Optimizing Exclusion Volume Placement in Structure-Based Pharmacophores: A Guide for Enhanced Virtual Screening and Drug Design

Structure-based pharmacophores are powerful tools in computer-aided drug discovery for identifying novel lead compounds.

Optimizing Exclusion Volume Placement in Structure-Based Pharmacophores: A Guide for Enhanced Virtual Screening and Drug Design

Abstract

Structure-based pharmacophores are powerful tools in computer-aided drug discovery for identifying novel lead compounds. A critical, yet often underexplored, component of these models is the strategic placement of exclusion volumes, which represent sterically forbidden regions in the binding pocket. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing exclusion volume placement. We cover the foundational role of exclusion volumes in defining binding site shape, methodological best practices for their generation from protein-ligand complexes and apo structures, troubleshooting common pitfalls like over-constraining models, and rigorous validation techniques using enrichment factors and molecular dynamics. By synthesizing these aspects, this article aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to create more selective and effective pharmacophore models, thereby improving the success rate of virtual screening campaigns in lead identification and optimization.

The Critical Role of Exclusion Volumes in Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Fundamental Concepts

Q1: What is an exclusion volume in the context of a structure-based pharmacophore? An exclusion volume (XVOL) is a steric constraint in a pharmacophore model that represents regions in space a ligand cannot occupy due to potential van der Waals (VDW) clashes with the protein target's atoms [1] [2]. They are typically visualized as spheres placed on the protein atoms that define the binding pocket, effectively mapping the negative image of the receptor's shape to prevent false-positive hits during virtual screening by sterically excluding molecules that are too large [1] [2].

Q2: How do exclusion volumes differ from other pharmacophore features like hydrogen bond acceptors? While features like hydrogen bond acceptors (Acc) or donors (Don) define the positive interactions a ligand must have with the target, exclusion volumes define negative constraints [2]. They ensure that a potential binder not only possesses the necessary functional groups for favorable interactions but also has a shape and size complementary to the binding cavity, thereby improving the selectivity of the virtual screening process [1].

Q3: When should a "double shell" or "exclusion volume coat" be used? A second shell of exclusion volumes can be added for more rigorous steric screening [3]. This advanced technique accounts for the dynamic nature of proteins and the VDW radii of atoms. It is particularly useful for defining binding pockets with higher precision, potentially reducing false positives by simulating a tighter steric fit.

Practical Implementation

Q4: From which protein structure should I generate exclusion volumes: the apo or holo form? The holo form (protein structure with a bound native ligand or inhibitor) is generally preferred [2]. The binding site in a holo structure often represents the biologically relevant, ligand-compatible conformation. Using an apo (empty) structure might result in a binding site that is too constricted, as side chains may collapse into the cavity. If only an apo structure is available, careful analysis and potential refinement of the binding site residues are recommended.

Q5: Can exclusion volumes be automatically generated, and how can the results be validated? Yes, most modern molecular modeling software like MOE and LigandScout include functions for the automatic placement of exclusion volumes based on the protein atoms lining the binding site [1] [3]. The results should always be validated by ensuring that:

- The known native ligand fits within the defined volumes without significant clashes.

- The volumes accurately trace the topography of the binding pocket without creating artificially large or obstructive barriers that would exclude legitimate binders.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Known Active Compounds are Excluded by the Pharmacophore Model

Problem: During validation, a known active compound or the native ligand from the crystal structure is not retrieved by your pharmacophore query because it clashes with one or more exclusion volumes.

Resolution Steps:

- Visual Inspection: Visually inspect the clash between the ligand and the exclusion volume. Determine if it is a minor, peripheral clash or a severe, core clash.

- Check Protein Flexibility: Identify the specific protein residue responsible for the exclusion volume. Consult literature or databases to see if this residue has known flexibility or multiple side-chain conformations.

- Adjust Exclusion Volume Radius: Slightly reduce the radius of the specific exclusion volume sphere causing the clash. The default radius is often based on a full VDW radius, which can be overly restrictive.

- Remove Non-Critical Volumes: If the clash is with an atom from a flexible side chain on the periphery of the binding site, consider removing that individual exclusion volume. Prioritize volumes from the protein backbone, which is less flexible.

Root Cause Analysis:

- Overly Restrictive Volumes: Default settings may use full atomic VDW radii without accounting for protein or ligand flexibility.

- Rigid Protein Assumption: The model assumes a rigid protein structure, while in reality, binding sites can adapt to different ligands (induced fit).

Issue 2: Pharmacophore Model Retrieves Too Many False Positives

Problem: The virtual screening returns a high number of hits that fit the chemical features (e.g., H-bond donors, hydrophobic areas) but have poor shape complementarity with the binding pocket, leading to many non-binders.

Resolution Steps:

- Verify Binding Site Definition: Ensure the binding site used to generate the pharmacophore is correctly defined and encompasses all key residues.

- Add an Exclusion Volume Coat: Implement a second shell of exclusion volumes to create a tighter steric definition of the pocket [3].

- Review Feature Selection: Ensure your pharmacophore model includes all essential chemical features. An under-defined model (too few features) is more likely to retrieve false positives, even with proper exclusion volumes.

- Increase Search Rigor: If your software allows, increase the stringency of the pharmacophore search, requiring a more precise match to both the chemical features and the exclusion volume constraints.

Root Cause Analysis:

- Under-Defined Steric Environment: The exclusion volumes may not fully encapsulate the binding site's shape, leaving gaps where ligand atoms can inappropriately occupy protein space.

- Insufficient Chemical Constraints: The model may lack key chemical features, making it too permissive.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Generating a Structure-Based Pharmacophore with Exclusion Volumes in MOE

This protocol details the creation of a pharmacophore from a protein-ligand complex using the Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) software [1] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| MOE Software | The primary computational platform for protein preparation, analysis, and pharmacophore generation [1] [4]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) File | The source of the high-resolution 3D structure of the protein-ligand complex (e.g., PDB ID: 5RL7) [3]. |

| Protein Preparation Wizard (MOE) | Used to add hydrogen atoms, correct protonation states, and optimize the protein structure for subsequent steps [2]. |

| Protein Contacts Application (MOE) | Analyzes the protein-ligand interface to detect ionic, H-bond, and other key contacts for feature generation [1]. |

SVL Script: ph4_from_ppi.svl |

An automated script in MOE that creates the pharmacophore query based on the contacts detected by the Protein Contacts application [1]. |

Methodology:

- Protein Structure Preparation:

- Obtain your target protein-ligand complex structure from the PDB.

- In MOE, use the QuickPrep module or similar to:

- Add missing hydrogen atoms.

- Assign protonation states at a physiological pH (e.g., 7.4).

- Perform a quick energy minimization to relieve any steric clashes.

- Binding Site Analysis:

- Visually inspect the binding site using the SiteView to confirm the ligand's position and key residues.

- Use the Protein Contacts application to detect and list all non-covalent interactions (ionic, H-bond, arene-arene) between the ligand and the protein atoms [1].

- Automatic Pharmacophore Generation:

- Run the SVL function

ph4_from_ppi.svl(or the equivalent built-in function in your MOE version). This script will:

- Run the SVL function

- Model Refinement:

- Manually review the automatically generated features and exclusion volumes.

- Remove any redundant or non-essential pharmacophore features.

- Adjust the radius of exclusion volumes if necessary, especially for flexible side chains.

Protocol 2: Creating a Joint Pharmacophore Query from Multiple Fragments using LigandScout

This protocol, inspired by the FragmentScout workflow, aggregates information from multiple fragment screens into a single, powerful pharmacophore model [3].

Methodology:

- Data Set Curation:

- Collect a set of pre-aligned PDB files from a high-throughput crystallographic fragment screen (e.g., from an XChem experiment) [3].

- Individual Model Generation:

- Import each PDB structure into LigandScout's structure-based perspective.

- For each structure, automatically generate a pharmacophore model. This will include interaction features from the fragment and exclusion volumes based on the protein pocket [3].

- Query Alignment and Merging:

- In the alignment perspective of LigandScout, select all individual pharmacophore queries.

- Align and merge them using the "based-on reference points" option. This creates a joint pharmacophore query.

- Feature Interpolation and Consolidation:

- The final step is the interpolation of all features (both chemical features and exclusion volumes) within a defined distance tolerance [3]. This results in a consensus model where consistently present features are reinforced, and the exclusion volume field represents the unified steric environment from all fragment structures.

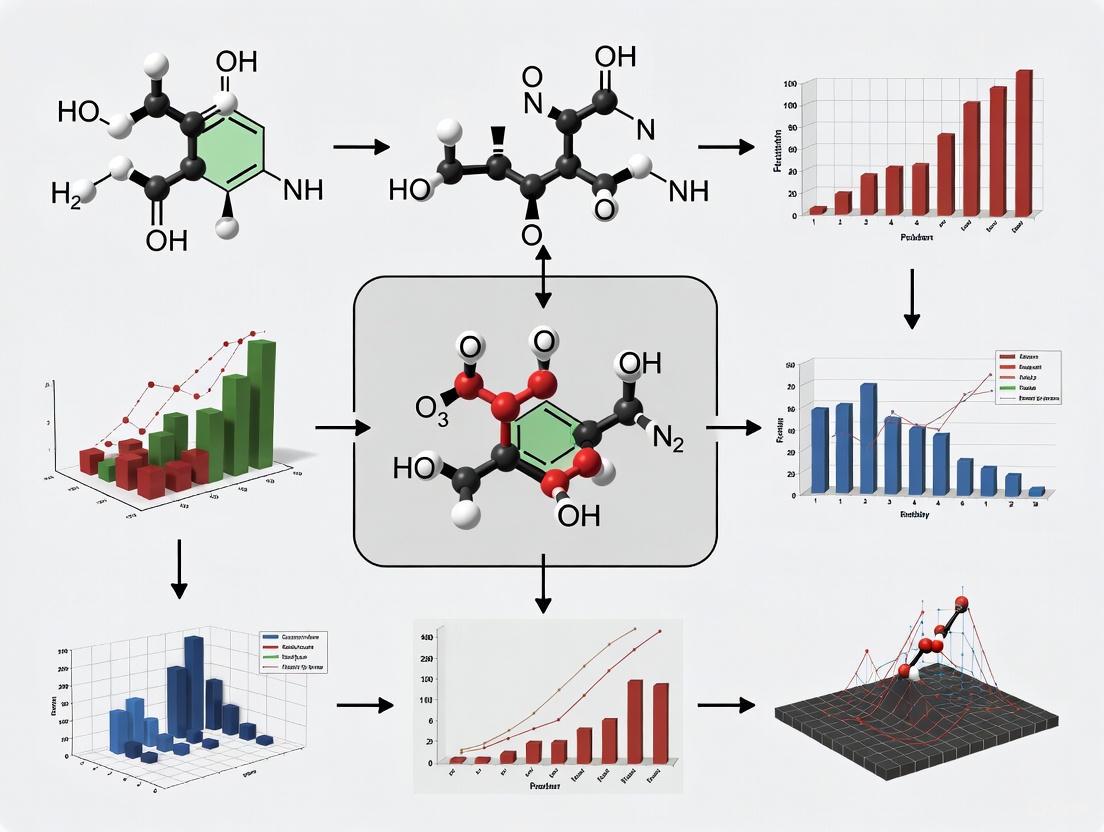

Workflow Diagram: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Generation

Quantitative Data Reference

Table 1: Exclusion Volume Implementation in Different Software Platforms

| Software Platform | Method of XVOL Generation | Key Configurable Parameters | Primary Use-Case Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MOE | Automated from protein atoms in the binding site via SVL script [1]. | Sphere radius, protein atoms selection. | Standard structure-based pharmacophore modeling from a single complex [1]. |

| LigandScout | Automated from protein structure; can be merged from multiple aligned structures [3]. | Distance tolerance for merging, exclusion volume coat (secondary shell) [3]. | Creating consensus models from multiple fragment poses (FragmentScout workflow) [3]. |

| FragmentScout Workflow | Aggregated from multiple XChem fragment screening structures to form a joint steric definition [3]. | Number of fragment structures, clustering method. | Integrating sparse structural data from fragment-based screening campaigns [3]. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Exclusion Volume (XVOL) Parameters

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Proposed Adjustment | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Known active ligand is excluded | Overly restrictive radii on flexible side chains [2]. | Reduce the radius (e.g., by 0.2-0.5 Å) or remove the specific XVOL. | Ligand is correctly included in the hit list. |

| High number of sterically implausible hits | Under-defined steric environment or insufficient XVOL coverage [1]. | Add an "exclusion volume coat" (secondary shell) [3] or review binding site definition. | Increased shape selectivity; reduction in false positives. |

| Model performance varies greatly between similar protein structures | Sensitivity to minor conformational changes in the binding site. | Generate a consensus XVOL model from multiple holo structures. | A more robust and generalizable pharmacophore model. |

In the realm of computer-aided drug discovery, virtual screening serves as a cornerstone for identifying novel lead compounds. A key component that significantly influences the success of virtual screening is the implementation of steric constraints, often referred to as exclusion volumes. These constraints are not merely technical parameters but fundamental elements that define the shape and physical boundaries of a target's binding site, profoundly impacting both hit rates and specificity.

Steric constraints are three-dimensional representations of regions in space that a ligand cannot occupy due to van der Waals clashes with the target protein. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), a pharmacophore is "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure" [2]. This definition inherently includes steric considerations, which are implemented in pharmacophore modeling as exclusion volumes (XVOL) that mimic the binding site and into which a molecule is not allowed to protrude to avoid steric clashes with the target [5].

The proper application of these constraints is crucial for optimizing virtual screening campaigns, as they directly influence the ability to distinguish true actives from decoy compounds, reduce false positives, and enhance the enrichment of biologically relevant hits.

Technical FAQs: Implementing Steric Constraints

Q1: What are exclusion volumes and how do they improve virtual screening specificity?

A1: Exclusion volumes (XVOL) are spatial constraints in pharmacophore models that represent regions occupied by the protein structure where ligand atoms cannot penetrate. They explicitly model the steric environment of the binding pocket by placing van der Waals spheres on protein atoms that make up the binding site, indicating regions in space that small-molecule binders cannot occupy because of steric clashes [1]. The automated inclusion of excluded volumes to pharmacophore models provides a more selective model to reduce false positives and achieves better enrichment rates in virtual screening [6]. By penalizing molecules that occupy steric regions not occupied by active molecules, these constraints significantly enhance screening specificity.

Q2: How do I determine optimal placement and radius for exclusion volumes?

A2: Optimal exclusion volume placement requires careful analysis of the protein-ligand complex structure. The process involves these key steps:

- Analyze the 3D structure of the target protein, preferably from X-ray crystallography or homology modeling [2]

- Identify key residues forming the binding pocket and their atomic coordinates

- Place exclusion volumes on protein atoms lining the binding cavity, typically using their van der Waals radii as initial guidance

- Adjust radii based on known active and inactive compounds to fine-tune specificity

Advanced methods incorporate molecular dynamics simulations to account for protein flexibility in exclusion volume placement [7]. Tools like LigandScout and Catalyst's HypoGenRefine algorithm can automate this process by deriving excluded volumes directly from protein-ligand complex structures [6] [8].

Q3: What are common pitfalls when using steric constraints that reduce hit rates?

A3: The most common pitfalls include:

- Over-constraining the model: Applying too many or overly large exclusion volumes can eliminate true active compounds that might induce slight side-chain movements [9]

- Ignoring protein flexibility: Using a single rigid protein conformation fails to account for adaptive binding site changes, potentially excluding valid binders [9]

- Inaccurate binding site definition: Poor characterization of the actual binding pocket leads to misplaced constraints [2]

- Inappropriate constraint radii: Using default values without target-specific optimization reduces model accuracy

These issues typically manifest as unexpectedly low hit rates during virtual screening, with subsequent experimental validation showing false negative results.

Troubleshooting Guide: Steric Constraint Optimization

Problem: High False Positive Rate in Virtual Screening

Symptoms: Virtual screening returns numerous hits, but experimental validation shows low confirmation rates. The identified compounds fit the pharmacophoric features but demonstrate poor binding affinity due to steric clashes not accounted for in the model.

Solutions:

- Add exclusion volumes: Incorporate excluded volume features based on the 3D protein structure to represent sterically forbidden regions [6] [10]

- Implement shape constraints: Use the overall volume and shape of the binding pocket as an additional filter [5] [1]

- Validate with decoy sets: Test the model against known inactive compounds to optimize exclusion parameters [8]

Problem: Overly Restrictive Model Excluding Known Actives

Symptoms: The virtual screening fails to identify known active compounds, and the hit list is exceptionally small or empty, indicating excessive constraint stringency.

Solutions:

- Adjust constraint tolerances: Increase the radius tolerance for exclusion volumes by 0.5-1.0 Å to allow for minor structural flexibility [9]

- Employ multiple conformations: Use an ensemble of protein structures from molecular dynamics simulations to create a more flexible steric environment [7] [9]

- Focus on core constraints: Identify and retain only essential exclusion volumes through systematic validation with known actives and inactives

Problem: Inconsistent Performance Across Diverse Compound Libraries

Symptoms: The model performs well with certain chemical classes but fails with others, particularly scaffold-divergent compounds.

Solutions:

- Implement multi-conformer constraints: Generate exclusion volumes from multiple protein conformations to accommodate different binding modes [9]

- Use target-biased scoring: Develop target-specific constraint parameters based on known binding patterns for the target class [9]

- Combine with ligand-based approaches: Integrate structure-based steric constraints with ligand-based similarity metrics to improve generalizability [5]

Experimental Protocols & Performance Data

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Exclusion Volume Implementation

This protocol details the generation of steric constraints from protein-ligand complex structures using tools like LigandScout [8]:

- Protein Preparation: Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein from PDB (www.rcsb.org). Prepare the structure by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning proper protonation states, and fixing missing residues [2]

- Binding Site Analysis: Define the binding site residues through analysis of the native ligand or using cavity detection algorithms like GRID or LUDI [2]

- Exclusion Volume Placement: Automatically generate exclusion volumes by mapping the van der Waals surfaces of all binding site atoms within 5Å of the native ligand [8]

- Feature Selection: Manually refine automatically placed constraints, removing redundant exclusion volumes while retaining those critical for specificity

- Model Validation: Validate the model using a set of known active and decoy compounds. Calculate enrichment factors (EF) and area under ROC curve (AUC) to quantify performance [8]

Protocol 2: MD-Based Flexible Constraint Generation

For targets with significant flexibility, this protocol generates dynamic steric constraints:

- System Setup: Prepare the protein structure in solvated conditions with appropriate ion concentration [7]

- Druggability Simulations: Perform molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (≥40ns) with probe molecules representing drug-like fragments [7]

- Trajectory Analysis: Use tools like Pharmmaker to analyze binding events and identify consistent steric boundaries across simulation frames [7]

- Consensus Constraints: Generate exclusion volumes that represent regions consistently unavailable to probes throughout the simulation

- Dynamic Model Creation: Incorporate flexibility by creating multiple pharmacophore models representing different conformational states [9]

Quantitative Performance of Steric Constraints

Table 1: Impact of Exclusion Volumes on Virtual Screening Performance

| Target Protein | Method | Without XVOL | With XVOL | Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XIAP | Structure-based pharmacophore | EF1% = 5.0 | EF1% = 10.0 | 100% increase | [8] |

| CDK2 | HypoGenRefine | Specificity = 65% | Specificity = 89% | 24% increase | [6] |

| Human DHFR | HypoGenRefine | False Positive Rate = 32% | False Positive Rate = 11% | 66% reduction | [6] |

| COX | Comparative VS | AUC = 0.85 | AUC = 0.98 | 15% increase | [5] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Virtual Screening Methods with Steric Constraints

| Screening Method | Hit Rate | Specificity | Best Use Cases | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore with XVOL | 5-15% | High | Targets with well-defined binding pockets | Limited flexibility handling |

| Docking | 1-10% | Medium-high | Structure-based design | Scoring function accuracy |

| Shape-based | 3-12% | Medium | Scaffold hopping | Limited electronic features |

| 2D Similarity | 2-8% | Low-medium | Ligand-based screening | Limited steric consideration |

Advanced Applications & Integration

Integration with Molecular Docking

Steric constraints significantly enhance docking-based virtual screening by pre-filtering compound libraries before the computationally intensive docking process [9]. This integrated approach:

- Reduces the library size by 60-90% through pharmacophoric filters including exclusion volumes [9]

- Improves docking accuracy by eliminating compounds with obvious steric clashes

- Enables focused docking on sterically permissible regions of the binding site

Multi-Conformer Ensemble Approaches

Advanced implementations account for protein flexibility through ensemble-based steric constraints:

- Multiple crystal structures: Generate exclusion volumes from multiple ligand-bound conformations when available [9]

- Molecular dynamics snapshots: Extract representative structures from MD trajectories to create dynamic exclusion volume maps [7]

- Normal mode analysis: Use low-frequency modes to predict alternative binding site conformations for constraint generation [7]

Machine Learning Enhancement

Emerging approaches combine traditional steric constraints with machine learning:

- Develop target-class-specific exclusion parameters through analysis of known binding patterns [9]

- Predict optimal constraint tolerances based on protein flexibility metrics

- Generate improved scoring functions that better integrate steric compatibility measures [9]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools for Implementing Steric Constraints in Virtual Screening

| Tool/Software | Type | Function in Steric Constraints | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software | Generates exclusion volumes from protein-ligand complexes | Commercial [5] [8] |

| Pharmmaker | Web Tool | Creates pharmacophore models from MD trajectories | Free [7] |

| MOE | Software Suite | Automated pharmacophore generation with exclusion volumes | Commercial [1] |

| Catalyst/HypoGen | Algorithm | Automated addition of excluded volumes to pharmacophores | Commercial [6] |

| GRID | Program | Detects favorable and unfavorable interaction regions | Commercial [2] |

| ZINC Database | Compound Library | Source of screening compounds with 3D structures | Free [8] |

| PDB | Database | Source of protein structures for constraint derivation | Free [2] |

| DruGUI | Tool | Setup and analysis of druggability simulations | Free [7] |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Exclusion Volume Optimization Workflow. This workflow illustrates the iterative process of developing and refining steric constraints for structure-based pharmacophore models, highlighting the critical role of exclusion volumes in enhancing virtual screening specificity.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key software tools and databases essential for research in structure-based pharmacophore modeling and binding site analysis.

| Reagent/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) | Software Suite | Used for automated generation of pharmacophore queries from protein-protein interfaces, virtual screening, and analysis of antibody-antigen complexes [1]. |

| Pharmit | Online Tool | Interactive pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening tool; used to generate pharmacophore JSON files from ligand structures for subsequent analysis [11]. |

| ConPhar | Open-source Informatics Tool | Specifically designed to extract, cluster, and generate consensus pharmacophore models from multiple pre-aligned ligand-target complexes [11]. |

| ZINC Database | Chemical Database | A curated collection of commercially available chemical compounds used for virtual screening to identify potential lead molecules [8]. |

| PHASE (Schrödinger Suite) | Software Module | Used for structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore model generation, feature assignment, and high-throughput virtual screening [12]. |

| SiteMap (Schrödinger Suite) | Software Module | Analyzes binding sites to characterize regions in terms of hydrophobicity, hydrogen bonding, etc.; helps differentiate between feature types [12]. |

| AMBER | Software Suite | Performs molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to sample water molecule positions and interactions within a binding pocket for water-based pharmacophore generation [12]. |

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Database | The primary repository for experimentally-determined 3D structures of proteins and protein-ligand complexes, serving as the essential starting point [2] [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

Feature Selection and Definition

Q1: My pharmacophore model is too restrictive and filters out known active compounds. What features might be non-essential? A: A model with excessive features can be overly selective.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Identify Conserved Interactions: If you have multiple protein-ligand complex structures, analyze them to identify which interactions are consistently present. Features that are not conserved across multiple active ligands may be non-essential [11].

- Energy Analysis: In structure-based modeling, rank the detected interactions by their calculated contribution to the binding energy. Consider removing features with weak energetic contributions [2].

- Feature Redundancy Check: Check if multiple features are representing the same type of interaction with the same protein residue. One might be sufficient.

- Test with Known Actives: Use a small set of known active compounds to validate your model. If they are not retrieved, systematically remove one feature at a time and re-run the screening to identify which feature is causing the exclusion.

Q2: How can I create a pharmacophore model when no known ligands are available for my target? A: You can use a structure-based approach that does not rely on pre-existing ligand information.

- Experimental Protocol: Water Pharmacophore Generation via Molecular Dynamics [12]

- Structure Preparation: Obtain the apo (unliganded) protein structure from the PDB and prepare it using standard software (e.g., Protein Preparation Wizard in Schrödinger). This involves adding hydrogens, assigning protonation states, and energy minimization.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation: Perform an MD simulation of the protein solvated in a water box (e.g., using AMBER). Restrain the protein's heavy atoms to sample water molecules in the binding site without a ligand present.

- Hydration Site Analysis (HSA): Analyze the MD trajectory to identify "hydration sites"—localized regions where water molecules reside for a significant duration. These sites often correspond to energetically favorable interaction points.

- Pharmacophore Feature Assignment: Assign pharmacophore features to each high-occupancy hydration site based on its thermodynamic and hydrogen-bonding characteristics:

- H-Bond Acceptor: Sites with favorable enthalpy (< -8.0 kcal/mol), acceptor ratio >100%, and donor ratio <50%.

- H-Bond Donor: Sites with favorable enthalpy (< -8.0 kcal/mol), donor ratio >100%, and acceptor ratio <50%.

- Hydrophobic: Sites with low hydrogen-bonding propensity (acceptor & donor ratios <100%) and favorable interaction with hydrophobic probes.

- Model Optimization: Optimize the positions of the assigned features via energy minimization or hydrogen-bond-constrained docking of small molecules (e.g., water, methane).

Exclusion Volume Optimization

Q3: How do I determine the optimal size and placement of exclusion volumes to define the binding site shape without making the model too rigid? A: Exclusion volumes are critical for representing the steric boundaries of the binding pocket.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Source of Volumes: The most direct method is to generate exclusion volumes from the protein atoms that line the binding pocket. Software like MOE can automatically place Van der Waals (VDW) spheres on these atoms [1].

- Radius Adjustment: The default radius for an exclusion volume sphere is often the VDW radius of the atom. If the model is too strict, consider slightly increasing the radius (e.g., by 0.5-1.0 Å) to create a softer, more permissive steric boundary. Conversely, decrease the radius if the model is too promiscuous.

- Consensus from Multiple Structures: If multiple protein structures are available (e.g., from an MD simulation), generate exclusion volumes for each structure and use a consensus approach. This creates a more averaged and potentially more robust definition of the binding site's steric environment, accommodating minor flexibility [12].

- Validation with Decoys: Test your model's ability to discriminate known active compounds from decoy molecules (inert compounds) using a dataset like DUD. Tune the exclusion volume parameters to maximize the enrichment factor [8].

Model Validation and Performance

Q4: How can I validate my pharmacophore model before proceeding with large-scale virtual screening? A: Proper validation is crucial to ensure the model's predictive power.

- Experimental Protocol: Validation using a Decoy Set [8]

- Prepare Test Sets: Compile a set of known active compounds (10-50) for your target. Generate a set of decoy molecules (typically hundreds to thousands) that are physically similar but chemically different to the actives (databases like DUD provide pre-compiled sets).

- Run the Screening: Merge the active and decoy sets and screen them against your pharmacophore model.

- Generate ROC Curve: Plot the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, which shows the true positive rate against the false positive rate as the screening threshold is varied.

- Calculate Performance Metrics:

- AUC (Area Under the Curve): A value of 1.0 indicates perfect separation, while 0.5 indicates a random model. A value above 0.7-0.8 is generally considered acceptable [8].

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Measures the concentration of active compounds found in the top fraction of the screening hits compared to a random selection. For example, EF1% is the enrichment in the top 1% of the screened library. A high EF indicates good model performance [8].

Q5: My pharmacophore model has good enrichment but the hit compounds from virtual screening have poor drug-like properties. How can I address this? A: This indicates a disconnect between the model's interaction mapping and desired compound qualities.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Incorporate Property Filtering: Integrate filters for key physicochemical properties (e.g., Molecular Weight, LogP, number of hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, rotatable bonds) directly into your virtual screening workflow. This can be done before or after the pharmacophore screening.

- Use ADMET Prediction: Employ in-silico tools to predict Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties of the hit compounds. Prioritize molecules with favorable ADMET profiles [8].

- Refine the Exclusion Volumes: Poor drug-likeness can sometimes stem from molecules with awkward steric bulk. Revisiting and optimizing the exclusion volume placement can help select for more compact and lead-like compounds [1].

Advanced Integration Techniques

Q6: How can I create a single, robust pharmacophore model from multiple diverse ligands bound to the same site? A: A consensus model that integrates features from multiple complexes can provide a more holistic view of the binding site's requirements.

- Experimental Protocol: Building a Consensus Pharmacophore with ConPhar [11]

- Prepare Complexes: Collect and align multiple 3D structures of your target protein in complex with different ligands (from the PDB).

- Extract Individual Pharmacophores: For each protein-ligand complex, extract the ligand's structure and generate a pharmacophore model (e.g., using Pharmit to create a JSON file).

- Feature Consolidation: Use the ConPhar tool to parse all the individual pharmacophore JSON files. The tool will consolidate the features into a single data structure.

- Cluster and Generate Consensus: ConPhar will cluster the pharmacophoric features from all ligands based on their type and spatial location. The consensus model is built from the most representative features from each cluster, capturing the essential interactions shared across multiple ligands.

Experimental Workflow for Holistic Binding Site Modeling

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for creating and validating a holistic pharmacophore model, integrating the key concepts from the FAQs.

Diagram: Holistic Pharmacophore Model Development

Deriving Exclusion Volumes from Protein-Ligand Complexes vs. Apo Structures

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between using an apo structure versus a holo structure for deriving exclusion volumes? The fundamental difference lies in the representation of the protein's binding site. An apo structure (without a bound ligand) shows the protein's inherent, unoccupied state, which may contain binding site conformations that are not compatible with ligand binding. In contrast, a holo structure (with a bound ligand) provides a direct observation of the steric and chemical environment that accommodates a specific ligand. Using a holo structure allows for the direct derivation of exclusion volumes based on the atomic positions of the bound ligand and the induced protein conformation, which often more accurately reflects the steric constraints of a functional binding event [6] [13].

FAQ 2: My docking results using apo-structure-derived exclusion volumes show many false positives. What is the likely cause? This is a common issue. The likely cause is that the binding site in your apo protein structure is in a conformation that is more open or structurally distinct from the ligand-bound (holo) state. The side chains, in particular, can adopt significantly different conformations in the absence of a ligand [14]. The exclusion volumes derived from the apo structure may therefore penalize poses that are actually biologically relevant because they clash with side-chain rotamers that shift upon ligand binding. To resolve this, try generating exclusion volumes from a holo structure of the same protein, if available, or from a high-quality predicted protein-ligand complex [13].

FAQ 3: Can I use a predicted protein structure, like one from AlphaFold, to generate exclusion volumes? Yes, but with caution. Standard AlphaFold2 predictions typically generate apo-like structures. However, AlphaFold3 can predict protein-ligand complex structures when provided with a ligand input. Studies show that using an active ligand as input to AlphaFold3 can generate a holo-like structure that improves virtual screening outcomes compared to using an apo structure [13]. The key is to provide a relevant ligand during the prediction to induce a more biologically accurate binding site conformation.

FAQ 4: Why do my generated exclusion volumes sometimes block known active compounds during virtual screening? This can happen if the exclusion volumes are derived from a single, specific holo structure. The defined volumes might be overly restrictive for chemically distinct but still active ligands that bind in a slightly different orientation or induce a minor conformational change. To troubleshoot, consider using a consensus approach. Generate exclusion volumes from multiple holo structures with different bound ligands to create a more generalized model of the sterically forbidden regions, or slightly reduce the van der Waals radius scaling when defining the volumes [6].

FAQ 5: How significant are side-chain conformational changes compared to backbone movements when deriving exclusion volumes? Extremely significant. Large-scale analyses of apo-holo protein pairs reveal that backbone movements are often minimal (often less than 0.5 Å RMSD), while side-chain conformations in the binding site frequently undergo significant rearrangements upon ligand binding [14]. This means that the primary source of steric clash errors often comes from side-chain atoms, not the protein backbone. This underscores the importance of using a structure where the binding site side chains are in a relevant conformation for deriving accurate exclusion volumes.

Quantitative Comparison: Apo vs. Holo Structure Characteristics

The table below summarizes key structural differences that impact exclusion volume derivation.

Table 1: Structural Characteristics of Apo vs. Holo Protein Structures

| Feature | Apo Structure (Ligand-Free) | Holo Structure (Ligand-Bound) | Implication for Exclusion Volumes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Site Conformation | Often more open or collapsed; may represent low-energy state without ligand [14] | Represents the induced fit conformation stabilized by the ligand [14] | Holo structures provide a more accurate steric map of the occupied binding pocket. |

| Backbone Flexibility (Cα RMSD) | Inherent variation is similar to holo states [14] | Induced change from apo to holo is typically small (<0.5 Å) [14] | Backbone contribution to exclusion volumes is relatively consistent. |

| Side-Chain Conformations (χ1 angles) | Samples a certain range of rotamers [14] | Frequently pushed into new orientations outside the apo range [14] | This is a critical difference; apo-derived side-chain volumes can be highly inaccurate. |

| Utility in Virtual Screening | May lead to poorer enrichment and more false positives due to steric clashes [13] | Generally leads to better screening performance by reducing false positives [13] | Using a holo structure is the preferred method when possible. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Deriving Exclusion Volumes from a Single Holo Crystal Structure

This is the most direct method when a high-resolution co-crystal structure is available.

Structure Preparation:

- Obtain your protein-ligand complex (holo) structure from a database like the PDB.

- Using molecular visualization software (e.g., Maestro, MOE, or PyMOL), remove the native ligand from the binding site.

- Prepare the protein structure by adding hydrogens, assigning bond orders, and optimizing the protonation states of residues at the desired pH.

Identification of Exclusion Volumes:

- The software will automatically define exclusion volumes based on the coordinates of the protein atoms in the prepared holo structure.

- These volumes are typically generated by assigning a van der Waals radius to each atom and creating a combined steric field.

Volume Adjustment (Optional):

- Some software allows you to scale the van der Waals radii used to generate the volumes. A slight scaling (e.g., 0.9-1.0) can be applied to fine-tune the steric constraints.

- Visually inspect the generated volumes against the native ligand to ensure they reasonably represent the occupied space.

Protocol 2: Generating a Consensus Exclusion Model from Multiple Structures

This method creates a more robust and generalized steric model, which is useful for screening against diverse chemotypes.

Dataset Curation:

- Collect multiple high-resolution holo crystal structures of the same protein bound to different ligands.

- Align these structures based on the protein backbone atoms of the binding site region.

Superposition and Volume Calculation:

- Superimpose the prepared protein structures (with ligands removed).

- Use the pharmacophore generation software to calculate exclusion volumes based on the superposed set of structures.

- The software will create a consensus volume that represents sterically forbidden space common to all or most of the ligand-bound states.

Model Validation:

- Validate the consensus model by checking if known active ligands can be mapped onto the corresponding pharmacophore without violating the exclusion volumes, while known inactive compounds may show steric clashes.

Protocol 3: Using AlphaFold3 for Holo-like Structure Prediction

When an experimental holo structure is unavailable, this protocol uses AF3 to generate a model.

Input Preparation:

- Provide the amino acid sequence of your target protein to AlphaFold3.

- Crucially, also provide a known active ligand as input. Studies indicate that using an active ligand, as opposed to a decoy or no ligand, significantly improves the quality of the predicted holo structure for virtual screening [13].

Structure Prediction and Selection:

- Run the AlphaFold3 prediction.

- Analyze the ranking of the generated models and select the one with the highest predicted confidence score that shows a plausible binding mode.

Derivation of Exclusion Volumes:

- Process the selected AlphaFold3-predicted complex as you would an experimental holo structure (see Protocol 1).

- Remove the predicted ligand and generate exclusion volumes from the protein coordinates of the predicted binding site.

Workflow Diagram: Decision Process for Exclusion Volume Derivation

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for choosing the best approach to derive exclusion volumes for your project.

Table 2: Key Resources for Working with Exclusion Volumes and Pharmacophores

| Resource / Reagent | Function / Description | Relevance to Exclusion Volumes |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | A repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids. | The primary source for obtaining both apo and holo protein structures for analysis and volume derivation [14]. |

| AlphaFold3 | An AI system that predicts the 3D structure of protein-ligand complexes. | Used to generate predicted holo structures when experimental ones are lacking, providing a superior starting point over apo structures for volume derivation [13]. |

| Molecular Preparation Software (e.g., Maestro-Protein Prep, MOE-QuickPrep) | Tools for adding hydrogens, correcting bonds, and optimizing side-chain conformations in protein structures. | Critical for ensuring the protein structure used for volume calculation is in a realistic, energetically favorable state. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software (e.g., Catalyst, Phase) | Software platforms capable of identifying chemical features and generating exclusion volumes from protein structures. | The essential tool where exclusion volumes are defined, calculated, and integrated into the pharmacophore hypothesis [6]. |

| Known Active Ligands | Small molecules with confirmed biological activity against the target. | Used as input for AlphaFold3 to predict a more accurate holo structure, or for validating generated exclusion volumes by checking for steric fit [13]. |

Practical Strategies for Generating and Placing Exclusion Volumes

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions (FAQs) for researchers working on structure-based pharmacophore modeling, with a special emphasis on optimizing exclusion volume placement.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common sources of error in the initial protein structure that can negatively impact exclusion volume placement?

Errors often originate from the quality of the input protein structure [15]. Common issues include:

- Missing residues or atoms: Gaps in the protein backbone or side chains can lead to an inaccurate definition of the binding site cavity, causing exclusion volumes to be placed in areas that are actually accessible [15] [2].

- Incorrect protonation states: The lack of correct hydrogen atoms or improper protonation states of key residues (e.g., Histidine) can distort the electronic environment and interaction maps, leading to a flawed pharmacophore model [2] [16].

- Poor resolution in the binding site: If the experimental electron density for the binding site region is weak or ambiguous, the atomic model might be inaccurate, directly affecting the precision of derived exclusion volumes [15].

Q2: My pharmacophore model is too restrictive and filters out known active compounds during virtual screening. How can I optimize the exclusion volumes to improve hit rates?

An overly restrictive model is often due to excessive or incorrectly sized exclusion volumes.

- Diagnosis: Validate your model using a set of known active and decoy compounds. A poor enrichment factor (EF) and Area Under the Curve (AUC) in Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analysis can indicate this issue [17] [18].

- Solution:

- Adjust Exclusion Volume Granularity: Instead of using a large, contiguous set of exclusion spheres, try a finer-grained approach. Use smaller spheres that more precisely define the van der Waals surface of the binding site atoms.

- Remove Redundant Volumes: Manually inspect and remove exclusion volumes that are not critical for defining the binding pocket's shape, particularly in wider, solvent-accessible areas.

- Tune with Known Actives: Use the crystal structures of protein-ligand complexes to visually verify that your exclusion volumes do not clash with the bound conformation of known active compounds.

Q3: How can I validate the accuracy of my exclusion volume placement in the absence of a co-crystallized ligand?

Without a bound ligand, validation relies on computational and geometric checks.

- Use Binding Site Detection Tools: Employ computational tools like GRID or LUDI to independently predict the binding site location and its characteristics [2]. The predicted interaction fields should align spatially with your pharmacophore model and its excluded regions.

- Check for Steric Clashes: Use model validation software (e.g., MolProbity) to analyze the protein structure itself for steric clashes [15]. A well-structured binding site with good atomic packing reinforces confidence in the derived exclusion volumes [15].

- Comparative Analysis: If available, compare the exclusion volumes generated from your structure-based model with those inferred from a ligand-based pharmacophore model built from several known active compounds. Consensus between the two methods increases confidence.

Troubleshooting Guide: Exclusion Volume Optimization

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low hit rate in virtual screening | Overly restrictive exclusion volumes; Incorrect binding site definition. | Manually refine exclusion volumes; Use multiple binding site detection algorithms for consensus [2]. |

| High false positive rate | Insufficient or missing exclusion volumes; Poor protein structure preparation. | Add exclusion volumes to undefined cavity regions; Re-check and optimize the protein structure (add hydrogens, correct residues) [16]. |

| Model fails to discriminate actives from decoys | Poor pharmacophore model validation; Low-quality input protein structure. | Validate model with ROC curves and EF metrics [18]; Use a high-resolution protein structure (e.g., < 2.5 Å) [15]. |

| Unstable molecular dynamics (MD) results | Structural flaws in the initial protein-ligand complex; Energetically unfavorable poses. | Re-run docking with induced-fit flexibility; Ensure thorough energy minimization of the protein before model generation [16]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Workflows

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Pharmacophore Model Generation

This protocol details the creation of a structure-based pharmacophore model, highlighting critical steps for defining exclusion volumes.

1. Protein Preparation

- Source: Obtain the 3D structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Prefer a high-resolution structure (< 2.5 Å) co-crystallized with a potent ligand [15] [18].

- Preparation Steps:

- Add Hydrogen Atoms: Experimentally solved structures (e.g., by X-ray) lack hydrogen atoms. Use tools like PDB2PQR or the protein preparation wizard in suites like LigandScout to add them with correct protonation states at biological pH [16].

- Remove Redundant Moieties: Delete crystallographic water molecules and non-essential ions or co-factors, unless they are known to be crucial for ligand binding.

- Energy Minimization: Perform a brief energy minimization using a force field (e.g., within GROMACS) to relieve atomic clashes and optimize the structure's stereochemistry after modification [16].

2. Binding Site Analysis and Ligand Placement

- Identification: Define the binding site. If a co-crystallized ligand is present, use its location. Otherwise, use binding site prediction tools like GRID [2].

- Ligand Reference: The co-crystallized ligand in its bioactive conformation provides the spatial context for the essential interactions and, crucially, the steric boundaries of the cavity.

3. Pharmacophore Feature and Exclusion Volume Generation

- Feature Generation: Using software like LigandScout, interpret the protein-ligand interaction. The algorithm will map key pharmacophore features (e.g., Hydrogen Bond Donor/Acceptor, Hydrophobic regions) based on the interactions observed [17] [18].

- Exclusion Volume Placement: This is a critical step. The software automatically places exclusion volumes (represented as spheres) based on the van der Waals radii of protein atoms lining the binding pocket. These spheres define regions in 3D space where any atom from a screened compound would cause a steric clash, making the compound unlikely to bind.

4. Model Validation

- Decoy Set Screening: Validate the model's ability to distinguish active compounds from inactive ones (decoys). Use a dataset of known actives and decoys from a database like DUD-E [17] [18].

- Performance Metrics:

- ROC Curve & AUC: Generate a Receiver Operating Characteristic curve. A high Area Under the Curve (AUC), ideally above 0.7-0.8, indicates good discriminatory power.

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Calculate the EF at a specific threshold (e.g., 1%) to measure how much better the model is at identifying actives early in the screening list compared to random selection. An EF1% of 10, for example, means a 10-fold enrichment [18].

Protocol 2: Quantitative Validation of Pharmacophore Models

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for quantitatively assessing the performance of a generated pharmacophore model.

1. Dataset Curation

- Actives: Collect a set of 10-20 known active compounds against your target, with reported IC50 or Ki values, from databases like ChEMBL [17] [18].

- Decoys: Generate a larger set (e.g., 1000-5000) of chemically similar but presumed inactive molecules for the same target. The Database of Useful Decoys (DUD-E) is a standard resource for this purpose [17] [18].

2. Virtual Screening and Performance Calculation

- Screening: Use the pharmacophore model as a query to screen the combined set of actives and decoys.

- Analysis: Rank the compounds based on their fit value to the pharmacophore model.

- Calculation:

- ROC Curve: Plot the True Positive Rate against the False Positive Rate as the scoring threshold varies.

- AUC: Calculate the Area Under the ROC Curve. An AUC of 1.0 represents perfect separation, while 0.5 represents no discrimination.

- Enrichment Factor (EF): Calculate using the formula: EF = (Hitssampled / Nsampled) / (Hitstotal / Ntotal), where "Hits" are the number of known active compounds found in a sampled fraction of the ranked database.

The table below summarizes the key performance metrics and their interpretation for pharmacophore model validation.

| Metric | Formula/Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Area Under the Curve (AUC) | Area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) plot. | 1.0: Perfect model; 0.9-0.99: Excellent; 0.7-0.89: Good; ~0.5: No discrimination [17] [18]. |

| Enrichment Factor (EF1%) | (Number of actives found in top 1% of ranked database) / (Number of actives expected in a random 1% selection). | A value of 10-50 at 1% indicates a highly effective model for early enrichment [18]. |

| Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve | A probability curve plotting the True Positive Rate (TPR) against the False Positive Rate (FPR) at various thresholds. | A curve that arcs towards the top-left corner indicates better model performance [17]. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from protein preparation to the generation of a validated pharmacophore model, integrating the key troubleshooting and validation checkpoints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential software tools and databases used in structure-based pharmacophore modeling.

| Item Name | Function & Application | Relevance to Exclusion Volumes |

|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Advanced molecular design software for generating structure and ligand-based pharmacophore models [17] [18]. | Directly calculates exclusion volumes from the protein's van der Waals surface in the binding site; allows for manual editing and refinement. |

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary archive for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids [15] [2]. | Source of the initial protein structure. A high-resolution structure is critical for accurate exclusion volume placement. |

| Database of Useful Decoys (DUD-E) | Contains known active compounds and matched decoys for virtual screening validation [17] [18]. | Used to validate that exclusion volumes do not incorrectly filter out known active compounds while effectively discarding decoys. |

| GRID | A computational tool for determining energetically favorable binding sites on molecules of known structure [2]. | Helps independently define the binding cavity and its steric constraints, which can be cross-referenced with exclusion volumes. |

| GROMACS | A software package for molecular dynamics simulations and energy minimization [16]. | Used for protein structure optimization prior to pharmacophore modeling, ensuring a more realistic and stable structure for exclusion volume derivation. |

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why should I use co-crystallization over crystal soaking to generate structures for exclusion volume definition?

Co-crystallization is superior for capturing the correct bioactive pose, especially for larger, more flexible ligands that can trigger protein conformational changes. Soaking ligands into pre-formed crystals can result in misleading ligand orientations and inadequate positioning of protein amino-acid side and main chain atoms, which underestimates the true number of possible polar interactions. Soaking is more time and cost-effective and may be sufficient for fragment-sized ligands, but for lead optimization in drug design, co-crystallization should be the gold standard [19].

FAQ 2: What is the recommended ligand-to-protein ratio for a co-crystallization experiment?

For co-crystallization, the ligand and protein should be mixed before setting up the crystallization experiment. It is advisable to mix them several hours in advance or overnight to allow a complex to form (keep the protein on ice to prevent denaturation). The ligand-to-protein ratio should be at least 1:1 if equimolar binding is expected; however, better results are often achieved with a higher ligand-to-protein ratio, ranging from 2:1 for strong binders up to 50:1 or more in cases of weak affinity [20].

FAQ 3: How can excluded volume features improve my pharmacophore model?

A limitation of traditional pharmacophore models is that activity prediction is based purely on the presence and arrangement of pharmacophoric features, leaving steric effects unaccounted for. Adding excluded volumes to pharmacophore models penalizes molecules that occupy steric regions not occupied by active molecules. This accounts for steric effects on activity, resulting in a more selective model that reduces false positives and provides a better enrichment rate in virtual screening [6].

FAQ 4: Our crystal structures show a disordered glycine-rich loop. Is this a result of the crystallization method?

This is a known issue, particularly observed in soaked crystal structures of kinase-ligand complexes. Kinases are highly flexible proteins, and the glycine-rich loop (Gly-loop) covering the active site can adopt multiple conformations. Soaking experiments have been reported to result in partially disordered Gly-loops, whereas co-crystallization may better capture a specific, well-ordered conformation induced by ligand binding [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Inadequate Induced-Fit Adaptations in Protein Structure

- Symptoms: The protein structure in your complex does not show the expected conformational changes upon ligand binding, or the ligand's binding pose seems strained and does not maximize polar interactions.

- Potential Cause: Using the crystal soaking method for a large or flexible ligand. Soaking ligands into pre-formed crystals can restrict the protein's ability to undergo the necessary conformational changes (induced fit) for optimal binding [19].

- Solution:

- Switch to Co-crystallization: Co-crystallization allows the protein and ligand to form a complex in solution before crystallization, enabling the protein to adapt its structure to the ligand without the constraints of a pre-formed crystal lattice [19] [20].

- Confirm with Biochemical Data: Cross-validate the crystallographic data with biochemical activity assays. If the binding mode from the crystal structure does not explain the compound's potency, it may be incorrect [19].

Problem 2: Poorly Defined Electron Density for the Ligand

- Symptoms: The electron density map for the bound ligand is weak, broken, or unclear, making it difficult to model the correct binding pose and define exclusion volumes.

- Potential Causes:

- Low ligand occupancy or affinity.

- Inadequate soaking time or ligand concentration.

- Partial disorder in the protein-ligand complex.

- Solutions:

- For Soaking: Increase the ligand concentration and extend the soaking time to allow for full population of the binding site. Note that diffusion into crystals can sometimes take hours or days [19].

- For Co-crystallization: Ensure a sufficiently high ligand-to-protein ratio during complex formation [20].

- General: Consider if the ligand has multiple possible binding orientations and model alternate conformations if supported by the electron density.

Problem 3: Generating a High Number of False Positives in Virtual Screening

- Symptoms: Your pharmacophore-based virtual screen returns many compounds that fit the feature model but are later found to be inactive.

- Potential Cause: The pharmacophore model lacks excluded volumes, allowing generated or screened molecules to occupy sterically forbidden regions of the binding site [6].

- Solution:

- Define Exclusion Volumes: Use the 3D structure of your protein-ligand complex to define excluded volumes. These are regions in space where atoms from a potential ligand are not allowed due to steric clashes with the protein.

- Use Automated Algorithms: Employ computational tools like the HypoGenRefine algorithm in Catalyst, which can automatically add excluded volume features to pharmacophores based on the structural data of active molecules [6].

Experimental Data & Protocols

Table 1: Structural Comparison of Soaking vs. Co-crystallization for Selected PKA Ligands [19]

| Ligand | RMSD (Soaked vs. Co-crystal Ligand) | Key Protein Conformation Difference | Impact on Interaction Inventory |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fasudil (1) | 1.0 Å | Gly-rich loop ~2 Å more open in co-crystal | Co-crystal shows more polar interactions (with Asp184, Glu170) |

| Ligand 5 | Significant spatial shift | Gly-rich loop shifted down in co-crystal; forms H-bond with Thr51 | Altered ligand position and sulfonamide rotamer in soaked structure |

Protocol 1: Standard Co-crystallization Experiment for Protein-Ligand Complexes [20]

- Prepare Protein-Ligand Mixture: Mix the purified protein with your ligand in solution. Use a ligand-to-protein ratio of at least 1:1, but preferably higher (e.g., 2:1 to 50:1) for weak binders.

- Incubate: Allow the mixture to incubate for several hours or overnight on ice to facilitate complex formation.

- Set Up Crystallization: Use pre-established crystallization conditions for your protein. Set up crystallization drops with the protein-ligand mixture.

- Monitor and Harvest: Monitor the drops for crystal growth. Once crystals of suitable size are obtained, harvest them for X-ray diffraction data collection.

Protocol 2: Deriving Exclusion Volumes from a Co-crystal Structure

- Obtain the Structure: Solve the high-resolution X-ray crystal structure of your protein in complex with a co-crystallized ligand.

- Analyze the Binding Site: Identify the van der Waals surfaces of all protein atoms lining the binding pocket.

- Define Volumes: Using molecular modeling software (e.g., MOE, Schrödinger Suite, Catalyst), generate excluded volume spheres or grids that encapsulate the space occupied by the protein atoms. These volumes represent regions where ligand atoms are sterically forbidden.

- Integrate into Pharmacophore: Add these excluded volumes as constraints to your structure-based pharmacophore model.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Co-crystallization Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Target Protein | The macromolecule for crystallization. | Requires high purity, monodispersity, and structural integrity. |

| High-Purity Ligand | The small molecule to be co-crystallized. | Should be soluble in a compatible buffer. Stock solutions in DMSO are common. |

| Crystallization Screen Kits | A matrix of chemical conditions to identify initial crystallization parameters. | Commercial screens (e.g., from Hampton Research, Molecular Dimensions) are standard. |

| Cryoprotectant | Prevents ice crystal formation during flash-cooling for data collection. | Examples: glycerol, ethylene glycol, various cryos. Must be compatible with crystal lattice. |

Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the strategic decision-making process and workflow for using co-crystallized structures to define exclusion volumes in pharmacophore models.

Workflow for Leveraging Co-crystallized Structures in Pharmacophore Modeling

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary advantage of using a structure-based approach for pharmacophore modeling from an apo structure?

A1: The structure-based approach uses the three-dimensional structure of a macromolecular target, even in its ligand-free (apo) form, to derive a pharmacophore model. This method directly analyzes the protein's binding cavity to identify key interaction points, such as hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic areas, and ionizable groups, which are essential for ligand binding [2]. The primary advantage is that it does not require knowledge of existing active ligands, making it invaluable for novel targets. The resulting model incorporates spatial constraints from the binding site shape through the use of exclusion volumes, which represent forbidden areas for ligand atoms [2].

Q2: My apo protein structure is from AlphaFold. Are the cavities it detects reliable for pharmacophore modeling?

A2: AlphaFold has dramatically expanded structural coverage; however, cavity predictions from its models require careful validation [21]. A key metric is the pLDDT score, which measures local confidence on a scale of 0-100. Focus on cavities where a high ratio of residues have a pLDDT > 90 [21]. Studies show that only about 22.8% of cavities from experimental structures are perfectly reproduced in AlphaFold models, often due to differences in protein conformation, domain positioning, and flexible loops [21]. It is recommended to use the confidence metrics provided by AlphaFold and prioritize cavities located in high-confidence regions for pharmacophore generation [21].

Q3: How does the handling of apo structures differ from holo structures in binding site detection and pharmacophore generation?

A3: The core difference lies in the available information.

- Holo Structures (with ligand): The bound ligand directly informs the critical interactions and the precise spatial location of the binding site. Features can be generated based on the protein-ligand contacts, resulting in a highly accurate and specific pharmacophore model [2].

- Apo Structures (without ligand): The binding site must first be identified computationally using cavity detection tools like GRID, LUDI, or fpocket [2]. The pharmacophore model is then built by predicting all possible interaction points within the cavity. This often generates an excess of features, which must be carefully refined by selecting only those essential for bioactivity, for example, by identifying conserved residues or those with key functional roles [2].

Q4: What are exclusion volumes, and why are they critical for structure-based pharmacophore models derived from apo structures?

A4: Exclusion volumes (XVOL) are spatial constraints in a pharmacophore model that represent regions forbidden to ligand atoms, typically corresponding to the physical space occupied by the protein's binding site wallscitation:2. In apo structure-based modeling, where a bound ligand is not present to define the exact steric boundaries, exclusion volumes are crucial for defining the shape and size of the cavity. They prevent the selection of compounds that are sterically incompatible with the binding site, thereby improving the selectivity and accuracy of virtual screeningcitation:2.

Q5: What are some common challenges when predicting binding sites in apo structures, and how can I mitigate them?

A5: Common challenges and their mitigations are summarized below.

Table: Troubleshooting Binding Site Prediction in Apo Structures

| Challenge | Description | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Flexibility | Apo structures often represent a single conformation, missing alternative states or induced fit upon ligand binding [22]. | Use molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to generate an ensemble of structures. Consider using multiple cavity detection methods consensus [22]. |

| Oligomeric State | The biological, active form of the protein (e.g., a dimer) may differ from the crystallized unit, affecting cavity shape [22]. | Always use the biological assembly from the PDB for analysis. Check biochemical data to confirm the relevant oligomeric state [22]. |

| Redundant Predictions | Some methods may predict multiple, overlapping cavities for the same site, complicating analysis [23]. | Employ a re-scoring or clustering step. Tools like PRANK and DeepPocket can re-rank pockets to consolidate predictions [23]. |

| Method Selection | Over 50 prediction methods exist, using geometric, energy-based, or machine learning approaches, with varying performance [23]. | Consult independent benchmarks. Methods like DeepPocket, P2Rank, and re-scored fpocket (e.g., with PRANK) have shown high recall [23]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for Cavity Detection and Pharmacophore Generation from an Apo Structure

This protocol details the steps for identifying potential binding sites and converting them into a structure-based pharmacophore model.

1. Protein Preparation

- Obtain the apo protein structure from the PDB or a prediction database like AlphaFold.

- Critical Step: Prepare the structure using a tool like the Protein Preparation Wizard (Schrödinger) or BIOVIA Discovery Studio. This involves:

2. Binding Site Detection

- If the binding site location is unknown, use a cavity detection program.

- Using GRID: The GRID method uses different chemical probes (e.g., water, methyl group, carbonyl oxygen) to sample the protein surface on a regular grid. It identifies areas with energetically favorable interactions, generating a molecular interaction field that highlights potential binding sites [2].

- Alternative Tools: Other commonly used tools include fpocket (geometry-based and fast), P2Rank (machine learning-based), or SiteMap [23] [2].

3. Pharmacophore Feature Generation

- Within the identified binding cavity, use a structure-based pharmacophore tool (e.g., in MOE or Discovery Studio) to map potential interaction features.

- The software will analyze the amino acid residues and their properties to place pharmacophore features such as:

- Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD)

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA)

- Hydrophobic (H)

- Positively/Negatively Ionizable (PI/NI)

- Aromatic (AR)citation:2.

4. Feature Selection and Exclusion Volume Placement

- The initial feature map will likely contain too many features. Select the most relevant ones based on:

- Energetic contribution: Remove features that do not contribute significantly to binding energy.

- Conservation: If multiple structures are available, prioritize features from conserved residues.

- Spatial arrangement: Choose features that form a chemically sensible pattern for ligand recognition [2].

- Critical Step for Apo Structures: Add exclusion volumes to represent the van der Waals surface of the protein atoms lining the binding pocket. This is essential for defining the cavity's shape and preventing false positives in virtual screening [2].

5. Model Validation

- Validate your pharmacophore model by testing its ability to retrieve known active ligands from a decoy set (virtual screening validation). If no known actives exist, the model's performance can be assessed retrospectively once new actives are discovered.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of this protocol:

Protocol 2: Advanced Dynamic Workflow Incorporating MD Simulations

For a more robust model that accounts for protein flexibility, follow this advanced protocol.

1. Protein Preparation & Solvation

- Perform steps as in Protocol 1.

- Solvate the protein in a water box and add ions to neutralize the system, creating a simulation-ready environment.

2. Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation

- Run an MD simulation (e.g., using GROMACS, AMBER, or NAMD) for tens to hundreds of nanoseconds.

- The goal is to generate an ensemble of protein conformations, capturing the natural flexibility of the apo binding site [24].

3. Ensemble Cavity Detection & Pharmacophore Generation

- Extract multiple snapshots from the MD trajectory at regular intervals.

- Perform binding site detection and pharmacophore generation on each snapshot as described in Protocol 1 [24].

4. Generation of a Dynamic Pharmacophore Model

- Analyze the ensemble of pharmacophore models to identify:

- Conserved features: Features that are present in a high percentage of snapshots are considered essential for binding.

- Transient features: Features that appear and disappear, representing alternative interaction possibilities.

- Integrate the conserved features into a single, dynamic pharmacophore model. This model may contain alternative spatial arrangements or be a consensus of the most stable features [24].

The workflow for this advanced protocol is more complex, involving a cycle to capture flexibility:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Software

This table lists essential computational tools and their primary function in the analysis of binding site cavities.

Table: Essential Resources for Cavity Analysis and Pharmacophore Modeling

| Category | Tool Name | Primary Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Binding Site Detection | GRID | Energy-based method; uses chemical probes to find energetically favorable binding regions on the protein surface [2]. |

| P2Rank | Machine learning-based; predicts ligandability of local surface regions with high recall [23]. | |

| fpocket | Geometry-based; fast, open-source tool for detecting protein pockets and channels [23]. | |

| DeepPocket | Deep learning-based; combines 3D convolutional neural networks with pocket segmentation [23]. | |

| Structure-Based Pharmacophore | LigandScout | Creates pharmacophore models from protein-ligand complexes or apo structures with exclusion volumes [25]. |

| MOE | Integrated suite with tools for structure preparation, site finding, and pharmacophore model development. | |

| Structure Preparation & Analysis | PDB | Primary repository for experimentally determined protein structures (holo and apo) [2]. |

| AlphaFold DB | Database of highly accurate predicted protein structures for targets without experimental data [21]. | |

| PROPKA | Software for predicting pKa values of ionizable residues in proteins, critical for protonation state assignment [22]. | |

| Molecular Simulation | GROMACS/AMBER | Software suites for running MD simulations to study protein flexibility and generate structural ensembles [24]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Exclusion Volume Placement

Q1: My pharmacophore model is too restrictive and retrieves very few hits during virtual screening. How can I optimize the exclusion volumes?

A: Overly restrictive exclusion volumes (XVOLs) are a common cause of low hit retrieval. This can be addressed by:

- Adjusting XVOL Size and Quantity: Start with a larger number of XVOLs and iteratively refine the model by removing spheres that are not critical for defining the binding pocket or that cause the rejection of known active compounds. The optimal number is target-dependent; for example, a published 17β-HSD2 inhibitor model successfully employed over 50 XVOLs [26].

- Validating with a Test Set: Use a test set of known active and inactive compounds to validate your model. If the model incorrectly rejects active compounds, examine which exclusion volumes are responsible and adjust their radii or remove them [26].

- Ligand-Based Refinement: If structural data is unavailable, use ligand-based models. Generate a model from multiple active ligands and use the excluded volumes to define the common steric boundaries, ensuring they do not overlap with the space occupied by any active molecule [27].

Q2: The virtual screening hits align well with the pharmacophoric features but have poor binding affinity, likely due to steric clashes. How can I improve the model's selectivity?

A: Poor affinity in well-aligned hits often indicates insufficiently defined steric constraints.

- Incorporate Protein Structure Data: If a co-crystal structure is available, use a structure-based approach to place exclusion volumes. These should be generated from the protein atoms lining the binding pocket to accurately represent steric hindrance [27].

- Use Multiple Complex Structures: For a more robust definition, create pharmacophore models from several protein-ligand complexes and merge them. This helps in defining a consensus exclusion volume map that captures the essential steric constraints of the binding pocket across different ligand scaffolds [28].

- Analyze Inactive Compounds: Incorporate information from inactive compounds. If a compound is known to be inactive due to steric clash, ensure your exclusion volume model accounts for this specific steric violation [27].

Q3: My pharmacophore alignment algorithm prioritizes low RMSD over matching the maximum number of features, leading to suboptimal results. How can I force the algorithm to maximize feature matches?

A: This is a known limitation of some alignment algorithms that purely minimize Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD). Newer algorithms, like the Greedy 3-Point Search (G3PS), are specifically designed to maximize the number of matching feature pairs, even if this results in a slightly higher RMSD [29]. When possible: