Molecular Dynamics in Cancer Treatment: A Guide to Simulation, Applications, and Clinical Translation

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a transformative tool in cancer research and drug discovery, providing atomic-level insights that are difficult to obtain through experimental methods alone.

Molecular Dynamics in Cancer Treatment: A Guide to Simulation, Applications, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as a transformative tool in cancer research and drug discovery, providing atomic-level insights that are difficult to obtain through experimental methods alone. This article offers a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of MD, its specific applications in optimizing cancer drug delivery and understanding drug-target interactions, current methodological challenges and solutions, and the critical integration with experimental data for validation. By exploring recent advancements and real-world case studies, we demonstrate how MD simulations are accelerating the development of more targeted and efficient cancer therapies.

The Atomic Lens: How Molecular Dynamics Reveals Cancer's Hidden Mechanisms

The paradigm of molecular interaction has evolved significantly from the simplistic, static lock-and-key model to a dynamic understanding of continuously moving structures. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have been pivotal in this shift, providing atomic-level insights into the behavior of biomolecules over time. In cancer treatment research, this computational approach has revolutionized drug discovery and development by offering a detailed view of protein behavior, drug-target interactions, and resistance mechanisms. This whitepaper explores the fundamental principles of MD simulations, their integration with other technologies in the drug development pipeline, and their specific applications in creating more effective, targeted cancer therapies. By addressing current challenges and emerging opportunities, we underscore the potential of molecular simulations in driving personalized oncology treatments.

Traditional drug discovery often relied on the lock-and-key model, which portrays molecular interactions as rigid and static. This perspective, while useful for initial conceptualization, fails to capture the true dynamic nature of biological systems, where proteins and other molecules are in constant motion, "jiggling and wiggling" as they interact with their environment. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations address this limitation by providing a computational framework to study the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. By applying Newtonian physics to biological systems, MD simulations allow researchers to observe molecular processes at an atomic level of detail, revealing the dynamic behavior that is crucial for understanding complex diseases like cancer [1].

In oncology, this dynamic view is particularly critical. Cancer is characterized by complex molecular mechanisms involving genetic mutations, dysregulated signaling pathways, and interactions with the tumor microenvironment. MD simulations help unravel this complexity by providing insights into the conformational changes of cancer-related proteins, the mechanisms of drug binding, and the emergence of therapeutic resistance [2]. As part of a broader thesis on molecular dynamics in cancer treatment simulation research, this whitepaper examines how MD simulations have transformed our understanding of cancer biology and drug development, moving beyond static pictures to capture the dynamic reality of molecular interactions.

Fundamental Principles of Molecular Dynamics

Theoretical Foundations and Computational Framework

Molecular dynamics simulations are rooted in statistical mechanics and molecular mechanics, employing force fields to approximate the potential energy of a molecular system. These force fields calculate energy based on bond stretching, angle bending, torsion angles, and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals forces and electrostatics). The simulation process involves solving Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in the system, typically using numerical integration methods like the Verlet or Leap-frog algorithms [3].

The fundamental equation governing MD simulations is Newton's second law: F = ma, where F is the force exerted on each particle, m is its mass, and a is its acceleration. Forces are derived from the negative gradient of the potential energy function specified by the force field. By iteratively calculating these forces and updating atomic positions and velocities, MD simulations generate a trajectory that describes how the positions and velocities of particles in the system change over time, typically on timescales of nanoseconds to microseconds [1].

Key Technical Considerations

Several technical aspects are crucial for conducting accurate and meaningful MD simulations:

- Force Field Selection: The choice of force field (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS) significantly impacts simulation accuracy, as different parameter sets are optimized for specific classes of biomolecules [3].

- Solvation Models: Biological systems require appropriate solvation, either through explicit water molecules or implicit solvation models, to accurately represent the physiological environment [3].

- Periodic Boundary Conditions: These are employed to simulate a bulk solution environment while minimizing edge effects and computational cost [3].

- Temperature and Pressure Control: Thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) and barostats (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) maintain realistic physiological conditions throughout the simulation [3].

- Enhanced Sampling Techniques: Methods like umbrella sampling, metadynamics, or accelerated MD help overcome energy barriers and explore rare events within feasible simulation timescales [3].

Integration of MD in the Cancer Drug Development Pipeline

MD simulations do not operate in isolation but are part of an integrated technological ecosystem in modern cancer drug development. This multidisciplinary approach synergistically combines multiple computational and experimental methods to accelerate and refine the discovery process [4].

Table 1: Core Technologies in Modern Cancer Drug Development

| Technology | Primary Function | Key Advantages | Current Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Omics Technologies | High-throughput molecular profiling (genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) | Provides foundational data support for drug research; reveals disease-related molecular characteristics | Data heterogeneity and lack of standardization can lead to biased predictions [4] |

| Bioinformatics | Computer-based processing and analysis of biological data | Aids in identification of drug targets and elucidation of mechanisms of action | Prediction accuracy depends on chosen algorithms, affecting reliability [4] |

| Network Pharmacology | Studies drug-target-disease networks using systems biology | Reveals potential for multi-targeted therapies; addresses disease complexity | May overlook biological complexity aspects like protein expression variations [4] [5] |

| Molecular Docking | Predicts preferred orientation of small molecules when bound to target | Rapid screening of compound libraries; initial assessment of binding affinity | Static snapshot may not capture dynamic binding process and induced fit [2] |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Examines drug-target interactions by tracking atomic movements | Provides dynamic view of interactions; assesses binding stability and conformational changes | High computational costs; sensitivity to force field parameters [3] [4] |

The typical drug development workflow leveraging these technologies begins with omics and database integration to identify potential targets. Network pharmacology approaches then help construct protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks, followed by pathway and gene ontology enrichment analysis. Molecular docking and virtual screening techniques enable initial drug design and screening, with MD simulations providing critical validation of binding stability and dynamics. Finally, experimental validation through in vitro and in vivo studies confirms computational predictions before regulatory submission [4].

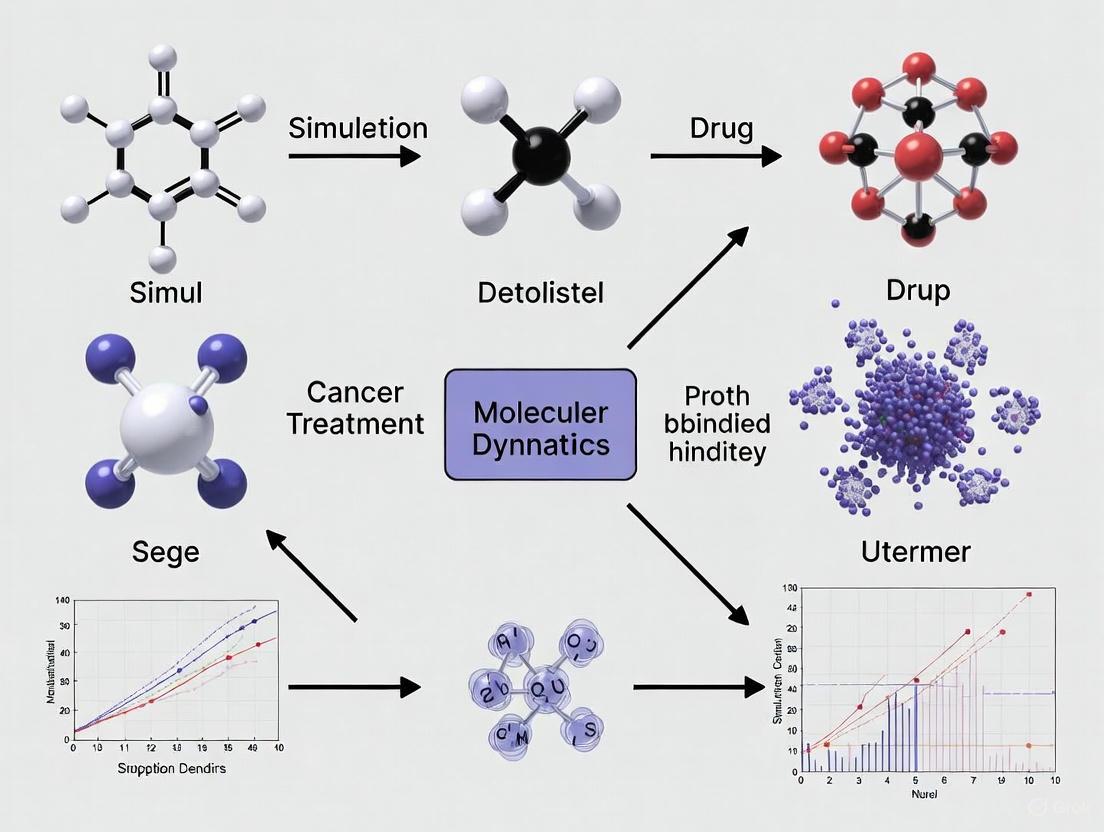

Figure 1: Integrated Drug Development Workflow. The process begins with omics data generation and bioinformatics analysis (green), proceeds through network pharmacology (yellow) and docking/MD simulations (red), and culminates in experimental validation (blue).

MD Simulations in Cancer Drug Delivery Systems

Optimizing Nanocarriers for Targeted Delivery

MD simulations have emerged as a vital tool in optimizing drug delivery systems for cancer therapy, offering detailed atomic-level insights into interactions between therapeutic compounds and their carriers. These simulations enable researchers to study drug encapsulation, carrier stability, and controlled release mechanisms with efficiency and precision that complement traditional experimental methods [3]. By modeling these processes at the molecular level, MD helps design more effective delivery vehicles that can overcome biological barriers and maximize therapeutic concentration at tumor sites.

Recent research has demonstrated the broad applicability of MD simulations in assessing various nanocarrier systems, including functionalized carbon nanotubes (FCNTs), chitosan-based nanoparticles, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and human serum albumin (HSA) carriers [3]. Each system offers distinct advantages: FCNTs provide high drug-loading capacity and stability, while biocompatible carriers like HSA and chitosan are favored for their biodegradability and reduced toxicity profiles. MD simulations help researchers understand the molecular mechanisms governing drug-carrier interactions, enabling rational design of next-generation delivery systems [3] [6].

Case Studies: Anticancer Drug Delivery

Several case studies involving common anticancer drugs illustrate how MD simulations improve drug formulation and delivery:

- Doxorubicin (DOX): Simulations have analyzed DOX interactions with single-walled carbon nanotubes, providing insights into loading efficiency and release kinetics [3].

- Gemcitabine (GEM): MD studies have explored GEM encapsulation in various nanocarriers, optimizing formulations for improved stability and controlled release [3].

- Paclitaxel (PTX): Coarse-grained MD simulations of PTX-loaded polymeric micelles have guided the design of systems with enhanced solubility and tumor-targeting capabilities [3].

These applications demonstrate how MD simulations contribute to developing more effective cancer treatments by addressing pharmaceutical challenges like poor solubility, limited stability, and suboptimal release profiles. The computational insights gained from MD studies help reduce the trial-and-error approach traditionally associated with formulation development, accelerating the creation of optimized drug delivery systems [3] [6].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard MD Protocol for Drug-Target Interactions

A comprehensive MD simulation protocol for studying drug-target interactions typically involves the following key steps:

System Preparation:

- Obtain 3D structures of the target protein from protein data banks or through homology modeling.

- Prepare ligand structures using chemical drawing software and optimize geometry using quantum mechanics methods.

- Parameterize the ligand for the chosen force field using tools like CGenFF or ACPYPE [3].

Simulation Setup:

- Place the protein-ligand complex in a simulation box with appropriate dimensions (typically 1.0-1.5 nm padding from the complex).

- Solvate the system with explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P water model).

- Add ions to neutralize the system and achieve physiological salt concentration (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl) [3].

Energy Minimization:

- Perform steepest descent minimization followed by conjugate gradient method until convergence (maximum force < 1000 kJ/mol/nm).

- This step removes steric clashes and unfavorable interactions in the initial structure [3].

Equilibration:

- Conduct equilibration in two phases: (1) NVT ensemble (constant number of particles, volume, and temperature) for 100-500 ps to stabilize temperature; (2) NPT ensemble (constant number of particles, pressure, and temperature) for 100-500 ps to stabilize density [3].

- Apply position restraints on protein heavy atoms during equilibration to allow solvent and ions to relax around the protein.

Production Run:

- Run unrestrained simulation for timescales appropriate to the biological process (typically 100 ns to 1 μs).

- Save atomic coordinates at regular intervals (every 10-100 ps) for subsequent analysis [5].

Trajectory Analysis:

- Calculate root mean square deviation (RMSD) to assess system stability.

- Compute root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) to identify flexible regions.

- Determine radius of gyration to measure compactness of the protein structure.

- Analyze hydrogen bonds and interaction energies between ligand and protein [5].

- Perform molecular mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann surface area (MM/PBSA) or molecular mechanics/generalized Born surface area (MM/GBSA) calculations to estimate binding free energies [5].

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

For processes involving high energy barriers or rare events, enhanced sampling methods improve conformational sampling:

- Umbrella Sampling: Applies bias potentials along a predefined reaction coordinate to facilitate exploration of high-energy states [3].

- Metadynamics: Uses history-dependent bias potentials to discourage the system from revisiting already sampled configurations [3].

- Accelerated MD: Modifies the potential energy surface to reduce energy barriers and enhance conformational sampling [3].

These techniques enable researchers to study biologically relevant events that occur on timescales longer than what is practically accessible through conventional MD simulations.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MD Simulations in Cancer Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, OpenMM | MD simulation engines that perform the numerical integration of equations of motion and manage force calculations [3] |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS | Parameter sets defining potential energy functions, including bond lengths, angles, dihedrals, and non-bonded interactions [3] |

| System Preparation Tools | PACKMOL, CHARMM-GUI, tleap | Utilities for building simulation systems, including solvation, ionization, and membrane embedding [3] |

| Visualization & Analysis | VMD, PyMOL, MDAnalysis, CPPTRAJ | Tools for visualizing trajectories and analyzing structural properties, interactions, and dynamics [3] [5] |

| Enhanced Sampling | PLUMED, COLVARS | Libraries implementing various enhanced sampling algorithms for studying rare events [3] |

| Binding Affinity Calculations | MM/PBSA, MM/GBSA | Methods for estimating binding free energies from MD trajectories [5] |

| Target Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB), Swiss Target Prediction | Repositories of 3D protein structures and target prediction tools for initial system setup [5] |

| Compound Libraries | PubChem, ZINC, ChEBI | Databases of small molecules for virtual screening and drug discovery [4] |

MD Applications in Cancer Signaling Pathways

MD simulations provide critical insights into cancer-related signaling pathways by elucidating the dynamic behavior of pathway components at atomic resolution. These simulations help researchers understand how mutations affect protein conformation, how post-translational modifications influence interactions, and how therapeutic compounds modulate pathway activity [1].

A prominent application involves studying the conformational dynamics of kinases in cancer pathways. For example, MD simulations have revealed how mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) kinase domain affect its transition between active and inactive states, influencing sensitivity to targeted inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer [2]. Similarly, simulations of BRAF mutations in melanoma have provided mechanistic insights into how specific amino acid changes lead to constitutive kinase activation and uncontrolled cell proliferation [1].

Figure 2: Cancer Signaling Pathway Modulation. MD simulations help understand how therapeutic inhibitors (blue) interfere with oncogenic signaling cascades, from ligand-receptor binding (green) through intracellular signaling (yellow) to pathological cellular responses (red).

In liver cancer research, integrated approaches combining network pharmacology with MD simulations have identified promising natural compounds targeting key proteins like heat shock protein 90 (HSP90AA1). Molecular dynamics simulation analysis predicted complexes with highly stable dynamics, showing that protein residues maintained a highly stable nature except for the N-terminal domain without affecting drug binding [5]. This application demonstrates how MD simulations validate and refine predictions from other computational approaches, building confidence in proposed therapeutic mechanisms before resource-intensive experimental validation.

Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Despite significant advances, MD simulations in cancer research face several challenges that represent active areas of methodological development:

- Timescale Limitations: Many biologically relevant processes in cancer biology occur on timescales (milliseconds to seconds) that remain challenging for conventional MD simulations, though emerging specialized hardware and enhanced sampling methods are gradually addressing this limitation [3].

- Force Field Accuracy: The reliability of simulation results depends on the accuracy of force field parameters, particularly for non-standard residues, post-translational modifications, and novel chemical compounds [4].

- Computational Resource Requirements: Long timescale simulations of large biomolecular systems demand substantial computational resources, limiting accessibility for some research groups [3].

- Integration with Experimental Data: Developing robust methods to integrate simulation data with experimental observations from crystallography, NMR, and cryo-EM remains an important challenge [1].

Future developments in MD simulations for cancer research will likely focus on several key areas:

- Multiscale Modeling: Combining all-atom simulations with coarse-grained models to access larger systems and longer timescales while maintaining atomic-level detail where needed [3].

- Machine Learning Integration: Leveraging artificial intelligence to improve force field accuracy, analyze complex trajectory data, and predict molecular properties [3] [4].

- High-Performance Computing: Utilizing exascale computing resources and specialized hardware to dramatically extend simulation capabilities [3].

- Personalized Medicine Applications: Developing workflows that incorporate patient-specific genetic mutations into MD simulations to predict individual treatment responses and resistance mechanisms [2] [1].

These technological advances, combined with closer integration between computational and experimental approaches, will further establish MD simulations as an indispensable tool in cancer drug discovery and development.

The evolution from static structural models to dynamic simulations representing the constant "jiggling and wiggling" of biomolecules has transformed cancer drug discovery. Molecular dynamics simulations provide unprecedented insights into the atomic-level mechanisms underlying cancer progression, drug resistance, and therapeutic interventions. When integrated with omics technologies, bioinformatics, and network pharmacology, MD forms part of a powerful multidisciplinary approach that accelerates the development of more effective and targeted cancer therapies.

As computational power continues to grow and methodologies refine, MD simulations will play an increasingly central role in personalized oncology, enabling researchers to model patient-specific mutations and predict individual treatment responses. The ongoing collaboration between computational scientists, structural biologists, and clinical researchers will be essential to translate these dynamic molecular insights into improved cancer treatments that benefit patients. The journey beyond the static picture has just begun, but already offers a much richer and more realistic view of the molecular processes that drive cancer and its treatment.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as a powerful computational microscope, providing atomic-level insights that are indispensable in modern cancer treatment research. By enabling scientists to visualize the dynamic interactions between drugs and their biological targets, MD simulations help optimize drug design, understand resistance mechanisms, and develop more effective therapeutic strategies [6]. This technical guide details the core components of MD simulations, framed within the context of their application in oncology research.

Force Fields: The Governing Laws of the Molecular Universe

The force field is the foundational component of any MD simulation, defining the potential energy of a system as a function of the nuclear coordinates. It effectively encapsulates the laws of physics that govern atomic interactions.

Mathematical Formulation

A typical classical force field decomposes the total potential energy into bonded and non-bonded terms [7]:

- Bonded Interactions: Describe the energies associated with covalent bonds.

- Non-bonded Interactions: Describe longer-range forces between atoms, including van der Waals forces and electrostatic interactions.

The accurate description of metal ions, which are critical in many cancer-related proteins, remains a particular challenge. Specialized non-bonded or bonded parameters must be developed, often based on Quantum Mechanics calculations, to correctly model their coordination geometry [8].

Force Field Selection for Biomedical Applications

The choice of force field is critical and depends on the biological system under investigation. The table below summarizes common force fields and their typical uses in cancer research.

Table 1: Common Force Fields in Biomolecular Simulation

| Force Field | Common Applications | Key Features | Example in Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER ff14SB [9] | Protein and DNA simulations | Optimized for protein backbone and side-chain conformations | Studying the Androgen Receptor for triple-negative breast cancer [9]. |

| CHARMM36 [10] | Proteins, lipids, nucleic acids | Accurate for a wide range of biomolecules | Simulation of SARS-CoV-2 proteins for drug repurposing studies [10]. |

| OPLS4 [11] | Drug discovery and protein-ligand binding | Optimized for small molecules and protein-ligand complexes | Virtual screening for novel HER-2+ breast cancer therapeutics [11]. |

Solvation Models: Creating a Realistic Biological Environment

To mimic the native state of biomolecules, simulations must be conducted in a realistic aqueous environment. Solvation models are designed to represent the effect of water and ions on the structure and dynamics of the solute.

Explicit Solvent Models

Explicit solvent models, such as the TIP3P (Transferable Intermolecular Potential with 3 Points) model [10], represent water molecules as individual entities with specific atomic coordinates and interactions. This approach is highly accurate as it naturally captures effects like specific hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic effects, and solvent structure. Its main disadvantage is the high computational cost, as the number of water molecules can dwarf the number of atoms in the protein or drug molecule of interest.

Implicit Solvent Models

Implicit solvent models (e.g., Generalized Born Surface Area, GBSA) treat the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium rather than individual molecules. This significantly reduces the number of particles in the system and accelerates calculations. Methods like Molecular Mechanics with Generalised Born Surface Area (MM-GBSA) are frequently used in cancer drug discovery to estimate binding free energies between lead compounds and their protein targets, providing a crucial metric for prioritizing candidates for further experimental testing [9] [10].

Table 2: Comparison of Solvation Methods in MD Simulations

| Solvation Method | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit Solvent (e.g., TIP3P) | Each water molecule is modeled as an individual entity. | High accuracy; captures specific solvent effects. | Computationally expensive; limits simulation timescale. |

| Implicit Solvent (e.g., GB/SA) | Solvent is treated as a continuous dielectric medium. | Much faster computation; efficient for binding energy calculations. | Less accurate; misses specific water-mediated interactions. |

Boundary Conditions and System Setup

Boundary conditions are essential for simulating a finite piece of a much larger, effectively infinite system (like a protein in a vast solution) without introducing artificial surface effects.

Periodic Boundary Conditions

Periodic Boundary Conditions are the standard approach. The central simulation box, containing the solute and solvent, is treated as a repeating unit cell that tiles space in all directions. When a particle exits the box through one face, it simultaneously re-enters through the opposite face, conserving the number of particles. This effectively eliminates surfaces and models a bulk environment [12]. Long-range electrostatic interactions under PBC are typically handled using the Particle Mesh Ewald method [10].

System Initialization and Equilibration

Before production simulation, the system must be carefully prepared and equilibrated [7]:

- Energy Minimization: Removes any bad contacts or steric clashes in the initial structure.

- Solvation and Ion Addition: The solute is placed in a box of water molecules, and ions are added to neutralize the system's charge and achieve a physiologically relevant salt concentration.

- Equilibration: The system is gradually heated to the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) and the pressure is stabilized to 1 bar through short simulations in the NVT (constant Number, Volume, Temperature) and NPT (constant Number, Pressure, Temperature) ensembles. This ensures the system is stable and has the correct density before data collection begins.

An Integrated Workflow for Cancer Drug Discovery

The components of force fields, solvation, and boundary conditions come together in a standard MD workflow. This process is widely applied in cancer research, from identifying potential drugs to designing nanocarriers for drug delivery.

Application Example: Identifying a Novel Breast Cancer Therapeutic

A recent study on HER-2+ breast cancer exemplifies this workflow [11]. Researchers began by preparing the crystal structure of the HER-2 kinase domain. They used the OPLS4 force field for the protein and ligands, solvated the system in an explicit water box with periodic boundary conditions, and added ions. After minimization and equilibration, production MD simulations were run to evaluate the stability and interactions of potential drug candidates. This computational pipeline identified a promising compound (Compound_56) with high binding affinity and stability, showcasing how MD simulations can accelerate the discovery of novel cancer therapeutics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MD Simulations

| Tool Category | Example Software/Database | Function | Relevance to Cancer Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation Engines | GROMACS [10], NAMD, AMBER | Core software to run MD simulations; calculates forces and integrates equations of motion. | Simulating protein-drug complexes (e.g., androgen or HER-2 receptors) [9] [11]. |

| Force Field Databases | CGenFF [10], AMBER Parameter Database | Provide parameters for small molecules and biomolecules to ensure accurate force field assignment. | Modeling anti-cancer drugs like Capmatinib within a protein target [10]. |

| System Building Tools | CHARMM-GUI, PACKMOL | Automate the process of solvation, ion addition, and box creation for complex systems. | Preparing self-assembled nanomedicine systems for simulation [12]. |

| Analysis Suites | MDAnalysis, VMD, PyMOL | Analyze simulation trajectories to compute properties like RMSD, RMSF, and interaction energies. | Validating the stability of a phytochemical bound to a cancer target [9]. |

| Specialized Platforms | Matlantis, Desmond | Offer integrated, high-performance or AI-accelerated environments for running MD simulations. | High-throughput screening of drug candidates [7]. |

| MS645 | MS645, MF:C48H54Cl2N10O2S2, MW:938.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| 7-BIA | 7-BIA, MF:C15H18O6, MW:294.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

The rigorous application of MD simulations, built upon the core components of accurate force fields, realistic solvation models, and proper boundary conditions, is transforming cancer treatment research. As computational power increases and methods are refined with machine learning, MD will play an even greater role in bridging the gap between atomic-level interactions and clinical outcomes, ultimately paving the way for more personalized and effective cancer therapies.

Visualizing Protein Flexibility and Allosteric Sites in Cancer Targets

The dynamic nature of proteins is fundamental to their function in health and disease. In cancer biology, understanding protein flexibility and allosteric regulation has emerged as a transformative approach for therapeutic intervention. Protein flexibility refers to the intrinsic capacity of proteins to sample alternative conformations, while allosteric sites are regulatory regions distinct from the active site where ligand binding can modulate protein function at a distant location [13]. The integration of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with advanced machine learning techniques now enables researchers to visualize and quantify these dynamic processes with unprecedented atomic-level detail, creating new opportunities for targeting historically undruggable cancer pathways [1] [14].

This technical guide examines the core principles and methodologies for studying protein flexibility and allosterism in cancer targets, providing researchers with practical frameworks for applying these approaches in drug discovery. We focus specifically on the computational and experimental strategies that bridge the gap between theoretical understanding and therapeutic application, with emphasis on methodologies that have yielded validated experimental outcomes.

Protein Flexibility in Cancer Mechanisms

Quantitative Flexibility Metrics from MD Simulations

Protein flexibility can be quantified through several computational metrics derived from MD simulations, each providing unique insights into dynamic behavior relevant to oncogenic processes:

B-factor Analysis: Also known as temperature factors, B-factors derived from crystallographic data or MD simulations quantify the mean squared displacement of atoms, serving as a primary metric for flexibility [15] [16]. Elevated B-factors often correspond to regions with high conformational entropy.

Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): RMSF calculations from MD trajectories measure the deviation of atomic positions from their average structure, identifying flexible regions that may facilitate allosteric communication or ligand binding [17].

Dynamic Cross-Correlation Maps (DCCM): These maps visualize correlated and anti-correlated motions between different protein regions, revealing networks of residues that move in concert—a hallmark of allosteric propagation [13].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA): PCA reduces the complexity of MD trajectories to essential dynamics, identifying the collective motions and conformational subspaces that define functional transitions [18].

Table 1: Key Flexibility Metrics and Their Computational Applications in Cancer Research

| Metric | Description | Cancer Research Application | Technical Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| B-factor | Atomic displacement from mean position | Identifying flexible regions in binding sites | Calculated from MD trajectories or crystallographic data |

| RMSF | Per-residue positional fluctuation during simulation | Mapping mutation effects on protein dynamics | GROMACS rmsf function on MD trajectories |

| DCCM | Correlated motion between residue pairs | Revealing allosteric communication networks | Bio3D, MDTraj, or custom scripts |

| PCA | Collective motions in conformational space | Characterizing functional states transitions | Covariance matrix diagonalization of MD coordinates |

Flexibility in Activating Cancer Mutations

Protein flexibility provides a crucial mechanism for understanding how mutations drive oncogenic activation. The MET receptor tyrosine kinase mutation Y501C exemplifies this principle, where molecular dynamics simulations demonstrated that this missense alteration increases flexibility in the protein's binding interface, enhancing hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) binding affinity and promoting constitutive signaling [19]. This flexibility-based activation mechanism explains the clinical response of a hepatocellular carcinoma patient with this mutation to the MET inhibitor cabozantinib, which resulted in a 65% decrease in alpha-foeto-protein levels [19].

In kinases, a common oncogenic mechanism involves mutations that shift the conformational equilibrium toward active states. For example, in Abl kinase, cancer-associated mutations increase flexibility in specific regulatory segments, favoring the active, drug-binding incompetent conformation and potentially allowing ATP to outcompete inhibitor binding [13]. Similarly, in the lipid kinase PI3Kα, driver mutations such as E542K, E545K, and H1047R relieve autoinhibition by enhancing flexibility in the interdomain interfaces, facilitating membrane attachment and catalytic activation [13].

Allosteric Sites as Therapeutic Targets

Identifying and Validating Allosteric Sites

Allosteric sites offer distinctive therapeutic advantages over orthosteric sites, including greater specificity and the ability to modulate rather than completely abolish protein function. Computational identification of allosteric sites typically employs integrated approaches:

MD-Based Pocket Detection: Long-timescale MD simulations (typically 400ns-1μs) can reveal transient pockets not visible in static crystal structures. In a study of human aromatase (HA), a key breast cancer target, MD simulations identified three potential allosteric pockets, with two—Site 1 (substrate access channel) and Site 2 (CPR binding site)—implicated in pivotal aspects of catalysis [18].

Allosteric Communication Networks: Residue interaction networks analyzed from MD trajectories can identify pathways for allosteric signal propagation. Mutations often cluster in "hot regions" where residues form cooperative interaction networks; disrupting these networks can modulate allosteric signaling [13].

Metadynamics Simulations: Enhanced sampling techniques like metadynamics can efficiently explore free energy landscapes and identify cryptic allosteric sites. In the TIPE2 virtual screening campaign, metadynamics simulations refined binding poses and estimated dissociation free energy barriers for candidate compounds [17].

Table 2: Experimental Validation Methods for Allosteric Modulators

| Validation Method | Experimental Readout | Information Gained | Case Study Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive BLI | Direct binding affinity measurement | Quantifies ligand binding and competition with native partners | TIPE2 inhibitor UM-164 showed 4.97 µM affinity in BLI assays [17] |

| Enzyme Kinetics | Michaelis-Menten parameters with varying inhibitor | Determines inhibition modality (non-competitive vs competitive) | Human aromatase allosteric inhibitors showed non-competitive kinetics [18] |

| Cellular Proliferation | Cell viability dose-response | Confirms functional activity in biological context | Ketanserin antagonized HTR2A to alleviate dioxin-associated liposarcoma toxicity [14] |

| Pathway Analysis | Downstream signaling phosphorylation | Maps effect on entire signaling network | Allosteric Abl inhibitors modulate conformational landscape [13] |

Allosteric Drug Discovery Case Studies

TIPE2 Inhibition in Cancer Immunotherapy

TIPE2 (tumor necrosis factor-alpha-induced protein 8-like 2) represents a compelling cancer immunotherapy target due to its role in polarizing myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). An integrated deep learning and MD screening approach identified UM-164 as a novel TIPE2 inhibitor with strong binding affinity (4.97 µM) [17]. The workflow exemplifies modern allosteric drug discovery:

Deep Learning Screening: A Dense Fully Connected Neural Network (DFCNN) using mol2vec representations performed preliminary screening of commercial compound libraries, predicting protein-ligand binding probability without dependency on binding conformation [17].

MD Refinement: Molecular dynamics simulations refined binding poses and assessed complex stability, filtering 64 candidates from thousands of initial compounds [17].

Experimental Validation: Bio-layer interferometry confirmed UM-164's ability to interfere with TIPE2-PIP2 binding, demonstrating the functional efficacy predicted computationally [17].

Allosteric Modulation of Human Aromatase

In breast cancer treatment, targeting human aromatase (HA) through allosteric inhibition offers potential advantages over conventional aromatase inhibitors by reducing side effects and possibly delaying resistance onset. An integrated computational-experimental protocol identified five non-competitive HA inhibitors with low μM activity [18]:

- Ensemble Docking: Virtual screening targeting two putative allosteric sites across multiple HA conformational states

- MD Refinement: Cumulative 10μs MD simulations to refine docking poses of selected compounds

- Metadynamics: Binding pose refinement and dissociation free energy estimation

- Kinetic Studies: Validation of non-competitive inhibition mechanism through enzyme kinetics

This approach established the feasibility of allosteric estrogen biosynthesis regulation, providing novel therapeutic strategies for ER+ breast cancer [18].

Integrated Methodologies

Combined Machine Learning and MD Workflows

The integration of machine learning with molecular dynamics simulations has created powerful workflows for mapping protein flexibility and allosteric sites:

Graph Neural Networks for Flexibility Prediction: Recent advances utilize graph neural networks (GNNs) operating at atomic-level representations to predict protein flexibility from 3D structures. The Meta-GNN model achieves a correlation coefficient of 0.71 on a diverse test set of over 4,000 proteins (17 million atoms), significantly outperforming previous residue-level methods [15]. These approaches learn complex patterns of atomic interactions that dictate flexibility profiles, enabling accurate B-factor prediction from static structures.

Deep Learning Flexibility Classifiers: Tools like MEDUSA employ convolutional neural networks that use evolutionary information from homologous sequences and physico-chemical properties to assign flexibility classes to each position in a protein sequence [16]. Trained on non-redundant datasets of X-ray structures, MEDUSA provides binary, three-class, and five-class flexibility predictions with state-of-the-art accuracy.

Network Toxicology Integration: In dioxin-associated liposarcoma research, machine learning (117 algorithm combinations) identified five key proteins (CDH3, ADORA2B, MMP14, IP6K2, and HTR2A) for predicting disease development, with MD simulations validating compound-target interactions [14]. This workflow connected environmental carcinogens with specific cancer mechanisms through protein flexibility and allosteric modulation analysis.

Diagram 1: Integrated ML-MD screening workflow. The fusion of molecular dynamics simulations and machine learning creates a powerful pipeline for allosteric drug discovery.

Experimental Protocols

MD Simulation Protocol for Allosteric Site Identification

This standardized protocol for allosteric site detection integrates established methodologies from multiple case studies [17] [18] [14]:

System Preparation

- Obtain protein structure from PDB or generate homology model using I-TASSER [17]

- Parameterize ligand structures using GAFF2 force field [14]

- Solvate system in TIP3P water model with minimum 1.0 nm padding

- Add ions to neutralize system charge and achieve physiological concentration (0.15M NaCl)

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

- Perform steepest descent energy minimization (maximum 50,000 steps) until maximum force < 1000 kJ/mol/nm [14]

- Equilibrate in NVT ensemble for 100 ps at 310 K using V-rescale thermostat (Ï„ = 0.1 ps) with position restraints on protein and ligand heavy atoms

- Equilibrate in NPT ensemble for 100 ps at 310 K and 1 bar using Parrinello-Rahman barostat (Ï„ = 2.0 ps)

Production MD

- Run unrestrained production simulation for 100-1000 ns (depending on system size and research question)

- Use 2 fs integration time step with LINCS constraints on all bonds involving hydrogen atoms

- Employ Particle Mesh Ewald for electrostatic interactions with 1.0 nm cutoff

- Save trajectories every 10-100 ps for subsequent analysis

Analysis Phase

- Calculate RMSD, RMSF, and radius of gyration to assess stability and flexibility

- Perform pocket detection using MDtraj or trj_cavity

- Construct dynamic cross-correlation maps to identify allosteric networks

- Use community analysis and residue interaction networks to identify allosteric hotspots

Deep Learning Screening Protocol

The DFCNN (Dense Fully Connected Neural Network) architecture employed for TIPE2 screening provides a template for deep learning-based virtual screening [17]:

Input Representation

- Generate molecular vectors for protein pockets and ligands using mol2vec

- Concatenate protein and ligand vectors to form input features

- Normalize features using training set mean and standard deviation

Model Application

- Load pre-trained DFCNN model weights (trained on PDBbind 2017 dataset)

- Perform forward pass on compound library

- Rank compounds by predicted binding probability

- Select top candidates (typically 0.1-1% of library) for MD refinement

Validation and Refinement

- Subject top-ranked compounds to molecular docking

- Perform short MD simulations (10-50 ns) to assess binding stability

- Select most promising candidates for experimental testing

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Protein Flexibility and Allosteric Site Analysis

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Software | GROMACS [14], AMBER [19], Desmond [20] | Atomic-level simulation of protein dynamics | GROMACS favored for large systems; AMBER for enhanced sampling |

| Analysis Tools | MDTraj, Bio3D, CPPTRAJ [19] | Trajectory analysis and metric calculation | MDTraj offers Python API for workflow integration |

| Deep Learning | DFCNN [17], MEDUSA [16], Meta-GNN [15] | Flexibility prediction and binding affinity estimation | Meta-GNN uses atomic-level graphs for B-factor prediction |

| Enhanced Sampling | Metadynamics [17] [18], Accelerated MD | Free energy landscape exploration | Metadynamics effective for binding pose refinement |

| Visualization | PyMOL [14], VMD [18] | Structural visualization and figure generation | VMD integrated with MD analysis workflows |

| Compound Databases | ZINC, ChEMBL [20], TargetMol [17] | Commercial and public compound libraries | TargetMol libraries used in TIPE2 screening |

| Experimental Validation | BLI [17], Enzyme Kinetics [18], Cell Viability [14] | Binding affinity and functional assessment | BLI measures direct binding without labels |

| G0507 | G0507|LolCDE Inhibitor | G0507 is a potent LolCDE ABC transporter inhibitor for Gram-negative bacteria research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. | Bench Chemicals |

| abc99 | abc99, MF:C22H21ClN4O5, MW:456.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Diagram 2: Allosteric regulation in cancer. Allosteric mechanisms can both drive oncogenic signaling and provide therapeutic opportunities for pathway modulation.

The integration of molecular dynamics simulations, machine learning, and experimental validation has transformed our ability to visualize and target protein flexibility and allosteric sites in cancer biology. These approaches have moved from theoretical exercises to practical drug discovery platforms, as demonstrated by successful identification of allosteric modulators for targets including TIPE2, human aromatase, and EGFR. As MD simulations continue to benefit from increasing computational resources and more accurate force fields, and as deep learning models incorporate more sophisticated architectural innovations, the precision and throughput of allosteric drug discovery will further accelerate. The methodologies outlined in this technical guide provide a framework for researchers to leverage these advances in developing novel cancer therapeutics that target the dynamic nature of oncogenic proteins.

Mapping Post-Translational Modifications (PTMs) and Their Role in Oncogenesis

Post-translational modifications (PTMs) are enzymatic or chemical covalent modifications that occur on specific amino acid residues after protein biosynthesis, fundamentally altering protein function by modulating structure, localization, stability, and interaction networks [21] [22]. The proteome's functional diversity expands dramatically through PTMs, with over 400 distinct types cataloged, ranging from small chemical additions like phosphorylation to complex attachments such as ubiquitin chains [22]. In oncogenesis, aberrant PTM patterns reprogram cellular physiology by dysregulating critical signaling pathways that govern proliferation, metabolism, apoptosis, and immune evasion [21] [23] [24]. The integration of PTM mapping with molecular dynamics simulations provides unprecedented mechanistic insights into protein conformational changes that drive malignant transformation, creating new avenues for therapeutic intervention in cancer treatment simulation research [6] [25].

Major PTM Classes in Oncogenesis: Mechanisms and Functional Consequences

Table 1: Key Post-Translational Modifications in Oncogenesis

| PTM Type | Residue Modified | Enzymes (Writers/Erasers) | Functional Consequences in Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphorylation | Serine, Threonine, Tyrosine | Kinases/Phosphatases | Activates/inactivates signaling proteins; aberrant in signal transduction [22] |

| Acetylation | Lysine | Acetyltransferases/Deacetylases | Regulates chromatin structure, metabolic enzymes, transcription factors [22] [23] |

| Ubiquitination | Lysine | E1-E3 Ligases/Deubiquitinases | Controls protein degradation, DNA repair, endocytosis [22] |

| Methylation | Lysine, Arginine | Methyltransferases/Demethylases | Modulates transcription factor activity, RNA processing [22] |

| Lactylation | Lysine | Lactyltransferases/Delactylases | Links metabolism to gene regulation; promotes tumor proliferation [21] [23] |

| SUMOylation | Lysine | SUMO E1-E3 Ligases/SENPs | Regulates transcription, genomic stability, protein-protein interactions [21] |

| Succinylation | Lysine | Succinyltransferases/Desuccinylases | Alters mitochondrial metabolism and metabolic reprogramming [21] [22] |

Phosphorylation

Kinase-mediated phosphorylation represents one of the most extensively studied PTMs in oncology, functioning as a molecular switch that controls protein activity through conformational changes or by creating binding interfaces for interacting domains [22]. Oncogenic pathogenesis frequently involves mutated kinases or phosphatases that disrupt the phosphorylation equilibrium, leading to constitutive activation of proliferative pathways such as RTK-RAS and PI3K-Akt [22] [26]. The pan-cancer analysis of 10 canonical signaling pathways revealed that phosphorylation-dependent pathways are altered in 89% of tumors, with 57% containing pharmacologically targetable alterations [26].

Acetylation and Lactylation

Lysine acetylation transfers acetyl groups from acetyl-CoA to ε-amino groups, modulating protein function through charge neutralization and structural alterations [22] [23]. The acetylome encompasses thousands of non-histone proteins involved in metabolism, RNA processing, and protein degradation [23]. Lactylation represents a recently discovered PTM that mechanistically links glycolytic flux to epigenetic reprogramming [23]. The Warburg effect in cancer cells generates substantial lactate that serves as substrate for lysine lactylation, creating a molecular bridge between metabolic reprogramming and gene expression [23]. AARS1 functions as a lactyltransferase that translocates to the nucleus under high lactate conditions, lactylating oncogenic regulators like YAP and p53 to promote proliferation and disrupt tumor suppression [23].

Ubiquitination and SUMOylation

Ubiquitination involves the covalent attachment of ubiquitin polypeptides to target proteins, typically marking them for proteasomal degradation but also regulating non-proteolytic functions like DNA repair and kinase activation [22]. SUMOylation parallels the ubiquitination pathway but utilizes small ubiquitin-like modifier proteins to modulate transcription factor activity, protein localization, and genomic stability [21]. The intricate balance between ubiquitination and SUMOylation forms a critical regulatory network that controls oncoprotein stability and tumor suppressor turnover [24].

Experimental Methodologies for PTM Mapping

Proteomic Profiling Workflows

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics represents the cornerstone technology for comprehensive PTM mapping [25]. High-resolution UPLC-MS/MS systems enable identification and quantification of modified peptides from complex biological samples, with specific enrichment techniques required to overcome the analytical challenge of low stoichiometry PTMs amidst abundant unmodified peptides [25].

Protocol 1: Phosphoproteome Analysis Using TiOâ‚‚ Enrichment

- Sample Preparation: Lyse tissues or cells in urea-containing buffer with phosphatase and protease inhibitors. Reduce disulfide bonds with dithiothreitol (5mM, 30min, 25°C) and alkylate with iodoacetamide (15mM, 20min, dark).

- Protein Digestion: Perform tryptic digestion at 1:50 enzyme-to-substrate ratio (37°C, 16h).

- Phosphopeptide Enrichment: Condition TiOâ‚‚ beads with 80% acetonitrile/5% TFA. Incubate peptide mixture with beads (1:4 ratio) in 80% acetonitrile/2% TFA with 100mg/mL lactic acid (30min, rotation).

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Wash beads sequentially with 80% acetonitrile/1% TFA and 20% acetonitrile/0.1% TFA. Elute phosphopeptides with 5% ammonium hydroxide. Analyze by nanoLC coupled to Orbitrap mass spectrometer operating in data-dependent acquisition mode.

Protocol 2: Immunoaffinity Purification of Acetylated Lysines

- Antibody Coupling: Covalently crosslink 10μg anti-acetyl-lysine antibody to 20μL Protein A/G beads using dimethyl pimelimidate.

- Enrichment: Incubate 1mg tryptic peptides with antibody-conjugated beads (2h, 4°C, rotation).

- Wash and Elution: Wash sequentially with IP buffer (50mM Tris pH8, 150mM NaCl), high-salt buffer (IP buffer + 500mM NaCl), and deionized water. Elute acetylated peptides with 0.1% TFA (2×10min).

- Mass Spectrometry: Desalt using C18 StageTips and analyze by LC-MS/MS with collision-induced dissociation for peptide fragmentation.

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Approaches

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide atomic-resolution insights into PTM-induced structural perturbations that underlie functional alterations in cancer proteins [6] [25].

Protocol 3: MD Simulation of PTM-Modified Proteins

- System Setup: Obtain protein structures from Protein Data Bank or homology modeling. Introduce PTMs using molecular modeling software (e.g., PyMOL, CHARMM-GUI). Parameterize modified residues using CHARMM36 force field with GAFF2 for non-standard groups.

- Solvation and Neutralization: Place protein in cubic box with TIP3P water molecules extending 1.0nm from protein surface. Add ions (0.15M NaCl) to neutralize system charge.

- Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent minimization (50,000 steps maximum) until maximum force <1000 kJ/mol/nm.

- Equilibration: Conduct NVT ensemble (100ps, 310K, V-rescale thermostat) with position restraints on protein heavy atoms. Follow with NPT ensemble (100ps, 310K, 1 bar, Parrinello-Rahman barostat).

- Production Simulation: Run unrestrained simulation (50-100ns) using 2fs time step with LINCS bond constraints. Analyze root mean square deviation, solvent accessible surface area, and residue interaction networks using GROMACS tools [14] [25].

Molecular Dynamics Simulations in PTM-Cancer Research

Molecular dynamics simulations have emerged as transformative tools for investigating PTM-mediated oncogenesis at atomic resolution, complementing experimental approaches by providing temporal depth and molecular detail inaccessible to conventional techniques [6]. MD simulations elucidate how PTMs induce allosteric changes that alter protein conformational landscapes, binding affinities, and interaction networks in cancer-related proteins [25]. Recent advances integrate MD with machine learning to predict PTM sites and their functional impacts, accelerating the identification of therapeutic targets [14].

Case Study: PTM-Induced Structural Fluctuations in Breast and Ovarian Cancer Proteomic profiling of plasma samples from breast and ovarian cancer patients identified cancer-specific PTM patterns, with 12 modified peptides across eight proteins characteristic of ovarian cancer and six peptides across three proteins specific to breast cancer [25]. MD simulations demonstrated that these PTMs localize in compact structural motifs with increased solvent-accessible surface area, creating conformational fluctuations that modulate protein activity without inducing structural degradation [25]. This PTM-induced structural plasticity enables cancer cells to rewire signaling networks and adapt to therapeutic pressures.

Case Study: Dioxin-Associated Liposarcoma Mechanisms Integrated machine learning and MD simulations revealed that TCDD (2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin) promotes liposarcoma through AhR activation and metabolic reprogramming [14]. Simulations identified five key proteins (CDH3, ADORA2B, MMP14, IP6K2, and HTR2A) as critical nodes in dioxin-mediated oncogenesis, with HTR2A inhibition by ketanserin showing therapeutic potential [14]. This approach demonstrates how MD simulations can bridge between toxicant exposure and oncogenic PTM networks.

PTM-Driven Oncogenic Signaling Networks

Table 2: PTM-Regulated Signaling Pathways in Cancer

| Pathway | Key PTM Types | Cancer Associations | Therapeutic Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| RTK-RAS | Phosphorylation, Ubiquitination | Altered in 45% of pan-cancer samples [26] | Kinase inhibitors, Combination therapies |

| PI3K-Akt | Phosphorylation, Acetylation | Metabolic reprogramming, Cell survival | AKT inhibitors, HDAC inhibitors |

| p53 | Phosphorylation, Acetylation, Lactylation, Ubiquitination | Genome instability, Loss of tumor suppression | MDM2 inhibitors, Reactivation strategies |

| Wnt/β-catenin | Phosphorylation, Acetylation | Stemness, Metastasis | Tankyrase inhibitors, β-catenin disruptors |

| Cell Cycle | Phosphorylation, Ubiquitination | Uncontrolled proliferation | CDK inhibitors, Proteasome inhibitors |

| Hippo | Phosphorylation, Lactylation | YAP/TAZ activation, Growth control | YAP-TEAD inhibitors, Verteporfin |

| TGF-β | Phosphorylation, Acetylation, Ubiquitination | EMT, Metastasis, Immune evasion | Kinase inhibitors, Antibodies |

PTMs function as molecular integrators that coordinate pathway crosstalk and signal amplification in oncogenic networks [27]. The pan-cancer analysis of 33 cancer types revealed that PTMs create shared patterns of protein regulation across histological lineages, with specific PTM signatures associated with DNA damage response, metabolism, and proliferation pathways [28]. Metabolite sensing represents a fundamental mechanism through which PTMs translate nutrient availability into regulatory signals, with metabolites functioning as substrates (acetyl-CoA for acetylation), allosteric regulators (succinate inhibiting demethylases), or covalent modifiers (lactate for lactylation) [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for PTM-Cancer Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Kits | TiOâ‚‚ Phosphopeptide Enrichment, Anti-Acetyl Lysine Antibody, SUMOylation Affinity Beads | Isolation of PTM-modified peptides from complex mixtures for proteomic analysis [25] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Orbitrap Tribrid Mass Spectrometers, TIMS-TOF, Q-Exactive Plus | High-resolution identification and quantification of PTM sites [25] [28] |

| MD Simulation Software | GROMACS, AMBER, CHARMM, NAMD | Atomic-level modeling of PTM-induced structural and dynamic changes [6] [14] [25] |

| Pathway Inhibitors | HDAC Inhibitors (Panobinostat), Kinase Inhibitors, SIRT Inhibitors | Functional validation of PTM-mediated regulatory mechanisms [23] [24] |

| Cell Line Models | Cancer Cell Panels (NCI-60), Patient-Derived Organoids, CRISPR-Modified Isogenic Lines | Context-specific investigation of PTM functions across cancer types [14] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | MaxQuant, CPTAC Data Portal, PathwayMapper, cBioPortal | PTM data analysis, visualization, and integration with genomic datasets [26] [28] |

| Clinical Datasets | TCGA, CPTAC, GEO Datasets (GSE21050, GSE30929) | Correlation of PTM patterns with clinical outcomes and therapeutic responses [26] [14] [28] |

| Omilancor | Omilancor, CAS:1912399-75-7, MF:C30H24N8O2, MW:528.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dobaq | Dobaq, CAS:1360461-69-3, MF:C49H83NO6, MW:782.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Therapeutic Targeting of PTM Networks in Oncology

The therapeutic targeting of PTM machinery represents a promising frontier in precision oncology, with numerous agents targeting writers, erasers, and readers in clinical development [23] [24]. HDAC inhibitors (e.g., panobinostat) reverse aberrant deacetylation patterns, while combination with metformin enhances efficacy through AMPK-mediated acetylation increases [23]. Kinase inhibitors targeting phosphorylation networks have transformed treatment for multiple malignancies, with pan-cancer analyses revealing opportunities for combination therapies in 30% of tumors harboring multiple targetable alterations [26].

Emerging strategies focus on targeting novel PTMs like lactylation, with AARS1 lactyltransferase inhibition showing potential for disrupting the lactate-YAP-TEAD proliferation axis in gastric cancer [23]. Similarly, succinylation modulation offers approaches for targeting mitochondrial metabolism in tumors with TCA cycle disruptions [21] [22]. The integration of PTM mapping with MD simulations accelerates drug discovery by enabling rational design of small molecules that allosterically disrupt pathological PTM-mediated interactions [6] [14].

The comprehensive mapping of post-translational modifications and their roles in oncogenesis provides a multidimensional understanding of cancer biology that transcends genomic alterations alone. PTMs represent dynamic regulators that integrate metabolic states, environmental cues, and signaling information to drive malignant progression through protein structural and functional rewiring. The continuing evolution of proteomic technologies, computational modeling, and therapeutic targeting strategies positions PTM research as a cornerstone of next-generation cancer investigation and treatment development. As molecular dynamics simulations increasingly bridge the gap between static structural information and dynamic cellular signaling networks, researchers gain unprecedented capability to simulate, predict, and therapeutically manipulate the PTM landscape that underlies cancer pathogenesis.

From Simulation to Therapy: Practical MD Applications in Oncology

The pursuit of precision medicine has positioned nanocarriers as transformative tools in oncology, capable of revolutionizing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing systemic toxicity. These sophisticated delivery systems function as molecular transport vehicles, engineered to navigate the biological landscape and deliver their pharmaceutical payloads with exceptional precision to malignant cells. Within this domain, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and liposomes have emerged as particularly promising platforms, each offering distinct advantages for targeted cancer therapy. Their optimization and application are profoundly enhanced by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which provide atomic-level insights into the complex interactions between drugs, carriers, and biological membranes [6] [3].

Molecular dynamics simulations have become an indispensable computational tool in rational nanocarrier design, offering researchers a "computational microscope" to observe phenomena that are challenging to capture experimentally [1]. By simulating the trajectories of atoms and molecules over time under the influence of classical force fields, MD enables the detailed study of drug encapsulation, carrier stability, cellular uptake mechanisms, and controlled release profiles. This approach is especially valuable for understanding the molecular mechanisms that govern the behavior of nanocarriers within biological systems, allowing for the pre-experimental screening and optimization of formulations [6]. The integration of MD simulations with traditional experimental methods creates a powerful synergistic workflow for accelerating the development of next-generation drug delivery systems with enhanced targeting capabilities and therapeutic outcomes [3].

Comparative Analysis of Carbon Nanotube and Liposome Nanocarriers

The strategic selection of an appropriate nanocarrier is fundamental to the success of any targeted drug delivery system. Carbon nanotubes and liposomes represent two distinct classes of nanocarriers with complementary characteristics. A thorough comparative analysis of their physicochemical properties, drug loading capacities, and functionalization potential provides critical insights for matching carrier capabilities to specific therapeutic requirements.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Carbon Nanotube and Liposome Nanocarriers

| Characteristic | Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Liposomes |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Cylindrical nanostructures of sp² hybridized carbon atoms [29] | Spherical vesicles composed of phospholipid bilayers [30] |

| Size Range | 2.5–100 nm in diameter [29] | Typically 50–200 nanometers [30] |

| Drug Loading Capacity | High surface area for substantial drug loading; can be covalently bonded, adsorbed, or encapsulated [31] | Encapsulation within aqueous core (hydrophilic drugs) or lipid bilayer (hydrophobic drugs) [30] |

| Functionalization | Can be oxidized or modified with targeting ligands (antibodies, peptides) [29] [31] | Surface modifiable with polyethylene glycol (PEG) for stealth properties and targeting ligands [30] [32] |

| Cellular Uptake Mechanism | Endocytosis-independent penetration; can perforate and diffuse through lipid bilayers [29] | Typically enter cells via endocytosis [30] |

| Biocompatibility | Requires functionalization to reduce potential toxicity; biocompatibility depends on functional groups [29] [33] | Inherently biocompatible and biodegradable due to phospholipid composition [30] |

| Clinical Translation Status | Predominantly in research phase; clinical use limited by toxicity concerns [33] | Multiple FDA-approved formulations; well-established clinical use [34] [32] |

The quantitative market data further illuminates the clinical trajectory of these technologies. The liposome drug delivery market, valued at $5.59 billion in 2024, is projected to reach $13.12 billion by 2034, growing at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.91% [32]. Cancer therapy applications dominate this market, holding a 54% share in 2024, with liposomal doxorubicin being the leading product segment at 36% market share [32]. This commercial success underscores the clinical validation of liposomal platforms, while carbon nanotubes represent an emerging technology with significant potential pending resolution of biocompatibility and manufacturing challenges.

Molecular Dynamics in Nanocarrier Optimization

Molecular dynamics simulations have revolutionized nanocarrier design by providing unprecedented atomic-level resolution of molecular interactions. MD simulations employ empirical force fields to calculate the forces acting on each atom, then numerically solve Newton's equations of motion to track atomic trajectories over time [1]. This approach enables researchers to study dynamic processes such as drug-carrier binding, carrier-membrane interactions, and drug release kinetics—phenomena that are often difficult to observe experimentally.

In optimizing carbon nanotubes for drug delivery, MD simulations have revealed crucial insights into the atomic-level interactions between functionalized CNT surfaces and anticancer drugs. For instance, simulations of doxorubicin (DOX) interacting with functionalized carbon nanotubes have demonstrated how π-π stacking, electrostatic interactions, and hydrogen bonding collectively contribute to drug loading stability [6] [3]. These simulations can predict the binding free energies of drug-carrier complexes, enabling rational selection of functional groups that optimize drug loading while maintaining appropriate release characteristics under specific physiological conditions [3].

For liposomal systems, MD simulations have been instrumental in understanding membrane fusion processes, lipid-drug interactions, and the effect of surface modifications on circulation time. Simulations can model the interaction of liposomes with cellular membranes at atomic resolution, providing insights into the molecular mechanisms of endocytosis and membrane fusion [6]. Additionally, MD studies have illuminated how PEGylation (stealth technology) creates a protective hydration layer around liposomes, reducing protein adsorption and extending circulation half-life—a key factor in targeted delivery [3]. The integration of machine learning algorithms with MD simulations is further accelerating nanocarrier optimization by enabling more efficient exploration of the vast design space and predicting structure-property relationships with reduced computational expense [6].

Carbon Nanotube Case Study: Dual Drug Delivery System

A groundbreaking 2024 study demonstrated the application of functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes (Æ’-MWCNTs) for the co-delivery of curcumin (CUR) and methotrexate (MTX) against breast cancer cells [35]. This innovative approach addressed the challenge of combining hydrophobic and hydrophilic chemotherapeutic agents in a single delivery system while leveraging the synergistic effects of dual-drug therapy.

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

The experimental workflow comprised a series of meticulously optimized steps:

Functionalization of MWCNTs: Pristine MWCNTs were treated with a mixture of Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„ and Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ to introduce carboxyl groups (MWCNT-COOH), enhancing dispersibility and providing attachment sites for drug molecules [35].

Methotrexate Conjugation: MTX was conjugated to Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) nanoparticles via amidic linkages to form BSA-MTX complexes, improving the solubility and stability of the drug [35].

Curcumin Loading: CUR was loaded onto the functionalized MWCNT-COOH nanoparticles through non-covalent interactions, forming Æ’-MWCNT-CUR complexes [35].

Assembly of Dual Delivery System: The Æ’-MWCNT-CUR and BSA-MTX were combined to form the final dual drug delivery system: Æ’-MWCNT-CUR-BSA-MTX [35].

Characterization: The formulations were comprehensively characterized using:

- Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) for particle size distribution [35]

- Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) for morphological analysis [35]

- Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) to confirm chemical functionalization [35]

- Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) to evaluate thermal stability and drug release profiles [35]

In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assessment: The antitumor efficacy was evaluated against MCF-7 breast cancer cells using the MTT colorimetric assay, comparing the dual system against individual components and free drugs [35].

Diagram Title: Carbon Nanotube Dual-Drug System Workflow

Key Findings and Therapeutic Outcomes

The Æ’-MWCNT-CUR-BSA-MTX dual delivery system demonstrated remarkable synergistic effects against MCF-7 breast cancer cells. The combination of CUR and MTX exhibited significantly enhanced cytotoxicity compared to either drug alone, with the nanocarrier facilitating improved cellular uptake and intracellular drug release [35]. The pH-responsive release characteristics of the system ensured stable drug carriage during circulation while promoting rapid drug release in the acidic tumor microenvironment, thereby maximizing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing off-target effects [35].

The unique properties of carbon nanotubes were crucial to the system's success. The high specific surface area of MWCNTs enabled substantial drug loading, while their needle-like morphology promoted efficient cellular internalization through direct membrane penetration [29] [35]. This case study exemplifies how molecular-level design of functionalized carbon nanotubes can overcome the pharmacological limitations of conventional combination therapy, particularly for drugs with divergent solubility profiles.

Liposome Case Study: Stealth Technology for Cancer Therapy

Liposomal doxorubicin (marketed as Caelyx/Doxil) represents one of the most successful clinical applications of nanocarrier technology, demonstrating the profound impact of surface engineering on therapeutic efficacy. This case study examines the development and optimization of stealth liposome technology for enhanced cancer therapy.

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

The development of optimized stealth liposomes involves a sophisticated manufacturing process with precise quality control measures:

Lipid Film Hydration: Phospholipids (typically including hydrogenated soy phosphatidylcholine), cholesterol, and PEGylated lipid (PEG-DSPE) are dissolved in organic solvent and evaporated to form a thin lipid film [30] [34].

Hydration and Size Reduction: The lipid film is hydrated with an ammonium sulfate buffer, forming multilamellar vesicles. Subsequent size reduction through extrusion or sonication produces uniform vesicles of 80-100nm [30].

Active Drug Loading: Doxorubicin is loaded using remote loading techniques driven by the pH gradient established by the ammonium sulfate buffer, achieving high encapsulation efficiency (>90%) [34].

Purification and Characterization: Unencapsulated drug is removed by chromatography or filtration. Final characterization includes:

In Vivo Pharmacokinetic Studies: Circulation half-life and biodistribution are evaluated in animal models, comparing stealth liposomes to non-PEGylated formulations and free doxorubicin [32].

Diagram Title: Stealth Liposome Fabrication Process

Key Findings and Therapeutic Outcomes

The implementation of stealth technology through PEGylation resulted in dramatically improved pharmacokinetic parameters compared to conventional liposomes and free doxorubicin. The polyethylene glycol created a protective hydrophilic layer around the liposome surface, reducing opsonization and recognition by the mononuclear phagocyte system [32]. This extended circulation half-life from just a few hours to approximately 55-80 hours in humans, allowing for enhanced accumulation in tumor tissue through the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect [34] [32].

Clinical outcomes demonstrated a significant reduction in cardiotoxicity—the dose-limiting side effect of doxorubicin—while maintaining equivalent antitumor efficacy [32]. The market success of liposomal doxorubicin, which holds a 36% share of the liposome drug delivery market, underscores the clinical impact of this stealth technology [32]. Furthermore, the stealth platform has been adapted for other chemotherapeutic agents, including liposomal paclitaxel and liposomal amphotericin B, demonstrating the versatility of this approach [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental methodologies described in the case studies require specialized reagents and analytical tools. The following table catalogues essential research solutions for nanocarrier development and characterization.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nanocarrier Development

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalized CNTs | Drug delivery backbone; require modification for biocompatibility [29] | Carboxylated MWCNTs (MWCNT-COOH) [35] |

| Phospholipids | Structural components of liposomes [30] | Hydrogenated soy phosphatidylcholine (HSPC), cholesterol [34] |

| PEGylated Lipids | Stealth functionality; extend circulation half-life [32] | DSPE-PEG (1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[amino(polyethylene glycol)]) [32] |

| Targeting Ligands | Enable active targeting to specific cell types [29] [31] | Antibodies, peptides, folic acid [29] |

| Characterization Instruments | Size, morphology, and surface analysis [30] [35] | Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS), Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) [35] |

| Analytical Instruments | Drug loading efficiency and release kinetics [35] | High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), UV/Visible Spectroscopy [35] |

| Cell Culture Models | In vitro efficacy and safety assessment [35] | MCF-7 breast cancer cells [35] |

| Betol | Betol, CAS:613-78-5, MF:C17H12O3, MW:264.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The optimization of carbon nanotubes and liposomes for targeted drug delivery represents a paradigm shift in cancer therapeutics, moving from nonspecific cytotoxic agents toward precision medicine approaches. The case studies examined in this review demonstrate how rational design—informed by molecular dynamics simulations and experimental validation—can yield nanocarrier systems with enhanced therapeutic efficacy and reduced side effects. Carbon nanotubes offer exceptional drug loading capacity and unique cellular uptake mechanisms, while liposomes provide inherent biocompatibility and clinical translatability, particularly when engineered with stealth technology.

The future of nanocarrier optimization lies in the convergence of computational and experimental approaches. Advances in high-performance computing and machine learning algorithms are enabling more sophisticated and accurate MD simulations, reducing the computational cost while increasing predictive power [6] [3]. The emerging frontier of multi-scale modeling will bridge atomic-level interactions with macroscopic physiological responses, providing a comprehensive framework for nanocarrier design [1]. Additionally, the growing emphasis on patient-specific simulations promises to advance personalized oncology, where nanocarriers can be tailored to individual tumor biology and genetic profiles [1].

As these technologies mature, we anticipate the development of increasingly sophisticated "smart" nanocarriers capable of responding to specific physiological triggers, delivering multiple therapeutic agents with precise spatial and temporal control, and adapting to the dynamic tumor microenvironment. The integration of molecular diagnostics with therapeutic delivery—creating theranostic platforms—will further enhance treatment monitoring and optimization. Through the continued refinement of carbon nanotubes, liposomes, and other nanocarrier systems, researchers are poised to dramatically improve the precision and effectiveness of cancer therapy, ultimately transforming patient outcomes in oncology.

The rational design of effective therapeutics relies on a deep understanding of the molecular interactions between drugs and their biological targets. For decades, binding affinity (thermodynamics) has been the primary optimization parameter in drug discovery. However, it has become increasingly evident that binding kinetics—the rates of association and dissociation—often provide a more accurate predictor of in vivo efficacy and safety profiles [36]. Drugs with similar binding affinities can exhibit drastically different residence times within their target receptors, leading to profound variations in therapeutic outcomes [37]. This is particularly relevant in oncology, where drugs like doxorubicin must navigate complex cellular environments to reach their intended targets.