Molecular Descriptors in Cancer QSAR: From Fundamentals to Clinical Applications in Drug Discovery

This comprehensive review elucidates the critical role of molecular descriptors in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) studies for anticancer drug development.

Molecular Descriptors in Cancer QSAR: From Fundamentals to Clinical Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This comprehensive review elucidates the critical role of molecular descriptors in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) studies for anticancer drug development. It explores the fundamental taxonomy of descriptors—including constitutional, topological, electronic, and geometric properties—and their calculation methods. The article details advanced QSAR methodologies integrating machine learning and hybrid descriptors for various cancers, addressing key challenges like applicability domain limitations and model overfitting. Through validation protocols and comparative analysis of descriptor performance across case studies, we demonstrate how optimized QSAR workflows accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutics for breast, colon, lung, and other cancers while reducing reliance on animal testing.

The Essential Language of Molecules: Understanding Molecular Descriptor Fundamentals

In the relentless pursuit of effective cancer therapeutics, quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) studies have emerged as a powerful computational strategy for rational drug design. At the heart of every QSAR model lies the molecular descriptor—a numerical representation that encodes key chemical information from a molecule's symbolic structure. These descriptors serve as the fundamental numerical fingerprints that allow scientists to translate chemical intuition into mathematical models capable of predicting biological activity. In cancer research, where the goal is often to discover or optimize compounds with specific antitumor properties, molecular descriptors provide the critical link between molecular structure and pharmacological effect, enabling researchers to sift through vast chemical spaces in silico before committing resources to laboratory synthesis and biological testing [1].

The transformation of molecules into numbers is not merely a convenience but a necessity for applying statistical and machine learning methods to drug discovery. By reducing complex three-dimensional molecular structures to quantitative values, descriptors facilitate the establishment of reliable correlations between chemical features and biological endpoints, such as cytotoxic potency, receptor binding affinity, or metabolic stability. This quantitative approach has become indispensable in oncology, where molecular descriptors help guide the design of novel antitumor agents against challenging targets, including recent efforts in colorectal cancer and KRAS-driven lung cancers [2] [3].

Defining and Classifying Molecular Descriptors

Fundamental Concept

A molecular descriptor is formally defined as "the final result of a logic and mathematical procedure which transforms chemical information encoded within a symbolic representation of a molecule into a useful number or the result of some standardized experiment" [4]. This definition encompasses both experimental measurements, such as log P (lipophilicity), molar refractivity, and dipole moment, as well as theoretical descriptors derived strictly from molecular structure [4]. The predictive power of any QSAR model hinges on the careful selection of descriptors that capture structural features relevant to the biological activity under investigation.

Essential Criteria for Effective Descriptors

For molecular descriptors to be practically useful in QSAR studies, they should meet several key criteria. A robust descriptor must be invariant to molecular manipulations that don't alter intrinsic structure, such as atom numbering, rotation, or translation in space. The algorithm for its calculation should be unambiguous and well-defined [4]. Beyond these foundational requirements, an ideal descriptor should have a clear structural interpretation, correlate with at least one experimental property, provide non-redundant information, and demonstrate minimal degeneracy (where different structures yield the same value) [4]. The ability to discriminate between isomers and applicability to diverse molecular classes are particularly valuable in cancer drug discovery, where subtle structural changes can dramatically alter biological activity [1].

Hierarchical Classification of Descriptors

Molecular descriptors are typically categorized according to the level of structural representation they encode, forming a hierarchy from simple atomic inventories to complex three-dimensional representations [4] [5].

Table 1: Classification of Molecular Descriptors by Dimensionality

| Descriptor Type | Structural Information Encoded | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| 0D Descriptors | Atom types, molecular weight, bond types | Molecular weight, atom counts, element types |

| 1D Descriptors | Presence/absence of functional groups, counts of specific features | Hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, ring counts, functional group counts |

| 2D Descriptors | Topological connections between atoms | Molecular connectivity indices, graph invariants, topological polar surface area |

| 3D Descriptors | Three-dimensional geometry, stereochemistry | Steric parameters, surface area/volume descriptors, 3D-MoRSE descriptors, WHIM descriptors |

| 4D Descriptors | Molecular interaction fields | GRID descriptors, CoMFA fields |

This hierarchical classification reflects increasing levels of structural complexity, with higher-dimensional descriptors generally providing more detailed—but computationally more expensive—representations of molecular structure. In cancer QSAR studies, the choice of descriptor type involves a trade-off between computational efficiency, interpretability, and informational completeness [4] [5].

Molecular Descriptors in Cancer QSAR Studies

Historical Context and Key Applications

The application of QSAR and molecular descriptors in cancer research spans decades, with early work focusing on classical approaches such as Hansch analysis and Free-Wilson analysis to relate structural features to antitumor activity [1]. These methods established the fundamental principle that a drug's distribution and interaction with biological targets are determined by properties such as lipophilicity, charge distribution, and electronic characteristics—all quantifiable through appropriate molecular descriptors [1]. For example, studies on 9-anilinoacridine antitumor agents successfully correlated structural features with both experimental antitumor activity and toxicity, demonstrating the potential of descriptors to guide the optimization of therapeutic windows in anticancer agents [1].

Advanced Descriptors in Contemporary Oncology Research

Recent advances have expanded the descriptor toolkit beyond traditional parameters to include sophisticated quantum-chemical and shape-based descriptors. In a 2025 study on anti-colorectal cancer compounds, researchers developed a high-dimensional framework using three-dimensional electron density features computed via density functional theory (DFT) [2]. These electron cloud descriptors were encoded into multi-scale representations including radial distribution functions, spherical harmonic expansions, and persistent homology, capturing molecular electronic and spatial complexity beyond conventional descriptors [2]. This approach yielded significant predictive improvements, with AUC values increasing from 0.88 with standard descriptors to 0.96 with the electron density features when using Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) models [2].

Similarly, in KRAS inhibitor development for lung cancer therapy, QSAR models incorporating topological, constitutional, geometrical, and electronic descriptors successfully predicted inhibitory potency (pIC₅₀) [3]. The genetic algorithm-optimized model identified eight optimal molecular descriptors that provided both predictive power and interpretability, enabling virtual screening of de novo designed compounds [3]. This integrative approach demonstrates how carefully selected descriptors can accelerate the discovery of targeted therapies for historically "undruggable" oncoproteins like KRAS [3].

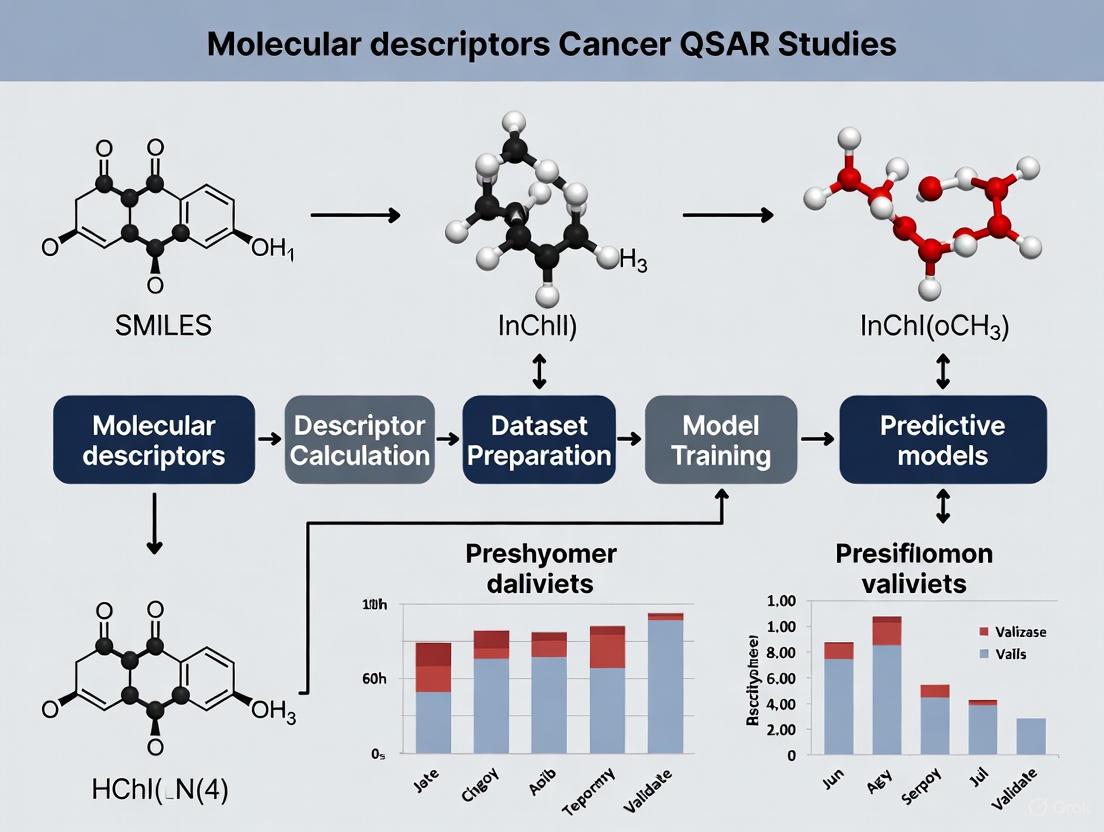

Diagram 1: QSAR Workflow in Cancer Drug Discovery. This workflow illustrates how molecular descriptors of varying complexity are calculated from chemical compounds and integrated into QSAR models for predicting biological activity in cancer research.

Practical Implementation: Calculating and Applying Descriptors

Software Tools for Descriptor Calculation

Numerous software packages exist for calculating molecular descriptors, ranging from commercial suites to open-source libraries. The selection of an appropriate tool depends on factors such as the types of descriptors needed, programming environment, budget, and specific application requirements.

Table 2: Software Tools for Molecular Descriptor Calculation

| Software | Descriptor Types | Interface | License | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| alvaDesc | 0D, Fingerprints, 3D | Python, CLI, GUI, KNIME | Proprietary | Comprehensive descriptor set, updated through 2025, multiplatform support |

| Dragon | 0D, Fingerprints, 3D | CLI, GUI, KNIME | Proprietary | Historically industry-standard, now discontinued |

| Mordred | 0D, 3D | Python, CLI | Open Source | Based on RDKit, community-maintained |

| PaDEL-Descriptor | 0D, Fingerprints, 3D | Python, CLI, GUI, KNIME | Free | Based on CDK, discontinued since 2014 |

| RDKit | 0D, Fingerprints, 3D | Python, KNIME | Open Source | Active development, cheminformatics platform |

| scikit-fingerprints | 0D, Fingerprints, 3D | Python | Open Source | Integrates with scikit-learn, updated through 2025 |

For cancer QSAR studies specifically, tools like alvaDesc and RDKit offer particularly robust solutions, providing both traditional descriptors and specialized parameters relevant to drug discovery [4]. The choice of software often influences the descriptor selection strategy, with some packages offering curated descriptor sets optimized for specific biological endpoints.

Experimental Protocol: QSAR Modeling with Molecular Descriptors

The application of molecular descriptors in cancer QSAR research follows a systematic workflow, as demonstrated in recent studies on KRAS inhibitors for lung cancer [3]:

Dataset Compilation: A curated set of 62 KRAS inhibitors with experimentally measured IC₅₀ values was retrieved from the ChEMBL database (CHEMBL4354832). IC₅₀ values were converted to pIC₅₀ using the standard transformation: pIC₅₀ = -log₁₀(IC₅₀ × 10⁻⁹) to create a more suitable scale for regression modeling [3].

Descriptor Calculation and Preprocessing: Molecular descriptors were calculated using the ChemoPy package in Python, generating topological, constitutional, geometrical, and electronic features. The resulting descriptor matrix was filtered to remove non-numeric descriptors, columns with missing values, and zero-variance descriptors. Highly correlated descriptors (Pearson's |r| > 0.95) were removed to reduce multicollinearity [3].

Feature Selection and Model Training: A Genetic Algorithm (GA) was employed to identify an optimal descriptor subset maximizing adjusted R-squared while penalizing model complexity. The fitness function was defined as: Fitness = R²adj - (k/n), where k is the number of selected descriptors and n is the number of training samples. Multiple machine learning algorithms were benchmarked, including Partial Least Squares (PLS), Random Forest (RF), and Genetic Algorithm-optimized Multiple Linear Regression (GA-MLR) [3].

Model Validation and Interpretation: Model performance was evaluated using R², RMSE, and MAE on a held-out test set. The best-performing PLS model achieved R² = 0.851 and RMSE = 0.292. Feature interpretability was enhanced through SHAP analysis and permutation-based importance measures [3].

Virtual Screening and De Novo Design: The validated QSAR model was used to screen virtually designed compounds within the model's applicability domain, identifying promising candidates like compound C9 with predicted pIC₅₀ of 8.11 for further investigation [3].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Cancer QSAR

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in QSAR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculation | alvaDesc, RDKit, Mordred, ChemoPy | Generate numerical representations from molecular structures |

| Data Sources | ChEMBL, PubChem | Provide curated biological activity data for model training |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | scikit-learn, XGBoost, Random Forest | Build predictive models linking descriptors to biological activity |

| Model Interpretation | SHAP, permutation importance | Explain model predictions and identify critical structural features |

| Chemical Design | DataWarrior, de novo evolution algorithms | Generate novel molecular structures based on QSAR predictions |

| Applicability Domain Assessment | Mahalanobis Distance, leverage | Define the chemical space where models make reliable predictions |

Emerging Trends and Advanced Descriptor Types

The evolution of molecular descriptors continues to advance cancer QSAR research, with several promising trends emerging. The integration of quantum chemical descriptors derived from density functional theory (DFT) calculations represents a significant frontier, providing detailed electronic structure information that surpasses traditional empirical descriptors [2] [6]. As demonstrated in anti-colorectal cancer studies, 3D electron cloud descriptors capture electronic and spatial complexity through radial distribution functions, spherical harmonic expansions, and persistent homology, leading to substantial improvements in predictive accuracy [2].

Another important development is the strategic combination of descriptor types to leverage their complementary strengths. Recent studies show that integrating conventional 1D/2D descriptors with advanced 3D electronic features produces more robust QSAR models than either approach alone [2]. This hybrid strategy balances computational efficiency with detailed molecular representation, particularly valuable for modeling complex biological interactions like protein-ligand binding in oncology targets.

Diagram 2: Molecular Descriptor Integration in Cancer QSAR. This diagram illustrates how different classes of molecular descriptors feed into various machine learning algorithms to address specific cancer drug discovery challenges.

Molecular descriptors serve as the indispensable numerical fingerprints that bridge chemical structure and biological activity in cancer QSAR studies. From simple constitutional counts to sophisticated 3D electron cloud representations, these quantitative encodings enable researchers to build predictive models that accelerate oncology drug discovery. As descriptor technology continues to evolve—incorporating increasingly detailed electronic, topological, and quantum-chemical information—its impact on rational cancer therapeutic design will only grow. Despite challenges in computational cost and model interpretability, the strategic application of molecular descriptors remains fundamental to advancing personalized cancer treatment through computational means. The ongoing refinement of these numerical representations promises to unlock new opportunities for targeting historically intractable oncogenic drivers, ultimately contributing to more effective and selective cancer therapies.

In the realm of cancer drug discovery, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) studies serve as pivotal computational tools that mathematically correlate the biological activity of chemical compounds with their molecular structure. The foundational premise of QSAR modeling posits that the variance in biological properties of molecules, such as their cytotoxicity against specific cancer cell lines, can be correlated with numerical representations derived from their chemical structures. These numerical representations, known as molecular descriptors, are quantitative parameters that encode specific aspects of a molecule's structure and properties, thereby enabling the prediction of biological activity for novel compounds without the immediate need for costly and time-consuming laboratory synthesis and biological testing. The application of QSAR modeling in oncology research has gained substantial traction, as evidenced by recent studies focusing on various cancer types, including melanoma, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and leukemia [7] [8] [9].

The taxonomy of molecular descriptors is systematically categorized based on the structural and physicochemical information they encode. This classification encompasses constitutional, topological, electronic, geometric, and thermodynamic descriptors, each providing unique insights into molecular characteristics relevant to biological activity. In cancer research, the strategic selection and application of these descriptors facilitate the understanding of how chemical structures influence anti-cancer efficacy, thereby guiding the rational design of novel therapeutic agents. For instance, recent QSAR studies on anti-melanoma compounds utilized a combination of descriptor types to develop models with significant predictive power for cytotoxicity against SK-MEL-2 and SK-MEL-5 cell lines [7] [9]. Similarly, research on breast cancer therapeutics has leveraged topological and electronic descriptors to model drug behavior and properties [10] [11]. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical examination of the five core descriptor types, detailing their theoretical foundations, computation methodologies, and specific applications within cancer QSAR modeling, with particular emphasis on experimental protocols and data presentation frameworks utilized in contemporary research.

Constitutional Descriptors

Definition and Significance

Constitutional descriptors represent the most fundamental class of molecular descriptors, derived directly from the molecular formula without consideration of molecular geometry or connectivity. These descriptors provide basic, yet highly informative, quantitative measures of a compound's atomic composition and overall molecular framework. In cancer QSAR studies, constitutional descriptors serve as primary filters for compound screening, offering initial insights into molecular size, composition, and bulk properties that may influence drug-likeness, bioavailability, and general trends in cytotoxic activity. Their computation is straightforward and does not require molecular geometry optimization, making them computationally inexpensive and readily obtainable for large compound libraries in virtual screening campaigns aimed at identifying novel anti-cancer agents.

Key Constitutional Descriptors and Their Computation

The calculation of constitutional descriptors involves counting specific atomic types or molecular features within a chemical structure. Representative constitutional descriptors include molecular weight (MW), number of specific atom types (e.g., carbon, oxygen, nitrogen), number of bonds, number of rings, and number of functional groups. These descriptors are typically generated from molecular structure files using specialized software such as PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon, and ChemDes [7] [8].

Table 1: Key Constitutional Descriptors in Cancer QSAR Studies

| Descriptor Name | Mathematical Definition | Interpretation in Cancer QSAR | Exemplary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Weight (MW) | Sum of atomic masses of all atoms in molecule | Related to membrane permeability and bioavailability; often correlated with cytotoxic activity | Identified as key descriptor in ARC-111 analogues QSAR for RPMI8402 tumor cells [12] |

| Number of Heavy Atoms | Count of all atoms except hydrogen | Indicator of molecular size and complexity; influences drug-receptor interactions | Used in GA-MLRA model for anti-leukemia compounds against MOLT-4 and P388 cell lines [8] |

| Number of Rotatable Bonds | Count of single bonds excluding amide C-N bonds | Measure of molecular flexibility; related to entropy changes upon binding | Feature in combinatorial QSAR models for breast cancer drug pairs [13] |

| Number of H-Bond Donors/Acceptors | Count of O-H and N-H bonds (donors); N and O atoms with lone pairs (acceptors) | Predicts solubility and membrane penetration; critical for oral bioavailability of anti-cancer drugs | Component of descriptor sets for SK-MEL-5 melanoma cell line cytotoxicity prediction [9] |

Experimental Protocol for Constitutional Descriptor Calculation

The standard workflow for computing constitutional descriptors in cancer QSAR studies involves sequential steps:

- Structure Input: Provide molecular structures in standardized format (e.g., SMILES, SDF, MOL2) ensuring proper valence and explicit hydrogen treatment. In a study on 1,2,3-triazole-pyrimidine derivatives against gastric cancer cells, 2D structures were converted to 3D and optimized using Density Functional Theory (DFT/B3LYP) with 6-31G basis set [14].

- Descriptor Generation: Utilize computational tools such as PaDEL-Descriptor, which computes 1D and 2D descriptors directly from molecular structure, or Dragon software, which offers comprehensive descriptor calculations including constitutional descriptors [7] [8] [9].

- Descriptor Preprocessing: Apply filtering to remove constant or near-constant descriptors, handle missing values, and reduce redundancy through correlation analysis. As implemented in a melanoma QSAR study, this step involves removing variables with constant or near-constant values using a threshold (e.g., 0.1%), eliminating features with missing values, and excluding highly correlated descriptors to minimize multicollinearity [9].

Topological Descriptors

Theoretical Foundations

Topological descriptors, derived from chemical graph theory, represent molecular structures as mathematical graphs where atoms correspond to vertices and bonds to edges. These descriptors encode information about molecular connectivity, branching, and shape, providing insights into structural aspects that influence biological activity without requiring 3D coordinate information. In cancer QSAR, topological indices have demonstrated significant utility in predicting cytotoxic activity, physicochemical properties, and absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) parameters of anti-cancer compounds. Recent advances have introduced sophisticated topological indices such as entire neighborhood indices and resolving topological indices, which capture more complex structural patterns and atomic environments relevant to drug-receptor interactions [10] [11].

The application of topological descriptors in cancer research spans various malignancies. For breast cancer drugs, entire neighborhood topological indices have shown strong correlations with physicochemical properties, enabling predictive modeling of molar volume, polarizability, and molar refractivity [10]. Similarly, in anti-leukemia drug discovery, topological descriptors like the conventional bond order ID number (piPC1) and the largest absolute eigenvalue of Burden modified matrix (SpMax7_Bhm) were identified as significant predictors of activity against MOLT-4 and P388 cell lines [8]. The computational efficiency of topological descriptors makes them particularly valuable for high-throughput virtual screening of large chemical libraries in early-stage anti-cancer drug development.

Key Topological Indices and Their Applications

Topological indices quantify specific aspects of molecular structure based on graph-theoretical principles. These indices are broadly categorized into degree-based, distance-based, and information-theoretic indices, each capturing distinct topological features.

Table 2: Key Topological Descriptors in Cancer QSAR Studies

| Descriptor Category | Representative Indices | Mathematical Formulation | Cancer QSAR Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degree-Based Indices | Zagreb Indices (M₁, M₂), Randić Index | M₁ = Σ[du]², M₂ = Σ(du·dv) | Used in breast cancer drug QSPR studies for predicting polar surface area and surface tension [11] |

| Distance-Based Indices | Wiener Index, Balaban Index | J = [m/(μ+1)] Σ(di·dj)^(-1/2) | Applied in QSAR models of ARC-111 analogues targeting topoisomerase I [12] |

| Entire Neighborhood Indices | First and Second Entire Neighborhood | FNε = Σδ(x)², SNε = Σ[δ(x)·δ(y)]^(-1/2) | Correlated with physicochemical properties of 16 breast cancer drugs [10] |

| Information-Theoretic Indices | Molecular Connectivity Index | Based on Shannon's entropy applied to graph elements | Component of descriptor sets for SK-MEL-5 melanoma cytotoxicity prediction [9] |

Computational Methodology

The calculation of topological descriptors follows a systematic protocol implemented in various software packages:

- Molecular Graph Representation: Convert the chemical structure to a hydrogen-suppressed graph where vertices represent non-hydrogen atoms and edges represent chemical bonds. In studies of breast cancer drugs, molecular graphs were constructed based on their chemical molecular structures [10].

- Graph Invariant Computation: Calculate topological indices based on the graph representation using algorithms for degree calculation, path enumeration, and distance matrix computation. Software tools such as Dragon, PaDEL-Descriptor, and specialized MATLAB or Python scripts are commonly employed. For instance, in the development of a combinational QSAR model for breast cancer, PaDEL-Descriptor was used to compute topological descriptors for anchor and library drugs [13].

- Descriptor Validation: Ensure computed indices satisfy mathematical properties and are chemically meaningful. This includes checking for degeneracy (different structures yielding same index value) and correlation with established descriptors. In high-dimensional descriptor selection for ARC-111 analogues, the Worst Descriptor Elimination Multi-roundly (WDEM) and High-dimensional Descriptor Selection Nonlinearly (HDSN) methods were applied to select the most relevant topological descriptors from thousands of candidates [12].

Electronic Descriptors

Theoretical Background

Electronic descriptors quantify the electronic distribution and reactivity characteristics of molecules, which directly influence their interactions with biological targets through electrostatic forces, charge transfer, and hydrogen bonding. In cancer QSAR, electronic descriptors are particularly valuable for understanding drug-receptor interactions, as they capture aspects of molecular recognition and binding affinity. These descriptors are typically derived from quantum chemical calculations using methods such as Density Functional Theory (DFT), which provides accurate electronic structure information at reasonable computational cost. Recent advances in electronic descriptor development include 3D electron cloud descriptors derived from DFT calculations, which have shown enhanced predictive power in QSAR models for anti-colorectal cancer compounds [2].

Electronic properties play a crucial role in the mechanism of action of many anti-cancer drugs. For instance, in QSAR studies of 1,2,3-triazole-pyrimidine derivatives against human gastric cancer cells (MGC-803), electronic descriptors computed at the B3LYP/6-31G level successfully predicted IC₅₀ values and provided insights into ligand-receptor interactions [14]. Similarly, in melanoma research, electronic descriptors contributed to QSAR models predicting cytotoxicity against SK-MEL-2 cells, with subsequent molecular docking studies elucidating binding modes with the V600E-BRAF protein [7]. The integration of electronic descriptors with other descriptor types has become standard practice in comprehensive cancer QSAR modeling, enabling more accurate prediction of anti-cancer activity and facilitating rational drug design.

Key Electronic Descriptors

Electronic descriptors encompass a range of molecular properties derived from quantum mechanical calculations, each providing unique insights into electronic structure and reactivity.

Table 3: Key Electronic Descriptors in Cancer QSAR Studies

| Descriptor Category | Representative Descriptors | Computational Method | Biological Significance in Cancer QSAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Orbital Energy Descriptors | HOMO Energy, LUMO Energy, HOMO-LUMO Gap | DFT/B3LYP/6-31G | Predicts charge transfer interactions and chemical reactivity with cancer target proteins [14] |

| Charge-Based Descriptors | Partial Atomic Charges, Dipole Moment, Molecular Polarizability | DFT/Mulliken or Natural Population Analysis | Quantifies electrostatic interactions with receptor sites; dipole moment identified as key descriptor for ARC-111 analogues [12] |

| Reactivity Descriptors | Electrophilicity Index, Hardness, Softness | DFT-based conceptual DFT | Correlates with cytotoxic potency against various cancer cell lines [14] |

| 3D Electron Cloud Descriptors | Radial Distribution Functions, Spherical Harmonic Expansions | DFT followed by 3D point cloud encoding | Enhanced prediction of anti-colorectal cancer activity; AUC increased from 0.88 to 0.96 [2] |

Experimental Protocol for Electronic Descriptor Calculation

The computation of electronic descriptors requires rigorous quantum chemical calculations following a standardized protocol:

- Molecular Geometry Optimization: Begin with initial molecular structure and perform geometry optimization using quantum chemical methods (typically DFT with B3LYP functional and 6-31G* or 6-31G* basis set) to obtain the minimum energy conformation. In a study on anti-melanoma compounds, molecular optimization was set at the ground state employing DFT/B3LYP with 6-31G basis set [7].

- Wavefunction Calculation: Perform single-point energy calculation on the optimized geometry to obtain the wavefunction and electron density distribution. For enhanced electronic description, 3D electron cloud descriptors can be computed by converting electron densities to 3D point clouds and encoding them into multi-scale descriptors including radial distribution functions, spherical harmonic expansions, and point feature histograms [2].

- Electronic Property Extraction: Calculate electronic descriptors from the wavefunction, including frontier molecular orbital energies (HOMO, LUMO), partial atomic charges, dipole moment, and molecular electrostatic potential. In the QSAR study of 1,2,3-triazole-pyrimidine derivatives, these descriptors were computed using B3LYP/6-31G and correlated with observed bioactivities against MGC-803 gastric cancer cells [14].

- Descriptor Validation: Verify the consistency of computed properties through frequency calculations (confirming no imaginary frequencies for optimized structures) and comparison with experimental data when available.

Geometric and Thermodynamic Descriptors

Geometric Descriptors

Geometric descriptors encode information about the three-dimensional shape and size of molecules, capturing steric features that significantly influence molecular recognition and binding to biological targets. Unlike topological descriptors that consider only connectivity, geometric descriptors require 3D molecular coordinates and are therefore conformation-dependent. In cancer QSAR, geometric descriptors help elucidate steric complementarity between drugs and their target receptors, providing insights into binding affinity and selectivity. Recent research in anti-colorectal cancer compound modeling has demonstrated that geometric descriptors derived from 3D electron cloud representations significantly enhance predictive performance when combined with electronic descriptors [2].

Key geometric descriptors include molecular surface area, solvent-accessible surface area, molecular volume, moments of inertia, and asphericity indices. These descriptors are particularly relevant in cancer drug discovery where shape complementarity between ligand and receptor often determines binding specificity. In breast cancer drug studies, geometric descriptors have been employed to predict physicochemical properties such as molar volume and polar surface area, which influence absorption and distribution characteristics [10] [11]. The computation of geometric descriptors typically follows molecular geometry optimization using quantum chemical methods or molecular mechanics force fields, ensuring accurate representation of molecular shape and dimensions.

Thermodynamic Descriptors

Thermodynamic descriptors quantify the energy-related properties and stability characteristics of molecules, providing insights into the energetics of drug-receptor interactions and metabolic stability. These descriptors are particularly relevant in cancer drug discovery, where compound stability and interaction energetics directly influence efficacy and pharmacokinetics. Key thermodynamic descriptors include heat of formation (ΔHf), free energy of solvation, lattice energy, and vaporization enthalpy. In QSAR modeling of ARC-111 analogues for RPMI8402 tumor cells, the heat of formation (ΔHf₀) was identified as one of six key descriptors responsible for predicting antitumor activity [12].

The calculation of thermodynamic descriptors typically involves quantum chemical computations or quantitative structure-property relationship (QSPR) estimations. For instance, in the development of QSAR models for anti-melanoma compounds, thermodynamic descriptors were computed alongside electronic and topological descriptors to comprehensively characterize molecular properties relevant to cytotoxicity [7] [9]. Thermodynamic parameters also play a crucial role in understanding the metabolic stability and degradation pathways of anti-cancer compounds, providing valuable insights for lead optimization in drug discovery programs.

Computational Framework

The calculation of geometric and thermodynamic descriptors follows an integrated computational protocol:

- 3D Structure Generation: Convert 2D structures to 3D conformations using tools such as Open Babel, CORINA, or molecular modeling software. In studies of anti-melanoma compounds, 2D structures were converted to 3D using Spartan software followed by geometry optimization [7].

- Conformational Analysis: Perform systematic or stochastic conformational search to identify low-energy conformers, selecting the global minimum energy conformation for descriptor calculation.

- Geometry Optimization: Refine the 3D structure using quantum chemical methods (e.g., DFT with appropriate basis set) or molecular mechanics force fields to obtain accurate molecular geometries.

- Descriptor Computation: Calculate geometric descriptors (volume, surface area, shape parameters) and thermodynamic descriptors (formation enthalpy, free energies) using computational chemistry software such as Gaussian, GAMESS, or specialized descriptor calculation tools.

Table 4: Geometric and Thermodynamic Descriptors in Cancer QSAR

| Descriptor Type | Specific Descriptors | Computational Approach | Cancer QSAR Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometric Descriptors | Molecular Volume, Surface Area, Radius of Gyration | DFT-optimized structures followed by surface calculation | Predicts transport properties and binding cavity compatibility in cancer targets |

| Shape Descriptors | Principal Moments of Inertia, Asphericity, Eccentricity | Coordinate diagonalization of inertia tensor | Correlates with specificity for cancer enzyme active sites |

| Thermodynamic Descriptors | Heat of Formation (ΔHf), Free Energy of Solvation | DFT computation or group contribution methods | ΔHf identified as key descriptor in ARC-111 analogues QSAR [12] |

| Surface Property Descriptors | Polar Surface Area (PSA), Molecular Polarizability | Surface analysis of optimized geometries | Predicts membrane permeability and bioavailability of breast cancer drugs [11] |

Integrated QSAR Modeling in Cancer Research

Descriptor Selection and Model Building

The integration of multiple descriptor types into comprehensive QSAR models represents the state-of-the-art in cancer drug discovery. Descriptor selection is a critical step that identifies the most relevant molecular features for predicting anti-cancer activity while avoiding overfitting. Advanced machine learning techniques coupled with robust validation protocols have significantly enhanced the predictive power and reliability of QSAR models in oncology research. For instance, in developing QSAR models for anti-melanoma compounds, researchers employed genetic algorithms for descriptor selection and multiple linear regression for model building, achieving R² values of 0.902 for MOLT-4 and 0.904 for P388 leukemia cell lines [8].

Recent approaches to descriptor selection and model building include:

- High-Dimensional Descriptor Selection: Techniques such as the Worst Descriptor Elimination Multi-roundly (WDEM) and High-dimensional Descriptor Selection Nonlinearly (HDSN) methods enable efficient selection of relevant descriptors from thousands of candidates. In a study of ARC-111 analogues, these methods reduced descriptors from 2,923 to 7-11 highly predictive features while maintaining model accuracy [12].

- Machine Learning Integration: Advanced algorithms including Random Forest, Support Vector Machines, and Deep Neural Networks have been successfully applied to QSAR modeling for various cancers. In combinatorial QSAR for breast cancer, Deep Neural Networks achieved an impressive R² of 0.94 for predicting combination drug activity [13].

- Multi-Descriptor Integration: Combining descriptor types (constitutional, topological, electronic, geometric, thermodynamic) provides comprehensive molecular representation. For anti-colorectal cancer compounds, integrating 3D electron cloud descriptors with conventional 1D/2D descriptors significantly enhanced model accuracy [2].

Validation and Applicability Domain Assessment

Rigorous model validation is essential to ensure the reliability and predictive power of QSAR models in cancer research. The validation process assesses both internal consistency and external predictivity, while applicability domain analysis determines the scope and limitations of the model. Standard validation protocols include:

- Internal Validation: Assess model performance using cross-validation techniques such as leave-one-out (LOO) or k-fold cross-validation. For example, in QSAR modeling of anti-melanoma compounds, the best-generated model based on multiple linear regression showed good quality of fits (R² = 0.864, Q²cv = 0.799) [7].

- External Validation: Evaluate the model on an independent test set not used in model building. In the melanoma QSAR study, the model's predictive ability was determined by a test set of twenty-two compounds, with R²pred = 0.706 [7].

- Y-Scrambling/Randomization: Confirm the non-random character of the model by permuting activity values while keeping descriptors unchanged; significantly worse performance in scrambled models indicates a robust QSAR model [8] [9].

- Applicability Domain Analysis: Define the chemical space where the model can make reliable predictions using methods such as leverage approach, distance-based methods, or probability density distribution. This ensures that predictions are only made for compounds structurally similar to the training set [9].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Essential Computational Tools for Descriptor Calculation and QSAR Modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Tools | Primary Function | Application in Cancer QSAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculation | PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon, ChemDes | Compute 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors | Used to generate descriptors for anti-leukemia compounds [8] and breast cancer drug combinations [13] |

| Quantum Chemical Computation | Gaussian, GAMESS, Spartan | Perform DFT calculations for electronic descriptors | Employed for geometry optimization and electronic property calculation for anti-melanoma compounds [7] and gastric cancer inhibitors [14] |

| Machine Learning Platforms | Scikit-learn, Weka, TensorFlow | Implement ML algorithms for QSAR model development | Utilized for developing combinatorial QSAR models for breast cancer using DNN and other algorithms [13] |

| Molecular Visualization & Analysis | Discovery Studio Visualizer, PyMOL, ChemAxon | Structure standardization, visualization, and analysis | Applied in SK-MEL-5 melanoma cell line QSAR studies for structure standardization [9] |

The strategic application of molecular descriptor taxonomy in cancer QSAR studies represents a powerful paradigm in modern anti-cancer drug discovery. Constitutional, topological, electronic, geometric, and thermodynamic descriptors collectively provide a comprehensive representation of molecular structure and properties, enabling the development of robust predictive models for anti-cancer activity. The integration of these descriptor classes with advanced machine learning algorithms has significantly enhanced the accuracy and applicability of QSAR models across various cancer types, from melanoma and breast cancer to colorectal cancer and leukemia.

Future directions in descriptor development for cancer QSAR include the refinement of 3D electron cloud descriptors [2], the expansion of entire neighborhood topological indices [10] [11], and the implementation of multi-scale descriptor frameworks that integrate molecular, cellular, and tissue-level features. As QSAR methodologies continue to evolve, incorporating increasingly sophisticated descriptors and modeling techniques, their role in accelerating anti-cancer drug discovery and optimizing therapeutic agents will become increasingly indispensable. The systematic taxonomy and application of molecular descriptors outlined in this technical guide provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for leveraging these powerful computational tools in the ongoing battle against cancer.

In the field of anticancer drug discovery, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling serves as a fundamental computational approach that mathematically links a chemical compound's molecular structure to its biological activity against cancer targets [15]. These models operate on the principle that structural variations systematically influence biological activity, enabling researchers to predict the anticancer potential of novel compounds before costly and time-consuming laboratory synthesis and biological testing [15]. The process transforms chemical structures into numerical representations known as molecular descriptors, which quantify structural, physicochemical, and electronic properties that influence biological activity [16] [15]. In cancer research specifically, QSAR has demonstrated significant utility in optimizing lead compounds against various cancer types, including breast cancer (MCF-7), liver cancer (HepG2), lung cancer, and colon cancer, as evidenced by recent studies on flavones, FGFR-1 inhibitors, KRAS inhibitors, and chalcone derivatives [17] [18] [3].

The critical importance of molecular descriptors extends beyond mere prediction—they provide mechanistic insights into the structural features that enhance or diminish anticancer activity. For instance, SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis in machine learning-driven QSAR models can highlight key molecular descriptors influencing anticancer activity, thereby guiding the rational design of more potent and selective anticancer agents [17]. As the field advances, the selection of appropriate descriptor calculation tools has become increasingly crucial for developing robust, interpretable, and predictive QSAR models in cancer drug discovery campaigns.

Comparative Analysis of Molecular Descriptor Software

Several software packages have been developed to calculate molecular descriptors, each with distinct capabilities, limitations, and applications in cancer QSAR studies. The four most prominent tools—PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon, RDKit, and Mordred—vary significantly in their descriptor coverage, computational efficiency, licensing constraints, and ease of integration into QSAR workflows. Understanding these differences is essential for researchers to select the most appropriate tool for their specific cancer research applications.

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Major Molecular Descriptor Calculation Software

| Software | Descriptor Count | Key Features | Licensing | Interface Options | Programming Language |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PaDEL-Descriptor | 1875 descriptors (1444 1D/2D + 431 3D) + 12 fingerprint types [19] | Graphical User Interface (GUI), command-line, KNIME, RapidMiner extensions [19] | Free for all uses [19] | GUI, CLI, KNIME, RapidMiner [19] | Java [19] |

| Dragon | 5270 molecular descriptors [20] | Extensive descriptor coverage; widely used in industry [16] | Proprietary shareware [16] | GUI, CLI, web (e-Dragon), KNIME [16] | Not specified |

| RDKit | Not explicitly quantified (cheminformatics library) | Broad cheminformatics functionality beyond descriptor calculation [16] | Open-source [16] | Python, C++, Java, C# [16] | C++ with multi-language bindings |

| Mordred | >1800 descriptors (2D & 3D) [16] | High calculation speed; automated molecular preprocessing [16] | BSD license (commercial & non-commercial use) [16] | Python package, CLI, web application [16] | Python (with RDKit and NumPy dependencies) [16] |

Performance and Technical Considerations

Beyond the basic features and descriptor counts, performance metrics and technical implementation details significantly influence software selection for cancer QSAR projects. Computational efficiency becomes particularly important when screening large virtual compound libraries against cancer targets. According to independent benchmarking, Mordred demonstrates notably faster calculation speeds, reported to be at least twice as fast as PaDEL-Descriptor and capable of calculating descriptors for large molecules like maitotoxin (molecular weight 3422) in approximately 1.2 seconds [16]. This performance advantage can substantially accelerate QSAR model development cycles in cancer drug discovery.

The dimensionality of descriptors represents another crucial consideration. While 3D descriptors can provide valuable chemical information about molecules, they require geometric optimization and may vary between 3D conformers, potentially affecting reproducibility [20]. Consequently, some researchers prefer using only 2D descriptors in their cancer QSAR studies to ensure consistency and avoid conformational complexities [20]. Mordred supports both 2D and 3D descriptor calculations, offering flexibility for different research needs [16].

Installation and dependency management vary considerably across tools. Mordred was specifically designed to simplify installation, with most dependencies coded in pure Python (except for RDKit and NumPy), enabling installation with a single command [16]. In contrast, tools like Cinfony require multiple manually installed dependencies, complicating the setup process [16]. Dragon's proprietary nature may present licensing constraints that complicate publication of constructed QSAR models [16], whereas open-source tools like Mordred (BSD license) and PaDEL-Descriptor (free for all uses) offer greater freedom for academic and commercial applications [16] [19].

Table 2: Performance and Technical Specifications of Descriptor Software

| Software | Calculation Speed | Platform Support | Dependencies | Preprocessing Capabilities | Automated Testing |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PaDEL-Descriptor | Slower compared to Mordred [16] | Cross-platform (Java-based) [19] | Java JRE 6+ [19] | Salt removal, aromaticity detection, tautomer standardization [19] | Not specified |

| Dragon | Not explicitly benchmarked | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified |

| RDKit | Not explicitly benchmarked | Cross-platform | Python, Boost, NumPy (for Python bindings) | Comprehensive cheminformatics functions | Not specified |

| Mordred | At least 2x faster than PaDEL-Descriptor [16] | Windows, Linux, macOS [16] | RDKit, NumPy, enum34, networkx, six, tqdm [16] | Automated H addition/removal, Kekulization, aromaticity detection [16] | All descriptors automatically tested [16] |

Implementation in Cancer QSAR Workflows

Standard QSAR Protocol for Cancer Research

The implementation of molecular descriptor calculators follows a systematic QSAR workflow that has been successfully applied to various cancer targets. The generalized protocol consists of several standardized steps that ensure the development of robust and predictive models for anticancer activity prediction.

The QSAR workflow begins with dataset curation, where compounds with known anticancer activities are collected from databases like ChEMBL [18] [3] or literature sources [21]. For example, in a study on KRAS inhibitors for lung cancer therapy, researchers retrieved 62 inhibitors from the ChEMBL database (CHEMBL4354832) with experimentally measured IC₅₀ values [3]. The biological activities are typically converted to pIC₅₀ values (pIC₅₀ = -log₁₀(IC₅₀ × 10⁻⁹)) to provide a more suitable scale for regression modeling [3].

Following dataset preparation, molecular descriptor calculation is performed using the selected software tools. In a comparative study on biodegradability prediction (with implications for cancer drug metabolism studies), researchers used Mordred to calculate 1,613 two-dimensional descriptors, excluding 3D descriptors to avoid complex and non-reproducible optimizations [20]. The calculated descriptors then undergo preprocessing and feature selection to reduce dimensionality and mitigate multicollinearity issues. Techniques include removing descriptors with missing values, zero variance, or high correlation (Pearson's |r| > 0.95), followed by selection of the most informative features using methods like genetic algorithms [3].

The subsequent model building phase employs various machine learning algorithms. For instance, in a study on flavone anticancer activity, researchers compared random forest (RF), extreme gradient boosting, and artificial neural network (ANN) models, finding that the RF model exhibited superior performance (R² = 0.820 for MCF-7 and 0.835 for HepG2) [17]. Finally, the model validation step assesses predictive performance using internal cross-validation and external test sets, with techniques like leave-one-out cross-validation and validation using holdout test compounds [17] [15].

Case Studies in Cancer Drug Discovery

The practical application of descriptor calculation tools in cancer QSAR studies is illustrated through several recent research examples:

FGFR-1 Inhibitors for Cancer Therapy: Researchers developed a QSAR model for Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 1 (FGFR-1) inhibitors using a dataset of 1,779 compounds from ChEMBL. Molecular descriptors were calculated using AlvaDesc software, and feature selection techniques refined the descriptor set. The resulting model demonstrated strong predictive performance (R² = 0.7869 for training, 0.7413 for test set) and was validated through in vitro assays on A549 (lung cancer) and MCF-7 (breast cancer) cell lines [18].

KRAS Inhibitors for Lung Cancer: In this study, molecular descriptors for 62 KRAS inhibitors were computed using Chemopy. After descriptor normalization and dimensionality reduction, five machine learning algorithms were applied, with partial least squares (PLS) exhibiting the best predictive performance (R² = 0.851). Virtual screening of 56 de novo designed compounds within the model's applicability domain identified a promising hit (compound C9) with predicted pIC₅₀ of 8.11 [3].

Anti-Colon Cancer Chalcone Analogs: QSAR modeling was applied to predict the anti-colon cancer activity (against HT-29) of 193 chalcone derivatives using the Monte Carlo method based on optimal descriptors combining SMILES notation and hydrogen-suppressed molecular graphs. The best-performing model achieved R²_validation = 0.90, successfully predicting pIC₅₀ values of new chalcone derivatives from the ChEMBL database [21].

1,3-Diphenyl-1H-pyrazoles against Breast Cancer: Researchers investigated anti-proliferative properties of pyrazole derivatives against breast cancer cells (MCF-7) using QSAR modeling. PaDEL-Descriptor was used to calculate molecular descriptors, and a validated penta-parametric QSAR model (R²train = 0.896; Q²CV = 0.816; R²test = 0.703) highlighted the predominant influence of molecular size, shape, and symmetry on cytotoxic effects [22].

Successful implementation of cancer QSAR studies requires a comprehensive suite of computational tools and resources that extend beyond descriptor calculation software. The following table summarizes essential components of the modern computational chemist's toolkit for anticancer QSAR modeling.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Cancer QSAR

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Application in Cancer QSAR | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculators | PaDEL-Descriptor, Mordred, Dragon, RDKit, ChemoPy [16] [15] [20] | Convert chemical structures to numerical descriptors | Generate 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors and fingerprints |

| Machine Learning Libraries | scikit-learn [20], XGBoost [3], iml (for SHAP) [3] | Build predictive QSAR models | Implementation of RF, SVM, PLS, ANN, and other algorithms |

| Cheminformatics Libraries | RDKit [16] [20], CDK (via PaDEL) [19] | Molecular standardization, manipulation, and analysis | Handle SMILES parsing, structure optimization, and molecular operations |

| Data Sources | ChEMBL [18] [3], PubChem [20] [22] | Source bioactive compounds against cancer targets | Curated bioactivity data for diverse molecular targets |

| Model Interpretation Tools | SHAP [17] [3], permutation importance [3] | Identify key descriptors influencing anticancer activity | Explain machine learning model predictions and descriptor contributions |

| Visualization Software | DataWarrior [3], BIOVIA Draw [21] | Structure depiction and chemical space visualization | Draw chemical structures and analyze chemical libraries |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Methodologies

Integration with Structure-Based Methods

Modern cancer drug discovery increasingly integrates QSAR modeling with structure-based approaches such as molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations. This integrated strategy provides a more comprehensive understanding of compound activity by combining ligand-based and structure-based perspectives. For example, in the study of FGFR-1 inhibitors, researchers complemented QSAR modeling with molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulations to validate stable interactions between the compounds and FGFR-1 [18]. Similarly, in the investigation of anti-proliferative pyrazole derivatives, QSAR modeling was combined with molecular docking, molecular mechanics generalized born surface area (MM/GBSA) calculations, and molecular dynamics simulations to study binding interactions and thermodynamic stability [22].

This multi-faceted approach enhances the reliability of predictions and provides deeper insights into the structural basis of anticancer activity. The synergy between descriptor-based QSAR models and structural biology techniques creates a powerful framework for rational anticancer drug design, enabling researchers to optimize both the physicochemical properties and target binding characteristics of lead compounds.

Graph Convolutional Networks as an Alternative Approach

While traditional QSAR models rely on pre-calculated molecular descriptors, graph convolutional networks (GCNs) represent an emerging alternative that directly processes molecular graphs without requiring explicit descriptor calculation [20]. In this approach, atoms and bonds are naturally mapped to nodes and edges in a graph, with GCNs automatically learning relevant features during model training.

A comparative study on biodegradability prediction (relevant to cancer drug metabolism) demonstrated that GCN models are more straightforward to implement and more stable than conventional QSAR approaches, with specificity and sensitivity values nearly identical without requiring specific descriptor selection [20]. Although GCNs have not yet seen widespread adoption in cancer QSAR studies, they represent a promising direction that may complement or potentially replace conventional descriptor-based approaches in the future, particularly as deep learning methodologies continue to advance.

Molecular descriptor calculation tools including PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon, RDKit, and Mordred play an indispensable role in modern cancer QSAR research, enabling the transformation of chemical structures into numerical descriptors that can be correlated with anticancer activity. Each software offers distinct advantages: PaDEL-Descriptor provides a comprehensive descriptor set with multiple interfaces; Dragon offers extensive descriptor coverage; RDKit delivers broad cheminformatics functionality; and Mordred combines high calculation speed with convenient installation and lax licensing constraints.

The successful application of these tools in cancer QSAR studies—from flavones and chalcones to FGFR-1 and KRAS inhibitors—demonstrates their critical importance in accelerating anticancer drug discovery. As the field evolves, the integration of descriptor-based QSAR modeling with structure-based methods and emerging deep learning approaches like graph convolutional networks will likely enhance predictive capabilities further. The continued development and refinement of molecular descriptor calculation software will remain fundamental to advancing computational drug discovery against challenging cancer targets, ultimately contributing to the development of more effective and selective anticancer therapies.

The journey from Hammett constants to modern 3D descriptors represents a revolutionary pathway in computational chemistry and drug design, particularly within cancer Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) studies. This evolution mirrors the pharmaceutical industry's transition from qualitative observations to quantitative, prediction-driven science. QSAR modeling formally began in the early 1960s with the works of Hansch and Fujita and Free and Wilson, who extended Hammett's foundational principles [23]. These methodological advances established the core paradigm of QSAR: using mathematical models to correlate chemical structures with biological activities to predict the behavior of new compounds [23].

In the specific context of oncology, this evolution has proven particularly valuable. The development of cancer therapeutics faces significant challenges, including limitations of traditional drug development models, inherent flaws of single-target drugs, and the overwhelming complexity of tumor mechanisms [24]. Modern cancer drug development now integrates multiple technological pillars, with QSAR approaches serving as a crucial component alongside omics technologies, bioinformatics, network pharmacology, and molecular dynamics simulation [24]. This multidisciplinary approach has significantly shortened drug development cycles and promoted more precise, personalized cancer therapies [24].

The Hammett Era: Foundation in Electronic Effects

The Original Hammett Equation

The Hammett equation, developed and published by Louis Plack Hammett in 1937, represents the pioneering linear free-energy relationship in physical organic chemistry [25]. It quantitatively relates reaction rates and equilibrium constants for reactions involving benzoic acid derivatives with meta- and para-substituents through a simple yet powerful mathematical formulation:

In this equation, K is the equilibrium constant for a substituted compound, K₀ is the reference constant for unsubstituted benzoic acid, σ is the substituent constant specific to each functional group, and ρ is the reaction constant dependent on the reaction type and conditions [25]. The same formalism applies to reaction rates, where log(k/k₀) = σρ [25].

The initial determination of substituent constants was based on the ionization of benzoic acid derivatives in water at 25°C, with the reaction constant ρ arbitrarily set to 1.0 for this reference reaction [25]. This provided a standardized framework for quantifying electronic effects across diverse chemical structures.

Key Substituent Constants and Electronic Effects

Hammett constants effectively capture two dominant electronic influences: the inductive effect, transmitted through polarization of bonding electrons, and the resonance effect, involving electron delocalization through π-systems [25]. The resulting σ values reveal fundamental electronic properties of substituents, with positive values indicating electron-withdrawing characteristics and negative values signifying electron-donating properties [25].

Table 1: Selected Hammett Substituent Constants

| Substituent | σ_meta | σ_para |

|---|---|---|

| Nitro | +0.710 | +0.778 |

| Cyano | +0.560 | +0.660 |

| Chloro | +0.373 | +0.227 |

| Hydrogen | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Methyl | -0.069 | -0.170 |

| Methoxy | +0.115 | -0.268 |

| Hydroxy | +0.120 | -0.370 |

| Amino | -0.161 | -0.660 |

The discrepancy between meta and para values for certain substituents, particularly evident with methoxy and hydroxy groups, highlights the differential weighting of resonance effects at these positions [25]. Para substituents can engage in direct resonance interactions with the reaction center, while meta substituents exert primarily inductive effects due to their positional relationship in the aromatic ring.

Extended Hammett Parameters and Reaction Sensitivity

For specific chemical environments where standard σ values proved insufficient, specialized parameters were developed. The σp- constants were defined using ionization of para-substituted phenols to better capture resonance interactions with electron-withdrawing groups [25]. Conversely, σp+ constants were developed based on SN1 reactions of cumyl chlorides to better describe carbocation stabilization by electron-donating groups [25].

The reaction constant ρ provides crucial information about a reaction's sensitivity to substituent effects [25]:

- ρ > 1: The reaction is more sensitive to substituents than benzoic acid ionization; negative charge builds up (or positive charge is lost)

- 0 < ρ < 1: The reaction is less sensitive to substituents but still builds negative charge

- ρ = 0: No sensitivity to substituents; no charge buildup or loss

- ρ < 0: The reaction builds positive charge (or loses negative charge)

This quantitative framework enabled mechanistic insights that transformed physical organic chemistry and laid the groundwork for modern QSAR approaches.

Evolution to 2D QSAR: Incorporating Diverse Molecular Descriptors

The Hansch Equation and Beyond

The extension of Hammett's principles to biological systems began with the work of Hansch and Fujita, who incorporated lipophilicity parameters alongside electronic effects [23]. The classic Hansch equation takes the form:

where C represents the molar concentration of compound producing a standard biological effect, σ is the Hammett electronic constant, and logP is the logarithm of the octanol-water partition coefficient, encoding lipophilicity [23]. This approach recognized that biological activity depends not only on electronic effects but also on transport properties determining a compound's ability to reach its site of action.

Modern 2D Descriptors in Cancer Research

Contemporary 2D QSAR studies employ sophisticated mathematical descriptors derived from molecular graph theory. These topological indices (TIs) capture molecular connectivity, shape, and branching patterns, providing quantitative parameters that can be correlated with biological activity [26]. In cancer therapeutic development, such approaches have been successfully applied to analyze blood cancer drugs, with strong correlations observed between topological indices and physicochemical properties critical for drug efficacy [26].

Table 2: Categories of Modern Molecular Descriptors in QSAR

| Descriptor Category | Representative Examples | Structural Information Encoded |

|---|---|---|

| Topological Descriptors | Wiener index, Zagreb index, Randic connectivity index | Molecular branching, connectivity, size |

| Geometric Descriptors | Principal moments of inertia, molecular volume | Molecular shape and dimensions |

| Electronic Descriptors | HOMO/LUMO energies, partial atomic charges, molecular dipole moment | Electronic distribution, reactivity |

| Quantum Chemical Descriptors | MEP (Molecular Electrostatic Potential), Fukui indices | Reactivity sites, charge distribution |

| Hybrid Descriptors | MECN (Min exchange energy for a C-N bond) | Combined electronic and structural features |

A recent QSAR study of dihydropteridone derivatives as PLK1 inhibitors for glioblastoma treatment identified MECN (Min exchange energy for a C-N bond) as the most significant molecular descriptor in a 2D model containing six descriptors [27]. This highlights how modern descriptors integrate specific quantum chemical properties with traditional structural parameters to enhance predictive capability.

Experimental Protocol for 2D QSAR Modeling

The standard methodology for developing 2D QSAR models involves several critical steps [27]:

Compound Selection and Activity Data Curation: A diverse set of compounds with reliable biological activity data (e.g., IC₅₀ values) is assembled. For the dihydropteridone derivatives study, 34 compounds with anti-glioma activity were obtained from published research [27].

Molecular Structure Optimization: Chemical structures are sketched using software such as ChemDraw and optimized through molecular mechanics (MM+ force field) followed by semi-empirical methods (AM1 or PM3) until the root mean square gradient reaches 0.01 [27].

Descriptor Calculation: Comprehensive molecular descriptors encompassing quantum chemical, structural, topological, geometric, and electrostatic properties are computed using programs like CODESSA [27].

Data Set Partitioning: Compounds are randomly divided into training and test sets (typically 3:1 or 4:1 ratio) to enable model development and validation [27].

Model Construction: Statistical methods such as the Heuristic Method (HM) or machine learning algorithms like Gene Expression Programming (GEP) are employed to build correlation models between descriptors and biological activity [27].

Model Validation: The predictive power of developed models is assessed using the test set data, with metrics including R², R²_cv (cross-validated R²), and residual sum of squares [27].

2D QSAR Modeling Workflow

Rise of 3D-QSAR: Incorporating Spatial Molecular Information

The Paradigm Shift to Three Dimensions

While 2D QSAR approaches consider molecular structure as connectivity graphs, 3D-QSAR methodologies incorporate the essential three-dimensional nature of molecular interactions, recognizing that biological recognition depends strongly on spatial characteristics [28]. This transition represents a fundamental advancement in molecular descriptor evolution, as 3D-QSAR explicitly accounts for molecular shape, steric bulk, and electronic distribution in three-dimensional space.

The theoretical foundation of 3D-QSAR rests on the understanding that drug-receptor interactions occur through specific three-dimensional complementarity, following theories such as "lock-and-key," "induced fit," and "conformational selection" [23]. The portion of the interface area belonging to the drug that contains the essential geometric arrangement of atoms or functional groups necessary for binding is termed the pharmacophore [23].

3D-QSAR Methodologies and Field Descriptors

Advanced 3D-QSAR approaches, particularly CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis), examine the impact of drug structure on activity by calculating molecular interaction fields surrounding aligned molecules [27]. These fields include:

- Steric fields representing van der Waals interactions

- Electrostatic fields capturing Coulombic interactions

- Hydrophobic fields describing lipophilic preferences

- Hydrogen bond donor and acceptor fields quantifying specific polar interactions

In the dihydropteridone derivatives study for glioblastoma treatment, the 3D-QSAR model demonstrated exceptional performance with Q² = 0.628 and R² = 0.928, significantly outperforming 2D approaches [27]. This superior performance highlights the value of incorporating spatial and field information into QSAR modeling.

Experimental Protocol for 3D-QSAR Modeling

The standard workflow for 3D-QSAR analysis involves several key stages [27] [28]:

Molecular Structure Preparation and Optimization: 3D molecular structures are generated from 2D representations and energetically minimized using molecular mechanics or quantum chemical methods.

Molecular Alignment: A critical step where molecules are superimposed according to a common pharmacophore or structural framework. This alignment assumes similar binding modes to the biological target.

Interaction Field Calculation: Molecular interaction fields are computed using probe atoms at regularly spaced grid points surrounding the aligned molecules.

Statistical Analysis: Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is typically employed to correlate interaction field values with biological activity, identifying regions where specific molecular properties enhance or diminish activity.

Contour Map Generation: The results are visualized as 3D contour maps indicating favorable and unfavorable regions for different molecular properties relative to biological activity.

3D QSAR Modeling Workflow

Modern Applications in Cancer Therapeutics

QSAR in Anti-Cancer Drug Discovery

QSAR methodologies have become indispensable tools in modern anti-cancer drug discovery, particularly for optimizing lead compounds and predicting activity profiles. Recent applications span diverse cancer types, including breast cancer, colorectal cancer, glioblastoma, and blood cancers [27] [26] [23].

In breast cancer research, QSAR has been extensively applied to discover and develop new therapeutic agents [23]. The methodology has proven valuable for predicting biological activity of compounds targeting specific breast cancer subtypes and mechanisms, facilitating more efficient drug design and prioritization of synthesis candidates.

For colorectal cancer, innovative 3D-QSAR approaches utilizing 3D electron cloud descriptors have demonstrated remarkable predictive capabilities [29]. By computing electron densities via density functional theory (DFT) and converting them to 3D point clouds encoded into multi-scale descriptors, researchers achieved Area Under the Curve (AUC) values of 0.96 with Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM) algorithms, significantly outperforming conventional ECFP4 fingerprints [29].

Case Study: Dihydropteridone Derivatives for Glioblastoma

A comprehensive QSAR study on dihydropteridone derivatives as PLK1 inhibitors for glioblastoma treatment exemplifies the integrated application of 2D and 3D QSAR methodologies [27]. This research demonstrated:

- The Heuristic Method linear model achieved R² = 0.6682 with R²_cv = 0.5669

- The Gene Expression Programming nonlinear model showed improved performance with R² = 0.79 for training and 0.76 for validation

- The 3D-QSAR CoMSIA model outperformed both with Q² = 0.628, R² = 0.928, and standard error of estimate = 0.160

By combining the most significant 2D descriptor (MECN) with 3D hydrophobic field information, researchers designed novel compound 21E.153, which exhibited outstanding antitumor properties and docking capabilities [27]. This successful integration of descriptor types highlights the power of hybrid approaches in modern cancer drug design.

Table 3: Essential Resources for Modern QSAR Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Software | Application in QSAR |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Drawing & Visualization | ChemDraw, PyMOL | Molecular structure representation and visualization |

| Molecular Modeling & Optimization | HyperChem, Gaussian, Open Babel | 3D structure generation and quantum chemical calculations |

| Descriptor Calculation | CODESSA, DRAGON, PaDEL | Computation of molecular descriptors |

| QSAR Modeling Platforms | 3D-QSAR.com, Orange, KNIME | Integrated platforms for QSAR model development |

| Statistical Analysis | R, Python (scikit-learn) | Data analysis and machine learning implementation |

| Validation Tools | Various internal and external validation metrics | Model quality assessment |

Advanced Descriptor Technologies and Future Perspectives

Cutting-Edge Descriptor Development

The evolution of molecular descriptors continues with emerging technologies that capture increasingly sophisticated aspects of molecular structure and properties. 3D electron cloud descriptors represent one such advancement, addressing limitations of conventional QSAR descriptors in capturing molecular electronic and spatial complexity [29]. These descriptors are computed via density functional theory (DFT), converted to 3D point clouds, and encoded into multi-scale descriptors including radial distribution functions, spherical harmonic expansions, point feature histograms, and persistent homology [29].

Control experiments confirming that predictive gains stem from electronic structure information rather than high-dimensional geometry alone highlight the increasing sophistication of modern descriptor technologies [29]. This approach demonstrates how quantum mechanical properties can be systematically integrated into QSAR modeling, opening new avenues for molecular representation in drug discovery.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Integration

Contemporary QSAR research increasingly leverages artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms to handle the complexity of modern descriptor sets [30] [31] [24]. Counter-Propagation Artificial Neural Networks (CPANN) and other neural network architectures have shown particular promise for classifying molecules based on endpoint classes such as enzyme inhibition and hepatotoxicity [30].

Modified CPANN algorithms that dynamically adjust molecular descriptor importance during model training allow different descriptor importance values for structurally different molecules, increasing adaptability to diverse compound sets [30]. This approach improves molecule classification, reduces neurons excited by molecules from different endpoint classes, and increases the number of acceptable models [30].

Future Directions in Descriptor Evolution

The future of molecular descriptors in cancer QSAR studies points toward several exciting developments:

Multi-Omics Integration: Combining QSAR with genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data to build comprehensive models that account for both compound properties and biological system complexity [24].

AI-Driven High-Throughput Screening: Leveraging artificial intelligence to optimize multi-target drug design and enhance translational research from preclinical to clinical stages [24].

Standardized Platform Development: Creating unified platforms for data integration and analysis to address challenges such as data variability and off-target effects [24].

Enhanced Interpretability: Developing methods to improve model interpretability while maintaining predictive power, balancing complexity with mechanistic understanding [30].

As these technologies mature, the vision of personalized cancer medicine—tailoring treatments based on individual patient characteristics and tumor profiles—will gradually approach reality, significantly enhancing treatment efficacy and patient quality of life [24].

In modern cancer drug discovery, the concept of "chemical space" provides a crucial framework for understanding the relationship between molecular structure and biological activity. This conceptual space encompasses all possible organic molecules, with each point representing a unique compound defined by a set of molecular descriptors—numerical representations of structural, topological, and physicochemical properties [32]. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling leverages these descriptors to建立 mathematical models that predict the biological activity of compounds against cancer targets, transforming drug discovery from trial-and-error to a rational, predictive science [32] [33].

The dimensionality challenge presents a significant obstacle in QSAR modeling. Researchers can compute hundreds to thousands of molecular descriptors for each compound using modern cheminformatics software [32] [34]. This high-dimensional data space suffers from the "curse of dimensionality," where many descriptors are redundant, noisy, or irrelevant to the biological endpoint [32]. Descriptor optimization thus becomes essential for building robust, interpretable, and predictive QSAR models, particularly in oncology applications where dataset sizes are often limited [35]. Through strategic dimensionality reduction, researchers can navigate the chemical space more effectively, identifying the most informative structural domains for targeting cancer pathways.