Signal Processing for Cancerous DNA Pattern Recognition: From Genomic Signals to Clinical Diagnostics

This article provides a comprehensive overview of signal processing (SP) methodologies for identifying cancerous patterns in DNA sequences.

Signal Processing for Cancerous DNA Pattern Recognition: From Genomic Signals to Clinical Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of signal processing (SP) methodologies for identifying cancerous patterns in DNA sequences. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of genomic SP, detailing key techniques like Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) and Fourier analysis for feature extraction. The scope extends to advanced applications integrating machine and deep learning for methylation analysis and multi-cancer classification, alongside critical troubleshooting for data noise and computational challenges. A validation framework comparing SP methods with established sequencing technologies is presented, synthesizing performance benchmarks to guide tool selection and future biomedical research directions.

The Foundation of Genomic Signals: From DNA Sequence to Analysable Data

Core Concepts of Genomic Signal Processing

Genomic Signal Processing (GSP) is an interdisciplinary engineering discipline that integrates the theory and methods of signal processing with the applications arising from high-throughput technologies in biomedical research [1]. In the context of cancer research, GSP provides a powerful framework for converting DNA sequence data into numerical values, enabling the application of digital signal processing (DSP) techniques to identify patterns and features associated with carcinogenesis [2] [3]. This approach allows researchers to investigate the complex structural and functional relationships among genes and proteins in cancerous tissues, with the potential to revolutionize molecular diagnostics and personalized cancer treatment strategies [1].

Central to GSP is the transformation of nucleotide sequences into numerical data, which facilitates the extraction of key spectral features—most notably the period-3 property observed in protein coding regions [3]. These techniques enable the prediction and validation of gene locations by differentiating the exonic (coding) and intronic (non-coding) regions, thereby advancing our understanding of genetic function and regulation in cancer biology [3]. The evolution from traditional transform-based methods to adaptive filtering and machine learning approaches has significantly enhanced the accuracy of gene prediction and broadened applications in cancer diagnostics and personalized medicine [3].

Key Numerical Representations and Processing Methods

DNA Sequence to Signal Conversion

The fundamental first step in GSP analysis involves mapping DNA sequences to numerical representations. One of the most established methods is the Voss representation, which employs four binary indicator vectors to denote the presence of each nucleotide type at specific locations within a DNA sequence [2]. Given a DNA sequence α, its corresponding four-dimensional DNA signal is computed as follows:

Xˆ1[i] = 1 if X[i] = A, 0 otherwiseXˆ2[i] = 1 if X[i] = G, 0 otherwiseXˆ3[i] = 1 if X[i] = C, 0 otherwiseXˆ4[i] = 1 if X[i] = T, 0 otherwise[2]

After converting DNA sequences to numerical signals, the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) is applied to compute the power spectral density (PSD), which describes how the power of a signal is distributed over frequency [2]. In genomic terms, the PSD serves as a descriptor of the nucleotide patterns that may be present within the DNA sequence, with specific frequency components indicating biologically significant regions such as protein-coding exons [2] [3].

Table 1: Key Numerical Representation Methods in Genomic Signal Processing

| Method | Description | Key Applications in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|

| Voss Representation | Four binary indicator sequences for A, T, G, C | Fundamental encoding for subsequent spectral analysis |

| Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) | Converts genomic signals to frequency domain | Identification of periodic patterns like period-3 in exons |

| Power Spectral Density (PSD) | Describes power distribution over frequencies | Quantification of dominant patterns in cancer-related genes |

| Digital Filters (e.g., Comb Notch) | Selective frequency component isolation | Separation of coding and non-coding regions in cancer genomes |

| Walsh Hadamard Transform (WHT) | Binary orthogonal transformation | Alternative spectral analysis of mutational patterns |

Advanced Processing Techniques

Recent advances in GSP include the utilization of specialized filters that isolate characteristic frequencies associated with exonic regions, thereby improving the identification of protein-coding segments [3]. Integrated approaches combining recursive adaptation techniques with tailored windowing functions can dynamically adjust parameters to track the evolving characteristics of genetic sequences, resulting in significant performance gains in gene prediction accuracy for cancer genomes [3].

Additional innovative approaches include Walsh Hadamard Transform (WHT) [4] and combinatorial methods that integrate statistical and DSP models for analyzing various cancer sequences [4]. These methods have demonstrated particular utility in identifying genomic samples of viruses associated with cancer, such as HIV [4].

Experimental Protocols for GSP in Cancer Research

Protocol 1: DNA Sequence Clustering Using GSP and K-means

Purpose: To perform cluster analysis of DNA sequences from cancer patients based on GSP methods and the K-means algorithm [2].

Materials and Reagents:

- DNA sequences from cancer patients (e.g., BRCA1, KIRC, COAD, LUAD, PRAD)

- Computational resources for signal processing

- Software platforms for numerical analysis (Python, MATLAB)

Procedure:

- Sequence Acquisition: Obtain DNA sequences from cancer patients. The dataset should comprise sequences associated with distinct cancer types, with appropriate sample sizes for training, validation, and testing (e.g., 194 patients for training, 98 for validation, 98 for testing) [5].

Numerical Mapping: Convert DNA sequences to numerical signals using the Voss representation [2]:

- For each sequence, create four binary indicator sequences representing nucleotides A, T, G, C

- Generate the fourth-dimensional DNA signal Xˆα

Spectral Analysis:

- Apply Discrete Fourier Transform to each DNA signal

- Compute the Power Spectral Density (PSD) Sˆα for each sequence

- The PSD serves as a descriptor of nucleotide patterns within the DNA sequence

Cluster Analysis:

- Apply K-means algorithm to the PSD data Ω = [ω1, ω2, …, ωm]

- Use Euclidean distance as the similarity metric

- Repeat computation multiple times (e.g., 50 times) and keep the best convergence score to account for random initial label assignments [2]

Result Visualization:

- Compute the main centroid point M as the geometrical center of the K centroids

- For each cluster j, compute the Euclidean distance dj of its centroid Cj relative to M

- Sort centroids according to distance to the main centroid for visualization [2]

Protocol 2: Cancer Prediction Using GSP with Machine Learning Classifiers

Purpose: To develop a high-accuracy DNA-based cancer risk predictor by blending GSP with machine learning approaches [5].

Materials and Reagents:

- DNA sequences associated with multiple cancer types (e.g., 390 patients across 5 cancer types)

- Computational resources for machine learning

- Data preprocessing tools for outlier removal and standardization

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Perform outlier removal using appropriate functions (e.g., Pandas drop())

- Execute data standardization using tools like StandardScaler in Python

- Retain all available features within the dataset without reduction [5]

Model Development:

- Employ a blended ensemble of Logistic Regression with Gaussian Naive Bayes

- Optimize hyperparameters via grid search technique

- Implement 10-fold cross-validation, dividing the dataset into ten distinct subsets

- Use nine subsets for training and one for validation, rotating this process ten times [5]

Model Validation:

- Aggregate predictions from K-trained models

- Use an independent hold-out test set comprising 20% of the full cohort for final assessment

- Ensure no data leakage between training and validation splits [5]

Performance Evaluation:

- Assess accuracy across different cancer types (e.g., BRCA1, KIRC, COAD, LUAD, PRAD)

- Compute micro- and macro-average ROC AUC values

- Compare results with existing state-of-the-art methods [5]

Table 2: Performance Metrics of GSP-Based Cancer Classification

| Cancer Type | Full Name | Reported Accuracy | Key Genetic Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA1 | Breast Cancer gene 1 | 100% | Mutations in RING and BRCT domains |

| KIRC | Kidney Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma | 100% | Immunological responses, metabolic pathways |

| COAD | Colorectal Adenocarcinoma | 100% | APC gene mutations |

| LUAD | Lung Adenocarcinoma | 98% | EGFR pathway alterations |

| PRAD | Prostate Adenocarcinoma | 98% | Androgen receptor (AR) pathway mutations |

Visualization and Data Analysis Workflows

GSP-Based DNA Sequence Clustering Workflow

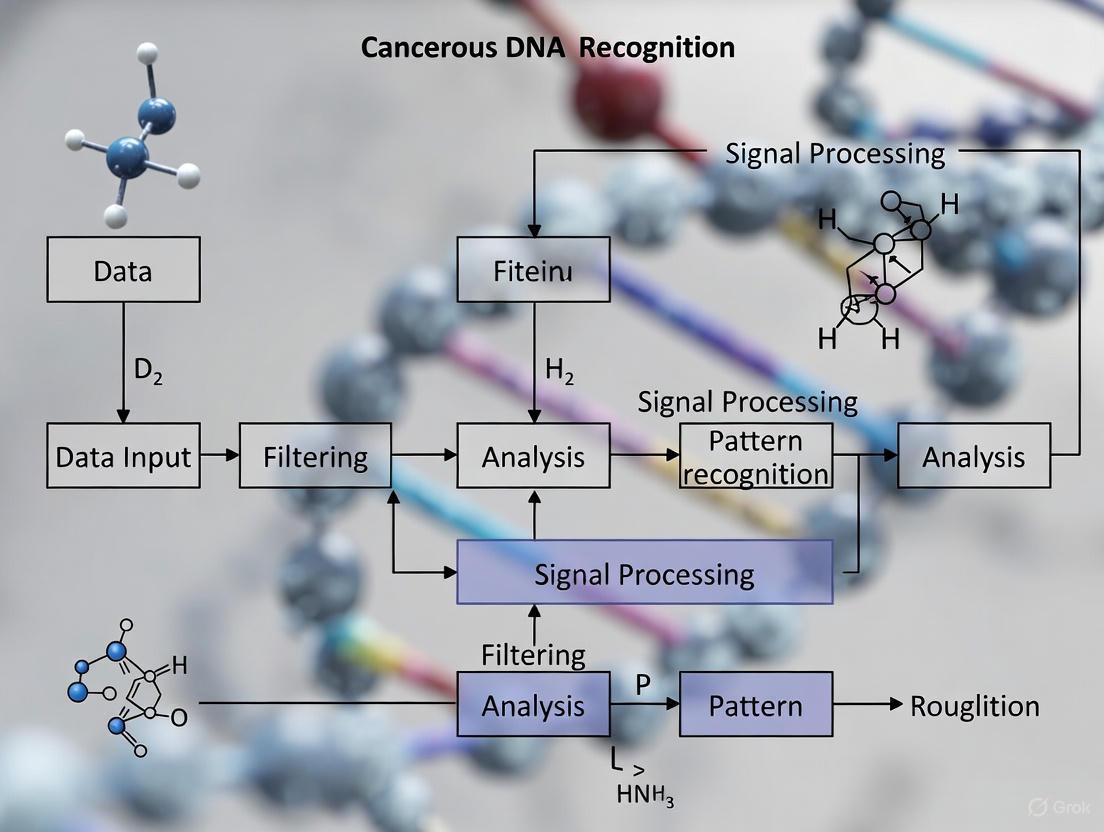

GSP-Based DNA Sequence Clustering Workflow: This diagram illustrates the complete pipeline from raw DNA sequences to cluster visualization using genomic signal processing techniques.

GSP for Cancer Classification Workflow

GSP for Cancer Classification Workflow: This diagram shows the integrated approach of GSP with machine learning for multi-cancer classification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for GSP in Cancer Research

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications/Alternatives |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Sequences from Cancer Patients | Primary data for GSP analysis | 390+ patients across multiple cancer types; accessible via repositories like Kaggle |

| Voss Representation Algorithm | Converts DNA sequences to numerical signals | Four binary indicator sequences for A, T, G, C |

| Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT) | Identifies periodic patterns in genomic data | Implementation in Python (SciPy) or MATLAB |

| Power Spectral Density (PSD) Calculator | Quantifies distribution of power in frequency domain | Essential for identifying period-3 property in exons |

| K-means Clustering Algorithm | Groups sequences with similar spectral features | Euclidean distance metric; multiple iterations for stability |

| Ensemble Classifiers (Logistic Regression + Gaussian NB) | Cancer type prediction from genomic features | Hyperparameter optimization via grid search |

| Cross-Validation Framework | Model validation and performance assessment | 10-fold stratified cross-validation |

| SHAP Analysis Tool | Model interpretability and feature importance | Identifies dominant genes in classification decisions |

Applications in Cancer Research and Future Directions

GSP techniques have demonstrated significant utility across multiple domains of cancer research. In cluster analysis, GSP methods combined with K-means algorithms enable researchers to find and visualize interesting features of sets of DNA data without prior information about the hidden structure [2]. This approach facilitates the exploration of cancer subtypes based on genomic signatures rather than solely on histological characteristics.

For cancer prediction, the integration of GSP with machine learning classifiers has yielded remarkable accuracy. Recent research reports accuracies of 100% for BRCA1, KIRC, and COAD, while achieving 98% for LUAD and PRAD—representing improvements of 1–2% over recent deep-learning and multi-omic benchmarks [5]. These approaches provide lightweight, interpretable, and highly effective tools for early cancer prediction.

The convergence of GSP with artificial intelligence represents a promising future direction. Deep learning models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs), are increasingly being applied to genomic data [6]. These technologies can automatically extract valuable features from large-scale datasets, enhancing early detection accuracy and efficiency in cancer diagnostics [6]. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they hold the potential to further revolutionize precision oncology by enabling more accurate molecular classification of tumors and personalized treatment strategies.

Performance Metrics in Cancer Research

The following table summarizes quantitative performance data from recent studies applying DWT and Fourier analysis to cancer detection and diagnosis.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Transform-Based Methods in Cancer Research

| Cancer Type | Analytical Method | Data Source | Key Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer | Frequency-guided Wavelet Network (FreqWNet) | Optical time-stretch imaging of cell death | 98.42% F1-score for cell death state identification | [7] |

| Lung, Breast & Ovarian Cancer | DWT with Genomic Signal Processing | NCBI gene sequences | 100% classification accuracy with Support Vector Machine | [8] |

| Breast Cancer | Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy | Serum, biopsy, plasma, saliva | ~98% Sensitivity, ~100% Specificity (Systematic Review) | [9] |

| Pancreatic Cancer | DWT + Probability Neural Network (PNN) | ATR-FT-IR spectra of rat tissue | 98% correct for early carcinoma; 100% for advanced carcinoma | [10] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Genomic Sequence Analysis for Cancer Mutation Detection

This protocol outlines the procedure for differentiating cancerous from non-cancerous genomic sequences using DWT, achieving high classification accuracy [8].

1. Data Acquisition

- Source: Obtain cancerous and non-cancerous gene sequences from curated databases such as NCBI.

- Targets: Sequences for specific cancers (e.g., lung, breast, ovarian).

2. Numerical Mapping

- Convert genomic sequences (A, C, G, T) into numerical indicator sequences that can be processed by signal analysis techniques.

3. Wavelet Decomposition

- Apply a 4-level Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) using the Haar wavelet to the numerical sequences.

- This decomposition produces a set of approximation and detail coefficients across multiple resolution scales.

4. Feature Extraction

- From the wavelet domain coefficients, calculate a set of statistical features for each sequence. These typically include:

- Mean

- Median

- Standard Deviation

- Interquartile Range

- Skewness

- Kurtosis

- From the wavelet domain coefficients, calculate a set of statistical features for each sequence. These typically include:

5. Classification

- Use the extracted statistical features as input for a machine learning classifier.

- Algorithm: Support Vector Machine (SVM).

- The model is trained to classify sequences as "cancerous" or "non-cancerous" based on these features.

Protocol: Cell Death Pathway Prediction via Multi-Modal Imaging

This protocol describes a framework for label-free prediction of cell death pathways in lung cancer chemotherapy using a advanced wavelet network [7].

1. Sample Preparation and Imaging

- Treat lung cancer cells with chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., cisplatin).

- Acquire single-cell intensity and phase images in a label-free manner using a multi-modal Optical Time-Stretch Imaging Flow Cytometry (OTS-IFC) system.

2. Feature Extraction with Dual-Stream Network

- Process the intensity and phase images through a dual-stream Frequency-guided Wavelet Network (FreqWNet).

- Within the network, a Wavelet Frequency Decoupling (WFD) module performs:

- Decomposition: Uses DWT to disentangle low-frequency (global structural) information from high-frequency (fine textural) details.

- Processing: The low-frequency branch captures global representations. The high-frequency branch undergoes residual convolution to enhance fine-grained features.

- Reconstruction: An inverse wavelet transform is applied to reconstruct the enhanced features.

3. Cross-Modal Feature Fusion

- Implement a cross-modal collaboration module that uses a mutual attention mechanism to adaptively align and fuse the complementary features extracted from the intensity and phase image streams.

4. State Identification and Prediction

- The fused, robust feature representations are used by the model to identify cell death states and predict the specific death pathway with high accuracy.

Workflow Visualization

Genomic Signal Processing for Cancer Detection

FreqWNet for Cell Death Prediction

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Materials and Computational Tools

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application in Research | Example from Context |

|---|---|---|

| Nicole NEXUS 670 FTIR Spectrometer | Acquires vibrational spectra from biological samples to detect biochemical changes associated with cancer. | Used with a diamond ATR accessory to collect FT-IR spectra from pancreatic tissues [10]. |

| Multi-modal OTS-IFC System | High-throughput, label-free acquisition of single-cell intensity and phase images for real-time analysis. | Core component for imaging lung cancer cells in various death states [7]. |

| NCBI Gene Sequence Database | Repository for obtaining standardized cancerous and non-cancerous genomic sequences for analysis. | Source of lung, breast, and ovarian cancer sequences for genomic signal processing [8]. |

| Haar Wavelet / Daubechies Wavelet | Mother wavelets used in DWT for decomposing signals and images into frequency components. | Haar wavelet used for genomic sequence decomposition [8] and Daubechies for FT-IR feature extraction [10]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | A machine learning classifier effective for high-dimensional data, used for final decision making. | Achieved 100% accuracy in classifying genomic sequences [8]. |

| Probability Neural Network (PNN) | A feed-forward neural network based on statistical theory, suitable for pattern classification tasks. | Used to classify pancreatic tissues based on FT-IR features with high accuracy [10]. |

Converting DNA Sequences into Numerical Indicator Signals

The conversion of DNA sequences into numerical indicator signals, known as numerical mapping or numerical encoding, constitutes a fundamental preprocessing step in Genomic Signal Processing (GSP). This transformation enables the application of digital signal processing techniques to DNA sequences, facilitating the identification of patterns indicative of functional genomic elements. Within cancer research, these methods provide the computational foundation for predictive, preventive, and personalized medicine (PPPM) by revealing molecular signatures critical for early detection, accurate diagnosis, and targeted treatment strategies [11]. The core principle involves assigning numerical values to nucleotide bases (Adenine, Thymine, Cytosine, and Guanine) based on specific biological or mathematical properties, thereby converting symbolic genomic data into a quantitative format amenable to computational analysis [12].

The detection of protein-coding regions (exons) represents a primary application of these techniques in cancer genomics. In eukaryotes, protein-coding regions exhibit a period-3 property due to the codon structure, where every third nucleotide shows a statistical bias. This periodicity manifests as a dominant peak at frequency 1/3 in the Fourier spectrum, allowing exons to be distinguished from non-coding regions (introns) [12]. Advanced numerical mapping methods, combined with digital filters, enhance this signal, suppressing intron noise and accurately pinpointing coding regions—a capability essential for understanding the genomic alterations driving carcinogenesis [12] [11].

Numerical Encoding Methods: Principles and Performance

Numerical mapping methods are broadly classified into binary and non-binary schemes, each with distinct representational strategies and performance characteristics in genomic analysis [12].

Table 1: Classification and Description of Numerical Encoding Methods

| Method Category | Representative Methods | Core Principle | Nucleotide Assignment Scheme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binary Methods | Voss/OBNE [12], Four-bit Binary (FBNE) [12], Walsh Code-Based (WCBNE) [12] | Represents DNA sequences using binary vectors indicating nucleotide presence/absence or orthogonal binary codes. | FBNE: A='0100', G='0010', T='0001', C='1000' [12] |

| Non-Binary Methods | Integer-Based (IBNE) [12], Electron-Ion Interaction Potential (EIIP) [12], Hadamard Based (HBNE) [12] | Assigns integer, real, or complex numbers based on physico-chemical properties or structured matrices. | IBNE: A=1, T=2, G=3, C=4 [12] |

The Hadamard Based Numerical Encoding (HBNE) method represents a significant advancement in this field. This approach utilizes a fourth-order Hadamard matrix to generate orthogonal numerical codes for DNA nucleotides. When integrated with an Elliptic filter and Gaussian windowing technique, HBNE effectively isolates period-3 components while suppressing high-frequency noise from non-coding regions [12].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Numerical Encoding Methods for Exon Prediction

| Encoding Method | Reported Accuracy | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hadamard (HBNE) [12] | 95% | High accuracy (95%) and specificity; effective noise suppression. | Requires specialized signal processing implementation. |

| Four-bit Binary (FBNE) [12] | Not Specified | Maintains orthogonality via constant Hamming distance. | May not fully capture nucleotide interaction variability. |

| Walsh Code-Based (WCBNE) [12] | Not Specified | Structured binary encoding. | Reduced specificity in identifying nucleotide sequences. |

| Integer (IBNE) [12] | Not Specified | Simple and intuitive assignment. | May not leverage biological properties. |

| Voss (OBNE) [12] | Not Specified | Established position-based encoding. | High computational cost from high-dimensional representation. |

Recent research evaluates the representational power of pre-trained genomic Language Models (gLMs). These models, such as Nucleotide Transformer and DNABERT2, use self-supervised learning on whole genomes to generate contextual embeddings for DNA sequences [13]. However, current benchmarks indicate that for many regulatory genomics tasks, highly tuned supervised models using simple one-hot encoded sequences can achieve performance competitive with or superior to these pre-trained gLMs, highlighting an ongoing area of development [13].

Experimental Protocol: Hadamard Encoding for Exon Identification

This protocol details the application of the Hadamard Based Numerical Encoding (HBNE) method for identifying protein-coding regions in genomic sequences, using the Caenorhabditis elegans Cosmid F56F11 gene sequence as a benchmark [12].

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Materials and Software Tools

| Item Name | Function/Description | Specification/Version |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic DNA Sequence | The raw biological data for analysis. | Caenorhabditis elegans Cosmid F56F11 (NCBI Accession: FO081497) [12] |

| Hadamard Matrix (4th Order) | Generates orthogonal numerical codes for nucleotides. | A specific 4x4 orthogonal matrix used for mapping [12]. |

| Elliptic Filter | Extracts period-3 spectral components from the numerical signal. | Digital filter design for selective frequency bandpass [12]. |

| Gaussian Window | Smooths the output signal to refine coding region identification. | Applied to reduce spectral leakage and noise [12]. |

| Computational Environment | Platform for implementing the signal processing pipeline. | MATLAB or Python (with NumPy, SciPy libraries) [12] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sequence Acquisition and Preprocessing: Obtain the FASTA format DNA sequence from the NCBI database (e.g., F56F11). Remove any non-nucleotide characters and ensure the sequence is a single, continuous string of 'A', 'T', 'G', and 'C' [12].

- Numerical Mapping via HBNE: Convert the symbolic DNA sequence into a numerical sequence using the Hadamard encoding scheme. Assign to each nucleotide a specific numerical value derived from the fourth-order Hadamard matrix to create a discrete-time numerical signal [12].

- Spectral Analysis with Digital Filtering:

- Apply a Digital Elliptic Filter to the numerical sequence. This filter is designed to have a sharp frequency response, allowing it to isolate the period-3 component (around frequency 1/3) while attenuating other frequencies associated with non-coding regions [12].

- Process the filtered signal with a Gaussian Window to smooth the output, which helps in obtaining a clear and localized identification of potential exons by reducing spectral leakage [12].

- Visualization and Peak Detection: Plot the final processed signal magnitude against the nucleotide position. Protein-coding regions (exons) will appear as prominent peaks in this spectrum. Compare the predicted exon locations with known annotation files for the gene to validate the results [12].

- Performance Calculation: Calculate standard performance metrics by comparing predictions against known annotations.

- Sensitivity: Proportion of true exonic bases correctly identified.

- Specificity: Proportion of true non-exonic bases correctly identified.

- Accuracy: Overall proportion of correctly classified bases.

- Area Under the Curve (AUC): Measure of the overall discriminative power, derived from the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve [12].

Application in Cancer DNA Pattern Recognition

The translation of DNA sequences into numerical signals is pivotal for PPPM in oncology. Cancer is a complex, whole-body disease involving multi-factors, multi-processes, and multi-consequences [11]. A single biomarker is often insufficient for accurate prediction, diagnosis, or prognosis. Pattern recognition using multi-parameter molecular patterns derived from numerical representations of genomic data offers a more robust framework [11].

Molecular alterations at the genome level (e.g., mutations, Copy Number Alterations - CNA) initiate tumorigenesis. Identifying the pattern of these alterations, rather than single mutations, is critical. As noted, a typical cancer model requires mutations in two to eight "driver genes" [11]. Numerical encoding facilitates the large-scale analysis needed to detect these mutational patterns, gene expression signatures, and regulatory element variations from high-throughput sequencing data [11]. For instance, combining SNP patterns with other omics data (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) can form an integrative diagnostic pattern that significantly improves the positive detection rate compared to a single biomarker assay [11].

Advanced deep learning techniques build upon these numerical foundations. Word embedding-based methods like Word2Vec and GloVe, and modern large language models (LLMs) based on Transformer architectures, can capture complex contextual relationships and long-range dependencies in biological sequences [14]. These models are being applied to tasks such as protein function annotation, RNA structure prediction, and the interpretation of regulatory genomics data, pushing the frontiers of cancer genomics research [14] [13].

The integration of signal processing principles with genomic analysis has given rise to the field of Genomic Signal Processing (GSP), fundamentally advancing cancer research. GSP applies mathematical transform techniques, such as Discrete Wavelet Transforms (DWT) and Fourier analysis, to numerical representations of DNA sequences, allowing for the identification of patterns that are imperceptible through conventional biological methods [8] [4]. This approach enables researchers to model the genome as a complex information transmission system, where key signal features—amplitude, frequency, and entropy—can be quantified to reveal the dysfunctional signaling states that characterize cancer cells [15] [16].

The central thesis of this application note is that cancer fundamentally alters cellular information processing, and these changes can be systematically quantified by analyzing genomic and signaling pathway data through a signal processing lens. For instance, oncogenic transformations can severely corrupt a cell's capacity to perceive its environment, reducing the information transmission rate through critical signaling pathways to a fraction of that in healthy cells [15]. Similarly, specific entropy patterns and frequency-domain features derived from cancerous DNA sequences serve as reliable biomarkers for automated cancer classification [8]. The protocols herein provide a framework for detecting these diagnostic signal features, offering researchers robust tools for cancer pattern recognition.

Theoretical Foundation: Signal Processing in Cancer Genomics

Information Theory and Entropy in Cancer Signaling

At the core of this approach is Shannon information theory, which provides quantitative metrics to assess the rate of information transfer through biological communication channels, such as signaling pathways [15]. Information entropy serves as a sensitive metric for dysfunction. A landmark study demonstrated this by quantifying the Shannon information capacity of Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (RTK) signaling in both non-transformed cells (BEAS-2B) and EML4-ALK-driven lung cancer cells (STE-1) [15]. The study revealed a stark contrast: while healthy cells transmitted information at a rate of approximately 7 bits/hour, the information capacity in cancerous cells was drastically reduced to less than 0.5 bits/hour [15]. This information bottleneck was not permanent; therapeutic intervention with an ALK inhibitor (e.g., crizotinib) partially restored the information rate to 3 bits/hour, demonstrating that information entropy is a reversible metric of oncogenic dysfunction and drug efficacy [15].

Frequency and Amplitude Modulation in Cellular Networks

Biological systems natively employ frequency modulation (FM) and amplitude modulation (AM) for information encoding [16]. Research in bacterial second messenger systems has shown that frequency-encoded signals can be decoded into distinct gene expression patterns, a process governed by filtering modules that perform frequency-to-amplitude conversion [16]. The physical principles of this conversion reveal that frequency modulation can significantly expand the accessible state space of a biological system. In a three-gene regulatory system, the joint application of frequency and duty cycle control can yield approximately two additional bits of information entropy compared to amplitude-only control, effectively quadrupling the number of distinguishable expression states [16]. This underscores the critical importance of analyzing temporal dynamics, not just signal intensity, to fully understand the corrupted information processing in cancer.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: DWT-Based Classification of Cancerous Genomic Sequences

This protocol details a method for differentiating cancerous from non-cancerous gene sequences using Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) and machine learning, achieving high classification accuracy [8].

- 1. Objective: To automatically identify cancerous genomic sequences (e.g., for lung, breast, or ovarian cancer) by extracting statistical signal features from wavelet-domain representations.

- 2. Materials:

- Genomic Sequences: Cancerous and non-cancerous DNA sequences for specific cancer types, sourced from databases like NCBI [8].

- Software Tools: Computational environment for signal processing and machine learning (e.g., MATLAB, Python with SciPy/scikit-learn).

- 3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Numerical Mapping. Convert the genomic DNA sequences (composed of A, T, C, G) into numerical indicator sequences. A common complex representation is used, which is suitable for subsequent GSP techniques [8].

- Step 2: Wavelet Decomposition. Apply a four-level Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) using the Haar wavelet to the numerical sequence. This decomposes the signal into approximation and detail coefficients, capturing patterns at multiple resolutions [8].

- Step 3: Feature Extraction. From the wavelet domain coefficients, calculate the following six statistical features for each sequence: Mean, Median, Standard Deviation, Interquartile Range, Skewness, and Kurtosis [8].

- Step 4: Model Training and Classification. Use the extracted statistical features as input to a machine learning classifier. The Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier has been shown to achieve high accuracy in distinguishing cancerous from non-cancerous sequences based on these features [8].

The workflow for this protocol is standardized and can be visualized as follows:

Protocol 2: Quantifying Information Capacity in Live-Cell Signaling Pathways

This protocol employs optogenetics, live-cell imaging, and information theory to quantify how cancer and drugs alter the information capacity of signaling pathways [15].

- 1. Objective: To compare the information transmission rate (bitrate) of the RTK/ERK signaling pathway between non-transformed and cancerous cell lines, and to evaluate the effects of targeted inhibitors.

- 2. Materials:

- Cell Lines: Non-transformed (e.g., BEAS-2B) and cancerous (e.g., patient-derived STE-1) cell lines [15].

- Optogenetic System: Cells engineered to express optoFGFR (a light-inducible FGF receptor) and an ERK activity reporter (ERK-KTR) [15].

- Live-Cell Imaging Setup: Microscope with environmental control and precise light stimulation capability.

- Reagents: Targeted inhibitors (e.g., ALKi Crizotinib, MEKi Trametinib, CALCi Cyclosporine A) [15].

- 3. Procedure:

- Step 1: Pseudorandom Stimulation. Stimulate the optoFGFR pathway in single cells with a pseudorandom series of light pulses. The intervals between pulses should follow a fixed distribution (e.g., from 5 to 35 minutes) designed to sample a broad range of input frequencies [15].

- Step 2: Response Monitoring. Record the dynamics of ERK activity by imaging the nucleocytoplasmic translocation of the ERK-KTR reporter every minute throughout the stimulation period [15].

- Step 3: Signal Reconstruction. Train a multilayer perceptron (MLP), a type of artificial neural network, to reconstruct the input light pulse sequence from the observed ERK-KTR trajectory. The model uses a short fragment of the trajectory and the time since the last pulse as key inputs [15].

- Step 4: Information Calculation. Compute the transmitted information rate, I(X;Y), as the input information rate (entropy of the stimulus, H(X)) minus the reconstruction entropy rate (uncertainty in the stimulus given the response, H(X|Y)). The channel capacity is the maximum achievable information rate under optimal encoding [15].

The experimental setup and information flow for this protocol are complex, as shown in the following diagram:

Data Presentation and Analysis

Quantitative Analysis of Information Capacity

The following table summarizes quantitative findings from the application of information theory to live-cell signaling data, highlighting cancer-induced deficits and drug-induced recoveries in information transmission [15].

Table 1: Information Transmission Rates in RTK/ERK Signaling Pathway

| Cell Line / Condition | Information Transmission Rate (bits/hour) | Key Experimental Condition |

|---|---|---|

| BEAS-2B (Non-transformed) | ~7.0 | Baseline optoFGFR stimulation [15] |

| STE-1 (EML4-ALK Cancer) | < 0.5 | Baseline optoFGFR stimulation [15] |

| STE-1 + ALK Inhibitor | ~3.0 | Treatment with crizotinib [15] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below catalogs essential reagents and their functions for conducting experiments in cancer genomic signal processing and signaling pathway analysis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| optoFGFR | An optogenetic FGF receptor fusion protein (Cry2-FGFR1). Allows precise, pulsatile activation of the RTK pathway with light, replacing biochemical ligands for superior temporal control [15]. |

| ERK-KTR Reporter | A live-cell biosensor (Kinase Translocation Reporter) that undergoes nucleocytoplasmic shuttling upon ERK phosphorylation. Enables minute-resolution tracking of ERK activity dynamics via fluorescence imaging [15]. |

| ALK Inhibitor (Crizotinib) | A targeted therapeutic drug used in protocol 2 to investigate the restoration of information capacity in EML4-ALK driven cancer cells [15]. |

| Haar Wavelet | A specific wavelet function used in the DWT for genomic signal analysis. It is effective for detecting sharp transitions and features in numerical representations of DNA sequences [8]. |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | A machine learning classifier used to differentiate cancerous from non-cancerous sequences based on statistical features extracted from the wavelet domain, noted for achieving high classification accuracy [8]. |

The protocols and data presented herein demonstrate that the signal processing framework provides a powerful, quantitative lens through which to view cancer. The corrupting influence of oncogenes extends beyond simple constitutive activation to a fundamental degradation of information fidelity and throughput, as quantified by entropy and bitrate measures [15]. Furthermore, the successful classification of cancerous genomes using DWT-derived features confirms that these information deficits are encoded in the static DNA sequence itself, manifesting as discernible patterns in the frequency domain [8].

The implications for drug development are substantial. Information-theoretic metrics like channel capacity offer a novel, sensitive, and functional readout for evaluating targeted therapies, moving beyond traditional amplitude-based measures of pathway inhibition [15]. The restoration of information flow, not just the suppression of a signal, could become a new benchmark for therapeutic efficacy.

Future research directions will involve the deeper integration of cloud-scale genomic signal processing to handle the computational demands of large-scale cancer genomic datasets [17]. Furthermore, the application of explainable AI (XAI) and advanced neural network models like large language models (LLMs) to DNA methylation and other epigenomic data presents a promising frontier for uncovering deeper, more causal patterns in cancer epigenetics [18]. By continuing to leverage the tools of signal processing and information theory, researchers can decode the complex language of cancer genomes, accelerating the development of sophisticated diagnostics and therapeutics.

Advanced Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Cancer Diagnostics

Machine and Deep Learning Integration with GSP for Classification

Application Notes: The Role of GSP and ML in Cancer Genomics

The integration of Graph Signal Processing (GSP) with machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) creates a powerful paradigm for analyzing complex biological data, particularly for cancer classification based on genomic signatures. This approach excels at capturing spatial relationships and structural dependencies within genetic information that traditional methods often miss.

Core Analytical Strengths and Documented Performance

GSP techniques, particularly the Graph Fourier Transform (GFT), provide a mathematical framework for analyzing signals defined on graph structures. This is exceptionally valuable for representing irregular, non-Euclidean relationships inherent in biological networks, such as gene interactions or spatial tumor morphology. When integrated with ML, these techniques enable a more comprehensive representation of tumor characteristics by capturing both spatial proximity and spectral characteristics [19].

Recent research demonstrates the superior performance of integrated approaches:

- Brain Tumor Classification: A GFT-based feature extraction method combined with ML classifiers achieved 94.91% accuracy on the Kaggle-253 dataset and 98.50% on the BR35H dataset, significantly outperforming models without GSP-based features [19].

- Multi-Cancer Classification from DNA: A blended ensemble model combining Logistic Regression and Gaussian Naive Bayes achieved accuracies of up to 100% for certain cancer types (BRCA1, KIRC, COAD) and 98% for others (LUAD, PRAD) on a dataset of 390 patients [5].

- Advanced Multi-Representation Frameworks: The GraphVar framework, which integrates mutation-derived imaging and numeric genomic features using a ResNet-18 backbone and a Transformer encoder, reported an overall accuracy of 99.82% across 33 cancer types from 10,112 patients in the TCGA cohort [20].

The table below summarizes quantitative performance benchmarks from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of Integrated GSP-ML/DL Models in Cancer Classification

| Model/Framework | Core Methodology | Data Type | Cancer Types | Key Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFT + RF/LGBM [19] | Graph Fourier Transform with ML classifiers | Brain MRI | Brain Tumors | Accuracy: 94.91% (Kaggle-253), 98.50% (BR35H) |

| Blended Ensemble [5] | Logistic Regression + Gaussian Naive Bayes | DNA Sequences | 5 types (e.g., BRCA, LUAD) | Accuracy: 98-100%; ROC AUC: 0.99 |

| GraphVar [20] | ResNet-18 + Transformer on variant maps & numeric features | Somatic Mutations (TCGA) | 33 types | Accuracy: 99.82%; F1-Score: 99.82% |

| MARLIN [21] | Neural Network on DNA Methylation Patterns | DNA Methylation (Nanopore) | Acute Leukemia (38 subtypes) | Rapid classification in <2 hours; high accuracy |

Key Applications in Cancer Research

The primary application of this integration is accurate cancer type and subtype classification, which is fundamental for precision oncology. This is critical because the same cancer type can have different molecular subtypes that respond differently to treatments. For instance, the MARLIN tool uses DNA methylation patterns to classify 38 distinct subtypes of acute leukemia, resolving diagnostic "blind spots" that conventional methods can miss [21].

Another crucial application is biomarker discovery and interpretability. Models like GraphVar employ techniques such as Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) to highlight which genes or genomic regions were most influential in the classification decision, thereby identifying potential novel biomarkers or validating known ones [20]. Similarly, SHAP analysis on DNA sequencing data has shown that model decisions are often dominated by a small subset of features, indicating strong potential for dimensionality reduction and focused biological validation [5].

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed, replicable methodologies for implementing GSP and ML/DL for genomic cancer classification, based on published frameworks.

Protocol 1: GFT-Based Feature Extraction for Classification

This protocol is adapted from methodologies that have successfully classified brain tumors from MRI data [19] and can be adapted for genomic spatial data.

2.1.1 Reagents and Materials

- Dataset: Genomic data (e.g., from TCGA [22] [20]) or spatial transcriptomics data.

- Software: Python (v3.10+) with libraries: Scikit-learn, NumPy, PyTorch/TensorFlow, and GSP libraries (e.g., PyGSP).

- Computing: Standard workstation (16GB RAM, multi-core CPU); GPU optional for this protocol.

2.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

Graph Construction:

- Represent your data as a graph ( G = (V, E, W) ), where ( V ) is a set of nodes (e.g., individual genes, genomic loci, or image pixels), ( E ) is a set of edges connecting related nodes, and ( W ) is a weight matrix defining the strength of these connections.

- Edge-Weighting: Define the relationships between nodes. Two common techniques are:

- Binary Weighting: ( W{ij} = 1 ) if nodes ( i ) and ( j ) are connected (e.g., adjacent genomic regions, physically interacting proteins), else ( 0 ) [19].

- Gaussian Weighting: ( W{ij} = \exp(-\frac{{||xi - xj||}^2}{2\sigma^2}) ), where ( xi ) and ( xj ) are feature vectors of nodes ( i ) and ( j ), and ( \sigma ) is a scaling parameter. This captures intensity similarity [19].

Graph Laplacian Calculation:

- Compute the Graph Laplacian matrix ( L = D - W ), where ( D ) is the diagonal degree matrix (( D{ii} = \sumj W_{ij} )).

Spectral Decomposition:

- Perform eigenvalue decomposition of the Laplacian: ( L = U \Lambda U^T ).

- The eigenvectors ( U ) form the Graph Fourier Basis, analogous to the classical Fourier basis, but tailored to the graph structure.

Graph Fourier Transform (GFT):

- For a graph signal ( f ) (a scalar value defined on each node, like gene expression), compute its GFT as ( \hat{f} = U^T f ).

- The resulting ( \hat{f} ) represents the signal's expansion in the spectral domain of the graph, capturing its frequency components.

Feature Resampling (Optional):

- If the dataset has class imbalance (e.g., many more normal samples than tumor), apply the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) to the extracted GFT features to create a balanced training set [19].

Model Training and Classification:

The following workflow diagram illustrates the GFT-based feature extraction protocol:

Protocol 2: Multi-Representation Deep Learning for Pan-Cancer Classification

This protocol is inspired by the GraphVar framework [20] and is designed for high-throughput somatic mutation data from projects like TCGA.

2.2.1 Reagents and Materials

- Data: Somatic variant data in Mutation Annotation Format (MAF) from TCGA or similar consortium.

- Software: Python (v3.10+) with PyTorch (v2.2.1+), Scikit-learn, OpenCV, and Transformers library.

- Computing: High-performance computing node with multiple GPUs (e.g., NVIDIA A100/V100) for efficient training of large models.

2.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Curation and Partitioning:

- Download and curate MAF files, removing duplicate patient entries.

- Partition the data at the patient level into training (70%), validation (10%), and a held-out test set (20%) using stratified sampling to preserve class proportions [20].

Dual-Input Feature Generation:

- Variant Map Construction (Image Modality):

- Organize mutated genes based on their chromosomal positions (chromosomes 1-22, X, Y).

- Encode different variant types into pixel intensities in a 2D image: SNPs (Blue), Insertions (Green), Deletions (Red) [20].

- This creates a spatial, image-like representation of the mutational landscape of a sample.

- Numeric Feature Matrix Construction:

- Calculate a 36-dimensional feature vector for each sample, including population allele frequencies and probabilities across 6 somatic mutation spectra (e.g., C>A, C>G, C>T, T>A, T>C, T>G) [20].

- Variant Map Construction (Image Modality):

Dual-Stream Model Architecture:

- Image Stream: Use a pre-trained ResNet-18 convolutional neural network (CNN) as a backbone to extract high-level spatial features from the variant maps [20].

- Numeric Stream: Use a Transformer encoder to model complex, long-range dependencies within the 36-dimensional numeric feature matrix. The attention mechanism is key here [20].

- Feature Fusion: Concatenate the feature embeddings from the ResNet-18 and Transformer branches into a comprehensive feature vector.

Model Training and Interpretation:

- Feed the fused feature vector into a fully connected classification head with a softmax output layer for final cancer type prediction.

- Use Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) on the variant maps to visualize and biologically validate which genomic regions the model prioritized for its decision [20].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the multi-representation deep learning protocol:

Successful implementation of the described protocols requires a suite of data, computational tools, and algorithms. The table below catalogs key resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for GSP-ML Integration

| Category | Item | Function/Description | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Data | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Provides comprehensive, multi-omics data (genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic) from over 11,000 tumor samples across 33+ cancer types for model training and validation. | [23] [22] [20] |

| NIST Cancer Genome in a Bottle | Provides a benchmark, ethically-sourced, whole-genome sequenced cancer cell line (pancreatic) for quality control and technology development. | [24] | |

| Computational Algorithms | Graph Fourier Transform (GFT) | Core GSP operation that transforms a graph signal into its spectral components, enabling the analysis of spatial patterns and relationships. | [19] |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Deep learning architecture ideal for processing image-like data, such as variant maps or MRIs, to extract hierarchical spatial features. | [23] [20] | |

| Transformer Encoder | Advanced neural network architecture that uses self-attention mechanisms to weigh the importance of different elements in a sequence (e.g., numeric feature vectors). | [20] | |

| Software & Libraries | PyTorch / TensorFlow | Open-source libraries for developing and training deep learning models. Provide flexibility for custom architectures like GraphVar. | [20] |

| Scikit-learn | Provides a wide array of traditional ML algorithms (e.g., Random Forest) and utilities for data preprocessing and model evaluation. | [5] [19] | |

| Analytical Techniques | Stratified K-Fold Cross-Validation | A resampling procedure used to evaluate a model by partitioning the data into 'k' folds while preserving the percentage of samples for each class, ensuring robust performance estimation. | [5] |

| Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) | A technique for producing visual explanations for decisions from a wide range of CNN-based models, making them more interpretable. | [22] [20] | |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A game theory-based method to explain the output of any machine learning model, identifying the contribution of each feature to the prediction. | [5] |

The detection of DNA methylation patterns represents a critical frontier in the advancement of cancer diagnostics and personalized medicine. DNA methylation, defined as the addition of a methyl group to the cytosine ring within CpG dinucleotides, serves as a fundamental epigenetic modification that regulates gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence [25]. This process is mediated by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs) including DNMT1, DNMT3a, and DNMT3b, which act as "writers" of methylation marks, while ten-eleven translocation (TET) family enzymes function as "erasers" through active demethylation processes [25]. In cancerous tissues, both global hypomethylation and locus-specific hypermethylation contribute to carcinogenesis by silencing tumor suppressor genes and activating oncogenes, making methylation patterns highly valuable biomarkers for early cancer detection [26].

The analysis of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) circulating in blood plasma presents particular promise for non-invasive cancer detection, though it introduces significant signal processing challenges due to the exceptionally low abundance of tumor-derived cfDNA, especially during early cancer stages [27]. Signal processing methodologies must therefore evolve to extract meaningful epigenetic signals from this complex biological background noise, driving innovation in both biochemical assays and computational analysis techniques.

Methylation Detection Technologies: A Comparative Analysis

The accurate profiling of DNA methylation patterns relies on multiple technological platforms, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and appropriate applications. These methods generally fall into three categories: bisulfite conversion-based sequencing, enrichment-based approaches, and microarray technologies.

Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) currently represents the gold standard for comprehensive methylation analysis, providing single-base resolution across the entire genome [26]. Reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS) offers a more targeted approach by focusing on CpG-rich regions, thereby reducing sequencing costs and computational requirements [25]. For clinical applications requiring high throughput, Illumina's Infinium HumanMethylation BeadChip arrays (450K and 850K) provide a cost-effective solution for profiling pre-selected CpG sites [25]. More recently, enhanced linear splint adapter sequencing (ELSA-seq) has emerged as a promising method for detecting circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) methylation with high sensitivity and specificity, making it particularly suitable for liquid biopsy applications [25].

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Methylation Detection Techniques

| Technique | Resolution | Coverage | Cost | Primary Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGBS | Single-base | Genome-wide | High | Comprehensive methylome mapping, discovery | High cost, computationally intensive [25] |

| RRBS | Single-base | CpG-rich regions | Medium | Regional methylation analysis, biomarker validation | Limited to regions with specific CpG density [25] |

| BeadChip Arrays | Single CpG site | Pre-defined sites (~850,000) | Low | High-throughput screening, clinical applications | Limited to pre-designed CpG sites [25] [26] |

| ELSA-seq | Single-base | Targeted regions | Medium | Liquid biopsy, MRD monitoring, cancer recurrence | Requires prior knowledge of target regions [25] |

| MeDIP-seq | ~100-500 bp | Genome-wide | Medium | Methylated region enrichment | Lower resolution, antibody-dependent [25] |

Each methodology generates distinct data types and signal-to-noise characteristics that directly influence subsequent processing requirements. WGBS and RRBS produce nucleotide-resolution methylation ratios but require extensive sequencing depth and sophisticated alignment algorithms to account for bisulfite-induced sequence conversion. BeadChip arrays provide discrete methylation β-values but are constrained by their predetermined genomic coverage. The selection of an appropriate detection technology must therefore balance resolution needs, cost constraints, and specific research objectives.

Targeted Methylation Sequencing for Multi-Cancer Detection

Targeted methylation sequencing has emerged as a particularly powerful approach for multi-cancer early detection from blood-based liquid biopsies. This methodology focuses on specific genomic regions known to exhibit differential methylation patterns between normal and cancerous tissues, offering enhanced sensitivity for detecting low-abundance tumor-derived cfDNA against a background of predominantly normal cfDNA [27].

The Circulating Cell-free Genome Atlas (CCGA) study, a prospective, observational, longitudinal clinical trial conducted by GRAIL, provided seminal insights into the comparative performance of methylation-based approaches. In its first phase, the CCGA compared three next-generation sequencing techniques: whole-genome sequencing, targeted mutation detection, and targeted methylation sequencing. The results demonstrated that targeted methylation analysis significantly outperformed both alternative approaches in distinguishing cancerous from non-cancerous samples [27]. Based on these findings, the study progressed with targeted methylation analysis as its primary methodology for subsequent phases.

The targeted approach employed in CCGA utilized custom capture probes covering more than 100,000 distinct genomic regions and encompassing over one million individual methylation sites [27]. This extensive coverage required specialized probe synthesis capabilities, which were facilitated through collaboration with Twist Bioscience, leveraging their high-throughput oligonucleotide synthesis technologies to produce the necessary targeted enrichment panels [27].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Targeted Methylation Sequencing

| Reagent/Component | Function | Example Specification | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Enrichment Panels | Hybridization capture of methylated genomic regions | >100,000 regions; >1 million CpG sites [27] | Custom design required for specific cancer types |

| Bisulfite Conversion Reagents | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosines to uracils | >99% conversion efficiency | Critical step that requires optimization to minimize DNA degradation [25] |

| NGS Methylation Detection System | Integrated reagents for library prep and capture | Reduced bias and off-target capture [27] | Twist Bioscience system enhances capture uniformity |

| Methylation-Specific PCR Primers | Amplification of converted DNA | Specific to methylated/unmethylated sequences after bisulfite treatment | Useful for validation but limited scalability [25] |

A critical technical consideration in methylation sequencing involves the timing of bisulfite conversion relative to library amplification and capture. For low-abundance targets like cfDNA, the pre-capture conversion approach is generally preferred, where bisulfite conversion occurs before amplification and capture. This sequence increases library complexity and reduces input DNA requirements, though it necessitates specialized probe design to control for off-target capture and maintain high sensitivity [27].

Interim results from the CCGA study's second phase demonstrated remarkable performance characteristics, with the ability to detect more than 50 cancer types across all stages at greater than 99% specificity, while also localizing the tissue of origin with over 90% accuracy [27]. These findings underscore the transformative potential of targeted methylation sequencing as a foundation for multi-cancer early detection tests.

Experimental Protocol: Targeted Methylation Sequencing from Plasma cfDNA

Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Begin with collection of peripheral blood into cell-stabilizing tubes (e.g., Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT) to prevent genomic DNA contamination from leukocyte lysis. Process samples within 24-48 hours of collection through differential centrifugation: 800-1600 × g for 10 minutes at room temperature to separate plasma from cellular components, followed by 16,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove remaining debris. Isolate cfDNA from 4-10 mL of plasma using silica membrane-based extraction kits specifically validated for low-concentration samples. Quantify extracted cfDNA using fluorometric methods sensitive to low DNA concentrations (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay). Expect yields of 5-30 ng/mL plasma, with higher amounts potentially indicating underlying pathology.

Library Preparation with Pre-Capture Bisulfite Conversion

Dilute cfDNA to 5-10 ng in 20-50 μL TE buffer. Add freshly prepared bisulfite conversion reagent (commercial kits recommended) and incubate using thermal cycling conditions optimized to maximize conversion while minimizing DNA fragmentation: denaturation at 95°C for 30-60 seconds, incubation at 60°C for 20-45 minutes, and optional repeated cycles. Desalt converted DNA using column-based purification and elute in low-volume Tris-EDTA buffer. Proceed immediately to library construction to minimize degradation.

For library preparation, add adapters with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to account for amplification biases and PCR duplicates during data analysis. Use polymerase enzymes capable of reading uracil bases resulting from bisulfite conversion. Amplify libraries with 8-12 PCR cycles to generate sufficient material for hybridization capture while maintaining library complexity.

Targeted Capture and Sequencing

Dilute amplified libraries to 100-500 ng in hybridization buffer and combine with targeted methylation panel (e.g., Twist Bioscience Methylation Panel). Incubate at 65°C for 16-24 hours with agitation. Wash with increasingly stringent buffers to remove non-specifically bound DNA. Elute captured DNA and amplify with 10-14 PCR cycles using indexing primers for sample multiplexing. Quality control includes capillary electrophoresis for size distribution (expected peak ~300 bp) and qPCR for quantification.

Pool indexed libraries in equimolar ratios and sequence on Illumina platforms (NovaSeq recommended) to achieve minimum coverage of 1000x per CpG site. Include non-methylated lambda phage DNA spike-in controls to monitor bisulfite conversion efficiency, targeting >99% conversion.

Computational Analysis of Methylation Data

Primary Data Processing and Quality Control

Begin analysis with raw sequencing files (FASTQ format). Assess quality metrics using FastQC or MultiQC, focusing on per-base sequence quality, adapter contamination, and bisulfite conversion efficiency. Align reads to a bisulfite-converted reference genome using specialized aligners such as Bismark, BSMAP, or BS-Seeker2, accounting for C-to-T conversions. Retain only properly paired reads with mapping quality scores >20. Remove PCR duplicates using UMI information to prevent amplification bias. Calculate methylation ratios at each CpG site by counting converted versus unconverted reads, requiring minimum coverage of 10-20x per site for reliable quantification.

Advanced Signal Processing and Machine Learning Approaches

Machine learning algorithms have revolutionized the interpretation of complex methylation data by identifying subtle patterns indicative of cancerous transformation. Both conventional supervised methods and deep learning architectures play crucial roles in this analytical pipeline.

Conventional supervised methods including support vector machines (SVM), random forests (RF), and gradient boosting have demonstrated strong performance for classification tasks using methylation array or sequencing data [25]. These approaches are particularly valuable for sample classification (cancer vs. normal), tissue-of-origin identification, and feature selection across tens to hundreds of thousands of CpG sites.

More recently, deep learning architectures have shown remarkable capability in capturing nonlinear interactions between CpG sites and genomic context. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) can identify spatially correlated methylation patterns across genomic regions, while multilayer perceptrons (MLPs) excel at integrating multimodal data [26]. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) and their variants (LSTM, GRU) can model sequential dependencies along chromosomal coordinates.

Most promisingly, transformer-based foundation models pretrained on extensive methylome datasets (e.g., MethylGPT, CpGPT) have demonstrated robust cross-cohort generalization and contextually aware CpG embeddings that transfer efficiently to age and disease-related outcomes [25]. These models enhance analytical efficiency in limited clinical populations and represent the cutting edge of methylation signal processing.

The integration of advanced signal processing methodologies with DNA methylation analysis has created a powerful paradigm for cancer detection and classification. Targeted methylation sequencing, particularly when combined with machine learning algorithms, demonstrates exceptional performance in multi-cancer early detection from liquid biopsy samples, with specificities exceeding 99% and accurate tissue-of-origin localization in over 90% of cases [27]. These capabilities position methylation-based diagnostics as transformative tools for clinical oncology.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas: enhanced sensitivity for stage I cancers through improved signal-to-noise ratio in cfDNA analysis, standardization of analytical pipelines across platforms and institutions, and the integration of methylation signatures with other molecular markers including mutations and fragmentomics patterns. Furthermore, the emergence of agentic AI systems that combine large language models with computational tools shows promise for automating complex bioinformatics workflows, though these approaches require further validation before clinical implementation [25].

As these technologies mature and evidence of clinical utility accumulates, methylation-based signal processing is poised to transition from research settings to routine clinical practice, ultimately fulfilling the promise of precision oncology through non-invasive, comprehensive molecular profiling.

The integration of advanced signal processing (SP) methods with genomic data is revolutionizing the early detection and classification of cancers. This case study explores the application of SP techniques for identifying DNA patterns in three major malignancies: lung, breast, and ovarian cancers. By analyzing complex genomic signatures through computational approaches, researchers can achieve unprecedented accuracy in cancer detection, often surpassing traditional biomarker-based methods. These advancements are particularly crucial for cancers where early detection significantly improves survival outcomes but has historically been challenging.

The following sections detail specific SP methodologies, their performance metrics across different cancer types, and the experimental protocols required to implement these cutting-edge approaches. We focus on techniques that analyze nucleotide sequences, fragmentomic patterns, and multi-omic integrations to demonstrate how signal processing transforms raw genomic data into clinically actionable information.

Key Methodologies and Performance Data

Recent research has yielded several promising SP-based approaches for cancer detection, each with distinct technical foundations and performance characteristics.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Featured SP-Based Cancer Detection Methods

| Cancer Type | Methodology | Core SP Feature | Sensitivity (Stage I) | Specificity | AUC | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer | Nucleotide Transition Probability [28] | First-Order Transition Probability (FOTP) in cfDNA | 73.9% | 95% | 0.942 | 1,036 participants |

| Breast Cancer | Blended Machine Learning [5] | DNA sequence classification via Logistic Regression + Gaussian NB | 98-100% (across types) | N/R | 0.99 (micro/macro avg) | 390 patients |

| Ovarian Cancer | AI-Powered Multi-Omic Platform [29] | Integrated lipid, ganglioside, and protein biomarkers | 89% (Stage I/II) | N/R | 0.89-0.92 | ~1,000 samples |

Table 2: Technical Implementation Details of Featured Methods

| Methodology | Data Input | Computational Framework | Key Advantages | Implementation Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide Transition Probability [28] | Plasma cfDNA, low-pass WGS | SVM classifier | High sensitivity for early-stage disease; Biologically interpretable features | Requires WGS capabilities |

| Blended Machine Learning [5] | Patient DNA sequences | Ensemble (Logistic Regression + Gaussian Naive Bayes) | Lightweight, interpretable model; Minimal feature requirement | Limited to trained cancer types |

| AI-Powered Multi-Omic Platform [29] | Blood-based lipids, gangliosides, proteins | Machine learning integration of multi-omic data | High accuracy in symptomatic population; Comprehensive molecular view | Complex assay requirements (LC-MS, immunoassays) |

| One-Shot Learning Framework [30] | Gene expression + mutational profiles | Siamese Neural Networks | Effective with limited samples; Handles unseen cancer types | Complex implementation; Requires explainability techniques |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Nucleotide Transition Probability Analysis for Lung Cancer Detection

Principle: This method detects lung cancer by analyzing nucleotide sequential dependencies within cell-free DNA fragments, leveraging the finding that the first 10 bp at the 5′ end harbor the most discriminative information for cancer detection [28].

Reagents and Materials:

- Blood collection tubes (cfDNA stable)

- cfDNA extraction kit

- Whole-genome sequencing library preparation kit

- Sequencing platform

Procedure:

- Sample Collection and Processing:

- Collect peripheral blood (10 mL) in cfDNA-stable blood collection tubes.

- Centrifuge at 1,600 × g for 10 min to separate plasma.

- Transfer plasma to microcentrifuge tubes and centrifuge at 16,000 × g for 10 min to remove residual cells.

cfDNA Extraction:

- Extract cfDNA from 1-5 mL plasma using commercial cfDNA extraction kits.

- Quantify cfDNA using fluorometric methods.

- Assess fragment size distribution using Bioanalyzer/TapeStation.

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Prepare sequencing libraries using 10-50 ng cfDNA.

- Perform low-pass whole-genome sequencing (0.5-1× coverage).

- Use 150 bp paired-end sequencing on preferred platform.

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Sequence Alignment: Align sequencing reads to reference genome (hg38) using optimized aligner.

- Feature Extraction: Calculate First-Order Transition Probability (FOTP) matrices for 5′ end 10 bp regions of all fragments.

- Model Application: Apply trained SVM classifier to FOTP features for cancer probability score.

- Interpretation: Scores >0.5 indicate high cancer probability; perform tissue-of-origin analysis if positive.

Quality Control:

- Include control samples in each batch

- Monitor sequencing quality metrics (Q30 >80%)

- Verify cfDNA fragment size distribution (peak ~167 bp)

Protocol 2: Multi-Omic Analysis for Ovarian Cancer Detection

Principle: This approach integrates multiple molecular data types (lipids, gangliosides, proteins) from blood samples using machine learning to detect ovarian cancer-specific signatures [29].

Reagents and Materials:

- Serum/plasma collection tubes

- Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry system

- Immunoassay platforms

- Standard protein biomarkers (CA125, HE4)

Procedure:

- Sample Collection:

- Collect peripheral blood from symptomatic patients.

- Process within 2 hours of collection to separate serum/plasma.

- Aliquot and store at -80°C until analysis.

Multi-Omic Data Generation:

- Lipidomics: Extract lipids using methanol:chloroform, analyze via LC-MS.

- Ganglioside Profiling: Perform targeted LC-MS analysis for ganglioside species.

- Protein Biomarkers: Measure CA125, HE4, and additional proteins via immunoassays.

Data Integration and Analysis:

- Normalize data across platforms using quality control samples.

- Apply pre-trained machine learning model to integrated multi-omic data.

- Generate probability score for ovarian cancer presence.

- For positive scores, provide sub-type and stage predictions.

Quality Control:

- Use standard operating procedures for all assays

- Include quality control pools in each batch

- Monitor instrument calibration and sensitivity

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

KRAS Signaling Pathway in Ovarian Cancer

Diagram 1: KRAS pathway and inhibition in low-grade serous ovarian cancer. The combination of avutometinib (RAF/MEK inhibitor) and defactinib (FAK inhibitor) blocks this oncogenic signaling pathway [31].

SP-Based Cancer Detection Workflow

Diagram 2: Generalized workflow for SP-based cancer detection, showing the common pipeline from sample to clinical report and the integration points for different SP methodologies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Implementation

| Category | Specific Product/Technology | Function in Protocol | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | cfDNA blood collection tubes (e.g., Streck, Roche) | Preserves cell-free DNA integrity | Critical for accurate fragmentomic analysis |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | Silica-membrane based cfDNA kits (e.g., QIAamp, MagMAX) | Isolves high-quality cfDNA | Maximize yield from limited plasma volumes |

| Sequencing | Low-pass WGS kits (e.g., Illumina, MGI) | Generates fragmentomic data | 0.5-1x coverage sufficient for FOTP analysis |

| Protein Biomarkers | CA125, HE4 immunoassays | Provides protein-level data | Essential for multi-omic integration |

| Lipidomics | LC-MS systems with lipid standards | Profiles lipid biomarkers | Requires specialized chromatography methods |

| Computational Tools | SVM classifiers, Siamese Neural Networks [30] | Analyzes SP features | Python/R implementations available |

| Data Integration | SHAP explainability frameworks [30] | Interprets model predictions | Critical for clinical translation |

Discussion

The SP-based methodologies detailed in this case study demonstrate significant advances in cancer detection, particularly for challenging malignancies like ovarian and lung cancers. The nucleotide transition probability approach achieves remarkable sensitivity for early-stage lung cancer (73.9% for Stage I) by focusing on subtle patterns in cfDNA fragment ends [28]. This method capitalizes on the biological finding that the first 10 bp at the 5′ end of cfDNA fragments contain discriminative information reflective of nuclease cleavage biases and chromatin features.

For ovarian cancer, the multi-omic platform represents a paradigm shift in detection strategies, integrating lipid, ganglioside, and protein biomarkers to achieve 89% sensitivity for early-stage disease in symptomatic women [29]. This approach is particularly valuable given the limitations of current diagnostic methods and the critical importance of early detection for this malignancy.

The blended machine learning approach for breast cancer classification exemplifies how ensemble methods can achieve near-perfect accuracy (98-100%) by combining the strengths of multiple algorithms [5]. Furthermore, the emerging one-shot learning framework addresses a critical challenge in cancer genomics: data scarcity for rare cancer types [30]. By using Siamese Neural Networks to learn similarity metrics rather than explicit classifications, this approach can generalize to unseen cancer types with minimal examples.

Implementation of these methods requires careful consideration of technical infrastructure, particularly for sequencing and computational analysis. However, the decreasing costs of genomic technologies and increasing accessibility of cloud computing resources make these approaches increasingly feasible for research and clinical applications. Future directions will likely focus on standardizing these methodologies, validating them in broader populations, and integrating them into routine clinical practice to improve cancer outcomes through earlier detection.

Multi-omics data integration represents a transformative framework in cancer research that combines multiple molecular datasets—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics—generated from the same patients to construct a comprehensive understanding of cancer biology [32]. This approach has emerged as a response to the recognized complexity of cancer, which operates through tightly connected components across multiple biological layers that cannot be fully understood by examining single molecular dimensions in isolation [33]. The integration of these disparate data types provides unprecedented opportunities to classify cancer subtypes, improve survival prediction, understand therapeutic resistance, and identify key pathophysiological processes through different molecular layers [32].

The paradigm shift toward multi-omics approaches has been enabled by parallel advancements in three critical areas: the development of high-throughput technologies in genomics and transcriptomics, increased large-scale research collaboration, and sophisticated computational algorithms capable of handling massive biological datasets [32]. Modern measurement platforms, including next-generation sequencing (NGS) and mass spectrometry techniques, now allow comprehensive profiling of somatic mutations, copy number variations, mRNA expression, non-coding RNA, protein expression, and metabolic profiles from the same set of tumor samples [34] [32]. This technological evolution, coupled with the application of signal processing methodologies traditionally used for modeling electronic and communications systems, has positioned multi-omics integration as a powerful approach for deciphering the complex genomic and epigenomic data characteristic of cancer systems biology [33].

Multi-Omics Components and Their Biological Significance

A multi-omics approach incorporates data from multiple molecular levels, each providing unique and complementary insights into cancer biology. The table below summarizes the core omics components commonly integrated in cancer studies, their descriptions, advantages, limitations, and primary applications.

Table 1: Core Components of Multi-Omics Approaches in Cancer Research

| Omics Component | Description | Pros | Cons | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|