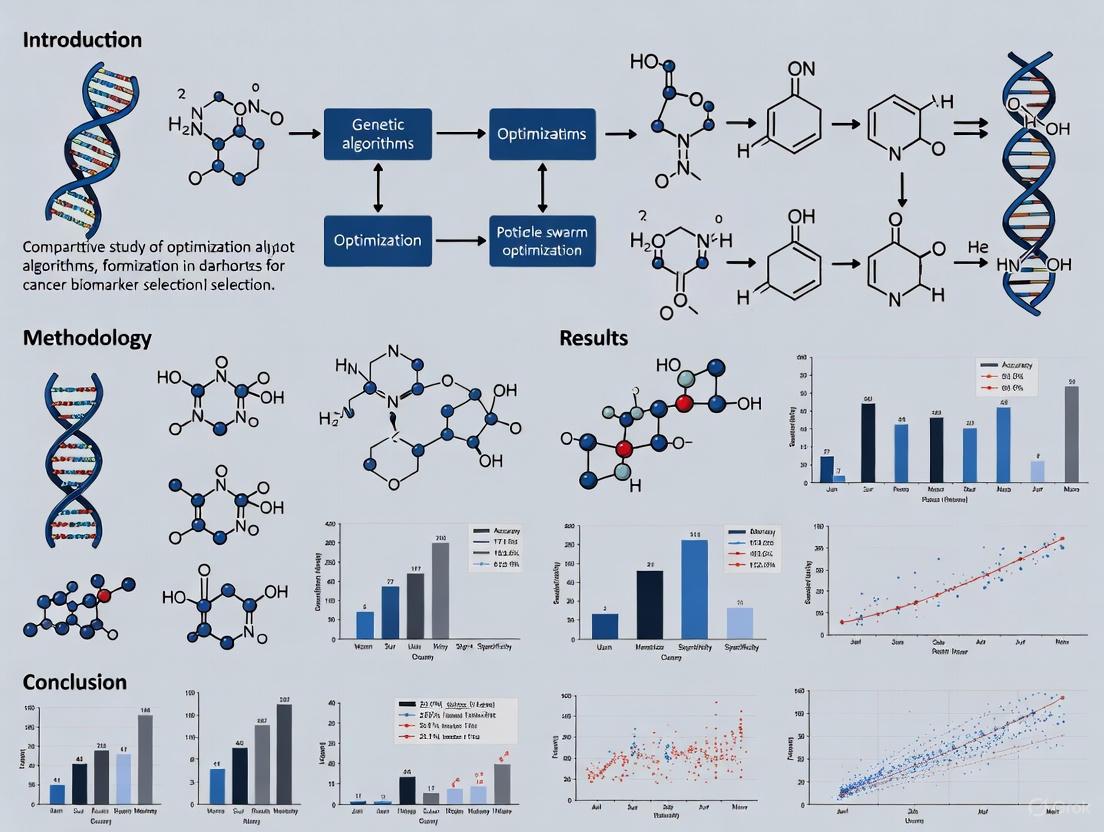

Optimization Algorithms for Cancer Biomarker Selection: A Comparative Review of AI and Machine Learning Methods

The selection of optimal biomarkers from high-dimensional biological data is a critical challenge in developing precise cancer diagnostics and therapies.

Optimization Algorithms for Cancer Biomarker Selection: A Comparative Review of AI and Machine Learning Methods

Abstract

The selection of optimal biomarkers from high-dimensional biological data is a critical challenge in developing precise cancer diagnostics and therapies. This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of optimization algorithms for cancer biomarker selection, catering to researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. We explore the foundational principles driving the need for advanced feature selection in oncology, detail methodological implementations from novel hybrid frameworks to multi-objective optimization systems, address key troubleshooting and optimization challenges in clinical translation, and present rigorous validation paradigms for comparative performance assessment. By synthesizing insights from cutting-edge research, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting and implementing optimization algorithms that enhance biomarker discovery for improved early cancer detection and personalized treatment strategies.

The Critical Need for Optimization in Cancer Biomarker Discovery

In oncology genomics, the n≪P problem—where the number of features (P, genes) vastly exceeds the number of samples (n, patients)—presents a significant challenge for biomarker discovery and classification. This comparison guide evaluates the performance of contemporary optimization algorithms designed to navigate this high-dimensional landscape, providing objective data and methodologies for researchers and drug development professionals.

The High-Dimensional Challenge in Cancer Genomics

Microarray and next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies generate datasets characterized by thousands of genes profiled from a relatively small number of patient samples [1] [2]. This high-dimensionality creates computational hurdles where traditional statistical methods often fail due to the curse of dimensionality, increased risk of overfitting, and the presence of numerous irrelevant or redundant features that can negatively impact model accuracy and increase computational load [1] [3].

The core challenge lies in efficiently identifying a small subset of globally informative genes that are statistically correlated with specific groups of Messenger Ribonucleic Acid (mRNA) tissue samples to enable meaningful biological interpretation and timely therapeutic interventions [1]. This necessitates sophisticated optimization algorithms capable of handling high-dimensional data to accurately select the most relevant gene subsets for diagnostic classification of medical responses [1].

Comparative Performance of Optimization Algorithms

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Cancer Gene Selection Algorithms

| Algorithm | Core Methodology | Dataset(s) | Key Performance Metrics | Genes Selected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOA-SVM [3] | Hybrid Armadillo Optimization Algorithm with SVM classifier | Ovarian | Accuracy: 99.12%, AUC-ROC: 98.83% | 15 |

| Leukaemia (AML, ALL) | Accuracy: 100%, AUC-ROC: 100% | 34 | ||

| CNS | Accuracy: 100% | 43 | ||

| AIMACGD-SFST [4] | Coati Optimization Algorithm (COA) with ensemble classification (DBN, TCN, VSAE) | Multi-dataset evaluation | Accuracy: 97.06%, 99.07%, 98.55% across 3 datasets | Not Specified |

| MOO Hybrid [1] | Hybrid filter-wrapper with t-test/F-test and Multi-Objective Optimization | Simulated + Public Microarray | Maximized classification accuracy with minimal gene subset | Varies by dataset |

| BCOOT Variants [4] | Binary COOT optimizer with hyperbolic tangent transfer function & crossover operator | Multiple Cancer Types | Effective cancer and disease gene identification | Not Specified |

Table 2: Methodological Comparison of Feature Selection Approaches

| Algorithm | Feature Selection Strategy | Classification Method | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| AOA-SVM [3] | Local optimization with subgroup shuffling for diversity | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Identifies minimal, biologically relevant gene markers; computationally efficient |

| AIMACGD-SFST [4] | Coati Optimization Algorithm (COA) | Ensemble (DBN, TCN, VSAE) | Reduces dimensionality while preserving critical data; improves model generalization |

| MOO Hybrid [1] | Sequential filter (t-test/F-test) + wrapper with MOO | Various classifiers | Clear, systematic procedure; achieves both accuracy maximization and gene minimization |

| BCOOT Variants [4] | Binary transformation with crossover operator | Not Specified | Novel application to gene selection; enhanced global search capabilities |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

The Armadillo Optimization Algorithm (AOA) with Support Vector Machine (SVM) classification implements a dual-phase strategy to address high-dimensional cancer data:

- Gene Selection Refinement: AOA performs efficient local optimization within smaller subgroups of features, followed by a shuffling phase to preserve solution diversity.

- Key Gene Identification: This dual-phase approach identifies genes that optimally distinguish between cancerous and healthy tissues.

- Classification: Selected gene subsets are classified using SVM to achieve high classification accuracy.

- Validation: The approach was evaluated on three major cancer datasets: leukaemia (AML, ALL), ovarian, and CNS cancers.

This method demonstrates that effective feature selection is crucial for improving classification performance in high-dimensional cancer datasets containing numerous irrelevant or redundant features [3].

This procedure optimizes gene selection by uniquely hybridizing filter and wrapper methods into a single, unambiguous sequential algorithm:

- Initial Filtering Stage: Noisy genes are eliminated from microarray data using the t-test for binary response groups and the F-test for multiclass response groups.

- Optimization Stage: The gene subset passing initial filtering undergoes further refinement using a wrapper method combined with Multi-Objective Optimization (MOO) technique.

- Performance Evaluation: The optimized gene subset is evaluated using out-of-bag (OOB) estimates across various performance indices, including accuracy.

The key distinction of this method is its multi-objective goal of simultaneously enhancing classification accuracy while minimizing the gene subset, whereas similar strategies often focus solely on improving accuracy [1].

Visualization of Algorithmic Workflows

Diagram 1: MOO Hybrid Gene Selection Workflow

Diagram 2: AOA-SVM Classification Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Genomic Biomarker Discovery

| Tool/Category | Function | Application in Cancer Genomics |

|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) [2] | High-throughput DNA/RNA sequencing | Facilitates identification of somatic mutations, structural variations, and gene fusions in tumors |

| AI/ML Platforms [5] [6] | Machine learning and deep learning algorithms | Analyzes high-dimensional genomic data to uncover biomarker patterns traditional methods miss |

| Cloud Computing Platforms [2] | Scalable data storage and processing | Handles massive genomic datasets (often terabytes per project) enabling global collaboration |

| Multi-Omics Integration [2] [6] | Combines genomics with transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics | Provides comprehensive view of biological systems beyond genomics alone |

| Biologically-Informed Neural Networks (BINNs) [7] | Embeds biological knowledge into model architecture | Improves genomic prediction accuracy and reveals nonlinear biological relationships |

Key Insights for Research Applications

The comparative analysis reveals that hybrid optimization approaches consistently outperform single-method strategies for high-dimensional genomic data. The AOA-SVM method stands out for its perfect classification results on leukemia data while maintaining high performance with minimal gene markers across other cancer types [3]. Similarly, ensemble methods like AIMACGD-SFST demonstrate superior accuracy through complementary model strengths [4].

Methodological transparency is crucial—algorithms with clear, systematic procedures for gene selection enable more meaningful biological interpretation and facilitate replication studies [1]. The field is evolving beyond genomics-only approaches, with multi-omics integration and biologically-informed models showing promise for capturing cancer complexity [2] [7].

When selecting optimization algorithms for biomarker discovery, researchers should prioritize methods that balance computational efficiency with biological interpretability, provide robust performance across multiple cancer types, and generate minimal gene subsets without sacrificing classification accuracy.

In clinical diagnostics, particularly for diseases with low prevalence such as cancer, the effective classification of patients into healthy control and disease groups represents a critical challenge [8]. While numerous metrics have been developed to evaluate classification performance, sensitivity (true-positive rate) and specificity (true-negative rate) stand as particularly important metrics in early cancer detection [8]. Sensitivity measures a model's ability to correctly identify positive cases, while specificity reflects its capacity to correctly classify negative cases. In early cancer detection and risk assessment applications, these metrics take on heightened significance: high sensitivity is essential to minimize missed cancer diagnoses, while high specificity helps avoid unnecessary clinical procedures in healthy individuals that can lead to physical, psychological, and financial burdens [8].

Traditional classification methods, such as logistic regression with maximum likelihood estimation, are designed to optimize overall accuracy and do not explicitly prioritize sensitivity—an essential objective in early cancer detection [8]. This limitation becomes particularly problematic in cancer screening, where the clinical costs of false negatives (missed cancers) and false positives (unnecessary procedures) are profoundly different. As research advances, novel computational approaches are emerging that directly address this sensitivity-specificity tradeoff, offering more clinically aligned optimization criteria for biomarker selection and model development in oncology.

Comparative Performance of Feature Selection Methodologies

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Feature Selection Methods on Colorectal Cancer Biomarker Data

| Method | Sensitivity at 98.5% Specificity | Statistical Significance (p-value) | Number of Selected Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMAGS-LASSO | 21.8% improvement over LASSO | 2.24E-04 | Same as LASSO |

| SMAGS-LASSO | 38.5% improvement over Random Forest | 4.62E-08 | Same as Random Forest |

| Standard LASSO | Baseline | Reference | Same as SMAGS-LASSO |

| Random Forest | Baseline | Reference | Same as SMAGS-LASSO |

Table 2: Synthetic Dataset Performance at 99.9% Specificity

| Method | Sensitivity | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|

| SMAGS-LASSO | 1.00 | 0.98–1.00 |

| Standard LASSO | 0.19 | 0.13–0.23 |

Table 3: miRNA Biomarker Identification Using Boruta Feature Selection

| Validation Dataset | AUC Performance | Feature Selection Method | Classifier |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Dataset (GSE106817) | 100% | Boruta | Random Forest/XGBoost |

| External Dataset 1 (GSE113486) | >95% | Boruta | Random Forest/XGBoost |

| External Dataset 2 (GSE113740) | >95% | Boruta | Random Forest/XGBoost |

Analysis of Comparative Results

The experimental data demonstrates significant advantages for methods specifically designed to optimize the sensitivity-specificity balance. SMAGS-LASSO shows remarkable performance improvements in both synthetic and real-world colorectal cancer biomarker data [8]. The synthetic dataset results are particularly revealing, with SMAGS-LASSO achieving perfect sensitivity (1.00) compared to dramatically lower sensitivity (0.19) for standard LASSO at the same high specificity threshold of 99.9% [8]. This performance differential highlights the critical importance of algorithm selection for clinical applications where false negatives must be minimized.

Similarly, the miRNA biomarker identification research utilizing the Boruta feature selection method demonstrates exceptional classification performance, achieving 100% AUC on internal validation and maintaining over 95% AUC on external datasets [9]. This consistency across validation sets confirms that robust feature selection combined with appropriate classification algorithms can yield highly reliable biomarkers for cancer detection.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

SMAGS-LASSO Framework

The SMAGS-LASSO method represents a novel approach that combines Sensitivity Maximization at a Given Specificity (SMAGS) framework with L1 regularization for feature selection [8]. This method employs a custom loss function with L1 regularization and multiple parallel optimization techniques to simultaneously optimize sensitivity at user-defined specificity thresholds while performing feature selection.

Objective Function: The SMAGS-LASSO objective function differs from traditional LASSO by directly optimizing sensitivity rather than likelihood or mean squared error [8]:

Where the first part is the proportion of true positive predictions among all positive cases, λ is the regularization parameter that controls sparsity, and SP is the given specificity threshold [8].

Optimization Procedure: The SMAGS-LASSO optimization employs a multi-pronged strategy using several algorithms [8]:

- Initialize coefficients using a standard logistic regression model

- Apply multiple optimization algorithms (Nelder-Mead, BFGS, CG, L-BFGS-B) with varying tolerance levels

- Select the model with the highest sensitivity among the converged solutions

Cross-Validation Framework: The method implements a specialized cross-validation procedure that [8]:

- Creates k-fold partitions of the data (k = 5 by default)

- Evaluates a sequence of λ values on each fold

- Measures performance using sensitivity mean squared error (MSE) metric

- Tracks the norm ratio to quantify sparsity

Boruta Feature Selection with Decision Tree Ensembles

The miRNA biomarker discovery research employed a comprehensive methodology for identifying colorectal cancer-associated miRNA signatures [9]:

Data Collection and Processing:

- Three publicly available microarray datasets (GSE106817, GSE113486, GSE113740) from GEO database

- Serum samples of cancer cases and non-cancer controls analyzed by microarray

- GSE106817 used for training (115 CRC patients + 2759 non-cancerous samples)

- External validation performed on GSE113486 and GSE113740

Feature Selection with Boruta:

- Boruta algorithm, a wrapper method built around random forest classification

- Creates shadow features (copies of original features with randomly shuffled values)

- Trains random forest classifier on extended dataset (original + shadow features)

- Compares significance scores of original features against highest shadow feature score

- Iterative process until stopping condition met, categorizing features as confirmed significant, confirmed nonsignificant, or tentative

Machine Learning Classification:

- Random Forest: Ensemble method using bagging and random feature selection

- XGBoost: Gradient boosting framework with regularization to prevent overfitting

- Objective function: (\mathcal{L}\left(\theta\right)=\sum{i=1}^{n}l\left({y}{i},{\stackrel{\prime}{y}}{i}\right)+\sum{k=1}^{K}{\Omega}\left({f}_{k}\right))

Multi-Objective Optimization for Gene Selection

The multi-objective optimization algorithm for gene selection employs a hybrid filter-wrapper approach [1]:

Stage 1: Filter Method

- Noisy genes eliminated using t-test for binary response groups

- F-test used for multiclass response groups

- Initial gene subset passing filtering proceeds to optimization stage

Stage 2: Wrapper Method with Multi-Objective Optimization

- Filtered gene subset subjected to further optimization

- Multi-objective optimization technique refines gene selection

- Performance evaluated using out-of-bag (OOB) estimates

- Objectives: Enhance classification accuracy while minimizing gene subset

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

SMAGS-LASSO Optimization Framework

Boruta Feature Selection Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Materials for Cancer Biomarker Studies

| Research Reagent | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| RNA-seq Gene Expression Data | Comprehensive profiling of gene expression for cancer classification | PANCAN dataset from TCGA with 801 samples across 5 cancer types [10] |

| Microarray miRNA Expression Data | Quantification of circulating miRNA expression levels | GEO datasets (GSE106817, GSE113486, GSE113740) for CRC miRNA discovery [9] |

| Protein Biomarker Data | Measurement of protein expression levels for cancer detection | Colorectal cancer protein biomarker panels [8] |

| Electronic Health Record Data | Longitudinal patient data for risk factor analysis | MIMIC-III dataset for cancer risk factor identification [11] |

| Histopathological Images | Digital pathology for cancer classification | BreakHis dataset for breast cancer diagnosis [12] |

| Synthetic Datasets | Controlled evaluation of algorithm performance | Simulated data with known sensitivity/specificity signals [8] |

The comparative analysis of feature selection methodologies reveals a critical evolution in cancer biomarker research: the shift from general optimization criteria toward clinically-informed objectives that explicitly balance sensitivity and specificity. Methods like SMAGS-LASSO demonstrate that substantial improvements in sensitivity at clinically relevant specificity thresholds are achievable through specialized algorithmic frameworks [8]. Similarly, wrapper-based feature selection methods like Boruta combined with ensemble classifiers can identify robust biomarker signatures with exceptional predictive performance [9].

The experimental protocols detailed herein provide researchers with validated methodologies for developing clinically viable biomarker panels. By incorporating sensitivity-specificity balance as a fundamental optimization criterion rather than a secondary consideration, these approaches promise to bridge the gap between statistical performance and clinical utility in cancer detection. As the field advances, the continued development of multi-objective optimization frameworks that explicitly address the clinical imperatives of early cancer detection will be essential for translating biomarker research into improved patient outcomes.

Evolution from Single-Marker to Multi-Modal Biomarker Signatures

The field of biomarker discovery has undergone a fundamental transformation, evolving from a reliance on single-marker approaches to the integration of multi-modal signatures that collectively provide a more comprehensive view of complex disease processes. This paradigm shift is particularly evident in oncology, where the limitations of individual biomarkers have become increasingly apparent in the face of disease heterogeneity and multifaceted therapeutic resistance mechanisms. Traditional single-marker approaches, while valuable for specific contexts, often fail to capture the complex biological interactions and temporal dynamics that characterize cancer progression and treatment response. The emergence of sophisticated computational methods and high-throughput technologies has enabled researchers to move beyond this reductionist approach toward integrated biomarker signatures that combine genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, imaging, and clinical data. This evolution represents a critical advancement in precision medicine, allowing for more accurate patient stratification, treatment selection, and therapeutic monitoring across diverse cancer types and biological contexts.

Comparative Performance of Biomarker Modalities

Diagnostic Accuracy Across Modality Classes

The relative performance of different biomarker modalities has been systematically evaluated in multiple cancer types, revealing significant advantages for multi-modal approaches. A comprehensive meta-analysis assessing biomarker modalities for predicting response to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy in tumor specimens from 8,135 patients across more than 10 solid tumor types demonstrated substantial variation in diagnostic accuracy between approaches [13].

Table 1: Diagnostic Accuracy of Biomarker Modalities for Predicting Immunotherapy Response

| Biomarker Modality | Area Under Curve (AUC) | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiplex IHC/IF (mIHC/IF) | 0.79 | - | - | 0.63 | - |

| Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) | 0.69 | - | - | - | - |

| PD-L1 IHC | 0.65 | - | - | - | - |

| Gene Expression Profiling (GEP) | 0.65 | - | - | - | - |

| Multi-modal Combination (PD-L1 IHC + TMB) | 0.74 | - | - | - | - |

This analysis revealed that multiplex immunohistochemistry/immunofluorescence (mIHC/IF) significantly outperformed single-modality approaches (P < 0.001 compared to PD-L1 IHC, P = 0.003 compared to GEP, and P = 0.049 compared to TMB), highlighting the advantage of spatial biomarker assessment that enables quantification of protein co-expression on immune cell subsets and evaluation of their spatial arrangements within the tumor microenvironment [13].

Multi-Modal Biomarker Applications Across Diseases

The superior performance of multi-modal biomarker approaches extends beyond oncology to neurodegenerative disorders, demonstrating the broad applicability of this methodology. In Alzheimer's disease, a transformer-based machine learning framework that integrated demographic information, medical history, neuropsychological assessments, genetic markers, and neuroimaging data achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) of 0.79 for predicting amyloid-beta (Aβ) status and 0.84 for predicting tau (τ) status across seven cohorts comprising 12,185 participants [14]. The inclusion of multiple data modalities significantly enhanced model performance, with Aβ prediction AUROC improving from 0.59 using only person-level history to 0.79 when all features were incorporated [14]. Similarly, tau prediction models demonstrated a comparable increase in AUROC from 0.53 to 0.84 with the inclusion of multi-modal data, with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data proving particularly impactful by increasing meta-τ AUROC from 0.53 to 0.74 [14].

In cardiovascular disease, a multimodal artificial intelligence/machine learning approach integrating transcriptomic expression data, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and clinical demographic information identified a signature of 27 transcriptomic features and SNPs that served as effective predictors of disease [15]. The best-performing model, an XGBoost classifier optimized via Bayesian hyperparameter tuning, correctly classified all patients in the test dataset, demonstrating the powerful predictive capability of integrated multi-omics approaches [15].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Hybrid Optimization Algorithms for Biomarker Selection

The identification of optimal biomarker combinations from high-dimensional data requires sophisticated computational approaches. A hybrid methodology combining particle swarm optimization (PSO) and genetic algorithms (GA) with artificial neural networks (ANN) has demonstrated particular efficacy for gene selection in cancer classification [16]. This approach addresses the critical challenge of analyzing gene expression data characterized by high dimensionality (often exceeding 10,000 genes) contrasted with small sample sizes (typically a few hundred samples) and high-noise nature [16].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Modal Biomarker Discovery

| Research Reagent | Application Context | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Microarray Technology | Gene Expression Profiling | Monitoring thousands of genes simultaneously in a single experiment |

| Artificial Neural Network (ANN) | Biomarker Classification | Information processing system for pattern recognition and classification |

| Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) | Feature Selection | Efficient search algorithm for identifying relevant biomarker combinations |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) | Feature Selection | Evolutionary optimization method for biomarker subset selection |

| RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) | Transcriptomic Analysis | Comprehensive gene expression profiling and alternative splicing detection |

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Genomic Variant Analysis | Identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms and structural variants |

| Multiplex Immunohistochemistry/Immunofluorescence (mIHC/IF) | Spatial Protein Analysis | Simultaneous visualization of multiple protein markers in tissue sections |

The experimental protocol implements a structured workflow: (1) data acquisition from gene expression profiles; (2) hybrid PSO-GA feature selection to identify informative gene subsets; (3) ANN classifier training with parameter optimization; and (4) validation using k-fold cross-validation and blinded samples [16]. The fitness of each gene subset (chromosome) is determined by the ANN classifier's accuracy, with the group of gene subsets exhibiting the highest 10-fold cross-validation classification accuracy selected as the optimal biomarker signature [16]. This methodology has been validated across multiple cancer types, including leukemia (ALL vs. AML classification), colon cancer, and breast cancer, consistently demonstrating the ability to identify small groups of biomarkers that improve classification accuracy while reducing data dimensionality [16].

Multi-Modal Data Integration Frameworks

The integration of diverse data modalities requires specialized computational frameworks that can accommodate heterogeneous data structures and missing data patterns. In Alzheimer's disease research, a transformer-based machine learning framework was specifically designed to integrate multimodal data while explicitly accommodating missing data, reflecting practical challenges inherent to real-world datasets [14]. This approach incorporated demographic information, medical history, neuropsychological assessments, genetic markers, and neuroimaging data in a flexible architecture that maintained robust performance even with significant missingness (54-72% fewer features in external validation sets) [14].

The framework implemented a multi-label prediction strategy that jointly predicted Aβ and τ accumulation to capture their interdependent roles in disease progression, addressing a key methodological gap in existing research that often considers pathological markers in isolation [14]. Model performance was rigorously evaluated through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and precision-recall (PR) curves, with additional validation against postmortem pathology to ensure biological relevance [14].

Visualization of Experimental Workflows and Biomarker Relationships

Hybrid Optimization Workflow for Biomarker Discovery

Hybrid Optimization for Biomarker Selection

Multi-Modal Data Integration Architecture

Multi-Modal Data Integration Workflow

Consensus Biomarker Evolution in Disease Progression

The temporal relationships between multi-modal biomarkers across disease progression have been systematically characterized through event-based modeling of multiple cohort studies. Research comparing ten independent Alzheimer's disease cohort datasets revealed a consensus sequence of biomarker evolution, starting with cerebrospinal fluid amyloid beta abnormalities, followed by tauopathy, memory impairment, FDG-PET metabolic changes, and ultimately brain deterioration and impairment of visual memory [17]. Despite variance in the positioning of mainly imaging variables across cohorts, the event-based models demonstrated similar and robust disease cascades (average pairwise Kendall's tau correlation coefficient of 0.69 ± 0.28), supporting the generalizability of the identified progression patterns [17].

This approach to modeling biomarker evolution highlights the complementary value of different data modalities while demonstrating that aggregation of data-driven results across multiple cohorts can generate a more complete picture of disease pathology compared to models relying on single cohorts [17]. The consistency observed across independent cohorts despite differences in specific inclusion criteria and measurement protocols underscores the robustness of multi-modal biomarker signatures for characterizing disease progression.

The evolution from single-marker to multi-modal biomarker signatures represents a fundamental advancement in biomarker discovery with profound implications for precision medicine. The comparative analysis presented herein demonstrates consistent superiority of integrated multi-modal approaches across diverse disease contexts, from oncology and neurodegenerative disorders to cardiovascular disease. The documented enhancement in diagnostic accuracy, prognostic capability, and predictive performance underscores the transformative potential of methodologies that capture the complex, multi-dimensional nature of disease pathophysiology.

Future developments in multi-modal biomarker research will likely focus on several key areas: standardization of data integration protocols across platforms and institutions; development of increasingly sophisticated computational methods capable of modeling complex interactions between biomarker modalities; validation of multi-modal signatures in diverse patient populations to ensure generalizability; and translation of these approaches into clinically actionable diagnostic tools. As these advancements mature, multi-modal biomarker signatures are poised to redefine diagnostic paradigms, therapeutic development, and personalized treatment strategies across the spectrum of human disease.

The identification of reliable cancer biomarkers from high-dimensional omics data represents a significant computational challenge in biomedical research. Microarray and RNA-sequencing technologies can simultaneously measure tens of thousands of molecular features, creating datasets where the number of features vastly exceeds the number of available patient samples [18] [19]. This "curse of dimensionality" can severely impact the performance of classification algorithms, leading to overfitting, increased computational complexity, and reduced model interpretability [18] [20]. Feature selection has emerged as an essential preprocessing step to address these challenges by identifying a minimal subset of biologically relevant features that enable accurate disease classification and prognosis [18] [21].

Within cancer biomarker discovery, feature selection methods are broadly categorized into four distinct paradigms: filter, wrapper, embedded, and hybrid methods. Each approach offers different trade-offs between computational efficiency, selection robustness, and biological interpretability. Filter methods operate independently of any classification algorithm, relying instead on statistical measures to evaluate feature relevance [22]. Wrapper methods utilize the performance of a specific classifier to assess the quality of selected feature subsets, typically yielding higher accuracy at greater computational cost [18]. Embedded methods integrate feature selection directly into the model training process, while hybrid methods strategically combine elements from different paradigms to leverage their respective strengths [18] [22]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these fundamental algorithm categories, supported by experimental data from recent cancer biomarker studies.

Algorithm Categories: Mechanisms and Workflows

Filter Methods: Statistical Feature Evaluation

Filter methods assess feature relevance based on intrinsic data properties using statistical measures, without involving any classification algorithm. These methods are computationally efficient and model-agnostic, making them suitable for initial feature reduction in high-dimensional datasets [22] [20]. Common statistical measures include mutual information, correlation coefficients, chi-squared tests, and relief-based algorithms [20].

A prominent application of filter methods in cancer research was demonstrated in a study identifying biomarkers for stomach adenocarcinoma (STAD). Researchers employed a two-step filter approach combining the limma package for differential expression analysis with Joint Mutual Information (JMI) to remove redundant features [19]. This approach successfully identified an 11-gene signature that effectively distinguished tumor from normal samples, achieving high classification accuracy in validation datasets [19]. The computational efficiency of filter methods makes them particularly valuable for initial processing of ultra-high-dimensional genomic data, where they can rapidly reduce feature space dimensionality before applying more refined selection techniques.

Wrapper Methods: Performance-Driven Feature Subset Selection

Wrapper methods evaluate feature subsets by leveraging classification algorithms themselves, using predictive performance as the direct selection criterion. These methods typically employ search algorithms to explore the feature space and identify subsets that optimize classifier accuracy [18] [23]. While computationally intensive, wrapper methods typically yield feature sets with superior predictive performance compared to filter methods, as they account for feature interactions and dependencies with respect to a specific classifier [20].

Recent advancements in wrapper methods include sophisticated optimization algorithms like Improved Binary Particle Swarm Optimization (IFBPSO), which incorporates a feature elimination strategy to progressively remove poor features during iterations [23]. Similarly, multi-objective genetic algorithms have been developed to optimize multiple criteria simultaneously, such as predictive accuracy, feature set size, and clinical applicability [21] [24]. These approaches address the overestimation bias common in wrapper methods by adjusting performance expectations during the optimization process, leading to more robust biomarker panels that generalize better to external validation datasets [24].

Embedded Methods: Integration with Classifier Training

Embedded methods incorporate feature selection directly into the classifier training process, combining the computational efficiency of filter methods with the performance-oriented approach of wrapper methods. These techniques leverage the internal parameters of learning algorithms to determine feature importance, typically through regularization techniques that penalize model complexity [8].

The SMAGS-LASSO framework represents a recent innovation in embedded methods, specifically designed for clinical cancer diagnostics where sensitivity at high specificity thresholds is paramount [8]. This approach integrates L1 regularization (LASSO) with a custom loss function that maximizes sensitivity while maintaining a user-defined specificity level. By directly incorporating clinical performance metrics into the feature selection process, SMAGS-LASSO identifies compact biomarker panels optimized for early cancer detection scenarios where minimizing false negatives is critical [8]. Other embedded approaches include decision tree-based methods that use information gain or Gini impurity for feature selection during model construction, and regularization methods like Elastic Net that combine L1 and L2 penalties [18].

Hybrid Methods: Strategic Combination of Approaches

Hybrid methods strategically combine filter and wrapper approaches to leverage their complementary strengths—the computational efficiency of filters and the performance accuracy of wrappers [18] [22] [20]. These methods typically employ a two-stage selection process: an initial filter stage rapidly reduces feature space dimensionality, followed by a wrapper stage that refines the selection using a classification algorithm [18] [20].

A novel hybrid framework developed for multi-label data introduces an interface layer using probabilistic models to mediate between filter and wrapper components [22]. This approach initializes feature rankings using filter methods, then employs multiple interactive probabilistic models (IPMs) to guide wrapper-based optimization through specialized mutation operators [22]. Similarly, a hybrid filter-differential evolution (DE) method applied to cancerous microarray datasets first selects top-ranked features using filter methods, then employs DE optimization to identify the most discriminative feature subsets [20]. This approach achieved perfect classification accuracy (100%) on Brain and Central Nervous System cancer datasets while reducing feature counts by approximately 50% compared to filter methods alone [20].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Comparison Across Cancer Types

Table 1: Performance comparison of feature selection methods across cancer types

| Cancer Type | Algorithm | Category | Accuracy (%) | Number of Features | Sensitivity/Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Cancer | Hybrid Filter-DE [20] | Hybrid | 100.0 | 121 | Not specified |

| CNS Cancer | Hybrid Filter-DE [20] | Hybrid | 100.0 | 156 | Not specified |

| Lung Cancer | Hybrid Filter-DE [20] | Hybrid | 98.0 | 296 | Not specified |

| Breast Cancer | Hybrid Filter-DE [20] | Hybrid | 93.0 | 615 | Not specified |

| Gastric Cancer | limma + JMI [19] | Filter | High* | 11 | Verified by ROC |

| Colorectal Cancer | SMAGS-LASSO [8] | Embedded | Not specified | Minimal | 21.8% improvement over LASSO |

| Synthetic Data | SMAGS-LASSO [8] | Embedded | Not specified | Not specified | Sensitivity: 1.00 vs 0.19 (LASSO) |

| Multiple Cancers | C-IFBPFE [23] | Wrapper | High | Minimal | Superior to state-of-the-art |

Note: Exact accuracy not specified in source; * Classification accuracy superior to current state-of-the-art methods

Computational Characteristics and Clinical Applicability

Table 2: Computational properties and clinical applicability of feature selection methods

| Algorithm Category | Computational Efficiency | Model Dependency | Risk of Overfitting | Key Clinical Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Filter Methods | High | Model-agnostic | Low | Rapid biomarker screening; Handles ultra-high dimensionality |

| Wrapper Methods | Low to Moderate | Classifier-dependent | Moderate to High | Superior predictive accuracy; Captures feature interactions |

| Embedded Methods | Moderate | Model-dependent | Low to Moderate | Balances performance with efficiency; Built-in regularization |

| Hybrid Methods | Varies by implementation | Combination | Moderate | Optimized trade-offs; Enhanced performance with reduced features |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Hybrid Filter-Wrapper Protocol for Microarray Data

A comprehensive hybrid methodology for cancer classification from microarray data was detailed in a 2024 study [20]. The experimental protocol encompassed the following stages:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Four cancerous microarray datasets (Breast, Lung, Central Nervous System, and Brain) were utilized. Initial preprocessing addressed missing values, normalized expression values, and prepared data for feature selection.

Initial Filter-based Feature Reduction: Six established filter methods (Information Gain, Information Gain Ratio, Correlation, Gini Index, Relief, and Chi-squared) independently scored and ranked all genes. The top 5% of ranked features from each method were retained, substantially reducing dimensionality while preserving potentially relevant biomarkers.

Wrapper-based Feature Optimization: A Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm operated on the reduced feature set from the filter stage. The DE employed a classifier-based fitness function to evaluate feature subsets, further optimizing the selection by identifying features with synergistic discriminative power.

Performance Validation: The final feature subsets were used to train multiple classifiers. Performance was evaluated via cross-validation and compared against results using features from filter methods alone, demonstrating the hybrid method's superior accuracy with fewer features [20].

SMAGS-LASSO Protocol for Sensitivity-Specificity Optimization

The SMAGS-LASSO framework introduced a specialized embedded protocol for clinical cancer biomarker detection, prioritizing sensitivity at high specificity thresholds [8]:

Problem Formulation: For binary classification with feature matrix ( X ) and outcome vector ( y ), the objective was to find a sparse coefficient vector ( \beta ) that maximizes sensitivity subject to a specificity constraint ( SP ).

Custom Objective Function: The method utilized a specialized loss function combining L1 regularization for sparsity with direct sensitivity optimization:

( \max{\beta,\beta0} \frac{\sum{i=1}^n \hat{yi} \cdot yi}{\sum{i=1}^n yi} - \lambda \|\beta\|1 )

Subject to ( \frac{(1-y)^T(1-\hat{y})}{(1-y)^T(1-y)} \geq SP )

where ( \hat{yi} = I(\sigma(xi^T\beta + \beta_0) > \theta) ), ( \sigma ) is the sigmoid function, and ( \theta ) is a threshold parameter adaptively controlled to maintain the specificity level.

Multi-Pronged Optimization: The non-differentiable objective function was optimized using multiple algorithms (Nelder-Mead, BFGS, CG, L-BFGS-B) in parallel with varying tolerance levels. The solution with highest sensitivity among converged results was selected.

Cross-Validation Framework: A specialized k-fold cross-validation selected the optimal regularization parameter ( \lambda ) by minimizing sensitivity mean squared error while tracking sparsity via a norm ratio metric.

This protocol demonstrated significant improvements in sensitivity over standard LASSO (1.00 vs 0.19 at 99.9% specificity) on synthetic data and a 21.8% sensitivity improvement on colorectal cancer protein biomarker data [8].

Table 3: Key computational tools and datasets for feature selection research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Datasets | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Public Genomic Databases | TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) [19] [21] | Provides standardized multi-omics cancer data for biomarker discovery |

| Normal Tissue Reference | GTEx (Genotype-Tissue Expression) [19] | Offers normal tissue expression baseline for differential expression analysis |

| Validation Data Sources | NCBI GEO DataSets [19] | Independent datasets for validating identified biomarker panels |

| Statistical Analysis Tools | limma R package [19] | Differential expression analysis for initial feature filtering |

| Information Theory Measures | Joint Mutual Information (JMI) [19] | Evaluates feature relevance while considering interdependencies |

| Optimization Algorithms | Differential Evolution [20], Improved Binary PSO [23] | Searches feature space for optimal subsets in wrapper methods |

| Multi-Objective Frameworks | NSGA-II [22], DOSA-MO [24] | Optimizes multiple criteria simultaneously (accuracy, size, cost) |

| Regularization Methods | SMAGS-LASSO [8] | Embeds feature selection with sensitivity-specificity optimization |

The comparative analysis of fundamental feature selection categories reveals a clear trade-off between computational efficiency and predictive performance. Filter methods provide rapid feature reduction for ultra-high-dimensional data, wrapper methods deliver superior accuracy at greater computational cost, embedded methods offer balanced performance with built-in regularization, and hybrid methods strategically combine these approaches for optimal results.

For cancer biomarker discovery, the choice of algorithm category depends heavily on research objectives, dataset characteristics, and clinical application requirements. High-throughput screening scenarios may benefit from initial filter-based reduction, while diagnostic applications requiring maximal sensitivity might employ specialized embedded methods like SMAGS-LASSO. Hybrid approaches have demonstrated remarkable effectiveness in achieving perfect classification with minimal features for certain cancer types, highlighting their value in developing clinically viable biomarker panels.

Future directions in feature selection research include enhanced multi-objective optimization considering clinical implementation costs, improved overestimation adjustment techniques for wrapper methods, and causal feature selection frameworks that better capture biological mechanisms underlying cancer progression. As genomic datasets continue growing in size and complexity, strategic algorithm selection will remain crucial for translating high-dimensional molecular measurements into clinically actionable cancer biomarkers.

The Impact of Biomarker Selection on Diagnostic Accuracy and Clinical Utility

The selection of specific biomarkers is a pivotal step in the development of cancer diagnostics, directly influencing the accuracy and clinical utility of the resulting tests [25]. In modern oncology, biomarkers—biological molecules such as proteins, genes, or metabolites—provide essential information for early detection, diagnosis, treatment selection, and therapeutic monitoring [25]. The transition from single-biomarker tests to multi-marker panels represents a significant evolution in diagnostic strategy, offering enhanced performance by capturing the complex heterogeneity of cancer [25] [26]. This progression is further accelerated by computational advances, including novel machine learning algorithms specifically designed to optimize biomarker selection based on clinically relevant performance metrics rather than mere statistical associations [8]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of biomarker selection strategies, their impact on diagnostic performance, and the experimental frameworks used in their evaluation, contextualized within a broader thesis on optimization algorithms for cancer biomarker research.

Biomarker Selection Strategies and Their Clinical Implications

Single vs. Multi-Marker Approaches

The choice between single biomarkers and multi-marker panels carries significant implications for diagnostic performance.

Single Biomarker Limitations: Traditional single biomarkers, such as Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) for prostate cancer or CA-125 for ovarian cancer, have demonstrated limitations in sensitivity and specificity [25]. These markers often exhibit elevation in benign conditions, leading to false positives, unnecessary invasive procedures, and patient anxiety [25]. Furthermore, they may not appear until the cancer is advanced, diminishing their value for early detection [25].

Multi-Marker Panel Advantages: The strategic combination of multiple biomarkers into a single test significantly improves diagnostic accuracy by capturing the biological complexity and heterogeneity of cancer [25] [26]. For example, in bladder cancer, a 10-protein biomarker panel demonstrated a substantial improvement in diagnostic capability. When measured using a multiplex bead-based immunoassay (MBA), the panel achieved an Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (AUROC) curve of 0.97, with 0.93 sensitivity and 0.95 specificity [26]. This represents a marked enhancement over what is typically achievable with a single biomarker.

Algorithm-Driven Selection for Performance Optimization

The integration of machine learning for biomarker selection represents a paradigm shift from traditional statistical methods. Novel algorithms are now being designed to optimize for specific clinical performance metrics from the outset.

SMAGS-LASSO for Sensitivity-Specificity Optimization The SMAGS-LASSO (Sensitivity Maximization at a Given Specificity with LASSO) framework was developed specifically to address a critical clinical need: maximizing sensitivity (true positive rate) at a predefined, high level of specificity (true negative rate) [8]. This is particularly crucial for cancer screening, where missing a true case (low sensitivity) can be fatal, and too many false alarms (low specificity) can lead to unnecessary, invasive follow-up procedures [8].

- Mechanism: SMAGS-LASSO incorporates a custom loss function that combines L1 regularization (for feature selection) with an optimization target that directly maximizes sensitivity while constraining specificity to a user-defined threshold (e.g., 98.5% or 99.9%) [8].

- Performance: In evaluations on colorectal cancer protein biomarker data, SMAGS-LASSO demonstrated a 21.8% improvement in sensitivity over standard LASSO and a 38.5% improvement over Random Forest at a high specificity of 98.5%, while selecting the same number of biomarkers [8]. This demonstrates that the choice of selection algorithm itself can yield significant performance gains with an identical biomarker starting set.

The table below summarizes the core differences between traditional and modern biomarker selection approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of Biomarker Selection Strategies

| Feature | Traditional Single-Marker Approach | Modern Multi-Marker Panel Approach | Algorithm-Optimized Selection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Analytes | Single biomarker | Multiple biomarkers (e.g., 10 proteins) | Multiple biomarkers, optimally selected |

| Typical Performance | Highly variable; often moderate sensitivity and/or specificity (e.g., PSA) [25] | Superior and more balanced performance (e.g., AUROC 0.97) [26] | Tailored for specific clinical goals (e.g., max sensitivity at fixed specificity) [8] |

| Key Challenge | Limited by biological complexity and heterogeneity | Identifying the optimal combination from many candidates | Integrating clinical utility directly into the computational selection process |

| Clinical Impact | Risk of overdiagnosis and false positives [25] | More accurate risk stratification and diagnosis [26] | Enables development of tests with pre-defined, clinically relevant error rates |

Experimental Methodologies for Biomarker Validation

The translation of biomarker candidates into clinically useful tests relies on robust experimental protocols to validate their performance.

Multiplex Immunoassay Technology

Multiplex arrays enable the simultaneous quantification of multiple proteins in a single assay, which is essential for validating and deploying multi-marker panels efficiently.

- Protocol Overview: In a comparative study of bladder cancer biomarkers, researchers quantified 10 target proteins (including IL-8, MMP-9, VEGF, and CA9) in urine samples using two prototype multiplex platforms: a Multiplex Bead-based Immunoassay (MBA) and a Multiplex Electrochemoluminescent Assay (MEA) [26]. These were compared against the gold standard of individual commercial Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) kits.

- Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Banked urine samples from 80 subjects (40 with bladder cancer, 40 controls) were processed.

- Assay Execution: Each sample was analyzed on the MBA and MEA platforms alongside the 10 individual ELISA kits.

- Data Analysis: The concentration of each biomarker was determined. Diagnostic accuracy was evaluated by calculating the AUROC, sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) for each platform [26].

- Results and Interpretation: The MBA platform demonstrated superior performance (AUROC: 0.97) compared to the MEA (AUROC: 0.86), validating the multi-marker panel and showing that the multiplex platform could match or even exceed the accuracy of more cumbersome, single-plex ELISAs [26]. This underscores that the detection technology itself is a critical variable in determining the final diagnostic utility of a selected biomarker panel.

Defining Clinical Utility Through Cut-Point Optimization

Selecting the optimal cut-off point for a positive test is as crucial as selecting the biomarkers themselves. Methods based on clinical utility are gaining traction over pure accuracy metrics.

- Protocol Overview: Cut-point selection can be guided by utility-based criteria that incorporate the consequences of clinical decisions, not just sensitivity and specificity [27]. Key metrics include Positive Clinical Utility (PCUT = Sensitivity × PPV) and Negative Clinical Utility (NCUT = Specificity × NPV) [27].

- Procedure:

- Define Utility Metrics: Calculate PCUT and NCUT across all potential cut-points, incorporating disease prevalence.

- Apply Selection Criteria: Several methods can be used to select the final cut-point:

- Maximize YBCUT: Maximizes the sum of PCUT and NCUT.

- Maximize PBCUT: Maximizes the product of PCUT and NCUT.

- Minimize UBCUT: Minimizes the absolute difference between PCUT and AUC plus the difference between NCUT and AUC [27].

- Results and Interpretation: The optimal cut-point can vary significantly depending on the chosen method, particularly at low disease prevalences and with tests of lower accuracy (e.g., AUC = 0.60) [27]. For high-accuracy tests (AUC = 0.90) and higher prevalence (>10%), different methods tend to converge on a similar cut-point, offering more robust guidance for clinical use [27].

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

Biomarker Selection & Clinical Translation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the multi-stage pipeline from biomarker discovery to clinical application, highlighting the critical role of selection and optimization.

Multiplex Assay Advantage

This diagram contrasts the workflows of single-plex versus multiplex assays, demonstrating the efficiency gains of the latter in validating biomarker panels.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting biomarker validation studies, as derived from the cited experimental protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Biomarker Validation

| Item | Function/Description | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|

| Multiplex Bead-Based Immunoassay (MBA) Kit | Allows simultaneous quantification of multiple protein biomarkers in a single sample well, maximizing throughput and conserving precious sample [26]. | Used to measure a 10-protein panel for bladder cancer diagnosis, achieving high accuracy (AUROC 0.97) [26]. |

| Matched Antibody Pairs | Pairs of antibodies that bind to distinct epitopes on the same target antigen; essential for constructing specific and sensitive sandwich immunoassays [28]. | Critical for the MBA and MEA platforms; the performance of the diagnostic panel is contingent on the quality and specificity of these antibody pairs [26]. |

| ELISA Kits | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay kits represent the traditional gold standard for quantitative protein measurement, often used as a benchmark for comparison [26] [28]. | Used as a reference method to validate the performance of the novel multiplex arrays in the bladder cancer study [26]. |

| Clinical-Grade Biological Samples | Well-characterized, banked patient samples (e.g., urine, plasma, serum) with confirmed diagnosis; the quality of this resource is fundamental for robust validation [26]. | The study utilized 80 banked urine samples with histologically confirmed bladder cancer status, which is essential for calculating true accuracy metrics [26]. |

| Optical Microplate Reader | Instrument to measure the optical density (color intensity) or luminescence signal from assay plates, enabling quantification of biomarker levels [28]. | Required for reading both traditional ELISA plates and the microplates used in multiplex electrochemoluminescent assays (MEA) [26] [28]. |

The selection of biomarkers is a deterministic factor in the diagnostic accuracy and ultimate clinical utility of cancer tests. The evolution from single biomarkers to algorithmically optimized multi-marker panels, validated by robust multiplex technologies, represents the forefront of diagnostic development. The integration of machine learning methods like SMAGS-LASSO, which are designed with clinical priorities at their core, enables the creation of tests with predictable and superior performance characteristics. As the field progresses, the synergy between computational selection, advanced assay technologies, and utility-driven statistical analysis will continue to refine the precision of cancer diagnostics, ultimately translating into improved patient outcomes through earlier detection and more tailored therapeutic interventions.

Algorithmic Approaches: From LASSO Variants to Nature-Inspired Optimization

In the field of cancer biomarker research, the selection of informative features from high-dimensional data represents a critical challenge with direct implications for diagnostic accuracy. Traditional machine learning algorithms often prioritize overall accuracy during optimization, which fails to align with clinical priorities in early cancer detection where maximizing sensitivity at high specificity thresholds is paramount [8]. This misalignment can lead to unacceptable rates of missed cancer diagnoses or unnecessary clinical procedures in healthy individuals [29].

Regularization methods have emerged as powerful tools for addressing these challenges by performing feature selection while controlling model complexity. Among these, LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) regression has gained prominence for its ability to induce sparsity by driving coefficients of uninformative features to zero [30]. However, standard LASSO optimizes for overall prediction error without directly addressing the clinical need for prioritized sensitivity-specificity tradeoffs. The recently developed SMAGS-LASSO framework addresses this limitation by integrating sensitivity-specificity optimization directly into the feature selection process [8].

This comparison guide examines SMAGS-LASSO alongside established regularization methods, providing researchers with experimental data, methodological insights, and practical implementation considerations for cancer biomarker selection.

Methodological Framework: How SMAGS-LASSO Works

Core Theoretical Foundation

SMAGS-LASSO represents a novel machine learning algorithm that combines the Sensitivity Maximization at a Given Specificity (SMAGS) framework with L1 regularization for feature selection [8]. This approach simultaneously optimizes sensitivity at user-defined specificity thresholds while performing feature selection, addressing a critical gap in clinical diagnostics for diseases with low prevalence such as cancer [31].

The method employs a custom loss function that combines sensitivity optimization with L1 regularization, dynamically adjusting the classification threshold based on a specified specificity percentile [8]. Formally, the SMAGS-LASSO objective function for a binary classification problem with feature matrix X ∈ R^n×p and outcome vector y ∈ {0, 1}^n can be represented as:

where the first term represents sensitivity (true positive rate), λ is the regularization parameter, ||β||1 is the L1-norm of the coefficient vector, and SP is the user-defined specificity constraint [8].

Optimization Approach

The SMAGS-LASSO optimization is challenging due to the non-differentiable nature of both the sensitivity metric and the L1 penalty. To address this, the method employs a multi-pronged optimization strategy using several algorithms in parallel [8]:

- Initialization with standard logistic regression coefficients

- Parallel application of multiple optimization algorithms (Nelder-Mead, BFGS, CG, L-BFGS-B) with varying tolerance levels

- Selection of the model with the highest sensitivity among converged solutions

This approach comprehensively explores the parameter space while leveraging parallel processing for computational efficiency [8].

specialized Cross-Validation

SMAGS-LASSO implements a specialized cross-validation procedure to select the optimal regularization parameter λ. This process [8]:

- Creates k-fold partitions of the data (typically k = 5)

- Evaluates a sequence of λ values on each fold

- Measures performance using a sensitivity mean squared error (MSE) metric

- Tracks the norm ratio ||βλ||1/||β||1 to quantify sparsity

The cross-validation selects the λ value that minimizes sensitivity MSE, effectively finding the most regularized model that maintains high sensitivity [8].

Table 1: Key Components of the SMAGS-LASSO Framework

| Component | Description | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Custom Loss Function | Combines sensitivity maximization with L1 penalty | Aligns feature selection with clinical priorities |

| Specificity Constraint (SP) | User-defined specificity threshold | Controls false positive rate based on clinical context |

| Parallel Optimization | Multiple algorithms with different convergence properties | Ensures robust parameter estimation |

| Sensitivity MSE Metric | Cross-validation performance measure | Maintains high sensitivity during regularization |

Figure 1: SMAGS-LASSO Method Workflow - The integrated framework combining specificity constraints with parallel optimization for biomarker selection

Comparative Performance Analysis

Synthetic Data Experiments

Rigorous evaluation of SMAGS-LASSO against established methods employed synthetic datasets specifically engineered to contain strong signals for both sensitivity and specificity [8]. Each dataset comprised 2,000 samples (1,000 per class) with 100 features, using an 80/20 train-test split with a high specificity target (SP = 99.9%) to simulate scenarios where false positives must be minimized [8].

In these controlled experiments, SMAGS-LASSO demonstrated remarkable performance advantages over standard LASSO. At 99.9% specificity, SMAGS-LASSO achieved a sensitivity of 1.00 (95% CI: 0.98-1.00) compared to just 0.19 (95% CI: 0.13-0.23) for standard LASSO [8]. This substantial improvement highlights SMAGS-LASSO's ability to leverage sensitivity-specificity tradeoffs during feature selection, a capability lacking in traditional regularization methods.

Colorectal Cancer Biomarker Application

In real-world protein biomarker data for colorectal cancer detection, SMAGS-LASSO maintained its performance advantages [8] [31]. When evaluated at 98.5% specificity, SMAGS-LASSO demonstrated:

- 21.8% improvement over standard LASSO (p-value = 2.24E-04)

- 38.5% improvement over Random Forest (p-value = 4.62E-08)

These performance gains were achieved while selecting the same number of biomarkers as comparison methods, confirming that improvements stem from optimized coefficient estimation rather than simply selecting different feature sets [8].

Comparison with Other Regularization Methods

While direct comparisons between SMAGS-LASSO and all existing regularization methods in cancer detection are limited in the current literature, broader context can be drawn from studies of regularization techniques in related biomedical applications.

Table 2: Performance Comparison Across Regularization Methods in Cancer Research

| Method | Application Context | Key Performance Metrics | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMAGS-LASSO | Colorectal cancer protein biomarkers | Sensitivity: 1.00 at 99.9% specificity (synthetic); 21.8% improvement over LASSO (real data) [8] | Direct sensitivity-specificity optimization; Sparse biomarker panels | Computational complexity; Emerging validation |

| Standard LASSO | Various cancer toxicity prediction [32] [33] | AUC: 0.754±0.069 for radiation esophagitis [32] | Computational efficiency; Feature selection | Generic optimization; Subclinical sensitivity |

| Elastic Net | Cancer classification [30] [34] | Combines L1 and L2 regularization [30] | Handles correlated features; Stabilizes selection | Two parameters to tune; Less sparse solutions |

| LogSum + L2 | Cancer classification from genomic data [34] | Competitive group feature selection [34] | Grouping effects; Enhanced selection | Computational complexity; Niche applicability |

| Bayesian LASSO | Radiation toxicity prediction [32] | Best average performance across toxicities [32] | Uncertainty quantification; Robust estimation | Computational intensity; Complex implementation |

A comprehensive study comparing 10 machine learning algorithms for predicting radiation-induced toxicity found that no single algorithm performed best across all datasets [32]. LASSO achieved the highest area under the precision-recall curve (0.807 ± 0.067) for radiation esophagitis, while Bayesian-LASSO showed the best average performance across different toxicities [32]. This context underscores that method performance is often dataset-dependent, though SMAGS-LASSO's specialized design addresses specific clinical priorities in early detection.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Evaluation Methodology

The experimental protocol for validating SMAGS-LASSO employed a comprehensive evaluation strategy comparing against established methods including standard LASSO, unregularized SMAGS, and Random Forest [8]. All experiments used 80/20 stratified train-test splits to maintain balanced class representation and ensure robust performance assessment [8].

Performance was evaluated using multiple metrics with emphasis on sensitivity at high specificity thresholds (98.5% and 99.9%) relevant to cancer screening contexts. The evaluation framework employed statistical significance testing with calculation of p-values and confidence intervals to quantify performance differences [8].

Implementation Considerations

For researchers implementing SMAGS-LASSO, several practical considerations emerge from the experimental protocols:

- Data Preprocessing: Like other regularization methods, feature scaling is recommended before applying SMAGS-LASSO to ensure stable optimization [30]

- Specificity Threshold Selection: The target specificity (SP) should be chosen based on clinical requirements for false positive rates in the intended application

- Parallel Computation: The multi-algorithm optimization approach benefits from parallel processing capabilities for reduced computation time

- Open Source Availability: An implementation is available at github.com/khoshfekr1994/SMAGS.LASSO [8]

Figure 2: SMAGS-LASSO Experimental Validation Framework - The standardized evaluation protocol using stratified data splits and specificity-constrained optimization

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methods

Successful implementation of SMAGS-LASSO and comparative analysis with other regularization methods requires specific research tools and computational resources. The following table details essential components for researchers working in this domain.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Regularization Method Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SMAGS-LASSO Software | Algorithm implementation | Available at github.com/khoshfekr1994/SMAGS.LASSO [8] |

| Optimization Libraries | Parallel algorithm execution | Nelder-Mead, BFGS, CG, L-BFGS-B algorithms [8] |

| Cross-Validation Framework | Regularization parameter selection | k-fold partitioning with sensitivity MSE metric [8] |

| Biomarker Datasets | Method validation | Synthetic and real-world protein biomarker data [8] |

| Statistical Testing Tools | Performance comparison | Calculation of p-values and confidence intervals [8] |

Discussion and Clinical Implications

The development of SMAGS-LASSO represents a significant advancement in clinically-aware feature selection for cancer detection. By directly incorporating clinical performance metrics into the optimization objective, SMAGS-LASSO addresses a critical limitation of conventional regularization methods that prioritize general prediction accuracy over clinically-relevant classification thresholds [8] [29].

The demonstrated ability to achieve near-perfect sensitivity (1.00) at exceptionally high specificity (99.9%) in synthetic data, along with substantial improvements in real-world colorectal cancer biomarker data, suggests SMAGS-LASSO could enable more effective early cancer detection tools [8] [31]. This performance is particularly valuable in screening contexts where minimizing false negatives (missed cancers) is paramount, while maintaining low false positive rates to avoid unnecessary invasive procedures [29].

From a research perspective, SMAGS-LASSO introduces a framework for domain-specific regularization that could extend beyond cancer diagnostics to other medical domains where specific performance tradeoffs carry clinical significance. The methodology demonstrates how incorporating domain knowledge directly into the machine learning objective function can yield substantial practical improvements.

SMAGS-LASSO represents a specialized regularization approach that successfully integrates clinical operating requirements with feature selection for cancer biomarker discovery. Experimental evidence demonstrates its superior performance for sensitivity maximization at high specificity thresholds compared to standard LASSO and Random Forest methods.

For researchers selecting regularization methods in cancer detection contexts, SMAGS-LASSO offers a compelling option when the clinical context prioritizes specific sensitivity-specificity tradeoffs. Its performance advantages come with increased computational complexity, but the availability of open-source implementation facilitates further validation and application across diverse cancer detection challenges.

As biomarker discovery continues to evolve, methodologically sophisticated approaches like SMAGS-LASSO that align technical objectives with clinical requirements will play an increasingly important role in translating high-dimensional data into effective diagnostic tools.

The identification of reliable biomarkers is a critical step in the development of accurate diagnostic and prognostic tools for cancer. Gene expression datasets present a significant analytical challenge due to their high-dimensional nature, often containing thousands of genes relative to a small number of patient samples. This "curse of dimensionality" can negatively impact classification model accuracy and increase computational load [3] [35]. Nature-inspired optimization algorithms (NIOAs) have emerged as powerful computational tools to address this challenge by identifying minimal, biologically relevant gene markers from complex datasets [36] [37].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of three such algorithms—Coati Optimization Algorithm (COA), Armadillo Optimization Algorithm (AOA), and Bacterial Foraging Optimization (BFO)—within the context of cancer biomarker selection. These metaheuristic algorithms are gaining prominence in computational oncology for their global search capabilities and efficiency in handling high-dimensional biological data [38]. We objectively evaluate their performance based on published experimental data, detail their methodological frameworks, and visualize their application workflows to assist researchers in selecting appropriate optimization tools for precision medicine applications.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The performance of COA, AOA, and BFO has been validated across various cancer types and data modalities. The table below summarizes their reported efficacy in key studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Nature-Inspired Optimization Algorithms in Cancer Research

| Algorithm | Cancer Type/Application | Dataset(s) Used | Key Metrics | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coati Optimization Algorithm (COA) | Breast Cancer (Mitotic Nuclei) | Histopathological images [39] | Segmentation & Classification Accuracy | 98.89% accuracy [39] |

| Coati Optimization Algorithm (COA) | Genomics Diagnosis (Multi-Cancer) | Multiple gene expression datasets [4] | Classification Accuracy | 97.06%, 99.07%, and 98.55% accuracy on three datasets [4] |

| Armadillo Optimization Algorithm (AOA) | Leukemia (AML, ALL) | Gene expression data [3] [35] | Classification Accuracy | 100% accuracy with 34 selected genes [3] [35] |

| Armadillo Optimization Algorithm (AOA) | Ovarian Cancer | Gene expression data [3] [35] | Accuracy, AUC-ROC | 99.12% accuracy, 98.83% AUC-ROC with 15 genes [3] [35] |

| Armadillo Optimization Algorithm (AOA) | Central Nervous System (CNS) Cancer | Gene expression data [3] [35] | Classification Accuracy | 100% accuracy with 43 selected genes [3] [35] |

| Bacterial Foraging Optimization (BFO) | Breast Cancer | DDSM Mammogram dataset [40] | Detection Accuracy | Outperformed VGG19 by 7.62% and InceptionV3 by 9.16% in accuracy [40] |

| Bacterial Foraging Optimization (BFO) | Colon Cancer (Drug Discovery) | Molecular profiles from TCGA, GEO [41] | Accuracy, Specificity, Sensitivity, F1-Score | 98.6% accuracy, 0.984 specificity, 0.979 sensitivity, 0.978 F1-score [41] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Coati Optimization Algorithm (COA) in Histopathology

The COA was designed for mitotic nuclei segmentation and classification in breast histopathological images, a critical task for cancer grading. The methodology mimics coati behavior involving hunting iguanas and escaping predators [39] [38].

Workflow Protocol:

- Image Pre-processing: Implement Median Filtering (MF) to reduce noise and enhance image quality for subsequent segmentation [39].

- Nuclei Segmentation: Utilize a Hybrid Attention Fusion U-Net (HAU-UNet) model to delineate mitotic nuclei precisely from the complex tissue background [39].

- Feature Extraction: Employ a Capsule Network (CapsNet) to capture spatial hierarchies and relationships within the segmented nuclei. The hyperparameters of the CapsNet are optimized using the COA [39].

- Classification: Use a Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (BiLSTM) network for the final classification of cells as mitotic or non-mitotic [39].

The integration of COA for hyperparameter tuning was crucial in achieving the reported high accuracy of 98.89% [39].

Armadillo Optimization Algorithm (AOA) for Gene Selection

The AOA is applied as a feature selection method to refine the gene pool to a highly informative subset for cancer classification [3] [35].

Workflow Protocol:

- Pre-processing: The gene expression data is normalized and prepared for analysis.

- Feature Selection with AOA: The algorithm refines gene selection through a dual-phase strategy:

- Classification: The selected subset of genes is used to train a Support Vector Machine (SVM) classifier. The SVM then distinguishes between cancerous and healthy tissues with high precision [3] [35].

This AOA-SVM hybrid approach demonstrated its capability for high-precision classification, achieving perfect 100% accuracy on leukemia and CNS datasets [3] [35].

Bacterial Foraging Optimization (BFO) in Mammography and Drug Discovery

BFO is used to optimize deep learning models, enhancing their performance in cancer detection and drug discovery [40] [41].

Workflow Protocol for Mammogram Analysis:

- Image Pre-processing: Mammogram images are resized, cropped, and enhanced using techniques like Contrast Limited Adaptive Histogram Equalization (CLAHE). Noise is reduced using Gaussian or median filters [40].

- Data Augmentation: The dataset is artificially expanded using geometric transformations (rotation, flipping) and intensity adjustments to improve model generalizability [40].

- Hyperparameter Optimization with BFO: The BFO algorithm automates the tuning of critical Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) hyperparameters, including filter size, the number of filters, and hidden layers [40].

- Classification: The optimized CNN model analyzes the preprocessed mammograms to detect breast mass tumors [40].

In colon cancer research, an Adaptive BFO (ABF) variant was integrated with the CatBoost classifier. This ABF-CatBoost system was used to analyze high-dimensional molecular data (gene expression, mutations) to predict drug responses and facilitate a multi-targeted therapeutic approach, achieving 98.6% accuracy [41].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for applying these nature-inspired algorithms to cancer biomarker discovery and classification, integrating key steps from the cited methodologies.

Figure 1: Generalized Workflow for Cancer Biomarker Selection and Classification Using Nature-Inspired Algorithms.

The experimental protocols leveraging COA, AOA, and BFO rely on several key computational and data resources. The table below details these essential components.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Computational Experiments

| Resource/Solution | Function in the Workflow | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Gene Expression Datasets | Provide the high-dimensional input data for biomarker discovery and model training. | Microarray or RNA-Seq data from sources like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) or Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [41]. |