Multimodal Data Fusion in Oncology: Transforming Cancer Diagnosis Through AI Integration

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of multimodal data fusion and its transformative impact on cancer diagnosis and personalized oncology.

Multimodal Data Fusion in Oncology: Transforming Cancer Diagnosis Through AI Integration

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of multimodal data fusion and its transformative impact on cancer diagnosis and personalized oncology. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it systematically covers the foundational principles, diverse methodological approaches, and practical applications of integrating heterogeneous data types such as genomics, digital pathology, radiomics, and clinical records. The content further addresses critical challenges in implementation, including data heterogeneity and model interpretability, and offers a rigorous comparative analysis of fusion techniques and their validation. By synthesizing evidence from recent advancements and clinical case studies, this review serves as a strategic resource for developing robust, clinically applicable AI tools that enhance diagnostic accuracy, improve patient stratification, and accelerate precision medicine.

The Foundation of Multimodal Oncology: Unraveling Data Types and Clinical Imperatives

Defining Multimodal Data Fusion in the Cancer Diagnostic Ecosystem

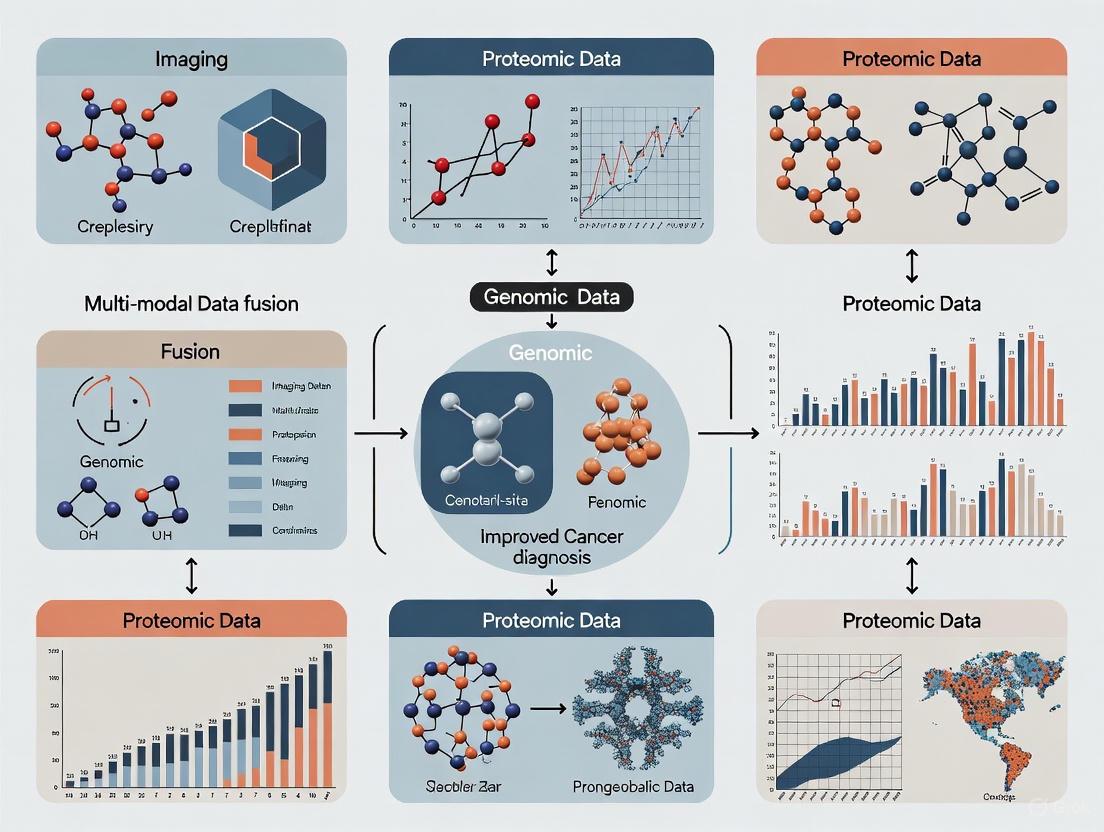

Multimodal data fusion represents a paradigm shift in oncology diagnostics, moving beyond the limitations of single-data-type analysis. It is defined as the process of integrating information from multiple, heterogeneous data types—such as genomic, histopathological, radiological, and clinical data—to create a richer, more comprehensive representation of a patient's disease status [1] [2]. The core principle is that orthogonal data modalities provide complementary information; by combining them, the resulting model can capture a more holistic view of the complex biological processes in cancer, leading to improved inference accuracy and clinical decision-making [1] [3]. This integrated approach is foundational for advancing precision oncology, as it enables a multi-scale understanding of cancer, from molecular alterations and cellular morphology to tissue organization and clinical phenotype [3].

The clinical imperative for this integration is stark. Cancer manifests across multiple biological scales, and predictive models relying on a single data modality fail to capture this multiscale heterogeneity, limiting their generalizability and clinical utility [3]. In contrast, multimodal artificial intelligence (MMAI) models that contextualize molecular features within anatomical and clinical frameworks yield a more comprehensive and mechanistically plausible representation of the disease [3]. By converting multimodal complexity into clinically actionable insights, this approach is poised to improve patient outcomes across the entire cancer care continuum, from prevention and early diagnosis to prognosis, treatment selection, and outcome assessment [3] [4].

Current Applications and Quantitative Outcomes

Multimodal fusion techniques have been successfully applied to various diagnostic challenges in oncology, demonstrating superior performance compared to unimodal approaches. The following table summarizes key applications and their documented performance metrics from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Multimodal Data Fusion Applications in Cancer Diagnosis

| Cancer Type | Data Modalities Fused | AI Architecture / Model | Key Performance Metrics | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer [5] | B-mode Ultrasound, Color Doppler, Elastography | HXM-Net (Hybrid CNN-Transformer) | Accuracy: 94.20%Sensitivity: 92.80%Specificity: 95.70%F1-Score: 91.00%AUC-ROC: 0.97 | Tumor classification (Benign vs. Malignant) |

| Lung Cancer [6] | CT Images, Clinical Data (24 features) | CNN (for images) + ANN (for clinical data) | Image Classification Accuracy: 92%Severity Prediction Accuracy: 99% | Histological subtype classification & cancer severity prediction |

| Melanoma [3] | Not Specified (Multimodal integration) | MUSK (Transformer-based) | AUC-ROC: 0.833 (5-year relapse prediction) | Relapse and immunotherapy response prediction |

| Glioma & Renal Cell Carcinoma [3] | Histology, Genomics | Pathomic Fusion | Outperformed WHO 2021 classification | Risk stratification |

The success of these models hinges on their ability to leverage complementary information. For instance, in breast ultrasound, B-mode images provide morphological details of a lesion, while Doppler images capture vascularity features; their fusion creates a more discriminative feature representation for classification [5]. Similarly, in lung cancer, combining the spatial patterns from CT scans with contextual clinical features like demographic, symptomatic, and genetic factors allows for both precise tissue classification and accurate severity assessment [6]. These examples underscore that fusion models reduce ambiguity and provide richer context, leading to more accurate and robust predictions than any single modality can achieve [2].

Core Technical Fusion Strategies and Protocols

The technical implementation of multimodal data fusion can be categorized into several core strategies, which determine when in the analytical pipeline the different data streams are integrated. The choice of strategy is critical and depends on factors such as data alignment, heterogeneity, and the specific clinical task.

Fusion Strategy Protocol

The three primary fusion strategies are early, intermediate, and late fusion, each with distinct advantages and implementation protocols.

Table 2: Protocols for Core Multimodal Data Fusion Strategies

| Fusion Strategy | Definition & Protocol | Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Fusion (Feature-Level) [2] [4] | Protocol: Raw or minimally processed data from multiple modalities are combined into a single input vector before being fed into a model.Technical Note: Requires data to be synchronized and spatially aligned, often necessitating extensive preprocessing. | Allows the model to learn complex, low-level interactions between modalities directly from the data. | Highly sensitive to data alignment and noise; difficult to handle heterogeneous data rates/formats. | Fusing co-registered imaging data from the same patient (e.g., different MRI sequences). |

| Intermediate Fusion (Hybrid) [2] [4] | Protocol: Modalities are processed separately in initial layers to extract high-level features. These modality-specific features are then combined at an intermediate layer of the model for joint learning.Technical Note: Employs architectures like cross-attention transformers to dynamically weight features. | Balances modality-specific processing with joint representation learning; captures interactions at a meaningful feature level. | More complex model architecture and training; requires careful design of fusion layer. | Integrating inherently different data types (e.g., images and genomic vectors) where alignment is not trivial. |

| Late Fusion (Decision-Level) [2] [4] | Protocol: Each modality is processed by a separate model to yield an independent prediction or decision. These decisions are then combined via weighted averaging, voting, or another meta-classifier.Technical Note: The weighting of each modality's vote can be learned or heuristic. | Highly flexible; can handle asynchronous data and missing modalities easily. | Cannot model cross-modal interactions or dependencies; may miss synergistic information. | Integrating predictions from pre-trained, single-modality models or when data streams are inherently asynchronous. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and the architectural differences between the three primary fusion strategies.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: HXM-Net for Breast Ultrasound

The following section provides a detailed, replicable protocol for implementing a state-of-the-art multimodal fusion model, HXM-Net, designed for breast cancer diagnosis using multi-modal ultrasound [5]. This can serve as a template for researchers developing similar pipelines.

Aim and Principle

To improve the accuracy of breast tumor classification (benign vs. malignant) by synergistically combining morphological information from B-mode ultrasound, vascular features from Color Doppler, and tissue stiffness information from Elastography [5]. The principle is that a hybrid CNN-Transformer architecture can optimally extract and fuse these complementary features to create a more informative and discriminative representation than any single modality provides.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for HXM-Net Protocol

| Item / Solution | Function / Specification | Handling & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Class-balanced Breast Ultrasound Dataset | Contains paired B-mode, Color Doppler, and Elastography images for each lesion. | Essential to mitigate class imbalance. Ensure patient identifiers are removed for privacy. |

| Image Preprocessing Library (e.g., OpenCV, SciKit-Image) | For image resizing, normalization, and data augmentation (rotation, flipping, etc.). | Augmentation is crucial for model generalizability across different patient populations and imaging machines. |

| Deep Learning Framework (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow) | To implement and train the HXM-Net architecture. | Must support both CNN and Transformer modules. |

| High-Performance Computing Unit (GPU with >8GB VRAM) | To handle the computational load of training complex deep learning models. | Necessary for efficient training and hyperparameter optimization. |

| Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM) | To generate visual explanations for the model's predictions, enhancing clinical interpretability. | A key component for Explainable AI (XAI), helping to build clinician trust. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Data Curation and Preprocessing:

- Data Sourcing: Obtain a dataset of breast ultrasound cases where each lesion has corresponding B-mode, Color Doppler, and Elastography images. The dataset should be annotated with ground-truth labels (benign/malignant) confirmed by biopsy.

- Image Cleaning and Standardization: Resize all images to a uniform spatial resolution (e.g., 224x224 pixels). Normalize pixel intensities to a [0, 1] range.

- Data Augmentation: Apply random data augmentation techniques to the training set, including rotation (±15°), horizontal and vertical flipping, and slight brightness/contrast adjustments, to improve model robustness.

Model Architecture Implementation (HXM-Net):

- Feature Extraction Backbone: Implement a multi-stream Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). Each stream—one for each ultrasound modality—uses a CNN (e.g., a ResNet-50 backbone, pre-trained on ImageNet and fine-tuned) to extract high-level spatial features.

- Transformer-based Fusion Module: Flatten the feature maps from each CNN stream and project them into a sequence of embedding vectors. Feed the concatenated embeddings from all modalities into a Transformer encoder.

- The Self-Attention Mechanism within the Transformer is calculated as

Attention(Q, K, V) = softmax((QK^T) / √d_k) V, where Q (Query), K (Key), and V (Value) are matrices derived from the input embeddings [5]. This mechanism allows the model to dynamically weight the importance of features both within and across the different modalities. - Classification Head: Use the [CLS] token output or the mean-pooled output of the Transformer encoder, and pass it through a final fully connected layer with a softmax activation function to generate the final classification (benign or malignant).

Model Training and Validation:

- Loss Function and Optimizer: Use a binary cross-entropy loss function and an Adam optimizer.

- Training Regimen: Train the model using a k-fold cross-validation strategy (e.g., k=5 or k=10) to ensure robustness and reduce overfitting. Monitor performance on a held-out validation set.

- Explainability Analysis: After training, apply Grad-CAM to the model's CNN streams to generate heatmaps highlighting the image regions most influential in the prediction. This provides critical, human-interpretable insights for clinical validation.

HXM-Net Architecture Visualization

The following diagram details the core architecture of the HXM-Net model as described in the protocol.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Models

This section provides a consolidated reference table of key computational tools and data types essential for research in multimodal data fusion for cancer diagnostics.

Table 4: Essential Research Toolkit for Multimodal Fusion in Cancer Diagnostics

| Tool / Reagent Category | Specific Examples & Notes | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Data Modalities | Multi-omics: Genomic (mutations), Transcriptomic (RNA-seq), Proteomic, Metabolomic [1] [4].Medical Imaging: Histopathology slides, CT, MRI, Ultrasound (B-mode, Doppler, Elastography) [1] [5].Clinical Data: Electronic Health Records (EHRs), patient demographics, symptoms, lab results [1] [6]. | Provide the raw, orthogonal data streams that contain complementary information about the disease state. |

| AI/Model Architectures | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs): For spatial feature extraction from images [5] [6].Transformers: For cross-modal fusion and capturing long-range dependencies via self-attention [5].Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs): For processing structured, non-image data (e.g., clinical features) [6]. | Serve as the core computational engines for feature extraction, fusion, and prediction. |

| Fusion Frameworks | Early/Intermediate Fusion: Simple operations (concatenation, weighted sum) or attention-based fusion [4].Late Fusion: Weighted averaging or meta-classifiers on model outputs [2] [4].Advanced Methods: Multimodal embeddings, graph-based fusion [4] [7]. | Define the strategy and algorithmic approach for integrating information from different modalities. |

| Explainability (XAI) Tools | Gradient-weighted Class Activation Mapping (Grad-CAM): For visualizing salient regions in images [6].SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP): For interpreting feature importance in any model, including ANNs [6]. | Provide interpretability and transparency for model decisions, which is critical for clinical adoption. |

| Computational Infrastructure | GPU-Accelerated Computing: (e.g., NVIDIA).Deep Learning Frameworks: PyTorch, TensorFlow.Medical Imaging Platforms: MONAI (Medical Open Network for AI) [3]. | Provide the necessary hardware and software environment for developing and training complex models. |

Technological advancements have ushered in an era of high-throughput biomedical data, enabling the comprehensive study of biological systems through different "omics" layers [8]. In oncology, the integration of these modalities—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—is transforming cancer research by providing unprecedented insights into tumour biology [9] [10]. Each omics layer offers a unique perspective: genomics provides the blueprint of hereditary and acquired mutations, transcriptomics reveals dynamic gene expression patterns, proteomics identifies functional effectors and their modifications, and metabolomics captures the functional readout of cellular biochemical activity [11] [12]. Multi-modal data fusion leverages these complementary perspectives to create a more holistic understanding of cancer development, progression, and treatment response, ultimately advancing precision oncology [13] [1].

Table 1: Core Omics Modalities: Definitions and Molecular Targets

| Omics Modality | Core Definition | Primary Molecular Target | Key Analytical Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Study of the complete set of DNA, including all genes, their sequences, interactions, and functions [11] [14]. | DNA (Deoxyribonucleic Acid) | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), Sanger Sequencing, Microarrays [8] [9] |

| Transcriptomics | Analysis of the complete set of RNA transcripts produced by the genome under specific circumstances [9] [12]. | RNA (Ribonucleic Acid), including mRNA | RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq), Microarrays [8] [1] |

| Proteomics | Study of the structure, function, and interactions of the complete set of proteins (the proteome) in a cell or organism [9] [12]. | Proteins and their post-translational modifications | Mass Spectrometry (MS), Protein Microarrays [10] [12] |

| Metabolomics | Comprehensive analysis of the complete set of small-molecule metabolites within a biological sample [9] [11]. | Metabolites (e.g., lipids, amino acids, carbohydrates) | Mass Spectrometry (MS), Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy [9] [14] |

Application Notes in Oncology

Genomics and Genetic Variations in Cancer

Genomics investigates the complete set of DNA in an organism, providing a foundational understanding of genetic predispositions and somatic mutations that drive oncogenesis [8] [11]. In cancer, genomic analyses focus on identifying key variations, including driver mutations that confer growth advantage, copy number variations (CNVs) that alter gene dosage, and single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) that may influence cancer risk and therapeutic response [9]. For instance, the amplification of the HER2 gene is a critical genomic event in approximately 20% of breast cancers, leading to aggressive tumour behaviour and serving as a target for therapies like trastuzumab [9]. Similarly, mutations in the TP53 tumour suppressor gene are found in about half of all human cancers [9].

Transcriptomics for Gene Expression Profiling

Transcriptomics captures the dynamic expression of all RNA transcripts, reflecting the active genes in a cell at a specific time and under specific conditions [11] [12]. This modality is crucial for understanding how genomic blueprints are executed and how they change in disease states. In cancer research, transcriptomics enables the classification of molecular subtypes with distinct clinical outcomes, as exemplified by the PAM50 gene signature for breast cancer [1]. It can also reveal mechanisms of drug resistance and immune activation within the tumour microenvironment [1]. Tests based on transcriptomic profiles, such as Oncotype DX, are used in the clinic to assess recurrence risk and guide chemotherapy decisions [1].

Proteomics for Functional Analysis

Proteomics moves beyond the genetic code to study the proteins that execute cellular functions, offering a more direct view of cellular activities and signalling pathways [12]. The proteome is highly dynamic and influenced by post-translational modifications, which are not visible at the genomic or transcriptomic levels [9]. In cancer, proteomic profiling can identify functional protein biomarkers for diagnosis, elucidate dysregulated signalling pathways for targeted therapy, and characterize the immune context of tumours to predict response to immunotherapy [10] [1]. Proteomics can be approached through expression proteomics (quantifying protein levels), structural proteomics (mapping protein locations), and functional proteomics (determining protein interactions and roles) [12].

Metabolomics as a Phenotypic Readout

Metabolomics studies the complete set of small-molecule metabolites, representing the ultimate downstream product of genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic activity [11]. As such, it provides a snapshot of the physiological state of a cell and is considered a close link to the phenotype [9] [11]. Cancer cells often exhibit reprogrammed metabolic pathways to support rapid growth and proliferation. Metabolomics can uncover these alterations, revealing potential biomarkers for early detection and novel therapeutic targets [9]. It is increasingly used to study a range of conditions, including obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, and various cancers, and to understand individual responses to environmental factors and drugs [12].

Table 2: Omics Applications in Cancer Diagnosis and Prognosis

| Omics Modality | Representative Cancer Applications | Strengths | Limitations & Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | - Identification of driver mutations (e.g., TP53) [9]- HER2 amplification testing in breast cancer [9]- Risk assessment via SNPs (e.g., BRCA1/2) [9] | - Foundation for personalized medicine [9]- Comprehensive view of genetic variation [9] | - Does not account for gene expression or environmental influence [9]- Large data volume and complexity [9] |

| Transcriptomics | - Molecular subtyping (e.g., PAM50 for breast cancer) [1]- Prognostic tests (e.g., Oncotype DX) [1]- Analysis of tumour microenvironment [1] | - Captures dynamic gene expression changes [9]- Reveals regulatory mechanisms [9] | - RNA is less stable than DNA [9]- Provides a snapshot view, not long-term [9] |

| Proteomics | - Biomarker discovery for diagnosis [10]- Drug target identification [9]- Analysis of post-translational modifications [9] | - Directly measures functional effectors [9]- Links genotype to phenotype [9] | - Proteome is complex and has a large dynamic range [9]- Difficult quantification and standardization [9] |

| Metabolomics | - Discovery of metabolic biomarkers for early detection [9]- Investigating metabolic rewiring in cancer [12]- Monitoring treatment response [12] | - Direct link to phenotype [9]- Can capture real-time physiological status [9] | - Metabolome is highly dynamic [9]- Limited reference databases [9] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Omic Data Generation from Tumour Tissue

This protocol outlines the steps for generating genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data from a single tumour tissue sample, a common approach in studies like The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [10].

I. Sample Collection and Preparation

- Tissue Acquisition: Obtain fresh tumour tissue via biopsy or surgical resection. Immediately snap-freeze a portion of the tissue in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C to preserve nucleic acids, proteins, and metabolites.

- Sectioning: Cryosection the frozen tissue into multiple sequential slices (e.g., 10-20 μm thickness).

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Use one section for simultaneous DNA and RNA extraction using a commercial kit that ensures high purity and integrity. Assess DNA and RNA quality using spectrophotometry (e.g., Nanodrop) and bioanalyzer (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer for RNA Integrity Number, RIN).

- Protein and Metabolite Extraction: From a parallel section, homogenize the tissue. Split the homogenate:

- For proteomics, lyse the tissue in an appropriate buffer (e.g., RIPA with protease and phosphatase inhibitors). Centrifuge to clear debris.

- For metabolomics, extract metabolites using a solvent system like methanol:acetonitrile:water to precipitate proteins and recover a wide range of polar and non-polar metabolites.

II. Data Generation

- Genomics (Whole Exome Sequencing - WES):

- Library Prep: Fragment genomic DNA and perform hybrid capture-based enrichment of exonic regions using a kit (e.g., Illumina Nextera Flex for Enrichment).

- Sequencing: Sequence the libraries on a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) to a minimum depth of 100x.

- Transcriptomics (RNA Sequencing - RNA-Seq):

- Library Prep: Deplete ribosomal RNA or enrich for poly-adenylated RNA from total RNA. Prepare sequencing libraries (e.g., Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA kit).

- Sequencing: Sequence on a platform like Illumina HiSeq or NovaSeq to generate at least 30 million paired-end reads per sample.

- Proteomics (Data-Independent Acquisition Mass Spectrometry - DIA-MS):

- Digestion: Digest proteins from the lysate with trypsin.

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): Separate peptides by liquid chromatography and analyze using a DIA method on a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Thermo Scientific Orbitrap Exploris 480).

- Metabolomics (Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry - LC-MS):

- Analysis: Separate the metabolite extract using reversed-phase or HILIC chromatography coupled to a high-resolution mass spectrometer (e.g., Thermo Scientific Q-Exactive).

- Polarity: Run the analysis in both positive and negative ionization modes to maximize metabolite coverage.

Protocol 2: A Basic Computational Workflow for Multi-Omic Data Integration

This protocol describes a foundational bioinformatics pipeline for integrating the generated data, inspired by machine learning approaches for survival prediction [13] [1].

I. Preprocessing and Quality Control (Per Modality)

- Genomics:

- Variant Calling: Align sequencing reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using a tool like BWA-MEM. Call somatic variants (SNVs, indels) using GATK Best Practices or a tool like MuTect2 [1].

- Transcriptomics:

- Quantification: Align RNA-Seq reads with a splice-aware aligner (e.g., STAR) and quantify gene-level counts using featureCounts.

- Normalization: Perform normalization (e.g., TPM, DESeq2's median of ratios) and, if needed, batch correction (e.g., using ComBat).

- Proteomics:

- Quantification: Process DIA-MS data using software like Spectronaut or DIA-NN to obtain protein abundance values.

- Normalization: Normalize abundances (e.g., by median) and log2-transform.

- Metabolomics:

- Peak Picking and Annotation: Use software like XCMS or MS-DIAL for peak picking, alignment, and annotation against metabolite databases (e.g., HMDB).

- Normalization: Normalize peak intensities (e.g., by sum, PQN) and log-transform.

II. Feature Extraction and Fusion

- Dimensionality Reduction: For each preprocessed omics matrix, perform dimensionality reduction to mitigate the "curse of dimensionality" and reduce noise [13] [1].

- Data Fusion Strategy: Employ a "late fusion" or "model-level fusion" strategy, which is effective when dealing with high-dimensional data and limited samples [13].

- Step 1: Train Single-Modality Models. Train a predictive model (e.g., a Cox proportional hazards model or a Random Survival Forest) for each omics modality using the extracted features.

- Step 2: Fuse Predictions. Combine the predictions from each single-modality model (e.g., by averaging or using a stacked ensemble) to generate a final, integrated prediction [13].

Visualization of Multi-Omic Integration for Cancer Research

Diagram 1: Multi-Omic Data Integration Workflow for Clinical Insight

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for Omics Technologies

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Example / Vendor |

|---|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencer | High-throughput parallel sequencing of DNA and RNA libraries. | Illumina NovaSeq 6000 System; PacBio Sequel IIe System [8] [10] |

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer | Precise identification and quantification of proteins and metabolites. | Thermo Scientific Orbitrap Exploris Series; Sciex TripleTOF Systems [10] [1] |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-purity, intact genomic DNA and total RNA from tissue. | Qiagen AllPrep DNA/RNA/miRNA Universal Kit; Zymo Research Quick-DNA/RNA Miniprep Kit |

| Protein Lysis Buffer | Efficient extraction of proteins from tissue/cells while maintaining stability. | RIPA Lysis Buffer (with protease and phosphatase inhibitors) [1] |

| Metabolite Extraction Solvent | Comprehensive extraction of polar and non-polar metabolites for LC-MS. | Methanol:Acetonitrile:Water (e.g., 40:40:20) solvent system [1] |

| Library Prep Kit for WES | Preparation of sequencing libraries with enrichment for exonic regions. | Illumina Nextera Flex for Enrichment; Agilent SureSelect XT HS2 [8] |

| Library Prep Kit for RNA-Seq | Preparation of stranded RNA-Seq libraries, often with mRNA enrichment. | Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA Kit; NEBnext Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit |

| Trypsin, Sequencing Grade | Proteolytic enzyme for specific digestion of proteins into peptides for MS. | Trypsin, Sequencing Grade (e.g., from Promega or Roche) [1] |

Technological advances now make it possible to study a patient from multiple angles with high-dimensional, high-throughput multi-scale biomedical data [10]. In oncology, massive amounts of data are being generated ranging from molecular, histopathology, radiology to clinical records [10]. The introduction of deep learning has significantly advanced the analysis of biomedical data, yet most approaches focus on single data modalities, leading to slow progress in methods to integrate complementary data types [10]. Development of effective multimodal fusion approaches is becoming increasingly important as a single modality might not be consistent and sufficient to capture the heterogeneity of complex diseases like cancer to tailor medical care and improve personalised medicine [10].

Multi-modal data fusion technology integrates information from different modality imaging, which can be comprehensively analyzed by imaging fusion systems [15]. This approach provides more imaging information of tumors from different dimensions and angles, offering strong technical support for the implementation of precision oncology [15]. The integration of data modalities that cover different scales of a patient has the potential to capture synergistic signals that identify both intra- and inter-patient heterogeneity critical for clinical predictions [10]. For example, the 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system (CNS) revisited the guidelines to classify diffuse gliomas recommending histopathological diagnosis in combination with molecular markers [10].

Medical Imaging Modalities: Technical Foundations and Applications

Digital Pathology and Whole Slide Imaging (WSI)

Digital pathology, the process of "digitising" conventional glass slides to virtual images, has many practical advantages over more traditional approaches, including speed, more straightforward data storage and management, remote access and shareability, and highly accurate, objective, and consistent readouts [10]. Whole slide images (WSIs) are critical for cancer diagnosis but pose computational challenges due to their gigapixel resolution [16]. These large (~1 GB) images, containing gigapixels of data, pose significant challenges for deep learning pipelines—not because of model design limitations, but due to the substantial computational demands they impose, including memory usage, I/O throughput, and GPU processing capabilities [16].

Fine-tuning pre-trained models or using multiple-instance learning (MIL) are common approaches, especially when only WSI-level labels are available [16]. ROIs are defined using expert annotations, pre-trained segmentation models, or image features, and MIL aggregates patch information for supervision [16]. Several MIL-based methods have been developed for WSI classification, including ABMIL, ACMIL, TransMIL, and DSMI, each addressing traditional MIL limitations [16].

Radiological Imaging: CT and MRI

Computed Tomography (CT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans are useful for generating 3D images of (pre)malignant lesions [10]. CT is based on anatomical imaging while MRI has higher soft-tissue resolution than CT and causes no radiation damage [15]. Radiomics refers to the field focusing on the quantitative analysis of radiological digital images with the aim of extracting quantitative features that can be used for clinical decision-making [10]. This extraction used to be done with standard statistical methods, but more advanced deep learning (DL) frameworks like convolutional neural networks (CNN), deep autoencoders (DAN) and vision transformers (ViTs) are now available for automated, high-throughput feature extraction [10].

Radiomics and Feature Extraction

The concept of radiomics was first formally introduced by Lambin et al. in 2012, and later further refined and expanded in 2017 [17]. Radiomics utilizes computational algorithms to extract a wide range of high-dimensional, quantifiable features from medical imaging, such as shape, texture, intensity distribution, and contrast, which can reflect the tumor's microstructure and biological behavior, and subsequently assist in disease diagnosis and treatment [17]. Traditional radiomics methods typically rely on two-dimensional imaging data and predefined feature extraction techniques, which may overlook the full spatial heterogeneity of the tumor [17].

Table 1: Comparison of Medical Imaging Modalities in Oncology

| Modality | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Technical Limitations | Data Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital Pathology (WSI) | Cancer diagnosis, subtype classification, tissue architecture analysis | Detailed cellular and morphological information; gold standard for diagnosis | Gigapixel resolution requires patch-based processing; computational demands | Whole slide images (1GB+); requires multiple-instance learning |

| CT (Computed Tomography) | Tumor localization, staging, radiotherapy planning | Fast acquisition; excellent spatial resolution; 3D reconstruction | Ionizing radiation; limited soft-tissue contrast | Anatomical imaging; quantitative texture/shape features |

| MRI (Magnetic Resonance) | Soft-tissue characterization, treatment response assessment | Superior soft-tissue contrast; multi-parametric imaging; no radiation | Longer acquisition times; more expensive | Functional and metabolic information; multi-sequence data |

| Radiomics | Prognostic prediction, biomarker discovery, heterogeneity quantification | High-dimensional feature extraction; captures tumor heterogeneity | Dependency on image quality; requires standardization | 1000+ quantitative features; shape, texture, intensity patterns |

Multi-Modal Fusion Architectures and Methodologies

Fusion Strategies and Technical Approaches

Multimodal feature fusion strategies mainly include early fusion, late fusion, and hybrid fusion [18]. Early fusion concatenates features from multiple modalities at the shallow layers (or input layers) of the model, followed by a cascaded deep network structure, and ultimately connects to the classifier or other models [18]. Early fusion learns the correlations between the low-level features of each modality. As it only requires training a single unified model, its complexity is manageable. However, early fusion faces challenges in feature concatenation due to the different sources of data from multiple modalities [18].

Late fusion involves independently training multiple models for each modality, where each modality undergoes feature extraction through separate models [18]. The extracted features are then fused and connected to a classifier for final classification [18]. Hybrid fusion combines the principles of both early and late fusion [18]. Since early fusion integrates multiple modalities at the shallow layers or input layers, it is suitable for cases with minimal differences between the modalities [18].

Multi-Modal Fusion Implementation Workflow

Application Notes: Experimental Results and Performance Metrics

Multi-Modal Fusion Performance Across Cancer Types

Multiple studies have demonstrated the superior performance of multimodal approaches compared to unimodal models across various cancer types. The integration of complementary data sources consistently enhances predictive accuracy for diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment response assessment.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Multi-Modal vs Uni-Modal Models in Oncology

| Cancer Type | Modalities Fused | Model Architecture | Primary Task | Performance (Multimodal) | Performance (Best Uni-Modal) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic Cancer [17] | CT Radiomics + 3D Deep Learning + Clinical | Radiomics-RSF + 3D-DenseNet + Logistic Regression | Survival Prediction | AUC: 0.87 (1-y), 0.92 (2-y), 0.94 (3-y) | Radiomics AUC: 0.78 (1-y), 0.85 (2-y), 0.91 (3-y) |

| Breast Cancer [19] | Ultrasound + Radiology Reports | Image/Text Encoders + Transformation Layer | Benign/Malignant Classification | Youden Index: +6-8% over unimodal | Image-only or text-only models |

| Breast Cancer (NAT Response) [20] | Mammogram + MRI + Clinical + Histopathological | iMGrhpc + iMRrhpc with temporal embedding | pCR Prediction Post-NAT | AUROC: 0.883 (Pre-NAT), 0.889 (Mid-NAT) | Uni-modal ΔAUROC: 10.4% (p=0.003) |

| Head and Neck SCC [21] | CT + WSI + Clinical | Multimodal DL (MDLM) with Cox regression | Overall Survival Prediction | C-index: 0.745 (internal), 0.717 (external) | CT-only or WSI-only models |

| Breast Cancer [18] | Mammography + Ultrasound | Late Fusion with Multiple DL Models | Benign/Malignant Classification | AUC: 0.968, Accuracy: 93.78% | Single modality models |

| Kidney & Lung Cancer [16] | WSI + Pathology Reports | MPath-Net (MIL + Sentence-BERT) | Cancer Subtype Classification | Accuracy: 94.65%, F1-score: 0.9473 | WSI-only or text-only baselines |

Technical Protocols for Multi-Modal Implementation

Protocol 1: Radiomics-3D Deep Learning Fusion for Pancreatic Cancer

Application: Survival prediction in pancreatic cancer patients [17]

Materials and Methods:

- Patient Cohort: 880 eligible patients split into training (n=616) and testing (n=264) sets in 7:3 ratio

- Imaging Data: Portal venous phase contrast-enhanced CT images

- ROI Delineation: Two physicians independently delineated tumor regions with third expert arbitration for discrepancies

- Feature Extraction:

- Radiomics: 1,037 features extracted using 3D Slicer Radiomics plugin

- Deep Learning: 3D-DenseNet trained on ROI-based image inputs

- Model Development:

- Radiomics features reduced via PCA and LASSO regression

- Random Survival Forest for survival prediction

- Fusion with clinical variables using multiple classifiers

- Validation: Internal-external validation via train-test split; performance evaluated using ROC curves, AUC, and accuracy

Key Parameters:

- Image resampling to 3×3×3 mm³ voxel size for isotropy

- Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for ROI consistency validation

- Binary classification at 1-, 2-, and 3-year survival time points

Protocol 2: Multi-Modal Breast Cancer Neoadjuvant Therapy Response Prediction

Application: Predicting pathological complete response (pCR) in breast cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy [20]

Materials and Methods:

- Patient Cohort: 3,352 patients from multiple centers with longitudinal data

- Modalities Integrated:

- Pre-NAT mammogram exams (4,802 exams)

- Longitudinal MRI exams (3,719 exams)

- Histopathological information (molecular subtype, tumor histology)

- Personal factors (age, menopausal status, genetic mutations)

- Clinical data (cTNM staging, therapy details)

- Model Architecture:

- iMGrhpc: Processes Pre-NAT mammogram + rhpc data

- iMRrhpc: Handles longitudinal MRI + rhpc data

- Cross-modal knowledge mining strategy

- Temporal information embedding for longitudinal data

- Validation: Multi-center studies and multinational reader studies comparing model performance to breast radiologists

Key Parameters:

- Handles missing modalities through flexible architecture

- Robust to different NAT settings across hospitals

- Output: pCR probability for surgical decision support

Protocol 3: Whole Slide Image and Pathology Report Fusion

Application: Cancer subtype classification for kidney and lung cancers [16]

Materials and Methods:

- Data Source: TCGA dataset (1,684 cases: 916 kidney, 768 lung)

- Modalities: WSIs and corresponding pathology reports

- Feature Extraction:

- WSI: Multiple-instance learning (MIL) for gigapixel image processing

- Text: Sentence-BERT for report encoding

- Fusion Architecture:

- 512-dimensional image and text embeddings concatenated

- Joint fine-tuning with trainable fusion layers

- End-to-end training with image encoder fine-tuned and text encoder frozen

- Validation: Comparative analysis against state-of-the-art MIL methods

Key Parameters:

- Weakly supervised learning requiring only slide-level labels

- Attention heatmaps for interpretable tumor localization

- Cross-modal alignment through joint representation learning

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Multi-Modal Oncology Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Examples | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Slicer [17] | Software Platform | Medical image visualization and processing | Radiomic feature extraction; ROI delineation | Open-source; extensible architecture; radiomics plugin |

| PyTorch [16] | Deep Learning Framework | Model development and training | Implementing MIL algorithms; custom fusion architectures | GPU acceleration; dynamic computation graphs |

| YOLOv8 [18] | Object Detection Model | Automated tumor region localization | Preprocessing ultrasound images for analysis | Real-time processing; high accuracy |

| Sentence-BERT [16] | NLP Framework | Text embedding generation | Processing pathology reports for multimodal fusion | Semantic similarity preservation; medical text optimization |

| TransMIL [16] | Multiple Instance Learning | WSI classification and analysis | Cancer subtype classification from whole slides | Transformer-based; attention mechanisms |

| TCGA [10] [16] | Data Repository | Multi-modal cancer datasets | Access to matched imaging, genomic, clinical data | 33 cancer types; standardized data formats |

| ResNet/3D-DenseNet [17] | Deep Learning Architecture | Feature extraction from images | 3D tumor characterization from CT volumes | Spatial context preservation; hierarchical feature learning |

Multimodal data fusion represents a paradigm shift in cancer diagnostics and research methodology. The integration of digital pathology, radiological imaging (CT, MRI), and radiomics features has consistently demonstrated superior performance compared to single-modality approaches across various cancer types [10] [15]. Technical implementations including early, late, and hybrid fusion strategies provide flexible frameworks for combining complementary data sources, while advanced deep learning architectures enable effective feature extraction and alignment across modalities [18].

The experimental protocols and application notes detailed in this document provide researchers with practical methodologies for implementing multi-modal fusion in oncological research. As the field advances, key challenges remain including handling missing data, improving model interpretability, and ensuring generalizability across diverse patient populations and imaging protocols [22]. Future directions will likely focus on standardized data acquisition protocols, federated learning approaches for multi-institutional collaboration, and the development of more biologically-informed fusion architectures that better capture the complex relationships between imaging features and underlying tumor biology [20] [21].

The integration of Electronic Health Records (EHRs) with other data modalities represents a transformative opportunity in cancer research. EHRs provide comprehensive clinical data on patient history, treatments, and outcomes, while patient-generated health data offers real-world insights into symptoms and quality of life. When fused with genomic, proteomic, and imaging data, these clinical and real-world data sources enable a more holistic understanding of cancer biology and patient experience. However, significant challenges exist in harnessing these data effectively. Current EHR systems often fragment information across multiple platforms, with one study reporting that 92% of gynecological oncology professionals routinely access multiple EHR systems, and 17% spend over half their clinical time searching for patient information [23]. Furthermore, data heterogeneity, lack of interoperability, and inconsistent documentation practices create substantial barriers to multimodal data integration [24] [25]. This application note details methodologies and protocols to overcome these challenges and leverage EHR data within multimodal cancer research frameworks.

Key Challenges in EHR Data Utilization for Cancer Research

Data Fragmentation and Interoperability

EHR data in oncology is typically scattered across multiple systems including clinical trials data, pathology reports, laboratory results, and symptom tracking platforms [24]. This fragmentation is particularly problematic in cancer care characterized by complex, multidisciplinary coordination over extended periods [23]. The lack of standardization across systems and institutions leads to incompatible formats and terminologies, hampering collaborative research efforts [24].

Table 1: Key Challenges in EHR Utilization for Multimodal Cancer Research

| Challenge Category | Specific Issues | Impact on Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Fragmentation | Information scattered across multiple systems (29% of professionals use ≥5 systems) [23] | Incomplete patient journey mapping; missing critical data points |

| Interoperability | Lack of standardized formats and terminologies across institutions [24] | Difficulties in data exchange and collaborative research |

| Data Quality | Unstructured formats; high degree of missingness [13] [24] | Skewed analysis; compromised model performance |

| Workflow Integration | 17% of clinicians spend >50% of time searching for information [23] | Reduced efficiency; limited time for research activities |

Data Completeness and Quality Issues

Cancer research databases frequently suffer from incomplete clinical data, with key information such as cancer staging, biomarkers, and survival time often missing [24]. In structured oncology data platforms, critical elements like staging and molecular data may be absent in up to 50% of patient records [24]. This missingness can systematically skew survival analyses and other outcomes research [24]. Additionally, EHR data often contains unstructured elements that require expensive manual abstraction and curation [24].

Methodologies for EHR Data Processing and Integration

Data Standardization and Harmonization

The ICGC ARGO Data Dictionary provides a robust framework for standardizing global cancer clinical data collection. This framework employs an event-based data model that captures clinical relationships and supports longitudinal data collection [24]. The dictionary defines:

- Core Fields: Mandatory clinical parameters required for each cancer patient

- Extended Fields: Optional elements for specific research questions

- Conditional Fields: Required only when specific conditions are met [24]

This approach ensures consistent high-quality clinical data collection across diverse cancer types and geographical regions while maintaining interoperability with other standards like Minimal Common Oncology Data Elements (mCODE) [24].

Natural Language Processing for Unstructured Data

Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques enable transformation of unstructured clinical notes, diagnostic reports, and other text-based EHR elements into structured, analyzable data [26]. NLP has been successfully applied to automate extraction of patient outcomes, progression-free survival data, and other tumor features from clinical narratives [26]. Implementation protocols for NLP in oncology EHR data include:

- Clinical Note Processing: Extraction of genomic and surgical information from free-text records [23]

- Symptom Data Abstraction: Processing of electronic patient-reported outcome measures (ePROs) for symptom monitoring [27]

- Outcome Automation: Gathering progression-free survival and other temporal metrics from clinical documentation [26]

Transformer-Based Patient Embedding

Advanced representation learning methods enable powerful patient stratification from longitudinal EHR data. The transformer-based embedding approach processes high-dimensional EHR data at the patient level to characterize heterogeneity in complex diseases [28]. This methodology involves:

- Vocabulary Embedding: Creating embeddings of medical codes (diagnoses, procedures) using variational autoencoder neural network architecture

- Sequence Processing: Feeding embedded codes to a transformer model that represents each patient's longitudinal visits as sequences

- Patient Vector Generation: Implementing sentence-BERT architecture to transform 2-D vector outputs into 1-D patient embedding vectors [28]

This approach has demonstrated strong predictive performance for future disease onset (median AUROC = 0.87 within one year) and effectively reveals diverse comorbidity profiles and disease progression patterns [28].

Experimental Protocols for Multimodal Data Integration

Protocol: Late Fusion for Survival Prediction

Application Note: This protocol describes a late fusion strategy for integrating multimodal data to predict overall survival in cancer patients, particularly effective with high-dimensional omics data and limited sample sizes [13].

Materials and Reagents:

- Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Multimodal Data Fusion

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| AZ-AI Multimodal Pipeline | Python library for multimodal feature integration and survival prediction [13] | Includes preprocessing, dimensionality reduction, and model training modules |

| TCGA Data | Provides transcripts, proteins, metabolites, and clinical factors for model training [13] | Includes lung, breast, and pan-cancer datasets |

| Feature Selection Methods | Pearson/Spearman correlation for high-dimensional omics data [13] | Addresses challenges of low signal-to-noise ratio |

| Ensemble Survival Models | Gradient boosting, random forests for survival prediction [13] | Outperforms single models in multimodal settings |

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Apply modality-specific preprocessing to address missingness and batch effects

- Normalize each data modality separately (transcripts, proteins, metabolites, clinical factors)

Feature Extraction:

- Perform dimensionality reduction on each modality independently

- Apply linear or monotonic feature selection methods (Pearson/Spearman correlation) suitable for high-dimensional omics data [13]

Unimodal Model Training:

- Train separate survival models for each data modality

- Utilize ensemble methods (gradient boosting, random forests) that outperform deep neural networks on tabular multi-omics data [13]

Late Fusion Integration:

- Combine predictions from unimodal models rather than raw features

- Weight each modality based on its informativeness for survival prediction [13]

Model Evaluation:

- Implement rigorous evaluation with multiple training-test splits

- Report C-indices with confidence intervals to account for uncertainty [13]

Validation: Late fusion models consistently outperformed single-modality approaches in TCGA lung, breast, and pan-cancer datasets, offering higher accuracy and robustness for survival prediction [13].

Protocol: Clinical Decision Support Integration

Application Note: This protocol details the integration of Clinical Decision Support (CDS) systems into EHR workflows for precision symptom management in cancer patients [27].

Procedure:

- Algorithm Development:

- Create symptom management algorithms for key cancer symptoms (e.g., pain, fatigue, nausea)

- Program algorithms into CDS platform using application programming interfaces and interoperable data standards

EHR Integration:

- Integrate CDS into existing EHR systems using interoperable data standards

- Generate individually tailored symptom management recommendations based on EHR and patient-reported data

Validation and Testing:

- Test system using test patients that reflect real-world patient experiences

- Have clinicians verify critical elements to assure accuracy and safety of recommendations [27]

Implementation Framework and Future Directions

Co-Design of Integrated Informatics Platforms

A human-centered design approach involving healthcare professionals, data engineers, and informatics experts is essential for developing effective EHR-integrated research platforms [23]. This methodology includes:

- Multidisciplinary Collaboration: Engaging end-users throughout development to ensure workflow compatibility

- Data Pipeline Validation: Clinicians validating extracted data against original clinical system sources

- Unified Visualization: Consolidating disparate patient data from different EHR systems into a single visual display to support clinical decision-making [23]

Emerging Technologies and Methodologies

Future advancements in EHR-based cancer research will leverage:

- Federated Learning: Enabling model training across institutions without sharing sensitive patient data [29]

- Synthetic Data Generation: Addressing data scarcity while preserving privacy [29]

- Explainable AI (XAI): Enhancing model interpretability for clinical adoption [29]

- Advanced Transformer Architectures: Improving temporal modeling of patient journeys across longer time horizons [28]

Table 3: Performance Metrics for EHR Data Integration Methods

| Methodology | Application | Performance Metrics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer Patient Embedding | Disease onset prediction | Median AUROC = 0.87 (within one year) | [28] |

| Late Fusion Multimodal Integration | Cancer survival prediction | Outperformed single-modality approaches across TCGA datasets | [13] |

| Clinical Decision Support Integration | Symptom management | Improved guideline-concordant care and supportive care referrals | [27] |

The integration of EHRs and patient-generated data within multimodal cancer research frameworks requires addressing significant challenges in data standardization, processing, and interpretation. However, as the methodologies and protocols outlined herein demonstrate, overcoming these barriers enables more comprehensive cancer modeling, improved predictive accuracy, and ultimately enhanced personalized treatment strategies. The continued development of standardized frameworks, advanced computational methods, and interdisciplinary collaboration will further unlock the potential of clinical and real-world data in transforming cancer research and care.

Breast cancer diagnosis has traditionally relied on single-modality data, an approach that offers limited and one-sided information, making it difficult to capture the full complexity and diversity of the disease [30]. This limitation has driven a paradigm shift toward multi-modal data fusion, which integrates complementary information streams to generate richer, more diverse datasets, ultimately leading to greater robustness in predictive outcomes compared to single-modal approaches [30] [31]. The clinical need is particularly acute in monitoring responses to Neoadjuvant Therapy (NAT), where accurately assessing pathological complete response (pCR) is critical for patient survival but challenging to accomplish with single-source data [20]. By synthesizing information from radiological, histopathological, clinical, and personal data modalities, multi-modal fusion creates a more holistic view of the tumor microenvironment and its response to treatment, directly addressing the critical diagnostic limitations inherent in single-modality frameworks.

Quantitative Evidence of Multi-modal Superiority

Research over the past five years consistently demonstrates that multi-modal fusion models significantly outperform single-modality approaches across key diagnostic tasks in breast cancer, including diagnosis, assessment of neoadjuvant systemic therapy, prognosis prediction, and tumor segmentation [30] [31]. The following tables summarize key performance metrics from recent landmark studies.

Table 1: Performance of Multi-modal Models in Predicting Pathological Complete Response (pCR)

| Model / System | Data Modalities | AUROC | Key Comparative Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| MRP System (Pre-NAT phase) [20] | Mammogram, MRI, Histopathological, Clinical, Personal | 0.883 (95% CI: 0.821-0.941) | ΔAUROC of 10.4% vs. uni-modal model (p=0.003) |

| MRP System (Mid-NAT phase) [20] | Mammogram, MRI, Histopathological, Clinical, Personal | 0.889 (95% CI: 0.827-0.948) | ΔAUROC of 11% vs. uni-modal model (p=0.009) |

| HXM-Net (Diagnosis) [5] | B-mode, Doppler, Elastography Ultrasound | 0.97 | Outperformed conventional ResNet-50 and U-Net models |

Table 2: Diagnostic Accuracy of the HXM-Net Multi-modal Ultrasound Model [5]

| Metric | Performance (%) |

|---|---|

| Accuracy | 94.20% |

| Sensitivity (Recall) | 92.80% |

| Specificity | 95.70% |

| F1 Score | 91.00% |

Core Multi-modal Fusion Strategies

The success of multi-modal diagnostics hinges on the strategy used to integrate heterogeneous data. Current deep learning-based approaches can be categorized into three primary fusion techniques [30] [31]:

- Feature-Level Fusion: This strategy involves extracting features from each modality independently using dedicated neural networks (e.g., CNNs for images) and then concatenating or combining these features into a unified representation before the final classification or regression layer. This allows the model to learn complex, cross-modal interactions at an early stage.

- Decision-Level Fusion: In this approach, each modality is processed through a separate model to produce an independent prediction or decision. These individual decisions are subsequently aggregated, often via weighted averaging or voting, to form a final, consolidated output.

- Hybrid Fusion: Hybrid methods combine aspects of both feature-level and decision-level fusion to create more flexible and robust network architectures. For instance, the MRP system uses a form of hybrid fusion by independently training separate models for mammogram and MRI data and then combining their predicted probabilities [20].

The logical workflow for implementing a multi-modal fusion system, from data acquisition to clinical application, is outlined below.

Multi-modal Fusion Clinical Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Multi-modal Response Prediction

This protocol details the methodology for the Multi-modal Response Prediction (MRP) system, which predicts pathological complete response (pCR) in breast cancer patients undergoing Neoadjuvant Therapy (NAT) [20].

Data Acquisition and Curation

- Cohort Selection: Identify breast cancer patients treated with NAT. The MRP study included 3,352 eligible participants from the Netherlands Cancer Institute (2004-2020). External validation cohorts are crucial (e.g., 288 patients from Duke University, 85 from Fujian Provincial Hospital, 508 from the I-SPY2 trial) [20].

- Data Modalities:

- Imaging: Collect Pre-NAT mammograms and longitudinal MRI exams (e.g., subtracted contrast-enhanced T1-weighted imaging from pre-, mid-, and post-NAT time points) [20].

- Radiological Findings: Annotate images with standard radiological assessments.

- Histopathological Data: Collect molecular subtype, tumor histology, type, and differentiation grade.

- Personal & Clinical Data: Include patient age, weight, menopausal status, genetic mutations, and clinical TNM staging [20].

- Data Partitioning: Randomly split the internal cohort into training (80%) and testing sets. Hold out the external cohorts for final validation.

Model Architecture and Training

The MRP system comprises two independently trained models: iMGrhpc (for mammography) and iMRrhpc (for longitudinal MRI). Both integrate the rhpc non-image data [20].

- Feature Extraction:

- For images (mammogram, MRI), use a pre-trained Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) backbone to extract high-level visual features.

- For non-image data (

rhpc), process using fully connected layers to create a feature vector.

- Cross-modal Knowledge Mining: Implement a strategy to enhance visual feature learning. This allows the model to focus on imaging features that are most informative given the context of the other data modalities [20].

- Temporal Information Embedding (for

iMRrhpc): Design the model to accept longitudinal MRI sequences. Embed temporal information to handle different NAT settings and time points (Pre-, Mid-, Post-NAT) flexibly [20]. - Handling Missing Modalities: Architect the system to be robust to missing data inputs (e.g., a patient missing a mammogram or a Mid-NAT MRI), a critical feature for real-world clinical applicability [20].

- Fusion and Output: Fuse the image and non-image features (feature-level fusion). The final MRP system combines the predicted probabilities from

iMGrhpcandiMRrhpc(decision-level fusion) to produce a single pCR probability [20].

Validation and Analysis

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate the model using Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve (AUROC), Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC), sensitivity, specificity, Positive Predictive Value (PPV), and Negative Predictive Value (NPV) [20].

- Benchmarking: Compare the model's performance against baseline models (e.g., uni-modal

rhpcmodel,iMGrhpcalone) and, if possible, against the performance of breast radiologists in a reader study [20]. - Clinical Utility Assessment: Use Decision Curve Analysis (DCA) to evaluate the net benefit of using the model for clinical decision-making in scenarios like enrolling patients in NAT trials or de-escalating surgery [20].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental and validation workflow for the MRP system.

MRP System Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials and Computational Tools for Multi-modal Diagnostics

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Public Breast Cancer Datasets | Provides multi-modal, annotated data for model training and benchmarking. | Includes imaging (mammography, MRI, ultrasound), histopathology, and clinical data. |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Backbone architecture for extracting spatial features from medical images. | Used in HXM-Net for ultrasound [5] and MRP for mammography/MRI [20]. |

| Transformer Architecture | Fuses multi-modal features using self-attention mechanisms to weight important regions. | Core component of HXM-Net's fusion module [5]. |

| Feature-wise Linear Modulation (FiLM) | Conditions the image processing pathway on non-image data (e.g., clinical text), enabling adaptive feature extraction. | Used in prompt-driven segmentation models for context-aware processing [32]. |

| Dice Loss Function | Optimizes model for single-organ or single-tumor segmentation tasks by maximizing region overlap. | Demonstrated as optimal for single-organ tasks [32]. |

| Jaccard (IoU) Loss Function | Optimizes model for complex, multi-organ segmentation tasks under cross-modality challenges. | Outperforms Dice loss in multi-organ scenarios [32]. |

The progression and treatment response of cancer are largely dictated by its heterogeneous nature, encompassing diverse cellular subpopulations with distinct genetic, transcriptional, and spatial characteristics. This complexity presents a significant challenge for accurate diagnosis and effective therapy. The emergence of multimodal data fusion—the computational integration of disparate data types—offers an unprecedented opportunity to capture a holistic view of this heterogeneity. By simultaneously analyzing genomic, transcriptomic, imaging, and clinical data, researchers can move beyond fragmented insights to develop a systems-level understanding of tumor biology, ultimately paving the way for more personalized and effective cancer interventions [33]. This article details specific protocols and applications that exemplify the power of integration in oncology research.

The field of multimodal oncology research is driven by a suite of advanced technologies, each contributing a unique piece to the puzzle of tumor heterogeneity. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of several prominent technologies and the computational methods used to integrate their data.

Table 1: Key Technologies and Integration Methods for Capturing Tumor Heterogeneity

| Technology / Method | Data Modality | Key Output | Spatial Resolution | Key Application in Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Transcriptomics (e.g., Visium) [1] | RNA | Genome-wide expression data with spatial context | 1-100 cells/spot | Tumor-immune microenvironment mapping |

| In Situ Sequencing (ISS) [34] | RNA | Targeted or untargeted RNA sequences within intact tissue | Single-cell | Subcellular RNA localization and splicing variants |

| Deep-STARmap [35] | RNA | Transcriptomic profiles of thousands of genes in 3D tissue blocks | Single-cell (in 60-200 µm thick tissues) | 3D cell typing and morphology tracing |

| Multi-contrast Laser Endoscopy (MLE) [36] | Optical Imaging | Multispectral reflectance, blood flow, and topography | ~1 Megapixel, HD video rate | In vivo enhancement of tissue chromophore and structural contrast |

| Tumoroscope [37] | Computational Fusion | Clonal proportions and their spatial distribution in ST spots | Near-single-cell | Deconvolution of clonal architecture from bulk DNA-seq and ST data |

| AZ-AI Multimodal Pipeline [13] | Computational Fusion | Integrated survival prediction model | N/A | Late fusion of multi-omics and clinical data for prognostic modeling |

| Feature-Based Image Registration [38] | Computational Fusion | Aligned multimodal images (e.g., H&E with mass spectrometry) | N/A | Correlation of tissue morphology with molecular/elemental distribution |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mapping Clonal Architecture with Tumoroscope

This protocol details the use of the Tumoroscope probabilistic model to spatially localize cancer clones by integrating histology, bulk DNA sequencing, and spatial transcriptomics data [37].

1. Primary Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- H&E Image Analysis: Process the H&E-stained tissue section using custom scripts in QuPath [39].

- Identify and demarcate regions containing cancer cells.

- Estimate the number of cells present within each Spatial Transcriptomics (ST) spot located in the cancerous regions.

- Bulk DNA-seq Analysis: Perform bulk whole exome sequencing on the tumor sample.

- Spatial Transcriptomics: Generate ST data from an adjacent tissue section.

- For each ST spot, obtain the count of alternative and total reads for the somatic mutations identified in the bulk DNA-seq.

- Obtain the gene expression matrix for all spots.

2. Core Tumoroscope Deconvolution Analysis

- Input Preparation: Format the preprocessed data for Tumoroscope input:

cell_count_prior: Vector of estimated cell counts per spot from H&E analysis.alternate_reads: Matrix of alternative read counts for each mutation in each spot.total_reads: Matrix of total read counts for each mutation in each spot.clone_genotypes: Scaled genotype matrix for the reconstructed clones.

- Model Execution: Run the Tumoroscope probabilistic graphical model. The model assumes each ST spot contains a mixture of clones and uses the input data to infer:

- The proportion of each clone in every spot.

- A refined estimate of the number of cells per spot.

- Output Analysis: The primary output is a spatial map of clone proportions across the tissue section, allowing for the visualization of clonal colocalization and mutual exclusion patterns.

3. Downstream Phenotypic Analysis

- Clone-Specific Gene Expression: Using the inferred clone proportions as the dependent variable and the spot-by-gene expression matrix as the independent variable, run a regression model to estimate the gene expression profile specific to each clone.

Protocol 2: 3D Spatial Transcriptomics in Thick Tissue Blocks with Deep-STARmap

This protocol describes the procedure for performing high-plex spatial transcriptomics within intact 3D tissue blocks using Deep-STARmap, enabling the correlation of molecular profiles with complex morphological structures [35].

1. Tissue Preparation, Embedding, and Clearing

- Tissue Fixation and Sectioning: Fix the fresh tissue sample (e.g., mouse brain or human skin cancer) and cut it into 60-200 µm thick sections using a vibratome.

- Hydrogel Embedding: Embed the tissue section in a hydrogel matrix. This step involves:

- Permeabilizing the tissue to allow entry of reagents.

- Anchoring RNA transcripts to the hydrogel network to preserve spatial information.

- Protein Digestion and Expansion: Digest cellular proteins with Proteinase K to clear the tissue and create a porous hydrogel-tissue hybrid. This is followed by mechanical expansion in water to physically separate biomolecules, reducing optical crowding and improving resolution.

2. In Situ Sequencing and Imaging

- Reverse Transcription and Amplification: Synthesize cDNA from RNA templates directly within the expanded hydrogel. Perform rolling circle amplification (RCA) to generate concentrated, copy-rich amplicons for each transcript.

- Sequencing by Ligation: Carry out in situ sequencing using Sequencing by Oligonucleotide Ligation and Detection (SOLiD) chemistry.

- Fluorescently labeled probes are sequentially ligated, imaged, and cleaved over multiple cycles to determine the base sequence of the amplicons.

- Multicycle Imaging: Automate cycles of probe hybridization, ligation, fluorescence imaging (using a confocal microscope), and dye cleavage to read out the nucleotide sequence for each transcript across multiple tissue sections.

3. 3D Reconstruction and Data Integration

- Image Registration and Reconstruction: Align the sequential imaging data from each thick section using computational image registration tools. Stack the aligned sections to reconstruct a 3D volume of the tissue block.

- If applicable, co-register with multicolor fluorescent protein images to correlate transcriptomic data with neuronal morphology or other structural markers.

- Data Analysis: Map the sequenced transcripts back to their 3D spatial coordinates. Perform downstream analyses such as:

- 3D molecular cell type clustering.

- Identification of spatially variable genes and expression gradients.

- Quantitative analysis of tumor-immune interactions within the 3D architecture.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Profiling Tumor Heterogeneity

| Item | Function/Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| QuPath Software [37] | Open-source digital pathology platform for whole-slide image analysis and cell detection. | Automated estimation of cancer cell counts in H&E images for Spatial Transcriptomics spots. |

| Canopy Software [37] | Computational tool for reconstructing clonal populations and their phylogenies from bulk DNA-seq data. | Inferring cancer clone genotypes and frequencies as input for the Tumoroscope model. |

| Aminoallyl dUTP [34] | A modified nucleotide containing a reactive amine group, used in cDNA synthesis. | Cross-linking cDNA to the protein matrix during FISSEQ to prevent diffusion and maintain spatial fidelity. |

| Proteinase K [35] [34] | A broad-spectrum serine protease that digests proteins. | Clearing proteins in Expansion Microscopy and hydrogel-embedded tissues to enable probe access and physical expansion. |

| SOLiD (Sequencing by Oligonucleotide Ligation and Detection) Chemistry [34] | A next-generation sequencing technology based on sequential ligation of fluorescent probes. | Reading out nucleotide sequences in high-plex in situ sequencing methods like FISSEQ. |

| Custom Fiber Optic Light Guide [36] | A modified light guide for a clinical colonoscope that integrates laser illumination bundles. | Enabling multimodal imaging (MLE) during standard-of-care white light endoscopy procedures. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Critical advancements in capturing tumor heterogeneity rely on a core set of reagents, software, and engineered materials that enable precise spatial and molecular analysis.

The integration of multimodal data is transforming our ability to dissect the complex and heterogeneous nature of tumors. The protocols outlined herein—from computational clonal deconvolution with Tumoroscope to 3D spatial transcriptomics with Deep-STARmap—provide a tangible roadmap for researchers to implement these powerful approaches. As these technologies continue to mature and become more accessible, they hold the definitive promise to uncover novel biological insights, identify new therapeutic targets, and ultimately advance the field towards a more precise and effective paradigm of oncology care.

Fusion Techniques and Clinical Deployment: From Architectures to Real-World Impact

Modern oncology research leverages diverse data modalities, including clinical records, multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics), medical imaging (histopathology, MRI, CT, ultrasound), and wearable sensor data [1]. Each modality provides unique insights into cancer biology, but their integration presents significant challenges due to data heterogeneity, varying structures, and scale differences [1]. Multimodal artificial intelligence (MMAI) approaches aim to integrate these heterogeneous datasets into cohesive analytical frameworks to achieve more accurate and personalized cancer care [3]. The fusion strategy—how these different data types are combined—critically impacts model performance, interpretability, and clinical applicability [31] [41].

Data fusion methods are broadly classified into four categories: early (data-level), late (decision-level), intermediate (feature-level), and hybrid fusion [31] [42]. Early fusion integrates raw data before model input, while late fusion combines outputs from modality-specific models. Intermediate fusion merges feature representations extracted from each modality, and hybrid approaches combine elements of the other strategies [31]. Selecting an appropriate fusion strategy requires balancing factors such as data heterogeneity, computational resources, model interpretability, and the specific clinical task [41] [13]. The following sections provide a detailed taxonomy of these fusion strategies, their applications in oncology, and practical protocols for implementation.

Theoretical Framework: Fusion Taxonomies

Table 1: Taxonomy of Multimodal Fusion Strategies in Oncology

| Fusion Type | Integration Level | Key Characteristics | Advantages | Limitations | Representative Applications in Oncology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Fusion | Data/Input Level | Raw data concatenated before model input; single model processes combined input [31] [42] | Simplicity of implementation; captures cross-modal correlations at raw data level [43] | Susceptible to overfitting with high-dimensional data; requires data harmonization [41] [13] | PET-CT volume fusion for segmentation [43] |

| Intermediate Fusion | Feature Level | Modality-specific features extracted then merged; shared model processes combined features [31] [43] | Balances specificity and integration; preserves modality-specific patterns [43] | Requires feature alignment; complex architecture design [43] | Anatomy-guided PET-CT fusion [43]; Multi-stage feature fusion networks [44] |

| Late Fusion | Decision/Output Level | Separate models per modality; predictions combined at decision level [31] [41] | Handles data heterogeneity; resistant to overfitting; modular implementation [41] [13] | Cannot model cross-modal correlations in early stages [43] | Survival prediction in breast cancer [41] [13]; Multi-omics integration [13] |

| Hybrid Fusion | Multiple Levels | Combines elements of early, intermediate, and/or late fusion [31] | Maximizes complementary information; highly flexible architecture [31] [5] | High computational complexity; challenging to optimize [31] | HXM-Net for ultrasound fusion [5]; PADBSRNet for multi-cancer detection [44] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Fusion Strategies in Oncology Applications

| Application Domain | Best Performing Fusion Strategy | Reported Performance Metrics | Modalities Combined | Reference Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer Survival Prediction | Late Fusion | Highest test-set concordance indices (C-indices) across modality combinations [41] | Clinical, somatic mutations, RNA expression, CNV, miRNA, histopathology images | TCGA Breast Cancer [41] |

| PET-CT Tumor Segmentation | Intermediate Fusion | Dice score: 0.8184; HD^95: 2.31 [43] | PET and CT volumes | Head and Neck Cancer PET-CT [43] |

| Breast Cancer Diagnosis | Hybrid Fusion (HXM-Net) | Accuracy: 94.20%; Sensitivity: 92.80%; Specificity: 95.70%; AUC-ROC: 0.97 [5] | B-mode ultrasound, Doppler, elastography | Breast Ultrasound Database [5] |

| Multi-Cancer Detection | Hybrid Fusion (PADBSRNet) | Accuracy: 95.24% (brain tumors), 99.55% (lung cancer), 88.61% (skin cancer) [44] | Multi-scale imaging features | Figshare Brain Tumor, IQ-OTH/NCCD, Skin Cancer Datasets [44] |

Early Fusion (Data-Level Fusion)