Molecular Docking in Breast Cancer Drug Discovery: A Practical Guide from Target Identification to Clinical Translation

This comprehensive review explores the practical application of molecular docking in breast cancer research, addressing the needs of researchers and drug development professionals.

Molecular Docking in Breast Cancer Drug Discovery: A Practical Guide from Target Identification to Clinical Translation

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the practical application of molecular docking in breast cancer research, addressing the needs of researchers and drug development professionals. It covers foundational concepts of key breast cancer targets including ER, HER2, and emerging targets for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). The article provides methodological guidance on docking workflows, virtual screening, and integration with molecular dynamics simulations. Critical troubleshooting sections address validation challenges and limitations of computational predictions, while validation frameworks demonstrate successful integration with experimental approaches through case studies. This resource bridges computational predictions with biological relevance to enhance breast cancer therapeutic development.

Understanding Breast Cancer Targets: From Established Receptors to Emerging Vulnerabilities

Breast cancer is a genetically and clinically heterogeneous disease, categorized into distinct molecular subtypes based on the expression of key biomarkers: estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). These subtypes—Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2-enriched, and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)—exhibit unique biological behaviors, prognostic outcomes, and therapeutic responses [1] [2]. The precise identification of these molecular targets is foundational to modern precision oncology, enabling the development of targeted therapies that significantly improve patient survival.

Beyond the established targets of endocrine and anti-HER2 therapies, research continues to identify and validate novel biomarkers and signaling pathways. These include the androgen receptor (AR), components of the cGAS-STING pathway, and various immune checkpoints, offering new avenues for therapeutic intervention, particularly in aggressive and treatment-resistant subtypes [3] [4]. This application note details the key molecular targets across breast cancer subtypes and provides a practical computational protocol for researchers to identify and evaluate potential therapeutic compounds through molecular docking.

Molecular Subtypes and Key Targets

The classification of breast cancer into intrinsic subtypes guides clinical decision-making. The table below summarizes the prevalence, key molecular features, and standard therapeutic approaches for each major subtype.

Table 1: Key Molecular Subtypes of Breast Cancer: Features and Management

| Subtype | Approximate Frequency | Defining Molecular Features | Primary Therapeutic Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luminal A | 30-40% [1] | ER-positive, PR-positive, HER2-negative, low Ki-67 [1] | Endocrine therapy (SERMs, AIs) [2] |

| Luminal B | 20-30% [1] | ER-positive, PR negative/low, HER2 negative/positive, high Ki-67 [1] | Endocrine therapy +/− chemotherapy, +/− HER2-targeted therapy (if HER2+) [2] |

| HER2-Enriched | 12-20% [1] | HER2-positive, ER-negative, PR-negative [1] | Anti-HER2 targeted therapy (e.g., Trastuzumab, DS-8201) + chemotherapy [3] [2] |

| Triple-Negative (TNBC) | 15-20% [1] | ER-negative, PR-negative, HER2-negative [1] | Chemotherapy; Immunotherapy (e.g., anti-PD-1/PD-L1); PARP inhibitors (if BRCA mutant) [3] [2] |

Established and Emerging Molecular Targets

Canonical Hormone Receptors and HER2

Estrogen Receptor (ER) and Progesterone Receptor (PR) The ER is a ligand-activated transcription factor that drives the proliferation and survival of luminal breast cancer cells. Endocrine therapies aim to block this signaling pathway and include Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs, e.g., tamoxifen), which compete with estrogen for receptor binding, and aromatase inhibitors, which reduce estrogen production in postmenopausal women [2] [5]. While effective, resistance frequently develops through mechanisms such as ESR1 mutations, which lead to constitutive, ligand-independent ER activation, and crosstalk with growth factor signaling pathways like PI3K/AKT/mTOR [2]. PR expression is a favorable prognostic marker and indicates a functionally intact ER pathway [1].

Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 (HER2) HER2 is a tyrosine kinase receptor that homodimerizes or heterodimerizes with other EGFR family members, activating potent downstream oncogenic cascades, primarily PI3K/AKT and RAS/MAPK, leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation and survival [2]. Targeted therapies like the monoclonal antibody trastuzumab have revolutionized treatment for HER2+ breast cancer. However, resistance remains a challenge, often mediated by the expression of truncated p95HER2 or activation of compensatory pathways [2]. Next-generation antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) like DS-8201 have shown efficacy even in the face of some resistance mechanisms [3].

Beyond ER, PR, and HER2: Emerging Targets

Androgen Receptor (AR) The AR is expressed in a substantial proportion of breast cancers, including 70-90% of ER-positive tumors and 30-50% of TNBCs [4]. Its role is complex and context-dependent, exhibiting both tumor-suppressive and tumor-promoting functions across different subtypes. In ER+ breast cancer, AR signaling can antagonize ER activity, but in some TNBC subsets (Luminal Androgen Receptor; LAR), it acts as a key oncogenic driver [4]. The emergence of AR splice variants (AR-Vs), which lack the ligand-binding domain and are constitutively active, presents a significant mechanism of resistance to AR-targeting therapies and a new therapeutic challenge [4].

The cGAS-STING Pathway The cGAS-STING pathway is a crucial component of the innate immune response. It is activated when the sensor cGAS detects cytosolic double-stranded DNA (e.g., from genomic instability or radiotherapy), leading to the production of type I interferons and other inflammatory cytokines that activate dendritic and T cells [3]. This pathway plays a dual role in breast cancer. In TNBC, STING agonists combined with radiotherapy can enhance anti-tumor immunity and improve response rates [3]. Conversely, chronic activation of the pathway in certain contexts may lead to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment, for example, by recruiting regulatory T cells (Tregs) in Luminal subtypes [3]. This makes it a compelling but complex target for immunotherapy.

Other Promising Targets

- PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway: Frequently hyperactivated in breast cancer via PIK3CA mutations or PTEN loss, this pathway is a central node in cell growth and survival and a common mechanism of resistance to HER2-targeted and endocrine therapies. Inhibitors like alpelisib (PI3Kα inhibitor) are approved for PI3CA-mutated, HR+/HER2- advanced breast cancer [2].

- Immune Checkpoints: Targets such as PD-1/PD-L1 are established in a subset of TNBCs. The KEYNOTE-355 trial demonstrated that the anti-PD-1 antibody pembrolizumab combined with chemotherapy extended progression-free survival in advanced TNBC [3].

- DNA Repair Pathways: TNBCs with BRCA1/2 mutations harbor deficiencies in homologous recombination repair, creating a vulnerability to PARP inhibitors, which induce synthetic lethality [2].

A Protocol for Molecular Docking to Investigate Breast Cancer Targets

Molecular docking is a computational method that predicts the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target protein (receptor). The following protocol provides a framework for using docking to identify and characterize potential inhibitors for breast cancer targets.

Protocol Workflow

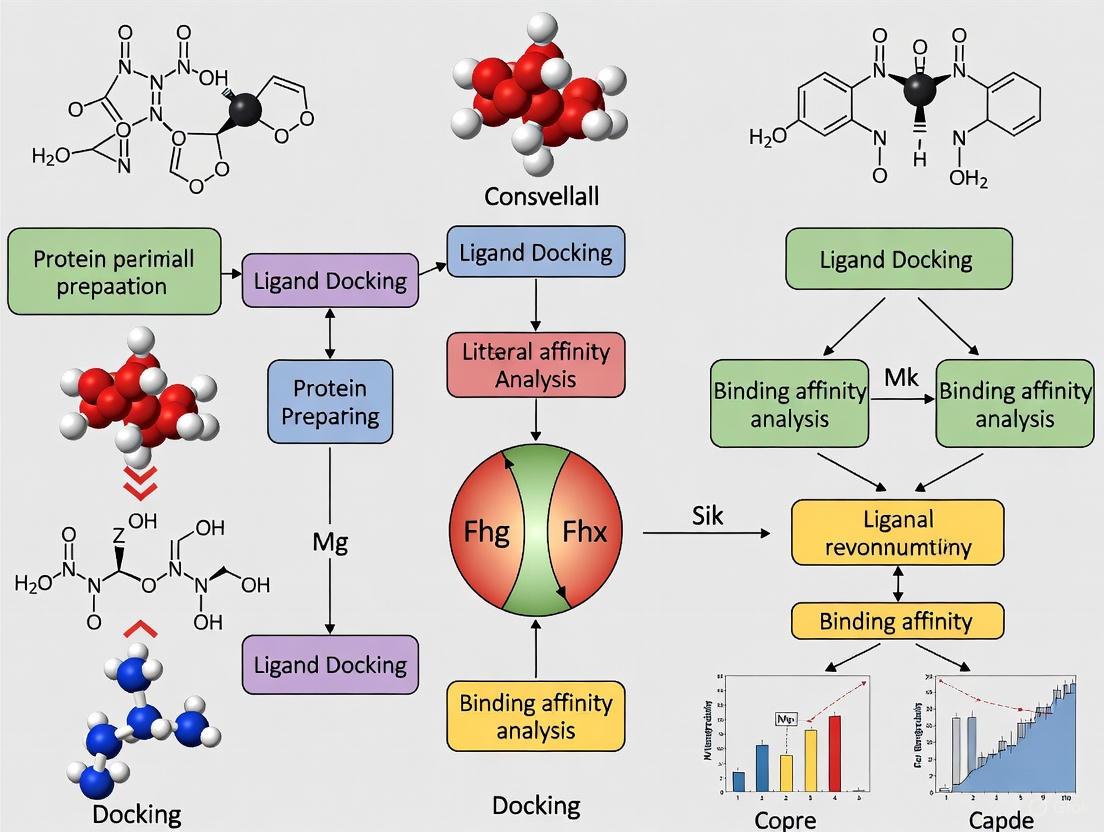

The diagram below outlines the key stages of a molecular docking experiment.

Step-by-Step Application Notes

Step 1: Target and Ligand Selection

- Target Preparation: Obtain the high-resolution 3D structure of the target protein (e.g., HER2, ER) from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). Common structures include PDB ID: 3PP0 for HER2 and 1G50 for ERα [6] [7]. Prepare the protein by removing water molecules and co-crystallized ligands, adding polar hydrogen atoms, and assigning Kollman partial charges using software like AutoDock Tools [7].

- Ligand Library Preparation: Select compound libraries from databases such as PubChem or ZINC [8]. Prepare ligands by sketching 2D structures (e.g., with BIOVIA Draw) and generating energetically minimized 3D conformations using tools like Avogadro with semi-empirical methods (e.g., PM3) [6].

Step 2: Molecular Docking Execution

- Grid Box Definition: Define a grid box around the protein's active site to confine the conformational search. For blind docking, the box may encompass the entire protein surface [6] [7].

- Docking Calculation: Perform docking using programs like AutoDock Vina [7] or DOCK3.7 [8]. These programs employ search algorithms (e.g., Genetic Algorithm in AutoDock, systematic search in DOCK) to explore ligand conformations and use scoring functions to predict binding affinity (e.g., in kcal/mol) [9]. Run multiple independent docking runs (e.g., 5-100) to ensure reproducibility.

Step 3: Post-Docking Analysis and Validation

- Pose Analysis: Analyze the top-ranked poses based on binding affinity and interaction patterns (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, pi-alkyl interactions). Discovery Studio Visualizer or PyMOL can be used for visualization [6] [10]. For example, camptothecin showed strong binding to HER2 mediated by hydrophobic and pi-alkyl interactions [6].

- Validation with Molecular Dynamics (MD): To account for protein flexibility and refine the docked poses, run MD simulations using software like GROMACS. Simulations (e.g., 100-200 ns at 310.15 K) allow you to assess the stability of the protein-ligand complex by analyzing metrics such as Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) and Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) [6] [7]. A stable RMSD profile indicates a reliable binding mode.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Docking in Breast Cancer Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function/Purpose | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Repository for 3D structural data of biological macromolecules. | Source of target receptor structures (e.g., HER2 PDB: 3PP0) [6] [7]. |

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking software for predicting ligand-protein interactions and binding affinity. | Performing docking screens to identify hits for ERα or HER2 [7]. |

| GROMACS | Software package for Molecular Dynamics simulations. | Refining docked poses and assessing complex stability over time [7]. |

| PubChem Database | Public repository of chemical molecules and their biological activities. | Source of small molecule ligands and natural products for screening [7]. |

| CHARMM Force Field | A set of parameters for modeling molecular systems in simulation programs. | Defining energy terms for atoms in MD simulations within GROMACS [7]. |

The landscape of molecular targets in breast cancer extends well beyond the foundational markers of ER, PR, and HER2. Emerging targets like the AR, cGAS-STING pathway, and key signaling nodes offer promising avenues for overcoming therapeutic resistance. Molecular docking serves as a powerful and accessible computational protocol for the initial identification and characterization of novel compounds that modulate these targets. When combined with experimental validation, this approach accelerates the discovery of next-generation therapies, moving us closer to truly personalized treatment for all breast cancer subtypes.

Emerging Therapeutic Targets in TNBC

Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (TNBC) is characterized by the absence of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression, making it unresponsive to conventional endocrine and HER2-targeted therapies [11] [12]. This aggressive subtype exhibits higher rates of recurrence, metastasis, and mortality compared to other breast cancers, creating an urgent need for novel targeted therapeutic strategies [11] [13]. Research has identified several promising molecular targets that address TNBC heterogeneity and therapeutic resistance.

Table 1: Emerging Molecular Targets in TNBC

| Target Category | Specific Target | Therapeutic Rationale | Therapeutic Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nuclear Receptors | Androgen Receptor (AR) | Expressed in a subset of TNBC; modulates cell proliferation and survival [14] | AR antagonists (e.g., bicalutamide, enzalutamide) |

| GTPase Signaling | RAC1B | Promotes breast cancer stem cell (BCSC) maintenance and chemoresistance; dispensable for normal mammary function [15] | Small molecule inhibitors targeting RAC1B splicing or activity |

| Stress & Inflammation | Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1α (HIF-1α) | Mediates adaptation to tumor hypoxia; promotes angiogenesis and metastasis [11] | HIF-1α pathway inhibitors |

| Tumor Necrosis Factor-α (TNF-α) | Regulates pro-inflammatory signaling in tumor microenvironment [11] [16] | Anti-TNF therapeutics | |

| Cell Invasion & Metastasis | Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) | Facilitates extracellular matrix degradation and tumor invasion [11] | MMP inhibitors |

| Ion Channels | Voltage-Gated Sodium Channels (VGSCs) | Promotes metastatic behaviors [11] | Sodium channel blockers |

| Cell Survival Pathways | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | Frequently dysregulated in TNBC; central to cell survival and growth [13] [16] | PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway inhibitors |

Experimental Protocols for Target Validation

Protocol: Molecular Docking for Target-Compound Interaction Analysis

Purpose: To predict binding interactions and affinities between potential therapeutic compounds (e.g., nomilin, PCB congeners) and TNBC molecular targets (e.g., EGFR, PARP1, TNF) [17] [18] [16].

Materials:

- High-performance computing workstation (Intel Xeon processor, 4 GB NVIDIA graphics card)

- Molecular docking software (AutoDock, Discovery Studio)

- Protein Data Bank structures of targets (e.g., BCL2:1K3K, Caspase3:1CP3, EGFR:2XKN)

- Compound structures in SDF or MOL2 format

Procedure:

- Protein Preparation: Obtain 3D crystal structures from PDB database. Remove water molecules, add hydrogen atoms, and assign partial charges using AutoDock Tools [16].

- Ligand Preparation: Sketch or download compound structures from PubChem. Optimize geometry, minimize energy, and convert to PDBQT format.

- Grid Box Setup: Define binding pocket coordinates to encompass known active sites or entire protein surface for blind docking.

- Docking Execution: Run molecular docking simulations using Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm with population size of 150 and maximum energy evaluations of 2,500,000 [19].

- Analysis: Evaluate binding poses based on LibDock scores and binding energies. Compounds with LibDock scores >130 indicate strong binding potential [19]. Visualize hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and binding conformations.

Protocol: In Vitro Assessment of Compound Efficacy in TNBC Models

Purpose: To evaluate the effects of candidate compounds on TNBC cell proliferation, apoptosis, and stemness.

Materials:

- TNBC cell lines (MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-453, MCF-7)

- Candidate compounds (e.g., nomilin, androgen receptor modulators)

- Cell culture reagents and equipment

- MTT assay kit, apoptosis detection kit (Annexin V/PI)

Procedure:

- Cell Culture: Maintain TNBC cells in appropriate media (RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS) at 37°C with 5% CO₂.

- Compound Treatment: Seed cells in 96-well plates (5,000 cells/well). After 24h, treat with serially diluted compounds (0-100 µM) for 48-72h [20] [16].

- Viability Assessment: Add MTT reagent (0.5 mg/mL) and incubate 4h. Dissolve formazan crystals in DMSO and measure absorbance at 570nm. Calculate IC₅₀ values [19].

- Apoptosis Analysis: Harvest treated cells, stain with Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide. Analyze by flow cytometry within 1h.

- Clonogenic Assay: Plate cells at low density (500/well), treat with compounds for 10-14 days, fix with methanol, stain with crystal violet, and count colonies.

- Statistical Analysis: Perform experiments in triplicate. Express data as mean ± SD. Analyze using Student's t-test or ANOVA with p<0.05 considered significant.

Protocol: Network Pharmacology for Multi-Target Drug Discovery

Purpose: To identify potential therapeutic targets and mechanisms of natural compounds against TNBC using an integrated bioinformatics approach [17] [16].

Materials:

- TNBC transcriptome data (TCGA-BRCA dataset)

- Compound target databases (SwissTargetPrediction, ChEMBL, STITCH)

- Bioinformatics tools (R packages: limma, ClusterProfiler, Cytoscape with CytoHubba plugin)

Procedure:

- Target Identification:

- Retrieve TNBC-related genes from TCGA using differential expression analysis (|logFC| >1, adjusted p<0.05) [16].

- Predict compound targets using SwissTargetPrediction with compound SMILES from PubChem.

- Identify overlapping targets using Venny tool.

Network Construction:

- Import shared targets into STRING database to construct Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) network with confidence score >0.7.

- Visualize network using Cytoscape and identify hub genes using CytoHubba plugin with degree, closeness, and betweenness centrality algorithms.

Enrichment Analysis:

- Perform GO and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis using ClusterProfiler with p<0.05.

- Identify significantly enriched pathways (e.g., PI3K-Akt, MAPK signaling).

Signaling Pathways in TNBC: Visualization and Therapeutic Implications

The following diagram illustrates key signaling pathways in TNBC and potential therapeutic intervention points:

TNBC Signaling Pathways and Therapeutic Targets

The diagram above illustrates the complex signaling network in TNBC, highlighting three key pathways and their interconnections. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (green) is frequently activated in TNBC through receptor tyrosine kinases (EGFR, IGFR) or androgen receptor signaling, promoting cell survival and proliferation [13]. The MAPK pathway (red) drives proliferative signals, while RAC1B (blue) maintains cancer stem cells and confers chemoresistance [15]. Critical cross-talk between these pathways underscores the need for combination therapies. Emerging natural compounds like nomilin have demonstrated multi-target activity against core nodes in this network, particularly impacting the PI3K/AKT axis [16].

Research Reagent Solutions for TNBC Investigation

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for TNBC Target Validation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Line Models | MDA-MB-231, MDA-MB-453, MCF-7 | In vitro compound screening and mechanism studies | MDA-MB-453: AR-positive; MCF-7: ER-positive control [20] [19] |

| Chemical Inhibitors | PI3K/AKT pathway inhibitors, AR antagonists (bicalutamide) | Target validation and combination therapy studies | Specific pathway blockade to assess functional contributions |

| Natural Compounds | Nomilin, PCB congeners (PCB 105, PCB 183) | Investigation of multi-target therapeutic approaches | Nomilin: targets PI3K/AKT pathway; PCBs: environmental risk factor study [17] [16] |

| Antibodies | Anti-AR, anti-pAKT, anti-RAC1B, anti-Ki67 | Immunohistochemistry and Western blot analysis | Target protein expression and phosphorylation status assessment |

| Computational Tools | AutoDock, Discovery Studio, Cytoscape with CytoHubba | Virtual screening and network pharmacology | Binding affinity prediction and hub gene identification [17] [16] |

| Database Resources | TCGA-BRCA, CTD, STRING, PubChem | Bioinformatics analysis and target identification | TNBC genomic data and compound-target interaction information [17] [16] |

The investigation of emerging targets like AR, RAC1B, and components of the PI3K/AKT pathway represents a promising frontier in TNBC therapeutics. The integrated approach combining computational prediction (network pharmacology, molecular docking) with experimental validation provides a powerful framework for accelerating drug discovery. Particularly compelling is the role of RAC1B in maintaining breast cancer stem cells and conferring chemoresistance while being dispensable for normal mammary gland function, positioning it as an attractive therapeutic target with potential for reduced toxicity [15]. Future research directions should prioritize the development of isoform-specific inhibitors, rational combination therapies addressing pathway cross-talk, and biomarker-driven patient stratification to maximize therapeutic efficacy in this challenging breast cancer subtype.

Molecular docking serves as a critical computational technique in structure-based drug design, enabling researchers to predict how small molecule ligands interact with macromolecular targets at the atomic level. The accuracy and reliability of docking studies are fundamentally dependent on the quality of the three-dimensional structural data used as input. The Protein Data Bank (PDB) serves as the single global repository for experimentally determined structural data of biological macromolecules, archiving over 200,000 structures as of recent surveys [21]. Within the context of breast cancer research, where targeting specific overexpressed receptors like HER2, ERα, and MCL-1 is paramount, selecting optimal structures from the PDB becomes a crucial first step in any computational workflow [22] [7].

This application note provides a structured framework for accessing, evaluating, and preparing PDB structures specifically for docking studies targeting breast cancer proteins. We integrate current PDB resources with established computational protocols to create a standardized workflow that enhances the reliability of virtual screening and drug discovery efforts.

Accessing and Curating Structures from the PDB

The RCSB Protein Data Bank (RCSB.org) serves as the primary access point for the PDB archive, providing both basic and advanced search capabilities alongside integrated analysis tools [23]. The database is continuously updated, with recent developments including the integration of computed structure models from artificial intelligence/machine learning alongside experimentally determined structures [23]. For breast cancer researchers, targeted searches can be performed using specific protein identifiers (e.g., PDB ID), gene names (e.g., "ESR1" for ERα), or disease terms.

Specialized resources have emerged to address the challenge of identifying biologically relevant structures among the vast PDB archive:

- BioLiP2: This semi-manually curated database provides quality-filtered protein-ligand interactions, assessing functional relevance through geometric rules and experimental literature validation [24]. Each entry includes annotations on ligand-binding residues, binding affinity, catalytic sites, and Gene Ontology terms, making it particularly valuable for docking template selection.

- PDB-101: An educational portal that offers guidance for understanding PDB data, including detailed explanations of coordinate files and data quality metrics [25].

Table 1: Key Database Resources for Structural Data Retrieval

| Resource Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Relevance to Docking |

|---|---|---|---|

| RCSB PDB [23] | Primary repository | Advanced search, structure visualization, integrated analysis tools | Direct source of 3D structural data in PDB format |

| BioLiP2 [24] | Curated binding interactions | Biologically relevant interactions, binding affinity data, functional annotations | Filtering for structures with confirmed biological activity |

| PDB-101 [25] | Educational resource | Guides to data interpretation, quality assessment tutorials | Understanding structure quality metrics |

Quantitative Metrics for Structure Selection

When selecting structures for docking studies, multiple quantitative parameters must be evaluated to ensure reliability. The resolution of crystallographic structures represents the most fundamental quality metric, with higher resolution (lower numerical value) generally indicating more precise atomic coordinates. Additional parameters include R-factor values, which measure agreement between the structural model and experimental data, and the B-factor (temperature factor), which indicates atomic displacement and flexibility.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Metrics for Evaluating PDB Structures for Docking

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Acceptable Range | Interpretation & Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution | ≤ 2.0 Å | ≤ 3.0 Å [22] | Higher resolution provides more precise atomic coordinates for binding site definition |

| R-factor (Rfree) | ≤ 0.20 | ≤ 0.25 | Measures agreement between model and experimental data; lower values indicate better quality |

| B-factor (average) | 10-30 Ų | 10-50 Ų | Indicates atomic mobility; extremely high values suggest disorder in specific regions |

| Clashscore | < 10 | < 20 | Measures steric overlaps; lower values indicate better stereochemical quality |

| Ramachandran Outliers | < 0.5% | < 2% | Percentage of residues in disallowed regions; lower values indicate better backbone geometry |

For breast cancer targets specifically, researchers should prioritize structures complexed with relevant ligands (e.g., inhibitors, substrates) when available, as these often present the binding site in a biologically relevant conformation. For instance, studies targeting REV-ERBα in breast cancer have utilized structures with resolution ≤ 3.0 Å for docking analyses [22].

Experimental Protocols for Structure Preparation and Docking

Comprehensive Workflow for Structure Preparation and Docking

The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from structure retrieval to docking validation, specifically tailored for breast cancer drug targets:

Protocol 1: Structure Retrieval and Quality Assessment

Objective: To identify and retrieve high-quality structures of breast cancer targets from the PDB.

Materials:

- RCSB PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org/)

- BioLiP database (https://zhanggroup.org/BioLiP)

Procedure:

- Target Identification: Define specific breast cancer target (e.g., HER2, ERα, MCL-1, REV-ERBα)

- Database Search:

- Navigate to RCSB PDB advanced search interface

- Input target name or gene symbol in search field

- Apply filters: "Experimental Method" (X-ray, Cryo-EM), "Resolution" (≤ 3.0 Å), "Organism" (Homo sapiens)

- Structure Evaluation:

- Review structure summary page for resolution, R-value, and experimental details

- Examine "Macromolecules" tab for protein chains and relevant ligands

- Check "Sequence" tab for completeness, noting any missing residues in binding regions

- Access "3D View" tab to visually inspect binding site integrity

- Ligand Validation:

- Cross-reference with BioLiP database to confirm biological relevance of bound ligands

- Verify that ligand binding site corresponds to known functional domains

- Data Retrieval:

- Download PDB file using "Download Files" option

- Select "PDB Format" for standard structural data

Troubleshooting:

- If structures have missing loops or residues, utilize homology modeling with MODELLER software to complete missing regions [22]

- For structures with poor electron density in binding sites, consider alternative structures or computational refinement

Protocol 2: Structure Preparation for Docking

Objective: To prepare protein and ligand structures for molecular docking simulations.

Materials:

- AutoDock Tools (https://ccsb.scripps.edu/mgltools/downloads/)

- PyMOL (https://pymol.org/edu/)

- PDBFixer or similar structure repair tools

Protein Preparation Procedure:

- Initial Processing:

Structure Repair:

- Add missing hydrogen atoms using AutoDock Tools or PDBFixer

- Assign protonation states appropriate for physiological pH (7.4)

- For histidine residues, determine appropriate tautomer based on hydrogen bonding pattern

File Format Conversion:

- Convert protein structure to PDBQT format using AutoDock Tools

- Assign Kollman partial charges and AutoDock atom types during conversion

- Define flexible residues in the binding site if using advanced docking methods

Ligand Preparation Procedure:

- Source Identification:

- Obtain ligand structures from PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/)

- Download in 3D SDF or similar format

Structure Optimization:

- Convert 2D structures to 3D using Avogadro software [22]

- Perform energy minimization to ensure proper geometry

- Assign appropriate torsion degrees of freedom for flexible bonds

File Format Conversion:

- Convert ligand to PDBQT format using AutoDock Tools

- Define rotatable bonds for docking flexibility

Protocol 3: Molecular Docking Execution and Analysis

Objective: To perform molecular docking and analyze binding interactions.

Materials:

- AutoDock Vina (https://vina.scripps.edu/)

- PyMOL or UCSF Chimera for visualization

- PoseView or similar interaction diagram tools [21]

Docking Execution:

- Grid Box Definition:

- Identify binding site coordinates from existing ligand in reference structure

- Set grid box dimensions to encompass entire binding site with 5-10 Å margin

- Use AutoDock Tools to define center coordinates and box size

Docking Parameters:

- Configure exhaustiveness value (default 8, increase to 24-32 for more accurate results)

- Set number of binding modes to generate (typically 10-20)

- Define energy range for clustering similar conformations

Docking Execution:

- Run AutoDock Vina with prepared receptor and ligand PDBQT files

- Execute multiple independent runs to assess consistency of results

Interaction Analysis:

- Pose Clustering:

- Group similar binding poses using RMSD-based clustering

- Select lowest energy representative from largest cluster

Interaction Mapping:

- Visualize protein-ligand complex in PyMOL or Chimera

- Identify hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, and π-interactions

- Generate 2D interaction diagrams using PoseView [21]

Binding Affinity Estimation:

- Record Vina binding scores (in kcal/mol) for all poses

- Compare with known reference inhibitors when available

- Calculate theoretical inhibition constants from binding energies

Breast Cancer Target Case Study: REV-ERBα and MCL-1

REV-ERBα Circadian Rhythm Protein

Recent research has identified REV-ERBα (NR1D1), a core component of the circadian clock, as a promising therapeutic target for breast cancer. Studies have demonstrated that the pyrrole derivative SR9009 exhibits significant binding affinity for REV-ERBα, with molecular dynamics simulations showing binding energy of -220.618 ± 19.145 kJ/mol, substantially higher than the conventional chemotherapeutic doxorubicin (-154.812 ± 18.235 kJ/mol) [22]. The following diagram illustrates the molecular interactions and downstream effects of targeting REV-ERBα in breast cancer:

MCL-1 Anti-Apoptotic Protein

MCL-1 represents another critical breast cancer target as an anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family protein that enables cancer cell survival. Research has identified hesperidin, a natural compound from citrus, as a potent MCL-1 inhibitor. Molecular dynamics simulations demonstrated stable binding over 200 ns at 310.15 K, with the hesperidin-MCL-1 complex maintaining structural integrity throughout the simulation period [7]. When encapsulated in nanoliposomes, hesperidin showed enhanced cytotoxicity against MDA-MB-231 triple-negative breast cancer cells (IC50 62.93 μg/mL) while demonstrating minimal effects on normal MCF10A breast cells.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Docking Studies

| Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Application in Workflow | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Databases | RCSB PDB [23] | Primary source of experimental structures | https://www.rcsb.org/ |

| BioLiP2 [24] | Curated biologically relevant interactions | https://zhanggroup.org/BioLiP | |

| Structure Preparation | AutoDock Tools [26] | Adding hydrogens, assigning charges, PDBQT conversion | https://ccsb.scripps.edu/mgltools/downloads/ |

| PyMOL [22] | Structure visualization, editing, and analysis | https://pymol.org/edu/ | |

| PDBFixer [27] | Repairing missing residues, adding missing atoms | https://github.com/openmm/pdbfixer | |

| Docking Software | AutoDock Vina [26] | Molecular docking and virtual screening | https://vina.scripps.edu/ |

| MGL Tools [22] | Pre- and post-docking analysis | https://ccsb.scripps.edu/mgltools/downloads/ | |

| Ligand Resources | PubChem [22] | Small molecule structure database | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ |

| Avogadro [22] | 2D to 3D structure conversion and editing | https://avogadro.cc/ | |

| Analysis & Visualization | PoseView [21] | 2D protein-ligand interaction diagrams | https://proteins.plus/ |

| UCSF Chimera [21] | Structure analysis and figure generation | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/ | |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS [22] | Molecular dynamics simulations | http://www.gromacs.org/ |

The systematic approach to accessing, selecting, and preparing PDB structures outlined in this application note provides a robust framework for conducting reliable molecular docking studies targeting breast cancer proteins. By integrating quantitative structure evaluation with standardized preparation protocols and validation techniques, researchers can significantly enhance the predictive accuracy of their computational drug discovery pipelines. The continued development of curated databases like BioLiP2 and improved structure prediction methods promises to further strengthen these approaches, accelerating the identification of novel therapeutic candidates for breast cancer treatment.

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) presents a significant therapeutic challenge due to the absence of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression, which limits treatment options [28]. Among the emerging targets in TNBC, the androgen receptor (AR) has gained considerable attention, with studies reporting AR expression in approximately 25%-35% of TNBC cases [29]. The luminal androgen receptor (LAR) subtype of TNBC, characterized by high AR expression, represents a distinct molecular entity with unique therapeutic vulnerabilities [30]. This case study explores the integration of bioinformatics approaches to identify AR as a hub gene in TNBC and the subsequent experimental validation of its therapeutic relevance.

Bioinformatics Analysis Workflow

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The bioinformatics pipeline typically begins with acquiring large-scale genomic data from public repositories. In a representative study analyzing AR-positive TNBC, researchers utilized the GSE76124 dataset from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, which contained gene expression profiles of TNBC samples classified into different subtypes, including the AR-positive LAR subtype and other subtypes (MES, BLIA, BLIS) [29]. Similar methodologies have been applied in hepatocellular carcinoma studies, confirming the robustness of this approach [31].

Key Databases for Bioinformatics Analysis:

- Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO): Repository of high-throughput gene expression data

- The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): Comprehensive cancer genomics dataset

- cBioPortal: Resource for visualization and analysis of multidimensional cancer genomics data

- STRING: Database of known and predicted protein-protein interactions

Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs)

Differential expression analysis between AR-positive TNBC samples and other TNBC subtypes was performed using the limma package in R, with statistical significance thresholds typically set at adjusted p-value < 0.05 and |logFC| > 1 [29]. This analysis identified 88 differentially expressed genes specifically associated with AR-positive TNBC.

Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA)

WGCNA was employed to construct co-expression networks and identify modules of highly correlated genes. This systems biology method groups genes into modules based on their expression patterns across samples, with the purple module specifically associated with AR-positive TNBC in the GSE76124 dataset [29]. The intersection of WGCNA module genes and DEGs provided high-confidence candidate genes.

Functional Enrichment Analysis

Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analyses were conducted to elucidate the biological functions and pathways enriched in the identified gene set. These analyses revealed significant involvement in hormone response pathways and cancer-related processes [29] [31].

Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Network Construction

The Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING) database was used to construct a PPI network, which was visualized and analyzed using Cytoscape software. The cytoHubba plugin identified hub genes within the network using the Maximal Clique Centrality (MCC) method [29] [32].

Table 1: Top 10 Hub Genes Identified in AR-Positive TNBC

| Hub Gene | Full Name | Biological Function | Expression in AR+ TNBC |

|---|---|---|---|

| TFF1 | Trefoil Factor 1 | Mucosal protection and repair | Upregulated |

| FOXA1 | Forkhead Box A1 | Transcription factor, pioneer factor for AR | Upregulated |

| ESR1 | Estrogen Receptor 1 | Estrogen receptor signaling | Upregulated |

| AGR2 | Anterior Gradient 2 | Protein folding and processing | Upregulated |

| TFF3 | Trefoil Factor 3 | Mucosal protection and repair | Upregulated |

| AGR3 | Anterior Gradient 3 | Protein folding and processing | Upregulated |

| GATA3 | GATA Binding Protein 3 | Transcription factor, luminal differentiation | Upregulated |

| XBP1 | X-Box Binding Protein 1 | Transcription factor, ER stress response | Upregulated |

| SPDEF | SAM Pointed Domain Containing ETS Transcription Factor | Epithelial cell differentiation | Upregulated |

| TOX3 | TOX High Mobility Group Box Family Member 3 | Transcription factor, cancer susceptibility | Upregulated |

Experimental Validation

In Vitro Models for AR-Positive TNBC

Experimental validation of bioinformatics predictions utilized both human and canine TNBC cell lines, leveraging the comparative oncology approach. The SUM149 human inflammatory breast cancer cell line (with low AR-positivity) and IPC-366 canine inflammatory mammary cancer cell line (with high AR-positivity) were cultured under standard conditions [30]. These models shared biological and histopathological characteristics, making them suitable for comparative studies.

AR Antagonists and Sensitivity Assays

Multiple AR antagonists were evaluated for their efficacy in TNBC models:

- First-generation AR antagonists: Nilutamide and Bicalutamide

- Next-generation compounds: VPC-13566 (targets AR binding function 3) and Ailanthone (inhibits transcriptional activity of full-length and splicing variant AR)

Sensitivity assays were performed by seeding cells in 96-well plates and treating with 5-fold serial dilutions of each compound. After 72 hours of incubation, cell viability was measured using MTT assay, and EC50 values were calculated using GraphPad Prism software [30].

Functional Assays

Cell viability and migration assays were conducted following AR antagonist treatment. For viability assays, cells were cultured in 96-well plates at a density of 10^4 cells per well and treated with 1 μM of each AR antagonist. Migration characteristics were evaluated using appropriate methods such as wound healing or Transwell assays [30].

Key Findings and Therapeutic Implications

Prognostic Significance of Hub Genes

Survival analysis of the identified hub genes revealed that TFF1 was the only gene significantly associated with lower survival rates in TNBC patients [29]. This finding positions TFF1 as a potential prognostic biomarker and therapeutic target in AR-positive TNBC.

miRNA Regulatory Network

Bioinformatics analysis further identified two miRNAs, hsa-miR-520g-3p and hsa-miR-520h, as potential regulators of TFF1 expression. These miRNAs were predicted to participate in the regulatory mechanisms of AR-positive TNBC development [29].

AR Signaling Mechanisms in TNBC

Experimental studies demonstrated that AR promotes tumor progression in TNBC through multiple mechanisms:

- Upregulation of EGFR expression, driving cell proliferation through MAPK and PI3K signaling pathways

- Downregulation of Src expression, preventing the antiproliferative effects of ERβ

- Dependence on hormonal signals, highlighting the importance of the balance between androgen and estrogen levels [30]

Potential Therapeutic Compounds

The Drug-Gene Interaction Database (DGIdb) was utilized to identify potential small molecule drugs targeting the hub genes in AR-positive TNBC [29]. Additionally, experimental studies identified Ailanthone as a potent AR antagonist that effectively blocked AR and Src expression in both canine and human TNBC cell lines, significantly reducing cell proliferation [30].

Table 2: Potential Therapeutic Compounds for AR-Positive TNBC

| Compound | Mechanism of Action | Experimental Evidence | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ailanthone | Inhibits transcriptional activity of full-length and AR splicing variants | Reduces cell proliferation in IPC-366 and SUM149 cell lines | Natural compound |

| Nilutamide | First-generation AR antagonist, blocks AR activation | Sensitivity demonstrated in TNBC cell lines | Synthetic |

| Bicalutamide | First-generation AR antagonist, blocks AR activation | Sensitivity demonstrated in TNBC cell lines | Synthetic |

| VPC-13566 | Targets AR binding function 3 (BF-3) | Inhibits AR transcriptional activity | Synthetic |

| Nomilin | Modulates PI3K/Akt pathway | Inhibits TNBC cell proliferation and migration, promotes apoptosis | Natural compound (limonoid) |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AR-TNBC Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | SUM149 (human), IPC-366 (canine) | In vitro models of TNBC with varying AR expression |

| AR Antagonists | Nilutamide, Bicalutamide, Ailanthone, VPC-13566 | Experimental modulation of AR signaling |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Cytoscape, STRING, GEO2R, cytoHubba | Network analysis, visualization, and hub gene identification |

| Databases | GEO, TCGA, DGIdb, cBioPortal | Data source for analysis and drug-gene interaction prediction |

| Assay Kits | MTT viability assay, Migration assay kits | Functional validation of therapeutic effects |

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Integrated Bioinformatics and Experimental Workflow for AR Target Identification in TNBC. The workflow illustrates the sequential process from data acquisition to experimental validation, highlighting the connection between computational predictions and laboratory verification.

Diagram 2: AR Signaling Mechanisms in TNBC and Therapeutic Intervention Points. The diagram illustrates the complex network of AR-mediated signaling in TNBC, highlighting key pathways and potential intervention points for AR-targeted therapies.

This case study demonstrates the powerful integration of bioinformatics approaches with experimental validation to identify and characterize AR as a hub gene in TNBC. The multi-step methodology encompassing differential expression analysis, WGCNA, PPI network construction, and hub gene identification successfully pinpointed AR and related genes as central players in a specific TNBC subtype. Subsequent experimental validation confirmed the functional significance of AR in TNBC progression and identified potential therapeutic compounds, including Ailanthone, that effectively target AR signaling. These findings provide a framework for future drug discovery efforts in AR-positive TNBC and highlight the value of bioinformatics-driven approaches in identifying novel therapeutic targets for precision oncology.

The Role of Protein Flexibility and Conformational States in Target Selection

In the field of targeted breast cancer therapy, the selection and interrogation of protein targets have traditionally relied on static structural models. However, proteins are dynamic entities that fluctuate between alternative conformational states, a property that is fundamental to their function. Protein flexibility and the population of specific conformational states present both a challenge and an opportunity in rational drug design [33]. Ignoring these dynamics can lead to the failure of drug discovery campaigns, as ligands often bind to and stabilize specific protein conformations. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on the practical application of molecular docking for breast cancer research, details the critical role of protein flexibility in target selection. We provide a structured overview of quantitative findings, detailed protocols for assessing flexibility, and visualization of key concepts to equip researchers with the tools to incorporate protein dynamics into their workflows for identifying more effective therapeutic interventions.

Computational Approaches for Incorporating Protein Flexibility

Effectively accounting for protein flexibility requires a suite of computational strategies. The choice of method often depends on the scale and type of conformational change expected in the target protein.

- Ensemble Docking: This involves docking against multiple, experimentally determined or computationally generated, protein conformations. A study on MDM2 inhibitors for breast cancer employed a two-stage docking strategy, beginning with rigid protein docking followed by ensemble docking using multiple MDM2 conformations derived from molecular dynamics simulations to identify natural terpenoid inhibitors [34].

- Advanced Sampling and Refinement Methods: Techniques like CABS-dock enable large-scale rearrangements of the protein backbone during docking, which is crucial for systems like the p53-MDM2 interaction that involves significant conformational changes in flexible "lid" regions [35]. Similarly, methods like FiberDock use normal mode analysis to model both large-scale and local backbone flexibility during the refinement of docking models [36].

- Energy-Weighted Conformations: A sophisticated approach involves deriving Boltzmann-weighted energy penalties from the refined occupancies of alternative conformations observed in apo crystal structures. This method allows for the prioritization of biologically relevant, low-energy conformational states during virtual screening [33].

Key Experimental Findings in Breast Cancer Research

The strategic application of flexible docking methods has yielded significant insights and identified promising compounds against challenging breast cancer targets. The table below summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies.

Table 1: Selected Computational Studies on Breast Cancer Targets Incorporating Protein Flexibility

| Target Protein | Identified Compound | Key Finding / Binding Affinity | Methodology for Flexibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDM2 [34] | 27-deoxyactein | MM-PBSA Binding Free Energy: -154.5 kJ/mol (Surpassed reference Nutlin-3a: -133.5 kJ/mol) | Ensemble docking with MDM2 conformations from MD simulations |

| VEGFR2 [37] | VT-6 (Cynaroside) | Docking Score: -14.6 kcal/mol; MM/GBSA: -34.7 kcal/mol | Molecular Dynamics Simulations (200 ns) |

| MLKL (Necroptosis) [38] | 8,12-dimethoxysanguinarine (SG-A) | Docking Score: -9.4 kcal/mol; MM-PBSA: -31.0 kcal/mol (Control: -24.0 kcal/mol) | Molecular Dynamics Simulations (300 ns) and PCA |

| Adenosine A1 Receptor [39] | Molecule 10 (Designed) | In vitro IC₅₀ in MCF-7 cells: 0.032 µM | Pharmacophore modeling & MD simulations (15 ns) |

| BRCA1 [40] | Curcumin | Binding Affinity: < -6.6 kcal/mol (Outperformed 5-FU: -5.6 kcal/mol) | Docking to wild-type and mutant BRCA1, followed by MD |

These findings underscore that incorporating flexibility is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity for discovering high-affinity ligands. For instance, the superior binding free energy of 27-deoxyactein over Nutlin-3a for MDM2 was only revealed through post-docking molecular dynamics simulations and MM-PBSA calculations, a protocol that accounts for dynamic stability [34]. Similarly, the stability of the top-ranked VEGFR2 inhibitor, VT-6, was conclusively demonstrated by its low RMSD (<3Å) and stable binding energy over a 200 ns simulation [37].

Experimental Protocols

Below is a detailed, step-by-step protocol for conducting a target selection and validation study that incorporates protein flexibility, integrating methods from several cited works.

Protocol 1: Ensemble Docking and Validation for a Breast Cancer Target

Objective: To identify and validate potential inhibitors for a flexible breast cancer target (e.g., MDM2, VEGFR2) using an ensemble docking and simulation approach.

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Target and Ensemble Preparation

- Identify Key Target: Select a therapeutically relevant protein with known flexibility (e.g., MDM2 in p53 pathway [34], VEGFR2 in angiogenesis [37]).

- Source Protein Structures: Obtain multiple receptor conformations from the PDB. This should include:

- Apo (ligand-free) structures.

- Holo (ligand-bound) structures with different chemotypes.

- If available, a single apo structure with multiple crystallographically refined conformations for key loops or side chains [33].

- Prepare Structures: Process all structures using standard preparation tools (e.g., in Maestro, MOE, or UCSF Chimera) to add hydrogens, assign bond orders, and optimize hydrogen bonding networks.

Ligand Library Preparation

Molecular Docking

- Rigid Docking Screen: Perform an initial high-throughput docking of the entire library against a single, high-resolution crystal structure to rapidly eliminate low-affinity binders.

- Ensemble Docking: Re-dock the top candidates (e.g., 100-500 compounds) from the first stage against the entire ensemble of protein conformations. Use a docking program capable of handling flexible side chains.

- Analyze Poses: Cluster the resulting poses and select top-ranked compounds based on consensus scoring and visual inspection of key interactions (e.g., with GLU917, ASP1046, and CYS919 in VEGFR2 [37]).

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations and Free Energy Calculations

- System Setup: Solvate the top protein-ligand complexes (e.g., 3-5) in an explicit water box and add ions to neutralize the system.

- Equilibration and Production Run: Energy-minimize the system, followed by equilibration and a production MD run for a sufficient duration to assess stability (typically 100-200 ns [34] [37]).

- Stability Analysis: Calculate Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF), and Radius of Gyration (Rg) to evaluate complex stability and conformational changes.

- Binding Affinity Calculation: Use the MM-PBSA or MM-GBSA method on trajectories from the stable simulation period to calculate binding free energies. This provides a more reliable estimate of affinity than docking scores alone [34] [38].

Experimental Validation

- In Vitro Assay: Synthesize or purchase the top-ranked computational hits and evaluate their efficacy in inhibiting proliferation of breast cancer cell lines (e.g., MCF-7, MDA-MB-231). Determine IC₅₀ values [39].

- Further Validation: If resources allow, validate the mechanism of action through specific biochemical or cell-based assays.

Protocol 2: Leveraging Crystallographic Occupancies for Energy-Weighted Docking

Objective: To use alternative conformations from a single apo crystal structure to guide docking with explicit energy penalties [33].

Workflow:

- Identify Flexible Regions: From a high-resolution apo crystal structure, identify residues with clear alternative conformations modeled in the electron density.

- Extract Occupancies: Obtain the refined crystallographic occupancy for each alternative conformation.

- Calculate Energy Penalties: Convert occupancies to energy penalties using the Boltzmann relationship:

Energy Penalty = -k_B * T * ln(Occupancy), where k_B is the Boltzmann constant and T is the temperature. - Generate Receptor Ensembles: Create a multi-conformer receptor model containing all significantly populated conformational states.

- Perform Docking with Penalties: Dock ligand libraries against this multi-conformer model, adding the corresponding conformational energy penalty to the docking score for each pose. This penalizes binding to high-energy (low-occupancy) conformations of the protein.

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

The following diagram illustrates the central role of protein conformational states in the MDM2-p53 signaling pathway, a key target in breast cancer, and how its inhibition can be leveraged therapeutically.

Figure 1: Targeting MDM2 conformational states to reactivate p53 tumor suppression in breast cancer. Inhibitors stabilize an inactive MDM2 conformation, blocking p53 degradation and restoring its anticancer functions.

The experimental workflow for integrating protein flexibility into drug discovery, as outlined in the protocols, is visualized below.

Figure 2: A comprehensive workflow for target selection and inhibitor discovery incorporating protein flexibility, from initial ensemble building to experimental validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Studying Protein Flexibility

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| CABS-dock [35] | Docking Server | Flexible protein-peptide docking allowing for large-scale backbone rearrangements. | Modeling the binding of p53 peptide to flexible MDM2 lid region. |

| FiberDock [36] | Docking Algorithm | Refines rigid-docking poses by modeling backbone flexibility using normal mode analysis. | Post-docking refinement to account for induced-fit changes. |

| GROMACS [39] | MD Simulation Software | Performs molecular dynamics simulations to study protein-ligand complex stability over time. | 150-200 ns simulations to validate stability and calculate MM-PBSA energies [34] [37]. |

| SwissTargetPrediction [39] | Bioinformatics Database | Predicts the most probable protein targets of a small molecule based on its 2D/3D similarity. | Initial target identification and intersection analysis for compound libraries. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Structural Database | Repository for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids, essential for sourcing conformations. | Sourcing apo and holo structures to build conformational ensembles for docking. |

| AMBER99SB-ILDN [39] | Molecular Force Field | A force field for MD simulations providing parameters for proteins, nucleic acids, and ligands. | Describing atomic interactions during MD simulations of protein-ligand complexes. |

Molecular Docking Workflows: From Virtual Screening to Binding Mode Analysis

Molecular docking is an indispensable technique in modern computational drug discovery, enabling the prediction of how a small molecule ligand binds to a protein target. Within breast cancer research, this method is crucial for identifying and characterizing novel inhibitors against key oncogenic targets. This protocol provides a standardized, step-by-step guide for performing molecular docking studies focused on breast cancer proteins, consolidating best practices from recent and authoritative studies in the field. The procedures outlined herein cover the complete workflow from initial protein and ligand preparation through to active site identification, docking execution, and parameter optimization, with specific examples relevant to breast cancer therapeutics.

Materials and Reagents

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Molecular Docking

| Item | Specification / Function | Example Sources / Software |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structures | 3D coordinates of target breast cancer proteins. | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [41] [6] [42] |

| Ligand Library | 2D or 3D structures of small molecules for screening. | IMPPAT 2.0, PubChem, COCONUT [41] [43] |

| Structure Preparation Suite | Adds H-bonds, removes water, minimizes energy. | Schrödinger Maestro, Discovery Studio [6] [42] [44] |

| Active Site Prediction Tool | Identifies potential binding pockets on the protein. | ProteinPlus, SiteMap, AADS [41] [45] [42] |

| Molecular Docking Software | Performs virtual screening and binding pose prediction. | AutoDock Vina, AutoDock Tools, Schrödinger Glide [41] [6] [43] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulates protein-ligand dynamics and stability. | GROMACS, AMBER, Desmond [41] [46] |

| Free Energy Calculation Module | Calculates binding free energies from simulation trajectories. | MM/GBSA, MM/PBSA [43] [42] [47] |

Methodology

Protein Preparation

The first critical step involves preparing the protein structure to ensure accurate and physiologically relevant docking results.

- Retrieval from PDB: Obtain the three-dimensional crystal structure of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org). For breast cancer, common targets include HER2 (PDB: 3PP0), EGFR (PDB: 1M17), PI3Kα (PDB: 5DXT), BRCA1 (PDB: 1T15), and BRCA2 (PDB: 3EU7) [41] [6] [42].

- Pre-processing: Using tools like the Protein Preparation Wizard in Schrödinger or the Prepare Protein module in Discovery Studio:

- Remove all water molecules and any non-essential heteroatoms (e.g., co-factors not involved in binding) [6] [44].

- Add missing hydrogen atoms to the structure.

- Assign appropriate bond orders and correct any misassigned atomic charges.

- For structures with missing loops or residues, use a homology modeling server like CHARMM-GUI to complete the model [6].

- Energy Minimization: Perform a constrained energy minimization of the protein structure using a force field such as OPLS_2005 or CHARMM. This step relieves steric clashes and optimizes the geometry of the added hydrogen atoms, resulting in a more stable and energetically favorable structure [42] [44]. The root mean square deviation (RMSD) for heavy atom displacement should be constrained to 0.3 Å to prevent significant deviation from the original crystal conformation.

Active Site Identification

Accurately defining the binding site is paramount for successful docking. Two primary approaches are commonly used:

- Literature and Co-crystal Ligand-Based Identification:

- If the protein has a co-crystallized inhibitor (e.g., Venetoclax in BCL2, PDB: 6O0K), the coordinates of this ligand define the active site [41].

- Consult relevant scientific literature to identify key residues in the protein's functional pocket.

- Computational Prediction:

- Use dedicated active site prediction servers such as ProteinPlus or AADS (Automated Active Site Detection, Docking, and Scoring) [41] [45]. These tools automatically detect surface cavities and score them based on physicochemical properties.

- Alternatively, use the SiteMap tool in Schrödinger to analyze the protein surface and identify the top candidate binding sites based on size, hydrophobicity, and hydrogen bonding potential [42].

Ligand Preparation

Small molecule ligands must be prepared to generate accurate, low-energy 3D conformations.

- Retrieval and Drawing: Source ligand structures from databases like PubChem or ZINC. For novel compounds, draw the 2D structure using a tool like BIOVIA Draw [6].

- Geometry Optimization:

- Convert the 2D structure to 3D coordinates using Avogadro or OpenBabel [41] [6].

- Perform energy minimization using semi-empirical quantum mechanical methods (e.g., PM3 in Gaussian) or molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., MMFF94 in OpenBabel). This step ensures the ligand is in a realistic, low-energy conformation before docking [41] [6].

Molecular Docking Execution and Parameter Optimization

This section details the setup and running of the docking calculation, which predicts the binding pose and affinity.

- Grid Generation: Define a 3D grid box that encompasses the entire binding site identified in Step 3.2. The center of the box should be the centroid of the known ligand or the predicted active site. The box size must be large enough to allow the ligand to rotate freely but constrained to reduce computational time. Typical grid dimensions and spacing used in recent studies are summarized in Table 2 [41].

- Docking Validation: Validate the docking protocol by re-docking the native co-crystallized ligand into its original binding site. A successful validation is achieved when the top-ranked docking pose closely matches the experimental pose, with a heavy-atom RMSD typically less than 2.0 Å [41].

- Virtual Screening: Execute the docking simulation using software such as AutoDock Vina or Schrödinger Glide. For large compound libraries, employ a hierarchical strategy: High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) followed by Standard Precision (SP) and finally Extra Precision (XP) docking to refine the results [43].

- Pose Analysis and Scoring: Analyze the top-ranking poses based on their docking scores (reported in kcal/mol). Visually inspect the key interactions (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, pi-pi stacking) between the ligand and critical amino acid residues using a molecular visualization tool like PyMOL or UCSF Chimera [6].

Table 2: Exemplar Docking Parameters and Results from Recent Breast Cancer Studies

| Target Protein (PDB ID) | Ligand / Compound | Grid Box Center / Size (points, spacing) | Docking Score (kcal/mol) | Key Interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BRCA2 (3EU7) [41] | Bayogenin | Centered on active site residues (from ProteinPlus) | -9.3 | N/A |

| HER2 (3PP0) [6] | Camptothecin | Blind docking over entire surface | Stronger than with EGFR | Hydrophobic, Pi-alkyl |

| PI3Kα (5DXT) [42] | Coumarin-derivative 2f | Binding site from SiteMap analysis | -9.3 | N/A |

| BCL-2 (6O0K) [46] | Berberine | Validated via self-docking with Venetoclax | -9.3 | N/A |

Diagram 1: A logical workflow for the molecular docking protocol, highlighting the critical validation feedback loop.

Advanced Validation and Analysis

For robust results, docking outcomes should be validated using more advanced computational techniques.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations:

- Solvate the protein-ligand complex in an explicit water model (e.g., TIP3P) and add ions to neutralize the system.

- Run a simulation for a minimum of 100 ns, although 200 ns is becoming standard for higher stability assessment [41] [46]. Monitor the stability of the complex by calculating the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) and Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) of the protein backbone and the ligand.

- Binding Free Energy Calculations:

- Use the Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) or MM/PBSA method on trajectories extracted from the MD simulation to calculate the binding free energy (ΔGbind) [43] [42] [47].

- The formula for calculating ΔGbind is: ΔGbind = Gcomplex - (Gprotein + Gligand), where each term comprises gas-phase molecular mechanics energy and solvation free energy [42].

Troubleshooting

- Poor Pose Reproduction in Validation: If the self-docking RMSD is too high (>2.0 Å), verify the active site definition and adjust the grid box size and center. Consider using a different docking algorithm or scoring function.

- Unrealistically High Binding Affinities: Check for unrealistic ligand conformations or clashes. Ensure the ligand was properly prepared and minimized prior to docking.

- Lack of Consensus in Poses: If multiple docking runs yield significantly different top poses, perform MD simulations to see which pose remains stable over time, as it is likely the true binding mode.

Virtual screening (VS) has become an indispensable tool in modern drug discovery, enabling the rapid and cost-effective identification of hit compounds from vast chemical libraries. Within oncology, and specifically for breast cancer research, VS strategies provide a powerful means to target key proteins involved in disease progression and treatment resistance. This document outlines detailed application notes and protocols for the virtual screening of both phytochemical and synthetic compound libraries, providing a structured framework for researchers targeting breast cancer pathways. By integrating computational predictions with experimental validation, these protocols support the accelerated discovery of novel therapeutic agents, addressing the urgent need for more effective breast cancer treatments, including against aggressive subtypes like triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [48] [41].

Target Identification and Compound Library Preparation

Key Breast Cancer Targets for Virtual Screening

The initial and most critical step in structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) is the selection of a biologically relevant protein target. For breast cancer, promising targets include signaling kinases, receptors, and proteins involved in DNA repair and apoptosis. High-penetrance genes such as BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, and BAX are particularly relevant in TNBC, as their mutation contributes to genomic instability and disease aggressiveness [41]. The adenosine A1 receptor has also been identified as a key candidate through target intersection analysis [39] [19]. Another pivotal target is Maternal Embryonic Leucine Zipper Kinase (MELK), a signaling protein crucial for cell growth, survival, and differentiation, and a promising therapeutic target for TNBC [48].

Table 1: Exemplary Protein Targets for Breast Cancer Virtual Screening

| Target Protein | PDB ID | Rationale in Breast Cancer |

|---|---|---|

| MELK | N/A | Pivotal role in cell growth/survival; overexpressed in TNBC [48] |

| Adenosine A1 Receptor | 7LD3 | Identified via target intersection analysis as a key candidate [39] [19] |

| BRCA2 | 3EU7 | High-penetrance gene; critical in DNA repair; mutated in TNBC [41] |

| BAX | 2G5B | Apoptosis regulator; restores cell death in cancer cells [41] |

Sourcing and Preparing Compound Libraries

Virtual screening efficacy is directly linked to the quality and diversity of the chemical library screened. Two primary library types are discussed: phytochemical and synthetic.

Phytochemical Library Construction: Natural product libraries offer structurally diverse compounds with multi-target potential. A protocol for building a focused phytochemical library is as follows:

- Source Compounds: Extract candidate compounds from specialized databases such as IMPPAT 2.0 (containing 17,967 phytochemicals from Indian medicinal plants) [41] or NPACT and PhytoHub [48].

- Retrieve Structures: Download 3D structures in SDF format from public databases like PubChem [39] [41].

- Ligand Preparation: Use tools like OpenBabel for format conversion and energy minimization (e.g., using the MMFF94 force field for 1000 steps) [41]. Alternatively, commercial suites like Schrödinger's LigPrep can generate 3D conformers, assign protonation states at physiological pH (e.g., 7.0 ± 2.0 using Epik), and optimize structures with a force field like OPLS4 [49].

Synthetic Compound Library Construction: Focused synthetic libraries are valuable for probing specific target classes.

- Library Selection: Utilize commercially available libraries, such as the Life Chemicals Anticancer Targeted Library, which contains over 13,600 drug-like molecules [50].

- Custom Curation: Select compounds based on 2D similarity to known actives (e.g., ≥80% Tanimoto similarity) or via direct molecular docking against the target of interest [50].

- Filtering: Apply filters to remove compounds with undesirable pan-assay interference (PAINS) motifs, reactive functional groups, or poor drug-likeness (e.g., violation of Lipinski's Rule of Five) [41] [50].

Core Virtual Screening Protocol

This section details a standard multi-tiered docking workflow for screening compound libraries against a prepared protein target.

Protein Preparation

The 3D structure of the target protein, obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), must be processed before docking:

- Import and Clean: Use a tool like Schrödinger's Protein Preparation Wizard or AutoDockTools. Remove all water molecules and heteroatoms not part of the co-crystallized ligand or crucial for catalysis [49] [41].

- Optimize and Minimize: Add missing hydrogen atoms, assign correct bond orders, and perform energy minimization using a force field (e.g., OPLS4 in Schrödinger or AMBER99SB-ILDN in GROMACS) to relieve steric clashes [39] [49].

Active Site Definition and Grid Generation

- Identify Binding Site: If the binding site is not known from a co-crystallized ligand, use a prediction server like ProteinPlus to identify key active site residues [41].

- Generate Grid: Define a 3D grid box around the binding site to confine ligand docking. The grid should be large enough to accommodate ligand flexibility. For example, in AutoDock Vina, grid dimensions and center points are set based on the residues lining the binding pocket [41].

Hierarchical Docking Workflow

To efficiently screen ultra-large libraries, a multi-step docking approach is employed, as illustrated below and in the accompanying workflow diagram.

Diagram 1: Hierarchical VS Workflow.

- High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS): Screen the entire library using a fast docking algorithm (e.g., HTVS mode in Glide) to rapidly filter out very weak binders. Retain the top 10% of compounds for further analysis [51] [49].

- Standard Precision (SP) Docking: Re-dock the filtered compounds with more rigorous scoring (e.g., SP mode in Glide). This step balances accuracy and computational cost. Select the top 10% of compounds from this stage [49].

- Extra Precision (XP) Docking: Dock the remaining candidates with the most precise and computationally intensive scoring function (e.g., XP mode in Glide) to accurately rank compounds based on predicted binding affinity and to eliminate false positives with unfavorable interactions [49].

Post-Docking Analysis and Hit Selection

Analyze the top-ranked XP poses for key interactions critical for binding affinity and specificity, such as:

- Hydrogen bonds with residues like Gly20, Lys40, and Glu93 in MELK [48].

- Hydrophobic interactions and π-π stacking.

- Absence of steric clashes.

Table 2: Exemplary Virtual Screening Hits from a Phytochemical Library Targeting MELK

| Compound ID | Source Database | Docking Score (kcal/mol) | Key Interacting Residues |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHUB000697 | PhytoHub | -12.90 | Gly20, Lys40, Cys89, Glu93 [48] |

| PHUB002010 | PhytoHub | -12.00 | N/A [48] |

| NPACT00373 | NPACT | -11.23 | N/A [48] |

| PHUB002005 | PhytoHub | -11.19 | N/A [48] |

| PHUB001739 | PhytoHub | -11.09 | N/A [48] |

Post-Screening Validation Protocols

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations

MD simulations assess the stability of protein-ligand complexes and the reliability of docking predictions in a dynamic, solvated environment.

Sample Protocol using GROMACS:

- System Setup: Place the docked complex in a cubic box (e.g., with a 0.8-1.0 nm minimum distance from the box edge) and solvate with water molecules (e.g., TIP3P model) [39].

- Neutralization: Add ions (e.g., Na⁺/Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's charge.

- Energy Minimization: Use the steepest descent algorithm to minimize the system energy and remove steric clashes.

- Equilibration: Perform equilibration in two phases: a) NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) for 100-150 ps to stabilize the temperature at 298.15 K, and b) NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) for 100-150 ps to stabilize the pressure at 1 bar [39].

- Production Run: Run an unrestrained MD simulation for a sufficient duration (typically 100-200 ns) to observe stability. Use a time step of 2 fs [48] [39].

- Trajectory Analysis: Analyze the saved trajectories for:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures the structural stability of the protein and ligand.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Identifies flexible regions of the protein.

- Hydrogen Bonds: Quantifies the persistence of key interactions over time.

- Binding Free Energy: Calculated using MM-GBSA/PBSA methods to provide a more accurate estimate of affinity [49].

Experimental Validation

Computational hits require experimental confirmation to establish bioactivity.

- In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay: Synthesize or procure top candidates and evaluate their potency against relevant breast cancer cell lines (e.g., MCF-7 for ER⁺ models, MDA-MB-231 for TNBC models) [39] [19]. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) is a standard metric. For example, a rationally designed molecule (Molecule 10) exhibited potent activity with an IC₅₀ of 0.032 µM against MCF-7 cells, significantly outperforming the positive control 5-FU (IC₅₀ = 0.45 µM) [19].

- Mechanism of Action Studies: Conduct further experiments, such as Western blotting or flow cytometry, to confirm the compound's mechanism, such as inducing apoptosis or inhibiting target phosphorylation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

A successful virtual screening campaign relies on a suite of software tools and databases.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Virtual Screening

| Category | Tool/Resource | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docking Software | AutoDock Vina [51] [41] | Protein-ligand docking & scoring | Open-source; uses iterated local search algorithm. |

| Glide (Schrödinger) [51] [49] | High-accuracy docking & VS workflow | Uses HTVS, SP, and XP modes for tiered screening. | |

| rDock [51] | Fast, open-source docking | Evolved from RiboDock; good for high-throughput. | |

| MD Software | GROMACS [39] | Molecular dynamics simulations | Open-source; highly scalable for biomolecular systems. |

| Desmond (Schrödinger) [49] | Molecular dynamics simulations | User-friendly interface with Maestro. | |

| Compound Libraries | IMPPAT 2.0 [41] | Database of Indian medicinal plants & phytochemicals | Source for 300+ screened phytochemicals. |

| PubChem [39] [41] | Public database of chemical molecules & their activities | Source for 3D compound structures (SDF format). | |

| Life Chemicals Library [50] | Commercial synthetic compound library | >13,600 drug-like molecules for anticancer screening. | |

| Analysis & Visualization | VMD [39] | Visualization of MD trajectories & 3D structures | Analyzes frames from simulations. |

| SwissADME [41] | Web tool for predicting pharmacokinetic properties | Assesses drug-likeness, GI absorption, etc. |

The following diagram synthesizes the key stages from target selection to experimental validation, providing a high-level overview of the integrated screening process.

Diagram 2: Integrated VS to Validation.

The protocols outlined herein provide a robust framework for applying virtual screening to discover novel compounds targeting breast cancer. The synergistic use of phytochemical and synthetic libraries, coupled with hierarchical computational filtering and rigorous validation, significantly enhances the probability of identifying viable lead compounds. This structured approach accelerates early-stage drug discovery while providing deep molecular insights into mechanism of action, ultimately contributing to the development of more effective and targeted breast cancer therapies.

Molecular docking serves as a cornerstone in modern structure-based drug design, enabling researchers to predict how small molecules interact with biological targets. However, a significant limitation of traditional rigid docking approaches is their treatment of proteins as static entities, which contradicts the dynamic nature of biological systems. Proteins exhibit considerable flexibility, often undergoing conformational changes upon ligand binding—a phenomenon known as induced fit [52]. This is particularly relevant for breast cancer targets like CDK4/6, HER2, and EGFR, where flexibility influences inhibitor binding and selectivity [53] [6].