Resolving Poor Enrichment in Pharmacophore Virtual Screening: A Strategic Guide for Drug Discovery Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing the common yet critical challenge of poor enrichment in pharmacophore-based virtual screening.

Resolving Poor Enrichment in Pharmacophore Virtual Screening: A Strategic Guide for Drug Discovery Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals facing the common yet critical challenge of poor enrichment in pharmacophore-based virtual screening. It begins by establishing a foundational understanding of pharmacophore models and the multifaceted causes of screening failure, from inadequate model quality to limitations in conformational sampling. The content then details advanced methodological approaches, including hybrid screening strategies and machine learning acceleration, supported by recent research and software tools. A dedicated troubleshooting section offers systematic diagnostics and optimization techniques for refining both ligand- and structure-based models. Finally, the guide covers rigorous validation protocols and comparative analysis of methods, empowering scientists to significantly improve their screening hit rates and efficiency in identifying novel bioactive compounds.

Understanding Pharmacophore Models and the Root Causes of Poor Enrichment

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the official definition of a pharmacophore, and why is precise terminology important for troubleshooting screening failures?

According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [1] [2] [3]. It is a purely abstract concept that describes the common molecular interaction capacities of a group of active compounds, not a specific molecule or functional group [4] [5].

Precise terminology is critical for troubleshooting. Misinterpreting the pharmacophore as a specific chemical scaffold (e.g., a dihydropyridine) rather than an abstract set of features can lead to an overly rigid screening query. This narrow focus may miss valid hits from different chemical classes that possess the required steric and electronic features but are structurally distinct—a process known as "scaffold hopping" [4] [6]. A correct, feature-based understanding of the pharmacophore is the first step in diagnosing poor enrichment.

FAQ 2: What are the core pharmacophore features, and how can incorrect feature assignment lead to poor virtual screening results?

The core pharmacophore features represent the key chemical functionalities involved in ligand-target binding. Incorrectly defining these features is a primary source of poor enrichment, as the query will not accurately represent the essential interactions [2] [6].

Table 1: Core Pharmacophore Features and Their Roles in Molecular Recognition

| Feature Type | Geometric Representation | Role in Supramolecular Interactions | Common Structural Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Vector or Sphere | Forms hydrogen bonds with donor groups on the target [6]. | Carbonyl oxygen, ether oxygen, nitrogen in amines [6]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | Vector or Sphere | Forms hydrogen bonds with acceptor groups on the target [6]. | Amine (-NH₂), hydroxyl (-OH), amide (-NH-) groups [6]. |

| Hydrophobic (H) | Sphere | Engages in van der Waals interactions and hydrophobic effects [1] [2]. | Alkyl chains, alicyclic rings, non-polar aromatic rings [6]. |

| Positive Ionizable (PI) | Sphere | Forms electrostatic or cationic-π interactions with negative sites [6]. | Protonated amines, ammonium ions [2] [6]. |

| Negative Ionizable (NI) | Sphere | Forms electrostatic interactions with positive sites [6]. | Carboxylates, phosphate groups [2] [6]. |

| Aromatic (AR) | Plane or Sphere | Participates in π-π stacking or cation-π interactions [6]. | Phenyl, pyridine, indole, or other aromatic rings [1] [6]. |

FAQ 3: Beyond missing key features, what are the other major causes of poor enrichment in pharmacophore-based virtual screening?

Poor enrichment can stem from several issues related to the model's construction and the database being screened:

- Inadequate Conformational Sampling: The bioactive conformation of your training set ligands may not be represented. It is crucial to generate a comprehensive set of low-energy conformations for each molecule during model development to ensure the bioactive pose is included [1] [3].

- Ignoring Steric Clashes (Exclusion Volumes): A model may perfectly match pharmacophore features but still fail if the molecule sterically clashes with the binding site. Incorporating exclusion volumes (XVOL) is essential to represent forbidden areas of the binding pocket, thereby improving selectivity [2] [6]. These can be derived from a protein-ligand complex structure or from the union of shapes of aligned active molecules [6].

- Using a Non-representative Training Set: The set of molecules used to build a ligand-based model must be structurally diverse yet share a common mechanism of action, binding to the same site in a similar orientation. Including inactive compounds in the training set can also help identify features that are detrimental to binding [1] [3].

- Poor Quality of the Screening Database: If the 3D database used for virtual screening has incorrect tautomers, protonation states, or lacks conformational diversity, even a perfect pharmacophore model will yield few hits [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: A Step-by-Step Workflow

Follow this logical workflow to systematically diagnose and resolve the most common issues that lead to poor enrichment in pharmacophore virtual screening.

Step 1: Verify Pharmacophore Definition and Feature Assignment

- Action: Re-examine the interaction patterns in your training set of active ligands or the protein-ligand complex. Cross-reference with Table 1 to ensure every critical interaction (e.g., a key hydrogen bond observed in a crystal structure) is mapped to the correct pharmacophore feature.

- What to Check: Look for misclassified features, such as labeling a carbon ring as hydrophobic when it actually participates in a cation-π interaction (which would be an Aromatic feature) [6].

- Fix: Manually refine the automated feature assignment from software tools. Use a structure-based approach if a target structure is available for the highest accuracy [2] [6].

Step 2: Check for Essential Exclusion Volumes

- Action: Determine if your model accounts for the shape of the binding pocket.

- What to Check: If your model retrieves many compounds that fit the features but are too large or bulky, you likely need exclusion volumes.

- Fix: If an experimental protein structure is available, derive exclusion volumes directly from the binding site geometry. For ligand-based models, create a shape constraint from the aligned active molecules [2] [6].

Step 3: Validate the Ligand Conformational Ensemble and Bioactive Pose

- Action: Investigate whether the conformational analysis performed during model generation was sufficient.

- What to Check: Are the low-energy conformations of your known active ligands able to align well with the model? A poor fit suggests the bioactive conformation was not generated.

- Fix: Use more robust conformational search methods (e.g., Monte Carlo, genetic algorithms, systematic torsional sampling) that better explore the conformational space [1] [3]. Consider poling techniques to ensure coverage of high-energy but biologically relevant conformations.

Step 4: Audit Training Set Composition and Diversity

- Action: Critically evaluate the molecules used to build your ligand-based pharmacophore model.

- What to Check: Is the training set too homogeneous? Does it include both highly active and less active/ inactive compounds?

- Fix: Curate a diverse set of active molecules that are confirmed to bind the same target site. Incorporate inactive compounds to help the modeling algorithm identify features that disrupt binding, which refines the model's specificity [1] [3].

Step 5: Interrogate Screening Database Quality and Preprocessing

- Action: Examine the virtual compound library you are screening.

- What to Check: Verify the pre-processing protocol for the database. Were 3D structures generated, and were multiple conformations calculated for each molecule? Were correct protonation states and tautomers generated at a physiological pH (e.g., ~7.4)?

- Fix: Reproduce the database generation using a standardized and rigorous protocol, ensuring comprehensive conformational sampling and correct chemical representation [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

| Item / Resource | Category | Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Data Resource | Primary repository for 3D structural data of biological macromolecules. Essential for structure-based pharmacophore modeling [2]. |

| Catalyst/HypoGen | Software Algorithm | An automated system for generating 3D predictive pharmacophore models from a set of active and inactive ligands [3]. |

| Phase | Software Algorithm | A tool for pharmacophore perception, 3D-QSAR model development, and 3D database screening [3] [7]. |

| LigandScout | Software Algorithm | Used to create structure-based pharmacophore models from protein-ligand complexes [7] [6]. |

| Exclusion Volumes (XVOL) | Model Component | Spatial constraints in a pharmacophore model that represent forbidden areas of the binding site, crucial for improving selectivity [2] [6]. |

| Dynamic Combinatorial Chemistry (DCC) | Methodological Approach | A technique to identify novel receptors or ligands by allowing a target biomolecule to template the self-assembly of its own binder from a dynamic library [8] [9]. |

| Covalent Organic Frameworks | Advanced Materials | Porous crystalline materials that can be designed using DCC principles; potential applications in drug delivery or sensing [8]. |

Critical Limitations of Scoring Functions and High False Positive Rates

FAQs: Understanding Scoring Function Limitations

1. What are the primary limitations of current scoring functions in virtual screening? Current scoring functions face several critical limitations that directly impact virtual screening success rates. They often struggle to accurately predict the true binding affinity between a ligand and its target protein. This is primarily due to imperfect mathematical algorithms that fail to fully capture the complexity of molecular interactions. The consequence is a high false positive rate, where many compounds predicted to be active fail experimental validation. In some docking campaigns, analysis has shown median false positive rates as high as 83%, meaning the majority of computationally predicted "hits" are inactive in biological assays [10] [11].

2. How does protein flexibility contribute to false positives in virtual screening? Protein flexibility presents a fundamental challenge in structure-based virtual screening. Conventional docking methods often treat protein receptors as rigid entities, neglecting the dynamic conformational changes that occur in binding sites upon ligand interaction. This simplification can lead to inaccurate binding pose predictions and compromised affinity estimates. While approaches like ensemble docking and molecular dynamics simulations can address flexibility, they significantly increase computational complexity and processing time [11].

3. What role does structural data quality play in virtual screening accuracy? The reliability of virtual screening outcomes is heavily dependent on the quality of the target protein structures used. Experimental structures obtained through X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM may contain resolution limitations, missing residues, or crystallization artifacts that affect binding site representation. Additionally, the protonation states of residues, placement of hydrogen atoms (often absent in X-ray structures), and identification of water molecules in binding sites all significantly influence scoring function performance and consequent false positive rates [11] [12].

Troubleshooting Guides for Poor Enrichment

Issue: High False Positive Rates in Screening Results

Diagnosis Steps:

- Analyze the chemical characteristics of your false positives using cheminformatics tools

- Check for systematic biases in your compound library toward certain molecular properties

- Validate your scoring function against known active and inactive compounds for your target

- Assess binding site flexibility through molecular dynamics simulations if possible

Solutions:

- Implement Multi-Step Filtering: Combine structure-based and ligand-based approaches in sequential workflows to improve enrichment. Start with pharmacophore screening before molecular docking, and incorporate additional post-docking filters like binding free energy calculations (MM-PBSA) and molecular dynamics simulations to verify binding stability [10] [13].

- Use Consensus Scoring: Employ multiple scoring functions with different algorithmic foundations rather than relying on a single scoring method. This approach helps mitigate individual scoring function biases and improves hit identification reliability [11].

- Incorporate Experimental Data: Integrate known structure-activity relationship data to refine and validate your virtual screening protocol, giving higher weight to compounds with features associated with confirmed activity [10].

Issue: Inaccurate Binding Affinity Predictions

Diagnosis Steps:

- Compare predicted versus experimental binding affinities for known ligands

- Check for correlation between docking scores and biological activity for reference compounds

- Analyze if specific interaction types are consistently over- or under-estimated

Solutions:

- Advanced Scoring Methods: Supplement traditional scoring functions with machine learning-based approaches that can capture complex patterns in protein-ligand interactions more effectively. Recent studies show deep learning scoring functions can outperform classical empirical functions in early enrichment factors [11] [14].

- Binding Free Energy Calculations: Implement more computationally intensive but accurate methods like molecular mechanics with Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) for promising candidates. Research demonstrates strong correlation between calculated binding free energies and experimental activity, with successful applications showing superior binding energies for true hits compared to reference compounds [10] [13].

- Pharmacophore Constraints: Incorporate pharmacophore-based constraints during docking to ensure identified compounds not only have favorable scores but also form essential interactions with key binding site residues [15] [16].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol: Multi-Step Virtual Screening with Enhanced Specificity

Purpose: To reduce false positive rates through sequential filtering approaches.

Materials:

- Target protein structure (PDB format)

- Compound library (e.g., ZINC, PubChem, Enamine)

- Molecular docking software (AutoDock Vina, GOLD, or similar)

- Pharmacophore modeling software (ZINCPharmer, LigandScout, or similar)

- Molecular dynamics simulation package (GROMACS, AMBER, or similar)

Methodology:

- Initial Pharmacophore Screening: Develop a pharmacophore model based on known active compounds or protein binding site features. Screen compound library to identify molecules matching essential interaction features [15] [12].

- Molecular Docking: Dock pharmacophore-filtered compounds to the target binding site using multiple scoring functions. Retain top-ranking compounds based on consensus scores [11].

- Binding Free Energy Estimation: Calculate binding free energies using MM-PBSA or similar methods for the top candidates. Prioritize compounds with favorable energy values [10] [13].

- ADMET Profiling: Evaluate absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity properties to eliminate compounds with undesirable pharmacokinetic profiles [13] [15].

- Molecular Dynamics Validation: Perform molecular dynamics simulations (typically 100-300 ns) to assess binding stability, interaction persistence, and complex structural integrity [10] [13].

Expected Outcomes: This protocol significantly enriches true positives, with demonstrated success in identifying potent inhibitors with binding affinities superior to clinical candidates in published studies [13].

Protocol: False Positive Identification Through Experimental Correlation

Purpose: To establish correlation between computational predictions and experimental results for method validation.

Materials:

- Virtual screening hit compounds

- Relevant biological assay system for target protein

- Control compounds (known actives and inactives)

Methodology:

- Select representative compounds from virtual screening results, including high-scoring and moderate-scoring candidates

- Test selected compounds in dose-response biological assays to determine actual potency (IC50, Ki values)

- Compare computational scores with experimental activities to identify scoring function biases

- Analyze structural features distinguishing true positives from false positives

- Refine screening protocols based on identified patterns to improve future screening enrichment

Expected Outcomes: Systematic analysis typically reveals specific molecular features or interaction patterns that correlate with false positives, enabling development of targeted filters to improve subsequent screening campaigns [11] [17].

Quantitative Data on Scoring Performance

Table 1: Documented Performance Metrics of Virtual Screening Approaches

| Screening Method | Reported False Positive Rate | Key Limitations | Successful Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Molecular Docking | Median of 83% in docking campaigns [11] | Inaccurate binding affinity prediction; Rigid receptor treatment | Hit identification for kinase targets [10] |

| Pharmacophore-Based Screening | Varies by model quality (~30-60%) [15] | Limited to defined interaction features; Conformational sampling | MAO-B inhibitor discovery [15]; KHK-C inhibitor identification [13] |

| Machine Learning-Enhanced Screening | Lower than classical methods (study-dependent) [14] | Training data dependency; Black box predictions | DiffPhore for binding conformation prediction [14] |

| Multi-Step Virtual Screening | Significantly reduced through sequential filtering [13] | Computational resource intensity; Protocol complexity | KHK-C inhibitors with docking scores from -7.79 to -9.10 kcal/mol and binding free energies from -57.06 to -70.69 kcal/mol [13] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Improved Virtual Screening

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Virtual Screening | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina [11] | Molecular docking with efficient scoring | General protein-ligand docking studies |

| ZINCPharmer [15] | Pharmacophore-based screening of compound libraries | Screening alkaloids and flavonoids for MAO-B inhibition [15] |

| Gnina [11] | Deep learning-based molecular docking | Improved scoring accuracy with convolutional neural networks |

| AncPhore/DiffPhore [14] | Advanced pharmacophore modeling and mapping | AI-enhanced pharmacophore screening and binding conformation prediction |

| ZINC Database [14] | Publicly available compound library for screening | Source of 280,096 representative ligands in LigPhoreSet [14] |

| PharmaGist [15] | Pharmacophore model development from active compounds | Aligning active molecules to identify common pharmacophore features |

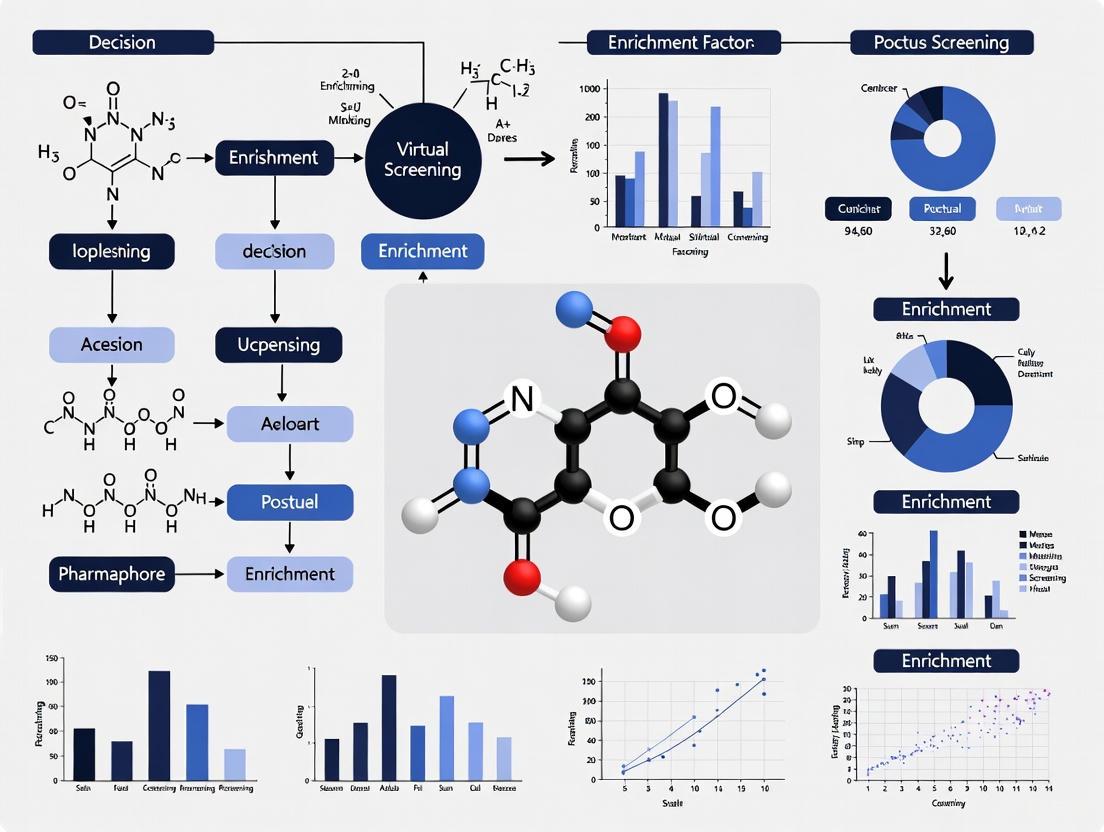

Workflow Visualization

Integrated Screening Workflow to Mitigate False Positives

Key Technical Recommendations

Based on current research, the most effective strategy to address scoring function limitations involves integrating multiple computational approaches rather than relying on any single method. The implementation of sequential filtering steps - beginning with pharmacophore screening, followed by molecular docking with consensus scoring, binding free energy calculations, ADMET prediction, and molecular dynamics validation - has demonstrated significant improvement in reducing false positive rates while identifying genuinely active compounds [10] [13] [11].

Emerging approaches incorporating artificial intelligence and machine learning show particular promise for enhancing scoring function accuracy. Methods like DiffPhore, which uses knowledge-guided diffusion frameworks for ligand-pharmacophore mapping, represent the next generation of virtual screening tools that can better capture the complex relationship between chemical structure and biological activity [14].

The Impact of Protein Flexibility and Inadequate Conformational Sampling

Troubleshooting Guide: Poor Enrichment in Pharmacophore Virtual Screening

This guide helps diagnose and resolve the common issue of poor enrichment in pharmacophore-based virtual screening (VS), where your screening fails to sufficiently prioritize active compounds over inactive ones.

Diagnostic Questions

To identify the root cause of poor enrichment in your experiments, please answer the following:

- What is the source of your target protein's structure?

- A single, static X-ray crystal structure.

- Multiple crystal structures (e.g., from PDB).

- A structure model generated computationally (e.g., via homology modeling).

- Does your pharmacophore model account for protein motion?

- No, it is derived from a single, rigid conformation.

- Yes, by using an ensemble of protein structures.

- Yes, by using models from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.

- Is the binding site highly flexible?

- No, it is relatively rigid.

- Yes, it involves side-chain rearrangements.

- Yes, it involves large loop or backbone movements.

- Are your ligands highly flexible?

- No, they are mostly rigid.

- Yes, they contain multiple rotatable bonds.

- Yes, they are macrocycles or peptides.

Root Cause Analysis and Solutions

Based on your answers, the table below outlines common root causes and their respective solutions.

| Root Cause | Description & Impact | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Oversimplified Static Model | Using a single, rigid protein structure fails to represent true binding site conformations, leading to missed hits that require alternative protein shapes [18] [19]. | Adopt an Ensemble Docking Approach: Use multiple, experimentally determined protein conformations for screening [19]. |

| Inadequate Handling of Loop/Flap Flexibility | Key binding site regions (e.g., flexible loops) can adopt multiple conformations that gate ligand access. A single, incorrect loop conformation can preclude binding of valid hits [19]. | Incorporate Key Flexible Regions Explicitly: Use experimental data (like crystallographic occupancies) to model and weight alternative loop conformations energetically [20]. |

| Poor Ligand Conformational Sampling | The computational generation of ligand 3D conformations is incomplete, especially for flexible or macrocyclic compounds. This fails to produce a bioactive conformation that matches the pharmacophore model [21]. | Employ Enhanced Sampling for Ligands: Use accelerated Molecular Dynamics (aMD) to overcome high energy barriers and thoroughly sample the conformational space of challenging ligands [21]. |

| Insufficient Protein Dynamics in Model | Even an ensemble of static structures may miss crucial, transiently populated states that are important for ligand recognition [18] [22]. | Utilize Pharmacophores from Molecular Dynamics (MD): Derive pharmacophore models from snapshots of an MD simulation trajectory to capture the dynamic spectrum of protein-ligand interactions [18]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Principles

Q1: Why is protein flexibility so critical in pharmacophore virtual screening? Proteins are dynamic and can adopt multiple conformations. A pharmacophore model based on a single, rigid structure represents only one possible binding mode. Many active compounds might require a slightly different protein shape to bind effectively. Ignoring this flexibility leads to false negatives and poor enrichment in your screen [18] [22].

Q2: What is the fundamental difference between "induced-fit" and "conformational selection"? These are two mechanisms describing how ligands and proteins adapt during binding.

- Induced-fit suggests the ligand binds first, and the protein changes its conformation afterward.

- Conformational selection proposes that the protein already exists in an ensemble of conformations, and the ligand selectively binds to and stabilizes a pre-existing, complementary state [22]. In reality, most binding events involve a combination of both mechanisms [22].

Methodologies and Protocols

Q3: What is a practical protocol for creating dynamics-aware pharmacophore models?

The following workflow can be implemented using open-source tools like pharmd [18]:

Detailed Steps:

- System Preparation: Start with a high-resolution crystal structure of a protein-ligand complex. Parameterize the ligand using a tool like

antechamberwith the GAFF force field, and the protein with a force field like Amber99SB-ILDN [18]. - MD Simulation: Run an all-atom MD simulation in explicit solvent (e.g., TIP3P water) for a sufficient time (e.g., 50 ns) to capture relevant motions. Use GROMACS or similar software [18].

- Snapshot Extraction: Extract individual protein-ligand snapshots from the trajectory at regular intervals (e.g., every 20 ps) [18].

- Pharmacophore Generation: For each snapshot, use a tool like the PLIP library to identify key interaction features (hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic areas, etc.) between the protein and ligand, creating a unique pharmacophore model for each frame [18].

- Model Selection: Calculate a 3D pharmacophore hash for each model, which encodes the spatial arrangement of features. Remove models with duplicate hashes to create a non-redundant set of representative pharmacophores [18].

- Virtual Screening: Screen your compound library against all representative pharmacophores. Rank compounds based on their ability to match multiple models (e.g., using a Conformer Coverage Approach) [18].

Q4: How can I handle protein flexibility if I don't have resources for MD simulations? A robust alternative is ensemble-based virtual screening.

- Protocol: Collect multiple crystal structures of your target protein from the PDB, preferably in different conformational states (e.g., with different ligands or in the apo form). Superimpose these structures and dock your compound library into each one separately. Combine the results by taking the best docking score for each compound across all structures [19].

- Rationale: This approach simulates the process of conformational selection, increasing the chance that a flexible ligand will find a compatible protein conformation [23].

Data and Reagents

Q5: How do different sampling methods compare for tackling conformational challenges?

The table below compares enhanced sampling techniques, which are crucial for adequate sampling.

| Method | Principle | Best For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accelerated MD (aMD) [21] [24] | Flattens the energy landscape by adding a bias potential to overcome high energy barriers. | Global sampling of complex conformational changes (e.g., macrocycle ring flips, peptide bond isomerization) [21]. | A global method that doesn't require predefined coordinates; can speed up sampling by orders of magnitude [21] [24]. |

| Replica-Exchange MD (REMD) [24] | Runs parallel simulations at different temperatures, allowing exchanges to escape local energy minima. | Studying protein folding and systems with energy landscapes that are not excessively rough [24]. | Computational cost scales with system size; requires significant resources for large proteins [24]. |

| Metadynamics [24] | Adds a history-dependent bias potential along predefined Collective Variables (CVs) to explore free energy surfaces. | Characterizing specific conformational transitions where the reaction pathway is known and can be described by CVs [24]. | Efficiency highly depends on the correct choice of CVs [24]. |

Q6: What are the essential research reagents and computational tools for these experiments?

The following table lists key resources for setting up advanced, flexibility-aware screening workflows.

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Software & Tools | |

| GROMACS/NAMD | Molecular dynamics simulation packages for generating conformational ensembles [18] [24]. |

pharmd |

Open-source software for pharmacophore model retrieval from MD trajectories and virtual screening [18]. |

| PLIP | A tool for automatically detecting pharmacophore features from protein-ligand complex structures [18]. |

| Rosetta Abinitio | A fragment-based method for protein structure prediction, useful for studying sampling limitations [25]. |

| Databases | |

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary source for experimentally-determined protein structures to build initial models and conformational ensembles [2] [19]. |

| DUD-E Dataset | A benchmark dataset containing known active compounds and decoys for validating virtual screening methods [18]. |

| Methodologies | |

| 3D Pharmacophore Hashing | A method to identify and remove duplicate pharmacophore models, ensuring a diverse and non-redundant set for screening [18]. |

| Conformational Coverage Approach (CCA) | A ranking method that scores compounds based on how many of their conformers can fit a diverse set of protein pharmacophore models [18]. |

| Energy-Weighted VS (EWVS) | A technique that combines multiple protein conformations into a single grid using a weighted energy average, reducing computational cost [19]. |

The workflows and solutions for handling protein flexibility can be visualized as complementary paths to a common goal, as shown below.

Challenges in Pharmacophore Feature Selection and Alignment Accuracy

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why does my pharmacophore model retrieve many inactive compounds during virtual screening?

Poor enrichment is frequently caused by an inadequate selection of pharmacophore features. A model with too few features may lack the specificity to distinguish active from inactive compounds. Conversely, a model with an excessive number of overly restrictive features might miss valid active compounds that make alternative interactions. This often occurs when features are selected without considering the essential interactions for binding, including those from key water molecules or protein backbone atoms [26]. Furthermore, neglecting to incorporate shape constraints or exclusion volumes can result in molecules that match the feature arrangement but are sterically incompatible with the binding site, leading to false positives [6] [27].

FAQ 2: My pharmacophore aligns well with known active ligands but fails in virtual screening. What is wrong?

This discrepancy often stems from the alignment algorithm's optimization goal. Traditional algorithms often prioritize minimizing the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of matched features. This can lead to a perfect alignment of a small subset of features while ignoring a larger set that could be matched within tolerance, a problem known as "false-negative" alignments [28]. The underlying issue is a disconnect between the algorithm's goal (optimizing RMSD or volume overlap) and the actual goal of pharmacophore screening (maximizing the number of matched features within tolerance). Using alignment methods like Greedy 3-Point Search (G3PS), which explicitly maximize the number of matched feature pairs, can mitigate this problem [28].

FAQ 3: How can I create a reliable pharmacophore when no co-crystal structure with a ligand is available?

Creating a pharmacophore without a bound ligand (an apo structure) is challenging but feasible with structure-based methods. The process involves identifying the binding site and then predicting favorable interaction points using probe fragments or deep learning. The key challenge is selecting the most relevant features from a potentially large set of initial candidates. Deep geometric reinforcement learning methods, such as PharmRL, can automate this selection process by learning to identify an optimal subset of interaction points that form a functional pharmacophore for virtual screening [29]. Additionally, using multi-state modeling with tools like AlphaFold2 can generate alternative protein conformations, providing a more diverse structural basis for pharmacophore generation [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Poor Virtual Screening Enrichment

Problem: The pharmacophore model retrieves a high percentage of inactive compounds (low enrichment) in virtual screening.

Solution: Systematically refine the pharmacophore hypothesis and validate the model.

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Diagnosis | Perform a negative control: screen a set of known inactive compounds (decoys) alongside actives. | If the model retrieves a high number of inactives, it lacks specificity. Analysis of how inactives match the model reveals overly permissive features [26]. |

| 2. Feature Audit | Critically assess each feature's necessity using available Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) data or mutagenesis studies. | Remove redundant or non-essential features. A feature is essential if its removal significantly decreases the model's ability to recognize known actives [6] [26]. |

| 3. Add Shape Constraints | Incorporate exclusion volumes (XVOL) or a shape-focused component. | Prevents steric clashes and ensures ligands fit within the binding site cavity. Tools like O-LAP can generate optimized shape models from docked active ligands [6] [27]. |

| 4. Algorithm Check | Verify if the alignment algorithm maximizes feature matching. | If using an algorithm that optimizes for RMSD, switch to one like G3PS that maximizes the number of matched features within tolerances [28]. |

| 5. Validation | Use a separate test set of active and inactive compounds not used in model generation. | Quantify performance using metrics like enrichment factor (EF) or area under the ROC curve (AUC) to ensure model robustness [29]. |

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Suboptimal Pharmacophore Alignment

Problem: The software fails to find a valid alignment for molecules that are known to be active, or the alignments seem chemically unreasonable.

Solution: Address issues related to the alignment algorithm, conformational sampling, and pharmacophore definition.

| Step | Action | Rationale & Technical Details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Check Tolerances | Review and adjust the tolerance radii for pharmacophore features. | Overly tight tolerances (small radii) are a common cause of alignment failure. Increase radii slightly (e.g., from 1.0 Å to 1.2 Å) to accommodate slight conformational variations [28]. |

| 2. Inspect Conformations | Ensure the ligand's conformational ensemble includes a bioactive-like conformation. | Use conformer generation tools that produce diverse, low-energy conformations. A missing bioactive conformation will guarantee alignment failure [28] [14]. |

| 3. Review Feature Types | Check for incorrect or overly specific feature typing. | A feature might be defined as an aromatic ring (AR) when a general hydrophobic (H) feature would suffice, allowing a wider range of chemotypes to match [6]. |

| 4. Evaluate Algorithm | Investigate if the algorithm's objective function is the cause. | Algorithms like the RM method may find alignments with good RMSD for fewer features but miss valid alignments with more features. Use algorithms designed to maximize feature matches [28]. |

| 5. Optional Features | If supported, mark less critical features as "optional". | This reduces combinatorial complexity during matching. However, be cautious as it can decrease model specificity if overused [28]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Generating a Robust Structure-Based Pharmacophore

This protocol details the creation of a structure-based pharmacophore from a protein-ligand complex, emphasizing steps to enhance feature selection [2] [26].

Title: Workflow for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Diagram Specification:

Methodology:

- Protein Structure Preparation:

- Source: Obtain the 3D structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or generate a high-quality model using tools like AlphaFold2 [30] [2].

- Processing: Add hydrogen atoms, assign protonation states at physiological pH, and correct any structural anomalies (e.g., flipping asparagine or glutamine sidechains) using software like MOE, Schrodinger's Protein Preparation Wizard, or similar [26].

- Binding Site Detection:

- Pharmacophore Feature Generation:

- From a Complex: Analyze the protein-ligand interactions (hydrogen bonds, ionic interactions, hydrophobic contacts, etc.) to place corresponding pharmacophore features (HBA, HBD, PI, NI, H, AR) onto the ligand's functional groups [6] [2].

- From an Apo Structure: Use methods like probe docking (e.g., with small molecular fragments) or interaction map calculations (e.g., with GRID) to identify favorable locations for specific chemical features in the binding site [26] [29].

- Critical Feature Selection:

- Initial Model: The previous step often generates a large number of features. An initial model may contain all features from the bound ligand or many probe-derived points.

- Selection Strategy: Reduce the feature set to the essential ones. This can be guided by:

- Energy Criteria: Retain features involved in strong, energetically favorable interactions [26].

- Conservation: If multiple complex structures are available, select features that are consistently formed across different ligands [6].

- Mutagenesis Data: Prioritize features interacting with residues known to be critical from site-directed mutagenesis studies [26].

- Reinforcement Learning: For apo structures, tools like PharmRL can automatically select an optimal subset of CNN-predicted interaction points to form a functional pharmacophore [29].

- Add Constraints: Incorporate exclusion volumes (spheres where ligand atoms are not allowed) to represent the shape of the binding site and prevent steric clashes [6] [27].

Protocol 2: Optimizing a Pharmacophore Model Using Negative Image-Based Screening

This protocol uses a shape-focused approach to improve the performance of an existing pharmacophore model or docking workflow [27].

Title: Workflow for Shape-Focused Model Optimization

Diagram Specification:

Methodology:

- Input Generation:

- Perform flexible molecular docking of a set of known active ligands into the target's binding site.

- Collect the top-ranked pose for each of the 50 most highly-ranked active ligands to create an ensemble of poses that fill the binding cavity [27].

- Preprocessing:

- Merge all poses into a single file.

- Remove non-polar hydrogen atoms and delete covalent bond information. The input is now a cloud of atoms filling the binding pocket [27].

- Graph Clustering:

- Use a tool like O-LAP to perform pairwise distance-based graph clustering on the atom cloud.

- Apply atom-type-specific radii. Overlapping atoms of the same type are clustered together to form representative centroids. This dramatically reduces redundancy and creates a manageable set of shape points [27].

- Model Generation and Screening:

- The output of O-LAP is a shape-focused pharmacophore model.

- Use this model to rescore a database of compounds (e.g., docking poses from a virtual screen) by calculating shape/electrostatic potential similarity using a tool like ShaEP [27].

- Enrichment-Driven Optimization (Optional):

- To maximize performance, a brute-force negative image-based optimization (BR-NiB) can be run.

- This is a greedy search algorithm that iteratively modifies the model's composition (e.g., by adding, removing, or shifting points) and evaluates the change based on its virtual screening enrichment factor. The best-performing model is selected for final use [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key software tools and their primary functions relevant to addressing challenges in pharmacophore feature selection and alignment.

| Tool Name | Type / Category | Primary Function in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| Greedy 3-Point Search (G3PS) [28] | Alignment Algorithm | Replaces RMSD-minimizing algorithms; maximizes the number of matched feature pairs to reduce false negatives. |

| PharmRL [29] | Feature Selection / AI | Uses deep reinforcement learning to automatically select an optimal subset of pharmacophore features from a protein binding site, especially in the absence of a bound ligand. |

| O-LAP [27] | Shape Modeling / Clustering | Generates shape-focused pharmacophore models by clustering overlapping atoms from docked active ligands. Used for docking rescoring and improving enrichment. |

| DiffPhore [14] | AI-based Conformation Generation | A knowledge-guided diffusion model for "on-the-fly" 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping. Aids in predicting correct binding conformations that align with a pharmacophore model. |

| AlphaFold2 with MSM [30] | Protein Structure Prediction | Generates high-quality protein structures in specific conformational states (e.g., DFG-out for kinases), providing a more accurate template for structure-based pharmacophore modeling. |

| Pharmer [31] | Pharmacophore Search Engine | Provides an efficient and exact pharmacophore search algorithm that scales with query complexity, not database size, enabling rapid virtual screening. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: My virtual screening results in a high false-positive rate and poor enrichment. What are the primary data-related causes? Poor enrichment is frequently traced to the quality of the input data used to generate the pharmacophore model. The primary causes can be:

- Structure-Based Models: Using a protein structure with poor resolution, missing residues in the binding site, or incorrect protonation states [2] [32].

- Ligand-Based Models: Using a training set of ligands with inconsistent biological activity data, low structural diversity, or incorrect bioactive conformations [2] [33].

FAQ 2: How can I validate the reliability of my pharmacophore model before proceeding with large-scale virtual screening? It is essential to validate your model's ability to distinguish active compounds from inactive ones. This is typically done using statistical metrics calculated from a validation test:

- Method: Screen a known dataset containing active compounds and decoys (presumed inactives) [34] [32].

- Key Metrics: Calculate the Enrichment Factor (EF) and Goodness of Hit (GH) score. A high EF and GH score indicate the model can successfully prioritize active compounds [32] [33]. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) of a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve is also a standard metric, with an AUC above 0.8 indicating good predictive power [34].

FAQ 3: What are the critical steps in preparing a protein structure from the PDB for structure-based pharmacophore modeling? Simply downloading a structure from the PDB is insufficient. A rigorous preparation workflow is necessary [2]:

- Quality Assessment: Select a structure with the highest possible resolution and ensure the binding site residues are completely resolved.

- Structure Completion: Use tools like MODELLER to add any missing loops or residues, especially near the binding pocket [32].

- Protonation and Optimization: Add hydrogen atoms, assign correct protonation states to residues (e.g., for Asp, Glu, His), and perform energy minimization to correct steric clashes [2].

FAQ 4: For ligand-based modeling, what constitutes a high-quality training set? A robust training set is the foundation of a predictive model [2] [35]:

- Data Consistency: Use ligands tested in the same biological assay to ensure consistent activity values (e.g., IC₅₀ or Ki).

- Activity Range: The set should cover a wide range of activities, typically 4-5 orders of magnitude (e.g., from nM to μM).

- Structural Diversity: Include multiple chemical scaffolds to prevent the model from overfitting to a specific chemotype [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Enrichment from a Structure-Based Pharmacophore Model

Problem: Your pharmacophore model, built from a protein structure, retrieves few active compounds and many inactives during virtual screening.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action & Methodology | Key Reagents & Tools |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Inspect Input Structure | Action: Critically evaluate the protein structure file (e.g., from PDB).Methodology: Check the resolution (prefer ≤ 2.5 Å), the B-factor (indicating atom stability), and ensure no key binding site residues are missing [2] [32]. | Research Reagent: PDB file of target protein.Software: Molecular visualization tools (e.g., UCSF Chimera, PyMOL). |

| 2. Analyze Binding Site | Action: Manually verify the binding site definition.Methodology: If the structure is a complex with a native ligand, use that ligand to define the site. For apo structures, use dedicated tools like GRID or LUDI to identify potential interaction hotspots [2]. | Software: GRID, LUDI, or CASTp for binding site detection. |

| 3. Refine Feature Selection | Action: Avoid overloading the model with features.Methodology: Select only the essential pharmacophore features (e.g., HBD, HBA, Hydrophobic) that are critical for binding energy. Remove redundant or sterically unlikely features. Incorporate exclusion volumes (XVOL) to represent the shape of the binding pocket [2] [34]. | Software: Pharmacophore modeling suites (e.g., LigandScout, Discovery Studio). |

Issue 2: Poor Predictive Power from a Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Model

Problem: Your model, built from a set of active ligands, fails to predict the activity of new compounds or identify actives from a database.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action & Methodology | Key Reagents & Tools |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Validate Training Set | Action: Re-assess the quality and diversity of your input ligands.Methodology: Calculate molecular fingerprints and perform cluster analysis. Ensure the training set covers a broad chemical space and that activity data is from a single, consistent source [2] [35]. | Software: Cheminformatics toolkits (e.g., RDKit, Canvas).Database: ChEMBL for curated bioactivity data. |

| 2. Test Model Robustness | Action: Perform a cost analysis and Fisher's validation.Methodology: During hypothesis generation (e.g., with HypoGen), a large cost difference between the generated model and the null hypothesis indicates a higher probability of it being true. Use Fischer's randomization test to confirm the model is not generated by chance [35]. | Software: DS HYPOGEN module, PHASE. |

| 3. Map Active/Inactive Ligands | Action: Understand why the model misses known actives.Methodology: Align high-activity and low-activity ligands to the pharmacophore hypothesis. Identify which critical features the low-activity ligands are missing, which can validate the relevance of the model's features [35]. | Software: LigandScout, Discovery Studio, MOE. |

Experimental Protocols for Data Quality Assessment

Protocol 1: Validation of a Structure-Based Pharmacophore Model

This protocol uses a test set of known actives and decoys to quantify model performance before full virtual screening [34] [32].

1. Materials Preparation

- Pharmacophore Model: Your generated structure-based model.

- Validation Database: A set of known active compounds for your target (e.g., from ChEMBL) and a set of decoy molecules (e.g., from DUD-E database). Decoys are chemically similar but physiologically inactive molecules [32].

- Software: Virtual screening software (e.g., LigandScout, Pharmit, Discovery Studio).

2. Methodology

- Step 1: Screening. Use your pharmacophore model as a query to screen the combined database of actives and decoys.

- Step 2: Compile Results. From the screening hits, record:

- Ha: Number of known active compounds retrieved.

- A: Total number of known active compounds in the database.

- Ht: Total number of compounds retrieved (hits).

- D: Total number of decoy compounds in the database.

3. Data Analysis & Interpretation Calculate the following key metrics to assess your model's quality:

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (Recall) | (Ha / A) × 100 | The percentage of known actives successfully retrieved. |

| Specificity | [ (D - (Ht - Ha)) / D ] × 100 | The percentage of decoys correctly rejected. |

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | (Ha / Ht) / (A / (A+D)) | Measures how much better the model is at finding actives than random selection. EF > 1 indicates enrichment. |

| Goodness of Hit (GH) | [ (Ha(3A + Ht) / (4HtA) ] × [ 1 - (Ht - Ha) / (D) ] | A composite score between 0 (null) and 1 (ideal). A score of 0.7-0.8 indicates a very good model [32] [33]. |

Protocol 2: Quantitative Assessment of a Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Hypothesis

This protocol uses the HypoGen algorithm in Discovery Studio as an example to build and statistically validate a ligand-based model [35].

1. Materials Preparation

- Training Set Ligands: A set of 20-30 compounds with known activity (e.g., IC₅₀), spanning a wide activity range (e.g., 10 nM to 100 μM). Ensure structural diversity.

- Software: A pharmacophore modeling suite with a 3D QSAR module (e.g., Discovery Studio).

2. Methodology

- Step 1: Conformational Analysis. For each ligand in the training set, generate a set of representative 3D conformations using the "BEST/Flexible" conformation generation method.

- Step 2: Hypothesis Generation. Submit the training set to the HypoGen module. The algorithm will generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses (models) that correlate features with the observed activity.

- Step 3: Cost Analysis. Examine the statistical cost values for the top hypotheses.

3. Data Analysis & Interpretation A high-quality hypothesis is indicated by specific cost values and correlation.

| Cost Parameter | Description | Ideal Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Total Cost | The cost of the hypothesis. | Should be close to the Fixed Cost. |

| Cost Difference | (Null Cost - Total Cost). | A large difference (>60) indicates a >90% probability that the model is not random [35]. |

| RMSD | Root mean square deviation. | Should be low (<2.0 Å), indicating a good fit of the training set. |

| Correlation (R) | Correlation coefficient. | Should be close to 1. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids. Source of initial protein structures for modeling [2]. | Provides resolution, R-value, and B-factor for quality assessment. |

| DUD-E Database | Directory of Useful Decoys: Enhanced. Provides decoy molecules for validation that are chemically similar to actives but topologically different to avoid true binding [32]. | Critical for calculating Enrichment Factor (EF) and Goodness of Hit (GH) scores. |

| ChEMBL Database | Manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. Source for obtaining reliable bioactivity data for training and test sets [36]. | Provides standardized IC₅₀, Ki, and other activity metrics. |

| LigandScout Software | Advanced software for structure- and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening. Used to create and validate models from PDB structures [37]. | Generates features, exclusion volumes, and performs high-throughput screening. |

| MODELLER | A tool for homology or comparative modeling of 3D protein structures. Used to fill in missing loops or residues in an experimental PDB structure [32]. | Essential for preparing a complete protein structure when the experimental data has gaps. |

| ZINC Database | A free database of commercially-available compounds for virtual screening. Used for finding potential hit compounds after model validation [34] [36]. | Contains millions of purchasable molecules in ready-to-dock 3D formats. |

Advanced Screening Strategies and Modern Computational Approaches

Implementing Structure-Based vs. Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, and how do they impact virtual screening outcomes?

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling relies on the three-dimensional structure of a macromolecular target, typically from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or homology modeling. It involves analyzing the protein's binding site to generate a set of steric and electronic features that are essential for molecular recognition [38] [2]. The workflow includes protein preparation, binding site identification, and the generation and selection of key pharmacophore features from the ligand-protein interaction pattern [2].

In contrast, ligand-based pharmacophore modeling is used when the 3D structure of the target is unknown. It deduces the pharmacophore model by identifying common chemical features and their spatial arrangements from a set of known active compounds. This involves generating 3D conformations of active ligands, aligning them, and extracting the shared features responsible for biological activity [38] [2]. The choice between the two methods depends on data availability. Structure-based methods are more direct but require a high-quality protein structure. Ligand-based methods are broader applicable but depend on the quality, diversity, and accuracy of the ligand activity data [2].

Q2: My virtual screening results in low enrichment—many false positives and few true actives. What are the primary causes and solutions?

Poor enrichment is a common challenge often stemming from an inadequate pharmacophore model. Key causes and their solutions are summarized in the table below.

Table: Troubleshooting Poor Enrichment in Virtual Screening

| Problem Cause | Underlying Issue | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overly restrictive pharmacophore | Too many features reduce hit rate and structural diversity [38]. | Reduce non-essential features; use exclusion volumes sparingly [38]. |

| Overly permissive pharmacophore | Too few features increase false-positive matches [38]. | Add critical features from key ligand-receptor interactions [2]. |

| Static structural model | A single crystal structure may not capture binding site flexibility, leading to inaccurate interactions [39]. | Use Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to generate multiple, refined pharmacophore models from the trajectory [39] [18]. |

| Inadequate ligand conformation | The conformational model of the database compounds is insufficient [18]. | Generate a diverse, energy-aware conformer library (e.g., 100 conformers per compound with a large energy window) [18]. |

| Incorrect binding site definition | The pharmacophore model is built for a non-relevant site [2]. | Use tools like GRID or LUDI, or analyze co-crystallized ligands to define the true binding site [2]. |

Q3: How can molecular dynamics (MD) simulations improve my structure-based pharmacophore models, and what is a practical protocol?

MD simulations incorporate target and ligand flexibility, leading to more robust pharmacophore models that often show better ability to distinguish between active and decoy compounds [39]. A practical protocol is as follows [18]:

- System Preparation: Obtain the initial protein-ligand complex from the PDB. Prepare protein and ligand topologies using force fields (e.g., Amber99SB-ILDN for the protein, GAFF2 for the ligand).

- Simulation Setup: Solvate the system in a water model (e.g., TIP3P) within a dodecahedral box. Perform energy minimization (e.g., ~50,000 steps) followed by NVT and NPT equilibration (100 ps each).

- Production Run: Run an MD simulation under NPT ensemble conditions (e.g., 50 ns, 310 K, 2 fs time step). Monitor convergence using RMSD and gyration radius.

- Snapshot Retrieval: Extract snapshots regularly from the trajectory (e.g., every 20 ps, yielding 2500 snapshots).

- Pharmacophore Generation: For each snapshot, remove water and use a tool like the PLIP library to identify key protein-ligand interactions (H-bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic, aromatic, electrostatic). Convert these interactions into pharmacophore features.

- Model Selection: To avoid processing thousands of similar models, use a method like 3D pharmacophore hashing to select a representative subset of distinct pharmacophores from the MD trajectory for virtual screening [18].

The following diagram illustrates this workflow for generating MD-refined pharmacophores:

Workflow for MD-Refined Pharmacophore Modeling

Q4: What software tools are available for pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening, and how do I choose?

Multiple commercial and open-source software packages are available, each with strengths. The table below lists key tools.

Table: Pharmacophore Modeling Software and Key Features

| Software | Type | Key Features and Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| LigandScout [38] [40] | Commercial | Intuitive interface for structure & ligand-based modeling; advanced visualization; efficient virtual screening [40]. |

| MOE [38] [40] | Commercial | Comprehensive suite with structure-based design, 3D query editor, virtual screening, and molecular docking [40]. |

| Schrödinger Phase [40] | Commercial | Specialized in ligand-based pharmacophore modeling and 3D-QSAR [40]. |

| Pharmit [38] [40] | Free Web Server | Interactive, web-based virtual screening against large compound databases [38] [40]. |

| PharmMapper [38] | Free Web Server | Reverse pharmacophore screening server for potential target identification [38]. |

| pharmd [18] | Open-Source | Implements workflows for generating and using pharmacophore models from MD trajectories [18]. |

Q5: In ligand-based modeling, how does the selection and alignment of training set compounds affect model quality?

The quality of the training set is paramount. If the set of active compounds is too structurally diverse or contains compounds with different binding modes, the resulting pharmacophore model will be inaccurate and contain conflicting features. To ensure quality [38]:

- Curate a High-Quality Set: Select a training set of 20-30 compounds validated experimentally with a range of activities but a shared mechanism of action and binding mode.

- Generate Representative Conformations: Generate a comprehensive set of low-energy 3D conformers for each compound.

- Perform Accurate Alignment: Use the software's algorithm to perform a 3D alignment based on the shared pharmacophore features, not just the molecular scaffold. The model should capture the common spatial arrangement of features essential for activity.

Experimental Protocols for Improved Enrichment

Protocol 1: Generating an MD-Refined Pharmacophore Model

This protocol expands on the workflow above for improving a structure-based model using dynamics [39] [18].

Objective: To create a robust pharmacophore model for CDK2 inhibitors by leveraging MD simulations.

Materials:

- Initial Structure: PDB entry 1OIT (CDK2 in complex with a known inhibitor).

- Software: GROMACS (for MD), PLIP (for interaction analysis), pmapper/pharmd (for pharmacophore hashing and screening).

- Compound Library: DUD-E dataset for CDK2 (actives and decoys).

Method:

- Setup: Prepare the 1OIT system using the Amber99SB-ILDN force field for the protein and GAFF2 for the ligand. Solvate in a TIP3P water box and neutralize.

- Equilibration: Minimize energy (max 50,000 steps). Conduct NVT (100 ps, 310 K) and NPT (100 ps, 1 bar) equilibration.

- Production MD: Run a 50 ns simulation under NPT conditions.

- Analysis: Extract 2500 snapshots (every 20 ps). For each, use PLIP to detect interactions and create a pharmacophore model.

- Selection: Calculate a 3D pharmacophore hash for all models. Remove duplicates to get a representative set.

- Validation: Perform virtual screening against the DUD-E library. Rank compounds using the Conformer Coverage Approach (CCA)—the fraction of a compound's conformers matching any representative model [18].

Protocol 2: Validating a Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Model

This protocol ensures your ligand-based model is predictive before large-scale screening [38].

Objective: To build and validate a ligand-based pharmacophore model for acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.

Materials:

- Training Set: 20 known active compounds with diverse structures but similar potency.

- Test Set: A library containing known actives and decoys/inactive compounds.

- Software: MOE or Schrödinger Phase.

Method:

- Conformer Generation: For each training compound, generate a multi-conformer database.

- Model Building: Input the active compounds into the software. Use the algorithm to find common features and generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses.

- Hypothesis Selection: Test all hypotheses against the test set. Select the model that best separates actives from inacts (e.g., has the highest enrichment factor or best ROC curve).

- Virtual Screening: Use the selected model as a query to screen large compound libraries.

The logical relationship between model generation, validation, and screening is shown below:

Ligand-Based Model Validation Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Resources for Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Tools / Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Database | Source of experimental 3D structures for structure-based modeling. | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [2] |

| Compound Libraries | Collections of small molecules for virtual screening. | DUD-E [39] [18], ZINC, in-house corporate libraries. |

| Force Field Parameters | Define energy functions for MD simulations and conformation generation. | Amber99SB-ILDN (proteins), GAFF2 (ligands), MMFF (conformers) [18]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Engine | Software to simulate atomic-level motion of protein-ligand complexes. | GROMACS [18], AMBER, NAMD. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Platform to build, visualize, and run virtual screening with pharmacophore models. | Listed in Table 2 (e.g., LigandScout, MOE, Pharmit). |

| Conformer Generator | Tool to sample the low-energy 3D shapes of a molecule. | RDKit [18], OMEGA, MOE. |

| 3D Pharmacophore Hash | A unique identifier enabling efficient comparison and selection of distinct pharmacophore models. | Implemented in pmapper and pharmd [18]. |

Integrating Hybrid and Consensus Screening Frameworks

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my virtual screening workflow returning an unacceptably high number of false positives?

A: High false positive rates often stem from inadequate pharmacophore model quality or improper library preparation. To address this:

- Refine Your Pharmacophore Model: Ensure your model includes exclusion volumes (XVOL) to represent the physical boundaries of the binding pocket and prevent steric clashes. A model that is too generic or lacks key steric constraints will match many inactive compounds [2].

- Validate Your Chemical Library: Apply strict Lipinski's Rule of Five and other activity filters during library preparation to remove drug-like unsuitable compounds early in the process [41].

- Check Tautomeric and Protonation States: During the 3D conformation generation of your screening library, ensure that all possible protonation states at the relevant pH and tautomeric states are properly generated. Incorrect charges can lead to invalid feature matching [42].

Q2: My consensus screening approach is computationally expensive. How can I optimize it without sacrificing performance?

A: You can implement an optimal High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) pipeline by strategically allocating computational resources.

- Adopt a Multi-Fidelity Strategy: Use faster, less accurate methods (e.g., 2D fingerprint similarity) as initial filters to reduce the compound pool before applying more computationally intensive, high-fidelity methods (e.g., structure-based pharmacophore screening or molecular docking) [43].

- Formalize your Pipeline: The goal is to maximize the Return on Computational Investment (ROCI). This involves structuring your workflow so that each step effectively narrows the candidate list for the next, more expensive step [43].

Q3: What is the key advantage of using dynamics-derived pharmacophores over a single crystal structure?

A: A single crystal structure provides a static view of protein-ligand interactions, which can miss critical conformational states. Pharmacophores retrieved from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations capture the flexibility and dynamic behavior of the binding site. Using an ensemble of models from an MD trajectory accounts for this flexibility, leading to a more robust and accurate representation of the essential interactions for binding, which ultimately improves virtual screening enrichment [18].

Q4: How do I choose between a structure-based and a ligand-based pharmacophore modeling approach?

A: The choice depends entirely on the available data.

- Use Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling when a reliable 3D structure of the target (e.g., from X-ray crystallography) is available, especially in complex with a ligand. This approach directly maps interaction points from the binding site [2].

- Use Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling when the 3D structure of the target is unknown but you have a set of known active compounds. This method deduces the common steric and electronic features necessary for bioactivity from the alignment of these active ligands [2] [41].

Troubleshooting Guide: Poor Enrichment in Virtual Screening

Problem: Low Hit Rate and Poor Enrichment

A low hit rate, where few truly active compounds are identified from a screened library, indicates poor enrichment. This is a common challenge that can be diagnosed and resolved by checking several key areas of your workflow.

Step 1: Diagnose the Cause

| Symptom | Potential Root Cause |

|---|---|

| High number of hits with poor chemical diversity | Overly generic or permissive pharmacophore model [2]. |

| Hits fail to show activity in laboratory tests despite good model fit | Model does not account for target flexibility; based on a single, non-representative protein conformation [18]. |

| Active compounds from literature are not retrieved by the screen | Inadequate conformational sampling during library preparation; the bioactive conformation was not generated [42]. |

| Hits exhibit poor drug-likeness or ADMET properties | Insufficient pre-filtering of the screening library for undesirable properties [41]. |

Step 2: Implement Corrective Workflow

Follow this workflow to systematically address the causes of poor enrichment. The core of the solution often lies in integrating a hybrid screening strategy and incorporating protein dynamics.

Step 3: Apply Advanced Solutions

Solution 1: Integrate Dynamics with the Conformer Coverage Approach (CCA) Instead of relying on a single model, use an ensemble of pharmacophore models derived from Molecular Dynamics (MD) trajectories.

- Protocol:

- Run an MD simulation (e.g., 50 ns) of the protein-ligand complex using software like GROMACS [18].

- Extract snapshots from the trajectory (e.g., every 20 ps).

- Generate a pharmacophore model for each snapshot using a tool like

pharmd[18]. - Select a representative set of models by removing duplicates using 3D pharmacophore hashes.

- Screen your library against all representative models.

- Rank compounds by the Conformer Coverage Approach (CCA): the number of unique conformers of a compound that match any of the pharmacophore models. A higher score suggests the compound's flexibility complements the protein's flexibility, indicating better binding potential [18].

Solution 2: Employ a Multi-Stage Hybrid Consensus Pipeline Combine different virtual screening methods in a hierarchical workflow to leverage their respective strengths.

Quantitative data on the performance of different screening strategies, based on benchmark studies, is summarized below:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Virtual Screening Strategies

| Screening Strategy | Relative Computational Cost | Key Advantage | Reported Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single Static Pharmacophore | Low | Speed | Lower enrichment; misses key interactions [18]. |

| Ligand-Based Pharmacophore (from known actives) | Medium | No protein structure needed | Good for scaffold hopping; depends on ligand set quality [41]. |

| MD-Based Ensemble Pharmacophore (CCA) | High | Accounts for protein flexibility | Higher hit rates and better enrichment reported [18]. |

| Hybrid Consensus (e.g., Pharmacophore + Docking) | Very High | Combines strengths of multiple methods | Maximizes return on computational investment (ROCI); highest reported accuracy [43]. |

The corresponding workflow for a hybrid consensus pipeline is detailed below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Software and Resources for Pharmacophore Virtual Screening

| Item Name | Function/Benefit | Example Use in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit; used for molecule standardization, tautomer enumeration, and conformer generation [42]. | Generating up to 100 low-energy conformers per compound for the screening library using the ETKDG algorithm [42] [18]. |

| OMEGA (OpenEye) / ConfGen (Schrödinger) | Commercial, high-performance conformer ensemble generators. Systematic sampling of rotatable bonds to ensure broad coverage of conformational space [42]. | Used in the library preparation stage to generate a representative set of bioactive conformations for each molecule [42]. |

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulation package. Used to simulate the flexibility and dynamic behavior of a protein-ligand complex over time [18]. | Running a 50 ns simulation under NPT ensemble at 310 K to generate an ensemble of protein structures for pharmacophore modeling [18]. |

| pharmd | Open-source software designed specifically for retrieving pharmacophore models from MD trajectories and performing virtual screening with them [18]. | Implementing the Conformer Coverage Approach (CCA) to rank compounds after generating models from an MD simulation [18]. |

| PLIP | Protein-Ligand Interaction Profiler. Automatically identifies pharmacophore-relevant interactions (H-bonds, hydrophobic contacts, etc.) from a 3D structure [18]. | Called by pharmd to detect hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic, and aromatic interaction centers in each snapshot of an MD trajectory [18]. |

| ZINC Database | Publicly available database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. Provides millions of molecule structures in ready-to-dock formats [42] [41]. | Sourcing the initial compound library for a virtual screening campaign. Structures can be downloaded and prepared for screening [41]. |

Leveraging Machine Learning for Accelerated Docking Score Prediction

Virtual screening is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, used to identify promising hit compounds from vast chemical libraries. A major challenge researchers face is poor enrichment—the inability of a virtual screening workflow to sufficiently prioritize true active compounds over inactive ones. This drastically reduces the efficiency of downstream experimental testing. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful tool to accelerate the most computationally expensive component of this process: molecular docking and scoring. This technical guide addresses common pitfalls and provides solutions for integrating ML into your docking workflows to achieve superior enrichment rates.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is my ML-guided docking screen failing to identify active compounds despite high computational throughput?

Answer: This is often a problem of data quality or model-generalization, not just algorithm speed.

- Underlying Cause: The machine learning model was trained on data that is not representative of the chemical space you are screening, or it has learned to predict docking scores based on non-causal molecular patterns.

- Solution:

- Ensure Training Set Representativeness: When training an ML model to predict docking scores, use a training set that is a representative sample of the massive library you plan to screen. One proven protocol involves docking a subset of 1 million compounds from your target library to create a robust training set [44].

- Implement Conformal Prediction: To control the error rate of your predictions and add a measure of reliability, use the Mondrian Conformal Prediction (CP) framework. This method provides validity guarantees for both the majority (inactive) and minority (active) classes, which is crucial for the imbalanced datasets typical in virtual screening [44].

FAQ 2: My pharmacophore-based virtual screening has high false-positive rates. How can ML improve specificity?

Answer: Traditional pharmacophore models, especially from a single static structure, can be overly permissive. ML can help by creating more dynamic and integrative models.

- Underlying Cause: A single pharmacophore model may not capture the essential dynamic interactions or the specificity required for high enrichment.

- Solution:

- Use Ensemble Pharmacophores: Generate multiple pharmacophore models from molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories of the protein-ligand complex instead of a single crystal structure. This accounts for protein flexibility and captures a more realistic range of essential interactions [45].

- Apply Advanced Selection and Ranking: Instead of using all pharmacophores from an MD simulation (which is computationally inefficient), select distinct representative models by removing pharmacophores with identical 3D hashes. Then, rank compounds using a Conformers Coverage Approach (CCA), which scores compounds based on how many of their conformers can fit the various protein conformational states represented by the pharmacophore ensemble [45].

- Leverage Pharmacophore-Guided Deep Learning: For de novo molecular generation, use a pharmacophore-guided deep learning approach (PGMG). This method uses a graph neural network to encode spatially distributed pharmacophore features and a transformer decoder to generate novel molecules that match the target pharmacophore, ensuring generated compounds have the foundational features for binding [46].

Answer: A hybrid ML-docking workflow can reduce the required docking calculations by several orders of magnitude.

- Underlying Cause: Docking billions of compounds is computationally prohibitive with standard methods.

- Solution: Implement a workflow where an ML model acts as a smart filter.

- Train a Classifier: Train a machine learning classifier (e.g., CatBoost) on molecular fingerprints (e.g., Morgan2/ECFP4) to predict whether a compound will be a top-scoring docking hit, based on a preliminary docking screen of a small subset (e.g., 1 million compounds) [44].

- Screen the Vast Library: Use the trained ML model to rapidly screen the multi-billion compound library and predict a much smaller subset of "virtual actives."

- Dock the Predicted Subset: Perform explicit molecular docking only on this greatly reduced subset (e.g., ~10% of the original library). This protocol has been shown to reduce the computational cost of structure-based virtual screening by more than 1,000-fold while retaining high sensitivity (c. 88%) for true actives [44].

FAQ 4: I have limited known active compounds for my target. How can I build a reliable model?

Answer: Use ligand-based pharmacophore modeling enhanced by clustering and ensemble learning.

- Underlying Cause: Data scarcity for novel or understudied targets.

- Solution:

- Create a Diverse Training Set: Apply the Butina clustering algorithm to your limited set of known active compounds. Use the Tanimoto coefficient with Extended-Circuit Fingerprints (ECFP4) to cluster molecules by structural similarity. The centroids of these clusters form a diverse and representative training set for pharmacophore model generation [47].