Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening: A Comprehensive Guide for Modern Drug Discovery

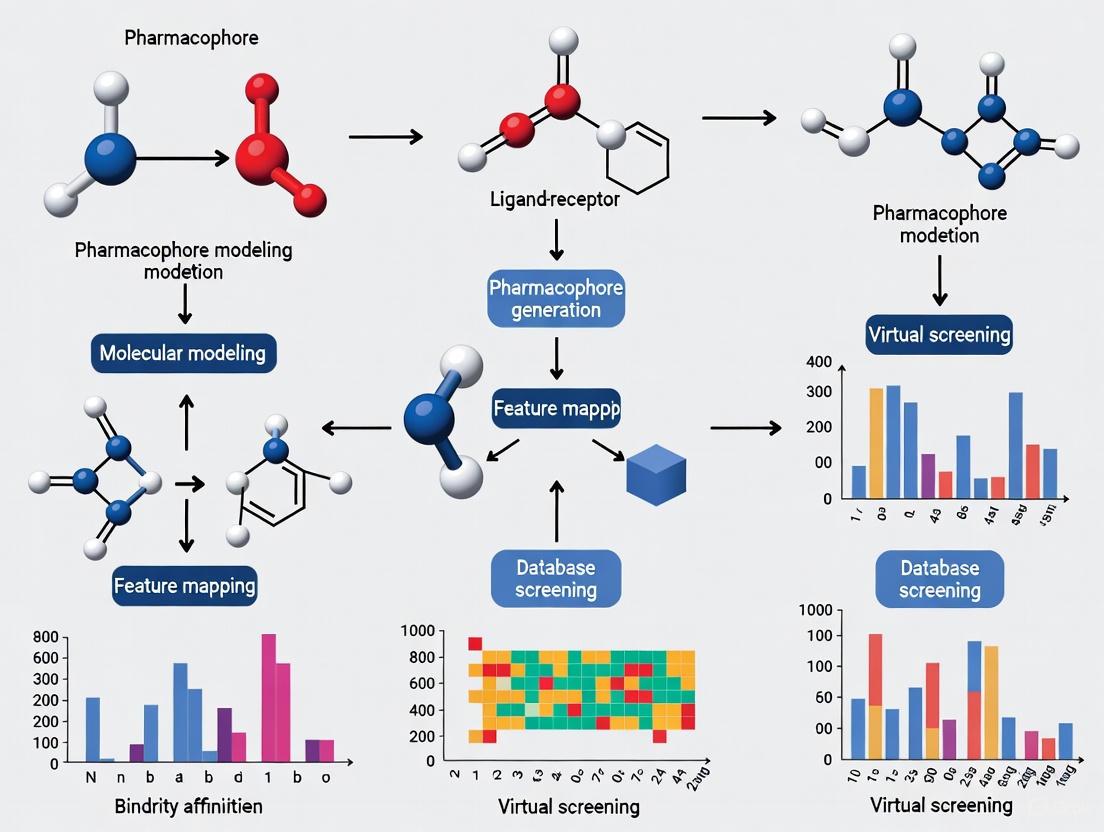

This article provides a thorough exploration of pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening, essential computational techniques in contemporary drug discovery.

Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening: A Comprehensive Guide for Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a thorough exploration of pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening, essential computational techniques in contemporary drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational concepts, methodological approaches, practical optimization strategies, and rigorous validation techniques. The content bridges theoretical principles with real-world application, addressing ligand-based and structure-based methods, the integration of machine learning, and hybrid workflows. By synthesizing current literature and recent advances, this guide serves as a strategic resource for efficiently identifying and optimizing novel therapeutic candidates, ultimately reducing the time and cost associated with traditional drug development.

Understanding the Core Concepts: From Pharmacophore Definition to Virtual Screening Principles

In the field of computer-aided drug design (CADD), the pharmacophore concept is a foundational principle that bridges the gap between molecular structure and biological activity [1] [2]. Defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [1] [3] [2], a pharmacophore provides an abstract representation of the key functional attributes required for molecular recognition. This model distills complex molecular structures into core interaction capacities, focusing on chemical features rather than specific molecular scaffolds [1]. Consequently, pharmacophore modeling has become an indispensable tool in modern drug discovery, enabling efficient virtual screening, lead optimization, and de novo drug design [1] [4] [2].

This technical guide examines the core principles of pharmacophore modeling, detailing its essential features, modeling methodologies, and applications within virtual screening workflows. By framing these concepts within the context of a broader thesis on pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening research, this document aims to provide researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive reference for leveraging pharmacophore techniques in their investigative work.

Core Features of a Pharmacophore

A pharmacophore model comprises several key steric and electronic features that represent the capacity for favorable interactions with a biological target [1] [5]. These features are abstract representations of chemical functionalities, not specific atoms or functional groups, allowing the model to identify structurally diverse compounds that share common interaction potential [2].

Table 1: Essential Pharmacophoric Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature Type | Chemical Group Examples | Role in Molecular Recognition |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA) | Carbonyl oxygen, nitro groups, sulfoxide oxygen [6] | Forms hydrogen bonds with hydrogen bond donors on the target protein [5]. |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD) | Amino groups, hydroxyl groups, amide NH [6] | Forms hydrogen bonds with hydrogen bond acceptors on the target protein [5]. |

| Hydrophobic (H) | Alkyl chains, alicyclic rings [5] | Engages in van der Waals interactions with non-polar regions of the target [5]. |

| Aromatic (AR) | Phenyl, pyridine, other aromatic rings [2] | Participates in cation-π, π-π stacking, and hydrophobic interactions [5]. |

| Positively Ionizable (PI) | Primary, secondary, or tertiary amines (at specific pH) [2] [6] | Forms ionic bonds with negatively charged (anionic) groups on the target [5]. |

| Negatively Ionizable (NI) | Carboxylic acids, tetrazoles, sulfonamides [2] [6] | Forms ionic bonds with positively charged (cationic) groups on the target [5]. |

The spatial arrangement of these features in three-dimensional space is critical for biological activity [3]. This arrangement is typically represented by points, vectors, planes, and exclusion volumes in a 3D pharmacophore model [2]. Exclusion volumes are particularly important as they represent regions in space occupied by the target protein, thereby preventing steric clash and improving the selectivity of the model [2].

Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

The construction of a pharmacophore model can be achieved through several computational approaches, primarily categorized as structure-based, ligand-based, and complex-based methods [1]. The choice of method depends on the available input data, such as the presence of a known protein structure or a set of active ligands.

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling relies on the three-dimensional structure of the biological target, typically obtained from sources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [1] [2]. The workflow involves a critical analysis of the target's binding site to identify key amino acid residues and map their chemical environment [2]. This process reveals potential interaction points—complementary features that a ligand must possess for effective binding, such as hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic patches, and areas suitable for ionic interactions [2] [7]. When the structure of a protein-ligand complex is available, the model's accuracy is significantly enhanced, as the ligand's bioactive conformation directly informs the spatial placement of pharmacophore features [1] [2].

Diagram Title: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

In the absence of a known target structure, ligand-based pharmacophore modeling offers a powerful alternative [3]. This approach analyzes a set of active ligands to identify their common chemical features and their three-dimensional arrangement [1] [3]. The underlying principle is that compounds binding to the same target and eliciting a similar biological response likely share a common pharmacophore [2]. The process begins with a conformational analysis of each ligand to account for molecular flexibility. Subsequently, the ligands are superimposed to find their maximum common 3D pharmacophore, which represents the essential features and their geometric relationships [3]. Advanced algorithms, such as clustering (e.g., k-means), are often employed to generate an ensemble pharmacophore that captures the shared characteristics of the entire ligand set [3].

Diagram Title: Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Virtual Screening Protocol

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening is a primary application in drug discovery, used to rapidly identify potential hit compounds from large chemical libraries [3] [2]. The protocol involves using a validated pharmacophore model as a 3D query to search databases of compound structures [3]. The screening process evaluates each compound in the database for its ability to fit the pharmacophore model, considering both the presence of required chemical features and their geometric constraints [2]. Compounds that match the model are considered potential hits and are prioritized for further experimental testing [2]. This method significantly reduces the time and cost associated with experimental high-throughput screening [2].

Table 2: Key Software Tools for Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

| Software/Tool | Primary Function | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| BIOVIA Discovery Studio (CATALYST) [7] | Pharmacophore modeling, validation, and screening | Building hypotheses from ligands, receptors, or complexes; virtual screening. |

| LigandScout [1] [3] | Structure- and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling | Creating and visualizing pharmacophores from PDB complexes; virtual screening. |

| RDKit [3] [4] | Cheminformatics toolkit with pharmacophore capabilities | Handling molecular data, feature extraction, and basic pharmacophore operations. |

| Phase [1] | Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling and QSAR | Developing 3D pharmacophore hypotheses and atom-based QSAR models. |

| PMapper [6] | Pharmacophore fingerprint generation | Creating 2D pharmacophore fingerprints for similarity searching. |

Detailed Methodology: Generating a Ligand-Based Ensemble Pharmacophore

The following protocol outlines the steps for creating an ensemble pharmacophore from a set of pre-aligned ligands, a common technique for targets like EGFR with known active compounds [3].

- Input Preparation: Obtain a set of known active ligands. If necessary, pre-align them using molecular superposition methods to ensure a common spatial frame of reference [3].

- Feature Extraction: For each aligned ligand, identify and map key pharmacophoric features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors, acceptors, hydrophobic centers) onto its structure. This can be achieved using cheminformatics toolkits like RDKit [3].

- Coordinate Collection: Gather the 3D coordinates of all identified features, grouping them by their type (e.g., all donor coordinates, all acceptor coordinates) [3].

- Feature Clustering: For each feature type, apply a clustering algorithm (e.g., k-means clustering) to the collected coordinates. This process groups spatially proximate features from different ligands into distinct clusters [3].

- Cluster Selection: Analyze the resulting clusters to select the most representative ones. This selection is often based on the cluster's population (number of features) and the spatial consistency across the ligand set [3].

- Model Generation: Define the final ensemble pharmacophore model using the centroid coordinates of the selected clusters. Each centroid becomes a pharmacophore feature in the final model, representing a consensus location for that specific interaction type across all active ligands [3].

Advanced Integrations: Pharmacophores in Deep Learning and Machine Learning

The field of pharmacophore modeling is being transformed by the integration of machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) techniques [8]. A prominent example is the Pharmacophore-Guided deep learning approach for bioactive Molecule Generation (PGMG) [4]. This model uses a graph neural network to encode a pharmacophore—represented as a set of spatially distributed chemical features—into a latent representation. A transformer decoder then generates molecular structures (in SMILES format) that match the input pharmacophore [4]. This approach allows for the de novo design of bioactive molecules, effectively bridging the gap between pharmacophore constraints and generative AI. The use of latent variables enables PGMG to capture the many-to-many relationship between pharmacophores and molecules, thereby boosting the diversity of generated compounds [4]. Such integrations highlight the evolving role of pharmacophores from passive screening queries to active guides in generative molecular design [4] [8].

The pharmacophore, as an ensemble of essential steric and electronic features, remains a cornerstone of rational drug design. Its power lies in its abstract nature, which enables the identification of structurally diverse compounds based on shared molecular interaction capacities. As computational methods advance, the integration of pharmacophores with machine learning and deep generative models opens new frontiers for de novo drug design, particularly for novel targets with limited experimental data. For researchers engaged in virtual screening, a thorough understanding of pharmacophore features, modeling methodologies, and application protocols is indispensable for accelerating the discovery and optimization of novel therapeutic agents.

The Evolution of the Pharmacophore Concept in Medicinal Chemistry

The pharmacophore concept, established by Paul Ehrlich in 1909, was initially defined as a "molecular framework that carries (phoros) the essential features responsible for a drug's (pharmacon) biological activity" [9]. This foundational idea has evolved substantially over the past century. According to the modern International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) definition, a pharmacophore model represents "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [9] [10] [2]. This evolution reflects the transition from a simple structural concept to an abstract representation of molecular interactions critical for drug discovery.

The enduring value of the pharmacophore concept lies in its ability to abstract key interaction features from specific molecular structures, enabling the identification of structurally diverse compounds that share common biological activity [2]. Pharmacophore approaches have become one of the major tools in drug discovery after more than a century of development, with extensive applications in virtual screening, de novo design, and lead optimization [9]. The fundamental principle underpinning pharmacophore modeling is that molecules sharing a similar three-dimensional arrangement of essential chemical features will likely exhibit similar biological activities against a common target [2].

Historical Development and Key Milestones

The conceptual journey of the pharmacophore began with Paul Ehrlich's early work on drug-receptor interactions in the late 19th century [2]. Emil Fischer's "Lock & Key" hypothesis in 1894 further solidified the theoretical foundation by proposing that a ligand and its receptor fit together like a key and lock to enable specific interactions [2]. Throughout the 20th century, this concept was refined through collective efforts of numerous researchers, with Schueler providing the basis for our modern understanding of pharmacophores [10].

The late 20th and early 21st centuries witnessed remarkable computational advancements that transformed pharmacophore modeling from a theoretical concept to a practical drug discovery tool. The development of automated pharmacophore modeling platforms such as DISCO, GASP, HypoGen, and PHASE enabled more efficient and accurate model generation [9]. More recently, the integration of machine learning (ML) methods has begun to address longstanding challenges in pharmacophore modeling, including model optimization and quantitative activity prediction [11] [12]. The emergence of the "informacophore" concept represents a further evolution, combining traditional structural features with computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations of chemical structure [13].

Fundamental Principles of Pharmacophore Modeling

Essential Pharmacophore Features

A pharmacophore model abstracts specific atoms or functional groups into generalized chemical features representing potential interaction points with a biological target. The most important pharmacophore feature types are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Core Pharmacophore Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature Type | Symbol | Description | Functional Groups Represented |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | HBA | Atom capable of accepting hydrogen bonds | Carbonyl oxygen, nitro groups, ether oxygens |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | HBD | Atom with hydrogen capable of donating | Amine groups, hydroxyl groups, amide NH |

| Hydrophobic | H | Non-polar regions | Alkyl chains, aromatic rings, steroid systems |

| Positively Ionizable | PI | Groups that can carry positive charge | Primary, secondary, tertiary amines |

| Negatively Ionizable | NI | Groups that can carry negative charge | Carboxylic acids, phosphates, sulfates |

| Aromatic | AR | Electron-rich π-systems | Phenyl, pyridine, other aromatic rings |

| Exclusion Volumes | XVOL | Sterically forbidden regions | Represented as spheres filling protein space |

These features are represented in three-dimensional space as geometric entities such as spheres (points), planes, and vectors with tolerance ranges that account for molecular flexibility and minor variations in ligand-receptor interactions [2]. The spatial arrangement of these features defines the essential interaction pattern required for biological activity.

Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling relies on the three-dimensional structure of a macromolecular target or a macromolecule-ligand complex. The workflow involves several critical steps:

Protein Preparation: The 3D structure of the target, obtained from sources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB), is prepared by evaluating residue protonation states, adding hydrogen atoms, and addressing missing residues or atoms [2]. When experimental structures are unavailable, computational techniques such as homology modeling or AlphaFold2 can generate reliable 3D models [2].

Ligand-Binding Site Detection: The binding site can be identified through analysis of protein-ligand complexes or using computational tools like GRID and LUDI that probe the protein surface for potential interaction sites based on energetic, geometric, or evolutionary properties [2].

Feature Generation and Selection: Interaction points between the protein and ligand are identified and translated into pharmacophore features. When a protein-ligand complex is available, features are derived directly from the observed interactions. In the absence of a bound ligand, the binding site is analyzed to detect all potential interaction points, which are then filtered to retain only those essential for bioactivity [2].

Exclusion Volume Assignment: To represent the spatial constraints of the binding pocket, exclusion volumes are added to prevent the mapping of compounds that would experience steric clashes with the protein [10].

The primary advantage of structure-based approaches is their ability to identify novel chemotypes without prior knowledge of active ligands, making them particularly valuable for targets with limited ligand information [9].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling is employed when the 3D structure of the target macromolecule is unknown. This approach extracts common chemical features from the 3D structures of known active ligands. The general methodology involves:

Training Set Selection: A set of structurally diverse active compounds with confirmed biological activity is selected. The quality and diversity of this training set directly impact model quality [10].

Conformational Analysis: Multiple conformations are generated for each training compound to account for molecular flexibility and identify potential bioactive conformations [9].

Molecular Alignment and Feature Extraction: The training set compounds are aligned in 3D space, and common chemical features essential for their bioactivity are identified [9] [2].

Model Validation: The generated pharmacophore hypotheses are validated using datasets containing both active and inactive compounds to assess their ability to discriminate between them [10].

Ligand-based methods are particularly effective for scaffold hopping—identifying structurally diverse compounds that share the same essential pharmacophore—due to their focus on abstract interaction features rather than specific molecular frameworks [9].

Computational Methodologies and Workflows

Pharmacophore Model Generation Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the core workflows for both structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling:

Advanced Algorithms and Recent Computational Advances

Early pharmacophore modeling algorithms such as HypoGen employed a systematic approach to generate pharmacophore hypotheses from active compounds, while PHASE introduced pharmacophore fields for quantitative activity prediction [9] [12]. Contemporary research focuses on enhancing modeling accuracy and efficiency through several innovative approaches:

- Multi-Complex-Based Pharmacophore Maps: Integrating information from multiple protein-ligand complexes to create comprehensive pharmacophore models that account for binding site flexibility [9].

- Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship (QPhAR): A novel methodology that constructs quantitative models using pure pharmacophore representations rather than molecular structures, enabling activity prediction based on pharmacophore features alone [12].

- Machine Learning-Enhanced Pharmacophore Optimization: Algorithms that automatically select features driving pharmacophore model quality using structure-activity relationship (SAR) information extracted from validated QPhAR models [11].

- Efficient Search Algorithms: Tools like Pharmer utilize advanced data structures (KDB-trees) and algorithms (Bloom fingerprints) to enable exact pharmacophore searches of million-compound libraries in seconds [14].

Table 2: Comparison of Representative Pharmacophore Modeling Software

| Software/Tool | Modeling Approach | Key Features | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHASE | Ligand-based & Structure-based | Pharmacophore fields, PLS regression for QSAR | Virtual screening, activity prediction |

| HypoGen/Catalyst | Ligand-based | Hypothesis generation from most active compounds | Quantitative pharmacophore modeling |

| LigandScout | Structure-based | Automated feature detection from complexes | Virtual screening, scaffold hopping |

| Pharmer | Screening | KDB-tree, efficient large-library search | Ultra-large virtual screening |

| QPhAR | Quantitative | Pure pharmacophore-based QSAR | Activity prediction, model optimization |

Applications in Drug Discovery

Virtual Screening and Lead Identification

Pharmacophore-based virtual screening (VS) represents one of the most successful applications of the pharmacophore concept in drug discovery. In this approach, a pharmacophore model serves as a query to search large chemical databases and identify compounds that match the essential feature arrangement [9] [10]. Compared to physical high-throughput screening (HTS), virtual screening offers significant advantages in cost reduction and efficiency improvement [14].

Reported hit rates from prospective pharmacophore-based virtual screening typically range from 5% to 40%, substantially higher than the <1% hit rates generally observed with random selection in HTS [10]. For example, virtual screening against glycogen synthase kinase-3β yielded a 0.55% hit rate compared to random selection, while screens for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) γ and protein tyrosine phosphatase-1B showed hit rates of 0.075% and 0.021%, respectively [10].

The following diagram illustrates the virtual screening workflow and its integration with the broader drug discovery process:

With the recent expansion of commercially accessible compound libraries to over 65 billion make-on-demand molecules, ultra-large virtual screening (ULVS) has emerged as a powerful paradigm [13] [15]. Efficient pharmacophore search technologies like Pharmer are essential for navigating these vast chemical spaces, scaling with query complexity rather than database size [14].

Scaffold Hopping and Lead Optimization

The abstract nature of pharmacophore features makes them particularly valuable for scaffold hopping—identifying structurally diverse compounds that share common biological activity through equivalent interaction patterns [9] [2]. This application is crucial for overcoming intellectual property limitations or improving drug-like properties while maintaining efficacy.

In lead optimization, pharmacophore models help elucidate structure-activity relationships (SAR) and guide strategic molecular modifications [9]. Quantitative pharmacophore models, such as those generated by QPhAR, provide insights into favorable and unfavorable interactions, enabling medicinal chemists to prioritize structural changes with the highest probability of improving potency and selectivity [11] [12].

Integration with Modern Drug Discovery Paradigms

The Emergence of Informacophores

The ongoing evolution of the pharmacophore concept has led to the emergence of the "informacophore"—an extension that incorporates data-driven insights derived not only from SARs but also from computed molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and machine-learned representations of chemical structure [13]. This fusion of structural chemistry with informatics enables a more systematic and bias-resistant strategy for scaffold modification and optimization.

Unlike traditional pharmacophore models that rely on human-defined heuristics, informacophores leverage machine learning to analyze complex, ultra-large datasets and identify patterns beyond human perception capacity [13]. While this approach offers greater predictive power, it also presents challenges in model interpretability, as learned features may become opaque or harder to link back to specific chemical properties [13].

Quantitative Pharmacophore Activity Relationship (QPhAR)

The QPhAR methodology represents a significant advancement in pharmacophore modeling by enabling the construction of quantitative models using pure pharmacophore representations [12]. This approach offers several advantages over traditional QSAR methods:

- Reduced Structural Bias: The abstract nature of pharmacophores minimizes bias toward overrepresented functional groups in small datasets.

- Enhanced Generalization: Well-crafted quantitative pharmacophore models can generalize to underrepresented or missing molecular features in the training set.

- Scaffold-Hopping Capability: Maintains the scaffold-hopping advantage of pharmacophores while adding quantitative predictive power.

QPhAR operates by first finding a consensus pharmacophore (merged-pharmacophore) from all training samples, aligning input pharmacophores to this merged model, and then using the positional information as input to a machine learning algorithm that derives a quantitative relationship between pharmacophore features and biological activities [12]. Validation studies across diverse datasets have demonstrated robust performance even with small training sets (15-20 samples), making it particularly valuable for lead optimization [12].

The following diagram illustrates the QPhAR workflow for automated pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening:

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Validation

While computational approaches have revolutionized early-stage drug discovery, biological functional assays remain indispensable for validating theoretical predictions [13]. The following table details key research reagents and materials essential for experimental pharmacophore model validation and compound screening.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Pharmacophore-Based Drug Discovery

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Proteins | Target-based binding or activity assays | Purified human enzymes/recceptors (e.g., hERG K+ channel, hydroxysteroid dehydrogenases) |

| Chemical Libraries | Experimental screening of virtual hits | Commercially available libraries (Enamine: 65B, OTAVA: 55B make-on-demand compounds) |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Functional activity assessment | High-content screening, phenotypic assays, organoid/3D culture systems |

| ChEMBL Database | Source of bioactivity data | >23M activity values, IC50/Ki data for model training and validation |

| Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD-E) | Decoy molecules for model validation | Optimized decoys with similar 1D properties but different topologies vs. active molecules |

Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, pharmacophore approaches still face several challenges that limit their full potential. Key limitations include:

- Conformational Sampling: Adequate coverage of the conformational space of flexible molecules remains computationally demanding [9].

- Feature Definition: Standardized and biochemically accurate definitions of pharmacophore features require further refinement [9].

- Model Selection: Choosing the optimal pharmacophore hypothesis from multiple possibilities can be subjective and dataset-dependent [11].

- Target Flexibility: Accounting for protein flexibility and induced fit effects in structure-based models presents ongoing challenges [9].

Future developments will likely focus on integrating pharmacophore modeling with artificial intelligence and machine learning to address these limitations [11] [13]. The increasing availability of ultra-large chemical libraries will drive the development of more efficient screening algorithms capable of navigating billion-compound spaces [14] [15]. Additionally, the integration of dynamic pharmacophore concepts that account for temporal changes in interaction patterns during binding may enhance model accuracy and biological relevance [9].

The evolution of the pharmacophore concept from Paul Ehrlich's original framework to modern informacophores and quantitative approaches demonstrates its enduring value in medicinal chemistry. As computational power increases and algorithms become more sophisticated, pharmacophore-based strategies will continue to play a crucial role in reducing the time and cost associated with drug discovery and development, potentially unlocking novel therapeutic opportunities for challenging targets.

The discovery and development of new therapeutic agents remains one of the most challenging endeavors in biomedical sciences, with estimated costs exceeding $2.5 billion per approved drug and timelines extending beyond 10–15 years [16]. In this context, virtual screening (VS) has emerged as a fundamental computational technique that revolutionizes early-stage drug discovery by enabling researchers to systematically assess large chemical spaces and identify compounds with desired properties before initiating costly experimental work [16] [17]. This approach represents a powerful bridge between chemical complexity and biological function, leveraging computational power to predict how small molecules might interact with biological targets.

Virtual screening functions as a computational counterpart to experimental high-throughput screening (HTS), significantly reducing the number of compounds requiring experimental evaluation while maintaining or improving the quality of identified lead compounds [17]. The strategic implementation of computational screening methods early in the drug discovery process has been shown to lead to significant cost savings and accelerated development timelines [16]. As chemical libraries continue to grow—with make-on-demand libraries now containing >70 billion readily available molecules—the importance of efficient virtual screening methodologies becomes increasingly critical for navigating this vast chemical space [18].

Fundamental Concepts: Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

The Pharmacophore Concept

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines a pharmacophore as "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [19] [2]. In simpler terms, a pharmacophore is an abstract representation of the molecular features essential for biological activity, explaining how structurally diverse ligands can bind to a common receptor site [19].

A well-defined pharmacophore model includes both hydrophobic volumes and hydrogen bond vectors, with typical features being [19] [2]:

- Hydrophobic centroids (H)

- Aromatic rings (AR)

- Hydrogen bond acceptors (HBA) or donors (HBD)

- Positive (PI) or negative ionizable (NI) groups

- Metal coordinating areas

Table 1: Common Pharmacophore Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature Type | Symbol | Description | Example Functional Groups |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Bond Acceptor | HBA | Atoms that can accept hydrogen bonds | Carbonyl oxygen, nitro groups |

| Hydrogen Bond Donor | HBD | Atoms that can donate hydrogen bonds | Amine groups, hydroxyl groups |

| Hydrophobic | H | Non-polar regions that favor lipid environments | Alkyl chains, aromatic rings |

| Aromatic Ring | AR | Planar conjugated ring systems | Phenyl, pyridine rings |

| Positive Ionizable | PI | Groups that can carry positive charge | Primary amines |

| Negative Ionizable | NI | Groups that can carry negative charge | Carboxylic acids |

Virtual Screening Approaches

Virtual screening methodologies can be broadly categorized into two main approaches [17]:

Ligand-Based Virtual Screening (LBVS): This approach relies on knowledge of known active compounds. It includes:

- 2D molecular similarity approaches using molecular fingerprints

- 3D similarity searches (pharmacophore, molecular shapes)

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling

Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS): This method requires the 3D structure of the biological target and includes:

- Molecular docking of compounds into binding sites

- Scoring based on complementary interactions

- Consensus scoring or docking approaches

The integration of multiple screening strategies has become the gold standard in modern virtual screening campaigns, leveraging the strengths of each method while compensating for their individual limitations [16].

Methodological Framework and Experimental Protocols

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

The structure-based pharmacophore approach requires the three-dimensional structure of a macromolecular target, typically obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) or through computational techniques like homology modeling [2]. The workflow consists of several critical steps:

Protein Preparation: The initial step involves preparing the protein structure by evaluating residue protonation states, adding hydrogen atoms (absent in X-ray structures), and addressing missing residues or atoms. The stereochemical and energetic parameters must be checked to account for the general quality and biological-chemical sense of the investigated target [2].

Ligand-Binding Site Detection: This crucial step can be achieved using bioinformatics tools that inspect the protein surface to search for potential ligand-binding sites according to various properties (evolutionary, geometric, energetic, statistical). Programs like GRID and LUDI are commonly used for this purpose [2].

Pharmacophore Feature Generation: The binding site characterization is used to derive an interaction map and build pharmacophore hypotheses describing the type and spatial arrangement of chemical features required for ligand binding. When a protein-ligand complex structure is available, this process is more accurate as the ligand's bioactive conformation directly guides feature identification [2].

Figure 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

When the 3D structure of the target protein is unavailable, ligand-based approaches can be employed. The process for developing a ligand-based pharmacophore model generally involves [19]:

- Training Set Selection: Choosing a structurally diverse set of molecules with known biological activities (both active and inactive compounds)

- Conformational Analysis: Generating a set of low-energy conformations for each molecule

- Molecular Superimposition: Fitting all combinations of low-energy conformations of the molecules to identify common features

- Abstraction: Transforming the superimposed molecules into an abstract representation of pharmacophore elements

- Validation: Testing the model's ability to account for differences in biological activity across a range of molecules

Virtual Screening Protocol

A comprehensive virtual screening protocol typically integrates both pharmacophore modeling and molecular docking approaches. A representative study targeting VEGFR-2 and c-Met dual inhibitors demonstrates this integrated approach [20]:

Step 1: Compound Library Preparation

- Source: >1.28 million compounds from ChemDiv database

- Preparation: Remove counterions, solvent moieties, and salts; add hydrogen atoms

- Initial Filtration: Apply Lipinski's Rule of Five and Veber rules

Step 2: ADMET Profiling

- Evaluate key properties including aqueous solubility, blood-brain barrier penetration, cytochrome P4502D6 inhibition, hepatotoxicity, human intestinal absorption, and plasma protein binding

Step 3: Pharmacophore-Based Screening

- Generate pharmacophore models based on crystal structures of target proteins

- Screen pre-filtered compound library against pharmacophore models

- Select compounds that match essential pharmacophore features

Step 4: Molecular Docking

- Dock potential hit compounds into binding sites of target proteins

- Score and rank compounds based on predicted binding affinities

- Select top candidates for further analysis

Step 5: Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

- Perform MD simulations (typically 100-200 ns) to assess binding stability

- Calculate binding free energies using MM/PBSA or MM/GBSA methods

- Confirm stability of protein-ligand interactions over simulation time

Figure 2: Integrated Virtual Screening Workflow

Advanced Approaches and Recent Technological Developments

AI-Accelerated Virtual Screening

Recent breakthroughs in artificial intelligence have transformed virtual screening capabilities, particularly for navigating ultralarge chemical libraries. Machine learning-guided docking screens now enable rapid evaluation of billions of compounds through innovative workflows [18]:

Machine Learning-Accelerated Pipeline: This approach combines conformal prediction (CP) with molecular docking to enable virtual screens of multi-billion-scale compound libraries. The workflow involves:

- Training classification algorithms on a subset of docked compounds

- Using the conformal prediction framework to select compounds from the ultralarge library

- Docking only the predicted active compounds

- Experimental validation of top-ranking hits

This strategy has demonstrated the ability to reduce the computational cost of structure-based virtual screening by more than 1,000-fold, making screening of multi-billion compound libraries feasible with modest computational resources [18].

Open-Source Platforms and Web Servers

Several platforms have been developed to make advanced virtual screening accessible to broader scientific communities:

Qsarna: A comprehensive online platform that combines machine learning for activity prediction with traditional molecular docking. It provides end-to-end support for virtual screening campaigns and includes fragment-based generative models for exploring novel chemical spaces [16].

OpenVS: An open-source AI-accelerated virtual screening platform that integrates improved physics-based force fields (RosettaGenFF-VS) with active learning techniques. This platform has demonstrated success in identifying hits for challenging targets like KLHDC2 and NaV1.7, with screening completed in less than seven days [21].

Table 2: Comparison of Virtual Screening Platforms and Their Capabilities

| Platform | Type | Key Features | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qsarna | Web-based | Combines ML with molecular docking, fragment-based generative models | Freely available to academic researchers |

| OpenVS | Open-source | RosettaGenFF-VS forcefield, active learning, receptor flexibility | Open-source with flexible deployment options |

| Commercial Suites | Commercial | Comprehensive tools for docking, QSAR, ADMET prediction | Licensing required |

| Web Servers | Web-based | Specialized tools for specific VS tasks | Freely accessible |

Case Studies in Virtual Screening Applications

Discovery of VEGFR-2 and c-Met Dual Inhibitors

A comprehensive virtual screening approach identified potential dual-target inhibitors for VEGFR-2 and c-Met, two critical targets in cancer pathogenesis [20]. The study employed:

- Virtual Screening Process: 1.28 million compounds initially filtered based on Lipinski and Veber rules

- Pharmacophore Modeling: Developed using 10 VEGFR-2 complexes and 8 c-Met complexes from PDB

- Hit Identification: 18 compounds showed potential inhibitory activity against both targets

- Validation: Molecular dynamics simulations (100 ns) and MM/PBSA calculations confirmed stability of protein-ligand interactions

The results identified compound17924 and compound4312 as promising candidates with superior binding free energies compared to positive controls, demonstrating the power of integrated virtual screening approaches in identifying novel therapeutic candidates [20].

Identification of XIAP Protein Inhibitors

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling was used to identify natural anti-cancer agents targeting the XIAP protein, an important target in apoptosis regulation [22]. The methodology included:

- Pharmacophore Generation: Based on XIAP protein complex (PDB: 5OQW) with 14 chemical features identified

- Model Validation: Excellent early enrichment factor (EF1% = 10.0) and AUC value (0.98)

- Virtual Screening: ZINC database screening followed by molecular docking

- Hit Confirmation: MD simulations confirmed stability of three natural compounds as promising XIAP inhibitors

This case study demonstrates how structure-based pharmacophore modeling can identify natural products with potential therapeutic applications while minimizing toxicity concerns associated with synthetic compounds [22].

Accelerated Screening of Multi-Billion Compound Libraries

Recent applications of AI-accelerated virtual screening have demonstrated remarkable efficiency in screening ultralarge libraries [18]:

- Library Size: 3.5 billion compounds from make-on-demand collections

- Targets: G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) including A2A adenosine (A2AR) and D2 dopamine (D2R) receptors

- Screening Efficiency: Computational cost reduced by more than 1,000-fold

- Experimental Validation: Successful identification of ligands with multi-target activity tailored for therapeutic effect

This approach addresses the fundamental challenge of navigating the vast chemical space (estimated at >10^60 drug-like molecules) with practical computational resources [18].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Virtual Screening

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | RCSB PDB, AlphaFold DB | Source of 3D protein structures for structure-based methods | Publicly accessible |

| Compound Libraries | ZINC, ChemDiv, Enamine REAL | Collections of purchasable compounds for screening | Commercial and publicly accessible |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Discovery Studio, LigandScout | Generate and validate pharmacophore models | Commercial |

| Molecular Docking Tools | AutoDock Vina, RosettaVS, Glide | Predict binding poses and affinities | Both open-source and commercial |

| MD Simulation Packages | GROMACS, AMBER, CHARMM | Assess binding stability and calculate free energies | Mostly open-source |

| Web-Based Platforms | Qsarna, DrugFlow, MolProphet | Integrated virtual screening workflows | Varying access models |

Virtual screening represents an indispensable computational bridge between chemistry and biology, dramatically accelerating the identification of promising therapeutic candidates while reducing development costs. The integration of pharmacophore modeling with virtual screening provides a powerful framework for navigating complex chemical spaces and identifying novel bioactive compounds.

Recent advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning are further transforming the field, enabling the efficient screening of multi-billion compound libraries that were previously considered intractable [21] [18]. The development of open-source platforms and web-accessible tools continues to democratize access to these advanced methodologies, supporting broader adoption across the scientific community.

As make-on-demand libraries continue to expand—potentially reaching trillions of compounds in the near future—the evolution of virtual screening methodologies will remain essential for leveraging these vast chemical resources for therapeutic discovery. The ongoing integration of computational predictions with experimental validation creates a powerful feedback loop that continues to refine and improve virtual screening accuracy, solidifying its role as a cornerstone of modern drug discovery.

Library Enrichment and Compound Design

In the contemporary drug discovery landscape, pharmacophore modeling serves as an indispensable computational framework for library enrichment and rational compound design. A pharmacophore is formally defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [2]. This abstract representation of molecular interactions provides a powerful strategy for navigating vast chemical spaces efficiently, enabling researchers to identify and design compounds with desired biological activity while transcending the limitations of specific molecular scaffolds.

The integration of pharmacophore approaches with virtual screening has become a cornerstone of computer-aided drug discovery (CADD), directly addressing the critical bottlenecks of cost and time in pharmaceutical development. Traditional drug discovery is notoriously protracted and expensive, requiring over 10 years and approximately $4 billion to bring a single drug to market [23]. Pharmacophore-based virtual screening offers a compelling alternative to labor-intensive high-throughput screening (HTS) by computationally prioritizing compounds with the highest probability of activity before synthesis or experimental testing [2]. This approach has gained further momentum with the incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning (DL) methodologies, which have dramatically enhanced the accuracy, speed, and scalability of pharmacophore-guided discovery campaigns [24] [25].

Within the broader thesis of pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening research, this technical guide examines the key objectives of library enrichment and compound design. It provides an in-depth examination of fundamental methodologies, advanced AI-driven innovations, practical implementation protocols, and illustrative case studies that underscore the transformative impact of pharmacophore technologies on modern drug discovery.

Fundamental Methodologies and Approaches

Structure-Based and Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Pharmacophore modeling strategies are primarily categorized into structure-based and ligand-based approaches, each with distinct methodologies, requirements, and applications for library enrichment and compound design.

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling relies on the three-dimensional structural information of the target protein, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or computational prediction tools like AlphaFold [2]. The workflow initiates with critical protein preparation steps, including protonation state assignment, hydrogen atom addition, and structural quality assessment. Subsequently, the ligand-binding site is characterized using tools such as GRID or LUDI, which identify regions conducive to specific molecular interactions [2]. The pharmacophore model is then generated by mapping complementary chemical features—hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, charged groups, and aromatic systems—that a ligand must possess for effective binding. When a protein-ligand complex structure is available, the model can be refined based on observed interaction patterns, potentially incorporating exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints [2].

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling is employed when the target structure is unknown but information about active compounds is available. This approach deduces the essential pharmacophore features by identifying common chemical functionalities and their spatial arrangements across multiple known active ligands [2]. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) principles may be incorporated to weight features according to their contribution to biological activity. The resultant model encapsulates the critical interaction elements responsible for ligand recognition and efficacy, providing a template for virtual screening without requiring structural knowledge of the target protein [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Structure-Based and Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

| Aspect | Structure-Based Approach | Ligand-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Required Input Data | 3D protein structure or protein-ligand complex | Set of known active ligands and optionally inactive compounds |

| Key Steps | Protein preparation, binding site detection, feature mapping, exclusion volume placement | Conformational analysis, molecular alignment, common feature identification |

| Advantages | Incorporates target structural constraints; identifies novel chemotypes | Applicable when target structure unknown; leverages known SAR data |

| Limitations | Dependent on quality and relevance of protein structure | Limited by diversity and quality of known active compounds |

| Primary Screening Application | De novo lead identification; scaffold hopping | Lead optimization; analog searching |

Core Pharmacophore Features and Their Geometric Relationships

All pharmacophore models comprise fundamental chemical features that define the necessary interactions between a ligand and its biological target. The most essential feature types include [2]:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA): Atoms or regions capable of accepting hydrogen bonds, typically oxygen, nitrogen, or fluorine atoms.

- Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD): Groups containing hydrogen atoms that can donate hydrogen bonds, such as hydroxyl, amine, or amide functionalities.

- Hydrophobic Areas (H): Non-polar regions that participate in van der Waals interactions, often represented by aliphatic or aromatic carbon chains.

- Positively/Negatively Ionizable Groups (PI/NI): Functional groups that can carry positive or negative charges under physiological conditions, enabling electrostatic interactions.

- Aromatic Systems (AR): Pi-electron systems that facilitate cation-pi, pi-pi stacking, or hydrophobic interactions.

- Metal Coordinating Atoms (MB): Atoms with lone electron pairs capable of coordinating metal ions, such as histidine nitrogen or cysteine sulfur.

These features are represented in pharmacophore models as geometric entities—spheres, vectors, or planes—that define the spatial requirements for molecular recognition. The relative positions and orientations of these features create a three-dimensional query that can be used to screen compound libraries for molecules possessing complementary chemical functionality in compatible arrangements [2].

Diagram 1: Workflow for Structure-Based and Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Advanced AI-Driven Innovations in Pharmacophore Approaches

Deep Learning-Enhanced Pharmacophore Modeling and Screening

The integration of artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning, has revolutionized pharmacophore-based drug discovery by addressing longstanding challenges in speed, accuracy, and scalability. Several pioneering platforms demonstrate the transformative potential of AI in this domain:

DiffPhore represents a groundbreaking knowledge-guided diffusion framework for three-dimensional ligand-pharmacophore mapping. This approach leverages ligand-pharmacophore matching knowledge to guide conformation generation while utilizing calibrated sampling to mitigate exposure bias in the iterative conformation search process [24]. Trained on comprehensive datasets of 3D ligand-pharmacophore pairs (CpxPhoreSet and LigPhoreSet), DiffPhore has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in predicting ligand binding conformations, surpassing traditional pharmacophore tools and several advanced docking methods [24]. The system employs three core modules: a knowledge-guided ligand-pharmacophore mapping encoder that captures type and directional alignment rules; a diffusion-based conformation generator that estimates translation, rotation, and torsion transformations; and a calibrated conformation sampler that adjusts perturbation strategies to align training and inference phases [24].

PharmacoNet stands as the first deep learning framework specifically designed for pharmacophore modeling toward ultra-fast virtual screening. This system provides fully automated protein-based pharmacophore modeling and evaluates ligand potency using a parameterized analytical scoring function, ensuring strong generalization capability across unseen targets and ligands [25]. In benchmark studies, PharmacoNet demonstrated remarkable efficiency and accuracy compared to traditional docking methods and existing deep learning-based scoring models. Its practical utility was confirmed through the successful identification of selective inhibitors from 187 million compounds against cannabinoid receptors in just 21 hours on a single CPU [25].

VirtuDockDL exemplifies the integration of graph neural networks (GNNs) with pharmacophore-inspired screening. This platform employs GNNs to analyze molecular graphs constructed from compound structures, predicting biological activity based on learned patterns that implicitly capture pharmacophore features [26]. During validation, VirtuDockDL achieved exceptional performance metrics (99% accuracy, F1 score of 0.992, and AUC of 0.99 on the HER2 dataset), surpassing both traditional deep learning frameworks and molecular docking tools [26].

AI-Enabled Scaffold Hopping and Molecular Representation

Scaffold hopping—the identification of structurally distinct compounds with similar biological activity—represents a critical application of pharmacophore approaches in compound design. AI-driven molecular representation methods have dramatically enhanced scaffold hopping capabilities by enabling more nuanced characterization of molecular structures and their functional properties [27].

Traditional molecular representation methods, such as extended-connectivity fingerprints (ECFPs), encoded predefined structural patterns but struggled to capture subtle relationships between molecular architecture and biological function [27]. Modern AI-driven approaches, including graph neural networks (GNNs), variational autoencoders (VAEs), and transformer models, learn continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings directly from large and complex datasets [27]. These representations capture both local and global molecular characteristics, facilitating the identification of structurally diverse compounds that maintain essential pharmacophore features.

The scaffold hopping process leverages these advanced representations to navigate chemical space more efficiently, discovering novel core structures that preserve critical interactions while optimizing properties such as toxicity, metabolic stability, or intellectual property positioning [27]. AI-enhanced scaffold hopping has been successfully applied across multiple therapeutic areas, leading to the identification of new chemical entities with improved efficacy and safety profiles.

Table 2: AI-Enhanced Pharmacophore Platforms and Their Applications

| Platform | AI Methodology | Key Capabilities | Demonstrated Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| DiffPhore [24] | Knowledge-guided diffusion model | 3D ligand-pharmacophore mapping, binding conformation prediction, virtual screening | Superior to traditional pharmacophore tools and advanced docking methods; successful identification of glutaminyl cyclase inhibitors |

| PharmacoNet [25] | Deep learning-based pharmacophore modeling | Ultra-fast virtual screening, protein-based pharmacophore modeling, ligand potency evaluation | Screened 187M compounds in 21 hours on single CPU; high generalization across unseen targets |

| VirtuDockDL [26] | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Molecular graph analysis, activity prediction, virtual screening | 99% accuracy, F1=0.992, AUC=0.99 on HER2 dataset; outperformed DeepChem and AutoDock Vina |

| PGMG [24] | Latent variable modeling | Pharmacophore-guided molecular generation, many-to-many mapping between pharmacophores and molecules | Enabled generation of novel compounds matching pharmacophore constraints |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation Guidelines

Integrated Protocol: Combining DECL Data with Pharmacophore Modeling

This protocol outlines an approach for leveraging DNA-encoded chemical library (DECL) screening data to develop pharmacophore models for virtual screening, based on the successful application to tankyrase 1 (TNKS1) inhibitors [28].

Step 1: DECL Affinity Selection and Hit Validation

- Perform affinity selection experiments with the target protein using multiple DECLs with diverse library designs and building blocks [28].

- Identify enriched compounds through normalized sequence count analysis, focusing on structurally diverse chemotypes with significant enrichment [28].

- Synthesize off-DNA representatives of promising hits and evaluate their activity in functional assays (e.g., IC₅₀ determination) [28].

- Analyze structure-activity relationships to distinguish true binders from false positives resulting from unpredictable linker-protein interactions [28].

Step 2: Pharmacophore Model Generation

- Translate validated DECL hits into pharmacophore hypotheses using structure-based or ligand-based approaches [28].

- For structure-based modeling: Utilize available protein-ligand complex structures to identify key interaction features. If structural data is limited, employ homology modeling or molecular docking to generate binding poses [28].

- For ligand-based modeling: Identify common pharmacophore features across active DECL hits while accounting for conformational flexibility [28].

- Refine the model by incorporating exclusion volumes to represent steric constraints and optimize feature tolerances based on activity data [28].

Step 3: Virtual Screening with Integrated Approaches

- Apply the generated pharmacophore model as a 3D query to screen large compound databases (e.g., ZINC, Molport) [28].

- Employ parallel docking-based screening to evaluate potential binding modes and affinities of pharmacophore-matched compounds [28].

- Prioritize hits using binding free-energy calculations or additional scoring functions to refine selection [28].

- Select candidate compounds for experimental validation, focusing on structures outside the chemical space covered by the original DECLs to explore novel chemotypes [28].

Step 4: Experimental Validation and Hit-to-Lead Optimization

- Procure or synthesize top-ranked virtual hits for biochemical and cellular assays [28].

- Determine binding modes through structural biology techniques (X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM) when possible to validate pharmacophore alignment [28].

- Initiate hit-to-lead optimization using the pharmacophore model as a guide for structure-activity relationship studies [28].

Deep Learning-Based Virtual Screening Protocol

This protocol implements AI-enhanced pharmacophore approaches for ultra-large-scale virtual screening, based on validated methodologies from DiffPhore and PharmacoNet [24] [25].

Step 1: Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- For structure-based screening: Obtain 3D protein structures from PDB or generate using prediction tools like AlphaFold [2] [24].

- For ligand-based screening: Curate sets of known active and inactive compounds from public databases (ChEMBL, BindingDB) or proprietary sources [24].

- Standardize molecular structures, generate tautomers, and enumerate stereoisomers as appropriate [24] [26].

- Generate multiple conformations for each compound to ensure adequate coverage of conformational space [24].

Step 2: Model Implementation and Configuration

- Select appropriate AI-powered pharmacophore platform based on screening objectives:

- For binding pose prediction: Implement DiffPhore with knowledge-guided diffusion framework [24].

- For ultra-large-scale screening: Deploy PharmacoNet for rapid protein-based pharmacophore modeling [25].

- For activity prediction: Utilize VirtuDockDL with graph neural networks for molecular graph analysis [26].

- Configure platform-specific parameters: For DiffPhore, specify pharmacophore feature types and sampling parameters; for PharmacoNet, set scoring function thresholds; for VirtuDockDL, define GNN architecture and training parameters [24] [26] [25].

Step 3: Screening Execution and Hit Identification

- Process compound libraries through the selected AI-pharmacophore platform [26] [25].

- Apply appropriate filtering strategies: molecular weight, lipophilicity, structural alerts, or other drug-like properties [28] [26].

- Rank compounds based on platform-specific scoring functions: fitness scores (DiffPhore), pharmacophore matching scores (PharmacoNet), or predicted activity (VirtuDockDL) [24] [26] [25].

- Select top-ranked compounds for further analysis, ensuring structural diversity to avoid over-representation of specific scaffolds [24].

Step 4: Validation and Experimental Triaging

- Perform molecular docking studies with selected hits to confirm binding modes and interactions [28] [26].

- Apply more computationally intensive methods (molecular dynamics, free-energy calculations) to a subset of promising candidates [28].

- Prioritize compounds for experimental testing based on convergence of multiple computational approaches, structural novelty, and synthetic accessibility [28] [24].

Diagram 2: AI-Enhanced Pharmacophore Screening Workflow

Case Studies and Practical Applications

TNKS1 Inhibitor Discovery Using DECL-Derived Pharmacophores

A comprehensive study demonstrating the power of integrating DECL screening with pharmacophore modeling led to the identification of novel, potent inhibitors of tankyrase 1 (TNKS1), a promising target for cancer therapy [28]. Researchers performed affinity selection experiments with four distinct DECLs (DECL1-4) against TNKS1, identifying numerous enriched compounds containing privileged structural motifs, particularly 2-(2,4-dioxotetrahydropyrimidin-1(2H)-yl)benzoic acid fragments [28]. Following synthesis and validation of representative hits, the researchers translated the DECL screening results into pharmacophore models that captured essential interaction features for TNKS1 binding [28].

These pharmacophore models were subsequently employed for virtual screening of commercial compound databases, identifying novel chemotypes distinct from the original DECL hits. This approach yielded compound 12, a potent TNKS1 inhibitor (IC₅₀ = 22 nM) with a unique structure not represented in the screening libraries [28]. The study provided critical insights into the noise inherent in DECL data and demonstrated how computational methods could extend ligand discovery beyond physically limited compound collections.

AI-Enhanced Pharmacophore Screening for Cannabinoid Receptors

PharmacoNet was applied to the challenging task of identifying selective inhibitors for cannabinoid receptors from an ultra-large library of 187 million compounds [25]. The platform generated fully automated protein-based pharmacophore models and evaluated compound complementarity using a parameterized analytical scoring function. Despite the enormous screening scale, PharmacoNet completed the entire process in just 21 hours on a single CPU, demonstrating unprecedented efficiency for virtual screening at this scale [25]. The identified hits exhibited both high potency and selectivity, validating the approach for target classes with complex chemical recognition requirements.

Natural Product Screening for Anti-Typhoid Agents

A ligand-based pharmacophore approach was successfully employed to identify natural product inhibitors of UDP-2,3-diacylglucosamine hydrolase (LpxH), a crucial enzyme in the lipid A biosynthesis pathway of Salmonella Typhi [29]. Researchers developed a pharmacophore model based on known LpxH inhibitors and screened a natural compound library of 852,445 molecules [29]. Following virtual screening and molecular docking, two lead compounds (1615 and 1553) were selected for molecular dynamics simulations, which confirmed their binding stability at the active site [29]. Comprehensive toxicity prediction and ADMET analysis revealed favorable drug-like properties, with compound 1615 emerging as the most promising inhibitor due to its optimal electronic properties and minimal chemical potential [29].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore-Based Discovery

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function in Pharmacophore Discovery | Example Sources/Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Databases | Data Resource | Source of 3D structural information for structure-based pharmacophore modeling | RCSB PDB, AlphaFold Protein Structure Database [2] |

| Compound Libraries | Chemical Resource | Collections of compounds for virtual screening and experimental validation | ZINC, Molport, Enamine REAL, DECLs [28] [24] |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Computational Tool | Generation, visualization, and application of pharmacophore models | PHASE, Catalyst, MOE, AncPhore [29] [24] |

| AI-Pharmacophore Platforms | AI Tool | Deep learning-enhanced pharmacophore modeling and screening | DiffPhore, PharmacoNet, VirtuDockDL [24] [26] [25] |

| Molecular Representation Tools | Computational Tool | Translation of molecular structures into computer-readable formats | RDKit, Extended-connectivity fingerprints (ECFPs), SMILES [27] [26] |

Pharmacophore modeling continues to evolve as a cornerstone technology for library enrichment and compound design in drug discovery. The integration of artificial intelligence and deep learning methodologies has addressed longstanding challenges in screening efficiency, accuracy, and scalability, enabling researchers to navigate increasingly large chemical spaces with unprecedented precision [24] [26] [25]. The case studies presented demonstrate the tangible impact of these approaches across diverse therapeutic targets and compound classes.

Future developments in pharmacophore-based discovery will likely focus on several key areas: enhanced integration of multi-omics data to contextualize pharmacophore models within broader biological systems [30]; improved handling of molecular flexibility and dynamic binding processes; more sophisticated AI architectures that better capture the complexity of molecular recognition; and streamlined workflows that bridge computational predictions with experimental validation [23] [30]. As these technologies mature, pharmacophore approaches will play an increasingly central role in accelerating the identification and optimization of novel therapeutic agents, ultimately reducing the time and cost associated with drug development [23].

The continuing synergy between traditional pharmacophore principles and modern AI technologies promises to unlock new opportunities in drug discovery, particularly for challenging targets that have historically resisted conventional approaches. By providing a robust framework for capturing the essential features of molecular recognition, pharmacophore modeling will remain an essential component of the drug discovery toolkit, enabling more efficient exploration of chemical space and more rational design of therapeutic compounds.

Comparative Advantages Over Traditional High-Throughput Screening

In the contemporary drug discovery landscape, virtual screening (VS) has emerged as a powerful computational approach to identify novel bioactive compounds, offering a strategic alternative to traditional high-throughput screening (HTS). HTS involves the experimental, robot-assisted testing of hundreds of thousands to millions of compounds in biological assays, a process that is inherently resource-intensive, time-consuming, and costly [31] [32]. In contrast, virtual screening uses computer-based methods to evaluate vast virtual libraries of compounds, prioritizing a much smaller set of promising candidates for experimental validation [2]. Among VS techniques, pharmacophore-based virtual screening (PBVS) has gained particular prominence for its efficiency and effectiveness. This guide details the core concepts of pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening, and provides a comprehensive, evidence-backed analysis of their comparative advantages over traditional HTS, framed for a professional audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Core Concepts: Pharmacophore Modeling and Virtual Screening

The Pharmacophore Model

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines a pharmacophore as "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [2] [33]. In simpler terms, a pharmacophore is an abstract representation of the key chemical functionalities a molecule must possess to bind to a target, divorced from its underlying molecular scaffold.

The most critical pharmacophoric features include [2]:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA)

- Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD)

- Hydrophobic areas (H)

- Positively/Inegatively Ionizable groups (PI/NI)

- Aromatic rings (AR) These features are represented in 3D models as geometric entities like points, spheres, and vectors.

Approaches to Pharmacophore Modeling

There are two primary approaches to generating a pharmacophore model, each with its own workflow:

1. Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: This approach relies on the 3D structural information of the macromolecular target, typically obtained from X-ray crystallography, NMR, or cryo-EM [2]. The workflow involves:

- Protein Preparation: Obtaining and refining the 3D structure, often from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), including correcting protonation states and adding hydrogen atoms [2] [34].

- Binding Site Identification: Defining the ligand-binding pocket using tools like GRID or CASTp [2] [34].

- Feature Generation: Analyzing the binding site to map out potential interaction points (e.g., where a HBA or HBD would interact with a specific amino acid) [2]. If a co-crystallized ligand is present, its interactions directly inform the model's features and their spatial arrangement [2].

2. Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: This method is used when the 3D structure of the target is unknown but a set of active ligands is available [2]. The process involves:

- Ligand Set Curation: Collecting a set of known active compounds with diverse structures but common biological activity.

- Conformational Analysis: Generating representative low-energy 3D conformations for each ligand.

- Common Feature Identification: Superimposing the ligand conformations and identifying the common pharmacophoric features essential for activity [2] [33].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process and workflows for these two primary approaches.

Virtual Screening Workflow

Once a validated pharmacophore model is established, it serves as a query for screening compound databases. The standard PBVS workflow, which can be run on standard computational hardware, involves [2] [35] [34]:

- Database Preparation: Converting a large database of compound structures (e.g., ZINC, CHEMBL, in-house libraries) into a searchable 3D format, often with multiple conformers to account for flexibility.

- Pharmacophore Screening: Using software (e.g., Catalyst, LigandScout, MOE) to rapidly search the database for molecules whose 3D conformations and chemical features match the pharmacophore query.

- Hit Prioritization: The matched compounds, or "hits," are further filtered and prioritized using criteria like fit value, chemical diversity, drug-likeness (Lipinski's Rule of Five), and predicted ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) properties.

- Experimental Validation: The final, shortlisted compounds are procured and tested in vitro to confirm biological activity.

Quantitative Advantages of Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

The theoretical efficiency of PBVS is strongly supported by empirical data. A seminal benchmark study compared PBVS against docking-based VS across eight diverse protein targets [31] [36]. The results demonstrated the superior performance of PBVS.

Table 1: Benchmark Comparison of PBVS vs. Docking-Based VS (DBVS)

| Metric | Pharmacophore-Based VS (PBVS) | Docking-Based VS (DBVS) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Performance | Outperformed DBVS in 14 out of 16 test cases [31] | Lower enrichment factors in most cases [31] |

| Average Hit Rate (Top 2% of database) | Much higher than DBVS [31] [36] | Significantly lower [31] [36] |

| Average Hit Rate (Top 5% of database) | Much higher than DBVS [31] [36] | Significantly lower [31] [36] |

| Key Strength | High efficiency in retrieving active compounds; powerful for scaffold hopping [31] [33] | Directly reflects ligand-receptor binding process [31] |

The following table summarizes the core advantages of PBVS over traditional HTS, highlighting the paradigm shift in early-stage drug discovery.

Table 2: Core Advantages of PBVS Over Traditional HTS

| Feature | Traditional HTS | Pharmacophore-Based VS | Practical Implication for Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | Extremely high (reagents, equipment, compound libraries) [2] | Very low (requires only computational resources) [2] [32] | Drastically reduces financial burden, allowing smaller labs to participate in lead discovery [2]. |

| Time & Speed | Months to screen a library of millions [2] | Days to screen a virtual library of billions [32] | Radically compressed discovery timelines; enables rapid hypothesis testing [37]. |

| Theoretical Library Size | Limited by physical storage and solubility (10^5 - 10^6 compounds) [32] | Virtually unlimited (10^7 - 10^9 compounds) via virtual libraries like ZINC [34] [32] | Explores a vastly larger chemical space, increasing the probability of finding novel chemotypes [32]. |

| Resource Consumption | High consumption of biochemical reagents, plastics, and solvents [2] | Negligible physical resource consumption | Enables sustainable and environmentally friendly screening campaigns. |

| Mechanistic Insight | Provides an activity readout but little direct structural insight. | Built on understanding key ligand-target interactions; provides a hypothesis for activity [2] [33]. | Guides lead optimization and facilitates scaffold hopping to discover novel chemical series [33]. |

Case Studies and Experimental Protocols

The efficacy of PBVS is not merely theoretical but is consistently proven in contemporary research. Below are detailed methodologies from recent successful applications.

Case Study 1: Discovery of Novel HPPD Inhibitors

Objective: To identify novel small-molecule inhibitors of 4-Hydroxyphenylpyruvate Dioxygenase (HPPD), a key herbicide target [38]. Experimental Protocol:

- Pharmacophore Model Generation: Two independent models were created. A ligand-based model (HipHop10) was generated from six highly active known inhibitors (including Mesotrione). A separate structure-based model was built from the crystal complex of Arabidopsis thaliana HPPD [38].

- Virtual Screening: A multi-layer workflow was employed. Over 110,000 compounds from the Bailingwei and TCM databases were first screened against both pharmacophore models. The 333 common hits were then subjected to molecular docking studies to analyze binding modes and interaction stability with key active site residues (e.g., coordination with the metal ion, π-π stacking with Phe381 and Phe424) [38].

- Validation: The top five ranked compounds underwent 100 ns Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to confirm binding stability. This was followed by in vitro enzyme activity assays, which verified that two compounds (C-139 and C-5222) exhibited excellent inhibitory effects (IC50 values of 0.742 µM and 6 nM, respectively) [38].

Case Study 2: Identifying Inhibitors ofPlasmodium falciparum5-ALAS

Objective: To find novel inhibitors of P. falciparum 5-aminolevulinate synthase (5-ALAS), a potential prophylactic antimalarial target [34]. Experimental Protocol:

- Target Preparation: Since no experimental structure was available, a high-quality 3D model of Pf 5-ALAS was built using homology modeling (SWISS-MODEL) and AlphaFold, and validated with MolProbity and SAVES servers [34].

- Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: A pharmacophore model was built directly from the predicted protein structure using the Pharmit server. The model was based on the interaction features of the native cofactor, pyridoxal 5'-phosphate, defining key HBA, HBD, hydrophobic, and aromatic features [34].

- Virtual Screening and Filtering: The model was used to screen over 2.6 million compounds from nine public and commercial databases (e.g., ZINC, CHEMBL, ChemDiv). Hits were filtered by Lipinski's Rule of Five and Veber's rules to ensure drug-likeness. The resulting 2,621 compounds were docked into the protein's active site [34].