Pharmacophore-Based Screening for Antimicrobial Drug Discovery: A Computational Strategy Against Resistance

This article provides a comprehensive overview of pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) and its pivotal role in addressing the global crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Pharmacophore-Based Screening for Antimicrobial Drug Discovery: A Computational Strategy Against Resistance

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) and its pivotal role in addressing the global crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational concepts of pharmacophore modeling, details the methodologies of structure-based and ligand-based approaches, and presents practical applications in lead identification and optimization. The content further addresses common challenges and limitations, offers strategies for model optimization, and validates the approach through comparative analyses with other virtual screening methods. By synthesizing recent advancements and successful case studies, this article serves as a strategic guide for integrating efficient computational techniques into the antimicrobial discovery pipeline to develop novel, resistance-breaking therapeutics.

Understanding Pharmacophores: The Blueprint for Combatting Antimicrobial Resistance

The pharmacophore concept stands as one of the most fundamental and enduring principles in medicinal chemistry and drug discovery. It provides an abstract framework for understanding molecular recognition—the process by which a biological target selectively identifies and binds its ligand. Formally defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [1], the pharmacophore has evolved from a qualitative concept to a quantitative tool central to modern computational drug discovery. Within antimicrobial research, where the rapid emergence of multi-drug resistant pathogens necessitates accelerated drug development, pharmacophore-based approaches offer powerful strategies for identifying novel scaffolds and optimizing lead compounds. This article traces the historical development of the pharmacophore concept and details its practical application in contemporary antimicrobial drug discovery protocols.

The intellectual genesis of the pharmacophore is traditionally attributed to Paul Ehrlich, who in the late 19th century pioneered systematic studies of structure-activity relationships. Although Ehrlich himself used the term "toxophore" to describe chemical groups responsible for a molecule's biological effects [2] [3], his work established the foundational principle that specific molecular regions mediate biological activity. Research into the term's origins clarifies that Ehrlich did not actually use "pharmacophore" in his writings; the credit for popularizing the modern term belongs to Lemont B. Kier, who published seminal work on the concept between 1967 and 1971 [1] [2]. A critical evolution in the definition occurred in 1960 when F. W. Schueler redefined the pharmacophore to emphasize spatial patterns of abstract features rather than specific chemical groups [2]. This shift from concrete chemical moieties to abstract functional representations enabled the concept's broader application across diverse chemical scaffolds, forming the basis for the contemporary IUPAC definition established in 1998 [1] [3].

Table 1: Historical Evolution of the Pharmacophore Concept

| Time Period | Key Contributor | Conceptual Contribution | Representation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1898 | Paul Ehrlich | Introduced concept of "toxophores" as binding groups [2] [3] | Specific chemical groups |

| 1960 | F. W. Schueler | Redefined concept to emphasize spatial patterns of abstract features [2] | Abstract feature patterns |

| 1967-1971 | Lemont B. Kier | Popularized the modern term "pharmacophore" in publications [1] [2] | 3D arrangement of features |

| 1998 | IUPAC | Formalized standard definition [1] | Ensemble of steric/electronic features |

The Modern IUPAC Definition and Core Features

The IUPAC definition establishes the pharmacophore as an abstract description that captures the essential molecular interaction capabilities of a ligand, independent of its actual chemical structure [1] [3]. This abstraction is crucial—it explains how structurally diverse ligands can bind to a common receptor site and enables the identification of novel scaffolds through de novo design or virtual screening [1]. A well-defined pharmacophore model specifies both the nature and three-dimensional arrangement of key molecular interactions.

Core pharmacophore features include:

- Hydrophobic centroids: Represent regions engaging in van der Waals interactions and fat-soluble contacts [1] [4].

- Aromatic rings: Facilitate π-π stacking and cation-π interactions with target sites [1] [5].

- Hydrogen bond donors/acceptors: Atoms or groups capable of forming directional hydrogen bonds [1] [4].

- Positive/Negative ionizable groups: Features capable of forming electrostatic interactions or salt bridges at physiological pH [1] [4].

These features are typically represented as 3D geometric entities (points, vectors, volumes) with defined spatial relationships (distances, angles, tolerances) [4]. The accompanying diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between a ligand, its abstracted pharmacophore, and the target interaction.

Experimental Protocols in Pharmacophore Model Development

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

Ligand-based approaches derive pharmacophore models from a set of known active ligands, without requiring target structure information. This method is particularly valuable in antimicrobial discovery when the 3D structure of the bacterial target is unknown [3].

Protocol Steps:

Training Set Selection

- Curate a structurally diverse set of 20-30 molecules with confirmed biological activity against the target (e.g., bacterial enzyme) and include known inactive compounds to enhance model discrimination [1].

- Retrieve 3D structures from databases like PubChem [5] in SDF format and prepare structures using tools like MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) by adding hydrogens, optimizing geometry, and correcting charges [6].

Conformational Analysis

Molecular Superimposition

- Systematically superimpose all combinations of the low-energy conformations of the training set molecules [1].

- Align similar bioisosteric functional groups common to all molecules (e.g., phenyl rings, carboxylic acids) [1].

- Select the conformation set (one from each active molecule) that produces the best steric and electronic overlap as the presumed active conformation [1].

Feature Abstraction & Hypothesis Generation

- Transform the superimposed molecules into an abstract representation, converting specific functional groups into pharmacophore features (e.g., hydroxy groups → 'hydrogen-bond donor') [1].

- Use software such as LigandScout [5] or Phase to generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses and select the best model based on statistical significance and comprehensive feature representation [3].

Model Validation

- Test the model against a set of compounds with known activities not included in the training set [1].

- Validate through goodness-of-hit (GH) scoring; a GH score >0.7 indicates a robust model [5].

- Apply the model in virtual screening to assess its ability to retrieve known actives from decoy databases [7].

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Software Tool | Primary Application | Key Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout [5] [7] | Structure & ligand-based modeling | Automated feature identification, MD integration | Commercial |

| MOE [6] | Comprehensive molecular modeling | Pharmacophore query creation, virtual screening | Commercial |

| Phase [3] | Ligand-based modeling | 3D-QSAR integration, consensus modeling | Commercial |

| ZINCPharmer [5] | Virtual screening | Online pharmacophore-based screening | Free web server |

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

Structure-based methods derive pharmacophores directly from the 3D structure of a target protein-ligand complex, providing detailed insights into essential interaction points [3].

Protocol Steps:

Protein-Ligand Complex Preparation

- Obtain the 3D structure from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or predict via AlphaFold [6].

- Prepare the structure by removing water molecules (except structurally important ones), adding hydrogens, assigning partial charges, and correcting protonation states at physiological pH using tools like MOE or Schrodinger Suite [7] [6].

Interaction Analysis & Feature Mapping

Accounting for Flexibility (Molecular Dynamics)

- Perform molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (e.g., 100-300 ns using AMBER or GROMACS) to sample flexible protein conformations and dynamic interaction patterns [7].

- Extract snapshots from the trajectory and generate multiple pharmacophore models to capture the dynamic binding landscape [7].

- Use hierarchical graph representation (HGPM) to visualize and select representative models from MD simulations [7].

Model Refinement & Validation

Application Notes: Pharmacophore-Guided Antimicrobial Discovery

Case Study: Novel Cephalosporin Design

A recent application demonstrates the power of pharmacophore modeling in addressing β-lactam antibiotic resistance [5]. Researchers developed a shared-feature pharmacophore (SFP) model using first and third-generation cephalosporins (cephalothin, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime) as training set. The validated model (GH score = 0.739) comprised hydrogen bond acceptors, hydrogen bond donors, aromatic rings, hydrophobic regions, and negatively ionizable sites [5]. Virtual screening of a ZINC database subset identified hits that were subsequently conjugated with the cephalosporin core ring, generating 30 novel analogs with predicted improved binding to penicillin-binding proteins [5]. Molecular docking and dynamics simulations identified two candidates (Molecule 23 and Molecule 5) with superior binding affinities compared to controls, demonstrating the practical utility of this approach in scaffold hopping and lead optimization for antibiotics [5].

Emerging Integration with Deep Learning

Recent advances integrate pharmacophore guidance with deep learning for generative molecular design. The Pharmacophore-Guided deep learning approach for bioactive Molecule Generation (PGMG) uses graph neural networks to encode spatially distributed chemical features and a transformer decoder to generate molecules [8]. This approach introduces latent variables to model the many-to-many relationship between pharmacophores and molecules, enhancing diversity while maintaining biological relevance [8]. In testing, PGMG generated molecules with strong docking affinities and high scores of validity, uniqueness, and novelty, providing a flexible strategy for both ligand-based and structure-based de novo design—particularly valuable for novel targets with limited known actives [8].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item/Resource | Specification/Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Databases | PubChem [5] | Repository of small molecules with bioactivity data | NCBI |

| ZINC [5] [6] | Commercially available compounds for virtual screening | University of California, San Francisco | |

| ChEMBL [7] [8] | Curated bioactive molecules with drug-like properties | European Molecular Biology Laboratory | |

| Software Tools | LigandScout [5] [7] | Structure & ligand-based pharmacophore modeling | Inte:Ligand |

| MOE [6] | Molecular modeling suite with pharmacophore capabilities | Chemical Computing Group | |

| RDKit [8] | Open-source cheminformatics for feature identification | Open Source | |

| Target Resources | Protein Data Bank [3] | 3D structural data of proteins and complexes | Worldwide PDB |

| AlphaFold [6] | Protein structure prediction | DeepMind/EMBL-EBI | |

| Validation Tools | MD Simulation Packages (AMBER, GROMACS) [7] | Assess binding stability and dynamics | Academic/Commercial |

| Virtual Screening Libraries | Decoy sets for model validation | DUD-E, DEKOIS |

The pharmacophore concept has evolved remarkably from Ehrlich's initial observations to a sophisticated, computationally-driven framework essential to modern drug discovery. In antimicrobial research, where time and resource constraints are critical, pharmacophore-based approaches provide efficient strategies for navigating vast chemical spaces and accelerating the identification of novel therapeutic candidates. As the field advances, integration with machine learning [8], dynamic pharmacophore modeling from MD simulations [7], and sophisticated de novo design algorithms will further enhance our ability to target evolving bacterial resistance mechanisms. The protocols and applications detailed herein provide researchers with practical frameworks for implementing these powerful approaches in their antimicrobial discovery pipelines.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has released the 2024 Bacterial Priority Pathogens List (WHO BPPL), a critical tool in the global fight against antimicrobial resistance (AMR). This list updates the 2017 edition and refines the prioritization of antibiotic-resistant bacterial pathogens to guide research and development (R&D) and public health interventions [9]. The persistent threat of AMR, a global health issue driven by antibiotic misuse and overuse across various sectors, underscores the necessity of this updated list [10]. The 2024 WHO BPPL serves as a guide for prioritizing R&D and investments in AMR, emphasizing the need for regionally tailored strategies and targeting developers of antibacterial medicines, academic and public research institutions, and policy-makers [9].

This document frames the 2024 WHO BPPL within the context of pharmacophore-based screening for antimicrobial drug discovery. As traditional drug discovery pipelines struggle with the lengthy and costly process of bringing new antibiotics to market, computational approaches like pharmacophore modeling offer a pathway to accelerate the identification of novel compounds against the most critical pathogens [11].

The 2024 WHO BPPL categorizes 24 pathogens across 15 families into three priority tiers—critical, high, and medium—based on a multicriteria decision analysis framework [12]. Pathogens were evaluated against eight criteria, and the final ranking was determined by calculating a total score from 0-100% for each pathogen [12].

Priority Tiers and Pathogen Rankings

Table 1: The WHO 2024 Bacterial Priority Pathogens List (BPPL) - Critical and High Priority Pathogens

| Priority Tier | Pathogen | Key Resistance Phenotype | Overall Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Carbapenem-resistant | 84% [12] |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Carbapenem-resistant | Not Specified | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Rifampicin-resistant | Not Specified | |

| Escherichia coli | Third-generation cephalosporin and carbapenem-resistant | Not Specified | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Carbapenem-resistant | Not Specified | |

| High | Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi | Fluoroquinolone-resistant | 72% [12] |

| Shigella spp. | Fluoroquinolone-resistant | 70% [12] | |

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae | Cephalosporin and/or fluoroquinolone-resistant | 64% [12] | |

| Staphylococcus aureus | Methicillin-resistant (MRSA) | Not Specified |

The list highlights the severe and persistent threat posed by Gram-negative bacteria, which dominate the critical priority category due to their resistance to last-resort antibiotics [9] [12]. The results of the expert preferences survey showed a strong inter-rater agreement, and the final ranking demonstrated high stability across different analyses [12].

Criteria for Prioritization

The WHO employed a robust, multi-factorial methodology to ensure the list reflects the most pressing threats. The eight criteria used are [12]:

- Mortality

- Non-fatal burden of disease

- Incidence

- 10-year trends of resistance

- Transmissibility

- Preventability (e.g., through vaccines or infection control measures)

- Treatability (availability and effectiveness of current antibiotics)

- Status of the antibacterial R&D pipeline

The weighting of these criteria was determined through a survey of international experts, ensuring the final ranking reflects a global consensus on the factors that constitute the greatest threat [12].

Application Note: Pharmacophore-Based Screening for Targeting Priority Pathogens

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening represents a powerful computational strategy to accelerate the discovery of novel antibacterial agents, directly addressing the innovation gap highlighted by the WHO BPPL. A pharmacophore is an abstract description of the molecular features necessary for a molecule to interact with a biological target and elicit a pharmacological response [5]. This approach is particularly valuable for targeting priority pathogens with limited treatment options.

Protocol: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

This protocol outlines the steps for identifying prospective inhibitors against a bacterial target, using insights from studies on Salmonella Typhi and novel cephalosporin development [11] [5].

Objective: To identify novel, drug-like compounds from large chemical libraries that can inhibit a specific bacterial target protein.

Materials and Software:

- Training Set Compounds: Known active ligands (e.g., cephalothin, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime for cephalosporin development) [5].

- Chemical Databases: ZINC database, PubChem, or in-house natural product libraries (e.g., 852,445 molecules) [11] [5].

- Software: LigandScout 4.5 or equivalent for pharmacophore modeling; molecular docking software (e.g., MOE); molecular dynamics (MD) simulation software (e.g., GROMACS) [11] [5].

Procedure:

Training Set Selection and Preparation:

- Select a set of 3-5 known active compounds with diverse structures but common activity against the target.

- Retrieve their 3D structures in SDF format from databases like PubChem.

- Generate multiple low-energy conformations for each molecule to account for flexibility.

Common Feature Pharmacophore Model Generation:

- Import the training set compounds into LigandScout.

- Use the "create Ligand-based pharmacophore" function to generate a 3D shared features pharmacophore (SFP) model based on chemical structure alignment.

- The algorithm will identify common molecular features (e.g., Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA), Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD), Aromatic Rings (AR), Hydrophobic regions (H), Negative Ionizable (NI) groups).

- From the generated models, select the one with the highest pharmacophoric fit score and a high Goodness-of-Hit (GH) score (e.g., >0.7) to ensure robustness [5].

Virtual Screening of Chemical Libraries:

- Use the validated pharmacophore model as a 3D query to screen a large chemical database (e.g., ZINCPharmer).

- Filter hits first by their fit value to the pharmacophore model, retaining top-ranking compounds.

- Apply subsequent drug-likeness filters, such as Lipinski's Rule of Five, to remove compounds with unfavorable physicochemical properties.

Molecular Docking and Binding Affinity Assessment:

- Take the filtered hits and perform molecular docking against the 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., LpxH from S. Typhi or Penicillin-Binding Protein) [11] [5].

- Use docking scores and analysis of binding poses (interactions like hydrogen bonds, pi-pi stacking) to select lead compounds with superior binding affinity compared to known controls.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations and Stability Analysis:

- Subject the top docked complexes to MD simulations (e.g., for 100 nanoseconds) to assess the stability of the protein-ligand interaction in a dynamic, solvated environment [11].

- Analyze parameters such as root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), potential energy, and hydrogen bonding patterns. The lead compound should exhibit the highest stability, with low fluctuations and stable hydrogen bonding [11].

In silico ADMET and Toxicity Prediction:

- Finally, predict the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties of the lead compounds to further evaluate their potential as drug candidates. Compounds should show favorable drug-like properties and low toxicity [11].

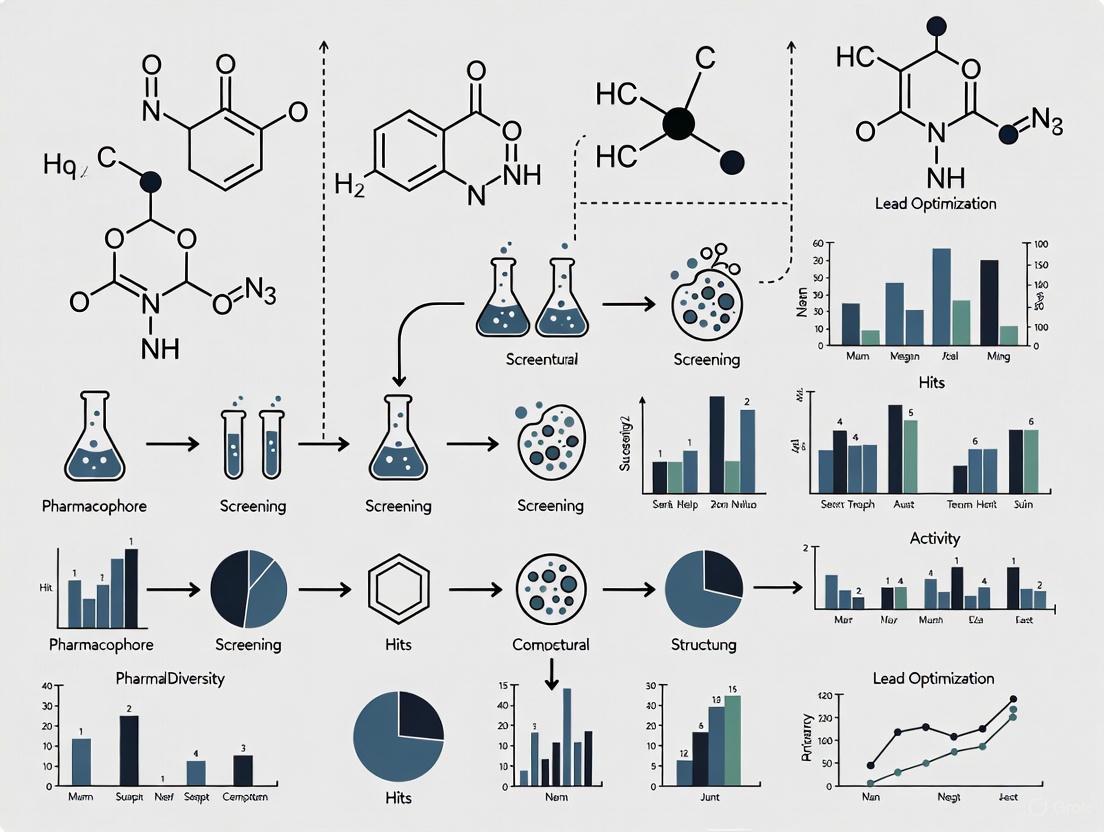

Diagram 1: Pharmacophore-Based Drug Discovery Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pharmacophore-Based Screening

| Item/Software | Function/Description | Application in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software for structure- and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening. | Used to generate and validate the shared features pharmacophore model from training set compounds [5]. |

| ZINC/Pharmer Database | Publicly accessible database of commercially available chemical compounds for virtual screening. | The source library for screening millions of molecules against the generated pharmacophore query [5]. |

| PubChem Database | Public repository of chemical substances and their biological activities. | Used to retrieve 3D conformers (SDF format) of training set molecules [5]. |

| Molecular Docking Suite (e.g., MOE, AutoDock) | Software that predicts the preferred orientation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target protein. | Used to refine virtual screening hits by evaluating binding poses and affinities at the target's active site [11] [5]. |

| MD Simulation Software (e.g., GROMACS) | Software for simulating the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. | Used to assess the stability of the protein-ligand complex and confirm binding interactions through simulated dynamics [11]. |

Case Study: Targeting Salmonella Typhi LpxH

Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi, the causative agent of typhoid fever, is ranked as a high-priority pathogen in the 2024 WHO BPPL due to fluoroquinolone resistance [12]. A recent study demonstrates the successful application of the pharmacophore approach to identify inhibitors of S. Typhi LpxH, a crucial enzyme in the lipid A biosynthesis pathway (Raetz pathway) [11].

Experimental Workflow and Results:

- Target Selection: LpxH, an essential enzyme in the outer membrane biosynthesis of Gram-negative bacteria, was selected.

- Pharmacophore Modeling: A ligand-based pharmacophore model was developed from known LpxH inhibitors.

- Virtual Screening: A natural product library of 852,445 molecules was screened, identifying two lead compounds, 1615 and 1553 [11].

- Validation: MD simulations (100 ns) showed that compound 1615 exhibited the highest stability, with the lowest potential energy and stable hydrogen bonding at the active site [11].

- Drug-Likeness: Toxicity prediction and ADMET analysis showed both compounds had favorable properties, with compound 1615 emerging as the most promising inhibitor [11].

This case study validates pharmacophore-based screening as an efficient strategy for discovering novel leads against WHO priority pathogens.

Diagram 2: LpxH in the Lipid A Biosynthesis Pathway (Raetz Pathway)

The 2024 WHO BPPL provides a clear and urgent directive for the global scientific community, highlighting the critical threat of Gram-negative bacteria and resistant pathogens like Salmonella Typhi [9] [12]. In parallel, innovative computational methods, particularly pharmacophore-based screening, are emerging as powerful and efficient tools to answer this call. By enabling the rapid identification of novel lead compounds against high-priority targets, these strategies can help accelerate the drug discovery pipeline, which is crucial for combating the silent pandemic of AMR [11] [10]. Sustained investment in and application of these innovative approaches are essential to develop the next generation of antimicrobial therapies and safeguard public health.

In the face of the escalating antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis, pharmacophore-based screening has emerged as a cornerstone strategy in modern antimicrobial drug discovery [5]. This approach abstracts molecular interactions into core, functionally defined stereo-electronic features—Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD) and Acceptors (HBA), Hydrophobic Areas (H), and Ionizable Groups—that are critical for a ligand's recognition and binding to its biological target [5] [13]. By focusing on these essential pharmacological features, researchers can efficiently navigate vast chemical spaces to identify novel, bioactive scaffolds, overcoming the limitations of traditional, labor-intensive discovery methods [5]. This document details standardized protocols and application notes for employing these core features within ligand-based pharmacophore models, providing a structured framework for researchers aiming to develop new antimicrobial agents.

Core Feature Definitions and Quantitative Design Rules

The following table summarizes the key stereo-electronic features, their roles in molecular recognition, and associated ideal physicochemical properties for antimicrobial drug design.

Table 1: Core Pharmacophore Features and Their Design Parameters in Antimicrobial Discovery

| Feature | Structural Role & Molecular Interaction | Key Parameters in Antimicrobial Design |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Forms a bond with hydrogen atom; crucial for target specificity and binding affinity [5] [13]. | Presence and 3D spatial arrangement are critical for activity [5]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | Features a hydrogen atom covalently bound to an electronegative atom; key for strong, directional interactions [5] [13]. | Presence and 3D spatial arrangement are critical for activity [5]. |

| Aromatic Ring (Ar) | Provides planar, electron-rich systems for π-π stacking and cation-π interactions [5] [14] [13]. | A weight of 3.0 was assigned in a MAO-B inhibitor model to reflect its importance [14]. |

| Hydrophobic Area (H) | Drives ligand binding via van der Waals forces and desolvation entropy gains; often critical for cell membrane penetration [5] [13]. | A weight of 3.0 was used in a MAO-B inhibitor model [14]. |

| Negatively Ionizable Group (NI) | Can form strong ionic/electrostatic bonds with positively charged residues in the binding site [5]. | A "bare" tetrazole was essential for activity in an AcpS-targeting antibiotic family [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Generation and Screening

This protocol outlines the steps for constructing a validated pharmacophore model and using it for virtual screening, based on established methodologies in antimicrobial research [5] [14] [13].

Software and Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Pharmacophore-Based Screening

| Tool/Reagent Name | Function/Application | Source/Availability |

|---|---|---|

| PubChem Database | Public repository for retrieving 2D/3D structures of training set compounds. | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov [5] [14] |

| LigandScout | Software for advanced pharmacophore model generation and visualization. | https://www.inteligand.com/ligandscout [5] |

| ZINCPharmer/Pharmit | Online platform for pharmacophore-based virtual screening of chemical databases. | http://zincpharmer.csb.pitt.edu [5] [14] |

| Schrödinger Suite (Phase) | Integrated software for comprehensive pharmacophore modeling, QSAR, and ADME/T prediction. | Commercial Software [16] [17] |

| COCONUTS Database | A collection of open natural products for screening novel scaffolds. | https://coconut.naturalproducts.net [16] |

Step-by-Step Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow from data preparation to hit identification.

Training Set Curation and Preparation

- Compound Selection: Identify and select a set of known active compounds against the target of interest. For example, a study on cephalosporins used cephalothin, ceftriaxone, and cefotaxime as a training set [5].

- Data Retrieval: Retrieve the 3D structures of these compounds from databases like PubChem in SDF (Structure Data File) format [5] [14].

- Structure Preparation: Optimize the geometries of the molecules using software like HyperChem or Schrödinger's LigPrep, correcting partial charges and generating relevant tautomers and protonation states at physiological pH (e.g., 7.0 ± 2.0) [16] [14].

Common Feature Pharmacophore Model Generation

- Model Construction: Import the prepared training set into specialized software such as LigandScout or Schrödinger's Phase. Execute the "create Ligand-based pharmacophore" process to generate a 3D Shared Features Pharmacophore (SFP) model [5] [17].

- Feature Identification: The software will identify and map critical chemical features from the aligned active ligands. A robust model should include a combination of HBA, HBD, Hydrophobic (H), and Aromatic Ring (Ar) features, and potentially Negative Ionizable (NI) groups, depending on the ligand set [5] [13].

- Model Selection and Validation: From multiple generated hypotheses, select the best model based on high selectivity and survival scores. Validate the model's robustness using statistical metrics like the Goodness-of-Hit (GH) score (a value of 0.739 indicates a robust model [5]) and enrichment factors from ROC curve analysis [16] [17].

Virtual Screening and Hit Identification

- Database Screening: Use the validated pharmacophore model as a 3D query to screen large chemical databases such as ZINC, COCONUTS, or in-house libraries. This can be performed using platforms like ZINCPharmer or Pharmit [5] [16] [14].

- Screening Parameters: Configure search parameters, typically allowing a maximum of 1-2 missing pharmacophore features and an RMSD tolerance of around 1.5 Å for fitting [14]. Filter initial hits by drug-likeness rules (e.g., molecular weight < 400 g/mol) to prioritize compounds with a higher likelihood of central activity [14].

- Hit Prioritization: Rank the resulting hits by their fit scores (e.g., ranging from 97 to 116 [13]) and RMSD values. Subsequent structure-based docking against the target protein (e.g., Penicillin-binding protein or DNA gyrase) should be used to further prioritize candidates based on docking scores and binding pose analysis [5] [13].

Application Notes & Case Studies in Antimicrobial Research

Case Study 1: Discovery of Novel Cephalosporin Conformers

A study aimed at overcoming bacterial resistance to β-lactam antibiotics successfully developed a ligand-based pharmacophore model from first- and third-generation cephalosporins [5]. The validated model (GH score = 0.739) featured HBA, HBD, Ar, H, and NI sites and was used to screen a drug library. This led to the identification of seven promising compounds, which were then fused with the cephalosporin core via a de novo fragment-based design to create 30 novel synthetic analogs [5] [18] [19]. Among these, Molecule 23 and Molecule 5 demonstrated superior binding affinities to Penicillin-binding protein 1a in molecular docking and dynamics simulations compared to controls, showcasing the power of this approach to design advanced-generation antibiotics [5].

Case Study 2: Identification of a Non-Nucleoside MraY Inhibitor

To target the essential enzyme MraY in Pseudomonas aeruginosa, researchers built a consensus pharmacophore model from eight ligand-bound MraY crystal structures [16]. This model, comprising HBD, HBA, Ar, and H features, was used to screen the COCONUT natural product library. The screening identified CNP0387675, a non-nucleoside inhibitor that demonstrated stable binding to key catalytic residues (ASP-195, ASP-267) in molecular dynamics simulations [16]. This case highlights the utility of multi-template pharmacophore modeling for identifying structurally novel, non-nucleoside inhibitors that circumvent the drug-likeness issues associated with traditional nucleoside analogs.

Key Considerations for Success

- Model Validation: Always rigorously validate the pharmacophore model before proceeding with large-scale screening. A high GH score and good enrichment in ROC analysis are indicators of a reliable model [5] [16].

- Integrate Multiple Techniques: Pharmacophore screening is most effective when integrated with other computational methods, such as molecular docking, QSAR, and ADME/T prediction, to filter and prioritize hits [14] [17].

- Synthetic Feasibility: For de novo designed molecules, use computational retrosynthesis tools (e.g., IBM RXN) to assess and confirm the feasibility of laboratory synthesis for top candidates [5].

In the relentless battle against antimicrobial resistance, pharmacophore modeling has emerged as a pivotal computational strategy for reinvigorating the drug discovery pipeline. A pharmacophore is abstractly defined as the "ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [20]. This approach transcends specific molecular structures, instead focusing on the essential three-dimensional arrangement of chemical features—such as hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and charged groups—required for biological activity [20] [21]. Within antimicrobial research, this abstraction powerfully enables scaffold hopping, the intentional identification of novel core structures (scaffolds) that maintain the crucial interaction pattern of a known active compound but differ in their underlying molecular framework [22].

Scaffold hopping is of paramount importance in antimicrobial development. It offers a strategic path to overcome limitations of existing antibiotics, such as toxicity, metabolic instability, or pre-existing resistance mechanisms, while potentially yielding compounds that circumvent existing patents [22]. By focusing on the fundamental interaction profile rather than a specific chemical structure, pharmacophore models can guide researchers toward new chemical entities that retain efficacy against a bacterial target but are structurally distinct enough to evade common resistance pathways [23]. This review details the practical application of pharmacophore-based methodologies, providing structured protocols and data to accelerate the discovery of novel antimicrobial chemotypes.

Methodological Approaches for Pharmacophore Modeling

The development of a robust pharmacophore model can be achieved through two primary, complementary approaches: structure-based and ligand-based modeling. The choice between them depends on the available experimental data for the antimicrobial target of interest.

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Protocol: Structure-Based Model Development Using a Protein-Ligand Complex

This protocol is applicable when a high-resolution structure of the target protein (e.g., a bacterial enzyme) bound to a ligand is available, often from sources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [20].

- Input Data Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the macromolecular target (e.g., PDB ID: 4DDQ for DNA gyrase subunit A [13] or 4DX5 for the AcrB efflux pump [24]). If the structure is not already complexed with a ligand, prepare the binding site by adding hydrogens, assigning correct protonation states, and performing energy minimization.

- Binding Site Definition: Define the spatial boundaries of the binding pocket. This can be done manually by selecting key residues known to be involved in substrate binding or automatically using built-in cavity detection algorithms in software like Discovery Studio [20].

- Feature Generation: Using the defined binding site, the modeling software (e.g., Discovery Studio, LigandScout) automatically calculates potential pharmacophore features based on the amino acid residues lining the cavity. These features represent possible interaction points (hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contacts, ionic interactions) that a ligand could form [20].

- Model Refinement: The initial, often feature-rich model must be refined. This involves:

- Feature Selection: Retain only the features critical for biological activity, potentially informed by mutagenesis studies or structural knowledge.

- Exclusion Volumes: Add exclusion volumes to represent regions where ligand atoms would experience steric clashes with the protein, thereby improving model specificity [20].

- Tolerance Adjustment: Adjust the radius (tolerance) of each chemical feature to reflect the flexibility of potential interactions.

This approach was successfully employed to target bacterial RNA polymerase by developing a model based on key clamp-helix residues (R270, R278, R281) essential for NusG binding, leading to the identification of a novel class of triaryl antimicrobials [23].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Protocol: Ligand-Based Model Development Using Active Antimicrobials

This method is used when the 3D structure of the target is unknown, but a set of known active ligands is available.

- Training Set Curation: Compile a set of structurally diverse compounds with experimentally confirmed, potent activity against the target (e.g., isolated enzyme or whole-cell MIC assays). It is critical that the activity is directly related to target engagement [20]. For example, a study targeting fluoroquinolone antibiotics used Ciprofloxacin, Delafloxacin, Levofloxacin, and Ofloxacin as the training set [13].

- Conformational Analysis: For each molecule in the training set, generate a representative ensemble of low-energy 3D conformations using tools like LigPrep [24] or iConfGen [25]. This ensures that the bioactive conformation is likely represented.

- Molecular Alignment and Common Feature Identification: Align the multiple conformers of all training set molecules. The software (e.g., Phase) then identifies the common pharmacophore features shared among them and their optimal spatial arrangement [13] [21].

- Hypothesis Generation and Scoring: The algorithm generates multiple Common Pharmacophore Hypotheses (CPHs). Each hypothesis is scored based on how well it aligns the active molecules and its robustness in representing their shared features. The top-ranked hypothesis (e.g., AHHNR.100 in a study identifying efflux pump inhibitors [24]) is selected for further validation.

Model Validation and Virtual Screening

Before application, a pharmacophore model must be rigorously validated.

- Internal Validation: Assess the model's ability to discriminate active from inactive compounds within a test dataset. Use metrics like the Enrichment Factor (EF), which measures the enrichment of active molecules in the virtual hit list compared to random selection, and the Area Under the Curve of the Receiver Operating Characteristic plot (ROC-AUC) [20] [24].

- Decoy Dataset Use: Employ a database of decoy molecules (assumed inactives) with similar 1D properties but different 2D topologies compared to known actives. The Directory of Useful Decoys, Enhanced (DUD-E) is a common resource for this purpose [20]. A recommended ratio is approximately 50 decoys per active molecule [20].

- Virtual Screening: The validated model is used as a 3D query to screen large chemical libraries (e.g., ZINC, FDA-approved drugs). Compounds that map onto all or a defined subset of the model's features are retained as virtual hits [13] [24].

Table 1: Key Metrics for Validating Pharmacophore Model Quality

| Metric | Description | Interpretation and Ideal Value |

|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | Concentration of active compounds in the hit list versus random selection. | Higher is better. Values >10-20 are considered good, indicating a 10-20x enrichment of actives [20]. |

| ROC-AUC | Measures the overall ability of the model to distinguish active from inactive compounds. | 1.0 represents perfect discrimination; 0.5 represents random performance [20] [24]. |

| Yield of Actives | Percentage of active compounds in the virtual hit list. | Higher is better. Hit rates from prospective screens typically range from 5% to 40% [20]. |

| Sensitivity | The model's ability to identify truly active molecules. | High sensitivity means most actives are recovered. |

| Specificity | The model's ability to exclude inactive molecules. | High specificity means few false positives are included [20]. |

The following workflow diagram summarizes the integrated process of model creation and validation.

Case Studies in Antimicrobial Scaffold Hopping

Overcoming Fluoroquinolone Resistance

A ligand-based pharmacophore model was developed using four fluoroquinolone antibiotics (Ciprofloxacin, Delafloxacin, Levofloxacin, Ofloxacin) to identify novel antimicrobial chemotypes [13]. The model captured essential features like hydrophobic areas, hydrogen bond acceptors, donors, and aromatic rings.

- Virtual Screening & Hit Identification: Screening a 160,000-compound library from ZINCPharmer yielded 25 hit compounds. The top hit, ZINC26740199, shared key pharmacophoric features with Ciprofloxacin but possessed a distinct molecular scaffold [13].

- Experimental Validation: Molecular docking confirmed a high-affinity binding mode to the DNA gyrase subunit A (PDB: 4DDQ), with a docking score of -7.4 kcal/mol, comparable to Ciprofloxacin (-7.3 kcal/mol). The compound also demonstrated favorable drug-likeness per Lipinski's Rule [13]. This case demonstrates the power of pharmacophores to enable scaffold hopping from a known antibiotic class.

Targeting Bacterial Efflux Pumps

To combat efflux-mediated colistin resistance in pathogens like K. pneumoniae and M. morganii, a ligand-based pharmacophore model (AHHNR.100) was built using known substrates and inhibitors of the E. coli AcrB efflux pump [24].

- Scaffold Hopping among FDA Drugs: The model was used to screen FDA-approved drugs, leading to the identification of argatroban, an anticoagulant, as a potential efflux pump inhibitor [24].

- Synergistic Activity: In vitro assays showed that argatroban significantly inhibited efflux activity. In combination with colistin, it demonstrated a synergistic effect, causing an 8-log and 2-log reduction in bacterial counts in time-kill assays against K. pneumoniae and M. morganii, respectively [24]. This represents a successful "scaffold hop" to repurpose an existing drug as an antimicrobial adjuvant.

Inhibiting Bacterial Transcription

A structure-based approach targeting the RNA polymerase-clamp helix domain in Streptococcus pneumoniae led to the identification of an initial hit with a linear aminopropanol structure [23]. Researchers then performed scaffold hopping by replacing the linear core with a benzene ring, designing a novel class of triaryl inhibitors [23].

- Potency against Resistant Strains: The resulting lead compounds achieved a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 1 µg/mL against drug-resistant S. pneumoniae, outperforming some marketed antibiotics [23]. This highlights how scaffold hopping driven by pharmacophore principles can directly yield potent antimicrobial candidates with novel chemotypes.

Table 2: Summary of Successful Antimicrobial Scaffold Hopping Campaigns

| Target / Approach | Original Scaffold | Hopped Scaffold | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Gyrase [13] | Fluoroquinolones (e.g., Ciprofloxacin) | ZINC26740199 (novel chemotype) | Identified a novel, drug-like inhibitor with high docking scores comparable to Ciprofloxacin. |

| AcrB Efflux Pump [24] | Known efflux pump inhibitors | Argatroban (FDA-approved drug) | Repurposed argatroban as a synergistic adjuvant that restores colistin susceptibility. |

| RNA Polymerase [23] | Linear aminopropanol | Triaryl benzene | Developed new leads with potent activity (1 µg/mL) against drug-resistant S. pneumoniae. |

Successful implementation of pharmacophore-based scaffold hopping requires a suite of computational and experimental tools. The following table details key resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category / Item | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Software for Pharmacophore Modeling | Discovery Studio [20], LigandScout [20], MOE, Phase (Schrödinger) [24] [25] | Generate structure-based or ligand-based pharmacophore models, perform virtual screening, and analyze results. |

| Conformational Generation | LigPrep (Schrödinger) [24], iConfGen [25] | Generate low-energy, 3D conformers of ligand molecules for model building or screening. |

| Chemical Libraries for Screening | ZINC [13], FDA-approved drug databases [24], ChEMBL [20], DrugBank [20] | Source of compounds for virtual screening to identify novel hits via scaffold hopping. |

| Validation & Decoy Sets | Directory of Useful Decoys, Enhanced (DUD-E) [20] | Provides sets of decoy molecules with similar physicochemical properties to actives but distinct topologies for model validation. |

| Molecular Docking Software | Glide, AutoDock, GOLD | Validate virtual hits by predicting their binding mode and affinity to the target protein (e.g., DNA gyrase [13]). |

| In vitro Assay Materials | Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (CaMHB) [24], Colistin sulfate [24], Triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) [24] | Experimental validation of virtual hits through MIC determination, checkerboard assays for synergism, and time-kill assays. |

Advanced Generative Methods and Future Outlook

The field is rapidly evolving with the integration of artificial intelligence. Generative pre-training transformer (GPT)-based models, such as TransPharmer, are now being employed for de novo molecular generation under pharmacophoric constraints [26]. These models use ligand-based pharmacophore fingerprints as prompts to generate novel molecular structures that satisfy the desired interaction pattern, thereby automating and enhancing the scaffold hopping process [26]. In a prospective case study targeting Polo-like Kinase 1 (PLK1), TransPharmer generated a compound (IIP0943) featuring a novel 4-(benzo[b]thiophen-7-yloxy)pyrimidine scaffold, which exhibited potent nanomolar activity (5.1 nM) [26]. This demonstrates the potential of AI-driven, pharmacophore-informed generative models to accelerate the discovery of structurally novel and bioactive antimicrobial ligands.

The logical progression of these advanced techniques is summarized below.

Building and Applying Pharmacophore Models in Antimicrobial Discovery

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling is a pivotal technique in modern computer-aided drug design, particularly in the urgent field of antimicrobial discovery. This approach leverages the three-dimensional structural information of a biological target, often obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), to identify the essential chemical features a ligand must possess for effective binding [27] [28]. With the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, these methods provide a rational and efficient strategy for identifying new lead compounds, overcoming the limitations and high costs of traditional drug discovery [5]. A pharmacophore model serves as a template for virtual screening, enabling researchers to rapidly search large chemical databases for potential inhibitors [27]. This protocol details the application of structure-based pharmacophore modeling within the context of antimicrobial drug discovery, providing a step-by-step guide and highlighting a relevant case study.

Key Concepts and Definitions

A structure-based pharmacophore model abstracts the critical interactions between a protein target and a bound ligand into a set of chemical features located in 3D space. These features are derived from the analysis of the protein-ligand complex's crystal structure.

Core Pharmacophore Features

The table below summarizes the common chemical features used in pharmacophore model generation.

Table 1: Fundamental Pharmacophore Features and Their Descriptions

| Feature | Symbol | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | HBA | An atom or group that can accept a hydrogen bond (e.g., carbonyl oxygen). |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | HBD | An atom or group that can donate a hydrogen bond (e.g., hydroxyl group). |

| Hydrophobic | H | A non-polar region that interacts with hydrophobic protein pockets. |

| Aromatic Ring | AR | A delocalized pi-system involved in stacking interactions. |

| Positively Ionizable | PI | A group that can carry a positive charge (e.g., protonated amine). |

| Negatively Ionizable | NI | A group that can carry a negative charge (e.g., carboxylate). |

| Exclusion Volume | EV | Defines regions in space that the ligand must avoid for steric reasons. |

The Role of the Protein Data Bank (PDB)

The PDB is an essential resource, providing high-quality, experimentally determined 3D structures of protein targets, often in complex with inhibitors or substrates. These structures are the foundation of the modeling process. For instance, studies have utilized PDB structures like 4DDQ (DNA gyrase), 2V2F (Penicillin-binding protein), and 6R3K (PD-L1) to generate pharmacophore models for virtual screening [27] [13] [5].

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

This protocol outlines the standard workflow for structure-based pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening.

The following diagram illustrates the sequential steps involved in the structure-based pharmacophore modeling pipeline.

Detailed Methodology

Step 1: PDB Structure Selection and Preparation

- Action: Identify and download a relevant protein-ligand complex structure from the PDB (e.g., https://www.rcsb.org/). The structure should have a high resolution (e.g., < 2.5 Å) and a well-defined co-crystallized ligand [28].

- Example: In a study targeting the XIAP protein for cancer therapy, the crystal structure PDB: 5OQW was selected for its high quality and a bound inhibitor with a known IC₅₀ value of 40.0 nM [28].

- Protocol: Prepare the protein structure by removing water molecules (except those involved in crucial H-bonding networks), adding hydrogen atoms, and assigning correct protonation states to amino acid residues using software like LigandScout or Schrodinger's Protein Preparation Wizard.

Step 2: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Model Generation

- Action: Use the prepared protein-ligand complex to generate the pharmacophore model.

- Protocol: In software such as LigandScout, the complex is analyzed to automatically identify and map interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, ionic interactions) between the protein and the bound ligand. These interactions are then translated into pharmacophore features (HBA, HBD, H, etc.). Exclusion volumes are added to represent the protein's steric constraints [27] [28].

- Example Output: A model generated from PDB: 6R3K for a PD-L1 inhibitor contained 8 features: 2 hydrophobic, 2 hydrogen bond acceptors, 2 hydrogen bond donors, one positively charged, and one negatively charged ion center [27].

Step 3: Pharmacophore Model Validation

- Action: Assess the model's ability to distinguish known active compounds from inactive (decoy) molecules.

- Protocol: Use a dataset containing active compounds and decoys. Screen this dataset with the pharmacophore model and generate a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) and the Enrichment Factor (EF) at a early stage (e.g., 1%) are key metrics [27] [28].

- Example: A model for XIAP inhibitors achieved an excellent AUC of 0.98 and an EF1% of 10.0, indicating a high predictive power [28]. Another model for PD-L1 had an AUC of 0.819, confirming its ability to identify active compounds [27].

Step 4: Virtual Screening and Hit Identification

- Action: Use the validated pharmacophore model as a 3D query to screen large chemical databases (e.g., ZINC, CMNPD).

- Protocol: Configure the screening to find molecules that map all or most of the critical chemical features of the pharmacophore model. The "fit value" indicates how well a compound aligns with the model.

- Example: Screening 52,765 marine natural products with a PD-L1 pharmacophore model resulted in only 12 initial hits, demonstrating the high selectivity of the approach [27].

Step 5: Molecular Docking and Binding Affinity Assessment

- Action: Subject the pharmacophore hits to molecular docking into the target's binding site to evaluate their binding geometry and affinity.

- Protocol: Use docking software like AutoDock or GOLD. The binding affinity (in kcal/mol) is calculated for each compound.

- Example: Two marine compounds (37080 and 51320) docked with PD-L1 showed binding affinities of -6.5 kcal/mol and -6.3 kcal/mol, respectively, which were better than the original reference inhibitor (-6.2 kcal/mol) [27].

Step 6: ADMET and Toxicity Prediction

- Action: Filter the top-docked compounds based on predicted Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties.

- Protocol: Use tools like SwissADME or admetSAR to predict key drug-likeness parameters (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) and potential toxicity. This ensures the selected leads have a higher probability of becoming successful drugs [28] [5].

Step 7: Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

- Action: Confirm the stability of the lead compound's binding mode with the target protein.

- Protocol: Run an all-atom MD simulation (e.g., for 100 ns) using software like GROMACS or Desmond. Analyze the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the protein-ligand complex to verify that the ligand remains stably bound [27] [28].

Case Study: Discovery of Novel Cephalosporin Analogues

A 2025 study exemplifies the application of this protocol in antimicrobial discovery to design new cephalosporin analogs combating antibiotic resistance [5].

- Objective: Design new cephalosporin antibiotics effective against resistant bacteria.

- Target: Penicillin-binding protein 1a (PBP1a, PDB ID: 2V2F).

- Methodology:

- A shared-feature pharmacophore (SFP) model was built using known cephalosporins (cephalothin, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime). The model included HBA, HBD, aromatic ring, hydrophobic, and negatively ionizable features.

- The model was validated with a high goodness-of-hit (GH) score of 0.739.

- Virtual screening of a ZINC database identified 7 promising hits.

- These hits were conjugated with the cephalosporin core ring using genetic algorithms and fragment-based design, generating 30 novel synthetic models.

- Molecular docking and MD simulations identified Molecule 23 and Molecule 5 as top candidates with superior binding affinities to PBP1a compared to controls.

- Computational retrosynthesis confirmed the feasibility of synthesizing these candidates in the laboratory [5].

Successful implementation of this protocol relies on several key software tools and databases.

Table 2: Key Resources for Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB PDB | Database | Repository for 3D protein structures used as the starting point for model generation. |

| LigandScout | Software | Generates structure-based pharmacophore models from PDB files and performs virtual screening. |

| ZINC/CMNPD | Database | Commercial databases of purchasable compounds for virtual screening. |

| AutoDock/GOLD | Software | Performs molecular docking to predict binding poses and affinities of hit compounds. |

| SwissADME | Web Tool | Predicts ADMET and drug-likeness properties of candidate molecules. |

| GROMACS | Software | Conducts molecular dynamics simulations to assess complex stability. |

Troubleshooting and Best Practices

- Handling Flexible Targets: For highly flexible proteins like the Liver X Receptor (LXRβ), consider generating multiple pharmacophore models from different crystal structures or using a combined approach of multiple ligand alignments to capture key binding features [29].

- Model Validation is Critical: Never proceed to virtual screening without robust validation using a decoy set. A model with a low AUC score may generate too many false positives [28].

- Iterative Refinement: The initial pharmacophore model can be refined based on the results of docking and MD simulation. Features that do not contribute to stable binding can be removed or modified in subsequent screening rounds.

In antimicrobial drug discovery, the development of novel therapeutics is often hampered by the lack of three-dimensional structural information for bacterial targets. Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling offers a powerful computational alternative that bypasses this limitation by leveraging the chemical features of known active compounds. A pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [30] [31]. This approach is particularly valuable for targeting antimicrobial resistance, as it enables the rapid identification of novel compounds against pathogens where structural data remains elusive [5] [13].

Unlike structure-based methods that require protein 3D structures, ligand-based approaches derive pharmacophore models exclusively from a set of active ligands, making them indispensable for targets with no experimental structural data available [32] [30]. The fundamental principle underpinning this methodology is that compounds sharing similar biological activities against a specific target will possess common chemical features arranged in a conserved three-dimensional orientation [30]. By abstracting these key interaction features, researchers can create efficient queries for virtual screening to identify new chemical entities with potential therapeutic value, thereby accelerating the drug discovery pipeline against resistant pathogens [6].

Theoretical Foundation and Key Concepts

Pharmacophore Feature Types

Pharmacophore models represent ligand-target interactions through abstract chemical features rather than specific atomic structures. The most essential feature types include [30] [13]:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA): Atoms that can accept hydrogen bonds, typically oxygen or nitrogen with lone pairs.

- Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD): Groups that can donate hydrogen bonds, usually featuring hydroxyl, amine, or amide functionalities.

- Hydrophobic Areas (H): Non-polar regions that participate in van der Waals interactions, often represented by aliphatic chains or aromatic rings.

- Aromatic Rings (AR): Planar systems with delocalized π-electrons that enable cation-π and stacking interactions.

- Positively/Negatively Ionizable Groups (PI/NI): Functional groups that can carry formal charges under physiological conditions, facilitating electrostatic interactions.

3D Pharmacophore Representation

Advanced ligand-based pharmacophore methods employ sophisticated representations to capture essential molecular interactions. One novel approach represents pharmacophores as complete graphs where vertices correspond to pharmacophore features and edges represent binned distances between these features in 3D space [32]. This representation enables efficient matching without requiring explicit alignment of compounds or pharmacophores. The system utilizes four-point pharmacophores (quadruplets) as these represent the smallest objects possessing stereoconfiguration in 3D space, with canonical signatures generated for each quadruplet that encode both content-topology and stereoconfiguration information [32].

Experimental Protocols

Compound Selection and Training Set Preparation

The initial and most critical step involves curating a high-quality set of known active compounds with demonstrated efficacy against the antimicrobial target of interest.

Detailed Protocol:

- Data Sourcing: Retrieve structurally diverse active compounds from public databases such as ChEMBL or PubChem, ensuring consistent activity measurements (e.g., IC50, Ki) [32] [5]. For antimicrobial targets, include compounds with documented efficacy against resistant strains.

- Activity Thresholding: Categorize compounds as "active" using target-specific thresholds. For example, in acetylcholinesterase inhibitor studies, compounds with pIC50 ≥ 8 may be classified as active, while those with pIC50 ≤ 6 as inactive [32].

- Chemical Curation: Process structures according to standardized workflows including salt removal, standardization of tautomers, and normalization of functional groups [32].

- Training Set Selection: Employ strategic clustering to ensure representative sampling:

- Apply Butina clustering using 2D pharmacophore fingerprints implemented in RDKit [33].

- For single binding mode assumption: Cluster active and inactive compounds separately, selecting cluster centroids with minimum 5 compounds per cluster [33].

- For multiple binding mode assumption: Cluster active and inactive compounds jointly, randomly selecting 5 active and 5 inactive compounds from each cluster to form multiple training sets [33].

Conformational Analysis and Feature Mapping

Detailed Protocol:

- Stereoisomer Enumeration: Generate all possible stereoisomers for compounds with undefined chiral centers or double bond stereochemistry [33].

- Conformer Generation: For each compound/stereoisomer, generate a representative conformational ensemble using RDKit's distance geometry or similar algorithms [33] [31].

- Generate up to 100 conformers per compound within a 50 kcal/mol energy window after minimization with MMFF94 force field [33].

- This extended energy range ensures inclusion of extended structures for flexible compounds, preventing bias toward folded conformations.

- Pharmacophore Feature Assignment: Label each conformer with pharmacophoric features using SMARTS pattern definitions [32]:

- Define feature types (HBA, HBD, hydrophobic, aromatic, etc.) based on atomic properties and functional groups.

- Note that single atoms or fragments may be assigned multiple feature types simultaneously [32].

Model Generation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow for generating ligand-based pharmacophore models:

Detailed Protocol:

- Initial 4-Point Pharmacophore Generation:

Model Selection Based on Statistical Performance:

- For single training sets (single binding mode assumption): Select pharmacophores with F₀.₅ score ≥ 0.8 to prioritize precision over recall [33].

- For multiple training sets (multiple binding modes): Select models with F₂ score = 1, or if unavailable, recall = 1 [33].

- If符合条件的模型超过100个, select the top 100 performing models.

Iterative Model Expansion:

- Generate 5-point pharmacophores by adding one feature to selected 4-point pharmacophores.

- Recalculate occurrence statistics and select best-performing models for next iteration.

- Continue iteration until models no longer meet selection criteria, then select models from previous iteration as final.

Model Post-Processing:

- Remove overly simplistic models with three or fewer distinct feature coordinates [33].

- Validate selected models on external test sets not used during training.

Virtual Screening Protocol

Detailed Protocol:

- Multi-Step Screening Approach:

- Fingerprint Screening: Use hashed pharmacophore fingerprints as Bloom filters to rapidly eliminate irrelevant compounds [33]. The fingerprint length is typically set to 2048 bits.

- Subgraph Isomorphism Check: Apply VF2 subgraph isomorphism algorithm to verify whether query pharmacophore is a subgraph of candidate molecule pharmacophore [33].

- 3D Hash Comparison: Compare 3D pharmacophore hashes of query model and candidate subgraphs for identical topology and stereoconfiguration [33].

- Performance Metrics Calculation:

- Calculate key metrics to evaluate model performance:

- Recall (True Positive Rate): TP/P, where P is total active compounds in dataset.

- Precision: TP/(TP+FP), where FP is inactive compounds predicted as actives.

- F-score: (1+β²)×(precision×recall)/(β²×precision+recall), with β=0.5 or 2 to weight precision or recall [33].

- Calculate key metrics to evaluate model performance:

Performance Assessment and Quantitative Benchmarks

The table below summarizes typical performance metrics and dataset characteristics from validated ligand-based pharmacophore modeling studies:

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Benchmarks for Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Target System | Active Compounds | Inactive Compounds | Key Features Identified | Validation Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) Inhibitors | 176 (pIC50 ≥ 8) | 1,070 (pIC50 ≤ 6) | HBA, HBD, Hydrophobic | Superior to 2D similarity search | [32] |

| Cytochrome P450 3A4 Inhibitors | 138 (pIC50 ≥ 7) | 548 (pIC50 ≤ 5) | HBA, HBD, Hydrophobic | Successful retrospective validation | [32] |

| Adenosine A2a Receptor Antagonists | 293 (pKi/pKd/pIC50 ≥ 7) | 279 (pKi/pKd/pIC50 ≤ 5) | HBA, HBD, Hydrophobic, Aromatic | Models matched known ligand poses from PDB | [32] |

| Cephalosporin Antibiotics | 3 training compounds | N/A | HBA, HBD, Aromatic, Hydrophobic, Negative Ionizable | GH Score: 0.739; Model Score: 0.9268 | [5] |

| Fluoroquinolone Antibiotics | 4 training compounds | N/A | HBA, HBD, Aromatic, Hydrophobic | 25 hit compounds identified; fit scores 97.85-116 | [13] |

Application Notes for Antimicrobial Discovery

Case Study: Novel Cephalosporin Identification

In a recent application against antimicrobial resistance, researchers developed a Shared Features Pharmacophore (SFP) model using first and third-generation cephalosporins (cephalothin, ceftriaxone, and cefotaxime) as training compounds [5]. The resulting model incorporated hydrogen bond acceptors, hydrogen bond donors, aromatic rings, hydrophobic regions, and negatively ionizable sites, achieving a Goodness-of-Hit (GH) score of 0.739, indicating robust predictive power [5]. Virtual screening of a commercial compound library followed by fragment-based design yielded 30 novel cephalosporin analogs, with molecules 5 and 23 demonstrating superior binding affinity to Penicillin-binding protein 1a compared to controls in molecular docking and MD simulation studies [5].

Case Study: Fluoroquinolone-Based Screening

To combat antibiotic-resistant bacteria, researchers created a ligand-based pharmacophore model using four fluoroquinolone antibiotics (Ciprofloxacin, Delafloxacin, Levofloxacin, and Ofloxacin) [13]. The model featured hydrophobic areas, hydrogen bond acceptors, hydrogen bond donors, and aromatic moieties. Screening of 160,000 compounds from ZINCPharmer identified 25 promising hit compounds with fit scores ranging from 97.85 to 116 and RMSD values between 0.28-0.63 [13]. The top candidate, ZINC26740199, showed significant scaffold similarity to Ciprofloxacin in key pharmacophoric features and achieved a docking score of -7.4 kcal/mol against DNA gyrase subunit A, outperforming the control (-7.3 kcal/mol) [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Key Functionality | Access | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software | Ligand-based & structure-based pharmacophore modeling, virtual screening | Commercial | [5] [34] |

| RDKit | Open-source Cheminformatics | Compound curation, conformer generation, fingerprint calculation | Open Source | [33] [31] |

| ZINCPharmer | Web Server | Pharmacophore-based screening of ZINC database | Free Web Service | [5] [13] |

| Pharmit | Web Server | Interactive pharmacophore screening | Free Web Service | [34] |

| pmapper | Open-source Tool | 3D pharmacophore signature generation and matching | Open Source | [32] |

| ChEMBL Database | Database | Bioactive molecules with drug-like properties, activity data | Free Access | [32] [35] |

| PubChem | Database | Chemical structures and biological activities | Free Access | [5] [6] |

Technical Considerations and Limitations

While ligand-based pharmacophore modeling offers significant advantages for antimicrobial discovery, researchers should be aware of several technical considerations:

Conformational Sampling Adequacy: The quality of generated models heavily depends on comprehensive conformational sampling. Inadequate sampling may miss bioactive conformations, leading to suboptimal models [33]. The recommended approach generates up to 100 conformers per compound within a generous 50 kcal/mol energy window to ensure structural diversity [33].

Active Compound Selection Bias: Model quality correlates directly with the quality and diversity of input active compounds. Training sets should encompass diverse chemical scaffolds with confirmed activity against the target to avoid biased feature selection [32] [33].

Inactive Compound Utilization: Incorporating confirmed inactive compounds significantly enhances model selectivity by eliminating promiscuous pharmacophores that match both active and inactive molecules [32]. The inclusion of inactivity data helps refine model specificity.

Stereochemical Complexity: Proper handling of stereochemistry is essential for model accuracy. Advanced implementations address this by classifying quadruplets into five systems (AAAA, AAAB, AABC, AABB, ABCD) with specific chiral configuration assignments [32].

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling represents a powerful methodology for antimicrobial drug discovery when 3D structural information of targets is unavailable. By abstracting key chemical features from known active compounds, this approach enables efficient virtual screening of large compound libraries to identify novel therapeutic candidates. The protocol detailed in this application note provides a robust framework for implementing this strategy, from careful training set curation through model validation and application. As antimicrobial resistance continues to pose significant global health challenges, these computational approaches offer valuable tools for accelerating the discovery of next-generation antibiotics against evolving bacterial pathogens.

Within antimicrobial drug discovery, the rapid emergence of multi-drug resistant bacterial pathogens presents a critical global health challenge. Computational approaches like pharmacophore-based virtual screening offer a powerful strategy to accelerate the identification of novel antibacterial compounds while reducing costs associated with traditional high-throughput screening [30] [36]. This application note details a standardized workflow for structure-based pharmacophore modeling, framed within the context of discovering new antimicrobial agents targeting essential bacterial enzymes. The protocol guides researchers through protein structure preparation, binding site detection, pharmacophore feature selection, and model validation—critical steps for identifying hits against validated antibacterial targets such as FabD in fatty acid biosynthesis or LpxH/LpxC in lipid A synthesis [11] [36] [37].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential research reagents and computational tools for structure-based pharmacophore modeling.

| Category | Specific Tools/Sources | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Sources | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB), ALPHAFOLD2, Homology Modeling [30] | Provides 3D structural data of target proteins, either experimentally determined or computationally predicted. |

| Binding Site Detection | GRID, LUDI [30] | Identifies potential ligand-binding pockets on protein surfaces using energetic or geometric rules. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Discovery Studio, LigandScout [30] [20] [28] | Generates pharmacophore hypotheses by interpreting protein-ligand interactions or ligand alignments. |

| Screening Databases | ZINC, ChEMBL, DrugBank, Enamine REAL [11] [38] [39] | Provides large collections of commercially available or annotated compounds for virtual screening. |

| Validation Tools | DUD-E (Directory of Useful Decoys, Enhanced) [20] | Generates optimized decoy molecules to validate a model's ability to distinguish active from inactive compounds. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Protein Preparation and Quality Assessment

The initial and most critical step involves obtaining and refining a high-quality 3D structure of the target protein, as this directly influences the accuracy of the subsequent pharmacophore model [30].

- Source Selection: Begin by retrieving an experimental structure of the antimicrobial target (e.g., a bacterial enzyme like RNAP or LpxC) from the RCSB Protein Data Bank. If an experimental structure is unavailable, generate a reliable homology model using tools like SWISS-MODEL or a predicted structure from ALPHAFOLD2 [30] [40].

- Structure Refinement: Prepare the protein structure for computational analysis by:

- Adding hydrogen atoms, which are typically absent in X-ray crystal structures.

- Correcting protonation states of key residues (e.g., Asp, Glu, His) to reflect physiological pH.

- Repairing any missing loops or side-chain atoms.

- Removing non-essential water molecules and co-factors, though functionally relevant waters should be retained [30] [39].

- Quality Evaluation: Conduct a thorough assessment of the structure's stereochemical quality using tools like MolProbity to check for favorable rotamer states, Ramachandran plot outliers, and overall energetic soundness [30].

Binding Site Detection and Characterization

Precise identification of the ligand-binding site is fundamental for creating a biologically relevant pharmacophore model.

- Identification Methods:

- Experimental Data Guidance: If available, use information from site-directed mutagenesis studies or structures of the protein co-crystallized with a native ligand or inhibitor (e.g., rifampicin bound to RNAP) to define the binding site authoritatively [30] [40].

- Computational Prediction: In the absence of experimental data, utilize computational tools such as GRID or LUDI. GRID employs different molecular probes to sample the protein surface and identify regions with energetically favorable interactions, while LUDI uses geometric rules and knowledge-based distributions from known structures to predict binding sites [30].

- Site Characterization: Analyze the amino acid residues lining the binding pocket to understand its chemical environment, including hydrophobic patches, hydrogen-bonding capabilities, and charged regions [28] [37].

Pharmacophore Feature Generation and Selection

This phase involves translating the structural information of the binding site into an abstract set of chemical features required for molecular recognition.

- Feature Mapping: Using software such as LigandScout or Discovery Studio, analyze the binding pocket to generate potential pharmacophore features. These are typically represented as 3D geometric objects (e.g., spheres, vectors) and include [30] [20] [28]:

- Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD)

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA)

- Hydrophobic (H) area

- Positive (PI) / Negative (NI) Ionizable group

- Aromatic (AR) ring

- Feature Selection and Refinement: The initial feature generation often produces an excessive number of potential features. To create a selective and reliable pharmacophore hypothesis, manually curate and select only the features that are essential for bioactivity. This can be achieved by [30]:

- Analyzing protein-ligand co-crystal structures to identify interactions critical for binding energy.

- Consulting sequence alignments to pinpoint evolutionarily conserved residues.

- Incorporating spatial constraints from the receptor by adding exclusion volumes (XVOL). These volumes represent forbidden areas in the binding pocket that account for steric clashes, thereby defining its shape and size [30] [20].

- Model Creation: The final model is a spatial arrangement of the selected essential features and exclusion volumes that defines the functional characteristics a ligand must possess to bind effectively to the target [28].

Pharmacophore Model Validation

Before deploying the model in a virtual screen, it is imperative to validate its ability to distinguish known active compounds from inactive ones.

- Validation Dataset: Compile a test set containing confirmed active compounds and decoy molecules assumed to be inactive. Databases like ChEMBL are sources for actives, while the DUD-E server can generate property-matched decoys [20] [28].

- Performance Metrics: Screen the validation dataset and calculate key metrics to evaluate model performance [20] [28]:

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Measures the model's ability to enrich active compounds in the early phase of the hit list compared to a random selection.

- Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) plot: Summarizes the overall ability of the model to classify actives versus inactives. An AUC value closer to 1.0 indicates excellent predictive power.