Strategies to Minimize False Positives in Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing the pervasive challenge of false positives in pharmacophore-based virtual screening.

Strategies to Minimize False Positives in Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on addressing the pervasive challenge of false positives in pharmacophore-based virtual screening. It covers the fundamental causes of false positives, explores advanced methodological strategies like pharmacophore filtering and machine learning integration, details troubleshooting and optimization techniques using pre- and post-screening filters, and discusses rigorous validation protocols through ROC curves and enrichment factors. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this resource aims to enhance the efficiency and reliability of virtual screening campaigns in drug discovery.

Understanding False Positives: The Fundamental Challenge in Pharmacophore Screening

FAQs: Understanding False Positives in Virtual Screening

What is a false positive in computational drug discovery? A false positive occurs when a compound is computationally predicted to be biologically active but fails to show actual activity in experimental validation [1]. In virtual screening, only about 12% of top-scoring compounds typically show activity in biochemical assays, meaning the majority of predictions are false positives [2]. This represents a significant waste of resources as these compounds proceed to expensive experimental testing without providing real value.

How do false positives differ from false negatives? A false positive (Type I error) incorrectly identifies an inactive compound as active, while a false negative (Type II error) fails to identify a truly active compound [1]. The balance between these errors depends on research goals: reducing false negatives might be prioritized in early discovery to avoid missing potential hits, while later stages focus on reducing false positives to conserve resources [3].

What are the main causes of false positives in pharmacophore-based screening? False positives arise from multiple factors including:

- Simplistic scoring functions that cannot capture complex binding interactions [2]

- Insufficient training data with inadequate decoy compounds during model development [2]

- Assay interference mechanisms such as compound aggregation, chemical reactivity, or inhibition of reporter proteins [4]

- Inadequate treatment of receptor flexibility where each conformational model introduces its own false positives [5]

Troubleshooting Guides: Reducing False Positives

Problem: High False Positive Rate in Virtual Screening Hits

Issue: Too many computationally selected compounds show no activity in biochemical assays.

Solutions:

- Implement Multi-Conformation Docking

Use Advanced Machine Learning Classifiers

Apply Interference Prediction Tools

Problem: Compounds Showing Artificial Activity in Confirmatory Assays

Issue: Initial screening hits fail to show dose-dependent activity or demonstrate artifactual behavior.

Solutions:

- Employ Multiple Orthogonal Assays

- Implement Strategic Filtering

Experimental Protocols & Data

Quantitative Assessment of Screening Performance

Table 1: Virtual Screening Performance Metrics Across Methods

| Screening Method | Typical Hit Rate | Most Potent Hit (Median) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Structure-Based Virtual Screening | ~12% | ~3 μM Kd/Ki | High false positive rate from simplistic scoring functions [2] |

| Pharmacophore-Based Screening with Filters | Variable (15-25%) | Dependent on target and model quality | Requires careful model validation and interference filtering [6] |

| Machine Learning Classifiers (vScreenML) | Up to 43% (reported for AChE) | 280 nM IC50 (best hit) | Dependent on quality training data with compelling decoys [2] |

| Multi-Conformation Docking Strategy | Significantly improved enrichment | Better than single conformation | Computationally intensive; requires receptor dynamics data [5] |

Detailed Methodology: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Protocol for Reduced False-Positive Pharmacophore Screening

Protein Structure Preparation

Pharmacophore Feature Generation

Virtual Screening Implementation

Hit Triage and Validation

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools for False Positive Reduction

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application in False Positive Reduction |

|---|---|---|

| Liability Predictor | Predicts assay interference compounds | Identifies thiol-reactive, redox-active, and luciferase-inhibiting compounds [4] |

| D-COID Dataset | Training set with compelling decoys | Machine learning model training for improved virtual screening [2] |

| vScreenML | Machine learning classifier | Distinguishes true actives from decoys in structure-based screening [2] |

| Multiple Receptor Conformations | Accounts for protein flexibility | Identifies compounds that bind favorably across different conformational states [5] |

| Pharmacophore Exclusion Volumes | Represents steric constraints | Filters compounds that would clash with binding site residues [7] |

| Orthogonal Assay Systems | Multiple detection methods | Confirms activity through different experimental readouts [3] |

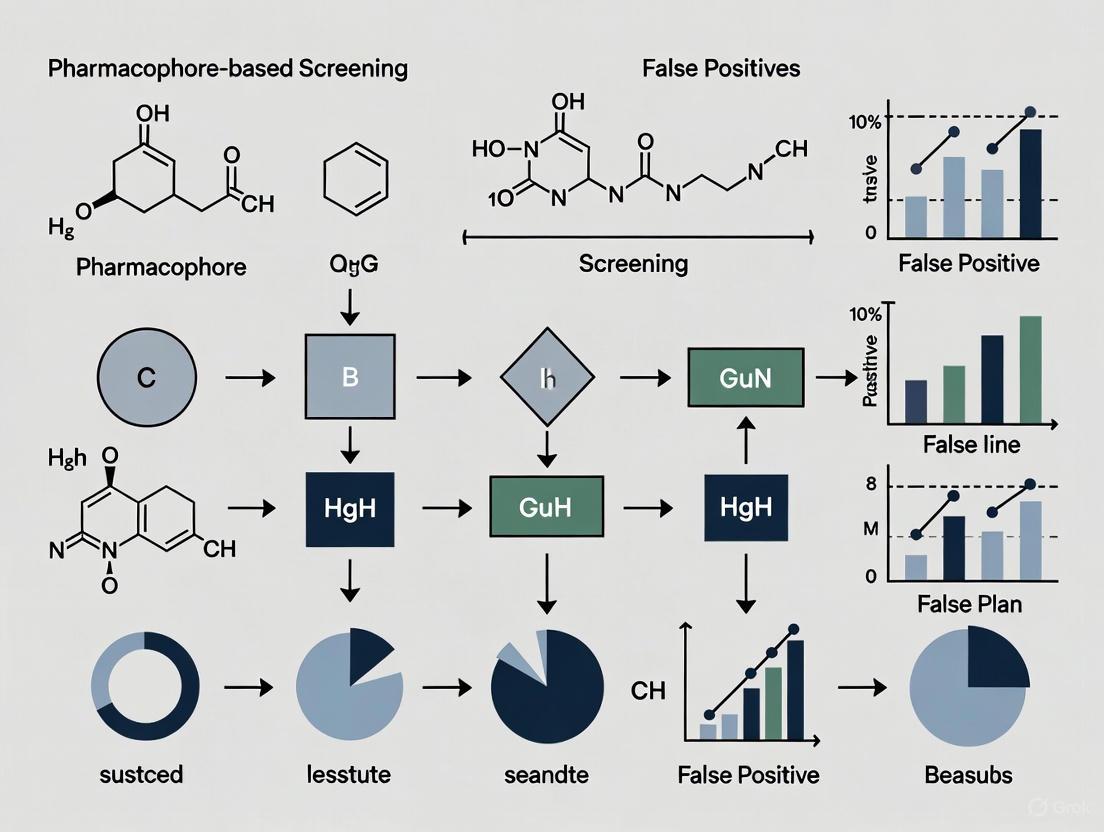

Workflow Visualization

Diagram: Integrated False Positive Reduction Strategy

Integrated Strategy for False Positive Reduction

Diagram: Assay Interference Mechanisms

Common Assay Interference Mechanisms

This technical support guide addresses two prevalent challenges in pharmacophore-based virtual screening that contribute to high false positive rates. The content is framed within a broader research thesis focused on improving the reliability of computational drug discovery.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the consequences of setting my pharmacophore feature tolerances too loosely? Excessively permissive feature tolerances, or high "fuzziness," increase the risk of false positives by accepting compounds that match the spatial arrangement but lack the precise chemical complementarity required for strong binding. Overly loose tolerances can lead to poorer activity enrichment in virtual screening results, meaning fewer truly active compounds are retrieved among the top-ranked candidates [10].

Q2: How does conformer generation quality affect my screening results? Inadequate conformer sampling can cause bioactive conformations to be missed entirely during virtual screening. Since pharmacophore matching relies on pre-generated conformers, if the bioactive conformation isn't present in your ensemble, even perfect ligands will be rejected as false negatives. Research shows that for structure-based tasks, generating at least 250 conformers per compound using state-of-the-art methods like RDKit's ETKDG provides reasonable coverage of conformational space [11].

Q3: What strategies can help reduce false positives from pharmacophore screening? Combining docking with pharmacophore filtering has shown promise for reducing false positives. This approach uses docking for pose generation followed by pharmacophore filtering to eliminate poses lacking key interactions. Additionally, using multiple receptor conformations and selecting only compounds that rank highly across all conformations can help eliminate false positives that arise from fitting specific receptor states [12] [5].

Q4: Are there computational tools that help optimize these parameters? Yes, several specialized tools are available. ZINCPharmer provides an online interface for pharmacophore search of purchasable compounds and includes features for query refinement [13]. Pharmer uses efficient indexing algorithms for rapid exact pharmacophore search [14]. For conformer generation, RDKit with ETKDG parameters is widely used, while newer approaches like ABCR (Algorithm Based on Bond Contribution Ranking) aim to improve coverage of conformational space with fewer conformers [11] [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High False Positive Rate in Virtual Screening

Symptoms:

- High computational hit rate but low experimental confirmation

- Retrieved compounds lack key interactions with binding site

- Poor correlation between computational ranking and experimental activity

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Analyze feature tolerances | Reduce radii around pharmacophore features; start with 1.0Å tolerance and adjust based on target flexibility [11]. |

| 2 | Add exclusion volumes | Represent forbidden regions of binding site to eliminate sterically clashing compounds [7]. |

| 3 | Implement consensus filtering | Apply multiple receptor conformations and select only intersections from top-ranked lists [5]. |

| 4 | Validate with known actives/inactives | Test pharmacophore model against compounds with known activity to verify selectivity [12]. |

Issue 2: Poor Bioactive Conformation Recovery

Symptoms:

- Known active compounds missed in virtual screening

- Inability to reproduce crystallographic ligand poses

- High RMSD between generated and bioactive conformations

Diagnosis and Resolution:

| Step | Action | Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Increase conformer ensemble size | Generate 250+ conformers per compound for reasonable bioactive conformation recovery [11]. |

| 2 | Evaluate conformer generation methods | Compare RDKit's ETKDG vs. knowledge-based vs. machine learning approaches for your specific target class. |

| 3 | Apply energy minimization | Use force fields like UFF as post-processing to refine conformer geometries [11]. |

| 4 | Consider molecular flexibility | Allocate more conformers for compounds with high rotatable bond count (>10) [15]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimizing Pharmacophore Feature Tolerances

Purpose: To establish methodical approaches for setting pharmacophore feature tolerances that balance sensitivity and specificity.

Materials:

- Protein structure with binding site definition

- Set of known active compounds with diverse scaffolds

- Set of confirmed inactive compounds

- Pharmacophore modeling software (e.g., MOE, LigandScout, ZINCPharmer)

Methodology:

- Create initial pharmacophore model from protein-ligand complex or multiple active ligands

- Define key interaction features (H-bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic areas, charged groups)

- Set initial tolerances based on:

- Test model performance using known actives and inactives

- Iteratively refine tolerances to maximize enrichment of actives while excluding inactives

- Validate optimized model with an independent test set not used in training

Protocol 2: Comprehensive Conformer Generation and Sampling

Purpose: To generate conformational ensembles that adequately represent bioactive conformations while maintaining computational efficiency.

Materials:

- Compound library in SMILES or 2D structure format

- Conformer generation software (RDKit, OMEGA, ABCR, or DMCG)

- High-performance computing resources for large libraries

- Reference set of protein-ligand complexes for validation

Methodology:

- Select appropriate conformer generator based on molecular flexibility:

- Set generation parameters:

- Validate ensemble quality using:

- RMSD to bioactive conformations from Platinum or PDBBind datasets

- Coverage of conformational space using diversity metrics

- Apply to virtual screening using tools like Pharmit or Pharmer for efficient searching [11] [14]

Workflow Diagrams

Figure 1: Iterative Optimization Workflow for addressing common pharmacophore screening pitfalls. The red nodes indicate critical points where false positives commonly originate and require particular attention.

Figure 2: Problem-Solution Mapping for two common pitfalls in pharmacophore-based screening, showing the direct relationship between specific issues and their targeted solutions.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool/Category | Examples | Function in Research | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Modeling | MOE, LigandScout, ZINCPharmer | Create and refine pharmacophore hypotheses; screen compound libraries | Choose based on structure/ligand-based approach; check feature customization options [12] [13] [7] |

| Conformer Generation | RDKit/ETKDG, OMEGA, ABCR, DMCG | Generate 3D conformational ensembles for screening | Evaluate bioactive conformation recovery; consider computational efficiency [11] [15] |

| Virtual Screening Platforms | Pharmer, Pharmit, LIQUID | Efficient pharmacophore search of large compound libraries | Assess scalability to your library size; check alignment-based vs. fingerprint methods [13] [11] [14] |

| Validation Datasets | Platinum, PDBBind, DUDE | Benchmark performance using known actives/inactives | Ensure relevance to your target class; verify quality of experimental data [11] [2] |

| Post-Screening Analysis | GoldMine, Pose-Filter scripts, vScreenML | Filter results; apply machine learning to reduce false positives | Implement multiple filtering strategies; use consensus approaches [12] [2] [5] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are promiscuous inhibitors and frequent hitters? Promiscuous inhibitors, or frequent hitters, are compounds that produce false-positive results across multiple high-throughput screening (HTS) assays, regardless of the biological target [16] [17]. They act through non-specific, spurious mechanisms rather than targeted, drug-like interactions. Their activity is often irreproducible in subsequent experiments, leading to wasted resources and effort [16] [18].

2. What are the common mechanisms by which these compounds interfere with assays? The primary mechanisms of interference include:

- Colloidal Aggregation: Compounds self-associate into particles (30-1000 nm in diameter) that non-specifically inhibit enzymes by adsorbing protein molecules onto their surface [16].

- Chemical Reactivity: Compounds contain reactive functional groups (e.g., aldehydes, epoxides) that form covalent bonds with protein targets, such as cysteine residues [17] [19].

- Assay Interference: Compounds interfere with the detection method itself, for example, by absorbing light in spectroscopic assays (autofluorescence) or inhibiting a reporter enzyme like firefly luciferase (FLuc) [17].

3. Are there specific chemical structures I should avoid? Yes, certain structural classes are notorious for promiscuous behavior. These include rhodanines, catechols, quinones, and 2-amino-3-carbonylthiophenes [18] [20]. These substructures are often identified by filters with names like PAINS (Pan-Assay Interference Compounds) [17] [20].

4. What computational tools can help identify these compounds early? Several computational tools have been developed to flag potential frequent hitters before experimental screening:

- ChemFH: An integrated online platform that uses machine learning to predict various types of interferents, including colloidal aggregators and reactive compounds [17].

- Hit Dexter: A set of machine learning models trained to predict frequent hitters in both target-based and cell-based assays [21].

- Aggregator Advisor: A tool specifically focused on identifying compounds likely to form colloidal aggregates [17].

5. My hit compound is inhibited by detergent. What does this mean? If your compound's inhibitory activity is significantly reduced or abolished by adding a small amount (e.g., 0.01%) of a non-ionic detergent like Triton X-100, it is a strong indicator that the compound acts through colloidal aggregation [16] [18] [20]. The detergent disrupts the aggregate particles, restoring enzyme activity.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing a Promiscuous Inhibitor in a Biochemical Assay

If you have a screening hit that you suspect is a false positive, this step-by-step guide helps you investigate.

- Objective: To experimentally determine if a hit compound is a promiscuous inhibitor acting via colloidal aggregation.

- Background: Colloidal aggregators form particles that non-specifically inhibit a wide range of enzymes. This behavior has a distinct experimental signature [16].

Experimental Protocol

Detergent Sensitivity Test

Enzyme Concentration Dependence

- Method: Repeat the inhibition assay at two or more different enzyme concentrations (e.g., 1 nM and 10 nM) [16].

- Interpretation: A decrease in apparent inhibition with increasing enzyme concentration suggests aggregator behavior. For a specific, well-behaved inhibitor, the percentage inhibition is largely independent of enzyme concentration within a reasonable range [16].

Steep Dose-Response Curves

Direct Observation of Particles

- Method: Use Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) to analyze your compound solution in the assay buffer.

- Interpretation: The observation of particles in the 30-1000 nm size range supports the aggregation hypothesis [16].

The following workflow visualizes the key decision points in this diagnostic process:

Guide 2: Integrating Computational Filters into Virtual Screening

This guide outlines how to use computational tools to triage a virtual screening library before costly experimental work begins.

- Objective: To remove likely frequent hitters from a compound library prior to pharmacophore-based virtual screening.

- Background: Computational models can predict compounds with high propensity for assay interference based on their chemical structure, acting as a valuable first-pass filter [17] [21].

Workflow Protocol

Prepare Compound Library

- Standardize the structures in your virtual library (e.g., neutralize charges, remove duplicates) to ensure data quality [17].

Apply Substructure Filters

Utilize Machine Learning Models

Manual Inspection

- Review the remaining compounds, paying special attention to those with highly electrophilic character, which can be calculated using Density Functional Theory (DFT) and is associated with lack of biological selectivity [19].

Proceed with Pharmacophore Screening

- Use the cleaned, triaged library for your pharmacophore-based virtual screening, leading to a hit list with a potentially higher proportion of true positives.

The workflow for this computational triage process is as follows:

Table 1: Prevalence of Frequent Hitters in a Large-Scale HTS Analysis

This data, derived from a study of 93,212 compounds screened in six different assays, shows how a small fraction of compounds are responsible for a large number of hits [20].

| Number of Assays in Which Compound Was Active | Number of Compounds | Percentage of Total Library |

|---|---|---|

| 6 | 362 | 0.39% |

| 5 | 785 | 0.84% |

| 4 | 915 | 0.98% |

| 3 | 1,220 | 1.31% |

| 2 | 4,689 | 5.03% |

| 1 | 12,077 | 12.96% |

| 0 (Inactive) | 73,164 | 78.49% |

Table 2: Key Experimental Signatures of Colloidal Aggregators

This table summarizes the key experimental observations that can help distinguish colloidal aggregators from specific inhibitors [16] [18] [20].

| Experimental Observation | Expected Result for a Colloidal Aggregator | Expected Result for a Specific Inhibitor |

|---|---|---|

| Inhibition in presence of non-ionic detergent (Triton) | Significant attenuation or abolition of inhibition | Little to no effect on inhibition |

| Effect of increasing enzyme concentration | Decrease in apparent inhibition | No significant change in percentage inhibition |

| Shape of the dose-response curve | Unusually steep curve | Standard sigmoidal curve |

| Observation by Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Particles present in the 30-1000 nm size range | No particles observed |

| Competitiveness of inhibition | Typically non-competitive | Can be competitive, non-competitive, or uncompetitive |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents for Identifying and Managing Promiscuous Inhibitors

| Reagent / Material | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Non-ionic Detergent (Triton X-100) | Disrupts colloidal aggregates; used to confirm aggregation as an inhibition mechanism [16] [18]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Can be used as an alternative to detergent in cell-based assays to sequester aggregators [16] [20]. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Instrument | Directly detects and measures the size of colloidal particles in compound solutions [16]. |

| Model Enzymes (e.g., β-lactamase, Chymotrypsin) | Well-characterized enzymes used in counter-screens to test for promiscuous inhibition across unrelated targets [16]. |

| Computational Tools (e.g., ChemFH, Hit Dexter) | Machine learning platforms for predicting frequent hitters from chemical structure prior to experimental screening [17] [21]. |

Quantitative Data on Virtual Screening Performance

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from benchmark studies comparing virtual screening approaches and their strategies for handling false positives.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Virtual Screening and Refinement Methods

| Method Category | Specific Method/Strategy | Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Screening Approach | Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening (PBVS) | Average Enrichment Factor | Outperformed DBVS in 14 out of 16 test cases | [22] |

| Docking-Based Virtual Screening (DBVS) | Average Enrichment Factor | Lower performance compared to PBVS | [22] | |

| False Positive Reduction | Multiple Receptor Conformations (MRC) with Intersection Selection | Success in Identifying High-Affinity Controls | Correctly identified all added high-affinity control molecules | [5] |

| Model Refinement | AF2 Recycling (Monomeric, non-AF2 models) | Model Improvement Rate (lDDT) | 81.25% (single sequence) to 100% (MSA) | [23] |

| AF2 Recycling (Multimeric, non-AF2 models) | Model Improvement Rate (lDDT) | 94% (single sequence) to 100% (MSA) | [23] | |

| Protein-Peptide Prediction | AF2-Multimer with Full-Length Input | Success Rate (Unbiased Benchmark) | 40% | [24] |

| AF2-Multimer with Fragment Scanning & MSA Mix | Success Rate (Unbiased Benchmark) | >90% | [24] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: Why does considering receptor flexibility in virtual screening often increase false positives, and how can I mitigate this?

- Problem: Each distinct conformational state of a protein receptor can bind compounds that are not true binders, generating unique lists of top-ranked hits. When multiple receptor conformations (MRCs) are used, the union of these lists can lead to an unmanageable number of false positives [5].

- Solution: Implement a consensus or intersection strategy. The hypothesis is that a true bioactive ligand will bind favorably to multiple conformations of the binding site.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Generate Multiple Receptor Conformations (MRCs): Use molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [5] or other sampling methods to generate a set of distinct, biologically relevant protein conformations.

- Perform Docking: Dock your virtual compound library against each conformation separately.

- Rank and Intersect: For each receptor conformation, generate a list of top-ranked compounds (e.g., top 100). The final list of high-confidence hits consists only of the compounds that appear in the top-ranked lists of all (or a majority) of the receptor conformations [5].

- Validation: This method has been shown to successfully distinguish high-affinity controls from low-affinity controls and decoys [5].

- Experimental Protocol:

FAQ 2: How can I refine initial protein models to correct for steric clashes and improve model quality?

- Problem: Initial protein structural models, even from high-accuracy predictors like AlphaFold2, may contain local steric clashes or backbone inaccuracies that limit their use in drug design.

- Solution: Use a quality-aware molecular dynamics (MD) refinement protocol.

- Experimental Protocol (Based on ReFOLD4):

- Obtain Local Quality Estimates: Use the per-residue predicted lDDT (pLDDT) score from AlphaFold2, which is often stored in the B-factor column of the PDB file [23].

- Apply Fine-Grained Restraints: In your MD simulation, apply harmonic positional restraints to all atoms of each residue. The key is to set the force constant of these restraints proportional to the residue's pLDDT score.

- Run MD Simulation: Perform the simulation using standard parameters (e.g., CHARMM force field, TIP3 water model, neutralization with ions, 298 K) [23]. This protocol is optimized for modest computational resources.

- Experimental Protocol (Based on ReFOLD4):

FAQ 3: How can I accurately identify the binding interface for a protein-protein interaction involving a disordered region?

- Problem: When using full-length protein sequences as input for AlphaFold2-Multimer, the success rate for predicting the correct structure of a complex with an intrinsically disordered ligand can be low (~40%) [24].

- Solution: Employ a fragment-scanning approach to pinpoint the interaction site before full complex prediction.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Define the Search Space: Identify the protein partner that contains the suspected disordered region.

- Generate Fragments: Divide the sequence of this partner into consecutive fragments of a fixed size (e.g., 100 amino acids) [24].

- Screen Fragments: Run AlphaFold2-Multimer predictions for the receptor paired with each individual fragment.

- Identify the Binding Fragment: The fragment that yields the model with the highest interface prediction score (ipTM) is highly likely to contain the true binding site. This strategy can successfully identify the correct region in up to 89% of cases [24].

- Refine the Model: Once the binding region is identified, a final, high-confidence model can be generated by using the defined fragment and combining multiple sequence alignment (MSA) strategies.

- Experimental Protocol:

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key software and computational tools essential for experiments dealing with steric clashes and model refinement.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Software Tools

| Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| GOLD | Docking software used for structure-based virtual screening, capable of handling protein flexibility [5]. | Identifying potential ligand candidates by docking compound libraries into flexible binding pockets [5]. |

| LigandScout/Catalyst | Software for creating pharmacophore models and performing pharmacophore-based virtual screening [22]. | Filtering large compound libraries to find molecules that match essential 3D chemical features for binding, often as a pre- or post-processing step for docking [22]. |

| AlphaFold2/AlphaFold-Multimer | Deep learning system for predicting protein tertiary and quaternary structures from amino acid sequences [23] [24]. | Generating initial structural models for targets with unknown structures, or refining existing models via its recycling function [23] [24]. |

| NAMD | Molecular dynamics simulation program used for refining protein structures and simulating biomolecular systems [23]. | Running refinement protocols (e.g., ReFOLD) to resolve steric clashes and improve local backbone geometry in protein models [23]. |

| ColabFold | A fast and user-friendly implementation of AlphaFold2 that includes a custom template function [23]. | Recycling and refining existing 3D models by feeding them back as custom templates into the AlphaFold2 inference loop [23]. |

Experimental Workflow Visualizations

Detailed View of the Model Refinement Process

Advanced Strategies to Reduce False Positives: Methodological Solutions

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of combining docking with pharmacophore filtering?

The primary advantage is a significant reduction in false positive rates. Traditional docking, which relies on scoring functions, often prioritizes compounds that score well in silico but do not bind in reality. By adding a pharmacophore filtering step, you enforce essential chemical complementarity with the target, ensuring that only poses which form key interactions (like specific hydrogen bonds or hydrophobic contacts) are advanced. This hybrid approach leverages docking's ability to generate plausible poses and pharmacophore's ability to define critical interaction patterns, leading to a more enriched and reliable list of candidate molecules [25].

Q2: My virtual screening results contain many compounds that fit the pharmacophore but have poor drug-like properties. How can I address this?

This is a common challenge. The solution is to integrate Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) profiling early in your screening pipeline. After the pharmacophore filtering step, subject the resulting hit compounds to in silico ADMET prediction. This allows you to filter out molecules with unfavorable properties, such as poor solubility or predicted toxicity, before they are selected for costly synthesis or experimental testing. Modern computational pipelines routinely combine pharmacophore screening, molecular docking, and ADMET analysis to prioritize leads with not only high binding potential but also a high probability of success in later development stages [26] [27].

Q3: After applying pharmacophore constraints, I get very few or no hits. What could be the reason?

This issue can stem from several sources:

- Overly Restrictive Pharmacophore Model: Your model may have too many features or the tolerance radii for each feature might be set too tightly. Solution: Re-evaluate your pharmacophore hypothesis. Consider if all features are absolutely essential. Start with a core set of critical interactions and slightly increase the tolerance radii to allow for more flexibility in ligand matching [25].

- Inadequate Conformational Sampling: The docking program may not have generated a pose where the ligand conformation aligns perfectly with your pharmacophore. Solution: Increase the conformational sampling parameters in your docking software or use a stochastic docking algorithm that generates more diverse poses [25].

- Incorrect Binding Site Preparation: The protein structure's protonation states or side-chain orientations might not be optimal for forming the expected interactions. Solution: Carefully prepare the protein structure, ensuring correct protonation states of key residues at physiological pH [28].

Q4: How do I validate the performance of my pharmacophore model before using it for screening?

The standard method is to calculate the Enrichment Factor (EF), which measures how well your model can identify true active compounds from a database that also contains decoys (inactive molecules). A high EF indicates good model performance [29]. Additionally, you can use ROC curve analysis (Receiver Operating Characteristic) to quantify the model's ability to distinguish between active and inactive compounds. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) provides a threshold-independent metric of model quality, with values closer to 1.0 indicating superior discriminatory power [27].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Experimental Issues

Problem: High False Positive Rate in Initial Docking Hits

Symptoms: A large number of top-ranked compounds from docking fail to show activity in subsequent experimental assays.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Limitations of scoring functions scoring functions often prioritize steric fit over chemical logic. | Check if highly scored poses lack key interactions with functional groups in the binding site (e.g., an unpaired hydrogen bond donor/acceptor). | Implement pharmacophore filtering as a post-docking step to remove poses that do not fulfill essential interaction constraints [25]. |

| Nonspecific compound binding | Analyze ligand structures for promiscuous motifs (e.g., pan-assay interference compounds, or PAINS). | Apply structural filtration rules to remove compounds with undesirable functional groups or properties [30]. |

| Insufficient structural constraints in docking | Review if the binding site is too open or solvent-exposed, allowing many different molecules to score well. | Use a multi-tiered docking approach (e.g., HTVS -> SP -> XP in Glide) with increasing rigor, and combine results with pharmacophore constraints [27]. |

Problem: Inconsistent Results During Pharmacophore-Based Screening

Symptoms: The same pharmacophore query yields different hit lists on different runs or with slightly modified parameters.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent preparation of the compound library | Ensure all ligands are prepared with the same protocol (e.g., ionization states, tautomers, stereochemistry). | Standardize ligand preparation using a consistent workflow (e.g., using Schrödinger's LigPrep or MOE) before screening [27]. |

| Poorly defined pharmacophore feature tolerances | Test the sensitivity of your results by slightly varying the tolerance radii of key pharmacophore features. | Optimize feature radii based on a known set of active and inactive compounds. Avoid overly strict tolerances that eliminate true actives [25]. |

| Software-specific interpretation of features | If possible, test the same pharmacophore model in different software platforms (e.g., LigandScout, MOE, Phase) to compare results. | Validate the model across platforms and understand the specific definitions and algorithms used by your chosen software [31]. |

Problem: Poor Correlation Between Computational Predictions and Experimental Binding Affinity

Symptoms: Compounds predicted to bind strongly show weak or no activity in biochemical assays.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate treatment of solvation and entropy | Docking scores are simplified and may not accurately reflect true binding free energy. | Employ more advanced post-docking scoring methods such as Molecular Mechanics with Generalized Born and Surface Area Solvation (MM-GBSA) to refine your predictions [26] [27]. |

| Rigid receptor approximation | The protein's flexibility and induced-fit effects upon ligand binding are not accounted for. | Perform Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations (e.g., 100-200 ns) on top hits to assess binding stability and account for protein flexibility [26] [31]. |

| Incorrect binding pose | The docked and pharmacophore-matched pose may not be the true binding mode. | Use composite scoring: rank compounds by a combination of docking score, pharmacophore fit score, and interaction energy from MD/MM-GBSA [25] [27]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: Implementing a Basic Pharmacophore Filtering Workflow

This protocol outlines the steps for using a pharmacophore model to filter docking results, as conceptualized in the research [25].

Principle: Docking generates aligned poses, and a structure-based pharmacophore model defines the essential interactions a ligand must make within the binding site. Filtering removes poses that are chemically complementary.

Procedure:

- Pose Generation: Run a molecular docking program (e.g., GOLD, Glide) on your compound library. Configure the software to output a large number of poses per ligand (e.g., 10-50) without heavy reliance on the native scoring function for ranking.

- Pharmacophore Model Definition: Using the target's 3D structure (with or without a co-crystallized ligand), define a set of essential pharmacophore features. These typically include:

- Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD)

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA)

- Hydrophobic (HY)

- Aromatic Ring (AR)

- Positively/Negatively Charged groups (PI/NI)

- Feature Placement: Place these features in 3D space based on complementary functional groups in the protein's binding site. For example, place an HBA feature near a key histidine residue that can act as a hydrogen bond donor.

- Filtering: Process the file containing all saved docking poses. For each pose, check if its atoms satisfy the spatial and chemical constraints of all mandatory pharmacophore features. Poses that fail to match one or more critical features are discarded.

- Ranking: Rank the filtered hits based on a combination of their docking score and their pharmacophore fit score.

Protocol: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Model Generation

This protocol describes the generation of a Shared Feature Pharmacophore (SFP) model from multiple protein-ligand complexes, a method employed in recent studies [31].

Principle: By analyzing several ligand-bound structures of the same target, a consensus pharmacophore model can be built that captures the common, essential interactions shared across different chemotypes, making it more robust.

Procedure:

- Structure Retrieval and Preparation: Obtain high-resolution crystal structures of your target protein in complex with different active ligands from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Prepare each structure by adding hydrogens, correcting protonation states, and optimizing hydrogen bonds.

- Individual Pharmacophore Generation: For each protein-ligand complex, use structure-based pharmacophore software (e.g., LigandScout) to automatically generate a pharmacophore model. This model will identify features like HBD, HBA, and HY regions based on the observed ligand-protein interactions.

- Model Alignment and Comparison: Align the individual pharmacophore models based on the 3D structure of the protein. The software will identify features that are common across all or most of the models.

- Consensus (SFP) Model Generation: Create a final Shared Feature Pharmacophore model that includes only the overlapping features from the individual models. This model represents the minimal set of interactions necessary for binding.

- Model Validation: Validate the model's ability to distinguish known active compounds from decoys using enrichment calculations or ROC curve analysis [27].

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

The following table details key computational tools and resources used in the featured experiments and this field of research.

| Item Name | Type/Supplier | Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Software Suite (Chemical Computing Group) | Used for ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, molecular docking, and molecular dynamics simulations [26]. |

| LigandScout | Software (Inte:Ligand) | Enables advanced structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore model generation, and performs virtual screening [31]. |

| Schrödinger Suite | Software Suite (Schrödinger) | Provides an integrated platform for protein preparation (Protein Prep Wizard), pharmacophore modeling (Phase), molecular docking (Glide), and energy calculations (MM-GBSA) [27]. |

| ZINC Database | Online Compound Library | A curated collection of commercially available chemical compounds, often used as a source for virtual screening libraries [25]. |

| DOCK3.7 | Docking Software (Academic) | A widely used academic docking program for large-scale virtual screening of ultra-large chemical libraries [28]. |

| ELIXIR-A | Software Tool (Open Source) | A Python-based tool for refining and comparing pharmacophore models from multiple ligands or receptors, aiding in the identification of the best set of pharmacophores [29]. |

| Enamine MAKE-ON-DEMAND | Virtual Compound Library | A pragmatically accessible virtual library of billions of molecules that can be synthesized on demand, used for ultra-large virtual screening [28]. |

Integration of Machine Learning to Predict Docking Scores and Accelerate Screening

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

This technical support resource addresses common challenges researchers face when integrating machine learning (ML) with pharmacophore-based virtual screening, with a specific focus on mitigating false positives.

FAQ 1: How can I reduce false positives when my ML model performs well on training data but poorly in prospective screening?

Problem: Your model has high training accuracy but selects an excessive number of false positives during virtual screening of new chemical libraries.

Solutions:

- Apply a Consensus Scoring Strategy: Screen your library against multiple, distinct conformations of the target receptor. Select only the compounds that are top-ranked across all the receptor models. This strategy leverages the concept that a true binder typically fits favorably to different conformations of the binding site, while false positives are often only highly ranked in a single conformation [5].

- Implement Conformal Prediction: Use the conformal prediction (CP) framework with your ML classifier. The CP framework allows you to control the error rate of predictions. By setting a significance level (e.g., ε=0.1), you can define a "virtual active" set with a guaranteed maximum percentage of incorrectly classified compounds, thus filtering out many false positives before they reach the docking stage [32].

- Re-evaluate Your Training Data Splitting: Avoid random splits of your data for training and testing. Instead, split the data based on compound Bemis-Murcko scaffolds. This ensures that the model is tested on chemotypes that differ from those used in training, providing a more realistic assessment of its screening capability and generalizability to novel compounds [33].

FAQ 2: What is the most efficient way to apply ML to screen ultra-large, multi-billion compound libraries?

Problem: Classical molecular docking is computationally infeasible for libraries containing billions of molecules.

Solutions:

- Adopt a Two-Stage ML-Docking Workflow: Use a fast ML classifier as a pre-filter to drastically reduce the library size before any docking occurs.

- Stage 1 - ML Pre-screening: Train a classification algorithm (e.g., CatBoost) on molecular fingerprints (e.g., Morgan fingerprints) using docking scores from a smaller, representative subset (e.g., 1 million compounds) of the large library. Apply this model to predict and select a "virtual active" set from the multi-billion compound library [32].

- Stage 2 - Docking Validation: Perform molecular docking only on the significantly reduced "virtual active" set identified by the ML model. This protocol can reduce the computational cost of structure-based virtual screening by more than 1,000-fold [33] [32].

- Algorithm and Descriptor Selection: For optimal balance between speed and accuracy, use the CatBoost classifier with Morgan2 fingerprints. This combination has been shown to achieve high precision while requiring the least computational resources for training and prediction [32].

FAQ 3: How can I integrate pharmacophore constraints with an ML-based docking prediction model?

Problem: You want to ensure that ML-predicted hits not only have a favorable docking score but also satisfy key pharmacophoric features essential for binding.

Solutions:

- Sequential Filtering Protocol:

- Pharmacophore Filter: First, screen your initial compound database using a well-validated pharmacophore model. This model, which encapsulates steric and electronic features essential for binding, will filter out compounds lacking these critical features [34] [35].

- ML Scoring Filter: Next, apply your ML model trained to predict docking scores to the pharmacophore-filtered subset. This prioritizes compounds that both match the pharmacophore and are predicted to have high affinity [33].

- Use Pharmacophore-Based Fingerprints: Employ a pharmacophore-based fingerprint, such as the Extended Reduced Graph (ErG), as the molecular representation for your ML model. This directly encodes the pharmacophoric features of a molecule (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions) and has proven effective in creating models that can assign compounds to specific target classes based on these features [36] [37].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing Consensus Docking to Reduce False Positives

This methodology is designed to select true ligands and minimize false positives when receptor flexibility is considered [5].

- Generate Multiple Receptor Conformations (MRCs): Use molecular dynamics (MD) simulations or available crystal structures to generate an ensemble of distinct conformations of your target protein.

- Docking Screen: Dock your entire compound library (including known high-affinity and low-affinity controls) separately into each receptor conformation in the MRCs.

- Rank and Compare: Generate a ranked list of top-scoring compounds (e.g., top 100) for each individual receptor conformation.

- Identify Intersection Compounds: Select only the compounds that appear in the top-ranked lists across all (or a defined majority) of the receptor conformations. These intersection compounds are your high-confidence hits.

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Guided Docking Screen of Ultra-Large Libraries

This workflow enables virtual screening of billion-compound libraries at a modest computational cost [32].

- Data Preparation & Docking: Select a random subset (e.g., 1 million compounds) from your ultra-large library. Dock these compounds against your target to generate docking scores.

- Model Training: Define an activity threshold (e.g., top 1% of docking scores) to create a binary classification. Train an ensemble of machine learning classifiers (e.g., five CatBoost models) using molecular fingerprints (e.g., Morgan2) of the 1-million compound set and their class labels.

- Conformal Prediction & Calibration: Use a separate calibration set to calculate nonconformity scores and apply the Mondrian conformal prediction framework.

- Virtual Screening & Selection: Apply the trained conformal predictor to the entire ultra-large library. Using a predefined significance level (ε), the framework will output a "virtual active" set. This set is guaranteed to have an error rate below ε and will be orders of magnitude smaller than the original library.

- Experimental Validation: Perform molecular docking on the reduced "virtual active" set and select top-ranking compounds for synthesis and biological testing.

The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies on ML-accelerated screening.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of ML-Accelerated Virtual Screening

| Metric | Reported Performance | Context and Methodology |

|---|---|---|

| Speed Acceleration | >1,000-fold [33] [32] | ML-based prediction of docking scores versus classical docking-based screening. |

| Library Size Reduction | ~90% (234M to 25M compounds) [32] | Using CP to pre-filter an ultralarge library before docking. |

| Sensitivity (Recall) | 0.87 - 0.88 [32] | CP workflow identified 87-88% of true virtual actives while docking only ~10% of the library. |

| Model Accuracy | 93.8% [36] | Accuracy of a pharmacophore-fingerprint (ErG) based multi-class model for classifying E3 ligase binders. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for ML-Guided Virtual Screening

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Experiment | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Docking Software | Predicts binding pose and affinity of a ligand to a protein target. | Smina [33], GOLD [5]. Crucial for generating training data for the ML model. |

| Chemical Databases | Source of compounds for virtual screening. | ZINC [33], Enamine REAL Space [32]. Provide ultra-large libraries of purchasable compounds. |

| Molecular Fingerprints | Numerical representation of chemical structure used as input for ML models. | Morgan fingerprints (ECFP4) [33] [32], Extended Reduced Graph (ErG) [36] [37]. ErG is a pharmacophore-based fingerprint. |

| Machine Learning Classifiers | Algorithm that learns to predict docking scores or activity classes from fingerprints. | CatBoost [32], XGBoost [36], Deep Neural Networks [32]. CatBoost offers a good speed/accuracy balance. |

| Conformal Prediction Framework | Provides a mathematically rigorous measure of confidence for ML predictions, controlling error rates. | Mondrian Conformal Predictors [32]. Key for managing false positives and defining the size of the "virtual active" set. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Creates abstract models of steric and electronic features essential for binding. | Used as a primary filter or to generate pharmacophore-based fingerprints [34] [36] [35]. |

Workflow Visualization

Integrated Screening Workflow for False Positive Reduction

Logic of Consensus Docking Strategy

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental definition of a structure-based pharmacophore model? A structure-based pharmacophore model is an abstract representation of the steric and electronic features that are necessary for a molecule to achieve optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target. It is generated directly from the three-dimensional structure of a macromolecule, typically a protein, often in complex with a ligand. These models represent key chemical functionalities—such as hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrophobic areas (H), and ionizable groups—as geometric entities like spheres, planes, and vectors to define the essential interaction points for biological activity [7].

Q2: What are the most common features in a structure-based pharmacophore, and how are they represented? The most common features include [7]:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA): Represented as a vector projecting from an electronegative atom (e.g., oxygen).

- Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD): Represented as a vector projecting from a hydrogen atom attached to an electronegative atom.

- Hydrophobic (H): Represented as a sphere centered on a carbon atom in a non-polar region.

- Positive/Negative Ionizable (PI/NI): Represented as a sphere centered on an atom capable of holding a formal charge.

- Aromatic (AR): Represented as a ring or plane.

- Exclusion Volumes (XVOL): Represented as spheres that define regions in space occupied by the protein, which the ligand must avoid.

Q3: What is the primary cause of false positives in pharmacophore-based virtual screening? The primary cause is insufficient selectivity in the initial pharmacophore hypothesis. A model that is too generic or lacks critical spatial constraints may match compounds that fit the pharmacophore's geometric and chemical criteria but cannot actually bind to the target protein due to unaccounted-for steric clashes or subtle electronic mismatches [7] [38]. This often occurs when the model does not adequately represent the shape and steric restrictions of the entire binding pocket.

Q4: How can exclusion volumes be used to reduce false positive rates? Exclusion volumes are a direct method to incorporate the shape of the binding pocket into the model. They define "forbidden" regions in space that are occupied by the protein's atoms. During virtual screening, any compound whose atoms intrude into these exclusion volume spheres is penalized or filtered out. This directly addresses steric incompatibility and is a crucial tool for improving the selectivity of a pharmacophore model and reducing false positives [7].

Q5: What validation metrics are used to assess a model's ability to distinguish active from inactive compounds before screening? The standard method involves using a decoy set containing known active compounds and property-matched inactive molecules (e.g., from the DUD-E database). The model is used to screen this set, and its performance is evaluated using [39]:

- Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve: A plot of the true positive rate against the false positive rate.

- Area Under the Curve (AUC): A value of 1.0 indicates perfect discrimination, while 0.5 indicates a random classifier. An excellent model typically has an AUC value above 0.9 [39].

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Measures the concentration of active compounds at the top of the screening list. For example, an EF of 10.0 at a 1% threshold means that actives are 10 times more concentrated in the top 1% of results than in the entire database [39].

Q6: Beyond exclusion volumes, what advanced strategies can improve model selectivity? Advanced strategies include:

- Enrichment-Driven Optimization: Tools like BR-NiB (Brute Force Negative Image-Based Optimization) or the O-LAP algorithm can iteratively refine a model's features and their positions based on its performance on a training set of known actives and inactives. This process optimizes the model specifically for high enrichment [38].

- Shape-Focused Models: Algorithms like O-LAP generate cavity-filling models by clustering overlapping atoms from docked active ligands. These models prioritize the overall shape and electrostatic potential complementarity to the binding site, which can be more selective than feature-based models alone [38].

- Integration with Machine Learning: ML classifiers can be trained on chemical descriptors of known active and inactive compounds to further filter virtual screening hits, adding another layer of selectivity [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High False Positive Rate in Virtual Screening

Issue: Your pharmacophore model retrieves a large number of hits during virtual screening, but subsequent molecular docking or experimental testing shows a very low confirmation rate.

Solutions:

- Incorporate Exclusion Volumes: Add exclusion volumes to your model based on the protein's binding site structure. This is the most direct way to filter out compounds that sterically clash with the protein [7].

- Refine Feature Selection: Re-evaluate the generated features. Remove redundant or non-essential features that may not critically contribute to binding affinity. Prioritize features that interact with key conserved residues in the binding site [7].

- Optimize with a Training Set: If a set of known active and inactive compounds is available, use enrichment-driven optimization (e.g., with O-LAP) to adjust feature positions, types, and weights to maximize the model's ability to separate actives from inactives [38].

- Apply a Shape Constraint: Use the entire binding cavity to generate a shape-focused pharmacophore model (e.g., a negative image-based model) and use it to rescore or pre-filter the results from your initial feature-based screening. This ensures hits not only match the chemical features but also the overall shape of the pocket [38].

Table 1: Strategies for Mitigating False Positives in Pharmacophore Screening

| Strategy | Mechanism | Tools/Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Exclusion Volumes | Defines steric constraints from the protein, filtering compounds that cause clashes. | LigandScout, structure-based modelers [7]. |

| Enrichment Optimization | Iteratively refines the model to improve its discrimination of active vs. inactive compounds. | O-LAP, BR-NiB [38]. |

| Shape-Focused Rescoring | Evaluates the overall shape and electrostatic complementarity of hits to the binding cavity. | ShaEP, R-NiB (Negative Image-Based Rescoring) [38]. |

| Machine Learning Filtering | Uses trained classifiers to predict activity based on chemical descriptors, post-screening. | PaDEL-Descriptors, ML classifiers (e.g., from Scikit-learn) [40]. |

Problem: Poor Validation Metrics in Model Assessment

Issue: During validation with a decoy set, your model shows a low AUC value or a low enrichment factor, indicating it cannot reliably distinguish active compounds.

Solutions:

- Verify Input Data Quality: Ensure the source protein-ligand complex structure is of high resolution and the ligand's binding pose is biologically relevant. The quality of the input structure directly dictates the quality of the pharmacophore model [7].

- Check Feature Conservation: Analyze if the selected pharmacophore features are conserved across multiple known active ligands or different protein-ligand complex structures. A feature that is not conserved may not be critical for binding [7].

- Adjust Feature Tolerance: Increase the tolerance radii (the size of the feature spheres) slightly to account for minor conformational flexibility, but avoid making them too large, which reduces selectivity.

- Review Decoy Set: Confirm that the decoy set (e.g., from DUD-E) is appropriately matched to the active compounds in terms of molecular weight and other physicochemical properties but is topologically distinct to ensure a fair validation [39] [38].

Problem: Low Hit Rate or Overly Stringent Screening

Issue: Your pharmacophore model retrieves very few or no hits from a large database, potentially missing valid active compounds.

Solutions:

- Relax Feature Constraints: Remove the least critical feature from your hypothesis and re-run the screening. Alternatively, increase the tolerance radii of the features.

- Review Exclusion Volumes: Excessively large or misplaced exclusion volumes can over-constrain the model. Visually inspect the model within the binding pocket to ensure exclusion volumes accurately represent protein atoms.

- Implement Multiple Hypotheses: If the binding site can accommodate ligands in different ways, generate several alternative pharmacophore models (multiple hypotheses) and screen the database against each one independently [7].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Standard Workflow for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow for creating and applying a structure-based pharmacophore model, integrated with key steps for managing false positives.

Graph 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling and Optimization Workflow

Core Protocol: Generating and Validating a Model

This protocol is based on methodologies detailed in multiple studies [39] [7].

1. Protein Structure Preparation:

- Source: Obtain a high-resolution 3D structure of the target protein, preferably in complex with a bioactive ligand, from the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

- Preparation Steps:

- Add hydrogen atoms and correct protonation states of residues (especially in the binding site) at physiological pH.

- Remove crystallographic water molecules unless they are known to mediate key interactions.

- Perform energy minimization to relieve steric clashes and ensure correct stereochemistry.

2. Binding Site Definition and Pharmacophore Feature Generation:

- Define Site: The binding site can be defined as the region surrounding a co-crystallized ligand.

- Generate Features: Use software like LigandScout to automatically interpret the protein-ligand interactions and convert them into pharmacophore features. The software identifies features like HBA, HBD, H, and PI/NI based on the spatial arrangement and chemical nature of the interacting atoms [39].

- Feature Selection: Manually review and curate the automatically generated features. Retain those that represent strong, conserved interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds with key catalytic residues, crucial hydrophobic contacts) and remove redundant or weak features.

3. Model Validation (Critical Step):

- Prepare Test Set: Compile a set of 10-30 known active compounds and a large set (e.g., 1000-5000) of property-matched decoy molecules. The DUD-E database is a standard source for such decoys [39] [38].

- Run Validation Screening: Use the pharmacophore model as a query to screen the combined set of actives and decoys.

- Calculate Performance Metrics:

- AUC-ROC: Calculate the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve. An AUC > 0.7 is acceptable, >0.8 is good, and >0.9 is excellent [39].

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Calculate the EF at 1% of the screened database. For example, a study on XIAP inhibitors achieved an EF1% of 10.0, indicating high early enrichment [39].

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics from a Validated XIAP Inhibitor Pharmacophore Model [39]

| Metric | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve) | 0.98 | Excellent model; 98% chance of ranking a random active compound higher than a random decoy. |

| Enrichment Factor (EF) at 1% | 10.0 | In the top 1% of screening results, active compounds are 10 times more concentrated than in the entire database. |

| Number of Actives in Test Set | 10 | The model was validated against 10 known active XIAP antagonists. |

| Number of Decoys in Test Set | 5199 | A large set of decoys was used to ensure statistical robustness. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Databases for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Application in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| RCSB PDB | Database | Repository of experimentally determined 3D protein structures. | Source of the initial target protein structure (e.g., PDB ID: 5OQW for XIAP) [39]. |

| LigandScout | Software | Advanced molecular design software for structure- and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling. | Generation and visualization of pharmacophore features from protein-ligand complexes [39]. |

| ZINC Database | Database | Curated collection of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. | Source of natural compounds or drug-like molecules for pharmacophore-based screening [39] [40]. |

| DUD-E | Database | Database of Useful Decoys: Enhanced. Contains decoy molecules for validation. | Provides property-matched decoys to validate the model's ability to distinguish actives from inactives [39] [38]. |

| O-LAP | Software | Algorithm for generating shape-focused pharmacophore models via graph clustering. | Creates cavity-filling models to improve screening selectivity and reduce false positives [38]. |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Software | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints from chemical structures. | Generates features for machine learning-based filtering of screening hits [40]. |

| AutoDock Vina/PLANTS | Software | Molecular docking programs. | Used for flexible docking of hits for post-screening validation and pose analysis [40] [38]. |

For researchers developing ligand-based models, public databases are indispensable sources of experimentally validated protein-ligand interaction data. These resources provide the foundational information for building predictive models in virtual screening campaigns.

Table 1: Primary Databases for Ligand-Based Model Development

| Database Name | Primary Content & Specialization | Key Statistics | Data Sources & Licensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| BindingDB [41] | Measured binding affinities of drug-like small molecules against protein targets. | - 3.2M binding data points- 1.4M Compounds- 11.4K Protein Targets [41] | Data extracted from scientific literature and patents; provided under Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License [41]. |

| ChEMBL [2] | Bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, containing binding, functional, and ADMET information. | (Imported into BindingDB, a major source of curated data) [41] | Data provided under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License [41]. |

| Pocketome [42] | An encyclopedia of crystallographically observed conformations of binding pockets in complex with diverse chemicals. | - ~2,050 binding site ensembles- Covers major target families (GPCRs, Kinases, Nuclear Receptors) [42] | Derived from Protein Data Bank (PDB) and UniProt Knowledgebase [42]. |

| PDBbind [43] | Experimentally measured binding affinity data for biomolecular complexes housed in the PDB. | Used to train and test computational models (e.g., 3,875 complexes in one curated set) [43] | Linked to the primary PDB structure repository. |

FAQs: Data Curation and Preparation

1. How can I assess and improve the quality of data sourced from public databases for my model? The quality of your model is directly dependent on the quality of the input data. Begin by applying stringent filtering based on experimental conditions. For binding affinity data (e.g., Ki, IC50), prioritize measurements obtained under consistent and physiologically relevant conditions (e.g., pH, temperature) [41]. Furthermore, check for chemical structure integrity. Ensure structures are standardized, with correct valence, defined stereochemistry, and removal of counterions and salts. Utilize the curated subsets provided by databases like BindingDB, which contain over 1.5 million data points meticulously curated by experts, to start with a higher-quality foundation [41].

2. What are the best practices for selecting an appropriate benchmark decoy set to test my model's performance? The choice of decoy set is critical for a realistic assessment of your model's ability to distinguish true actives from inactives. Avoid using decoys that are trivially different from actives. Instead, employ a strategy that generates "compelling decoys" – molecules that are individually matched to active complexes and are challenging to distinguish, forcing the model to learn the nuanced features of true binding [2]. This approach prevents model overfitting and more accurately reflects the challenge of a real virtual screen, where the vast majority of compounds are plausible but inactive [2].

3. My model performs well on training data but poorly in prospective virtual screening. What might be the cause? This is a classic sign of overfitting or dataset bias. This often occurs when a model is trained on a limited set of examples and cannot generalize to new chemical scaffolds. To address this:

- Expand Structural Diversity: Incorporate data from ensembles of protein-ligand structures, such as those provided by the Pocketome, to expose your model to the natural conformational variability of binding sites [42].

- Analyze Applicability Domain: Ensure your screening library falls within the chemical space covered by your training data. Models fail when applied to "out-of-distribution" compounds [2].

- Integrate Structure-Based Insights: If possible, use 3D ligand-based methods that project ligand properties into specific spatial locations, which are less biased toward known chemical scaffolds and better for "scaffold-hopping" than 2D similarity measures [42].

FAQs: Model Development and Validation

4. What are the main computational approaches for building ligand activity models? There are two primary types of 3D models you can build, each with its own strengths.

- Pocket-Based Models (Structure-Based): These models rely on the 3D structures of binding pockets from sources like the Pocketome. They evaluate new ligands by computationally docking them and scoring their complementarity to the pharmacophore features of the pocket. They do not require known ligands to start, making them suitable for novel targets [42].

- Ligand Property-Based Models (Ligand-Based): These models use the 3D structures of known active ligands in their bound conformations. They define the optimal spatial distribution of pharmacophore features required for binding and evaluate new compounds by their 3D similarity to this template. These methods are excellent for scaffold-hopping as they focus on interaction patterns rather than chemical graphs [42].

5. How do I rigorously validate my ligand-based model before prospective use? Robust validation is non-negotiable. Move beyond simple random splits of your data.

- Use Temporal Splits: A more realistic validation involves training your model on data published before a certain date and testing it on data published after. BindingDB facilitates this by providing publication and curation dates for measurements [41].

- Benchmark on Challenging Sets: Test your model's performance on external benchmark datasets designed to be difficult, such as those containing the "compelling decoys" mentioned earlier [2].

- Employ Multiple Metrics: Don't rely on a single metric. Use a composite of metrics including Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) to measure overall enrichment, and also examine the hit rate in the top-ranked compounds. A good model should achieve a high AUC and a high proportion of true actives in its top ranks [42].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: High False Positive Rate in Virtual Screening

Symptoms

- A high number of top-ranked compounds from a virtual screen show no activity in subsequent experimental assays.

- The observed hit rate is significantly lower than the expected hit rate based on model confidence scores.

Investigation and Resolution Steps

1. Interrogate Decoy Set Quality: A major cause of high false positives is an inadequate decoy set used during model training or validation. If the decoys are trivially different from actives (e.g., lacking key functional groups), the model will not learn the true, complex features of binding and will fail in real screens [2].

- Solution: Adopt a rigorous decoy selection strategy like the D-COID method, which aims to generate highly compelling decoy complexes that are individually matched to available active complexes, ensuring the model is trained on a challenging and realistic task [2].

2. Check for Model Overfitting: The model may have memorized the training data without learning generalizable rules.

- Solution: Validate your model using a temporal split (training on older data, testing on newer data) rather than a random split. This better simulates a prospective screening scenario. Furthermore, ensure your training set encompasses a diverse range of chemical scaffolds and target conformations to improve generalizability [41] [42].

3. Inspect Binding Pocket Conformation: For structure-aware models, using a single, rigid protein structure can lead to false positives for compounds that would be sterically or electrostatically incompatible with other relevant pocket conformations.

- Solution: Utilize an ensemble of pocket conformations from resources like the Pocketome. Docking against multiple representative structures can help identify compounds whose binding is sensitive to minor structural changes, which are less promising leads [42].

4. Integrate Machine Learning-Based Re-scoring: Traditional scoring functions can be misled by specific, favorable interactions that are not sufficient for overall high-affinity binding.

- Solution: Implement a machine learning classifier like vScreenML as a post-docking filter. Such classifiers, trained on challenging decoys, can more effectively distinguish true actives from false positives by considering nonlinear interactions and complex patterns that traditional functions miss [2] [43].

Problem 2: Low Hit Rate and Inability to Find Novel Scaffolds

Symptoms

- The model successfully identifies known chemotypes but fails to find new chemical scaffolds (i.e., poor at "scaffold-hopping").

- All top-ranked compounds are structurally very similar to the training set actives.

Investigation and Resolution Steps

1. Evaluate the 3D Nature of the Pharmacophore Model: If your model is primarily based on 2D chemical similarity, it is inherently biased toward recovering compounds that are structurally similar to the training set.

- Solution: Shift to a 3D ligand property-based model. These methods represent ligands as 3D fields of pharmacophore features, free from the constraints of the underlying chemical graph. This makes them more realistic and suitable for scaffold-hopping, as they focus on the spatial arrangement of interactions rather than the specific atoms creating them [42].

2. Analyze the Diversity of the Training Set: The model cannot learn what it has never seen. If the training data is composed of a few, highly similar chemical series, the model's applicability domain will be narrow.

- Solution: Actively curate a more diverse training set. Augment your data by incorporating ligands from different sources like ChEMBL and BindingDB that bind to the same target but belong to distinct structural classes. The use of diverse data is critical for expanding the model's recognition capabilities [41] [42].

3. Leverage Multiple Pocket Conformations: Different chemical scaffolds often bind by stabilizing distinct conformations of the target protein. A model based on a single protein structure may be optimized for only one specific scaffold.

- Solution: As with reducing false positives, using a pocket ensemble from the Pocketome can help. Different scaffolds may be best identified using different representative structures from the ensemble, increasing the chances of finding novel chemotypes [42].

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Resources for Ligand-Based Modeling

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Model Development |

|---|---|---|

| BindingDB [41] | Database | Source for curated binding affinity and small molecule bioactivity data to train and validate models. |

| ChEMBL [41] | Database | Large-scale repository of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, used as a data source. |

| The Pocketome [42] | Database | Provides ensembles of binding pocket conformations for incorporating target flexibility into models. |

| PDBbind [43] | Database | Provides a refined set of protein-ligand complexes with binding affinity data for benchmarking. |

| LigPlot+ [44] | Visualization Tool | Generates schematic 2D diagrams of protein-ligand interactions to visualize and analyze binding modes. |

| vScreenML [2] | Software/Classifier | A machine learning classifier trained to reduce false positives in structure-based virtual screening. |

| D-COID Dataset [2] | Training Dataset | A strategy for building a dataset of "compelling decoys" to train robust ML classifiers for virtual screening. |

| MedusaNet [43] | Software/Scoring | A 3D Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model used to predict the stability of protein-ligand complexes. |

Advanced Experimental Protocol: Building a vScreenML-like Classifier

This protocol outlines the methodology for creating a machine learning classifier to reduce false positives in virtual screening, based on the approach described in [2].

1. Objective: To train a general-purpose binary classifier (vScreenML) that can effectively distinguish between active and "compelling decoy" protein-ligand complexes.

2. Materials and Data Sources:

- Active Complexes: Source experimentally determined protein-ligand structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Filter these to include only ligands that adhere to the desired physicochemical properties for your drug discovery campaign (e.g., molecular weight, logP) [2].

- Decoy Complexes: Generate a set of "compelling decoys" using the D-COID strategy. This involves creating decoy complexes that are individually matched to the active complexes and are difficult to distinguish based on simple criteria, ensuring the model learns non-trivial aspects of molecular recognition [2].

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Data Compilation and Preparation.

- Compile a set of active complexes from the PDB, ensuring they meet your ligand property criteria.

- For each active complex, generate a set of matched decoy complexes using a docking program to pose the decoys in the binding site.

- Step 2: Feature Extraction.

- For each complex (both active and decoy), calculate a set of features that describe the protein-ligand interaction. These may include:

- Interaction fingerprints: Hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, ionic interactions.

- Geometric descriptors: Buried surface area, shape complementarity.

- Energetic terms: Components from traditional scoring functions (e.g., vdW, electrostatics).

- For each complex (both active and decoy), calculate a set of features that describe the protein-ligand interaction. These may include:

- Step 3: Model Training.

- Use the XGBoost framework, a powerful and efficient implementation of gradient-boosted trees, to train the classifier.

- The model is trained on the labeled dataset where active complexes are the positive class and compelling decoy complexes are the negative class.

- Step 4: Validation.

- Perform rigorous retrospective benchmarks to evaluate the classifier's performance against other scoring functions.

- The key metric is the enrichment of true actives in the top-ranked compounds compared to traditional methods.

4. Prospective Application:

- In a new virtual screening campaign, the trained

vScreenMLclassifier is used to re-score the output poses from a molecular docking run. The top-ranked compounds by the classifier are selected for experimental testing [2].

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the most common causes of false positives after the initial pre-screening filters? False positives often persist due to an overestimation of conformational flexibility during the 3D alignment step or an inability of the 2D pre-filters to account for specific stereochemical constraints [8]. Furthermore, if the pre-filtering steps are not "lossless," they may mathematically discard molecules that could actually fit the query, but this is often accepted for the benefit of higher screening efficiency [8].