Next-Generation Sequencing in Precision Oncology: A Comprehensive Review of Technologies, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has fundamentally transformed precision oncology by enabling comprehensive genomic profiling of tumors, thus guiding diagnosis, prognostication, and personalized treatment selection.

Next-Generation Sequencing in Precision Oncology: A Comprehensive Review of Technologies, Clinical Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has fundamentally transformed precision oncology by enabling comprehensive genomic profiling of tumors, thus guiding diagnosis, prognostication, and personalized treatment selection. This review synthesizes current evidence on NGS technologies, including short- and long-read platforms, and their clinical applications in identifying actionable mutations, immunotherapy biomarkers, and resistance mechanisms. We detail the implementation of tissue-based and liquid biopsy approaches, discuss challenges in data interpretation and clinical integration, and provide a comparative analysis of sequencing methodologies and bioinformatics tools. For researchers and drug development professionals, this article outlines the critical role of NGS in advancing biomarker discovery, clinical trial design, and the development of targeted therapies, while also addressing future directions such as the integration of multi-omics data and artificial intelligence.

The Genomic Revolution: Core Principles and Technological Evolution of NGS in Oncology

The field of cancer genomics has undergone a revolutionary transformation, driven by a fundamental shift in sequencing technologies. This paradigm moved from first-generation Sanger sequencing to massively parallel next-generation sequencing (NGS), also known as high-throughput sequencing [1] [2]. This technological evolution has enabled the comprehensive molecular profiling of tumors, revealing the complex genetic alterations that drive cancer initiation and progression [3]. The rapid decrease in sequencing costs and the concurrent increase in throughput have made NGS increasingly accessible, allowing it to replace most other methods for precision cancer diagnostics [2]. This shift has been instrumental in realizing precision cancer medicine, where treatment decisions are guided by the specific genetic alterations present in an individual's tumor [4] [2]. This technical guide explores the core principles of this sequencing revolution, its clinical applications, and the practical methodologies that underpin modern genomic oncology.

A Technical Comparison of Sequencing Generations

Sanger Sequencing: The Chain Termination Method

Sanger sequencing, developed by Frederick Sanger in 1977, is known as the "chain termination method" and served as the foundational technology for DNA sequencing for decades [5]. Its principle involves using a DNA primer, DNA polymerase, normal deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), and modified dideoxynucleotide triphosphates (ddNTPs) that lack a 3'-OH group, which is necessary for DNA strand elongation [5]. When a ddNTP is incorporated into the growing DNA strand, synthesis terminates, producing DNA fragments of varying lengths. These fragments are separated by capillary electrophoresis, and the sequence is determined by detecting the fluorescent labels attached to the terminating ddNTPs [5]. Sanger sequencing provides long read lengths (800-1000 base pairs) and high base accuracy (99.99%), making it the historical "gold standard" for validating DNA sequences [5].

Next-Generation Sequencing: The Principle of Massively Parallel Sequencing

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) represents a fundamental departure from Sanger's linear approach. Also termed massively parallel sequencing, NGS allows for the simultaneous sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments [1] [6]. The core principle involves fragmenting DNA into a library of small pieces, attaching adapters to these fragments, immobilizing them on a solid surface or in emulsion, and performing cyclic sequencing reactions that generate detectable signals [3] [6]. Unlike Sanger sequencing, which processes a single DNA fragment at a time, NGS technologies detect the incorporation of nucleotides in thousands to millions of parallel reactions, generating enormous volumes of sequence data in a single run [3].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Sanger Sequencing vs. Next-Generation Sequencing

| Feature | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Principle | Chain termination with ddNTPs and electrophoretic separation [5] | Massive parallel sequencing of clonally amplified or single DNA molecules [3] [6] |

| Throughput | Low; processes one sequence at a time [3] | Very high; processes millions of sequences simultaneously [3] [1] |

| Read Length | Long (800-1000 bases) [5] | Short to long (50-400 bases for short-read; 10,000+ for long-read) [6] |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Lower for sequencing single genes or small projects [5] | Higher for large-scale projects and genomic profiling [3] [5] |

| Speed | Relatively slow for large projects [5] | Rapid; entire human genome in days [3] |

| Primary Applications | Sequencing single genes, validating mutations, cloned inserts [5] | Whole genomes, exomes, transcriptomes, gene panels, epigenomics [3] [2] |

| Variant Detection Sensitivity | Lower sensitivity for mutations present at low allele frequency (<10-20%) [7] | High sensitivity, capable of detecting low-frequency mutations [7] |

The NGS Workflow: From Sample to Data

The standard NGS workflow involves a series of critical, interconnected steps to convert a biological sample into interpretable genomic data.

Sample Preparation and Library Construction

The initial step involves extracting and quantifying DNA or RNA from patient samples, typically formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissue or blood [3] [7]. The quality of the input nucleic acids is critical for successful sequencing. For DNA sequencing, the extracted genomic DNA is fragmented, either physically, enzymatically, or chemically, to a size of around 300 base pairs [3]. Adapters—short, synthetic oligonucleotides with known sequences—are then ligated to the fragmented DNA ends. These adapters are essential for attaching the DNA fragments to the sequencing platform (e.g., a flow cell) and for subsequent amplification steps [3]. The resulting product is a "sequencing library." Depending on the application, libraries can be constructed for whole-genome, whole-exome, or targeted sequencing. For targeted approaches, an enrichment step using hybridization probes or PCR with specific primers is performed to isolate genomic regions of interest [3] [7].

Template Amplification and Clonal Cluster Generation

To generate a detectable signal, most NGS platforms require the amplification of single DNA molecules from the library. The two primary methods are:

- Emulsion PCR (emPCR): Used by platforms like Ion Torrent. Single-stranded DNA library fragments are bound to beads, and each bead is encapsulated in a water-in-oil emulsion droplet, creating a microreactor for clonal amplification via PCR [6].

- Bridge Amplification: Used by Illumina platforms. The single-stranded library is loaded into a flow cell where fragments hybridize to complementary surface-bound oligonucleotides. Through repeated cycles of denaturation and polymerase extension, each fragment is amplified into a clonal cluster, locally concentrated to yield a strong signal [3] [6].

Sequencing Reaction and Data Generation

The core sequencing reaction involves the cyclic addition of nucleotides and imaging. The most common chemistry is Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) with reversible terminators, used by Illumina [3] [6]. In this process, the flow cell is flooded with fluorescently labeled nucleotides that also act as reversible terminators. In each cycle, a single complementary nucleotide is incorporated into each growing DNA strand, the fluorescence is imaged to identify the base, and then the terminator is chemically cleaved to allow the next incorporation cycle [3]. Other chemistries include pyrosequencing (454/Roche) and semiconductor sequencing (Ion Torrent), which detects hydrogen ions released during nucleotide incorporation [6].

Data Analysis and Bioinformatics

The final and most complex stage is bioinformatic analysis of the massive datasets generated [3]. The process typically involves:

- Base Calling: Translating raw signal data (images or pH changes) into nucleotide sequences (reads).

- Alignment/Mapping: Assembling short reads by aligning them to a reference human genome (e.g., hg19/GRCh38).

- Variant Calling: Using specialized algorithms to identify differences between the sequenced sample and the reference genome, including single nucleotide variants (SNVs), small insertions/deletions (indels), and copy number variations (CNVs) [3].

- Annotation and Interpretation: Determining the functional and clinical impact of identified variants (e.g., missense, nonsense), their frequency in population databases, and, crucially, their known or potential actionability as therapeutic targets or resistance markers [4].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for NGS in Cancer Genomics

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | QIAamp DNA Mini Kit [7] | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from tissue or blood samples. |

| Target Enrichment | Ion AmpliSeq Panels [7] | Multiplex PCR-based amplification of a targeted set of cancer-related genes. |

| Library Prep Kits | Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit [7] | Preparation of fragmented and adapter-ligated DNA for sequencing. |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina MiSeq, HiSeq, NovaSeq; Ion Torrent PGM/Proton [7] [6] | Instruments performing massively parallel sequencing. |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Torrent Suite Software, Variant Caller [7] | Software for base calling, alignment, and variant identification. |

| Clinical Databases | OncoKB, MyCancerGenome, COSMIC [4] | Curated knowledgebases for interpreting the clinical significance of somatic variants. |

Clinical Applications and Experimental Design in Precision Oncology

The implementation of NGS in oncology has moved beyond research into routine clinical practice, enabling a wide range of applications that guide patient care.

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling

NGS enables simultaneous assessment of a multitude of genomic biomarkers, which is essential given the molecular heterogeneity of cancer. This is primarily achieved through:

- Targeted Gene Panels: Focused panels sequencing dozens to hundreds of cancer-associated genes. They offer high sequencing depth, making them cost-effective and ideal for detecting low-level mutations in samples with limited tumor content [7] [2]. They are widely used to identify actionable mutations for therapy selection in cancers like lung adenocarcinoma and melanoma [2].

- Whole Exome Sequencing (WES): Captures the protein-coding regions of the genome (~1-2%), where most known disease-causing variants reside. It provides a broader view than panels but less data than WGS [3] [2].

- Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS): Interrogates the entire genome, including non-coding regions. It provides the most comprehensive view, enabling detection of SNVs, indels, CNVs, and structural variants (SVs) like gene fusions from a single assay [3] [2]. It is increasingly used for pediatric cancers and rare malignancies to uncover novel drivers [2].

Monitoring Treatment Response and Residual Disease

NGS provides a highly sensitive tool for longitudinal monitoring of tumor dynamics. By tracking specific mutations in cell-free DNA (cfDNA) from patient blood plasma—a "liquid biopsy"—clinicians can monitor treatment response, detect emerging resistance mechanisms, and identify minimal residual disease (MRD) long before it becomes clinically apparent [3] [2]. This requires deep sequencing (high coverage) to detect mutations present at very low allele frequencies, enabling timely intervention and treatment adjustment [2].

A Practical Experimental Protocol: Targeted NGS for Solid Tumors

The following protocol, derived from a breast cancer study [7], outlines a typical workflow for targeted NGS using a semiconductor sequencer.

Aim: To identify somatic mutations in the PIK3CA gene and other cancer-related genes in 186 primary breast carcinomas. Methods:

- Sample Selection and DNA Extraction: Select FFPE tumor samples with at least 30% tumor cell content. Macro- or micro-dissect the marked tumor area. Extract genomic DNA using a commercial kit (e.g., QIAamp DNA Mini Kit) and quantify using a fluorometer (e.g., Qubit) [7].

- Library Preparation: Use 10 ng of genomic DNA. Prepare the sequencing library using a targeted panel (e.g., a custom 154-amplicon panel covering 48 genes) and a library preparation kit (e.g., Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit 2.0). Amplify the target regions via multiplex PCR [7].

- Template Preparation and Sequencing: Clonally amplify the library using emulsion PCR (e.g., with the Ion OneTouch system). Enrich template-positive beads and load onto a semiconductor sequencing chip (e.g., Ion 318 chip). Sequence on the appropriate platform (e.g., Ion Torrent PGM) [7].

- Data Analysis: Perform base calling and alignment to the reference genome (hg19) using the platform's software suite (e.g., Torrent Suite). Call variants with a built-in algorithm (e.g., Torrent Variant Caller), applying appropriate filters for quality and strand bias [7].

- Validation: Confirm a subset of mutations, especially those with low allele frequency or clinical significance, using an independent method like Sanger sequencing [7].

Translating Genomic Data into Clinical Action

Interpreting NGS data and translating it into a therapeutic strategy is a critical challenge in precision oncology. The process requires sophisticated tools and multidisciplinary expertise.

The Role of Precision Oncology Platforms

To aid clinicians, several curated knowledgebases have been developed. These platforms consolidate genomic data and clinical evidence into standardized, accessible formats [4]. When an NGS report lists a set of somatic variants, clinicians and molecular pathologists can query these databases to determine the clinical significance of each alteration. Key platforms include:

- OncoKB: A precision oncology database that annotates the therapeutic and prognostic implications of individual gene alterations, with levels of evidence ranging from standard-of-care to investigational therapies [4].

- MyCancerGenome: Provides detailed information on genomic alterations in cancer, focusing on their potential clinical implications and linking mutations to relevant clinical trials and targeted therapies [4].

- CIViC (Clinical Interpretation of Variants in Cancer): A community-driven resource that crowdsources clinical evidence for the interpretation of variants in cancer [4].

Molecular Tumor Boards

The final interpretation often occurs within a Molecular Tumor Board (MTB), a multidisciplinary team comprising oncologists, molecular pathologists, genetic counselors, bioinformaticians, and clinical geneticists [8] [4]. The MTB reviews the NGS findings in the context of the patient's clinical history, pathology, and evidence from precision oncology platforms to formulate a personalized treatment recommendation, which may include approved targeted therapies, clinical trial enrollment, or analysis of potential hereditary cancer risk [8].

The shift from Sanger to massively parallel sequencing represents a true paradigm shift, fundamentally altering the approach to cancer diagnosis, classification, and treatment. NGS has provided an unprecedented, comprehensive view of the cancer genome, forming the bedrock of precision oncology [2]. As the technology continues to evolve, future developments promise to further refine this field. These include the clinical integration of single-cell sequencing to resolve tumor heterogeneity [3], the expanded use of liquid biopsies for non-invasive monitoring [2], the application of long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) to resolve complex genomic regions, and the integration of artificial intelligence to improve variant interpretation and predict therapeutic responses [4]. The ongoing challenge lies not in generating data, but in robustly interpreting it and translating these insights into improved patient outcomes through equitable and clinically validated interventions.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized molecular biology and oncology by fundamentally redefining approaches to disease research and clinical diagnostics [9]. Since its widespread adoption, NGS has progressively displaced traditional Sanger sequencing, becoming integral to contemporary genomic medicine and precision oncology [9]. This transformative technology enables comprehensive genomic profiling of tumors, facilitating the identification of driver mutations, fusion genes, and predictive biomarkers across diverse cancer types [9]. The capacity of NGS to simultaneously interrogate hundreds to thousands of genetic targets has made it indispensable for personalized cancer therapy, clinical trial design, and biomarker discovery [10] [11].

In precision oncology, NGS provides clinically actionable molecular insights that guide diagnosis, prognostication, therapeutic selection, and monitoring of treatment response [9]. The fundamental principles of throughput, sensitivity, and scalability define its operational capabilities and determine its appropriate application in both research and clinical settings. This technical guide examines these core principles in detail, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding NGS capabilities within precision oncology.

Core Principles of NGS Technology

Throughput: Massively Parallel Sequencing Architecture

The defining attribute of NGS is its massively parallel sequencing architecture, which enables the concurrent analysis of millions of DNA fragments in a single run [9]. This represents a fundamental departure from Sanger sequencing, which processes one DNA fragment at a time, making it laborious, costly, and time-consuming for large-scale analysis [9]. The massively parallel approach allows NGS to simultaneously evaluate hundreds to thousands of genes in a single assay, offering a comprehensive genomic landscape rather than the fragmented approach inherent to Sanger sequencing [9].

Throughput capabilities vary significantly across NGS platforms. Second-generation platforms (e.g., Illumina) typically generate short reads (75-300 base pairs) with exceptionally high throughput and low error rates (typically 0.1-0.6%) [9]. Third-generation technologies (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) offer longer read lengths (up to 100,000+ base pairs) through single-molecule real-time sequencing, providing advantages for resolving complex genomic regions and structural variations [9]. This parallel architecture provides markedly increased sequencing depth and sensitivity, detecting low-frequency variants down to ~1% variant allele frequency, and shortens turnaround times—an entire human genome can be sequenced in approximately one week, compared with years using Sanger technology [9].

Table 1: Throughput Comparison Between Sanger and NGS Technologies

| Aspect | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Single DNA fragment at a time | Massively parallel; millions of fragments simultaneously |

| Sensitivity (detection limit) | Low (~15–20%) | High (down to 1% for low-frequency variants) |

| Cost-effectiveness | Cost-effective for 1–20 targets, high for large regions | Cost-effective for high sample volumes/many targets |

| Discovery power | Limited; interrogates a gene of interest | High; detects novel or rare variants with deep sequencing |

| Read length | Typically, up to 1000 base pairs | Short (75–300 bp) to Ultra-long (100,000+ bp) |

| Turnaround time | Years for the whole genome | About a week for the whole genome |

| Variant detection capability | Limited to specific regions; single gene analysis | Single-base resolution; detects SNPs, indels, CNVs, SVs, and large chromosomal rearrangements |

Sensitivity: Detection of Low-Frequency Variants

Sensitivity in NGS refers to the technology's ability to detect low-frequency genetic variants present in a minor subset of cells within a heterogeneous sample. NGS demonstrates significantly enhanced sensitivity compared to traditional methods, with detection limits reaching approximately 1% variant allele frequency (VAF) for low-frequency variants, a substantial improvement over Sanger sequencing's ~15-20% detection limit [9]. This heightened sensitivity is particularly crucial in oncology applications for detecting minimal residual disease (MRD), monitoring treatment resistance, and identifying emerging subclones during tumor evolution [12].

The sensitivity of NGS is directly influenced by sequencing depth (coverage), which refers to the number of times a specific nucleotide is read during sequencing. Higher sequencing depths increase confidence in variant calling, particularly for heterogeneous tumor samples where mutant alleles may be present at low frequencies. In practice, targeted NGS panels achieve significantly higher sequencing depths (often >500x) compared to whole-genome sequencing, enabling more reliable detection of low-frequency somatic mutations [10]. This enhanced sensitivity allows NGS to identify novel or rare variants, structural rearrangements, and large chromosomal abnormalities at single-nucleotide resolution [9].

Scalability: Flexible Experimental Design

Scalability represents a third fundamental principle of NGS technology, encompassing its adaptability to various experimental designs and throughput requirements. NGS platforms offer remarkable flexibility, supporting applications ranging from targeted gene panels (dozens to hundreds of genes) to whole-exome sequencing (approximately 1% of the human genome) and whole-genome sequencing (entire genomic content) [10]. This scalability enables researchers to tailor sequencing approaches to specific research questions while optimizing resources and costs.

In clinical oncology practice, targeted panel sequencing represents the most commonly used NGS application, typically interrogating dozens or hundreds of cancer-relevant genes [10]. Compared to whole-genome sequencing, targeted panels provide substantially greater sequencing depth for the same sequencing effort, which is necessary to detect mutations with varying allelic frequencies in tumor samples [10]. The scalable nature of NGS also facilitates sample multiplexing, allowing multiple samples to be sequenced simultaneously in a single run through barcoding strategies, thereby increasing throughput and reducing per-sample costs [9].

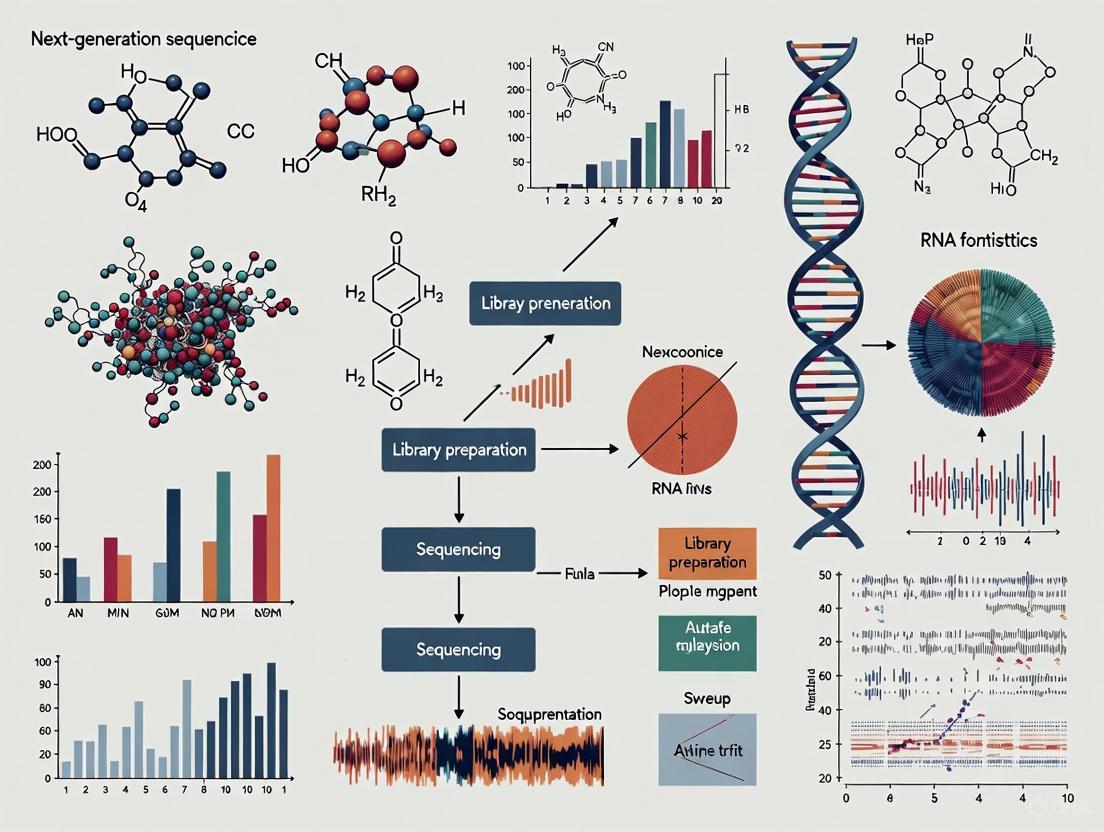

Figure 1: NGS Workflow from Sample to Result. The process begins with sample preparation and proceeds through nucleic acid extraction, library preparation, massively parallel sequencing, bioinformatics analysis, and final clinical interpretation.

NGS Workflow and Methodologies

Experimental Workflow

The standard NGS workflow involves multiple interconnected steps, each critical to achieving accurate and reproducible results. The process begins with DNA fragmentation, where targeted DNA is broken into short segments (typically 100-300 bp in length) using mechanical methods, enzymatic digestion, or other fragmentation techniques [10]. For targeted sequencing approaches, relevant segments are isolated using either hybridization capture (using specific complementary probes) or amplicon-based approaches (using PCR amplification with multiple primer pairs) [10].

Library preparation follows fragmentation, wherein DNA segments are modified to include sample-specific indices (barcodes) and sequencing adaptors [10]. This process enables sample multiplexing and allows sequencing primers to bind to all DNA fragments, facilitating the massively parallel sequencing step. The prepared libraries are then loaded onto sequencing matrices (e.g., flow cells for Illumina platforms, sequencing chips for Ion Torrent) for the massive parallel sequencing reaction, where millions to billions of DNA fragments are simultaneously sequenced [10].

Following sequencing, bioinformatics analysis processes the raw data through base calling, read alignment, variant identification, and variant annotation [10]. During this computational phase, sequence information is compared to a human reference genome to identify variants, and information from each sequenced segment is pieced together to generate final sequencing results for the full length of the targeted DNA [10]. The final annotation and interpretation phase identifies each variant and assesses its potential biological and clinical significance, a particularly crucial step for precision oncology applications [10].

Platform Technologies

The choice of NGS platform represents a strategic decision that directly influences the feasibility and success of research or clinical projects, as each technology excels in different applications. Illumina sequencing dominates second-generation NGS due to its exceptionally high throughput, low error rates, and attractive cost per base [9]. It employs sequencing-by-synthesis chemistry, enabling millions of DNA fragments to be sequenced in parallel on a flow cell, with established bioinformatics pipelines well-optimized for Illumina data [9].

Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) utilizes a distinctive approach involving direct reading of single DNA molecules as they traverse protein nanopores [9]. This technology provides ultra-long read lengths, real-time data analysis, and portability, though with generally higher error rates compared to Illumina platforms. Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) offers single-molecule real-time sequencing that generates long reads with minimal bias, advantageous for resolving complex genomic regions, detecting structural variants, and performing de novo assemblies [9].

Table 2: Comparison of Major NGS Platform Types

| Characteristic | Second-Generation (Short-Read) | Third-Generation (Long-Read) |

|---|---|---|

| Representative Platforms | Illumina | Oxford Nanopore, Pacific Biosciences |

| Read Length | Short (75-300 bp) | Long (10,000-100,000+ bp) |

| Error Rates | Low (0.1-0.6%) | Higher (1-15% depending on technology) |

| Primary Strengths | High accuracy, low cost per base, established protocols | Detection of structural variants, resolution of repetitive regions, haplotype phasing |

| Primary Applications | Variant detection, transcriptome profiling, targeted sequencing | De novo assembly, complex variant detection, epigenetics |

| Throughput | Very high | Moderate to high |

| Run Time | Hours to days | Minutes to days |

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of NGS workflows requires specific reagents and materials optimized for each procedural step. The following table details essential components for establishing a robust NGS pipeline in a research or clinical setting:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for NGS Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits (e.g., QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit) | Isolation of high-quality DNA from various sample types including FFPE tissue [13]. | Critical for obtaining sufficient quality/quantity; FFPE extraction requires specialized protocols to address cross-linking and fragmentation. |

| DNA Quantification Assays (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay) | Accurate quantification of DNA concentration [13]. | Fluorometric methods preferred over spectrophotometry for better accuracy with fragmented DNA. |

| Library Preparation Kits (e.g., Agilent SureSelectXT) | Fragmentation, adapter ligation, and target enrichment [13]. | Choice between hybridization capture vs. amplicon-based depends on panel design and application requirements. |

| Target Enrichment Panels | Selection of genomic regions of interest | Custom or commercial panels available; pan-cancer designs typically cover hundreds of cancer-relevant genes. |

| Sequenceing Flow Cells/Chips | Platform-specific matrix for sequencing reactions | Capacity and configuration vary by platform; determines maximum throughput per run. |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Base calling, alignment, variant calling, and annotation [9] | Critical for data interpretation; requires specialized computational expertise and resources. |

Applications in Precision Oncology and Drug Development

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling in Cancer Care

NGS enables comprehensive genomic profiling (CGP) of tumors, simultaneously evaluating multiple variant types including small variants (substitutions, insertions, deletions), copy number alterations, and rearrangements (fusions and splice variants) [14]. This comprehensive approach provides a tumor-agnostic method to detect similar molecular alterations across histologies, supporting targeted therapy selection, immunotherapy response prediction, and clinical trial matching [14]. The capacity to identify novel and emerging biomarkers has become increasingly important with FDA approvals for tumor mutational burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI) as genomic biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint inhibitors [14].

In clinical practice, CGP by NGS demonstrates significant utility for guiding treatment decisions. A 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis of NGS applications in childhood and adolescent/young adult solid tumors found a pooled proportion of 57.9% actionable alterations across studies, with 22.8% impacting clinical decision-making [15]. Real-world implementation studies at tertiary care centers have demonstrated that approximately 26% of patients harbor tier I variants (strong clinical significance), with 13.7% of these patients receiving NGS-based therapy based on novel information provided by sequencing [13].

Liquid Biopsy and Circulating Tumor DNA

Liquid biopsy approaches utilizing circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) represent a rapidly advancing application of NGS in oncology [9]. These minimally invasive tests enable real-time monitoring of tumor dynamics, assessment of molecular heterogeneity, and detection of emerging resistance mechanisms [9]. In translational research and drug development, ctDNA monitoring provides valuable tools for evaluating changes in tumor burden over time, assessing dose selection in early-phase clinical trials, and monitoring individual variants to identify acquired resistance across hundreds of genes [11].

The scalability and sensitivity of NGS platforms make them ideally suited for liquid biopsy applications, where genetic material is often limited and variant allele frequencies can be extremely low. Advanced NGS approaches can quantify ctDNA tumor fraction, a biomarker that incorporates multi-omic information to improve sensitivity while maintaining high specificity for monitoring ctDNA levels [11]. These capabilities position liquid biopsy as a complementary approach to tissue-based profiling, particularly when tissue is insufficient or serial monitoring is required.

Figure 2: Interrelationship of NGS Core Principles and Their Applications in Oncology. Throughput, sensitivity, and scalability collectively enable diverse applications in precision oncology, with each principle contributing differently to specific applications.

The fundamental principles of throughput, sensitivity, and scalability establish NGS as an indispensable technology in precision oncology and drug development. The massively parallel sequencing architecture of NGS platforms enables unprecedented throughput, allowing comprehensive genomic assessment that was previously impractical with sequential testing approaches. Enhanced sensitivity permits detection of low-frequency variants critical for understanding tumor heterogeneity, monitoring minimal residual disease, and identifying emerging resistance mechanisms. Remarkable scalability provides flexibility in experimental design, supporting applications ranging from focused targeted panels to genome-wide sequencing approaches.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these core principles is essential for appropriate technology selection, experimental design, and data interpretation. As NGS continues to evolve, integration with artificial intelligence, single-cell sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, multi-omics, and nanotechnology promises to overcome current limitations and advance personalized treatment strategies [9]. Standardization of workflows, cost reduction, and improved bioinformatics expertise will be critical for the full clinical integration of these advances [9]. The ongoing refinement of NGS technologies ensures their continuing centrality in precision oncology, enabling increasingly sophisticated molecularly driven cancer care and therapeutic development.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized precision oncology by enabling comprehensive genomic profiling of tumors, which is fundamental for understanding cancer development, progression, and treatment response. These technologies allow researchers and clinicians to identify specific genetic mutations, structural variations, and epigenetic modifications that drive oncogenesis [16]. The transition from first-generation Sanger sequencing to NGS has compressed research timelines from years to days, making large-scale genomic studies feasible and transforming cancer care toward a more personalized approach [16]. The global NGS market, valued at USD 15.53 billion in 2025, reflects this transformative impact, particularly in oncology applications which represent the largest market segment [17].

In precision oncology, the selection of an appropriate sequencing platform is dictated by specific research goals, including the need for particular resolution, sample availability, and the variants of interest. The three major platforms—Illumina, Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), and PacBio—each offer distinct advantages and limitations for different oncology research applications [18]. This technical guide provides an in-depth comparison of these platforms, their methodologies, and their applications in precision oncology research.

Platform-Specific Technologies and Methodologies

Illumina: Short-Read Sequencing by Synthesis

Technology Principle: Illumina's technology is based on sequencing by synthesis (SBS) with fluorescently tagged nucleotides [16]. The process begins with library preparation where DNA is fragmented and adapters are ligated to the ends. These fragments are then bound to a flow cell and amplified through bridge amplification to create clusters of identical DNA molecules. During sequencing, fluorescently-labeled nucleotides are incorporated one at a time, with each nucleotide emitting a specific color signal that is captured by imaging systems [16].

Key Technical Specifications:

- Read Length: Typically generates short reads of 50-600 base pairs, with common outputs of 2×300 bp for paired-end sequencing [16] [18].

- Error Rate: Less than 0.1%, making it highly accurate for base calling [18].

- Output: High throughput, generating millions to billions of reads per run [16].

Illumina SBS Workflow: Library preparation, cluster generation, and sequence detection.

PacBio: Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) Sequencing

Technology Principle: PacBio's HiFi (High Fidelity) sequencing utilizes single molecule, real-time (SMRT) technology [19]. The system employs a SMRT cell containing millions of zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs)—nanophotonic structures that confine light to zeptoliter volumes. Within each ZMW, a single DNA polymerase enzyme is immobilized and incorporates fluorescently-labeled nucleotides onto a template DNA strand. The key innovation is the real-time detection of nucleotide incorporation events through emitted fluorescence, without the need for amplification [20] [19].

Key Technical Specifications:

- Read Length: 500 to 20,000+ bases, with typical HiFi reads of 15,000-20,000 bases [19].

- Accuracy: Q30 (99.9%) to Q33 (99.95%) for HiFi reads after circular consensus sequencing [19].

- Run Time: Approximately 24 hours for a typical run [19].

PacBio SMRT sequencing: SMRT cell, real-time detection, and HiFi read generation.

Oxford Nanopore Technologies: Nanopore Sequencing

Technology Principle: ONT sequencing is based on the measurement of electrical current changes as DNA or RNA molecules pass through protein nanopores embedded in a polymer membrane [19]. Each nucleotide base causes a characteristic disruption in the ionic current as the nucleic acid strand translocates through the nanopore. These current changes are decoded in real-time through sophisticated base-calling algorithms to determine the DNA sequence [18] [19].

Key Technical Specifications:

- Read Length: 20 bases to over 4 megabases, capable of producing ultra-long reads [19].

- Accuracy: Approximately Q20 (99%) with current chemistries and base-calling algorithms [18] [19].

- Run Time: Flexible, from minutes to 72 hours, with real-time data streaming [18] [19].

ONT nanopore sequencing: Sample preparation, membrane crossing, and signal decoding.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Technical Specifications Comparison

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of major NGS platforms for precision oncology research

| Parameter | Illumina | PacBio HiFi | Oxford Nanopore |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Length | 50-600 bp (short) | 500-20,000+ bp (long) | 20 bp->4 Mb (ultra-long) |

| Accuracy | >99.9% (Q30) [18] | 99.9% (Q30) [19] | ~99% (Q20) [18] [19] |

| Typical Run Time | Hours to days | ~24 hours [19] | Minutes to 72 hours [18] [19] |

| Variant Detection - SNVs | Excellent | Yes [19] | Yes [19] |

| Variant Detection - Indels | Good | Yes [19] | Limited in repeats [19] |

| Variant Detection - SVs | Limited | Yes [19] | Yes [19] |

| Epigenetic Detection | Requires bisulfite treatment | 5mC, 6mA without treatment [19] | 5mC, 5hmC, 6mA [19] |

| RNA Sequencing | Via cDNA | Via cDNA [19] | Direct RNA sequencing [19] |

| Portability | Benchtop systems | Laboratory systems | Portable (MinION) to large [19] |

| Key Oncology Applications | Tumor profiling, liquid biopsies [16] | Phased variants, complex regions [20] | Rapid diagnostics, methylation [21] |

Performance in Microbial and Metagenomic Studies

Recent comparative studies highlight platform-specific performance characteristics in microbiome analysis, which has implications for cancer microbiome research. A 2025 study comparing Illumina and ONT for 16S rRNA profiling of respiratory microbial communities found that Illumina captured greater species richness, while ONT provided improved resolution for dominant bacterial species [18]. Beta diversity differences were more pronounced in complex microbiomes, suggesting that platform effects vary by sample type.

Another 2025 study comparing all three platforms for rabbit gut microbiota analysis demonstrated that full-length 16S sequencing with PacBio and ONT offered better species-level resolution (63% and 76% respectively) compared to Illumina (48%) [22]. However, a significant limitation across all platforms was that most species-level classifications were labeled as "uncultured bacterium," indicating reference database limitations rather than technological shortcomings [22].

Experimental Design and Protocols

Sample Preparation Guidelines

DNA Quality and Quantity: For all NGS platforms in precision oncology applications, high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA is essential. Recommended extraction methods include phenol-chloroform or commercial kits designed for long-read sequencing. DNA integrity should be verified via pulsed-field gel electrophoresis or Fragment Analyzer systems, with DNA Integrity Numbers (DIN) >7.0 considered optimal [22] [18].

Input Requirements:

- Illumina: 1-1000 ng, flexible with input due to amplification

- PacBio: 1-5 μg for standard libraries, with recommendations for >50 kb fragment sizes

- Oxford Nanopore: 100 ng-1 μg, with higher inputs improving ultra-long read yield

Library Preparation Protocols

Table 2: Comparison of library preparation methods across platforms

| Step | Illumina | PacBio | Oxford Nanopore |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fragmentation | Mechanical or enzymatic shearing | Size selection optional | Optional fragmentation |

| End Repair | Required | A-tailing | Ligation-ready |

| Adapter Ligation | Indexed adapters | SMRTbell adapters | Ligation or rapid kits |

| Size Selection | SPRI beads | BluePippin or SPRI | SPRI beads |

| PCR Amplification | Typically 4-10 cycles | Optional | Optional |

| Quality Control | Bioanalyzer, qPCR | Fragment Analyzer, Qubit | Qubit, agarose gel |

Platform-Specific Considerations:

- Illumina: Amplification can introduce biases in GC-rich regions; unique dual indexes are recommended for multiplexing to minimize index hopping [16].

- PacBio: SMRTbell library construction involves creating circular templates; shearing is minimized to preserve long fragments [20].

- Oxford Nanopore: The 16S Barcoding Kit (SQK-16S024) enables full-length 16S rRNA amplification with barcoding for multiplexing [22] [18].

Bioinformatics Processing Pipelines

Illumina Data Analysis:

- Quality Control: FastQC for read quality assessment

- Adapter Trimming: Cutadapt or Trimmomatic

- Read Alignment: BWA-MEM or Bowtie2 for reference-based alignment

- Variant Calling: GATK, Mutect2 for somatic variants

PacBio HiFi Data Analysis:

- CCS Read Generation: Circular Consensus Sequencing to produce HiFi reads

- Alignment: Minimap2 or pbmm2 for long reads

- Variant Calling: DeepVariant or pbsv for structural variants

Oxford Nanopore Data Analysis:

- Basecalling: Dorado or Guppy for converting raw signals to sequences

- Quality Control: NanoPlot for quality assessment

- Alignment: Minimap2 for long-read alignment

- Variant Calling: Clair3 or Medaka for variant detection

Applications in Precision Oncology Research

Tumor Genomic Profiling

Comprehensive Genomic Characterization: Illumina's TruSight Oncology Comprehensive test provides extensive genomic profiling for solid tumors, enabling detection of key biomarkers such as KRAS mutations that are crucial for therapy selection [23]. These tests help match patients to targeted therapies and clinical trials based on the specific molecular alterations in their tumors.

Structural Variant Detection: PacBio HiFi sequencing excels in identifying complex structural variants in cancer genomes, including gene fusions, amplifications, and rearrangements that are challenging to detect with short-read technologies [20]. This capability is particularly valuable in pediatric cancers and hematological malignancies where structural variants are common drivers.

Epigenetic Analysis in Cancer

Methylation Profiling: Both PacBio and Oxford Nanopore technologies can detect DNA methylation natively without bisulfite conversion [19]. ONT has been used to develop the Acute Leukemia Methylome Atlas from over 3,000 leukemia samples, demonstrating how long-read sequencing combined with machine learning can predict AML subtypes and patient outcomes with high accuracy [21].

Chromatin Accessibility: The combination of long-read sequencing with epigenetic assays enables phased epigenomic profiling, allowing researchers to determine how epigenetic marks are distributed across parental chromosomes—a crucial consideration in cancer imprinting and allele-specific expression.

Transcriptomics and Isoform Sequencing

Alternative Splicing Analysis: PacBio HiFi sequencing has enabled the creation of the first single-cell splicing atlas of human CD8⁺ T cells, capturing dynamic isoform programs across activation and subset differentiation [20]. This research revealed that approximately 50% of differentially expressed isoforms showed isoform-specific regulation without corresponding changes in overall gene expression, highlighting the importance of isoform-resolution analysis in cancer immunology.

Direct RNA Sequencing: Oxford Nanopore's capability for direct RNA sequencing without cDNA conversion preserves RNA modifications and provides full-length transcript information, enabling the discovery of novel isoforms and fusion transcripts in cancer cells [19].

Liquid Biopsies and Minimal Residual Disease

Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis: Illumina's short-read platforms are widely used for liquid biopsy applications due to their high accuracy and sensitivity for detecting low-frequency variants in circulating tumor DNA [16]. This approach enables non-invasive monitoring of treatment response and detection of minimal residual disease.

Comprehensive Liquid Biopsy: Long-read technologies are emerging for liquid biopsy applications, particularly for detecting structural variants and epigenetic modifications in circulating DNA that may provide additional information about tumor evolution and heterogeneity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for NGS in precision oncology

| Reagent/Material | Function | Platform Compatibility |

|---|---|---|

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit | DNA extraction from challenging samples | All platforms [22] |

| QIAseq 16S/ITS Region Panel | Targeted 16S/ITS amplification | Illumina [18] |

| SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit | Library preparation for SMRT sequencing | PacBio [22] |

| ONT 16S Barcoding Kit | Full-length 16S amplification and barcoding | Oxford Nanopore [22] [18] |

| Nextera XT Index Kit | Dual indexing for multiplexing | Illumina [22] |

| Circulomics Nanobind DNA Extraction | HMW DNA extraction for long reads | PacBio, ONT |

| SPRIselect Beads | Size selection and clean-up | All platforms |

| Qubit dsDNA HS Assay | Accurate DNA quantification | All platforms |

Future Directions in Precision Oncology Sequencing

The NGS landscape continues to evolve with emerging trends that will further enhance precision oncology research. Single-cell sequencing enables the analysis of individual cells within tumor ecosystems, revealing heterogeneity and rare cell populations [17]. Multi-omic integration approaches combine genomic, epigenomic, and transcriptomic data from the same samples, providing comprehensive views of cancer biology [24]. The integration of AI and machine learning with NGS data analysis is improving variant interpretation and clinical decision support [17].

Recent regulatory approvals, such as the first clinical long-read sequencing system in China (PacBio's Sequel II CNDx) for thalassemia testing, signal the transition of long-read technologies from research to clinical applications in oncology [25]. As these technologies continue to mature, they will increasingly enable researchers and clinicians to unravel the complex genomic architecture of cancer and develop more effective, personalized treatment strategies.

The Global Cancer Burden and the Imperative for Precision Diagnostics

The global burden of cancer continues to grow, with projections indicating a dramatic increase to over 35 million new cases annually by 2050, representing a 77% rise from 2022 estimates [26]. This escalating burden, characterized by significant health disparities and economic impacts, necessitates a paradigm shift from traditional one-size-fits-all treatment approaches toward precision diagnostics. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has emerged as a transformative technology in this landscape, enabling comprehensive genomic profiling that guides targeted therapeutic interventions. This technical review examines the current global cancer epidemiology, details the experimental frameworks and clinical applications of precision diagnostics, and explores the emerging trends and persistent challenges in implementing these advanced technologies across diverse healthcare systems. The integration of NGS into routine oncology practice represents a critical pathway to mitigating the growing cancer burden through earlier detection, personalized treatment strategies, and improved survival outcomes.

The Escalating Global Cancer Burden

Current Epidemiology and Projections

Current global cancer statistics reveal a substantial and growing health challenge worldwide. In 2022, there were an estimated 20 million new cancer cases and 9.7 million cancer deaths globally, with approximately 53.5 million people living within five years of a cancer diagnosis [26]. The burden is unevenly distributed, with striking disparities based on socioeconomic development levels as measured by the Human Development Index (HDI).

Table 1: Global Cancer Incidence and Mortality for Major Cancer Types (2022)

| Cancer Type | New Cases | Percentage of Total Cases | Deaths | Percentage of Total Deaths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | 2.5 million | 12.4% | 1.8 million | 18.7% |

| Female Breast | 2.3 million | 11.6% | 670,000 | 6.9% |

| Colorectal | 1.9 million | 9.6% | 900,000 | 9.3% |

| Prostate | 1.5 million | 7.3% | - | - |

| Stomach | 970,000 | 4.9% | 660,000 | 6.8% |

| Liver | - | - | 760,000 | 7.8% |

Projections for 2050 indicate a dramatic 77% increase in global cancer incidence, with an estimated 35 million new cases anticipated [26]. This growth reflects both population aging and growth, alongside changes in exposure to risk factors. The proportional increase in incidence is most striking in low HDI countries (142% increase) and medium HDI countries (99%), highlighting the disproportionate future burden on healthcare systems with the fewest resources.

In the United States, the American Cancer Society projects 2,041,910 new cancer cases and 618,120 cancer deaths to occur in 2025 [27]. While cancer mortality rates have continued to decline through 2022, averting nearly 4.5 million deaths since 1991, alarming disparities persist. Native American people bear the highest cancer mortality, including rates that are two to three times those in White people for kidney, liver, stomach, and cervical cancers [27].

Disparities in Cancer Burden and Care Delivery

Significant inequities in cancer burden and access to services exist across the development spectrum. For breast cancer, women in countries with a very high HDI have a 1 in 12 lifetime risk of diagnosis, with 1 in 71 dying from the disease. In contrast, women in low HDI countries have only a 1 in 27 lifetime risk of diagnosis but a 1 in 48 chance of dying from it [26]. This disparity underscores how women in lower HDI countries are 50% less likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer yet face a much higher risk of mortality due to late diagnosis and inadequate access to quality treatment.

A WHO survey of 115 countries examining universal health coverage for cancer reveals major inequalities in service availability [26]. Only 39% of participating countries covered the basics of cancer management as part of their financed core health services for all citizens. Lung cancer-related services were 4-7 times more likely to be included in health benefit packages in high-income versus lower-income countries. The most significant disparity was observed in stem-cell transplantation, which was 12 times more likely to be covered in high-income countries [26].

Foundations of Precision Diagnostics in Oncology

Next-Generation Sequencing Technologies

Next-generation sequencing has revolutionized molecular diagnostics by enabling comprehensive genomic profiling of tumors. NGS employs massively parallel sequencing architecture that allows simultaneous analysis of millions of DNA fragments, a fundamental advancement over traditional Sanger sequencing which processes only one DNA fragment at a time [9]. This high-throughput capacity enables concurrent evaluation of hundreds to thousands of genes in a single assay, providing a complete genomic landscape rather than the fragmented approach inherent to earlier technologies.

Table 2: Comparison of Genomic Analysis Technologies

| Aspect | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Single DNA fragment at a time | Massively parallel; millions of fragments simultaneously |

| Sensitivity (Detection Limit) | Low (~15-20%) | High (down to 1% for low-frequency variants) |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Cost-effective for 1-20 targets | Cost-effective for high sample volumes/many targets |

| Discovery Power | Limited; interrogates a gene of interest | High; detects novel or rare variants with deep sequencing |

| Variant Detection Capability | Limited to specific regions | Single-base resolution; detects SNPs, indels, CNVs, and structural variants |

| Primary Use | Validation of NGS results, single gene analysis | Comprehensive genomic profiling, discovery, and large-scale studies |

The major NGS platforms include Illumina sequencing, which dominates second-generation NGS with exceptionally high throughput and low error rates (typically 0.1-0.6%), and third-generation technologies such as Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) and Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) [9]. Illumina uses sequencing-by-synthesis chemistry, enabling millions of DNA fragments to be sequenced in parallel on a flow cell, producing short reads (75-300 bp) that provide high coverage and precision suitable for variant calling. ONT has introduced a distinctive approach with nanopore sequencing that directly reads single DNA molecules as they traverse a protein nanopore, enabling long-read sequencing capabilities.

Experimental Frameworks for Genomic Profiling

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling (CGP)

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling represents a significant advancement in molecular diagnostics, leveraging NGS technologies to analyze a broad array of genetic alterations across multiple genes in a single, efficient test [28]. CGP offers advantages over traditional methods by requiring smaller tissue samples and reducing the time needed to test for various biomarkers. Enhancements to CGP, such as RNA fusion assays and liquid biopsies, extend its capabilities beyond genomic DNA analyses, enabling identification of gene fusions and splicing variants that provide a more complete picture of a tumor's genetic landscape.

The typical CGP workflow involves several critical steps: nucleic acid extraction from tumor tissue or liquid biopsy samples, library preparation through either amplification-based or hybrid capture-based target enrichment, sequencing on NGS platforms, bioinformatic analysis for variant calling and annotation, and clinical interpretation using curated knowledgebases [28] [29]. This integrated approach allows for simultaneous assessment of multiple biomarker classes including single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions/deletions (indels), copy number variations (CNVs), gene fusions, tumor mutational burden (TMB), and microsatellite instability (MSI) status.

Liquid Biopsy and Circulating Tumor DNA Analysis

Liquid biopsy refers to the non-invasive analysis of tumor-derived material, such as circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), circulating tumor cells (CTCs), RNA, and exosomes present in bodily fluids like blood, urine, or cerebrospinal fluid [28]. This approach offers a dynamic snapshot of cancer's genetic landscape, enabling real-time assessment of tumor evolution, resistance mechanisms, and treatment efficacy. The variability in ctDNA levels across cancer types is critical for understanding its utility as a biomarker. ctDNA is detected in more than 75% of patients with advanced stages of pancreatic, colorectal, gastroesophageal, hepatocellular, bladder, ovarian, breast, head & neck cancers, or melanoma, but is less frequent (fewer than 50% of cases) in patients with primary brain, prostate, thyroid, and renal cancers [28].

Figure 1: Liquid Biopsy and ctDNA Analysis Workflow

Variant Allele Frequency (VAF) in ctDNA has emerged as a promising biomarker with significant clinical applications [28]. VAF measures genetic variation that can be assessed from both genomic (DNA) and transcriptomic (RNA) sequencing data as the encoded and expressed allele frequencies, respectively. This metric provides insights into tumor burden, treatment efficacy, and the dynamics of tumor evolution and resistance mechanisms, serving as a surrogate for mutation clonality and a tool to evaluate genomic heterogeneity.

Clinical Implementation and Therapeutic Impact

Matching Therapies to Genomic Alterations

The fundamental goal of precision oncology is to match patients with therapies that target the specific molecular alterations driving their cancer. Several studies have demonstrated the utility of this approach. In Tsimberidou et al.'s Phase I study, advanced cancer patients given treatment matched to their tumor mutations showed significantly improved overall response rate (27% vs. 5%), time to treatment failure (median of 5.2 vs. 2.2 months), and survival (median of 13.4 vs. 9.0 months) compared to patients who did not receive sequencing-matched therapy [30]. Similarly, Radovich et al. reported that progression-free survival of patients with treatments matched to their DNA mutations, copy number variations, or mRNA levels was significantly higher than that of patients receiving non-matched therapy (86 vs. 49 days) [30].

The National Cancer Institute's Molecular Analysis for Therapy Choice (NCI-MATCH) trial represents one of the most ambitious precision medicine initiatives, using NGS to screen patients for actionable mutations and assigning targeted therapies based on these molecular alterations regardless of tumor histology [29]. This basket trial approach has demonstrated that matching therapies to genomic alterations can yield clinical benefits across multiple cancer types, supporting the histology-agnostic use of targeted agents.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Precision Oncology

| Reagent/Category | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Hybrid Capture Probes | Enrich specific genomic regions by hybridization | Provide greater library complexity and uniformity; suitable for DNA and RNA templates for fusion detection |

| Amplification Primers | PCR-based enrichment of specific genomic regions | Lower input requirement and faster turn-around times; uses RNA template for fusion identification |

| Cell-free DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of ctDNA from liquid biopsy samples | Critical for liquid biopsy applications; yield and purity affect downstream analysis sensitivity |

| NGS Library Preparation Kits | Prepare nucleic acids for sequencing | Include fragmentation, end-repair, adapter ligation, and amplification steps; impact library complexity |

| Matched Germline DNA | DNA from peripheral blood mononuclear cells | Allows unequivocal assignment of variants as somatic versus germline; enables accurate TMB calculation |

| Tumor Enrichment Tools | Macro- or microdissection tools | Enrich tumor cellularity to at least 20% to mitigate false negative results in variant calling |

Variant Interpretation and Reporting Frameworks

A significant challenge in clinical NGS implementation is the annotation and clinical interpretation of identified variants. For single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertions/deletions (indels), many laboratories use a "hotspot"-based approach to identify actionable variants at recurrent positions known from databases like the Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) to definitively affect protein function [29]. Activating alterations in oncogenes such as EGFRL858R, BRAFV600E, and KRASG12D are well suited to this approach.

To supplement hotspot-based approaches, clinical NGS assays use analysis pipelines that identify alterations predicted to result in protein truncation through termination codons or frameshift mutations. Such alterations in tumor suppressor genes are generally considered deleterious. However, interpreting missense alterations remains challenging, with in silico prediction algorithms like SIFT and PolyPhen having limited specificity [29].

Guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of cancer-related variants were published in 2017 by a joint working group of the Association of Molecular Pathology (AMP), American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), and College of American Pathologists (CAP) [29]. These guidelines establish standards for variant classification, clinical actionability assessment, and report content. Additionally, curated knowledgebases including OncoKB, MyCancerGenome, CIViC, and Cancer Genome Interpreter provide "levels of evidence" to support targeted therapy use for specific variants.

Figure 2: Variant Interpretation and Clinical Reporting Pipeline

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

Advanced Technologies Shaping Precision Oncology

The field of precision oncology continues to evolve with several emerging technologies enhancing diagnostic capabilities:

Single-Cell Multiomics: Single-cell sequencing technologies can reveal the specific effect of individual cellular components, overcoming limitations of bulk methods that mask cellular differences [31]. Since the first report of single-cell genome-wide mRNA sequencing in 2009, various methods have been developed including single-cell DNA sequencing, single-cell DNA methylome sequencing, single-cell ATAC-seq, single-cell proteomics, and single-cell metabolomics. The emerging trend is to integrate multimodal omics data within single cells to generate a holistic picture of cellular processes.

Spatial Transcriptomics and Multiomics: These technologies preserve the spatial context of cellular interactions within tissues, providing critical insights into tumor microenvironment heterogeneity and cellular ecosystems that drive cancer progression and therapy resistance [31].

Artificial Intelligence in Biomarker Discovery: AI and machine learning algorithms are being deployed to analyze complex multi-omics datasets, identify novel biomarkers, predict treatment responses, and optimize clinical trial designs [32]. For instance, ConcertAI reported that its AI-powered platform screened oncology patients for trial eligibility more than three times faster than manual review without loss of accuracy [32].

Ultra-Rapid Whole Genome Sequencing: Advances in sequencing technologies have dramatically reduced turnaround times. A landmark study demonstrated that a cloud-distributed nanopore sequencing workflow could deliver a genetic diagnosis in just 7 hours and 18 minutes, enabling timely diagnoses in critically ill patients [32].

Implementation Challenges and Barriers

Despite the demonstrated benefits of precision diagnostics, significant challenges remain in widespread clinical implementation:

Economic and Access Barriers: The cost-benefit balance and widespread accessibility present major hurdles, particularly in low- and middle-income countries [28]. Concerns about how NGS can be properly implemented for all cancer patients remain substantial, with issues of tissue sample quality and preservation, and health technology assessment frameworks varying across healthcare systems.

Interpretative Challenges: Variants of uncertain significance (VUS) pose ongoing difficulties in clinical decision-making [9]. The absence of standardized interpretation frameworks across laboratories can lead to inconsistent reporting and treatment recommendations. Additionally, the determination of "actionable mutations" lacks universal standards, with different laboratories and studies applying varying criteria [30].

Regulatory and Reimbursement Landscape: The regulatory environment for NGS tests continues to evolve, with reimbursement remaining a subject of continuing debate [29]. While a clearer regulatory path has emerged, disparities in insurance coverage for NGS testing and sequencing-matched therapies create inequities in patient access.

Clinical Trial Access: Even when actionable mutations are identified, access to matched therapies remains challenging. Data from Japan indicate that while 44% of patients are recommended new forms of therapy following comprehensive genomic profiling testing, fewer than 10% actually receive these recommended treatments [28]. This gap between molecular identification and treatment delivery represents a critical implementation challenge.

The growing global cancer burden, projected to reach 35 million new cases annually by 2050, demands transformative approaches to cancer diagnosis and treatment. Precision diagnostics, anchored by next-generation sequencing technologies, represents a paradigm shift from histology-based to genomics-driven cancer care. The integration of comprehensive genomic profiling, liquid biopsies, and advanced computational analysis enables matching of targeted therapies to individual molecular alterations, improving patient outcomes.

However, realizing the full potential of precision oncology requires addressing significant implementation challenges, including economic barriers, interpretative standardization, and equitable access across diverse healthcare settings. Emerging technologies such as single-cell multiomics, spatial transcriptomics, and artificial intelligence promise to further refine diagnostic precision. The continued evolution of precision diagnostics offers the most promising pathway to mitigating the escalating global cancer burden through earlier detection, personalized treatment strategies, and improved survival outcomes across all populations.

Cancer is fundamentally a genetic disease driven by the accumulation of genomic alterations that enable uncontrolled cell growth and proliferation. The comprehensive characterization of these alterations has become a cornerstone of precision oncology, enabling molecularly driven cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection [3] [33]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized this field by providing powerful tools to detect diverse genomic variants across entire cancer genomes, transcriptomes, and epigenomes [33]. These technologies have revealed that cancer genomes harbor several major classes of genomic alterations, each with distinct biological consequences and clinical implications. The most significant categories include single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions and deletions (Indels), copy number variations (CNVs), and structural variants (SVs) [34]. Understanding the nature, detection methods, and functional impact of these variant classes is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working to advance cancer therapeutics and diagnostic approaches within the framework of precision medicine.

Classification and Definitions of Genomic Alterations

Genomic alterations in cancer span orders of magnitude in size and complexity, from single nucleotide changes to massive chromosomal rearrangements. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of the four major variant classes discussed in this whitepaper.

Table 1: Classification of Key Genomic Alterations in Cancer

| Variant Type | Size Range | Molecular Consequence | Detection Methods | Clinical/Research Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNPs (Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms) | Single base pair | Base substitution | NGS, Sanger sequencing | Driver mutations, therapeutic targets, prognostic markers [33] |

| Indels (Insertions/Deletions) | 1-50 bp | Frameshift or in-frame alteration | NGS, PCR-based methods | Gene disruption, altered protein function [35] |

| CNVs (Copy Number Variations) | >1 kb | Gene dosage changes (gains/losses) | SNP arrays, NGS, CMA | Oncogene amplification, tumor suppressor loss [36] [37] |

| Structural Variants | >50 bp | Chromosomal rearrangements | Karyotyping, FISH, OGM, NGS | Gene fusions, chromothripsis, complex rearrangements [38] [34] |

Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) and Small Insertions/Deletions (Indels)

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) represent the smallest type of genetic variation, involving the substitution of a single nucleotide at a specific genomic position. In cancer, somatic SNPs can act as driver mutations that directly promote tumorigenesis by activating oncogenes or inactivating tumor suppressor genes [35]. Insertions and deletions (Indels), typically defined as variations involving fewer than 50 base pairs, can cause frameshift mutations that disrupt the reading frame of protein-coding genes, leading to truncated or nonfunctional proteins [35]. Both SNPs and Indels are considered "small variants" and are frequently detected using targeted NGS panels, whole exome sequencing, or whole genome sequencing approaches [13]. The identification of specific SNPs and Indels has become crucial for therapeutic decision-making, as exemplified by mutations in genes such as EGFR, KRAS, and BRAF, which now have matched targeted therapies [33] [13].

Copy Number Variations (CNVs) and Structural Variants (SVs)

Copy number variations (CNVs) are defined as DNA segments larger than 1 kilobase that exhibit variable copy number compared to a reference genome [36]. In cancer, CNVs typically manifest as amplifications (gains) of oncogenes or deletions (losses) of tumor suppressor genes, leading to altered gene dosage that promotes malignant growth [37]. For example, MYCN amplification in neuroblastoma is a well-established marker of aggressive disease and poor prognosis [37].

Structural variants (SVs) encompass larger genomic rearrangements (typically >50 bp) that alter the chromosomal architecture, including translocations, inversions, insertions, and complex rearrangements [34]. Balanced SVs (e.g., inversions, translocations) do not change copy number but can create novel gene fusions or disrupt regulatory elements, while unbalanced SVs result in copy number changes [34]. Catastrophic one-step genomic events such as chromothripsis (chromosomal shattering) and chromoplexy (interconnected rearrangements) represent particularly complex SVs that can drive rapid genomic evolution in cancer [38] [34]. These complex rearrangements have been identified across cancer subtypes and are associated with aggressive tumor behavior [38].

Detection Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The accurate detection of genomic alterations requires sophisticated technologies and carefully optimized experimental protocols. The evolution of these methods has progressively enhanced our ability to resolve increasingly complex variants.

Next-Generation Sequencing Approaches

Next-generation sequencing has become the cornerstone technology for comprehensive genomic profiling in cancer research and clinical diagnostics [3] [33]. The fundamental NGS workflow involves: (1) library preparation through fragmentation of genomic DNA and adapter ligation; (2) cluster generation and parallel sequencing using sequencing-by-synthesis chemistry; and (3) bioinformatic analysis of the resulting reads through alignment to reference genomes and variant calling [3]. Different NGS approaches provide complementary advantages: whole-genome sequencing (WGS) enables genome-wide detection of all variant types; whole-exome sequencing (WES) focuses on protein-coding regions; and targeted panels allow deep sequencing of clinically relevant genes with lower costs and faster turnaround times [3] [37] [13].

Table 2: Comparison of Major NGS Platforms and Their Applications in Oncology

| Platform/Technology | Sequencing Chemistry | Read Length | Accuracy | Primary Applications in Oncology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Sequencing-by-synthesis | Short-read (75-300 bp) | Q30 (99.9%) | SNV/Indel detection, CNV analysis, gene expression profiling [33] |

| Element AVITI | Avidite Base Chemistry | Short-read | Q40 (99.99%) | Rare variant detection, liquid biopsy, low-frequency mutation calling [39] |

| Pacific Biosciences | Single-molecule real-time (SMRT) | Long-read | ~Q20-Q30 | Structural variant detection, phased variants, complex regions [33] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Nanopore sensing | Long-read | ~Q20-Q30 | Structural variant detection, real-time sequencing [33] |

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for NGS-based detection of genomic alterations in cancer research:

Advanced Methods for Structural Variant Detection

While short-read NGS platforms excel at detecting SNPs and small Indels, more specialized approaches are often required for comprehensive structural variant detection. Optical Genome Mapping (OGM) has emerged as a powerful cytogenomic technology that visualizes ultra-long DNA molecules labeled at specific sequence motifs, providing a genome-wide view of large-scale structural changes with resolution down to approximately 500 bp [38]. OGM can detect translocations, inversions, insertions, deletions, duplications, and complex rearrangements such as chromothripsis without the need for cell culture, offering superior resolution compared to traditional cytogenetic methods [38].

For the detection of copy number variations, the Parliament2 pipeline provides a consensus approach that integrates multiple bioinformatics tools (CNVnator, Lumpy, and Delly) to improve detection accuracy from whole-genome sequencing data [36]. This multi-tool strategy helps reduce false positives and enhances the reliability of SV calling, which is particularly valuable for detecting CNVs in complex cancer genomes.

The following workflow illustrates the integrated approach for structural variant detection using multiple technologies:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The experimental workflows for genomic alteration analysis depend on specialized reagents and laboratory materials that ensure sample quality and analytical precision. The following table catalogues key research reagents and their applications in cancer genomics studies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Genomic Alteration Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Manufacturer/Example | Function in Workflow | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen) | Isolation of high-quality DNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue | DNA concentration >20 ng/μL, A260/A280 ratio 1.7-2.2 [13] |

| DNA Quantification Assays | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Invitrogen) | Fluorometric quantification of double-stranded DNA | More accurate for NGS than spectrophotometric methods [13] |

| Library Prep Kits | Agilent SureSelectXT Target Enrichment | Target enrichment via hybrid capture for targeted sequencing | Compatible with Illumina platforms, enables custom panel design [13] |

| NGS Library QC | Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit | Assessment of library fragment size distribution | Optimal size range: 250-400 bp [13] |

| Direct Labeling Enzyme | DLE-1 (Bionano) | Sequence-specific fluorescent labeling for OGM | Labels at CTTAAG motifs for optical mapping [38] |

| UHMW DNA Isolation | Bionano Prep SP BMA DNA Isolation | Isolation of ultra-high molecular weight DNA for OGM | Critical for long DNA fragments (>150 kbp N50) [38] |

Functional Impact and Clinical Applications in Precision Oncology

Genomic alterations drive oncogenesis through diverse mechanisms that disrupt normal cellular functions. Understanding these functional consequences is essential for translating genomic findings into clinical applications.

Biological Consequences of Genomic Alterations

The functional impact of genomic alterations in cancer spans multiple levels of cellular organization. SNPs and Indels can directly alter protein function by introducing amino acid substitutions, creating premature stop codons, or causing frameshifts that disrupt protein structure [35]. These changes can lead to constitutive activation of oncogenic signaling pathways or inactivation of tumor suppressor genes. CNVs affect gene dosage, potentially leading to overexpression of oncogenes through amplification or loss of tumor suppressor function through heterozygous or homozygous deletions [36] [37].

Structural variants can have particularly complex consequences, including the creation of novel gene fusion events that generate chimeric proteins with oncogenic properties, such as the BCR-ABL1 fusion in chronic myeloid leukemia [34]. SVs can also disrupt the three-dimensional organization of the genome by altering topologically associating domains (TADs), leading to inappropriate gene regulation through the repositioning of enhancers and other regulatory elements [34]. Catastrophic events like chromothripsis can cause massive genomic rearrangements that simultaneously affect dozens of genes, driving rapid tumor evolution [38] [34].

Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Targeting

The identification of genomic alterations has become fundamental to precision oncology, enabling molecularly guided treatment strategies. Several key applications include:

Therapeutic Target Identification: Specific genomic alterations serve as direct targets for matched therapies, such as EGFR inhibitors for EGFR-mutant lung cancer or PARP inhibitors for tumors with homologous recombination deficiencies [33] [13].

Diagnostic and Prognostic Biomarkers: Certain genomic alterations provide critical diagnostic information (e.g., gene fusions defining specific sarcoma subtypes) or prognostic information (e.g., MYCN amplification in neuroblastoma) that guides clinical management [37] [13].

Immunotherapy Biomarkers: Tumor mutational burden (TMB) and microsatellite instability (MSI) status, both derived from NGS profiling, help identify patients most likely to benefit from immune checkpoint inhibitors [13].