Navigating Bioinformatics Challenges in Clinical NGS: A Roadmap for Robust Implementation in Research and Diagnostics

The integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS) into clinical practice and drug development research is fraught with complex bioinformatics challenges that impact data accuracy, reproducibility, and clinical utility.

Navigating Bioinformatics Challenges in Clinical NGS: A Roadmap for Robust Implementation in Research and Diagnostics

Abstract

The integration of next-generation sequencing (NGS) into clinical practice and drug development research is fraught with complex bioinformatics challenges that impact data accuracy, reproducibility, and clinical utility. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, addressing the foundational, methodological, troubleshooting, and validation hurdles. Drawing on current guidelines and multi-center studies, we outline standardized bioinformatics practices, optimization strategies for scalable workflows, and robust validation frameworks essential for ensuring reliable NGS results in clinical implementation and therapeutic discovery.

The Core Hurdles: Understanding Foundational Bioinformatics Barriers in Clinical NGS

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized clinical diagnostics and public health surveillance, but its implementation faces a critical human resources challenge. Specialized NGS personnel require unique expertise spanning laboratory techniques, bioinformatics, and data interpretation, yet retaining these skilled professionals has become a substantial obstacle for laboratories. Current data indicates that testing personnel in these specialized roles often hold their positions for less than four years on average [1] [2]. Furthermore, a 2021 survey by the Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL) revealed that 30% of surveyed public health laboratory staff indicated an intent to leave the workforce within the next five years [1] [2]. This impending workforce crisis threatens the sustainability and quality of NGS operations in clinical and public health settings, creating vulnerabilities in our public health infrastructure precisely when genomic capabilities are most needed for pandemic preparedness and personalized medicine.

The problem extends beyond mere retention statistics. The specialized knowledge required for NGS operations creates significant hiring and qualification challenges, particularly under regulations such as the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) and state hiring statutes [1] [2]. The combination of high expertise requirements and relatively short tenure creates a perpetual cycle of training and knowledge loss that undermines laboratory efficiency and test reliability. This article examines these workforce challenges within the broader context of bioinformatics challenges in clinical NGS implementation research, providing actionable frameworks and troubleshooting guidance to help institutions address these critical gaps.

Table 1: Statistical Overview of NGS Workforce Challenges

| Metric | Finding | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Average Position Tenure | <4 years for testing personnel | Akkari et al. [1] [2] |

| Projected Workforce Attrition | 30% of public health laboratory staff intend to leave within 5 years | APHL 2021 Survey [1] [2] |

| Primary Retention Barriers | Specialized knowledge requirements, compensation costs, regulatory qualifications | NGS Quality Initiative Assessment [1] [2] |

Tiered Expertise Distribution Framework

NGS operations require diverse expertise distributed across different laboratory levels. The Global Emerging Infections Surveillance (GEIS) program has implemented a tiered framework that illustrates how specialized NGS personnel are distributed across different levels of laboratory operations [3]. This framework is particularly valuable for understanding how expertise gaps at any level can disrupt the entire sequencing workflow.

Diagram 1: NGS Expertise Distribution Across Laboratory Tiers. This framework illustrates how specialized personnel are distributed across different laboratory levels and the specific retention challenges at each tier.

Technical Support Center: NGS Workforce Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions: Workforce and Expertise Gaps

Q1: What are the primary factors contributing to high turnover among specialized NGS personnel?

Multiple factors create retention challenges in the NGS workforce. Specialized NGS personnel require unique expertise that commands competitive compensation, increasing operational costs [1] [2]. The CLIA regulations and state hiring statutes create additional qualification barriers that limit the pool of eligible candidates [1] [2]. Furthermore, the rapid evolution of NGS technologies requires continuous training, creating burnout among personnel who must constantly update their skills while maintaining production workloads. This is particularly challenging in public health laboratories where budget constraints may limit competitive compensation and professional development opportunities.

Q2: How can laboratories document expertise and standardize procedures to mitigate knowledge loss when staff depart?

The Next-Generation Sequencing Quality Initiative (NGS QI) has developed specific tools to address this challenge. Laboratories should implement the "Identifying and Monitoring NGS Key Performance Indicators SOP" and "Bioinformatician Competency Assessment SOP" to objectively document staff capabilities and performance standards [1] [2]. These resources help create standardized benchmarks that survive individual staff transitions. Additionally, the NGS Method Validation Plan and Validation SOP provide templates for consistently documenting laboratory procedures, ensuring that institutional knowledge remains accessible when personnel depart [1] [2]. These tools collectively help laboratories maintain quality standards despite staff turnover.

Q3: What training resources are available for building NGS workforce capabilities?

The NGS QI has published 25 tools specifically for personnel management, including the "Bioinformatics Employee Training SOP" [1] [2]. These resources provide frameworks for structured training programs that can accelerate the development of new staff. Additionally, the GEIS program's tiered framework employs a "train-the-trainer" approach where tier 3 laboratories provide training to tier 2 personnel, who then train tier 1 staff [3]. This cascading training model efficiently distributes expertise across the network while building regional training capabilities. Laboratories should also participate in the online trainings hosted by NGS QI partners to access current best practices [1] [2].

Q4: How do workforce gaps specifically impact NGS quality and operations?

Workforce instability directly impacts NGS quality through several mechanisms. First, inexperienced staff are more likely to make errors during library preparation that lead to sequencing failures, such as inaccurate fragmentation, poor ligation efficiency, or overly aggressive purification [4]. Second, high turnover creates inconsistency in bioinformatic analyses, as different analysts may employ varying methodologies or quality thresholds. Third, the constant need to train new staff diverts resources from quality improvement initiatives. The NGS QI addresses these challenges through its QMS Assessment Tool, which helps laboratories maintain quality standards despite personnel changes [1] [2].

Q5: What strategies help distribute expertise across different laboratory tiers?

The GEIS program's 3-tiered framework provides a model for strategically distributing expertise [3]. In this model, tier 1 laboratories (field/point-of-care) focus on rapid pathogen identification using portable sequencers like the Oxford Nanopore MinION or Illumina iSeq. Tier 2 laboratories (regional support centers) conduct more comprehensive strain-level analysis and serve as regional training hubs. Tier 3 laboratories (core reference labs) perform advanced genetic characterization and develop new methods. This framework ensures that each level maintains appropriate expertise while having clear pathways for technical support and consultation from higher tiers [3].

Workforce-Dependent Technical Issues: Troubleshooting Guide

Table 2: Common NGS Technical Issues Linked to Workforce Experience Gaps

| Technical Problem | Workforce-Related Causes | Corrective Actions | Preventive Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low library yield | Inconsistent sample quantification; Poor technique in purification steps; Inadequate monitoring of reagent quality [4] | Re-purify input samples; Verify quantification with fluorometric methods; Calibrate pipettes [4] | Implement "Bioinformatician Competency Assessment SOP" [1] [2]; Use master mixes to reduce pipetting errors [4] |

| High duplication rates | Overamplification due to inexperience with optimization; Poor quantification leading to excessive PCR cycles [4] | Repeat amplification from leftover ligation product; Optimize PCR cycle number [4] | Standardize protocols using NGS QI templates [1] [2]; Create technician checklists for critical steps [4] |

| Adapter dimer contamination | Improper adapter-to-insert ratios; Inefficient cleanup techniques; Inconsistent size selection [4] | Titrate adapter:insert ratios; Optimize bead-based cleanup parameters [4] | Implement "Identifying and Monitoring NGS Key Performance Indicators SOP" [1] [2]; Use two-step indexing protocols [4] |

| Inconsistent bioinformatic results | High analyst turnover with varying methodologies; Insufficient documentation of analysis parameters; Lack of standardized quality thresholds | Cross-train personnel between wet lab and bioinformatics [3]; Implement version-controlled analysis pipelines | Use "Bioinformatics Employee Training SOP" [1] [2]; Establish clear analysis protocols with tiered review [3] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for NGS Workflows

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Their Functions in NGS workflows

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Workforce Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fragmentation Reagents | Enzymatic fragmentation mixes; Acoustic shearing reagents | Prepare nucleic acids for library construction by reducing fragment size | Inconsistent technique affects fragment distribution; requires trained personnel [4] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Illumina Nextera; ONT Rapid Kits; Element Biosciences AVITI | Convert nucleic acid fragments to sequencing-ready libraries | Commercial kits reduce but don't eliminate expertise requirements [1] [4] |

| Quantification Reagents | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay; qPCR quantification mixes | Accurately measure library concentration for loading calculations | Technique-sensitive; requires consistent training and competency assessment [4] |

| Cleanup & Size Selection | SPRI beads; Agarose gel extraction | Remove unwanted fragments and select optimal size ranges | Highly technique-dependent; common source of cross-operator variability [4] |

Addressing workforce and expertise gaps in NGS operations requires systematic approaches that combine standardized tools, structured training, and strategic workforce planning. The NGS Quality Initiative provides essential resources for standardizing procedures and documenting expertise, while the tiered framework exemplified by the GEIS program offers a model for distributing expertise across laboratory networks [1] [2] [3]. As NGS technologies continue evolving with platforms from Oxford Nanopore Technologies, Element Biosciences, and others offering improved accuracy and lower costs, the human expertise required to implement these technologies remains the critical factor in successful clinical implementation [1] [2]. Laboratories that proactively address workforce challenges through standardized quality management systems, competitive compensation structures, and strategic training investments will be best positioned to maintain robust NGS capabilities despite the broader industry challenges. The frameworks and troubleshooting guides presented here provide actionable starting points for institutions seeking to stabilize their NGS workforce while maintaining quality standards in clinical and public health applications.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What are the respective roles of CMS, FDA, and CDC in the CLIA program? Three federal agencies administer the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) program, each with a distinct role [5]:

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS): Issues laboratory certificates, conducts inspections, enforces regulatory compliance, and monitors laboratory performance of Proficiency Testing (PT).

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA): Categorizes tests based on complexity and reviews requests for CLIA Waiver by Application.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Provides analysis, research, technical assistance, and develops technical standards and laboratory practice guidelines.

Q: What are the key 2025 changes to CLIA personnel qualifications? Recent CLIA updates revised personnel qualification standards effective in 2025 [6] [7]. Key changes include:

- Degree Requirements: Permitted degrees now explicitly include chemical, biological, clinical, or medical laboratory science, or medical technology. "Physical science" has been removed as a qualifying degree.

- Equivalency Pathways: Updated pathways allow qualifying with specific credit hours (e.g., 120 semester hours with specific science coursework) as equivalent to a bachelor's degree for several positions.

- Grandfathering: Personnel who met qualifications before December 28, 2024, and remain in their roles continuously are generally permitted to continue under prior criteria.

- Laboratory Director CE: Directors qualifying as MD or DO now need at least 20 continuing education hours in laboratory practice.

Q: What are the major bioinformatic challenges when implementing NGS in a clinical setting? Implementing NGS in clinical settings poses unique bioinformatics challenges that impede the translation of genomic data into interpretable information [8] [9]:

- Sample Quality: Suboptimal samples (e.g., FFPE tissues with low DNA quality, low-abundance cell-free DNA in liquid biopsy) complicate variant detection and elevate false positives.

- Computational Complexity: The massive data output from NGS requires sophisticated algorithms and significant computing power for assembly and analysis [10].

- Variant Calling Precision: Detecting variants with low allele frequency (e.g., in CHIP or ctDNA) requires rigorous parameter settings, often forcing a trade-off between sensitivity and specificity [8].

- Data Interpretation: The volume and complexity of generated data make processing, storage, management, and clinical interpretation particularly challenging [9].

Q: What resources are available to help laboratories establish a quality management system for NGS? The CDC and APHL collaborated to form the Next-Generation Sequencing Quality Initiative (NGS QI), which develops publicly available tools to help laboratories implement NGS and build a robust Quality Management System (QMS) [2]. Their most widely used documents include the QMS Assessment Tool, SOP for Identifying and Monitoring NGS Key Performance Indicators, NGS Method Validation Plan, and NGS Method Validation SOP.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Failing Proficiency Testing (PT) for Hemoglobin A1C

Problem Laboratory results for Hemoglobin A1C proficiency testing fall outside the newly defined acceptable performance ranges.

Solution

- Verify Performance Criteria: Ensure you are using the correct 2025 performance threshold for your PT provider [7]:

- CMS: ±8% accuracy range

- College of American Pathologists (CAP): ±6% accuracy threshold

- Implement Corrective Actions: For results outside limits, immediately begin root cause analysis and document all corrective actions taken.

- Review Personnel Qualifications: Confirm testing personnel meet updated 2025 CLIA qualifications, as inadequate training can contribute to PT failures [6] [7].

Issue: NGS Assay Validation Failure

Problem NGS assay validation cannot meet stringent CLIA quality control criteria and performance standards.

Solution

- Utilize NGS QI Resources: Follow the "Pathway to Quality-Focused Testing" and use the NGS Method Validation Plan template from the NGS Quality Initiative to structure your validation [2].

- Lock Down Workflow: Once validated, ensure the entire NGS workflow—including library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatic pipeline—is locked down to maintain integrity [2].

- Monitor Key Performance Indicators (KPIs): Implement the NGS QI's "Identifying and Monitoring NGS Key Performance Indicators SOP" to track metrics like coverage uniformity, sensitivity, and specificity during validation [2].

Issue: Navigating Personnel Qualification Changes

Problem Laboratory personnel (new hires or existing staff) do not clearly meet updated 2025 CLIA qualification pathways.

Solution

- Consult Updated Definitions: Refer to the 2025 CLIA definitions for "doctoral degree," "laboratory training or experience," and "experience directing or supervising" [6].

- Explore Equivalency Pathways: For bachelor's degree requirements, investigate the new equivalency option of 120 semester hours with specific science coursework (48 semester hours in specific science/medical laboratory technology courses) [6].

- Apply Grandfathering Clause: For personnel employed before December 28, 2024, confirm they meet previous qualifications and maintain continuous employment to qualify for grandfathering [6].

Regulatory Relationships and NGS Validation Workflow

CLIA Regulatory Structure for NGS

NGS Assay Validation Process

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Clinical NGS Implementation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Clinical NGS | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| NGS Library Prep Kits | Fragments DNA/RNA and adds platform-specific adapters for sequencing. | Select kits designed for specific sample types (e.g., FFPE, liquid biopsy) to address input quality challenges [8]. |

| Targeted Enrichment Panels | Selectively captures genomic regions of clinical interest (e.g., cancer genes). | Panels must be clinically validated; performance affected by sample quality and intratumor heterogeneity [8]. |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | Software for sequence alignment, variant calling, and annotation. | Pipelines require extensive validation and locking; sensitivity/specificity trade-offs are critical for low-frequency variants [2] [8]. |

| Proficiency Testing (PT) Materials | External quality control samples to verify assay performance and personnel competency. | Must use approved PT providers for regulated analytes (e.g., Hemoglobin A1C) and meet 2025 performance criteria [7]. |

| Reference Standards | Samples with known variants used for assay validation and quality control. | Essential for establishing accuracy, precision, and limit of detection during NGS method validation [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our data storage costs are escalating rapidly with increasing NGS data. What are the most effective strategies for cost-effective, scalable storage?

A1: A combination of storage tiering and hybrid cloud solutions is the most effective strategy for managing scalable storage.

- Implement Tiered Storage: Utilize high-performance storage for active analysis and cheaper, cooler storage for archived data. Automated data lifecycle management policies can transition data between these tiers to optimize costs [11].

- Adopt a Hybrid Cloud Model: Hybrid cloud platforms provide elastic storage that can be scaled up or down with demand, reducing the overhead of maintaining large on-premise infrastructure [12]. For sensitive data, a federated analysis model can be employed, where analytical workflows are sent to the data's secure location instead of moving the data itself [11].

- Use Advanced Data Compression: Apply modern compression techniques to reduce file sizes without compromising data integrity, easing the burden on storage and network bandwidth [12].

Q2: We struggle with workflow reproducibility and portability between different computing environments. How can we standardize our bioinformatics analyses?

A2: Reproducibility is a cornerstone of scientific research and can be achieved through containerization and workflow management systems.

- Containerize Tools: Use containerization technologies like Docker or Singularity to package software, libraries, and dependencies into a single, portable unit. This eliminates the "it works on my machine" problem and ensures a consistent environment across different systems [11].

- Utilize Workflow Management Systems: Employ workflow languages like Nextflow to define complex, multi-step pipelines. These systems manage software versions, execute steps in a predefined order, and provide a complete audit trail for every analysis run [11]. Leveraging version-controlled, community-validated pipelines from repositories like nf-core can further enhance standardization [11].

- Choose a Bioinformatics Platform: Consider an integrated bioinformatics platform that provides a unified environment for data management, workflow orchestration, and analysis, often described as a "single pane of glass" for your research ecosystem [11].

Q3: What are the best practices for ensuring the security and privacy of sensitive clinical genomic data?

A3: Protecting patient data requires a multi-layered security approach.

- Implement Robust Access Controls: Enforce granular, role-based access controls (RBAC) to ensure researchers can only access the data necessary for their work. Comprehensive audit trails should log every data access and analysis action [11].

- Employ Advanced Encryption: Use end-to-end encryption to protect data both when it is stored (at rest) and when it is being transmitted (in transit) [13].

- Explore Federated Learning: For collaborative projects, federated learning allows you to train AI models across multiple institutions without centralizing or sharing the underlying raw data. The model is sent to the data, and only the aggregated results are returned [14].

Q4: The computational demands for AI-driven NGS analysis are straining our resources. How can we manage this surge in compute demand?

A4: The exponential growth in AI compute demand is a industry-wide challenge that requires strategic planning.

- Leverage Cloud and HPC Resources: Cloud platforms offer scalable, on-demand access to high-performance computing (HPC) resources, including GPUs essential for training AI models. National and institutional HPC centers are also expanding capacity to support AI and genomics research [15].

- Optimize AI Models and Infrastructure: Invest in efficient AI model architectures and utilize specialized hardware from providers like Nvidia, whose data-center GPU sales have surged due to AI demand [15]. The industry is responding with massive infrastructure investments, forecast to reach $2.8 trillion in AI-related spending by 2029 [15].

Common Computational Bottlenecks and Solutions

| Bottleneck | Symptoms | Proposed Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Storage Capacity & Cost | - Inability to store new datasets- Rapidly increasing infrastructure costs- Long data retrieval times | - Implement tiered storage (hot, cold, archive) [11]- Deploy data compression techniques [12]- Adopt a hybrid-cloud strategy for elastic scaling [12] |

| Long Workflow Runtimes & Lack of Reproducibility | - Analysis pipelines take days/weeks to complete- Inability to replicate results on a different system- "Software dependency hell" | - Use containerization (Docker/Singularity) for software environments [11]- Implement workflow managers (Nextflow) for portable, scalable execution [11]- Choose validated, version-controlled pipelines (e.g., nf-core) [11] |

| Data Security & Privacy Concerns | - Difficulty complying with regulations (HIPAA, GDPR)- Concerns over sharing data with collaborators- Risk of sensitive data exposure | - Enforce role-based access controls (RBAC) and audit trails [11]- Utilize end-to-end encryption for data at rest and in transit [13]- Apply federated learning models for privacy-preserving analysis [14] |

| High AI Compute Demand | - Inability to run complex AI/ML models- Long queue times for job scheduling- High cloud compute costs | - Leverage scalable cloud HPC and GPU resources [15]- Explore access to new supercomputers dedicated to life sciences (e.g., Isambard-AI, Doudna) [15] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol 1: Implementing a Reproducible NGS Analysis Pipeline

This methodology outlines the steps for setting up a containerized, reproducible RNA-Seq analysis pipeline using Nextflow.

1. Requirements and Setup:

- Software Dependencies: Install Nextflow, Docker (or Singularity), and a Git client.

- Compute Infrastructure: Access to a high-performance computing (HPC) cluster, cloud environment, or a powerful local server.

- Reference Data: Download the appropriate reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) and annotation file (GTF).

2. Pipeline Configuration:

- Select a pre-validated pipeline from the nf-core community (e.g.,

nf-core/rnaseq). - Create a nextflow.config file to define:

- Path to your input data (e.g., FASTQ files)

- Path to reference genome and annotation

- Execution profile (e.g.,

dockerfor containerization,slurmfor HPC execution) - All parameters must be explicitly declared and versioned [11].

3. Pipeline Execution and Provenance Tracking:

- Launch the pipeline with a command like:

nextflow run nf-core/rnaseq -profile docker,sge -c nextflow.config. - The workflow system automatically handles parallelization, software execution via containers, and failure recovery.

- Upon completion, the platform generates a detailed report including software versions, parameters, and an execution timeline, creating an immutable audit trail for full provenance [11].

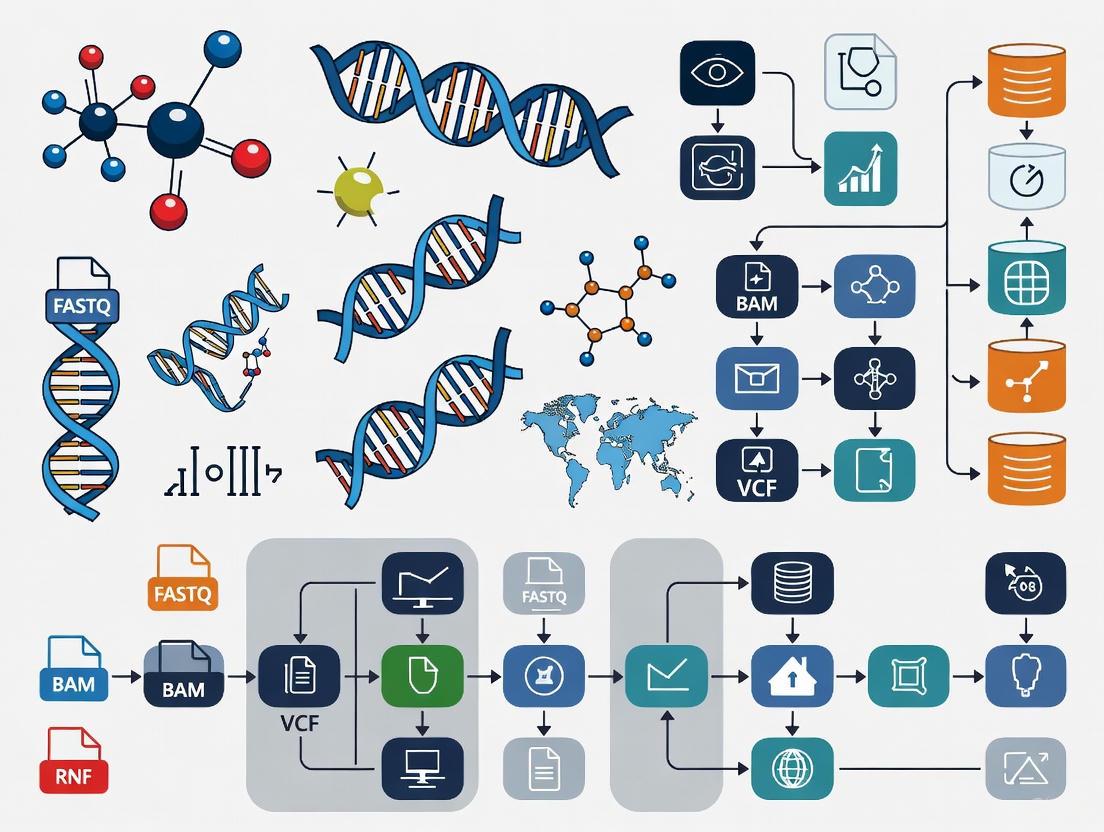

Workflow Visualization: From Wet Lab to Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the integrated, AI-enhanced workflow for NGS data generation and analysis, covering pre-wet-lab, wet-lab, and post-wet-lab phases [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

The following table details key resources for managing NGS data and computational infrastructure.

| Item | Category | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Docker / Singularity | Containerization Platform | Packages bioinformatics software, dependencies, and environment into a portable, reproducible unit, ensuring consistent operation across different systems [11]. |

| Nextflow | Workflow Management System | Defines and executes scalable, portable data analysis pipelines across diverse computing infrastructures (cloud, HPC), enabling reproducibility [11]. |

| nf-core | Pipeline Repository | A curated collection of community-built, peer-reviewed bioinformatics pipelines that follow best practices for reproducibility and standardization [11]. |

| Galaxy Filament | Data Access Framework | Unifies access to reference genomic data from multiple public repositories, allowing seamless combination with user data for analysis without massive downloads [17]. |

| Federated Learning Platform | Privacy-Preserving AI | Enables training AI models on data distributed across multiple secure locations (e.g., different hospitals) without moving or sharing the raw, sensitive data [14]. |

| Hybrid Cloud Storage | Data Storage Infrastructure | Provides elastic, scalable storage by combining on-premise resources with cloud storage, allowing labs to adjust capacity with demand and control costs [12]. |

| Role-Based Access Control (RBAC) | Security & Governance | Manages data security by granting users permissions based on their role, ensuring researchers only access the data necessary for their specific tasks [11]. |

| AI-Assisted Variant Caller (e.g., DeepVariant) | Analysis Tool | Uses a deep neural network to call genetic variants from sequencing data, achieving higher accuracy than traditional heuristic methods [16]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Sample Quality & FFPE Handling

Problem: Poor sequencing efficiency from FFPE samples

- Root Cause: Formalin fixation causes DNA damage including crosslinks, nucleotide oxidation, and fragmentation. Archival storage time exacerbates these effects [18].

- Detection: Implement PCR-based QC assays using incremental amplicon sizes (e.g., 105bp and 236bp). A QC ratio below 0.20 compared to control DNA indicates poor quality [18].

- Solution: Increase DNA input during library preparation for moderately degraded samples. For severely degraded samples (QC ratio <0.20), consider alternative specimens or targeted panels optimized for low-quality DNA [18].

Problem: Inconsistent variant calling in low GC-content regions

- Root Cause: Sample quality and GC content independently affect sequencing depth, with worst performance in low GC-content regions like KRAS in suboptimal samples [18].

- Detection: Monitor coverage uniformity across genomic regions with varying GC content.

- Solution: Increase sequencing depth for low GC-content regions when using suboptimal samples and utilize hybridization-capture techniques that perform better in these challenging regions [18].

Tumor Purity Assessment

Problem: Discrepant purity estimates between methods

- Root Cause: Different purity estimation methods (pathological, genomic, transcriptomic) measure different components of the tumor microenvironment and show poor concordance [19].

- Detection: Compare estimates from multiple methods (e.g., ESTIMATE, ABSOLUTE, LUMP, pathology) noting significant inter-method variation [20] [19].

- Solution: Parameterize genomic analyses with tumor purity estimated from the matched molecular analyte being analyzed. For DNA sequencing, use DNA-based purity estimates; for RNA sequencing, use RNA-based estimates [19].

Problem: Failed purity estimation in "quiet" genomes

- Root Cause: DNA-based purity estimation methods (ASCAT, CLONET, ABSOLUTE) may fail in tumors with low numbers of somatic single nucleotide variants, particularly in prostate cancer and other malignancies with quiet genomes [19].

- Detection: Monitor failure rates of DNA-based purity estimation methods; samples with failed estimates typically exhibit low SNV counts [19].

- Solution: Implement RNA-based purity estimation methods (DeMix, ISOpure-R) as alternatives for tumors with quiet genomes, or utilize multi-method consensus approaches [19].

Library Preparation

Problem: Biased library representation

- Root Cause: Nearly all library preparation steps introduce bias, especially in RNA-seq. Fragmentation methods, enzymatic manipulations, and PCR amplification can skew sequence representation [21].

- Detection: Analyze coverage uniformity and examine GC bias in sequencing results.

- Solution: Optimize fragmentation conditions, minimize PCR cycles, use high-fidelity polymerases, and consider PCR-free methods for appropriate sample types [22] [21].

Problem: Low library conversion efficiency

- Root Cause: Insfficient adapter ligation, residual contaminants, or suboptimal end repair and A-tailing reactions reduce the fraction of input fragments that become sequencing-competent molecules [22].

- Detection: Assess library concentration and size distribution using methods like qPCR, fluorometry, Bioanalyzer, or TapeStation [22].

- Solution: Optimize adapter concentration, use clean-up methods (magnetic beads, gel extraction) to remove adapter dimers, and ensure proper end repair and A-tailing reactions [22].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the minimal acceptable tumor purity for reliable NGS analysis? A: While TCGA initially used 80% tumor nuclei as a quality threshold, this was later reduced to 60%. However, purity requirements depend on your specific application and detection sensitivity needs. Samples with purity below 60% may still be analyzable but require specialized methods and careful interpretation [20].

Q: How does FFPE storage time impact sequencing success? A: FFPE storage time significantly correlates with sequencing efficiency metrics including depth of coverage, alignment rate, insert size, and read quality. Older samples generally show degraded performance, but successful sequencing can be achieved with samples over 20 years old when proper QC and protocol adjustments are implemented [18].

Q: What are the key differences between mechanical and enzymatic fragmentation? A: The table below compares these fragmentation methods:

| Factor | Mechanical Shearing | Enzymatic Fragmentation |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Bias | Minimal sequence bias, more random | Potential bias in GC or motif regions |

| Input Requirements | Higher input requirements | Accommodates lower input DNA |

| Equipment Needs | Requires specialized equipment (e.g., Covaris) | Lower equipment cost, reagent-based |

| Throughput | Lower throughput, scaling challenges | Automation-friendly, high-throughput |

| Insert Size Flexibility | Better for long inserts (>1kb) | Smaller dynamic range of insert sizes |

Q: How should we handle discrepancies between pathological and molecular tumor purity estimates? A: Discrepancies are common due to tumor heterogeneity and methodological differences. Pathological estimates represent a specific section while molecular estimates reflect the entire sample used for extraction. When discrepancies occur, trust the estimate from the analyte being sequenced (DNA-based for DNA sequencing, RNA-based for RNA sequencing) and consider the molecular estimate more representative for genomic analyses [19].

Q: What QC metrics are most critical for NGS library preparation? A: Essential QC metrics include:

- Concentration assessment (qPCR, fluorometry)

- Size distribution (Bioanalyzer, TapeStation)

- Adapter-dimer contamination levels

- Molar concentration verification

- Conversion efficiency calculation [22]

Impact of Pre-analytical Variables on Sequencing Efficiency

| Variable | Impact Level | Correlation with Sequencing Metrics | Recommended Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| FFPE Storage Time | Significant | Negative correlation with coverage depth, alignment rate, insert size, read quality | Use PCR QC ratio >0.20 regardless of age |

| PCR-based QC Ratio | Critical | Directly correlates with all sequencing efficiency parameters | Ratio >0.20 indicates favorable quality |

| DNA Input Amount | Significant | Affects library complexity and coverage uniformity | Follow manufacturer's recommendations based on QC ratio |

| Tumor Purity | Variable by cancer type | Affects variant calling sensitivity and expression profiling | Minimum 60% for most applications; lower may require specialized methods |

Tumor Purity Estimation Method Comparison

| Method | Principle | Average Purity Estimate | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathology Review | Visual estimation of tumor nuclei | 75.7% ± 21.2% | Direct assessment, clinically established | Subjective, intra- and inter-observer variability |

| ESTIMATE | Gene expression of 141 immune + 141 stromal genes | 81.1% ± 13.9% | RNA-based, accounts for microenvironment | Indirect measure, affected by expression patterns |

| ABSOLUTE | Somatic copy-number variation | 62.3% ± 19.9% | Direct measure of tumor cells | Requires copy number changes, fails in quiet genomes |

| LUMP | 44 non-methylated immune-specific CpG sites | 76.1% ± 16.1% | Methylation-based, reproducible | Measures immune infiltration specifically |

Experimental Protocols

PCR-Based DNA Quality Control Assay for FFPE Samples

Purpose: Determine DNA quality and recommend appropriate DNA input for library preparation [18].

Materials:

- 10ng DNA sample

- Two independent primer pairs generating 105bp and 236bp amplicons

- Control DNA from non-degraded source (e.g., A549 cell line)

- Agilent 2200 TapeStation or equivalent fragment analyzer

Procedure:

- Amplify 10ng of each DNA sample with both primer pairs

- Run PCR products on fragment analyzer for yield and fragmentation assessment

- Calculate QC ratio by dividing band quantification for each sample by respective band in positive control

- Average the ratios from both amplicons

- Interpret results: QC ratio >0.20 indicates favorable quality; <0.20 suggests moderate or poor quality

Application: Use this QC ratio to guide DNA input amount in subsequent library preparation steps [18].

Consensus Purity Estimation Methodology

Purpose: Generate robust tumor purity estimates by combining multiple estimation methods [20] [19].

Materials:

- Tumor sample with matched molecular data (DNA, RNA, methylation)

- Multiple purity estimation tools (ESTIMATE, ABSOLUTE, LUMP, etc.)

- IHC estimates if available

Procedure:

- Generate purity estimates using at least three different methods (e.g., DNA-based, RNA-based, and pathology)

- Normalize all estimates to have equal means and standard deviations

- Calculate Consensus Measurement of Purity Estimations (CPE) as the median of normalized values

- Use CPE for downstream analyses instead of individual method estimates

Note: This approach mitigates limitations of individual methods and provides more robust purity assessment [20].

Workflow Diagrams

Pre-analytical Factors Impact on NGS Data Quality

Tumor Purity Estimation Landscape

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Maxwell 16 FFPE Plus LEV DNA Purification Kit | Automated DNA extraction from FFPE samples | Standardized nucleic acid extraction from challenging FFPE samples [18] |

| Agilent Haloplex Target Enrichment System | Targeted gene capture using restriction enzymes | Custom panel design for specific gene sets; uses restriction digestion rather than sonication [18] |

| HostZERO Microbial DNA Kit | Reduces host DNA background in microbiome samples | Microbiome studies from host-associated samples where microbial DNA is a small fraction [23] |

| RiboFree rRNA Depletion Kit | Removes ribosomal RNA from RNA samples | Metatranscriptomics studies to enrich for messenger RNA and improve functional insights [23] |

| AMPure XP Beads | Magnetic bead-based purification and size selection | Library cleanup and size selection to remove adapter dimers and short fragments [22] |

| Quant-iT High-Sensitivity DNA Assay Kit | Accurate quantification of DNA concentration | Precise measurement of low-concentration DNA samples prior to library preparation [18] |

Building Robust Pipelines: Standardized Methods and Applications for Clinical NGS

This technical support center addresses the key challenges researchers and clinicians face when implementing robust, clinical-grade next-generation sequencing (NGS) workflows. The following guides and FAQs provide direct solutions to specific issues encountered during the bioinformatics pipeline.

What are the key stages in the NGS bioinformatics workflow?

The bioinformatics workflow for Illumina sequencing involves a multi-step process to transform raw data from the sequencer into annotated, clinically actionable variants. The journey begins with Binary Base Call (BCL) files, the raw data output containing base calls and quality scores from the sequencing run [24]. These are converted into FASTQ files, which store the sequence data and its corresponding quality scores in a text-based format, making it the standard starting point for most downstream analysis tools [24] [25]. The subsequent secondary analysis entails aligning these reads to a reference genome, resulting in BAM files (Binary Alignment Map), and then identifying variants to generate VCF files (Variant Call Format) [26] [27]. The final tertiary analysis involves annotating the VCF with biological and clinical information to aid in interpretation [28].

What are the most common policy barriers to clinical NGS implementation?

A multi-stakeholder Delphi study identified four critical policy challenges hindering the clinical adoption of NGS [29]:

- Payer variation in evidence standards: Different health plans use different criteria for assessing clinical utility, leading to inconsistent coverage policies.

- Proprietary databases: Companies maintaining private databases of variants slow down the collective understanding of variant clinical significance.

- Lack of standardized reporting: Inconsistent formats and content for reporting NGS test results to clinicians and patients.

- Uncertain regulatory role: Ongoing debate about the appropriate role of the FDA in overseeing NGS-based laboratory-developed tests (LDTs).

Troubleshooting Common Workflow Failures

FAQ 1: BCL to FASTQ Conversion Issues

Q: My BCL conversion is failing or producing empty FASTQ files. What should I check?

- A: This initial step is critical. Ensure the Illumina

bcl2fastqconversion software is correctly configured. Verify the run directory structure is intact and that you have provided the correct sample sheet. Confirm that the BCL files are not corrupted and that you have sufficient storage space, as BCL files are very large (>225 GB) and are often only stored for a short period (e.g., 3 months) [25].

FAQ 2: Poor Sequence Quality or Low Yield

Q: My FASTQ files have low-quality scores or low yield. What are the potential causes?

- A: Poor data quality often originates in the wet lab. Use a tool like FastQC to visualize quality metrics [27]. Common issues and their solutions are listed below.

Table: Troubleshooting Low-Quality FASTQ Data

| Problem Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low Q-scores, high error rate | Over-clustered flow cell, degraded reagents | Check cluster density metrics; use fresh PhiX control; ensure proper sequencer maintenance [27]. |

| High adapter contamination | Inefficient adapter ligation, inaccurate fragmentation | Optimize fragmentation parameters; titrate adapter-to-insert molar ratio; use trimming tools (Trimmomatic, Cutadapt) [4] [27]. |

| Low library complexity, high duplication | Insufficient input DNA, over-amplification | Re-quantify input DNA using fluorometry (Qubit); reduce PCR cycles during library prep [4]. |

| Abnormal GC bias | PCR artifacts, sequence-specific bias | Use PCR inhibitors; employ unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to correct for amplification duplicates [27]. |

FAQ 3: Low Mapping Rates in BAM Files

Q: A high percentage of my reads are failing to align to the reference genome. How can I fix this?

- A: Low mapping rates can stem from several issues. First, ensure you are using the correct version of the reference genome (e.g., GRCh38/hg38 for human) and that it is properly indexed for your aligner (e.g., BWA, Bowtie2) [30] [27]. Second, review the quality of your FASTQ files—high levels of adapter content or poor base quality will hinder alignment and should be addressed by more stringent read cleanup. Finally, consider the sample origin; high contamination levels or the presence of large, complex variants not well-represented in the reference can also cause low mapping rates.

FAQ 4: VCF Normalization and Annotation Errors

Q: Why do my variants not match known databases, and how can I ensure accurate annotation?

- A: A primary reason for this discrepancy is that a single line in a VCF file can describe multiple alternative alleles at a single locus, a process that can "hijack" simple variants and make them difficult to match against standardized databases [31]. To ensure accurate annotation, you must pre-process your VCF file by splitting multi-allelic sites and left-normalizing indels [31].

The recommended command-line solution using bcftools is:

bcftools norm -m-both -o output.step1.vcf input.vcf.gz(Splits multi-allelic sites)bcftools norm -f reference_genome.fasta -o output.step2.vcf output.step1.vcf(Left-normalizes variants) [31].

After this pre-processing, annotation with tools like ANNOVAR or Ensembl VEP will be more reliable, as they can correctly match your variants to left-normalized database records [31] [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table: Key Tools and Resources for the BCL to VCF Pipeline

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| bcl2fastq / bcl-convert | Converts raw BCL files from the sequencer into demultiplexed FASTQ files. | Illumina-provided software; essential first step for most data analysis pipelines [24] [26]. |

| FastQC | Provides quality control metrics for raw FASTQ data. | Visualizes per-base quality, adapter contamination, GC content, etc.; used for QC check pre-alignment [27]. |

| Trimmomatic / Cutadapt | Trims adapter sequences and low-quality bases from reads. | Critical for "cleaning" FASTQ files before alignment to improve mapping rates [27]. |

| BWA / Bowtie2 | Aligns (maps) sequencing reads to a reference genome. | Industry-standard aligners; output is in SAM/BAM format [24] [27]. |

| SAMtools / Picard | Manipulates and processes alignment files (BAM/SAM). | Used for sorting, indexing, marking duplicates, and extracting metrics [27]. |

| GATK / VarScan | Calls sequence variants (SNPs, indels) from aligned reads. | Identifies differences between the sample and the reference genome; generates a raw VCF [28]. |

| bcftools | Manipulates and normalizes VCF files. | Used for filtering, splitting, normalizing, and validating VCFs [31]. |

| VEP / ANNOVAR | Annotates variants with functional, population, and clinical data. | Adds context to variants (e.g., gene effect, frequency in 1000 Genomes, ClinSig) for interpretation [31] [28]. |

| GRCh38 Reference Genome | The standard reference sequence for human alignment and variant calling. | Always use the correct, consistently labeled version; available from GENCODE or GATK resource bundle [27]. |

Implementing a Quality Management System

For clinical implementation, simply having a workflow is insufficient. Laboratories must establish a robust Quality Management System (QMS). The Next-Generation Sequencing Quality Initiative (NGS QI) provides tools to help laboratories navigate CLIA requirements and other complex regulatory environments [2]. Key recommendations include:

- Workflow Lockdown: Once validated, the entire bioinformatic workflow (including software versions and parameters) must be locked down to ensure reproducibility [2].

- Personnel Competency: Ensure staff receive ongoing training and competency assessments, as specialized bioinformatics knowledge is critical and staff turnover can be a significant barrier [2].

- Standardized Validation: Use available validation tools and templates (e.g., the NGS QI's Method Validation Plan) to ensure compliance with quality and regulatory standards [2].

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is it recommended to use different specialized callers for different variant types, and what are the top choices? Using a single, universal variant caller is not optimal because the distinct biological signatures and genomic patterns of different variant types require specialized algorithmic approaches. A "jack of all trades" caller is often a "master of none," making the consolidation of calls from multiple best-in-class tools the preferred strategy for comprehensive variant detection [32]. The table below summarizes recommended tools for key variant types.

Table: Recommended Variant Calling Tools by Variant Type

| Variant Type | Recommended Tools | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Germline SNVs/Indels | GATK HaplotypeCaller [33] [34], Platypus [33] [34], FreeBayes [34], BCFtools [34] | Combining two orthogonal callers (e.g., HaplotypeCaller and Platypus) can offer a slight sensitivity advantage [33]. |

| Somatic SNVs/Indels | MuTect2 [34], Strelka2 [34], VarScan2 [34], VarDict [34] | Tumor heterogeneity and subclonal populations require callers specifically designed for somatic variants [32]. |

| Structural Variants (SVs) | Manta [34], DELLY [34], Lumpy [34] | SV callers rely on patterns like discordant read pairs, split reads, and read depth changes [32]. |

| Copy Number Variants (CNVs) | ExomeDepth [34], XHMM [34] | CNV detection from exome and panel data is possible, but whole-genome sequencing is superior [33]. |

Q2: What are the essential data pre-processing steps required before variant calling to ensure accuracy? A robust pre-processing workflow is critical to avoid the "garbage in, garbage out" problem. The primary goal is to generate an analysis-ready BAM file [32]. Key steps include:

- Read Alignment: Map raw sequencing reads (FASTQ) to a reference genome using an aligner like BWA-MEM [33] [34]. Initially, prioritize sensitivity over specificity to avoid overlooking true variants [32].

- Duplicate Marking: Identify and mark PCR duplicate reads using tools like Picard or Sambamba to prevent over-counting of the same original DNA fragment [33] [34].

- Base Quality Score Recalibration (BQSR): This step, part of the GATK Best Practices, uses an empirical error model to adjust base quality scores. Note that evaluations show marginal improvements, and it is computationally expensive, making it somewhat optional [33] [34].

- Quality Control (QC): Perform routine QC on the BAM file to evaluate sequencing metrics, verify sufficient coverage, and check for sample contamination using tools like BEDTools, Picard, and VerifyBamID [33] [34].

The following diagram illustrates the standard pre-processing workflow.

Q3: How does the choice of sequencing strategy (Panel, Exome, Genome) impact my ability to detect different variants? The choice of sequencing strategy involves a trade-off between the breadth of the genome interrogated, the average depth of sequencing achieved, and cost. Each strategy has distinct strengths and weaknesses for detecting various variant types [33] [32].

Table: Impact of Sequencing Strategy on Variant Detection

| Sequencing Strategy | Target Space | Average Depth | SNV/Indel | CNV | SV | Low VAF/Variant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Panel | ~0.5 - 5 Mbp | 500 - 1000x | Outstanding (++) | Good (+) | Poor (-) | Excellent for low VAF |

| Whole Exome (WES) | ~50 Mbp | 100 - 150x | Outstanding (++) | Good (+) | Poor (-) | Good |

| Whole Genome (WGS) | ~3200 Mbp | 30 - 60x | Outstanding (++) | Outstanding (++) | Good (+) | Good |

Q4: What publicly available benchmark resources should I use to validate my variant calling pipeline's performance? To objectively evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of a variant calling pipeline, it is essential to use benchmark datasets where the "ground truth" variants are known [33]. The following are key resources:

- Genome in a Bottle (GIAB): Provides high-confidence consensus variant calls for several human samples, along with defined high-confidence genomic regions. It is one of the most widely used benchmarks for germline small variants [33] [34].

- Platinum Genomes: Another benchmark set for the NA12878 sample, offering a high-quality set of truth variants [33] [34].

- Synthetic Diploid (Syndip): A benchmark derived from long-read assemblies of two homozygous cell lines. It is less biased than consensus-based resources and is particularly valuable for assessing accuracy in challenging genomic regions, such as segmental duplications [33].

Q5: My pipeline crashed during SV benchmarking. What are the common pre-processing steps required for structural variant VCFs? SV benchmarking often fails due to inconsistent VCF formatting across different callers. A standardization and normalization workflow is required to homogenize the test and truth VCF files for an accurate comparison [35]. Key steps include:

- Reformatting: Use tools like

svyncto reformat VCFs from different SV callers into a consistent structure [35]. - Standardization & Decomposition: Tools like

SVTK standardizeandrtgtools svdecomposeare used to standardize SV types to breakends (BND) and decompose complex SVs [35]. - Normalization: Use

bcftools normto split multi-allelic variants, deduplicate variants, and left-align indels. This ensures all variants are represented in a canonical form [35].

The logic for troubleshooting a failed SV benchmarking run is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This table lists essential reagents, software, and reference materials critical for setting up a standardized variant detection workflow.

Table: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Core Variant Calling

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| SureSeq FFPE DNA Repair Mix | Enzyme mix designed to repair a broad range of DNA damage in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples, helping to reduce formalin-induced artifacts and increase confidence in variant calls from degraded samples [32]. |

| SureSeq CLL + CNV Panel | An example of a targeted gene panel that provides comprehensive coverage of key genes and regions for a specific disease (Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia), enabling simultaneous detection of SNVs, Indels, and exon-level CNVs in a single workflow [32]. |

| OGT Interpret NGS Analysis Software | Automated data analysis software that provides predefined settings for calling SNVs, indels, and structural aberrations (like ITDs, CNVs), minimizing user intervention and maximizing consistency [32]. |

| Illumina BaseSpace Sequence Hub / DNAnexus | Cloud-based platforms that provide user-friendly, AI-powered bioinformatics analysis without requiring advanced programming skills, facilitating variant calling and interpretation [16]. |

| Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) Reference Materials | Publicly available reference DNA samples and associated "ground truth" variant datasets used to benchmark, validate, and optimize the performance of variant calling pipelines for clinical implementation [33]. |

Implementing Quality System Essentials (QSE) for Clinical Bioinformatics

Clinical bioinformatics represents a critical bridge between raw next-generation sequencing (NGS) data and clinically actionable information. Within diagnostic laboratories, implementing robust Quality System Essentials (QSE) ensures the accuracy, reliability, and reproducibility of genomic data analysis. The Next-Generation Sequencing Quality Initiative (NGS QI), established by the CDC and Association of Public Health Laboratories (APHL), provides a structured framework based on twelve Quality System Essentials adapted from the Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [2] [36]. This framework addresses the entire testing lifecycle, from personnel qualifications and equipment management to process control and data management, creating a foundation for clinical-grade bioinformatics operations.

As NGS technologies evolve with new platforms, improved chemistries, and advanced bioinformatic analyses, the complexity of validation and quality management increases significantly [2]. Clinical bioinformatics now demands production-scale operations that differ substantially from research-oriented core facilities, requiring standardized practices, rigorous validation, and comprehensive documentation [37]. The dynamic nature of this field presents ongoing challenges for quality management, particularly with the introduction of targeted sequencing approaches, metagenomic applications, and increasingly sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines [2] [38].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common NGS Bioinformatics Challenges: Q&A

Q: Our clinical NGS assay failed to detect variants present in reference materials at expected allele frequencies. What are the primary causes?

A: Variant detection failures typically stem from several technical issues:

- Assay incompatibility: Verify that your assay's target regions actually include the variant positions. Review manufacturer Target Region GTF files and variant coordinates carefully, as not all assays cover all variants in a gene [39].

- Insufficient sequencing depth: Low coverage dramatically reduces variant detection sensitivity. Modeled data shows that 500 reads for a 10% variant yields a 95% confidence interval of approximately 7.2-13.0%, while 2000 reads narrows this to 8.7-11.4% [39].

- Low library complexity: Inadequate input DNA or over-amplification can reduce library complexity. For ctDNA applications with typical 165bp fragments, 120-160bp amplicons will capture only 3-27% of input molecules, potentially dropping effective input below 15ng [39].

- Amplicon size limitations: Larger amplicons in fragmented DNA (e.g., ctDNA) show reduced efficiency. Variants requiring larger amplicons may be undetectable while those with smaller amplicons are reliably detected [39].

Table 1: Troubleshooting Variant Detection Issues

| Problem | Root Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Variants in reference materials not detected | Assay target region doesn't cover variant | Verify variant coordinates in assay design files |

| Low variant allele frequency precision | Insufficient sequencing depth | Increase coverage to manufacturer recommendations |

| Inconsistent variant detection across samples | Low library complexity from inadequate input | Optimize input DNA quantity; avoid over-amplification |

| Specific variants consistently missed | Amplicon size inefficiencies for fragmented DNA | Redesign assays with smaller amplicons for fragmented DNA |

Q: Our bioinformatics pipeline produces inconsistent variant calls across sequencing runs. How can we improve reproducibility?

A: Inconsistent variant calling typically indicates issues with pipeline stability, documentation, or validation:

- Implement containerization: Use Docker or Singularity containers to encapsulate software environments, ensuring consistent tool versions and dependencies across executions [37].

- Establish version control: Maintain all code, documentation, and configurations in a git-tracked system with strict change control procedures [37].

- Standardize analysis parameters: Adopt hg38 as reference genome and define a standard analysis set including SNV, CNV, SV, STR, and LOH analyses [37].

- Enhance validation practices: Supplement standard truth sets (GIAB for germline, SEQC2 for somatic) with recall testing of previously validated clinical samples [37].

Q: We're experiencing high personnel turnover in our clinical bioinformatics unit. How can we maintain quality despite staffing changes?

A: Workforce stability challenges are common in clinical genomics, with surveys indicating some personnel holding positions for <4 years on average, and 30% of public health laboratory staff planning to leave within 5 years [2]. Address this through:

- Comprehensive documentation: Develop detailed SOPs covering all analytical processes. The NGS QI offers over 100 free guidance documents and templates for customization [2] [36].

- Structured competency assessment: Implement regular competency evaluations using tools like the Bioinformatician Competency Assessment SOP from NGS QI [2].

- Cross-training programs: Ensure multiple team members understand each component of the bioinformatics workflow to maintain operations during transitions.

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Experiments

Protocol: Bioinformatics Pipeline Validation for Clinical WGS

Purpose: Establish analytical validity of clinical whole genome sequencing bioinformatics pipelines according to regulatory standards [37].

Materials:

- Reference materials: Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) for germline variants, SEQC2 for somatic variants

- Previously characterized clinical samples with orthogonal validation

- High-performance computing infrastructure

- Containerization software (Docker/Singularity)

Procedure:

- Unit Testing: Validate individual pipeline components (alignment, variant calling, annotation) using synthetic datasets with known variants.

- Integration Testing: Assess component interactions using intermediate file formats (BAM, VCF) from reference materials.

- System Testing: Execute end-to-end analysis on GIAB reference materials with predefined acceptance criteria for sensitivity (>99%), specificity (>99.5%), and reproducibility (100% concordance).

- Performance Validation: Test pipeline on 25-30 previously characterized clinical samples representing intended use cases.

- Sample Identity Verification: Implement genetic fingerprinting checks including sex chromosome concordance and relatedness estimation between serial samples [37].

Validation Criteria:

- Sensitivity: >99% for SNVs/indels in covered regions

- Specificity: >99.5% for all variant types

- Reproducibility: 100% concordance between replicate analyses

- Sample identity: Zero mismatches in genetic fingerprinting

Table 2: Required Bioinformatics Team Competencies

| Skill Domain | Essential Competencies | Quality Documentation |

|---|---|---|

| Software Development | Version control, testing, containerization | Git repositories, test logs, container manifests |

| Data Management | Secure transfer, integrity verification, backup | Checksum logs, access controls, backup logs |

| Quality Assurance | Validation protocols, change control, audit trails | Validation reports, SOPs, audit reports |

| Domain Knowledge | Human genetics, variant interpretation, regulatory standards | Training records, competency assessments, CME documentation |

Workflow Visualization

Clinical Bioinformatics QSE Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Resources for Clinical Bioinformatics

| Resource Category | Specific Products/Tools | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Materials | Genome in a Bottle (GIAB), SEQC2, Seraseq Reference Materials | Benchmark variant calling accuracy; validate assay performance across variant types [37] [39] |

| Bioinformatics Containers | Docker, Singularity, Bioconda | Reproducible software environments; version-controlled dependencies [37] |

| Quality Control Tools | FastQC, MultiQC, Qualimap | Monitor sequencing quality metrics; identify pre-analytical errors [4] [38] |

| Variant Calling Tools | Multiple complementary tools for SNV, CNV, SV detection | Comprehensive variant detection; reduce false positives/negatives through tool combination [37] |

| Validation Resources | NGS QI Validation Plan Template, Method Validation SOP | Standardized validation protocols; regulatory compliance documentation [2] [36] |

Implementing robust Quality System Essentials in clinical bioinformatics requires both technical solutions and organizational commitment. As the field continues to evolve with platforms offering increasing accuracy and new applications like metagenomic pathogen detection, the QSE framework provides the necessary foundation for maintaining quality amidst rapid change [2]. The NGS Quality Initiative offers laboratories a valuable starting point with customizable tools that can be adapted to specific laboratory needs while maintaining compliance with regulatory requirements [36]. Success ultimately depends on integrating quality management into each step of the bioinformatics workflow, from sample to clinical report, while maintaining the flexibility to incorporate technological advancements that benefit patient care.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why am I getting different TMB values from different targeted sequencing panels?

Different panels can yield different TMB values due to variations in panel size, genomic content, and bioinformatic pipelines. The confidence of TMB estimation is highly dependent on the size of the targeted sequencing panel [40]. Smaller panels are more susceptible to statistical noise and may lack the robustness of larger panels or whole-exome sequencing (WES). To troubleshoot:

- Verify Panel Size: Use panels covering at least 1.0-1.5 Mb whenever possible. Smaller panels may require specific correction factors [40].

- Check for Synonymous Mutations: Determine if the panel's bioinformatic pipeline includes synonymous mutations in its TMB calculation. Some panels include them to reduce sampling noise, while others, like MSK-IMPACT, do not [40].

- Validate with a Reference Standard: If possible, validate your panel's TMB output against a WES-derived TMB value for a set of samples to understand the concordance.

FAQ 2: How can I accurately determine MSI status from degraded FFPE samples using NGS?

FFPE-derived DNA is often fragmented and damaged, which can lead to sequencing artifacts and false-positive MSI calls.

- Use Degradation-Robust Library Prep Kits: Employ library preparation kits specifically designed for FFPE and cell-free DNA (cfDNA), which are optimized for low-input and degraded material [41].

- Incorporate Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Use kits that leverage UMIs to correct for errors introduced during amplification and sequencing, improving the accuracy of mutation calling in difficult samples [41].

- Leverage Specialized Bioinformatics: Utilize analysis software with modules specifically designed for MSI quantification from FFPE samples. These tools often include algorithms to account for sample-specific noise [41].

FAQ 3: What are the major challenges when transitioning TMB and MSI analysis to a liquid biopsy platform?

Liquid biopsy, while less invasive, presents unique challenges compared to tissue-based analysis.

- Low Abundance of ctDNA: In early-stage cancers or certain cancer types, the fraction of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in the total cell-free DNA (cfDNA) can be very low, affecting detection sensitivity [42] [41].

- Tumor Heterogeneity: A liquid biopsy may not fully capture the spatial heterogeneity of the entire tumor, as ctDNA is shed from multiple tumor sites [41].

- Lack of Standardization: It is not yet fully established how TMB and MSI results from liquid biopsies compare to the gold standard of tissue biopsy, and validation against a tissue standard is currently recommended [41].

FAQ 4: My bioinformatic pipeline for MSI detection has a high false-positive rate. How can I improve its specificity?

A high false-positive rate is often due to sequencing artifacts or misclassification of polymerase slippage in homopolymer regions.

- Implement a Matched Normal: Always sequence a matched normal sample (e.g., from blood or saliva) alongside the tumor sample. This allows for the subtraction of germline polymorphisms and the identification of individual-specific sequencing artifacts [43].

- Optimize Bioinformatics Filters: Apply filters for sequencing quality, read depth, and mapping quality. For MSI, specifically, ensure the algorithm is tuned to distinguish true somatic instability from technical noise.

- Choose an Appropriate Method: Some NGS-based methods, like Archer's VARIANTPlex panels, are designed to accurately quantify MSI status without a matched normal by using a robust baseline of normal samples, which can be a viable alternative [41].

Quantitative Data Tables

Table 1: Comparison of Commercial NGS Panels for TMB and MSI Analysis

This table summarizes key features of various targeted sequencing panels used for TMB and MSI assessment in clinical research, highlighting the diversity in approach [40].

| Laboratory | Panel Name | Number of Genes | Total Region Covered (Mb) | TMB Region Covered* (Mb) | Mutation Types in TMB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foundation Medicine | FoundationOne CDx | 324 | 2.20 | 0.80 | Non-synonymous, Synonymous |

| Memorial Sloan Kettering | MSK-IMPACT | 468 | 1.53 | 1.14 | Non-synonymous |

| Illumina | TSO500 (TruSight Oncology 500) | 523 | 1.97 | 1.33 | Non-synonymous, Synonymous |

| Thermo Fisher Scientific | Oncomine Tumor Mutation Load Assay | 409 | 1.70 | 1.20 | Non-synonymous |

| Tempus | TEMPUS Xt | 595 | 2.40 | 2.40 | Non-synonymous |

| Guardant Health | GuardantOMNI | 500 | 2.15 | 1.00 | Non-synonymous, Synonymous |

*Coding region used to estimate TMB.

Table 2: Key Biomarker Definitions and Clinical Significance

This table provides a clear overview of the biomarkers discussed, their biological basis, and their role in immunotherapy [43] [41].

| Biomarker | Full Name | Biological Mechanism | Role as Predictive Biomarker |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMRd | Mismatch Repair Deficiency | Inability of the cell to correct errors (mismatches) made during DNA replication. | Predicts response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). Tumors with MMRd are often MSI-H and TMB-H. |

| MSI-H | Microsatellite Instability-High | A consequence of MMRd; accumulation of mutations in short, repetitive DNA sequences (microsatellites). | An established biomarker for ICI efficacy across multiple cancer types. |

| TMB-H | High Tumor Mutational Burden | A high number of mutations (typically ≥10 mut/Mb) per megabase of DNA sequenced. | Used to identify patients likely to respond to ICIs, as high mutation load can lead to more neoantigens. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining MSI Status Using a Targeted NGS Panel

Methodology: This protocol uses DNA extracted from tumor tissue (ideally FFPE with a matched normal) and a targeted NGS panel covering multiple microsatellite regions.

- Library Preparation: Use a library prep kit validated for your sample type (e.g., FFPE). Kits like the xGen cfDNA & FFPE DNA Library Prep Kit are designed for degraded samples. Incorporate UMIs to improve variant calling accuracy [41].

- Target Enrichment: Enrich for the target regions (including microsatellites) using either:

- Hybridization Capture: Uses biotinylated probes to pull down regions of interest. Common for comprehensive panels.

- Amplicon-Based (e.g., AMP): Uses gene-specific primers for PCR-based enrichment. Can be effective for smaller, focused panels [41].

- Sequencing: Perform high-throughput sequencing on an NGS platform to achieve sufficient depth (e.g., >500x coverage) for accurate mutation detection.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Alignment: Map sequencing reads to a reference genome.

- Variant Calling: Identify insertions and deletions (indels) within the targeted microsatellite loci.

- MSI Scoring: Compare the number and length of indels in the tumor sample to a baseline (from the matched normal or a built-in baseline of normal samples). A sample is classified as MSI-H if the instability score exceeds a predefined threshold [41].

Protocol 2: Calculating TMB from Targeted Sequencing Data

Methodology: This protocol outlines the steps to calculate TMB from the same targeted NGS data used for other somatic variant detection.

- Somatic Variant Calling: Identify somatic mutations in the tumor sample using a matched normal to filter out germline variants. Call single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small indels.

- Mutation Filtering:

- Remove known germline polymorphisms from population databases (e.g., gnomAD).

- Filter out technical artifacts and variants in low-complexity or blacklisted genomic regions.

- TMB Calculation:

- Count the total number of somatic, coding (often non-synonymous) mutations that pass all filters.

- Divide the total number of mutations by the size of the coding region (in megabases) targeted by the panel that was effectively sequenced. For example: TMB = (Total Passed Mutations) / (Panel Size in Mb).

- Report the result as mutations per megabase (mut/Mb) [40].

- Interpretation: Classify the tumor as TMB-H based on a validated cutoff. The FDA has approved a cutoff of ≥10 mut/Mb for pembrolizumab in certain solid tumors, but optimal cutoffs can vary by cancer type [40].

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Diagram 1: Integrated NGS Workflow for TMB and MSI Analysis. This chart outlines the key steps from sample collection to final biomarker report, highlighting parallel bioinformatics pathways.

Diagram 2: Biological Relationship Between MMRd, MSI-H, and TMB-H. This chart shows how different molecular defects converge on a common mechanism of increased immunogenicity and response to immunotherapy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Kits

This table lists key products and technologies used in experiments for TMB, MSI, and liquid biopsy analysis.

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| xGen cfDNA & FFPE DNA Library Prep Kit | Library preparation for NGS from challenging samples like cfDNA and degraded FFPE DNA. | Optimized for low-input, fragmented DNA; includes UMI adapters for error correction [41]. |

| Archer VARIANTPlex Panels | Targeted NGS panels (e.g., Solid Tumor) for variant, MSI, and TMB analysis. | Uses Anchored Multiplex PCR (AMP) chemistry; works with degraded samples; includes analysis suite [41]. |

| FoundationOne CDx | Comprehensive genomic profiling panel for solid tumors. | FDA-approved IVD test; reports TMB, MSI, and other genomic alterations from FFPE tissue [40]. |

| MSK-IMPACT | Targeted panel sequencing for tumor profiling. | FDA-authorized test; assesses TMB and mutations in 468 genes [43] [40]. |

| CellSearch System | Enumeration and isolation of Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) from blood. | FDA-cleared system for prognostic use in metastatic breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer [42]. |

Optimizing for Production: Troubleshooting and Scaling Clinical Bioinformatics Workflows

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Common Bioinformatics Pipeline Failures

Problem: Pipeline execution fails or produces unexpected results.

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Pipeline fails immediately | Incorrect software version or missing dependency [44] | Use containerized environments (e.g., Docker, Singularity) to ensure consistency [45]. |

| Low-quality variant calls | Poor initial data quality or misaligned reads [46] | Check FastQC reports; re-trim reads; verify alignment metrics with SAMtools [44] [46]. |

| Pipeline runs very slowly | Computational bottlenecks; inefficient resource allocation [44] [47] | Use a workflow manager (e.g., Nextflow) for dynamic resource allocation; leverage cloud scaling [47]. |

| Results are irreproducible | Unrecorded parameters or manual intervention in workflow [46] | Implement version control (Git) for all scripts and use workflow managers for full automation [44] [46]. |

| High cloud computing costs | Misconfigured execution environment; over-provisioning resources [47] | Audit cloud configuration; right-size computing instances; use spot pricing where possible [47]. |

Guide 2: Addressing Data Quality and Preprocessing Issues

Problem: The input data is of low quality, leading to unreliable downstream analysis.

| Symptom | Diagnostic Tool | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low Phred scores, adapter contamination | FastQC, MultiQC [44] [46] | Use Trimmomatic or Picard to trim adapters and remove low-quality bases [44] [46]. |

| Low alignment rate | Alignment tool (BWA, STAR) logs, SAMtools [44] | Verify reference genome compatibility; check for sample contamination [44] [46]. |

| Unexpected coverage depth | Qualimap, SAMtools coverage stats [46] | Re-sequence with adjusted depth; use hybrid capture methods for targeted regions [48]. |

| Batch effects in sample group | Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [46] | Include batch as a covariate in statistical models; use normalization methods like ComBat [46]. |

| Sample mislabeling or swap | Genetic fingerprinting, sex-check markers [45] | Implement barcode labeling and use LIMS for sample tracking; verify identity with genetic markers [45] [46]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary goal of bioinformatics workflow optimization? The primary goal is to enhance reproducibility, efficiency, and agility in data analysis. This is crucial for managing growing dataset sizes and complexity, ensuring reliable results in clinical and research settings, and controlling computational costs [47].

Q2: When should we start optimizing our bioinformatics workflows? Optimization should begin when usage scales justify the investment. Key triggers include rising computational costs, frequent pipeline failures, difficulties in reproducing results, or the need to process significantly larger datasets. Starting early builds a strong foundation for scalability [47].

Q3: What are the most common tools for managing bioinformatics workflows? Workflow management systems like Nextflow and Snakemake are industry standards. They help automate processes, manage software dependencies, and ensure portability across different computing environments (local servers, HPC clusters, or cloud platforms) [44] [47].

Q4: How can we ensure our clinical bioinformatics pipeline is robust? Follow consensus recommendations for clinical production, which include:

- Using the latest human reference genome (GRCh38/hg38) [45].

- Implementing a standard set of analyses (SNV, INDEL, CNV, and SV calling) [45].

- Validating pipelines with standard truth sets (e.g., GIAB) and in-house data [45].

- Ensuring sample identity through genetic fingerprinting [45].

Q5: Our pipeline works but is too slow. How can we improve its speed? Address computational bottlenecks by: