NGS Concordance Between Tissue and Liquid Biopsy: A Comprehensive Review for Precision Oncology

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of next-generation sequencing (NGS) concordance between tissue and liquid biopsy across solid tumors, with emphasis on non-small cell lung cancer.

NGS Concordance Between Tissue and Liquid Biopsy: A Comprehensive Review for Precision Oncology

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of next-generation sequencing (NGS) concordance between tissue and liquid biopsy across solid tumors, with emphasis on non-small cell lung cancer. We examine the foundational principles of both testing modalities, methodological approaches for optimal implementation, strategies for troubleshooting discordant results, and analytical validation frameworks. For researchers and drug development professionals, we synthesize evidence from recent clinical studies demonstrating variable concordance rates (71.2%-95.7%) dependent on tumor stage, volume, and assay sensitivity. The review highlights clinical scenarios where liquid biopsy demonstrates particular utility, including when tissue is insufficient or for serial monitoring, while acknowledging limitations and optimization strategies for implementing complementary testing approaches in research and clinical development.

Fundamental Principles of Tissue and Liquid Biopsy in Precision Oncology

Tissue biopsy has long been the cornerstone of cancer diagnosis, treatment planning, and molecular profiling. However, its status as the "gold standard" is being re-evaluated in the face of significant challenges, particularly tumor spatial heterogeneity, which can limit the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the information it provides. This guide examines the technical limitations of tissue biopsy through the lens of modern oncology research, with a specific focus on implications for Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) concordance studies between tissue and liquid biopsy.

The Spatial Heterogeneity Problem in Tissue Biopsy

Spatial heterogeneity refers to the genetic, transcriptomic, and protein expression differences that exist between distinct geographical regions of the same tumor. This phenomenon poses a fundamental challenge to the representativeness of a standard tissue biopsy, which typically samples only a small portion of the entire tumor mass.

Experimental Evidence in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma

A 2025 study on esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) systematically quantified the impact of spatial heterogeneity on the assessment of PD-L1, a critical biomarker for immunotherapy.

- Experimental Protocol: Researchers sampled four distinct regions using endoscopic biopsy forceps from treatment-naïve ESCC patients and compared these with the largest longitudinal sections from completely resected tumors [1].

- Key Findings:

- Limited biopsy samples were insufficient to accurately determine the Combined Positive Score (CPS) for PD-L1 across the entire tumor [1].

- Spatial heterogeneity was reduced in tumors with sufficiently high CPS, suggesting that extreme negative or positive biomarker status may be more consistently assessed [1].

- A multi-region sampling approach (maximum CPS derived from three regions) provided a more accurate approximation of the bulk tumor's PD-L1 status than a single biopsy [1].

Transcriptomic Heterogeneity in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Research in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has revealed that spatial heterogeneity extends to the transcriptomic level, capturing crucial information about tumor evolution.

- Experimental Protocol: Scientists analyzed 172 multiregional transcriptomic profiles from 37 HCC patients, quantifying intra- and inter-tumor expression variation [2].

- Key Findings:

- Genes exhibiting high intra- and inter-tumoral expression variation were significantly enriched in prognostic information for HCC [2].

- This heterogeneity reflects a geospatially gradual transition from non-tumor region to tumor border and tumor core, as validated through multiregional single-cell transcriptomic profiling of 110,817 cells from 34 liver specimens [2].

Table 1: Impact of Spatial Heterogeneity on Biomarker Assessment

| Cancer Type | Biomarker | Effect of Heterogeneity | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (ESCC) | PD-L1 (CPS) | Single biopsy inaccurately represents whole-tumor status [1] | Multi-region sampling (max CPS from 3 regions) [1] |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) | Transcriptomic Signature | Single sample misses evolutionary information [2] | Multiregional analysis captures prognostic heterogeneity [2] |

Liquid Biopsy as a Complementary Approach

Liquid biopsy has emerged as a minimally invasive alternative that can overcome some limitations of tissue biopsy by capturing tumor-derived components from bodily fluids such as blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid [3] [4].

Key Analytes in Liquid Biopsy

- Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA): Short fragments of tumor-derived DNA in circulation, representing 0.1-1.0% of total cell-free DNA. ctDNA has a short half-life, allowing for real-time monitoring of tumor dynamics [3].

- Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs): Intact cells shed from primary and metastatic tumors into circulation. Isolating CTCs is challenging (approximately 1 CTC per 1 million leukocytes) but provides information about metastatic potential [3] [4].

- Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) and Tumor-Educated Platelets (TEPs): Other tumor-derived components that carry molecular information about the tumor [4].

Technical Platforms for Liquid Biopsy Analysis

- PCR-based methods (qPCR, ddPCR): Offer high sensitivity for detecting known mutations but limited multiplexing capability [5].

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Allows comprehensive profiling of multiple genes simultaneously, with higher sensitivity for ctDNA detection compared to ddPCR and qPCR in some settings [5].

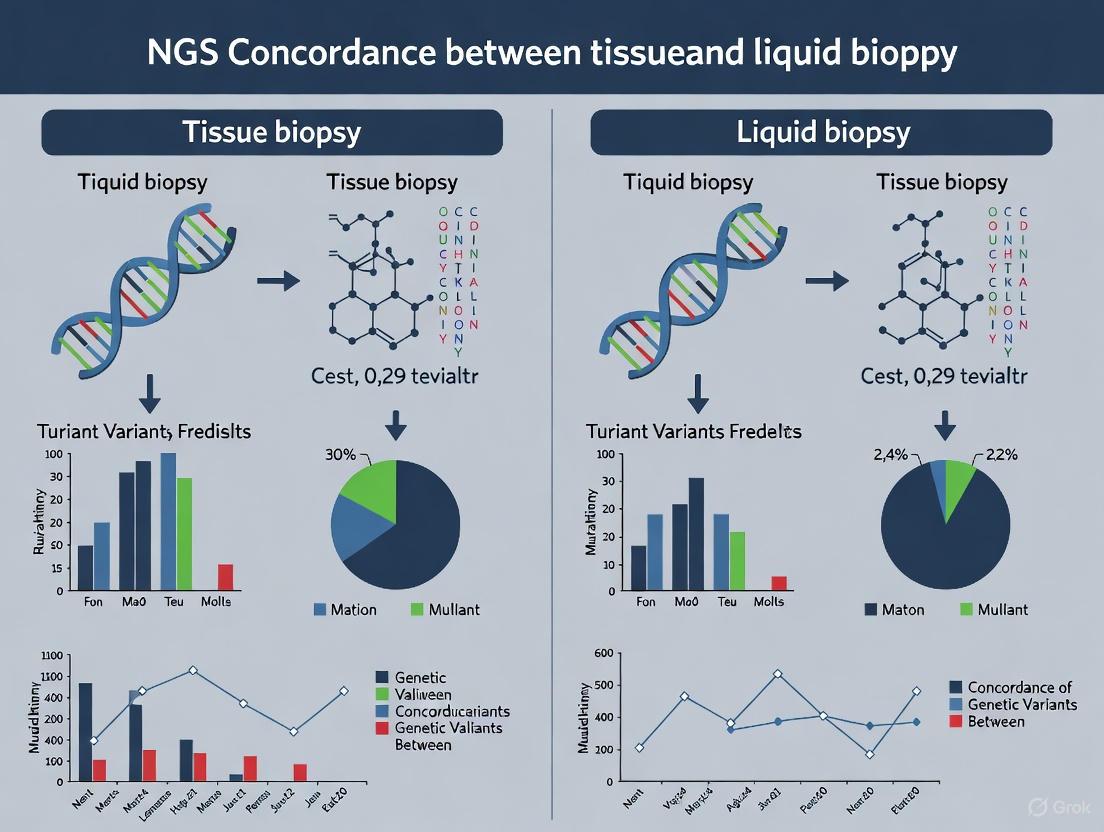

Diagram: Integrated Tissue and Liquid Biopsy Workflow for Comprehensive Tumor Profiling

NGS Concordance Between Tissue and Liquid Biopsy

The concordance between tissue and liquid biopsy NGS results has emerged as a critical factor in therapeutic decision-making, with implications for patient outcomes.

Insights from the ROME Trial

A 2025 analysis from the ROME Trial provided crucial insights into how concordance between tissue and liquid biopsy affects treatment outcomes.

- Experimental Protocol: The phase II multicenter study enrolled 1,794 patients with advanced solid tumors. NGS was performed on both tissue (FoundationOne CDx) and liquid biopsies (FoundationOne Liquid CDx). A centralized Molecular Tumor Board reviewed results to identify actionable alterations, with 400 patients randomized to tailored therapy (TT) or standard-of-care (SoC) [6].

- Concordance Definitions:

- Concordance: Detection of the same druggable alteration in both biopsy types.

- Discordance: Alteration detection in only one biopsy type [6].

- Key Findings:

- Concordance was present in 49% of cases.

- Alterations were detected exclusively in tissue (35%) or liquid (16%) biopsies [6].

- Patients in the concordant group receiving TT experienced significantly improved survival outcomes compared to SoC:

- Median OS: 11.05 vs. 7.70 months (HR 0.74)

- Median PFS: 4.93 vs. 2.80 months (HR 0.55) [6].

- The survival benefit of TT was less pronounced or absent in patients with discordant results [6].

Table 2: ROME Trial Outcomes by Biopsy Concordance Status

| Biopsy Concordance Group | Median Overall Survival (Months) | Median Progression-Free Survival (Months) | Benefit from Tailored Therapy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concordant (T+L) | 11.05 | 4.93 | Significant improvement [6] |

| Tissue-Only | 9.93 | 3.06 | Less pronounced benefit [6] |

| Liquid-Only | 4.05 | 2.07 | Minimal to no benefit [6] |

Platform-Specific Performance in HPV-Associated Cancers

A meta-analysis of 36 studies involving 2,986 patients with HPV-associated cancers compared the diagnostic performance of different detection platforms for circulating tumor HPV DNA (ctHPVDNA).

- Experimental Protocol: Systematic review and meta-analysis assessing diagnostic accuracy of ctHPVDNA detection across cancer anatomic sites, detection platforms, and blood components [5].

- Key Findings:

- Sensitivity was greatest with NGS, followed by ddPCR and then qPCR.

- Specificity was similar across platforms.

- Plasma NGS-based testing may be the most sensitive approach for ctHPVDNA overall [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Spatial Heterogeneity and Concordance Studies

| Research Tool | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| FoundationOne CDx | Tissue-based comprehensive genomic profiling | Used in ROME Trial for tissue NGS [6] |

| FoundationOne Liquid CDx | Blood-based comprehensive genomic profiling | Used in ROME Trial for liquid NGS [6] |

| CellSearch System | FDA-approved CTC enumeration and analysis | Immunomagnetic separation using anti-EpCAM antibodies [3] [4] |

| ScreenCell Filtration | Label-free CTC isolation by size | Microporous membrane filter based on cell size differences [4] |

| Multi-region Sampling Protocol | Assessment of spatial heterogeneity | Sampling of 3-4 distinct tumor regions recommended [1] |

| Ultracentrifugation Methods | Extracellular vesicle isolation | >50% of EV isolation methods use preparative ultracentrifugation [7] |

Diagram: Spatial Heterogeneity Challenge and Solution Approaches

The "gold standard" status of tissue biopsy must be contextualized within its fundamental limitation: the inability to consistently overcome tumor spatial heterogeneity with single-region sampling. The evidence demonstrates that multi-region tissue sampling provides a more comprehensive tumor profile, while liquid biopsy offers a complementary approach that captures tumor-wide heterogeneity.

Crucially, NGS concordance between tissue and liquid biopsy has emerged as a significant predictor of therapeutic outcomes, with patients showing concordant results deriving the greatest benefit from tailored therapies. For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings emphasize the need for integrated diagnostic approaches that leverage the strengths of both tissue and liquid biopsy to fully characterize the complex landscape of heterogeneous tumors. Future advancements will likely focus on standardized multi-region sampling protocols, refined liquid biopsy assays with enhanced sensitivity, and AI-driven integration of multi-modal data to overcome the challenges posed by spatial heterogeneity.

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) refers to fragmented DNA derived from tumor cells that circulates freely in the bloodstream alongside cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from healthy cells [8]. This biological phenomenon was first discovered in 1948, but its significance in oncology has only been fully appreciated in recent decades [3]. ctDNA originates from tumor cells through processes including apoptosis, necrosis, and active secretion, carrying tumor-specific genetic alterations that mirror the mutational profile of the tumor [8] [9]. These fragments typically measure 120-220 base pairs in length, with ctDNA fragments averaging approximately 140 bp [8]. The half-life of ctDNA in circulation is relatively short, estimated to be greater than 2 hours, enabling real-time monitoring of tumor dynamics [8].

In cancer patients, ctDNA typically constitutes less than 1% of total cfDNA, though this proportion can vary significantly based on tumor type, stage, and burden [3] [9]. The concentration of ctDNA in plasma is often elevated in cancer patients compared to healthy individuals, with studies demonstrating that plasma-free DNA levels were significantly higher in patients with advanced tumors [3]. This fundamental biological understanding provides the foundation for ctDNA's utility as a sensitive biomarker in oncology, enabling non-invasive access to tumor genetic information without the need for invasive tissue biopsies [10].

Table 1: Fundamental Biological Characteristics of cfDNA and ctDNA

| Characteristic | cfDNA | ctDNA |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Source | Apoptotic/necrotic normal cells [9] | Tumor cells (via necrosis, apoptosis, or secretion) [9] |

| Fragment Size | Predominantly 166 bp (nucleosomal) [9] | Shorter (<150 bp) + longer fragments [9] |

| Typical Concentration | 1-100 ng/mL plasma (healthy) [9] | Often <1% of total cfDNA [9] |

| Genetic Alterations | Wild-type [9] | Tumor-specific (e.g., EGFR, TP53) [9] |

| Half-Life | Variable | >2 hours [8] |

ctDNA Detection Technologies and Methodologies

Sample Collection and Pre-Analytical Processing

Proper sample collection and processing are critical for reliable ctDNA analysis due to the low abundance and fragmented nature of ctDNA. Blood collection for ctDNA analysis requires specialized approaches to preserve sample integrity. For ctDNA, blood is typically collected in specialized cell-stabilizing tubes such as Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT or Roche Cell-Free DNA collection tubes, which can maintain sample stability for up to 7 days at room temperature [11] [9] [12]. Following collection, plasma preparation involves a double-centrifugation protocol: an initial centrifugation at 1,600 × g to separate cellular components, followed by a second centrifugation of the supernatant at 16,000 × g to eliminate remaining cellular debris [9] [12]. This two-step process is essential to prevent contamination by genomic DNA from white blood cells, which could otherwise mask the rare ctDNA variants [9].

The extraction of ctDNA from plasma utilizes various methodologies, with magnetic bead-based systems demonstrating superior recovery of the short DNA fragments characteristic of ctDNA compared to traditional silica column methods [9]. Following extraction, ctDNA concentration is typically quantified using sensitive fluorescence-based methods such as the Qubit High Sensitivity dsDNA kit [12]. The entire pre-analytical workflow requires meticulous quality control measures, including assessment for hemolysis, which can significantly increase wild-type DNA background and compromise ctDNA detection sensitivity [9].

Detection Platforms and Analytical Techniques

Multiple technological platforms have been developed for ctDNA analysis, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and optimal applications. The primary detection methods include next-generation sequencing (NGS), droplet digital PCR (ddPCR), and denaturing capillary electrophoresis (DCE).

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) enables comprehensive profiling of multiple cancer-related genes simultaneously and can be implemented in either tumor-informed or tumor-uninformed approaches [13]. Tumor-informed NGS involves initial sequencing of tumor tissue to identify patient-specific mutations, which are then tracked in subsequent liquid biopsies [13]. This approach enhances sensitivity for detecting minimal residual disease (MRD) and monitoring treatment response. In contrast, tumor-uninformed NGS analyzes plasma samples without prior knowledge of tumor mutations, making it suitable for initial diagnosis and identifying actionable mutations [13]. Hybrid capture-based NGS methods typically achieve median deduplicated read depths of approximately 4,000x, enabling detection of variants at allele frequencies as low as 0.1% with 95% certainty when optimal DNA input (30-50 ng) is used [14] [12].

Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) represents an ultra-sensitive, mutation-driven approach that partitions individual DNA molecules into thousands of nanodroplets for absolute quantification of specific mutations [11]. This technology detects somatic alterations at very low frequencies (variant allele frequency of 0.01%) by dividing extracted DNA into approximately 20,000 droplets and calculating absolute quantities based on PCR-positive and negative droplets [11]. ddPCR offers significant cost advantages, with operational expenses 5-8.5-fold lower than NGS, making it particularly suitable for longitudinal monitoring of known mutations [11].

Denaturing Capillary Electrophoresis (DCE) provides a cost-effective alternative for mutation detection and monitoring, based on heteroduplex formation with subsequent electrophoretic separation to visualize mutant alleles amidst abundant wild-type DNA [13]. This method requires minimal input DNA (tens of picograms) and has been successfully applied to routine mutation detection in various solid tumors, including lung, colorectal, pancreatic, and brain cancers [13]. While less comprehensive than NGS, DCE offers a practical solution for monitoring specific mutations in tumor suppressor genes where mutations are dispersed across multiple exons, making it unsuitable for allele-specific PCR methods [13].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Major ctDNA Detection Technologies

| Technology | Detection Sensitivity | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Optimal DNA Input |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NGS (Large Panels) | 0.1% VAF (with optimal input) [14] | Comprehensive profiling, detects novel variants [14] | Higher cost, complex bioinformatics [14] [13] | 30-50 ng [14] |

| ddPCR | 0.01% VAF [11] | Ultra-sensitive, absolute quantification, cost-effective [11] | Limited to known mutations, low multiplexing capability [11] | Not specified |

| DCE | Not specified | Cost-effective, applicable to dispersed mutations [13] | Limited multiplexing, lower throughput [13] | Tens of pg [13] |

Concordance Between Liquid and Tissue Biopsy

The concordance between liquid and tissue biopsy represents a critical metric for establishing the clinical validity of ctDNA-based approaches. A 2025 analysis from the ROME Trial provided significant insights into how concordance impacts patient outcomes [6]. This phase II multicenter study enrolled 1,794 patients with advanced solid tumors and performed next-generation sequencing on both tissue and liquid biopsies using FoundationOne CDx and FoundationOne Liquid CDx assays [6]. Patients with actionable alterations were randomized to tailored therapy or standard-of-care treatment.

The study revealed that concordance between tissue and liquid biopsy was present in only 49% of cases, with alterations detected exclusively in tissue (35%) or liquid (16%) biopsies in the remaining cases [6]. Most importantly, patients in the concordant group who received tailored therapy demonstrated significantly improved survival outcomes, with median overall survival of 11.05 months versus 7.70 months in the standard-of-care group, and median progression-free survival of 4.93 months versus 2.80 months [6]. In contrast, the survival benefit of tailored therapy was less pronounced or absent in patients with discordant results, with the liquid-only group showing particularly poor outcomes (median OS: 4.05 months) [6].

Another study focusing on advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) reported a 71.2% concordance rate between standard-of-care tissue genotyping and ctDNA-NGS [12]. In 25.4% of cases, results were discordant but without direct therapeutic impact, while in 3.4% of patients, ctDNA-NGS missed an actionable driver mutation that would directly impact therapy selection [12]. This highlights both the potential and limitations of ctDNA-based genotyping, particularly in clinical contexts where identifying actionable drivers is critical for treatment decisions.

The performance of ctDNA assays is influenced by several technical and biological factors. A direct comparison of five ctDNA NGS assays revealed that detection sensitivity and reproducibility were 90% or higher when mutations were at 0.5% or 1.0% allele frequency with optimal DNA input (30 ng or 50 ng) [14]. However, performance decreased substantially when mutations were at 0.1% allele frequency and/or when lower genomic input (10 ng DNA) was used [14]. Notable differences in depth of coverage and background noise among assays profoundly impacted their performance characteristics, underscoring the importance of understanding these technical variables when selecting and implementing ctDNA testing platforms [14].

Experimental Protocols for ctDNA Analysis

NGS-Based ctDNA Analysis Protocol

The following protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for targeted NGS of ctDNA, based on methodologies described in recent literature [12]:

Sample Preparation and DNA Extraction:

- Collect peripheral blood in cell-stabilizing tubes (e.g., Roche Cell-Free DNA collection tubes)

- Process samples within five days of blood draw

- Perform double-centrifugation: 10 min at 1,600 × g followed by 10 min at 16,000 × g

- Isolate ctDNA from plasma using QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid kit

- Elute in 50 µL elution buffer

- Quantify DNA concentration using Qubit High Sensitivity dsDNA kit

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Use Twist Library Preparation Kit for library construction

- Incorporate xGEN dual index unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) adaptors

- Use custom probe set (e.g., 117 kb panel covering hotspot regions of 45 genes)

- Perform hybrid capture according to manufacturer's specifications

- Sequence on NovaSeq6000 system with 2 × 150 bp paired-end reads

- Achieve median deduplicated read depth of approximately 4,000×

Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Map reads to reference genome (Hg19)

- Perform deduplication using tools such as Fgbio

- Retain only reads with UMI family size of ≥ 2

- Perform variant detection using GATK Mutect2

- Apply stringent filtering:

- Exclude variants outside exons and splice site regions (-8/+8)

- Remove synonymous variants (unless in splice sites)

- Filter variants with population frequency > 0.1% in ExAC database

- Require minimum of five variant reads

- Exclude variants with exclusively alternative reads on forward or reverse strand

- Apply Mutect2 quality filter

- Require variant allele frequency (VAF) > 20 times higher than average VAF of healthy controls

- Manual curation using Alamut Visual Plus

- Classify variants using five-tier ACMG/AMP guidelines

ddPCR vs. NGS Comparison Protocol

A recent study directly compared ddPCR and NGS for ctDNA detection in localized rectal cancer, providing a robust experimental framework for technology comparison [11]:

Patient Cohort and Sample Collection:

- Development group: 41 patients with non-metastatic rectal cancer

- Validation group: 26 patients from SYNCOPE clinical trial (NCT04842006)

- Collect pre-therapy plasma and tumor samples

- Collect follow-up plasma samples 12 months after surgery

Tissue DNA Analysis:

- Perform primary tumor DNA sequencing using Ion AmpliSeq Cancer Hotspot Panel v2

- Cover >2800 COSMIC variants from 50 oncogene and tumor suppressor gene hotspots

- Achieve theoretical coverage of 99% in rectal patients

- Maintain average 2000× coverage with 154 bp amplicon length

ctDNA Detection with ddPCR:

- Design one to two predesigned probes based on highest VAF mutations in matched tumor

- Divide 2-9 μL extracted DNA into 20,000 droplets

- Calculate absolute quantity of targeted cfDNA based on PCR-positive/negative droplets

ctDNA Detection with NGS:

- Perform same panel sequencing as for primary tumors

- Optimize for ctDNA detection with lowered variant calling threshold

- Set detection threshold for somatic alterations at 0.01% VAF

Statistical Analysis:

- Use two-tailed Fisher's exact test for categorical variables

- Apply Shapiro-Wilk test for normality assessment

- Use Mann-Whitney test for non-normally distributed continuous variables

- Apply T-test for normally distributed continuous variables

- Use Kruskal-Wallis test for differences between cancer stages

Research Reagent Solutions for ctDNA Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for ctDNA Analysis

| Reagent/Kits | Primary Function | Key Features | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes | Cellular preservation and ctDNA stabilization | Prevents leukocyte lysis, enables room temperature storage | Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT [11], Roche Cell-Free DNA Collection Tubes [12] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality ctDNA from plasma | Optimized for short fragment recovery, magnetic bead technology | QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit [12], MagMAX kits [9] |

| Library Preparation Kits | NGS library construction from low-input ctDNA | Incorporates UMIs, compatible with fragmented DNA | Twist Library Preparation Kit [12] |

| Target Enrichment Panels | Hybrid capture of cancer-relevant genes | Comprehensive coverage, designed for ctDNA applications | Custom panels (e.g., 45-gene NSCLC panel) [12] |

| ddPCR Assays | Absolute quantification of specific mutations | Ultra-sensitive detection, rare allele detection | Bio-Rad ddPCR mutation assays [11] |

| Quality Control Kits | Assessment of DNA quantity and quality | High sensitivity, broad dynamic range | Qubit HS dsDNA Kit [12] |

ctDNA analysis represents a transformative approach in cancer management, providing a non-invasive means to access tumor genetic information throughout the disease course. The biological foundations of ctDNA, including its fragmentary nature, short half-life, and low abundance relative to total cfDNA, present both challenges and opportunities for analytical technologies. Current detection platforms, including NGS, ddPCR, and DCE, offer complementary strengths with NGS providing comprehensive profiling capability, ddPCR delivering ultra-sensitive quantification of known mutations, and DCE representing a cost-effective alternative for specific applications.

The concordance between liquid and tissue biopsies, while imperfect, provides valuable insights for clinical decision-making, with evidence suggesting that patients exhibiting concordant results derive greater benefit from tailored therapies. As technological advancements continue to enhance detection sensitivity and standardization, and as clinical validation accumulates across diverse cancer types and stages, ctDNA analysis is poised to play an increasingly central role in cancer diagnosis, monitoring, and personalized treatment selection.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has fundamentally transformed cancer care by enabling comprehensive genomic profiling of tumors, thereby facilitating precision oncology approaches. Clinical guidelines from leading oncology organizations provide critical frameworks for implementing NGS testing to match patients with optimal targeted therapies. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN), American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) have each developed recommendations to standardize the use of NGS technologies in clinical practice. These guidelines address key aspects including test selection, analytical validation, interpretation of results, and clinical actionability, while increasingly recognizing the importance of integrating both tissue and liquid biopsy approaches to overcome tumor heterogeneity and improve patient selection. The evolving landscape of NGS concordance between tissue and liquid biopsy represents a critical area of research with significant implications for therapeutic decision-making and clinical trial design [15] [16].

Comparative Analysis of Major Guideline Frameworks

NCCN (National Comprehensive Cancer Network) Guidelines

The NCCN guidelines provide tumor-specific recommendations for NGS testing across more than 60 cancer types. A distinctive feature of NCCN guidelines is their detailed, evidence-based categorization of treatment regimens into "preferred," "other recommended," and "useful in certain circumstances" classifications. Recent updates emphasize the critical role of NGS testing for identifying actionable biomarkers for targeted therapies. For example, the 2025 updates specify that "every patient with differentiated thyroid cancer who is going to get systemic therapy should have next-generation sequencing testing done" to identify potential targets like NTRK and RET gene fusions for specific inhibitors [17]. Similarly, guidelines for bladder cancer have been updated to include new biomarker-directed therapies such as fam-trastuzumab deruxtecan-nxki (T-DXd) for HER2-positive (IHC 3+) advanced disease [17].

The NCCN framework strongly supports the use of NGS to guide treatment selection in advanced cancers, particularly when standard therapy options have been exhausted. The guidelines acknowledge the growing importance of both tissue and liquid biopsy approaches, with recent updates reflecting an increasing number of biomarker-directed therapies across multiple tumor types [17].

ESMO (European Society for Medical Oncology) Frameworks

ESMO has developed two complementary tools for evaluating genomic targets and associated therapies: the ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of Molecular Targets (ESCAT) and the ESMO-Magnitude of Clinical Benefit Scale (ESMO-MCBS). The ESCAT framework categorizes genomic alterations into tiers of decreasing clinical evidence, with tier I representing alterations ready for routine clinical use [18]. The ESMO-MCBS grades the magnitude of clinical benefit (grades 1-5 for non-curative intent) based on efficacy, toxicity, and quality-of-life metrics [18].

A 2024 cross-sectional study analyzing NCCN-recommended genome-targeted therapies found that when these frameworks were applied, only 12% (32/267) of trials demonstrated substantial clinical benefit (ESMO-MCBS grades 4-5), while 45% (121/267) showed promising but unproven benefit (grade 3) [18]. This highlights ESMO's more conservative, benefit-centered approach compared to NCCN guidelines, with greater emphasis on overall survival and quality-of-life endpoints over surrogate markers.

ASCO (American Society of Clinical Oncology) Perspectives

While the search results provide less specific detail on ASCO's standalone NGS recommendations, ASCO has contributed significantly to molecular testing guidelines through its collaboration with the College of American Pathologists (CAP) and Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP). These joint guidelines establish standards for NGS test validation and bioinformatics pipelines to ensure analytical accuracy and clinical utility [15].

ASCO's approach typically emphasizes the integration of NGS testing within broader diagnostic and treatment pathways, focusing on clinical utility and patient outcomes. The organization has supported the development of quality assurance programs through partnerships with CAP and CLIA (Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments) to standardize NGS testing across laboratories [15].

Table 1: Comparison of Guideline Approaches to NGS Testing

| Aspect | NCCN | ESMO | ASCO/Collaborative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Tumor-specific testing recommendations | Clinical benefit assessment of targets/therapies | Test validation & quality assurance |

| Evidence Grading | Levels (1, 2A, 2B) & preference categories | ESCAT tiers & MCBS grades | Standards for analytical validation |

| Biopsy Approach | Increasing incorporation of both tissue & liquid | Evidence-based for clinical actionability | Emphasis on test validation for both types |

| Key Tools/Frameworks | Drug-specific recommendations with evidence levels | ESCAT for targets, MCBS for therapies | CAP/ASHI standards for laboratory testing |

Tissue and Liquid Biopsy Concordance: Evidence from the ROME Trial

Study Methodology and Experimental Protocol

The phase II ROME trial provides critical insights into the concordance between tissue and liquid biopsy for detecting actionable mutations. This multicenter study enrolled 1,794 patients with advanced solid tumors who had received second- or third-line treatment. The experimental protocol involved:

- Centralized NGS Testing: Both tissue and liquid biopsies were analyzed using FoundationOne CDx and FoundationOne Liquid CDx tests respectively [6] [16].

- Molecular Tumor Board Review: A centralized board reviewed results to identify actionable alterations [6].

- Patient Randomization: 400 patients with actionable alterations were randomized to receive either tailored therapy (TT) or standard of care (SoC) [6].

- Concordance Assessment: Concordance was defined as detection of the same druggable alteration in both biopsy types, while discordance indicated detection in only one type [6].

This robust methodology allowed for direct comparison of the clinical utility of tissue versus liquid biopsy approaches, with survival outcomes as primary endpoints.

Key Findings on Concordance Rates and Survival Outcomes

The ROME trial revealed a 49% concordance rate between tissue and liquid biopsies for detecting actionable alterations. Notably, alterations were detected exclusively in tissue in 35% of cases and exclusively in liquid biopsy in 16% of cases [6] [16]. This demonstrates the complementary nature of both approaches, with combined testing increasing the detection of actionable alterations by over 60% compared to either method alone [16].

Most significantly, patients with concordant findings who received tailored therapy showed substantially improved survival outcomes:

- Median Overall Survival: 11.05 months with TT vs. 7.70 months with SoC (HR 0.74; 95% CI: 0.51-1.07) [6]

- Median Progression-Free Survival: 4.93 months with TT vs. 2.80 months with SoC (HR 0.55; 95% CI: 0.40-0.76) [6]

In contrast, the survival benefit of tailored therapy was "less pronounced or absent" in patients with discordant results, with the liquid-biopsy-only group showing particularly poor outcomes (median OS: 4.05 months) [6]. These findings strongly suggest that concordance between biopsy methods may identify patients with disease biology more amenable to targeted interventions.

Table 2: ROME Trial Survival Outcomes by Biopsy Concordance Group

| Biopsy Group | Median Overall Survival (Months) | Median Progression-Free Survival (Months) | Tailored Therapy Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue + Liquid (Concordant) | 11.05 | 4.93 | Significant improvement |

| Tissue Only | 9.93 | 3.06 | Moderate improvement |

| Liquid Only | 4.05 | 2.07 | Minimal to no improvement |

| Standard of Care (Reference) | 7.70 | 2.80 | - |

Analytical Performance of NGS Platforms

Key Performance Metrics for Clinical NGS

Clinical application of NGS requires rigorous validation of analytical performance across multiple parameters:

- Depth of Coverage: Higher sequencing depth (e.g., 1,000×) improves sensitivity for detecting low-frequency variants [19].

- Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) Sensitivity: The limit of detection for VAF is critical, especially for liquid biopsy assays [20].

- Variant Types Detected: Comprehensive tests should identify single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions/deletions (indels), copy number variations (CNVs), and structural variants (SVs) [19].

- Genomic Signatures: Assessment of tumor mutational burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI) is increasingly important for immunotherapy selection [19].

Comparison of Commercial NGS Platforms

Commercially available NGS platforms demonstrate variable performance characteristics:

- FoundationOne CDx: Tissue-based test analyzing 324 genes with median turnaround time of 8 days; FDA-approved as companion diagnostic for 35+ targeted therapies [21].

- FoundationOne Liquid CDx: Blood-based test analyzing 324 genes with median turnaround time of 7 days; FDA-approved as companion diagnostic for 15+ targeted therapies [21].

- Northstar Select: Recently validated liquid biopsy assay demonstrating improved sensitivity with 95% limit of detection at 0.15% VAF for SNV/Indels, detecting 51% more pathogenic SNV/indels and 109% more CNVs compared to on-market CGP assays [20].

Technological advancements are particularly evident in liquid biopsy performance, with newer assays significantly reducing null reports (no actionable findings) by 45%, primarily through enhanced detection of variants below 0.5% VAF [20].

Technical Standards and Quality Control

Regulatory and Quality Assurance Frameworks

Multiple organizations have established standards for NGS testing in clinical laboratories:

- ACMG (American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics): Developed comprehensive guidelines covering interpretation and reporting of variants, with technical standards revised in 2021 to reflect technological advancements [15].

- CAP/CLIA: Establish standards for laboratory quality assurance, proficiency testing, and analytical validation [15].

- ISO Standards: ISO 15189 provides requirements for quality and competence in medical laboratories [15].

- GA4GH (Global Alliance for Genomics and Health): Develops international standards for data sharing and interoperability [15].

These frameworks address the entire NGS workflow from sample preparation to data analysis and interpretation, emphasizing the importance of analytical validation, bioinformatics pipeline standardization, and clinical reporting consistency.

NGS Workflow and Quality Control Metrics

The following diagram illustrates the key stages and quality control checkpoints in a comprehensive clinical NGS workflow:

Diagram 1: Clinical NGS Workflow with QC Checkpoints

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Concordance Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| FFPE Tissue Samples | Preserves tissue architecture and nucleic acids for histological correlation | Tissue-based NGS; gold standard reference [21] |

| Cell-Free DNA Collection Tubes | Stabilizes blood samples for ctDNA analysis | Liquid biopsy; enables centralized testing [21] |

| Hybrid Capture Probes | Enriches genomic regions of interest | Targeted sequencing; improves coverage of relevant genes [22] |

| Barcoded Adapters | Enables sample multiplexing | Cost reduction; batch processing of samples [22] |

| Reference Standard Materials | Provides known variants for validation | Assay performance assessment; quality control [15] |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Analyzes raw sequencing data | Variant calling; annotation; interpretation [22] |

The evolving guidelines from NCCN, ASCO, and ESMO reflect a growing consensus on the importance of comprehensive genomic profiling in advanced cancer, while demonstrating distinct approaches to evaluating evidence and clinical utility. The ROME trial data provides compelling evidence that integrating both tissue and liquid biopsy modalities significantly enhances the detection of actionable alterations and may identify patient populations most likely to benefit from tailored therapies. The observed survival benefit in concordant cases (11.05 vs. 7.70 months median OS) underscores the potential of combined profiling approaches to refine precision oncology strategies [6] [16].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these findings highlight the importance of considering both biopsy modalities in clinical trial design and biomarker strategy. Future directions should focus on standardizing concordance assessment, improving liquid biopsy sensitivity for low-shedding tumors, and developing integrated reporting frameworks that synthesize information from both tissue and liquid biopsies to optimize therapeutic decision-making.

In the validation of diagnostic tests, particularly when comparing new methodologies to established ones, Positive Percent Agreement (PPA) and Negative Percent Agreement (NPA) are the fundamental metrics used to quantify concordance. These statistics are essential in contexts where a perfect "gold standard" test may not exist [23] [24].

- Positive Percent Agreement (PPA) is the proportion of subjects known to be positive for a condition via a comparator method that are correctly identified as positive by the new test. It answers the question: "If a subject truly has the condition, how likely is the new test to detect it?" [25]. Its formula is identical to that of sensitivity: PPA = True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives) [25].

- Negative Percent Agreement (NPA) is the proportion of subjects known to be negative for a condition via a comparator method that are correctly identified as negative by the new test [25]. Its formula is identical to that of specificity: NPA = True Negatives / (True Negatives + False Positives) [25].

It is critical to distinguish PPA and NPA from sensitivity and specificity. While the calculations are identical, sensitivity and specificity require comparison to a known "Ground Truth" [24]. In contrast, PPA and NPA are used when the reference method itself is an imperfect comparator, acknowledging that some discrepancies may be due to inaccuracies in the reference rather than the new test [23] [24]. Using PPA/NPA terminology more accurately frames the results as a measure of agreement between two tests, rather than absolute accuracy [23].

Article 2: Quantitative Data on NGS Concordance in Liquid vs. Tissue Biopsy

The concordance between liquid biopsy (circulating tumor DNA, or ctDNA) and traditional tissue biopsy in Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) is a central focus in oncology research. The following tables summarize PPA and NPA from recent clinical studies across various cancer types, highlighting key influencing factors.

Table 1: Concordance Metrics for Key Genes and Alterations in Colorectal Cancer (CRC)

| Cancer Type | Genes/Alterations | Positive Percent Agreement (PPA) | Negative Percent Agreement (NPA) | Key Influencing Factor | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer (CRC) | All short variants (MSAF >0) | 79% (overall); 95% (<90 days); 100% (<30 days) | Not Reported | Time between tissue and liquid biopsy | [26] |

| Colorectal Cancer (CRC) | KRAS G12X | 93% | 100% | Time between biopsies (<270 days) | [26] |

| Colorectal Cancer (CRC) | KRAS, NRAS, BRAF short variants | 80% (overall); 90% (<270 days) | Not Reported | Time between biopsies | [26] |

Table 2: Concordance Metrics Across Different Cancer Types and Platforms

| Cancer Type | Genes/Alterations | Positive Percent Agreement (PPA) | Negative Percent Agreement (NPA) | Key Influencing Factor | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pan-Cancer (20+ types) | SNVs & Indels (clinically actionable genes) | >95% | Not Reported | Analytical performance of NGS assay | [27] |

| Pan-Cancer (20+ types) | Copy Number Alterations (CNAs) | 80-83% | Not Reported | Analytical performance of NGS assay | [27] |

| Metastatic Prostate Cancer | BRCA1/2 alterations | 50% | 85% | Tumor heterogeneity; long time between samples (median 132 weeks) | [28] |

| Stage IV NSCLC | EGFR, BRAF, KRAS, etc. | 99.20% | 99.46% | Cancer stage (late-stage shows higher concordance) | [29] |

| Stage III NSCLC | EGFR, BRAF, KRAS, etc. | 28.57% | 99.20% | Cancer stage (early-stage shows lower concordance) | [29] |

Article 3: Experimental Protocols for Concordance Studies

A standard protocol for determining PPA and NPA in NGS concordance studies involves a multi-step process from sample collection to bioinformatic analysis, with rigorous quality control at each stage.

Sample Collection and Processing

The typical workflow begins with the collection of matched tissue and blood samples. Tissue is often processed into Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) blocks, while blood samples are collected in specialized tubes (e.g., Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT) to preserve ctDNA [27] [29]. For liquid biopsy, plasma is separated via a two-step centrifugation protocol to isolate the cell-free DNA (cfDNA) fraction [29]. The amount of input cfDNA is a critical parameter, with studies often requiring a minimum of 20 ng for library preparation [29].

Next-Generation Sequencing and Bioinformatics

The isolated DNA undergoes library preparation, which is tailored for the specific NGS panel used (e.g., Illumina TruSight Oncology 500, FoundationACT, or PGDx elio) [30] [26] [27]. These panels use hybrid capture-based chemistry to enrich for target genes of clinical interest. Sequencing is then performed on platforms such as the Illumina NextSeq [27].

Following sequencing, a robust bioinformatic pipeline is employed. Key steps include:

- Read Alignment: Mapping raw sequencing reads to a human reference genome (e.g., GRCh37) [29].

- Variant Calling: Using specialized tools (e.g., GATK, VarScan) to identify somatic alterations [29].

- Filtering and Annotation: Removing potential germline variants and artifacts by cross-referencing population databases (e.g., dbSNP, ExAC) and annotating the functional impact of variants [27] [29].

Determining Tumor Fraction and Quality Control

For liquid biopsy, the Maximum Somatic Allele Frequency (MSAF) is a crucial metric, serving as a proxy for the ctDNA fraction in the sample [26]. Samples with an MSAF of 0 are considered to have no detectable ctDNA and are often excluded from PPA calculations [26]. Stringent quality control metrics are applied, including minimum coverage depth (e.g., >1400x mean effective depth) and thresholds for variant calling (e.g., a 0.2% variant allele frequency cutoff) [29].

Statistical Analysis

Finally, the identified alterations from the two sample types (e.g., liquid and tissue) are compared at the coordinate level for sequence variants and the gene level for copy number alterations [26]. The outcomes are tabulated into true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives, which are then used to calculate the final PPA and NPA values [26].

Article 4: Visualization of Factors Influencing Concordance

The concordance between liquid and tissue biopsies is not a fixed value but is influenced by a network of interrelated biological and technical factors. The following diagram maps these key factors and their logical relationships.

Article 5: The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful execution of NGS concordance studies requires a suite of specialized reagents, kits, and analytical tools. The following table details essential components of the research pipeline.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for NGS Concordance Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application | Relevant Context & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free DNA BCT Tubes (e.g., Streck) | Stabilizes blood samples for ctDNA analysis by preventing white blood cell lysis and genomic DNA contamination, crucial for preserving sample integrity between draw and processing. | Used in liquid biopsy workflows to ensure accurate representation of the in vivo ctDNA profile [29]. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate and purify high-quality DNA from different sample types (e.g., cfDNA from plasma, gDNA from FFPE tissue) for downstream sequencing. | A critical first step in all NGS protocols; specific kits are optimized for different sample matrices [29]. |

| Targeted NGS Panels (e.g., Illumina TSO 500, Guardant360, PGDx elio) | Hybrid capture-based kits designed to enrich for a predefined set of cancer-related genes, enabling comprehensive genomic profiling from limited input material. | Enable detection of SNVs, indels, CNVs, fusions, and genomic signatures like TMB and MSI [30] [27] [28]. |

| ddPCR Assays | Provides an orthogonal, highly sensitive method for validating specific mutations (e.g., in EGFR, KRAS) identified by NGS, confirming variant calls. | Used as a reference standard to validate the detection accuracy of NGS platforms in clinical samples [29]. |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines & Databases (e.g., GATK, Annovar, dbSNP, ExAC) | Software suites and population databases for sequence alignment, variant calling, filtering out germline polymorphisms, and functional annotation of somatic variants. | Essential for transforming raw sequencing data into clinically interpretable results [27] [29]. |

Article 6: Critical Factors Influencing Agreement

The observed PPA and NPA between liquid and tissue biopsies are not intrinsic properties of the tests alone but are heavily modulated by a confluence of factors.

Tumor Burden and Cancer Stage: The amount of ctDNA shed into the bloodstream, often estimated by the Maximum Somatic Allele Frequency (MSAF), is a primary driver of PPA [26]. Late-stage cancers (Stage IV) typically have a higher tumor burden and thus higher ctDNA levels, leading to PPA often exceeding 99% [29]. In contrast, early-stage cancers (Stage III) can have much lower or undetectable ctDNA, resulting in significantly lower PPA, sometimes as low as 28.57% [29].

Temporal and Spatial Heterogeneity: The time elapsed between tissue and liquid biopsy collection is a critical and well-documented factor [26] [28]. Genomic profiles evolve over time due to selective pressure from treatments or natural disease progression (temporal heterogeneity). One study showed PPA for all variants dropped from 100% (under 30 days) to 79% overall, and another in prostate cancer reported a low 50% PPA with a median 132-week interval [26] [28]. Furthermore, a single tissue biopsy may not capture the full genomic diversity of a patient's cancer (spatial heterogeneity), whereas liquid biopsy may provide a more comprehensive profile by sampling DNA from multiple tumor sites [28].

Assay Technical Performance: The sensitivity and design of the NGS assay itself directly impact concordance metrics. Key technical parameters include the sequencing depth (coverage), the variant allele frequency (VAF) cutoff for detection, and the panel's target capture efficiency [29]. For example, detecting copy number alterations (CNAs) and gene fusions is generally more challenging than detecting single nucleotide variants (SNVs), which is reflected in their lower PPA (80-83%) even in validated pan-cancer studies [27].

The Imperfect Gold Standard: A fundamental, often overlooked factor is that the tissue biopsy comparator itself is not a perfect "Ground Truth" [23]. Tissue samples can be affected by pre-analytical variables (e.g., fixation time in formalin, which degrades DNA) and intra-tumoral heterogeneity [30]. Therefore, some observed "discrepancies" where a variant is found in liquid but not tissue may represent true biological findings rather than liquid biopsy errors, a phenomenon underscored by the use of PPA/NPA terminology instead of sensitivity/specificity [23] [24] [28].

NGS Methodologies and Clinical Application Across Cancer Types

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has become the cornerstone of precision oncology, enabling comprehensive genomic profiling from both tissue and liquid biopsies. The concordance between these sample types is a critical focus of modern research, heavily influenced by the choice of assay design. This guide objectively compares the performance of three dominant NGS assay designs—targeted panels, hybrid capture, and unique molecular identifier (UMI) technologies—within the context of tissue and liquid biopsy concordance studies, providing the experimental data and methodologies needed for informed decision-making.

The pursuit of reliable liquid biopsy alternatives to tissue sequencing hinges on technological innovations that overcome the inherent challenges of analyzing circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), which is often present at ultra-low concentrations in a high background of normal DNA [31].

- Targeted Panels are designed to sequence a predefined set of genes known to be relevant to a specific disease area, such as cancer. The target enrichment can be achieved through either amplicon-based or hybrid capture-based methods [32].

- Hybrid Capture-Based Enrichment uses biotinylated oligonucleotide probes to "fish out" target DNA sequences from a genomic library prior to sequencing. This method is renowned for its comprehensive profiling capabilities and flexibility [32] [33].

- Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) Technologies involve tagging each original DNA molecule with a unique barcode before amplification. This allows bioinformatics pipelines to distinguish and group reads derived from the same original molecule, correcting for PCR and sequencing errors and significantly improving detection sensitivity [31].

Performance Comparison: Key Metrics for Liquid Biopsy

The table below summarizes the performance of these technologies based on recent experimental data, with a focus on metrics critical for liquid biopsy analysis and tissue concordance.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Key NGS Assay Designs

| Feature | Targeted Panels (Amplicon-Based) | Hybrid Capture-Based | Hybrid Capture with UMI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | Rapid, cost-effective profiling of known hotspots [32] | Broad genomic profiling, fusion detection [34] [32] | Ultra-sensitive liquid biopsy; low-frequency variant detection [31] |

| Limit of Detection (LoD) | ~2.9% VAF (for tissue) [32] | ~0.5% VAF (standard panels) [31] | ≤0.1% VAF [31] |

| Sensitivity in Liquid Biopsy | Lower; can miss >50% of alterations at 0.5% LoD [31] | Detects ~50% of alterations at 0.5% LoD [31] | Detects ~80% of alterations at 0.1% LoD [31] |

| Variant Type Flexibility | Best for SNVs/Indels; limited for fusions/CNVs [32] | Excellent for SNVs, Indels, CNVs, and fusions from a single workflow [34] | Excellent for SNVs, Indels; improved accuracy for CNVs/fusions |

| Input DNA Requirements | Can be low (e.g., ~50 ng for tissue) [32] | Requires sufficient input for library complexity (e.g., ≥60 ng for liquid biopsy) [31] | Critical; low input can make detection statistically improbable [31] |

| Key Experimental Validation | 98.23% sensitivity, 99.99% specificity in tissue [32] | 96.92% sensitivity for SNVs/Indels at 0.5% AF in reference standards [34] | Modeled >99% detection probability at 0.1% VAF with sufficient coverage [31] |

Experimental Protocols and Supporting Data

Validation of a Hybrid-Capture Pan-Cancer Tissue Panel

A 2025 study developed and validated a hybrid-capture oncopanel targeting 61 cancer-associated genes for use with solid tumour tissues [32].

- Objective: To create a sensitive, high-throughput, and rapid in-house NGS assay to reduce reliance on external labs with long turnaround times (TAT) [32].

- Methodology:

- Library Prep: Hybrid-capture-based target enrichment (Sophia Genetics) on an automated MGI SP-100RS system.

- Sequencing: MGI DNBSEQ-G50RS sequencer.

- Analysis: Variant calling with Sophia DDM software.

- Validation: 43 unique samples, including clinical tissues and reference standards, were sequenced. Performance was assessed against orthogonal methods [32].

- Key Results:

- The assay detected 794 mutations with 100% concordance for 92 known variants from other methods.

- It demonstrated a sensitivity of 98.23% and a specificity of 99.99%.

- The average turnaround time was reduced to 4 days, a significant improvement over the 3-week TAT from external providers [32].

Ultra-Broad Hybrid Capture for Pathogen Detection in Blood

Demonstrating the power of hybrid capture in liquid biopsy-type applications, a 2025 study applied it to the detection of pathogen-derived cell-free DNA (cfDNA) for diagnosing bloodstream infections [35].

- Objective: To overcome the limited detection sensitivity of traditional methods for pathogen cfDNA by developing an ultra-broad hybrid capture tNGS method [35].

- Methodology:

- Panel Design: An ultra-broad panel of 1872 pathogens with high-density probe tiling.

- Workflow: cfDNA was extracted from plasma, a pre-library was constructed, and then incubated with the capture probes.

- Sequencing: Performed on the Gene+ Seq-100 platform at a depth of 5 million reads.

- Validation: Retrospective testing on 208 suspected BSI patients, comparing tNGS to mNGS and conventional testing [35].

- Key Results:

- The diagnostic accuracy of tNGS (76.44%) was comparable to mNGS (75.00%) and significantly higher than conventional testing (45.67%).

- The method demonstrated effective enrichment and sensitivity, making it a cost-effective screening tool [35].

The Critical Role of UMIs in ctDNA Analysis

A 2025 review of the technical hurdles in ctDNA NGS analysis detailed the necessity of UMIs for achieving the sensitivity required for tissue-liquid biopsy concordance [31].

- Objective: To outline methodological improvements for ctDNA NGS, focusing on increasing sensitivity and reducing false positives [31].

- Methodology (Bioinformatic):

- UMI Deduplication: Reads from the same original DNA molecule (identified by their UMI) are grouped into a consensus, correcting for random errors.

- Variant Calling: The probability of detecting a variant is modeled as a function of sequencing depth and variant allele frequency (VAF). For example, achieving a 99% detection rate for a VAF of 0.1% requires an effective depth of coverage of approximately 10,000x after deduplication [31].

- Input DNA Consideration: The absolute number of mutant molecules is a key constraint. With a 0.1% ctDNA fraction, a 10 mL blood draw from a lung cancer patient may yield only ~8 mutant genome equivalents, making detection challenging without highly sensitive methods [31].

- Key Results & Proposal:

- Incorporating UMIs and optimizing bioinformatics pipelines are essential to lower the LoD from 0.5% to 0.1%.

- This improvement could increase the detection of true alterations in liquid biopsy from approximately 50% to 80%, thereby improving its concordance with tissue-based results [31].

Visualizing NGS Assay Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows for hybrid capture and UMI-based NGS assays, highlighting the steps that ensure high sensitivity and specificity.

Hybrid Capture Target Enrichment Workflow

UMI-Enhanced Variant Calling Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of these NGS assays requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key components used in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Tools for NGS Assay Development

| Item | Function | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Targeted Gene Panels | Predefined sets of probes/primers to enrich genomic regions of interest. | 61-gene pan-cancer panel [32]; 32-gene liquid biopsy panel (HP2) [34]. |

| Ultra-Broad Pathogen Panels | Extensive probe sets for detecting a wide range of microorganisms from complex samples. | Panel covering 1,872 pathogens for bloodstream infection detection [35]. |

| Hybrid Capture Probe Library | Biotinylated oligonucleotides that bind to target DNA for isolation. | 149,990-probe library targeting 663 viruses for zoonotic disease surveillance [33]. |

| Automated Library Prep System | Robotics to perform library construction, improving consistency and reducing human error. | MGI SP-100RS system used with hybrid capture kits [32]. |

| Unique Molecular Indices (UMIs) | Barcodes added to DNA molecules pre-amplification to track original molecules. | Used in ctDNA protocols to correct errors and enable ultra-deep sequencing [31]. |

| Reference Standard Materials | Samples with known mutations at defined allele frequencies for assay validation. | HD701 and other standards used for determining sensitivity and LoD [32]. |

| Specialized Analysis Software | Bioinformatics platforms for variant calling, annotation, and clinical interpretation. | Sophia DDM software with machine learning for variant analysis [32]. |

The choice of NGS assay design is a fundamental determinant in the success of tissue and liquid biopsy concordance research. Targeted panels offer a fast, cost-effective solution for profiling known genomic hotspots in tissue samples. Hybrid capture-based methods provide the broad profiling flexibility needed to detect diverse alteration types across large gene sets. For liquid biopsy, where sensitivity is paramount, the integration of UMI technologies with hybrid capture is not just an enhancement but a necessity, enabling the detection of ultra-low frequency variants and providing a more complete picture of the tumor genome.

The experimental data confirms that while each design has its place, the convergence towards hybrid capture with UMI deduplication represents the current state-of-the-art for maximizing liquid biopsy sensitivity, thereby strengthening its correlation with gold-standard tissue profiling and accelerating its adoption in precision oncology.

The integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS) into liquid biopsy represents a paradigm shift in cancer genomics, offering a minimally invasive method for tumor genotyping. However, this promise hinges on a critical technical challenge: establishing robust analytical sensitivity to detect low-frequency variants in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA). The low abundance of ctDNA, particularly in early-stage cancers or minimal residual disease, demands exceptional assay performance. This guide objectively compares the performance of NGS against other molecular techniques in detecting genomic alterations, with a specific focus on its concordance with traditional tissue biopsy—the historical gold standard in cancer diagnostics. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these performance characteristics, supported by experimental data and quality metrics, is fundamental for appropriate technology selection and data interpretation in clinical studies.

Experimental Protocols for Sensitivity and Concordance Assessment

Protocol 1: Establishing LOD and Tissue-Concordance in NSCLC

A seminal study on non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) provides a validated protocol for establishing analytical sensitivity and validating against tissue standards [29].

- Sample Collection: Collect 14-20 mL of peripheral blood from stage III/IV NSCLC patients in Cell-Free DNA BCT tubes (Streck). Process within one week via a two-step centrifugation protocol to isolate plasma from the buffy coat. Concurrently, collect matched FFPE tissue samples where available [29].

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Extract cfDNA from 4 mL of plasma using a specialized Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit, eluting in 52 µL of buffer. Isolate genomic DNA from FFPE tissue using the QIAamp FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen). Quantify cfDNA and gDNA using the Qubit dsDNA HS assay [29].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Construct NGS libraries from a minimum of 20 ng cfDNA using the USCI UgenDX Lung Cancer kit, a targeted 21-gene panel. Hybridize the libraries to the panel and sequence on USCISEQ-200 analyzers to generate 100 bp paired-end reads [29].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Trim raw reads with Trimmomatic and align to the GRCh37 reference genome using BWA. Mark duplicates with Picard. Perform variant calling with GATK and VarScan, followed by annotation with ANNOVAR. Apply a 0.2% variant allele frequency (VAF) cutoff with local depth >1000x and a mean effective depth of >1400x as key quality filters [29].

- Orthogonal Validation: Validate the NGS results for specific mutations in EGFR, BRAF, and KRAS using droplet digital PCR (ddPCR). The reaction mixture includes ddPCR Supermix, mutation-specific primers and probes (FAM/HEX labeled), and 20 ng of DNA template. Perform amplification and read on a QX200 Droplet Reader, analyzing data with QuantaSoft software [29].

Protocol 2: Comparative Analysis of HPV Detection Methods

A direct comparison of NGS, ddPCR, and qPCR for detecting HPV in oropharyngeal cancer illustrates a protocol for benchmarking NGS against other PCR-based techniques [36].

- Sample Types: Utilize plasma and oral rinse samples from patients with HPV16-positive oropharyngeal cancer (HPV16-OPC) [36].

- Method Comparison: Process samples in parallel using:

- NGS: Specific library prep and sequencing methodology for HPV detection.

- ddPCR: Partition samples into nanodroplets for absolute quantification without a standard curve.

- qPCR: Use standard curve-based quantification with fluorescent probes.

- Sensitivity Calculation: Calculate and compare the sensitivity of each method for detecting HPV16 DNA in the different sample matrices [36].

Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Platforms

The analytical sensitivity of a technology defines its lowest detectable limit of a mutant allele in a wild-type background, a parameter critical for ctDNA analysis where VAF can be very low.

Sensitivity and Limit of Detection (LOD)

Table 1: Comparative Analytical Sensitivity of Molecular Detection Methods

| Method | Typical Lower Limit of Detection (Mutant Allele Frequency) | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantitative PCR (qPCR) | ~10% [37] | Fast, cost-effective, accessible equipment [38] | Limited throughput, detects known sequences only [38] |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) | <0.1% [37] | High sensitivity, absolute quantification without standard curves | Limited to known targets, lower multiplexing capability |

| Targeted NGS | <1% (can reach 0.2% with optimized protocols) [29] [37] | High discovery power, high multiplexing, detects novel variants [38] | Higher cost for simple targets, complex data analysis [38] |

| Advanced NGS (with barcoding) | <0.1% [37] | Ultra-high sensitivity, reduced sequencing errors | Increased cost and protocol complexity |

NGS demonstrates a clear advantage in sensitivity over traditional qPCR. While dPCR can achieve similar or slightly better LOD for specific known mutations, NGS provides this sensitivity across hundreds to thousands of genomic regions simultaneously [38]. The establishment of a 0.2% VAF cutoff with high depth of coverage (>1400x) in the NSCLC study exemplifies the rigorous parameters required for reliable ctDNA detection in clinical research [29].

Tissue-Concordance and Stage-Dependent Performance

A critical validation of liquid biopsy NGS is its concordance with tissue-based genotyping. Data from a large cohort study reveals that concordance is highly dependent on disease stage.

Table 2: Tissue-Plasma Concordance Rates in Stage III/IV NSCLC [29]

| Clinical Stage | Positive Percentage Agreement (PPA) | Negative Percentage Agreement (NPA) |

|---|---|---|

| Stage III | 28.57% (2/7) | 99.20% (124/125) |

| Stage IV | 99.20% (124/125) | 99.46% (183/184) |

This data highlights a crucial finding: while the NPA remains excellent across stages, the PPA for Stage III is significantly lower than for Stage IV. This is biologically plausible due to the lower tumor burden and consequently lower ctDNA shed into the bloodstream in earlier-stage disease. This underscores the importance of tumor burden context when interpreting liquid biopsy results [29]. The overall high concordance in advanced disease supports the use of NGS-based liquid biopsy as a robust tool for genomic profiling when tissue is unavailable.

Essential Quality Control Metrics for NGS Liquid Biopsy

Ensuring the reliability of NGS data requires stringent quality control throughout the workflow. Key metrics established in validation studies include [29] [39]:

- Mean Effective Depth of Coverage: A minimum of >1400x is recommended for detecting low-frequency variants down to 0.2% VAF [29].

- Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) Cutoff: A 0.2% threshold is analytically validated for distinguishing true variants from background noise [29].

- Positive Percentage Agreement (PPA) & Negative Percentage Agreement (NPA): Orthogonal validation with a method like ddPCR should demonstrate >80% PPA and >95% NPA for the assay to be considered clinically reliable [29].

- Sample Quality Assessment: Pathologist review of solid tumor samples for tumor cell content is essential. For liquid biopsy, cfDNA concentration and fragment size analysis serve as initial quality checks [39].

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

NGS Liquid Biopsy and Concordance Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end process from sample collection to data analysis, highlighting key steps where quality metrics are critical.

Technology Selection Decision Pathway

This decision tree guides researchers in selecting the most appropriate technology based on the study's primary objective.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Kits for NGS Liquid Biopsy Research

| Item | Function in Workflow | Example Product / Method |

|---|---|---|

| cfDNA Collection Tubes | Stabilizes nucleated blood cells to prevent genomic DNA contamination during shipment and storage. | Cell-Free DNA BCT Tubes (Streck) [29] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Isulates high-quality, pure cfDNA from plasma or gDNA from FFPE tissue. | QIAamp FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen) [29] |

| Targeted NGS Gene Panel | Enriches for specific genomic regions of interest prior to sequencing. | USCI UgenDX Lung Cancer kit (21-gene panel) [29] |

| Orthogonal Validation Technology | Provides an independent, highly accurate method to confirm NGS-identified mutations. | Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) (Bio-Rad) [29] |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Processes raw sequencing data, aligns reads, calls variants, and filters results based on quality metrics. | BWA (alignment) + GATK (variant calling) [29] |

The establishment of rigorous analytical sensitivity parameters and quality metrics is the foundation of reliable NGS-based liquid biopsy research. As the data demonstrates, targeted NGS offers a powerful balance of high sensitivity, multiplexing capability, and discovery power, outperforming qPCR and rivaling the sensitivity of dPCR while providing a much broader genomic profile. The high concordance with tissue genotyping in advanced cancers solidifies its role in cancer genomics. For researchers and drug developers, the choice of platform must be guided by the specific study requirements—number of targets, required LOD, and the need for discovery versus confirmation—always within the context of a rigorously validated and quality-controlled workflow.

Tumor Fraction as a Critical Determinant of Liquid Biopsy Performance

Liquid biopsy, the analysis of tumor-derived components from bodily fluids such as blood, has emerged as a transformative approach in oncology, enabling non-invasive cancer detection, molecular profiling, and treatment monitoring [7] [3]. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA)—the tumor-derived fraction of cell-free DNA (cfDNA)—serves as a key analyte for detecting genomic alterations in circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) [31] [3]. The performance of these assays hinges critically on one fundamental parameter: the circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) tumor fraction (TF), defined as the proportion of ctDNA within the total cfDNA population [40] [41]. This metric serves as a primary determinant of assay sensitivity, reliability, and clinical utility.

The quantitative importance of tumor fraction becomes particularly evident in the context of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) concordance studies between tissue and liquid biopsy. Tissue biopsy remains the gold standard for tumor profiling, but spatial and temporal heterogeneity limits its ability to fully characterize metastatic disease [7] [42]. Liquid biopsy offers a complementary approach that captures contributions from multiple tumor sites, yet its accuracy depends substantially on the abundance of tumor-derived DNA in circulation [31] [41]. Understanding how tumor fraction influences detection sensitivity and concordance rates is thus essential for researchers, assay developers, and clinical oncologists seeking to implement liquid biopsy in precision oncology frameworks.

Technical Determinants: How Tumor Fraction Influences Assay Sensitivity

The Tumor Fraction Threshold Principle

The relationship between tumor fraction and variant detection follows fundamental statistical principles. At low tumor fractions, the number of mutant DNA molecules in a blood sample becomes limiting, requiring exceptionally high sequencing depth and sophisticated error-suppression techniques to distinguish true variants from technical noise [31]. Variant allele frequency (VAF), representing the proportion of sequencing reads harboring a specific mutation, is directly proportional to tumor fraction when the mutation is clonal and heterozygous [31] [40].

Table 1: Tumor Fraction Impact on Mutation Detection Probability

| Tumor Fraction | Variant Allele Frequency | Minimum Coverage for 99% Detection Probability | Expected Detection Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1% | 0.5% | ~10,000× | ~50% |

| 0.5% | 0.25% | ~20,000× | ~30% |

| 0.1% | 0.05% | ~100,000× | <10% |

As illustrated in Table 1, achieving a 99% detection probability for variants at 0.1% VAF requires approximately 10,000× coverage, while detecting variants at 0.1% VAF necessitates approximately 100,000× coverage—demonstrating the inverse exponential relationship between required sequencing depth and tumor fraction levels [31]. This relationship explains why commercial liquid biopsy assays with reported limits of detection (LOD) around 0.5% tumor fraction achieve only approximately 50% alteration detection rates in real-world settings, while improving LOD to 0.1% could increase detection rates to approximately 80% [31].

Input DNA and Biological Limitations

The absolute number of mutant DNA molecules present in a sample represents another critical constraint. A 10mL blood draw from a lung cancer patient might yield only approximately 8,000 haploid genome equivalents (GEs), with a tumor fraction of 0.1% providing a mere 8 mutant GEs for analysis—making detection statistically improbable. The same volume from a high-shedding liver cancer patient could yield approximately 80,000 GEs, providing 80 mutant GEs at the same tumor fraction and substantially improving detection probability [31]. This biological variability in ctDNA shedding across tumor types and individuals introduces significant challenges for developing universally applicable liquid biopsy assays.

Technological Innovations in Low-Tumor Fraction Detection

Several advanced technological approaches have been developed to enhance detection sensitivity at low tumor fractions:

Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) are short nucleotide sequences added to DNA fragments during library preparation that enable bioinformatic distinction between true variants and amplification artifacts [31]. Following sequencing, reads with identical UMIs are grouped and consensus sequences are generated, significantly reducing false positive calls. However, this process typically results in a 10-fold reduction in usable reads after deduplication, necessitating higher initial sequencing depth [31].

Error-Suppression Techniques such as the MUTE-Seq assay leverage engineered advanced-fidelity FnCas9 to selectively eliminate wild-type DNA molecules, thereby enriching for mutant alleles and improving signal-to-noise ratios [43]. This approach has demonstrated significant improvements in detecting low-frequency cancer-associated mutations for minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and pancreatic cancer [43].

Fragmentomics and Multi-Analyte Approaches integrate multiple features of ctDNA beyond simple mutation detection, including fragment size patterns, epigenetic markers, and proteomic signatures [43]. For example, cfDNA fragmentome analysis has demonstrated high accuracy (AUC = 0.92) in identifying liver cirrhosis and facilitating hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance, potentially offering enhanced sensitivity in low-tumor fraction scenarios [43].

Tumor Fraction and Clinical Concordance: Evidence Across Malignancies

Concordance Rates in Solid Tumors

Multiple studies have evaluated the concordance between tissue and liquid biopsy genomic profiling across various tumor types, with tumor fraction consistently emerging as a primary determinant of agreement rates.

Table 2: Tissue-Liquid Biopsy Concordance Across Tumor Types

| Tumor Type | Study/Reference | Overall Concordance | Concordance at TF ≥1% | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Solid Tumors (n=430) | Community Health Network [42] | 88% (oncogenic mutations) | N/R | 11% had actionable mutations detected only in liquid biopsy |

| Advanced NSCLC | LUNG-MAP Study [44] | N/R | Significantly improved | Elevated TF associated with worse overall survival |

| Metastatic Breast Cancer | Real-world study [40] | Variable by TF | High at TF ≥10% | TF >10% associated with significantly worse survival |

| Pancreatic Cancer | CHAMP Study [45] | High for relevant alterations | N/R | TF prognostic in palliative setting, not adjuvant |

A comprehensive analysis of 874 patients with various cancer types demonstrated that despite a wide range of cfDNA concentrations (0.50 to 1132.9 ng/mL) across 21 tumor types, matched tumor and blood specimens (n = 430 patients) revealed high concordance for coding (median = 97%) and clinical oncogenic mutations (median = 88% concordance) [42]. Importantly, this study identified an additional 48 patients (11%) with therapeutically actionable mutations detected only in liquid biopsy, highlighting the ability of ctDNA analysis to capture tumor heterogeneity that might be missed by single-site tissue biopsy [42].

Tumor Fraction Thresholds for Clinical Decision-Making

Based on accumulating evidence, specific tumor fraction thresholds have been established to guide clinical interpretation of liquid biopsy results: