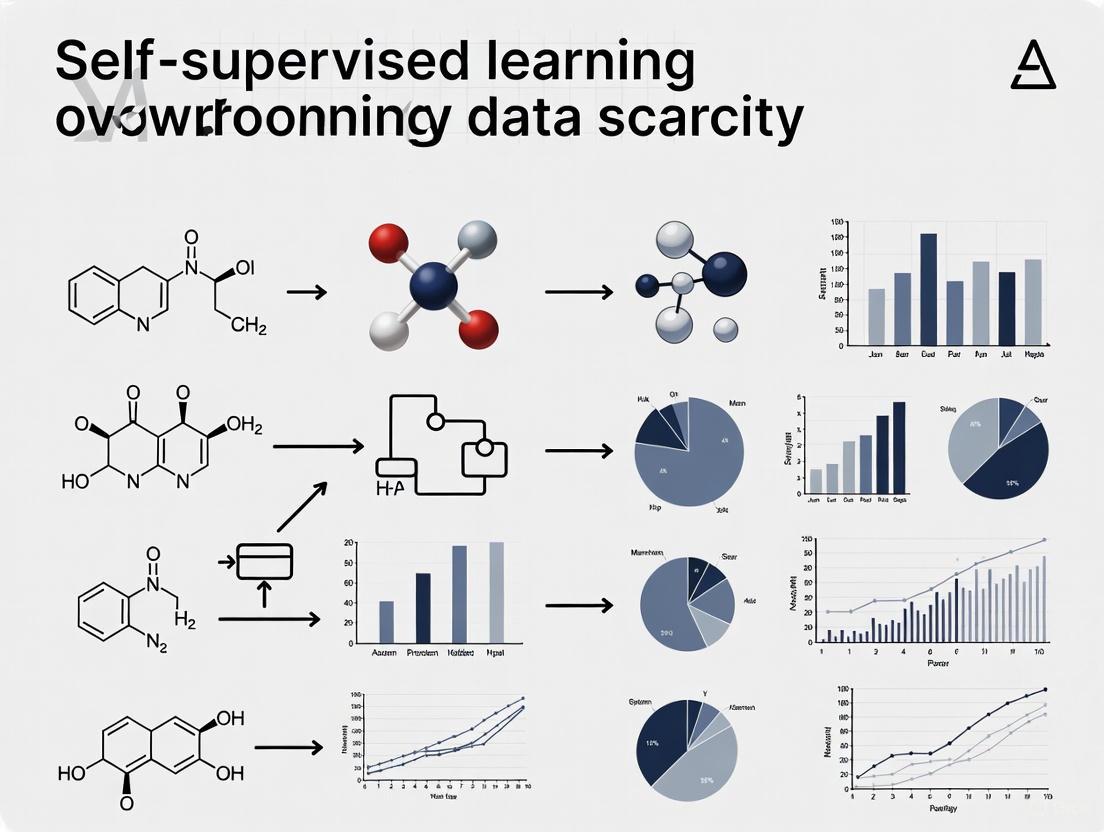

Overcoming Data Scarcity in Drug Discovery: A Self-Supervised Learning Revolution

This article explores the transformative potential of self-supervised learning (SSL) to overcome the critical challenge of data scarcity in drug discovery and development.

Overcoming Data Scarcity in Drug Discovery: A Self-Supervised Learning Revolution

Abstract

This article explores the transformative potential of self-supervised learning (SSL) to overcome the critical challenge of data scarcity in drug discovery and development. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and professionals in the pharmaceutical industry, we provide a comprehensive analysis of how SSL leverages unlabeled data to build robust predictive models. The content covers foundational SSL concepts, details its methodological applications in small molecule and protein design, addresses optimization strategies for real-world challenges like class imbalance, and presents a comparative validation of SSL against traditional supervised approaches. By synthesizing the latest research, this guide serves as a strategic resource for integrating SSL into biomedical research pipelines to accelerate innovation.

The Data Scarcity Crisis and the Rise of Self-Supervised Learning

Defining the Data Bottleneck in Pharmaceutical R&D

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly is a "data bottleneck" in drug discovery? A data bottleneck is a point in the R&D pipeline where the flow of data is constrained, not by a lack of data itself, but by its quality, structure, or accessibility. This limitation prevents AI and machine learning models from being trained effectively, slowing down the entire discovery process. It often arises from insufficient, non-uniform, or privacy-restricted data, which is the primary "reagent" for data-hungry deep learning models [1] [2].

Our model performs well on internal data but generalizes poorly to new chemical spaces. What strategies can help? This is a classic sign of data scarcity or bias in your training set. Several strategies are designed to address this:

- Multi-task Learning (MTL): Instead of training a model for a single task, MTL learns several related tasks simultaneously. The shared representations learned across tasks can lead to more robust models that generalize better, even with limited data for any single task [1].

- Transfer Learning (TL): Start with a model pre-trained on a large, general dataset (e.g., a broad molecular library). Then, fine-tune it on your smaller, specific dataset. This transfers generalizable knowledge to your specialized domain [1].

- Federated Learning (FL): This allows you to collaboratively train models with partners without sharing raw, proprietary data. Each participant trains the model locally, and only model updates (gradients) are shared. This builds a more generalizable model by learning from diverse, otherwise inaccessible datasets [3] [1].

We have vast archives of unlabeled biological data. How can we leverage it? Self-supervised learning (SSL) is the key. SSL methods create artificial labels from the data itself, allowing models to learn patterns and features without manual annotation. For example, you can train a model to predict a missing part of a protein sequence or a masked section of a medical image. This "pre-training" step creates a powerful foundational model that can then be fine-tuned for specific tasks (like predicting binding affinity) with much less labeled data [4] [5].

How can we collaborate with other companies without compromising intellectual property? Federated Learning (FL) is designed for this exact scenario. As highlighted by industry adopters, it creates "trust by architecture" [3]. In a federated system, your proprietary data never leaves your firewall. A global model is distributed to all participants, trained locally on each private dataset, and only the learned model parameters are aggregated. This builds a powerful, shared model while fully preserving data privacy and IP [3] [1].

Advanced Troubleshooting Guide

Problem: Inaccurate Drug-Target Affinity (DTA) Predictions due to Limited Labeled Data.

Issue: Wet lab experiments to determine binding affinity are time-consuming and costly, resulting in scarce high-quality DTA data. This scarcity limits the performance of deep learning models [5].

Solution: Implement a Semi-Supervised Multi-task (SSM) Training Framework [5].

Experimental Protocol:

- Multi-task Training: Co-train the model on the primary DTA prediction task alongside a secondary, self-supervised task like Masked Language Modeling (MLM) for both drug and protein sequences. This forces the model to learn richer, more fundamental representations of molecular and protein structure [5].

- Semi-Supervised Pre-training: Leverage large-scale, unpaired molecular and protein datasets (e.g., from public databases) to pre-train the model. This step enhances the model's general understanding of biochemistry before it ever sees a labeled DTA example [5].

- Feature Integration: Use a lightweight cross-attention module to deeply model the interactions between the drug and target representations, improving prediction accuracy [5].

Table 1: Core Components of the SSM-DTA Framework [5]

| Component | Description | Function in Overcoming Data Scarcity |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-task Training | Combining DTA prediction with Masked Language Modeling. | Leverages paired data more efficiently, improving representation learning. |

| Semi-Supervised Pre-training | Training on large, unlabeled molecular and protein datasets. | Incorporates foundational biochemical knowledge from outside the limited DTA dataset. |

| Cross-Attention Module | A lightweight network for modeling drug-target interactions. | Improves the model's ability to interpret the context between a molecule and its target. |

Problem: Poor Sampling and Scoring in Computational Protein Design.

Issue: Machine learning models for protein design are often evaluated as case studies, making them hard to compare and may not reliably identify high-fitness variants [6].

Solution: Integrate ML-based sampling with biophysical-based scoring in a standardized benchmarking framework.

Experimental Protocol:

- Establish a Toolbox: Use a diverse, standardized toolbox (e.g., within the Rosetta software framework) for side-by-side comparison of different prediction models [6].

- ML-Enhanced Sampling: Employ self-supervised and other ML methods to generate a wide range of potential protein sequences. Research shows ML excels at "purging the sampling space from deleterious mutations" [6].

- Biophysical Scoring: Score the resulting mutations using established biophysical force fields (e.g., Rosetta). Current findings indicate that ML scoring without fine-tuning does not clearly outperform traditional biophysical methods, suggesting a complementary approach is best [6].

Table 2: Comparison of Methods to Overcome Data Scarcity in AI-based Drug Discovery [1]

| Method | Key Principle | Best Used When | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer Learning (TL) | Transfers knowledge from a large, pre-trained model on a related task to a specific task with limited data. | You have a small, specialized dataset but access to a model pre-trained on a large general dataset (e.g., a public molecular library). | Risk of negative transfer if the source and target tasks are not sufficiently related. |

| Active Learning (AL) | Iteratively selects the most valuable data points to be labeled, minimizing labeling cost. | Labeling data (e.g., wet-lab experiments) is expensive and you have a large pool of unlabeled data. | Requires an initial model and an oracle (expert) to label selected samples; can be slow. |

| Multi-task Learning (MTL) | Simultaneously learns several related tasks, sharing representations between them. | You have multiple, related prediction tasks, each with limited data. | Model performance can be sensitive to how tasks are weighted; requires more complex architecture. |

| Federated Learning (FL) | Enables collaborative model training across multiple institutions without sharing raw data. | Data is siloed across organizations due to privacy or IP concerns, but a collective model is desired. | Introduces operational complexity and requires new tooling for model aggregation and synchronization [3]. |

| Data Augmentation (DA) | Artificially expands the training set by creating modified versions of existing data. | Working with image-based data or other data types where label-preserving transformations are possible. | Confidence in label-preserving transformations for molecular data is not yet fully established [1]. |

| Data Synthesis (DS) | Generates artificial data that replicates real-world patterns using AI like Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs). | Experimental data is extremely limited or hard to acquire, such as for rare diseases. | Synthetic data may not fully capture the complexity of real biological systems, leading to model overfitting. |

Workflow Visualization

Semi-Supervised Multi-task (SSM) Workflow

Federated Learning Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Platforms for Data-Centric Drug Discovery

| Tool / Platform | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Rosetta Software Suite [6] | Molecular Modeling Software | Provides a standardized framework for simulating and designing macromolecules, enabling the benchmarking of ML methods against biophysical models. |

| AlphaFold 3 [3] | AI Prediction Model | Predicts the structure and complex interactions of proteins with high accuracy, providing crucial data for target identification and drug design. |

| Federated Learning Platforms (e.g., Apheris) [3] | Collaborative AI Framework | Enables the creation of federated networks where multiple organizations can collaboratively train AI models without sharing raw, proprietary data. |

| AI-driven Discovery Platforms (e.g., Insilico Medicine) [7] | Integrated AI Platform | Accelerates target identification and compound screening by leveraging AI to analyze vast chemical and biological datasets. |

| Automated Protein Production (e.g., Nuclera's eProtein) [8] | Laboratory Automation | Automates protein expression and purification, rapidly generating high-quality experimental data to validate computational predictions and feed AI models. |

| Data & Lab Management (e.g., Cenevo/Labguru) [8] | Digital R&D Platform | Connects data, instruments, and processes in the lab, breaking down data silos and creating well-structured datasets necessary for effective AI. |

What Is Self-Supervised Learning? Moving Beyond Labeled Datasets

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the core idea behind Self-Supervised Learning? Self-supervised learning is a machine learning technique that uses unstructured data itself to generate supervisory signals, rather than relying on manually applied labels [9] [10]. The model is trained to predict any hidden part of its input from any observed part, effectively learning by "filling in the blanks" [9] [10].

How is SSL different from supervised and unsupervised learning? While technically a subset of unsupervised learning because it uses unlabeled data, SSL is used for tasks typical of supervised learning, like classification and regression [9]. The key difference is the source of the "ground truth":

- Supervised Learning: Uses manually labeled datasets.

- Unsupervised Learning: Discovers inherent data structures (e.g., clustering) without any ground truth.

- Self-Supervised Learning: Creates its own supervisory signals from the unlabeled data [9] [10].

When should I consider using SSL in my research? SSL is particularly valuable in scenarios where labeled data is scarce, expensive, or time-consuming to acquire, but large amounts of unlabeled data are available [11] [9] [12]. It has shown significant success in domains including biomedical imaging [13], drug discovery [14] [12], and prognostics [11].

What are 'pretext tasks' and 'downstream tasks'?

- Pretext Task: An auxiliary task used to train a model on unlabeled data, forcing it to learn meaningful representations. The goal is not the pretext task itself, but the features the model learns.

- Downstream Task: The actual task of interest (e.g., image classification, drug toxicity prediction). The model pre-trained on a pretext task is then fine-tuned on this downstream task, often with limited labeled data [9] [10].

What are common types of SSL methods?

| Method Type | Core Principle | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Contrastive Learning | Learns by maximizing agreement between similar data points and distinguishing dissimilar ones [10]. | SimCLR [15], MoCo [9], MolCLR [12] |

| Generative / Autoassociative | Learns by reconstructing or generating parts of the input data [9] [10]. | Autoencoders, BERT (masked language modeling) [9], GPT (next token prediction) [10] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Performance is Poor on the Downstream Task

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient/uninformative pretext task | Evaluate if pretext task requires understanding of data structure relevant to downstream goal. | Design a pretext task that inherently requires learning features useful for your domain (e.g., predicting molecular properties for drug discovery) [14]. |

| Inadequate amount of unlabeled pre-training data | Check if performance improves with more unlabeled data. | Increase the scale and diversity of unlabeled data for pre-training [11] [14]. |

| Negative transfer | Pre-training hurts performance compared to training from scratch. | Ensure the unlabeled pre-training data is relevant to the target domain. The number of pre-training samples matters; too few can be detrimental [11]. |

Problem: Training is Computationally Expensive or Unstable

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Complex model architecture | Profile resource usage (GPU/CPU memory). | Start with simpler, established architectures (e.g., a standard CNN or GNN encoder) before scaling up [14] [12]. |

| Challenging contrastive learning | Loss values are unstable or don't converge. | Use established frameworks like SimCLR or MolCLR. For graph data, use augmentations like atom masking or bond deletion [12]. |

Problem: SSL is Not Improving Anomaly Detection for Tabular Data

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Irrelevant features | Neural network may learn features not useful for detecting anomalies in tabular data [16]. | Consider using the raw data representations or a subspace of the neural network's representation [16]. SSL may not always be the best solution for tabular anomaly detection. |

Experimental Protocols & Performance

The following table summarizes quantitative results from various studies demonstrating SSL's effectiveness in overcoming data scarcity.

| Field / Application | SSL Method | Key Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fatigue Damage Prognostics | Self-supervised pre-training on strain data | Pre-trained models significantly outperformed non-pre-trained models for Remaining Useful Life (RUL) estimation with limited labeled data [11]. | [11] |

| Drug Toxicity Prediction (MolCLR) | Contrastive Learning on Molecular Graphs | Significantly outperformed other ML baselines on the ClinTox and Tox21 databases for predicting drug toxicity and environmental chemical threats [12]. | [12] |

| Biomedical Imaging (UMedPT) | Supervised Multi-Task Pre-training | Matched ImageNet performance on a tissue classification task using only 1% of the original training data with a frozen encoder [13]. | [13] |

| Drug-Drug Interaction (SMR-DDI) | Contrastive Learning on SMILES Strings | Achieved competitive DDI prediction results while training on less data, with performance improving with more diverse pre-training data [14]. | [14] |

Detailed Methodology: MolCLR for Molecular Property Prediction

MolCLR is a framework for improving molecular property prediction using self-supervised learning [12].

- Molecule Representation: Represent each molecule as a graph, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges.

- Graph Augmentation: Create different "views" of the same molecule graph using three augmentation techniques:

- Atom Masking: Randomly remove the features of a subset of atoms.

- Bond Deletion: Randomly remove a subset of chemical bonds.

- Subgraph Removal: Remove a connected subgraph from the molecule (a combination of atom masking and bond deletion).

- Contrastive Pre-training:

- Pass the two augmented views of the same molecule through a Graph Neural Network (GNN) encoder to get two representation vectors.

- The model is trained to recognize that these two different views belong to the same molecule (positive pair) and to distinguish them from representations of other molecules (negative pairs) in the batch.

- This is done by minimizing a contrastive loss function (NT-Xent).

- Downstream Fine-tuning: The pre-trained GNN encoder is then fine-tuned on a smaller, labeled dataset for a specific task, such as predicting drug toxicity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Resource | Function in SSL Research |

|---|---|

| Unlabeled Datasets | The foundational "reagent" for pre-training. Large, diverse, and domain-relevant unlabeled data is crucial for learning generalizable representations [11] [12]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | The encoder architecture of choice when input data is inherently graph-structured, such as molecules [12] or social networks. |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | Standard encoders for image data, used in both contrastive and generative SSL methods [13] [15]. |

| Transformers / BERT | Encoder architecture for sequential data like text (NLP) or SMILES strings representing molecules [9] [14]. |

| Data Augmentation Strategies | Techniques to create positive pairs for contrastive learning. Examples include atom masking for graphs, and rotation/cropping for images [15] [12]. |

SSL Workflow and Contrastive Learning

The following diagrams illustrate the core logical workflows in self-supervised learning.

Diagram 1: Generic SSL Two-Stage Workflow.

Diagram 2: Contrastive Learning (e.g., MolCLR).

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is a pretext task in Self-Supervised Learning, and why is it important? A pretext task is a self-supervised objective designed to learn meaningful data representations without human-provided labels. The model is trained to solve an artificially generated puzzle where the target is derived from the data itself. Examples include predicting an image's rotation angle or reconstructing masked patches. The importance lies in its ability to leverage vast amounts of unlabeled data to learn general-purpose features, which is crucial for overcoming data scarcity in domains like biomedical imaging and prognostics [17] [18].

Q2: My SSL model's performance on the downstream task is poor. What could be wrong? This common issue can stem from several factors related to your pretext task design:

- Misalignment with Downstream Task: The features learned by the pretext task may not be relevant for your final goal. A task like predicting image rotation might not help with tissue classification if it doesn't induce the model to learn distinguishing cellular features [17].

- Insufficient Pre-training Data: The effectiveness of self-supervised pre-training is heavily dependent on the volume and diversity of unlabeled data. Performance gains may be negligible if the pre-training dataset is too small or lacks diversity [19] [13].

- Task Difficulty: Theoretically, the effectiveness of an SSL task is influenced by its difficulty and semantic alignment with the target domain. Simple tasks may not force the model to learn sufficiently complex representations, while overly complex tasks can be difficult to optimize [18] [20].

Q3: Can SSL really match the performance of supervised learning with large labeled datasets? Yes, under the right conditions. Recent research demonstrates that when visual SSL models are scaled up in terms of both model size (e.g., to 7B parameters) and training data (e.g., 2B+ images), they can achieve performance comparable to language-supervised models like CLIP on a wide range of multimodal tasks, including Visual Question Answering (VQA) and OCR, without any language supervision [21] [19].

Q4: How can SSL help with data scarcity in a prognostic task like predicting Remaining Useful Life (RUL)? In Prognostics and Health Management (PHM), labeled run-to-failure data is often scarce. SSL can be applied by first pre-training a model on a large volume of unlabeled sensor data (e.g., strain measurements from structures) using a pretext task. This model learns general representations of the system's degradation process. When this pre-trained model is later fine-tuned on a small labeled dataset for RUL estimation, it significantly outperforms and converges faster than a model trained from scratch [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Negative Transfer During Fine-Tuning

Symptoms: The fine-tuned model performs worse on the downstream task than a model trained without SSL pre-training. Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Low-Quality or Irrelevant Pre-training Data. The unlabeled data used for the pretext task may not share a similar underlying distribution with the target labeled data.

- Solution: Curate the unlabeled dataset to be more domain-relevant. In one study, strategically filtering a large dataset to include only 1.3% of text-rich images dramatically improved performance on OCR-related downstream tasks [19].

- Cause 2: Inadequate Pretext Task. The pretext task may not be forcing the model to learn features useful for your specific downstream task.

- Solution: Design a custom pretext task that is more relevant to the end goal. For instance, in lung adenocarcinoma subtype classification, a pretext task that predicts the spatial relationship between tissue tiles from different magnifications was designed to explicitly teach the model to distinguish tissue structures relevant to the final classification [17].

Problem: SSL Model Fails to Generalize to New Data

Symptoms: The model performs well on its pretext task but the learned features do not transfer well to a new, unseen dataset. Possible Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Lack of Robust and Generalizable Representations. The pretext task may have led to learning shortcuts or superficial features.

- Solution: Increase the diversity of data augmentations used during pre-training and ensure the model capacity is sufficient. Research shows that scaling up both data and model parameters is key to developing robust, generalizable representations that perform well on classic vision benchmarks and complex VQA tasks [19]. Using a multi-task learning strategy that combines various label types (classification, segmentation) during pre-training can also enhance cross-domain transferability [13].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: SSL for Histopathologic Subtype Classification

This protocol outlines the methodology for using custom pretext tasks to classify lung adenocarcinoma subtypes from Whole Slide Images (WSIs) with reduced labeling effort [17].

- Objective: Reduce manual annotation for LUAD histologic subtyping using H&E-stained WSIs.

- Pretext Tasks:

- Spatial Relationship Prediction: Predict the spatial relationship between tiles cropped from lower and higher magnification WSIs.

- Stain Prediction: Predict the eosin stain from the hematoxylin stain to learn cytoplasmic features.

- Downstream Task: Classification of LUAD histologic subtypes.

- Key Findings: The proposed SSL tasks enabled the model to learn distinguishing tissue structures, reducing the need for extensive manual annotation. The ensemble of pretext tasks demonstrated effectiveness compared to other state-of-the-art methods.

Protocol 2: SSL for Fatigue Damage Prognostics

This protocol describes using SSL to improve Remaining Useful Life (RUL) estimation with limited labeled run-to-failure data [11].

- Objective: Improve RUL estimation for aluminum alloy panels subject to fatigue cracks using scarce labeled strain gauge data.

- Pretext Task: Self-supervised pre-training on a large synthetic dataset of unlabeled multivariate strain time-series data from structures before failure.

- Downstream Task: Fine-tuning the pre-trained model on a small labeled dataset of run-to-failure strain data for RUL estimation.

- Key Findings: Models pre-trained in a self-supervised manner significantly outperformed non-pre-trained models in RUL prediction, especially when labeled data was limited. The performance improved with the volume of unlabeled data used for pre-training.

Table 1: Quantitative Results of SSL in Various Domains

| Domain / Application | Key Performance Metric | SSL Model Performance | Baseline / Supervised Performance | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomedical Imaging (Cell Classification) [22] | Balanced Classification Accuracy | Higher accuracy after domain transfer | Lower accuracy for supervised transfer | SSL enables efficient knowledge transfer from bone marrow to peripheral blood cell domains. |

| Biomedical Imaging (CRC Tissue Classification) [13] | F1 Score | 95.4% (with 1% training data, frozen features) | 95.2% (ImageNet, 100% data, fine-tuned) | Matched top performance using only 1% of the original training data without fine-tuning. |

| Prognostics (Fatigue Crack RUL) [11] | RUL Estimation Accuracy | Significantly higher | Lower for non-pre-trained models | SSL pre-training improves RUL prediction with scarce labelled data and less computational expense. |

| Computer Vision (VQA Benchmarks) [19] | Average VQA Performance | Outperformed CLIP at 7B parameters | CLIP performance plateaued | Visual SSL models scale better with model size and data, matching language-supervised models. |

Core Workflow and Mechanism Diagrams

SSL Pre-training and Fine-tuning Workflow

This diagram illustrates the standard two-stage pipeline for applying self-supervised learning to overcome data scarcity.

Pretext Task Mechanisms in SSL

This diagram outlines common mechanisms for constructing pretext tasks in self-supervised learning.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Components for SSL Experiments

| Item / Component | Function in SSL Research | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Unlabeled Dataset (Large-scale) | Serves as the foundational resource for self-supervised pre-training, allowing the model to learn general data representations. | Web-scale image datasets (e.g., MetaCLIP with 2B+ images) for visual representation learning [19]. Unlabeled sensor data (e.g., strain gauge readings) for prognostic models [11]. |

| Pretext Task Formulation | Defines the artificial, self-supervised objective that guides the model to learn meaningful features without human annotation. | Predicting spatial relationships between tissue tiles in histopathology [17]. Predicting future sensor values or masking/reconstruction in time-series data [11]. |

| Data Augmentation Strategies | Creates multiple, varied views of the same data instance, which is crucial for contrastive learning and improving model robustness. | Generating different augmented views of an image for a joint-embedding architecture like DINO [19]. Applying noise or masking to time-series data for a reconstruction task [11]. |

| Multi-Task Learning Framework | Enables simultaneous training on multiple tasks (e.g., classification, segmentation) from different datasets to learn versatile, transferable representations. | Training a universal biomedical model (UMedPT) on 17 tasks with different label types to overcome data scarcity in medical imaging [13]. |

| Hardware Security Module (HSM) | Provides secure, hardware-protected storage for cryptographic private keys, critical for addressing long-term threats like 'Harvest Now, Decrypt Later' in PKI-related SSL. | Protecting private keys for both public and private PKI as an interim step towards quantum-resistant cryptography [23]. |

In many scientific fields, including drug development, a significant bottleneck for applying advanced deep learning techniques is the scarcity of high-quality, labeled data. Self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a powerful paradigm to overcome this challenge by generating supervisory signals directly from unlabeled data, thus reducing or eliminating the dependency on manual annotations [9]. SSL methodologies are broadly categorized into two families: contrastive learning and generative modeling. This guide provides a conceptual and practical overview of these approaches, framed within the context of a research thesis focused on overcoming data limitations.

Conceptual Frameworks: Core Objectives and Mechanisms

What is Contrastive Learning?

Contrastive learning is a machine learning approach where models learn data representations by comparison. The core objective is to learn an embedding space where similar (positive) data pairs are pulled closer together, and dissimilar (negative) pairs are pushed apart [24]. This technique does not require explicit labels; instead, it creates its own supervision by, for example, treating different augmented views of the same data point as a positive pair [24].

What is Generative Modeling?

Generative modeling is a machine learning approach where models learn the underlying probability distribution of the training data to generate new, realistic data instances [24]. The model captures the essence of the observed data and uses this learned representation to synthesize novel examples, such as creating a new image of a horse after being trained on many horse images [24].

Table 1: Core Conceptual Differences Between Contrastive and Generative Approaches

| Aspect | Contrastive Learning | Generative Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Core Objective | Discriminative; learns by differentiating data points [24] | Constructive; aims to model the entire data distribution to generate new data [24] |

| Training Signal | Contrastive loss (e.g., InfoNCE, Triplet Loss) in the representation space [24] | Reconstruction or likelihood loss (e.g., pixel-wise error) in the input space [24] |

| Primary Output | Representations or embeddings for downstream tasks [24] | Synthetic data (e.g., text, images, audio) [24] |

| Typical Architecture | Encoder networks without a decoder [24] | Often includes both encoder and decoder networks (e.g., Autoencoders, GANs) [24] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: A Contrastive Learning Experiment (SimCLR Framework)

The SimCLR (A Simple Framework for Contrastive Learning of Representations) is a seminal protocol for self-supervised image representation learning [24].

Detailed Workflow:

- Data Augmentation (Creating Positive Pairs): For each image in an unlabeled dataset, apply a series of random transformations (e.g., random cropping, flipping, color distortion) twice to create two correlated "views" of the same image. This forms a positive pair [24].

- Encoding: Pass both augmented images through a neural network base encoder (e.g., a ResNet or a simple CNN) to extract representation vectors.

- Projection: Map the representations to a lower-dimensional latent space using a projection head (a small neural network).

- Contrastive Loss Calculation: Use a contrastive loss function, such as the Normalized Temperature-Scaled Cross-Entropy Loss (NT-Xent), to train the network. The loss encourages the model to maximize the similarity between the projections of the positive pair and minimize the similarity with the projections of all other images (negative pairs) in the same batch [24].

Protocol 2: A Generative Learning Experiment (Masked Autoencoding)

Masking is a common self-predictive technique in generative self-supervised learning, used in models like BERT (for language) and Masked Autoencoders (MAE) for vision [9].

Detailed Workflow:

- Data Masking: For each input data sample (e.g., an image or a sentence), randomly obscure a portion of the input. For images, this could mean masking out patches; for text, it means masking out words or tokens.

- Encoding: The remaining, unmasked portion of the data is processed by an encoder network to create a latent representation.

- Decoding and Reconstruction: A decoder network uses this representation to predict the original content of the masked portions.

- Reconstruction Loss Calculation: The model is trained by minimizing the difference between the original data and the reconstructed data (e.g., using Mean Squared Error for images or cross-entropy for text). The original, unmodified data serves as the ground truth [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential "Reagents" for Self-Supervised Learning Experiments

| Item / Concept | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Data Augmentation Pipeline | Generates positive pairs for contrastive learning and robust training for generative models by applying transformations like cropping, noise addition, and masking [24] [9]. |

| Encoder Network (e.g., CNN, ResNet, Transformer) | The core backbone that maps input data to a lower-dimensional representation (embedding). Used in both contrastive and generative paradigms [24]. |

| Projection Head | A small neural network (e.g., MLP) placed on top of the encoder that maps representations to the space where contrastive loss is applied [24]. |

| Decoder Network | Reconstructs the input data from the latent representation generated by the encoder. Essential for generative models like Autoencoders [9]. |

| Contrastive Loss (e.g., NT-Xent, Triplet Loss) | The objective function that quantifies how well the model is distinguishing between similar and dissimilar pairs [24]. |

| Reconstruction Loss (e.g., MSE, Cross-Entropy) | The objective function that quantifies the difference between the original data and the model's reconstruction of it [9]. |

Performance and Quantitative Comparison

The choice between contrastive and generative approaches has measurable implications on data efficiency, computational requirements, and performance on downstream tasks.

Table 3: Quantitative and Performance Comparisons

| Metric | Contrastive Learning | Generative Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Data Efficiency | Often more data-efficient for representation learning; strong performance with limited labeled data after self-supervised pre-training [24] [11]. | Often requires massive amounts of data to faithfully capture the data distribution for high-fidelity generation [24]. |

| Computational Expense | Typically simpler architectures (encoder-only) can be less computationally expensive [24]. | Often requires more complex architectures (encoder-decoder) and can be more computationally intensive [24]. |

| Downstream Task Performance | Excels in classification and retrieval tasks; produces generalizable features that transfer well [24] [25]. | Often excels in link prediction and data generation tasks; can be fine-tuned for classification [25]. |

| Sample RUL Estimation Performance | In one prognostics study, SSL pre-training led to significant RUL prediction improvements with limited data [11]. | Information not covered in search results. |

| Sample Cell Classification Accuracy | An SSL-based pipeline achieved high accuracy on hematological cell classification using only 50 labeled samples per class [22]. | Information not covered in search results. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: I have a very small labeled dataset for a specific task like protein classification. Which SSL approach should I start with?

A: Begin with a contrastive learning approach. Its strength lies in learning powerful, generalizable representations that are highly effective for downstream classification tasks, even when labeled data is scarce [24] [22]. You can pre-train a model on a large, unlabeled corpus of relevant images (e.g., general cellular imagery) and then fine-tune the learned representations on your small labeled dataset.

Q2: My generative model for molecular structure generation is producing blurry or unrealistic outputs. What could be the issue?

A: This is a common challenge. Potential issues and solutions include:

- Problem: Insufficient Model Capacity or Training Time. Generative models often require complex architectures and long training times to capture the intricacies of the data distribution [24].

- Solution: Consider using a more powerful architecture (e.g., Diffusion models, more layers in your VAE/GAN) and ensure you train for a sufficient number of epochs.

- Problem: Mismatched Loss Function. The reconstruction loss (e.g., MSE) might not be well-suited for your data type, leading to averaged, blurry outputs.

- Solution: For images, consider using adversarial loss (GANs) or perceptual loss functions that better capture high-level features.

Q3: How do I create effective positive pairs for contrastive learning on time-series sensor data?

A: The key is to define a meaningful "semantic invariance." For time-series data, positive pairs can be created by:

- Applying random, realistic noise to a signal segment.

- Taking two overlapping windows from the same continuous signal.

- Applying frequency-based augmentations that do not alter the underlying phenomenon being measured.

- Using domain knowledge; for example, in prognostics, data from the same early-stage degradation state could form positive pairs [11].

Q4: What does "negative transfer" mean in the context of SSL pre-training?

A: Negative transfer occurs when pre-training on a dataset does not improve, or even harms, the performance on your downstream task compared to training from scratch [11]. This often happens when the pre-training data (used for the pretext task) is not sufficiently related to the target task's data distribution. The representations learned are not transferable. The solution is to ensure your pre-training data is relevant to your domain.

Q5: Can contrastive and generative approaches be combined?

A: Yes, this is an active and promising research area. Hybrid models are being developed that integrate the strengths of both. For instance, a model might use a generative objective to learn robust representations and a contrastive objective to further refine them for discrimination, leading to superior performance on multiple tasks like node classification, clustering, and link prediction [25].

Why SSL is a Natural Fit for Molecular and Clinical Data

Self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a transformative paradigm for extracting meaningful representations from complex scientific data where labeled examples are scarce or costly to obtain. This is particularly true in molecular and clinical domains, where data is abundant but annotations require expert knowledge. SSL addresses this by leveraging the inherent structure within the data itself to create supervisory signals, bypassing the need for extensive manual labeling. In molecular science, relationships between atoms or genes provide a rich source of self-supervision. In clinical data, temporal relationships in patient records or multi-modal correlations offer similar opportunities. By pre-training on large, unlabeled datasets, models can learn fundamental biological principles, which can then be fine-tuned for specific downstream tasks with minimal labeled data, effectively overcoming the critical bottleneck of data scarcity in biomedical research [26] [22] [27].

Key Concepts and Terminology

- Self-Supervised Learning (SSL): A machine learning paradigm where models generate their own supervisory signals from the structure of unlabeled data, rather than relying on external labels [26].

- Pretext Task: A surrogate task used during initial (pre-)training to help the model learn useful data representations without labeled data. Examples include predicting masked portions of the data or identifying similar and dissimilar pairs [26].

- Fine-Tuning: A subsequent training phase where a model that has been pre-trained using SSL (or other methods) is further trained on a specific, often smaller, labeled dataset for a particular task like cell-type prediction [26].

- Zero-Shot Evaluation: Assessing a model's performance on a task immediately after SSL pre-training, without any task-specific fine-tuning, typically using simple classifiers like k-nearest neighbors [26].

- Transfer Learning: The process of applying knowledge gained from solving one problem (often on a large, general dataset) to a different but related problem (e.g., a specific, smaller dataset) [22].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: In what specific scenarios does SSL provide the most significant benefit for molecular and clinical data? SSL demonstrates the most substantial benefits in specific scenarios [26] [22]:

- Transfer Learning: When you have a small, target dataset for a specific task (e.g., classifying cells from a new study) and you pre-train a model on a large, diverse auxiliary dataset (e.g., a cell atlas with millions of cells). Performance improvements are most pronounced for underrepresented or rare cell types in the target dataset [26].

- Zero-Shot Analysis: When you need to analyze data where high-quality labels are unavailable or difficult to obtain. The rich representations from SSL pre-training can be directly used for tasks like clustering or similarity search without further training [26].

- Domain Adaptation: When applying knowledge from one domain (e.g., bone marrow cell images) to another related domain (e.g., peripheral blood cell images), SSL has been shown to outperform supervised transfer learning [22].

Q2: What are the main types of SSL methods used for this data, and how do I choose? The two primary SSL approaches are Masked Autoencoders and Contrastive Learning [26].

- Masked Autoencoders: The model learns to reconstruct randomly masked or hidden portions of the input data (e.g., a masked gene in expression data). Empirical evidence in single-cell genomics suggests that masked autoencoders often outperform contrastive methods [26].

- Contrastive Learning: The model learns to identify similar (positive) and dissimilar (negative) pairs of data points. Methods like Bootstrap Your Own Latent (BYOL) and Barlow Twins, which avoid negative pairs, have been effectively adapted for scientific data [26].

- Choosing a Method: Start with a masked autoencoder, as it has shown strong performance in domains like single-cell genomics. Contrastive learning can be explored if your task inherently relies on defining similarity between data samples [26].

Q3: My dataset is small and lacks labels. Can SSL still help? Yes, this is precisely where SSL shines. The core strength of SSL is its ability to leverage large, unlabeled datasets to learn generalizable representations. You can pre-train a model on a large public dataset (like the CELLxGENE census) and then fine-tune it on your small, labeled dataset. Research has shown that after SSL pre-training, a lightweight classifier trained on as few as 50 labeled samples per class can achieve performance comparable to or even surpassing supervised models trained from scratch [22].

Q4: What are common pitfalls when implementing SSL for scientific data?

- Insufficient Pre-training Data: The benefits of SSL are unlocked with large and diverse pre-training datasets. Performance gains are marginal if the pre-training data is too small or not representative of the target domain [26].

- Ignoring Inductive Biases: Failing to tailor the pretext task to your data can lead to poor representations. For example, in molecular data, using biologically-informed masking strategies (e.g., masking gene programs) can yield better results than purely random masking [26].

- Incorrect Fine-Tuning: Applying overly aggressive learning rates or fine-tuning for too many epochs can cause "catastrophic forgetting" of the useful representations learned during pre-training.

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor downstream task performance after SSL pre-training. | Pre-training and target domain data are too dissimilar. | Ensure the pre-training dataset is relevant. Increase the diversity of the pre-training data (e.g., more donors, tissues) [26]. |

| Pretext task is not well-suited for the data. | Switch from contrastive to masked autoencoding or vice-versa. For molecular data, try biologically-informed masking [26]. | |

| Model fails to learn meaningful representations during pre-training. | The reconstruction or contrastive loss is not decreasing. | Check data preprocessing and augmentation. For contrastive learning, ensure the augmentations are meaningful for your data type [26]. |

| Model overfits quickly during fine-tuning. | Fine-tuning dataset is very small. | Freeze most of the pre-trained layers and only fine-tune the final layers. Use a very low learning rate for fine-tuning [22]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: SSL for Single-Cell Genomics Data Using a Masked Autoencoder

This protocol is adapted from benchmarks performed on the CELLxGENE dataset [26].

1. Objective: To learn general-purpose representations of single-cell gene expression data that can be transferred to smaller datasets for tasks like cell-type annotation.

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| CELLxGENE Census (scTab Dataset) | A large-scale, diverse single-cell RNA-sequencing dataset used for self-supervised pre-training. Provides the broad biological context [26]. |

| Target Dataset (e.g., PBMC, Tabula Sapiens) | The smaller, specific dataset used for fine-tuning and evaluation to test transfer learning performance [26]. |

| Fully Connected Autoencoder | The neural network architecture. Comprises an encoder that compresses input data and a decoder that reconstructs it. Chosen for its prevalence and simplicity in SCG [26]. |

| Masking Strategy (Random, Gene Programme) | The method for hiding parts of the input data to create the pretext task. Gene programme masking incorporates biological prior knowledge [26]. |

3. Workflow Diagram:

4. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Step 1: Data Preparation. Gather a large-scale, unlabeled single-cell dataset for pre-training (e.g., the scTab dataset with ~20 million cells). For fine-tuning, prepare your smaller, labeled target dataset. Standardize and normalize gene expression values across both datasets [26].

- Step 2: Model Architecture Definition. Construct a fully connected autoencoder network. The input and output layers should match the number of genes (e.g., 19,331 human protein-encoding genes). The encoder bottleneck creates the learned representation [26].

- Step 3: Self-Supervised Pre-training.

- For each batch of data, randomly mask a portion (e.g., 15-30%) of the input gene expression values by setting them to zero.

- Train the autoencoder to reconstruct the original, unmasked input from the masked version.

- The loss function is typically Mean Squared Error (MSE) between the reconstructed and original expression values.

- Save the trained encoder after pre-training is complete [26].

- Step 4: Transfer Learning & Fine-Tuning.

- Take the pre-trained encoder and attach a new, randomly initialized classification head for the downstream task (e.g., cell-type prediction).

- Train the entire model (encoder + classifier) on the labeled target dataset. Use a lower learning rate to avoid overwriting the useful pre-trained weights [26].

- Step 5: Evaluation. Evaluate the fine-tuned model on a held-out test set from the target dataset. Use metrics like Macro F1 score, which is robust to class imbalances [26].

Protocol 2: SSL for Molecular Representation Learning

This protocol synthesizes approaches for learning representations of small molecules and materials, crucial for property prediction and drug discovery [27].

1. Objective: To learn a continuous, meaningful representation of molecular structure that encodes chemical properties and can be used for various downstream tasks.

2. Research Reagent Solutions:

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Unlabeled Molecular Dataset (e.g., ZINC, QM9) | A large database of molecular structures (e.g., as SMILES strings or graphs) without property labels, used for pre-training [27]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | The primary neural network architecture for processing molecules represented as graphs, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges [27]. |

| 3D Molecular Geometry Data | Provides spatial atomic coordinates, which can be used in the pretext task to learn representations that are aware of molecular shape and conformation [27]. |

| Pretext Task (e.g., 3D Infomax, Attribute Masking) | A task that leverages unlabeled data. 3D Infomax maximizes mutual information between 2D graph and 3D geometry representations [27]. |

3. Workflow Diagram:

4. Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Step 1: Molecular Representation. Choose an initial molecular representation. Graph-based representations (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges) are highly effective. SMILES strings are also common [27].

- Step 2: Pretext Task Selection.

- Attribute Masking: Randomly mask atom or bond features in the molecular graph and train a GNN to predict the masked attributes. This forces the model to learn the context of the local chemical environment [27].

- 3D-2D Consistency (3D Infomax): If 3D structural data is available, train the model to maximize mutual information between the representation of a 2D graph and its corresponding 3D geometry. This encourages the 2D representation to capture 3D structural information [27].

- Step 3: Pre-training. Execute the chosen pretext task on the large, unlabeled molecular database.

- Step 4: Downstream Application. Use the pre-trained GNN encoder for supervised tasks like predicting solubility, toxicity, or binding affinity by adding a task-specific output layer and fine-tuning on a smaller, labeled dataset [27].

Quantitative Results and Performance Benchmarks

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from published research on SSL for scientific data, providing a baseline for expected performance.

Table 1: SSL for Single-Cell Genomics - Cell-Type Prediction Performance (Macro F1 Score) [26]

| Target Dataset | Supervised Baseline (No Pre-training) | With SSL Pre-training on scTab | Key Improvement Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBMC Dataset | 0.7013 ± 0.0077 | 0.7466 ± 0.0057 | Significant improvement for underrepresented cell types. |

| Tabula Sapiens Atlas | 0.2722 ± 0.0123 | 0.3085 ± 0.0040 | Correctly classified ~6,881 type II pneumocytes vs. ~2,441 baseline. |

Table 2: SSL for Hematological Cell Image Classification (Balanced Accuracy) [22]

| Experiment Setup | Supervised Deep Learning | Self-Supervised Learning |

|---|---|---|

| Direct transfer from bone marrow to peripheral blood data | Lower performance | Higher performance in all tested blood datasets |

| After adaptation with 50 labeled samples/class | Baseline for comparison | Surpasses supervised performance for rare/atypical cell types |

Implementing SSL for Drug Discovery: From Molecules to Clinical Outcomes

FAQs: Self-Supervised Learning for Molecular Representation

1. What is Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) in molecular science, and why is it important? Self-supervised learning is a technique that overcomes data scarcity by pre-training models on large amounts of unlabeled molecular data before fine-tuning them for specific property prediction tasks. This is crucial in drug discovery because obtaining labeled molecular property data is expensive and time-consuming, while massive databases of unlabeled molecules are readily available. SSL frameworks learn comprehensive molecular representations by solving designed "pretext" tasks, allowing them to capture essential chemical information without manual labeling [28] [29].

2. What are the main molecular representations used in SSL? The two primary representations are:

- SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System): A string-based representation that uses ASCII characters to denote molecular structures [29].

- Molecular Graphs: A 2D representation where atoms are nodes and chemical bonds are edges, preserving the molecule's topological structure [28] [29]. Advanced SSL methods often combine both representations to learn more robust and informative features [29].

3. What are common SSL frameworks for molecular property prediction?

- HiMol (Hierarchical Molecular Graph Self-Supervised Learning): Introduces a hierarchical GNN to encode node-motif-graph level information and uses multi-level self-supervised pre-training tasks [28].

- TGSS (Triple Generative Self-Supervised Learning): Uses three encoders (BiLSTM, Transformer, GAT) to learn from molecular sequences and graph structures, employing a generative approach for pre-training [29].

- Motif-based Methods: Learn and leverage frequently occurring molecular substructures (motifs) to enhance representation learning [28] [29].

4. What are typical challenges when implementing molecular SSL?

- Fusing Heterogeneous Information: Effectively combining sequence (SMILES) and graph-based representations [29].

- Model Architecture Selection: Choosing and integrating multiple encoders and decoders for generative or contrastive learning [29].

- Feature Fusion: Balancing and weighting different molecular features from various models in downstream tasks [29].

- Chemical Structure Preservation: Ensuring augmentations or graph modifications do not destroy meaningful chemical properties [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Performance on Downstream Molecular Property Prediction Tasks

Problem: After pre-training, your SSL model does not perform well on fine-tuned molecular property prediction.

| Potential Cause | Solution Approach | Relevant Framework |

|---|---|---|

| Limited perspective from single molecular representation | Adopt a multi-view SSL framework that integrates both SMILES and molecular graph representations [29]. | TGSS [29] |

| Ignored molecular motifs (functional groups) | Implement a hierarchical model that explicitly incorporates motif-level structures [28]. | HiMol [28] |

| Ineffective feature fusion from multiple encoders | Use an attention-based feature fusion module to assign different weights to features from various encoders [29]. | TGSS [29] |

| Incorrect dataset splitting leading to overoptimistic results | Use scaffold splitting for dataset division, which groups molecules by their core structure for a more challenging test [29]. | General Best Practice |

Issue 2: Model Fails to Capture Essential Chemical Structural Information

Problem: Your model does not adequately learn meaningful chemical semantics or properties.

Solution: Implement a hierarchical graph neural network with motif incorporation.

- Step 1: Decompose the molecular graph into motifs using chemically valid rules (e.g., improved BRICS rules that break large ring fragments into minimum rings) [28].

- Step 2: Construct a hierarchical graph by incorporating motif nodes and a graph-level node. Connect atoms to their containing motifs, and all motifs to the graph-level node [28].

- Step 3: Use a GNN to encode this augmented structure, enabling information flow between atoms, motifs, and the entire molecule [28].

Experimental Protocol (HiMol Framework):

- Input Transformation: Convert SMILES to a molecular graph using RDKIT [28].

- Motif Decomposition: Apply decomposition rules to identify molecular motifs [28].

- Graph Augmentation: Add motif nodes and a graph-level node to the original graph with appropriate edges [28].

- Pre-training: Train the Hierarchical Molecular Graph Neural Network using multi-level self-supervised tasks [28].

- Fine-tuning: Transfer pre-trained weights to downstream tasks and update with a 2-layer MLP for property prediction [28].

Issue 3: Inefficient Multi-Model Fusion for Downstream Tasks

Problem: After pre-training multiple encoders, the model fails to effectively integrate their features for final prediction.

Solution: Implement a weighted feature fusion module.

- Step 1: Pre-train multiple encoders (e.g., BiLSTM for SMILES sequences, Transformer for SMILES, and GAT for molecular graphs) using generative self-supervised learning [29].

- Step 2: For downstream tasks, extract features from all pre-trained encoders [29].

- Step 3: Use an attention mechanism to learn the importance weights for each feature type and compute a weighted combination [29].

- Step 4: Pass the fused feature representation to the final prediction layer [29].

Comparative Table: Key SSL Frameworks for Molecular Representation

| Framework | Core Methodology | Molecular Representations | Pre-training Tasks | Reported Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HiMol [28] | Hierarchical GNN with motif and graph nodes | Molecular Graphs | Multi-level: Generative (atom/bond) and Predictive (molecule) | Captures chemical semantics; Outperforms SOTA on classification/regression tasks [28] |

| TGSS [29] | Triple generative model with feature fusion | SMILES & Molecular Graphs | Feature reconstruction between three encoders | Improves accuracy by fusing heterogeneous molecular information [29] |

| Motif-based [28] | Motif discovery and subgraph sampling | Molecular Graphs | Contrastive learning between graphs and subgraphs | Learns informative molecular substructures without destroying chemistry [28] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Computational Materials

| Item / Resource | Function in Molecular SSL |

|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database [29] | Large-scale source of unlabeled bioactive molecules for SSL pre-training. |

| MoleculeNet [28] [29] | Benchmark collection of datasets for evaluating molecular property prediction tasks. |

| RDKIT [28] | Cheminformatics library used to convert SMILES strings into molecular graph representations. |

| BRICS [28] | Algorithm for decomposing molecules into meaningful, chemically valid motifs or fragments. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [28] | Primary backbone architecture for encoding molecular graph representations. |

| Transformer & BiLSTM [29] | Encoder architectures for processing string-based SMILES representations. |

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) [29] | Used in generative SSL frameworks for reconstructing molecular features. |

Experimental Workflows & System Diagrams

HiMol Framework Architecture

Multi-View SSL with Feature Fusion

Molecular Graph Hierarchical Encoding

Application in Small Molecule and Peptide Drug Discovery

Troubleshooting Guide: Self-Supervised Learning for Drug Discovery

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when implementing self-supervised learning (SSL) to overcome data scarcity in small molecule and peptide drug discovery.

Table 1: Common SSL Implementation Challenges and Solutions

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Quality & Quantity | Poor model generalization to new molecular scaffolds. | Insufficient or low-quality unlabeled data for pre-training; data biases. | Increase diversity of unlabeled pre-training dataset; use data augmentation techniques like virtual masking for graphs [30]. |

| Negative transfer (pre-training hurts performance). | Pre-training and downstream tasks are not sufficiently related; too few pre-training samples [11]. | Ensure pretext task is aligned with the downstream goal; use adequate volume of unlabeled data for pre-training [11]. | |

| Model Performance | Low accuracy on rare or atypical cell types or molecular structures. | Standard supervised models fail with limited labeled examples. | Implement an SSL feature extraction pipeline; fine-tune with a lightweight classifier on small labeled datasets [22]. |

| Inability to capture temporal or structural graph features. | Standard GNNs ignore dynamic graph evolution. | Use temporal graph contrastive learning frameworks (e.g., DySubC) that sample time-weighted subgraphs [31]. | |

| Technical Implementation | High computational resource demands. | Complex model architecture and large datasets. | Leverage SSL pre-training to reduce computational expense for the downstream fine-tuning task [32] [11]. |

| Model interpretability challenges. | "Black-box" nature of deep learning models. | Employ interpretability techniques; start with simpler models to establish a baseline. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of self-supervised learning in drug discovery? SSL addresses the critical bottleneck of data scarcity by allowing models to first learn meaningful representations and general patterns from large amounts of unlabeled data (e.g., molecular structures, sensor readings). This pre-trained model can then be fine-tuned for specific downstream tasks (e.g., binding affinity prediction) with very limited labeled data, leading to better performance and reduced reliance on expensive, hard-to-acquire labeled datasets [33] [11] [22].

Q2: My SSL model isn't performing well after fine-tuning. What should I check? First, verify the alignment between your pretext task (used in pre-training) and your downstream task. If they are unrelated, pre-training may not help. Second, ensure you used a sufficient volume and diversity of unlabeled data during pre-training. Using only a small number of unlabeled samples can result in no improvement or even negative transfer, reducing performance [11]. Finally, check the quality of your small labeled dataset for fine-tuning.

Q3: How can SSL be applied specifically to molecular and peptide data? Molecular structures can be naturally represented as graphs (atoms as nodes, bonds as edges). SSL methods like graph contrastive learning can pre-train models on these unlabeled molecular graphs. For instance, you can generate two augmented views of a molecule and train a model to recognize that they are from the same source, helping it learn robust structural representations. This is powerful for tasks like property prediction later on [30] [31]. For peptides, SSL can be used to learn from sequences or structural data without needing labeled activity data [33].

Q4: Can SSL help with knowledge transfer between different biological domains? Yes. Research has shown that an SSL model pre-trained on one domain, such as bone marrow cell images, can learn representations that transfer effectively to a different but related domain, like peripheral blood cell images, outperforming supervised learning models in such scenarios [22].

Experimental Protocol: SSL for Molecular Property Prediction

This protocol outlines a methodology for using self-supervised learning to predict molecular properties with limited labeled data.

Workflow Overview

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Protocols

| Item | Function / Role in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| Unlabeled Molecular Dataset (e.g., from public repositories) | Serves as the primary source for self-supervised pre-training, allowing the model to learn general chemical representations without labels [11]. |

| Labeled Dataset (Small, task-specific) | Used for the supervised fine-tuning phase to adapt the pre-trained model to a specific predictive task like binding affinity or toxicity [22]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) Encoder | The core model architecture that processes molecular graphs and generates numerical representations (embeddings) of molecules [34]. |

| Data Augmentation Function | Creates modified versions of input data (e.g., masked molecular graphs) to form positive pairs for contrastive learning, teaching the model invariant features [30]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Collection and Preparation:

- Unlabeled Data: Assemble a large, diverse set of molecular structures (e.g., in SMILES string or graph format). This dataset should be relevant to the general problem domain but requires no activity or property labels [33] [34].

- Labeled Data: Prepare a smaller dataset of molecules with accurate labels for the target property (e.g., IC50, solubility). This will be used for fine-tuning.

Pre-training Phase (Self-Supervised):

- Pretext Task Design: Employ a contrastive learning framework. For each molecule in the unlabeled set, use a virtual masking augmentation (VMA) technique [30] or other methods to generate two correlated "views" without altering the original graph structure.

- Model Training: Train a GNN encoder. The objective is to maximize the agreement (similarity) between the representations of the two augmented views of the same molecule while distinguishing them from views of different molecules (negative samples). This forces the model to learn meaningful, general-purpose molecular representations.

Fine-tuning Phase (Supervised):

- Model Initialization: Take the pre-trained GNN encoder from the previous step.

- Task-Specific Training: Add a new prediction head (a few neural network layers) on top of the encoder. Train the entire model on the small, labeled dataset. The model now uses its general knowledge of chemistry to learn the specific property task efficiently.

Validation:

- Evaluate the fine-tuned model on a held-out test set of labeled molecules and compare its performance against a model trained from scratch without SSL pre-training.

Molecular Representation Learning via Graph Contrast

This section details the technical core of many SSL methods for molecules.

Technical Diagram: Graph Contrastive Learning Pipeline

Advancing Antibody Design and Vaccine Development with SSL

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How can Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) address the challenge of limited labeled data in antibody design? A1: SSL overcomes data scarcity by leveraging vast amounts of unlabeled data for model training. It pre-trains models on unlabeled molecular data to learn fundamental biochemical principles and representations. This pre-trained model can then be fine-tuned on smaller, labeled datasets for specific tasks like predicting antibody-antigen binding affinity, effectively transferring the generalized knowledge. This approach has shown considerable advantages over traditional supervised learning that relies entirely on scarce labeled data [33] [35].

Q2: What types of molecular representations are most effective for SSL in this domain? A2: Multiple representation types are used, often in combination:

- Graph-based representations explicitly encode atoms as nodes and bonds as edges, capturing structural relationships. They are the backbone for Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [27].

- Sequence-based representations, like SMILES strings for small molecules or amino acid sequences for proteins, allow the application of NLP-inspired SSL models like BERT [33] [27].

- 3D-aware representations capture spatial geometry and are critical for modeling molecular interactions. Methods like 3D Infomax use 3D geometries to enhance GNN predictions [27].

- Hybrid/multi-modal representations integrate graphs, sequences, and quantum descriptors to create more comprehensive molecular embeddings [27].

Q3: Our team is seeing poor generalization of models from in-silico predictions to experimental results. How can SSL help? A3: Poor generalization often stems from models learning superficial patterns in limited training data. SSL mitigates this by:

- Learning robust, transferable features from large, diverse unlabeled datasets.

- Using contrastive learning frameworks that make models invariant to semantically irrelevant perturbations (e.g., small rotations in a 3D structure) while preserving critical biological information [33].

- Incorporating physics-informed neural potentials and equivariant models that embed physical laws (like rotational invariance) directly into the architecture, leading to more physically consistent and generalizable predictions [27].

Q4: What are the best practices for pre-training a transformer model on protein sequences for vaccine antigen design? A4: A knowledge-guided pre-training strategy is recommended.

- Pre-training: Use a masked language modeling objective on a large, diverse corpus of protein sequences (e.g., from public databases) to teach the model fundamental protein grammar [33].

- Knowledge-Guided Fine-tuning: Further train the model on tasks informed by domain knowledge, such as predicting protein functions or stability, to steer the learned representations toward biologically relevant features [27].

- Task-Specific Fine-tuning: Finally, fine-tune the model on your specific task, such as predicting immunogenicity or identifying conserved epitopes for a broad-spectrum vaccine [33].

Q5: Are there specific SSL techniques useful for optimizing Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs)? A5: Yes, SSL can optimize key ADC components:

- Conjugation Sites: Graph-based SSL models can learn from unlabeled 3D antibody structures to predict optimal conjugation sites that do not impair antigen binding [36].

- Payload & Linker Properties: SSL models pre-trained on massive chemical compound libraries can generate novel cytotoxic payloads or predict linker stability, helping to design ADCs with improved potency and pharmacokinetics [36].

- Developability: SSL can help predict aggregation-prone regions and other developability parameters from sequence or structure, de-risking ADC candidates early in development [36].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Performance is Saturated or Declining During Pre-training

- Potential Cause 1: Poor quality or lack of diversity in the unlabeled pre-training data.

- Solution: Curate a larger, more diverse, and clean dataset. For antibodies, ensure coverage of different subtypes and species. For vaccines, include sequences from multiple pathogen strains [35].

- Potential Cause 2: Ineffective pre-training task or objective.

- Solution: Re-evaluate the self-supervised objective. For graphs, try contrastive learning between different augmented views of the same molecule. For sequences, consider next-sentence prediction or permutation-based tasks in addition to masking [33].

- Potential Cause 3: Architecture is not suited for the data modality.

Problem: High Computational Resource Demand During Model Training

- Potential Cause 1: The model architecture is too large for the available resources.

- Solution: Start with a smaller model or use techniques like gradient checkpointing and mixed-precision training. Consider using pre-trained models from public repositories as a starting point to reduce training time [33].

- Potential Cause 2: Inefficient data loading or preprocessing.

- Solution: Implement optimized data pipelines that preprocess data in parallel and use data formats optimized for fast reading [27].

Problem: Fine-tuned Model Fails to Predict Experimental Vaccine Efficacy

- Potential Cause 1: Domain shift between pre-training data and the fine-tuning task.

- Solution: Incorporate data that bridges the domain gap during fine-tuning. For vaccine design, this could involve using data from immunological assays or leveraging established Correlates of Protection (CoPs), like neutralizing antibody titers, as targets for the model [37].

- Potential Cause 2: The model has learned shortcuts not relevant to real-world efficacy.

- Solution: Improve the interpretability of the model to understand its decision-making process. Use attention mechanisms or saliency maps to see which parts of the antigen the model is focusing on and validate this against known biological knowledge [27].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Key Self-Supervised Learning Methods in Drug Discovery

| Method Category | Core Principle | Example Applications in Antibodies/Vaccines |

|---|---|---|

| Contrastive Learning [33] | Learns representations by maximizing agreement between differently augmented views of the same data and distinguishing them from other data points. | Enhancing feature extraction in anticancer peptides; creating invariant representations for 3D molecular structures [33]. |

| Generative Learning [33] [27] | Learns to model the underlying data distribution to generate new data or reconstruct masked inputs. | De novo generation of novel antibody sequences; generating molecular graphs with desired properties [27]. |

| Masked Modeling [33] | Randomly masks parts of the input data (e.g., atoms in a graph, residues in a sequence) and trains the model to predict them. | Pre-training protein language models on millions of unlabeled sequences; learning context-aware representations of molecules [33]. |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in SSL-Driven Research |

|---|---|

| Monoclonal Antibodies (mAbs) [38] | Used as therapeutic candidates or as tools to validate AI-predived epitopes and binding profiles. Critical for experimental validation of in-silico designs. |

| Recombinant Antigens [39] | Essential for high-throughput screening of AI-generated vaccine candidates and for measuring immune responses (e.g., in ELISA). |

| Adjuvants (e.g., AdjuPhos) [40] | Used in preclinical vaccine studies to enhance the immune response to AI-designed antigen constructs, helping to evaluate their real-world efficacy. |

| mRNA Vectors [39] | Delivery vehicle for mRNA vaccines and for in vivo expression of AI-designed proteins, such as monoclonal antibodies encoded by mRNA [38]. |

Detailed Methodology: SSL for Multi-Antigen Vaccine Design (Based on PolySSL Study [40])

Objective: To refine a fusion vaccine containing multiple Staphylococcal Superantigen-Like (SSL) proteins using a data-driven approach that could be enhanced by SSL.

Antigen Selection & Construct Design:

- Select multiple target antigens (e.g., SSL3, SSL7, SSL11) common across pathogen strains.

- Generate several polyprotein fusion constructs by combining genes for the selected antigens in different orders (e.g., PolySSL 3711, 7113, 7311).

In-silico Analysis (Area for SSL Application):

- SSL Pre-training: Pre-train a protein language model on a large, unlabeled database of bacterial and human proteins.

- Immunogenicity Prediction: Fine-tune the pre-trained model to predict key immunogenic regions (epitopes) and protein stability for each construct variant.

- Construct Ranking: Rank the designed constructs based on the predicted immunogenicity and stability scores before moving to costly synthesis and in-vivo experiments.

Experimental Validation:

- Immunization: Administer the top-ranked vaccine constructs (e.g., PolySSL7113) to animal models (e.g., mice) with an appropriate adjuvant (e.g., AdjuPhos).

- Humoral Response Assay: Measure antigen-specific serum IgG responses using ELISA. The study showed endpoint titers could reach ≥10⁵ for dominant antigens like SSL7 [40].

- Functional Assays: Perform neutralization assays (e.g., testing if antibodies block SSL7 interaction with IgA or C5) and challenge models to assess reduction in bacterial burden in organs.

Iterative Refinement:

- Use the experimental results (IgG titers, neutralization efficacy) as labeled data to further refine the SSL model, creating a closed-loop design and optimization cycle.

Workflow Visualizations

SSL Model Development Workflow

Multi-Antigen Vaccine Design Pipeline

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Model Generalization to New Data

Problem: Your self-supervised learning (SSL) model, trained on bone marrow cell data, shows a significant drop in performance when applied to peripheral blood smears from a different laboratory.

Explanation: This is a classic domain shift problem. Differences in staining protocols, microscope settings, and patient demographics between labs create variations that models trained only on supervised learning struggle to handle. SSL excels here because it learns fundamental morphological features during pre-training, making it more robust to such technical variations [41].

Solution:

- Leverage Pre-trained Features: Use a feature extractor pre-trained with SSL on a large, diverse set of unlabeled hematological images. This provides a strong foundation of general cell morphology [13].

- Lightweight Classifier Fine-tuning: Keep the SSL backbone frozen and only train a small, lightweight classifier (e.g., a linear layer or small MLP) on a small set of labeled data (e.g., 50 samples per class) from the new domain. This adapts the model to the new cell types without forgetting the general features [41].

- Data Augmentation: Apply extensive, realistic augmentations during the fine-tuning of the classifier. This includes color jitter (to simulate staining variations), random rotations, and slight elastic deformations.

Verification: After adaptation, the model's balanced accuracy on the new peripheral blood dataset should be higher than that of a model trained from scratch or transferred from a supervised learning model [22].

Training Instability with Limited Labeled Data