MIQE Guidelines for Cancer Biomarker Validation: Ensuring Reproducibility in Molecular Diagnostics

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines specifically for cancer biomarker validation.

MIQE Guidelines for Cancer Biomarker Validation: Ensuring Reproducibility in Molecular Diagnostics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on implementing MIQE (Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments) guidelines specifically for cancer biomarker validation. Covering foundational principles, methodological applications, troubleshooting strategies, and validation frameworks, we detail how MIQE-compliant workflows ensure reproducible and clinically relevant results when validating biomarker signatures discovered through next-generation sequencing. With emphasis on the updated MIQE 2.0 guidelines and their integration with domain-specific standards like MISEV for extracellular vesicle research, this resource addresses the critical need for methodological rigor in translating qPCR-based cancer biomarkers from discovery to clinical application.

Understanding MIQE: The Foundation of Reproducible Cancer Biomarker Research

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and reverse transcription qPCR (RT-qPCR) represent cornerstone technologies in molecular biology, forming the bedrock of gene expression analysis, pathogen detection, and molecular diagnostics. Despite their widespread adoption, the reproducibility and reliability of qPCR data have been persistently challenged by substantial variations in experimental conduct and reporting. To address this critical gap, the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines were first introduced in 2009, establishing a standardized framework for the design, execution, and documentation of qPCR experiments [1]. Over the past 16 years, MIQE has become one of the most widely cited methodological publications in molecular biology, informing journal editorial policies and contributing to the development of ISO standards for molecular diagnostics [1]. The recent publication of MIQE 2.0 in 2025 marks a critical milestone, refining and updating these guidelines to maintain their relevance amidst evolving technologies and applications, particularly in the high-stakes field of cancer biomarker validation [2] [1]. This evolution represents a concerted effort by an international consortium of multidisciplinary experts to ensure that qPCR remains a trustworthy tool for scientific discovery and clinical application.

The Original MIQE Guidelines (2009): Establishing a Foundation

The original MIQE guidelines, published in Clinical Chemistry in 2009, emerged as a response to growing concerns about the transparency, quality, and reproducibility of qPCR-based research [1]. Their primary goal was to provide a comprehensive checklist of minimum information required to ensure the repeatability and reproducibility of qPCR experiments. The guidelines established standards spanning all aspects of the qPCR workflow, encompassing experimental design, sample quality, assay validation, and data analysis [3].

A cornerstone of the original MIQE was its emphasis on detailed reporting. It mandated comprehensive documentation of nucleic acid extraction methods, quality assessment (including RNA integrity numbers), reverse transcription conditions, primer and probe sequences, amplification efficiency, and normalization strategies [4]. The guidelines stressed that mere citation of the MIQE paper was insufficient; instead, authors were expected to provide all necessary methodological details to allow independent verification of their results. This framework gave researchers, reviewers, and editors a common language for evaluating qPCR data quality, aiming to curb the publication of irreproducible findings and exaggerated claims, particularly in sensitive areas like biomarker discovery [1] [4].

The Driving Forces for Revision: Why MIQE Needed an Update

The expansion of qPCR into numerous new domains over the 16 years following the original publication drove the development of new reagents, methods, consumables, and instruments, creating a pressing need for updated best practices [2]. While the original MIQE guidelines raised awareness, compliance remained patchy and often superficial. A troubling complacency surrounding qPCR methodology persisted, with many studies suffering from fundamental flaws such as unverified nucleic acid quality, unvalidated assay efficiencies, inappropriate normalization using unverified reference genes, and overinterpretation of minimal fold-changes without assessment of measurement uncertainty [1].

The COVID-19 pandemic starkly illustrated the real-world consequences of variable quality in qPCR applications. While qPCR was central to global testing efforts, inconsistencies in assay design, data interpretation, and public communication undermined confidence in diagnostics [1]. Furthermore, the translational gap between research and clinical application became increasingly apparent, especially in fields like cancer biomarker validation. Despite promising findings, the noticeable lack of technical standardization remained a huge obstacle in the translation of qPCR-based tests from bench to bedside [5]. The emergence of new applications, including the analysis of complex sample types like liquid biopsies for circulating miRNA and DNA methylation biomarkers, further exposed limitations of the original guidelines [6] [7] [8]. These challenges collectively underscored the urgent need for a revised, more applicable set of guidelines.

MIQE 2.0 (2025): Key Updates and Advancements

Building on the collaborative efforts of an international team of researchers, MIQE 2.0 presents updates, simplifications, and new recommendations designed to maintain relevance in the context of emerging technologies and evolving qPCR applications [2] [9]. The revised guidelines reflect recent advances in qPCR technology and offer clear recommendations for sample handling, assay design, and validation, along with refined guidance on qPCR data analysis [2].

Enhanced Focus on Transparent Data Reporting and Analysis

MIQE 2.0 reinforces that quantification cycle (Cq) values should not be reported as final results. Instead, they must be converted into efficiency-corrected target quantities, reported with prediction intervals, along with detection limits and dynamic ranges for each target, based on the chosen quantification method [2]. The guidelines encourage instrument manufacturers to enable the export of raw data to facilitate thorough analyses and re-evaluation by manuscript reviewers and interested researchers [2]. Furthermore, reporting requirements have been clarified and streamlined to encourage researchers to provide all necessary information without undue burden, thereby promoting more rigorous and reproducible qPCR research [2].

Specific Provisions for Advanced Applications

The revised guidelines offer more tailored guidance for complex applications central to modern molecular biology. For miRNA biomarker validation—a prominent field in cancer research—MIQE 2.0 emphasizes the need for orthogonal validation of signatures initially identified by next-generation sequencing (NGS) [6] [7]. This is particularly relevant for liquid biopsies, where miRNA stability and complex normalization strategies present unique challenges [7]. Similarly, the guidelines support the growing use of DNA methylation biomarkers in liquid biopsies for cancer diagnosis, which leverage the inherent stability of DNA and its relative resistance to degradation compared to RNA [8]. The workflow for such biomarkers typically involves discovery via whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) or reduced representation bisulfite sequencing (RRBS), followed by targeted, highly sensitive validation using qPCR or digital PCR (dPCR) [8].

Table 1: Core Updates in MIQE 2.0 Compared to the Original MIQE Guidelines

| Aspect | MIQE (2009) | MIQE 2.0 (2025) |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Scope | Established foundational principles for standard qPCR | Addresses emerging applications (e.g., liquid biopsies, complex biomarkers) |

| Data Analysis | Emphasized need for efficiency calculation and proper normalization | Mandates conversion of Cq to efficiency-corrected quantities with prediction intervals |

| Transparency | Advocated for detailed methodology reporting | Encourages raw data export and provides simplified reporting requirements |

| Technology Integration | Focused primarily on qPCR workflow | Acknowledges and provides guidance for validation of NGS-derived signatures |

Practical Implementation in Cancer Biomarker Research

For researchers engaged in cancer biomarker validation, adherence to MIQE 2.0 is not merely a publication formality but a critical component of developing robust, clinically translatable assays. The following section outlines practical protocols and a toolkit for implementing these guidelines.

Experimental Workflow for Biomarker Validation

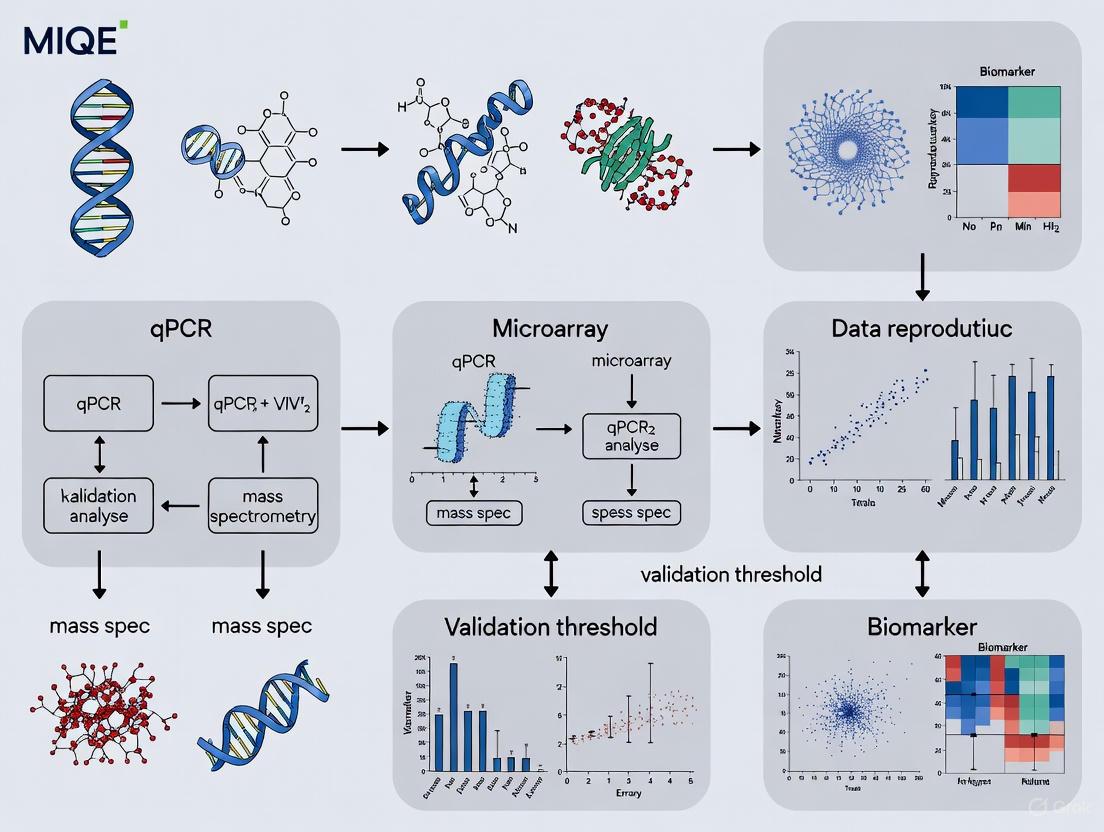

The typical pipeline for establishing a transcriptional biomarker signature begins with an unbiased discovery phase using RNA-Seq on a subset of representative samples, followed by a targeted validation phase using RT-qPCR across the entire cohort in compliance with MIQE guidelines [6] [7] [4]. The diagram below illustrates this workflow, highlighting key MIQE 2.0 checkpoints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of the workflow above requires carefully selected reagents and tools. The following table details key materials needed for a MIQE-compliant biomarker validation study.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for MIQE-Compliant Cancer Biomarker Validation

| Item | Function/Description | MIQE 2.0 Compliance Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Stabilization Reagents(e.g., RNAlater, PAXgene) | Preserves nucleic acid integrity immediately after collection, preventing degradation. | Critical for obtaining high-quality RNA; directly impacts RNA Integrity Number (RIN) and subsequent quantification accuracy [7] [4]. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isulates high-purity RNA/DNA from complex matrices like blood, urine, or tissue. | Must be documented precisely (including manufacturer and catalog number). Efficiency and purity (A260/A280 ratios) must be reported [1]. |

| Quality Assessment Instruments(e.g., Bioanalyzer, Fragment Analyzer) | Objectively assesses RNA/DNA integrity and quantity (e.g., RIN, DV2000). | Provides essential quality metrics that must be reported. Poor RNA integrity has a demonstrated, measurable impact on RT-qPCR results [7] [4]. |

| TaqMan Assays | Predesigned, highly specific probe-based qPCR assays for target quantification. | Providing the unique Assay ID and the amplicon context sequence fulfills MIQE 2.0 requirements for assay sequence disclosure [3]. |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | Converts RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) for RT-qPCR. | Protocol (including priming strategy, enzyme, and volume used) must be thoroughly documented, as variability here is a major source of technical noise [1] [7]. |

Data Analysis and Normalization Strategy

A pivotal update in MIQE 2.0 is the reinforced mandate against using raw Cq values. Data analysis must incorporate PCR amplification efficiency for accurate quantification [2] [1]. For gene expression studies, normalization using stably expressed reference genes is non-negotiable. These genes must be empirically validated for stability under the specific experimental conditions; the use of a single reference gene is strongly discouraged unless thoroughly justified [1] [7]. The final output should be reported as efficiency-corrected target quantities, ideally with associated confidence measures.

For interpreting the resulting complex dataset, multivariate data analysis tools are indispensable. Principal Components Analysis (PCA) can visually demonstrate the separation of sample groups (e.g., cancer vs. control) based on the expression profile of the validated biomarker signature [4]. Hierarchical Cluster Analysis (HCA) and corresponding heatmaps further allow for the visualization of expression patterns across all samples and targets, confirming the robustness of the diagnostic or prognostic signature [4]. The diagram below outlines this core data analysis pipeline.

The evolution from MIQE to MIQE 2.0 represents a significant maturation in the molecular biology community's approach to one of its most fundamental techniques. The updated guidelines provide an authoritative, detailed roadmap for remedying the well-documented deficiencies in qPCR application and reporting [1]. However, as the authors themselves stress, guidelines alone are not enough. What is needed now is a cultural change among researchers, reviewers, journal editors, and regulatory agencies [1].

For the field of cancer biomarker research, the stakes are exceptionally high. A diagnostic platform that cannot reliably distinguish small fold-changes in target concentration at clinically relevant levels is not fit for purpose [1]. The transition of DNA methylation and miRNA biomarkers from concept to clinic, as seen in tests like Epi proColon, hinges on such methodological rigor [8]. The argument that rigorous implementation of MIQE slows down publication is counterproductive; if data cannot be reproduced, they are not worth publishing [1].

The credibility of molecular diagnostics and the integrity of the research that supports it now depend on the collective will to ensure that qPCR results are not just published, but are also robust, reproducible, and reliable. MIQE 2.0 provides the updated framework to achieve this. The scientific community now has the tools, the evidence, and the guidelines; the responsibility to implement them rests with every individual conducting, reviewing, or applying qPCR-based research.

The reproducibility of scientific findings is a cornerstone of scientific progress, yet many fields, including molecular diagnostics and biomarker research, face a significant reproducibility crisis. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) is a ubiquitous technology in these fields, but its perceived simplicity often leads to poorly designed and reported experiments, generating unreliable results. This technical guide explores how the Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines serve as a powerful tool to combat this crisis, with a specific focus on their critical role in validating robust transcriptional biomarkers for cancer research. By mandating comprehensive reporting and rigorous experimental practice, MIQE compliance ensures the generation of credible, reproducible data that can reliably inform drug development and clinical diagnostics.

Fluorescence-based quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) is a fundamental technology in molecular biology, yet the inadequate reporting of experimental detail, combined with the frequent use of flawed protocols, has led to the publication of papers that may not be technically sound [10]. This problem is particularly acute in the development of transcriptional biomarkers for cancer, where the ultimate goal is often to create clinical diagnostic tests. The conclusions of thousands of peer-reviewed publications rely on data obtained using qPCR technology, but the relegation of materials and methods to online supplements often makes it impossible for reviewers and readers to judge a manuscript's technical adequacy [10].

The MIQE guidelines were established to address these challenges by providing a standardized framework for the execution and reporting of qPCR experiments [3]. Their primary aim is to achieve reproducibility and credibility of experimental results by ensuring that all critical experimental conditions are comprehensively documented [3] [11]. For cancer biomarker research, where qPCR is used to validate biomarker signatures discovered via high-throughput sequencing, adherence to MIQE is not merely a publication formality but a fundamental requirement for ensuring experimental validity [12] [6]. It gives researchers the tools to document all aspects of their qPCR experiments, from sample preparation to data analysis, thereby providing a bulwark against the reproducibility crisis [3].

The Central Role of qPCR in Transcriptional Biomarker Validation

Transcriptional biomarkers, which include messenger RNAs (mRNAs), long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), and microRNAs (miRNAs), offer significant advantages in molecular diagnostics. They allow for immediate detection of cellular changes, as the transcriptional profile of a cell responds to a signal within minutes, while alterations may only be visible after hours on the protein level [12]. Liquid biopsies, which are minimally invasive, have become a prominent source for these biomarkers, providing systemic information from blood plasma, urine, or saliva that might be missing in tissue biopsies [12].

The pipeline for developing these biomarkers typically begins with a holistic discovery phase, such as RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq), to establish a candidate biomarker signature. However, this must be followed by a confirmation process using a highly precise and reproducible method [12] [6]. This is where RT-qPCR proves its immense value. As a fast and reproducible quantification method, it is the gold standard for validating discovered biomarker signatures before they can be deployed in routine molecular diagnostics or personalized medicine [12]. The reliability of this validation step is paramount; a flawed process can lead to the promotion of useless biomarkers or the rejection of truly valuable ones.

Advantages of Nucleic Acid Biomarkers

- Low Detection Limits: Nucleic acids can be amplified by PCR, enabling detection at significantly lower concentrations than proteins [12].

- Cost Efficiency: Detection does not require highly affine and expensive antibodies, unlike many protein-based assays [12].

- Direct Link to Disease: Many diseases are directly caused by DNA changes, which are more easily detected by PCR-based methods than antibody-based assays [12].

- Stability in Circulation: miRNAs, for example, are relatively stable in body fluids due to protection within extracellular vesicles or by RNA-binding proteins [12].

Table 1: Types of Transcriptional RNA Biomarkers with Examples

| RNA Type | Size | Example | Disease Context | Potential Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | Varies | PAM50 |

Breast Cancer | Diagnosis/Prognosis |

| lncRNA | >200 nt | HOTAIR |

Breast Cancer | Prognosis |

| miRNA | ~22 nt | miR-141 |

Prostate Cancer | Diagnosis |

| isomiR | ~22 nt | 5'isomiR-140-3p |

Breast Cancer | Prognosis |

The MIQE Guidelines: A Framework for Rigor

The MIQE guidelines are a set of minimum information standards that a researcher must provide when publishing qPCR experiments. This initiative was born from a clear need: a lack of consensus on how best to perform and interpret qPCR experiments, exacerbated by insufficient experimental detail in many publications [11]. This inadequacy impedes a reader's ability to critically evaluate the quality of the results or to repeat the experiments.

The core objective of MIQE is to ensure the integrity of the scientific literature, promote consistency between laboratories, and increase experimental transparency [11] [13]. By providing all relevant experimental conditions and assay characteristics, reviewers and readers can assess the validity of the protocols used. Full disclosure of reagents, sequences, and analysis methods is necessary to enable other investigators to reproduce results, which is the bedrock of the scientific method [11].

Key Pillars of the MIQE Guidelines

The guidelines cover the entire workflow of a qPCR experiment. The following are particularly critical for biomarker research:

Sample and Template Quality

The source, handling, and quality of the starting material fundamentally impact results. For RNA templates, the following must be reported:

- Tissue Source and Storage Conditions: Critical for longitudinal studies [10].

- Nucleic Acid Quality and Quantity: Assessed using tools like microfluidics-based systems (e.g., Bioanalyzer) [10].

- DNA Contamination: The extent of residual genomic DNA contamination must be reported, typically by comparing quantification cycles (Cq) with and without reverse transcription [10].

- Inhibition Testing: Every sample, or a representative set, should be tested for the absence of inhibitors using a spike-in control or a dilution series [10].

Assay Optimization and Validation

A key source of irreproducibility is the use of unvalidated or poorly characterized assays.

- Oligo Sequences and Accession Numbers: Primer sequences and database accession numbers must be reported. Disclosure of probe sequences is strongly encouraged [10]. For commercial assays like TaqMan, the unique Assay ID and the amplicon context sequence should be provided to comply with MIQE [3].

- Specificity and Efficiency: Primer specificity must be validated in silico (e.g., BLAST) and empirically (e.g., gel electrophoresis, melting curves). PCR efficiency for each assay must be determined using a calibration curve and reported [10].

- Precision: Measures of intra-assay variation (repeatability) and, for diagnostic assays, inter-assay precision (reproducibility) should be reported [10].

Experimental Run and Controls

The setup of the qPCR plate itself must be meticulously planned and documented.

- Essential Controls: The following controls are mandatory:

- Run Layout: A "sample maximisation" strategy (running all samples for a gene on the same plate) is encouraged over a "gene maximisation" strategy to minimise run-to-run variation. If multiple runs are necessary, inter-run calibrators (IRCs) must be used [10].

Data Analysis and Normalization

Improper data analysis is a major source of error.

- Reference Gene Validation: Normalization using reference genes is an essential component of a reliable qPCR assay. Their utility must be validated for the specific tissues or cell types in the experiment at hand. Normalization should generally be performed against multiple reference genes (at least three), chosen from a sufficient number of candidates using a dedicated algorithm like geNorm [10].

- Special Considerations for miRNA: For miRNA expression profiling, normalisation should be performed against the mean expression value of all expressed miRNAs in large-scale experiments. For smaller studies, suitable reference miRNAs must be identified through pilot experiments [10]. It is critical to use specialized miRNA extraction protocols, as extraction efficiency can be highly variable [10].

Figure 1: A MIQE-compliant workflow for validating a transcriptional biomarker signature discovered by next-generation sequencing. Adherence to MIQE at the validation stage ensures the reliability and reproducibility of the final biomarker [12] [6] [10].

A Practical MIQE Checklist for Cancer Biomarker Researchers

For the practicing scientist, the full MIQE guidelines can appear daunting. The following table summarizes the absolute minimum information required for publishing a qPCR-based biomarker study, adapted from the "MIQE précis" [10]. This checklist can serve as a practical guide for both designing experiments and preparing manuscripts.

Table 2: Essential MIQE Checklist for Biomarker Researchers

| Category | Information Required | Why It Matters for Biomarkers |

|---|---|---|

| Sample | Tissue/sample source, storage conditions, nucleic acid quality/quantity (e.g., RIN), DNA contamination assessment. | Liquid biopsies (e.g., plasma, urine) have unique handling requirements. Sample quality directly impacts quantification accuracy [12] [10]. |

| Assay | Primer sequences, amplicon size, database accession numbers. Strongly encouraged: Probe sequence. Validation data: PCR efficiency, correlation coefficient (R²) from calibration curve, linear dynamic range. | Ensures the assay correctly targets the biomarker (e.g., specific miRNA or isomiR) and operates with high sensitivity and efficiency over the required concentration range [3] [10]. |

| qPCR Protocol | Detailed reagent concentrations, instrument details, complete cycling conditions. | Necessary for exact experimental replication in another lab, a prerequisite for multi-center biomarker validation [11]. |

| Controls | No template control (NTC), no amplification control (NAC). For RNA: no-reverse transcription control. For multi-plate runs: inter-run calibrators (IRCs). | Detects contamination and monitor assay performance. IRCs correct for run-to-run variation, critical for large patient cohort studies [10]. |

| Data Analysis | Cq determination method, normalization strategy (validated reference genes/miRNAs), software used, statistical methods for precision. | Using unvalidated reference genes is a primary source of error. Proper normalization is essential for accurate fold-change calculations between patient and control groups [10]. |

Implementing MIQE requires not only a change in practice but also the use of appropriate reagents and tools. The following table details key resources that facilitate MIQE-compliant biomarker research.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for MIQE-Compliant Workflows

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Role in MIQE Compliance |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized miRNA Kits | Optimized for isolation of small RNAs from liquid biopsies (plasma, urine). | Ensures efficient and consistent recovery of miRNA biomarkers, which is reagent-dependent and can be variable [10]. |

| Validated Assay Panels | Pre-designed and optimized primer/probe sets (e.g., TaqMan Assays). | Provides a standardized, well-characterized assay with known performance metrics (efficiency, specificity), reducing validation burden [3]. |

| DNA Removal Kits | Treatment of RNA samples with DNase to digest residual genomic DNA. | Critical for providing evidence of the absence of DNA contamination, an essential MIQE requirement for RNA templates [13] [10]. |

| Inhibition Test Kits | "Alien" spike-in controls or synthetic oligonucleotides. | Allows for testing each sample or a representative set for the presence of PCR inhibitors, a key QC step [10]. |

| Reference Gene Panels | Pre-selected sets of candidate reference genes for specific tissues or conditions. | Provides a starting point for the rigorous validation of multiple reference genes required for reliable normalization [10]. |

Figure 2: The relationship between common causes of irreproducible qPCR data and their corresponding solutions as prescribed by the MIQE guidelines. Addressing these technical flaws systematically is key to improving data integrity [11] [10].

The MIQE guidelines represent more than just a checklist for publication; they are a fundamental component of rigorous scientific practice in qPCR-based biomarker research. By addressing the root causes of the reproducibility crisis—inadequate experimental design, insufficient validation, and opaque reporting—MIQE provides a clear path toward generating reliable and credible data. For the field of cancer biomarker validation, where the ultimate stakes involve clinical decision-making and patient outcomes, the adoption of MIQE is not optional but imperative. It ensures that biomarker signatures are built on a foundation of technical robustness, enabling their successful translation from the research bench to clinical applications in diagnostics and personalized medicine. As the technology and applications evolve, a commitment to these minimum standards will be crucial for maintaining the integrity of the scientific literature and accelerating the development of impactful molecular diagnostics.

Within the critical field of cancer biomarker validation, the reliability of quantitative PCR (qPCR) data can directly influence diagnostic and therapeutic decisions. The Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines provide a standardized framework to ensure the reproducibility and credibility of these experiments [3]. Despite their importance, widespread methodological failures—such as unreported PCR efficiencies and unvalidated reference genes—undermine data integrity, a particularly dangerous shortcoming in translational cancer research [14]. The recently released MIQE 2.0 guidelines update and refine these standards to address technological advances and persistent challenges [2]. This guide details the three pillars of robust qPCR assay validation—Cq values, amplification efficiency, and dynamic range—within the context of MIQE 2.0, providing a structured approach essential for any rigorous cancer biomarker research program.

Core Concepts and Definitions

Cq (Quantification Cycle) Values

The Cq value (Quantification Cycle) is the foundational metric in qPCR, defined as the cycle number at which the amplification curve crosses the quantification threshold. The MIQE 2.0 guidelines emphasize that Cq values alone are not reliable endpoints for publication; they must be converted into efficiency-corrected target quantities to allow for meaningful biological interpretation and cross-laboratory comparison [2]. Accurate Cq determination depends critically on a well-designed assay and proper baseline and threshold settings. In cancer research, where fold-changes in gene expression can be small yet biologically significant, precise and accurate Cq measurement is non-negotiable.

Amplification Efficiency

Amplification Efficiency (E) is a critical performance parameter that quantifies the rate of target amplification during the exponential phase of the PCR reaction. An ideal reaction, where the amount of product doubles every cycle, has an efficiency of 100% (E=2.0). In practice, the MIQE guidelines require researchers to determine and report the actual efficiency of each assay, not assume it [14]. Efficiency values outside the optimal range (typically 90–110%) indicate suboptimal assay performance that will skew relative quantification results, leading to inaccurate estimates of biomarker expression levels—a common source of irreproducibility in the literature.

Dynamic Range

The Dynamic Range of a qPCR assay defines the span of template concentrations over which the assay provides reliable quantification. It is bounded at the lower end by the Limit of Detection (LOD) and at the upper end by the point where the reaction plateau begins. The MIQE guidelines mandate that the dynamic range be established for each target using a calibration curve and reported in the manuscript [2]. For cancer biomarker applications, such as detecting low-abundance transcripts from circulating tumor cells or monitoring minimal residual disease, a wide dynamic range and a low LOD are paramount for clinical utility.

The relationship between these three concepts is fundamental to a properly validated assay. Amplification efficiency directly influences the accuracy of the calculated template concentration from a given Cq value, and this relationship must be linear across the entire reported dynamic range of the assay. Failure to characterize and report on all three elements in concert is a major source of unreliable data.

Diagram 1: The workflow from sample to reliable quantification, highlighting the essential inputs required for accurate calculation of target quantity.

MIQE 2.0 Reporting Requirements

The MIQE 2.0 guidelines have clarified and updated the reporting requirements for qPCR experiments to promote transparency and reproducibility [2]. The table below summarizes the essential information that must be reported for Cq values, amplification efficiency, and dynamic range in the context of a publication.

Table 1: Essential MIQE 2.0 Reporting Requirements for Core qPCR Concepts

| Concept | Specific Data to Report | Clinical/Biomarker Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cq Values | - Method for Cq determination- Export of raw data for independent verification [2] [14] | Report Cq values converted to efficiency-corrected target quantities with prediction intervals [2]. |

| Amplification Efficiency | - Calculated value for each assay (e.g., from slope of standard curve)- How the efficiency was determined | Critical for accurate fold-change calculations in biomarker expression studies [14]. |

| Dynamic Range | - Limit of Detection (LOD)- Upper and lower limits of quantification | Must be established for each target; vital for detecting low-abundance cancer transcripts [2]. |

Beyond these core concepts, MIQE 2.0 also stresses the importance of comprehensive reporting on sample quality, nucleic acid integrity, and rigorous validation of reference genes used for normalization [14]. These factors collectively form the foundation upon which reliable qPCR data is built.

Experimental Protocols for Assay Validation

Generating a Standard Curve for Efficiency and Dynamic Range

The standard curve is the primary tool for determining both amplification efficiency and dynamic range.

Detailed Protocol:

- Template Preparation: Create a serial dilution (e.g., 1:10 or 1:5) of a known, high-quality template (e.g., a plasmid containing the target amplicon or a cDNA sample with high expression of the target gene). Use gravimetric or volumetric dilutions for maximum accuracy [15].

- qPCR Run: Amplify each dilution in replicate (at least 3 technical replicates) using the same qPCR conditions planned for the experimental samples.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the mean Cq value for each dilution against the logarithm of its known initial concentration.

- Perform linear regression on the plot. The slope of the line is used to calculate amplification efficiency: E = 10^(-1/slope).

- The R² value of the regression indicates the linearity of the assay across the dilution series, which defines the dynamic range.

- The Limit of Detection (LOD) is the lowest concentration in the dilution series that yields a consistent Cq value and is distinguishable from the no-template control (NTC).

Assay Specificity and Sequence Verification

For cancer biomarker research, confirming that an assay amplifies only the intended target is paramount.

Detailed Protocol:

- In Silico Specificity Check: Use tools like BLAST to ensure primers and probes are specific to the target sequence, especially to distinguish it from homologous pseudogenes or family members, which is common in cancer-related genes [15].

- Amplicon Context Sequence: To comply with MIQE guidelines on assay disclosure, provide the probe or amplicon context sequence. For TaqMan assays, this can be generated using the assay ID and RefSeq accession number via the NCBI nucleotide database [3].

- Experimental Verification: Analyze the qPCR end-product by gel electrophoresis to confirm a single band of the expected size, or use melt curve analysis for intercalating dye-based assays to confirm a single, sharp peak.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MIQE-Compliant qPCR

| Item | Function/Description | MIQE Compliance Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| TaqMan Assays | Predesigned, sequence-specific primer-probe sets. | Provide the unique Assay ID and, for full compliance, the amplicon context sequence from the Assay Information File (AIF) [3]. |

| Nucleic Acid Integrity Analyzer | Instrument (e.g., Bioanalyzer) to assess RNA Quality Number (RQN) or RNA Integrity Number (RIN). | Essential for documenting sample quality. Poor RNA integrity is a major source of variable reverse transcription and erroneous results [14]. |

| Standard Curve Template | Purified plasmid, gBlock, or cDNA with known concentration for generating calibration curves. | Required for calculating amplification efficiency and defining the dynamic range for each assay [2]. |

| Validated Reference Gene Assays | qPCR assays for genes used for normalization of target data. | Must be validated for stable expression across all experimental conditions (e.g., tumor vs. normal tissue); using unvalidated reference genes is a common failure [14]. |

Diagram 2: The logical relationship between foundational practices, core concepts, required actions, and the ultimate goal of reliable data.

The updated MIQE 2.0 guidelines provide a critical roadmap for generating qPCR data that is not only publishable but also clinically actionable. For researchers validating cancer biomarkers, a rigorous understanding and application of the principles surrounding Cq values, amplification efficiency, and dynamic range is non-negotiable. These concepts are deeply interconnected, forming the bedrock of any assay that aims to accurately quantify subtle but meaningful changes in gene expression. As emphasized by the international consortium behind MIQE 2.0, the ultimate goal is a cultural shift towards unwavering methodological rigor [14]. By adhering to these guidelines, the scientific community can ensure that qPCR results underpinning cancer biomarker discovery and validation are robust, reproducible, and reliable, thereby accelerating the translation of molecular findings into tangible patient benefits.

The Role of MIQE in Cancer Biomarker Development Pipelines

In the field of oncology, the discovery and validation of robust cancer biomarkers represent a critical pathway toward improving early detection, prognosis, and personalized treatment strategies. The pipeline from biomarker discovery to clinical application, however, is fraught with challenges, primarily concerning the reproducibility and reliability of experimental data. Among the various technological platforms used, reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) has emerged as a cornerstone for target validation due to its sensitivity, specificity, and quantitative capabilities. The Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines provide a standardized framework designed to ensure the transparency and technical rigor of qPCR experiments. This technical guide examines the integral role of MIQE compliance within cancer biomarker development pipelines, detailing how its application enhances the validity of transcriptional biomarkers across diverse liquid biopsy sources and RNA classes, thereby strengthening the translational bridge from research discovery to clinical diagnostics.

MIQE Guidelines: Evolution and Core Principles

The MIQE guidelines were originally established in 2009 to address widespread concerns about the reproducibility of qPCR-based research. The recent publication of MIQE 2.0 in 2025 reflects a significant evolution of these standards, incorporating advances in qPCR technology and the growing complexities of its applications [2].

The Core Principles of MIQE

The foundational principle of MIQE is that a transparent, clear, and comprehensive description of all experimental details is necessary to ensure the repeatability and reproducibility of qPCR results [2]. The guidelines encompass all phases of a qPCR experiment:

- Experimental Design: Appropriate sample collection, storage, and processing conditions.

- Assay Validation: Specificity, sensitivity, and efficiency of primer/probe sets.

- Data Acquisition and Analysis: Guidelines for robust quantification cycle (Cq) determination, data normalization, and statistical analysis.

- Reporting Standards: Detailed requirements for the information that must be included in publications to allow independent verification.

A key update in MIQE 2.0 is the emphasis on converting raw Cq values into efficiency-corrected target quantities and reporting them with prediction intervals [2]. This moves beyond simple relative quantification to a more accurate absolute measurement, which is crucial for the cross-laboratory comparability required in biomarker development.

The Cancer Biomarker Development Pipeline: Integration of MIQE-Compliant Validation

The development of a cancer biomarker follows a multi-stage pipeline, from initial discovery to clinical application. MIQE-compliant validation acts as a critical checkpoint, ensuring that candidate biomarkers identified through high-throughput screening possess the analytical robustness to proceed further. Figure 1 below illustrates this integrated workflow.

Figure 1. Integration of MIQE-Compliant Validation into the Cancer Biomarker Development Pipeline. The workflow shows the transition from high-throughput discovery platforms to targeted, MIQE-compliant RT-qPCR validation, which is a critical gatekeeper for the development of robust clinical assays.

From High-Throughput Discovery to Targeted Validation

The initial stage of biomarker development often involves holistic profiling using technologies like next-generation sequencing (NGS) or microarrays. For example, small RNA sequencing can identify differential expression of microRNAs (miRNAs) in blood total RNA, establishing a candidate biomarker signature [6]. Similarly, RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) is used to discover messenger RNA (mRNA) and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) signatures [12] [7]. These high-throughput methods are powerful for discovery but can be subject to technical noise and may not be readily implementable in a clinical setting.

The transition from discovery to validation is a critical juncture. Candidates identified by NGS must be confirmed by an orthogonal technology—a method based on different principles. RT-qPCR is the most widely used platform for this validation due to its quantitative nature, sensitivity, and potential for high-throughput clinical implementation [6] [12]. Performing this validation in accordance with MIQE guidelines is paramount to ensure that the observed differential expression is biologically real and not an artifact of the discovery platform or a poorly optimized assay.

Application of MIQE Across Different Transcriptional Biomarker Classes

MIQE principles provide a universal framework that can be adapted to the specific challenges of quantifying different RNA biomarker classes found in liquid biopsies. Table 1 summarizes the key advantages and MIQE compliance considerations for major RNA types.

Table 1: MIQE-Compliant Analysis of Major Transcriptional Biomarker Classes in Liquid Biopsies

| RNA Class | Key Characteristics | Advantages as Biomarkers | MIQE Compliance Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | Protein-coding transcripts; ~1-2% of transcriptome. | Direct link to pathological processes; expression in blood is 80% identical to major tissues [12]. | Critical reference gene validation for normalization; careful RNA quality control due to lability. |

| miRNA | Short (~22 nt) non-coding RNAs; regulate gene expression. | High stability in biofluids; resistant to RNases; tissue-specific expression; protected in extracellular vesicles [12] [7]. | Specialized reverse transcription for short templates; assay design to distinguish canonical miRNAs from isomiRs [12]. |

| lncRNA | Long non-coding RNAs (>200 nt). | High tissue-specificity; associated with numerous diseases, especially cancer [7]. | Similar to mRNA; ensure assay specificity across often low-abundance and overlapping transcripts. |

MIQE in the Validation of miRNA Biomarkers

The validation of miRNA biomarkers is a prime example of MIQE's application. After a biomarker signature is established by small RNA sequencing, MIQE-compliant RT-qPCR validation is used for confirmation [6]. Key steps where MIQE guidelines are critical include:

- Assay Design: Designing primers and probes that accurately quantify the mature miRNA molecule, which is very short. Assays must be specific enough to potentially distinguish between closely related miRNA family members and different isomiRs (miRNA isoforms), which can have different target repertoires and even higher discriminatory power for cancer [12] [7].

- Normalization: Selecting and validating appropriate reference genes for data normalization is a core MIQE principle. This is particularly important for liquid biopsies, as traditional cellular reference genes may not be stably expressed in cell-free biofluids. The use of validated, stably expressed reference genes or spike-in controls is recommended [16].

Integration with Other Domain-Specific Guidelines

For biomarkers derived from specific substrates like extracellular vesicles (EVs), MIQE should be integrated with other domain-specific guidelines. EVs are nanoscale particles released by cells that carry molecular cargo, including RNAs, and are a promising source for liquid biopsy biomarkers [17] [16].

The MISEV (Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles) guidelines provide essential domain-specific recommendations for EV isolation, characterization, and reporting [16]. While MISEV ensures the quality and identity of the EV preparation itself, it deliberately refrains from prescribing methods for molecular quantification. This is where MIQE becomes indispensable. Integrating MIQE into the MISEV framework creates a comprehensive workflow that guarantees analytical rigor from EV isolation through to the quantitative analysis of EV-associated RNA cargo by RT-qPCR [16]. This synergy between general analytical (MIQE) and domain-specific (MISEV) standards provides a scalable blueprint for improving reproducibility in complex biomarker development workflows.

Essential Reagents and Methodologies for MIQE-Compliant Workflows

Adhering to MIQE guidelines requires careful selection and documentation of reagents and methodologies. The following section outlines key components and protocols for a MIQE-compliant biomarker validation experiment.

Research Reagent Solutions for MIQE Compliance

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for MIQE-Compliant Biomarker Validation

| Item | Function in Workflow | MIQE Compliance Requirement |

|---|---|---|

| TaqMan Assays | Predesigned, optimized primer-probe sets for specific targets. | Publication of unique Assay ID and amplicon context sequence fulfills MIQE sequence disclosure guidelines [3]. |

| Reference Gene Panels | A set of candidate genes for normalization. | Validation of stable expression in the specific sample matrix (e.g., plasma, serum) is mandatory; no single universal reference gene exists [12] [16]. |

| RNA Spike-in Controls | Synthetic, exogenous RNA molecules. | Controls for reverse transcription efficiency and normalization in samples with low or variable RNA input (e.g., EV isolates) [16]. |

| Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR) | An orthogonal technology for absolute quantification. | Used for technical validation; provides highly sensitive, absolute quantification of target molecules without relying on Cq values, ideal for low-abundance targets in liquid biopsies [18]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Validation of a Candidate miRNA Biomarker

This protocol exemplifies a MIQE-compliant workflow for validating a miRNA biomarker candidate previously identified by small RNA-Seq in a plasma liquid biopsy study [6] [12].

Sample Preparation (Pre-analytical Phase):

- Collect peripheral blood in EDTA or citrate tubes. Process within 2 hours to isolate plasma via double-centrifugation to avoid cell contamination.

- Isolve total RNA from 200-500 µL of plasma using a phenol-guanidine based method, including spike-in synthetic miRNAs (e.g., cel-miR-39) to control for extraction efficiency.

Reverse Transcription (RT):

- Convert RNA to cDNA using a miRNA-specific stem-loop RT primer. This method increases specificity and efficiency for short RNA templates.

- Include a minus-RT control (a reaction without the reverse transcriptase enzyme) for each sample to detect potential genomic DNA contamination.

MIQE-Compliant qPCR Assay:

- Use a predesigned TaqMan MicroRNA Assay. Record the Assay ID (e.g., hsa-miR-21-5p, Assay ID 000397) and obtain the amplicon context sequence from the manufacturer's website to fulfill MIQE disclosure requirements [3].

- Perform amplification in technical triplicates on a calibrated qPCR instrument.

- Include a standard curve (e.g., a 5-point, 10-fold serial dilution of a synthetic target) in each run to determine the amplification efficiency (should be 90-110% with an R² > 0.99).

- Include no-template controls (NTCs) to check for reagent contamination.

Data Analysis and Normalization:

- Export raw Cq values. Use the standard curve to convert Cqs into efficiency-corrected target quantities.

- Normalize the data using a validated strategy. This could be the ratio of the target miRNA quantity to the geometric mean of multiple validated reference genes (e.g., miR-16-5p, miR-92a-3p) that have been shown to be stable in your sample cohort. Alternatively, use the spike-in synthetic miRNA for normalization.

- Report the normalized quantities with appropriate confidence intervals or prediction intervals for each sample group, as emphasized in MIQE 2.0 [2].

The MIQE guidelines provide an indispensable foundation for building robust, reliable, and reproducible cancer biomarker development pipelines. By enforcing rigorous standards for experimental design, assay validation, data analysis, and transparent reporting, MIQE compliance directly addresses the critical issue of translational failure. As the field advances, with discoveries expanding into new RNA classes and complex liquid biopsy sources like extracellular vesicles, the integration of MIQE with other domain-specific standards such as MISEV will become increasingly important. For researchers and drug development professionals, the adoption of MIQE is not merely a matter of publication compliance but a fundamental component of a quality system that ensures only the most rigorously validated biomarker candidates progress toward clinical application, ultimately accelerating the development of effective molecular diagnostics for cancer patients.

The convergence of the Minimal Information for Studies of Extracellular Vesicles (MISEV) and Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines represents a critical framework for advancing robust, reproducible cancer biomarker research. Extracellular vesicles have emerged as promising minimally invasive biomarkers for cancers, including endometrial cancer, due to their stability in biofluids, molecular richness, and reflection of their parent cell's pathological state [19] [20] [21]. However, variability in EV workflows and inadequate standardization of downstream molecular analysis pose major obstacles to reproducibility and clinical translation [16]. The MISEV guidelines provide essential domain-specific recommendations for EV isolation, characterization, and reporting but deliberately refrain from prescribing methods for molecular quantification of EV cargo [16] [22]. Meanwhile, MIQE 2.0 offers a detailed foundation for ensuring analytical validity in RT-qPCR-based quantification, which remains the most critical method for validating and quantifying EV-associated RNA [16] [1]. This integration creates a comprehensive quality framework that bridges pre-analytical EV-specific considerations with rigorous nucleic acid quantification standards, addressing a critical gap in the biomarker development pipeline.

Understanding the Complementary Roles of MISEV and MIQE

Scope and Positioning Within the EV Analysis Pipeline

MISEV and MIQE guidelines address complementary stages of the EV biomarker workflow. MISEV provides domain-specific standards for pre-analytical phases and EV characterization, while MIQE defines best practices for the molecular quantification phase. Their integrated application ensures comprehensive quality control from sample collection to data interpretation.

Table 1: Scope and Positioning of MISEV and MIQE Guidelines in EV Analysis

| Stage in EV Workflow | MISEV-Specific | MIQE-Specific | Both | Example Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-analytical | EV source description; isolation method; removal of contaminants; storage conditions | Not directly addressed | Transparent reporting of sample provenance, handling, and storage | Volume/type of starting material; storage temperature/duration; processing time |

| Characterization | Particle size, distribution and concentration; protein markers; imaging; biochemical composition | Not directly addressed | Documentation of EV purity and integrity alongside downstream molecular assays | Particle concentration units; vesicle morphology images; marker expression profiles |

| Molecular Assay Preparation | MISEV2023 §5.5: quantification of total RNA; MISEV2023 §6.5: nucleic acid characterization | RNA quality/quantity assessment; contamination checks | RNA input quantity, quality control, and contamination assessment | RNA integrity metrics; yield per vesicle/volume; DNA contamination checks |

| Assay Design & Validation | MISEV2023 §6.5: recognition of nucleic acid characterization/validation requirements | Primer/probe sequences; specificity checks; amplification efficiency; RT conditions | Transparency in assay design, validation of controls/standards, overall reproducibility | Primer sequence disclosure; efficiency 90%-110%; linear dynamic range; RT protocol |

| Data Acquisition | Not directly addressed | Reporting of Cq values; inclusion of controls (NTC, -RT); melt curves; replicates | Use of appropriate controls, standards and full reporting of raw data | Raw Cq tables; replicate Cq SD; melt curve profiles |

| Data Analysis & Reporting | Transparent description of EV identity/purity | Normalization strategy; error metrics; statistical analysis; confidence intervals | Reporting raw data tables, replicate statistics, technical vs. biological variability | Reference gene validation; normalization method; %CV on fold changes |

Fundamental Principles of MISEV

MISEV guidelines, developed by the International Society for Extracellular Vesicles, establish essential practices for EV research through several foundational principles. The guidelines recommend using operational terms like "small EVs" and "large EVs" based on physical characteristics rather than potentially ambiguous biogenetic terminology such as "exosomes" [16] [19]. They mandate the use of multiple complementary characterization techniques, including particle quantification (e.g., NTA, TRPS), visualization (e.g., TEM), and assessment of EV-specific protein markers (e.g., CD63, CD9, CD81) alongside negative markers to confirm absence of contaminants [19]. MISEV emphasizes transparent reporting of methodological details including isolation methods, source of biological material, and handling procedures to enable experimental replication [16]. The guidelines also stress functional characterization where appropriate, linking EV properties to biological outcomes in well-controlled assays.

Fundamental Principles of MIQE

The MIQE guidelines, originally published in 2009 and updated to MIQE 2.0, establish rigorous standards for quantitative PCR experiments through several core principles [11] [1]. They mandate comprehensive assay validation including demonstration of primer specificity, determination of amplification efficiency through standard curves, and establishment of linear dynamic range [3] [15]. MIQE emphasizes rigorous experimental design with appropriate technical and biological replication, inclusion of essential controls, and validation of reference genes for normalization [1]. The guidelines require complete transparency in reporting, including detailed descriptions of sample quality, nucleic acid extraction methods, reaction conditions, and raw data availability [3] [11]. MIQE also addresses appropriate data analysis methods including proper normalization strategies, statistical treatment, and clear reporting of uncertainty metrics [1].

Integrated Experimental Workflow: From EV Isolation to Quantitative Analysis

Diagram 1: Integrated MISEV-MIQE Workflow for EV Biomarker Research. This diagram illustrates the sequential stages of EV-based biomarker analysis, highlighting where MISEV and MIQE guidelines apply throughout the process.

EV Isolation and Characterization (MISEV-Compliant)

The initial phase focuses on obtaining high-quality EV preparations from biological samples using MISEV-compliant methods. Differential ultracentrifugation remains widely used, employing sequential centrifugation steps to remove cells, debris, and concentrate EVs [19]. Size-based separation techniques include size-exclusion chromatography, which preserves EV integrity, and ultrafiltration, though potential vesicle deformation should be considered [20]. Precipitation methods using polymers offer convenience but may co-precipitate contaminants [19]. For characterization, nanoparticle tracking analysis determines particle size distribution and concentration, while tunable resistive pulse sensing provides similar information with potentially improved sizing accuracy [19]. Transmission electron microscopy and atomic force microscopy offer morphological information at high resolution [20]. Western blot analysis or comparable techniques should demonstrate presence of EV-associated proteins and absence of contaminating proteins [19].

Nucleic Acid Extraction and Quality Control

Nucleic acid extraction from EV preparations requires methods optimized for limited starting material while maintaining reproducibility. Commercial kits specifically designed for EV RNA extraction are recommended as they typically include carrier molecules to improve recovery efficiency [16]. RNA quality assessment should include spectrophotometric or fluorometric quantification with acceptable 260/280 ratios (1.8-2.0 for RNA, 1.7-1.9 for DNA), and RNA integrity measurement using appropriate metrics when sufficient material is available [16]. Contamination checks should include assessment of genomic DNA contamination and, where relevant, hemolysis indicators for blood-derived samples [16]. The use of spike-in controls, such as recombinant EVs engineered to contain exogenous RNA, is encouraged to monitor extraction efficiency and enable normalization across samples [16].

Assay Design and Validation (MIQE-Compliant)

Robust assay design and validation are essential for generating reliable quantification data. Primer and probe sequences must be disclosed or accessible through databases, with in silico specificity verification using tools like BLAST and consideration of pseudogenes or homologous sequences [3] [15]. Experimental validation should include efficiency determination via serial dilution with acceptable efficiency ranges of 90-110%, demonstration of linear dynamic range over at least 3 orders of magnitude, and confirmation of specificity through melt curve analysis or sequencing of amplification products [3]. Essential controls must include no-template controls, minus reverse transcription controls for RNA assays, and inter-plate calibrators for experiments run across multiple plates [16]. Reference gene selection requires validation of stability across all experimental conditions using algorithms like geNorm or NormFinder [16].

Practical Implementation Strategies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated MISEV-MIQE Workflows

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| TaqMan Assays | Predesigned qPCR assays with optimized primers and probes | Provide assay ID and amplicon context sequence for MIQE compliance; >296K citations support widespread acceptance [3] |

| RNA Extraction Kits (EV-optimized) | Isolation of high-quality RNA from limited EV samples | Include carrier RNA to improve yield; select kits with DNase treatment to minimize genomic DNA contamination [16] |

| Reference Gene Panels | Validated stable reference genes for normalization | Essential for accurate quantification; requires validation across specific EV populations and biological conditions [16] |

| NTA Instrumentation | Particle quantification and size distribution analysis | Provides MISEV-required characterization of EV preparations; complement with protein markers for comprehensive characterization [19] |

| EV Separation Matrix | Size-exclusion chromatography media for gentle EV isolation | Preserves EV integrity better than harsh precipitation methods; reduces co-isolation of contaminants [19] |

| Synthetic Spike-in Controls | Exogenous RNA/DNA sequences for process monitoring | Added pre-extraction to monitor efficiency; enables normalization across different sample batches [16] |

Methodological Details for Key Experiments

For EV RNA quantification, the integrated approach requires specific methodological considerations. Starting material should be standardized by particle number rather than volume alone, with typical inputs of 10^8-10^9 particles for RNA extraction [16]. Reverse transcription should use optimized conditions with documented enzyme type, priming strategy, and reaction conditions, as RT efficiency significantly impacts quantitative results [16]. qPCR reaction optimization must include determination of optimal annealing temperature through gradient PCR, template input titration, and validation of minimal variation between technical replicates [3]. Data analysis should incorporate appropriate normalization strategies using validated reference genes, statistical methods that account for both technical and biological variability, and clear reporting of confidence intervals for fold-change calculations [16] [1].

Analysis of Current Adherence and Implementation Challenges

Implementation of integrated MISEV-MIQE standards faces several practical challenges. A systematic review of EV biomarkers in endometrial cancer revealed that none of the 23 included studies provided complete evidence supporting biomarkers being encapsulated within EVs rather than associated with co-isolated contaminants [19]. Only 7 of 23 studies (30%) characterized EVs using multiple complementary techniques as recommended by MISEV, while 6 studies (26%) failed to report any pre-analytical variables related to sample collection and processing [19]. Common deficiencies in qPCR aspects included insufficient description of RNA quality metrics, absence of amplification efficiency data, and inadequate validation of reference genes [19] [1]. The predominance of low-sample-size studies (typically <50 cases) combined with methodological limitations raises concerns about the validity of reported biomarkers and their potential for clinical translation [19].

Analytical Framework: Quality Assessment and Validation

Critical Appraisal of EV Biomarker Studies

A systematic evaluation framework is essential for assessing the quality of EV biomarker studies. The following criteria provide a structured approach to quality assessment, with specific examples from endometrial cancer biomarker research:

Table 3: Quality Assessment Framework for EV Biomarker Studies

| Assessment Domain | High-Quality Indicators | Common Deficiencies | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| EV Characterization | Multiple techniques (NTA+imaging+protein markers); reporting of particle concentration & size distribution | Single characterization method; incomplete marker panels; missing negative controls | Only 7/23 endometrial cancer EV studies used multiple characterization techniques [19] |

| Assay Validation | Reported amplification efficiency; linear dynamic range; specificity verification; reference gene stability | Assumed rather than measured efficiency; unvalidated reference genes; missing controls | Widespread reporting of fold-changes without measurement uncertainty or efficiency calculations [1] |

| Technical Replication | Appropriate technical replicates; clear distinction between technical and biological variation; reported Cq variation | Insufficient replicates; undefined replication strategy; high variation not addressed | Analyses of qPCR literature show serious deficiencies in experimental transparency [1] |

| Data Transparency | Raw Cq values available; complete reaction conditions; primer sequences disclosed | Selective data reporting; insufficient methodological detail; undisclosed sequences | Incomplete reporting remains prevalent despite MIQE awareness [1] |

| Analytical Specificity | Demonstration of EV association rather than co-isolation; controls for non-vesicular biomarkers | Assumption without evidence that biomarkers are EV-associated | No studies in endometrial cancer review provided complete evidence of EV encapsulation [19] |

Validation Strategies for EV-Associated Biomarkers

Rigorous validation is particularly challenging for EV-associated biomarkers due to sample heterogeneity and limited starting material. Orthogonal validation using different methodological approaches provides stronger evidence, such as correlating EV miRNA findings with tissue expression or independent quantification methods [19]. For miRNA biomarkers identified in endometrial cancer, the most promising candidates (miR-21-3p, miR-26a-5p, miR-130a-3p, miR-139, and miR-219a-5p) showed expression patterns in EV preparations that reflected those in endometrial tissue [19]. Spike-in controls using engineered EVs with known RNA content enable absolute quantification and inter-laboratory comparison, addressing critical reproducibility challenges [16]. Inter-laboratory reproducibility testing through multi-center validation studies is essential for clinical translation, though rarely implemented in current EV biomarker research [19].

The integration of MISEV and MIQE guidelines provides a comprehensive framework for enhancing the rigor and reproducibility of extracellular vesicle biomarker research. This synergistic approach addresses the entire workflow from EV isolation through molecular quantification, creating a robust foundation for generating reliable, clinically translatable data. The current literature reveals significant opportunities for improvement in methodological reporting and experimental design, particularly in the characterization of EV preparations and validation of quantitative assays. As EV biomarkers continue to show promise for cancer diagnosis and monitoring—with several candidate miRNAs already emerging for endometrial cancer—adherence to these integrated standards becomes increasingly critical. By embracing this combined framework, researchers can overcome existing reproducibility challenges, accelerate the validation of promising biomarkers, and ultimately advance the field toward meaningful clinical applications in precision oncology.

Implementing MIQE-Compliant Workflows in Cancer Biomarker Development

Within the framework of cancer biomarker validation, the reliability of any quantitative PCR (qPCR) result is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the starting material. The Minimum Information for Publication of Quantitative Real-Time PCR Experiments (MIQE) guidelines, recently updated to version 2.0, emphasize that transparent and comprehensive reporting of sample quality assessment is not optional but essential for reproducibility and credibility [2] [3]. For research aimed at discovering and validating cancer biomarkers, where experimental outcomes may directly influence clinical decision-making, rigorous pre-analytical control is paramount. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of assessing RNA integrity and contamination controls, aligning with the stringent requirements of the MIQE guidelines to ensure that qPCR data generated for cancer biomarker research is robust, reliable, and reproducible.

RNA Integrity Assessment

RNA integrity is a critical determinant for the success of downstream applications like qPCR. Degraded RNA can lead to biased quantification, false positives, or false negatives, ultimately jeopardizing the validity of a biomarker's reported performance.

Gel Electrophoresis

The traditional method for assessing RNA integrity involves denaturing agarose gel electrophoresis. This technique separates RNA molecules by size, allowing for visual inspection of the major ribosomal RNA (rRNA) bands.

- Principle: Under denaturing conditions, RNA is separated by molecular weight. Sharp, distinct rRNA bands indicate intact RNA, while a smear suggests degradation [23].

- Interpretation: For eukaryotic total RNA, intact samples display sharp 28S and 18S rRNA bands. A key quality metric is the 28S:18S rRNA intensity ratio, which should be approximately 2:1 for high-quality RNA [23] [24]. A diminished ratio or a smeared appearance indicates partial or complete degradation (see Figure 1, lane 2) [23].

- Considerations: This method requires a relatively large amount of RNA (at least 200 ng for ethidium bromide staining) and is less suited for low-yield samples. Sensitivity can be improved using fluorescent dyes like SYBR Gold, which can detect as little as 1-2 ng of RNA [23] [24].

Microfluidics-Based Analysis (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer/TapeStation)

Microfluidics-based systems offer a more automated, sensitive, and quantitative alternative to gel electrophoresis.

- Principle: These systems use microchips with integrated channels filled with a polymer matrix. RNA samples are separated electrophoretically, and the resulting data is presented as both a gel-like image and an electropherogram [23] [24].

- Interpretation: The electropherogram provides a detailed profile of the RNA sample. Intact RNA shows distinct peaks for the 18S and 28S rRNAs, while the baseline in the low-molecular-weight region is flat. From this data, a RNA Integrity Number (RIN) or similar metric (e.g., RQN) is algorithmically derived, providing a numerical score from 1 (degraded) to 10 (intact) [23].

- Advantages: This method is highly sensitive, requiring as little as 5 ng of RNA per analysis, and provides simultaneous information on concentration, integrity, and potential contaminants [23]. It is the gold standard for pre-qPCR quality control, especially for precious cancer biopsy samples.

Table 1: Comparison of RNA Integrity Assessment Methods

| Method | Principle | Sample Required | Key Output | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denaturing Agarose Gel | Size-based separation via electrophoresis | ~200 ng (EtBr) [23] | 28S:18S rRNA ratio (visually estimated) | Low cost; simple to perform [23] [24] | Semi-quantitative; higher sample requirement; uses hazardous dyes [24] |

| Microfluidics (Bioanalyzer) | Microchip-based capillary electrophoresis | ~5-50 ng [23] | RNA Integrity Number (RIN); Electropherogram | High sensitivity; quantitative; provides concentration and integrity [23] [24] | Higher instrument cost; specialized chips required |

The following workflow diagram outlines the logical process for assessing RNA integrity, from sample preparation to interpretation of results and the subsequent decision-making process.

Contamination Controls and Purity Assessment

Contaminants in an RNA sample can profoundly inhibit enzymatic reactions like reverse transcription and qPCR, leading to inaccurate Cq values and compromised data. The MIQE guidelines stress the importance of reporting purity metrics [2].

Spectrophotometric Analysis (UV Absorbance)

UV absorbance is a ubiquitous method for the rapid quantification of nucleic acids and assessment of common contaminants.

- Principle: Nucleic acids and proteins absorb ultraviolet light at characteristic wavelengths. Concentration and purity ratios are calculated from these absorbance values [24].

- Key Metrics:

- A260/A280 Ratio: This assesses protein contamination. Acceptable ratios for pure RNA are generally 1.8–2.2 [24]. A ratio below 1.8 often indicates residual phenol or protein contamination.

- A260/A230 Ratio: This assesses contamination by salts, guanidine, or carbohydrates. This ratio should ideally be greater than 1.7 [24]. A low A260/A230 ratio suggests the presence of co-purified reagents common in isolation kits.

- Limitations: Absorbance cannot distinguish between DNA and RNA, nor can it detect genomic DNA contamination in an RNA preparation. It is also insensitive to degradation, as free nucleotides still absorb at 260 nm [24].

Fluorescent Dye-Based Quantification

Fluorometers using RNA-binding dyes offer a highly sensitive alternative for quantification.

- Principle: Fluorescent dyes bind specifically to RNA, and the resulting fluorescence is measured against a standard curve [24].

- Advantages: This method is significantly more sensitive than absorbance, capable of detecting RNA concentrations as low as 1 pg/µl [24]. This is ideal for quantifying low-yield samples common in cancer research (e.g., from microdissections).

- Disadvantages and Controls: Most fluorescent dyes are not RNA-specific and will also bind to DNA, potentially leading to an overestimation of RNA concentration. To comply with MIQE standards for accurate quantification, a DNase treatment step is strongly recommended prior to measurement to eliminate this confounding variable [24].

Table 2: Methods for RNA Quantification and Purity Assessment

| Method | Principle | Sensitivity | Information Provided | Key Considerations for MIQE Compliance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV Spectrophotometry | Absorbance of UV light at 260nm, 280nm, 230nm | 2 ng/µl [24] | Concentration, A260/A280, A260/A230 ratios | Cannot detect gDNA contamination; overestimates concentration if contaminants absorb at 260nm [24] |

| Fluorometry | Fluorescence of RNA-binding dyes | 1 pg/µl (1000x more sensitive) [24] | Highly accurate RNA concentration | Requires DNase treatment to avoid gDNA confounding; provides no purity (absorbance) information [24] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful RNA work requires specialized reagents and materials to preserve and assess sample quality. The following table details essential items for maintaining RNA integrity and ensuring accurate quality control.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for RNA Quality Control

| Item | Function | Application in Cancer Biomarker Research |

|---|---|---|

| RNase Decontamination Reagents | To inactivate ubiquitous RNases on surfaces, glassware, and equipment [25]. | Critical for maintaining a sterile workflow, especially when processing multiple patient-derived samples to prevent cross-contamination and sample degradation. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents (e.g., RNAprotect, PAXgene) | To immediately stabilize RNA at the moment of sample collection by inhibiting RNases [25]. | Vital for preserving the in vivo gene expression profile of clinical specimens (e.g., biopsies, blood) during transport and storage, preventing biomarker degradation. |

| DNase I, RNase-free | To digest contaminating genomic DNA in RNA preparations [24]. | Essential for obtaining accurate qPCR results in biomarker validation, as gDNA contamination can lead to false positive signals and overestimation of transcript levels. |

| Microfluidics Kits (e.g., RNA 6000 Nano Kit) | To perform RNA integrity and quantification analysis on systems like the Agilent Bioanalyzer [23]. | Provides the high-sensitivity analysis needed for low-input samples from core needle biopsies or laser-capture microdissected tissue areas. |

| RNA-Specific Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., Quant-iT RiboGreen) | To enable highly sensitive quantification of RNA concentrations, especially for dilute samples [24]. | Allows for accurate normalization of input RNA in downstream cDNA synthesis, a key requirement for reproducible qPCR data in biomarker assays. |

Best Practices for RNA Handling and Storage

Adherence to strict handling protocols is the first line of defense in preserving RNA integrity.

- Create an RNase-Free Environment: Designate a clean workspace dedicated to RNA use. Regularly decontaminate surfaces with RNase-inactivating reagents. Use single-use, certified RNase-free plasticware [25].

- Practice Aseptic Technique: Always wear gloves and change them frequently. Use filtered pipette tips to prevent aerosol contamination [25].

- Minimize Degradation During Processing: Keep samples on ice whenever possible. Use rapid and effective homogenization methods to quickly inactivate endogenous RNases present in tissues [25].

- Optimize Storage Conditions: For long-term storage, divide RNA into single-use aliquots to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Store aliquots at -70°C or in stabilization reagents that allow for room-temperature storage for limited periods [25].

In the context of MIQE-guided cancer biomarker research, the assessment of RNA integrity and contamination is a non-negotiable step that underpins all subsequent data. The failure to adequately quality-control starting material introduces an uncontrolled variable that can invalidate the entire experimental outcome. By systematically implementing the methodologies and controls outlined in this guide—employing sensitive integrity checks, verifying purity, utilizing essential reagents correctly, and adhering to rigorous handling protocols—researchers can ensure their qPCR data is a true reflection of the biomarker's expression, thereby contributing to robust, reproducible, and clinically translatable scientific findings.