One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR: Choosing the Optimal Protocol for Cancer Biomarker Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR protocols for cancer biomarker applications.

One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR: Choosing the Optimal Protocol for Cancer Biomarker Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on selecting between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR protocols for cancer biomarker applications. It covers foundational principles, practical methodological workflows, and optimization strategies, supported by recent clinical validation studies. The content explores how the choice of protocol impacts sensitivity, throughput, and flexibility in detecting diverse transcriptional biomarkers, including mRNA, lncRNA, and miRNA, from various sample types such as FFPE tissues and liquid biopsies. The goal is to empower scientists with the knowledge to implement robust, reproducible RT-qPCR assays that enhance the accuracy of cancer diagnosis and prognosis.

RT-qPCR Fundamentals and Transcriptional Biomarkers in Cancer

Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) is a cornerstone technique in molecular biology, particularly in the advancing field of cancer biomarker research. This method allows for the sensitive detection and quantification of RNA transcripts, enabling researchers to investigate gene expression profiles associated with different cancer subtypes, treatment responses, and disease progression. The first critical consideration in any RT-qPCR experiment is the choice between a one-step or a two-step protocol. This document outlines the core principles, detailed methodologies, and practical applications of both approaches within the context of cancer research, providing a structured guide for scientists and drug development professionals.

Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

In RT-qPCR, RNA is first reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA), which is then amplified and quantified using the polymerase chain reaction. The fundamental difference between the one-step and two-step methods lies in the execution of these two processes.

- One-step RT-qPCR: The reverse transcription and the PCR amplification are performed sequentially in a single, sealed reaction tube using a single enzyme mix [1] [2]. This method typically relies on gene-specific primers for the reverse transcription step.

- Two-step RT-qPCR: The reverse transcription and PCR amplification are performed as two separate, discrete reactions in different tubes [1] [3]. The first step generates a stable cDNA archive from the total RNA sample, and an aliquot of this cDNA is then used as a template for multiple, subsequent qPCR reactions.

The choice between these methods has profound implications for workflow, data quality, and application suitability, especially in a cancer research setting where sample material is often precious, and targets are multiple.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of one-step vs. two-step RT-qPCR

| Parameter | One-Step RT-qPCR | Two-Step RT-qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Workflow & Throughput | Simple, fast, and amenable to high-throughput automation [1] | More time-consuming and less amenable to high-throughput workflows [1] |

| Handling & Risk | Reduced pipetting steps, minimizing hands-on time and risk of contamination [1] [3] | Increased number of pipetting steps, raising the risk of contamination and pipetting errors [1] |

| Flexibility & Optimization | Limited; reaction conditions are a compromise for both RT and PCR, preventing independent optimization [1] [3] | High; allows for separate optimization of the RT and qPCR steps for maximum sensitivity and efficiency [1] |

| cDNA Archive | No cDNA archive is created; all cDNA is consumed in the subsequent PCR [1] | A stable cDNA bank is generated, which can be stored and used for analyzing multiple targets over time [1] [3] |

| Priming Strategy | Typically uses gene-specific primers [2] [3] | Can use oligo(dT), random hexamers, gene-specific primers, or a mixture for broader cDNA representation [3] |

| Sample Requirement | Requires more RNA for multiple gene targets, as each reaction consumes a separate RNA aliquot [3] | Ideal for limited samples; a single RT reaction provides cDNA for many qPCR assays [2] [3] |

| Best Suited For | High-throughput screening of a few known targets (e.g., diagnostic viral detection) [1] [2] | Research applications analyzing many targets from a single sample (e.g., cancer biomarker panels) [1] [3] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for One-Step RT-qPCR

This protocol is designed for the rapid quantification of specific RNA targets, such as in the validation of a known cancer biomarker.

Materials:

- One-Step RT-qPCR commercial kit (e.g., Power SYBR Green RNA-to-CT 1-Step Kit)

- RNA template (50–500 ng total RNA per reaction)

- Gene-specific forward and reverse primers

- Nuclease-free water

- Optical reaction tubes or plates

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: On ice, prepare a master mix for all reactions containing the one-step reaction buffer, reverse transcriptase, DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and nuclease-free water. Add gene-specific primers to the master mix.

- Aliquot and Add Template: Aliquot the master mix into the reaction tubes. Then, add the RNA template to each tube. Include no-template controls (NTC) by replacing RNA with nuclease-free water.

- Thermal Cycling: Place the reactions in a real-time PCR instrument and run the following program:

- Data Analysis: Determine the Cycle Threshold (Ct) values using the instrument's software. Relative quantification can be performed using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method [5].

Protocol for Two-Step RT-qPCR

This protocol is ideal for comprehensive gene expression profiling, such as subtyping breast cancers based on a panel of biomarkers (e.g., ESR, PGR, HER2, Ki67) [6].

Materials:

- Reverse Transcription kit (e.g., containing reverse transcriptase, buffer, dNTPs, RNase inhibitor)

- qPCR master mix (e.g., SYBR Green or TaqMan)

- Primers (for cDNA synthesis: oligo(dT), random hexamers, or a mix; for qPCR: gene-specific)

- RNA template

- Nuclease-free water

Procedure: Step 1: cDNA Synthesis

- Primer Annealing: In a nuclease-free tube, combine 1 μg to 1 pg of total RNA [4] with primers (e.g., 500 ng of random hexamers [7]) and nuclease-free water. Heat the mixture to 70°C for 3 minutes to denature secondary structures, then immediately place on ice.

- Reverse Transcription: Add a master mix containing reaction buffer, dNTPs, DTT, RNase inhibitor, and reverse transcriptase (e.g., 200 U of Superscript II [7]). The typical reaction volume is 20–30 μL.

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction as follows:

- Storage: The synthesized cDNA can be stored at -20°C for future use.

Step 2: Quantitative PCR

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a qPCR master mix containing the qPCR buffer, DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and gene-specific primers. For probe-based detection, include the appropriate fluorescent probe.

- Aliquot and Add Template: Aliquot the master mix into the reaction plates. Add a diluted aliquot (e.g., 2–5 μL) of the cDNA from Step 1 as the template.

- Thermal Cycling: Run the reactions in a real-time PCR instrument using a program such as:

- Data Analysis: Calculate the Ct values. For relative quantification, use the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method, ensuring that the amplification efficiencies of the target and reference genes are close to 100% [5].

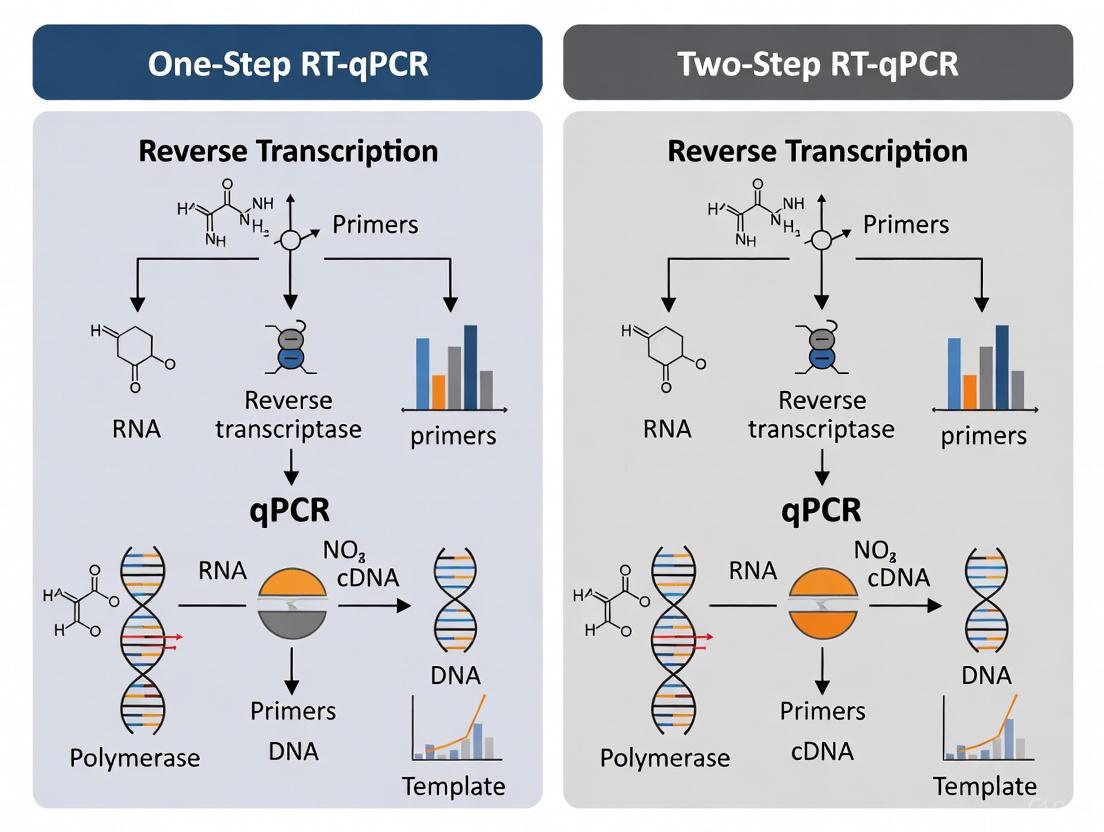

Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate the logical flow and component differences between the one-step and two-step RT-qPCR methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The reliability of RT-qPCR data, especially in a complex field like cancer research, depends heavily on the quality of reagents used. The following table details essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for RT-qPCR in cancer biomarker studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Thermostable Reverse Transcriptase | Engineered enzymes (e.g., SuperScript IV, ThermoScript) that function at elevated temperatures. This enhances efficiency by melting RNA secondary structures and improves specificity, leading to higher cDNA yields and better representation of the transcriptome [8] [2]. |

| One-Step RT-qPCR Kit | A specialized commercial kit containing optimized blends of reverse transcriptase and thermostable DNA polymerase in a single buffer. These are ideal for high-throughput, reproducible assays of a limited number of targets and minimize hands-on time [1] [4]. |

| cDNA Synthesis Primers | Oligo(dT) Primers: Bind to the poly-A tail of mRNA, enriching for mRNA. Random Hexamers: Prime RNA at multiple sites throughout the transcriptome, useful for degraded RNA (e.g., from FFPE samples) or non-polyadenylated RNA. Gene-Specific Primers: Provide the highest sensitivity for a single target but preclude multiple assays from one RT reaction [3]. |

| qPCR Master Mix | A pre-mixed solution containing hot-start DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and buffer. SYBR Green mixes intercalate with any double-stranded DNA, while TaqMan probe-based mixes offer superior specificity through a fluorescently labeled, target-specific probe, which is crucial for multiplex assays [6] [9]. |

| Sequence-Specific Primers & Probes | Oligonucleotides designed for high specificity and efficiency (~100%). For cancer biomarker panels (e.g., HER2, ESR1), primers and dual-labeled hydrolysis probes are designed to uniquely identify each transcript, often across exon-exon junctions to avoid genomic DNA amplification [6] [5]. |

| Stable Reference Genes | Genes with constant expression across experimental conditions (e.g., RPL13A, GAPDH) used for data normalization. Validation of reference gene stability is critical for accurate relative quantification in cancer tissues, as traditional "housekeeping" genes can vary [6] [5]. |

Application Notes and Protocols for Cancer Biomarker Research

Transcriptional biomarkers, including messenger RNA (mRNA), long non-coding RNA (lncRNA), and microRNA (miRNA), are indispensable tools in modern oncology. They provide critical insights into the presence, behavior, and therapeutic vulnerabilities of cancer, enabling advances in early detection, prognosis, and personalized treatment strategies [10]. The accurate quantification of these RNA species often relies on reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR). The choice between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR protocols is a critical methodological decision that impacts the efficiency, sensitivity, and applicability of biomarker research, particularly within the complex and often degraded RNA samples derived from clinical cancer specimens [11] [12].

Landscape and Clinical Utility of Transcriptional Biomarkers

Table 1: Characteristics and Cancer Applications of Transcriptional Biomarkers

| Biomarker Class | Key Characteristics | Example Cancer Functions | Representative Biomarkers & Clinical Associations |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | - Protein-coding transcripts- Variable length and stability- Expression reflects direct cellular phenotype | - Oncogene activation- Tumor suppressor inactivation- Treatment target identification | - PD-L1: Predictive for immunotherapy response in NSCLC and melanoma [10].- HER2: Prognostic and predictive in breast cancer [10]. |

| lncRNA | - >200 nucleotides, non-coding- Regulate gene expression via multiple mechanisms- Can act as miRNA "sponges" (ceRNA network) | - Chromatin remodeling- Transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation- Key roles in neurogenerative pathways | - MIAT: Identified in a ceRNA network potentially affecting cell cycle regulation [13]. |

| miRNA | - ~22 nucleotides, non-coding- High stability in tissues and circulation (e.g., plasma)- Post-transcriptional regulators of mRNA | - Modulate oncogenic pathways (e.g., PI3K-Akt, Wnt) [14]- Predictive of therapy response | - miR-16-5p, miR-93-5p, miR-126-3p: High baseline plasma levels predictive of better response and survival in advanced biliary tract cancer patients on chemoimmunotherapy [15].- miR-21: High tissue expression independently predicts worse overall survival in HCC [16]. |

Core Protocol: One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR for Biomarker Assays

The decision between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR is fundamental to experimental design in biomarker validation. The following workflow and table summarize the key considerations.

Table 2: Comparative Guide to One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR

| Parameter | One-Step RT-qPCR | Two-Step RT-qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Workflow & Throughput | Combined RT and PCR in a single tube. Ideal for high-throughput processing of many samples [11] [12]. | Separate, optimized reactions for RT and PCR. Less amenable to high-throughput [11] [12]. |

| Priming Strategy | Uses sequence-specific primers only [11]. | Flexible: oligo(dT), random hexamers, or gene-specific primers [11]. |

| Sensitivity & Efficiency | Potentially lower sensitivity as conditions are a compromise for both reactions [12]. | Higher sensitivity; reactions can be independently optimized [12]. |

| cDNA Utility | All cDNA is consumed in the subsequent PCR; no cDNA bank is created [12]. | A stable cDNA pool is generated and can be used for multiple assays or stored long-term [11] [12]. |

| Key Advantages | - Simplified workflow, faster- Reduced pipetting errors & contamination risk- Highly reproducible [11] [12] | - Flexible priming & optimization- cDNA can be used for multiple targets- Generally more sensitive [11] [12] |

| Key Disadvantages | - Impossible to optimize reactions separately- Less sensitive- Limited targets per sample [11] [12] | - More time-consuming- Greater risk of contamination due to handling- Requires more optimization [11] [12] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Validating a Circulating miRNA Signature for Therapy Response

This protocol outlines the steps for identifying and validating a circulating miRNA biomarker signature predictive of response to chemoimmunotherapy, as demonstrated in advanced biliary tract cancer [15].

4.1 Sample Collection and Preparation

- Patient Cohort: Recruit patients according to a defined clinical trial protocol (e.g., patients with advanced biliary tract cancer receiving first-line nivolumab, gemcitabine, and S-1) [15].

- Sample Type: Collect peripheral blood plasma samples prospectively at baseline (pre-treatment) and at a defined timepoint after treatment initiation (e.g., 6 weeks) [15].

- RNA Isolation: Extract total RNA from plasma using Trizol reagent or a specialized commercial kit for cell-free RNA. Ensure methods are optimized for low-concentration targets [13].

4.2 miRNA Profiling and Sequencing

- Library Preparation: Construct miRNA sequencing libraries from the isolated total RNA. For a focused approach, a pre-defined panel of miRNAs (e.g., 167 miRNAs) can be used [15].

- Sequencing: Perform sequencing on a high-throughput platform (e.g., 50-bp single-end reads). Quantify expression levels using transcripts per million (TPM) for normalization [13].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identify significantly differentially expressed miRNAs between responder (Complete Response/Partial Response) and non-responder (Stable Disease/Progressive Disease) groups using statistical packages (e.g., DEGseq R package). Apply a false discovery rate (FDR)-corrected p-value threshold (e.g., < 0.01) and a log2 fold change cutoff (e.g., > 1) [15] [13].

4.3 Machine Learning-Based Classifier Development

- Feature Selection: Select top candidate miRNAs (e.g., hsa-miR-16-5p, hsa-miR-93-5p, hsa-miR-126-3p) that are detectable in >80% of samples and show significant differential expression [15].

- Model Training & Validation: Develop an miRNA-based classifier using a machine learning approach (e.g., 10-fold cross-validation) on the initial cohort (training set). Validate the classifier's sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy using an independent patient cohort (testing set) [15].

4.4 Association with Clinical Outcomes

- Survival Analysis: Correlate the expression levels of the identified miRNA signature with patient progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) using Kaplan-Meier curves and Cox proportional hazards models to calculate hazard ratios (HR) [15].

- Functional Enrichment Analysis: Use databases like STRING-DB and visualization tools like Cytoscape to perform functional enrichment analysis. This identifies hub genes (e.g., TP53, AKT1, MTOR) and pathways through which the miRNAs may exert their effects, linking the signature to biology [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Transcriptional Biomarker Research

| Reagent / Solution | Function & Application in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Trizol Reagent | A monophasic solution of phenol and guanidine isothiocyanate used for the simultaneous isolation of RNA (including miRNA), DNA, and proteins from various sample types, including cells and tissues [13]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Enzyme that synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template. Critical for both one-step and two-step RT-qPCR protocols [11]. |

| Sequence-Specific Primers | Short, designed oligonucleotides that bind to a specific RNA transcript. Used in one-step RT-qPCR and the PCR step of two-step RT-qPCR for target amplification [11]. |

| Oligo(dT) Primers | Short sequences of deoxythymidine nucleotides that bind to the poly-A tail of mRNAs. Used in the RT step of two-step protocols to prime coding transcripts [11]. |

| Random Hexamers | Short oligonucleotides of random sequence that bind non-specifically to RNA. Used in the RT step of two-step protocols to prime all RNA, including non-coding RNAs like miRNA and lncRNA [11]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | A modified enzyme inactive at room temperature, preventing non-specific amplification during reaction setup. Used in the PCR step to enhance specificity and yield [11]. |

Pathway Diagram: miRNA-Mediated Regulation of Cancer Pathways

The following diagram illustrates how a validated miRNA signature can interact with key cancer-associated pathways to influence tumor biology and treatment response, as suggested by functional enrichment analyses [14] [15].

Quality Control and Adherence to MIQE 2.0 Guidelines

The rigorous validation of RT-qPCR assays is paramount for generating reliable and reproducible data, especially in a clinical research context. Adherence to the MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) 2.0 guidelines is strongly recommended [17] [18]. Key considerations include:

- Sample Quality: Properly document sample handling, processing, and storage. Assess RNA integrity and quantity using appropriate methods [17].

- Assay Validation: Validate the specificity and efficiency of all qPCR assays. Efficiency should be measured, not assumed [17].

- Appropriate Normalization: Use stable, validated reference genes for data normalization. The choice of reference genes must be justified for the specific sample type and experimental condition [17].

- Transparent Reporting: Provide comprehensive methodological details to ensure experimental transparency and reproducibility [17] [18].

The evolution of molecular diagnostics has positioned nucleic acid biomarkers as powerful tools in cancer research and drug development. These biomarkers, including DNA, messenger RNA (mRNA), and non-coding RNAs (such as miRNA, circRNA, and lncRNA), offer distinct advantages over traditional protein biomarkers, primarily due to their inherent detectability at extremely low concentrations and the availability of powerful amplification techniques like PCR [19] [20].

The transition from protein-based detection methods, which have a long history dating back to the Wassermann test for syphilis in 1906, to nucleic acid-based techniques represents a significant paradigm shift [19]. This application note details these advantages, providing a focused comparison and detailed protocols to guide researchers in selecting the optimal methods for cancer biomarker analysis, specifically through the lens of one-step and two-step RT-qPCR.

Comparative Advantages of Nucleic Acid Biomarkers

Enhanced Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity

The core advantage of nucleic acid biomarkers lies in their potential for exceptional sensitivity. Techniques like digital PCR (dPCR) can achieve single-molecule sensitivity, enabling the detection of rare mutant sequences in a background of wild-type DNA, such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) with a variant allele frequency (VAF) as low as 0.1%, a feat difficult to match with standard protein immunoassays [19]. This sensitivity is crucial for early cancer detection via liquid biopsy, where biomarker concentration is minimal.

Specificity is ensured by the predictable base-pairing of nucleic acids, which allows for the precise design of primers and probes to uniquely identify a target sequence. Protein detection, reliant on antibody-antigen interactions, can sometimes be hampered by cross-reactivity or the limited availability of high-quality, specific antibodies [21].

Powerful Signal and Target Amplification

A fundamental differentiator is the ability to directly amplify the nucleic acid target itself. Methods like PCR can generate millions of copies of a target sequence from a single molecule, dramatically boosting the signal [19]. Protein biomarkers, in contrast, lack a direct equivalent to PCR. While signal amplification strategies exist (e.g., digital ELISA), they cannot amplify the target molecule, ultimately limiting their sensitivity [19].

Table 1: Amplification Techniques for Nucleic Acid vs. Protein Biomarkers

| Feature | Nucleic Acid Biomarkers | Protein Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|

| Target Amplification | Yes (e.g., PCR, NGS) | Not possible |

| Signal Amplification | Yes (e.g., branched DNA assays) | Yes (e.g., ELISA, Simoa) |

| Exemplary Techniques | Digital PCR, Next-generation Sequencing | Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) |

| Achievable Sensitivity | Single-molecule detection (e.g., 0.1% VAF with dPCR) | <1 fM (with advanced digital ELISA) |

Cost-Efficiency and Comprehensive Profiling

RNA biomarkers can be detected at extremely low concentrations, and their analysis via techniques like next-generation sequencing offers a cost-effective way to measure genome-wide RNA expression levels [20]. This is often more economical than protein detection, which requires a specialized antibody for each target. Furthermore, the advent of massive parallel sequencing allows researchers to discover and profile a vast array of nucleic acid biomarkers—including novel non-coding RNAs and methylation patterns—from a single experiment, providing a comprehensive view of the transcriptome that is more challenging and expensive to achieve at the proteome level [20].

Core Experimental Protocol: One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR

Reverse Transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) is the gold standard for quantifying RNA biomarkers. The critical methodological choice is between one-step and two-step protocols, a decision that impacts sensitivity, flexibility, and throughput.

Workflow and Decision Framework

The diagram below illustrates the key steps and differences between the two main RT-qPCR approaches.

Detailed Methodologies

One-Step RT-qPCR Protocol

This protocol is ideal for high-throughput applications targeting a limited number of genes [22] [11].

- Reaction Setup: In a single tube, combine:

- RNA template: 1-100 ng total RNA.

- One-Step RT-qPCR master mix: Contains reverse transcriptase, DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and reaction buffer.

- Gene-specific primers: Both forward and reverse primers for the target RNA.

- Detection chemistry: e.g., SYBR Green dye or TaqMan probes.

- Thermal Cycling: Place the tube in a real-time PCR instrument and run a unified program:

- Reverse Transcription: 50°C for 10-30 minutes.

- Enzyme Inactivation/Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes.

- Amplification (40-50 cycles):

- Denature: 95°C for 15 seconds.

- Anneal/Extend: 60°C for 1 minute (with fluorescence acquisition).

- Data Analysis: Quantify the initial RNA amount based on the qPCR amplification curve (Cq value) using absolute or relative quantification methods.

Two-Step RT-qPCR Protocol

This protocol offers greater flexibility and is preferred for analyzing multiple targets from a single RNA sample [22] [23].

- Step 1: cDNA Synthesis

- Reaction Setup: In one tube, mix:

- RNA template: 1 µg - 1 pg total RNA.

- Reverse Transcriptase: (e.g., M-MLV or AMV).

- dNTPs.

- Primers: A choice of oligo(dT) (for mRNA), random hexamers (for total RNA, including non-coding RNAs), or gene-specific primers.

- Incubation: Typically 42°C-50°C for 30-60 minutes, followed by enzyme inactivation at 70°C-85°C. The synthesized cDNA can be stored for future use.

- Reaction Setup: In one tube, mix:

- Step 2: qPCR Amplification

- Reaction Setup: In a separate tube, combine:

- cDNA: A dilution (e.g., 1:10) of the product from Step 1.

- qPCR master mix: Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, and optimized buffer.

- Gene-specific primers and detection chemistry (SYBR Green or TaqMan probes).

- Thermal Cycling: Standard qPCR program (without the RT step):

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 3 minutes.

- Amplification (40-50 cycles): 95°C for 15 sec, 60°C for 1 minute (with fluorescence acquisition).

- Reaction Setup: In a separate tube, combine:

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR

| Parameter | One-Step RT-qPCR | Two-Step RT-qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Workflow & Throughput | Simple, fast, fewer pipetting steps. Ideal for high-throughput analysis of many samples with few targets [11] [23]. | More complex, time-consuming, multiple pipetting steps. Less amenable to high-throughput [11]. |

| Sensitivity & Efficiency | Potentially lower sensitivity as conditions are a compromise for both RT and PCR [11]. | Higher sensitivity; each step (RT and PCR) can be individually optimized for maximum efficiency [23]. |

| Flexibility & cDNA Usage | No cDNA stock generated; all cDNA is consumed in the single reaction [22]. | Stable cDNA pool is generated and can be stored for long periods, allowing analysis of multiple targets from the same sample [11] [23]. |

| Priming Strategy | Restricted to gene-specific primers only [22]. | Flexible: oligo(dT), random hexamers, or gene-specific primers can be used [11]. |

| Risk of Contamination | Lower risk, as the sample remains in a single, closed tube [22]. | Higher risk due to additional tube handling and pipetting steps [11]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of RNA biomarker detection relies on key reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for RT-qPCR

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template. | Enzymes like M-MLV and AMV are commonly used. Critical for first-strand synthesis [22]. |

| Thermostable DNA Polymerase | Amplifies the cDNA target during PCR. | Often part of a master mix. Fidelity and processivity are key for accurate quantification. |

| Primers | Sequence-specific oligonucleotides that define the target to be amplified. | Gene-specific for one-step; Oligo(dT), Random Hexamers, or Gene-specific for two-step RT-qPCR [11]. |

| Fluorescent Detection Chemistry | Generates a quantifiable signal proportional to the amount of amplified DNA. | SYBR Green (binds dsDNA, cost-effective) or TaqMan Probes (sequence-specific, higher multiplexing potential) [22]. |

| RNase Inhibitors | Protects the integrity of the RNA template from degradation. | Essential for obtaining reliable and reproducible results, especially when working with low-abundance targets. |

| Magnetic Beads / Spin Columns | For solid-phase extraction and purification of RNA from complex biological samples. | Ensures high-quality RNA free of inhibitors that could compromise the RT-qPCR reaction. |

Nucleic acid biomarkers provide researchers and drug developers with a powerful and versatile platform for cancer research, offering superior sensitivity, the unique capability of target amplification, and cost-effective profiling. The choice between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR is central to exploiting these advantages. One-step RT-qPCR offers a streamlined, closed-tube workflow best suited for high-throughput studies focusing on a limited set of targets. In contrast, two-step RT-qPCR provides unmatched flexibility, sensitivity, and the ability to create a renewable cDNA resource, making it the preferred method for biomarker discovery and validation studies where analyzing multiple targets from precious sample material is paramount. Understanding these distinctions allows for the strategic design of robust and informative experiments in precision oncology.

The accurate analysis of cancer biomarkers is fundamentally dependent on the choice of sample type and the corresponding molecular methodology. Each sample type—Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissues, liquid biopsies, and stool samples—presents unique advantages, challenges, and appropriate protocol adaptations. Within this context, the decision between one-step and two-step reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) methodologies becomes particularly significant, as the compatibility of each approach varies considerably across different sample matrices. FFPE tissues, while offering vast archival resources, contain fragmented and cross-linked RNA that demands specific protocol adjustments [24] [25]. Liquid biopsies, including blood samples analyzed for circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), provide a minimally invasive means for dynamic monitoring but require extremely sensitive detection methods to identify rare biomarkers [26] [27]. Stool samples, an emerging substrate for gastrointestinal cancers, contain eukaryotic RNA that holds promise for non-invasive detection but exists in a challenging environment dominated by microbial transcripts and inhibitors [28] [29]. This application note delineates detailed, optimized protocols for each sample type, framed within the critical methodological choice of one-step versus two-step RT-qPCR, to guide researchers in generating reliable and reproducible gene expression data for cancer biomarker research.

Sample Type Characteristics and Workflow Selection

The selection of an appropriate sample type is guided by research objectives, requiring a balance between clinical feasibility and analytical performance. The table below summarizes the core characteristics, applications, and methodological considerations for FFPE, liquid biopsy, and stool samples.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Sample Types for Cancer Biomarker Research

| Sample Type | Core Characteristics | Primary Applications | Key Methodological Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| FFPE Tissues | - Archival, stable samples- Fragmented, cross-linked RNA- Rich in clinical follow-up data [24] [25] | - Prognostic biomarker validation- Retrospective studies- Diagnostic sub-classification [24] | - RNA fragmentation and chemical modifications impair primer annealing [25]- Requires robust RNA extraction and sensitive detection |

| Liquid Biopsies | - Minimally invasive collection- Enables dynamic monitoring- Contains CTCs, ctDNA, exosomes [26] [27] | - Early cancer screening- Monitoring treatment response- Tracking minimal residual disease (MRD) [26] [27] | - Extremely low abundance of targets (e.g., 1-100 CTCs/mL blood) [27]- Requires high-sensitivity enrichment and detection platforms |

| Stool Samples | - Non-invasive collection- Direct contact with colonic epithelium- Rich in microbes and inhibitors [28] | - Detection of colorectal cancer (CRC)- Detection of adenomatous polyps [28] | - Low abundance of human mRNA relative to bacterial RNA [28]- Requires user-friendly extraction and highly specific detection |

The following workflow illustrates the strategic decision process for selecting and analyzing these sample types, with integrated points for the one-step vs. two-step RT-qPCR decision.

Diagram 1: Sample type selection and analytical workflow.

Detailed Protocols by Sample Type

Protocol 1: Optimized RNA Extraction and qPCR from FFPE Tissues

FFPE tissues are a cornerstone of cancer research due to their wide availability and linked clinical data. However, the formalin fixation process fragments RNA and introduces chemical modifications, necessitating a robust workflow from RNA isolation to cDNA synthesis and amplification [25].

Step 1: RNA Isolation and Quality Control

- Use specialized kits designed for FFPE material (e.g., from Qiagen or Epicentre) that incorporate extended proteinase K digestion and heat steps to reverse cross-links [25].

- Assess RNA purity by spectrophotometry (OD 260/280, with acceptable values ranging from 1.52 to 2.16) [24]. Note that RNA Integrity Number (RIN) is often low for FFPE RNA; therefore, focus on purity and amplifiability.

Step 2: cDNA Synthesis – Key Considerations for One-Step vs. Two-Step

- For Maximum Sensitivity with Two-Step RT-qPCR: Use a high-volume cDNA synthesis reaction (e.g., 100 µL) starting with 1000 ng of RNA. This approach has been shown to yield lower Ct values and lower variation within replicates compared to low-volume protocols [24]. Employ a mix of random hexamers and oligo-dT primers for whole-transcriptome conversion, or use gene-specific priming for superior sensitivity when targeting a predefined gene set [25].

- Gene-Specific Reverse Transcription: For a 48-plex gene-specific cDNA synthesis, add qPCR primers to the reverse transcription reaction at 100 nM concentration. This method can improve qPCR sensitivity by a factor of 4.0 compared to whole-transcriptome reverse transcription, enabling earlier detection by an average of 2.0 PCR cycles [25].

Step 3: qPCR Amplification

- Two-Step with Preamplification: For the most sensitive detection from FFPE material, include a targeted cDNA preamplification step using a pool of gene-specific primers. This can improve sensitivity by an average of 172-fold (7.43 PCR cycles) while maintaining gene expression ratios [25].

- Design qPCR amplicons to be short (<100 bp) to accommodate fragmented RNA [25].

- Chemistry Selection: Both Taqman probes and SYBR Green can be used effectively, with studies showing good correlation between the two chemistries [24].

Liquid Biopsies: Capturing the Dynamic Picture

Protocol 2: Targeting Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) and Cell-Free DNA (cfDNA)

Liquid biopsy focuses on analyzing tumor-derived components in the blood, primarily CTCs and ctDNA. Its non-invasive nature allows for repeated sampling to monitor disease progression and treatment response [26] [27].

Step 1: Sample Collection and Plasma Separation

- Collect blood into EDTA or specialized cell-stabilization tubes.

- Process samples within a few hours to prevent degradation and lysis of background blood cells.

- Centrifuge to separate plasma (for ctDNA/exosome analysis) from the cellular fraction (for CTC analysis).

Step 2: Biomarker Enrichment and Isolation

- CTC Enrichment: Due to their extreme rarity (~1-10 CTCs per mL of blood among millions of leukocytes), enrichment is critical [26].

- Immunomagnetic Methods: The CellSearch system, FDA-cleared for prognostic use in certain cancers, uses anti-EpCAM antibodies to positively select CTCs [26] [27]. A key limitation is the potential for missing EpCAM-negative CTCs that have undergone epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).

- Size-Based Methods: Technologies like ISET (Isolation by Size of Epithelial Tumor Cells) use microfilters to separate larger CTCs from smaller blood cells, independent of surface marker expression [27].

- ctDNA Extraction: Use circulating nucleic acid extraction kits to isolate cfDNA from plasma. ctDNA typically constitutes only 0.1% - 1.0% of total cfDNA, requiring highly sensitive downstream detection [26].

- CTC Enrichment: Due to their extreme rarity (~1-10 CTCs per mL of blood among millions of leukocytes), enrichment is critical [26].

Step 3: Molecular Analysis and RT-qPCR Strategy

- For CTC mRNA Analysis (Two-Step RT-qPCR is Standard):

- Lyse enriched CTCs and extract total RNA.

- Perform cDNA synthesis using a two-step kit. This allows for the use of random hexamers/oligo-dT to create a stable cDNA archive from a limited cell population, which can then be used to analyze multiple genes [30] [11].

- Utilize preamplification (e.g., 10-14 cycles) of the cDNA to enable analysis of multiple transcripts from a minute starting amount.

- For ctDNA Analysis (DNA-based qPCR):

- For CTC mRNA Analysis (Two-Step RT-qPCR is Standard):

Stool Samples: A Frontier for Non-Invasive GI Cancer Detection

Protocol 3: Eukaryotic RNA Extraction and Detection from Stool

Stool contains shed colorectal epithelial cells, and their RNA expression profile can serve as a biomarker for detecting colorectal cancer (CRC) and precancerous adenomas [28].

Step 1: Sample Collection and Preservation

- Collect stool samples prior to bowel preparation for colonoscopy.

- Immediately preserve a representative aliquot in a commercial stabilizer like RNAlater to prevent RNA degradation. Store at -80°C [28].

Step 2: Optimal RNA Extraction

- A comparative study identified the Stool Total RNA Purification Kit (Norgen) as providing high RNA purity and consistent mRNA detection, making it well-suited for large-scale studies [28].

- Standardize input (e.g., 200 µL of stool/RNAlater slurry) and include rigorous bead-beating homogenization steps.

- Perform an on-column DNase treatment to remove contaminating genomic DNA.

Step 3: One-Step RT-qPCR for Streamlined Detection

- For streamlined workflow and to minimize sample handling, the Superscript III one-step RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen) has been successfully used for direct amplification from stool RNA [28].

- The one-step format is ideal for this application when the target gene panel is predefined and limited (e.g., immune genes like IL8, IL1B, PTGS2), reducing contamination risk during high-throughput screening [28] [30].

- This protocol has demonstrated the ability to distinguish CRC and adenomatous polyp samples from controls based on elevated transcript levels of specific immune genes [28].

The Core Methodological Decision: One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR

The choice between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR is a critical determinant of success in biomarker analysis. This decision must be aligned with the sample type, RNA quality, and research goals.

Table 2: Strategic Comparison of One-Step and Two-Step RT-qPCR

| Parameter | One-Step RT-qPCR | Two-Step RT-qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Workflow | Combined RT and PCR in a single tube and buffer [30] [11] | Separate, optimized reactions for RT and PCR [30] [11] |

| Priming Strategy | Gene-specific primers only [30] [11] | Flexible: Oligo(dT), random hexamers, gene-specific, or a combination [30] [11] |

| Hands-on Time & Throughput | Minimal setup; ideal for high-throughput analysis of few targets [30] [11] | More hands-on time; better for analyzing multiple targets from few samples [30] [11] |

| Sensitivity & Efficiency | Can be less sensitive due to compromised buffer conditions [4] [11] | Potentially higher sensitivity and efficiency; reactions can be independently optimized [4] |

| Sample Archive | cDNA product cannot be saved; requires fresh RNA for new targets [30] | Stable cDNA pool is generated and can be stored for future analysis of other targets [30] [11] |

| Risk of Contamination | Low (closed-tube reaction) [30] [11] | Higher (multiple open-tube steps) [30] [11] |

| Ideal Use Case | - High-throughput diagnostic screening of a fixed gene panel- Stool sample RNA (good quality, predefined targets) [28] [30] | - FFPE samples (requires flexibility and preamplification)- CTC analysis (limited RNA, multiple targets)- Research discovery with scarce samples [24] [25] [30] |

The following diagram synthesizes the strategic decision-making process for selecting between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR across the different sample types.

Diagram 2: Decision tree for one-step vs. two-step RT-qPCR.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Kits

Selecting the right reagents is paramount for success. The following table catalogues key solutions referenced in the protocols above.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Cancer Biomarker Analysis

| Reagent / Kit Name | Function / Application | Specific Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Stool Total RNA Purification Kit (Norgen) | RNA extraction from stool | Provided high RNA purity and consistent mRNA detection in stool, optimal for downstream RT-qPCR [28]. |

| Superscript III One-Step RT-PCR Kit (Invitrogen) | One-Step RT-PCR | Identified as a well-suited candidate for sensitive mRNA detection in stool samples [28]. |

| CellSearch System | CTC Enrichment and Enumeration | FDA-cleared system using immunomagnetic EpCAM-based capture for prognostic CTC counting in various cancers [26] [27]. |

| Power SYBR Green RNA-to-CT Kits (Applied Biosystems) | One-Step & Two-Step RT-qPCR | Used in comparative studies; the 2-Step kit performed more reliably in a two-step protocol than a one-step protocol [4]. |

| LunaScript RT SuperMix Kit (NEB) | cDNA Synthesis for Two-Step RT-qPCR | Recommended for first-strand cDNA synthesis in two-step workflows, offering robust performance [30]. |

| Luna Universal One-Step RT-qPCR Kit (NEB) | One-Step RT-qPCR | A modern solution for fast, closed-tube, high-throughput one-step reactions [30]. |

The robust analysis of cancer biomarkers across FFPE, liquid biopsy, and stool samples is an integrative process that hinges on matching the sample's unique biology with a finely tuned molecular protocol. There is no universally superior choice between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR; the decision is contextual. One-step RT-qPCR offers a streamlined, low-contamination workflow ideal for high-throughput applications with predefined targets and more intact RNA, such as in stool screening. Conversely, two-step RT-qPCR provides unmatched flexibility, sensitivity, and the ability to create a valuable cDNA archive, making it the preferred method for analyzing challenging samples like FFPE tissues and rare CTCs, or when exploring multiple gene targets. By applying the optimized protocols and strategic framework outlined in this document, researchers can effectively navigate these critical choices to generate high-quality, reliable data that advances cancer research and drug development.

Protocol Selection and Workflow Implementation for Biomarker Detection

Within the field of cancer biomarker research, the selection of an appropriate reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) methodology is pivotal for generating reliable, actionable data. This application note focuses on the integrated workflow of one-step RT-qPCR, a technique where reverse transcription and PCR amplification are performed in a single, uninterrupted reaction in a closed tube [31]. This method is particularly suited for high-throughput and repetitive target analysis, offering a distinct set of advantages and limitations compared to the two-step approach [3] [32].

Framed within the broader thesis of one-step versus two-step RT-qPCR, this document provides a detailed protocol, key applications in cancer research, and data analysis guidelines to empower researchers and drug development professionals in leveraging this efficient workflow.

Advantages and Limitations in Cancer Research

The one-step RT-qPCR protocol is characterized by a streamlined process that integrates cDNA synthesis and amplification. The diagram below illustrates this integrated workflow and its primary advantages.

This integrated workflow offers several key benefits for specific research scenarios, but it is not without its constraints. The table below provides a balanced comparison of its core attributes against its limitations, which are critical to consider during experimental planning.

Table 1: Advantages and Limitations of One-Step RT-qPCR in Biomarker Research

| Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|

| Simple and rapid workflow; reduced hands-on time [31] [32] | Inability to optimize RT and qPCR steps independently, potentially leading to lower yields or efficiency [31] [32] |

| Minimized risk of contamination due to single-tube, closed-system protocol [31] [3] | No cDNA archive generated; all cDNA is consumed in the qPCR step, preventing future analysis of other targets [31] [32] |

| Ideal for high-throughput/automated systems [31] [32] | Not cost-effective for analyzing many targets from the same sample [31] |

| Efficient for processing many samples with a limited number of target genes [31] | Higher susceptibility to PCR inhibitors present in the RNA sample, as the RT step is more sensitive to contaminants [3] |

| Reduced pipetting errors [31] | Requires gene-specific primers for the reverse transcription step, limiting flexibility [3] |

Application in Cancer Biomarker Analysis

One-step RT-qPCR has proven to be a powerful tool in oncology research, particularly in scenarios demanding high throughput and reproducibility. Its application is especially valuable in virus-associated cancer studies and cancer subtyping using defined biomarker panels.

Key Research Applications

Viral Load Quantification and Oncogene Expression: The high sensitivity of one-step RT-qPCR makes it ideal for detecting and quantifying viral RNA, a crucial task in studying virus-associated cancers. For instance, it has been used to sensitively detect Zika viral RNA levels in multiple tissues of infected mice, revealing higher viral loads in testis associated with infertility [31]. This principle is directly transferable to human viral oncogenesis research, such as studying Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or human papillomavirus (HPV).

Molecular Subtyping of Cancers with Multiplexed Assays: The technique is well-suited for diagnostic panels that require simultaneous measurement of a limited number of well-characterized biomarkers. A prominent example is the molecular subtyping of breast cancer. Research has demonstrated the successful use of multiplex RT-qPCR to assess the expression profiles of HER2, ESR (ER), PGR (PR), and Ki67 genes across 61 breast cancer samples, providing a precise method for classification that rivals traditional immunohistochemistry (IHC) [6]. This objective, quantitative approach reduces the subjectivity inherent in IHC scoring [6] [33].

Angiogenesis and Metastasis Potential Assessment: Beyond standard receptor status, one-step RT-qPCR can be applied to evaluate the expression of genes involved in tumor progression. The same breast cancer study explored genes involved in angiogenesis (HIF1A, ANG, VEGFR), shedding light on the metastatic potential of tumors [6]. Elevated levels of Hif1A and VEGFR were identified as potential biomarkers for assessing metastatic status [6].

Integrated One-Step RT-qPCR Workflow

The following diagram and protocol detail the end-to-end process for performing a one-step RT-qPCR experiment, from sample preparation to data analysis, with a focus on reliability and reproducibility.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Sample Preparation and RNA Extraction

- Sample Types: The protocol can be applied to fresh frozen tissue, cell lines, or Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks [6] [33].

- RNA Extraction: Use commercial kits designed for your sample type. For FFPE samples, kits like the Quick-DNA/RNA FFPE Kit are recommended to overcome RNA fragmentation and cross-linking [6].

- Quality Control: Assess RNA concentration and purity using a spectrophotometer (e.g., NanoDrop). Acceptable 260/280 ratios are typically between 1.8 and 2.1 [6].

Reaction Setup and Plate Preparation

- Kit Selection: Commercial one-step kits, such as the One Step PrimeScript RT-PCR Kit (for probe-based detection) or the One-Step TB Green PrimeScript RT-PCR Kit II (for dye-based detection), provide pre-mixed components for convenience [31].

- Master Mix Preparation: Thaw all reagents on ice. Prepare a master mix in a sterile, nuclease-free tube to minimize pipetting variance and cross-contamination. The table in the "Research Reagent Solutions" section below details the core components.

- Plate Setup: Aliquot the master mix into the reaction plate. Add the template RNA, typically 10-100 ng per reaction for high-quality RNA. Include no-template controls (NTCs) by replacing RNA with nuclease-free water to check for contamination. Each sample and target should be run in technical replicates (at least duplicates) to ensure data reliability.

Thermal Cycling Protocol

Load the plate into a real-time PCR instrument and run a program based on the following steps, which may be adjusted according to the specific kit used and the assay design [31] [6]:

Reverse Transcription:

- 50°C for 10 minutes [6]. This step synthesizes cDNA using gene-specific primers.

Initial Denaturation:

- 95°C for 2 minutes [6]. This activates the hot-start DNA polymerase and denatures the cDNA and secondary structures.

Amplification (40-45 Cycles):

Research Reagent Solutions

A successful one-step RT-qPCR experiment relies on a set of core components, typically available in commercial kits. The following table lists these essential reagents and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for One-Step RT-qPCR

| Reagent / Component | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| One-Step RT-qPCR Kit | A commercial master mix containing optimized blends of reverse transcriptase and hot-start DNA polymerase (e.g., PrimeScript RTase and Takara Ex Taq HS) [31]. |

| Gene-Specific Primers | Oligonucleotides designed to target the cDNA sequence of interest. In one-step protocols, these are used for both the reverse transcription and PCR steps [3]. |

| Probes or Intercalating Dye | Probe-based (e.g., FAM/TAMRA): Offers high specificity [31]. Dye-based (e.g., TB Green): A cost-effective DNA intercalating dye for monitoring amplification [31]. |

| RNA Template | High-quality, intact RNA is critical. Integrity can be checked via gel electrophoresis or bioanalyzer. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | The diluent for reactions, ensuring no RNase or DNase activity that would degrade the reaction components. |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Accurate data analysis is the final, critical step. The Quantification Cycle (Cq) is the primary data point generated, but its correct interpretation is paramount.

Key Considerations for Reliable Cq Analysis

- Cq is a Relative Measure: The observed Cq value is not only dependent on the initial target concentration but also on the PCR efficiency and the level of the quantification threshold [34]. Therefore, Cq values from different runs, machines, or laboratories cannot be directly compared.

- PCR Efficiency is Crucial: Interpreting Cq values while assuming a 100% efficient PCR can lead to gross inaccuracies in calculated gene expression ratios [34]. It is essential to account for the actual amplification efficiency of each assay.

- The ΔΔCq Method: For relative quantification, the ΔΔCq method is commonly used to calculate fold changes in gene expression [6]. This method uses the formula 2^(-ΔΔCq) to determine the fold change of a target gene in a test sample relative to a control sample, after normalization to one or more reference genes [6].

The data analysis pipeline, from raw Cq to biological interpretation, involves several validation and normalization steps, as summarized below.

Critical Validation Steps

- Amplification Efficiency: Calculate the efficiency (E) of your qPCR assay using a standard curve dilution series. The formula

E = -1 + 10^(-1/slope)is typically used, with ideal efficiency between 90-110% [6]. - Reference Gene Selection: Choose stable, validated reference genes (e.g., RPL13A, GAPDH) for normalization. Their expression should not vary under your experimental conditions [6].

In the field of cancer biomarker research, where sample quantities are often severely limited and the need to analyze multiple genetic targets is paramount, selecting the appropriate molecular detection method is crucial for experimental success. Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) serves as a cornerstone technology for gene expression analysis, yet researchers must choose between one-step and two-step methodological approaches. While one-step RT-qPCR offers procedural simplicity by combining reverse transcription and PCR amplification in a single tube [35] [11], this method presents significant limitations for comprehensive biomarker studies where the same precious sample must be analyzed for multiple targets.

Two-step RT-qPCR addresses these challenges by physically separating the reverse transcription and PCR amplification processes into distinct reactions [35] [11]. This strategic separation creates a stable cDNA archive that can be utilized for numerous downstream applications, making it particularly valuable for cancer research involving rare patient samples, biobank specimens, or longitudinal studies where material preservation is essential [3] [36]. The enhanced flexibility of two-step RT-qPCR enables researchers to maximize the informational yield from each limited clinical sample, thereby accelerating biomarker discovery and validation workflows without compromising experimental rigor or reproducibility.

Key Advantages of the Two-Step Approach for Multi-Target Analysis

Experimental Design Flexibility

The two-step method fundamentally differs from one-step approaches by decoupling cDNA synthesis from subsequent PCR amplification, creating opportunities for experimental optimization that are simply not possible with combined protocols [35] [11]. This separation enables independent optimization of each reaction component, allowing researchers to fine-tune buffer conditions, enzyme concentrations, and thermal cycling parameters specifically for reverse transcription or PCR amplification [36]. Such optimization capabilities are particularly valuable when working with challenging RNA samples derived from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues, which are common in cancer biomarker research but often yield partially degraded or chemically modified RNA [33].

The two-step workflow generates a permanent cDNA archive that can be stored long-term at -20°C, dramatically enhancing experimental flexibility compared to the one-step approach [36]. This archive functionality enables researchers to return to the same cDNA pool months or years later to analyze newly discovered biomarkers without requiring additional original RNA material, a critical advantage when working with irreplaceable clinical samples [3]. Furthermore, the same cDNA synthesis reaction can serve as template for numerous parallel PCR amplifications, ensuring perfect comparability across multiple gene targets since all amplifications originate from an identical cDNA source [35] [11].

Superior Performance with Complex Samples

Two-step RT-qPCR demonstrates particular advantages when analyzing samples with inherent challenges, including low RNA quality, limited starting material, or requirements for high sensitivity detection. When RNA quality is compromised – a common scenario with clinical specimens – the two-step method allows for specialized reverse transcription conditions that can improve cDNA yield from degraded templates [35]. The independent reaction setup also enables concentration and purification of cDNA prior to PCR amplification, potentially enhancing detection sensitivity for low-abundance transcripts that serve as critical biomarkers in early cancer detection [35] [4].

Research has demonstrated that two-step protocols can achieve superior efficiency, sensitivity, and linearity compared to one-step methods. A comparative study evaluating RT-qPCR performance found that two-step reactions achieved efficiency of 100±1.5% and 99.7±0.95% on different PCR platforms, outperforming one-step approaches in these critical parameters [4]. This enhanced performance profile makes two-step RT-qPCR particularly suitable for absolute quantification applications requiring maximum accuracy, such as establishing diagnostic cut-off values for cancer biomarker panels [37] [33].

Comparative Analysis: One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR

Table 1: Methodological comparison between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR

| Parameter | One-Step RT-qPCR | Two-Step RT-qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Workflow | Combined RT and PCR in single tube | Separate RT and PCR reactions |

| Priming Options | Gene-specific primers only [35] [11] | Oligo(dT), random hexamers, gene-specific primers, or combinations [35] [38] |

| Hands-on Time | Minimal | Extended |

| Sample Throughput | Ideal for high-throughput analysis of few targets [35] | Suitable for low-to-medium throughput analysis of multiple targets |

| cDNA Archive | Not possible; must use original RNA for repeat analyses [35] [3] | Stable cDNA bank can be stored and reused [35] [36] |

| Optimization Flexibility | Limited; compromised conditions for both reactions [11] | Extensive; independent optimization of RT and PCR [11] [36] |

| Risk of Contamination | Lower due to closed-tube format [35] | Higher due to additional handling steps [35] [11] |

| Sensitivity | Potentially compromised by suboptimal combined conditions [4] [11] | Potentially higher due to optimized separate conditions [4] |

| Ideal Application | Repetitive analysis of limited targets where sample is abundant [35] [3] | Multiple target analysis from precious or limited samples [35] [36] |

Table 2: Performance characteristics of two-step RT-qPCR based on experimental data

| Performance Metric | Two-Step RT-qPCR Performance | Significance for Biomarker Research |

|---|---|---|

| Amplification Efficiency | 100±1.5% and 99.7±0.95% on different platforms [4] | Essential for accurate relative quantification of gene expression |

| Sensitivity (CT for lowest standard) | 33.2±0.5 and 32.5±0.7 [4] | Enables detection of low-abundance transcripts |

| Linearity (R² value) | 0.997±0.001 and 0.993±0.006 [4] | Critical for reliable standard curves across dilution series |

| Template Stability | cDNA stable at -20°C for long-term storage [36] | Allows creation of sample archives for future studies |

| Multi-Target Capacity | Dozens of genes from single cDNA synthesis [35] [3] | Maximizes information from precious clinical samples |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Two-Step RT-qPCR

Step 1: cDNA Synthesis Reaction

RNA Quality Assessment and Pretreatment

Prior to reverse transcription, assess RNA quality using appropriate methods such as spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio ~1.8-2.0) and microfluidic analysis (RIN >7 for high-quality samples) [5]. For samples potentially contaminated with genomic DNA, treat with DNase I following manufacturer's protocols [38]. Use 10 pg to 1 μg total RNA per 20 μL reverse transcription reaction, with higher inputs (100 ng to 1 μg) generally providing more robust results for low-abundance targets [4].

Reverse Transcription Reaction Setup

Prepare the following reaction mixture on ice:

- RNA template: 10 pg - 1 μg total RNA in nuclease-free water

- Primers: 25-50 ng random hexamers OR 0.5 μg oligo(dT)15-18 OR 10-50 pmol gene-specific primers [38]

- dNTP mix: 0.5-1 mM each dNTP

- Reaction buffer: 1X specific to reverse transcriptase

- Reverse transcriptase: 10-200 U (concentration dependent on enzyme)

- RNase inhibitor: 20-40 U (optional but recommended)

- Nuclease-free water: to final volume

Table 3: Primer selection guide for cDNA synthesis

| Primer Type | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ideal Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Hexamers | Binds at multiple positions along RNA transcripts | Amplifies all RNA species; good for transcripts with secondary structure; high cDNA yield [38] | cDNA made from all RNAs can dilute mRNA signal; produces truncated cDNA fragments [38] | Degraded RNA samples; analyzing multiple targets from single reaction |

| Oligo(dT) | Binds to poly(A) tail of mRNA | Generates full-length cDNA from polyadenylated mRNA; more specific to mRNA population [38] | Only amplifies genes with poly(A) tails; biased toward 3' end; inefficient with degraded RNA [38] | High-quality RNA; focusing on protein-coding genes |

| Gene-Specific | Binds to specific mRNA sequence | Specific cDNA pool; increased sensitivity for particular targets [38] | Synthesis limited to one gene of interest; not suitable for multiple targets [38] | Analyzing one or few specific targets |

Thermal Cycling Conditions for cDNA Synthesis

- Primer annealing: 25°C for 5-10 minutes (for random hexamers)

- cDNA elongation: 42-55°C for 30-60 minutes

- Enzyme inactivation: 70-85°C for 5-15 minutes

- Hold: 4°C (short-term) or -20°C (long-term storage)

The resulting cDNA can be used immediately in qPCR reactions or stored at -20°C for extended periods [36]. For qPCR, typically 1-5 μL of a 1:5 to 1:20 dilution of the cDNA synthesis reaction is used per 20-25 μL PCR reaction.

Step 2: Quantitative PCR Amplification

Reaction Setup

Prepare qPCR reactions in accordance with MIQE guidelines to ensure reproducibility [37]:

- cDNA template: 1-5 μL of diluted cDNA (optimize for each target)

- Forward and reverse primers: 100-500 nM each (optimize concentration)

- qPCR master mix: 1X final concentration

- SYBR Green dye or hydrolysis probes: according to manufacturer's instructions

- Nuclease-free water: to final volume

Primer Design Considerations

For cancer biomarker applications, primer design requires particular attention to ensure specificity and efficiency:

- Amplicon length: 85-125 bp for optimal amplification efficiency [5]

- Exon spanning: Design primers to span exon-exon junctions where possible, with one primer potentially crossing the actual exon-intron boundary to prevent amplification of genomic DNA [38]

- Sequence specificity: Conduct rigorous BLAST analysis to ensure primers do not amplify non-target sequences, particularly important for gene families with high homology [5]

- Single-nucleotide polymorphisms: Consider SNP locations when studying human samples to avoid primer binding sites containing common polymorphisms [5]

Thermal Cycling Conditions

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2-10 minutes

- Amplification (35-45 cycles):

- Denaturation: 95°C for 10-15 seconds

- Annealing: 55-65°C for 15-30 seconds (optimize temperature based on primer Tm)

- Extension: 72°C for 20-30 seconds (if two-step amplification not used)

- Melt curve analysis (for SYBR Green applications): 65°C to 95°C, increment 0.5°C

Essential Controls and Validation

Include the following controls in every two-step RT-qPCR experiment:

- No-template control (NTC): Contains all components except template cDNA to detect reagent contamination

- No-reverse transcription control (-RT): Contains RNA without reverse transcriptase to detect genomic DNA contamination [38]

- Positive control: Known expressed target to validate reaction efficiency

- Reference genes: Multiple validated reference genes for normalization [5] [37]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential reagents for two-step RT-qPCR workflow

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Reverse Transcriptases | Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) RT, Avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) RT [38] | Converts RNA to complementary DNA; enzyme choice affects yield, temperature tolerance, and fidelity |

| qPCR Master Mixes | SYBR Green master mixes, probe-based master mixes [35] | Provides optimized buffer, nucleotides, polymerase, and detection chemistry for quantitative PCR |

| Primers | Random hexamers, oligo(dT) primers, sequence-specific primers [35] [38] | Initiates cDNA synthesis; primer choice determines sequence representation and potential applications |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents | RNAlater, TRIzol [4] [33] | Preserves RNA integrity from sample collection through nucleic acid extraction |

| Quality Assessment Tools | Bioanalyzer, spectrophotometer, fluorometer [5] | Evaluates RNA quality, quantity, and purity to ensure only high-quality samples proceed to cDNA synthesis |

| DNase Treatment Kits | RNase-free DNase sets [38] | Removes contaminating genomic DNA that could lead to false positive amplification |

Application in Cancer Biomarker Research: A Case Study

The practical advantages of two-step RT-qPCR are exemplified in breast cancer biomarker research, where comprehensive molecular profiling from limited tissue samples is essential for diagnosis and treatment selection. A 2021 study directly compared established immunohistochemistry (IHC) methods with two-step RT-qPCR for detecting established breast cancer biomarkers (ER, PR, HER2, and Ki67) [33]. The researchers utilized the two-step approach to analyze 116 breast cancer cases with varying levels of diagnostic difficulty, demonstrating that the molecular method provided reliable quantification of all four critical biomarkers from a single cDNA synthesis reaction [33].

This study highlighted several key advantages of the two-step methodology in a clinical research context. The approach enabled multiple analyses from precious samples, as the same cDNA archive was used to quantify all four biomarkers plus reference genes. The method demonstrated superior objectivity compared to IHC, particularly for Ki67 assessment where visual counting variability presents significant challenges in clinical practice. Additionally, the two-step protocol facilitated retrospective analysis of archived samples, as the stable cDNA products could be re-tested when new questions emerged [33]. This case study illustrates how two-step RT-qPCR provides the flexibility, multi-target capability, and analytical consistency required for robust cancer biomarker validation in both research and potential diagnostic applications.

The two-step RT-qPCR workflow represents a methodologically superior approach for cancer biomarker research requiring multi-target analysis from precious or limited samples. By separating reverse transcription and PCR amplification into distinct optimized reactions, this method generates stable cDNA archives that support comprehensive gene expression profiling from a single RNA isolation [35] [36]. The flexibility in priming strategies, independent reaction optimization capabilities, and demonstrated performance advantages make two-step RT-qPCR particularly valuable for translational cancer research [4] [33].

As molecular diagnostics increasingly rely on multi-parameter biomarker signatures rather than single analytes, the capacity to analyze dozens of targets from minimal sample material becomes increasingly critical [37]. The two-step RT-qPCR protocol detailed in this application note provides researchers with a robust framework for maximizing the informational yield from valuable clinical specimens, thereby accelerating the development and validation of novel cancer biomarkers while preserving irreplaceable samples for future research applications.

In the realm of cancer biomarker research, reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) has become an indispensable technique for profiling gene expression, validating oncogenic signatures, and monitoring therapeutic responses. The accuracy and reliability of this method are fundamentally influenced by the initial reverse transcription (RT) step, where the choice of priming strategy directly impacts cDNA synthesis efficiency, target representation, and subsequent quantitative analysis [39] [38]. Within the overarching framework of one-step versus two-step RT-qPCR methodologies, primer selection emerges as a critical experimental variable requiring strategic consideration.

Two primary RT-qPCR approaches exist: one-step and two-step protocols. One-step RT-qPCR combines reverse transcription and PCR amplification in a single tube and buffer, exclusively using sequence-specific primers [11] [38]. This streamlined workflow reduces hands-on time and contamination risk, making it amenable to high-throughput applications. In contrast, two-step RT-qPCR physically separates the RT reaction from the PCR amplification, performing them in separate tubes with individually optimized conditions [11]. This flexible approach permits the use of oligo(dT) primers, random hexamers, gene-specific primers, or a combination thereof to generate a stable cDNA pool that can be archived for analyzing multiple targets from a single RNA sample [40]. The strategic selection of an appropriate priming method is therefore not merely a technical detail, but a foundational decision that governs experimental design, data quality, and biological interpretation in cancer research.

Characteristics of Priming Strategies

The three principal priming strategies—gene-specific, oligo(dT), and random hexamers—each possess distinct mechanisms, advantages, and limitations. Their performance characteristics are particularly relevant in cancer studies, where RNA integrity may be compromised in clinical samples, and target abundance can vary dramatically from highly expressed oncogenes to scarce regulatory non-coding RNAs.

Table 1: Comparison of Priming Methods for Reverse Transcription

| Primer Type | Structure & Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ideal Applications in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene-Specific Primers (GSP) | Custom-designed primers (18-25 nt) that anneal to a specific mRNA sequence of interest [39]. | - Maximizes sensitivity and specificity for targeted genes.- Essential for one-step RT-qPCR.- Ideal for detecting low-abundance transcripts (e.g., some transcription factors) [11] [38]. | - Synthesis limited to one pre-defined gene per reaction.- Requires prior knowledge of target sequence.- Not suitable for creating a universal cDNA archive [11]. | - Validating specific cancer biomarkers from a predefined gene set.- High-throughput screening of a few targets across many samples.- Quantifying splice variants when designed to junction sites. |

| Oligo(dT) Primers | Stretch of 12-18 thymine (T) residues that anneal to the 3' poly(A) tail of most eukaryotic mRNAs [39] [38]. | - Generates cDNA that is primarily representative of mRNA.- Produces full-length or near full-length cDNA transcripts.- Efficient when RNA is limited [38]. | - Biased towards the 3' end of transcripts.- Cannot reverse transcribe non-poly(A) RNAs (e.g., some non-coding RNAs).- Performance depends on RNA integrity; degraded samples yield biased 3' representation [38]. | - Gene expression profiling where 3' bias is acceptable.- Analyzing samples with high RNA integrity (e.g., cell lines).- Amplifying long mRNAs when full-length cDNA is desired. |

| Random Hexamers | Short, random sequences (6-9 nucleotides) that anneal at multiple points along all RNA transcripts [39] [38]. | - Anneals to all RNA species (rRNA, tRNA, mRNA, non-coding RNA).- Can prime degraded RNA samples effectively.- Generates cDNA along the entire transcript length, reducing 3' bias [38]. | - cDNA pool is diluted by non-mRNA sequences (rRNA, etc.).- May produce truncated cDNA fragments.- Lower specificity compared to GSP [38]. | - Working with partially degraded RNA (e.g., FFPE tissues).- Analyzing non-poly(A) targets.- Whole-transcriptome studies from a single cDNA pool. |

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental binding mechanisms of these three primer types to an mRNA template, highlighting their different initiation points for cDNA synthesis.

Diagram 1: Primer binding mechanisms for cDNA synthesis. GSP initiates synthesis from a specific internal site, Oligo(dT) from the 3' end, and Random Hexamers from multiple sites along the RNA transcript.

Strategic Primer Selection in One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR

The choice between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR protocols is often dictated by the research objectives, sample availability, and throughput requirements. This decision is intrinsically linked to the available priming strategies, creating distinct workflows with specific implications for cancer biomarker discovery and validation.

One-Step RT-qPCR: Streamlined for Targeted Quantification

In one-step RT-qPCR, the entire reaction from cDNA synthesis to PCR amplification occurs in a single tube with a unified buffer system. This method is inherently dependent on gene-specific primers for both reverse transcription and amplification [11] [40]. The closed-tube nature of this workflow minimizes pipetting steps, reduces cross-contamination risk, and enhances reproducibility, making it particularly suitable for high-throughput applications such as screening a large number of clinical samples for a predefined set of cancer biomarkers [11] [40].

A significant technical advantage of using gene-specific primers in one-step reactions is the potential for increased sensitivity for certain low-abundance targets. One study comparing one-step and two-step methodologies observed a 5-cycle lower detection threshold (indicating higher sensitivity) for the low-expression gene PolR2A when using the one-step approach [41]. However, a key limitation is that the reaction conditions represent a compromise between the optimal temperatures and buffer compositions for both reverse transcriptase and DNA polymerase enzymes, which can sometimes result in reduced efficiency compared to independently optimized two-step reactions [11].

Two-Step RT-qPCR: Flexible for Biomarker Discovery

The two-step method decouples cDNA synthesis from PCR amplification, offering unparalleled flexibility in priming strategies. Researchers can use oligo(dT) primers, random hexamers, gene-specific primers, or even mixtures (e.g., random hexamers and oligo(dT)) during the first-strand cDNA synthesis [40] [38]. This generates a comprehensive cDNA archive that can be stored and used for multiple subsequent qPCR assays, allowing for the analysis of numerous genes from a single, often precious, RNA sample [11].

This flexibility is crucial in exploratory cancer research. For instance, when working with formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor samples, which frequently contain degraded RNA, random hexamers are often the priming method of choice because they can bind throughout the fragmented transcript and generate cDNA more effectively than oligo(dT) primers [38]. Furthermore, separating the two steps allows for individual optimization of each reaction condition and the use of different reverse transcriptase enzymes, which can be selected for specific properties like higher thermal stability to overcome RNA secondary structures—a common challenge with certain transcript targets [40].

Table 2: Method Selection Guide: One-Step vs. Two-Step RT-qPCR

| Parameter | One-Step RT-qPCR | Two-Step RT-qPCR |

|---|---|---|

| Priming Strategy | Gene-specific primers only [11] [38]. | Oligo(dT), random hexamers, gene-specific primers, or a mixture [40]. |

| Workflow & Throughput | Faster, closed-tube; ideal for high-throughput analysis of a few targets [11] [40]. | More hands-on time; ideal for analyzing multiple targets from few samples [40]. |

| Sample Requirements | Requires fresh RNA aliquots to analyze new targets [40]. | A single cDNA synthesis reaction provides a stable template archive for future analyses of different targets [11]. |

| Optimization Potential | Compromised conditions for both RT and PCR; less sensitive for some targets [11]. | Independent optimization of RT and PCR steps; generally higher sensitivity and flexibility [11]. |

| Risk of Contamination | Lower risk due to minimal sample handling [11]. | Higher risk due to additional open-tube steps and pipetting [11]. |

| Ideal Scenario in Cancer Research | Rapid diagnostic screening of known biomarker panels (e.g., oncogene expression signatures). | Biomarker discovery, validating multiple candidate genes, or working with scarce patient-derived samples. |

The following workflow diagram contrasts the two main RT-qPCR methods and highlights the pivotal role of primer selection in each.

Diagram 2: Workflow comparison of one-step and two-step RT-qPCR. Primer selection is a key differentiator, with one-step restricted to gene-specific primers, while two-step offers multiple options.

Experimental Protocols for Primer Evaluation

Protocol: Validating Primer Specificity and Efficiency

Accurate quantification, especially for subtle expression changes in cancer pathways, depends on using highly specific and efficient primers.

Primer Design:

- Location: Design primers to span an exon-exon junction to prevent amplification of contaminating genomic DNA. The preferable amplicon size is 70-200 base pairs for optimal amplification efficiency [39] [42].

- Specifications: Aim for primers 18-25 nucleotides in length with a GC content of 40-60%. The melting temperatures (Tm) of the forward and reverse primers should be within 2°C of each other, ideally around 60-64°C [39] [42].