Pharmacophore Virtual Screening: Accelerating Lead Identification in Modern Drug Discovery

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening (VS) has evolved into a cornerstone strategy for efficient lead identification in drug discovery.

Pharmacophore Virtual Screening: Accelerating Lead Identification in Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening (VS) has evolved into a cornerstone strategy for efficient lead identification in drug discovery. This article explores the integral role of pharmacophore models, which abstract key steric and electronic features essential for biological activity, in streamlining the hunt for novel therapeutic candidates. We delve into foundational concepts, contrasting ligand-based and structure-based approaches, and examine cutting-edge methodologies powered by artificial intelligence and deep learning. The discussion extends to practical applications across diverse therapeutic areas, including antiviral and anticancer research, alongside critical troubleshooting for model optimization and validation. By synthesizing current trends and real-world case studies, this resource provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for leveraging pharmacophore VS to navigate vast chemical spaces and accelerate the development of bioactive molecules.

Understanding Pharmacophores: The Blueprint for Bioactivity

The pharmacophore concept, a cornerstone of modern medicinal chemistry and drug discovery, provides an abstract framework for understanding molecular recognition. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a pharmacophore is defined as "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [1] [2] [3]. This definition emphasizes that a pharmacophore represents not a specific molecular structure, but rather the essential molecular interaction capacities shared by a group of compounds that recognize the same biological target [1]. Historically, the modern concept was popularized by Lemont Kier in the 1960s and 1970s, though elements of the concept appeared earlier in the work of Schueler and others [1] [2].

The fundamental principle underlying pharmacophore modeling is that ligands sharing common biological activity against a specific target must contain a set of common functional features in a specific three-dimensional arrangement that enables optimal interactions with the target's binding site [2]. These features typically include hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrophobic areas (H), positively and negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI), aromatic rings (AR), and metal-coordinating regions [2] [3]. By abstracting beyond specific atoms or functional groups to focus on these generalized chemical features, pharmacophore models enable the identification of structurally diverse compounds with similar target recognition capabilities, facilitating critical drug discovery processes such as scaffold hopping and virtual screening [1] [4].

Core Features and Model Development

Fundamental Pharmacophore Features

Pharmacophore features represent the key steric and electronic properties that facilitate molecular interactions between a ligand and its biological target. These features are derived from the functional groups present in active ligands and their complementary interaction sites on the target protein. The most significant feature types include [1] [2]:

- Hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) and donors (HBD): These features represent the capacity to form directional hydrogen bonding interactions, crucial for specific molecular recognition.

- Hydrophobic areas (H): These represent regions of the ligand that participate in van der Waals interactions with non-polar protein residues.

- Positively and negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI): These features account for electrostatic interactions, including ionic bonds and charge-assisted hydrogen bonds.

- Aromatic rings (AR): These facilitate π-π stacking and cation-π interactions with complementary protein residues.

- Metal coordinating areas: These represent the ability to interact with metal ions in metalloprotein active sites.

A well-defined pharmacophore model typically incorporates both hydrophobic volumes and hydrogen bond vectors to comprehensively represent the interaction landscape [1]. These features may be located directly on the ligand structure or represented as projected points presumed to be located in the receptor environment [1].

Pharmacophore Model Development Workflow

The process of developing a pharmacophore model follows a systematic workflow that can be applied to both structure-based and ligand-based approaches. The general framework involves several key stages [1]:

- Training Set Selection: A structurally diverse set of molecules is selected, typically including both active and inactive compounds to enable discrimination of bioactivity.

- Conformational Analysis: For each molecule in the training set, a set of low-energy conformations is generated, aiming to include the bioactive conformation.

- Molecular Superimposition: The low-energy conformations of the training molecules are superimposed to identify the best spatial alignment of common functional groups.

- Abstraction: The aligned molecular structures are transformed into an abstract representation, replacing specific functional groups with generalized pharmacophore features.

- Validation: The pharmacophore model is validated for its ability to account for the biological activities of known compounds and predict new actives.

Table 1: Key Stages in Pharmacophore Model Development

| Stage | Key Activities | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Training Set Selection | Curate structurally diverse active/inactive compounds | Representative molecular set |

| Conformational Analysis | Generate low-energy conformers | Bioactive conformation candidates |

| Molecular Superimposition | Align conformations based on common features | Optimal spatial arrangement |

| Abstraction | Replace specific groups with abstract features | Preliminary pharmacophore model |

| Validation | Test model against known actives/inactives | Validated pharmacophore hypothesis |

This systematic approach ensures the resulting pharmacophore model captures the essential molecular features required for biological activity while accommodating structural diversity among active compounds.

Methodological Approaches: Structure-Based vs. Ligand-Based

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

The structure-based approach to pharmacophore modeling relies on the three-dimensional structural information of the biological target, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or homology modeling [2]. When experimental structures are unavailable, computational models generated by tools like AlphaFold2 can provide reliable protein structures for analysis [2]. The workflow begins with critical protein preparation steps, including the assignment of protonation states, addition of hydrogen atoms, and correction of any structural deficiencies [2].

The binding site analysis represents a crucial step in structure-based pharmacophore generation. This can be accomplished using various computational tools: GRID employs different molecular probes to sample protein regions and identify energetically favorable interaction points, while LUDI uses knowledge-based rules derived from protein-ligand complexes to predict potential interaction sites [2]. When a protein-ligand complex structure is available, the pharmacophore features can be derived directly from the observed interactions, resulting in highly accurate models that may include exclusion volumes to represent steric restrictions of the binding pocket [2].

A recent application of structure-based pharmacophore modeling demonstrated its effectiveness in identifying novel FAK1 inhibitors. Researchers used the FAK1-P4N complex (PDB ID: 6YOJ) to generate pharmacophore models, which were then employed to screen the ZINC database [5]. The resulting hits underwent molecular docking, ADMET filtering, and molecular dynamics simulations, leading to the identification of several promising candidates with strong binding affinity and favorable pharmacokinetic profiles [5].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

When the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unavailable, ligand-based pharmacophore modeling provides a powerful alternative approach. This method develops pharmacophore hypotheses based on the structural and physicochemical properties of known active ligands [2] [6]. The fundamental assumption is that compounds sharing common biological activity must contain a set of common features in a specific three-dimensional arrangement that enables target recognition [2].

The ligand-based approach typically begins with the selection of a training set of active compounds, preferably with diverse structural scaffolds but similar biological activity. For example, in a study to identify novel CCR5 inhibitors, researchers selected nine highly active CCR5 inhibitors (IC~50~ values ranging from 0.5 nM to 3.5 nM) as the training set [6]. Conformational analysis is then performed for each compound, followed by molecular alignment to identify the common spatial arrangement of pharmacophoric features.

In the CCR5 inhibitor study, researchers used the Common Feature Generation protocol in Discovery Studio to generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses [6]. The optimal hypothesis (Hypo1) consisted of three hydrophobic features, two hydrogen bond acceptors, and one hydrogen bond donor, which effectively represented the essential features for CCR5 antagonism [6]. This model was subsequently used for virtual screening of chemical databases, leading to the identification of novel hit compounds with potential CCR5 inhibitory activity.

Comparative Performance Evaluation

A benchmark study comparing pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) against docking-based virtual screening (DBVS) across eight diverse protein targets demonstrated the effectiveness of pharmacophore approaches [7]. The study found that in fourteen of sixteen virtual screening experiments, PBVS achieved higher enrichment factors than DBVS [7]. The average hit rates at 2% and 5% of the highest-ranked database compounds were significantly higher for PBVS across all targets, establishing it as a powerful method for active compound retrieval in drug discovery campaigns [7].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

The following detailed protocol outlines the structure-based pharmacophore modeling process as applied in a recent FAK1 inhibitor study [5]:

Protein Structure Preparation

- Retrieve the three-dimensional structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). For example, the FAK1 kinase domain in complex with P4N (PDB ID: 6YOJ) was used in the referenced study.

- Address missing residues or loops using modeling tools such as MODELLER via the Chimera interface. Generate multiple models and select the one with the lowest zDOPE score for subsequent analysis.

- Perform protein preparation steps including hydrogen atom addition, protonation state assignment for residues, and energy minimization.

Binding Site Analysis and Pharmacophore Feature Generation

- Identify the ligand-binding site through analysis of the protein-ligand complex or using binding site detection tools such as GRID or LUDI.

- Upload the protein-ligand complex to pharmacophore modeling software such as Pharmit.

- Identify critical pharmacophoric features involved in ligand-receptor interactions. Pharmit initially detected eight features for the FAK1-P4N complex.

- Generate multiple pharmacophore models (e.g., six models with five or six features each) for subsequent validation.

Pharmacophore Model Validation

- Compile a set of known active compounds and decoys (inactive compounds) from databases such as DUD-E (Directory of Useful Decoys - Enhanced). The FAK1 study used 114 actives and 571 decoys.

- Screen these validation sets against each pharmacophore model and calculate statistical metrics:

- Sensitivity = (Ha / A) × 100 [where Ha is number of active hits, A is total actives]

- Specificity = (Hd / D) × 100 [where Hd is number of decoy hits, D is total decoys]

- Enrichment Factor (EF) and Goodness of Hit (GH)

- Select the model with the highest validation performance for virtual screening.

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Protocol

The following protocol details the ligand-based approach as implemented in a CCR5 inhibitor identification study [6]:

Training Set Compilation

- Collect a set of known active compounds with measured biological activity (e.g., IC~50~ values). The CCR5 study used nine potent inhibitors with IC~50~ values between 0.5 nM and 3.5 nM.

- Obtain 2D structures from databases such as PubChem and draw them using chemical drawing tools like BIOVIA Draw.

- Convert 2D structures to 3D and perform energy minimization using algorithms such as Steepest Descent in molecular modeling software.

Feature Mapping and Pharmacophore Generation

- Use the Feature Mapping protocol in software such as Discovery Studio to identify common chemical features present in the training set compounds.

- Based on feature mapping results, employ the Common Feature Generation protocol to generate multiple pharmacophore hypotheses.

- Evaluate generated hypotheses based on rank score, feature composition, and alignment with training set compounds.

- Select the best hypothesis (e.g., Hypo1 in the CCR5 study with three hydrophobic features, two hydrogen bond acceptors, and one hydrogen bond donor) for virtual screening.

Pharmacophore Validation

- Validate the selected pharmacophore model using methods such as the Güner-Henry method to ensure its ability to distinguish active from inactive compounds.

- Test the model against a test set of known actives and inactives to calculate enrichment factors and other validation metrics.

Applications in Virtual Screening and Lead Identification

Virtual Screening Workflows

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening has emerged as a powerful strategy for identifying novel bioactive compounds from large chemical databases. The general workflow integrates pharmacophore screening with complementary computational techniques [5] [6]:

Database Preparation: Compile and prepare large chemical databases (e.g., ZINC, Asinex, Specs) for screening, including format conversion, tautomer generation, and energy minimization.

Pharmacophore Screening: Use the validated pharmacophore model as a 3D query to screen the chemical database and retrieve compounds that match the essential feature arrangement.

Molecular Docking: Subject the pharmacophore-matched compounds to molecular docking studies using programs such as AutoDock Vina, SwissDock, or Glide to evaluate binding modes and affinities.

ADMET Filtering: Evaluate the top-ranking compounds for acceptable pharmacokinetic properties and low predicted toxicity using tools like SwissADME or admetSAR.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Perform MD simulations (e.g., using GROMACS) on selected protein-ligand complexes to assess stability and interaction persistence over time.

Binding Free Energy Calculations: Apply methods such as MM/PBSA (Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area) to calculate binding free energies and identify the most promising candidates.

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Pharmacophore Applications

| Application Area | Software Tools | Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Catalyst/Discovery Studio, LigandScout, Phase, MOE | Model generation, 3D-QSAR, virtual screening |

| Molecular Docking | AutoDock Vina, GOLD, Glide, SwissDock | Binding pose prediction, scoring |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Complex stability, dynamic behavior |

| Binding Energy Calculations | MM/PBSA, MM/GBSA | Free energy estimation |

| ADMET Prediction | SwissADME, admetSAR, Molsoft | Pharmacokinetic and toxicity profiling |

Case Study: Identification of Novel FAK1 Inhibitors

A comprehensive study demonstrating the application of pharmacophore-based virtual screening led to the identification of novel FAK1 inhibitors with potential anticancer activity [5]. The researchers developed a structure-based pharmacophore model from the FAK1-P4N complex, which they validated using statistical metrics. This model was used to screen the ZINC database, followed by molecular docking that identified seventeen compounds with acceptable binding properties and pharmacokinetic profiles [5]. Further refinement through more precise docking and MD simulations narrowed the candidates to four promising leads, with ZINC23845603 emerging as the top candidate due to its strong binding energy, stable complex behavior, and interaction features similar to the known ligand P4N [5]. This case demonstrates how pharmacophore-based screening efficiently narrows large chemical databases to a manageable number of high-quality leads for experimental validation.

Case Study: Discovery of CCR5 Antagonists

In another application, researchers employed ligand-based pharmacophore modeling to identify novel CCR5 antagonists for HIV therapy [6]. After developing and validating a pharmacophore model from known CCR5 inhibitors, the team performed virtual screening of several chemical libraries. The identified hits underwent molecular docking studies, MD simulations, and binding free energy calculations, revealing that two hits (Hit1 and Hit2) demonstrated better binding energy than the FDA-approved drug Maraviroc and formed stable interactions with key CCR5 residues throughout 100 ns MD simulations [6]. This success illustrates the power of pharmacophore approaches to identify promising drug candidates, particularly for targets like CCR5 where structural information may be limited.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pharmacophore Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of experimental protein structures for structure-based modeling |

| Chemical Databases | ZINC, PubChem, Asinex, Specs, InterBioScreen | Libraries of compounds for virtual screening |

| Active/Decoy Compound Sets | DUD-E (Directory of Useful Decoys - Enhanced) | Validated sets of active and decoy compounds for pharmacophore validation |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Catalyst/Discovery Studio, LigandScout, Phase, MOE, Pharmit | Generation, visualization, and application of pharmacophore models |

| Molecular Docking Tools | AutoDock Vina, GOLD, Glide, SwissDock | Prediction of ligand binding modes and affinity scoring |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Simulation of protein-ligand complex stability and dynamics |

| Binding Free Energy Calculations | MM/PBSA, MM/GBSA | Quantification of protein-ligand binding affinities |

| ADMET Prediction Platforms | SwissADME, admetSAR, Molsoft | Prediction of pharmacokinetic properties and toxicity profiles |

Advanced Integration and Future Perspectives

Integration with Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are revolutionizing pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening approaches. AI-driven molecular representation methods, including graph neural networks (GNNs), variational autoencoders (VAEs), and transformer models, enable more sophisticated characterization of molecular structures and properties [4]. These approaches learn continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings directly from large datasets, capturing both local and global molecular features that may be overlooked by traditional methods [4].

Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship (QPhAR) methods represent another significant advancement, combining traditional pharmacophore modeling with machine learning to create predictive models for activity optimization [8]. This integration enables more accurate activity prediction and facilitates lead optimization in drug discovery projects. The synergy between AI and pharmacophore modeling is particularly valuable for scaffold hopping, where the goal is to identify novel core structures that maintain biological activity while improving other properties [4]. Modern AI methods can capture nuanced structural relationships that enable identification of scaffolds previously difficult to discover using traditional similarity-based approaches [4].

Synergy with Molecular Dynamics Simulations

The integration of pharmacophore modeling with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations has emerged as a powerful strategy for addressing the dynamic nature of protein-ligand interactions. While static pharmacophore models provide valuable insights, they may overlook conformational flexibility and induced fit effects. MD simulations complement pharmacophore approaches by providing temporal dimension to the analysis of binding interactions [5] [6].

In the FAK1 inhibitor study, researchers used MD simulations to evaluate the stability of four potential inhibitor complexes over time, monitoring root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) and specific protein-ligand interactions [5]. This approach confirmed that the top candidate (ZINC23845603) maintained stable binding interactions throughout the simulation period, validating the initial pharmacophore-based predictions [5]. Similarly, in the CCR5 antagonist study, 100 ns MD simulations demonstrated that the identified hits maintained stable interactions with key residues, providing confidence in their potential as drug candidates [6]. These case studies highlight how MD simulations can confirm the stability and persistence of pharmacophore-identified interactions under dynamic conditions.

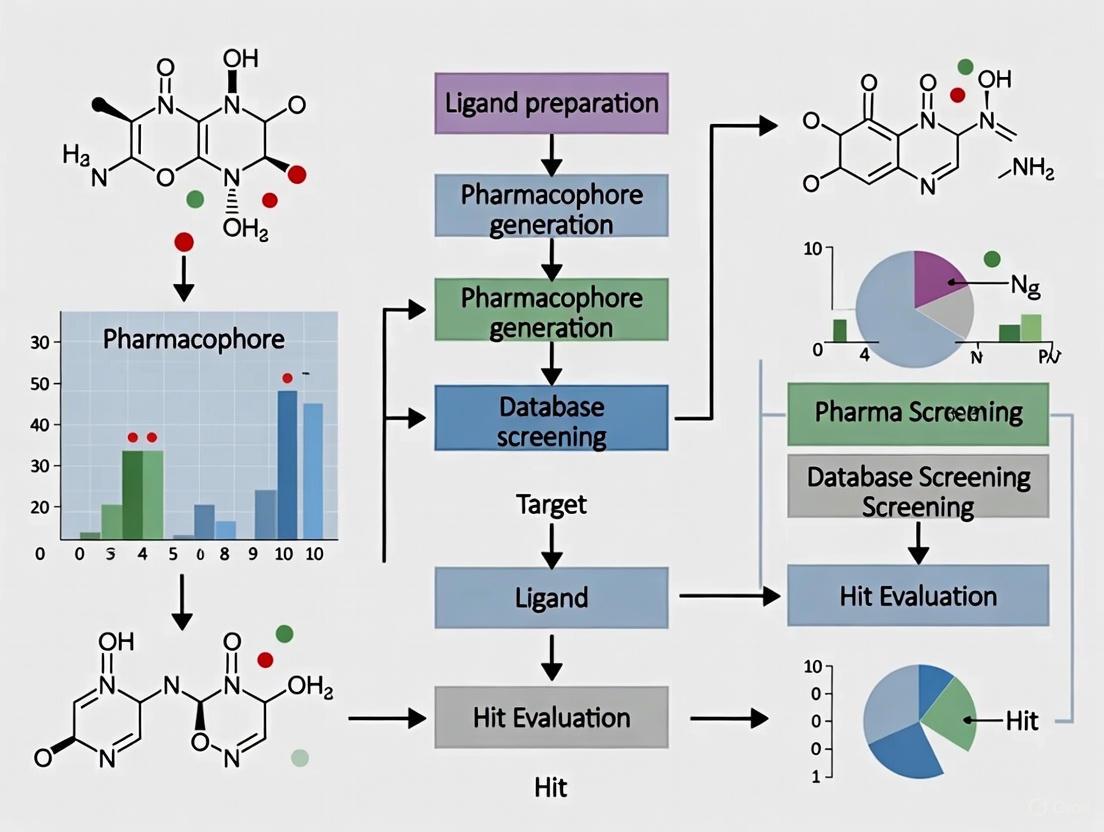

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Integrated Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening Workflow. This flowchart illustrates the two primary approaches (structure-based and ligand-based) and their convergence into a common virtual screening and validation pipeline.

The pharmacophore concept has evolved from an abstract theoretical framework to a practical and indispensable tool in modern drug discovery. By distilling the essential steric and electronic features required for molecular recognition, pharmacophore models provide a powerful approach for navigating complex chemical spaces and identifying novel bioactive compounds. The integration of pharmacophore-based virtual screening with complementary computational methods—including molecular docking, MD simulations, and binding free energy calculations—creates a robust pipeline for lead identification and optimization. As AI and machine learning continue to advance, their synergy with traditional pharmacophore approaches promises to further enhance the efficiency and success of drug discovery efforts, particularly in challenging areas such as scaffold hopping and polypharmacology. Through continued methodological refinements and integrative applications, pharmacophore modeling remains a cornerstone of computational drug design, enabling researchers to translate abstract molecular features into concrete therapeutic candidates.

Pharmacophore modeling is a foundational concept in computer-aided drug design (CADD), defined by IUPAC as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [2]. This approach abstracts molecular interactions into core chemical features—such as hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA), hydrogen bond donors (HBD), hydrophobic areas (H), and ionizable groups—thereby enabling the identification of bioactive compounds regardless of their underlying scaffold [2]. Within modern virtual screening (VS) workflows for lead identification, pharmacophore approaches provide an efficient method for prioritizing candidates from extensive chemical libraries, significantly reducing time and costs compared to experimental screening alone [2].

The two primary methodologies for pharmacophore model development are ligand-based and structure-based modeling, each with distinct requirements, workflows, and applications. This review provides a detailed technical comparison of these approaches, focusing on their implementation, performance, and strategic role in lead discovery research.

Methodological Foundations and Workflows

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling is applied when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unknown, but a set of known active ligands is available. This approach operates on the principle that compounds sharing common biological activity against a specific target must possess essential chemical features arranged in a conserved spatial orientation [2].

Experimental Protocol:

- Training Set Compilation: Curate a structurally diverse set of known active compounds, ideally with associated quantitative activity data (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki) [9].

- Conformational Sampling: Generate a representative set of low-energy conformations for each ligand in the training set. This is typically achieved using algorithms such as Monte Carlo methods or systematic torsional sampling [9].

- Molecular Superimposition: Identify the optimal alignment of the training compounds that maximizes the spatial overlap of their common chemical functionalities. Common software tools include DISCO, GASP, or PHASE [9].

- Feature Abstraction and Hypothesis Generation: From the superimposed consensus, extract the common steric and electronic features critical for biological activity to form one or more pharmacophore hypotheses [2].

- Model Validation: Validate the generated model using a test set of active and inactive/decoy compounds. Metrics such as the Enrichment Factor (EF) and the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) are calculated to quantify the model's ability to distinguish active from inactive molecules [10]. For example, a validated model for XIAP protein inhibitors achieved an EF1% of 10.0 and an AUC of 0.98, demonstrating excellent predictive power [10].

The following diagram illustrates this multi-step workflow:

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling requires a three-dimensional structure of the target macromolecule, which can be obtained from experimental methods (X-ray crystallography, NMR) or computational modeling (e.g., homology modeling with tools like AlphaFold2) [2] [11]. The approach involves analyzing the target's binding site to identify key interaction points that a ligand must satisfy.

Experimental Protocol:

- Protein Structure Preparation: Obtain and refine the 3D structure from the PDB or via homology modeling. Critical steps include adding hydrogen atoms, assigning correct protonation states, and repairing missing residues [2] [11].

- Binding Site Characterization: Identify and delineate the ligand-binding pocket. This can be done manually based on co-crystallized ligand location or using automated tools like GRID or LUDI, which probe the site with different functional groups to map favorable interaction energies [2] [11].

- Interaction Feature Mapping: Analyze the binding site to pinpoint locations suitable for key interactions (HBA, HBD, hydrophobic contacts, ionic interactions). In advanced protocols, tools like Multiple Copy Simultaneous Search (MCSS) place functional group fragments into the site, which are then energy-minimized to identify optimal positions and orientations [11].

- Model Assembly and Refinement: Select the most critical interaction points from the mapping to construct the pharmacophore hypothesis. Exclusion volumes (XVOL) are often added to represent steric constraints from the protein, preventing clashes [2] [11].

- Performance Evaluation: Similar to ligand-based models, the final structure-based model is evaluated by screening a database of known actives and decoys, with performance quantified by EF and GH (goodness-of-hit) scores [11].

The workflow for the structure-based approach is summarized below:

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each pharmacophore modeling strategy.

Table 1: Comparative overview of ligand-based and structure-based pharmacophore modeling approaches

| Aspect | Ligand-Based Pharmacophore | Structure-Based Pharmacophore |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Input Data | Set of known active ligands [2] | 3D structure of the target protein (experimental or modeled) [2] |

| Key Requirements | Multiple, structurally diverse active compounds; biological activity data is beneficial [9] | High-quality protein structure; binding site definition [2] [11] |

| Fundamental Principle | Extracts common chemical features from a superposition of active ligands [2] | Derives interaction features from the analysis of the protein's binding site [2] |

| Ideal Application Context | Targets with no known 3D structure but multiple known ligands (e.g., GPCRs) [9] | Targets with available 3D structure, including orphan targets with no known ligands [11] |

| Major Advantages | - Does not require protein structure- Directly captures ligand-derived activity patterns- Excellent for scaffold hopping [2] [9] | - Can be applied without known ligands- Provides mechanistic insight into binding- Incorporates exclusion volumes (XVOL) for specificity [2] [11] |

| Inherent Limitations | - Quality depends on diversity and quality of the training set- Cannot discover novel binding modes- Lacks direct structural context of the target [2] [9] | - Quality is highly dependent on the input protein structure- May generate an overabundance of features requiring pruning- Computationally more intensive [2] [11] |

Performance and Validation in Virtual Screening

Quantitative validation is critical for establishing the utility of a pharmacophore model in a virtual screening campaign. Key metrics include the Enrichment Factor (EF), which measures how much better the model is at identifying actives compared to random selection, and the Goodness-of-Hit (GH) score, which balances the yield of actives with the false-negative rate [11].

Table 2: Representative virtual screening performance of pharmacophore models

| Target Protein | Modeling Approach | Performance Metrics | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| XIAP [10] | Structure-Based | EF1% = 10.0; AUC = 0.98 | Model successfully identified natural compounds with potential anti-cancer activity, validated by molecular dynamics. |

| Class A GPCRs (13 targets) [11] | Structure-Based (Score-based) | High EF and GH scores; Logistic regression classifier PPV: 0.88 (experimental structures), 0.76 (modeled structures) | A machine learning "cluster-then-predict" workflow effectively selected high-performing pharmacophore models, even for homology models. |

| PARP1, USP1, ATM [12] | Structure-Based (CMD-GEN framework) | Sampled pharmacophores accurately mirrored binding modes of known inhibitors (e.g., Isocarbostyril core in PARP1). | The framework enabled rapid sampling of pharmacophore combinations for selective inhibitor design, confirmed by wet-lab validation for PARP1/2. |

Table 3: Key software and data resources for pharmacophore-based research

| Tool / Resource Name | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| LigandScout [10] | Creates structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore models from protein-ligand complexes or ligand sets, and performs virtual screening. | Used to generate and validate the structure-based model for XIAP, identifying key hydrophobic, HBD, and HBA features [10]. |

| MCSS (Multiple Copy Simultaneous Search) [11] | Places numerous copies of functional group fragments into a protein's binding site to map optimal interaction points for pharmacophore feature generation. | Core to the score-based structure-based pharmacophore modeling workflow for GPCRs [11]. |

| PHASE [9] [13] | Performs ligand-based pharmacophore model development, 3D-QSAR analysis, and database screening. | Allows for the development of quantitative pharmacophore models and pharmacophore field-based QSAR [13]. |

| HypoGen/Discovery Studio [13] | Algorithm and software for generating quantitative pharmacophore models from a set of active and inactive training molecules. | One of the few commercially available tools for building directly quantitative models from pharmacophore features [13]. |

| ZINC Database [10] | A curated collection of commercially available chemical compounds prepared for virtual screening (e.g., in 3D formats). | Sourced for natural compound libraries in the virtual screening for novel XIAP antagonists [10]. |

| DUDe (Database of Useful Decoys) [10] | Provides benchmark decoy sets for specific targets to rigorously validate virtual screening methods and avoid false positives. | Used to validate the XIAP pharmacophore model with 10 active compounds and 5199 decoys [10]. |

Emerging Trends and Advanced Applications

The field of pharmacophore modeling is being revitalized by integration with artificial intelligence and deep learning, enhancing its predictive power and application scope.

- Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship (QPHAR): This novel method constructs robust quantitative SAR models directly from pharmacophore features, demonstrating an average RMSE of 0.62 in cross-validation on over 250 diverse datasets. Its low requirement for training set size (as few as 15-20 samples) makes it particularly viable for lead optimization [13].

- Pharmacophore-Guided Deep Learning for Molecular Generation: Models like PGMG (Pharmacophore-Guided Molecule Generation) use pharmacophore hypotheses as input to generate novel, drug-like molecules with high validity, uniqueness, and novelty [14]. This approach provides a flexible strategy for de novo design in both ligand-based and structure-based contexts.

- Integrated Frameworks for Selective Inhibitor Design: Advanced frameworks such as CMD-GEN combine coarse-grained pharmacophore sampling from diffusion models with hierarchical molecular generation. This addresses challenges of molecular stability and drug-likeness, showing promise for designing selective inhibitors, as validated for PARP1/2 [12].

- Machine Learning for Model Selection: The "cluster-then-predict" workflow employing K-means clustering and logistic regression can classify and select high-enrichment structure-based pharmacophore models with high positive predictive value (0.82 true positive rate), a crucial advancement for applying these models to targets with no known ligands [11].

Ligand-based and structure-based pharmacophore modeling are powerful, complementary strategies within the virtual screening toolkit for lead identification. The choice between them is dictated primarily by the available structural and ligand data. The convergence of classic pharmacophore concepts with modern AI and machine learning is creating a new generation of intelligent tools. These tools, including QPHAR and PGMG, are enhancing the quantitative prediction, de novo design, and overall effectiveness of pharmacophore approaches, solidifying their critical role in accelerating rational drug discovery.

In the realm of computer-aided drug design, a pharmacophore is defined as the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response [2] [15]. This abstract representation captures the essential three-dimensional arrangement of molecular functionalities—such as hydrogen-bond donors and acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and charged groups—shared by ligands that exhibit similar biological activity against a given target [15]. Unlike a molecular scaffold, which refers to a specific core structure, a pharmacophore emphasizes the spatial arrangement and types of interaction features rather than the underlying atomic connectivity [15]. This conceptual framework serves as a foundational tool for understanding ligand-target recognition and provides the structural basis for virtual screening (VS) campaigns aimed at identifying novel lead compounds from vast chemical libraries [2] [16]. By distilling the complex phenomenon of binding into a set of critical features, pharmacophore models bridge the gap between chemistry and biology, facilitating the rational design of therapeutics in a time- and cost-efficient manner [2] [17].

Defining the Core Pharmacophoric Features

The predictive power of a pharmacophore model hinges on the accurate identification and spatial representation of key chemical features. These features are the functional units that mediate non-covalent interactions with the biological target. The most critical features, which form the cornerstone of most pharmacophore models, are hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and ionic groups [16] [18].

Table 1: Core Pharmacophoric Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature | Atomic/Groups Involved | Interaction Type | Representation in Model | Tolerance Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | OH, NH, (less commonly SH) [16] | Directional electrostatic interaction with acceptor [18] | Vector or sphere; often a "torus" for sp³ hybridized atoms [18] | Distance: ~1.5–2.5 Å to acceptor; Angle: ~30° deviation for sp³ [15] [18] |

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Carbonyl O, ether O, aromatic N [16] | Directional electrostatic interaction with donor [18] | Vector or sphere; often a "cone" for sp² hybridized atoms [18] | Distance: ~1.5–2.5 Å to donor; Angle: ~50° deviation for sp² [15] [18] |

| Hydrophobic Region (H) | Alkyl chains, aromatic ring systems [15] [16] | van der Waals forces, entropic gain from desolvation [15] | Sphere or volume [15] | Spherical centroid with radius typically 1–2 Å [15] |

| Positive Ionizable (PI) | Protonated amines, quaternary ammonium [16] | electrostatic attraction, salt bridges [15] | Sphere with defined charge [19] | pKa-based (e.g., basic groups with pKa 7–10 at pH 7.4) [15] |

| Negative Ionizable (NI) | Carboxylates, phosphates, sulfonates [16] | electrostatic attraction, salt bridges [15] | Sphere with defined charge [19] | pKa-based (e.g., acidic groups with pKa 3–5 at pH 7.4) [15] |

Hydrogen Bond Donors and Acceptors

Hydrogen bond donors are functional groups capable of donating a hydrogen atom to form a hydrogen bond with a complementary acceptor group. These typically include amino (NH, NH₂), hydroxyl (OH), and, less commonly, thiol (SH) groups [16]. Hydrogen bond acceptors, conversely, are atoms or groups with a lone pair of electrons that can accept a hydrogen bond from a donor. Common examples are carbonyl oxygen, ether oxygen, and aromatic nitrogen atoms [16]. These interactions are highly directional and play a crucial role in determining the specificity and affinity of a ligand for its target [18]. In pharmacophore models, they are represented as vectors or spheres with specific angular tolerances. For instance, interactions at sp² hybridized atoms are often depicted as a cone with a default angular range of 50 degrees, while those at sp³ atoms are represented by a torus with a ~34-degree angular range to account for flexibility [18].

Hydrophobic Regions

Hydrophobic regions are non-polar areas of a molecule that tend to avoid interaction with water and prefer to associate with other non-polar surfaces. These regions often consist of alkyl chains or aromatic rings (e.g., benzene, pyridine) and contribute significantly to the overall lipophilicity of a molecule [16]. The interaction is driven by the desolvation of the non-polar surfaces and the resulting entropic gain and van der Waals contacts, which collectively stabilize the ligand in the binding pocket [15]. In a model, these features are abstracted as spherical centroids or volumes, often with a radius of 4–6 Å, representing the space occupied by the hydrophobic group [15].

Ionic Groups

Ionic groups introduce formal charges that enable strong, long-range electrostatic interactions, such as salt bridges. Positive ionizable features include protonated amines (e.g., in ammonium groups) and are modeled based on their protonation state at physiological pH (typically, basic groups with pKa 7–10 remain protonated) [15] [16]. Negative ionizable features include carboxylates, phosphates, and sulfonates, which are deprotonated and negatively charged at physiological pH (typically, acidic groups with pKa 3–5 are deprotonated) [15] [16]. The energetic contribution of these charged groups to binding can be substantial, and their representation in a pharmacophore model often includes tolerances based on pKa to ensure the correct ionization state is considered [15].

Diagram 1: Workflow for developing and applying a pharmacophore model, showing the decision point between ligand-based and structure-based approaches.

Experimental Protocols for Pharmacophore Model Development

The development of a robust pharmacophore model is a multi-step process that relies heavily on the quality of input data and the rigor of computational protocols. The two primary methodologies are structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, with a growing trend of integrating both for enhanced reliability [2] [16] [18].

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This protocol is employed when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein (often with a bound ligand) is available from sources like the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB), or through computational techniques like homology modeling (e.g., AlphaFold2) [2].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Structure-Based Modeling

| Item/Tool | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids [2]. | Critical first step for obtaining a reliable starting structure. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) | Simulates physical movements of atoms and molecules over time [18]. | Accounts for protein flexibility; refines static models. |

| FTMap / E-FTMap Server | Computationally maps binding "hot spots" using small molecular probes [20]. | Identifies key interaction regions in a binding site. |

| Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation Software (e.g., MOE, LigandScout) | Automatically extracts interaction features from a protein-ligand complex [2] [19]. | Generates initial pharmacophore hypotheses. |

Step 1: Protein Structure Preparation. The retrieved 3D structure (e.g., from PDB) is prepared by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning protonation states to residues (like Asp, Glu, His) at physiological pH, and correcting for any missing atoms or residues. This step is crucial as the quality of the input structure directly dictates the quality of the final pharmacophore model. Energy minimization may be performed to relieve steric clashes [2].

Step 2: Binding Site Identification and Analysis. The ligand-binding site is identified, either from the coordinates of a co-crystallized ligand or using binding site detection programs like GRID or LUDI. GRID, for instance, uses different functional groups as probes to sample the protein surface on a grid, identifying points with energetically favorable interactions and generating molecular interaction fields [2].

Step 3: Pharmacophore Feature Generation and Selection. The protein-ligand complex is analyzed to map key interaction points (e.g., a hydrogen bond between a ligand carbonyl and a backbone NH in the protein). Initially, many features are generated. The model is refined by selecting only those features that are essential for bioactivity, such as removing features that do not strongly contribute to binding energy or preserving residues with key functions from mutagenesis studies. Exclusion volumes (XVOL) are often added to represent regions occupied by the protein, preventing steric clashes in screened molecules [2] [19].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This approach is used when the 3D structure of the target is unknown but a set of known active ligands is available. It operates on the principle that these active molecules share a common spatial arrangement of functional features responsible for their activity [2] [21].

Step 1: Ligand Selection and Conformational Analysis. A training set of structurally diverse but biologically active compounds is assembled. Conformational analysis is then performed for each ligand using methods like systematic search or molecular dynamics to generate an ensemble of low-energy conformers. This step is critical because the pharmacophore must be based on the bioactive conformation, which may not be the global minimum [15] [16].

Step 2: Molecular Alignment and Superimposition. The multiple low-energy conformers of the active ligands are aligned in 3D space to identify the maximal common substructure and overlapping chemical features. This can be achieved through rigid-body alignment, flexible alignment, or feature-based alignment algorithms. The principle of superposition is the cornerstone of this approach, aiming to find the best overlap of pharmacophoric points like hydrogen-bond donors and hydrophobic centroids [15] [21].

Step 3: Pharmacophore Hypothesis Generation and Validation. Common chemical features shared by the aligned ligands are identified and used to generate a pharmacophore hypothesis. This involves selecting the most relevant features (e.g., 3 hydrophobic, 2 HBA, 1 HBD) and defining their spatial constraints (distances, angles) [21]. The model is then validated using a set of known active and inactive compounds. Statistical metrics like the Güner-Henry (GH) score and Enrichment Factor (EF) are calculated to evaluate its ability to discriminate actives from inactives. A good model should have a high GH score and EF, indicating its predictive power for virtual screening [21].

Diagram 2: Data flow for structure-based (top) and ligand-based (bottom) pharmacophore modeling methodologies.

Application in Virtual Screening for Lead Identification

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening represents one of the most impactful applications of this technology in modern drug discovery. A validated pharmacophore model serves as a 3D query to efficiently search large chemical databases (e.g., ZINC, PubChem) and identify compounds that match the essential steric and electronic features, thereby predicting potential biological activity [2] [17].

The process involves screening millions of compounds in silico, drastically reducing the number of candidates that proceed to costly and time-consuming experimental testing [16] [17]. This approach is particularly powerful for scaffold hopping—the identification of novel core structures (scaffolds) that present the required pharmacophoric features in the correct spatial orientation but are chemically distinct from known actives. This helps in discovering new chemical entities and navigating around existing patents [4] [16]. Tools like the publicly accessible pharmit web server facilitate this process by allowing researchers to search databases using pharmacophore queries, with additional filters for drug-like properties (e.g., molecular weight, logP, rotatable bonds) [19].

A compelling case study demonstrating this application is the identification of novel Cysteine-Cysteine Chemokine Receptor 5 (CCR5) inhibitors to block HIV cellular entry [21]. Researchers developed a ligand-based common feature pharmacophore model (Hypo1) from a set of nine known active CCR5 inhibitors. The model consisted of three hydrophobic features, two hydrogen bond acceptors, and one hydrogen bond donor. After successful validation (GH score = 0.79, indicating a good model), it was used as a 3D query for the virtual screening of drug-like databases from Asinex, Specs, and other libraries. The resulting hits were further refined by molecular docking, dynamics simulations, and binding free energy calculations, leading to the identification of two potential leads (Hit1 and Hit2) that showed better binding energy than the FDA-approved drug Maraviroc and formed stable interactions with key residues [21]. This integrated workflow underscores the utility of pharmacophore-based VS as a primary engine for initiating lead identification campaigns.

The core pharmacophoric features—hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and ionic groups—constitute the fundamental language of molecular recognition. Their precise definition and spatial arrangement within a pharmacophore model provide an powerful abstract framework that transcends specific chemical structures. As demonstrated, these models are indispensable tools in the drug discovery pipeline, particularly in structuring and accelerating virtual screening for lead identification. The rigorous experimental protocols for model development, whether structure-based or ligand-based, ensure the derivation of robust and predictive hypotheses. When coupled with other computational techniques like molecular docking and dynamics simulations, pharmacophore-based virtual screening forms a powerful, integrated strategy for navigating the vastness of chemical space and identifying novel, promising leads for further development, thereby solidifying its critical role in modern rational drug design.

The Synergy Between Lead Compounds and Pharmacophore Models in Drug Design

In the landscape of computer-aided drug design (CADD), the integration of lead compounds and pharmacophore models represents a cornerstone strategy for efficient lead identification and optimization [2]. Pharmacophores provide an abstract representation of the steric and electronic features essential for a molecule to interact with a biological target and trigger its pharmacological response [2]. This technical guide delves into the synergistic relationship between known lead compounds and the pharmacophore models derived from them, framing this interaction within the context of virtual screening (VS) for lead identification research. We explore foundational methodologies, advanced quantitative and AI-driven approaches, and provide detailed protocols and resources to empower drug development professionals.

Pharmacophore Fundamentals and Modeling Approaches

A pharmacophore is defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [2]. These features are represented geometrically as points, spheres, planes, and vectors in three-dimensional space, abstracting key molecular interactions from specific atomic structures [2].

The core pharmacophore feature types include [2]:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA) and Donors (HBD)

- Hydrophobic areas (H)

- Positively and Negatively Ionizable groups (PI/NI)

- Aromatic rings (AR)

- Metal Coordinating areas

Exclusion volumes (XVOL) can be added to represent steric constraints of the binding pocket [2]. This abstraction enables the identification of new chemotypes through "scaffold hopping," a primary advantage of pharmacophore-based virtual screening [13].

There are two principal methodologies for pharmacophore model development, each with distinct synergies with lead compounds:

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

This approach relies on the three-dimensional structure of the macromolecular target, typically obtained from sources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [2]. The workflow involves:

- Protein Preparation: Critical evaluation and optimization of the target structure, including protonation states and missing atoms [2].

- Ligand-Binding Site Detection: Identification of the key binding site using tools like GRID or LUDI, which analyze protein surfaces for potential interaction sites [2].

- Feature Generation and Selection: Derivation of a pharmacophore hypothesis from the interactions between the protein and a bound lead compound (in a co-crystal structure) or from an analysis of the empty binding pocket to identify essential chemical features for bioactivity [2].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

When a 3D protein structure is unavailable, pharmacophore models can be built from a set of known active lead compounds [2]. This method assumes that compounds sharing common biological activity possess common pharmacophoric features. The model is generated by identifying the steric and electronic features shared among these active ligands, often incorporating their bioactive conformations [2].

Quantitative and Automated Advances: Enhancing Synergy with Machine Learning

Traditional pharmacophore modeling can be tedious and reliant on expert knowledge. Recent advancements aim to automate this process and introduce quantitative predictive power, deepening the synergy with lead compound data.

The QPhAR Workflow: From Compounds to Ranked Hits

The Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship (QPhAR) methodology introduces a fully automated, ligand-based workflow for building predictive models from a small set of lead compounds (typically 15–50 ligands with known activity values like IC₅₀ or Kᵢ) [22]. The end-to-end process transforms qualitative models into quantitative screening tools:

- Dataset Preparation: A dataset for the target of interest is prepared and split into training and test sets [22].

- QPhAR Model Generation: A quantitative pharmacophore model is generated using the training set molecules. This model is validated on the separate test set [22].

- Pharmacophore Refinement: An algorithm automatically selects features that drive pharmacophore model quality using Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) information extracted from the validated QPhAR model, resulting in a refined pharmacophore with high discriminatory power [22].

- Virtual Screening and Hit Ranking: The refined pharmacophore is used for virtual screening of large compound databases. Crucially, the hits obtained are ranked by their predicted activity values from the QPhAR model, providing a prioritized list for biological testing [22].

This workflow demonstrates how lead compound data are directly leveraged to create an optimized, quantitative tool for identifying and prioritizing new chemical matter.

AI-Driven Conformation Generation with DiffPhore

Deep learning is now being applied to pharmacophore-guided tasks. DiffPhore is a knowledge-guided diffusion framework for 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping [23]. Its main concept is to utilize ligand-pharmacophore matching knowledge to guide the generation of ligand conformations that maximally map to a given pharmacophore model [23].

The framework consists of three core modules:

- Knowledge-Guided LPM Encoder: Encodes the ligand conformation and pharmacophore model as a geometric graph, incorporating explicit rules for pharmacophore type and directional matching [23].

- Diffusion-Based Conformation Generator: Estimates translation, rotation, and torsion transformations for the ligand conformation at each denoising step, parameterized by an SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network [23].

- Calibrated Conformation Sampler: Adjusts the conformation perturbation strategy to reduce the discrepancy between training and inference phases [23].

DiffPhore has shown state-of-the-art performance in predicting binding conformations and superior power in virtual screening for lead discovery, successfully identifying structurally distinct inhibitors for targets like human glutaminyl cyclases [23].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

This protocol is applicable when a high-resolution structure of the target protein, preferably in complex with a lead compound, is available [2].

Required Input:

- 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., from PDB) or a reliable homology model.

- Structure of a known active lead compound (if available for complex-based modeling).

Methodology:

- Protein Preparation: Using a molecular modeling environment (e.g., Maestro, MOE), add hydrogen atoms, assign protonation states, and correct any structural anomalies. Energy minimization may be performed.

- Binding Site Analysis: If no ligand is bound, use tools like GRID or LUDI to identify and characterize the binding pocket [2].

- Model Generation:

- For a protein-ligand complex, analyze the specific interactions (H-bonds, hydrophobic contacts, ionic interactions) between the lead compound and the protein.

- Use software like LigandScout or MOE to automatically translate these interactions into pharmacophore features (HBA, HBD, H, etc.).

- Manually curate the features, retaining those critical for binding, and add exclusion volumes to represent the protein's steric constraints [2].

- Model Validation: Validate the model by screening a small, diverse library containing known actives and inactives. Assess its ability to enrich actives (Enrichment Factor) and discriminate them from inactives.

- Virtual Screening: Use the validated model as a query to screen large molecular databases (e.g., ZINC, ChEMBL). Compounds matching the pharmacophore hypothesis are selected as hits.

Protocol 2: Ligand-Based QPhAR Modeling and Hit Prioritization

This protocol is used when multiple lead compounds with known activity data are available, enabling the construction of a quantitative model [22].

Required Input:

- A set of 15-50 compounds with measured activity (e.g., IC₅₀, Kᵢ) for the same target.

- Chemical structures of the compounds.

Methodology:

- Data Curation and Conformation Generation: Prepare the dataset by generating representative 3D conformations for each input molecule [13].

- Model Training and Validation:

- Split the dataset into training and test sets.

- Input the training set into the QPhAR algorithm, which will automatically generate a consensus (merged) pharmacophore and align all training pharmacophores to it [13].

- The algorithm builds a machine learning model that relates the spatial arrangement of features in the merged pharmacophore to the biological activity [13].

- Validate the model's predictive power on the held-out test set using metrics like R² and RMSE [22].

- Pharmacophore Refinement: Use the built-in algorithm to extract a refined pharmacophore from the QPhAR model, optimized for virtual screening performance based on SAR [22].

- Virtual Screening and Quantitative Ranking:

- Screen a database with the refined pharmacophore.

- Instead of a binary result, the QPhAR model predicts a continuous activity value for each hit [22].

- Output a rank-ordered list of virtual hits based on their predicted potency, guiding the selection of compounds for experimental testing.

Data Presentation and Analysis

Table 1: Performance Comparison of QPhAR-Based Refined Pharmacophores versus Baseline Shared-Feature Pharmacophores. The baseline models were generated from the most active compounds in the training set, while QPhAR models were generated using the automated algorithm. Performance was scored using a composite metric (F~Composite~) that emphasizes the identification of true positives while reducing false positives, a key objective in virtual screening [22].

| Data Source | Baseline F~Composite~-Score | QPhAR F~Composite~-Score | QPhAR Model R² | QPhAR Model RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ece et al. [22] | 0.38 | 0.58 | 0.88 | 0.41 |

| Garg et al. (hERG) [22] | 0.00 | 0.40 | 0.67 | 0.56 |

| Ma et al. [22] | 0.57 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 0.44 |

| Wang et al. [22] | 0.69 | 0.58 | 0.56 | 0.46 |

| Krovat et al. [22] | 0.94 | 0.56 | 0.50 | 0.70 |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling. This table details key software, databases, and resources that form the foundational toolkit for conducting pharmacophore-based virtual screening studies.

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Pharmacophore Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) [2] | Database | Source of experimental 3D protein structures for structure-based pharmacophore modeling. |

| ZINC [23] | Database | Large, publicly available database of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. |

| ChEMBL [13] | Database | Database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties and associated bioactivity data. |

| LigandScout [24] | Software | Platform for creating structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore models and performing virtual screening. |

| PHASE [13] | Software (Schrödinger) | Tool for developing ligand-based pharmacophore hypotheses and performing 3D-QSAR studies. |

| HypoGen/Catalyst [13] | Software (BioVia) | Algorithm for generating quantitative pharmacophore models from a set of active and inactive compounds. |

| ELIXIR-A [24] | Software Tool | An open-source, Python-based application for refining and comparing multiple pharmacophore models. |

| Pharmit [24] | Online Tool | Interactive online tool for pharmacophore-based virtual screening. |

| QPhAR [22] [13] | Algorithm/Method | A novel method for constructing quantitative pharmacophore models from a set of ligands with activity data. |

| DiffPhore [23] | AI Framework | A knowledge-guided diffusion model for 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping and conformation generation. |

The synergy between lead compounds and pharmacophore models is a powerful driving force in modern drug discovery. This guide has detailed how lead compounds serve as the critical input for constructing both structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore models, which in turn become intelligent queries for identifying novel chemical matter. The emergence of quantitative methods like QPhAR and AI-powered frameworks like DiffPhore marks a significant evolution in this field. These technologies automate complex modeling steps, enhance predictive robustness, and provide deeper, data-driven insights from lead compound datasets. By integrating these advanced computational approaches, researchers can more effectively navigate chemical space, accelerating the identification and optimization of novel therapeutic agents in a cost- and time-efficient manner.

Implementing Pharmacophore Screening: From AI to Real-World Case Studies

Workflow of a Pharmacophore Virtual Screening Campaign

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening (VS) represents a cornerstone of modern computer-aided drug discovery (CADD), serving as an efficient strategy to identify novel hit compounds from extensive chemical libraries by defining the essential steric and electronic features necessary for molecular recognition at a biological target [2]. This approach significantly reduces the time and cost associated with experimental high-throughput screening while enabling scaffold hopping—the identification of structurally diverse compounds that share the same pharmacophoric features [2] [13]. Within the broader context of lead identification research, pharmacophore VS serves as a powerful triage tool, rapidly prioritizing candidate molecules for further experimental validation and accelerating the early drug discovery pipeline [25] [26]. This technical guide details the comprehensive workflow of a pharmacophore virtual screening campaign, providing researchers with a structured methodology applicable to diverse therapeutic targets.

Theoretical Foundations of Pharmacophore Models

Definition and Core Features

A pharmacophore is formally defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [2]. This abstract representation focuses on molecular interaction capabilities rather than specific chemical structures, enabling the identification of chemically distinct compounds that exhibit similar biological activity.

The most critical pharmacophoric features include [2]:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA) and Donors (HBD): Atoms or groups capable of participating in hydrogen bonding.

- Hydrophobic Areas (H): Non-polar regions favoring van der Waals interactions.

- Positively/Negatively Ionizable Groups (PI/NI): Functional groups that can become charged under physiological conditions.

- Aromatic Rings (AR): Planar systems enabling π-π stacking and cation-π interactions.

- Exclusion Volumes (XVOL): Spatial constraints representing forbidden regions occupied by the target protein.

Pharmacophore Generation Approaches

The construction of a pharmacophore hypothesis can be achieved through two principal methodologies, each with distinct requirements and applications as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

| Approach | Required Input Data | Key Steps | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based | 3D Protein Structure (with or without bound ligand) [2] | 1. Protein preparation2. Binding site detection3. Interaction analysis4. Feature generation & selection | Directly reflects complementarity to binding site; High specificity when complex structure available [2] | Dependent on quality of protein structure; May generate excessive features without ligand guidance [2] |

| Ligand-Based | Set of known active compounds (and optionally inactive compounds) [2] [27] | 1. Conformational analysis2. Molecular alignment3. Common feature identification4. Model validation | Applicable when protein structure unknown; Leverages existing structure-activity relationships [2] | Limited by diversity and quality of known actives; May miss critical target interactions [2] |

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling relies on the three-dimensional structure of the target protein, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or computational methods like homology modeling [2]. The critical first step involves thorough protein preparation, including assignment of protonation states, addition of hydrogen atoms, and correction of structural issues [2]. Subsequent binding site analysis using tools like GRID or LUDI identifies key interaction points, which are then translated into pharmacophore features [2]. When a protein-ligand complex structure is available, the bioactive ligand conformation provides superior guidance for feature selection and spatial arrangement [2].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling extracts common chemical features from a set of known active molecules that are presumed to be responsible for biological activity [2]. The Electron-Conformational (EC) method represents an advanced implementation, using computational analysis of conformational space and electronic structure to derive matrices of congruity that capture the essential features shared by active compounds but absent in inactive ones [27]. This approach effectively identifies the pharmacophore as a necessary condition for activity while also enabling quantitative bioactivity prediction through regression analysis incorporating pharmacophore flexibilities and auxiliary group effects [27].

Comprehensive Workflow for Pharmacophore Virtual Screening

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of a pharmacophore virtual screening campaign, incorporating both structure-based and ligand-based approaches:

Phase 1: Data Preparation and Model Generation

Step 1: Data Collection and Curation The initial phase requires gathering high-quality structural or ligand activity data. For structure-based approaches, the RCSB Protein Data Bank (www.rcsb.org) serves as the primary resource for experimental protein structures [2]. Critical assessment of structure quality—including resolution, completeness, and absence of artifacts—is essential [2]. For ligand-based approaches, databases like ChEMBL provide curated bioactivity data for known active compounds [13]. The preparation of ligand structures must include careful conformational sampling and energy minimization to ensure biologically relevant geometries [25].

Step 2: Pharmacophore Model Generation For structure-based models, binding site detection represents a critical step that can be accomplished using tools like GRID, which employs molecular interaction fields, or LUDI, which applies geometric rules derived from experimental structures [2]. The generated interaction points are translated into pharmacophore features, with careful selection to retain only those essential for bioactivity [2].

For ligand-based models, the FragmentScout methodology exemplifies an innovative approach that aggregates pharmacophore feature information from multiple experimental fragment poses, such as those obtained from XChem high-throughput crystallographic screening [28]. This method generates a joint pharmacophore query that comprehensively represents the interaction capabilities of a binding site by combining features from multiple fragment structures [28].

Step 3: Model Validation and Optimization Before proceeding to screening, pharmacophore models must be rigorously validated to ensure their ability to distinguish known active compounds from inactive ones [25]. This typically involves screening a decoy set containing active and inactive molecules, with evaluation metrics including enrichment factors, hit rates, and statistical measures like ROC curves [13]. Model refinement may involve adjustment of feature tolerances, inclusion of exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints, or optimization of feature combinations to improve selectivity [2].

Phase 2: Virtual Screening Implementation

Step 4: Database Preparation Large-scale chemical databases such as ZINC (containing over 22 million compounds) serve as screening sources [25]. Database preprocessing typically includes:

- Application of drug-like filters (e.g., molecular weight <500, rotatable bonds <15) [25]

- Generation of representative 3D conformations for each compound

- Standardization of tautomeric and protonation states

- Calculation of molecular descriptors for subsequent analysis

Step 5: Pharmacophore-Based Screening The validated pharmacophore model serves as a query to search the prepared database using software tools like LigandScout, ZINCPharmer, or MOE [25] [28]. The screening algorithm identifies compounds whose 3D conformations match the spatial arrangement of pharmacophore features within defined tolerance ranges [29]. For example, in a study targeting Staphylococcus epidermidis TcaR, pharmacophore screening of over 22 million compounds yielded 708 initial hits, which were subsequently filtered to 308 compounds based on molecular properties [25].

Advanced implementations like LigandScout XT employ the Greedy 3-Point Search algorithm, which identifies optimal alignments through a matching-feature-pair maximizing strategy, enabling efficient screening of ultra-large libraries with minimal pre-filtering requirements [28].

Phase 3: Post-Screening Analysis and Hit Prioritization

Step 6: Molecular Docking and Binding Mode Analysis Compounds identified through pharmacophore screening typically undergo molecular docking to refine binding pose predictions and assess complementarity to the target binding site [25]. For instance, in the TcaR inhibitor study, the 308 pharmacophore hits were docked using AutoDock with a grid-defined binding site and Lamarckian genetic algorithm, resulting in the identification of 16 compounds with superior binding energies compared to the reference molecule [25]. Docking validation through redocking of known crystallographic ligands ensures protocol accuracy [25].

Step 7: ADMET and Physicochemical Property Profiling Promising hits are evaluated for drug-like properties through computational assessment of absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) parameters [26]. Additionally, density functional theory (DFT) simulations can provide electronic properties (HOMO, LUMO, molecular electrostatic potentials) that influence binding interactions and metabolic stability [25]. In the LpxH inhibitor study, this process identified two lead compounds with favorable drug-like properties and stability profiles [26].

Step 8: Experimental Validation and Hit-to-Lead Optimization The final prioritized hits proceed to experimental testing, typically beginning with in vitro assays to confirm biological activity [30]. Successful confirmation initiates hit-to-lead optimization, where structural modifications enhance potency, selectivity, and pharmacological properties [25]. The quantitative pharmacophore activity relationship (QPHAR) method supports this optimization by building regression models that correlate pharmacophore features with biological activity, enabling prediction of compound potency during analog design [13].

Advanced Applications and Integrative Approaches

Machine Learning-Accelerated Pharmacophore Screening

Traditional molecular docking of ultra-large chemical libraries remains computationally prohibitive [30]. Machine learning (ML) approaches now offer significant acceleration by learning the relationship between molecular structures and docking scores, enabling rapid prioritization of compounds for subsequent docking studies [30]. In one implementation targeting monoamine oxidase inhibitors, an ensemble ML model achieved a 1000-fold acceleration in binding energy prediction compared to classical docking, while maintaining strong correlation with actual docking results [30]. This methodology can be generalized to other biological targets, as it learns from docking results rather than limited experimental activity data [30].

Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationships (QPHAR)

Traditional QSAR methods utilize molecular descriptors as input, but QPHAR employs pharmacophore representations instead, offering advantages in generalization and reduced bias toward overrepresented functional groups [13]. The QPHAR algorithm constructs a consensus pharmacophore from training samples, aligns input pharmacophores to this reference, and uses spatial relationships to build predictive models [13]. Validation across 250 diverse datasets demonstrated robust performance (average RMSE 0.62), even with small training sets of 15-20 samples, making it particularly valuable for lead optimization [13].

Fragment-Based Pharmacophore Screening

The FragmentScout workflow represents a novel approach that leverages XChem fragment screening data to generate aggregated pharmacophore queries [28]. By combining feature information from all experimental fragment poses within a binding site, this method creates comprehensive pharmacophore models that facilitate the evolution of millimolar fragment hits to micromolar leads [28]. Applied to SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 helicase, this approach identified 13 novel micromolar inhibitors validated in cellular antiviral assays, demonstrating the effectiveness of fragment-based pharmacophore screening [28].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore Virtual Screening

| Tool Category | Representative Software/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Modeling | LigandScout [28] [13] | Structure-based & ligand-based pharmacophore generation | Feature identification, model building, virtual screening |

| ZINCPharmer [25] | Online pharmacophore-based screening | Rapid screening of ZINC database using pharmacophore queries | |

| MOE [26] [29] | Integrated drug discovery platform | Pharmacophore search, molecular modeling, QSAR | |

| Virtual Screening Databases | ZINC [25] [30] | Publicly accessible compound database | Source of screening compounds (>22 million molecules) |

| ChEMBL [30] [13] | Bioactivity database | Source of known active compounds for model building | |

| RCSB PDB [2] [28] | Protein Data Bank | Source of 3D protein structures for structure-based design | |

| Molecular Docking | AutoDock [25] | Molecular docking suite | Binding pose prediction, affinity estimation |

| Glide [28] | Precision docking software | High-throughput virtual screening, pose prediction | |

| Smina [30] | Docking software with scoring function | Customizable docking, machine learning integration | |

| Machine Learning | PharmacoNet [31] | Deep learning-guided pharmacophore modeling | AI-enhanced pharmacophore modeling and screening |

| QPHAR [13] | Quantitative pharmacophore modeling | Building regression models linking pharmacophores to activity |

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening represents a powerful methodology within the lead identification paradigm, effectively bridging the gap between target identification and experimental validation. The structured workflow encompassing model generation, virtual screening, and hit prioritization provides a robust framework for identifying novel chemical starting points across diverse therapeutic areas. Recent advancements in machine learning acceleration, quantitative pharmacophore relationships, and fragment-based approaches continue to enhance the efficiency and predictive power of these methods. When properly implemented and integrated with complementary computational and experimental techniques, pharmacophore virtual screening significantly accelerates the early drug discovery process, ultimately contributing to the identification of promising therapeutic candidates for further development.