chloride. Use UV irradiation for surface sterilization [2] [3].

- Utilize enzymatic prevention: Incorporate uracil-DNA-glycosylase (UNG) into PCR master mixes to degrade contaminating uracil-containing amplicons from previous reactions [2] [3].

- Service equipment: Regularly clean and service pipettes, especially their interiors, which can become contaminated through improper pipetting techniques [2].

Problem: False Positives for Specific Targets Despite Proper Controls

Potential Cause: Non-specific primer binding or probe degradation leading to aberrant amplification signals.

Solutions:

- Redesign suboptimal primers: Implement "hot start" PCR techniques that inhibit polymerase activity until high temperatures are reached, reducing nonspecific amplification during reaction setup [2].

- Apply touchdown PCR: Begin with an annealing temperature 5°C-10°C above the primer's estimated melting temperature, then gradually decrease to the optimal temperature over subsequent cycles to favor specific binding [2].

- Verify probe integrity: Use signal-to-noise assessment, mass spectrometry, or fluorometric scans to check for degraded probes that release signal molecules and cause high background noise [2].

- Optimize primer design: Create longer primers (targeting >100 base pairs when possible) with annealing-control primers containing polydeoxyinosine linkers that form bubble structures during annealing to prevent nonspecific binding [2].

Problem: Inconsistent False Positives with Low Signal Intensity

Potential Cause: Low-level contamination from synthetic control materials or plasmid DNA used as positive controls.

Solutions:

- Use chimeric plasmid DNA (cpDNA): Implement cpDNA with contamination indicator probes that emit distinct fluorescent signals, enabling differentiation between true target amplification and control contamination [4].

- Dilute positive controls: Prepare single-use aliquots of control materials at appropriate concentrations to minimize contamination risk [2].

- Implement dual-probe systems: Develop assays with separate probes for the target sequence and an exogenous control sequence to distinguish specific amplification from contamination [4].

Case Study: Troubleshooting EGFR S768I False Positives in NSCLC

A recent prospective study evaluating EGFR S768I mutation detection in NSCLC patients demonstrated the real-world impact of false positives and their resolution. When using the Idylla qPCR system, initial testing showed an 80% false positive rate, with only one of five positive results confirmed by NGS. The troubleshooting process revealed:

- Amplification curve analysis: False positives typically showed normalized fluorescence values below 12 points, distinguishing them from true positives [1].

- Repeat testing methodology: When initial tissue testing (Idylla1) produced false positives, repeat analysis using extracted DNA (Idylla2) showed significantly improved accuracy (0.833 vs. 0.333) and better agreement with NGS (Kappa = 0.571 vs. 0.077) [1].

- Algorithm refinement: The findings suggested a need to refine the system's interpretation algorithms, particularly for mutations with lower prevalence like S768I [1].

Experimental Protocols for False Positive Mitigation

Protocol: Establishing a Contamination-Free qPCR Workflow for Cancer Assays

This protocol implements stringent measures to prevent false positives in high-sensitivity cancer detection assays.

Materials Needed:

- Dedicated pre-PCR and post-PCR workspaces

- Aerosol-barrier pipette tips

- UNG-containing master mix

- Freshly prepared 10% sodium hypochlorite solution

- 70% ethanol solution

- UV irradiation cabinet

- Dedicated lab coats and gloves for each area

- Single-use reagent aliquots

Procedure:

- Spatial Separation: Perform reagent preparation, sample addition, amplification, and analysis in physically separated areas with unidirectional workflow [2].

- Pre-PCR Area Setup:

- Reagent Preparation:

- Control Implementation:

- Personal Protective Measures:

Protocol: Specificity Validation for Novel Cancer Biomarker Assays

This protocol ensures that newly developed qPCR assays for cancer biomarkers maintain high specificity against genomic backgrounds.

Materials Needed:

- Target-positive samples (cell lines or patient samples with known mutation status)

- Target-negative samples (cell lines or patient samples confirmed wild-type)

- Genomic DNA from various tissue sources

- NGS confirmation capability

- Standard qPCR equipment and reagents

Procedure:

- Analytical Specificity Testing:

- Test the assay against a panel of genomic DNA from different tissue types to check for tissue-specific non-specific amplification.

- Include samples with phylogenetically related sequences or highly homologous genes to assess cross-reactivity.

- Limit of Detection (LOD) Determination:

- Perform serial dilutions of positive control material in wild-type background.

- Identify the lowest concentration at which the target is detected in ≥95% of replicates [1].

- Comparison with Orthogonal Methods:

- Analyze a set of clinical samples (minimum 20-30) by both the new qPCR assay and an established reference method like NGS.

- Calculate sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy with 95% confidence intervals [1].

- Amplification Curve Analysis:

- Carefully examine amplification curves for atypical shapes that might indicate non-specific amplification.

- Establish normalized fluorescence thresholds to distinguish true positives from false signals, as demonstrated in the EGFR S768I study where false positives typically showed values below 12 points [1].

- Blinded Testing:

- Conduct blinded testing of known positive and negative samples by multiple operators to assess reproducibility and identify operator-dependent contamination issues.

Data Presentation: Quantitative Analysis of False Positive Rates in Cancer qPCR

Table 1: Performance Metrics of EGFR S768I Mutation Detection by qPCR Versus NGS [1]

| Test Method | Sample Type | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Accuracy | False Positive Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Idylla1 (initial tissue testing) | FFPE tissue | 100 | 20 | 0.333 | 80 |

| Idylla2 (extracted DNA testing) | Extracted DNA | 100 | 80 | 0.833 | 20 |

| NGS (reference standard) | FFPE tissue | 100 | 100 | 1.000 | 0 |

Table 2: Comparison of Contamination Prevention Methods in qPCR [2] [3]

| Method | Mode of Action | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| UNG/UDG Treatment | Enzymatic hydrolysis of uracil-containing DNA from previous amplifications | Easy to incorporate into existing protocols; effective against most common contamination | Added cost; may reduce amplification efficiency if not optimized |

| UV Irradiation | Forms thymidine dimers in contaminating DNA | Inexpensive; requires no change to PCR protocol | Ineffective against GC-rich and short (<300 bp) amplification products |

| Spatial Separation | Physical isolation of pre-and post-PCR activities | Highly effective when properly implemented; no chemical modifications needed | Requires significant laboratory space and workflow discipline |

| Psoralen Treatment | Forms cyclobutane adducts with DNA | Relatively inexpensive; requires minor protocol modification | Potential carcinogenicity; less effective for GC-rich amplicons |

| Hydroxylamine Treatment | Chemically modifies cytosine residues to prevent C-G pairing | Effective on short and GC-rich amplicons | Carcinogenic; may interfere with downstream analysis |

Table 3: Diagnostic Accuracy of Molecular Tests Compared to RT-PCR Reference Standard [5]

| Test Type | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Positive Predictive Value (95% CI) | Negative Predictive Value (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid Antigen Tests (pooled) | 67.1% | Not reported | 97.7% | 95.2% |

| STANDARD Q COVID-19 Ag Test | 78.2% (58.7-90.0%) | 98.4% (94.9-99.5%) | Not reported | Not reported |

| PanBio COVID-19 Ag Test | 78.0% (61.0-88.9%) | 99.9% (99.3-100%) | Not reported | Not reported |

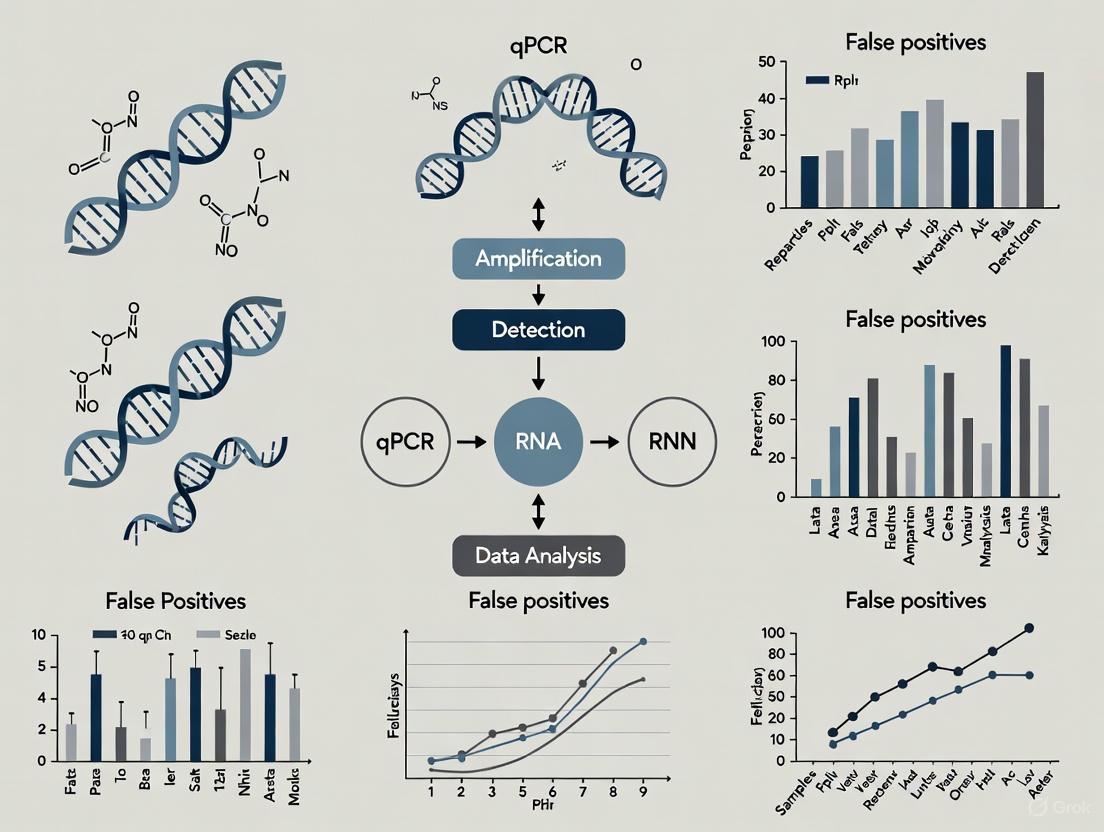

Visualization: Experimental Workflows and Diagnostic Pathways

Diagram 1: Comprehensive qPCR workflow and false positive investigation pathway illustrating the integrated approach required for reliable cancer diagnostics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Controls for Reliable Cancer qPCR

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for False Positive Mitigation

| Reagent/Control | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| UNG/UDG Enzyme | Degrades uracil-containing contaminating amplicons from previous reactions | Include in master mix with dUTP-containing nucleotides; incubate at 50°C for 2 minutes before amplification [2] [3] |

| No-Template Control (NTC) | Detects contamination in reagents or environment | Contains all reaction components except template nucleic acid; should always yield negative result [3] |

| Chimeric Plasmid DNA (cpDNA) | Positive control with contamination indicator | Contains target sequence plus exogenous sequence with separate probe; distinguishes true amplification from control contamination [4] |

| Annealing-Control Primers | Improve specificity through structural design | Incorporate polydeoxyinosine linkers that form bubble structures during annealing to prevent nonspecific binding [2] |

| Inhibition-Resistant Master Mixes | Reduce false positives from non-specific amplification | Formulations optimized with additives that increase specificity, especially for challenging templates [3] |

| SPUD Assay | Internal positive control for reaction inhibition | Amplification of specific non-target sequence confirms reaction efficiency; abnormal Cq indicates inhibition [3] |

In qPCR cancer assays, the reliability of your results is paramount. False positives can lead to incorrect data interpretation, wasted resources, and potentially affect downstream clinical decisions. The high sensitivity of qPCR makes it exceptionally vulnerable to contamination, which often manifests as amplification in No Template Controls (NTCs) [6] [3]. This guide details the major contamination sources and provides proven strategies to identify, prevent, and eliminate them, safeguarding the integrity of your research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common signs of contamination in my qPCR assay? The most direct indicator is amplification in your No Template Control (NTC) [6] [7]. Other red flags include an unexpected spike in positive results, particularly in a low-prevalence setting, or multiple samples with high Ct values clustering together on the plate [8].

2. How can I tell if my reagents are contaminated? If a contamination event affects a master mix or other shared reagent, you will typically see amplification in every NTC well containing that reagent, with similar Ct values across the wells [6]. Systematic testing of reagents and replacing suspected stocks is necessary in this case.

3. Why is amplicon carryover such a significant problem? Amplicons (the amplified PCR products) are present in extremely high concentrations following amplification. These products can aerosolize and contaminate laboratory environments, reagents, and equipment. Because they are perfect templates for the assay, even minute quantities can lead to robust false-positive signals [9] [10].

4. What is the single most effective practice to prevent contamination? Physical separation of pre- and post-amplification areas is the cornerstone of contamination prevention [6] [10]. Maintaining a unidirectional workflow—from reagent preparation to sample preparation to amplification and analysis—ensures that amplified products never re-enter clean areas where future reactions are set up [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Identifying and Addressing Amplicon Carryover Contamination

Amplicon carryover, where PCR products from previous reactions contaminate new setups, is a primary source of false positives [9].

- Symptoms: Amplification in NTCs. A sudden, plate-wide increase in false positives.

- Primary Sources: Aerosols generated when opening tubes containing amplified products; contaminated pipettes or equipment used in both post- and pre-PCR areas.

Prevention and Control Strategies

- Laboratory Design: Implement a unidirectional workflow through physically separated rooms or dedicated areas for:

- Procedural Methods:

- Biochemical Methods:

- Uracil-N-Glycosylase (UNG): Use master mixes containing UNG and incorporate dUTP in your PCR reactions. UNG enzymatically degrades any uracil-containing carryover amplicons before thermal cycling begins, but it is inactivated at high temperatures and does not affect the new, natural-template DNA [6] [3] [2].

The following diagram illustrates the critical workflow designed to prevent amplicon carryover.

Guide 2: Managing Sample Cross-Contamination and Environmental Contaminants

This form of contamination involves the transfer of template between samples or the introduction of external DNA into reactions.

- Symptoms: Random positive results in NTCs with varying Ct values [6]; inconsistent results between sample replicates.

- Primary Sources: Contaminated gloves, lab coats, or surfaces; aerosol generation during pipetting, vortexing, or centrifugation; contaminated reagents or enzymes [3] [2].

Prevention and Control Strategies

- Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and Technique:

- Surface and Equipment Decontamination:

- Regularly clean work surfaces, pipettes, and equipment with 10% bleach (sodium hypochlorite), allowing 10-15 minutes of contact time before wiping with de-ionized water or ethanol [6] [10]. Bleach chemically degrades DNA.

- Use UV irradiation in biosafety cabinets and on work surfaces to cross-link any contaminating DNA [10] [9].

- Reagent and Sample Management:

Guide 3: Systematic Decontamination and Validation Protocol

If contamination is suspected or confirmed, a rigorous decontamination process must be followed.

- Discard and Replace: Immediately discard all suspect reagents, including water, master mix, and primers [11].

- Deep Clean: Thoroughly decontaminate all work surfaces, equipment (especially pipettes), and racks with 10% bleach followed by 70% ethanol [10] [2].

- UV Irradiation: Expose pipettes, centrifuges, and biosafety cabinets to UV light for an extended period (e.g., overnight) [10].

- Validate: Before running patient or valuable samples, validate the clean environment by setting up multiple NTCs with fresh reagents. No amplification should be observed in the NTCs after a full qPCR run [6] [3].

Key Experimental Controls and Their Interpretation

Including the correct controls in every qPCR run is non-negotiable for detecting contamination and ensuring assay validity. The table below summarizes essential controls.

Table 1: Essential qPCR Controls for Contamination Monitoring

| Control Type | Composition | Expected Result | Interpretation of a Positive Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| No Template Control (NTC) [6] [3] | All reaction components except the nucleic acid template. | Negative (No amplification). | Indicates contamination in one of the reagents, primers, or the environment. |

| No Reverse Transcription Control (-RT) [3] [11] | RNA sample processed without the reverse transcriptase enzyme. | Negative. | Detects amplification from contaminating genomic DNA in RNA-based assays (RT-qPCR). |

| Positive Control | A known sample containing the target sequence. | Positive (Amplification at expected Ct). | Validates that the assay is functioning correctly. A negative result indicates assay failure. |

Research Reagent Solutions for Contamination Control

The following table lists key reagents and materials that are essential for implementing an effective contamination control strategy.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Contamination Control

| Item | Function | Considerations for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Aerosol-Resistant Filter Tips [9] | Prevents aerosols from contaminating the pipette shaft and subsequent samples. | Use for all liquid handling in pre-PCR areas. Do not autoclave. |

| Uracil-N-Glycosylase (UNG) [6] [9] | Enzymatically destroys carryover contamination from previous uracil-containing amplicons. | Requires the use of dUTP in the PCR reaction mix. Most effective for thymine-rich amplicons. |

| dUTP [6] | A nucleotide analog that incorporates into amplicons, making them susceptible to UNG degradation. | Used in place of dTTP in the PCR master mix. |

| Sodium Hypochlorite (Bleach) [6] [10] | Effective chemical decontaminant that degrades DNA on surfaces and equipment. | Use a freshly diluted 10% solution. Allow 10-15 minutes contact time. |

| DNase I [11] | Enzyme that degrades contaminating DNA in RNA samples. | Critical for RT-qPCR; use prior to the reverse transcription step. |

| Highly Purified Oligonucleotides | Primers and probes synthesized under controlled conditions. | Reduces risk of oligonucleotides being contaminated with template DNA during manufacturing [3]. |

Vigilance against contamination is a continuous requirement in any qPCR laboratory, especially in sensitive cancer research applications. By understanding the major sources—amplicon carryover, sample cross-contamination, and environmental contaminants—you can implement a robust defense-in-depth strategy. This combines rigorous laboratory practices, physical separation of workflows, systematic use of controls, and targeted biochemical methods. Adherence to these protocols will significantly reduce false positives, thereby enhancing the accuracy, reliability, and translational potential of your qPCR cancer assays.

In quantitative PCR (qPCR) research, particularly in the high-stakes field of cancer diagnostics, the fidelity of your signal is paramount. False positives can lead to incorrect data interpretation, misdiagnosis, and flawed scientific conclusions. A significant source of this error stems from fundamental assay design flaws, primarily concerning primer specificity and amplicon characteristics. This guide addresses these critical issues through targeted troubleshooting and frequently asked questions, providing a framework for developing robust, reliable qPCR cancer assays.

Primer Design and Specificity

What are the fundamental principles of robust qPCR primer design?

Adherence to established design parameters is the first defense against false positives. The table below summarizes the core criteria for robust primers.

Table 1: Key Criteria for qPCR Primer Design

| Parameter | Optimal Value/Range | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Primer Length | 18–30 bases [12] | Balances specificity and binding efficiency. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 60–64°C [12] | Ideal for standard enzyme function; forward and reverse primer Tms should not differ by more than 2°C. |

| GC Content | 35–65% (ideal: 50%) [12] | Provides sufficient sequence complexity while avoiding stable secondary structures. |

| 3'-End Complementarity | Avoid >2 complementary bases, especially GC [13] [14] | Greatly reduces the potential for primer-dimer formation. |

| Secondary Structures | ΔG of hairpins/self-dimers > -9.0 kcal/mol [12] | Ensures primers remain available for binding to the template rather than themselves. |

Beyond these rules, always verify primer specificity using tools like NCBI BLAST to ensure they are unique to your intended target [12]. Remember that the optimal annealing temperature (Ta) must be determined empirically, as it is influenced by your specific reaction buffer and master mix [13].

How do primer dimers lead to false positives, and how can I prevent them?

Primer dimers are small, unintended DNA fragments formed when primers anneal to each other instead of the target DNA. During qPCR, fluorescent dyes like SYBR Green bind to this double-stranded DNA, producing a false signal that can be mistaken for true target amplification, especially at low template concentrations or high cycle thresholds [14] [15].

Prevention Strategies:

- Design with Low 3' Complementarity: Use primer design tools to avoid primers that can base-pair with each other at their 3' ends [14].

- Optimize Reaction Conditions: Lower primer concentrations or increase template concentration to improve the primer-to-template ratio [14].

- Apply Hot-Start DNA Polymerase: These enzymes are inactive until a high-temperature activation step, minimizing nonspecific amplification during reaction setup [14].

- Increase Annealing Temperature: A higher Ta reduces the likelihood of primers binding nonspecifically to each other or to off-target sites [14].

Amplicon Characteristics and Validation

What amplicon features are critical for signal fidelity?

The amplicon—the DNA fragment amplified by PCR—is at the heart of your assay. Its characteristics directly influence specificity and efficiency.

Table 2: Optimal Amplicon Characteristics for qPCR Assays

| Characteristic | Recommendation | Impact on Assay |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 70–150 bp [12] | Shorter fragments amplify with higher efficiency and are ideal for standard cycling conditions. |

| Location | Span an exon-exon junction [12] | Prevents amplification of genomic DNA contamination, a major source of false positives. |

| Uniqueness | Unique in the genome; check for pseudogenes [13] | Ensures amplification is specific to the intended transcript or genetic locus. |

| Secondary Structure | Avoid regions with high stability at primer binding sites [13] | Allows primers to bind efficiently to the template, preventing delayed amplification or failure. |

Why is a melt curve analysis non-negotiable for SYBR Green assays, and how do I troubleshoot it?

SYBR Green dye binds to any double-stranded DNA, including non-specific products and primer dimers. Melt curve analysis is the primary quality control step to verify that the fluorescence signal originates from a single, specific amplicon [15]. After amplification, the temperature is gradually increased while fluorescence is measured. A single, sharp peak typically indicates a single, specific product. Multiple peaks, broad peaks, or peaks at unexpected temperatures indicate problems [16] [15].

Table 3: Troubleshooting Common Melt Curve Anomalies

| Melt Curve Appearance | Likely Cause | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Single peak, but Tm < 80°C | Primer dimer formation with no true product [16]. | Redesign primers; check primer specificity. |

| Double peaks; minor peak < 80°C | Primer dimers or short nonspecific products [16]. | Increase annealing temperature; lower primer concentration; increase template amount. |

| Double peaks; minor peak > 80°C | Non-specific amplification [16]. | Increase annealing temperature; check and remove genomic DNA contamination. |

| Irregular or noisy peaks | Template contamination or instrument issues [16]. | Prepare fresh, high-quality template; perform instrument maintenance. |

| Single peak, but not sharp | Broad peaks can be related to reagent composition or instrument sensitivity. If the temperature range is ≤ 7°C, the result is often still usable [16]. | If problematic, try different master mixes or optimize conditions. |

Experimental Protocols for Validation

How do I empirically validate and optimize a new qPCR assay?

Theoretical design is only the beginning. The following workflow, derived from established best practices, is essential for validating a robust assay [13].

Detailed Methodology:

- No-Template Control (NTC): Always include a reaction containing all components except the template DNA. Amplification in the NTC indicates contamination or severe primer-dimer formation [14].

- Standard Curve and Efficiency Calculation: Prepare a dilution series (e.g., 1:10, 1:100, 1:1000) of your cDNA sample. Run qPCR with this series to generate a standard curve.

- Annealing Temperature Optimization: Use a thermal gradient on your qPCR instrument to test a range of annealing temperatures (e.g., 55°C to 65°C). The optimal temperature produces the lowest Cq value with a single, specific peak in the melt curve [13]. An assay that works well over a broad temperature range is considered robust.

How do I select and validate reference genes for reliable normalization in cancer studies?

Using unstable reference genes is a major source of inaccurate results. This is particularly critical in cancer research, where treatments can alter the expression of commonly used "housekeeping" genes.

Validation Protocol [18]:

- Select Candidate Genes: Choose 3–5 potential reference genes from different functional classes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB, B2M, YWHAZ, TBP).

- Test Expression Stability: Run qPCR for all candidate genes across all your experimental conditions (e.g., different cancer cell lines, treated vs. untreated samples).

- Analyze with Stability Algorithms: Use software like NormFinder or geNorm to statistically determine the most stably expressed genes.

- Report Findings: Always report the genes selected and the validation data. For example, a 2025 study found that ACTB and ribosomal protein genes were unstable in mTOR-inhibited cancer cells, while B2M and YWHAZ were more reliable [18].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Assay Development

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Enzyme activated only at high temperatures, drastically reducing primer-dimer and non-specific amplification at setup [14]. | Essential for complex targets and multiplex PCR. |

| SYBR Green Master Mix | A ready-to-use mixture containing SYBR Green dye, buffer, dNTPs, and polymerase for simple, cost-effective qPCR [15]. | Always requires melt curve analysis for specificity confirmation. |

| TaqMan Probes & Master Mix | Hydrolysis probes that provide target-specific fluorescence, eliminating the need for post-run melt curve analysis and enabling multiplexing [12] [19]. | More expensive than SYBR Green, but superior for specificity. |

| DNase I, RNase-free | Enzyme used to degrade residual genomic DNA in RNA samples before cDNA synthesis, preventing false positives [12]. | Critical when amplicons do not span exon-exon junctions. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Enzyme for synthesizing cDNA from an RNA template. The choice of enzyme and protocol can introduce bias [15]. | Investigate potential reverse transcription bias using standard curves. |

Adherence to MIQE Guidelines

To ensure the rigor, reproducibility, and transparency of your qPCR data, adherence to the MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines is critical [20] [19]. This includes comprehensive reporting of:

- Sample details: Origin, processing, and nucleic acid quality metrics (e.g., RIN for RNA) [20].

- Assay information: Primer and probe sequences, or amplicon context sequence and unique assay ID for commercial assays [19].

- Validation data: PCR efficiency, R², LOD, and evidence of specificity for each assay [13] [19].

- qPCR protocol: Complete reaction conditions and data analysis method [17] [19].

Failure to provide this information undermines the credibility of reported findings. As stated in a 2025 commentary, "if the data cannot be reproduced, they are not worth publishing" [20].

The Role of Non-Specific Amplification and Primer-Dimer Formation in Generating Background Noise

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary causes of non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation? Non-specific amplification and primer-dimers result from a combination of factors, including inadequate primer design (e.g., self-complementarity or complementarity between primers), low annealing temperatures, excessive primer concentration, and the use of low-quality reagents. These conditions promote unintended primer interactions and amplification of off-target sequences [21] [2].

2. How can I confirm that background noise in my qPCR results is due to primer-dimers? The presence of primer-dimers can be confirmed by performing a dissociation curve (melt curve) analysis after the qPCR run. Primer-dimers typically appear as an additional peak at a lower melting temperature than your specific amplicon. Alternatively, running the qPCR products on an agarose gel will show a fuzzy smear or band below 100 bp [22] [7].

3. Why is controlling for non-specific amplification particularly critical in cancer research assays? In cancer research, assays often detect rare events, such as somatic mutations or low-abundance fusion transcripts, against a high background of wild-type DNA. Non-specific amplification can generate false positives, leading to incorrect mutation calls, or mask true low-abundance signals, compromising the accuracy of diagnosis and treatment decisions [23] [24].

4. What are the best practices for preventing contamination, a major source of false positives? To prevent contamination, use separate, dedicated work areas for pre- and post-PCR steps. Employ good laboratory practices, including using filter pipette tips, preparing single-use reagent aliquots, and routinely decontaminating surfaces with 10% bleach or UV irradiation. Always include a No-Template Control (NTC) to monitor for contamination [22] [2].

5. Are there advanced molecular techniques to suppress non-specific background? Yes, several advanced techniques exist. Xeno Nucleic Acid (XNA) molecular clamping uses synthetic DNA analogs to block the amplification of non-target sequences (e.g., wild-type DNA), allowing for the selective detection of mutations or fusions [23]. Competitive Allele-Specific TaqMan PCR (castPCR) uses an MGB blocker oligonucleotide to suppress the wild-type background, enabling highly specific detection of mutant alleles [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Amplification in the No-Template Control (NTC)

A positive signal in the NTC indicates contamination or significant primer-dimer formation.

Step 1: Identify the Source

- Perform a Melt Curve Analysis: If the melt curve shows a peak at a lower temperature than your target amplicon, it is likely primer-dimer [22] [7].

- Check the Cq Value: Late amplification (Cq >34 for SYBR Green assays) in the NTC can be a result of dimer amplification rather than true contamination [22].

Step 2: Apply Corrective Measures

- If due to contamination: Replace all reagents. Decontaminate workspaces and equipment thoroughly. Use uracil-DNA-glycosylase (UNG) in the reaction mix to degrade carryover contamination from previous PCR products [2].

- If due to primer-dimer: Optimize your reaction conditions as outlined in Issue 2.

Issue 2: Non-Specific Bands or High Background with SYBR Green Chemistry

This is a classic sign of non-specific amplification or primer-dimer formation.

Step 1: Optimize Thermal Cycling Conditions

- Increase Annealing Temperature: Use a temperature gradient to find the highest possible annealing temperature that still yields your specific product [14] [21].

- Use a Hot-Start DNA Polymerase: This enzyme is inactive at room temperature, preventing primer-dimer formation during reaction setup. It is activated only at high temperatures, improving specificity [14] [2].

- Employ Touchdown PCR: Start with an annealing temperature 5–10°C above the primer's Tm and gradually decrease it over subsequent cycles. This early stringent annealing favors specific binding [2].

Step 2: Optimize Reaction Components

- Lower Primer Concentration: High primer concentration is a common cause. Reduce the concentration, typically testing a range of 50–900 nM, to find the lowest concentration that provides efficient amplification [14] [21].

- Improve Primer Design: Re-design primers using trusted software to avoid self-complementarity (especially at the 3' ends) and complementarity between forward and reverse primers. The annealing temperatures for the primer pair should not differ by more than 3°C [21].

Step 3: Verify Primer Specificity

- Run a BLAST Search: Ensure your primer sequences are specific to the intended target and will not cross-react with other sequences in the sample [2].

The following workflow summarizes the systematic approach to troubleshooting background noise:

Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

Table 1: Impact of Common Factors on Non-Specific Amplification

| Factor | Typical Optimal Range / Condition | Effect of Deviation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primer Concentration | 50–900 nM (often ~200 nM) | High concentration increases primer-dimer risk. | [14] [21] |

| Annealing Temperature | Primer Tm ± 3°C | Low temperature promotes non-specific binding. | [14] [21] |

| Cycle Number | 30–40 cycles | Excessive cycles increase primer-dimer formation after target exhaustion. | [21] |

| Primer Dimer Cq in NTC | >34 cycles (SYBR Green) | Cq <34 suggests contamination or severe dimerization. | [22] |

| Enzyme Type | Hot-Start Polymerase | Standard polymerase can extend dimers during reaction setup. | [14] [2] |

Table 2: Advanced Techniques for Noise Suppression in Cancer Assays

| Technique | Core Principle | Key Performance Metrics | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| XNA Molecular Clamping | Synthetic XNA binds to and blocks amplification of non-target sequences (e.g., wild-type DNA). | LOD: 50 copies for fusion genes. Effectively blocks wild-type. | Detection of gene fusions (ALK, RET, ROS1) in NSCLC [23]. |

| castPCR Technology | Uses an MGB blocker oligonucleotide to suppress wild-type DNA amplification. | Detects 1 mutant in 1,000 wild-type cells. | Somatic mutation detection (e.g., KRAS, BRAF) [24]. |

| Nicking Endonuclease-based RCA (NER/Cas12a) | Exponential amplification with two circular templates to minimize nonspecific initiation. | LOD: 0.77 fM. Recognizes single-base mismatches. | Ultrasensitive detection of tumor suppressor genes (e.g., p53) [25]. |

Experimental Protocol: XNA-Based Clamping for Fusion Gene Detection

This protocol is adapted from an assay developed to detect ALK, RET, and ROS1 fusions in lung cancer FFPE samples [23].

- RNA Extraction: Extract total RNA from FFPE samples using a silica spin-column-based kit (e.g., RNeasy FFPE kit). Quantify RNA and assess quality.

- Reverse Transcription: Convert 50 ng of total RNA into cDNA using a reverse transcriptase kit with random hexamers or oligo-dT primers.

- qPCR with XNA Clamp:

- Reaction Mix: Prepare a multiplex qPCR master mix containing:

- Primers specific for the target fusion variants.

- XNA oligonucleotides designed to be complementary to the wild-type sequence.

- Hot-Start DNA Polymerase, dNTPs, and buffer.

- A fluorescent probe (e.g., TaqMan) for detection.

- Thermal Cycling:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 5 min.

- 45 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 sec.

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 60 sec (acquire fluorescence).

- Controls: Include positive controls (synthetic templates or cell lines with known fusions), negative controls (fusion-negative cell lines like A549), and a No-Template Control (NTC).

- Reaction Mix: Prepare a multiplex qPCR master mix containing:

- Data Analysis: The XNA clamp binds stably to the wild-type sequence, preventing its amplification. Only samples containing the fusion gene, which has a mismatched sequence at the XNA binding site, will produce a fluorescent signal.

The logic of this clamping mechanism is illustrated below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Reducing Background Noise

| Item | Function in Noise Reduction | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Prevents enzymatic activity during reaction setup, reducing primer-dimer formation. | Various commercial master mixes. |

| XNA Molecular Clamps | Synthetic nucleotides that block polymerase extension on non-target sequences, suppressing wild-type amplification. | Custom-designed for wild-type sequence [23]. |

| Uracil-DNA-Glycosylase (UNG) | Enzyme that degrades uracil-containing DNA, preventing carryover contamination from previous PCR products. | Often included in commercial master mixes [2]. |

| Competitive Allele-Specific Blocker | Oligonucleotide blocker that suppresses amplification of the wild-type allele in mutation detection assays. | TaqMan Mutation Detection Assays [24]. |

| High-Purity Primers | Minimizes synthesis errors and truncated sequences that can contribute to non-specific amplification. | HPLC-purified primers [21]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water & Tubes | Ensures the reaction is not compromised by external nucleases or contaminants. | Certified nuclease-free, DNase-free, RNase-free. |

For patients with advanced (stage IV) cancer, conventional imaging can take 6 to 8 weeks to determine whether a new treatment is working, leading to stressful delays that keep patients on ineffective therapies and exposed to unnecessary toxicity [26]. A novel blood test has been developed to detect treatment failure in just 2–3 weeks, addressing this critical unmet need in oncologic care [26].

This innovative assay is a quantitative PCR (qPCR)-based test that measures specific tumor-derived cell-free DNA (cfDNA) fragments in the blood. It reports a "Progression Score" (PS) ranging from 0 to 100, where high scores indicate likely rapid cancer growth and low scores suggest the therapy is effective [26]. Because the test is quick, noninvasive, and does not rely on specific genetic mutations, it can be used across many cancer types and treatments, helping oncologists decide sooner whether to continue, modify, or discontinue a patient's therapy [26] [27].

The Progression Score (PS) assay is based on the principle of cfDNA fragmentomics, which exploits the observation that cfDNA fragments from tumor cells exhibit distinct size distributions compared to healthy cfDNA [26] [28]. The assay specifically targets multi-copy retrotransposon elements (ALU elements) via qPCR, quantifying fragments of different size thresholds: >80 bp, >105 bp, and >265 bp, along with an internal control [26] [27]. A logistic regression model then integrates these quantitative measurements into the single Progression Score [26].

In a prospective study of 128 patients with metastatic lung, breast, or colorectal cancer, the PS model yielded an area under the receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curve of 0.93 for predicting radiographic progression at the first imaging timepoint [26] [27]. The scores were strongly bimodal: 92% of patients with PS > 90 experienced disease progression, while 95% with PS < 10 did not [26]. This performance demonstrates the potential of fragmentomics to provide an earlier, tumor-agnostic signal of treatment response.

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing False Positives in qPCR-Based Assays

The extreme sensitivity of qPCR methodology, while a great advantage, also makes it vulnerable to contamination and false-positive results. The following section provides a targeted troubleshooting guide for issues specifically relevant to cfDNA fragmentomic assays.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My No Template Control (NTC) shows amplification. What are the most likely causes?

- Reagent Contamination: Trace amounts of bacterial DNA in enzyme preparations or contaminants in oligonucleotides, buffers, or water can be amplified [3] [22].

- Amplicon Carryover: Aerosolized amplification products from previous PCR runs are a very common source of contamination [3] [2].

- Cross-Contamination: This can occur during sample handling when a positive sample contaminates a negative one or from contaminated laboratory equipment like pipettes [3].

- Primer-Dimer Formation: Primers can anneal to each other and amplify, especially in late cycles (>34 cycles for SYBR Green assays), producing a false signal [22] [2].

Q2: How can I distinguish primer-dimer formation from specific amplification in my NTC?

Perform a melting curve analysis after the PCR run. Specific amplification products will have a distinct, sharp melt peak at a higher temperature, while primer-dimers will generate a broader peak at a lower melting temperature [22] [2].

Q3: Our lab runs this assay frequently. What specific procedures can prevent amplicon carryover?

- Uracil-DNA-Glycosylase (UNG) Treatment: Incorporate a master mix containing dUTP and UNG. UNG enzymatically degrades any uracil-containing carryover amplicons from previous reactions before the new PCR begins, preventing their re-amplification [3] [2].

- Physical Separation: Maintain separate, dedicated rooms or hoods for reagent preparation, sample setup, and post-PCR analysis. A unidirectional workflow is critical [2].

Q4: What should I do if I confirm a contamination event in my lab?

- Replace all reagents: Discard all open tubes of buffers, enzymes, primers, and probes, and prepare fresh aliquots [22] [2].

- Decontaminate surfaces and equipment: Thoroughly clean work areas, pipettes, and equipment with a 10% bleach solution, followed by 70% ethanol or RNase/DNase-free water [3] [2].

- Use UV irradiation: If available, expose the PCR setup hood to UV light to cross-link any residual contaminating DNA [2].

Troubleshooting Table: Common qPCR False-Positive Issues

| Problem | Potential Cause | Detection Method | Corrective & Preventive Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amplification in NTC | Contaminated reagents (enzymes, water) | Systematic testing of individual reagent components | Prepare fresh aliquots; use certified nuclease-free reagents and water [3] [2] |

| Amplification in NTC | Amplicon carryover from previous runs | Review of workflow and lab layout | Implement UNG treatment; enforce physical separation of pre- and post-PCR areas [3] [2] |

| Amplification in NTC | Primer-dimer artifacts | Melt curve analysis (shows low-Tm peak) | Re-optimize primer concentrations; use hot-start PCR [22] [2] |

| Amplification in NTC | Cross-contamination from samples | Tracking sample placement on plate | Use filter pipette tips; place NTC wells away from positive samples [2] |

| High Background Noise | Degraded fluorescent probe | Fluorometric scan or mass spectrometry | Aliquot probes to minimize freeze-thaw cycles; protect from light [22] |

| Non-specific Amplification | Poor primer specificity | In silico BLAST analysis for cross-reactivity | Redesign primers to target unique hypervariable regions [22] |

Experimental Protocol: Core Methodology of the cfDNA Fragmentomic Assay

The following protocol details the key steps for the novel cfDNA fragmentomic assay as described in the foundational study, providing a framework for researchers to implement and validate similar approaches [26].

Sample Collection and Processing

- Blood Collection: Collect 8–10 mL of peripheral blood into Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT tubes.

- Transport: Transport tubes at ambient temperature via overnight courier. Critical Step: Process samples within 120 hours (5 days) of collection, as delays can affect cfDNA concentrations [26].

- Plasma Separation: Use a two-step centrifugation protocol.

- Centrifuge Streck tubes at 1,600× g for 10 minutes at 15°C to separate plasma.

- Transfer the plasma to a new tube and centrifuge at 16,000× g for 10 minutes at room temperature to remove any remaining cellular debris.

- Storage: Aliquot the clarified plasma into cryogenic tubes and store at -80°C until cfDNA extraction [26].

Cell-Free DNA Extraction

- Extraction Kit: Use the QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit.

- Starting Volume: Use 500 µL of plasma.

- Protocol Modification: Omit the carrier RNA from the ACL buffer during the extraction procedure [26].

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Setup and Analysis

- Targets: Design qPCR assays to target multi-copy retrotransposon elements (e.g., ALU) for three fragment size ranges: >80 bp, >105 bp, and >265 bp. Include an internal control [26] [27].

- Controls: Each run must include:

- qPCR Method: The published study used a standard qPCR methodology. To enhance specificity, consider Hot-Start PCR to suppress polymerase activity until the high temperatures of the first denaturation step are reached, thereby reducing non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation at room temperature [2].

- Data Analysis: Input the qPCR quantification cycle (Cq) values for the different fragment sizes into the proprietary logistic regression model to calculate the Progression Score (PS) on a scale of 0–100 [26].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow of the cfDNA fragmentomic assay, highlighting key steps and critical quality control points.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for implementing the cfDNA fragmentomic assay, with a focus on components that impact assay reliability and contamination control.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function / Role | Key Considerations for False-Positive Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT Tubes | Stabilizes blood samples for cfDNA analysis during transport. | Prevents release of genomic DNA from white blood cells, which can contaminate the cfDNA sample and alter fragmentomic profiles [26]. |

| QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit | Extraction of high-quality cfDNA from plasma. | The protocol's omission of carrier RNA is a specific modification that prevents potential interference in downstream qPCR [26]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Enzyme for qPCR amplification. | Reduces non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by remaining inactive until the initial high-temperature denaturation step [2]. |

| UNG (Uracil-N-Glycosylase) | Enzyme for contamination control. | Degrades carryover amplicons from previous PCR runs when dUTP is incorporated, critically preventing false positives [3] [2]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Solvent for preparing PCR master mixes. | Must be certified sterile and nuclease-free to avoid introduction of contaminating DNA or PCR inhibitors [2]. |

| Filter Pipette Tips | For accurate and sterile liquid handling. | Prevents aerosol-based cross-contamination between samples; essential for both sample and reagent handling [2]. |

Strategic Contamination Control Framework

Beyond immediate troubleshooting, a proactive, systematic strategy is required to safeguard the integrity of sensitive qPCR assays in a clinical research setting. The following diagram and table outline a comprehensive defense strategy.

Diagram 2: A multi-phase strategic framework for preventing contamination in qPCR workflows.

Table: Proactive Contamination Control Measures

| Phase | Measure | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-PCR | Spatial Segregation | Maintain physically separate rooms for reagent preparation, sample setup, and post-PCR analysis. Enforce a unidirectional workflow for personnel [2]. |

| Pre-PCR | Reagent Management | Prepare single-use aliquots of all reagents, primers, and probes. Use certified nuclease-free water and buffers [22] [2]. |

| Pre-PCR | Environmental Decontamination | Regularly clean surfaces and equipment with 10% bleach (sodium hypochlorite), followed by ethanol or water to remove residue. Use UV irradiation in hoods when unoccupied [3] [2]. |

| PCR | In-Reaction Safeguards | Use a master mix containing UNG and dUTP for carryover prevention. Employ Hot-Start polymerase chemistry to improve specificity [2]. |

| PCR | Control Strategy | Include NTCs and positive controls on every plate. Place NTCs away from high-concentration samples to monitor for well-to-well contamination [3] [2]. |

| Post-PCR | Amplicon Containment | Perform all analysis of amplified products in the dedicated post-PCR area. Prefer closed-tube detection systems to avoid opening plates containing amplicons [2]. |

Best Practices in Assay Design and Laboratory Workflow to Enhance Specificity

FAQs: Core Design Principles

1. What are the optimal physicochemical properties for qPCR primers and probes?

The table below summarizes the critical parameters for designing effective primers and probes to ensure high specificity and yield in qPCR assays, crucial for sensitive applications like cancer research [29] [30].

Table 1: Optimal Design Parameters for qPCR Primers and Probes

| Parameter | Primers | Probes | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | 18–24 nucleotides [29] | 15–30 nucleotides [29] | Balances specificity and efficient binding. |

| GC Content | 40–60% [30] | 35–60% [29] | Prevents overly stable (high GC) or unstable (low GC) duplexes. |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 54°C–65°C; ideally ≥60°C [29] [31] | 5-10°C higher than primer Tm [30] | Ensures specific hybridization; higher probe Tm guarantees probe binding before primers. |

| 3'-End Stability (GC Clamp) | Max. 3 G/C bases in last 5 bases [30] | Avoid G at the 5' end [29] | Promotes specific initiation of amplification; avoids fluorescence quenching. |

2. Why is it critical to avoid secondary structures, and how can I check for them?

Secondary structures such as hairpins (intramolecular folding) and primers-dimers (intermolecular binding) compete with template binding, drastically reducing amplification efficiency and increasing false negatives [29] [30]. Their formation is governed by Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG), where larger negative values indicate more stable, problematic structures [30].

Table 2: Guidelines for Tolerable Secondary Structure Stability (ΔG)

| Structure Type | Acceptable ΔG Threshold |

|---|---|

| 3' End Hairpin | > -2 kcal/mol [30] |

| Internal Hairpin | > -3 kcal/mol [30] |

| 3' End Self-Dimer | > -5 kcal/mol [30] |

| Internal Self-Dimer | > -6 kcal/mol [30] |

Use in-silico tools like OligoAnalyzer [32] or Primer Premier [30] to simulate and calculate the ΔG values for your sequences. These tools help identify self-complementarity and self 3'-complementarity, which should be kept as low as possible [29].

3. How do I calculate the annealing temperature (Ta) from the Tm?

The annealing temperature (Ta) is distinct from the Tm and is critical for specificity. While a common rule of thumb is to set the Ta 2–5°C below the primer Tm [29], a more precise method uses the Rychlik formula [30]:

Ta Opt = 0.3 x Tm(primer) + 0.7 x Tm(product) – 14.9

Where:

Tm(primer)is the melting temperature of the less stable primer-template pair.Tm(product)is the melting temperature of the PCR product.

For the highest specificity, always empirically determine the optimal Ta using a temperature gradient PCR [33]. A robust assay will perform well over a broad temperature range, whereas an assay that only works in a narrow window is prone to failure with minor condition changes [13].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Amplification in No-Template Control (NTC) indicates contamination or primer-dimer formation.

Amplification in the NTC is a classic sign of false positives, which can severely compromise data integrity in cancer biomarker detection [3] [22].

Table 3: Troubleshooting False Positives in the NTC

| Observation | Probable Cause | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Melt curve of NTC matches specific product. | Contamination from amplicon carryover or contaminated reagents [3] [31]. | 1. Replace all reagents and thoroughly clean workspace with 10% bleach [22] [31]. 2. Use UNG/UDG treatment in the master mix to degrade carryover contaminants [3] [31]. 3. Implement physical separation of pre- and post-PCR areas [22]. |

| Melt curve of NTC shows a lower Tm (e.g., primer-dimer). | Non-specific amplification due to primer secondary structures [31]. | 1. Redesign primers with stricter adherence to design rules (see Table 1) [31]. 2. Re-optimize primer concentrations [31]. 3. Use a primer design tool to minimize self- and cross-dimerization potential [32]. |

| Using universal primers (e.g., for 16S rRNA). | Amplification of bacterial DNA present in enzymes or consumables [22]. | 1. Design primers for a hypervariable region [22]. 2. Use blocking oligonucleotides to suppress background amplification [22]. 3. Perform a BLAST search to check for cross-reactivity with common contaminants [22]. |

The following workflow outlines a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving false positives:

Diagnosing NTC Amplification

Problem: My primers are well-designed, but I still get low yield or no amplification.

- Cause: Template Secondary Structure. Stable secondary structures in the RNA/DNA template at the primer binding site can prevent primer annealing [30]. This is a common issue when working with complex biological samples.

- Solution:

- Use software that predicts template secondary structure and designs primers in accessible regions [30].

- Consider using touch-down PCR protocols, which start with a higher annealing temperature and gradually lower it, thereby favoring specific amplification before secondary structures can interfere once the reaction is established [34].

- Ensure you are using a master mix formulated for high GC-rich or structured templates.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: Empirical Determination of Optimal Annealing Temperature (Ta)

- Design Primers: Design your primer pair according to the parameters in Table 1.

- Calculate Theoretical Tm: Use a reliable Tm calculator, such as the one from Thermo Fisher Scientific [33] or IDT's OligoAnalyzer [32], which uses the nearest-neighbor thermodynamic method.

- Set Up Gradient PCR:

- Prepare a master mix containing all reaction components (polymerase, buffer, dNTPs, primers, and a validated positive control template).

- Aliquot the master mix into your qPCR plate.

- On your thermal cycler, set an annealing temperature gradient. The range should start at approximately 5°C below the calculated Tm and extend up to the extension temperature (e.g., 60°C for two-step PCR) [33].

- Analyze Results:

- After the run, analyze the amplification curves and efficiency.

- The optimal Ta is the highest temperature that yields a single, specific product with the lowest Cq (quantification cycle) and highest fluorescence [13].

- Confirm product specificity with melt curve analysis.

Protocol: Validating Assay Specificity and Efficiency

- Run Controls: Include a No-Template Control (NTC) and a no-reverse-transcription control (for RNA targets) to check for genomic DNA contamination or primer-dimer artifacts [3].

- Generate a Standard Curve: Prepare a serial dilution (at least 5 points) of a known quantity of your target template.

- Calculate Efficiency: Perform qPCR on the dilution series. The amplification efficiency (E) is calculated from the slope of the standard curve using the formula: E = -1 + 10^(-1/slope) [34].

- Interpret Results: An ideal, highly specific assay will have an efficiency between 90% and 105%, with a correlation coefficient (R²) of >0.99 [31]. Efficiency outside this range suggests issues with primer design or reaction conditions that require optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Robust qPCR Assays

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Enzymes like Phusion or Platinum SuperFi offer high specificity, crucial for distinguishing true targets in complex cancer samples [33]. |

| Master Mix with UNG/UDG | Contains Uracil-N-Glycosylase, which degrades PCR products from previous reactions, effectively controlling carryover contamination [3] [31]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | A critical, often overlooked reagent. Must be certified free of nucleases and contaminants to prevent degradation of oligonucleotides and false results [22]. |

| Validated Positive Control Template | Synthetic or cloned DNA/RNA used to validate assay performance, calculate efficiency, and serve as a run control [3]. |

| qPCR Probes (Dual-Labeled) | Hydrolysis probes (e.g., TaqMan) provide superior specificity over intercalating dyes by requiring hybridization to the target for signal generation [29]. |

| RT-qPCR Kit for FFPE Samples | Specialized kits are optimized to overcome the challenges of fragmented and cross-linked RNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue, a common source in cancer research [34] [23]. |

In quantitative PCR (qPCR) research, particularly in sensitive applications like cancer biomarker detection, false positives can severely compromise data integrity and lead to incorrect conclusions. The extreme sensitivity of qPCR, which allows for the detection of minute amounts of DNA, also makes it vulnerable to contamination from amplified DNA products (amplicons) generated in previous experiments [6] [3]. Implementing robust physical separation of pre- and post-PCR areas and a strict unidirectional workflow is not merely a recommendation but a fundamental necessity for generating reliable, reproducible results in cancer research and drug development. This guide provides detailed protocols and troubleshooting advice to help researchers establish and maintain a contamination-free laboratory environment.

Core Concepts: Physical Separation and Unidirectional Workflow

What are a unidirectional workflow and why are they critical for qPCR?

A unidirectional workflow is a system where materials and personnel move in one direction only: from "clean" areas (where pre-PCR steps are performed) to "dirty" areas (where post-PCR steps are handled) [35] [36]. The primary goal is to prevent the backflow of amplified DNA (amplicons) from post-PCR areas into pre-PCR areas. Since qPCR can produce millions of copies of a DNA target, even microscopic aerosols containing these amplicons can contaminate reagents, equipment, or new reaction setups, leading to false-positive results [6]. This is especially crucial in cancer research, where detecting low-abundance circulating tumour DNA (ctDNA) requires pristine conditions to avoid reporting false biomarkers [37].

The following diagram illustrates the ideal unidirectional workflow and the specific activities permitted in each designated zone.

FAQ: How can PCR amplicons cause contamination?

During the post-PCR phase, when tubes or plates are opened, significant quantities of amplified DNA product can become aerosolized and disperse into the lab environment [6]. These aerosolized amplicons are stable and can settle on surfaces, equipment, gloves, and lab coats. If introduced into a new qPCR reaction mix—either through contaminated reagents, pipettes, or personnel—they act as a ready-made template for amplification. This leads to amplification signals in "No Template Control" (NTC) wells and can cause false positives in experimental samples, critically misleading cancer diagnostics and research outcomes [6] [3].

Implementation Guide: Setting Up Your Laboratory

Physical Laboratory Layout

The gold standard is to have four separate rooms. However, if space is limited, physically separated, dedicated areas with dedicated equipment are the minimum requirement [35].

Table 1: Laboratory Area Specifications and Functions

| Laboratory Area | Primary Function | Key Equipment & Materials | What is FORBIDDEN |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reagent Preparation [35] | Preparation of master mixes; aliquoting of pristine reagents. | Dedicated pipettes, filter tips, microcentrifuge, vortex, master mix reagents, nuclease-free water. | Any DNA template, samples, or PCR products. |

| Sample Preparation / Template Addition [35] | Nucleic acid extraction from samples; addition of DNA template to master mix. | Dedicated pipettes, filter tips, centrifuge, vortex, extracted DNA/RNA samples. | PCR amplifiers or amplified products. |

| Amplification [35] | Housing of qPCR thermocyclers; running the amplification reaction. | qPCR thermocyclers, sealed reaction plates/tubes. | Unsealing reaction plates/tubes after the run. |

| Post-PCR Analysis [35] [36] | Analysis of amplified products (e.g., gel electrophoresis). | Gel documentation systems, tube openers. | Bringing anything from this area back to a pre-PCR area. |

Standard Operating Procedures for a Unidirectional Workflow

- Movement of Personnel: Lab members must not move from a post-PCR area back to a pre-PCR area on the same day. If unavoidable, they must thoroughly wash hands, change lab coats, and use dedicated PPE for the clean area [35].

- Movement of Equipment and Consumables: Supplies (e.g., pipettes, tip boxes, lab coats) must be dedicated to each area. Never move equipment or consumables from a "dirty" (post-PCR) area to a "clean" (pre-PCR) area. If an essential item must be moved backward, it must be decontaminated first [35].

- Data Handling: Lab books, paperwork, and electronic devices that have been in a post-PCR area should not be taken into pre-PCR areas. Use duplicate print-outs of protocols or digital copies on dedicated computers if necessary [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Contamination Control

| Item | Function in Contamination Control |

|---|---|

| Aerosol-Resistant Filtered Pipette Tips [6] [35] | Prevent aerosols and liquids from entering the pipette shaft, protecting the instrument from becoming a source of contamination. |

| Uracil-N-Glycosylase (UNG) [6] [3] | An enzymatic system to destroy carryover contamination from previous PCRs. It requires using dUTP in the PCR mix instead of dTTP. UNG selectively degrades any uracil-containing DNA from prior amplifications before the new PCR begins. |

| Fresh 10% Bleach Solution [6] [35] | A potent DNA-destroying decontaminant for surfaces. It must be made fresh frequently and allowed 10-15 minutes of contact time for effectiveness. |

| 70% Ethanol [6] [35] | Effective for general cleaning and degreasing. For DNA decontamination, it should be used after bleach or in conjunction with UV irradiation. |

| Aliquoted Reagents [6] [35] | Dividing bulk reagents into single-use aliquots prevents repeated freeze-thaw cycles and avoids contaminating the entire stock. |

| No-Template Controls (NTCs) [6] [3] | The essential quality control. Contains all reaction components except the DNA template. Amplification in the NTC indicates contamination. |

Troubleshooting Common Contamination Scenarios

FAQ: Amplification is observed in my No-Template Control (NTC). What should I do?

- Interpret the NTC Result:

- Consistent Ct across all NTCs: Suggests a reagent is contaminated. The source could be the water, master mix, or primers/probes [6] [3].

- Random Ct values in NTCs: Suggests random environmental contamination or aerosol contamination during plate setup, potentially from a nearby open tube of positive control or sample [6].

- Systematic Response:

- Replace Reagents: Systematically replace reagents, starting with water and master mix, to identify the contaminated component [6].

- Decontaminate Workspace: Thoroughly clean all work surfaces, equipment, and pipettes in the pre-PCR areas with 10% bleach followed by 70% ethanol or a commercial DNA decontaminant [6] [35].

- Review Practices: Ensure you are using filter tips, centrifuging tubes before opening, and that your physical separation is being strictly followed [6].

FAQ: My laboratory space is limited. How can I implement physical separation?

- Use Designated Benches or Cabinets: Designate specific bench areas at opposite ends of the lab for pre- and post-PCR work. A laminar flow cabinet or dead air box can serve as an excellent clean "room" for reagent preparation and reaction assembly [35] [36].

- Temporal Separation: Perform all pre-PCR work first in the morning, before any post-PCR analysis is conducted. Clean the area thoroughly afterward.

- Dedicated Equipment is Non-Negotiable: Even in a shared space, you must use separate, clearly labelled pipettes, tip boxes, and lab coats for pre- and post-PCR work [35].

Decontamination Protocols and Best Practices

Surface and Equipment Decontamination

- For surfaces (bench tops): Clean with a 10% (v/v) bleach solution (sodium hypochlorite). Allow it to wet the surface and remain for 10-15 minutes, then wipe down with de-ionized water or 70% ethanol to remove residue [6] [35].

- For sensitive equipment (pipettes, centrifuges): Do not use bleach as it can damage metals and plastics. Wipe down thoroughly with 70% ethanol. If possible, expose to UV light inside a closed cabinet for 30 minutes for more effective DNA destruction [35].

- Pipette Sterilization: Autoclave pipettes regularly if the manufacturer permits. For non-autoclavable pipettes, disassemble and clean components with 70% ethanol or a commercial DNA decontaminant [35].

Procedural Best Practices

- Pipetting Technique: Use slow, smooth pipetting actions to minimize aerosol creation. Always centrifuge tubes briefly before opening to collect contents at the bottom [6] [35].

- Glove Management: Change gloves frequently, especially after touching potentially contaminated surfaces, your face, or phone. Always change gloves when moving between different designated areas [6] [35].

- Aliquot Everything: Never use a stock reagent bottle directly in an experiment. Always prepare aliquots to limit exposure and potential contamination of the entire stock [6] [35].

By meticulously implementing these guidelines for physical separation, unidirectional workflow, and rigorous decontamination, research laboratories can significantly reduce the risk of false positives, thereby ensuring the integrity and reliability of their qPCR data in critical cancer research and drug development.

Utilizing Hot-Start PCR and Touchdown Protocols to Suppress Early Mis-Priming

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary cause of false positives in qPCR cancer assays, and how do these techniques help? False positives in qPCR often arise from non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formations, especially during reaction setup and the initial cycles before thermal cycling begins. Hot-Start PCR and Touchdown PCR are designed to suppress this early mis-priming. Hot-Start PCR inhibits the DNA polymerase's activity at room temperature, preventing non-specific synthesis from occurring before the first denaturation step [38] [39]. Touchdown PCR enhances specificity by starting with an annealing temperature too high for imperfect primer binding, then gradually lowering it, which gives a "head start" to the correct target amplicon and allows it to outcompete non-specific products [40] [41].

Q2: Can Hot-Start PCR and Touchdown PCR be used together? Yes, these techniques are highly complementary. Using a Hot-Start polymerase ensures the reaction remains pristine during setup, while the Touchdown cycling protocol further enriches specificity during the early amplification cycles. This powerful combination is highly recommended for challenging applications like detecting low-abundance cancer biomarkers to maximize specificity and sensitivity [40].

Q3: My qPCR assay has low yield despite high template quality. What optimization should I try? Low yield can result from an annealing temperature that is too high or insufficient enzyme activity. Consider these steps:

- Verify Annealing Temperature: Use a Tm calculator and run a temperature gradient. With Touchdown PCR, ensure your starting temperature is not excessively high [42] [43].

- Incorporate Additives: For difficult templates (e.g., GC-rich regions), use enhancers like DMSO (1-10%), formamide (1.25-10%), or Betaine (0.5 M to 2.5 M) [42].

- Check Mg²⁺ Concentration: Optimize the Mg²⁺ concentration in 0.2-1 mM increments, as it is crucial for polymerase activity [43].

Q4: How do I choose between different types of Hot-Start polymerases? The choice depends on your priorities for activation speed, specificity, and potential for contamination. The table below compares the common inhibition methods.

| Inhibition Method | Mechanism | Activation | Key Advantages | Potential Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibody-based | A monoclonal antibody binds the enzyme's active site [38]. | Initial denaturation (1-3 minutes) [38]. | Fast, full activation; high specificity [38]. | Animal-derived antibodies risk mammalian DNA contamination [38]. |

| Aptamer-based | Specific oligonucleotides bind the active center [38]. | Very fast activation (~30 seconds) [38]. | Fully synthetic; no animal contaminants; fast [38]. | Potentially less stringent binding, may allow minor non-specificity [38]. |

| Chemical Modification | Enzyme is covalently modified to block activity [38]. | Longer heat activation (>10 minutes) [38]. | Highly stable; allows gradual activation for higher efficiency [38]. | Long activation can damage DNA; not suitable for long fragments (>3kb); inhibitor may not fully detach [38]. |

Q5: What are the critical steps to prevent contamination in sensitive qPCR assays for cancer research? Preventing contamination requires strict laboratory practice:

- Physical Separation: Use separate, dedicated rooms or areas for pre-PCR (reagent prep, sample handling), PCR amplification, and post-PCR analysis [2].

- Unidirectional Workflow: Maintain a one-way flow of materials and personnel from clean to post-amplification areas. Never bring post-PCR products into pre-PCR areas [2].

- Meticulous Technique: Use aerosol-resistant pipette tips, fresh gloves, and dedicated lab coats. Regularly decontaminate surfaces with 10% sodium hypochlorite or UV light [2].

- Essential Controls: Always include a no-template control (NTC) to detect reagent or environmental contamination [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Non-Specific Amplification and False Positives

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Multiple bands or smears on gel/post-run analysis | Primer annealing temperature is too low [43]. | Increase annealing temperature. Implement Touchdown PCR: start 5-10°C above Tm and decrease by 1°C every cycle/2nd cycle [40] [41]. |

| False positive in No-Template Control (NTC) | Contamination from amplicons, reagents, or environment [2]. | Use Uracil-DNA-glycosylase (UNG): incorporate dUTP in place of dTTP; UNG degrades contaminating amplicons from previous runs before PCR starts [2]. |

| Non-specific products form during reaction setup | Polymerase activity at room temperature [38]. | Switch to a Hot-Start polymerase (antibody or aptamer-based for fast activation). Keep all reagents on ice until cycler start [38] [40]. |

| Primer-dimer formation | Primers annealing to themselves or each other at 3' ends [42]. | Redesign primers to avoid 3' end complementarity. Use a Hot-Start polymerase. Increase annealing temperature. |

Guide 2: Resolving Low or No Amplification

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|