NGS for Microsatellite Instability Testing: A Comprehensive Review of Performance, Applications, and Clinical Validation

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for detecting microsatellite instability (MSI), a critical biomarker for immunotherapy response and Lynch syndrome identification.

NGS for Microsatellite Instability Testing: A Comprehensive Review of Performance, Applications, and Clinical Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for detecting microsatellite instability (MSI), a critical biomarker for immunotherapy response and Lynch syndrome identification. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biology of MSI, details the development and application of novel NGS algorithms and panels, addresses key troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and presents extensive validation data comparing NGS performance against traditional methods like immunohistochemistry (IHC) and PCR. The synthesis of recent large-scale studies offers crucial insights for implementing NGS-MSI in clinical research and therapeutic development.

The Biological and Clinical Foundation of Microsatellite Instability

The DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system is a critical guardian of genomic stability, responsible for correcting base-base mismatches and insertion-deletion loops (IDLs) that arise during DNA replication [1]. This sophisticated repair mechanism involves a coordinated complex of proteins including MutS homologs (MSH2, MSH3, MSH6) and MutL homologs (MLH1, PMS2, MLH3) that sequentially detect, excise, and repair mismatched DNA regions [1]. The MMR process begins with error recognition by MutS heterodimers—MutSα (MSH2-MSH6) for base mismatches and small IDLs, and MutSβ (MSH2-MSH3) for larger IDLs [1]. Following recognition, MutL complexes, particularly MutLα (MLH1-PMS2), are recruited to initiate the excision and repair process [1].

When the MMR system becomes compromised through genetic, epigenetic, or acquired factors, the resulting deficiency (dMMR) leads to the accumulation of replication errors, particularly in microsatellite regions [1]. Microsatellites, also known as short tandem repeats (STRs), consist of short repetitive DNA sequences (1-6 base pair units) distributed throughout the genome that are particularly prone to replication errors due to their repetitive structure [2] [3]. The failure to repair these errors results in microsatellite instability (MSI), characterized by length alterations in microsatellite regions that are detectable as novel alleles not present in corresponding germline DNA [4].

MSI has emerged as a crucial biomarker in oncology with significant implications for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection. Tumors exhibiting high levels of MSI (MSI-H) demonstrate markedly increased mutational burden and enhanced responsiveness to immune checkpoint inhibitors [5] [6]. This comprehensive review examines the molecular mechanisms underlying MMR deficiency, explores the genomic consequences of MSI, and provides an objective comparison of current methodologies for MSI detection with particular emphasis on next-generation sequencing (NGS) performance characteristics.

Molecular Mechanisms of Mismatch Repair Deficiency

The Canonical MMR Pathway

The human MMR system operates through a highly conserved mechanism that ensures replication fidelity by correcting mispaired bases and small insertion-deletion loops. The process begins with error recognition by MutS homolog complexes that scan newly synthesized DNA [1]. The MSH2-MSH6 (MutSα) heterodimer specializes in detecting single base-base mismatches and small IDLs (1-2 nucleotides), while MSH2-MSH3 (MutSβ) identifies larger IDLs (up to approximately 16 nucleotides) [1]. Upon binding to mismatched DNA, MutS complexes undergo conformational changes facilitated by ATP binding, forming a sliding clamp that recruits downstream repair effectors [1].

Following mismatch recognition, MutL homolog complexes are recruited to initiate the excision phase. The primary heterodimer MLH1-PMS2 (MutLα) interacts with the mismatch-bound MutS complex in an ATP-dependent manner and introduces single-strand nicks in the newly synthesized DNA strand [1]. The ability to distinguish the nascent strand from the parental template is critical for repair fidelity and is facilitated by pre-existing nicks in the lagging strand or through interactions with replication factors such as proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) on the leading strand [1].

The excision process is mediated by exonuclease 1 (EXO1), which removes the DNA segment containing the mismatch in a 5'→3' direction [1]. EXO1 activity is tightly regulated to prevent excessive DNA degradation. During excision, replication protein A (RPA) binds to the resulting single-stranded DNA to prevent secondary structure formation and protect against further degradation [1]. Following excision, DNA polymerase δ resynthesizes the removed segment using the undamaged strand as a template, with PCNA enhancing polymerase processivity. The final nick is sealed by DNA ligase I, completing the repair process [1].

Figure 1: Canonical Mismatch Repair Pathway. The MMR system corrects replication errors through sequential recognition, excision, and resynthesis steps. MutS complexes (MutSα/MutSβ) recognize mismatches, MutLα initiates repair, EXO1 excises erroneous DNA, and polymerase δ/ligase I complete resynthesis and sealing. PCNA facilitates strand discrimination and polymerase processivity [1].

Mechanisms of MMR Deficiency

MMR deficiency can arise through multiple mechanisms, including germline mutations, somatic alterations, and epigenetic silencing. Germline mutations in MMR genes (particularly MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2) are the hallmark of Lynch syndrome, which predisposes individuals to various cancers, most notably colorectal and endometrial carcinomas [1]. These inherited mutations follow Knudson's two-hit hypothesis, with one allele inactivated germline and the second somatically inactivated in tumor tissue [1].

Somatic alterations in MMR genes represent another pathway to MMR deficiency, occurring exclusively in tumor cells rather than the germline. These include point mutations, small insertions/deletions, and copy number alterations that disrupt gene function [1]. Somatic hypermethylation of the MLH1 promoter represents a common epigenetic mechanism of MMR deficiency, particularly in sporadic colorectal cancers [6]. This methylation silences MLH1 expression, leading to loss of MutLα function and subsequent MSI [6].

Emerging research has revealed non-canonical functions of MMR proteins beyond replication error correction. Recent studies indicate that MMR pathway components participate in oxidative DNA damage repair, with synthetic lethal interactions observed between MMR genes and polymerase beta (POLβ) or polymerase gamma (POLγ) [1]. The MSH2/POLβ synthetic lethality associates with accumulation of 8-oxo-G lesions in nuclear DNA, while MLH1/POLγ deficiency leads to buildup of mitochondrial 8-oxo-G lesions [1]. MMR proteins also contribute to DNA demethylation processes through long-patch base excision repair mechanisms, processing deamination products like dU•G, 5ohU•G, T•G, and 5hmU•G mismatches that may trigger active DNA demethylation [1].

Genomic Consequences of MMR Deficiency

Microsatellite Instability and Mutational Signatures

The primary consequence of MMR deficiency is microsatellite instability, which serves as a phenotypic marker of dMMR. Microsatellites are particularly vulnerable to replication errors due to their repetitive nature, which promotes DNA polymerase slippage during replication [3]. In MMR-proficient cells, these slippage errors are efficiently corrected, but in dMMR cells, they persist as insertion or deletion mutations, altering the length of microsatellite regions [2].

MSI has a profound impact on the cancer genome, generating a hypermutator phenotype characterized by significantly elevated mutation rates compared to MMR-proficient tumors [5]. This hypermutation extends beyond microsatellite regions to include single nucleotide variants and indels throughout the genome [5]. The resulting increased tumor mutational burden (TMB) contributes to enhanced immunogenicity, as neoantigens derived from somatic mutations are recognized by the immune system [5] [6].

MMR-deficient tumors exhibit distinctive mutational signatures dominated by insertions and deletions at mononucleotide repeats, particularly polyA/T tracts [2]. This signature reflects the preferential activity of MutSα on single-base mismatches and single-nucleotide IDLs [1]. Specific genes containing coding microsatellites become frequent mutation targets in MSI-H tumors, including ACVR2A, TGFBR2, BAX, MSH3, and MSH6 [2]. The ACVR2A gene, which contains a polyA tract in its coding sequence, demonstrates particularly high mutation frequency in MSI-H tumors, with one study reporting the chr2:g.148683686del (ACVR2A: c.1310del) mutation in 66.6% of MSI-H cases [2].

Biological and Clinical Implications

The genomic consequences of MMR deficiency have significant biological and clinical implications. MSI-H tumors exhibit altered responses to conventional chemotherapeutic agents, with numerous studies demonstrating increased sensitivity to various DNA-damaging drugs [5]. In colorectal cancer, MSI-H cell lines show significantly lower IC50 values for 5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan compared to microsatellite stable (MSS) cell lines [5]. This enhanced sensitivity appears mediated through downregulation of DNA damage response pathways, particularly non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) in MSI-H colorectal cancers [5].

From a therapeutic perspective, the high mutational burden of MSI-H tumors generates abundant neoantigens that make these cancers particularly susceptible to immune checkpoint blockade [5] [6]. Pembrolizumab received landmark FDA approval as the first tissue-agnostic cancer treatment for MSI-H/dMMR solid tumors, establishing MSI status as a predictive biomarker for immunotherapy response across multiple cancer types [6]. This approval underscores the clinical importance of accurate MSI status determination in treatment selection.

MSI also serves as a valuable diagnostic marker for Lynch syndrome identification. Detection of MSI in tumors should prompt genetic counseling and testing for germline MMR gene mutations, enabling targeted cancer surveillance and risk-reducing interventions for affected individuals and family members [6].

Methodologies for MSI Detection: Comparative Performance Analysis

Traditional MSI Detection Methods

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based fragment analysis have long been considered the gold standard methods for MSI detection in clinical diagnostics [2] [6]. IHC indirectly assesses MMR function by detecting nuclear expression of MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 proteins in tumor tissue [6]. Loss of expression of one or more MMR proteins suggests MMR deficiency and correlates strongly with MSI [6]. While IHC provides information about which specific MMR protein may be affected, it has limitations including susceptibility to interpretation errors due to heterogeneous staining and inability to detect non-truncating mutations that preserve antigenicity despite functional impairment [2].

PCR-based MSI testing directly evaluates microsatellite length alterations by comparing tumor DNA to matched normal DNA at specific microsatellite loci [2]. The most widely adopted approach uses a panel of five quasi-monomorphic mononucleotide repeats, which provides improved performance compared to the original Bethesda panel [2]. While PCR demonstrates high concordance with IHC (up to 97%), its application is primarily validated for colorectal cancers, and performance in other malignancies remains less established [2]. Additionally, PCR requires matched normal tissue for accurate interpretation and assesses only a limited number of loci [6].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional MSI Detection Methods

| Parameter | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | PCR-Based Fragment Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Detects MMR protein expression via antibodies | Detects length alterations in microsatellite loci |

| Target | MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2 proteins | 5-6 mononucleotide microsatellite loci |

| Advantages | Identifies affected MMR protein; no normal tissue required | Direct measurement of MSI; highly standardized |

| Limitations | Cannot detect non-truncating mutations; subjective interpretation | Requires matched normal tissue; limited loci |

| Concordance with Reference | ~97% with PCR [2] | Gold standard |

| Optimal Application | First-line screening; Lynch syndrome identification | Confirmatory testing; when IHC ambiguous |

Next-Generation Sequencing for MSI Detection

Next-generation sequencing has emerged as a comprehensive approach for MSI detection that offers several advantages over traditional methods [2] [6]. NGS-based MSI analysis evaluates dozens to hundreds of microsatellite loci simultaneously, providing broader genomic coverage than PCR-based methods [2]. This expanded coverage may improve sensitivity, particularly in non-colorectal cancers where traditional panels show reduced performance [2]. NGS platforms can simultaneously assess MSI status, tumor mutational burden, and specific genetic alterations in a single assay, maximizing information from limited tissue samples [6].

A key advantage of NGS-based MSI detection is the elimination of the requirement for matched normal tissue, as computational algorithms compare tumor microsatellite length distributions to reference models derived from stable samples [2] [7]. Multiple bioinformatics tools have been developed for NGS-based MSI determination, including MSIsensor, MSI-ColonCore, and MIAmS, which employ various algorithms to classify MS status based on length distribution patterns at microsatellite loci [2] [7].

Validation studies have demonstrated strong overall concordance between NGS and traditional methods. One large-scale retrospective analysis of 35,563 pan-cancer cases reported high performance for an NGS-based algorithm (MSIDRL) using 100 carefully selected microsatellite loci [2]. Another study evaluating Illumina's targeted NGS panels (TruSight Tumor 170 and TruSight Oncology 500) in 331 cancer patients found overall high concordance with PCR (AUC=0.922), though sensitivity was lower in colorectal cancers (AUC=0.867) [6].

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of NGS-Based MSI Detection Across Studies

| Study | NGS Method | Sample Size | Cancer Types | Concordance with Reference | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang et al. (2025) [2] | MSIDRL (100 loci) | 35,563 | Pan-cancer | High overall performance | Retrospective design |

| Illumina Panel Study (2025) [6] | TruSight Tumor 170/TSO500 | 331 | Multiple (71.2% CRC) | AUC=0.922 overall; AUC=0.867 for CRC | Lower sensitivity in CRC |

| NSCLC Study (2025) [7] | MIAmS (7 loci) | 1,547 | Lung cancer | 100% for dMMR cases | Rare MSI in lung cancer (0.39%) |

| MSKCC Study [2] | NGS-MSI | Multiple | Multiple | 99.4% (CRC/endometrial); 96.6% (other) | Literature reference |

Artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches are being integrated into NGS-based MSI detection to improve classification accuracy. The MIAmS tool employs two independent classifiers (MSINGS and SVCpairs) that use machine learning models of length distributions for stable and unstable microsatellites, combining predictions to determine MS status with high confidence [7]. These computational advances address the challenge of overlapping score distributions between MSI-H and MSS cases that can complicate interpretation, particularly in colorectal cancers [6].

Experimental Protocols for MSI Detection

NGS-Based MSI Detection Workflow

The protocol for NGS-based MSI detection begins with sample preparation and DNA extraction from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue [6] [7]. Specimens should contain sufficient tumor content (typically ≥30% tumor nuclei) as determined by pathological assessment [7]. DNA extraction is performed using standardized kits, such as the Maxwell RSC DNA FFPE Kit, followed by quantification using fluorometric methods like Qubit dsDNA High Sensitivity Assay [7].

Library preparation involves targeted enrichment of microsatellite loci and relevant cancer genes. For example, the Advanta Solid Tumor NGS Library Prep Assay enriches 7 microsatellite loci and 49 cancer-related genes (245 kb total) [7]. The process typically includes initial PCR amplification of target regions, purification with AMPure XP beads, followed by a second PCR to integrate sequencing adapters [7]. Libraries are then quantified, normalized, and sequenced on platforms such as Illumina NextSeq with 2×150 bp paired-end reads [7].

Bioinformatic analysis constitutes a critical component of NGS-based MSI detection. The process involves aligning sequencing reads to a reference genome, followed by microsatellite length analysis at designated loci [2] [7]. For each microsatellite locus, the algorithm calculates the proportion of reads deviating from the expected reference length, often defined by a "diacritical repeat length" (DRL) that maximizes separation between stable and unstable distributions [2]. The unstable locus count (ULC) or MSI score is then calculated by summing loci exceeding specific instability thresholds [2].

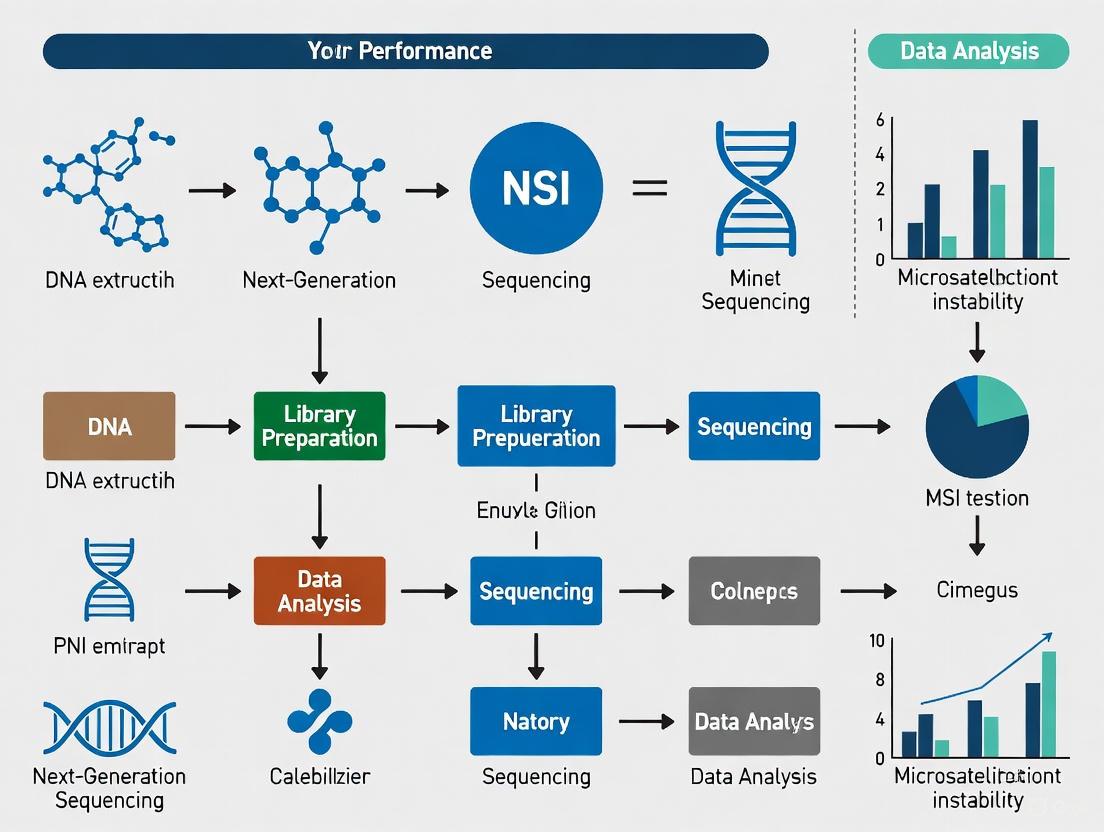

Figure 2: NGS-Based MSI Detection Workflow. The process begins with DNA extraction from FFPE tissue, followed by library preparation targeting microsatellite loci, sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis. MSI classification is based on unstable locus count (ULC) relative to established cutoffs [2] [6] [7].

PCR-Based MSI Reference Method

The reference PCR-based method for MSI detection follows established protocols using panels of mononucleotide markers. The Promega MSI Analysis System, which employs five quasi-monomorphic mononucleotide repeats (BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-24, and MONO-27), represents a widely adopted approach [2]. The protocol involves DNA extraction from paired tumor and normal tissue, PCR amplification with fluorescently labeled primers, capillary electrophoresis for fragment analysis, and size determination using genetic analyzers [2].

Instability is defined as the presence of novel peaks in the tumor DNA that deviate from the corresponding normal pattern at two or more loci (for the 5-marker panel) [2]. Samples are classified as MSI-H when ≥2 markers show instability, MSI-L (low instability) when only one marker shows instability, and MSS when no unstable markers are detected [2]. This method benefits from extensive validation and standardization but requires matched normal tissue for accurate interpretation [2].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for MSI Detection Studies

| Category | Specific Product/Kit | Manufacturer/Provider | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | Maxwell RSC DNA FFPE Kit | Promega | Optimal for degraded FFPE-derived DNA [7] |

| DNA Quantification | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Fluorometric quantification for NGS [7] |

| PCR-Based MSI | MSI Analysis System | Promega | Five mononucleotide markers; reference method [2] |

| NGS Library Prep | TruSight Oncology 500 | Illumina | Comprehensive profiling including MSI, TMB [6] |

| NGS Library Prep | Advanta Solid Tumor NGS | Fluidigm | 7 MS loci + 49 gene panel [7] |

| Sequencing | NextSeq 500/550 | Illumina | 2×150 bp for MSI analysis [7] |

| IHC Antibodies | Anti-MLH1 (clone ES05) | Agilent Technologies | MMR protein detection [7] |

| IHC Antibodies | Anti-MSH2 (clone FE11) | Agilent Technologies | MMR protein detection [7] |

| IHC Antibodies | Anti-MSH6 (clone EP49) | Agilent Technologies | MMR protein detection [7] |

| IHC Antibodies | Anti-PMS2 (clone EP51) | Agilent Technologies | MMR protein detection [7] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | MSIsensor | - | NGS-based MSI detection [2] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | MIAmS | - | Machine learning approach for MSI [7] |

The landscape of MSI detection has evolved significantly from traditional IHC and PCR methods to encompass sophisticated NGS-based approaches that provide comprehensive genomic profiling. While traditional methods maintain their role as established standards, NGS offers distinct advantages in terms of multiplexing capability, expanded genomic coverage, and elimination of the matched normal requirement. Performance validation across multiple studies demonstrates strong overall concordance between NGS and reference methods, though careful attention to platform-specific thresholds and analytical validation remains essential, particularly for non-colorectal malignancies.

The mechanistic understanding of MMR deficiency and its genomic consequences continues to expand, revealing novel biological insights with direct clinical relevance. As MSI solidifies its role as a predictive biomarker for immunotherapy response across diverse cancer types, the accurate and reliable detection of MSI status becomes increasingly critical in clinical decision-making. Future directions will likely focus on standardizing NGS-based MSI detection protocols, establishing consensus guidelines for interpretation, and further elucidating the non-canonical functions of MMR proteins in genome maintenance and cellular homeostasis.

MSI as a Pan-Cancer Predictive Biomarker for Immunotherapy

Microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) status has emerged as a critical pan-cancer biomarker for predicting response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), revolutionizing treatment across multiple cancer types. Microsatellites are short, repetitive DNA sequences prone to errors during replication, and MSI occurs when the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system is compromised, leading to accumulated insertion/deletion mutations throughout the genome [2] [6]. The MSI-H phenotype results from deficient MMR (dMMR), which can arise from germline mutations (as in Lynch syndrome), somatic alterations, or epigenetic changes such as MLH1 promoter hypermethylation [6] [8].

A recent comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials demonstrated that MSI-H status predicts exceptional benefit from immunotherapy across tumor types, with significantly improved progression-free survival (HR = 0.36, 95% CI 0.28-0.46; p < 0.0001) and overall survival (HR = 0.35, 95% CI 0.27-0.46; p < 0.00001) compared to chemotherapy [9]. This establishes MSI-H as a tumor-agnostic predictive biomarker supporting therapy selection regardless of cancer origin.

MSI Testing Methodologies: A Comparative Analysis

Multiple laboratory methods exist for determining MSI or MMR status, each with distinct technical approaches, strengths, and limitations. The following section provides a detailed comparison of these methodologies and their performance characteristics.

Comparison of MSI Detection Methods

Table 1: Comparison of primary methodologies for MSI/MMR status detection

| Method | Target | Mechanism | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) | Detects loss of nuclear protein expression | Cost-effective, widely available, identifies specific deficient protein [6] [8] | Indirect measure of MSI; ambiguous staining interpretation challenges [6] [10] |

| PCR-based MSI | 5-6 mononucleotide microsatellite loci | Fragment length analysis of microsatellite markers | Direct measure of MSI; established gold standard [6] [10] | Requires matched normal tissue; limited loci; primarily validated for colorectal cancer [2] [6] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Dozens to thousands of microsatellite loci | Sequencing-based analysis of length variations in repetitive regions | Comprehensive genomic profiling; no matched normal required; pan-cancer applicability [2] [6] [11] | Higher cost; lack of standardized thresholds across platforms [6] [10] |

Performance Metrics of NGS-Based MSI Detection

Multiple studies have evaluated the analytical performance of NGS-based MSI detection compared to traditional methods. The concordance rates vary depending on the specific NGS platform and tumor types evaluated.

Table 2: Analytical performance of NGS-based MSI detection across validation studies

| Study | NGS Platform | Reference Method | Sample Size | Concordance | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caris Life Sciences [12] | WES/WTS-based assay | IHC-MMR | 191,767 solid tumors | 99.69% agreement | Largest concordance study; led to FDA approval as CDx |

| FoundationOne CDx [11] | F1CDx (2,000+ loci) | PCR & IHC | 264 (PCR) 279 (IHC) | 97.7% (PCR) 97.8% (IHC) | FDA-approved companion diagnostic for pembrolizumab |

| Illumina Panels [6] [10] | TruSight Oncology 500 | PCR | 314 tumors | AUC = 0.922 | Recommended cut-off: MSI score ≥13.8%; borderline range: 8.7%-13.8% |

| MSIDRL Algorithm [2] | 733-gene panel | PCR | 35,563 pan-cancer cases | High concordance | Novel algorithm; identified 7 optimal loci for pan-cancer MSI detection |

| Multi-Assay Comparison [8] | VariantPlex, AVENIO, TSO500 | IHC | 139 tumors | Strong correlation | 12/139 (8.6%) MSI-H; 2 MSI-H cases showed retained MMR protein expression |

Biological Basis of MSI Testing

The following diagram illustrates the molecular pathway connecting MMR deficiency to microsatellite instability and its implications for immunotherapy response:

Experimental Protocols for NGS-Based MSI Detection

FoundationOne CDx Fraction-Based MSI Analysis

The FoundationOne CDx (F1CDx) assay employs a fraction-based MSI analysis that has received FDA approval as a companion diagnostic for pembrolizumab in MSI-H solid tumors [11]. The detailed methodology includes:

- Sample Requirements: Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue with at least 20% nucleated tumor cells and minimum 50 ng DNA input [11]

- Sequencing Method: Hybridization-based capture targeting 324 genes plus >2,000 microsatellite loci for comprehensive genomic profiling [11]

- MSI Calculation: The fraction of unstable loci is calculated as (number of unstable microsatellite loci) / (number of evaluable microsatellite loci) [11]

- Classification Thresholds:

- MSI-H: FB-MSI score ≥ 0.0124

- MSS: FB-MSI score ≤ 0.0041

- MSI-Equivocal: FB-MSI score >0.0041 and <0.0124 [11]

- Validation: Demonstrated 97.7% concordance with PCR and 97.8% with IHC across multiple solid tumor types [11]

MSIDRL Novel Algorithm Development

A large-scale retrospective study of 35,563 Chinese pan-cancer cases introduced MSIDRL, a novel NGS-based MSI detection algorithm [2]:

- Locus Selection: Initially selected 500 most robust noncoding MS loci from colorectal circulating tumor DNA whole-exome sequencing assays [2]

- Training Set: 105 pan-cancer FFPE samples with predefined MSI status (31 MSI-H and 74 MSI-L/MSS) by PCR [2]

- Algorithm Development: For each locus, defined a "diacritical repeat length" (DRL) that maximizes cumulative read count difference between MSI-H and MSS samples [2]

- Classification Metric: Unstable locus count (ULC) - the count of panel MS loci with binomial test p-values below established cutoffs [2]

- Optimal Threshold: Determined ULC cutoff of 11 based on bimodal distribution observed across 35,563 cases [2]

Illumina Panel Validation Protocol

A real-world evaluation of Illumina's targeted NGS panels established optimized workflows for routine molecular diagnostics [6] [10]:

- Cohort Design: 331 tumor samples representing various cancer types, with 314 meeting quality thresholds (minimum 40 usable MSI sites) [10]

- Reference Standard: Fluorescent multiplex PCR targeting six mononucleotide repeat markers [10]

- ROC Analysis: Demonstrated overall AUC of 0.922, with tumor-type variability (colorectal cancer: AUC = 0.867; prostate cancer: AUC = 1.00) [10]

- Optimal Cut-off: Recommended MSI score cut-off value of ≥13.8%, with borderline range (≥8.7% to <13.8%) requiring additional confirmation [10]

- TMB Integration: For borderline cases, incorporation of tumor mutational burden significantly improved diagnostic accuracy [10]

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key research reagents and platforms for NGS-based MSI detection

| Category | Specific Products/Assays | Primary Function | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| NGS Panels | FoundationOne CDx, TruSight Oncology 500, AVENIO CGP Kit | Comprehensive genomic profiling with MSI assessment | Therapy selection, clinical trial enrollment [11] [6] [8] |

| MSI Algorithms | MSIsensor, MSIDRL, Fraction-Based Analysis | Bioinformatic tools for MSI classification from NGS data | MSI status determination, biomarker discovery [2] [11] |

| Reference Materials | Promega MSI Analysis System v1.2, Bethesda Panel | Gold standard reference methods for validation | Assay validation, concordance testing [11] [6] |

| IHC Reagents | MLH1 (ES05), MSH2 (FE11), MSH6 (EP49), PMS2 (EP51) antibodies | Protein expression analysis for MMR deficiency | Orthogonal confirmation, mechanism determination [8] |

Clinical Validation and Predictive Value

Immunotherapy Response Correlations

The clinical validity of MSI-H as a predictive biomarker for immunotherapy response is well-established across multiple studies:

- Objective Response Rates: In a retrospective analysis of KEYNOTE-158 and KEYNOTE-164 trials, patients with MSI-H tumors determined by F1CDx demonstrated an objective response rate of 43.0% to pembrolizumab [11]

- Real-World Outcomes: Analysis of Caris' database of over 190,000 patients confirmed that dMMR/MSI-H tumors had significantly better overall and post-immunotherapy survival compared to MMR-proficient/MSI-Stable tumors [12]

- Pan-Cancer Efficacy: Subgroup analyses of the meta-analysis data highlighted significant PFS benefits across tumor types: colorectal (HR = 0.28), gastric (HR = 0.43), and endometrial cancers (HR = 0.34) [9]

Emerging Biomarkers and Complementary Approaches

While MSI-H remains a robust biomarker, research continues to refine prediction of immunotherapy response:

- Multi-Omic Algorithms: Tempus' Immune Profile Score (IPS) demonstrates potential for stratifying ICI outcomes in rare cancers and microsatellite stable colorectal cancer [13]

- Tumor Mutational Burden: Ultrahigh TMB (≥40 mutations/Mb) is associated with significantly improved survival outcomes in patients treated with ICIs across multiple cancer types [13]

- MAIT Cell Abundance: Mucosal-associated invariant T cells show varied distribution across solid tumors and correlate with clinical factors including MSI status [13]

The comprehensive analysis of MSI testing methodologies demonstrates that NGS-based approaches provide accurate, reliable detection of MSI-H status across diverse cancer types. The high concordance with traditional methods (generally >95%), combined with the ability to simultaneously assess multiple genomic biomarkers, positions NGS as a valuable tool for comprehensive molecular profiling in both clinical and research settings.

While standardization challenges remain for NGS-based MSI detection thresholds across platforms, the accumulating evidence supports its clinical utility for identifying patients likely to benefit from immunotherapy. The integration of MSI status with complementary biomarkers such as TMB and transcriptomic signatures represents the future of precision immuno-oncology, enabling more precise patient stratification and optimized treatment selection.

Microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) is a critical biomarker in oncology, resulting from a deficient DNA mismatch repair (dMMR) system. It leads to an accelerated accumulation of mutations in repetitive genomic sequences known as microsatellites. The clinical significance of MSI-H has expanded beyond its prognostic value to become a key predictor of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors across multiple cancer types. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the epidemiological landscape of MSI-H—its prevalence across different cancers and the methodologies for its detection—is fundamental to advancing precision oncology. This guide provides a comprehensive analysis of MSI-H prevalence data and objectively compares the performance of various detection technologies, with a specific focus on the evolving role of next-generation sequencing (NGS) in a pan-cancer context.

MSI-H Prevalence Across Major Cancer Types

The prevalence of MSI-H varies significantly across different cancer types. Table 1 consolidates data from large-scale studies to provide a comparative overview of MSI-H frequency in major cancers.

Table 1: MSI-H Prevalence Across Different Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | MSI-H Prevalence (%) | Data Source | Sample Size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endometrial Cancer | 16.85% - 31.2% | Real-world PCR study [14], NGS study [15] | 1,389 (PCR) |

| Colorectal Cancer | 3.78% - 15%* | Real-world PCR study [14], CRC resource [16] | 10,226 (PCR) |

| Gastric Cancer | 6.74% - 8.6% | Real-world PCR study [14], NGS study [15] | 1,929 (PCR) |

| Small Intestinal Cancer | 8.63% | Real-world PCR study [14] | Not specified |

| Duodenal Cancer | 5.60% | Real-world PCR study [14] | Not specified |

| Adenocortical Carcinoma | Notable (Precise % not stated) | TCGA/TARGET analysis [17] | 92 (NGS) |

| Cervical Cancer | Notable (Precise % not stated) | TCGA/TARGET analysis [17] | 305 (NGS) |

| Mesothelioma | Notable (Precise % not stated) | TCGA/TARGET analysis [17] | 83 (NGS) |

| Breast Cancer | 0.63% | Plasma-based NGS study [18] | 6,718 (NGS) |

| All Solid Tumors (Pan-Cancer) | 3.72% | Real-world PCR study [14] | 26,237 (PCR) |

| 39 Cancer Types (Pan-Cancer) | 3.8% | TCGA/TARGET analysis [17] | 11,139 (NGS) |

*The 15% figure for colorectal cancer is cited by a patient resource [16], while the 3.78% comes from a real-world study that likely tested primarily advanced-stage patients [14], highlighting how prevalence can vary by clinical context.

The data reveals that MSI-H is most frequently observed in endometrial, colorectal, and gastric cancers. A large-scale real-world study of 26,237 samples using PCR-based testing found MSI-H in 30 different cancer types, with the highest frequencies in endometrial (16.85%), small intestinal (8.63%), and gastric (6.74%) cancers [14]. Furthermore, a recent NGS-based study of 35,563 Chinese pan-cancer cases classified cancers into epidemiological clusters, identifying uterine, gastric, and bowel cancers as common cancers with high MSI-H prevalence, together contributing approximately 80% of all MSI-H cases [15] [2].

It is crucial for researchers to note that prevalence can differ within cancer subtypes. For instance, the same NGS study found a statistically significant difference in MSI-H prevalence between colon cancer (10.66%) and rectal cancer (2.19%) [15]. Demographic factors also play a role; the real-world PCR study found a significantly higher MSI-H frequency in female patients (4.75%) compared to males (2.62%), and a higher frequency in younger patients (<40 years) and older patients (≥80 years) [14].

Projected Epidemiological Trends

Understanding future epidemiological trends is vital for health system planning and resource allocation for targeted therapies. A statistical modelling study projected the prevalence of solid tumors with key pan-tumor biomarkers, including MSI, in Australia up to 2042 [19] [20].

The study estimated that the 5-year prevalence of individuals diagnosed with any solid cancer (regardless of biomarker status) will increase by 54.2%, from 438,346 in 2018 to 675,722 in 2042, driven largely by population growth and ageing [19]. Accordingly, the 5-year prevalence of individuals with advanced disease at diagnosis whose tumors exhibit MSI is projected to increase from 2,484 to 3,553 [19]. This represents about 2.3% of the 5-year prevalence of individuals with advanced disease at diagnosis, underscoring that while the absolute number is rising, MSI-H remains a biomarker present in a minority of advanced cancer patients [19] [20].

Detection Methodologies: A Technical Comparison

Accurate determination of MSI status is critical for therapeutic decision-making. The dominant methodologies are immunohistochemistry (IHC), polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and next-generation sequencing (NGS). Table 2 provides a technical comparison of these approaches.

Table 2: Comparison of MSI-H Detection Methodologies

| Feature | IHC (Immunohistochemistry) | PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) | NGS (Next-Generation Sequencing) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Indirect protein-level detection of MMR deficiency (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) [15] | Direct DNA-level detection of length shifts in microsatellite loci [15] | Direct DNA-level detection of length shifts and sequence variations in microsatellite loci [15] [21] |

| Typical Markers | 4 MMR proteins | 5-6 mononucleotide repeats (e.g., Promega panel) [15] [22] | Varies; from 7 [15] to 9 [21] to 100+ [15] loci |

| Tissue Requirements | Tumor tissue (normal not always required) | Paired tumor-normal tissue | Can use paired tumor-normal or tumor-only with sophisticated algorithms |

| Key Advantage | Low cost, widely available, identifies specific deficient protein | Established "gold standard," high concordance with IHC in CRC [15] | High sensitivity/specificity, pan-cancer applicability, integrates with other genomic profiling (TMB, SNVs) [15] [21] |

| Key Limitation | ~5-11% of MSI cases caused by non-truncating mutations can yield false negatives [15] | Primarily validated for colorectal cancer; performance in other cancers may be suboptimal [15] | Higher cost, computational complexity, bioinformatics expertise required |

| Reported Concordance with PCR | ~97% (in colorectal cancer) [15] | N/A | 99.4% in CRC/Endometrial; 96.6% in other cancers [15] |

The following workflow diagram illustrates the general process for developing and validating an NGS-based MSI assay, as exemplified by recent studies:

NGS-Based MSI Assay Development Workflow

Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis

This section details specific experimental workflows from key studies to provide a reference for researchers designing similar validation protocols.

Large-Scale NGS Validation Protocol

A 2024 study analyzing 35,563 pan-cancer cases developed a novel NGS-based MSI detector called MSIDRL [15] [2]. The experimental protocol was as follows:

- Locus Selection & Panel Design: Initially, 500 robust noncoding microsatellite loci were selected from circulating tumor DNA whole-exome sequencing assays. Capture probes were designed for these loci to create a prototype panel [15].

- Algorithm Training: A training set of 105 pan-cancer FFPE samples with pre-defined MSI status (31 MSI-H, 74 MSI-L/MSS) via PCR was sequenced with the prototype panel. For each locus, a "diacritical repeat length" (DRL) was defined as the repeat length that maximized the cumulative read count difference between MSI-H and MSI-L/MSS samples [15] [2].

- Statistical Classification: Reads for each locus in a sample were classified as "stable" (longer than DRL) or "unstable" (shorter than or equal to DRL). A binomial test was used to compare the sample's unstable read fraction against a background noise level calculated from MSI-L/MSS samples [15] [2].

- Final Panel Construction: The top 100 most sensitive loci were selected to form the final panel. The final MSI status was determined by counting the number of unstable loci (ULC), with a ULC ≥11 classifying a sample as MSI-H [15] [2].

Concordance Testing Protocol

A common method for validating new NGS-based MSI tests is to assess their concordance against established methods (PCR or IHC). A study describing a highly sensitive pan-cancer test using novel long mononucleotide repeat (LMR) markers provides a template for this validation [22]:

- Sample Cohort: 469 tumor samples across 20 cancer types, including 319 from patients with Lynch syndrome, were assembled [22].

- Reference Standard: dMMR status as determined by immunohistochemistry was used as the reference standard [22].

- Testing: All samples were tested with the novel LMR MSI Analysis System and the results were compared against both the reference standard and a established PCR method (the Promega pentaplex panel) [22].

- Metrics Calculation: Sensitivity for detecting dMMR was calculated as 99% for CRC and 96% for non-CRC tumors. The overall percent agreement between the LMR and Promega panels was 99% for CRC and 89% for non-CRC tumors [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

For scientists embarking on MSI-H research, selecting the appropriate tools is critical. The following table details key reagents and their functions as derived from the analyzed experimental protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for MSI-H Studies

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| FFPE Tumor Tissue | Source of tumor DNA; standard for clinical validation studies. | Used in large-scale NGS study [15] and LMR panel validation [22]. |

| Matched Normal Sample | Germline DNA control for distinguishing somatic mutations. | Blood or tumor-adjacent tissue used in NGS study with paired samples [21]. |

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolate high-quality DNA from tissue or blood samples. | QIAsymphony DNA Mini kit (Qiagen) [14]; QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen) [21]. |

| Targeted NGS Panel | Captures microsatellite loci and/or genes of interest for sequencing. | Custom 733-gene panel [15]; custom 2.2 Mb panel [21]; 74-gene cfDNA panel (Guardant360) [18]. |

| MSI Caller Software | Bioinformatics algorithm to analyze NGS data and determine MSI status. | MANTIS [17], MSIsensor [15], MSIDRL (custom algorithm) [15]. |

| IHC Antibodies | Detect expression of MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2). | IHC kits (OriGene) used for dMMR validation [21]. |

| PCR-Based MSI Kit | Gold standard method for validating NGS-based MSI calls. | MSI detection kit (Microread Genetics) [21]; Promega pentaplex MSI panel [22]. |

The epidemiology of MSI-H is characterized by its variable prevalence across cancer types, with the highest frequencies observed in endometrial, colorectal, and gastric cancers. The projected increase in the absolute number of patients with MSI-H tumors underscores the growing importance of this biomarker. While IHC and PCR remain foundational clinical methods, NGS-based detection is increasingly demonstrating high concordance with these standards, offering the significant advantages of pan-cancer applicability and integration with comprehensive genomic profiling. For researchers and drug developers, the choice of detection methodology must be guided by the specific research question, considering factors such as the cancer types under investigation, the required throughput, and the need for concomitant genomic data. The continued refinement of NGS protocols and algorithms, as evidenced by recent large-scale studies, promises to further enhance the sensitivity and specificity of MSI-H detection, thereby optimizing patient selection for immunotherapy.

Microsatellite instability (MSI) has emerged as a critical biomarker in clinical oncology, serving a dual role in identifying patients with Lynch syndrome—the most common hereditary colorectal cancer syndrome—and predicting response to immune checkpoint inhibitors across multiple cancer types [23] [6]. Microsatellites, short tandem repetitive DNA sequences distributed throughout the genome, are prone to errors during DNA replication that are normally corrected by the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system [2] [23]. Deficient MMR (dMMR) leads to the accumulation of insertion and deletion mutations at these sites, resulting in MSI [2] [6]. This phenomenon is most prevalent in endometrial, gastric, and colorectal cancers but occurs across numerous malignancies [2]. The clinical imperative for accurate MSI testing spans the entire patient journey, from cancer risk assessment and Lynch syndrome diagnosis to therapeutic selection, underscoring the need for robust, reliable detection methods [23] [6].

Methodological Landscape: Comparing MSI Detection Technologies

Established and Emerging Detection Platforms

Multiple technological platforms are currently employed for MSI detection in clinical and research settings, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and performance characteristics. The following table provides a comprehensive comparison of major MSI testing methodologies.

Table 1: Comparison of Major MSI Detection Methodologies

| Method | Mechanism of Detection | Common Markers/Panel | Typical Turnaround Time | Key Advantages | Reported Sensitivity (Range) | Reported Specificity (Range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Immunohistochemistry (IHC) | Protein expression loss of MMR proteins (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) | 4 MMR proteins | 1-2 days | Identifies affected protein; guides germline testing; low cost [23] | 66-100% [23] [24] | 90-100% [23] [24] |

| PCR-Based Methods | Fragment length analysis of fluorescent PCR products | 5-8 mononucleotide/ dinucleotide repeats (e.g., Promega OncoMate) [23] | 1-2 days | High concordance in colorectal cancer; established gold standard [23] | 75-100% [23] | 100% [23] |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Sequencing multiple microsatellite loci with algorithmic analysis | 7-100+ loci (e.g., MSIDRL: 100 loci) [2] | 3-5 days | Simultaneous assessment of multiple biomarkers; no normal tissue needed [6] | 89.3-98.4% [25] | 98.4-100% [25] |

| Integrated Cartridge Systems (Idylla) | Fully automated PCR amplification and melt-curve analysis | 7 monomorphic biomarkers (ACVR2A, BTBD7, DIDO1, etc.) [26] [27] | <3 hours [27] | Rapid results; minimal hands-on time (<3 minutes) [27] | 58-75% [23] | ~96% [24] |

| Deep Learning Approaches | AI analysis of H&E whole-slide images | Morphological features on routine pathology slides | Potentially minutes after digitization | No additional molecular testing; preserves tissue [28] | 94.6-98% [28] | 90.7-92% [28] |

Performance Characteristics Across Tumor Types

The diagnostic performance of MSI testing methods varies significantly across different cancer types, particularly between colorectal cancers and other malignancies.

Table 2: Tumor-Type Specific Performance of MSI Detection Methods

| Tumor Type | Method | Sample Size | Concordance with Reference | Area Under Curve (AUC) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer | NGS (Octaplex CaBio-MSID) | 303 | 98.4% Sensitivity, 98.4% Specificity [25] | - | Outperforms previously published methods [25] |

| Colorectal Cancer | PCR, Idylla, NGS | 28 | 100% Sensitivity, 100% Specificity [23] | 1.00 | For tumors with tumor cell percentages ≥30% [23] |

| Colorectal Cancer | NGS (Illumina Panels) | 201 | - | 0.867 [6] | Broader score variability observed [6] |

| Endometrial Cancer | NGS (Octaplex CaBio-MSID) | 88 | 89.3% Sensitivity, 100% Specificity [25] | - | - |

| Endometrial Cancer | PCR, Idylla, NGS | 21 | Sensitivity: 58% (Idylla) to 75% (NGS) [23] | 0.91-0.93 | Lower sensitivity for dMMR detection [23] |

| Endometrial Cancer | Idylla MSI Test | 126 | 66% Concordance with IHC; 75% with genomic status [24] | - | Performance improved with modified cut-off [24] |

| Pan-Cancer | NGS (MSIDRL) | 35,563 | - | - | Large-scale retrospective analysis; pan-cancer applicability [2] |

| Prostate Cancer | NGS (Illumina Panels) | 58 | 100% Concordance [6] | 1.00 | Perfect agreement with MSI-PCR [6] |

Technical Protocols: Experimental Methodologies for MSI Detection

Next-Generation Sequencing MSI Detection Workflow

The implementation of NGS for MSI detection involves a multi-step process that can be integrated into comprehensive genomic profiling. The MSIDRL algorithm exemplifies a novel NGS-based approach developed through large-scale validation [2]:

Panel Design and Training: Initially, 500 robust noncoding microsatellite loci were selected from colorectal circulating tumor DNA whole-exome sequencing assays. A prototype panel was designed and validated on 105 pan-cancer FFPE samples (31 MSI-H and 74 MSI-L/MSS) with predefined PCR status [2].

Diacritical Repeat Length Calculation: For each microsatellite locus, sequencing reads covering the entire repeat region were analyzed. The repeat length that maximized the cumulative read count difference between MSI-H and MSI-L/MSS samples was defined as the "diacritical repeat length" (DRL) [2].

Background Noise Estimation: Background noise for each locus was calculated as the ratio of unstable reads to total reads in MSI-L/MSS samples: $${B}{i}=\frac{\sum _{l}{{URC}}{{il}}}{\sum {l}({{SRC}}{{il}}+{{URC}}_{{il}})}\left(l\in \left{{\rm{MSI}}-{\rm{L}}/{\rm{MSS\; samples}}\right}\right)$$ where URC represents unstable read counts (reads with repeat length ≤ DRL) and SRC represents stable read counts (reads with repeat length > DRL) [2].

Final Panel Selection and Classification: The top 100 most sensitive MS loci were selected for the final panel, specifically excluding overlap with the 6 loci used in PCR-MSI. Sample classification is based on unstable locus count (ULC), with a ULC cutoff of 11 established through analysis of 35,563 cases [2].

PCR-Based MSI Testing Protocol

The traditional PCR-based approach remains a gold standard for MSI detection, particularly in colorectal cancers:

DNA Extraction: DNA is extracted from 10-µm thick sections of FFPE tumor tissue blocks, with macrodissection guided by hematoxylin and eosin staining when needed to ensure adequate tumor cell percentage (typically ≥30%) [23].

Multiplex PCR Amplification: Eight microsatellite loci are amplified, including five mononucleotide (BAT-25, BAT-26, NR21, NR24, and NR27) and three dinucleotide markers (D2S123, D17S250, and D18S55) selected based on published recommendations [23].

Fragment Analysis: PCR products are separated by capillary electrophoresis and analyzed using fluorescent detection systems. The resulting electrophoretograms are examined for peak patterns indicating instability [23].

Interpretation Criteria: Microsatellite instability at ≥2 loci is defined as MSI-high, instability at a single locus is defined as MSI-low, and no instability at any loci is defined as microsatellite stable (MSS) [23].

Biological Foundations: MMR Pathway and MSI Development

Understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying microsatellite instability requires examination of the DNA mismatch repair pathway and its relationship to Lynch syndrome.

The MMR system comprises several key proteins that form heterodimers: MLH1 partners with PMS2, and MSH2 partners with MSH6 [23]. Lynch syndrome is caused by heterozygous germline variants in these MMR genes, with approximately 15-40% of pathogenic variants occurring in MLH1, 20-40% in MSH2, 12-35% in MSH6, and 5-25% in PMS2 [29]. Large genomic rearrangements account for 10-20% of MLH1 pathogenic variants and 20-40% of MSH2 pathogenic variants [29]. Tumors exhibit MMR deficiency when the second allele is somatically inactivated, leading to genome-wide MSI [29].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for MSI Research

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for MSI Detection Studies

| Reagent/Kit | Manufacturer | Primary Function | Key Features | Regulatory Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SALSA MLPA Probemix P248 MLH1-MSH2 Confirmation | MRC Holland [29] | Detection of copy number variations in MLH1 and MSH2 genes | 49 MLPA probes (21 for MLH1, 17 for MSH2); confirms results from P003 MLH1/MSH2 | CE-IVD marked [29] |

| OncoMate MSI Dx Analysis System | Promega [30] | PCR-based MSI status evaluation in tumor tissue | FDA-approved companion diagnostic for colorectal and endometrial cancers | FDA Premarket Approval [30] |

| Idylla CDx MSI Test | Biocartis [26] [27] | Fully automated MSI detection on cartridge-based system | 7 monomorphic biomarkers; <3 minutes hands-on time, <3 hours results | FDA Premarket Approval [26] [27] |

| TruSight Tumor 170/Oncology 500 | Illumina [6] | Targeted NGS panels with integrated MSI detection | Comprehensive genomic profiling with MSI assessment without matched normal tissue | For Research Use Only |

| MSIDRL Panel | (Academic) [2] | NGS-based MSI detection with novel algorithm | 100 noncoding microsatellite loci; pan-cancer applicability | Research Use |

Clinical Validation and Concordance Studies

Large-Scale Performance Validation

Recent large-scale studies have provided critical insights into the real-world performance of various MSI detection methods. A retrospective analysis of 35,563 Chinese pan-cancer cases tested with an NGS-based MSI detector (MSIDRL) revealed a bimodal distribution of unstable locus counts, enabling clear separation of MSI-H and MSS cases with a ULC cutoff of 11 [2]. This study demonstrated that MSI-H prevalence varies significantly across cancer types, with particularly high rates in uterine (UTNP), gastric (GACA), and biliary tract (BWCA) cancers, while being rare in lung cancer (LUCA) despite its high prevalence [2].

A comprehensive comparison study of 49 tumor samples (28 colorectal and 21 endometrial adenocarcinomas) demonstrated that PCR, Idylla, and NGS achieved equivalent diagnostic performance for MSI detection, with area under the ROC curves of 0.91 for Idylla and PCR, and 0.93 for NGS [23]. Notably, all three molecular methods achieved 100% sensitivity and specificity in colorectal cancers with tumor cell percentages ≥30%, while showing reduced sensitivity in endometrial cancers (ranging from 58% for Idylla to 75% for NGS) [23].

Discordance Analysis and Resolution Strategies

Discordance between MSI testing methods presents clinical challenges, particularly in non-colorectal cancers. In endometrial cancers, the Idylla platform showed higher concordance with MMR genomic status (75%) than with IHC (66%), suggesting that molecular methods may more accurately reflect the underlying biology in certain contexts [24]. For NGS methods, establishing appropriate thresholds is critical; one study recommended an MSI score cut-off of ≥13.8% for identifying MSI-H tumors, with a borderline group (≥8.7% to <13.8%) where integration of tumor mutational burden significantly improves diagnostic accuracy [6].

The evolving landscape of MSI detection technologies offers multiple pathways for identifying Lynch syndrome and selecting patients for immunotherapy. While traditional IHC and PCR methods remain gold standards in specific cancer types, NGS-based approaches provide comprehensive genomic profiling with expanding pan-cancer utility. Emerging technologies like fully automated cartridge systems and deep learning applications promise to streamline testing workflows and reduce turnaround times. The choice of methodology depends on clinical context, tissue availability, laboratory infrastructure, and requisite ancillary genomic information. As MSI continues to gain importance as a predictive biomarker across multiple cancer types, understanding the performance characteristics, limitations, and appropriate implementation of each detection method becomes increasingly essential for precision oncology.

NGS-Based MSI Detection: Algorithms, Panels, and Workflow Integration

Microsatellite Instability (MSI) has emerged as a pivotal biomarker in oncology, transitioning from a diagnostic marker for Lynch syndrome to a pan-cancer predictive biomarker for response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy [15] [31]. Microsatellites, or short tandem repeats (STRs), are short repetitive DNA sequences (1-6 nucleotide units) ubiquitous throughout the human genome [15] [2]. When the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system is compromised, errors accumulate during DNA replication, leading to insertions or deletions at these microsatellite loci—a phenomenon recognized as MSI [31]. The detection of high-level MSI (MSI-H) is critically important as it identifies patients who may benefit significantly from immunotherapy, regardless of their cancer type [31] [6].

The evolution of MSI detection methodologies reflects major technological shifts in molecular pathology. For years, fragment analysis via PCR (PCR-MSI) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) for MMR proteins were the established gold standards [15] [6]. While these methods remain valuable, the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has introduced a paradigm shift, offering unprecedented scalability, multiplexing capability, and compatibility with comprehensive genomic profiling [31] [32]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these technologies, focusing on the core principles and performance data essential for research and diagnostic applications.

Traditional Methodologies: The Foundational Standards

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) with Fragment Analysis

The PCR-based method directly assesses the integrity of the MMR system by detecting length alterations in specific microsatellite regions.

- Core Principle: This technique utilizes fluorescently labeled primers to co-amplify a panel of microsatellite markers (typically 5-8 loci, such as the Bethesda or Promega panels) from both tumor and matched normal DNA. The amplified fragments are separated by capillary electrophoresis, and the resulting chromatograms are compared. Instability is declared when novel peaks, representing insertions or deletions, appear in the tumor sample that are absent in the normal sample [31] [6].

- Key Characteristics:

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

IHC provides an indirect assessment of MMR function by evaluating the expression of key proteins in the pathway.

- Core Principle: This method uses antibodies to detect the nuclear presence of the four core MMR proteins: MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2. Loss of nuclear expression in tumor cells, while internal control cells (e.g., stromal cells) retain staining, indicates a deficient MMR system (dMMR), which is highly correlated with MSI-H status [15] [6].

- Key Characteristics:

- Target: Protein expression, not DNA sequence.

- Advantage: Can pinpoint the specific affected MMR protein.

- Limitation: Approximately 5-11% of MSI-H samples are caused by non-truncating mutations that result in dysfunctional but antigenically intact proteins, leading to false-negative results [15].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional MSI/MMR Detection Methods

| Feature | PCR-Fragment Analysis | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) |

|---|---|---|

| Analytical Target | DNA length alterations at microsatellite loci | Protein expression of MMR genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) |

| Primary Output | Microsatellite Instability (MSI) status | Mismatch Repair (MMR) proficiency status |

| Key Advantage | Direct measurement of genomic instability | Identifies specific deficient protein |

| Key Limitation | Limited loci; requires matched normal | False negatives with non-truncating mutations [15] |

| Concordance | ~97% with IHC [15] | ~97% with PCR [15] |

The NGS Paradigm: Expanded Loci and Computational Analysis

Next-generation sequencing has redefined MSI detection by moving from a handful of markers to the simultaneous analysis of hundreds to thousands of microsatellite loci, which can be integrated into larger gene panels for a comprehensive genomic portrait of a tumor [15] [31].

Core Technical Principles of NGS-based MSI

NGS-based methods detect MSI by identifying shifts in the length distribution of microsatellite loci from sequencing data. The general workflow involves:

- Library Preparation & Target Capture: DNA is extracted, and sequencing libraries are prepared. Hybridization capture probes are used to enrich thousands of genomic regions, including hundreds of microsatellite loci [31].

- Sequencing: The enriched libraries are sequenced on a platform such as Illumina or PacBio.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Custom algorithms analyze the sequenced reads to quantify the level of instability.

Several sophisticated algorithms have been developed for this purpose, each with a unique approach to calculating an MSI score:

- MSIsensor: Quantifies the percentage of unstable microsatellite loci by comparing the length distribution of microsatellites between tumor and normal samples [31].

- MANTIS (Microsatellite Analysis for Normal-Tumor InStability): Calculates an instability score based on the average squared difference in allele fractions between tumor and normal pairs across a large set of loci [31].

- mSINGS (Microsatellite Instability by Next-Generation Sequencing): Determines the percentage of unstable loci in a tumor sample by comparing them to a baseline established from control samples, enabling tumor-only analysis [32].

- MSIDRL (Diacritical Repeat Length): A novel algorithm that defines a "diacritical repeat length" for each locus. It classifies reads as "stable" or "unstable" based on this threshold and uses a binomial test to determine instability, reporting an Unstable Locus Count (ULC) [15].

- MSIdetect: Employs a curve-fitting algorithm tailored for tumor-only data, modeling the impact of indel burden and tumor content on read coverage at a curated set of homopolymer regions [32].

Key Advantages of NGS-Based MSI Detection

- Expanded Loci Interrogation: NGS can evaluate hundreds to thousands of microsatellite loci, vastly improving statistical power and robustness compared to traditional 5-marker panels [15] [31].

- Pan-Cancer Applicability: While traditional PCR panels were optimized for colorectal cancer, NGS panels with broad locus coverage demonstrate high accuracy across diverse cancer types, including endometrial, gastric, and more [15] [32].

- Integration with Comprehensive Profiling: An NGS test can simultaneously determine MSI status, tumor mutational burden (TMB), single nucleotide variants (SNVs), and copy number variations (CNVs) from a single sample, optimizing tissue use and cost-efficiency [31] [6].

- Tumor-Only Analysis Capability: Advanced algorithms like mSINGS and MSIdetect allow for accurate MSI detection even without a matched normal sample, addressing a common clinical challenge [32].

Diagram 1: Core NGS-based MSI detection workflow, highlighting the key wet-lab and bioinformatics steps, and the decision point for using a matched normal sample.

Performance Comparison: NGS vs. Traditional Methods

Large-scale retrospective studies and real-world evaluations provide robust data on the performance of NGS-based MSI testing compared to the traditional gold standards.

Concordance with Traditional Methods

A large-scale study of 35,563 pan-cancer cases using an NGS-based method (MSIDRL) demonstrated the capability of NGS to accurately classify MSI status across a wide spectrum of malignancies [15]. Another real-world study of 314 tumors compared Illumina's targeted NGS panels (TruSight Tumor 170/Oncology 500) against PCR-MSI, showing an overall high concordance with an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.922 [6]. However, performance varies by cancer type, as seen in Table 2.

Table 2: Diagnostic Performance of NGS-based MSI Detection Across Cancer Types (vs. PCR-MSI)

| Cancer Type | Sample Size (n) | AUC | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Pan-Cancer | 314 | 0.922 | High concordance with reference PCR [6] |

| Prostate Cancer | 58 | 1.00 | Perfect agreement in this cohort [6] |

| Biliary Tract Cancer | 11 | 1.00 | Perfect agreement, though sample size is small [6] |

| Colorectal Cancer (CRC) | 201 | 0.867 | Good but lower accuracy; broader score variability [6] |

| Endometrial Cancer | 88* | 0.9926* | High accuracy; other studies note it can be a challenging type [32] [25] |

| Stomach Adenocarcinoma | 428* | 1.00* | Excellent performance in validation cohort [32] |

Note: Data for endometrial and stomach cancer marked with * are from a separate validation study using MSIdetect and TCGA WES data [32].

Addressing Discordance and Optimizing Panels

Despite high overall concordance, discrepancies between NGS and PCR do occur, particularly in non-colorectal cancers [15]. These can arise from:

- Tissue-of-Origin Effects: The baseline stability of microsatellites can vary between different healthy tissues [32].

- Ethnicity-Specific Polymorphisms: Natural variations in microsatellite length across populations can affect results, especially in tumor-only analyses [32].

- Panel Optimization: Many PCR panels were designed specifically for colorectal cancer, and their performance may be suboptimal in other cancer types [15] [32].

Research has shown that curating optimized panels of microsatellite loci can significantly improve pan-cancer performance. For instance, one study distilled a set of 7 highly sensitive MS loci suitable for pan-cancer MSI detection, while others have identified ~100 homopolymer regions that are minimally variable between tissues and individuals, enhancing the accuracy of tumor-only algorithms like MSIdetect [15] [32].

Comparing NGS Platforms: Illumina vs. PacBio

The choice of sequencing platform can significantly impact MSI detection accuracy, particularly in challenging homopolymer-rich regions.

- Illumina (Sequencing by Synthesis - SBS): The dominant short-read sequencing technology, known for its high throughput and scalability. It achieves high base-level accuracy, with the majority of bases exceeding Q30 (99.9% accuracy) [33].

- PacBio (Sequencing by Binding - SBB): A newer short-read technology that decouples nucleotide interrogation and incorporation. This reduces errors in repetitive regions and results in a higher theoretical accuracy, with scores up to Q40 (99.99% accuracy) [34] [35]. PacBio also offers long-read sequencing (HiFi), which is excellent for complex regions but is not the primary focus for targeted MSI panels.

Performance in Microsatellite Regions

Homopolymers are notoriously difficult for conventional SBS to sequence accurately due to a phenomenon known as "phasing." Preliminary data from the DOvEEgene project suggests that the PacBio Onso system (using SBB) identifies more unstable microsatellite loci in targeted panel regions than SBS methods [34]. This is attributed to reduced phasing issues and more accurate enumeration of homopolymer length, which is the fundamental basis for MSI detection [34].

A recent benchmark by the Genome in a Bottle consortium further demonstrated that the PacBio Onso system had the lowest mismatch rate among all short-read technologies evaluated on a matched tumor-normal pair [35]. This lower error rate is crucial for confidently detecting the subtle insertion/deletion signatures that define MSI.

Table 3: Comparison of NGS Platforms for MSI Detection

| Feature | Illumina (SBS) | PacBio (SBB - Onso) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Technology | Sequencing by Synthesis | Sequencing by Binding |

| Typical Read Length | Short-reads | Short-reads |

| Theoretical Accuracy | >Q30 (99.9%) [33] | Up to Q40 (99.99%) [34] |

| Throughput & Scalability | Very High | High |

| Key Advantage for MSI | High throughput, established workflows, lower cost | Superior accuracy in homopolymers, lower false positives [34] |

| Reported Benefit | Standard for most clinical NGS panels | Improved detection of unstable loci [34] |

Essential Protocols and Research Reagents

Detailed Experimental Protocol: NGS-based MSI Workflow

The following protocol is adapted from established methodologies for targeted sequencing-based MSI detection [31].

DNA Extraction:

- Use dedicated kits for your sample type (e.g., QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit for FFPE samples or QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit for blood).

- Quantify DNA using a fluorometer (Qubit) and assess quality/fragment size via electrophoresis (TapeStation).

Library Preparation:

- Fragment genomic DNA to a desired size (e.g., 200-300bp).

- Perform end-repair, A-tailing, and ligation of sequencing adapters.

- Clean up libraries using magnetic beads.

Target Enrichment:

- Hybridize the library to biotinylated probes designed to capture a panel of microsatellite loci (e.g., 100 loci) often combined with a larger gene panel (e.g., 1 Mb).

- Capture probe-bound fragments using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads.

- Wash away non-specific fragments and amplify the captured library via PCR.

Sequencing:

- Pool the enriched libraries.

- Sequence on an appropriate NGS platform (e.g., Illumina NextSeq, PacBio Onso) to achieve high coverage (e.g., >500x) over the target regions.

Bioinformatic Analysis (Using MANTIS as an example):

- Sequence Alignment: Map sequencing reads to the human reference genome (e.g., hg19) using an aligner like BWA-MEM.

- Microsatellite Locus Analysis: For each target microsatellite locus, count the number of reads supporting each observed allele length in both the tumor and matched normal samples.

- MSI Score Calculation (MANTIS): For each locus, calculate the divergence from the normal sample:

M = (Tumor_Allele_Fraction - Normal_Allele_Fraction)². The MANTIS score is the average of these squared differences across all analyzed loci. - Classification: A sample is typically classified as MSI-H if the MANTIS score exceeds a pre-defined threshold (e.g., 0.4) [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for NGS-based MSI Detection

| Item | Function / Application | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality DNA from FFPE tissue or blood. | QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit, QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit [31] |

| Library Prep Kit | Prepare sequencing libraries for NGS. | Illumina DNA Prep, KAPA HyperPrep |

| Target Capture Panels | Enrich microsatellite loci and cancer genes. | Custom-designed panels (e.g., 733-gene panel with 100 MS loci [15]), TruSight Oncology 500 [6] |

| NGS Platforms | Perform high-throughput sequencing. | Illumina NovaSeq/PacBio Onso [34] [33] |

| QC Instruments | Assess DNA/RNA quality, quantity, and library fragment size. | Agilent TapeStation, Qubit Fluorometer [31] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Analyze sequencing data and determine MSI status. | MANTIS [31], MSIsensor [31], MSIdetect [32], mSINGS [32] |

The transition from fragment analysis to NGS sequencing of microsatellite loci represents a significant advancement in molecular oncology. NGS offers a powerful, multiplexed approach that provides high accuracy, pan-cancer applicability, and the unique ability to integrate MSI status with other genomic biomarkers like TMB in a single assay.

While traditional methods retain their value in specific contexts, the expanded locus coverage, computational sophistication, and integrative potential of NGS make it the superior tool for research and clinical environments aiming for a comprehensive genomic profile. The emerging data from highly accurate sequencing platforms like PacBio Onso further suggests that the field will continue to evolve towards even greater precision in detecting this critical biomarker, ultimately helping to identify more patients who may benefit from targeted immunotherapies.

Microsatellite instability (MSI) has emerged as a critical biomarker in oncology, with significant implications for both prognosis and treatment selection, particularly for immune checkpoint inhibitors [2] [36]. Traditionally, MSI detection has relied on polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods or immunohistochemistry (IHC), with the former considered the gold standard for direct molecular assessment [36] [23]. However, the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized this landscape by enabling comprehensive genomic profiling that can simultaneously assess MSI status alongside other biomarkers like tumor mutational burden (TMB) and specific genetic alterations [6] [37]. This technological shift has spurred the development of novel computational algorithms designed specifically to interpret NGS data for MSI detection, aiming to overcome limitations of traditional methods while providing enhanced sensitivity, specificity, and efficiency [2] [38] [37].

The transition to NGS-based MSI detection presents unique computational challenges. Microsatellites are short, repetitive DNA sequences prone to replication errors when mismatch repair (MMR) systems are deficient [2]. Analyzing these regions through NGS requires specialized bioinformatics approaches to distinguish biologically significant instability from technical artifacts and background noise [38] [37]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of two innovative algorithmic strategies developed to address these challenges: MSIDRL, which employs a diacritical repeat length approach, and peak-finding methods that adapt principles from fragment analysis to NGS data.

Algorithmic Methodologies: Core Architectures and Workflows

MSIDRL: Diacritical Repeat Length Algorithm

The MSIDRL algorithm introduces a novel approach to MSI detection based on the concept of "diacritical repeat length" (DRL). Developed through large-scale retrospective analysis of 35,563 pan-cancer cases, this method addresses the need for robust NGS-based MSI detection across diverse cancer types [2].

The algorithm's development began with selecting 500 robust noncoding microsatellite loci from colorectal circulating tumor DNA whole-exome sequencing assays. After prototype panel design, researchers trained the algorithm on 105 pan-cancer FFPE samples with predefined MSI status (31 MSI-H and 74 MSI-L/MSS). For each microsatellite locus, the algorithm analyzes reads covering the entire repeat region, summing counts cumulatively by observed repeat length [2].

The core innovation lies in defining the DRL for each locus as the repeat length that maximizes the cumulative read count difference between MSI-H and MSI-L/MSS samples. This DRL serves as a critical threshold for classifying reads as "stable" (longer than DRL) or "unstable" (shorter than or equal to DRL). The algorithm then calculates background noise for each locus and performs binomial testing to determine instability with defined specificity (≥99.0%) and optimized sensitivity [2].

Table 1: Key Components of the MSIDRL Algorithm

| Component | Description | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Diacritical Repeat Length (DRL) | Repeat length maximizing read count difference between MSI-H and MSS samples | Serves as threshold for classifying stable/unstable reads |

| Background Noise Calculation | ∑URCil/∑(SRCil+URCil) for MSS samples | Establises baseline noise level for each locus |

| Binomial Testing | Tests null hypothesis bij > Bi | Determines statistical significance of instability |

| Unstable Locus Count (ULC) | Count of loci with p-values ≤ cutoffs | Primary metric for MSI classification |

The final implementation utilizes the top 100 most sensitive MS loci that do not overlap with traditional PCR-MSI loci. Classification is based on the Unstable Locus Count (ULC), with a cutoff of 11 established through pan-cancer analysis of bimodal ULC distribution patterns [2].

Peak-Finding Algorithms: MSIPeak and Related Methods

Peak-finding algorithms represent a different computational approach that adapts the visual assessment principles of traditional PCR-based fragment analysis to NGS data. These methods, including MSIPeak and the algorithm described by Zhou et al., focus on analyzing specific mononucleotide repeats like BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-24, and MONO-27 [38] [37].

The fundamental principle involves extracting read depth information from BAM files and generating histograms displaying counts of different fragment lengths for each marker. The algorithms then identify peaks in these distributions, with the underlying premise that the number and characteristics of these peaks reflect MSI status similar to PCR fragment analysis [37].

A critical challenge addressed by these algorithms is distinguishing true biological signals from technical noise inherent in NGS data. Without proper optimization, NGS data typically reveals more peaks than corresponding PCR analysis, potentially leading to false positives. To address this, developers implemented two key strategies: restricting peak height (eliminating peaks below a defined threshold) and data smoothing (reducing noise from sequencing errors) [37].

Table 2: Comparison of Peak-Finding Algorithm Variations

| Feature | MSIPeak | Frontiers Algorithm |

|---|---|---|

| Microsatellite Markers | BAT-25, BAT-26, NR-21, NR-24, MONO-27 | Six MSI markers (specifics not detailed) |

| Primary Output | Peak profiles and positive scores | Number of peaks resembling PCR results |

| Noise Reduction | Not specified | Smoothing and peak height threshold (0.2) |

| Validation Approach | Synthetic DNA samples with 1-, 2-, 3-bp deletions | Training set (9 samples), validation (101), test (68) |

| Reported Sensitivity | Higher than PCR for small deletions | 98.53% accuracy in test set |

The optimization process for these algorithms involves minimizing the difference between peak numbers detected in NGS data versus PCR results through hyperparameter tuning. The optimal configuration identified included smoothing with a peak height threshold of 0.2, achieving a minimal difference value of 0.66 [37].

Performance Benchmarking: Comparative Experimental Data

Validation Frameworks and Cohort Characteristics

The validation of novel MSI detection algorithms requires rigorous experimental design with appropriate reference standards. Both MSIDRL and peak-finding methods have undergone comprehensive validation, though with different cohort sizes and cancer type distributions.