Retrospective Validation of Pharmacophore Virtual Screening: Protocols, Performance, and Best Practices for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of retrospective validation strategies for pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) protocols, a critical step in ensuring their reliability for drug discovery.

Retrospective Validation of Pharmacophore Virtual Screening: Protocols, Performance, and Best Practices for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of retrospective validation strategies for pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) protocols, a critical step in ensuring their reliability for drug discovery. Aimed at researchers and development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of pharmacophore modeling, details the construction and application of robust validation workflows, and addresses common challenges with modern optimization techniques. A core focus is the comparative evaluation of PBVS performance against other virtual screening methods, particularly molecular docking, using established metrics like enrichment factors and ROC-AUC analysis. By synthesizing insights from recent case studies and benchmarks, this review serves as a practical guide for validating and optimizing pharmacophore models to improve hit rates and accelerate lead identification.

Pharmacophore Foundations: Core Concepts and Theoretical Basis for Effective Validation

In the field of computer-aided drug design, the pharmacophore concept serves as a fundamental pillar, providing an abstract framework for understanding molecular recognition between a ligand and its biological target. According to the official definition by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a pharmacophore is "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [1]. This definition emphasizes that a pharmacophore is not a real molecule or a specific association of functional groups, but rather an abstract concept that captures the essential molecular interaction capacities of a group of compounds toward their target structure [2]. In practical terms, it represents the key molecular features and their spatial arrangement that enable a compound to bind to a specific biological target and elicit a biological effect, forming the basis for rational drug design strategies including virtual screening, de novo design, and lead optimization [3] [4].

This guide explores the evolution of the pharmacophore concept from its historical origins to its current IUPAC definition, with a specific focus on objectively comparing different pharmacophore modeling approaches and providing experimental validation data to assist researchers in selecting appropriate methodologies for their drug discovery projects.

Historical Evolution of the Pharmacophore Concept

Early Conceptual Foundations

The origins of the pharmacophore concept trace back to the late 19th century, long before the term itself was formally introduced. Contrary to common attribution in medicinal chemistry literature, recent historical research indicates that Paul Ehrlich did not actually use the term "pharmacophore" in his writings, though he did originate the fundamental concept in his 1898 paper which identified peripheral chemical groups in molecules responsible for binding that leads to biological effects [5]. Ehrlich instead referred to these features as "toxophores," while his contemporaries used the term "pharmacophore" for the same molecular features [5].

The modern conceptual framework was significantly advanced by F. W. Schueler in the 1960s, who used the expression "pharmacophoric moiety" that corresponds to our current understanding [4]. Schueler redefined the concept to focus on spatial patterns of abstract features of a molecule that are ultimately responsible for biological effect, forming the basis for IUPAC's modern definition [5]. The term was subsequently popularized by Lemont Kier in a series of publications between 1967-1971, where he applied the concept to molecular orbital calculations and drug research [4] [6].

The transition from defining pharmacophores as specific chemical groups to patterns of "abstract features" represents a critical evolution in the concept. Early uses referred to specific chemical functionalities like guanidines or sulphonamides, or typical structural skeletons such as flavones or phenothiazines [2]. The modern IUPAC definition deliberately discards this usage in favor of an abstract description of molecular features necessary for molecular recognition [4] [2].

This shift enabled researchers to identify common interaction patterns across structurally diverse molecules, facilitating scaffold hopping and the discovery of novel chemotypes with similar biological activity [7]. The current definition emphasizes that a pharmacophore represents the "largest common denominator" shared by a set of active molecules, focusing on steric and electronic features rather than specific chemical moieties [2].

Methodological Approaches to Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

The structure-based approach to pharmacophore modeling relies on the three-dimensional structure of a macromolecular target, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or computational modeling techniques such as homology modeling or AlphaFold2 [3]. The methodology involves a systematic workflow:

- Protein Preparation: Critical evaluation and preparation of the target structure, including assessment of protonation states, addition of hydrogen atoms (absent in X-ray structures), and evaluation of general quality and biochemical sense [3].

- Ligand-Binding Site Detection: Identification of the key binding site through analysis of experimental data or using bioinformatics tools such as GRID or LUDI that inspect protein surfaces for potential ligand-binding sites based on various properties [3].

- Feature Generation and Selection: Derivation of a map of interactions and construction of pharmacophore hypotheses describing the type and spatial arrangement of chemical features required for ligand binding [3].

When a protein-ligand complex structure is available, the process allows for more accurate pharmacophore generation, as the 3D information of the ligand in its bioactive conformation directly guides the identification and spatial disposition of pharmacophore features [3]. The presence of the receptor also enables incorporation of spatial restrictions through exclusion volumes (XVOL), representing forbidden areas that correspond to the shape of the binding pocket [3].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

In the absence of structural information for the biological target, ligand-based approaches provide an alternative methodology for pharmacophore model development. This approach utilizes the physicochemical properties and structural features of known active ligands to develop 3D pharmacophore models, often incorporating quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) or quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) modeling [3].

The standard workflow involves:

- Training Set Selection: Choosing a structurally diverse set of molecules with known biological activities, including both active and inactive compounds [4].

- Conformational Analysis: Generating a set of low-energy conformations for each molecule that likely contains the bioactive conformation [4].

- Molecular Superimposition: Fitting all combinations of low-energy conformations of the molecules to identify common structural features and their spatial arrangements [4].

- Abstraction: Transforming the superimposed molecules into an abstract representation of key pharmacophore features [4].

- Validation: Testing the pharmacophore model's ability to account for differences in biological activity across a range of molecules [4].

This approach is particularly valuable when structural data for the target protein is unavailable, as it relies solely on information from known active compounds to infer the essential features required for biological activity [3].

Emerging Quantitative Methods

Recent advancements have introduced quantitative pharmacophore activity relationship (QPHAR) methods that extend traditional pharmacophore modeling beyond qualitative virtual screening to predictive quantitative models [7]. Unlike standard QSAR approaches that use molecular descriptors, QPHAR operates directly on pharmacophore representations, offering advantages including reduced bias toward overrepresented functional groups and improved generalization to underrepresented molecular features [7].

The QPHAR algorithm generates a consensus pharmacophore (merged-pharmacophore) from all training samples, aligns input pharmacophores to this merged model, and uses machine learning to derive quantitative relationships between pharmacophore features and biological activities [7]. This approach has demonstrated robustness even with small dataset sizes (15-20 training samples), making it particularly valuable for lead optimization stages in drug discovery projects [7].

Comparative Analysis of Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

Methodological Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

| Aspect | Structure-Based Approach | Ligand-Based Approach | Complex-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Requirements | 3D structure of target protein (from PDB or homology modeling) [3] | Set of known active ligands (with or without inactive compounds) [3] [2] | 3D structure of protein-ligand complex [2] |

| Key Advantages | Can identify novel binding features independent of known ligands; incorporates exclusion volumes [3] | Applicable when protein structure unknown; captures essential features from diverse active compounds [3] [4] | Highest accuracy by directly using bioactive ligand conformation; includes spatial restrictions [3] [2] |

| Limitations | Quality dependent on input structure accuracy; may generate excessive features requiring manual refinement [3] | Limited by diversity and quality of known ligands; may miss key target-specific features [3] | Limited by availability of complex structures; may be biased toward specific chemotypes [2] |

| Best Applications | Novel target identification; scaffold hopping; when high-quality structures available [3] | Lead optimization; target fishing; when abundant ligand activity data available [3] [2] | High-accuracy screening; understanding specific binding interactions [2] |

Performance Metrics in Retrospective Validation Studies

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Pharmacophore Modeling in Virtual Screening

| Study Context | Methodology | Key Performance Metrics | Comparative Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| EGFR Inhibitor Discovery [8] | Structure-based pharmacophore (Ligand Scout) with molecular docking | Binding affinity (-9.2 to -9.9 kcal/mol); toxicity profile; in vitro cell death (80% at 75-100μM) | Identified compounds with superior binding affinity vs. gefitinib (-9.9 kcal/mol vs. reference); lower toxicity profile [8] |

| W. chondrophila Inhibitor Identification [9] | Multi-target virtual screening with molecular dynamics | 100ns simulation stability; MMGBSA binding free energies; druggability parameters | Identified novel phytocompounds with strong binding affinity and stability at target sites [9] |

| QPHAR Validation [7] | Quantitative pharmacophore modeling across 250+ datasets | RMSE (0.62 ± 0.18); performance with small datasets (15-20 samples) | Robust predictive performance even with small training sets; enables scaffold hopping in QSAR [7] |

Experimental Protocols for Pharmacophore Validation

Retrospective Virtual Screening Protocol

A comprehensive protocol for validating pharmacophore models through retrospective virtual screening involves these critical steps:

- Dataset Curation: Compile active compounds (known binders) and decoy molecules (presumed inactives) to create a benchmark dataset. The directory of useful decoys (DUD) or similar resources provide standardized sets for fair comparison [8] [7].

- Pharmacophore Model Generation: Develop models using structure-based, ligand-based, or complex-based approaches as previously described [3] [2].

- Database Screening: Employ the pharmacophore model as a search query against the benchmark database using software such as Catalyst, LigandScout, or MOE [3] [4] [8].

- Performance Evaluation: Calculate enrichment metrics including:

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Measures the concentration of active compounds in the hit list compared to random selection

- Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC): Assesses the model's ability to distinguish active from inactive compounds

- Hit Rate: Percentage of active compounds retrieved in the top ranked molecules [8] [7]

- Comparative Analysis: Compare pharmacophore performance against other virtual screening methods such as molecular docking or 2D similarity searching [8].

Integrated Pharmacophore-Docking Workflow

Combining pharmacophore modeling with molecular docking creates a powerful hierarchical screening protocol:

- Initial Pharmacophore Filtering: Apply pharmacophore models to rapidly screen large compound libraries and reduce the dataset size [9] [8].

- Molecular Docking: Subject pharmacophore-matched compounds to more computationally intensive docking studies using programs like MOE, AutoDock, or Glide [9] [8].

- Binding Pose Analysis: Examine the geometric and chemical complementarity of high-ranking docking poses [9].

- Consensus Scoring: Rank compounds based on complementary information from both pharmacophore matching and docking scores [9] [8].

- Experimental Validation: Select top-ranked compounds for in vitro testing to confirm biological activity [8].

This integrated approach leverages the strengths of both techniques: the rapid filtering capability of pharmacophore screening and the more detailed binding assessment of molecular docking [9] [8].

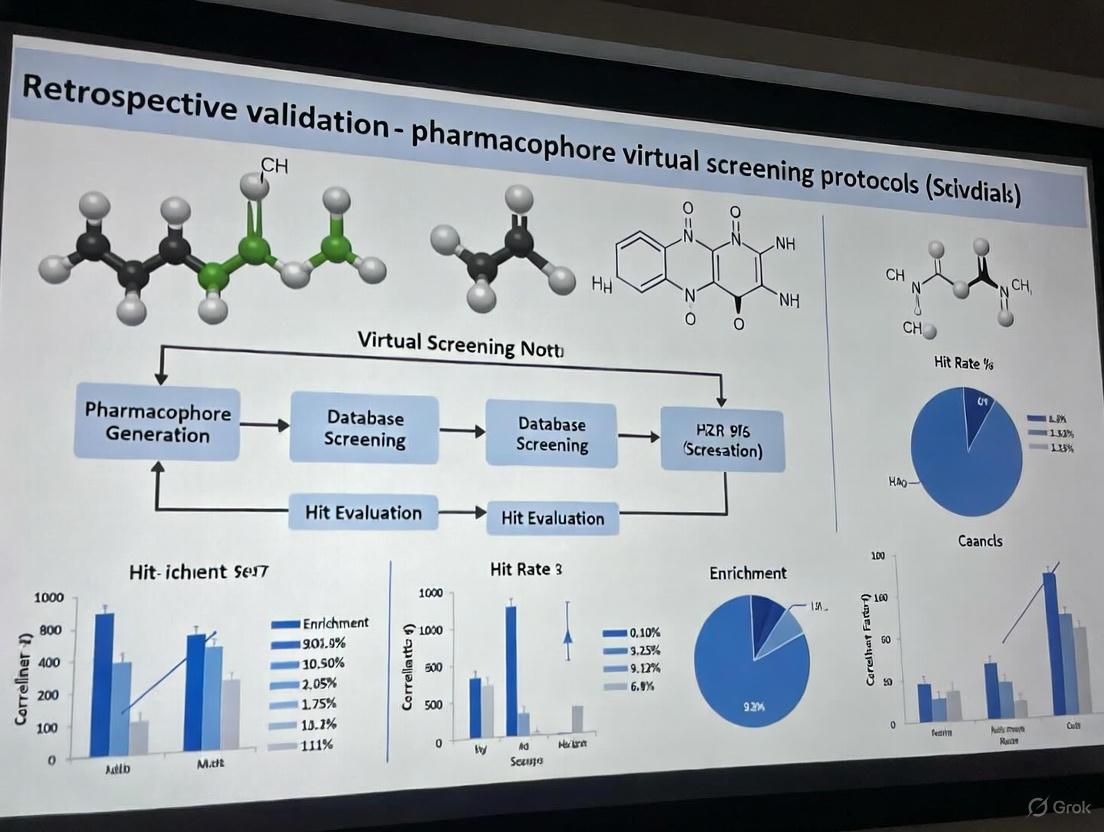

Figure 1: Workflow for pharmacophore model validation through retrospective virtual screening.

Molecular Dynamics Validation Protocol

To assess the stability of pharmacophore-predicted binding modes, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide valuable insights:

- System Preparation: Embed the protein-ligand complex in a solvated box with appropriate ions to neutralize the system [9].

- Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent and conjugate gradient minimization to remove steric clashes [9].

- Equilibration: Gradually heat the system to physiological temperature (310K) and stabilize pressure [9].

- Production Run: Conduct extended MD simulation (typically 100ns or longer) using packages like GROMACS, AMBER, or NAMD [9].

- Trajectory Analysis: Calculate:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures structural stability

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Assesses residual flexibility

- Ligand-protein contacts: Monitors persistence of key interactions [9]

- Binding Free Energy Calculations: Employ MM-GB/PBSA methods to compute theoretical binding affinities [9].

This protocol was effectively implemented in a study against Waddlia chondrophila, where 100ns MD simulations complemented docking results and demonstrated strong stability of predicted compounds at the docked site [9].

Table 3: Key Research Resources for Pharmacophore Modeling and Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Software | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | LigandScout [3] [8], Catalyst/Discovery Studio [3] [2], MOE [9], Phase [7] | Create structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore models; perform virtual screening | Primary model generation and screening workflows |

| Protein Structure Databases | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [3], AlphaFold Protein Structure Database [3] | Source experimental and predicted protein structures | Structure-based pharmacophore modeling |

| Compound Libraries | PubChem [9], MPD3 [9], ZINC [9], ChEMBL [7] | Provide compounds for virtual screening and benchmark datasets | Virtual screening campaigns; model validation |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD [9] | Perform MD simulations to validate binding stability | Assessment of binding pose stability and interactions |

| Docking Programs | MOE [9], AutoDock, Glide [8] | Molecular docking studies | Integrated pharmacophore-docking workflows |

| Validation Metrics | Enrichment Factor (EF), ROC curves, RMSE [7] | Quantitative assessment of model performance | Retrospective validation studies |

Figure 2: Integrated drug discovery workflow combining pharmacophore modeling with complementary computational and experimental approaches.

The evolution of the pharmacophore concept from Ehrlich's early ideas of "toxophores" to the modern IUPAC definition reflects significant theoretical and methodological advances in drug discovery. Today, pharmacophore modeling represents a sophisticated approach that integrates multiple computational techniques to identify and optimize therapeutic compounds. As demonstrated through comparative validation studies, structure-based, ligand-based, and complex-based approaches each offer distinct advantages depending on available data and project goals. The emergence of quantitative pharmacophore methods (QPHAR) and robust integration with molecular docking and dynamics simulations has further strengthened the reliability of pharmacophore-based virtual screening. For researchers embarking on pharmacophore studies, the experimental protocols and resource toolkit provided here offer a practical foundation for implementing and validating these methodologies in future drug discovery campaigns.

In the context of retrospective validation of pharmacophore virtual screening protocols, understanding the core structural components of a pharmacophore model is fundamental. A pharmacophore is formally defined as "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [10]. This abstract representation of key functional elements serves as a template for identifying novel bioactive compounds through virtual screening. The accuracy and predictive power of any pharmacophore-based screening protocol directly depend on the precise definition and spatial arrangement of its core components, making their understanding critical for researchers developing and validating these computational methods.

The retrospective validation of pharmacophore models relies heavily on examining how well these core components recapitulate known bioactive conformations and distinguish active from inactive compounds in benchmark datasets. As pharmacophore modeling evolves with artificial intelligence and deep learning approaches [11] [12], the fundamental features—hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic features, and exclusion volumes—remain the essential building blocks upon which these advanced methods operate. This article examines these key components through the lens of experimental validation studies, providing a comparative analysis of their roles in successful screening protocols across various therapeutic targets.

Core Pharmacophore Components: Definitions and Spatial Characteristics

Hydrogen Bond Donors and Acceptors

Hydrogen bond donors (HBD) and hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) are polar features that define a molecule's capacity to form specific directional interactions with biological targets. HBD features are typically associated with hydrogen atoms attached to electronegative atoms (such as O-H or N-H groups), while HBA features correspond to electronegative atoms (such as O, N, or S) that can accept hydrogen bonds [10] [13]. These features are crucial for establishing complementary interactions with amino acid residues in protein binding pockets, particularly those capable of forming hydrogen bonds, such as serine, threonine, asparagine, glutamine, and charged residues.

In practice, HBD and HBA features are represented as vector-based entities in pharmacophore models, with defined directions that optimize alignment with corresponding features in the target protein. For example, in a structure-based pharmacophore model developed for XIAP protein inhibitors, researchers identified three HBA and five HBD features that were critical for binding to residues THR308, ASP309, and GLU314 [13]. The spatial directionality of these features ensured proper orientation of potential inhibitors within the binding pocket. Similarly, in a pharmacophore model for Akt2 inhibitors, two hydrogen bond acceptor features and one donor feature were positioned to interact with key amino acids Ala232, Phe294, and Asp293 [14].

Hydrophobic Features

Hydrophobic features represent non-polar regions of a molecule that participate in van der Waals interactions and favor contact with other non-polar surfaces. These features are typically associated with aliphatic carbon chains, aromatic rings, or other non-polar molecular regions [10] [14]. In pharmacophore modeling, hydrophobic features are represented as points in three-dimensional space that indicate optimal positions for these non-polar interactions, which often contribute significantly to the binding energy through the hydrophobic effect.

The strategic placement of hydrophobic features can guide the alignment of inhibitors within specific sub-pockets of a protein target. For instance, in the Akt2 pharmacophore model, four hydrophobic features were positioned to interact with distinct hydrophobic pockets composed of residues Phe439, Met282, Ala178, Gly159, Val166, Gly164, Gly161, Met229, Lys181, Phe294, Phe163, and Lys181 [14]. This multi-point hydrophobic interaction pattern ensured complementarity with the complex topology of the Akt2 binding site. The geometric arrangement of these hydrophobic centers often dictates scaffold selection during virtual screening, enabling the identification of structurally diverse compounds with conserved hydrophobic interaction patterns.

Exclusion Volumes

Exclusion volumes (also known as forbidden volumes) represent regions in space that ligands should not occupy due to steric clashes with the target protein [10]. These features are critical for improving the selectivity of pharmacophore models by filtering out compounds that would sterically interfere with protein residues. Exclusion volumes are typically represented as spheres placed on protein atoms that form the binding pocket boundary, creating a negative image of the binding site geometry.

The implementation of exclusion volumes significantly enhances the discriminatory power of pharmacophore screening protocols. In the development of a pharmacophore model for SARS-CoV-2 papain-like protease (PLpro) inhibitors, exclusion volumes were essential for ensuring that identified hits could properly fit within the complex binding site without clashing with protein atoms [15]. Similarly, in the Akt2 inhibitor study, eighteen exclusion volume spheres were incorporated to represent the steric constraints of the binding pocket [14]. Retrospective validation studies have demonstrated that models incorporating carefully defined exclusion volumes achieve significantly higher enrichment factors by reducing false positives that might otherwise match the pharmacophore features but cannot be accommodated sterically within the binding site.

Comparative Analysis of Component Performance in Validation Studies

Table 1: Performance of Pharmacophore Components in Retrospective Validation Studies

| Target Protein | HBD/HBA Features | Hydrophobic Features | Exclusion Volumes | Validation Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XIAP | 5 HBD, 3 HBA | 4 hydrophobic | 15 exclusion volumes | EF1%: 10.0, AUC: 0.98 | [13] |

| Akt2 | 1 HBD, 2 HBA | 4 hydrophobic | 18 exclusion volumes | Successful hit identification | [14] |

| MAO-A/B | Not specified | Not specified | Implemented | 1000x faster than docking | [16] |

| Antibody:Antigen Interfaces | Don/Acc features | Hyd/Aro features | Excluded volume spheres | 98.6% success in complex recapitulation | [10] |

| SARS-CoV-2 PLpro | HBD, HBA | Hydrophobic | Implicit in binding site | Identified novel natural inhibitors | [15] |

Table 2: Experimental Validation Results for Pharmacophore-Generated Hits

| Target | Initial Compound Library | Screening Hits | Experimental IC50/Ki | Validation Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KHK-C | 460,000 compounds from NCI | 10 compounds with superior docking scores | Docking: -7.79 to -9.10 kcal/mol; Binding energy: -57.06 to -70.69 kcal/mol | Multi-level molecular docking, binding free energy estimation, MD simulations | [17] |

| XIAP | ZINC natural product database | 3 stable compounds in MD simulation | Superior to known inhibitors | Molecular dynamics (100 ns simulation) | [13] |

| MAO-A/B | ZINC database with pharmacophore constraints | 24 compounds synthesized | Up to 33% MAO-A inhibition | In vitro enzymatic assay | [16] |

| NK1R (GPCR) | Not specified | 3 active compounds with distinct scaffolds | EC50 ≈ 20 nM after optimization | Experimental concentration-response | [18] |

The comparative analysis of pharmacophore component utilization across multiple studies reveals several important patterns. First, the combination of all three component types consistently yields the highest validation metrics, as demonstrated by the XIAP pharmacophore model that achieved an exceptional enrichment factor (EF1%) of 10.0 and area under the curve (AUC) value of 0.98 in retrospective validation [13]. This model incorporated 5 HBD features, 3 HBA features, 4 hydrophobic features, and 15 exclusion volume spheres, creating a comprehensive representation of the binding site requirements.

Second, the spatial distribution and density of these components significantly impact model performance. Successful models typically feature well-distributed points that map to complementary regions on the target protein. For example, in the antibody-antigen interface pharmacophore study, the specific arrangement of features allowed the method to recapitulate 98.6% of parental antibody-antigen complexes (862 out of 874) and recover all native interfacial contacts in benchmarking studies [10]. This highlights the importance of precise geometric positioning of all component types.

Third, the implementation of exclusion volumes consistently improves model selectivity, though the optimal number varies by target. The Akt2 model utilized 18 exclusion volumes [14], while the XIAP model used 15 [13], in both cases substantially reducing false positive rates without excluding potentially valid scaffold variations. This balance is critical for maintaining adequate chemical space coverage while ensuring target compatibility.

Experimental Protocols for Component Validation

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation

The generation of structure-based pharmacophore models typically begins with the analysis of high-quality protein-ligand complexes. As implemented in molecular operating environment (MOE) software, the process involves using the "Protein Contacts" application to detect ionic, hydrogen bond, arene, and distance contacts at the interface [10]. A specialized Scientific Vector Language (SVL) function ("ph4fromppi.svl") then automatically creates a pharmacophore query based on contacts between atoms. For each detected interaction, corresponding pharmacophore features (HBD, HBA, hydrophobic, etc.) are placed with appropriate positions, directions (for vectors), and tolerance radii. Exclusion volumes are subsequently added by placing Van der Waals spheres on protein atoms surrounding the binding site.

In the DS 2.5 software package (Discovery Studio), the methodology involves generating a sphere within a specified distance (typically 7-10 Å) from a reference inhibitor using the Binding Site tool [14]. The Interaction Generation protocol is then applied to identify pharmacophoric features corresponding to all possible interaction points at the active site. The Edit and Cluster pharmacophores tool helps refine redundant features or those without catalytic importance, retaining only representative features with demonstrated significance. This protocol was successfully applied in developing the Akt2 pharmacophore model containing seven key features [14].

Retrospective Validation Methodology

Comprehensive validation is essential for establishing pharmacophore model reliability. The standard protocol involves decoy set validation using the Database of Useful Decoys (DUD-E), which contains active compounds paired with physicochemically similar but topologically distinct decoys presumed to be inactive [13]. The pharmacophore model is used to screen this combined set, and the enrichment factor (EF) is calculated as:

[EF = \frac{(Number of actives found)/(Total number of compounds found)}{(Total number of actives)/(Total number of compounds in database)}]

Additionally, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve is generated by plotting the true positive rate against the false positive rate at various screening thresholds, with the area under this curve (AUC) providing a robust measure of model discrimination ability [13]. For the XIAP model, this validation yielded an EF1% of 10.0 and AUC of 0.98, demonstrating exceptional discriminatory power [13].

Another critical validation approach assesses the model's ability to recapitulate known bioactive complexes. In the antibody-antigen interaction study, researchers tested whether pharmacophore models generated from 874 Ab:Ag complexes could reproduce the parental complexes, achieving 98.6% success [10]. This large-scale validation across diverse interfaces provides strong evidence for the generalizability of the pharmacophore approach when properly configured with appropriate component definitions.

Virtual Screening Workflow Implementation

The virtual screening workflow typically begins with pharmacophore-based filtering of large compound libraries, followed by multi-level molecular docking, binding free energy estimation, ADMET profiling, and molecular dynamics simulations [17]. For example, in the KHK-C inhibitor screening study, this comprehensive protocol identified ten compounds with docking scores ranging from -7.79 to -9.10 kcal/mol and binding free energies from -57.06 to -70.69 kcal/mol, superior to clinical candidates PF-06835919 and LY-3522348 [17]. Subsequent ADMET profiling refined the selection to five compounds, with molecular dynamics simulations identifying the most stable candidate.

Advanced implementations are increasingly incorporating machine learning acceleration to enhance screening throughput. One recent approach uses machine learning models trained on docking results to predict binding affinities without performing explicit molecular docking for each compound [16]. This method demonstrated a 1000-fold acceleration in virtual screening while maintaining high predictive accuracy, enabling the rapid evaluation of ultra-large chemical libraries while incorporating essential pharmacophore constraints.

Visualization of Pharmacophore Concepts and Workflows

Pharmacophore Model Development and Validation Workflow - This diagram illustrates the comprehensive process for developing validated pharmacophore models, highlighting the integration of core components throughout the workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pharmacophore Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Software Platforms | MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Automated pharmacophore generation from protein complexes | Antibody-antigen pharmacophore modeling [10] |

| Discovery Studio (DS) | Structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling | Akt2 inhibitor pharmacophore generation [14] | |

| LigandScout | Advanced pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening | XIAP inhibitor pharmacophore development [13] | |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC Database | Curated collection of commercially available compounds | Natural product screening for XIAP inhibitors [13] |

| NCI Compound Library | Diverse chemical compounds for screening | KHK-C inhibitor identification [17] | |

| ChEMBL Database | Bioactivity data for model validation | MAO inhibitor screening [16] | |

| Validation Resources | DUD-E (Database of Useful Decoys) | Decoy molecules for model validation | XIAP pharmacophore validation [13] |

| LIT-PCBA Benchmark | Active/inactive compounds for benchmarking | PharmacoForge evaluation [12] | |

| Specialized Tools | RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics and conformer generation | Conformer generation in Alpha-Pharm3D [18] |

| Smina Docking | Molecular docking for binding affinity estimation | MAO inhibitor docking scores [16] | |

| GOLD | Docking program for binding mode analysis | Akt2 inhibitor docking studies [14] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of pharmacophore modeling is rapidly evolving with the integration of artificial intelligence and deep learning approaches. Methods like PharmacoForge utilize diffusion models to generate 3D pharmacophores conditioned on protein pockets, creating queries that can identify valid, commercially available molecules [12]. Similarly, the PGMG (Pharmacophore-Guided deep learning approach for bioactive Molecule Generation) framework uses graph neural networks to encode spatially distributed chemical features and transformers to generate molecules matching given pharmacophores [11]. These approaches maintain the fundamental component definitions while revolutionizing how they are identified and applied.

Another significant advancement is the development of ensemble methods that combine pharmacophore screening with machine learning-based scoring. Alpha-Pharm3D, for example, employs 3D pharmacophore fingerprints with explicit geometric constraints to predict ligand-protein interactions, achieving AUROC values of approximately 90% across diverse datasets [18]. This integration of traditional pharmacophore components with deep learning architectures demonstrates how the fundamental features—HBD/HBA, hydrophobic features, and exclusion volumes—remain relevant even as computational methodologies advance.

The retrospective validation of pharmacophore protocols has consistently demonstrated that proper implementation of these core components delivers exceptional performance across diverse target classes. From antibody-antigen interactions [10] to metabolic enzymes like KHK-C [17] and neurodegenerative disease targets like MAO [16], the strategic application of hydrogen bond features, hydrophobic features, and exclusion volumes continues to enable the identification of novel bioactive compounds with improved efficiency over traditional screening methods. As these components become increasingly embedded in AI-driven workflows, their precise definition and validation remain essential for advancing virtual screening protocols in drug discovery.

Pharmacophore modeling represents a pivotal computational strategy in modern drug discovery, providing an abstract framework to define the essential steric and electronic features responsible for optimal molecular interactions with a specific biological target. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines a pharmacophore as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [19]. These features typically include hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrophobic (H) regions, positive or negative ionizable groups (PosIon, NegIon), and aromatic rings (Ar) [20] [21].

The fundamental premise of pharmacophore modeling stems from the observation that diverse chemical structures can interact with the same molecular target if they share a common pharmacophore model [20]. This understanding enables researchers to identify novel bioactive compounds even when their chemical scaffolds differ significantly from known active molecules. Pharmacophore modeling has been extensively applied in virtual screening, lead compound optimization, and de novo drug design strategies across various therapeutic areas [20] [22].

Two principal computational approaches dominate pharmacophore modeling: structure-based and ligand-based methods. The selection between these approaches depends primarily on the availability of structural information about the target and known active compounds. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their underlying principles, implementation protocols, performance characteristics, and validation within retrospective virtual screening studies.

Methodological Foundations

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling relies on three-dimensional structural information about the target protein, typically obtained through experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) [20] [23]. This approach extracts chemical features directly from the analysis of the binding site and critical interactions between the target and a bound ligand.

The methodology involves analyzing the complementarity between the receptor's binding site and ligand functional groups to identify essential interaction points. These points are subsequently translated into pharmacophore features with specific spatial arrangements [24]. The approach captures the physicochemical and spatial restrictions imposed by the binding site, including the physicochemical properties of amino acid residue composition, cavity volume, and shape [20].

A key advantage of structure-based methods is their ability to identify novel chemotypes without prior knowledge of active compounds, making them particularly valuable for targets with limited ligand information [25]. The spatial information derived from experimentally elucidated structures of molecular targets complexed with an active ligand provides a reliable foundation for model generation [20].

Experimental Protocols for Structure-Based Model Generation:

- Target Preparation: Obtain the three-dimensional structure of the target protein from sources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Select structures with high resolution and relevant bound ligands. Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning correct protonation states, and optimizing hydrogen bonding networks.

- Binding Site Analysis: Identify the binding cavity using computational tools like CASTp or PrankWeb [26]. Define the active site region where ligand interactions occur.

- Interaction Analysis: Analyze interactions between the bound ligand and protein residues using molecular visualization software. Identify key hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, ionic interactions, and other relevant molecular recognition patterns.

- Feature Mapping: Translate identified interactions into pharmacophore features using programs such as LigandScout [19] [21] or MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) [20]. Common features include hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and charged centers.

- Model Validation: Validate the generated pharmacophore model using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis [24] [21]. This involves screening a dataset of known active compounds and decoys to evaluate the model's ability to distinguish true actives. The area under the curve (AUC) and enrichment factors (EF) at early screening stages (e.g., 1%) serve as key validation metrics [21].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling approaches are employed when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unavailable. These methods derive pharmacophore models from a set of known active compounds by identifying common chemical features and their spatial arrangements responsible for biological activity [20] [22].

The fundamental assumption underlying ligand-based approaches is that compounds exhibiting similar biological activities share a common pharmacophore despite potential structural differences [27]. This methodology involves generating multiple conformations of each active ligand, superimposing them to find the optimal alignment, and extracting common chemical features that correlate with biological activity [20].

The quality of ligand-based models heavily depends on the structural diversity and conformational coverage of the training set compounds. A well-curated dataset with representative active molecules from different chemical classes typically yields more robust and selective pharmacophore models [22].

Experimental Protocols for Ligand-Based Model Generation:

- Training Set Selection: Compile a structurally diverse set of known active compounds with comparable biological activities against the target. Include molecules covering a range of potency values to enhance model quality.

- Conformational Analysis: Generate comprehensive conformational ensembles for each training set compound using algorithms that ensure broad coverage of accessible spatial arrangements.

- Molecular Alignment: Perform flexible alignment of training set conformers to identify the optimal spatial overlay that maximizes the commonality of chemical features. This can be achieved through various algorithms including point-based or property-based methods.

- Feature Extraction: Identify conserved chemical features across the aligned molecule set using software such as LigandScout [19], HypoGen [22], or PHASE [21]. The model typically includes features like hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and aromatic rings.

- Model Validation: Validate the model using test set molecules not included in the training phase [22]. Calculate goodness-of-hit (GH) scores [28] and perform ROC analysis to assess the model's ability to discriminate between active and inactive compounds [21].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Retrospective Validation Metrics

Retrospective validation represents a critical step in assessing pharmacophore model performance before prospective screening applications. This process evaluates a model's ability to prioritize known active compounds over inactive molecules in virtual screening experiments [19] [21]. Several quantitative metrics facilitate this comparison:

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Measures the concentration of active compounds in the hit list compared to their random distribution in the screened database. EF values are typically calculated at early screening stages (e.g., 1% of the database) to assess early enrichment capability [21].

- Area Under the Curve (AUC): Derived from ROC analysis, the AUC quantifies the overall ability of a model to distinguish active from inactive compounds. An AUC value of 1.0 represents perfect discrimination, while 0.5 indicates random performance [24] [21].

- Goodness-of-Hit (GH) Score: A composite metric that integrates the recall of actives, precision of the hit list, and the yield of actives. GH scores range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating better model performance [28].

- Hit Rate: The proportion of identified active compounds relative to the total number of screened molecules.

Performance Comparison in Retrospective Studies

Retrospective virtual screening studies provide critical insights into the relative performance of structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore models. The table below summarizes quantitative performance data from published comparative studies:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Structure-Based vs. Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Models

| Study Context | Model Type | Performance Metrics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunoproteasome β1i Inhibition [21] | Structure-Based (LigandScout) | AUC1% = 1.0; EF1% = 15.3 | Excellent early enrichment with perfect AUC |

| Ligand-Based (PHASE) | AUC1% = 0.60; EF1% = 4.9 | Moderate discrimination capability | |

| PD-L1 Inhibition [24] | Structure-Based (6R3K-based) | AUC = 0.819; 12 hits from 52,765 compounds | Good discrimination with practical hit identification |

| Cephalosporin Antibiotics [28] | Ligand-Based (Shared Features) | GH Score = 0.739 | Robust model for identifying novel antibiotic conformers |

| Topoisomerase I Inhibition [22] | Ligand-Based (HypoGen) | 3 confirmed hits from virtual screening | Successful identification of novel inhibitors |

The data reveal that both approaches can successfully identify bioactive compounds, but their performance characteristics differ significantly. Structure-based models frequently demonstrate superior early enrichment capabilities, as evidenced by higher EF and AUC values in direct comparisons [21]. This enhanced performance stems from the incorporation of precise structural information about the target binding site, which enables more accurate definition of essential molecular interactions.

Ligand-based models provide substantial utility despite typically lower enrichment metrics in retrospective studies. Their principal advantage resides in applicability scenarios where structural target information remains unavailable. Furthermore, ligand-based approaches can identify structurally diverse hits that maintain critical pharmacophore features, potentially expanding chemical space exploration [22].

A prospective comparative study evaluating virtual screening methods for cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibitors demonstrated that all methods performed well but showed considerable differences in hit rates, true positive and true negative hits, and hitlist composition [19]. This highlights the context-dependent nature of model performance and suggests that the optimal approach may vary based on specific research objectives and target characteristics.

Integrated Workflows and Advanced Applications

Hybrid Approaches

Recent advancements increasingly leverage hybrid strategies that integrate both structure-based and ligand-based methodologies to overcome the limitations of individual approaches. These integrated workflows enhance model robustness and screening effectiveness by complementing the strengths of each method [25].

A representative example includes combining structure-based pharmacophore modeling with ligand-based virtual screening. In a study investigating mosquito repellents, researchers employed this integrated strategy by using DEET complexed with an odorant-binding protein as a structural template while simultaneously incorporating known active compounds for ligand-based screening [20]. This synergistic approach identified seven natural volatile compounds with potential repellent activity that might have been overlooked using either method independently.

Another emerging trend involves the incorporation of dynamic information through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Advanced implementations generate "dynamic pharmacophore models" that account for protein flexibility and multiple binding modes [21]. For immunoproteasome inhibition studies, researchers developed merged pharmacophore models incorporating features from multiple representative poses derived from MD simulations, resulting in improved virtual screening performance [21].

Artificial Intelligence-Enhanced Pharmacophore Modeling

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and deep generative models represents a cutting-edge advancement in pharmacophore-based drug discovery. These approaches address limitations in conventional methods by leveraging multi-dimensional data and sophisticated sampling algorithms [25].

The CMD-GEN (Coarse-grained and Multi-dimensional Data-driven molecular generation) framework exemplifies this innovation by employing a hierarchical architecture that decomposes three-dimensional molecule generation into pharmacophore point sampling, chemical structure generation, and conformation alignment [25]. This approach bridges ligand-protein complexes with drug-like molecules by utilizing coarse-grained pharmacophore points sampled from diffusion models, effectively enriching training data and enhancing model stability.

In benchmark tests, AI-enhanced approaches like CMD-GEN have demonstrated superior performance in controlling drug-likeness and generating molecules with stable conformations that maintain proximity to the target pocket without undue deviation [25]. Furthermore, these methods show particular promise in specialized design challenges such as generating selective inhibitors or dual-target inhibitors, which present difficulties for conventional pharmacophore modeling approaches.

Experimental Implementation

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of pharmacophore modeling requires specific computational tools and resources. The table below outlines essential research reagents and their applications in pharmacophore-based virtual screening:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Resource Category | Examples | Specific Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial Software | LigandScout [19] [21], MOE [20] | Structure-based & ligand-based model generation | Advanced algorithms for conformational analysis and structural alignment |

| Open-Source Tools | Pharmer [20], Align-it [20] | Ligand-based pharmacophore prediction | Cost-effective alternatives with OS compatibility |

| Web Servers | Pharmit [20] [26], PharmMapper [20] | Structure-based virtual screening | Free-access platforms for compound screening |

| Compound Databases | ZINC [22] [27], CHEMBL [26], Marine Natural Products [24] | Source of screening compounds | Extensive collections of purchasable compounds |

| Protein Data Resources | PDB [24], AlphaFold [26] | Source of target structures | Experimental and predicted protein structures |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the comparative workflows for structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, highlighting key decision points and methodological differences:

Structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling represent complementary approaches with distinct advantages and limitations. Structure-based methods provide superior performance when high-quality target structures are available, offering enhanced enrichment and better discrimination between active and inactive compounds [24] [21]. Conversely, ligand-based approaches offer practical solutions for targets lacking structural information and can successfully identify novel chemotypes through shared feature analysis [28] [22].

The choice between these methodologies depends on multiple factors, including data availability, target characteristics, and research objectives. Structure-based approaches are particularly valuable for novel targets with known structures but limited ligand information, while ligand-based methods excel when substantial structure-activity data exists for diverse chemical scaffolds [20] [23].

Future directions in pharmacophore modeling emphasize integration and intelligence. Hybrid approaches that combine structure-based and ligand-based methodologies with molecular dynamics simulations and machine learning algorithms demonstrate enhanced performance in retrospective validations [25] [21]. These advanced frameworks address limitations associated with single approaches and show particular promise for challenging drug discovery scenarios such as selective inhibitor design and polypharmacology targeting.

Retrospective validation remains essential for establishing model credibility before prospective applications. Standardized metrics including enrichment factors, AUC values, and goodness-of-hit scores enable objective performance comparisons and facilitate method selection for specific research contexts [24] [28] [21]. As artificial intelligence continues transforming drug discovery, pharmacophore modeling evolves correspondingly, maintaining its relevance as a powerful tool for rational drug design.

The retrospective validation of pharmacophore virtual screening protocols relies fundamentally on the quality of the benchmarking datasets used. These datasets, composed of known active compounds and carefully selected decoy molecules, are critical for evaluating the enrichment performance and real-world applicability of virtual screening workflows in computer-aided drug design [29]. The evolution of decoy selection strategies—from simple random compound selection to sophisticated property-matched approaches—has significantly advanced the field by minimizing artificial enrichment biases and providing more realistic assessment frameworks [29].

The Critical Role of Decoys in Virtual Screening Validation

Virtual screening (VS) represents a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, enabling researchers to prospectively identify potential hit compounds capable of interacting with therapeutic targets from large chemical libraries [29]. Both structure-based (SBVS) and ligand-based (LBVS) virtual screening approaches require rigorous retrospective validation using benchmarking datasets before application in real-world discovery campaigns [29] [8]. These benchmarking datasets contain two essential components: confirmed active compounds and decoy molecules.

The composition of both active and decoy compound subsets critically impacts the evaluation of VS methods [29]. Decoys, or putative inactive molecules, serve as challenging distractors that must be discriminated from true actives by effective virtual screening protocols. The careful selection of decoys ensures that observed enrichment reflects genuine pharmacological recognition rather than artificial biases arising from physicochemical property differences [29] [30].

Common metrics for assessing virtual screening performance include Receiver Operating Characteristics (ROC) curves, the Area Under the ROC Curve (ROC AUC), Enrichment Factors (EF), and predictiveness curves [29]. Each of these metrics depends on the model's ability to correctly prioritize active compounds over decoys, highlighting the fundamental importance of well-curated validation sets.

Evolution of Decoy Selection Methodologies

From Random Selection to Physicochemical Matching

The earliest virtual screening benchmarking efforts utilized simple random compound selection from large chemical databases like the Advanced Chemical Directory (ACD) or MDL Drug Data Report (MDDR) [29]. These pioneering approaches, while foundational, introduced significant biases because decoys often differed substantially from active compounds in basic molecular properties, leading to artificial inflation of enrichment metrics [29].

A critical advancement came with the incorporation of physicochemical filters in the early 2000s. Researchers began selecting decoys with similar polarity and molecular weight to known actives, ensuring that discrimination was based on specific structural features relevant to biological activity rather than gross molecular properties [29]. This approach represented a substantial improvement but remained limited by commercial database licensing constraints.

The DUD Database and Property-Matched Decoys

A transformative development occurred in 2006 with the introduction of the Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD) database, which established a new gold standard for decoy selection [29]. DUD introduced the crucial concept of selecting decoys that were physicochemically similar to active compounds (matching molecular weight, logP, and number of rotatable bonds) while remaining structurally dissimilar to reduce the probability of actual biological activity [29].

This property-matched approach ensured that virtual screening methods faced a more challenging discrimination task, requiring recognition of specific pharmacophoric features rather than relying on obvious physicochemical differences. The DUD database contained 2,950 ligands and 95,326 decoys across 40 protein targets, providing a comprehensive validation resource for the research community [29].

Contemporary Decoy Selection Tools and Strategies

Recent years have witnessed further refinement of decoy selection methodologies, with several tools emerging to address specific limitations of earlier approaches:

Table 1: Modern Decoy Generation Tools and Databases

| Tool/Database | Key Features | Advantages | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| LUDe [31] | Open-source decoy generation inspired by DUD-E | Reduced probability of topological similarity to actives; available as web app and Python code | Ligand-based virtual screening validation |

| DUD-E [32] | Enhanced version of original DUD | Property-matched decoys; widely adopted benchmark | General virtual screening validation |

| DUDE-Z [32] | Optimized version of DUD-E | Improved chemical space coverage; demanding test cases | Rigorous benchmarking of docking protocols |

| Dark Chemical Matter (DCM) [30] | Experimentally confirmed non-binders from HTS | High-confidence inactives; minimal false negatives | Machine learning model training |

| PADIF with DIV [30] | Data augmentation using diverse docking conformations | Utilizes same compounds as own decoys via incorrect poses | Interaction fingerprint-based machine learning |

Modern machine learning approaches have further expanded decoy selection strategies. The Protein per Atom Score Contributions Derived Interaction Fingerprint (PADIF) methodology enables the use of diverse conformational states as decoys, where the same active molecules in incorrect binding poses serve as challenging negative examples [30]. Similarly, dark chemical matter (DCM)—compounds that consistently show no activity across numerous high-throughput screens—provides experimentally validated decoys with high confidence in their inactive status [30].

Experimental Protocols for Dataset Validation

Standard Workflow for Benchmarking Dataset Construction

The creation of robust validation datasets follows a systematic workflow that ensures both chemical relevance and statistical rigor:

Figure 1: Workflow for constructing validation datasets with active compounds and property-matched decoys.

The initial step involves compiling confirmed active compounds from reliable experimental sources such as ChEMBL, BindingDB, or peer-reviewed literature [33] [30]. These actives undergo rigorous curation including structure standardization, tautomer normalization, and desalting to ensure chemical consistency [33]. Subsequent filtering based on drug-likeness criteria (e.g., molecular weight ≤ 500 Da, logP ≤ 5) focuses the dataset on chemically relevant space [34].

Decoy selection employs property-matching algorithms to ensure similar distributions of molecular weight, logP, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, and rotatable bonds compared to active compounds [29] [31]. Modern tools like LUDe specifically optimize for reduced structural similarity to actives while maintaining physicochemical similarity, challenging models to recognize subtle pharmacophoric differences rather than obvious structural disparities [31].

Key Validation Metrics and Statistical Measures

Dataset quality assessment employs specific metrics to identify potential biases:

- Doppelganger Score: Identifies decoys that are structurally too similar to known actives, which might represent false negatives [31]

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Measures the ratio of true actives identified in a top fraction compared to random selection

- Area Under ROC Curve (AUC): Quantifies overall discrimination capability across all thresholds

- Normalized Enrichment Factor (NEF): Standardized enrichment metric for comparative analysis [33]

Recent research demonstrates that appropriate decoy selection significantly impacts machine learning model performance. Studies using PADIF fingerprints show that models trained with random selections from ZINC15 and dark chemical matter decoys closely mimic the performance of those trained with confirmed non-binders, achieving balanced accuracy scores exceeding 0.8 for most targets [30].

Research Reagent Solutions for Virtual Screening Validation

Table 2: Essential Resources for Validation Dataset Curation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL, BindingDB, PubChem BioAssay | Source of experimentally confirmed active compounds | Publicly available |

| Compound Databases | ZINC15, CMNPD, DrugBank | Source of decoy molecules and screening compounds | Publicly available |

| Decoy Generation Tools | LUDe, DUD-E generator | Create property-matched decoy sets | LUDe: Web app and Python code [31] |

| Cheminformatics Tools | RDKit, OpenBabel, Schrödinger Suite | Compound standardization and property calculation | Mixed open-source and commercial |

| Validation Metrics Packages | DOE scoring, Doppelganger scoring | Quantify dataset quality and potential biases | Custom implementations |

Specialized compound databases have emerged to support particular screening contexts. The Comprehensive Marine Natural Products Database (CMNPD) provides access to marine-derived compounds with unique structural features [35] [34], while the ZINC15 database offers over 9 million commercially available compounds for decoy selection and virtual screening [36].

Comparative Performance of Decoy Selection Strategies

Recent benchmarking studies provide quantitative comparisons of different decoy selection approaches:

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Decoy Selection Strategies

| Strategy | Balanced Accuracy Range | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed Inactives | 0.75-0.95 | Gold standard validation | Limited availability for many targets |

| Dark Chemical Matter (DCM) | 0.70-0.92 | Experimentally validated non-binders | Restricted to well-screened targets |

| ZINC15 Random Selection | 0.65-0.90 | General purpose screening | Potential for false negatives |

| Data Augmentation (DIV) | 0.60-0.85 | Limited compound availability | Pose-dependent performance variability |

Comparative analyses reveal that models trained with DCM and ZINC15 random selections closely approximate the performance of models using confirmed inactive compounds, making them viable alternatives when extensive experimental data is unavailable [30]. The data augmentation approach (DIV), which uses diverse docking conformations of active compounds as decoys, shows higher performance variability but remains valuable for targets with limited known actives [30].

Notably, the LUDe decoy generation tool demonstrates improved performance compared to DUD-E across 102 pharmacological targets, achieving better DOE scores (indicating reduced artificial enrichment risk) while maintaining similar Doppelganger scores [31]. This suggests that modern decoy selection algorithms continue to refine the balance between molecular similarity and pharmacological distinction.

Implementation in Pharmacophore Virtual Screening

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening represents a particularly demanding application for validation datasets, as it relies on the identification of abstract chemical features rather than explicit structural matches [35] [8]. Successful implementation requires decoys that share physicochemical properties with actives while differing in critical spatial arrangements of pharmacophoric elements.

Case studies demonstrate the effectiveness of properly validated datasets in real-world discovery campaigns. For example, research targeting human aromatase for breast cancer treatment utilized structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore models screened against the Comprehensive Marine Natural Products Database [35]. This approach identified several marine natural products with significant binding affinity and stability, with the top compound (CMPND 27987) achieving a binding energy of -10.1 kcal/mol and favorable MM-GBSA free binding energy of -27.75 kcal/mol [35].

Similarly, virtual screening for EGFR inhibitors using structure-based pharmacophore models identified four compounds with improved binding affinity (-9.9 to -9.2 kcal/mol) compared to the marketed drug gefitinib, along with superior toxicity profiles [8]. These compounds demonstrated significant activity in subsequent in vitro validation, inducing apoptosis in cancer cell lines and inhibiting migration [8]. These successes highlight the critical importance of rigorous dataset validation in enabling effective virtual screening.

The curation of high-quality validation datasets with carefully selected actives and property-matched decoys remains essential for advancing pharmacophore virtual screening methodologies. The evolution from simple random selection to sophisticated algorithms that balance physicochemical similarity with structural dissimilarity has significantly improved the reliability of virtual screening validation.

Future directions include increased integration of experimentally confirmed inactive compounds from sources like dark chemical matter, development of machine learning approaches that leverage complex interaction fingerprints, and expanded consideration of polypharmacology effects in decoy selection. As virtual screening continues to evolve as a cornerstone of drug discovery, the essential foundation of well-validated benchmarking datasets will remain critical to meaningful method evaluation and comparison.

The Critical Role of Retrospective Validation in Mitigating Drug Discovery Risk

In the high-stakes field of drug discovery, retrospective validation has emerged as an indispensable strategy for de-risking computational methods before their prospective application. This process rigorously tests computational protocols using known experimental outcomes, ensuring their predictive power and reliability. For pharmacophore-based virtual screening—a method that identifies potential drug candidates by mapping essential 3D chemical features—comprehensive retrospective validation is the critical gatekeeper between a promising algorithm and a costly experimental failure. This guide compares established and emerging validation methodologies, providing researchers with the data and protocols needed to build confidence in their virtual screening campaigns.

Comparative Analysis of Retrospective Validation Methods

The following table summarizes the core validation methods, their key performance metrics, and illustrative applications from recent literature.

| Validation Method | Key Performance Metrics | Typical Workflow | Reported Application & Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decoy-Based Validation (e.g., DUD-E) [37] [38] | Enrichment Factor (EF), Area Under the Curve (AUC) of ROC, Goodness of Hit (GH) | Generate decoy molecules with similar physicochemical properties but dissimilar 2D topology to active compounds; screen database containing actives and decoys [37]. | A model for Brd4 achieved an AUC of 1.0 and excellent EF, indicating powerful discrimination between active and inactive compounds [38]. |

| Test Set Prediction [37] [39] | Predictive R² (R²pred), Root-Mean-Square Error (rmse) | Split known active compounds into a training set (for model building) and a test set (for validation); predict test set activity [37]. | A calcineurin (CaN) inhibitor model identified a novel compound, PMD0011, with an IC50 of 56.62 μM, validated in vitro [39]. |

| Cost Function Analysis [37] | Total Cost, ΔCost (vs. null hypothesis), Configuration Cost | The algorithm calculates the complexity (weight cost, configuration cost) and fit (error cost) of the pharmacophore hypothesis during its generation [37]. | A robust model typically has a ΔCost > 60 and a configuration cost < 17, indicating the model is not a product of chance correlation [37]. |

| Fisher's Randomization Test [37] | Confidence Level | Randomly shuffle the activity data of the training set compounds and rebuild the model; repeat many times to create a distribution of random models [37]. | The original model's correlation is deemed statistically significant if its cost value is lower than those from all or most (e.g., 95%) of the randomized runs [37]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation assays

Decoy Set Validation using the DUD-E Framework

This protocol assesses a model's ability to enrich true active compounds in a virtual screen.

- Objective: To evaluate the screening power and selectivity of a pharmacophore model.

- Procedure:

- Compile Actives: Gather a set of known active compounds for the target (e.g., 36 antagonists for Brd4 from ChEMBL) [38].

- Generate Decoys: Use the DUD-E database generator to create decoy molecules. Decoys are designed to be physically similar (in molecular weight, logP, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors) but chemically distinct from actives to avoid bias [37].

- Virtual Screening: Screen the combined database of actives and decoys using the pharmacophore model as a query.

- Analysis: Generate a ROC curve by plotting the true positive rate against the false positive rate. Calculate the AUC and the Enrichment Factor (EF) to quantify the model's performance [38].

- Data Interpretation: An AUC of 0.5 suggests random performance, 0.7-0.8 is good, and 0.8-1.0 is excellent. A high EF indicates the model efficiently identifies actives early in the screening process [38].

Test Set Prediction and Experimental Correlation

This protocol validates the model's predictive accuracy for novel compounds.

- Objective: To determine the model's robustness and generalizability beyond its training set.

- Procedure:

- Curate Dataset: Assemble a dataset of compounds with known biological activities (e.g., IC50 or Ki values).

- Data Splitting: Divide the dataset into a training set (for model generation) and an independent test set. Ensure both sets cover a diverse chemical space and activity range [37].

- Activity Prediction: Use the pharmacophore model to predict the biological activities of the test set compounds.

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate the R²pred and rmse between the predicted and observed activities [37].

- Experimental Verification: Select top-ranking virtual hits for in vitro testing (e.g., dose-response assays) to confirm inhibitory activity [39].

- Data Interpretation: An R²pred > 0.5 is generally considered acceptable for a predictive model. Successful experimental confirmation, such as achieving low micromolar IC50, provides the strongest support for the model's utility [37] [39].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and databases critical for conducting rigorous retrospective validation.

| Tool/Resource Name | Function in Validation | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| LigandScout [40] [38] | Creates structure- and ligand-based pharmacophore models and performs virtual screening with advanced algorithms. | Used to generate a joint pharmacophore query for SARS‐CoV‐2 NSP13 and to validate a Brd4 model with decoy sets [40] [38]. |

| DUD-E Database [37] | Provides a benchmark for virtual screening by generating property-matched decoy molecules for known active compounds. | Employed in a decoy set validation to calculate the enrichment factor and generate the ROC curve for a pharmacophore model [37]. |

| ZINC Database [38] | A public repository of commercially available compounds, often used as a source for virtual screening and test set creation. | Used for prospective virtual screening to identify natural compounds as potential Brd4 inhibitors [38]. |

| Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) [39] | A comprehensive software suite for molecular modeling, including pharmacophore modeling, docking, and QSAR. | Utilized to develop a novel pharmacophore model for calcineurin and to screen a database of over 650,000 molecules [39]. |

| AlphaFold2 [41] | Provides highly accurate protein structure predictions for targets without experimental structures, enabling structure-based pharmacophore modeling. | Expands the scope of targets for SBDD; its models can be used for pharmacophore generation, though careful validation of the binding site is recommended [41]. |

Retrospective Validation in Action: Case Studies

Case Study 1: Fragment-Based Discovery for SARS-CoV-2

The FragmentScout workflow was developed to address the bottleneck of evolving millimolar fragment hits into micromolar leads. It aggregates pharmacophore feature information from multiple experimental fragment poses (from XChem crystallographic data) into a single, joint query. In a prospective study against SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 helicase, this retrospectively validated method successfully identified 13 novel micromolar inhibitors, later confirmed in cellular antiviral assays. This demonstrates how validating a novel protocol on known data can lead to a successful prospective application [40].

Case Study 2: Ensuring Specificity for a Challenging Target

Developing specific inhibitors for calcineurin (CaN) is difficult due to its highly conserved active site. Researchers created a pharmacophore model mimicking the interaction of CaN's auto-inhibitory domain. Retrospective validation and subsequent virtual screening identified a novel scaffold (PMD0011). Crucially, experimental validation showed that PMD0011 inhibited CaN with low micromolar potency without affecting the related phosphatase PP2A, demonstrating the model's success in enabling target specificity [39].

Visualizing the Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision points in a comprehensive retrospective validation protocol for a pharmacophore model.

Retrospective validation is the cornerstone of reliable pharmacophore-based virtual screening. As the field evolves, machine learning and AI are being integrated to further refine and predict the performance of pharmacophore models. For instance, "cluster-then-predict" workflows using logistic regression can now identify high-enrichment pharmacophore models for targets with no known ligands [42]. Furthermore, new generative AI models like PharmacoForge can create pharmacophores conditioned on protein pockets, offering a promising, validated path to identify potent and synthetically accessible leads [12]. By rigorously applying the comparative frameworks and protocols outlined in this guide, drug discovery professionals can significantly mitigate the inherent risks of virtual screening and accelerate the journey toward novel therapeutics.

Building the Validation Protocol: A Step-by-Step Methodological Guide

Virtual screening has become an indispensable technology in modern drug discovery, serving as a productive and cost-effective approach for identifying novel lead compounds [43]. Within this domain, pharmacophore-based virtual screening represents a powerful ligand- and structure-based strategy that identifies bioactive molecules by mapping essential steric and electronic features necessary for molecular recognition [44]. The retrospective validation of pharmacophore screening protocols provides critical insights into method performance and reliability before committing substantial experimental resources. This comparative guide examines current pharmacophore modeling methodologies, their operational workflows, and quantitative performance metrics to inform researchers' selection of virtual screening strategies tailored to specific project requirements and constraints.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Pharmacophore Screening Methods

The virtual screening performance of pharmacophore methods is typically evaluated using several key metrics. The enrichment factor (EF) describes how many-fold better a pharmacophore model performs at selecting active compounds compared to random selection [42]. The goodness-of-hit (GH) score determines how well a model prioritizes a high yield of actives while maintaining a low false-negative rate during database searches [42]. Accuracy (Acc) represents the overall correctness of predictions, while early enrichment (EE) specifically measures performance in identifying active compounds within the top-ranked results [19].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Pharmacophore Screening Methods

| Method | Enrichment Factor (EF) | Goodness-of-Hit (GH) | Early Enrichment | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling [42] | High (specific values not provided) | High (specific values not provided) | Not Reported | Not Reported |

| PharmaGist [43] | Comparable to state-of-the-art tools | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported |

| PharmacoForge [12] | Surpasses other methods in LIT-PCBA benchmark | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported |

| LigandScout [19] | Not Reported | Not Reported | Among best performing in case studies | High |

Table 2: Methodological Comparison and Applications

| Method | Approach | Data Requirements | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Workflow [42] | MCSS fragment placement with machine learning classification | Protein structure (experimental or modeled) | GPCR targets, orphan receptors |

| PharmaGist [43] | Ligand-based multiple alignment | Set of active ligands | Targets without structural data |

| PharmacoMatch [45] | Neural subgraph matching | Pre-computed conformational database | Ultra-large library screening |

| PharmacoForge [12] | Diffusion model generation | Protein pocket structure | Rapid query generation, valid commercially available molecules |

| FragmentScout [46] | Fragment-based pharmacophore aggregation | XChem fragment screening data | Fragment-to-hit optimization |

Experimental Protocols and Workflow Methodologies

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol