RNA Sequencing for Gene Fusion Detection in Cancer: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) for detecting clinically relevant gene fusions in cancer.

RNA Sequencing for Gene Fusion Detection in Cancer: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) for detecting clinically relevant gene fusions in cancer. It explores the foundational role of gene fusions as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets, detailing methodological advances from targeted panels to long-read sequencing. The content addresses key challenges in troubleshooting and optimization, including sample preparation and bioinformatic pipelines. Finally, it synthesizes evidence from comparative validation studies, demonstrating how integrating RNA-seq with DNA-based methods significantly improves detection rates for actionable fusions, thereby advancing precision oncology and drug development.

Gene Fusions as Oncogenic Drivers: From Basic Biology to Clinical Actionability

Gene fusions, also known as chimeric genes, are hybrid genes formed when two previously separate genes become juxtaposed due to chromosomal rearrangements. These genomic alterations represent a critical class of somatic alterations in cancer, functioning as strong oncogenic drivers in numerous malignancies [1] [2]. The resulting fusion proteins can exhibit novel functional properties or altered expression patterns that disrupt normal cellular processes, ultimately leading to tumorigenesis. The clinical importance of gene fusions has grown substantially with the development of targeted therapies, making their detection crucial for optimal treatment selection [1].

The processes of tumorigenesis and development are intricate, involving numerous genes and molecular pathways. Fusion genes, as direct products of abnormal chromosomal rearrangements, are now recognized as key factors in the formation of many types of tumors [2]. In recent years, advancements in sequencing technology and bioinformatics have accelerated the discovery of fusion genes associated with specific tumor types, expanding our understanding of their roles in cancer biology and their potential as therapeutic targets.

Mechanisms of Gene Fusion Formation

Genomic Rearrangements Leading to Fusion Genes

Gene fusions arise through several distinct mechanisms of DNA rearrangement, each involving different types of chromosomal alterations [1]:

- Reciprocal Translocations: Interchromosomal exchange of DNA between regions, which can be equal (balanced) or unequal (unbalanced). An example is the SLC34A2-ROS1 fusion [1].

- Insertions: Inter- or intrachromosomal movement of a DNA fragment from one region to another.

- Deletions: Genomic deletions can bring separate genes into proximity, such as the ATG7-RAF1 fusion [1].

- Tandem Duplications: Duplicated genomic regions fuse with genes in their original region, exemplified by FGFR3-TACC3 in glioblastoma [1].

- Inversions: Segments of a chromosome flip relative to the centromere (pericentric) or not relative to the centromere (paracentric), such as KIF5B-RET [1].

- Chromothripsis: Catastrophic events involving fragmentation and inaccurate reassembly of one chromosome or chromosomal region [1].

The majority of oncogenic fusions are in-frame mutations that affect exonic regions of two protein-coding genes [1]. Interestingly, chimeric proteins can also arise without genomic rearrangement through mechanisms such as aberrant read-through transcription, where the transcription process does not properly terminate at the end of a gene and continues into the next gene (e.g., SCNN1A-TNFRSF1A) [1]. Fusion transcripts may also arise by trans or cis splicing of mRNA [1].

Functional Consequences of Gene Fusions

Oncogenic fusion proteins drive cancer development through several distinct mechanisms:

- Promoter-Driven Overexpression: Fusions can join a strong promoter that drives overexpression to a proto-oncogene (e.g., TRABD-DDR2), leading to downstream deregulation [1].

- Transcription Factor Activation: Fusions affecting transcription factors are important oncogenic drivers, exemplified by PML-RARα in leukemia, ETS gene fusions in prostate cancer, and PAX3-FOXO1 in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma [1].

- Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Activation: Rather than driving overexpression, some fusion proteins drive oncogenesis through constitutive activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) [1]. Examples include NRG1 ligand gene fusions and EGFR fusions, which trigger aberrant signaling pathways.

Table 1: Common Gene Fusion Types and Their Functional Consequences

| Fusion Type | Functional Consequence | Representative Examples | Primary Signaling Pathways Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinase Fusions | Constitutive kinase activation | BCR-ABL, EML4-ALK, TPM3-NTRK1 | PI3K/AKT, MAPK, JAK/STAT |

| Transcription Factor Fusions | Altered gene expression programs | PML-RARα, TMPRSS2-ERG, PAX3-FOXO1 | Cell differentiation, apoptosis |

| Ligand Fusions | Aberrant receptor activation | NRG1 fusions | ErbB signaling |

| Promoter Swap Fusions | Oncogene overexpression | IGH-FGFR3 | Various oncogenic pathways |

Oncogenic fusion proteins have been shown to drive or contribute to cancer development through both cell-autonomous and non-cell-autonomous mechanisms. For instance, in rhabdomyosarcoma, tumor cells with PAX3-FOXO1 fusion can modulate the tumor microenvironment to enhance cancer and recipient cell motility, favoring metastatic disease [1]. Similarly, cell-surface-bound NRG1 fusion proteins are thought to drive paracrine signaling via RTKs on neighboring cells [1].

Prevalence of Gene Fusions Across Malignancies

Hematologic Malignancies

Gene fusions were first discovered in hematologic malignancies, with the Philadelphia chromosome in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) representing the inaugural example [1]. This chromosomal abnormality, identified in 1960 and later found to arise from a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22, results in the BCR-ABL fusion gene [1]. This fusion generates a constitutively active tyrosine kinase that drives leukemogenesis and is found in almost all cases of CML [1].

Other significant fusions in hematologic cancers include PML-RARα in acute promyelocytic leukemia and various ALK fusions in anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL). The TPM3-ALK fusion, for instance, has been reported in ALCL, where it drives aberrant ALK expression closely associated with malignant transformation of lymphoid cells [3].

Solid Tumors

In solid tumors, gene fusions occur across a broad spectrum of malignancies. The first fusion reported in solid tumors was CTNNB1-PLAG1 in salivary gland adenoma [1]. Large-scale genomic studies have since revealed the extensive landscape of fusion genes across solid tumors.

A comprehensive analysis of 9,624 tumors across 33 cancer types identified 25,664 fusions, with a 63.3% validation rate using whole-genome sequencing data [4]. This study suggested that fusions drive the development of 16.5% of cancer cases and function as the sole driver in more than 1% of cases [4].

Table 2: Prevalence of Select Gene Fusions Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Fusion | Prevalence | Clinical Actionability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Myeloid Leukemia | BCR-ABL | ~100% [1] | FDA-approved TKIs |

| Prostate Adenocarcinoma | TMPRSS2-ERG | 38.2% [4] | Under investigation |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma | EML4-ALK | 1.0% [4] | FDA-approved ALK inhibitors |

| Thyroid Carcinoma | CCDC6-RET | 4.2% [4] | FDA-approved RET inhibitors |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | FGFR2-BICC1 | 5.6% [4] | FDA-approved FGFR inhibitors |

| Head and Neck Cancer | FGFR3-TACC3 | 2.8% overall fusion prevalence [5] | Potential target |

| Various Solid Tumors | NTRK fusions | 0.35% overall prevalence [6] | FDA-approved TRK inhibitors |

Recent large-scale studies have provided further insights into fusion prevalence. A 2025 pan-cancer analysis of 67,278 patients receiving both RNA- and DNA-based next-generation sequencing (NGS) found that 2.2% had at least one of nine fusions with FDA-approved matched therapies [7]. Notably, 29% of these fusions were detected outside of FDA-approved indications, highlighting the potential for expanding targeted therapy applications [7].

The prevalence of specific fusion types varies considerably across cancer types. For NTRK fusions, a real-world study of 19,591 solid tumor samples found an overall prevalence of 0.35%, with the highest frequencies in glioblastoma (1.91%), small intestine tumors (1.32%), and head and neck tumors (0.95%) [6].

Detection Methodologies for Gene Fusions

Traditional Detection Methods

Historically, gene fusions were detected using traditional methods that remain relevant in clinical practice:

- Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH): Allows visualization of chromosomal rearrangements using fluorescently labeled DNA probes.

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC): Detects aberrant protein expression patterns resulting from gene fusions.

While these methods have been widely used, they have limitations, particularly poor compatibility with multiplexing, which prevents simultaneous interrogation of multiple fusion genes [8].

Next-Generation Sequencing Approaches

The emergence of NGS technology has revolutionized fusion detection by enabling simultaneous sequencing of numerous genes in parallel [8]. Both DNA-based and RNA-based NGS approaches are employed, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

DNA-based NGS identifies genomic rearrangements at the DNA level but requires extensive coverage due to unpredictable breakpoints and potential blind spots within targeted areas [8].

RNA-based NGS detects expressed fusion transcripts, providing direct evidence of functionally relevant fusions. However, RNA is more susceptible to degradation, especially in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples [8].

Recent studies have demonstrated that combined DNA and RNA sequencing significantly improves fusion detection. A 2025 study showed that concurrent RNA- and DNA-based NGS increased the detection of driver gene fusions by 21% compared with DNA-NGS alone [7]. Another study developing an integrated DNA and RNA-based targeted sequencing assay reported 100% sensitivity and specificity in detecting fusions in clinical samples [8].

Protocol: Integrated DNA and RNA-Based NGS for Fusion Detection

The following protocol outlines an integrated approach for gene fusion detection using both DNA and RNA NGS:

Sample Preparation:

- Obtain FFPE tumor samples with minimum tumor purity of 30% [7].

- Extract total nucleic acids (both DNA and RNA) using commercial kits suitable for FFPE material.

- Assess DNA and RNA quality and quantity using appropriate methods.

Library Preparation:

- For DNA sequencing: Use hybrid capture-based panels covering intronic and exonic regions of target genes. The Tempus xT assay covers 648 genes with 500× coverage [7].

- For RNA sequencing: Use whole-transcriptome or targeted RNA-seq approaches. The Tempus xR assay provides whole-transcriptome RNA-seq [7].

- For targeted approaches: Custom-designed panels can focus on genes with known clinical relevance.

Sequencing and Analysis:

- Sequence libraries on appropriate NGS platforms.

- For DNA data: Use structural variant callers like LUMPY to identify genomic rearrangements [7].

- For RNA data: Apply fusion detection algorithms such as STAR-Fusion and Arriba [5].

- Integrate results from both DNA and RNA analyses to maximize sensitivity.

Validation:

- Confirm novel or uncertain fusions using orthogonal methods such as Sanger sequencing [8].

- Establish analytical validation through reference standards with known fusions [8].

This integrated approach has been shown to overcome the limitations of single-method approaches, with one study demonstrating that combined DNA and RNA sequencing identified a TPM3-NTRK1 fusion that was missed by DNA-only analysis [8].

Signaling Pathways Activated by Gene Fusions

Oncogenic fusion proteins typically activate key signaling pathways that drive tumorigenesis. The diagram below illustrates the major pathways activated by different types of gene fusions:

Diagram 1: Signaling Pathways Activated by Oncogenic Gene Fusions

The diagram above illustrates how different categories of gene fusions activate distinct signaling cascades that ultimately drive oncogenic processes. Kinase fusions typically activate multiple pathways simultaneously, including the RTK/RAS/MAPK, PI3K/AKT/mTOR, and JAK/STAT pathways, leading to enhanced cell proliferation and survival [1] [3]. Transcription factor fusions primarily alter gene expression programs, which can block differentiation and increase metastatic potential [1]. Ligand fusions, such as NRG1 fusions, activate receptor tyrosine kinase signaling through aberrant paracrine or autocrine mechanisms [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Gene Fusion Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | FFPE RNA/DNA extraction kits | Isolation of high-quality nucleic acids from archived specimens | Optimized for degraded FFPE material; include DNase/RNase treatment steps |

| Library Preparation Kits | Tempus xT (DNA), Tempus xR (RNA) [7] | Preparation of sequencing libraries | DNA panels should cover relevant intronic regions; RNA methods should capture fusion transcripts |

| Reference Standards | Commercial fusion standards (e.g., GeneWell) [8] | Assay validation and quality control | Contain known fusion variants at defined concentrations |

| Hybrid Capture Reagents | Custom bait panels | Enrichment of target genes | Design should include known and novel fusion partners |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | High-efficiency RT enzymes | cDNA synthesis for RNA-seq | Critical for obtaining full-length transcripts from degraded RNA |

| Sequencing Controls | Spike-in RNA controls, positive control samples | Monitoring technical performance | Should include samples with known fusion status |

| Analysis Software | STAR-Fusion, Arriba, EricScript [4] [5] | Bioinformatics detection of fusions | Use multiple algorithms to improve sensitivity/specificity |

| Orthogonal Validation Reagents | FISH probes, IHC antibodies, Sanger sequencing reagents | Confirmation of NGS findings | Essential for validating novel fusions |

Experimental Workflow for Fusion Detection

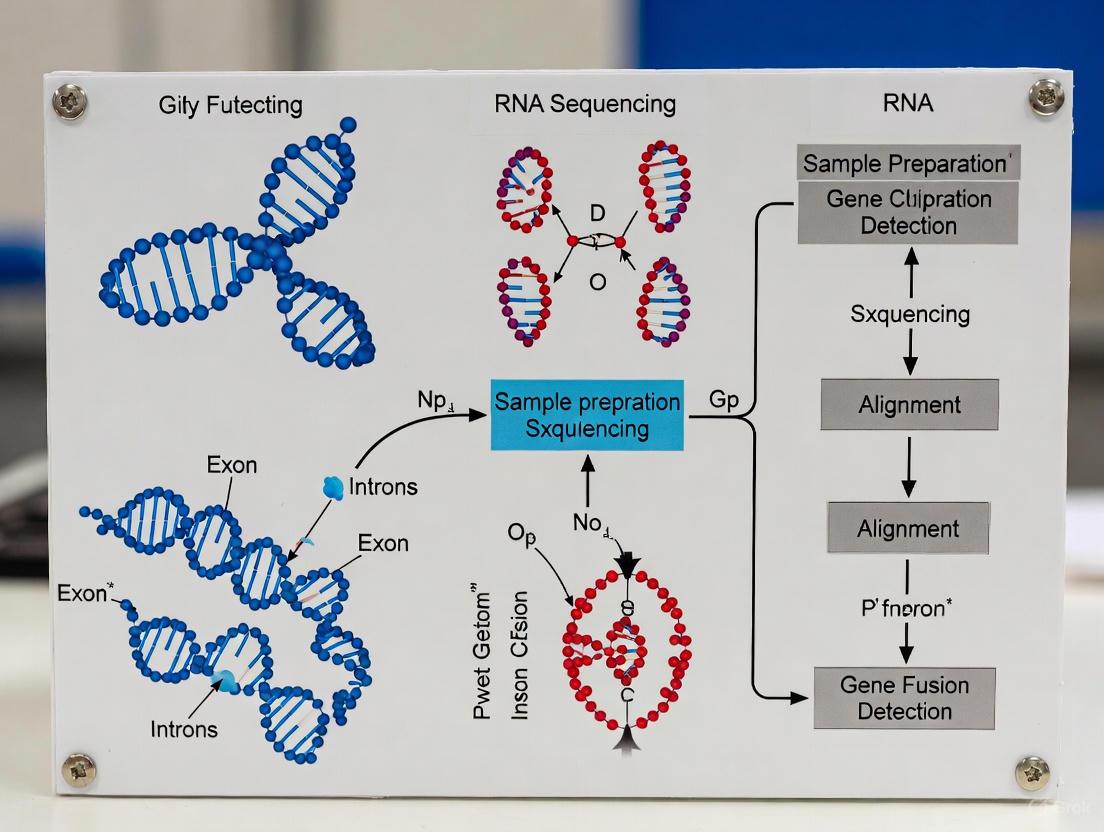

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for gene fusion detection integrating both DNA and RNA sequencing approaches:

Diagram 2: Integrated DNA and RNA Sequencing Workflow for Fusion Detection

This workflow highlights the importance of parallel DNA and RNA analysis to maximize detection sensitivity. Studies have demonstrated that this integrated approach increases the detection of actionable fusions by 21-127% compared to DNA sequencing alone [7]. The complementary nature of DNA and RNA sequencing helps overcome the limitations of each individual method - DNA sequencing can detect genomic rearrangements regardless of expression, while RNA sequencing confirms functionally expressed fusions and can identify events missed by DNA analysis due to breakpoint location or complexity [8].

Gene fusions represent critical oncogenic drivers across both hematologic malignancies and solid tumors. Understanding their mechanisms of formation, prevalence across cancer types, and the signaling pathways they activate is essential for advancing cancer research and therapy. The development of integrated detection methodologies combining DNA and RNA sequencing has significantly improved our ability to identify these important alterations, directly impacting therapeutic decisions and patient outcomes. As targeted therapies continue to advance, comprehensive fusion testing will play an increasingly vital role in precision oncology, enabling more patients to benefit from matched targeted treatments.

Oncogenic gene fusions are hybrid genes formed when two previously separate genes become juxtaposed through genomic rearrangements such as chromosomal translocations, inversions, deletions, or duplications [1]. These molecular events represent a critical class of oncogenic drivers across a broad spectrum of cancers, with profound implications for tumor initiation, progression, and therapeutic targeting [1]. Research indicates that gene fusions drive cancer development in approximately 16.5% of all cancer cases, playing a unique driving role in more than 1% of cases [9]. The clinical significance of these fusions stems from their dual role as defining diagnostic markers and actionable therapeutic targets, making their detection imperative for modern precision oncology.

The constitutive activation of tyrosine kinases through fusion events represents a common oncogenic mechanism. For instance, the BCR-ABL fusion in chronic myeloid leukemia and EML4-ALK fusion in non-small cell lung cancer result in aberrant, ligand-independent signaling that drives uncontrolled cellular proliferation and survival [1]. Beyond kinase activation, gene fusions can also drive oncogenesis through alternative mechanisms, including the juxtaposition of strong promoters that drive overexpression of proto-oncogenes or the creation of novel chimeric transcription factors that alter transcriptional programs [1]. The resulting fusion proteins can activate multiple critical signaling pathways, including PI3K-AKT, MAPK, and Rho GTPase pathways, establishing oncogenic addiction that can be therapeutically exploited [1].

Gene Fusions as Clinical Biomarkers

Diagnostic Biomarkers

Gene fusions serve as defining diagnostic markers for specific cancer types and subtypes, enabling precise pathological classification. The detection of particular gene fusions can distinguish histologically similar tumors and guide accurate diagnosis, which is fundamental for appropriate treatment selection [1]. Several fusion-driven cancers are now recognized as distinct entities in diagnostic classifications, including the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of tumors.

Table 1: Gene Fusions as Diagnostic Biomarkers in Specific Cancers

| Cancer Type | Diagnostic Fusion | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Chronic Myeloid Leukemia | BCR-ABL1 | Defining diagnostic marker [9] |

| Secretory Breast Cancer | ETV6-NTRK3 | Present in ~92% of cases; diagnostic biomarker [10] |

| Synovial Sarcoma | SS18-SSX | Characteristic marker [10] |

| Dermatofibrosarcoma Protuberans | COL1A1-PDGFB | Specific marker [10] |

| Ependymoma | RELA fusion | Distinct entity in WHO CNS tumor classification [10] |

| Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor | ALK fusions | Clarifies diagnosis due to high specific expression [11] |

| Lipofibromatosis-like Neural Tumor | NTRK1 fusions | Distinguishes from histologically similar lipofibromatosis [11] |

Predictive Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targeting

Gene fusions serve as powerful predictive biomarkers for response to targeted therapies. Cancers driven by fusion products, particularly those involving tyrosine kinases, often demonstrate remarkable responses to matched targeted agents, exemplifying the paradigm of precision oncology [1]. The predictive value of these fusions has led to the development of tumor-agnostic treatment approaches, where therapies are approved based on the molecular alteration rather than the tumor's tissue of origin.

The combined prevalence of actionable fusions with FDA-approved targeted therapies represents a significant proportion of cancer patients who can benefit from matched targeted treatments. A recent large-scale pan-cancer analysis of 67,278 patients found that 2.2% harbored at least one of nine fusions with an FDA-approved matched therapy, with RNA sequencing increasing the detection of these driver gene fusions by 21% compared to DNA sequencing alone [7]. Furthermore, 29% of these actionable fusions were detected outside of their FDA-approved indications, highlighting the potential for expanding targeted therapy benefits to additional patient populations [7].

Table 2: Clinically Actionable Gene Fusions and Approved Therapies

| Gene Fusion | Primary Cancer Types | Approved Targeted Therapies | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALK fusions | NSCLC, Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor | Crizotinib, Ceritinib, Alectinib [11] [1] | FDA-approved in specific indications |

| NTRK fusions | Multiple solid tumors (tumor-agnostic) | Larotrectinib, Entrectinib [1] | Tumor-agnostic FDA approval |

| RET fusions | NSCLC, Thyroid Cancer | Selpercatinib, Pralsetinib [11] [1] | FDA-approved in specific indications |

| ROS1 fusions | NSCLC | Crizotinib, Entrectinib [11] [1] | FDA-approved in specific indications |

| FGFR2/3 fusions | Cholangiocarcinoma, Bladder Cancer | Erdafitinib, Pemigatinib [1] [7] | FDA-approved in specific indications |

| NRG1 fusions | NSCLC, Pancreatic Cancer | Afatinib (under investigation) [1] | Clinical trials |

Prognostic Biomarkers

The prognostic significance of gene fusions varies considerably across different cancer types and specific fusion events. Some fusions are associated with more aggressive disease courses and worse outcomes, while others may define cancer subtypes with more favorable prognoses [1]. For instance, in pediatric thyroid cancers, patients with RET or NTRK fusions were more likely to have metastatic disease and worse outcomes compared to those with BRAF-mutant disease [1]. In contrast, FGFR2 fusions in cholangiocarcinoma were grouped in a cluster of genetic alterations with the best prognosis [1]. This variability underscores the importance of context-specific interpretation of the prognostic implications of gene fusions.

Analytical Approaches for Fusion Detection

RNA Sequencing Methodologies

RNA sequencing has emerged as a powerful tool for gene fusion detection due to its ability to directly detect expressed fusion transcripts. Several targeted and whole transcriptome sequencing approaches have been developed and validated for clinical use:

Targeted RNA Sequencing The FoundationOneRNA assay is a hybrid-capture-based targeted RNA sequencing test designed to detect fusions in 318 genes and measure expression of 1521 genes. Analytical validation demonstrated a positive percent agreement (PPA) of 98.28% and negative percent agreement (NPA) of 99.89% compared to orthogonal methods [12]. The assay successfully identified a low-level BRAF fusion missed by orthogonal whole transcriptome RNA sequencing, confirming its high sensitivity [12].

Whole Transcriptome Sequencing (WTS) A novel WTS assay for detection of gene fusions, MET exon 14 skipping, and EGFR vIII alterations achieved 98.4% sensitivity, correctly identifying 62 out of 63 known gene fusions with 100% specificity [10]. The assay established optimal performance thresholds at DV200 ≥ 30% for RNA degradation, >100 ng RNA input, >40 copies/ng fusion expression, and >80 million mapped reads [10].

Integrated DNA and RNA Sequencing Combining RNA sequencing with whole exome sequencing (WES) from a single tumor sample substantially improves detection of clinically relevant alterations. Applied to 2230 clinical tumor samples, this integrated approach enabled direct correlation of somatic alterations with gene expression, recovery of variants missed by DNA-only testing, and improved detection of gene fusions [13]. The combined assay uncovered clinically actionable alterations in 98% of cases and revealed complex genomic rearrangements that would likely have remained undetected without RNA data [13].

Experimental Protocol: RNA Sequencing for Fusion Detection

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

- Nucleic Acid Isolation: Extract RNA from FFPE tissues using commercially available kits (e.g., RNeasy FFPE Kit, Qiagen). For optimal results, use sections from tissue stored at 4°C for less than one year with tumor content exceeding 20% [10].

- RNA Quality Assessment: Quantify RNA using NanoDrop 8000 and Qubit 3.0. Assess integrity via Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer system. Establish DV200 ≥ 30% as the threshold for acceptable RNA quality [10].

- rRNA Depletion: Remove ribosomal RNA using NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit to enrich for mRNA and fusion transcripts of interest.

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Library Construction: Use NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit with custom adaptors and index primers. For highly degraded samples (DV200 ≤ 50%), omit the fragmentation step [10].

- Library Quality Control: Quantify libraries using Qubit 3.0 and assess quality with LabChip GX Touch system.

- Sequencing: Perform sequencing on platforms such as Illumina NovaSeq 6000 or comparable systems. Generate approximately 25 gigabases of 100 bp paired-end reads per sample [10].

Bioinformatic Analysis

- Alignment: Map sequencing reads to the reference genome (hg38) using STAR aligner or similar tools [13].

- Fusion Calling: Implement ensemble methods integrating multiple fusion detection algorithms (e.g., STAR-Fusion, Mojo) to improve accuracy [7].

- Filtering and Annotation: Apply filters based on supporting read count, expression levels, and known false-positive patterns. Annotate candidate fusions using databases such as FusionGDB and ChimerDB [10].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for RNA Sequencing-Based Fusion Detection

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | RNeasy FFPE Kit (Qiagen), AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit | Nucleic acid isolation from challenging FFPE samples [13] [10] |

| RNA Quality Control | Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, TapeStation 4200, Qubit assays | Assessment of RNA integrity, quantity, and suitability for sequencing [13] [10] |

| Library Prep Kits | NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit, TruSeq stranded mRNA kit | Construction of sequencing libraries from RNA templates [13] [10] |

| rRNA Depletion | NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit | Removal of ribosomal RNA to enrich for coding transcripts [10] |

| Target Capture | SureSelect XTHS2 RNA kit (Agilent) | Hybrid-capture enrichment for targeted RNA sequencing approaches [13] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq 6000, Gene+ seq 2000 | High-throughput sequencing of RNA libraries [13] [10] |

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Oncogenic fusion proteins drive cancer development through multiple mechanisms, most commonly by constitutively activating tyrosine kinase signaling or altering transcriptional programs. The diagram below illustrates the key signaling pathways activated by oncogenic gene fusions and their downstream effects.

The molecular mechanisms of fusion-driven oncogenesis extend beyond cell-autonomous signaling. Fusion-positive cancer cells can modulate the tumor microenvironment through paracrine signaling. For example, in rhabdomyosarcoma, PAX3-FOXO1 fusion alters exosome content, driving pro-tumorigenic signaling in recipient cells [1]. Similarly, cell-surface-bound NRG1 fusion proteins can drive paracrine signaling via RTKs on neighboring cells [1]. These microenvironmental effects highlight the broad impact of oncogenic fusions on tumor biology.

Integrated Detection Workflow

The accurate detection of clinically relevant gene fusions requires an integrated approach that combines DNA and RNA sequencing methodologies. The workflow below illustrates the complementary nature of these technologies in identifying fusion events.

The complementary nature of DNA and RNA sequencing is evidenced by multiple studies demonstrating that combined approaches significantly improve fusion detection rates. In a large pan-cancer analysis, concurrent RNA and DNA sequencing increased the detection of driver gene fusions by 21% compared with DNA sequencing alone [7]. Similarly, a targeted sequencing study found that integrated DNA and RNA testing could identify fusions that would be missed by either method alone, with DNA and RNA assays independently showing false-negative rates that were compensated for by the complementary method [11].

The comprehensive characterization of gene fusions as diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarkers represents a cornerstone of modern precision oncology. The integration of RNA sequencing with DNA-based genomic profiling has demonstrated significant improvements in detection sensitivity, with combined approaches identifying actionable alterations in up to 98% of cases [13]. As the landscape of fusion-targeted therapies continues to expand, with tumor-agnostic approvals for NTRK and RET functions and ongoing investigations for numerous other targets, the clinical imperative for robust fusion detection will only intensify.

Future developments in fusion detection technology, including long-read transcriptome sequencing and advanced computational methods like GFvoter, promise further enhancements in detection accuracy [9]. Meanwhile, the growing recognition of fusions occurring outside their classic indications highlights the importance of comprehensive molecular profiling across diverse cancer types. As biomarker-driven treatment strategies continue to evolve, the systematic implementation of integrated DNA and RNA sequencing approaches will be essential for maximizing therapeutic opportunities for cancer patients harboring these clinically significant genomic alterations.

Oncogenic gene fusions are hybrid genes arising from chromosomal rearrangements such as translocations, inversions, deletions, or tandem duplications, and represent a critical class of therapeutic targets in precision oncology [1]. These fusion events can result in constitutive activation of tyrosine kinases or aberrant expression of transcription factors, driving uncontrolled cell proliferation and survival through the disruption of key signaling pathways including RAS/MAPK, PI3K/AKT, and JAK/STAT [14] [1]. The detection of these fusions has become essential for optimal cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection, particularly with the development of highly effective targeted therapies.

RNA sequencing has emerged as a powerful tool for fusion detection, offering several advantages over DNA-based approaches and traditional methods like FISH and IHC. While DNA-based NGS can identify genomic rearrangements, it often struggles with large intronic regions where breakpoints frequently occur. RNA-seq directly captures the expressed fusion transcript, providing functional evidence of the rearrangement and confirming the maintenance of the reading frame and integrity of kinase domains [14] [7]. The clinical utility of comprehensive fusion profiling is underscored by real-world data showing that concurrent RNA and DNA sequencing increases the detection of clinically actionable fusions by 21-127% compared to DNA sequencing alone [7].

Landscape of Key Targetable Fusions

Prevalence and Clinical Characteristics

The prevalence of targetable fusions varies significantly across cancer types, with some occurring at high frequencies in specific rare tumors while appearing at lower frequencies across more common malignancies. The table below summarizes the prevalence and clinical characteristics of key oncogenic fusions.

Table 1: Prevalence and Characteristics of Key Oncogenic Fusions

| Fusion | Prevalence in NSCLC | Other Cancer Types with Significant Prevalence | Common Fusion Partners | Clinical Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALK | 3-8% [14] | Anaplastic Large Cell Lymphoma (50-80%) [14]; Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumors (50-60%) [14] | EML4, STRN, NPM1, TPM3 [14] | Oncogenic addiction to ALK signaling; responsive to TKIs [14] |

| RET | 1-2% [15] | Papillary Thyroid Carcinoma [11] | KIF5B, CCDC6 [11] | Higher proportion of never smokers (36%) and adenocarcinoma histology (88%) [15] [16] |

| ROS1 | 1-2% [17] | - | CD74, SLC34A2 [11] | - |

| NTRK1/2/3 | <1% [6] | Glioblastoma (1.91%) [6]; Small Intestine (1.32%) [6]; Secretory Breast Carcinoma (>90%) [6] | ETV6, TPM3, LMNA [6] | Tumor-agnostic FDA approvals; often mutually exclusive with other drivers [6] |

Signaling Pathways of Oncogenic Fusions

Oncogenic fusions involving receptor tyrosine kinases typically result in constitutive activation of downstream signaling cascades that promote cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation. The diagram below illustrates the common signaling pathways activated by ALK, RET, ROS1, and NTRK fusions.

RNA Sequencing Methodologies for Fusion Detection

Comparison of RNA Sequencing Approaches

Multiple RNA-based NGS approaches have been developed for fusion detection, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The selection of an appropriate methodology depends on factors including the required sensitivity, need for novel fusion discovery, cost considerations, and sample quality.

Table 2: Comparison of RNA Sequencing Methodologies for Fusion Detection

| Methodology | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Representative Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Transcriptome Sequencing (WTS) | Sequencing of all polyadenylated RNA transcripts | Unbiased detection of known and novel fusions; comprehensive biomarker analysis [14] | Complex bioinformatic analysis; low sensitivity for fusions with low expression [14] | Standard RNA-seq protocols |

| Hybrid-Capture-Based RNA Sequencing | Solution-based hybridization to target transcripts using bait panels | High sensitivity for known fusions; robust performance with FFPE samples [6] [18] | Limited to pre-designed targets; may miss novel partners outside panel [6] | Tempus xR [7]; Illumina RNA Panels [6] |

| Amplicon-Based RNA Sequencing | Multiplex PCR amplification of target regions | High sensitivity for known targets; cost-effective [14] | Limited to predefined targets; false positives from primer artifacts [18] | TruSight RNA Fusion Panel [14]; OncoFu Elite [14] |

| Anchored Multiplex PCR | Gene-specific priming combined with universal adapters | Ability to detect fusions with unknown partners; requires less input RNA [14] | Limited by primer design; may miss some fusion variants | FusionPlex [14] |

Integrated DNA-RNA Sequencing Workflow

The most comprehensive approach for fusion detection involves parallel sequencing of both DNA and RNA from tumor samples. This integrated workflow maximizes sensitivity and specificity while providing complementary information about genomic rearrangements and their functional transcriptional consequences.

Protocol: RNA Hybrid-Capture Sequencing for Fusion Detection

Principle: This protocol utilizes biotinylated oligonucleotide probes to enrich for target RNA sequences prior to sequencing, enabling highly sensitive detection of fusion transcripts even in degraded FFPE samples [6].

Sample Requirements:

- Input: 50-100ng total RNA from FFPE tissue

- Quality: DV200 ≥ 30% (percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides)

- Tumor Purity: ≥ 20% tumor content recommended

Procedure:

RNA Quality Control

- Assess RNA quantity and quality using fluorometric methods

- Determine RNA integrity (DV200) using Bioanalyzer or TapeStation

Library Preparation

- Perform ribosomal RNA depletion using commercially available kits

- Convert RNA to cDNA using reverse transcriptase with random primers

- Synthesize second strand to create double-stranded cDNA

Hybrid Capture Enrichment

- Fragment cDNA to 200-300bp using acoustic shearing

- Add Illumina-compatible adapters with unique dual indexes

- Hybridize with biotinylated probe library (e.g., comprehensive fusion panel)

- Capture target regions using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads

- Wash to remove non-specifically bound fragments

Sequencing

- Amplify captured libraries with 10-12 PCR cycles

- Quantify libraries by qPCR

- Pool libraries at equimolar ratios

- Sequence on Illumina platform (minimum 20 million 2x75bp reads per sample)

Bioinformatic Analysis

- Align reads to reference genome (GRCh38) using STAR or HISAT2

- Detect fusion transcripts using multiple algorithms (STAR-Fusion, Arriba, FusionCatcher)

- Filter against database of normal samples and common artifacts

- Annotate fusions with clinical significance (OncoKB, CIViC)

Quality Control Metrics:

- Minimum sequencing depth: 20 million reads

- Target coverage: >80% of targets at 100x

- Fusion supporting reads: ≥5 unique reads spanning breakpoint

- Expression level: TPM ≥1 for 3' gene

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Fusion Detection Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| NGS Library Prep Kits | Illumina TruSight RNA Fusion Panel; Archer FusionPlex | Target enrichment and library preparation for RNA sequencing | Archer uses anchored multiplex PCR; Illumina uses hybrid capture [14] |

| Reference Standards | GeneWell Fusion Reference Standards (contain 10 fusions across ALK, ROS1, RET, NTRK) [11] | Assay validation and quality control | Essential for establishing limit of detection (5% for DNA, 250-400 copies for RNA) [11] |

| Hybrid Capture Panels | Tempus xR (whole transcriptome); Labcorp CGP Panel | Comprehensive fusion detection via RNA baits | Labcorp panel identified 73 NTRK fusions in 19,591 samples (0.35% prevalence) [6] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | STAR-Fusion; Arriba; AGFusion; FusionCatcher | Fusion detection from RNA-seq data | Ensemble approaches combining multiple algorithms improve accuracy [7] |

| Validation Reagents | FISH probes; IHC antibodies; Sanger sequencing | Orthogonal validation of NGS findings | Critical for confirming novel fusions and borderline positive cases [11] |

Therapeutic Implications and Resistance Mechanisms

Approved Targeted Therapies

The identification of oncogenic fusions has led to the development of highly effective targeted therapies, with several receiving FDA approval in both tumor-agnostic and indication-specific contexts.

Table 4: Approved Targeted Therapies for Oncogenic Fusions

| Fusion | Approved Therapies | Approval Context | Clinical Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALK | Crizotinib, Ceritinib, Alectinib [11] | NSCLC-specific | Standard care in ALK+ NSCLC [14] |

| RET | Selpercatinib, Pralsetinib [19] [15] | Tumor-agnostic for RET fusions | Pralsetinib: ORR 70.3%, mPFS 13.1 mos, mOS 44.3 mos [19] |

| NTRK | Larotrectinib, Entrectinib, Repotrectinib [6] | Tumor-agnostic for NTRK fusions | Larotrectinib: ORR 79% [6]; Entrectinib: ORR 61.2% [6] |

| ROS1 | Crizotinib, Entrectinib [11] | NSCLC-specific | - |

Resistance Mechanisms and Next-Generation Inhibitors

Despite initial efficacy, resistance to targeted therapies inevitably develops through multiple mechanisms. Understanding these pathways is essential for developing sequential treatment strategies.

Resistance Mechanisms:

- On-target mutations: Secondary mutations in the kinase domain that impair drug binding (e.g., ALK G1202R, RET G810X gatekeeper mutations) [19]

- Off-target bypass: Activation of alternative signaling pathways (e.g., HER3-mediated ERK reactivation following RET inhibition) [19]

- Histologic transformation: Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition or conversion to small cell lung cancer morphology

Emeritting Therapeutic Strategies:

- Next-generation inhibitors: Vepafestinib (RET-selective) shows activity in treatment-naïve and pretreated patients with RET-altered cancers [19]

- Combination therapies: Pan-HER inhibitor afatinib combined with selpercatinib overcomes YAP-driven HER3-mediated resistance in RET-altered cancers [19]

- CNS-penetrant agents: FHND5071 (selective RET inhibitor) demonstrates high brain penetration and 100% CNS ORR in patients with brain metastases [19]

Emerging Directions and Future Applications

Novel Detection Modalities

Artificial Intelligence in Fusion Prediction: Deep learning models applied to H&E-stained whole slide images can predict ALK and ROS1 fusions with ROC AUCs of 0.84-0.85, serving as potential prescreening tools before confirmatory molecular testing [17]. These vision transformer models utilize a two-step training approach, first learning general cancer morphology patterns before specializing in specific fusion prediction.

Liquid Biopsy Applications: While not extensively covered in the current search results, circulating tumor DNA and RNA analyses are emerging as non-invasive methods for fusion detection and resistance monitoring, particularly valuable when tissue biopsies are impractical.

Expanding Therapeutic Landscapes

The future of fusion-targeted therapy includes several promising directions:

- Pan-fusion inhibitors: Drugs targeting common structural features of multiple fusion kinases

- Combination regimens: Rational pairing of fusion-directed therapy with complementary pathway inhibitors to delay resistance

- Degradation strategies: PROTACs and other targeted protein degradation approaches for complete oncoprotein elimination

- Immunotherapy combinations: Exploring synergy between targeted therapies and immune checkpoint inhibitors in selected contexts

The comprehensive detection of oncogenic fusions through RNA sequencing represents a critical component of precision oncology. The integration of multiple testing modalities, particularly combined DNA and RNA sequencing, significantly enhances detection rates of these therapeutic targets. As the field advances, the ongoing development of more sensitive detection methods, novel therapeutic agents, and sophisticated resistance-management strategies will continue to improve outcomes for patients with fusion-driven cancers. Research and clinical practice must prioritize comprehensive molecular profiling to fully realize the potential of targeted therapies across the spectrum of oncogenic fusions.

The identification of oncogenic gene fusions is critical for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and targeted treatment selection. For years, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), immunohistochemistry (IHC), and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) have served as cornerstone techniques in clinical molecular pathology. However, as our understanding of cancer genomics expands, significant limitations of these traditional methods have emerged. Within the broader thesis on the superiority of RNA sequencing for gene fusion detection, this application note systematically details the technical and clinical constraints of FISH, IHC, and RT-PCR, supported by quantitative performance data and experimental protocols. The transition toward comprehensive genomic approaches like RNA-based next-generation sequencing (NGS) is becoming increasingly necessary to fully realize the potential of precision oncology.

Performance Comparison of Traditional Detection Methods

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and limitations of FISH, IHC, and RT-PCR based on current clinical studies.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Traditional Gene Fusion Detection Methods

| Method | Typical Applications | Key Advantages | Major Limitations | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FISH | Detection of ALK, ROS1, RET rearrangements in NSCLC [20] | Single-cell resolution; partner-agnostic [21] | Limited multiplexing capability; subjective interpretation; inability to identify fusion partners or breakpoints [21] [11] | ~70-99% (varies by gene and platform) [22] | ~80-99% (varies by gene and platform) [22] |

| IHC | Protein expression analysis; ALK, HER2 status detection [20] [23] | Low cost; rapid turnaround; preserves tissue architecture [22] | Variable sensitivity/specificity dependent on antibody and fusion partner; semi-quantitative [21] | ~60% for RET [21]; 97% for HER2 (AI-assisted) [23] | 40-85% for RET [21]; 82% for HER2 (AI-assisted) [23] |

| RT-PCR | Known fusion variant detection (e.g., EML4-ALK) [22] | Rapid; high sensitivity for known fusions; works with limited tissue [22] | Cannot detect novel fusion partners; susceptible to RNA degradation [11] [24] | 100% (ALK vs FISH/Sequencing) [22] | 94% (ALK vs FISH/Sequencing) [22] |

Detailed Methodological Limitations and Protocols

Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

Experimental Protocol for FISH-Based Fusion Detection:

- Sample Preparation: Cut 4-5 μm sections from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks and mount on charged slides.

- Deparaffinization and Pretreatment: Bake slides at 56°C for 4 hours, deparaffinize in xylene, and hydrate through graded ethanols.

- Pretreatment: Incubate in pretreatment solution (1M sodium thiocyanate) at 80°C for 30 minutes, then protease digest (pepsin in 0.2N HCl) at 37°C for 15-30 minutes.

- Denaturation and Hybridization: Denature target DNA and probe mixture at 85°C for 5 minutes, then hybridize at 37°C for 12-16 hours using break-apart FISH probes.

- Post-Hybridization Washes: Wash in 2× SSC/0.3% NP-40 at 75°C for 5 minutes, then counterstain with DAPI.

- Analysis: Score 50-100 tumor cells using fluorescence microscopy; positive result indicated by >15% cells with split signals [21] [22].

Key Limitations: FISH demonstrates particularly poor performance for pericentric fusions where partner genes are located close together (e.g., KIF5B and RET on chromosome 10) [21]. The method cannot identify the specific fusion partner, which has emerging clinical relevance for predicting treatment response [21]. Furthermore, FISH requires specialized expertise for interpretation, lacks standardized cutoff criteria across laboratories, and may yield positive results that are not confirmed at the transcript level [21].

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Experimental Protocol for IHC-Based Fusion Protein Detection:

- Sectioning and Deparaffinization: Cut 4 μm FFPE sections, bake at 60°C for 1 hour, and deparaffinize through xylene and graded alcohols.

- Antigen Retrieval: Heat slides in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) or EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) using a pressure cooker or steamer for 20-30 minutes.

- Primary Antibody Incubation: Apply validated primary antibodies (e.g., D5F3 for ALK, 5A4 for ALK) for 60 minutes at room temperature [22].

- Detection and Visualization: Use enzyme-conjugated secondary antibodies and chromogenic substrates (DAB) for signal development.

- Counterstaining and Interpretation: Counterstain with hematoxylin, dehydrate, and mount. Score based on staining intensity and distribution [22] [23].

Key Limitations: IHC sensitivity is highly dependent on the specific fusion partner. For RET fusions, sensitivity ranges from 100% for KIF5B-RET to approximately 50% for NCOA4-RET [21]. The method suffers from significant inter-observer variability, with studies showing substantial discordance between laboratories due to lack of standardization in reagents and training [22]. While artificial intelligence approaches are emerging to address these limitations, they require further validation before widespread clinical implementation [23].

Reverse Transcription PCR (RT-PCR)

Experimental Protocol for RT-PCR Fusion Detection:

- RNA Extraction: Isolate total RNA from FFPE tissues using commercial kits with DNase treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- RNA Quality Assessment: Determine RNA concentration and quality using spectrophotometry and fragment analysis (DV200 ≥ 30% recommended) [24].

- cDNA Synthesis: Convert 100-500 ng of total RNA to cDNA using reverse transcriptase with random hexamers or gene-specific primers.

- PCR Amplification: Perform quantitative PCR using primers targeting specific fusion junctions (e.g., EML4-ALK variants) with appropriate cycling conditions.

- Result Interpretation: Use ΔCt cut-off values (e.g., ΔCt ≤8 for ALK detection) for positive calls; confirm positive results with sequencing when possible [22].

Key Limitations: RT-PCR is fundamentally limited to detecting known fusion variants with predefined breakpoints [11]. The requirement for intact, high-quality RNA presents significant challenges with FFPE specimens, where RNA is often degraded [24]. The method's sensitivity decreases dramatically when fusion transcripts are expressed at low levels or when the RNA input is below optimal levels (typically <250-400 copies/100 ng) [11].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Consequences

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental difference in what each traditional detection method actually measures in the central dogma of molecular biology.

Diagram Title: What Traditional Methods Detect in Molecular Pathology

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Traditional Fusion Detection Methods

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| FISH Probes | Vysis ALK Break Apart FISH Probe Kit (Abbott Molecular) [22] | Designed to detect ALK rearrangements regardless of partner; requires fluorescence microscopy and specific expertise for interpretation |

| IHC Antibodies | Ventana ALK (D5F3) CDx Assay; Novocastra 5A4 (Leica) [22] | Clone D5F3 is FDA-approved companion diagnostic; 5A4 is widely validated; both require standardized antigen retrieval and detection systems |

| RNA Extraction Kits | RNeasy FFPE Kit (Qiagen) [24] | Critical for RT-PCR and RNA-based methods; includes DNase treatment step to remove genomic DNA contamination |

| RT-PCR Kits | ALK RGQ RT-PCR Kit (QIAGEN) [22] | Single-tube quantitative real-time PCR assay for automated ALK expression interpretation; requires high-quality RNA input |

| Control Materials | Commercial fusion reference standards (e.g., GeneWell) [11] | Contain spiked-in fusion transcripts (EML4::ALK, CD74::ROS1, CCDC6::RET) for assay validation and quality control |

The limitations of traditional gene fusion detection methods - including limited multiplexing capability, inability to detect novel fusions, variable sensitivity and specificity, and technical challenges with sample quality - present significant constraints in the era of precision oncology. While FISH, IHC, and RT-PCR remain valuable for specific clinical scenarios, their individual shortcomings highlight the necessity for more comprehensive approaches. RNA-based next-generation sequencing emerges as a powerful solution that overcomes these limitations, enabling simultaneous detection of known and novel fusions across multiple genes with high sensitivity and specificity. The integration of advanced computational methods and multi-analyte approaches will further enhance the detection of clinically relevant gene fusions, ultimately improving patient outcomes through more accurate diagnosis and targeted treatment selection.

RNA-Seq Methodologies in Focus: From Targeted Panels to Long-Read Sequencing

Gene fusions represent a critical class of molecular alterations in cancer, serving as diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarkers for targeted therapies. The detection of these transcripts in clinical specimens, particularly formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue, presents significant technical challenges. Targeted RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has emerged as a powerful solution, offering enhanced sensitivity and specificity for fusion detection compared to whole transcriptome approaches. This application note details the fundamental design principles, experimental protocols, and validation frameworks for developing targeted RNA-Seq panels specifically optimized for capturing fusion transcripts in cancer research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive guide for implementing this technology in both basic and translational settings.

Gene fusions are hybrid genes formed through chromosomal rearrangements including translocations, deletions, inversions, or duplications. These molecular events can result in the expression of chimeric proteins with oncogenic properties or place proto-oncogenes under the control of strong promoter elements, driving tumorigenesis. Approximately one-third of soft tissue tumors and a wide array of other solid tumors harbor clinically relevant gene fusions [11]. Notably, fusions involving genes such as ALK, ROS1, RET, and NTRK family members have been well-characterized and serve as biomarkers for matched targeted therapies that have demonstrated remarkable clinical efficacy [11] [25].

The accurate detection of fusion transcripts is therefore paramount in modern cancer research and precision oncology. While traditional methods like fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) remain in use, they are limited by poor compatibility with multiplexing, preventing simultaneous interrogation of multiple fusion genes [11] [26]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, particularly RNA-Seq, enable comprehensive profiling of fusion transcripts. However, the low quality and fragmented nature of RNA extracted from FFPE samples—the standard in pathology—poses a substantial challenge for sequencing assays [11] [26] [27]. Targeted RNA-Seq addresses these limitations by focusing sequencing power on specific genes of interest, thereby improving sensitivity, reducing costs, and enabling robust analysis of degraded samples typical in clinical research.

Design Principles for Targeted RNA-Seq Fusion Panels

Core Design Strategies: Amplicon vs. Hybridization Capture

Targeted RNA-Seq employs two primary strategies to enrich for specific RNA transcripts: amplicon sequencing and hybridization capture [28].

- Amplicon Sequencing (PCR-based): This approach uses multiple pairs of primers to selectively amplify target RNA regions through PCR. It is highly sensitive and requires less input RNA, making it suitable for fragmented FFPE-derived RNA. A key consideration is careful primer design to avoid gaps in coverage that could miss breakpoints in fusion events [28].

- Hybridization Capture: This method uses biotin-labeled oligonucleotide probes complementary to the target regions to pull down RNA fragments of interest from a complex library. While potentially offering more uniform coverage and flexibility in panel design, it generally requires higher input RNA and longer intact fragments, which can be a limitation for degraded FFPE samples [28].

The choice between these methods depends on the research application, sample quality, and the desired balance between sensitivity, specificity, and coverage.

Gene Content Selection

The selection of genes to include in a panel is driven by the research context. A well-designed panel should include:

- Clinically Actionable Oncogenes: Genes with established roles as therapeutic targets, such as ALK, ROS1, RET, NTRK1/2/3, FGFRs, and BRAF [11] [26] [28].

- Tumor-Type Specific Fusions: Genes recurrently fused in specific cancers, such as SS18-SSX in synovial sarcoma, EWSR1-FLI1 in Ewing's sarcoma, and TMPRSS2-ERG in prostate cancer [25] [26].

- 5' and 3' Partner Gene Coverage: Since the identity of the fusion partner can influence treatment response, panels should be designed to detect both known and novel partners for key driver genes.

Optimization for FFPE-Derived RNA

FFPE processing causes RNA fragmentation and chemical modification, making downstream analysis difficult [11] [26]. Key design adaptations include:

- Short Amplicon Design: Designing amplicons to be short (100-250 bp) to accommodate the fragmented nature of FFPE RNA and ensure efficient amplification and sequencing [28].

- High Target Capture Efficiency: Optimizing probe or primer sequences to ensure high efficiency in capturing degraded RNA, thereby maximizing the yield of informative sequences.

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Workflow

The following section outlines a standard workflow for fusion detection using a targeted RNA-Seq approach, from sample preparation to data analysis.

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

- RNA Extraction: Total RNA is extracted from biological samples (e.g., FFPE tissue sections, cells) using specialized kits for FFPE material (e.g., Maxwell RSC RNA FFPE Kit) [26]. The integrity of the extracted RNA should be checked using a bioanalyzer, though traditional RNA Integrity Number (RIN) is often low for FFPE samples; concentration is therefore a more critical parameter.

- RNA Fragmentation: While RNA from FFPE is already fragmented, further controlled fragmentation (physical or enzymatic) may be performed to achieve a uniform size distribution of around 100-500 bases [28].

Library Preparation for Targeted RNA-Seq

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Library Preparation

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| FusionPlex Solid Tumor Kit (ArcherDX) | Multiplex PCR-based library preparation for fusion detection. | Validated for FFPE samples; includes panels for sarcoma and carcinoma [26]. |

| Biotin-labeled Probes | Hybridization and capture of target RNA sequences. | Used in capture-based targeted sequencing; require careful design for specificity [28]. |

| Streptavidin Magnetic Beads | Enrichment of probe-bound target RNA fragments. | Essential for post-hybridization wash and capture in hybridization-based methods [28]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA) from RNA templates. | First step in converting captured RNA into a sequencer-compatible library. |

| Platform-specific Adapters | Enable binding of library fragments to sequencing flow cells. | Contain indices for sample multiplexing. |

The library preparation process varies by method but generally follows these steps:

- Reverse Transcription: The enriched or selected RNA fragments are reverse-transcribed into cDNA.

- Target Enrichment:

- For Amplicon-based: A multiplex PCR is performed using primers designed for the targeted genes.

- For Hybridization Capture: The cDNA is hybridized with the custom probe panel, and non-target sequences are washed away.

- Adapter Ligation & Amplification: Sequencing adapters are ligated to the cDNA fragments, followed by a limited number of PCR cycles to amplify the final library.

- Library QC: The quality and concentration of the final library are quantified using methods such as qPCR or bioanalyzer profiling.

Sequencing and Data Analysis

- Sequencing: The pooled libraries are sequenced on a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina), typically generating paired-end reads. A minimum of 10-20 million reads per sample is often sufficient for targeted panels.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: The resulting FASTQ files are processed through a specialized pipeline:

- Quality Control & Trimming: Tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt remove low-quality bases and adapter sequences [29].

- Alignment: Processed reads are aligned to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using splice-aware aligners such as STAR.

- Fusion Calling: Dedicated algorithms identify chimeric transcripts. Using at least two tools is recommended to improve accuracy [30] [26]. Commonly used tools include:

- Arriba (ARR): A fast and sensitive fusion detection algorithm with high sensitivity for druggable fusions [30] [26].

- STAR-Fusion (SFU): A widely used tool based on the STAR aligner, known for its high accuracy [30] [26].

- CTAT-LR-Fusion: A tool designed for long-read RNA-Seq data, useful for resolving complex isoforms [25].

- Annotation and Filtering: Called fusions are filtered against databases of known artifacts, normal genomic variations, and annotated for clinical relevance.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the complete process from sample to analysis:

Performance Validation and Benchmarking

Establishing Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity

Robust validation is critical for deploying a targeted RNA-Seq assay in a research setting. Performance is measured using well-characterized reference standards and clinical samples.

Table 2: Representative Performance Metrics from Validation Studies

| Validation Parameter | Representative Data | Experimental Details |

|---|---|---|

| Limit of Detection (LOD) - DNA | Mutational abundance down to 5% [11]. | Serial dilution experiments with fusion-spiked reference standards. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) - RNA | 250–400 copies/100 ng input RNA [11]. | Serial dilution of RNA from positive cell lines (e.g., H2228 for EML4-ALK). |

| Sensitivity | 100% (28/28 known positive clinical samples) [11]. | Comparison of assay results against known fusion status from previous tests (NGS or FISH). |

| Specificity | 96.9%-100% (after resolving false negatives) [11] [27]. | Testing of fusion-negative samples and confirmation of discordant results by orthogonal methods (e.g., Sanger sequencing). |

| Reproducibility | 100% concordance in intra-run and inter-run replicates [11]. | Testing of multiple replicates (n=3) within a single run and across different sequencing runs. |

Comparative Performance of Bioinformatics Tools

The choice of fusion-calling algorithm significantly impacts results. One study on 190 FFPE samples found that while the ArcherDX Analysis Suite (ADx) demonstrated high sensitivity, the open-source tools Arriba (ARR) and STAR-Fusion (SFU) showed lower sensitivity but could provide valuable orthogonal support, especially for low-quality data [26]. Combining multiple callers can therefore improve the robustness of fusion detection.

Integrated DNA and RNA Sequencing for Comprehensive Profiling

While RNA-Seq directly captures expressed fusion transcripts, DNA-based NGS can identify genomic rearrangements that may not be transcribed or may be difficult to capture due to RNA degradation. An integrated approach that simultaneously uses DNA and RNA-based NGS maximizes detection sensitivity [11]. Studies have shown that DNA and RNA results can complement each other, with some fusions being detected only at one level [11]. For instance, DNA-based assays may miss fusions due to large intronic regions or complex rearrangements, while RNA-based assays may miss fusions if the transcript is expressed at very low levels or is unstable.

The following diagram conceptualizes this complementary relationship:

Targeted RNA-Seq represents a highly sensitive, specific, and cost-effective methodology for the detection of clinically relevant gene fusions in cancer research. Its design, optimized for challenging, real-world samples like FFPE tissue, makes it particularly suited for both retrospective and prospective studies. Success hinges on several key factors: prudent panel design encompassing actionable genes, a robust laboratory workflow validated for degraded RNA, and a bioinformatics pipeline that leverages complementary algorithms to minimize false positives and negatives. As the landscape of therapeutic targets continues to expand, the implementation of rigorously designed and validated targeted RNA-Seq panels will be indispensable for unraveling the molecular drivers of cancer and advancing drug development.

In precision oncology, DNA sequencing reveals the genetic blueprint of a tumor, but it cannot determine which mutations are actively transcribed into messenger RNA and are therefore more likely to produce functional proteins that drive cancer progression. This fundamental limitation creates a "DNA-to-protein divide" in clinical diagnostics [31]. RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) bridges this critical gap by providing a snapshot of the actively expressed mutational landscape, enabling more accurate cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic targeting [32] [31]. This Application Note details experimental and bioinformatic protocols for using RNA-Seq to identify expressed mutations, with emphasis on clinically-actionable gene fusions in cancer research.

Performance Characteristics of RNA-Seq for Mutation Detection

RNA-Seq demonstrates high sensitivity and specificity for detecting expressed mutations, particularly gene fusions. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of RNA-Seq Assays for Gene Fusion Detection

| Metric | Performance Value | Experimental Context | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 98.4% (62/63 known fusions) | Whole Transcriptome Sequencing (WTS) assay on clinical samples | [24] |

| Specificity | 100% (0 false positives in 21 negative samples) | Same WTS assay on fusion-negative samples | [24] |

| Precision (Average) | 58.6% | GFvoter performance across multiple datasets | [9] |

| Advantage over DNA-Seq | Identifies 18% additional somatic SNVs in lung cancer | Comparative analysis of paired RNA-seq and DNA-seq data | [31] |

These performance characteristics make RNA-Seq particularly valuable for clinical applications where detecting expressed mutations directly influences treatment decisions. For instance, one study found that nearly one-fifth of somatic single nucleotide variants (SNVs) detected by DNA sequencing were not transcribed, suggesting they may have limited clinical relevance for targeted therapies [31].

Experimental Protocol: RNA-Seq for Fusion Detection in Cancer Research

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful RNA-Seq analysis. The following protocol outlines key steps for processing cancer specimens:

- RNA Extraction: Use RNeasy FFPE Kit (Qiagen) or similar for formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples. For optimal results, use tissue stored at 4°C for less than one year with tumor content exceeding 20% [24].

- RNA Quality Assessment: Evaluate RNA integrity using multiple methods:

- Quantification with NanoDrop 8000 and Qubit 3.0

- Quality assessment with Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer system

- Determine DV200 value (percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides). A DV200 ≥30% indicates sufficient RNA quality for sequencing [24].

- Library Preparation:

- Remove ribosomal RNA using NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit

- For samples with DV200 ≤50%, skip fragmentation step

- Perform cDNA synthesis and library preparation using NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit

- Use unique dual indices to enable sample multiplexing [24]

Sequencing Parameters

- Platform: Illumina NextSeq 500 or similar high-throughput platform

- Read Configuration: 75-cycle single-end or 100bp paired-end

- Recommended Depth: Minimum 80 million mapped reads per sample

- Output: Approximately 25 gigabases of data per sample [33] [24]

Bioinformatic Analysis Workflow

The computational analysis of RNA-Seq data involves multiple steps to identify expressed mutations accurately:

- Alignment and Preprocessing:

- Align reads to reference genome using spliced aligners (STAR, GSNAP, or TopHat2)

- Generate raw count tables using tools like HTSeq [33]

- Fusion Detection:

- Apply multiple fusion callers (e.g., GFvoter, LongGF, JAFFAL) to improve accuracy

- GFvoter employs a multivoting strategy using Minimap2, Winnowmap2, and dedicated fusion detection tools [9]

- Differential Expression Analysis:

Diagram: RNA-Seq Fusion Detection Workflow

Applications in Cancer Research and Precision Oncology

RNA-Seq provides critical functional validation of DNA-identified mutations, with several key applications in oncology:

Therapeutic Target Prioritization: RNA-Seq confirms whether mutations identified by DNA sequencing are actually expressed, helping prioritize targets with clinical relevance. Studies show RNA-Seq uniquely identifies variants with significant pathological relevance that were missed by DNA-Seq alone [31].

Gene Fusion Detection: Gene fusions are important drivers of cancer and serve as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. RNA-Seq enables unbiased detection of both known and novel fusion events within any expressed gene [9] [24].

Comprehensive Mutation Profiling: Beyond fusions, RNA-Seq detects alternative splicing events, exon skipping variants (e.g., MET exon 14 skipping in NSCLC), and expressed single nucleotide variants that may impact protein function [24].

Biomarker Discovery: Expression patterns from RNA-Seq can classify cancer subtypes, predict treatment response, and identify resistance mechanisms, contributing to more personalized treatment approaches [32].

Table 2: Clinically-Actionable Mutations Detectable by RNA-Seq

| Mutation Type | Cancer Examples | Clinical Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gene Fusions (ALK, ROS1, RET, NTRK) | Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) | FDA-approved targeted therapies available | [24] |

| Exon Skipping (MET exon 14) | Lung adenocarcinoma, lung sarcomatoid carcinoma | Emerging therapeutic target; responds to MET inhibitors | [24] |

| Expressed SNVs | Various solid tumors | Indicates clinically relevant mutations; 18% of DNA-level SNVs not transcribed | [31] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for RNA-Seq Mutation Detection

| Category | Specific Product/Tool | Application/Function | |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction | RNeasy FFPE Kit (Qiagen) | RNA isolation from FFPE tissue samples | [24] |

| Library Prep | NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit | cDNA synthesis and library construction | [24] |

| rRNA Depletion | NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit | Remove ribosomal RNA to enrich coding transcripts | [24] |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, PacBio SMRT, Oxford Nanopore | High-throughput sequencing; long-read technologies ideal for isoform detection | [35] [36] |

| Alignment Tools | STAR, GSNAP, TopHat2, Minimap2 | "Splicing-aware" alignment of RNA-Seq reads | [33] [9] |

| Fusion Detection | GFvoter, LongGF, JAFFAL, FusionSeeker | Specialized algorithms for identifying fusion transcripts | [9] |

| Differential Expression | edgeR, limma, DESeq2 | Statistical analysis of gene expression changes | [34] |

Pathway Analysis: From DNA Mutation to Expressed Protein

Diagram: Bridging the DNA-to-Protein Divide with RNA-Seq

RNA sequencing provides a critical functional bridge between DNA-level mutations and their protein products, enabling more accurate cancer diagnostics and therapeutic decision-making. By confirming which mutations are actively expressed, RNA-Seq addresses fundamental limitations of DNA-only approaches in precision oncology. The experimental and computational protocols detailed in this Application Note provide researchers with robust methods for detecting expressed mutations, particularly gene fusions, across various cancer types. As sequencing technologies and bioinformatic tools continue to advance, RNA-Seq is poised to play an increasingly central role in cancer research and clinical oncology, ultimately improving patient outcomes through more precise molecular profiling.

An Integrated DNA and RNA NGS Assay for Comprehensive Fusion Detection

Oncogenic gene fusions are hybrid genes resulting from chromosomal rearrangements such as translocations, inversions, deletions, or tandem duplications [1]. These fusions act as powerful drivers in numerous cancers, with products often constituting constitutively active tyrosine kinases or overexpressed transcription factors that lead to uncontrolled cell growth and proliferation [1]. The reliable detection of these fusions is critical for personalized cancer therapy, especially with the advent of targeted treatments like TRK inhibitors for NTRK fusions and selective RET inhibitors for RET fusions, which can produce profound responses in patients whose cancers harbor these alterations [37] [1].

While traditional methods like fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) have proven utility, they possess inherent limitations in identifying novel and noncanonical fusion genes [38]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have therefore become the cornerstone of modern molecular diagnostics. DNA-based NGS (DNA-seq) is adept at identifying genomic breakpoints but can miss fusions involving large introns or complex rearrangements [38]. RNA-based NGS (RNA-seq) directly captures expressed fusion transcripts, offering enhanced sensitivity and the ability to detect unknown partners, but its effectiveness depends on RNA quality and expression levels [37] [38]. An integrated DNA and RNA sequencing approach overcomes the limitations of either method alone, ensuring comprehensive detection of both known and novel oncogenic fusions for optimal therapeutic decision-making.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Integrated Assay Workflow

The following diagram outlines the comprehensive workflow for integrated DNA and RNA sequencing, from sample preparation to final analysis.

Pre-Analytical Considerations and Sample Preparation

The pre-analytical phase is critical for assay success, particularly for labile RNA.

- Tissue Selection and Enrichment: A board-certified pathologist must review hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections to select tumor-rich areas. Macrodissection is preferred over coring to maintain FFPE block integrity, especially for small tumors [37]. A post-dissection H&E slide should be assessed to confirm the target tissue was obtained.

- Nucleic Acid Co-Extraction: DNA and RNA are co-extracted from the same tumor sample. For challenging specimens with low input, testing can proceed at the validated lower limit of the assay, with complementary testing (e.g., IHC) or report caveats considered for negative results [37].

- Quality Control and Input: DNA and RNA quantity and quality are assessed using systems like Nanodrop 2000 and Qubit fluorometer [38]. For RNA-based NGS, input typically ranges from 10–30 ng, reflecting common use of amplicon methods [37]. International standards should guide RNA extraction from FFPE tissue to manage pre-analytic variability [37].

DNA Sequencing (DNA-seq) for Fusion Detection

DNA-seq identifies genomic rearrangements at the DNA level.

- Library Preparation and Target Enrichment: Genomic DNA from FFPE samples is used to prepare NGS libraries with a comprehensive gene panel, such as a 425-gene panel, using kits like the KAPA Hyper Prep kit [38].

- Sequencing and Data Processing: Libraries are sequenced on platforms like the Illumina HiSeq 4000. Sequence reads in FASTQ format undergo quality control with tools like Trimmomatic. High-quality reads are aligned to the human genome (e.g., hg19) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA-MEM) algorithm [38].

- Variant and Fusion Calling: The Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) is used for local realignment and base quality score recalibration. Somatic gene fusion variants are called by tools like Delly with default parameters [38].

RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq) for Fusion Detection

RNA-seq directly identifies expressed fusion transcripts, overcoming limitations of DNA-seq.

- Library Preparation from RNA: Starting with total RNA or RNA enriched for mRNA, cDNA libraries are prepared using kits such as the NEBNext Ultra DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina [33]. The quality of input RNA is paramount; an RNA integrity number (RIN) >7.0 is ideal [33].

- Sequencing and Analysis Workflow: Libraries are sequenced, and the resulting reads are demultiplexed. FASTQ files are aligned to a reference genome (e.g., mm10 for mouse, GRCh37/hg19 for human) using aligners like TopHat2 [33]. Reads are then mapped to genes using tools like HTSeq to generate a raw counts table [33].

- Fusion Transcript Identification: Both whole-transcriptome sequencing (WTS) and more focused targeted RNA-seq panels can be employed. Targeted panels often demonstrate enhanced sensitivity for detecting low-abundance or actionable fusions that may be missed by WTS [38].

Bioinformatic Analysis and Data Integration

- Data Normalization and Processing: RNA-seq count data requires normalization to remove technical biases and enable comparisons across samples. Multiple normalization approaches exist and should be selected based on the experimental design [29].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Tools for differential expression analysis, such as edgeR, employ a negative binomial generalized log-linear model to identify statistically significant changes in gene expression between conditions [33].

- Integrated Caller and Validation: Fusion calls from DNA-seq and RNA-seq are integrated, with discrepancies resolved by orthogonal methods like FISH. This combined approach significantly enhances detection sensitivity and specificity.

Performance and Validation Data

Concordance Between Methodologies

A systematic comparison of DNA-seq, RNA-seq, and FISH for detecting RET fusions in early-stage NSCLC demonstrates the strengths of an integrated approach [38].

Table 1: Concordance Rates Between Detection Methods for RET Fusions

| Comparison | Concordance Rate | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|

| DNA-seq vs. RNA-seq | 92.3% (36/39 cases) | High concordance, but some fusions missed by each method individually. |

| RNA-seq vs. FISH | 84.6% (33/39 cases) | Targeted RNA-seq identified 5 additional RET+ cases missed by WTS. |

| DNA-seq vs. FISH | 82.5% (33/40 cases) | FISH provides visual confirmation but may miss non-canonical fusions. |

Detection Rates of RNA-seq Modalities

The same study highlighted critical performance differences between RNA-seq approaches [38].

Table 2: Detection Performance of RNA-seq Methods

| Method | Detection Rate | Sensitivity | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|