Optimizing qPCR for Minimal Residual Disease Detection: Protocols, Pitfalls, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing quantitative PCR (qPCR) for minimal residual disease (MRD) detection.

Optimizing qPCR for Minimal Residual Disease Detection: Protocols, Pitfalls, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing quantitative PCR (qPCR) for minimal residual disease (MRD) detection. It covers the foundational principles of MRD as a critical prognostic marker in hematologic malignancies, details robust methodological workflows including sample handling and the comparative ΔΔCt method, and addresses key challenges such as inhibitor management and reference gene validation. Furthermore, it evaluates the performance of qPCR against emerging next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies, emphasizing the importance of adhering to MIQE guidelines for rigor and reproducibility in clinical and research settings.

Understanding Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) and the Role of qPCR

Measurable residual disease (MRD), also referred to as minimal residual disease, represents the small population of cancer cells that persist in patients after treatment, typically at levels below the detection limit of conventional morphological microscopy (which has a sensitivity of only 1-5%) [1] [2]. In patients who have achieved complete remission (CR), MRD originates from resistant tumor cells that may eventually lead to disease relapse [1] [2]. The clinical significance of MRD monitoring has been firmly established in hematological malignancies and is increasingly being explored in solid tumors [3].

MRD testing provides a powerful tool for risk stratification, prognosis prediction, and therapeutic decision-making. Patients with undetectable MRD or favorable MRD responses consistently demonstrate lower relapse risk and better survival outcomes compared to those with MRD positivity [1]. This application note details the clinical significance of MRD across cancer types and provides detailed methodological protocols for its detection, with particular emphasis on qPCR-based approaches within the broader context of MRD research.

MRD Detection Methods and Performance Characteristics

Multiple technologies with varying sensitivities and applications have been developed for MRD detection. The choice of method depends on cancer type, available biomarkers, required sensitivity, and laboratory capabilities.

Table 1: Comparison of Major MRD Detection Technologies

| Method | Applicability | Sensitivity | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiparameter Flow Cytometry (MFC) | Nearly 100% for acute leukemia [2] | 10-3 to 10-5 [1] | Fast (hours); wide applicability; relatively inexpensive [1] [2] | Lack of standardization; fresh cells required; phenotypic changes [1] [2] |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | 40-50% [2] | 10-4 to 10-6 [2] | High sensitivity; standardized; lower costs [2] | Only one gene assessed per assay [2] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | >95% [2] | 10-2 to 10-6 [2] | Multiple genes analyzed simultaneously; broad applicability [2] | High cost; complex data analysis; not yet standardized [2] |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) | Information missing | Information missing | Absolute quantification without standard curves; high sensitivity | Limited multiplexing capability; not covered in sources |

| Karyotyping | ~50% [2] | 5×10-2 [2] | Widely used; standardized [2] | Slow; labor-intensive; low sensitivity [2] |

Method Selection Considerations

The optimal MRD detection method varies by clinical context. For acute leukemias, flow cytometry approaches include Leukemia-Associated ImmunoPhenotype (LAIP) and "Different from Normal" (DFN) strategies [1]. Molecular methods like qPCR and NGS are preferred when specific genetic biomarkers are available, such as fusion transcripts (e.g., BCR::ABL1 in CML) or clonal immunoglobulin/T-cell receptor rearrangements [1] [3]. The European LeukemiaNet recommends using highly sensitive methods with detection limits of at least 10-4 for MRD assessment in AML [4].

Clinical Significance of MRD Testing

Prognostic Value Across Malignancies

MRD status represents the strongest independent prognostic factor in acute leukemia, outperforming conventional risk stratification based on disease biology alone [1] [4]. The predictive power of MRD testing has been quantified in recent large-scale analyses.

Table 2: Predictive Value of MRD Testing for Relapse Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Category | Odds Ratio for Relapse (MRD+ vs MRD-) | 95% Confidence Interval | Common Assays | Typical Time Points |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Hematological Cancers | 3.5 | [2.3, 5.4] [3] | MPFC, PCR [3] | Post-induction, pre-transplant [3] |

| Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) | 4.7 | [2.6, 8.6] [3] | MPFC, NGS [3] | After consolidation [3] |

| Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) | 2.5 | [1.3, 4.5] [3] | MPFC, IG/TCR PCR [3] | Early treatment (e.g., day 8) [1] |

| Solid Cancers | 9.1 | [3.3, 24.9] [3] | ctDNA NGS [3] | Post-resection [3] |

The higher odds ratio in solid cancers may reflect that MRD detection in blood implies established metastatic capability [3]. In hematologic malignancies, MRD assessment times vary by disease: in B-cell ALL, early assessment during induction (e.g., day 8) can evaluate leukemia clearance kinetics, while post-consolidation and pre-transplant timepoints provide strong prognostic information [1] [3].

Clinical Applications

Risk Stratification and Treatment Guidance

MRD monitoring enables dynamic risk assessment that can overcome limitations of initial risk stratification. In AML, MRD status can supersede pre-treatment prognostic stratification based on disease biology [4]. This allows for risk-adapted therapy approaches, where MRD-positive patients may receive intensified treatment (e.g., allogeneic stem cell transplantation) while MRD-negative patients may be spared excessive toxicity [1] [2].

Surrogate Endpoint and Drug Development

MRD has emerged as a surrogate endpoint in clinical trials, accelerating the testing and approval process for novel therapeutics [1]. MRD response can provide early evidence of drug efficacy before overall survival data mature, particularly valuable in slow-progressing diseases.

Early Relapse Detection and Monitoring

Serial MRD monitoring can detect molecular relapse weeks to months before clinical manifestation, creating a therapeutic window for early intervention [1]. In CML, rising BCR::ABL1 levels trigger intervention before hematologic relapse occurs [3].

MRD in Solid Tumors: Emerging Applications

While MRD testing is most established in hematologic malignancies, the concept is rapidly expanding to solid tumors using circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis. In solid cancers, MRD assessment typically occurs after surgical resection of localized disease, unlike the remission monitoring approach used in hematologic cancers [3].

Recent studies demonstrate that ctDNA-based MRD detection post-resection predicts recurrence with high accuracy in colorectal, breast, and other solid tumors [3]. The technical approach differs, focusing primarily on identifying cancer-related mutations in blood rather than cellular immunophenotypes or fusion transcripts [3].

In neuroblastoma, a pediatric solid tumor, multimodal approaches combining automatic immunofluorescence plus interphase FISH (AIPF) with RT-qPCR panels have significantly improved MRD detection compared to standard morphological assessment [5]. These techniques also enable monitoring of therapeutic targets like GD2 expression and tumor cell plasticity between adrenergic and mesenchymal states [5].

Experimental Protocols for MRD Detection

qPCR-Based MRD Detection Protocol

Sample Preparation and Nucleic Acid Extraction

Bone Marrow Aspirate Collection:

- Collect bone marrow aspirate (first pull, <5 mL) into EDTA or sodium heparin tubes [1]

- Process within 48 hours of collection; transport at room temperature [1]

- For RNA extraction, preserve samples in Trizol or PAXgene blood RNA tubes within 24 hours [5]

Cell-Free DNA Extraction:

- Use cell-free DNA blood collection tubes (e.g., Streck) [6]

- Extract cfDNA using specialized kits (e.g., QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit) [6]

- Quantify yield with fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit Fluorometer) [6]

- Assess quality with PreSeq DNA QC Assay or similar quality control measures [6]

Reverse Transcription and qPCR Setup

Reverse Transcription:

- Use high-temperature reverse transcriptase for structured RNA regions [7]

- Employ random hexamers and/or gene-specific primers

- Use ReadyScript cDNA Synthesis Mix or equivalent systems [7]

qPCR Reaction Components:

- Template: 100 pg gDNA or cDNA equivalent [7]

- Primers: Optimized concentration to minimize dimer formation [7]

- dNTPs: Standard mix or dUTP/UNG system for contamination control [7]

- MgCl2: 3-6 mM final concentration (optimize for each assay) [7]

- Taq DNA Polymerase: Use "hot-start" versions to reduce non-specific amplification [7]

- Reference dye: ROX or similar for signal normalization where required [7]

Thermal Cycling Conditions:

- UNG incubation (if using dUTP): 50°C for 2 minutes

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2-10 minutes

- Amplification (40-45 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15-30 seconds

- Annealing: Primer-specific temperature (55-65°C) for 30-60 seconds

- Extension: 72°C for 30-60 seconds

- Melting curve analysis (for SYBR Green): 65°C to 95°C with continuous fluorescence monitoring [7]

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Quantification Methods:

- Absolute Quantification: Use external standards with identical primer binding sites to target sequence [7]

- Relative Quantification: Calculate target template ratio to reference gene (e.g., GAPDH, ABL1) [7]

Quality Control:

- Include no-template controls in each run

- Ensure PCR efficiency of 90-110%

- Maintain correlation coefficient (R2) >0.98 for standard curves

- A260/A280 ratio of 1.8-2.0 for DNA purity assessment [7]

Next-Generation Sequencing Protocol for MRD

Library Preparation and Sequencing

Library Preparation:

- Use targeted gene panels (e.g., VariantPlex Core AML, ArcherDx) [6]

- Incorporate molecular barcodes for error correction

- Amplify libraries with appropriate cycle number

Sequencing:

- Platform: Illumina MiSeq or NextSeq systems [6]

- Read length: 150 bp paired-end [6]

- Minimum reads: 0.75-3×106 depending on panel size [6]

Bioinformatic Analysis

Variant Calling:

- Use dedicated pipelines (e.g., Archer Analysis) with error correction enabled [6]

- Set minimum depth threshold (e.g., 500-1000× for sensitivity to 0.1% VAF)

- Manually review mutations previously identified by routine diagnostics [6]

Variant Annotation:

- Cross-reference with clinical databases (COSMIC, ClinVar) [6]

- Apply computational prediction algorithms (FATHMM, PolyPhen2, PROVEAN, SIFT) [6]

- Filter for pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants only [6]

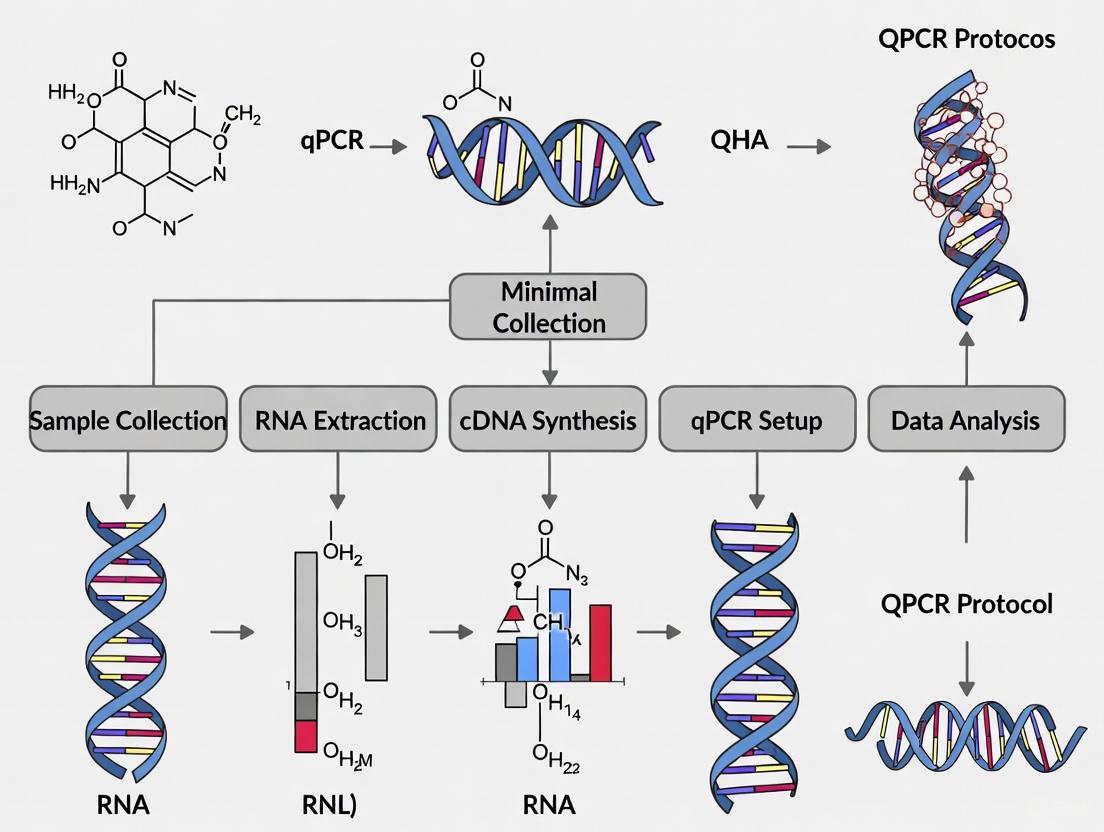

Visualization of MRD Testing Workflow

MRD Testing Workflow: From Sample to Clinical Application

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MRD Detection

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Stabilization | PAXgene Blood RNA Tubes, Streck cfDNA BCT | Preserves sample integrity during transport | PAXgene for RNA/DNA; Streck for cell-free DNA [6] [5] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit, Trizol-based methods | Isolation of high-quality nucleic acids | QIAamp optimized for cfDNA; Trizol for RNA [6] [5] |

| Reverse Transcription | ReadyScript cDNA Synthesis Mix, High-temperature RT enzymes | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates | High-temperature enzymes for structured RNAs [7] |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR Green, TaqMan probes, UNG-containing systems | Amplification and detection of targets | SYBR Green for melting curve; TaqMan for specificity [7] |

| Targeted Gene Panels | VariantPlex Core AML, Core Myeloid panels | NGS-based mutation detection | 10-37 gene panels cover common mutations [6] |

| Reference Genes | ABL1, GAPDH, β-actin | Normalization of qPCR data | ABL1 preferred in hematologic malignancies [7] |

| Quality Control Assays | PreSeq DNA QC Assay, Qubit assays, Bioanalyzer | Assess nucleic acid quantity/quality | Essential for reliable MRD detection [6] |

MRD testing represents a transformative approach in oncology, enabling前所未有的 sensitive monitoring of treatment response and disease recurrence across hematological malignancies and solid tumors. The clinical utility of MRD assessment is well-established for risk stratification, treatment guidance, and as a surrogate endpoint in drug development.

qPCR-based methods provide a robust, sensitive, and relatively accessible platform for MRD detection, particularly when specific genetic biomarkers are available. However, method selection should be guided by disease context, available biomarkers, and required sensitivity. As MRD technologies continue to evolve with innovations in digital PCR, next-generation sequencing, and liquid biopsy applications, the implementation of standardized protocols and analytical frameworks will be essential for maximizing clinical utility across diverse cancer types.

Why qPCR? Principles of Quantitative Real-Time PCR for Sensitive Detection

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), also known as real-time PCR, is a powerful molecular biology technique that allows for the amplification and simultaneous quantification of targeted DNA molecules. Unlike conventional PCR, which provides only endpoint detection, qPCR enables researchers to monitor the accumulation of PCR products in real time as the reaction progresses. This capability for precise quantification, combined with high sensitivity and specificity, has established qPCR as the gold standard for nucleic acid quantification in various applications, including gene expression analysis, pathogen detection, and biomedical diagnostics [8] [9].

In the context of minimal residual disease (MRD) research, qPCR plays a particularly crucial role. MRD refers to the small number of cancer cells that remain in a patient during or after treatment, often at levels undetectable by conventional microscopy. Sensitive MRD monitoring in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), for instance, requires technologies capable of detecting one leukemic cell among 100,000 normal cells or more. qPCR-based methods using patient-specific immunoglobulin (IG) and T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangements as molecular markers have proven essential for this purpose, providing critical prognostic information that guides therapeutic decisions [10].

Basic Principles and Chemistries

Core Principle of Quantification

The fundamental principle of qPCR quantification relies on monitoring the fluorescence signal generated during each PCR cycle. The more copies of a DNA template present at the beginning of the experiment, the fewer PCR cycles are needed to generate enough product for detection. The key measurement is the quantification cycle (Cq), previously known as threshold cycle (Ct), which represents the number of cycles required for the fluorescence signal to cross a predetermined threshold above the background level. Lower Cq values indicate higher initial target concentrations [9].

Detection Chemistries

qPCR utilizes two primary types of detection chemistries, each with distinct advantages:

DNA-Binding Dyes (e.g., SYBR Green): These dyes bind non-specifically to double-stranded DNA and emit fluorescence upon excitation. SYBR Green is widely used due to its cost efficiency and ease of use. A significant advantage is that it does not require probe design, making it suitable for initial screening and expression profiling. However, a potential disadvantage is that it binds to any double-stranded DNA, including non-specific reaction products and primer dimers, which may lead to overestimation of the target concentration. Melt curve analysis is therefore essential post-amplification to verify reaction specificity [9].

Sequence-Specific Probes (e.g., TaqMan Probes): These oligonucleotide probes are labeled with a 5' fluorophore and a 3' quencher. When intact, the proximity of the quencher suppresses fluorescence. During PCR amplification, the 5' nuclease activity of the DNA polymerase cleaves the probe, separating the fluorophore from the quencher and generating a fluorescent signal. This method provides increased specificity and sensitivity over DNA-binding dyes, as fluorescence is generated only when the specific target sequence is amplified. This makes probe-based assays particularly valuable for applications requiring high specificity, such as MRD detection and multiplex PCR, where multiple targets are amplified in a single reaction [11] [9].

Table 1: Comparison of qPCR Detection Chemistries

| Feature | DNA-Binding Dyes (SYBR Green) | Sequence-Specific Probes (TaqMan) |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Lower - binds to any dsDNA | Higher - specific hybridization required |

| Cost | Lower | Higher |

| Probe Design | Not required | Required |

| Multiplexing Capability | No | Yes |

| Best For | Gene scanning, initial screening | High-specificity applications (e.g., MRD) |

| Verification Step | Melt curve analysis required | Not required |

Quantitative Approaches in qPCR

Absolute Quantification

Absolute quantification determines the exact number of target DNA molecules in a sample. This is typically achieved using a standard curve generated from serially diluted standards of known concentrations. The curve establishes a linear relationship between the Cq values and the logarithm of the initial template amount. The reliability of this method depends heavily on the accuracy of the standards and the amplification efficiencies. More recently, digital PCR (dPCR) has emerged as an alternative method for absolute quantification without standard curves. dPCR partitions a sample into thousands of individual reactions, applying a Poisson statistical analysis to provide absolute quantification with potentially higher precision and robustness to amplification efficiency variations compared to qPCR [12] [9].

Relative Quantification

Relative quantification compares the expression level of a target gene between different experimental conditions relative to one or more reference genes. This method avoids the need for standard curves and is widely used in gene expression studies. The two most common mathematical models are:

The Livak Method (2^(-ΔΔCq) Method): This method assumes that the target and reference genes amplify with near-perfect efficiency (close to 100%). It calculates the fold change in gene expression by normalizing the target gene's Cq to a reference gene and then to a calibrator sample (e.g., untreated control) [13].

The Pfaffl Method: This approach offers greater flexibility by incorporating the actual amplification efficiencies of both target and reference genes into the calculation. This provides a more accurate representation of relative gene expression levels when amplification efficiencies differ from 100% [13].

Table 2: Comparison of Quantitative Approaches in qPCR

| Quantification Method | Principle | Requirements | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute (Standard Curve) | Relates Cq to known standard concentrations | Accurate standard dilutions | Viral load, copy number variation |

| Absolute (Digital PCR) | Partitioning and Poisson statistics | Digital PCR system | Absolute quantification without standards |

| Relative (Livak Method) | 2^(-ΔΔCq) calculation with efficiency assumption | Stable reference genes, ~100% efficiency | Gene expression (efficiency ~100%) |

| Relative (Pfaffl Method) | Efficiency-corrected calculation | Precisely determined PCR efficiencies | Gene expression (variable efficiencies) |

Application to Minimal Residual Disease Detection

MRD Detection Using IG/TCR Rearrangements

In acute lymphoblastic leukemia, qPCR-based MRD monitoring frequently targets patient-specific immunoglobulin (IG) and T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangements. During lymphoid development, each cell undergoes V(D)J recombination, creating unique DNA sequences that serve as clonal markers for the leukemic population. At diagnosis, these specific rearrangements are identified in the patient's leukemic cells. Subsequently, complementary allele-specific oligonucleotide (ASO) primers are designed for highly sensitive MRD monitoring during treatment, allowing detection of up to 1 leukemic cell in 100,000 normal cells (sensitivity of 10^-5) [10].

Workflow for MRD Detection

The standard workflow for MRD detection using qPCR involves several critical steps from sample collection to data interpretation, as illustrated below:

Emerging Technologies in MRD Detection

While qPCR remains a cornerstone for MRD assessment, new technologies are emerging. Next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based methods enable deeper analysis of IG/TCR gene rearrangements and can overcome certain limitations of qPCR, such as clonal evolution that may lead to false-negative results. Additionally, droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) has shown promise in recent studies, demonstrating significantly better quantitative limit of detection and sensitivity compared to traditional qPCR, particularly for critical low-positive samples [10] [12].

Detailed Experimental Protocol for qPCR-Based MRD Detection

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction

- Sample Source: Bone marrow aspirates are the preferred material for MRD assessment in ALL. Peripheral blood is not recommended as MRD levels are typically 1-3 logs lower than in bone marrow [10].

- DNA Extraction: Use standardized commercial kits for genomic DNA extraction. Ensure high DNA quality and quantity, measuring concentration using spectrophotometry.

- DNA Storage: Extract DNA in sufficient quantities from the diagnostic sample to serve as a positive control and for all future MRD assessments.

Identification of Clonal Markers at Diagnosis

- PCR Amplification: Perform multiplex PCR assays to identify clonal IG and/or TCR gene rearrangements.

- Clonality Confirmation: Analyze PCR products by capillary electrophoresis or heteroduplex analysis to confirm clonality.

- Sequencing: Sequence clonal PCR products to identify the specific V(D)J junctional regions that will serve as patient-specific markers.

ASO Primer and Probe Design

- Primer Design: Design allele-specific oligonucleotide (ASO) primers complementary to the unique junctional regions identified during sequencing.

- Probe Design: For probe-based qPCR, design dual-labeled hydrolysis probes (e.g., TaqMan) according to these criteria:

- Tm: 5-10°C higher than primers (typically 65-70°C)

- Length: 20-30 nucleotides

- GC Content: 30-80%

- 5' Base: Avoid G at the 5' end as it can quench common dyes like FAM [11]

- Specificity Check: Validate primer and probe specificity using BLAST analysis against the human genome.

qPCR Assay Validation

- Sensitivity Testing: Prepare serial dilutions of diagnostic DNA in polyclonal normal DNA (e.g., 10^-2 to 10^-5) to establish the quantitative range and limit of detection.

- Efficiency Calculation: Perform a standard curve with at least 3 replicates per dilution point. Calculate PCR efficiency using the formula: Efficiency (%) = (10^(-1/slope) - 1) × 100. Acceptable efficiency ranges from 90-110% [14].

- Reproducibility Assessment: Determine intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation.

MRD Quantification in Follow-up Samples

- Experimental Setup: Include appropriate controls in each run:

- No template control (NTC): Identifies contamination

- Positive control: Diagnostic DNA diluted in normal DNA

- Negative control: Polyclonal normal DNA

- PCR Conditions:

- Reaction Volume: 20-50 μL

- Thermal Cycling: Initial denaturation (95°C for 10 min); 45-50 cycles of denaturation (95°C for 15 sec), annealing (60°C for 30-60 sec), and extension (72°C for 30 sec)

- Data Analysis: Use the ΔΔCq method or efficiency-corrected model (Pfaffl method) for quantification relative to the diagnostic sample.

Critical Controls and Data Interpretation

Essential Controls for Reliable Results

- No Reverse Transcriptase Control (-RT): For RT-qPCR applications, this control checks for genomic DNA contamination by omitting the reverse transcriptase enzyme [15] [11].

- No Template Control (NTC): Contains all reaction components except the DNA template to identify reagent contamination.

- Positive Controls: Include dilution series of known targets to validate assay sensitivity and efficiency.

- Reference Genes: Use at least two validated reference genes with stable expression across all experimental conditions for normalization in relative quantification [11].

Data Analysis and Quality Assessment

- Baseline and Threshold Setting: The baseline represents the background fluorescence during early cycles (typically cycles 3-15). The threshold should be set in the exponential phase of amplification, sufficiently above the baseline but within the linear range of amplification [14].

- Amplification Efficiency Calculation: Prepare a standard curve with serial dilutions. Plot the log of the initial template amount against the Cq values. The slope of the line is used to calculate efficiency: Efficiency = 10^(-1/slope) - 1. Ideal efficiency is 100% (slope = -3.32) [14].

- Quantification Methods: Based on the experimental design and validation data, choose between absolute quantification (standard curve) or relative quantification (ΔΔCq or Pfaffl method).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR-Based MRD Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specifications/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from patient samples | Ensure high molecular weight and purity (A260/A280 ~1.8) |

| qPCR Master Mix | Provides optimized buffer, enzymes, dNTPs for amplification | Choose probe-based or SYBR Green format; hot-start recommended |

| Sequence-Specific Probes | Target-specific detection (e.g., TaqMan) | Dual-labeled with 5' fluorophore (FAM, HEX) and 3' quencher |

| Allele-Specific Primers | Amplification of patient-specific IG/TCR rearrangements | Designed to complement unique V(D)J junctional regions |

| Reference Gene Assays | Normalization of sample input variation | Use validated, stably expressed genes (e.g., ABL, GUSB) |

| DNase/RNasin | Prevention of nucleic acid degradation | Essential for RNA workflows in RT-qPCR |

| Standard Curve Templates | Quantification and efficiency calculation | Serial dilutions of known target concentration |

Comparison of MRD Detection Technologies

The landscape of MRD detection methodologies continues to evolve, with each technology offering distinct advantages and limitations as summarized below:

Quantitative real-time PCR remains an indispensable technology for sensitive detection of minimal residual disease in leukemia and other malignancies. Its robust quantification capabilities, combined with well-established standardization through consortia like EuroMRD, make it a cornerstone of modern clinical diagnostics and research. While emerging technologies like digital PCR and next-generation sequencing offer promising enhancements for specific applications, qPCR continues to provide the sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility required for reliable MRD assessment. The continued refinement of qPCR protocols, primer design strategies, and data analysis methods will further solidify its role in personalized medicine and treatment response monitoring.

Minimal residual disease (MRD) refers to the small population of leukemic cells that persists in patients after treatment at levels undetectable by conventional microscopy [2]. The accurate detection of MRD is a powerful independent prognostic factor in acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), guiding risk stratification and therapeutic decisions [16] [17]. Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) has established itself as a cornerstone technology for MRD monitoring due to its exceptional sensitivity, capable of detecting one leukemic cell among 100,000 normal cells (sensitivity of 10⁻⁵) [2] [17].

The clinical significance of MRD detection is profound. Patients who achieve MRD negativity demonstrate significantly superior outcomes, with 5-year overall survival rates of approximately 68% compared to only 34% for MRD-positive patients [17]. Within the framework of a comprehensive thesis on qPCR-MRD protocols, this application note details the three principal categories of molecular biomarkers—fusion gene transcripts, immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene rearrangements, and specific mutations—alongside their associated experimental methodologies.

Key Biomarker Categories for qPCR-MRD

The selection of an appropriate biomarker is critical for successful MRD tracking. The applicability and performance of each biomarker category vary, influencing their suitability for different clinical contexts.

Table 1: Key Biomarker Categories for qPCR-MRD in ALL

| Biomarker Category | Examples | Applicability | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fusion Gene Transcripts | BCR::ABL1, ETV6::RUNX1, KMT2A rearrangements | ~40-50% of ALL cases [2] | Very high sensitivity (10⁻⁶); stable target; no patient-specific reagents needed [16] [2] | Limited applicability; cannot track clonal evolution [16] |

| Immunoglobulin (IG)/T-Cell Receptor (TCR) Gene Rearrangements | IGH, IGK, TRG, TRD rearrangements | >90% of ALL cases [18] | High sensitivity (10⁻⁵); highly patient-specific; broad applicability [2] [18] | Requires diagnostic sample; time-consuming setup; clonal evolution may cause false negatives [16] |

| Recurrent Somatic Mutations | NPM1 mutations | Subset of AML and ALL cases | Stable marker; direct targeting of driver mutation | Lower applicability in ALL; requires knowledge of specific mutation [17] |

The workflow for implementing these biomarkers in a qPCR-MRD protocol involves sequential steps from sample collection to final data interpretation, guided by international consortia like EuroMRD to ensure standardization and quality [18].

Fusion Gene Transcripts as Biomarkers

Principle and Clinical Relevance

Fusion genes result from chromosomal rearrangements that create novel chimeric transcripts, serving as highly specific leukemia markers. These aberrations are not only drivers of leukemogenesis but also ideal MRD targets due to their stability throughout the disease course [16]. In Philadelphia chromosome-positive ALL, the BCR::ABL1 fusion is a critical target, while in pediatric B-ALL, ETV6::RUNX1 is a common favorable prognostic marker [16] [17].

Detailed Protocol: RT-qPCR for Fusion Transcript Detection

Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction:

- Sample Collection: Collect bone marrow aspirate or peripheral blood in appropriate anticoagulant tubes (e.g., EDTA). Process samples within 24-48 hours.

- RNA Extraction: Use commercial kits (e.g., Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA kits) for simultaneous DNA/RNA extraction or dedicated RNA isolation kits. For FFPE samples, use specialized kits like the AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit [19].

- Quality Control: Assess RNA concentration using a fluorometer (e.g., Qubit 2.0) and purity/integrity with a spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop) and automated electrophoresis system (e.g., TapeStation). RNA Integrity Number (RIN) >7.0 is recommended for reliable RT-qPCR [19].

Reverse Transcription and qPCR Setup:

- cDNA Synthesis: Convert 100 ng - 1 µg of total RNA to cDNA using a High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit with random hexamers. Include a no-reverse transcriptase control (-RT) for each sample to detect genomic DNA contamination.

- Assay Design: Use publicly available primer/probe sequences or design assays spanning the fusion junction to ensure specificity. The EuroMRD consortium provides standardized assays for common fusions like BCR::ABL1 [18].

- Reaction Setup: Prepare reactions in a 96- or 384-well plate format. A typical 20 µL reaction contains: 1x TaqMan Master Mix, 900 nM forward and reverse primers, 250 nM TaqMan probe (FAM-labeled), and 5 µL of cDNA template.

- Standard Curve: Include a 5-6 point standard curve in each run using serial dilutions (e.g., 1:10 from 10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁵) of plasmid DNA containing the target fusion sequence or cDNA from a positive control cell line with known copy number.

Thermocycling Conditions:

- Step 1: 50°C for 2 minutes (UNG incubation, if applicable)

- Step 2: 95°C for 10 minutes (polymerase activation)

- Step 3: 45 cycles of:

- 95°C for 15 seconds (denaturation)

- 60°C for 1 minute (annealing/extension)

- Data collection occurs at the annealing/extension step of each cycle.

Data Interpretation and Quality Control

Data analysis requires precise calculation based on the standard curve. The quality of the entire process must be assured through stringent controls.

Table 2: Essential Controls for Fusion Gene qPCR-MRD

| Control Type | Purpose | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| No Template Control (NTC) | Detects reagent contamination | Cq value >40 or undetermined |

| Positive Control | Verifies assay functionality | Cq value within expected range |

| Negative Control (Normal PBMMC) | Confirms assay specificity | Cq value >40 or undetermined |

| Standard Curve | Enables quantification | PCR efficiency: 90-110%; R² > 0.98 |

| Housekeeping Gene (e.g., ABL1, GUSB) | Assesses RNA quality and input | Cq value within normal range for sample type |

Results are typically reported as normalized copy numbers, for instance, as BCR::ABL1⁰¹⁰/ABL1 ratio, with a sensitivity of 10⁻⁴ to 10⁻⁶ achievable under optimal conditions [2]. The MIQE 2.0 guidelines provide a comprehensive framework for ensuring experimental rigor and transparent reporting of all qPCR parameters [20].

Immunoglobulin and T-Cell Receptor Gene Rearrangements

Principle and Clonality Assessment

During lymphocyte development, the genes encoding immunoglobulin (IG) and T-cell receptors (TCR) undergo V-(D)-J recombination, creating unique nucleotide sequences in the complementarity-determining regions (CDR3) that serve as a "clonal fingerprint" for each lymphocyte and its malignant progeny [16] [18]. This principle allows for the design of patient-specific qPCR assays to track the leukemic clone with high sensitivity. Notably, cross-lineage rearrangement is common; for example, TCR rearrangements can be found in up to 90% of B-ALL cases, expanding the applicability of this approach [17].

Detailed Protocol: IG/TR Rearrangement Analysis

Diagnostic Marker Identification and Assay Design:

- DNA Extraction from Diagnostic Sample: Extract high-quality DNA from a bone marrow sample with known leukemic infiltration. Use kits designed for genomic DNA extraction (e.g., QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit). Assess DNA purity (A260/A280 ~1.8) and integrity via agarose gel electrophoresis or Fragment Analyzer.

- Clonality Assessment: Perform multiplex PCR followed by fragment analysis or Sanger sequencing to identify the specific clonal IG/TR rearrangements (e.g., IGH, IGK, TRG, TRD) present in the leukemic cells. The EuroMRD Consortium provides standardized multiplex PCR protocols [18].

- Patient-Specific Primer/Probe Design: Design a TaqMan probe that binds to the unique CDR3 sequence of the identified clone. The allele-specific oligonucleotide (ASO) primer is designed to span the V-N-J junction, with its 3' end being patient-specific.

RQ-PCR for MRD Quantification in Follow-Up Samples:

- Reaction Setup: For each follow-up sample, set up a 20 µL reaction containing: 1x TaqMan Master Mix, 200-600 nM ASO primer, 200-600 nM reverse primer, 100-300 nM TaqMan probe (FAM-labeled), and 500 ng of patient DNA.

- Control Reactions: Include a polyclonal control (DNA from healthy donors) to confirm the absence of background amplification and a positive control (diluted diagnostic DNA) to assess assay performance.

- Standard Curve and Sensitivity Dilution Series: Prepare a standard curve using serial dilutions of the diagnostic DNA into polyclonal normal DNA (e.g., 10⁻², 10⁻³, 10⁻⁴, 10⁻⁵). A separate dilution series (e.g., 10⁻⁴, 10⁻⁵) should be included to empirically determine the sensitivity of the assay for that specific sample.

- Thermocycling Conditions: Use the same profile as described for fusion genes (Section 3.2).

Data Interpretation and EuroMRD Guidelines

Data interpretation must follow international guidelines, such as those established by the EuroMRD Consortium, which define specific categories for result reporting [18]. Adherence to these guidelines is critical for inter-laboratory comparability and consistent clinical decision-making.

- Quantitative Range (QR): The MRD level is considered quantitative if the result lies within the linear range of the standard curve and the corresponding sensitivity dilution is positive.

- Positive, Below Quantitative Range (pos_bqL): A recently refined category. A sample is positive with a non-quantifiable result if the target is detected below the QR, but the sensitivity of the assay is sufficient to detect MRD at that level.

- Negative: The target is not detected, and the sensitivity of the assay is sufficient (e.g., at least 10⁻⁴) to rule out the presence of the leukemic clone at that threshold.

- MRD of Uncertain Significance: A new category introduced in updated guidelines for low-level signals that cannot be definitively classified due to technical or biological factors [18].

Laboratories performing this analysis are strongly encouraged to participate in the EuroMRD external quality assessment (QA) scheme to ensure proficiency and standardization [18].

Successful implementation of qPCR-MRD assays requires a suite of validated reagents, specialized equipment, and bioinformatics resources.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR-MRD

| Category | Item | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | DNA/RNA Co-extraction Kit | Simultaneous purification of DNA (for IG/TR) and RNA (for fusions) from a single sample | Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA Mini Kit (for fresh tissue) [19] |

| FFPE-specific Extraction Kit | Optimized isolation of fragmented nucleic acids from archival tissue | Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA FFPE Kit [19] | |

| Reverse Transcription | cDNA Synthesis Kit | Converts RNA to cDNA for fusion transcript analysis | Kits including random hexamers and reverse transcriptase |

| qPCR Core Reagents | TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix | Provides enzymes, dNTPs, and buffer for probe-based qPCR | Must include dUTP and Uracil-N-Glycosylase (UNG) for carryover contamination prevention |

| Assay Design | EuroMRD Primer/Probe Sequences | Standardized, validated assays for common fusion genes and IG/TR frameworks | Available through the EuroMRD Consortium [18] |

| Critical Controls | Standard Curve Template | Quantification benchmark for both fusion and IG/TR assays | Plasmid DNA or cell line cDNA/DNA with known target copy number |

| Polyclonal Control DNA | Background signal control for IG/TR assays | Pooled DNA from healthy donor peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) | |

| Quality Control | RNA Integrity Number (RIN) Assessment | Evaluates RNA quality pre-reverse transcription | Agilent TapeStation system [19] |

| Software & Guidelines | MIQE 2.0 Guidelines | International standard for reporting qPCR experiments; ensures rigor and reproducibility [20] | |

| EuroMRD QA Scheme | External proficiency testing and standardized data interpretation for MRD in ALL [18] |

The robust detection of MRD using qPCR relies on the precise targeting of fusion gene transcripts, immunoglobulin and T-cell receptor gene rearrangements, and specific mutations. The protocols and guidelines detailed in this application note, grounded in international standards like those from the EuroMRD Consortium and MIQE 2.0, provide a framework for generating reliable, clinically actionable data. As the field advances, the integration of these well-established qPCR methods with emerging technologies like droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) and next-generation sequencing (NGS) will further enhance the sensitivity and comprehensive nature of MRD assessment, ultimately refining risk stratification and personalizing treatment strategies for patients with acute leukemias [16] [12].

Minimal Residual Disease (MRD), also referred to as Measurable Residual Disease, describes the small population of cancer cells that persist in patients after treatment who have achieved clinical and hematological remission [2]. These residual cells, often present at levels undetectable by conventional morphological microscopy, represent a latent reservoir of disease that can ultimately lead to clinical relapse [2]. In hematological malignancies, the detection and monitoring of MRD have become integral to modern clinical management, providing a significantly more sensitive assessment of treatment response than traditional methods such as morphological examination of bone marrow, which has a sensitivity of only 5% (1 in 20 cells) [2] [21]. The evolving role of MRD extends beyond prognosis into therapeutic decision-making, enabling risk-adapted treatment strategies and serving as a powerful surrogate endpoint in clinical trials [21].

The Prognostic Power of MRD in Risk Stratification

MRD status has emerged as a universally significant prognostic biomarker across hematologic malignancies. The presence of MRD (MRD-positivity) signifies residual treatment-resistant disease and is consistently associated with worse clinical outcomes, while MRD negativity correlates with superior survival rates [21].

Table 1: Prognostic Impact of MRD Status Across Hematologic Malignancies

| Malignancy | Impact on Progression-Free Survival (PFS) | Impact on Overall Survival (OS) |

|---|---|---|

| Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) | Not Specified | 5-year OS: 68% if MRD-negative vs. 34% if MRD-positive [21] |

| Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) | HR 0.23 for EFS in pediatric patients; HR 0.28 for EFS in adult patients [21] | HR 0.28 for both pediatric and adult patients [21] |

| Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) | HR 0.28 (72% reduction in risk of progression/death); HR 0.24 in first-line setting [21] | Not Specified |

| Multiple Myeloma | HR 0.33 [21] | HR 0.45 [21] |

The correlation between MRD status and patient outcomes provides the foundation for its use in risk stratification. Patients who achieve MRD negativity, particularly when sustained, belong to a favorable risk group with significantly better long-term prospects. Conversely, MRD-positive patients are identified as having higher-risk disease, warranting more aggressive monitoring and intervention strategies [2] [21]. The depth of MRD clearance also holds prognostic importance, with earlier clearance during treatment often portending improved outcomes [21].

MRD-Guided Treatment Decisions

The ability of MRD testing to identify patients at varying levels of relapse risk enables more personalized and dynamic treatment approaches. The clinical application of MRD results can be visualized in the following decision pathway.

Treatment Intensification and Escalation

For patients with persistent MRD positivity, clinical evidence supports the consideration of treatment intensification to eradicate resistant disease clones. This may involve switching to alternative drug classes, pursuing allogeneic stem cell transplantation where appropriate, or enrolling in clinical trials of novel agents [21]. In diseases like Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia (APL) and Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML), MRD assessment by RT-PCR is successfully integrated into treatment algorithms to guide therapy duration and identify when treatment changes are needed [21].

Treatment De-Escalation

A promising application of MRD testing is identifying patients who may benefit from treatment de-escalation to reduce therapy-related toxicity. Patients who achieve sustained MRD negativity may be candidates for reduced treatment duration or intensity, including avoidance of more toxic interventions like stem cell transplantation [21]. In solid tumors, studies are investigating whether MRD-negative patients can delay or avoid systemic therapies, thereby sparing them from serious side effects [22].

Dynamic Monitoring and Early Intervention

Serial MRD monitoring enables earlier detection of molecular relapse before clinical or radiographic recurrence becomes apparent [21] [23]. This "lead time" allows clinicians to intervene at a lower disease burden, potentially improving treatment efficacy. In the post-transplant setting, MRD detection can signal impending relapse well before it becomes morphologically evident, enabling preemptive interventions such as rapid immunosuppression withdrawal or donor lymphocyte infusion [21] [6].

MRD Detection Methodologies

Multiple laboratory techniques are available for MRD detection, each with distinct sensitivities, advantages, and limitations. The choice of methodology depends on disease type, available genetic markers, and required sensitivity.

Table 2: Comparison of Major MRD Detection Techniques

| Method | Applicability | Sensitivity | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiparametric Flow Cytometry (MFC) | ~100% [2] | 10⁻³ to 10⁻⁶ [2] | Fast turnaround; Wide applicability [2] | Lack of standardization; Phenotype changes [2] |

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | ~40-50% [2] | 10⁻⁴ to 10⁻⁶ [2] | Highly standardized; Lower cost [2] | Only one gene/assay; Primer-specific [2] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | >95% [2] | 10⁻² to 10⁻⁶ [2] | Multiple genes simultaneously; Broad applicability [2] | High cost; Complex analysis [2] |

| Digital PCR (ddPCR) | Not Specified | Not Specified | Absolute quantification; High sensitivity | Not widely standardized [24] |

| Liquid Biopsy (ctDNA) | Emerging for solid tumors & AML [22] [6] | Varies by platform | Minimally invasive; Whole genome coverage [22] | Lower tumor fraction in some cancers [22] |

qPCR Workflow for MRD Detection

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) remains a cornerstone technique for MRD detection, particularly in malignancies with well-defined genetic markers. The following protocol outlines a standardized qPCR workflow for MRD assessment.

Detailed qPCR Experimental Protocol

Sample Collection and Processing

- Sample Types: Bone marrow (preferred for highest sensitivity) or peripheral blood collected in appropriate anticoagulant tubes (e.g., EDTA or cell-free DNA collection tubes) [6].

- Cell Processing: For cellular DNA/RNA analysis, isolate mononuclear cells using density gradient centrifugation. For plasma cfDNA analysis, centrifuge blood samples within specified timeframes to prevent cellular degradation [6].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Use commercial kits (e.g., QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit) optimized for the sample type. Quantify extracted DNA/RNA using fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit Fluorometer) for accurate concentration measurement [6].

Reverse Transcription (for RNA Targets)

- For fusion transcript detection (e.g., BCR-ABL1, PML-RARA), convert RNA to cDNA using reverse transcriptase.

- Use gene-specific primers or random hexamers with temperature conditions according to enzyme manufacturer specifications.

- Include negative controls (no template and no enzyme) to monitor contamination.

Primer and Probe Design

- Design primers and probes to span rearrangement-specific junctional regions for maximal specificity.

- Validate primer specificity using in silico analysis and experimental testing against positive and negative controls.

- For DNA targets, design amplicons of 50-150 bp for optimal qPCR efficiency [25].

qPCR Reaction Setup

- Reaction Components: TaqMan or SYBR Green master mix, forward and reverse primers, probe (if using TaqMan), template DNA/cDNA, and nuclease-free water.

- Automated Liquid Handling: Utilize systems like the I.DOT Liquid Handler to improve pipetting precision, reduce cross-contamination risk, and increase throughput [25].

- Controls: Include positive controls (diagnostic sample with known mutation), negative controls (healthy donor), no template controls, and standard curve dilutions for quantification.

Thermal Cycling Conditions

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2-10 minutes

- Amplification Cycles (40-50 cycles): Denaturation at 95°C for 15-30 seconds, Annealing/Extension at 60°C for 30-60 seconds (temperature optimized for primer Tm)

- Data Acquisition: Collect fluorescence data during the annealing/extension phase of each cycle.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Determine Cycle threshold (Ct) values for samples and standards.

- Generate a standard curve from serial dilutions of positive control material to quantify target levels.

- Calculate MRD levels relative to reference genes (e.g., ABL1, GUSB) to normalize for sample quality and quantity.

- Report results as target:control gene ratio with assay sensitivity limit.

Critical Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR-based MRD Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality DNA/RNA from patient samples | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit [6] |

| Cell-Free DNA Collection Tubes | Stabilization of blood samples for plasma separation | Streck cell-free DNA Blood Collection Tubes [6] |

| Reverse Transcriptase Enzyme | cDNA synthesis from RNA targets | Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus (M-MLV) RT |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Specific amplification with reduced primer-dimer formation | Taq DNA Polymerase |

| Fluorescent Probes/Dyes | Real-time detection of amplification products | TaqMan probes, SYBR Green dye [25] |

| qPCR Master Mix | Optimized buffer system for efficient amplification | Contains dNTPs, MgCl₂, reaction buffer |

| Primers and Probes | Target-specific amplification | Designed to detect fusion genes or rearrangements [2] |

| Quantification Standards | Standard curve generation for absolute quantification | Plasmid standards, cell line DNA with known targets |

| Reference Gene Primers | Amplification control and normalization | ABL1, GUSB, BCR [2] |

Troubleshooting Common qPCR Challenges in MRD Detection

Successful MRD detection by qPCR requires optimization to address several technical challenges that can impact assay sensitivity and reliability.

- Low Yield/Amplification Efficiency: Poor RNA quality or inefficient cDNA synthesis can reduce sensitivity. Remedy by optimizing RNA purification steps, performing appropriate clean-up procedures, and adjusting cDNA synthesis conditions. Verify RNA integrity prior to reverse transcription [25].

- Non-Specific Amplification: Primer-dimer formation or mispriming can lead to false positives. Address by redesigning primers using specialized software, optimizing annealing temperature, and implementing touchdown PCR protocols. Use hot-start polymerase to minimize non-specific amplification at lower temperatures [25].

- Ct Value Variations: Inconsistent pipetting techniques cause template concentration differences across replicates. Improve by implementing proper pipetting techniques, using automated liquid handling systems, and ensuring thorough mixing of reaction components [25].

- Inhibition: Substances co-purified with nucleic acids can inhibit PCR. Detect through dilution series or internal controls. Remedies include additional purification steps, dilution of template, or use of inhibitor-resistant polymerase formulations [25].

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of MRD detection is rapidly evolving with several promising technological advances. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) approaches, particularly error-corrected sequencing, are achieving sensitivities of 10⁻⁶ and enabling comprehensive assessment of the clonal landscape [2]. Liquid biopsy using circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis represents a minimally invasive alternative for MRD monitoring, with applications expanding from solid tumors to hematologic malignancies like AML [22] [6]. Tumor-informed, whole genome sequencing-based tests (e.g., Precise MRD) can monitor hundreds to thousands of tumor-specific variants, enabling exceptional sensitivity and quantification of ctDNA even in cancers with low tumor fraction [22]. Standardization efforts led by consortia such as EuroFlow and EuroMRD continue to harmonize MRD assessment protocols across laboratories, though comparable standardization in AML remains an unmet need [21].

MRD assessment has transformed the clinical management of hematologic malignancies, providing an powerful tool for risk stratification and treatment personalization. The integration of sensitive molecular techniques like qPCR into standardized clinical protocols enables dynamic monitoring of disease burden, guiding critical therapeutic decisions. As detection technologies continue to advance and standardization improves, MRD-directed therapy promises to further optimize outcomes through truly personalized treatment approaches.

A Step-by-Step qPCR Protocol for Robust MRD Detection

The accurate detection of Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) via quantitative PCR (qPCR) is a powerful independent predictor of clinical outcomes for patients with hematologic malignancies such as Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) [26]. The sensitivity of these molecular assays, which can detect as low as one cancer cell among 100,000 normal cells, means that the pre-analytical phase—specifically, sample collection and nucleic acid stabilization—is a critical determinant of assay success [26] [12]. Variations in collection techniques, sample handling, and storage can profoundly impact nucleic acid integrity, leading to false-negative results or inaccurate MRD quantification, which in turn can misguide therapeutic decisions. This application note details standardized, evidence-based protocols for the collection and processing of blood and bone marrow to preserve nucleic acid integrity, ensuring reliable and reproducible results in MRD research.

Sample Collection Protocols

Bone Marrow Aspiration for MRD Analysis

The following protocol, adapted from a comprehensive methodological guide, is designed to obtain high-quality bone marrow aspirates while minimizing hemodilution, which can confound MRD results [27].

- Patient Preparation and Positioning: Place the patient in a lateral decubitus position. Locate the posterior superior iliac spine (typically one hand width distal to the iliac crest and one hand width lateral to the midline) and mark the site. Disinfect the skin thoroughly with a chlorhexidine-ethanol solution [27].

- Anesthesia: Infiltrate the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and periosteum with 1% lidocaine. Adequate anesthesia of the periosteum is crucial for patient comfort. Test the anesthetized area by tapping with the needle; the patient should feel pressure but no pain [27].

- Aspiration Technique:

- Introduce a sterile bone marrow aspiration needle (e.g., 15 or 16 gauge) with a rotating motion until a loss of resistance indicates entry into the marrow cavity [27].

- Remove the stylet and attach a 10-20 mL syringe. Apply negative pressure with a gentle pull. Aspirate only 1-2 mL of marrow to avoid hemodilution, which is a critical source of pre-analytical error. The first 1-2 mL contains the highest concentration of bone marrow spicules [27].

- Warn the patient they may feel a momentary cramping sensation.

- Sample Handling:

- Immediately transfer the aspirate into a tube containing an anticoagulant, such as EDTA or heparin, and invert the tube several times to ensure adequate mixing and prevent coagulation [27] [28].

- For MRD analysis, a successful aspirate should yield at least 10 million viable cells to perform advanced analyses like Leukemia-Associated Immunophenotype (LAIP) and leukemia stem cell (LSC) detection [27].

Peripheral Blood Collection for Molecular Analysis

While bone marrow is the preferred matrix for MRD, peripheral blood is increasingly used, and its proper collection is equally important.

- Collection: Collect venous blood into EDTA Vacutainer tubes [29].

- Storage: Store samples at -70 °C or lower until analysis to preserve nucleic acid integrity. Repeated thawing and freezing cycles should be strictly avoided [29].

Sample Processing & Nucleic Acid Stabilization

Processing of Bone Marrow Aspirates

- Timing: All specimens for immunophenotyping and molecular analysis should be processed preferentially within 24 hours of collection [27]. While samples can sometimes be analyzed after up to 72 hours at ambient temperature, this is not recommendable for optimal results [27].

- Conditions: Perform all handling under sterile conditions to enable potential cryopreservation of cells for future research or quality assessment [27].

A Rapid Whole Blood Processing Protocol

For certain qPCR applications, standard DNA extraction can be bypassed with a rapid whole-blood processing method, saving significant time and cost without compromising genotyping accuracy [29]. The workflow below outlines this protocol and its application context.

Detailed Protocol:

- Dilution: Dilute 20 µL of EDTA-anticoagulated whole blood with 20 µL of deionized water [29].

- Incubation: Incubate the diluted blood at 90 °C for 3 minutes. This heat treatment helps to lyse cells and inactivate nucleases [29].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge the sample at 10,000 × g for 2 minutes to pellet cell debris [29].

- Supernatant Collection: The resulting supernatant contains amplifiable DNA and can be used directly as a template in subsequent real-time PCR reactions (use 4 µL per 16 µL PCR mixture) [29].

Impact of Sample Stabilization on RNA Integrity

For gene expression assays, the stabilization method is a critical pre-analytical factor affecting RNA integrity. Research comparing different methods for human lung tissue demonstrates clear differences in RNA quality [30]. The table below summarizes key performance data for DNA and RNA samples processed for qPCR analysis.

Table 1: Quantitative Data from Nucleic Acid Analysis in Blood and Bone Marrow

| Sample Type / Method | Analyte | Key Performance Metric | Result / Value | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modified Whole Blood (Rapid protocol) | DNA | Median Ct value (FV Leiden, wt/wt) | 25.3 | [29] |

| Standard DNA Extract (from blood) | DNA | Median Ct value (FV Leiden, wt/wt) | 18.5 | [29] |

| Bone Marrow (for Leishmania detection) | DNA | Correlation: Amastigote count vs. Ct value | Spearman's ρ = -0.89 | [28] |

| RNA from RNAlater | RNA | Average RIN (RNA Integrity Number) | 7.6 | [30] |

| RNA from Snap-Freezing with OCT | RNA | Average RIN (RNA Integrity Number) | 8.1 | [30] |

| RNA from Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) | RNA | Average RIN (RNA Integrity Number) | 1.4 | [30] |

Molecular Analysis & Quality Control

DNA Extraction and qPCR Setup

- DNA Extraction: For conventional protocols, genomic DNA can be isolated from 200 µL of blood or bone marrow aspirate using commercial kits (e.g., MagCore Genomic DNA Whole Blood Kit) according to manufacturer's instructions [29] [28]. Automated systems like the KingFisher Flex can improve reproducibility for high-throughput labs [28].

- qPCR Reaction Setup:

Quality Control and Assay Validation

Ensuring the integrity of nucleic acids and validating the qPCR assay are non-negotiable for reliable MRD quantification. The following diagram and table outline the core components and reagents for this critical phase.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| EDTA or Heparin Tubes | Anticoagulant for blood and bone marrow collection | Prevents coagulation; EDTA is preferred for molecular studies. |

| RNAlater / RNA Stabilization Reagents | Preserves RNA integrity in fresh tissues/cells by stabilizing and protecting RNA. | Critical for gene expression studies from tissue samples [30]. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-purity genomic DNA from whole blood or bone marrow. | MagCore Genomic DNA Whole Blood Kit; automated systems available [29] [28]. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains enzymes, dNTPs, buffer, and passive reference dye for real-time PCR. | Should include a passive reference dye (e.g., ROX) to normalize fluorescence [31]. |

| Hydrolytic (TaqMan) Probes | Sequence-specific detection providing high specificity for target amplification. | Used with CE-IVD certified kits for allelic discrimination (e.g., thrombophilic mutations) [29]. |

| Validated Primer/Probe Sets | For specific detection of MRD targets (e.g., IG/TR rearrangements, fusion transcripts). | Must be validated for inclusivity, exclusivity, and dynamic range [32] [33]. |

| Internal Extraction Control (IEC) | Non-target DNA added to samples to monitor extraction efficiency. | Helps identify PCR inhibition or extraction failures [28]. |

Key QC Steps:

- Nucleic Acid Purity and Integrity: Assess DNA/RNA concentration and purity via spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio >1.8). For RNA, the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) is a key metric; values above 8.0 indicate intact RNA, while values below 5.0 suggest significant degradation [34] [30].

- Assay Validation Parameters: Following MIQE guidelines and related consensus statements is essential [32] [33].

- Dynamic Range and Efficiency: Test a 7-log 10-fold dilution series of the target. The assay should have a linear range of 6-8 orders of magnitude with an amplification efficiency between 90-110% and an R² value of ≥0.980 [32].

- Inclusivity and Exclusivity: Ensure the assay detects all intended target variants (inclusivity) and does not cross-react with genetically similar non-targets (exclusivity), both in silico and experimentally [32] [33].

- Precision: Measure the Coefficient of Variation (CV) across technical and biological replicates. Low CV indicates high precision and reliable ability to detect fold changes [31].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Absolute vs. Relative Quantification: MRD analysis often uses absolute quantification to determine the exact number of leukemic cells per total number of normal cells (e.g., 10⁻⁴) [26] [31]. This requires a standard curve from diagnostic DNA diluted in normal DNA [26].

- Digital PCR (dPCR) as an Emerging Tool: dPCR technologies, such as droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), offer absolute quantification without a standard curve. Recent studies show ddPCR can outperform qPCR in MRD monitoring, providing better sensitivity and reducing the number of non-quantifiable low-positive results [26] [12].

- Replicates and Statistics:

- Use at least technical triplicates to account for system variation and allow for outlier detection [31].

- Employ sufficient biological replicates to account for true variation within a sample group [31].

- Use appropriate statistical tests (e.g., t-test) to determine if observed fold changes are significant, considering both statistical and physiological relevance [31].

Robust MRD research begins long before the qPCR machine starts running. Meticulous attention to sample collection, processing, and nucleic acid stabilization is fundamental to preserving the integrity of the genetic template. By adhering to the standardized protocols outlined here—from the technique of bone marrow aspiration to the implementation of rigorous quality control measures—researchers can significantly enhance the accuracy, sensitivity, and reproducibility of their qPCR data. This, in turn, provides a more reliable foundation for understanding disease progression and guiding therapeutic development in oncology.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) is a foundational technique in molecular biology, enabling the accurate quantification of nucleic acids. In the context of Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) detection in hematological malignancies, qPCR serves as a critical tool for monitoring residual cancer cells after treatment, with sensitivities reaching 10⁻⁴ to 10⁻⁶ [2]. This high sensitivity allows clinicians to identify patients at risk of relapse and guide treatment decisions. The accuracy of MRD detection hinges on a robustly designed qPCR assay, where careful selection of primers and probes, along with meticulous optimization of amplification efficiency, is paramount for generating reliable, reproducible data that can inform clinical decision-making [2] [18].

Primer and Probe Design Fundamentals

Core Principles for Primer Design

Designing effective primers requires adherence to several key parameters to ensure specificity, sensitivity, and high efficiency.

- Length and Melting Temperature (Tm): Primers should be 18-30 bases long, with an optimal Tm between 58°C and 65°C [35] [36]. For two-step qPCR protocols, a Tm of 58-60°C is recommended [35]. The Tms of the forward and reverse primers should not differ by more than 2°C to ensure simultaneous binding [36].

- GC Content and Sequence: The optimal GC content is between 40% and 60% [35]. Sequences should avoid runs of identical nucleotides, particularly more than three consecutive G or C bases, and the 3' end should not contain more than two Gs or Cs in the last five nucleotides to prevent mispriming [35] [36].

- Specificity and Secondary Structures: Primers must be specific to the target sequence. Tools like NCBI BLAST should be used to verify uniqueness [35] [36]. Self-complementarity should be avoided, and the ΔG value for any potential hairpins or dimers should be weaker (more positive) than -9.0 kcal/mol [36].

Core Principles for Probe Design

Hydrolysis probes (e.g., TaqMan) must be designed with distinct criteria to ensure specific signal generation.

- Location and Melting Temperature: The probe should be located in close proximity to a primer-binding site but must not overlap with it [36]. The Tm of the probe should be 5-10°C higher than the Tm of the primers to ensure it binds before the primers [35] [36].

- Sequence and Quenching: GC content should be 30-70%, and a guanine (G) base at the 5' end should be avoided as it can quench the fluorophore reporter [35] [36]. Double-quenched probes are recommended over single-quenched probes to achieve lower background and higher signal-to-noise ratios [36].

Assay Design Considerations

- Amplicon Characteristics: The ideal amplicon length for qPCR is 70-150 base pairs, balancing efficient amplification and the need for sufficient sequence for primer/probe design [36]. For MRD detection using DNA targets, shorter fragments (50-200 bp) are more tolerant of PCR conditions and amplify quickly [35].

- Specificity for Gene Expression: When designing assays for gene expression analysis (RT-qPCR), amplicons should span an exon-exon junction where possible. This design prevents the amplification of genomic DNA, thereby ensuring that the signal originates specifically from cDNA [36].

Table 1: Summary of Primer and Probe Design Guidelines

| Parameter | Primer Guidelines | Probe Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Length | 18-30 bases [36] | 9-40 bases; 20-30 bp for single-quenched [35] [36] |

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | 58-65°C; within 2°C for primer pair [35] [36] | 5-10°C higher than primers [35] [36] |

| GC Content | 40-60% [35] | 30-70% [35] |

| Sequence to Avoid | ≤3 consecutive G/C; avoid 3' end GC-rich [35] | G at the 5' end [36] |

| Specificity Check | BLAST analysis; avoid secondary structures (ΔG > -9 kcal/mol) [36] | BLAST analysis; ensure binding to correct strand [36] |

Optimization of Amplification Efficiency

Defining and Calculating qPCR Efficiency

Amplification efficiency (E) is a critical metric in qPCR, defining the fold-increase of amplicon per cycle. An ideal reaction has 100% efficiency (E=2), meaning the product doubles every cycle [37] [38]. Efficiency is typically calculated from a standard curve of serial dilutions. The Cq values are plotted against the logarithm of the starting concentration, and the slope of the trend line is used in the equation: E = -1 + 10(-1/slope) [38]. The desired efficiency range for a well-optimized assay is 90-110% [39] [38].

Thermocycling Protocol Optimization

The thermocycling protocol can be systematically optimized to achieve high efficiency.

- Initial Denaturation/Activation: A step of 95°C for 30 seconds is often sufficient for genomic DNA. For cDNA, this can be lower. Note that hot-start polymerases may require a longer initial activation step as per the manufacturer's protocol [35].

- Denaturation: During cycling, a short denaturation step of 95°C for 5-15 seconds is adequate for most templates [35].

- Annealing and Extension: For many assays, a two-step PCR (combining annealing and extension) at 60°C for 1 minute is a good starting point [35]. The annealing temperature (Ta) should be set no more than 5°C below the primer Tm and can be optimized using a thermal gradient cycler [35] [36]. If annealing and extension are separate, the Ta should be approximately equal to the primer Tm, and the extension time is based on polymerase speed (e.g., 15-30 seconds per 100 bp) [35].

- Cycle Number: While 40 cycles is standard, this can be reduced to 30 if the amplification reaches the plateau phase early [35].

Troubleshooting Amplification Efficiency

Deviations from the ideal efficiency range indicate problems with the assay.

- Efficiency >110%: This is often caused by the presence of polymerase inhibitors in concentrated samples, which flatten the standard curve slope. Other causes include pipetting errors, inaccurate dilution series, or primer-dimer formation with intercalating dyes [38]. Remedies include diluting the sample, re-purifying the nucleic acid, and checking for A260/280 purity ratios (≥1.8 for DNA, ≥2.0 for RNA) [38].

- Efficiency <90%: This is typically due to suboptimal primer design (e.g., secondary structures, low Tm), poor probe binding, or non-optimal reagent concentrations or reaction conditions [35] [38]. Re-designing primers and probes or re-optimizing the Ta is necessary.

Table 2: Troubleshooting qPCR Amplification Efficiency

| Symptom | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Efficiency (<90%) | Poor primer/probe design, secondary structures, low Ta, reagent limitations [35] [38] | Re-design oligonucleotides; optimize Ta; check reagent quality and concentrations [35] |

| High Efficiency (>110%) | Polymerase inhibitors in sample, pipetting errors, primer dimers (SYBR Green) [38] | Dilute or re-purify sample; improve pipetting technique; use inhibitor-tolerant master mix [38] |

| Poor Reproducibility | Primer-dimer formation, assay design, pipetting inaccuracies [39] | Use double-quenched probes; ensure precise pipetting; use white wells with clear seals [35] [36] |

| Non-Homogeneous Amplification (Multiplex) | Sequence-specific efficiency differences, adapter-mediated self-priming [40] | Use deep learning tools for homogeneous library design; check for inhibitory motifs near primers [40] |

Advanced Optimization Strategies and MRD-Specific Workflow

Statistical and Computational Optimization Methods

Advanced methods can streamline the optimization process and address complex issues.

- Design of Experiments (DOE): A statistical DOE approach can efficiently optimize multiple factors simultaneously. For probe optimization, this method has been shown to increase PCR efficiency by up to 10% while significantly reducing the number of required experiments compared to a one-factor-at-a-time approach [41].

- Deep Learning for Efficiency Prediction: For multi-template PCR, such as in NGS library preparation, non-homogeneous amplification can skew results. Recent studies use one-dimensional convolutional neural networks (1D-CNNs) to predict sequence-specific amplification efficiencies, identifying specific motifs (e.g., near adapter priming sites) that cause poor amplification [40]. This allows for the design of inherently homogeneous amplicon libraries.

Application in MRD Detection: A Workflow

In MRD detection for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), qPCR of immunoglobulin (IG) and T-cell receptor (TR) gene rearrangements is a gold standard [18]. The workflow involves identifying a patient-specific clonal rearrangement at diagnosis and designing allele-specific primers for highly sensitive monitoring during remission. Adherence to international guidelines, like those from the EuroMRD Consortium, is crucial for data interpretation and quality assurance [18]. These guidelines define categories such as "quantifiable MRD," "positive below quantitative range," and "negative" to ensure consistent and accurate reporting across laboratories [18].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Assay Development

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality qPCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed solution containing DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and Mg²⁺. | Ensures consistent performance; some mixes are more tolerant of inhibitors [35] [38]. |

| Validated Primer/Probe Assays | Pre-designed and tested oligonucleotide sets for specific targets. | Saves time and optimization; available from vendors like Qiagen and Thermo Fisher [39] [42]. |

| White qPCR Plates with Ultra-Clear Seals | Plates and seals designed for optimal optical clarity and signal reflection. | Reduces light distortion and increases fluorescent signal detection [35]. |

| Nucleic Acid Isolation Kits | Kits for purifying high-quality, inhibitor-free DNA/RNA. | Critical for sample prep; ensures high purity (A260/280 ratio) [35] [38]. |

| qPCR Instrument with Gradient Function | A thermal cycler with real-time detection and temperature gradient capability. | Allows parallel optimization of annealing temperatures in a single run [35]. |

| Online Design & Analysis Tools | Free software for oligonucleotide design and analysis. | IDT's OligoAnalyzer, PrimerQuest; used for Tm calculation, secondary structure check [36]. |

| Public Primer Databases | Online repositories of published primer sequences. | PrimerBank, RT PrimerDB; provide starting points for assay design [42]. |

Within minimal residual disease (MRD) detection research, the accurate quantification of rare disease-specific nucleic acid targets is paramount. Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) serves as a cornerstone technology for this application, enabling researchers to monitor treatment efficacy and predict disease recurrence with high sensitivity. This application note provides a detailed protocol for the entire RT-qPCR workflow, framed within the context of MRD detection, to ensure precise and reliable gene expression quantification for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. The methodology outlined emphasizes robust assay design, optimized reaction conditions, and rigorous data analysis tailored to the challenges of detecting low-abundance targets.

The RT-qPCR process for MRD detection involves a series of critical steps, from sample preparation to data interpretation. The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow, highlighting the two main procedural pathways and key decision points.

RNA Isolation and Reverse Transcription

RNA Extraction and Quality Control

The accuracy of MRD detection begins with high-quality RNA. Extract RNA from patient blood or bone marrow samples using column-based purification methods or reagents like TRIzol, ensuring efficient cell lysis and RNase inactivation [43]. Critical steps include:

- DNase Treatment: Treat extracted RNA with DNase I to eliminate genomic DNA contamination, which is a significant source of false positives in MRD detection [43].

- Quality Assessment: Evaluate RNA integrity and purity using spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio of 1.8-2.0) and agarose gel electrophoresis [44]. High-quality RNA is essential for reliable cDNA synthesis.

Reverse Transcription to cDNA

Convert purified RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) using reverse transcriptase enzymes (e.g., M-MLV or AMV) [43]. The choice of priming strategy affects cDNA representation and assay sensitivity:

- Oligo(dT) Primers: Prime reverse transcription from the poly-A tails of mRNA, suitable for amplifying protein-coding genes [45].

- Random Hexamers: Prime throughout the RNA transcriptome, enabling detection of non-polyadenylated transcripts and providing more comprehensive coverage [45].

- Gene-Specific Primers: Offer the highest sensitivity for specific MRD targets but limit analysis to predefined genes [43].

Table 1: Comparison of One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR Approaches

| Parameter | One-Step RT-qPCR | Two-Step RT-qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Procedure | Reverse transcription and PCR amplification occur in a single tube [43] | Reverse transcription and PCR amplification are performed in separate tubes [43] |