Next-Generation Sequencing in Immuno-Oncology: Unlocking Biomarker Discovery for Precision Cancer Therapies

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) is revolutionizing biomarker discovery in immuno-oncology.

Next-Generation Sequencing in Immuno-Oncology: Unlocking Biomarker Discovery for Precision Cancer Therapies

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) is revolutionizing biomarker discovery in immuno-oncology. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational role of NGS in identifying critical biomarkers like tumor mutational burden (TMB) and neoantigens. The scope spans from core technological principles and multi-omics methodologies to practical challenges in assay optimization, clinical validation frameworks, and comparative analysis of emerging platforms. By synthesizing current strategies and future directions, this resource aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to advance personalized cancer immunotherapy.

The Core Biomarker Landscape: How NGS is Redefining Immuno-Oncology Targets

The advent of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) has revolutionized oncology by leveraging the host immune system to combat tumors, yet these therapies elicit beneficial responses only in a subset of patients [1] [2]. This reality has driven the urgent need for robust predictive biomarkers to guide patient selection and optimize therapeutic outcomes. Biomarkers serve as critical biological indicators that can forecast patient responsiveness to specific immunotherapeutic agents, thereby significantly enhancing the precision and efficacy of treatment [1]. In the contemporary landscape of immuno-oncology, four biomarkers have emerged as particularly actionable: Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB), Neoantigens, Microsatellite Instability (MSI), and Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) [1] [3] [4]. The integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies has been instrumental in discovering and validating these biomarkers, enabling a comprehensive molecular profiling approach that transcends traditional single-analyte tests [3] [5]. This technical guide delineates the biological mechanisms, assessment methodologies, clinical applications, and experimental protocols for these core biomarkers within the context of NGS-driven immuno-oncology research.

Biomarker Fundamentals and Biological Mechanisms

Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB)

Definition and Biological Rationale: Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) is defined as the total number of somatic non-synonymous mutations within a tumor's genome, typically reported as mutations per megabase (mut/Mb) [1] [4]. The fundamental premise of TMB as a biomarker rests on the correlation between a higher mutational load and an increased likelihood of generating immunogenic neoantigens—novel peptides that can be recognized as "non-self" by the immune system, particularly T cells [1] [4]. When a tumor accumulates a high number of mutations, the probability increases that some of these alterations will be processed and presented on Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) molecules, enabling immune recognition and attack [4]. TMB exhibits dramatic variation across tumor types, with melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and squamous carcinomas typically demonstrating the highest levels, while leukemias and pediatric tumors show the lowest [4]. This variation reflects differing etiologies and mutagen exposures, such as UV light in melanoma and tobacco carcinogens in NSCLC [4].

Neoantigens

Definition and Sources: Neoantigens are tumor-specific peptides derived from somatic mutations that are entirely absent in the normal germline genome [1] [6]. These antigens arise from various genetic alterations, with the primary sources being:

- Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs): Point mutations that change a single amino acid; the most extensively studied source [6] [7].

- Insertions and Deletions (INDELs): These can cause frameshift mutations, generating novel open reading frames (ORFs) and producing peptides with lower similarity to self-proteins, often conferring higher immunogenicity potential compared to SNV-derived peptides [7].

- Gene Fusions: Chimeric proteins resulting from chromosomal rearrangements that can generate entirely new amino acid sequences with high immunogenicity [7].

- Structural Variations (SVs): Large genomic alterations involving more than 50 base pairs that can fuse distinct gene regions, creating novel gene fragments [7].

The significance of neoantigens lies in their high tumor specificity, which minimizes the risk of off-target toxicity and central immune tolerance, making them ideal targets for personalized immunotherapies such as cancer vaccines and adoptive T-cell therapies [1] [6].

Microsatellite Instability (MSI)

Definition and Underlying Mechanism: Microsatellites are short, repetitive DNA sequences (1-6 nucleotide motifs repeated multiple times) scattered throughout the genome that have a higher inherent mutation rate than other regions [3]. Microsatellite Instability (MSI) occurs when the DNA mismatch repair (MMR) system is deficient (dMMR), failing to correct errors that accumulate during DNA replication in these repetitive regions [3]. This failure results in somatic changes in the length of microsatellites and a hypermutatable tumor phenotype [3]. The widespread genomic instability associated with dMMR leads to a rapid accumulation of somatic mutations, particularly insertions and deletions, which can inactivate genes in key regulatory processes and drive tumorigenesis [3]. MSI-high (MSI-H) status is determined based on the number of unstable markers in a standardized panel, with changes in two or more of the five Bethesda-recommended markers classifying a tumor as MSI-H [3].

Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1)

Function in Immune Evasion: Programmed Death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) is a cell surface protein expressed on tumor cells and immune cells that binds to its receptor PD-1 on T cells [2]. This ligand-receptor interaction transmits an inhibitory signal that effectively deactivates T cells, reducing their cytotoxic response and enabling tumors to evade immune surveillance—a mechanism known as immune checkpoint activation [2] [4]. PD-L1 expression has been established as a predictive biomarker for response to anti-PD-1/PD-L1 therapies, with its detection via immunohistochemistry (IHC) serving as an FDA-approved companion diagnostic for several cancer types [4]. However, its utility is limited by heterogeneous and dynamic expression patterns, diagnostic reproducibility challenges, and insufficient negative predictive value, driving the need for complementary biomarkers like TMB and MSI [4].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Actionable Immuno-Oncology Biomarkers

| Biomarker | Molecular Nature | Primary Source | Key Biological Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMB | Quantitative measure of non-synonymous somatic mutations | DNA-level alterations from various mutagenic processes | Proxy for neoantigen load; indicator of tumor immunogenicity |

| Neoantigens | Tumor-specific peptides presented by MHC molecules | Somatic mutations (SNVs, INDELs, fusions, SVs) | Direct targets for T-cell recognition and attack |

| MSI | Genomic hypermutability phenotype | Deficient DNA mismatch repair (dMMR) | Genome-wide indicator of high frameshift mutation burden |

| PD-L1 | Transmembrane immune checkpoint protein | Induced by inflammatory signals (e.g., IFN-γ) in TME | Suppresses T-cell activity; mediates immune evasion |

Assessment Methodologies and NGS Workflows

NGS-Based Approaches for TMB Measurement

The initial gold standard for TMB assessment was whole exome sequencing (WES), which comprehensively profiles protein-coding regions and identifies non-synonymous mutations [2] [4]. However, due to cost and analytical constraints in routine clinical practice, targeted NGS panels have been developed as a practical alternative [2]. The accuracy of TMB estimation with targeted panels is highly dependent on panel size, with research indicating that panels between 1.5 Mb and 3 Mb provide optimal performance with significantly smaller confidence intervals compared to smaller panels [2]. The wet-lab protocol for TMB assessment typically involves:

- DNA Extraction: High-quality DNA is extracted from matched tumor and normal tissues.

- Library Preparation: Sequencing libraries are prepared from both tumor and normal DNA samples.

- Hybrid Capture: For targeted panels, biotinylated probes hybridize to and enrich the genomic regions of interest.

- Sequencing: High-throughput sequencing is performed on NGS platforms.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Sequencing data is processed through an analytical pipeline including:

- Alignment to reference genome (e.g., using BWA)

- Variant calling (somatic mutations)

- Filtering to remove germline polymorphisms

- TMB calculation: (Total non-synonymous mutations / Size of targeted region in Mb)

Critical considerations include the inclusion of both synonymous and non-synonymous mutations in targeted panels to improve sensitivity, and rigorous calibration to ensure TMB scores are comparable across different platforms [2] [4].

Integrated Neoantigen Prediction Pipeline

Neoantigen discovery requires a multi-faceted approach that integrates genomic, transcriptomic, and immunopeptidomic data [1] [6] [7]. The comprehensive workflow involves both wet-lab and computational components:

Wet-Lab Components:

- DNA/RNA Sequencing: WES or WGS on tumor-normal pairs, complemented by RNA-Seq to assess expression of mutant genes [6].

- HLA Typing: Determination of patient-specific HLA alleles using tools like HLAminer or Athlates [6].

- Immunopeptidomics: Isolation of MHC-bound peptides from tumor cells followed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to directly identify presented peptides [6].

Computational Pipeline:

- Mutation Identification: Somatic variant calling from sequencing data using tools like BWA and Genome Modeling System; annotation with Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) [6].

- Neoantigen Candidate Generation: Translation of genomic mutations into mutated protein sequences [6].

- MHC Binding Prediction: Prediction of peptide-MHC binding affinity using algorithms such as NetMHCpan, NetMHCIIpan, MixMHCpred2.2, or PRIME2.0 [1] [6].

- Immunogenicity Assessment: Evaluation of T-cell recognition potential based on predicted binding, expression levels, and sequence similarity to self-proteins [6].

- Prioritization: Ranking of candidates using integrated pipelines like pVAC-Seq, TSNAD, CloudNeo, or TIminer [6].

Advanced models are increasingly incorporating deep learning trained directly on mass spectrometry data (e.g., EDGE model) to improve prediction accuracy of genuinely presented neoantigens [6].

MSI Detection via NGS

While traditional MSI testing follows the Bethesda guidelines using capillary electrophoresis of five microsatellite markers, NGS-based approaches offer significant advantages, including higher throughput, greater reproducibility, and the ability to analyze hundreds to thousands of microsatellites simultaneously [3]. The NGS workflow for MSI assessment includes:

- Library Preparation: DNA libraries are prepared from tumor tissue.

- Sequencing: Targeted, whole exome, or whole genome sequencing is performed.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Microsatellite loci are identified from sequencing data.

- Length variation is assessed by comparing tumor and normal profiles.

- MSI scoring is calculated based on the percentage of unstable loci.

- Classification: Tumors are classified as MSI-High (MSI-H), MSI-Low (MSI-L), or Microsatellite Stable (MSS) based on the scoring threshold [3].

The expanded number of markers in NGS-based assays provides a more quantitative and granular assessment of MSI status, improving sensitivity for detecting MMR deficiency across diverse cancer types [3]. Comprehensive genomic profiling panels can simultaneously assess MSI, TMB, and specific gene alterations, offering a holistic molecular characterization [2].

PD-L1 Expression Analysis

PD-L1 expression is primarily assessed through immunohistochemistry (IHC) using specific antibodies, with scoring systems that vary by assay and cancer type [8] [4]. Key methodologies include:

- IHC Staining: Formalinfixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections are stained with anti-PD-L1 antibodies.

- Scoring Systems: Evaluation based on tumor proportion score (TPS) or combined positive score (CPS), which incorporate staining of tumor and immune cells.

- Digital Pathology: Emerging computational approaches for more standardized quantification.

While not primarily an NGS-based biomarker, transcriptomic profiling via RNA sequencing can provide complementary information on PD-L1 mRNA expression and the broader immune contexture of the tumor microenvironment [8].

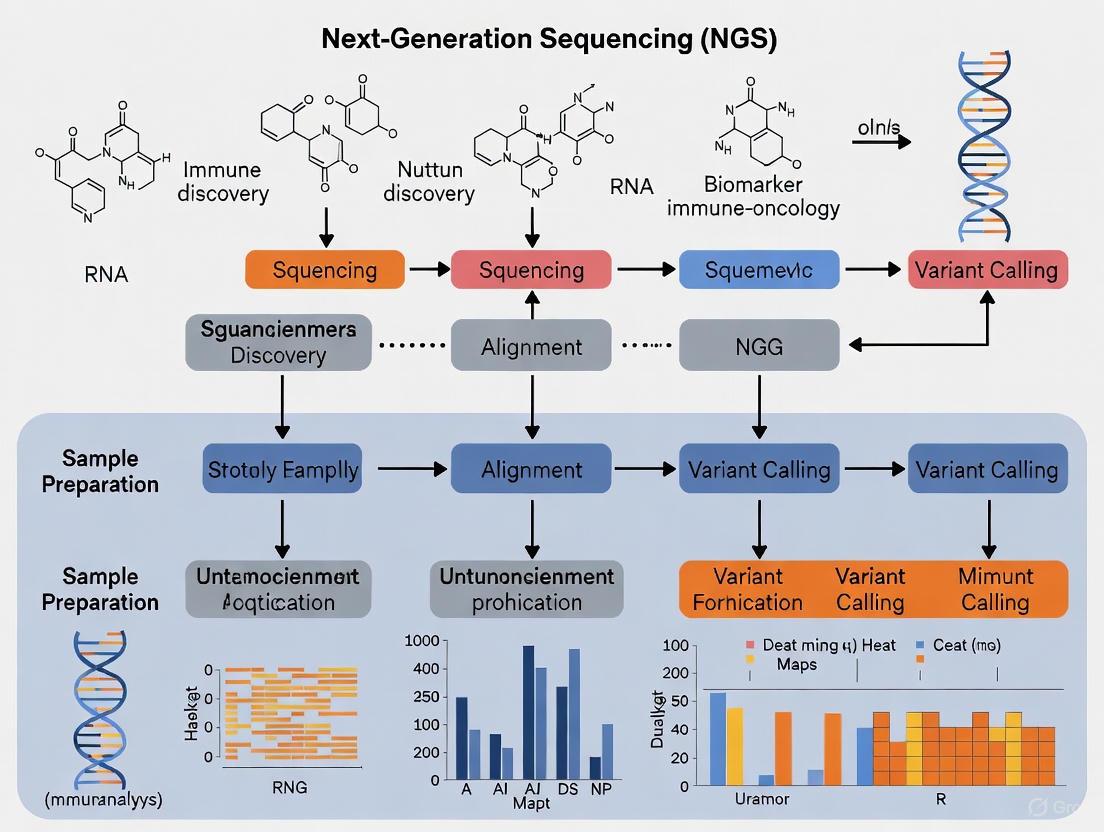

Diagram 1: NGS Workflow for Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Discovery. This diagram illustrates the integrated computational pipeline for biomarker assessment from multi-omics data inputs to clinical applications, highlighting how NGS enables comprehensive profiling.

Quantitative Data and Clinical Validation

TMB Thresholds and Clinical Outcomes

Clinical evidence has established TMB as a predictive biomarker for response to immune checkpoint inhibitors across multiple cancer types [4]. The KEYNOTE-158 trial validated TMB as a biomarker for pembrolizumab treatment across solid tumors, leading to FDA approval [5]. Proposed TMB thresholds vary by cancer type and detection method, with WES-based thresholds for lung, bladder, and head and neck cancers approximating 200 non-synonymous somatic mutations (approximately 10-20 mut/Mb depending on the coding region size) [4]. In a pan-cancer analysis, a TMB cutoff of ≥10 mutations/Mb has been used to define TMB-high (TMB-H) status for targeted NGS panels [8]. Clinical trial data has demonstrated that NSCLC patients with high TMB experienced significantly longer progression-free survival when receiving immunotherapy [2].

Table 2: TMB Thresholds and Clinical Associations Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Proposed TMB Threshold (mut/Mb) | Associated Clinical Outcome | Level of Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma | Varies; among highest | Improved survival with anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 | Retrospective studies [4] |

| NSCLC | ~10-20 (WES equivalent) | Significantly longer PFS with ICIs | Prospective trials [2] [4] |

| Colon Cancer | Context dependent | Sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade | Clinical trials [2] |

| Multiple Solid Tumors | ≥10 (targeted NGS) | Objective response to pembrolizumab | Prospective trial (KEYNOTE-158) [5] |

MSI Prevalence and Therapeutic Implications

MSI-H/dMMR status represents the first tissue-agnostic biomarker approved for ICIs, with the FDA granting approval for PD-1 inhibitors regardless of cancer type [3]. The prevalence of MSI-H varies across cancers, with highest rates observed in colorectal (15%), gastric (22%), and endometrial (20-30%) cancers, while being rare in other malignancies [3]. The seminal study by Le et al. demonstrated that MMR-deficient colorectal cancers were highly sensitive to PD-1 blockade, with immune-related objective response rates of 40% and immune-related complete response rates of 10% [3]. Follow-up research on the NCI-MATCH Arm Z1D trial further validated that even within a dMMR population, NGS-based measures of microsatellite instability could serve as biomarkers of immunotherapy response, with more extensive MSI alterations associated with clinical benefit and TMB [9].

PD-L1 Expression and Predictive Value

PD-L1 expression remains an important biomarker with validated predictive value in multiple cancer types, though with limitations as a standalone biomarker [8] [4]. In a comprehensive study of anal squamous-cell carcinoma (ASCC), 64.25% of tumors expressed PD-L1, with 41.7% exhibiting high expression [8]. The PD-L1-high group treated with ICIs had significantly longer time on treatment than the PD-L1-negative group (HR 0.758, 95% CI 0.579-0.992, P = 0.044) [8]. PD-L1 expression is influenced by the tumor immune microenvironment, with PD-L1-high ASCCs showing higher infiltration of Tregs, M1 macrophages, neutrophils, CD8+ T cells, and cancer-associated fibroblasts compared to PD-L1-low tumors [8].

Integrative Biomarker Analysis

The most powerful approach for predicting immunotherapy response involves integrating multiple biomarkers [1] [2]. Research in colorectal cancer has demonstrated that combining MSI and TMB determination may better identify patients with a more active immune response [2]. Each biomarker provides complementary information:

- TMB quantifies the potential antigenic repertoire

- Neoantigens represent the actual immunogenic targets

- MSI indicates a specific hypermutational mechanism

- PD-L1 reflects an activated but suppressed immune microenvironment

This integrative approach enables more precise patient stratification and insights into resistance mechanisms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Biomarker Discovery

| Tool Category | Specific Technologies/Assays | Research Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | WES, WGS, RNA-Seq, Targeted Panels | Comprehensive mutation profiling, TMB calculation, fusion detection | High-throughput, multi-analyte capability, scalable [1] [6] |

| Computational Tools | NetMHCpan, NetMHCIIpan, pVAC-Seq, TSNAD | Neoantigen prediction, MHC binding affinity estimation | Algorithmic prediction, integration of multi-omics data [1] [6] [7] |

| Immunopeptidomics | LC-MS/MS, MHC immunoprecipitation | Direct identification of presented peptides | Validation of neoantigen presentation, complement to prediction algorithms [1] [6] |

| IHC Assays | PD-L1 IHC (multiple clones) | Protein expression analysis, immune cell profiling | Spatial context, protein-level verification, standardized scoring [8] [4] |

| Multi-omics Databases | TCGA, CPTAC, DriverDBv4, GliomaDB | Data integration, biomarker validation, cross-study analysis | Annotated datasets, normalized processing, clinical correlations [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Assessment

Comprehensive TMB and MSI Analysis via Targeted NGS Panel

Sample Requirements: FFPE tumor tissue with matched normal (blood or tissue), minimum 20% tumor content, DNA quantity ≥50ng.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- DNA Extraction: Use commercial extraction kits following manufacturer's protocols. Assess DNA quality and quantity via fluorometry.

- Library Preparation: Fragment DNA, followed by end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation. Use dual-indexed adapters for sample multiplexing.

- Hybrid Capture: Incubate libraries with biotinylated probes targeting the panel regions (ensure panel size ≥1.5Mb for TMB accuracy). Perform washing to remove non-specific binding.

- Sequencing: Amplify captured libraries and sequence on Illumina platform (minimum 100x coverage recommended).

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Alignment: Map sequencing reads to reference genome (hg38) using BWA-MEM.

- Variant Calling: Identify somatic mutations using paired tumor-normal variant callers (MuTect2 for SNVs, other specialized tools for INDELs).

- TMB Calculation: (Total non-synonymous somatic mutations / Panel size in Mb)

- MSI Analysis: Compare microsatellite loci in tumor vs normal using specialized tools (e.g., mSINGS, MSIsensor). Calculate percentage of unstable loci.

- Interpretation: Classify TMB-H per validated thresholds (e.g., ≥10 mut/Mb); classify MSI status based on predefined scoring thresholds.

Quality Control Metrics: Include positive and negative controls; monitor sequencing metrics (coverage uniformity, on-target rate); validate with reference materials.

Integrated Neoantigen Discovery Workflow

Sample Requirements: Matched tumor-normal DNA/RNA from fresh-frozen or high-quality FFPE tissue; viable tumor cells for immunopeptidomics.

Multi-Omics Protocol:

- Genomic Profiling:

- Perform WES on tumor-normal pairs (minimum 100x tumor, 40x normal coverage).

- Conduct RNA-Seq on tumor tissue to assess gene expression.

- Determine HLA type using specialized tools (HLAminer, OptiType).

- Variant Calling and Annotation:

- Identify somatic mutations using established pipelines.

- Annotate variants with functional impact (VEP, SnpEff).

- Filter for expressed mutations (FPKM ≥1 in RNA-Seq).

- Neoantigen Prediction:

- Generate mutant peptide sequences (typically 8-11mers).

- Predict MHC binding affinity using algorithms (NetMHCpan, MixMHCpred).

- Prioritize candidates based on binding affinity (IC50 <50nM considered strong binders), expression level, and clonality.

- Experimental Validation (Immunopeptidomics):

- Isolate MHC-peptide complexes from tumor cells by immunoprecipitation.

- Elute and fractionate peptides by liquid chromatography.

- Analyze by tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

- Identify peptides by searching spectra against customized databases including mutant sequences.

- Immunogenicity Assay:

- Synthesize candidate neoantigen peptides.

- Isolate peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patient.

- Stimulate T-cells with peptide-pulsed antigen-presenting cells.

- Measure T-cell activation (ELISpot, intracellular cytokine staining).

- Expand reactive T-cell clones for functional validation.

Diagram 2: Biomarker Interplay in Immune Activation. This diagram illustrates the mechanistic relationships between genomic instability, neoantigen formation, T-cell recognition, and PD-L1-mediated immune regulation, explaining the biological foundation for biomarker synergy in predicting ICI response.

The integration of TMB, neoantigens, MSI, and PD-L1 represents a paradigm shift in immuno-oncology research and clinical practice. These biomarkers provide complementary information that collectively enables more precise patient stratification for immunotherapy [1] [2]. The continued evolution of NGS technologies and multi-omics integration is further refining our understanding of these biomarkers and their interactions [5]. Emerging frontiers include single-cell and spatial multi-omics technologies that resolve tumor heterogeneity at unprecedented resolution, artificial intelligence approaches that enhance neoantigen prediction accuracy, and the development of organoid and humanized models that better recapitulate human tumor-immune interactions [5] [10]. Liquid biopsy approaches for non-invasive TMB and MSI monitoring are also advancing rapidly, offering dynamic assessment of biomarker evolution during treatment [1]. As these technologies mature, the biomarker framework outlined in this guide will continue to evolve, driving further refinement of personalized immuno-oncology and expanding the benefit of immunotherapy to broader patient populations.

The Biological Mechanism of Neoantigens and TCR Recognition

Neoantigens are tumor-specific proteins arising from somatic mutations in cancer cells. These antigens are proteolytically processed and presented on the tumor cell surface by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, forming peptide-MHC (pMHC) complexes that can be recognized by T cell receptors (TCRs). This interaction represents a critical mechanism for immune-mediated tumor elimination and forms the foundation for numerous immuno-oncology approaches. The identification of neoantigens has become crucial for advancing cancer vaccines, diagnostics, and immunotherapies, with next-generation sequencing (NGS) playing an increasingly vital role in biomarker discovery for precision oncology [11] [12].

The TCR-pMHC interaction initiates anti-tumor immunity, leading to T cell activation, proliferation, and ultimately, tumor cell cytolysis. Understanding the structural and cellular determinants controlling TCR recognition of neoantigens remains a fundamental challenge in immunology, particularly given the intricate binding motifs and long-tail distribution of known binding pairs in public databases [11]. This technical guide explores the biological mechanisms underlying neoantigen formation, TCR recognition, and the integration of NGS technologies to advance biomarker discovery in immuno-oncology research.

Biological Mechanisms of Neoantigen Formation and Presentation

Origins and Classification of Neoantigens

Neoantigens originate from various genetic alterations that generate novel protein sequences not present in normal tissues:

- Missense mutations: Single nucleotide variants resulting in amino acid substitutions that create novel peptide sequences. For example, the recurrent driver mutation KRAS Q61H generates the neoantigen ILDTAGHEEY presented by HLA-A*01:01 [13].

- Frameshift mutations: Insertions or deletions that alter the reading frame, producing completely novel amino acid sequences.

- RNA splicing alterations: Cancer-specific splicing events (neojunctions) that create novel transcript variants. Recent research has identified that these neojunctions can be conserved across tumor types, with studies showing an average of 94 public neojunctions per TCGA tumor type, and 38.3% of these being translated into neopeptides verified by mass spectrometry [14].

- Genomic rearrangements: Structural variants that create fusion proteins with novel junctional epitopes.

Neoantigens can be categorized based on their structural characteristics and immunogenic properties. Group I neoantigens contain mutations in non-anchor residues and often show some cross-reactivity with wild-type peptides. In contrast, Group II neoantigens feature mutations at anchor residues that enhance MHC binding affinity and stabilize the pMHC complex, resulting in minimal cross-reactivity with wild-type peptides and resembling non-self epitopes typically generated during viral infections [15].

MHC Presentation and TCR Recognition Mechanisms

The presentation of neoantigens follows the standard antigen processing pathway. Intracellular proteins are degraded by the proteasome, transported to the endoplasmic reticulum, loaded onto MHC-I molecules, and presented on the cell surface for recognition by CD8+ T cells. The structural basis for TCR recognition of neoantigens involves highly specific molecular interactions between the TCR complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) and the pMHC complex.

Structural studies have revealed that neoantigen-specific TCRs often exhibit high functional avidity and selectivity, attributable to broad, stringent binding interfaces that enable recognition of tumor cells despite low antigen density [15]. For instance, research on the H2-Db/Hsf2 p.K72N68-76 neoantigen system demonstrated that the p.K72N mutation enhances H2-Db binding, improves cell surface presentation, and stabilizes the TCR epitope, enabling recognition by its cognate TCR (47BE7) with sub-nanomolar functional avidity (EC50 5.61 pM) [15].

Table 1: Characteristics of Neoantigen Types and Their Recognition Properties

| Neoantigen Type | Origin | MHC Binding Affinity | Cross-reactivity with WT | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group I (Non-Anchor Mutations) | Missense mutations at non-anchor residues | Variable, often similar to WT | Moderate to high | Various private neoantigens |

| Group II (Anchor Mutations) | Missense mutations at anchor residues | Typically enhanced compared to WT | Minimal | Hsf2 p.K72N68-76 [15] |

| RNA Splicing-derived | Cancer-specific splicing events (neojunctions) | Dependent on peptide sequence | None (truly tumor-specific) | NeoARPL22, NeoAGNAS [14] |

| Oncogenic Driver-derived | Mutations in canonical oncogenes | Variable | Minimal to none | KRAS Q61H [13] |

Computational Prediction of Neoantigens and TCR Interactions

Advanced Algorithmic Approaches

Accurate prediction of pMHC binding and TCR recognition remains a significant computational challenge in immunology due to the complexity of binding motifs and the limited availability of training data. Recent advances in machine learning have led to the development of sophisticated prediction tools:

- Attention-aware differential learning: Novel frameworks like TranspMHC (for pMHC-I binding prediction) and TransTCR (for TCR-pMHC-I recognition prediction) leverage attention mechanisms to surpass existing algorithms on independent datasets at both pan-specific and allele-specific levels [11].

- Transfer learning and differential learning: TransTCR incorporates these strategies to demonstrate superior performance and enhanced generalization on independent datasets compared to existing methods [11].

- Structural affinity modeling: Approaches that incorporate molecular dynamics and structural information to predict TCR-pMHC binding affinity.

These computational tools help identify key amino acids associated with binding motifs of peptides and TCRs that facilitate pMHC-I and TCR-pMHC-I binding, indicating potential interpretability of the prediction frameworks [11].

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Neoantigen and TCR Prediction Platforms

| Platform/Method | Prediction Target | Key Advantages | Validation Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| TranspMHC [11] | pMHC-I binding | Attention mechanism, pan-specific and allele-specific prediction | Surpasses existing algorithms on independent datasets |

| TransTCR [11] | TCR-pMHC-I recognition | Transfer learning, differential learning strategy | Superior performance and generalization on independent datasets |

| NetMHCpan (v.4.1) [15] | Peptide-MHC binding | Wide HLA allele coverage, established performance | Used in identification of immunogenic neoantigens in B16F10 model |

| Antigen-agnostic TCR identification [13] | Tumor-specific TCRs | Comparative TCR repertoire profiling | Confirmed tumor reactivity in 3/3 validated patients |

Figure 1: Computational Workflow for Neoantigen and TCR Prediction

Experimental Methods for Validating Neoantigen-TCR Interactions

Antigen-Agnostic TCR Discovery Approach

A novel antigen-agnostic method identifies tumor-specific T-cell clonotypes by comparative high-throughput TCR repertoire profiling of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and adjacent normal tissue-resident lymphocytes from surgical specimens [13]. This approach involves:

- TCRβ-chain repertoire sequencing: High-resolution sequencing of TCR repertoires from matched tumor and normal tissues.

- Clonotype selection criteria: Identification of candidate tumor-specific clonotypes based on TIL abundance and high tumor-to-nontumor frequency ratios.

- Single-cell RNA sequencing validation: Verification of tumor-specific clonotypes through gene expression signatures determined by scRNA-Seq.

- Functional validation: Testing predicted tumor-specific clonotypes for reactivity against autologous tumors.

This method successfully identified tumor-reactive TCRs in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients, with selection validated in six of seven patients analyzed through scRNA-Seq, and experimental confirmation that predicted tumor-specific clonotypes reacted against autologous tumors in three patients [13].

TCR Functional Characterization Protocols

Comprehensive validation of neoantigen-specific TCRs requires multiple experimental approaches:

- Tetramer staining: Using pMHC tetramers to confirm direct binding between TCRs and their cognate pMHC complexes.

- Cellular activation assays: Measuring T cell activation markers (CD137, CD69) and cytokine production (IFN-γ, IL-2) following exposure to antigen-presenting cells pulsed with candidate neoantigen peptides.

- Cytotoxicity assays: Assessing the ability of TCR-engineered T cells to lyse tumor cells endogenously expressing the target neoantigen.

- Alaninescanning mutagenesis: Systematically replacing each residue in the neoantigen peptide with alanine to identify TCR contact residues and assess potential cross-reactivity with wild-type peptides [14].

For the KRAS Q61H-specific TCRs, researchers demonstrated that TCR-transduced T cells showed specific reactivity against HLA-matched NSCLC cell lines endogenously expressing the mutation, and cytotoxicity was partially blocked by HLA-I blockade, confirming TCR-mediated recognition [13].

Structural Biology Techniques

Understanding the molecular basis of TCR recognition requires structural biology approaches:

- X-ray crystallography: High-resolution structures of TCR-pMHC complexes provide atomic-level details of interaction interfaces. For example, structural studies of the TCR 47BE7 bound to H2-Db/Hsf2 p.K72N revealed how anchor-residue modifications create neoantigens that are discriminated at both MHC and TCR levels [15].

- Surface plasmon resonance (SPR): Quantitative measurement of binding kinetics and affinity between TCRs and pMHC complexes.

- Cryo-electron microscopy: Particularly useful for studying complex immune synapses and dynamic interactions.

These structural approaches have demonstrated that neoantigen-reactive TCRs often exhibit broad, stringent binding interfaces that enable high functional avidity and selectivity for mutant peptides over their wild-type counterparts [15].

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for TCR Validation

NGS Integration in Neoantigen and TCR Research

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling for Neoantigen Discovery

Next-generation sequencing technologies have revolutionized neoantigen discovery by enabling comprehensive characterization of the tumor mutational landscape:

- Whole exome sequencing (WES): Identifies protein-altering mutations across the entire coding genome. Paired sequencing of tumor and normal tissues enables identification of somatic mutations.

- RNA sequencing: Determines mutation expression levels and identifies novel transcripts, fusion genes, and splicing variants. Studies have shown that RNA sequencing can identify cancer-specific splicing events (neojunctions) that serve as sources of shared neoantigens [14].

- Single-cell RNA sequencing: Enables simultaneous analysis of TCR sequences and transcriptional states in individual T cells, allowing identification of tumor-reactive T cell clones based on activation and exhaustion markers.

The integration of these NGS approaches provides a comprehensive view of the neoantigen landscape, informing the selection of candidate antigens for experimental validation and therapeutic development.

Automated NGS Workflows for Biomarker Discovery

Recent advancements in NGS workflow automation have significantly improved the efficiency and reproducibility of neoantigen discovery:

- Integrated automation solutions: Partnerships between companies like Integrated DNA Technologies and Hamilton Company provide complete automation-friendly solutions for NGS workflows on liquid handling systems, accelerating biomarker discovery [16].

- Rapid targeted sequencing panels: Technologies like Pillar Biosciences' oncoReveal panels enable rapid, localized NGS testing for somatic mutations, with validation studies demonstrating effective detection of actionable biomarkers in liquid biopsy samples from non-small cell lung cancer and breast cancer [17].

- Standardized bioinformatics pipelines: Robust computational workflows for variant calling, transcriptomic profiling, and neoantigen prediction from NGS data.

These technological advances make comprehensive genomic profiling more accessible and implementable in clinical research settings, supporting the broader integration of precision oncology approaches.

Table 3: NGS Applications in Neoantigen and TCR Research

| NGS Application | Technical Approach | Research Utility | Clinical Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Exome Sequencing | Sequencing of all protein-coding regions | Comprehensive mutation discovery | Identifying patient-specific mutations for personalized vaccines |

| RNA Sequencing | Transcriptome-wide sequencing | Determination of mutation expression, fusion genes, splicing variants | Selection of expressed neoantigens |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq | Cell-level resolution transcriptomics | TCR sequence pairing with T cell functional states | Identification of tumor-reactive TCR clonotypes |

| TCR Repertoire Sequencing | High-throughput TCR CDR3 sequencing | Monitoring of T cell clonal dynamics | Tracking therapeutic TCR persistence |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for Neoantigen and TCR Research

| Research Tool | Type | Function/Application | Example Platforms/Assays |

|---|---|---|---|

| NGS Library Prep Kits | Laboratory reagents | Preparation of sequencing libraries for genomic and transcriptomic profiling | IDT xGen, Archer [16] |

| Automated Liquid Handling | Laboratory equipment | Standardization and scaling of NGS workflows | Hamilton Microlab STAR, NIMBUS [16] |

| Targeted NGS Panels | Custom assay | Focused sequencing of cancer-related genes | Pillar oncoReveal panels [17] |

| pMHC Tetramers | Biochemical reagents | Detection and isolation of antigen-specific T cells | Custom tetramer production |

| TCR Reconstruction Systems | Molecular biology tools | Cloning and expression of candidate TCRs | Retroviral/Lentiviral vectors, TCR-null Jurkat76 cells [13] [14] |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq Platforms | Instrumentation | Simultaneous analysis of gene expression and TCR sequence | 10X Genomics, Smart-seq2 |

| Cytokine Release Assays | Functional assays | Measurement of T cell activation | ELISpot, intracellular cytokine staining |

Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Applications

TCR-Based Adoptive Cell Therapies

The ultimate application of neoantigen and TCR research lies in developing effective cancer immunotherapies. Adoptive cell therapy (ACT) with TCR-engineered T cells represents a promising approach for treating advanced solid cancers [13]. Key considerations for clinical translation include:

- Target selection: Prioritizing clonal, truncal mutations that are expressed homogeneously across tumor lesions. Oncogenic driver mutations like KRAS Q61H are ideal targets due to their essential role in tumorigenesis and stable expression [13].

- TCR safety profiling: Comprehensive screening for off-target reactivity against normal tissues using methods like alanine scanning mutagenesis and screening against primary human cells.

- Manufacturing optimization: Developing robust processes for TCR gene transfer, T cell expansion, and quality control.

Notably, the discovery of highly homologous or identical TCRs across multiple patients with shared HLA types and mutations enables development of "off-the-shelf" TCR therapies targeting public neoantigens, potentially overcoming the personalized nature of most neoantigen-directed approaches [13].

Clinical Impact of NGS-Guided Therapies

Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the significant clinical impact of NGS-guided targeted therapies. In advanced cancer patients who had progressed after prior systemic therapy, NGS-guided matched targeted therapies (MTTs) were associated with:

- 30-40% reduction in the risk of disease progression

- Improved overall survival when MTTs were combined with standard of care, particularly in prostate and urothelial cancers

- PFS gains without OS improvement in breast and ovarian cancers when MTTs were combined with standard of care [12]

These findings support the routine integration of genomic profiling into the management of patients with advanced or recurrent cancers and highlight the importance of neoantigen and TCR research in advancing precision oncology.

The biological mechanism of neoantigens and TCR recognition represents a rapidly advancing field with significant implications for cancer immunotherapy. Advances in NGS technologies, computational prediction tools, and experimental validation methods have accelerated the discovery and characterization of tumor-specific antigens and their cognate TCRs. The integration of comprehensive genomic profiling, automated workflows, and sophisticated functional assays enables the identification of optimal targets for TCR-based therapies. As these technologies continue to evolve, they promise to enhance the precision and effectiveness of cancer immunotherapies, ultimately improving outcomes for cancer patients.

NGS Applications in Decoding the Tumor Microenvironment (TME)

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a complex ecosystem comprising cancer cells, immune cells, stromal cells, blood vessels, and extracellular matrix, which collectively influence tumor progression and therapeutic response [18]. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized our ability to deconvolute this complexity by providing high-throughput, cost-effective methods for analyzing DNA and RNA molecules at unprecedented resolution [19]. The application of NGS in immuno-oncology has been particularly transformative, enabling the discovery of predictive biomarkers and characterization of the immune components within the TME that were previously obscured by bulk sequencing approaches [18] [5].

In personalized oncology, understanding the TME is crucial for predicting patient responses to immunotherapies, such as immune checkpoint inhibitors, adoptive cell therapies, and cancer vaccines [5] [18]. Multi-omics strategies that integrate genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics have revealed that the functional state and spatial distribution of TME components, rather than their mere presence or absence, serve as critical determinants of therapeutic efficacy and resistance mechanisms [5] [10].

NGS Technological Platforms for TME Analysis

Various NGS platforms offer complementary strengths for TME interrogation, ranging from short-read technologies that provide high accuracy to long-read technologies that resolve complex genomic regions and full-length transcripts.

Table 1: Comparison of NGS Platforms for TME Analysis

| Platform | Technology | Read Length | Key Applications in TME | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Sequencing-by-synthesis | 36-300 bp [19] | High-throughput transcriptomics (RNA-seq), whole exome sequencing, epigenomics [19] | Potential signal overcrowding with error rates up to 1% [19] |

| Ion Torrent | Semiconductor sequencing | 200-400 bp [19] | Targeted immuno-oncology panels (TCR/BCR profiling, TMB) [20] | Homopolymer sequence errors [19] |

| PacBio SMRT | Single-molecule real-time sequencing | 10,000-25,000 bp [19] | Full-length transcript sequencing for immune receptor characterization | Higher cost per sample [19] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Nanopore sensing | 10,000-30,000 bp [19] | Real-time RNA sequencing, epitranscriptomics in immune cells | Error rates up to 15% [19] |

The versatility of these platforms has facilitated the development of specialized assays specifically designed for immuno-oncology research. For example, the Oncomine TCR Beta-SR Assay enables characterization of the immune status and detection of T-cell minimal residual disease by specifically interrogating the CDR3 region of the TCR beta chain, while the Oncomine Tumor Mutation Load Assay covers 409 cancer-related genes to quantify tumor mutational burden (TMB), an independent predictor for patient stratification for response to immunotherapy [20].

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing for TME Deconvolution

Methodological Approaches

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has emerged as a powerful tool for deciphering the cellular heterogeneity of the TME at unprecedented resolution [18]. The technology can be broadly categorized into three methodological approaches:

- Plate-based methods (e.g., SMART-Seq2): These involve sorting individual cells into separate wells via fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), providing full-length transcript coverage and enabling index-sorting for protein expression quantification [18].

- Droplet-based methods (e.g., 10X Chromium, Drop-seq): These use microfluidics to capture single cells with barcode-carrying beads into droplets, allowing high-throughput processing of thousands of cells at relatively low cost but restricted to either 3' or 5' end sequencing [18].

- Combinatorial barcoding methods (e.g., SPLiT-seq, Sci-RNA-seq): These bypass physical isolation of single cells by using combinatorial barcoding, enabling fixation of cells and mitigating batch effects in longitudinal studies [18].

Experimental Protocol for scRNA-seq

A standardized workflow for scRNA-seq analysis of the TME typically involves the following steps:

- Sample Preparation: Fresh tumor tissues are dissociated into single-cell suspensions using enzymatic digestion (e.g., collagenase, dispase) with viability typically >90% [18].

- Cell Capture: Depending on the chosen platform, 500-10,000 cells are loaded onto microfluidic devices or sorted into multiwell plates [18].

- Library Preparation: This includes cell lysis, reverse transcription with cell-specific barcodes and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), cDNA amplification, and library construction with platform-specific reagents [18].

- Sequencing: Libraries are sequenced on appropriate NGS platforms (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq for droplet-based methods) with recommended read depths of 20,000-100,000 reads per cell [18].

- Computational Analysis: Data processing includes alignment (to GRCh38 or mm10 genomes), UMI counting, quality control, normalization, clustering, and cell type annotation using reference databases [18].

Diagram: scRNA-seq Workflow for TME Analysis

Key Insights from scRNA-seq Studies

Application of scRNA-seq to various cancer types has yielded fundamental insights into TME biology. In breast carcinoma, a study profiling over 45,000 cells revealed increased heterogeneity of gene expression in intratumoral lymphoid and myeloid cells compared to normal breast tissue, reflecting adaptation to diverse environmental signals within the TME [18]. In malignant glioma, scRNA-seq demonstrated that conventional subtype distinctions are primarily accounted for by differences in non-malignant cell types within the TME, highlighting the importance of comprehensive immune profiling beyond cancer cell-intrinsic classification [18].

Spatial Transcriptomics and Multi-Omics Integration

Spatial Biology Technologies

While scRNA-seq provides detailed cellular taxonomy, it loses critical spatial context. Spatial transcriptomics and multiplex immunohistochemistry (IHC) have emerged to address this limitation by enabling in situ analysis of gene and protein expression while preserving tissue architecture [10]. These technologies allow researchers to study the TME without altering spatial relationships between cells, providing crucial information about physical proximity, cellular organization, and interaction patterns that serve as important biomarkers themselves [10].

Studies suggest that the distribution of spatial interactions, rather than simple presence or absence of specific cells, can significantly impact therapeutic response [10]. For instance, the physical distance between cytotoxic T cells and cancer cells, or the organization of immunosuppressive macrophages around tumor nests, may serve as more accurate predictors of immunotherapy efficacy than bulk expression signatures.

Multi-Omics Integration Strategies

The integration of spatial data with other molecular layers through multi-omics approaches provides a comprehensive framework for understanding cancer biology and discovering clinically actionable biomarkers [5]. Multi-omics integration can be achieved through:

- Horizontal Integration: Combining similar data types across different samples or conditions to identify consistent patterns [5].

- Vertical Integration: Combining different molecular data types (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) from the same samples to derive systems-level insights [5].

Advanced computational approaches, including machine learning and deep learning, are essential for integrating these complex datasets and extracting biologically meaningful signatures [5] [10]. For example, AI-powered platforms like BostonGene's multi-omics platform integrate genomic, transcriptomic, immune, and spatial profiling data to deliver a multidimensional view of disease biology, enabling improved patient stratification and trial design [21].

Table 2: Multi-Omics Data Types for Comprehensive TME Analysis

| Omics Layer | Technology | Key Information | Clinical Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Whole exome sequencing (WES) | Somatic mutations, copy number variations, TMB [5] | FDA approval of TMB as biomarker for pembrolizumab [5] |

| Transcriptomics | RNA-seq, scRNA-seq | Gene expression signatures, immune cell composition [5] | Oncotype DX (21-gene) for breast cancer chemotherapy decisions [5] |

| Proteomics | Mass spectrometry, reverse-phase protein arrays | Protein abundance, post-translational modifications [5] | CPTAC studies revealing functional subtypes in ovarian and breast cancers [5] |

| Epigenomics | Whole genome bisulfite sequencing, ChIP-seq | DNA methylation, histone modifications [5] | MGMT promoter methylation predicting temozolomide benefit in glioblastoma [5] |

| Metabolomics | LC-MS, gas chromatography-MS | Cellular metabolites, metabolic pathway activity [5] | 2-hydroxyglutarate as diagnostic biomarker in IDH-mutant gliomas [5] |

Diagram: Multi-omics Integration Framework for TME Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for TME NGS Analysis

| Category | Product/Platform | Key Features | Application in TME Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| TCR Profiling | Oncomine TCR Beta-LR Assay [20] | Long-read sequencing for CDR1, CDR2, CDR3 regions; 10 ng RNA input | Predictive biomarker discovery, T cell characterization, variable gene polymorphism identification |

| BCR Profiling | Oncomine BCR IgH SR Assay [20] | CDR3 region interrogation from FFPE tissue; identifies somatic hypermutations | Study of clonal evolution, isotype abundance, measurable residual disease monitoring |

| Immune Monitoring | Oncomine Immune Response Research Assay [20] | Carefully selected gene panel to monitor tumor microenvironment | Biomarker identification, mechanism of action studies, combination therapy experiments |

| Tumor Mutational Burden | Oncomine Tumor Mutation Load Assay [20] | Covers 1.7 Mb across 409 genes; correlates with exome mutation counts | TMB quantification for immunotherapy patient stratification |

| Computational Analysis | ngs.plot [22] | Standalone program to visualize enrichment patterns of DNA-interacting proteins | Integrative visualization of NGS data at functional genomic regions |

| Single-Cell Analysis | Seurat, Scanpy [18] | R and Python packages for scRNA-seq data normalization and analysis | Cell clustering, trajectory inference, and population characterization in TME |

| Multi-Omics Platform | BostonGene Platform [21] | AI-powered integration of genomic, transcriptomic, immune, and spatial data | Comprehensive TME profiling for patient stratification and clinical trial optimization |

Biomarker Discovery and Clinical Translation

Analytical Workflows for Biomarker Discovery

The biomarker discovery pipeline from NGS data involves sophisticated analytical workflows that transform raw sequencing data into clinically actionable insights. For TME-focused biomarkers, key steps include:

- Quality Control and Preprocessing: Tools like FastQC and MultiQC assess read quality, followed by adapter trimming and alignment to reference genomes using STAR or HISAT2 [22].

- Feature Quantification: Expression quantification (e.g., HTSeq, featureCounts), variant calling (e.g., GATK), or epigenetic feature identification [5].

- TME-Specific Analysis: Immune cell deconvolution (e.g., CIBERSORT, MCP-counter), TCR/BCR repertoire analysis, and spatial neighborhood assessment [18] [10].

- Multi-Omics Integration: Horizontal and vertical integration strategies combine different data types using computational tools specifically designed for multi-omics data [5].

- Biomarker Validation: Cross-validation within datasets and experimental validation using orthogonal methods (e.g., flow cytometry, multiplex IHC) [10].

Clinical Applications and Validation

NGS-derived TME biomarkers have demonstrated significant clinical utility across multiple cancer types. For example, tumor mutational burden (TMB), validated in the KEYNOTE-158 trial, has received FDA approval as a predictive biomarker for pembrolizumab treatment across solid tumors [5]. Similarly, spatial biomarkers that quantify immune cell distribution within the TME have shown promise in predicting response to immunotherapy in clinical studies [10].

The Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) studies of ovarian and breast cancers demonstrated that proteomics can identify functional subtypes and reveal druggable vulnerabilities missed by genomics alone, directly informing the discovery of protein-based biomarkers for predicting therapeutic responses [5]. These approaches are increasingly being incorporated into adaptive clinical trial designs where treatment decisions are modified based on accumulating biomarker data [10].

Next-generation sequencing technologies have fundamentally transformed our ability to decode the complex ecosystem of the tumor microenvironment. Through single-cell RNA sequencing, spatial transcriptomics, and multi-omics integration, researchers can now delineate the cellular composition, functional states, and spatial organization of the TME at unprecedented resolution. These advances have accelerated the discovery of novel biomarkers for immuno-oncology, enabling more precise patient stratification, therapeutic response prediction, and clinical trial optimization. As NGS technologies continue to evolve toward higher throughput, lower costs, and improved integration with artificial intelligence, their impact on personalized cancer care and drug development will undoubtedly expand, ultimately improving outcomes for cancer patients.

Key Genomic Alterations Driving Response to Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy has revolutionized cancer treatment, yet durable responses remain unpredictable, occurring in only a minority of patients. The clinical efficacy of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) is profoundly influenced by the complex interplay between tumor genomic features and the host immune system. This technical review synthesizes current evidence on key genomic alterations that dictate response and resistance to immunotherapy, with emphasis on their discovery through next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies. We examine the predictive value of tumor mutational burden (TMB), neoantigen landscape, specific driver mutations, and microenvironmental factors, providing a comprehensive framework for biomarker discovery in immuno-oncology research and drug development.

The remarkable success of immune checkpoint inhibitors targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) and the programmed cell death 1 (PD-1)/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) axis has transformed therapeutic paradigms across multiple cancer types. However, response rates remain limited, with only 18-38% of advanced solid cancer patients achieving objective responses to single-agent ICIs [23]. This clinical heterogeneity underscores the critical need to identify molecular determinants of treatment outcome.

Immunogenomics represents an emerging field that integrates genomic data with immunologic parameters to decipher the complex tumor-immune interplay. Advances in NGS technologies have enabled comprehensive profiling of somatic alterations, neoantigen landscapes, and immune cell repertoires, revealing distinct genomic features that orchestrate anti-tumor immunity [5]. The convergence of these technologies with immunotherapy clinical trials has accelerated the discovery of predictive biomarkers essential for patient stratification and treatment personalization.

Key Genomic Biomarkers of Immunotherapy Response

Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB) and Neoantigen Landscape

Tumor mutational burden, defined as the total number of non-synonymous mutations per megabase of DNA, has emerged as a quantitative biomarker of immunotherapy response across multiple cancer types. The underlying biological rationale centers on the principle that somatic mutations can generate novel immunogenic peptides (neoantigens) that enable T-cell recognition and targeting of tumor cells [23].

Table 1: Tumor Mutational Burden as a Predictive Biomarker Across Cancers

| Cancer Type | TMB Threshold (mut/Mb) | Predictive Value | Clinical Context | Reference Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melanoma | >100 | OS advantage | Anti-CTLA-4 therapy | [23] |

| NSCLC | Varies (discovery vs validation cohorts) | PFS and response | Anti-PD-1 therapy | [23] |

| Urothelial Carcinoma | Not specified | Significant association | Anti-PD-L1 therapy | [23] |

| Small Cell Lung Cancer | Not specified | Significant association | ICI therapy | [23] |

| Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma | Not specified | Correlation with neoantigen burden | Immunochemotherapy | [24] |

High TMB correlates with increased neoantigen burden, creating a more immunogenic tumor microenvironment. In diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), patients harboring ≥2 BCL2-derived neoantigens exhibit significantly worse overall survival (HR 5.61 for OS) following immunochemotherapy [24]. Beyond single nucleotide variants, non-SNV sources including frameshift mutations, splice variants, and gene fusions can produce more immunogenic neoantigens due to greater sequence divergence from wild-type peptides. For example, frameshift mutations in microsatellite-unstable lymphomas generate 9× more neoantigens per mutation than SNVs [24].

The predictive utility of TMB, however, shows limitations in cancers with low mutation rates, such as pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia (typically <20 mutations/exome), where reduced neoantigen availability limits immunogenicity [24]. Furthermore, the correlation between TMB and immunogenic neoantigen burden is imperfect (Spearman ρ = 0.55–0.56 in DLBCL), as only 1–3% of mutations yield immunogenic epitopes due to HLA-binding constraints and inefficient antigen processing [24].

Specific Genomic Alterations with Immunomodulatory Effects

Beyond quantitative mutational burden, specific genomic alterations in oncogenic pathways can actively shape the tumor immune microenvironment and modulate ICI response.

Table 2: Specific Genomic Alterations Modulating Immunotherapy Response

| Gene/Pathway | Alteration Type | Cancer Context | Effect on Immune Response | Mechanistic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCL2 | Somatic mutations | DLBCL | Poor survival (HR 5.61 for OS) | Neoantigen generation |

| CRMA cluster | Overexpression | Melanoma | Anti-CTLA-4 resistance | Autophagy interference affecting antigen presentation |

| HLA class I | Evolutionary divergence | Pan-cancer | Superior survival with high HED | Diverse immunopeptidomes enhancing tumor surveillance |

| MYC | Activation | Multiple cancers | Immunotherapy non-response | Negative regulation of immune response |

| RAS-like subtype | Transcriptomic signature | Thyroid cancer, SKCM | Lower immune signature scores | Immunosuppressive microenvironment |

| ARID1A | Alterations | Multiple cancers | Predictive for ICI response | Impact on tumor immunogenicity |

The eight-gene "anti-CTLA4 resistance-associated MAGEA" (CRMA) cluster demonstrates how specific gene expression patterns can mediate resistance. In melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab, CRMA expression associates with poor response, potentially through autophagy interference that disrupts antigen processing and presentation [23]. Conversely, ARID1A alterations have emerged as positive predictors of ICI response, potentially through enhancing tumor immunogenicity [25].

Transcriptomic analyses reveal that RAS-like subtypes in both skin cutaneous melanoma (SKCM) and thyroid cancer (THCA) are significantly associated with lower immune signature scores compared to other molecular subtypes, suggesting these tumors create immunosuppressive microenvironments less conducive to ICI response [26]. Similarly, MYC activation has been identified as a negative regulator of immune response, associated with immunotherapy non-response [26].

HLA Diversity and Antigen Presentation Machinery

The host germline genetics, particularly the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) system, plays a crucial role in determining immunotherapy efficacy. HLA class I evolutionary divergence (HED) quantifies physicochemical differences between HLA alleles and predicts ICI efficacy. Patients with high HED (top quartile) exhibit superior survival post-ICI, as divergent alleles present more diverse immunopeptidomes, enhancing tumor surveillance [24]. This effect persists even among fully heterozygous individuals, underscoring HED's role beyond heterozygosity [24].

Allele-specific associations also influence outcomes; for instance, HLA-B*44 supertypes correlate with prolonged survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) due to efficient presentation of leukemia-associated antigens [24]. These findings highlight how germline genetic factors interact with somatic alterations to ultimately determine the effectiveness of anti-tumor immunity.

Biological Mechanisms Linking Genomic Alterations to Immune Response

The relationship between genomic alterations and immunotherapy response operates through multiple interconnected biological mechanisms that collectively shape the tumor-immune microenvironment.

This framework illustrates how genomic features translate through molecular and cellular mechanisms to ultimately determine clinical outcomes to immunotherapy. High TMB increases the probability of generating immunogenic neoantigens that can be recognized by T-cells as non-self, initiating an immune response [23]. Specific driver mutations can activate oncogenic signaling pathways that create an immunosuppressive microenvironment, while defects in antigen presentation machinery can limit the visibility of tumor cells to the immune system [26] [24].

The resulting immune phenotype exists on a spectrum from "immune-hot" tumors characterized by robust T-cell infiltration and activation to "immune-cold" tumors with exclusion of immune effector cells and dominant immunosuppressive signals. Understanding where a patient's tumor falls on this spectrum based on its genomic features enables more accurate prediction of immunotherapy response.

Experimental Approaches for Profiling Immunogenomic Biomarkers

Next-Generation Sequencing Methodologies

Comprehensive genomic profiling for immunotherapy biomarkers primarily utilizes targeted NGS panels, whole exome sequencing (WES), and increasingly, whole genome sequencing (WGS). Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations for biomarker discovery.

Targeted NGS panels (e.g., MSK-IMPACT, FoundationOne) focus on several hundred cancer-related genes with high sequencing depth (typically 500-1000×), enabling sensitive detection of somatic variants down to 5% variant allele frequency [27]. These panels are designed to identify actionable mutations across major variant classes including single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions/deletions (indels), copy number variants (CNVs), and structural rearrangements while conserving limited tissue samples [27]. The high depth of coverage makes targeted approaches particularly suitable for calculating TMB and detecting microsatellite instability (MSI) from limited clinical specimens.

Whole exome sequencing provides broader coverage of protein-coding regions (~1-2% of the genome) but at lower depth (typically 100-200×), resulting in reduced sensitivity for subclonal alterations [27]. While WES enables more comprehensive TMB calculation and neoantigen prediction beyond predefined gene panels, its lower sensitivity and higher DNA input requirements have limited routine clinical adoption compared to targeted approaches.

Whole genome sequencing offers the most comprehensive genomic assessment, covering both coding and non-coding regions, but remains predominantly a research tool due to higher costs, computational demands, and challenges in interpreting non-coding variants.

Immune Signature Profiling

Transcriptomic approaches enable quantification of immune cell populations and functional states within the tumor microenvironment. Bulk RNA sequencing coupled with deconvolution algorithms (CIBERSORT, xCell) can quantify relative abundances of immune cell subsets from complex tissue mixtures [26] [24]. This methodology has delineated "hot" versus "cold" tumor microenvironments, with "hot" TMEs featuring CD8+ effector T-cells and NK cells correlating with response to immunotherapy across multiple cancer types [24].

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) provides higher resolution insights into cellular heterogeneity and functional states. In classical Hodgkin lymphoma, scRNA-seq revealed that responders show CD4+ memory T-cell expansion, while non-responders accumulate immunosuppressive CD163+ macrophages [24]. Similarly, in DLBCL patients receiving CD19-CAR-T therapy, pre-infusion upregulation of exhaustion genes (LAG3, TIM3, TOX, NR4A) in manufactured products associates with poor persistence and disease progression [24].

Algorithmic Approaches for Neoantigen Prediction

Computational pipelines for neoantigen prediction have become increasingly sophisticated, integrating multiple data dimensions to prioritize immunogenic candidates. Modern approaches like INTEGRATE-neo and NetMHCpan incorporate variant allele frequency, gene expression, and mutation clonality alongside HLA binding affinity to identify high-priority neoantigens [24]. These pipelines typically follow a multi-step process: (1) identification of somatic mutations from tumor-normal sequencing pairs; (2) prediction of HLA haplotypes from normal tissue sequencing; (3) in silico prediction of peptide-MHC binding affinity; (4) prioritization based on expression, clonality, and binding strength.

The integration of multi-omics data layers through machine learning approaches has demonstrated improved prediction of immunotherapy response compared to single-parameter biomarkers. For instance, the IS score (immune signature score) developed from gene expression data of patients treated with MAGE-A3 antigen-based immunotherapy successfully separated responders from non-responders with an AUC of 0.83 and also predicted response to anti-CTLA-4 therapy in independent cohorts [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Solutions for Immunogenomics

| Category | Specific Tool/Platform | Application in Immunogenomics | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| NGS Platforms | Illumina sequencing | Targeted panels, WES, WGS | High throughput, low error rates (0.1-0.6%) |

| Oxford Nanopore | Long-read sequencing | Real-time sequencing, structural variant detection | |

| PacBio SMRT sequencing | Long-read sequencing | High-fidelity reads, isoform sequencing | |

| Computational Tools | CIBERSORT/xCell | Immune cell deconvolution | Bulk RNA-seq to immune cell proportions |

| NetMHCpan/INTEGRATE-neo | Neoantigen prediction | HLA binding affinity, immunogenicity | |

| GATK/BWA | Variant calling | SNV, indel, CNV detection | |

| Data Resources | TCGA Pan-Cancer Atlas | Multi-omics reference dataset | 30 tumor types, clinical annotations |

| CPTAC | Proteogenomic datasets | Proteomic-phosphoproteomic integration | |

| CGGA | Glioma-specific database | Multi-omics glioma data | |

| Laboratory Assays | PD-L1 IHC | Protein expression assessment | Companion diagnostic for multiple ICIs |

| Multiplex immunofluorescence | Spatial immune profiling | Tissue context, cell-cell interactions | |

| scRNA-seq | Single-cell transcriptomics | Cellular heterogeneity, rare populations |

Clinical Translation and Trial Design Implications

The discovery of genomic determinants of immunotherapy response has catalyzed the development of novel clinical trial designs that transcend traditional histology-based approaches. Basket trials investigate the efficacy of targeted immunotherapies for molecularly-defined subsets across different tumor histologies [28]. These designs are predicated on the understanding that specific genomic alterations can drive response regardless of tissue of origin.

Umbrella trials represent a complementary approach, evaluating multiple targeted immunotherapies stratified by molecular alterations within a single cancer type [28]. This design enables efficient evaluation of multiple biomarker-drug combinations simultaneously. More recently, platform trials have emerged as adaptive designs that continuously assess several interventions against a control arm, allowing for early termination of ineffective interventions and flexibility in adding new interventions during the trial [28].

Despite these advances, the implementation of biomarker-guided combination therapies remains limited. A comprehensive analysis of clinical trials combining gene-targeted agents with immune checkpoint inhibitors revealed that only 1.3% (4/314) of such trials incorporated biomarkers for both therapeutic modalities [25]. This represents a significant missed opportunity for precision immuno-oncology, particularly as evidence mounts that dual biomarker-matched approaches can yield durable clinical benefit even in heavily pretreated patients [25].

The integration of NGS-based genomic profiling has been instrumental in deciphering the complex relationship between tumor genetics and response to immunotherapy. TMB, specific driver alterations, neoantigen quality, and HLA diversity collectively contribute to a multidimensional framework for predicting ICI outcomes. However, significant challenges remain in standardizing biomarker assessment, validating predictive models across diverse populations, and translating these insights into clinically actionable tools.

Future directions in immunogenomics will likely focus on multi-omics integration, combining genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and spatial data to build more comprehensive predictive models. Artificial intelligence approaches are showing promise in this domain, with systems like SCORPIO and LORIS demonstrating superior performance compared to single-biomarker methods [29]. Additionally, the emergence of single-cell and spatial multi-omics technologies is expanding the scope of biomarker discovery and deepening our understanding of tumor-immune interactions at unprecedented resolution [5].

As the field advances, the successful implementation of precision immuno-oncology will require continued collaboration between researchers, clinicians, and drug developers to ensure that genomic insights are rapidly translated into improved patient outcomes through biomarker-driven clinical trials and treatment strategies.

The integration of multi-omics data—encompassing genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, and other molecular layers—has revolutionized oncology research by providing comprehensive molecular portraits of tumors. This approach is particularly crucial for biomarker discovery in immuno-oncology, where understanding the complex interactions between tumors and the immune system requires analysis across multiple biological dimensions. Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies serve as the foundational engine powering this revolution, enabling high-throughput characterization of the molecular features that influence immunotherapy response and resistance [30] [31]. The convergence of NGS with multi-omics data integration creates unprecedented opportunities to identify predictive biomarkers, discover novel therapeutic targets, and ultimately advance precision immuno-oncology.

Public multi-omics databases provide the essential infrastructure for storing, standardizing, and sharing the vast datasets generated by the research community. These resources have become indispensable for researchers seeking to validate findings, generate hypotheses, and leverage previously generated data to accelerate discovery. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical guide to the major public multi-omics databases and resources, with particular emphasis on their application to NGS-driven biomarker discovery in immuno-oncology research.

Major Public Multi-Omics Databases

The landscape of public cancer databases has expanded significantly, with several flagship projects leading the way in data aggregation, standardization, and dissemination. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of major multi-omics databases relevant to oncology research.

Table 1: Major Public Multi-Omics Databases for Oncology Research

| Database Name | Primary Focus | Key Features | Data Types | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [32] [33] | Pan-cancer molecular characterization | >20,000 primary cancer and matched normal samples across 33 cancer types | Genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, clinical data | Genomic Data Commons (GDC) Data Portal |

| MLOmics [34] | Machine learning-ready multi-omics data | 8,314 patient samples across 32 cancer types with four omics types; preprocessed feature versions | mRNA, miRNA, DNA methylation, copy number variations | Open access database |

| International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC) [32] | Global cancer genomics collaboration | Catalog of 77 million somatic mutations from >20,000 participants across 84 projects | Genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic data | ICGC Data Portal |

| cBioPortal [32] [33] | Visualization and analysis of cancer genomics | User-friendly interface for complex genomic datasets; integration with TCGA and ICGC | Genomic, clinical, and basic protein data | Web interface and API |

| Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) [32] [33] | Functional genomics data repository | MIAME-compliant data submissions; beyond genomics to methylation and chromatin structure | Gene expression, methylation, chromatin structure | Public data download |

| NCI Genomic Data Commons (GDC) [32] | Unified cancer genomic data management | Stores, analyzes, and shares genomic and clinical data; promotes precision medicine | Genomic, transcriptomic, clinical data | GDC Data Portal |

| Human Tumor Atlas Network (HTAN) [33] | 3D tumor atlases | Cancer Moonshot initiative; dynamic cellular, morphological, and molecular features | Multi-omics, spatial, imaging data | HTAN Data Portal |

| ProteomicsDB [33] | Multi-omics and multi-organism resource | Protein-centric interrogation with analytics section | Proteomic, transcriptomic, phenomic data | Web interface |

Beyond these comprehensive resources, specialized databases have emerged to address specific analytical needs. For instance, MLOmics represents a recent innovation specifically designed to serve the machine learning community by providing off-the-shelf, preprocessed multi-omics datasets [34]. This database addresses a critical bottleneck in bioinformatics by providing data in multiple feature versions (Original, Aligned, and Top), with the Top version containing the most significant features selected via ANOVA testing across all samples to filter out potentially noisy genes [34]. Such specialized resources significantly reduce the preprocessing burden on researchers and facilitate more rapid development of predictive models for immunotherapy response.

Standardized Experimental Methodologies

Data Generation Protocols

Robust biomarker discovery requires standardized experimental protocols to ensure data quality and reproducibility. The CIMACs-CIDC Network (Cancer Immune Monitoring and Analysis Centers-Cancer Immunologic Data Center), established by the NCI, provides a exemplary framework for standardized immuno-oncology biomarker analysis [35]. This network has harmonized a core set of assays across multiple leading institutions to reduce data variability and facilitate cross-trial analysis.

Table 2: Standardized Assay Protocols for Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Discovery

| Assay Category | Specific Technologies | Key Applications in Immuno-Oncology |

|---|---|---|

| Tissue Imaging | Multiplex immunofluorescence, Multiplex IHC, MIBI, Spatial transcriptomics (Visium, GeoMx) | Spatial analysis of immune cell infiltration, PD-L1 expression, tumor-immune interactions |

| Immune Cell Profiling | Mass Cytometry (CyTOF), EliSPOT, Single-cell RNA sequencing, CITE-seq | Comprehensive immunophenotyping, functional immune response assessment, T cell activation status |

| Sequencing Assays | RNA-seq, Whole Exome Sequencing, TCR/BCR sequencing, ATAC-seq, ctDNA analysis | Tumor mutational burden, neoantigen prediction, immune repertoire diversity, clonal evolution |

| Soluble Factor Analysis | Olink cytokine analysis, ELISA, NULISA | Systemic immune activation, cytokine profiling, biomarker quantification |