Medical Image Denoising: A Comprehensive Guide to Techniques, Validation, and Clinical Application for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of data denoising techniques for medical images, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Medical Image Denoising: A Comprehensive Guide to Techniques, Validation, and Clinical Application for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of data denoising techniques for medical images, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental challenge of balancing noise reduction with the preservation of critical diagnostic features in modalities like MRI and CT. The scope ranges from foundational concepts and a detailed examination of traditional, deep learning, and generative AI methodologies to practical troubleshooting for common pitfalls like over-smoothing and computational bottlenecks. A strong emphasis is placed on rigorous validation, comparing performance using quantitative metrics and clinical evaluation to guide the selection of optimal denoising strategies for precision-critical biomedical research.

The Critical Foundation: Why Medical Image Denoising is a Lifesaving Challenge

The Impact of Noise on Diagnostic Accuracy and Treatment Planning

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How does image noise quantitatively impact the accuracy of key diagnostic measurements?

Image noise introduces significant inaccuracies in the quantification of physiological parameters, which can compromise clinical decisions. The impact is particularly pronounced in functional imaging techniques like CT perfusion (CTp), where precise blood flow (BF) measurement is critical.

Observed Impact on CT Perfusion Blood Flow [1]:

- Phantom Study Findings: In a controlled study using Digital Perfusion Phantoms (DPPs), the introduction of Gaussian noise (standard deviation of 25 HU) caused a substantial deviation in blood flow measurements.

- Quantitative Data: The table below summarizes the effect of noise and subsequent correction on BF measurements.

| Condition | Pancreatic Parenchyma BF (ml/100 ml/min) | PDAC* BF (ml/100 ml/min) | Contrast-to-Noise Ratio (CNR) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ground Truth | 225.0 ± 120.0 | 37.5 ± 20.2 | - |

| With Noise Impact | 218.0 ± 112.0 | 62.1 ± 11.5 | 2.52 |

| After Noise Correction | 224.0 ± 119.0 | 39.7 ± 21.9 | 2.66 |

*PDAC: Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma.

The data shows that noise can lead to a 65.6% overestimation of blood flow in tumor tissue (PDAC), severely distorting the perceived physiological state. A model-based noise correction algorithm successfully reduced the absolute noise error from 18.8 ml/100 ml/min to 3.6 ml/100 ml/min [1].

FAQ 2: What denoising methods are available for structural MRI and how is their performance validated?

For structural MRI, denoising algorithms based on deep learning have been developed to enhance image quality without compromising critical anatomical details.

Solution: Smart Noise Reduction in MRI [2] This method uses residual convolutional neural networks trained via supervised learning to remove noise while preserving image contrast. The system offers different neural networks and adjustable denoising levels to balance noise removal and detail preservation.

Performance Evaluation Metrics: Validation relies on quantitative metrics comparing denoised images to a reference or low-noise "ground truth" [2]:

- Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR): Higher values indicate better noise removal.

- Structural SIMilarity (SSIM) Index: Measures perceptual image quality and structural preservation (1 indicates perfect similarity).

The table below shows the performance of three different neural networks on a test dataset with two noise levels [2]:

| Noise Level | Metric | Network: Quick | Network: Strong | Network: Large |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std. 0.05 | PSNR | 37.272 | 38.592 | 39.152 |

| SSIM | 0.9439 | 0.9657 | 0.9711 | |

| Std. 0.1 | PSNR | 34.239 | 35.380 | 35.939 |

| SSIM | 0.9332 | 0.9483 | 0.9531 |

Methodology for Validation:

- A denoised 3D MRI dataset is used as a high-quality reference (ground truth).

- Two levels of simulated Gaussian noise (Standard Deviation 0.05 and 0.1) are added to this reference to create noisy input data.

- The noisy data is reconstructed using the three denoising networks ("Quick," "Strong," and "Large").

- PSNR and SSIM are computed between the denoised outputs and the original ground truth to quantify performance [2].

FAQ 3: How can I implement a noise-resistant deep learning model for point-of-care image classification?

Point-of-care imaging devices are often limited by environmental noise and require lightweight, robust models.

Solution: A Lightweight, Noise-Resistant Student Model [3] This approach uses a knowledge distillation framework where a compact "student" model learns from one or more powerful "teacher" models.

Experimental Protocol for Model Development:

- Model Design: A lightweight student model is built using a Shift MLP-based structure on its residual branches. This design captures multi-scale spatial features while reducing parameters and computational complexity.

- Multi-Teacher Distillation:

- An Auxiliary Teacher model uses unlabeled, noisy data for adaptive learning, enhancing the student model's robustness.

- A Global Teacher model transfers deep-feature knowledge to improve the student's classification accuracy.

- Training: The student model is trained to mimic the outputs and feature representations of both teachers, inheriting both robustness and accuracy.

Performance Outcomes [3]: The resulting model achieved a 38-fold reduction in parameters and an 11-fold reduction in computational complexity compared to traditional models, with an inference time of only 18.94 ms on a CPU. It maintained an average AUC of 83.00% in noisy environments, making it suitable for deployment on resource-constrained point-of-care devices.

Experimental Workflows

Workflow 1: Development and Validation of a Model-Based Noise Correction Algorithm

This workflow outlines the process for creating and testing a noise correction algorithm for quantitative CT perfusion, as described in the research [1].

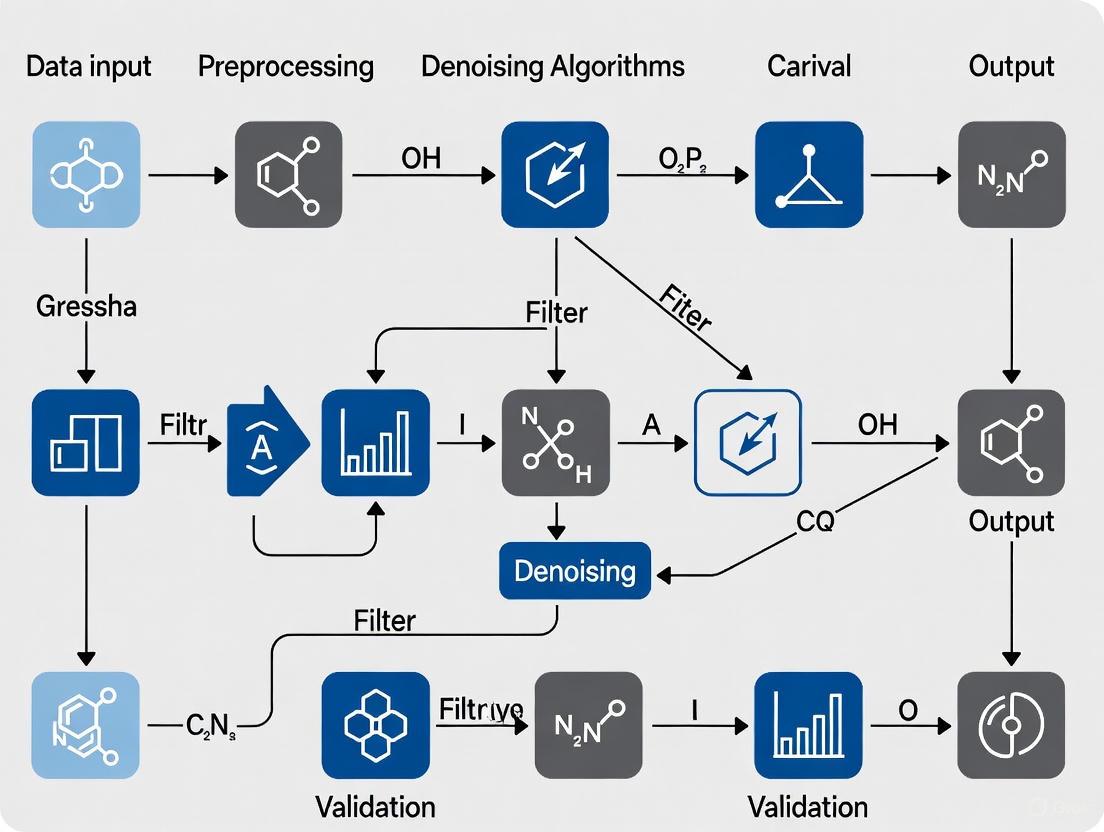

Workflow 2: Deep Learning-Based Medical Image Analysis Pipeline

This workflow illustrates a common pipeline for applying deep learning to medical image analysis, incorporating denoising and segmentation steps as referenced in the literature [4] [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and materials used in modern medical image denoising research.

| Item Name | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Digital Perfusion Phantoms (DPPs) [1] | Computer-generated models that simulate biological tissues and perfusion parameters. They provide a known ground-truth for quantitatively evaluating denoising algorithms without the ethical and practical constraints of patient data. |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [2] [4] | A class of deep learning models particularly effective for image data. They are used in denoising (e.g., Smart Noise Reduction) and segmentation tasks by learning to identify and extract relevant spatial features from noisy images. |

| Fully Convolutional Neural Networks (FCNNs) [4] | A variant of CNNs designed for dense prediction tasks like pixel-wise image segmentation. They can outperform traditional methods in accurately delineating anatomical structures (e.g., femur in DXA images) even in the presence of noise. |

| Knowledge Distillation Framework [3] | A training strategy where a compact, "lightweight" model (the student) is trained to mimic the behavior of a larger, more accurate model or ensemble of models (the teachers). This is crucial for developing noise-resistant models deployable on point-of-care devices. |

| Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) & Structural SIMilarity (SSIM) [2] | Two standard quantitative metrics for objectively evaluating the performance of denoising algorithms. PSNR measures the noise reduction level, while SSIM assesses the perceptual quality and structural integrity of the denoised image. |

In medical imaging research, the presence of noise is an unavoidable factor that significantly impacts quantitative analysis and diagnostic accuracy. A proper understanding of the fundamental noise types—Gaussian, Rician, and Poisson—is essential for developing effective denoising techniques and ensuring the reliability of experimental results. This guide provides a structured technical resource to help researchers troubleshoot common issues related to noise in medical images, framed within the context of advanced data denoising research.

Noise Characteristics and Identification

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, primary sources, and affected imaging modalities for the three common noise types.

| Noise Type | Probability Distribution | Primary Sources in Imaging | Commonly Affected Modalities | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian [5] [6] | Normal (Bell-curve) distribution | Electronic circuit noise, sensor heat [6] | CT, MRI (high SNR) [5] [6] | Additive; constant variance independent of signal intensity. |

| Rician [7] [8] | Non-Gaussian; derived from Gaussian complex data [7] | Inherent to MRI magnitude reconstruction from complex (real/imaginary) data [7] [9] | MRI (especially low SNR images like DWI) [8] | Signal-dependent; causes a positive bias in low-intensity regions (e.g., background) [7]. |

| Poisson [6] [10] | Poisson distribution | Quantum (photon) noise due to statistical nature of photon detection [6] [10] | X-ray, PET, SPECT, Scintigraphy [6] [10] | Signal-dependent; variance equals the mean signal intensity [10]. |

Experimental Protocols for Noise Handling and Denoising

Protocol: Bias Correction for Rician Noise in MRI Magnitude Data

This protocol addresses the non-zero mean and signal-dependent bias introduced by Rician noise, which is critical for accurate quantitative analysis in MRI [7].

- Application Context: Preprocessing of magnitude MRI data, particularly in low-SNR conditions (e.g., diffusion tensor imaging, functional MRI).

- Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Noise Power Estimation: Estimate the noise standard deviation (σ) from a background region of the magnitude image using the relationship derived from the Rayleigh distribution:

σ = mean(background) / √(π/2)[7]. - Bias Correction: Apply a correction to the entire image using the formula:

= √(M² - σ²), whereMis the measured magnitude value andÂis the corrected amplitude [7]. - Validation: Validate the correction by checking that the mean intensity in the background region approaches zero and that the signal distribution in homogeneous tissue regions becomes more symmetric.

- Noise Power Estimation: Estimate the noise standard deviation (σ) from a background region of the magnitude image using the relationship derived from the Rayleigh distribution:

Protocol: Denoising MRI with Pre-Smoothing Non-Local Means (PSNLM) Filter

This method effectively handles Rician noise by transforming it into additive noise, making it amenable to powerful filters like NLM [9].

- Application Context: Denoising brain MR images for improved segmentation, registration, or classification.

- Step-by-Step Methodology [9]:

- Transformation: Transform the noisy magnitude MRI (

M) using the Squared Magnitude method (M²) or a Variance-Stabilizing Transformation (VST) to make the noise approximately additive. - Pre-Smoothing: Apply a conventional spatial filter (e.g., a Gaussian filter) to the transformed image to create a "pre-smoothed" version for weight calculation.

- NLM Filtering: Apply the Non-Local Means filter to the transformed image, but compute the patch similarity weights using the pre-smoothed image from the previous step. This leads to more robust weight estimation.

- Inverse Transformation: Apply the inverse transformation (e.g., square root for the squared magnitude method) to the denoised data to obtain the final, unbiased denoised image.

- Transformation: Transform the noisy magnitude MRI (

Protocol: Handling Poisson Noise in Scintigraphic Images with SHINE

The Statistical and HEuristic Image Noise Extraction (SHINE) procedure is designed to reduce Poisson noise while preserving resolution and contrast [10].

- Application Context: Denoising low-count photon images in planar scintigraphy, SPECT, and PET.

- Step-by-Step Methodology [10]:

- Block Division: Divide the input image into small blocks (e.g., 4x4 pixels).

- Correspondence Analysis: Perform a correspondence analysis (a multivariate statistical technique) on these blocks.

- Factor Selection: For each block, reconstruct it using only its own "significant factors," which are selected using a statistical variance test designed to separate signal from noise.

- Image Reconstruction: Reassemble the denoised blocks to create the final output image. This method can improve the signal-to-noise ratio to a level comparable to an image acquired with twice the counts [10].

Research Workflows and Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for identifying and addressing different noise types in medical images.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Denoising Algorithms

The table below catalogs key algorithms and their applications for mitigating different noise types in medical images.

| Tool/Algorithm | Primary Noise Target | Function and Mechanism | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| BM3D (Block-Matching 3D) [5] | Gaussian | Groups similar 2D image patches into 3D arrays for collaborative filtering in the transform domain. | Considered state-of-the-art for Gaussian noise; can be computationally intensive [5]. |

| Non-Local Means (NLM) [9] | Additive (Gaussian) | Averages pixels based on the similarity of their surrounding patches across the entire image, not just local neighborhood. | Excellent edge preservation; requires modification (e.g., PSNLM) for Rician noise [9]. |

| Variance-Stabilizing Transform (VST) [9] | Rician, Poisson | Transforms data so that the noise variance becomes constant (stabilized), allowing application of filters designed for additive Gaussian noise. | Critical pre-processing step for handling signal-dependent noise; must be followed by an inverse transform [9]. |

| SHINE [10] | Poisson | Uses statistical factor analysis on image blocks to separate and extract noise while preserving signal texture and contrast. | Specifically designed for low-count scintigraphic images; helps reduce acquisition time or dose [10]. |

| DnCNN [5] | Gaussian (general) | A deep learning model that learns to predict the noise residual from a noisy image. | Effective for various noise levels; performance depends on training data [5]. |

| Bias Correction (M² - σ²) [7] | Rician | Simple algebraic correction to reduce the bias in magnitude MRI data, as described in Protocol 2.1. | Simple and effective for quantitative MRI; requires accurate estimation of σ [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: My MRI segmentation algorithm performs poorly in low-signal regions. Could noise be the cause?

- A: Yes, this is a classic issue. In MRI magnitude images, noise is Rician, not Gaussian. In low-signal regions, this creates a positive bias, meaning the measured intensity is higher than the true signal. This bias can cause segmentation algorithms to misclassify background or dark tissue regions [7]. Troubleshooting Tip: Implement the simple bias correction protocol (

= √(M² - σ²)) as a preprocessing step and reevaluate your segmentation performance [7].

- A: Yes, this is a classic issue. In MRI magnitude images, noise is Rician, not Gaussian. In low-signal regions, this creates a positive bias, meaning the measured intensity is higher than the true signal. This bias can cause segmentation algorithms to misclassify background or dark tissue regions [7]. Troubleshooting Tip: Implement the simple bias correction protocol (

Q2: Why does my denoising model, trained on one scanner, perform poorly on data from another institution?

- A: This is often a problem of generalization. Different scanner models and acquisition parameters introduce variations that can be viewed as a form of "noise" by an AI model. If the model was only trained on clean, homogeneous data from one source, it will fail when presented with these new variations [11]. Troubleshooting Tip: Use data augmentation during training. Deliberately adding Gaussian noise and other artifacts to your training data can teach the model to focus on essential diagnostic features and ignore irrelevant scanner-specific variations, making it more robust [11] [12].

Q3: Is the noise in my CT/X-ray images Gaussian or Poisson?

- A: It is typically a combination of both, known as Poisson-Gaussian noise. The dominant source is Poisson (quantum) noise, which is signal-dependent. However, the readout noise from the electronic sensors is often Gaussian and additive [13] [6]. Troubleshooting Tip: For effective denoising, you need methods specifically designed for this mixed-noise scenario. Look for algorithms that incorporate a Poisson-Gaussian model or use a Variance-Stabilizing Transform (VST) to convert the noise to be approximately Gaussian before applying a standard denoiser [13].

Q4: I am working with diffusion-weighted MRI (DWI). Why is denoising so challenging?

- A: DWI often has a very low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which magnifies the problems of Rician noise. Furthermore, noise in modern multi-coil systems can be spatially variable, meaning its power is not uniform across the image. Applying a single denoising parameter to the entire image is therefore ineffective [8]. Troubleshooting Tip: Employ a denoising algorithm that accounts for spatially variable noise. These methods estimate and correct for noise on a voxel-by-voxel basis, which is crucial for accurate signal recovery in low-SNR applications like DWI [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Common Denoising Problems

Issue 1: Over-smoothing and Loss of Fine Details

- Problem: After denoising, the image appears blurry, and fine textures or subtle anatomical structures are lost.

- Cause: This is often caused by using denoising algorithms with overly aggressive filtering parameters or algorithms that are not designed to preserve high-frequency details, which constitute edges and textures [5].

- Solution:

- Switch Algorithm: Consider moving from simple spatial filters (e.g., Gaussian, median) to more advanced non-local or deep learning-based methods. For instance, Non-Local Means (NLM) excels at preserving repetitive structures and edges by comparing patches from across the entire image [14].

- Adjust Parameters: Reduce the strength of the denoising filter or adjust the threshold parameters. For transform-domain methods, carefully tune thresholding parameters to preserve more high-frequency components [5].

- Validate with Metrics: Use the Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) to quantitatively ensure structural information is being maintained post-denoising [5] [15].

Issue 2: Inadequate Noise Removal

- Problem: Significant noise remains in the image after processing, hindering diagnostic clarity.

- Cause: The denoising algorithm may be too weak for the noise level, or the parameters are not optimized for the specific noise characteristics of your imaging modality [5] [15].

- Solution:

- Re-evaluate Noise Level: Accurately estimate the global noise level in your image. Some advanced methods, like the one using the Marchenko-Pastur law, can automate this process for Gaussian noise [14].

- Choose a Stronger Algorithm: For moderate to high noise levels, BM3D has been shown to consistently outperform other algorithms, achieving high PSNR and SSIM [5]. For very high noise levels, deep learning methods like DnCNN may be more robust [5].

- Pre-process Input: For deep learning models, integrating preprocessing steps like image sharpening and K-means clustering can improve noise identification and lead to more effective denoising [16].

Issue 3: Introduction of Artifacts or Unrealistic Textures

- Problem: The denoised image contains new patterns, blurring, or textures that were not present in the original data.

- Cause: This is a known challenge with some deep learning models, which may "hallucinate" features learned from training data or create a "cartoon-like" appearance when over-trained [17] [15].

- Solution:

- Inspect a Validation Set: Always visually inspect denoising results on a subset of your data. Artifacts are often easily spotted by a trained eye.

- Use a Hybrid Approach: Implement a hybrid framework that combines different techniques. For example, a method using adaptive clustering followed by PCA thresholding and a final NLM refinement can balance noise removal with natural texture preservation [14].

- Employ Perceptual Metrics: Use no-reference image quality metrics like Naturalness Image Quality Evaluator (NIQE) and Blind/Referenceless Image Spatial Quality Evaluator (BRISQUE) to detect unrealistic outputs [5].

Issue 4: Poor Generalization Across Modalities or Anatomies

- Problem: A model trained on one type of medical image (e.g., brain MRI) performs poorly on another (e.g., liver CT).

- Cause: The model has learned features specific to its training dataset and lacks generalizability, a common issue with deep learning models [17] [15].

- Solution:

- Use Diverse Training Data: Train models on large, diverse datasets encompassing multiple imaging modalities, anatomies, and noise levels [15].

- Fine-tune Models: Transfer learning can be used to adapt a pre-trained model to a new, specific imaging domain with a smaller amount of data [17].

- Leverage Modality-Agnostic Algorithms: For some applications, high-performance traditional algorithms like BM3D can be effective across different modalities without retraining [5].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most critical metrics for evaluating denoising performance in medical images? While Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) is a common metric for quantifying error, it does not always correlate with diagnostic quality [5] [15]. The most critical evaluation should combine:

- Structural Similarity Index (SSIM): Measures perceptual image quality and structural preservation [5] [15].

- Visual Inspection by Experts: Essential for identifying the preservation of clinically relevant details and the absence of artifacts.

- Task-based Assessment: The ultimate test is whether the denoised image improves performance in downstream tasks like tumor segmentation or classification.

Q2: How do I choose between traditional and deep learning-based denoising methods? The choice involves a trade-off between performance, computational cost, and data availability.

- Traditional Methods (e.g., NLM, BM3D, Wavelet): Are often less computationally intensive and do not require training data. They are well-understood and can be a good choice for projects with limited data or computational resources [5] [17]. BM3D is often a dependable choice for low-to-moderate noise levels [5].

- Deep Learning Methods (e.g., DnCNN, GANs): Typically offer state-of-the-art performance and can better handle complex noise patterns [5] [17]. However, they require large, high-quality labeled datasets for training and significant computational power. They also risk poor generalization if not trained on representative data [17] [15].

Q3: My dataset is small. What denoising strategies can I use? Deep learning models generally require large datasets, but several strategies can help:

- Pre-trained Models: Use models pre-trained on large natural or medical image datasets and fine-tune them on your small dataset.

- Data Augmentation: Artificially expand your dataset using rotations, flips, and other transformations.

- Self-Supervised Learning: Employ techniques that learn from a single noisy image or generate training pairs from noisy data alone, reducing the need for clean ground-truth data [5] [14].

- Robust Traditional Algorithms: Opt for high-performing traditional algorithms like BM3D or hybrid methods that do not require extensive training data [5] [18].

Q4: How can I ensure my denoising process is reproducible for my research?

- Document Parameters: Meticulously record all algorithm parameters, including filter sizes, threshold values, and noise level estimates.

- Version Control: Use version control for any custom code and for the specific implementation of the denoising algorithms you use.

- Standardize Workflows: Establish a standard operating procedure (SOP) for image preprocessing and denoising in your lab.

- Use Public Datasets for Benchmarking: Validate your denoising pipeline on public benchmark datasets to allow for direct comparison with other methods.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Detailed Methodology: Hybrid Adaptive Clustering and Non-Local Means

This protocol is based on a state-of-the-art approach for detail-preserving denoising of CT and MRI images [14].

1. Objective: To effectively remove Gaussian noise while preserving fine textures and structural boundaries in medical images.

2. Step-by-Step Workflow: 1. Noise Level Estimation: Analyze the statistical distribution of eigenvalues from matrices of randomly sampled image patches. Use the Marchenko-Pastur law from random matrix theory to accurately estimate the global Gaussian noise variance. 2. Adaptive Patch Clustering: Extract small, overlapping patches from the noisy image. Use an adaptive clustering technique to group these patches based on texture and edge features. This step creates clusters of similar patches for localized processing. 3. Cluster-wise PCA Thresholding: For each cluster: * Arrange the similar patches into a matrix. * Perform Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) on this matrix. * Apply hard thresholding to the singular values based on the MP law to obtain a low-rank approximation, removing noise-dominated components. * Use a Linear Minimum Mean Square Error estimator on the PCA coefficients to further suppress residual noise. 4. Image Reconstruction: Reconstruct the denoised patches from each cluster and aggregate them back into a full image, handling overlapping regions by averaging. 5. Non-Local Means Refinement: Apply a final Non-Local Means (NLM) filter to the reconstructed image. The NLM computes a weighted average of pixels across the entire image, giving higher weight to pixels in similar neighborhoods, which enhances noise reduction and preserves edges and textures.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this multi-stage denoising process:

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Denoising Algorithms

The following table summarizes objective metrics for various denoising algorithms as reported in comparative studies [5] [18] [16]. These metrics are crucial for evaluating the trade-off between noise reduction (PSNR) and structural preservation (SSIM).

Table 1: Denoising Algorithm Performance Metrics

| Algorithm | Type | Key Principle | Reported PSNR (dB) | Reported SSIM | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM3D [5] | Traditional (Transform) | Collaborative filtering in 3D transform domain | High (Consistently top) | High (Consistently top) | Low-to-moderate noise; general use |

| Proposed Hybrid (AMF+MDBMF) [18] | Traditional (Hybrid Spatial) | Adaptive median filtering & decision-based recovery | Improvement up to 2.34 dB | Improvement up to 0.07 | High-density salt-and-pepper noise |

| Energy-Efficient Autoencoder [16] | Deep Learning (CNN) | Preprocessing (sharpening & clustering) before autoencoder | 28.14 (from 21.52 baseline) | 0.869 (from 0.762 baseline) | Computationally constrained environments |

| DnCNN [5] | Deep Learning (CNN) | Deep convolutional neural network learning residual noise | Competitive, especially at high noise | Competitive, especially at high noise | Handling significant noise variations |

| Non-Local Means (NLM) [14] | Traditional (Spatial) | Averages similar patches from across the image | Not Specified | Not Specified | Preserving repetitive structures & edges |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Medical Image Denoising Research

| Item / Algorithm | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| BM3D (Block-Matching 3D) [5] [17] | A high-performance traditional algorithm that groups similar 2D image patches into 3D arrays for collaborative filtering. | An excellent benchmark algorithm. Does not require training data and is effective for Gaussian noise. Can be computationally heavy. |

| DnCNN (Deep Convolutional Neural Network) [5] [15] | A deep learning model trained to predict the residual noise (difference between noisy and clean image) rather than the clean image directly. | Requires a large dataset of noisy/clean image pairs for training. Often delivers state-of-the-art results but needs significant computational resources. |

| Non-Local Means (NLM) [17] [14] | Reduces noise by averaging pixels based on the similarity of their surrounding patches from the entire image, not just the local neighborhood. | Excellent at preserving fine details and textures. Computationally intensive for large images without optimization. |

| Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) [17] [15] | Uses a generator network to create denoised images and a discriminator to critique them, leading to highly realistic outputs. | Can produce very sharp images but is challenging to train and may introduce hallucinations. Used in 30% of DL-based CT denoising studies [17]. |

| Wavelet Transform [5] [17] | Decomposes an image into different frequency sub-bands. Noise is removed by thresholding the coefficients in these bands before reconstruction. | Effective for separating signal from noise. The choice of wavelet and thresholding rule is critical for performance. |

| Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) [5] [15] | A perceptual metric that compares the luminance, contrast, and structure between two images to evaluate denoising quality. | More aligned with human perception than PSNR. Essential for validating the preservation of anatomical structures. |

| Marchenko-Pastur Law [14] | A principle from random matrix theory used to accurately estimate the global noise level in an image by analyzing the eigenvalue distribution of patch matrices. | Provides a robust, data-driven method for noise estimation, which is a critical first step for many adaptive denoising algorithms. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary clinical risks of a noisy medical image? Noise in medical images obscures crucial anatomical details, which can directly lead to two major clinical consequences:

- Misinterpretation and Diagnostic Errors: Blurred borders, reduced contrast, and obscured minute information can hinder the detection of subtle pathologies, such as early-stage tumors or small lesions, potentially leading to missed diagnoses or misinterpretation [5].

- Increased Patient Radiation Exposure: In cases where image quality is non-diagnostic, clinicians may order additional scans to clarify findings. For modalities like CT, this results in higher cumulative radiation doses for patients [5].

Q2: My denoising algorithm is making images too soft and blurry. How can I preserve finer diagnostic details? This is a classic trade-off between noise removal and feature preservation. We recommend:

- Algorithm Selection: Choose advanced algorithms designed for detail preservation. Studies show that BM3D consistently outperforms others at low and moderate noise levels, achieving high structural similarity (SSIM) [5]. For high noise levels, deep learning-based methods like DnCNN are better suited [5].

- Advanced Architectures: Implement modern networks that use mechanisms like Optimal Attention Blocks (OAB). These blocks intelligently focus on relevant features and noise components, ensuring significant structures are highlighted while noise is minimized [19]. A Pyramidal Network structure can also help by analyzing and integrating image features across different scales, capturing both fine and coarse details [19].

Q3: I lack paired clean-noisy image data for training. Are there effective denoising solutions? Yes, several data-free and self-supervised techniques are available:

- Noise2Noise Framework: This approach trains a model using pairs of noisy images without requiring clean ground truth data [20].

- Lightweight Data-Free Models: Methods like Noise2Detail (N2D) use an innovative multistage pipeline that disrupts noise correlations and recaptures fine details directly from the noisy input, requiring no training data and minimal computational resources [20].

- Distribution-Based Schemes: Frameworks like DCDS use transfer learning and statistical modeling to distinguish between normal and noisy pixels, effectively reducing noise without large, paired datasets [21].

Q4: How can I quantitatively validate that my denoised image is fit for clinical use? Rely on a combination of objective metrics to assess different aspects of image quality:

- Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR): Measures the noise reduction level. A higher PSNR (e.g., improvements of 2-3 dB) generally indicates better noise suppression [19] [21].

- Structural Similarity Index (SSIM): Assesses how well the structural integrity of the original image is preserved. This is critical for ensuring diagnostic features remain intact [5] [19].

- Perceptual Quality Metrics: For a more comprehensive assessment, use metrics like NIQE, BRISQUE, and LPIPS to evaluate the visual perceptual quality of the output [5] [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Loss of Subtle Pathologies Post-Denoising

Potential Cause: The denoising algorithm is over-smoothing the image, treating low-contrast pathological features as noise.

| Troubleshooting Step | Action/Recommendation |

|---|---|

| 1. Verify Algorithm Choice | Switch from simple filters (Gaussian, median) to more advanced, detail-preserving algorithms like BM3D or a well-designed Denoising Convolutional Neural Network (DnCNN) [5]. |

| 2. Tune Hyperparameters | Adjust the strength or weight of the denoising process. Reduce the aggression level to prevent the loss of fine, high-frequency details that may correspond to critical diagnostic information [5]. |

| 3. Implement an Attention Mechanism | Integrate an Optimal Attention Block (OAB) into your model. This mechanism uses optimization algorithms to help the network focus on important features and suppress noise more intelligently [19]. |

Problem: Inconsistent Performance Across Different Imaging Modalities

Potential Cause: The noise model your algorithm was trained on does not match the real-world noise in the target modality (e.g., applying a Gaussian denoiser to Poisson-noised images).

| Troubleshooting Step | Action/Recommendation |

|---|---|

| 1. Identify Noise Model | Determine the dominant noise type in your target modality (e.g., Rician for MRI, Poisson for CT). Artificially induce this specific noise type for model training and validation [5] [19]. |

| 2. Use a Robust Framework | Employ a flexible framework like the Distribution-Based Compressed Denoising Scheme (DCDS), which uses transfer learning and statistical analysis to adapt to different noise distributions without requiring full retraining [21]. |

| 3. Adopt a Data-Free Method | For rare modalities with no clean data, use a zero-shot method like Noise2Detail (N2D), which is trained directly on the noisy image itself and is not dependent on a pre-defined noise model [20]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Denoising Algorithms for Clinical Use

This protocol outlines how to compare different denoising algorithms to select the most suitable one for a specific clinical task.

1. Objective: To evaluate and compare the performance of multiple denoising algorithms on medical images using standardized quantitative metrics and qualitative assessment. 2. Materials:

- Datasets: Use standardized medical image datasets (e.g., CHASEDB1, Lumbar Spine MRI) [19].

- Algorithms for Testing: Select a range of algorithms, including BM3D, DnCNN, NLM, and WNNM [5].

- Software: Python with libraries such as PyTorch/TensorFlow for deep learning models and OpenCV for traditional algorithms.

3. Method:

- Data Preparation: Artificially introduce known types and levels of noise (Gaussian, Speckle, Poisson) into clean images to create a controlled test set [19].

- Apply Denoising: Process the noisy images with each selected algorithm.

- Quantitative Analysis: Calculate PSNR, SSIM, and perceptual metrics (NIQE, BRISQUE) between the denoised images and the original clean ground truth [5].

- Qualitative Analysis: Have clinical experts blindly rate the denoised images for diagnostic quality, feature preservation, and absence of artifacts. 4. Analysis: Compare results to determine the best-performing algorithm for your specific imaging modality and diagnostic task.

Protocol 2: Implementing a Lightweight, Data-Free Denoising Pipeline

This protocol is for scenarios where clean training data is unavailable and computational resources are limited.

1. Objective: To apply the Noise2Detail (N2D) pipeline for effective denoising using only a single noisy image. 2. Materials:

- Input: A single noisy medical image.

- Model: A pre-defined ultra-lightweight, three-layer Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) as per the N2D architecture [20].

3. Method:

- Training Phase:

- Use the Noise2Noise framework. The denoised image (or a downsampled version of the noisy input) is used as the input, and the original noisy image is set as the target.

- This unconventional setup forces the model to learn to reconstruct missing signal details rather than replicate noise [20].

- Spatial Disruption: Apply pixel-shuffle downsampling to disrupt spatial correlations in the noise patterns, creating intermediate smooth structures [20].

- Detail Refinement: The model is then refined to recapture and enhance fine anatomical details directly from the original noisy input [20]. 4. Output: A high-quality denoised image suitable for diagnostic use, generated with minimal computational overhead.

- Training Phase:

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of Denoising Algorithms on Medical Images

Table comparing PSNR (dB) and SSIM performance of various algorithms at different noise levels. Higher values are better.

| Algorithm | Type | Low Noise PSNR | Low Noise SSIM | High Noise PSNR | High Noise SSIM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM3D | Block-Matching & Filtering | High | High | Moderate | Moderate [5] |

| DnCNN | Deep Learning | High | High | High | High [5] |

| OABPDN | Attention-based Deep Learning | ~2-3% improvement over state-of-the-art models in PSNR and SSIM [19] | |||

| DCDS | Transfer Learning / Statistical | Improves PSNR across 24-32 dB range | N/R | >82% noise reduction rate in optimal conditions [21] | |

| N2D (Noise2Detail) | Lightweight, Data-Free | Competitive with data-free techniques | Competitive with data-free techniques | High quality, detail-preserving | High quality, detail-preserving [20] |

N/R: Not explicitly reported in the provided search results.

Table 2: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials for Denoising Research

A list of key computational "reagents" and their functions in medical image denoising experiments.

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function & Application in Denoising |

|---|---|

| BM3D (Block-Matching 3D) | A high-performance non-local algorithm that groups similar 2D image patches into 3D data arrays for collaborative filtering. Excellent for low/moderate noise [5]. |

| DnCNN (Denoising Convolutional Neural Network) | A deep learning model that uses CNN layers to learn and remove noise from images. Effective for handling significant noise variations [5]. |

| Optimal Attention Block (OAB) | A module integrated into neural networks that uses optimization algorithms (e.g., Cuckoo Search) to intelligently weight channel features, focusing the model on relevant structures and noise components [19]. |

| Noise2Noise Framework | A training paradigm that enables model learning from pairs of noisy images alone, eliminating the need for clean ground-truth data [20]. |

| Cuckoo Search Optimization (CSO) | A metaheuristic optimization algorithm used to find the optimal parameters for components like the Optimal Attention Block, improving denoising efficiency [19]. |

| Pixel-Shuffle Downsampling | An operation used in pipelines like N2D to disrupt the spatial correlation of noise, creating a smoother image that is later refined to recapture details [20]. |

Experimental and Clinical Workflow Visualization

Clinical Consequences of Noisy Medical Images

Noise2Detail Data-Free Denoising

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the fundamental differences between PSNR, SSIM, and perceptual quality metrics? PNSR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) and SSIM (Structural Similarity Index) are full-reference metrics that require a clean ground truth image for comparison, whereas many perceptual quality metrics are no-reference and assess image quality based on statistical properties of the image itself [22]. PSNR is a pixel-based error metric calculated as the ratio between the maximum possible power of a signal and the power of corrupting noise [15], while SSIM considers luminance, contrast, and structure to provide a more perceptually meaningful assessment [15]. Perceptual quality metrics like NIQE, BRISQUE, and PIQE evaluate quality without a reference image by assessing naturalness and statistical deviations [5].

Q2: Why might a denoising algorithm achieve high PSNR but poor performance in clinical evaluation? This discrepancy occurs because PSNR primarily measures pixel-level fidelity rather than preservation of clinically relevant features [22]. A denoising algorithm might effectively smooth away noise (improving PSNR) but simultaneously remove subtle pathological details crucial for diagnosis [5] [15]. This is particularly problematic in medical imaging where subtle textures, edges, and low-contrast features often carry critical diagnostic information that PSNR does not adequately capture [22].

Q3: How should researchers select appropriate metrics for evaluating medical image denoising? Metric selection should be guided by the specific clinical task and image modality [15]. For comprehensive evaluation, researchers should employ a multi-metric approach combining PSNR/SSIM with task-specific perceptual assessments [5] [22]. When ground truth is unavailable, no-reference metrics like NIQE and BRISQUE can provide insights, but their limitations in detecting localized anatomical errors must be considered [22]. For denoising algorithms intended to support specific clinical tasks (e.g., tumor segmentation), downstream task performance should be the ultimate validation [22].

Q4: What are the limitations of no-reference metrics for medical image evaluation? No-reference metrics exhibit significant limitations in medical contexts, particularly insensitivity to localized anatomical alterations that are clinically crucial [22]. These metrics may yield misleadingly favorable scores for images with memorized training data or mode collapse in generative models [22]. They often fail to detect distorted tumor boundaries or other morphological inaccuracies that would impact diagnostic utility, potentially creating patient safety risks if used as the sole evaluation method [22].

Q5: How can researchers implement efficient evaluation pipelines for large-scale denoising studies? Distributed evaluation frameworks can significantly accelerate metric computation for large datasets [23]. Leveraging multi-GPU configurations with optimized parallel processing (e.g., PyTorch's DistributedDataParallel) can reduce evaluation time by over 60% compared to single-GPU setups [23]. Automated scripting to compute multiple metrics simultaneously (PSNR, SSIM, perceptual metrics) across denoised image batches ensures consistent and efficient assessment [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High PSNR/SSIM But Poor Visual Quality in Denoised Images

Problem: Denoised medical images achieve strong quantitative metrics but appear oversmoothed or lack clinically important textures.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Root Cause: The denoising algorithm is over-prioritizing noise removal at the expense of structural preservation, and PSNR/SSIM alone are insufficient to capture this deficiency [5] [22]

- Solution 1: Incorporate perceptual quality metrics (NIQE, BRISQUE, PIQE) that better align with human visual assessment [5]

- Solution 2: Implement task-specific validation by testing the denoised images in downstream clinical applications (e.g., segmentation accuracy, pathology detection) [22]

- Solution 3: Adjust the denoising algorithm's loss function to balance PSNR/SSIM with perceptual losses or feature preservation constraints [19]

Verification Protocol:

- Compute a comprehensive metric suite including PSNR, SSIM, and at least two perceptual metrics [5]

- Conduct a limited expert evaluation where radiologists rate image quality on a 5-point scale [22]

- Check correlation between metrics and expert scores - good algorithms should perform well across multiple assessment methods [22]

Issue: Inconsistent Metric Values Across Different Noise Levels

Problem: Metric performance varies significantly across low, moderate, and high noise conditions, making algorithm comparison difficult.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Root Cause: Different metrics have varying sensitivity to noise levels, and some algorithms perform better at specific noise ranges [5]

- Solution 1: Establish noise-level specific benchmarks based on your imaging modality and typical clinical scenarios [5] [15]

- Solution 2: For variable noise environments, prioritize algorithms that maintain consistent performance across noise levels rather than excelling at only one range [5]

- Solution 3: Implement adaptive denoising that selects parameters based on estimated noise level [24]

Verification Protocol:

- Artificially corrupt clean images with known noise levels (e.g., Gaussian noise with σ=10, 20, 30) [23]

- Evaluate denoising performance separately for each noise level [5]

- Calculate metric consistency as the standard deviation of performance across noise levels - lower values indicate more robust algorithms [5]

Issue: Computational Bottlenecks in Metric Evaluation

Problem: Calculating comprehensive metrics for large medical image datasets requires prohibitive computational time and resources.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Root Cause: Perceptual metrics and full-volume evaluations can be computationally intensive, especially for 3D medical images [23]

- Solution 1: Implement distributed evaluation using multi-GPU setups with PyTorch's DistributedDataParallel [23]

- Solution 2: Use automated mixed precision (AMP) to accelerate computations with minimal accuracy impact [23]

- Solution 3: Employ strategic sub-sampling by evaluating metrics on representative image subsets or slices rather than full datasets [22]

Verification Protocol:

- Compare metric values between full evaluation and sub-sampled approaches to ensure representativeness

- Benchmark computation time across different hardware configurations [23]

- Validate that mixed precision implementation does not significantly alter metric values (e.g., <1% difference) [23]

Quantitative Metric Comparison Tables

Table 1: Performance Metrics for Denoising Algorithms Across Modalities

| Algorithm | PSNR (dB) | SSIM | Computational Complexity (s) | Optimal Noise Level | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM3D [5] | 32.1-35.8 | 0.91-0.94 | 0.8-1.2 | Low-Moderate | Excellent detail preservation |

| DnCNN [5] | 31.8-36.2 | 0.90-0.95 | 0.3-0.6 | Moderate-High | Deep learning advantage |

| Gaussian Pyramid [25] [26] | 34.2-36.8 | 0.92-0.94 | 0.004-0.006 | Various | Superior computational efficiency |

| U-Net++ [23] | 33.5-37.1 | 0.93-0.96 | 0.4-0.7 | Low-High | Enhanced structural fidelity |

| Optimal Attention Block [19] | ~2-3% improvement over baselines | ~2-3% improvement over baselines | Moderate-High | Various | Intelligent feature focusing |

Table 2: Medical Image Noise Types and Metric Sensitivity

| Noise Type | Common Sources | PSNR Sensitivity | SSIM Sensitivity | Perceptual Metric Sensitivity | Affected Modalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian [15] | Electronic circuits, sensor heat | High | Moderate | Moderate-High | X-ray, CT, MRI |

| Rician [15] | MRI acquisition | Moderate | High | High | MRI |

| Poisson [15] | Quantum noise in photon counting | Moderate-High | Moderate | Moderate | CT, PET, low-dose X-ray |

| Salt & Pepper [15] [24] | Transmission errors, sensor faults | High | High | High | All digital modalities |

| Speckle [15] | Coherent imaging systems | Moderate | High | High | Ultrasound |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Denoising Algorithm Evaluation

Purpose: Systematically evaluate and compare medical image denoising algorithms using multiple quality metrics.

Materials and Setup:

- Dataset: Curated medical images with paired clean and noisy samples [23]

- Hardware: Multi-GPU workstation for distributed computation [23]

- Software: Python with PyTorch, OpenCV, scikit-image for metric computation [23]

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Pre-process images to consistent resolution (e.g., 256×256 for 2D, 128×128×128 for 3D) [23]

- Noise Introduction: For ground truth studies, add known noise types and levels to clean images [23]

- Algorithm Application: Process noisy images through each denoising algorithm with optimized parameters [5]

- Metric Computation: Calculate PSNR, SSIM, and perceptual metrics for all output images [5] [15]

- Statistical Analysis: Perform paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests to determine significant differences [25] [26]

Validation Steps:

- Verify metric implementation using standardized test images with known values

- Ensure consistent intensity normalization across all images [23]

- Confirm that results are statistically significant across multiple image samples [25]

Protocol 2: Clinical Relevance Validation Framework

Purpose: Bridge the gap between quantitative metrics and clinical utility of denoised medical images.

Materials and Setup:

- Clinical Dataset: Images with verified pathological findings [22]

- Evaluation Platform: Web-based interface for expert rating [22]

- Task Pipeline: Pre-trained segmentation/classification models for downstream task evaluation [22]

Procedure:

- Expert Evaluation Setup: Prepare blinded image sets with randomized presentation of original and denoised images [22]

- Rating Protocol: Define specific evaluation criteria (diagnostic confidence, feature visibility, artifact presence) using standardized scales [22]

- Task Performance Assessment: Measure accuracy of downstream tasks (e.g., segmentation, classification) on denoised versus original images [22]

- Correlation Analysis: Compute correlation coefficients between quantitative metrics and expert ratings/task performance [22]

Validation Steps:

- Assess inter-rater reliability among multiple experts [22]

- Validate that downstream task models perform comparably on denoised versus original images [22]

- Ensure clinical evaluations are ethically approved and follow relevant guidelines [22]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Medical Image Denoising Research

| Tool/Platform | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| PyTorch DDP [23] | Distributed training | Large-scale denoising experiments | Multi-GPU support, reduced training time |

| Automatic Mixed Precision [23] | Computational acceleration | Memory-intensive models | Faster computation, minimal accuracy loss |

| U-Net++ Architecture [23] | Denoising model | Medical image restoration | Nested skip connections, superior structural fidelity |

| Gaussian Pyramid [25] [26] | Multi-scale denoising | Real-world noise reduction | Multi-scale processing, computational efficiency |

| Optimal Attention Block [19] | Feature emphasis | Detail-preserving denoising | Adaptive feature weighting, cuckoo search optimization |

| BRISQUE/NIQE [5] | No-reference quality assessment | Real-world evaluation | No ground truth needed, perceptual alignment |

Metric Relationships and Evaluation Workflow

Metric Evaluation Decision Workflow

Key Experimental Design Considerations

When designing experiments for medical image denoising evaluation, several critical factors ensure meaningful and clinically relevant results:

Modality-Specific Validation: Different imaging modalities (MRI, CT, X-ray, ultrasound) have distinct noise characteristics and clinical requirements. Always validate denoising performance specifically for your target modality [15]

Clinical Task Alignment: Choose evaluation metrics that correlate with your intended clinical application. For tumor detection tasks, prioritize metrics sensitive to boundary preservation and contrast maintenance [22]

Computational Constraints: Balance metric comprehensiveness with practical computational requirements, especially for large-scale 3D medical images [23]

Statistical Robustness: Ensure adequate sample sizes and appropriate statistical tests to support claims of algorithmic superiority [25] [26]

The most effective evaluation strategy combines quantitative metrics with clinical relevance assessment, acknowledging that numerical superiority alone does not guarantee diagnostic utility [22].

From Traditional Filters to Generative AI: A Landscape of Denoising Methodologies

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when implementing classic spatial and transform domain filters for medical image denoising. The content supports thesis research on data denoising techniques, providing clear protocols and solutions for scientists and drug development professionals.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My bilateral filter is producing over-smoothed results, blurring critical diagnostic features. What could be the cause?

A1: Over-smoothing in bilateral filtering typically occurs due to improper parameter selection. The bilateral filter smoothes images while preserving edges by combining spatial (geometric) closeness and photometric similarity. Review these parameters:

- Spatial Sigma (σd): Controls the influence of neighboring pixels based on their geometric distance. A value that is too large will include too many pixels from heterogeneous regions, causing excessive blurring. For most medical images, start with a value between 1 and 3.

- Range Sigma (σr): Controls the influence of neighboring pixels based on their intensity difference. A value that is too large reduces the filter's edge-preserving capability. Start with a value proportional to the image's intensity range (e.g., 10-15% of the total range). Troubleshooting Tip: Systematically reduce σr while keeping σd small. This ensures that only pixels with very similar intensities contribute to the smoothing, thereby preserving edges. Computational complexity can be high, but this preserves edges more effectively than large kernel Gaussian filters [27] [28].

Q2: How do I select the most appropriate wavelet family and threshold function for denoising an MRI with Rician noise?

A2: Wavelet selection depends on the image characteristics and the noise properties. The denoising efficacy stems from the tendency of noise to spread across high-frequency sub-bands (LH, HL, HH), while important image structures are concentrated in the LL sub-band and strong coefficients in the detail sub-bands [29].

- Wavelet Family: For medical images like MRI, Daubechies (db4), Coiflets (coif4), or Symlets (sym4) are often preferred. These wavelets offer a good trade-off between smoothness and localization, reducing artifacts compared to simpler wavelets like Haar [29] [25].

- Threshold Function: The choice of threshold function is critical. The table below summarizes common functions [29] [30].

Table: Common Wavelet Thresholding Functions

| Threshold Name | Function | Best Use Case | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hard | $θ_H(x) = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } | x | ≤ δ \ x & \text{if } | x | > δ \end{cases}$ | Environments where strict coefficient retention is needed; can cause oscillatory artifacts [29] [30]. | ||

| Soft | $θ_S(x) = \begin{cases} 0 & \text{if } | x | ≤ δ \ \text{sgn}(x)( | x | -δ) & \text{if } | x | > δ \end{cases}$ | General-purpose denoising; can lead to edge blurring [29] [30]. |

| Smooth Garrote | $θ_{SG}(x) = \dfrac{x^{2n+1}}{x^{2n}+δ^{2n}}$ | A compromise between hard and soft thresholding, offering smoother transition [29]. |

For Rician noise in MRI, an adaptive thresholding approach that incorporates a linear prediction factor to minimize the mean squared error between the noisy and original image characteristics has shown significant improvements in metrics like PSNR and SSIM [30].

Q3: Why would I choose a transform domain method like Wavelet over a spatial method like Gaussian filtering?

A3: The choice hinges on the trade-off between noise reduction and the preservation of fine anatomical details.

- Gaussian Filtering (Spatial Domain): A linear low-pass filter that is computationally efficient and effective at suppressing high-frequency noise. Its primary limitation is that it uniformly smoothes across edges, often blurring crucial diagnostic details and reducing image sharpness [15] [27] [28].

- Wavelet Transform (Transform Domain): Provides multi-resolution analysis, capturing both coarse structures and fine details. It allows for non-linear processing (e.g., thresholding) of frequency components, which can remove noise more effectively while preserving edges and textures that are critical for diagnosis [29] [30].

In practice, a block-based Discrete Fourier Cosine Transform (DFCT) approach has been shown to consistently outperform a global DWT approach across various noise types, attributed to its localized processing strategy that adapts to local statistics without introducing global artifacts [29].

Performance Benchmarking

The following table summarizes the quantitative performance of classical denoising filters across standard medical imaging metrics, as reported in recent literature.

Table: Denoising Algorithm Performance Comparison on Medical Images

| Denoising Method | PSNR (dB) | SSIM | MSE | Computational Efficiency | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Filtering | Moderate (e.g., ~25-30) | Moderate (~0.80-0.85) | Moderate | High / Fast | Simple, fast smoothing for high-frequency noise [5] [28]. |

| Bilateral Filtering | Moderate to High | Good (~0.85-0.90) | Moderate | Moderate (slower than Gaussian) | Edge-preserving smoothing [27]. |

| Wavelet (Coiflet4) | High (e.g., ~32-35) | Good (~0.90-0.92) | Low | Moderate | Multi-resolution analysis, good detail preservation [25]. |

| Gaussian Pyramid (GP) | 36.80 | 0.94 | Low | High / 0.0046s | Multi-scale strategy, excellent balance of quality and speed [25]. |

| BM3D | High to Very High (top performer) | High (~0.95+) | Very Low | Low / Slow | Exploits non-local similarity, state-of-the-art for traditional methods [5]. |

Standard Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducible and comparable results in your thesis research, adhere to the following standardized protocols.

Protocol 1: Implementing a Bilateral Filter for CT Image Denoising

- Image Preprocessing: Convert the CT image to grayscale if necessary and normalize pixel intensity values to a standard range (e.g., 0-1).

- Parameter Initialization: Set the diameter of the pixel neighborhood and initialize the filter parameters. Recommended starting values are spatial sigma (σd) = 2 and range sigma (σr) = 0.1 * (maxintensity - minintensity).

- Filter Application: Apply the bilateral filter to the entire image. The output pixel value is a weighted average of neighboring pixels, where the weights are based on both the spatial kernel and the intensity range kernel.

- Validation: Quantitatively, calculate PSNR and SSIM by comparing the denoised image with a clean reference image. Qualitatively, have a domain expert assess the preservation of critical structures like small lesions and vessel edges [27] [28].

Protocol 2: Wavelet-Based Denoising for Brain MRI

- Wavelet Decomposition: Select a wavelet family (e.g., Daubechies 'db4') and a decomposition level (e.g., 3). Decompose the noisy brain MRI image into wavelet coefficients, producing approximation (LL) and detail (LH, HL, HH) sub-bands at multiple resolutions. The workflow for this process is outlined below.

- Threshold Estimation & Application: Estimate a threshold (δ) for the detail coefficients (LH, HL, HH). You can use a universal threshold or a level-dependent threshold. Apply your chosen threshold function (see Table 2) to these detail coefficients to suppress noise.

- Image Reconstruction: Perform an inverse wavelet transform using the original approximation coefficients (LL) and the modified detail coefficients to reconstruct the denoised image [29] [30].

- Validation: Evaluate using PSNR, SSIM, and Mean Squared Error (MSE). For Rician noise, perceptual quality metrics like BRISQUE can also be informative [5] [30].

Method Selection Workflow

This decision diagram helps select an appropriate denoising method based on your research constraints and goals.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table outlines key computational "reagents" essential for experiments with classic denoising filters.

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Denoising Experiments

| Reagent (Algorithm/Tool) | Function in Experiment | Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Filter | Baseline low-pass filtering for noise suppression. | Parameters: Kernel size, Sigma (σ). A larger σ increases smoothing. Ideal for initial pre-processing or high-noise scenarios where detail loss is acceptable [15] [28]. |

| Bilateral Filter | Edge-preserving smoothing for structural integrity. | Parameters: Spatial Sigma (σd), Range Sigma (σr). Computationally more intensive than Gaussian. Use when edges and sharp features must be maintained [27]. |

| Wavelet Transform Toolbox | Multi-resolution analysis and non-linear thresholding. | Specs: Wavelet Family (Haar, Daubechies, Coiflets), Decomposition Level, Threshold Function (Soft, Hard, Adaptive). The core tool for separating signal from noise in the frequency domain [29] [30]. |

| BM3D Algorithm | High-performance benchmark for traditional denoising. | Function: Uses collaborative filtering in 3D groups of similar image patches. Considered a state-of-the-art traditional method against which to compare your results [5] [28]. |

| Quality Metrics (PSNR, SSIM) | Quantitative evaluation of denoising performance. | PSNR: Measures noise reduction level. SSIM: Assesses perceptual image integrity and structural preservation. Both typically require a clean reference image [15] [5]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Under what conditions does BM3D achieve its best performance in medical imaging? BM3D consistently achieves its best performance on medical images, such as MRI and HRCT, at low to moderate noise levels [31]. Under these conditions, it reliably produces the highest Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) and Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) values compared to other classical and deep learning-based algorithms like DnCNN, NLM, and Bilateral filters [31] [28]. Its effectiveness diminishes with very high noise levels, where other methods may become more competitive.

Q2: What is the primary trade-off when using BM3D for medical image denoising? The primary trade-off is between denoising quality and computational efficiency [31]. While BM3D is highly effective at noise reduction and detail preservation, it has high computational complexity, which can limit its practicality in time-sensitive clinical scenarios [31] [32]. This is especially true when processing high-noise images or large datasets.

Q3: How does BM3D's performance compare to deep learning methods like DnCNN? BM3D and DnCNN excel in different scenarios. BM3D is a dependable, high-performing choice for images with moderate noise [31]. In contrast, advanced deep learning methods like DnCNN are often better suited for handling significant noise variations and can adapt to more complex, real-world noise distributions without compromising critical diagnostic features [31] [28]. Deep learning methods, however, typically require large, annotated datasets for training.

Q4: A key challenge with BM3D is its reliance on accurate noise level estimation. How can this be addressed? Standard BM3D requires an estimate of the noise level (variance) as an input parameter. An ineffective solution is to manually tune this parameter for different image sets. A more robust and effective approach, as demonstrated in recent research, is to integrate an automatic noise estimation technique [32]. For instance, using Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) on the image to estimate the noise variance from the tail of singular values before applying BM3D has been shown to improve denoising performance and make the algorithm more adaptive to natural images with unknown noise sources [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Over-Smoothing and Loss of Fine Anatomical Details

Problem: After applying BM3D, the image appears too smooth, and small but diagnostically critical features (like early-stage tumors or small lesions) are blurred or lost [31] [28].

Solution:

- Verify Noise Level Parameter: The most common cause is using an inaccurately high noise level estimate. Re-check the

noise_std(noise standard deviation) parameter provided to the algorithm. For medical images, start with a lower value and incrementally increase it until noise is reduced without noticeable detail loss [32]. - Leverage Multi-Scale Strategies: Consider using a multi-scale framework. A hybrid approach can be implemented where a heavily smoothed version of the image (using a different filter) is used to segment large, homogeneous regions, while BM3D with a lower noise parameter is applied to preserve finer structures at subsequent scales [33].

Issue 2: High Computational Time and Memory Usage

Problem: The denoising process is slow, making it unsuitable for processing large batches of high-resolution medical images or for real-time applications [31].

Solution:

- Optimize Block-Matching Parameters: Adjust the key parameters of the BM3D algorithm. Reducing the size of the reference blocks, limiting the search window for similar patches, and controlling the maximum number of patches per group can significantly speed up computation [31].

- Investigate Alternative Algorithms: For scenarios requiring faster processing, evaluate other denoising methods. Lightweight self-supervised networks (e.g., Noise2Detail) or multi-scale Gaussian pyramid approaches have been proposed to offer a better balance between processing speed and reconstruction quality [20] [25].

Issue 3: Poor Performance on Images with Very High or Complex Noise

Problem: BM3D does not effectively remove noise from images acquired with low-dose protocols or from modalities with complex, non-Gaussian noise [34] [25].

Solution:

- Pre-Estimate Noise: Use a dedicated noise estimation step before denoising. Integrating an SVD-based noise estimator, as mentioned in FAQ 4, provides BM3D with a more accurate prior, enhancing its performance on images with unknown or complex noise characteristics [32].

- Switch to a More Robust Denoiser: For inherently low-SNR images, such as hyperpolarized 129Xe MRI, unsupervised deep learning methods like Noise2Void (N2V) have demonstrated minimal bias in quantitative metrics (like Ventilation Defect Percentage) compared to supervised methods and BM3D, making them more suitable for such challenging data [34].

Experimental Performance Data

The following tables summarize quantitative performance data for the BM3D algorithm from recent studies on medical and other image types.

Table 1: Comparative Algorithm Performance on MRI and HRCT Images [31]

| Algorithm | Domain | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BM3D | Transform | Highest PSNR/SSIM at low-moderate noise; preserves structural integrity [31] | High computational complexity [31] | MRI/HRCT with moderate noise |

| DnCNN | Deep Learning | Handles significant noise variations; preserves diagnostic features [31] [28] | Requires large training datasets [31] | High noise levels; large available data |

| NLM | Spatial | Exploits non-local self-similarity [28] | High computational complexity; inaccurate weights with high noise [32] | Images with repetitive structures |

| Bilateral | Spatial | Preserves edges effectively [28] | Less effective against low-frequency noise [32] | Edge preservation in low-noise images |

Table 2: Denoising Performance on Acoustic and Real-World Images [25] [35]

| Image Type | Denoising Method | Performance Metrics | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acoustic Images | BM3D | High PSNR and SSIM vs. ground truth [35] | Demonstrated best results for denoising acoustic image data [35] |

| Real-World Images (X-ray, MRI, SIDD) | Multi-scale Gaussian Pyramid | PSNR: 36.80 dB, SSIM: 0.94, Complexity: 0.0046 s [25] | Offers an effective balance between detail preservation and computational cost [25] |

Standard Experimental Protocol for BM3D

Title: Protocol for Evaluating BM3D on Medical Images with Synthetic Gaussian Noise

1. Objective To quantitatively and qualitatively evaluate the performance of the BM3D denoising algorithm on medical images (e.g., MRI, HRCT) corrupted with additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN).

2. Materials and Reagents Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Clean Image Dataset | Serves as high-quality ground truth data. | Set12 dataset, AxFLAIR brain MRI, Cor-PD knee MRI [32] [33] |

| Noise Model | Simulates realistic image degradation for algorithm testing. | Additive White Gaussian Noise (AWGN) with mean=0 [31] [32] |

| Performance Metrics | Quantifies denoising effectiveness and image quality preservation. | PSNR, SSIM, MSE [31] [28] [35] |

| Computational Environment | Provides the hardware/software platform for algorithm execution. | MATLAB R2021a, 10-core CPU, 32GB RAM [32] |

3. Methodology

- Step 1 - Data Preparation: Select a set of clean medical images to use as ground truth. Generate noisy images by adding AWGN with a known variance (σ²) to the clean images. Common noise levels for testing include σ = 10, 15, 20, and 25 [28].

- Step 2 - Parameter Configuration: Initialize the BM3D algorithm. The critical parameter is the noise standard deviation (

noise_std), which should be set to the known σ used in Step 1. Other parameters like block size and search window can be left at defaults or optimized. - Step 3 - Algorithm Execution: Run the BM3D algorithm on the noisy images to generate the denoised outputs.

- Step 4 - Performance Analysis: Calculate quantitative metrics by comparing the denoised images against the clean ground truth images. Key metrics include:

- Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR): Measures the ratio between the maximum possible power of a signal and the power of corrupting noise. Higher is better [31] [35].

- Structural Similarity Index (SSIM): Assesses the perceptual similarity between two images, focusing on structural information. Closer to 1 is better [31] [35].

- Step 5 - Qualitative Assessment: Visually inspect the denoised images to ensure that critical anatomical structures and fine details have been preserved without excessive smoothing or the introduction of artifacts.

4. Expected Output The protocol yields a set of denoised images and a table of quantitative metrics (PSNR, SSIM) for each image and noise level, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of BM3D's performance.

BM3D Algorithm Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the core stages of the BM3D denoising algorithm.

The workflow consists of two main stages. The first stage creates a basic estimate by finding similar image patches, grouping them, and applying a hard threshold in a 3D transform domain to remove noise. The second stage uses this basic estimate to guide a more refined Wiener filtering process on new groupings of patches, leading to the final high-quality denoised output [32] [35].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common challenges researchers face when implementing deep learning models for medical image denoising, providing targeted solutions based on recent research findings.

FAQ: My denoised medical images are losing important lesion edge information, adversely clinical diagnosis. How can I better preserve these critical details?

Answer: This is a common problem when denoising networks fail to preserve structurally significant features. Based on recent research, we recommend implementing attention mechanisms that selectively focus on important anatomical structures.

Solution 1: Integrate Multi-Attention Modules. A U-Net architecture augmented with multiple attention modules has demonstrated excellent performance in preserving lesion edge information. The local attention module localizes surrounding feature map information, the multi-feature channel attention module suppresses invalid information, and the hierarchical attention module extracts extensive feature information while maintaining network lightweight [36]. An enhancement learning module stacked with convolution, batch normalization, and activation layers can further help retain detail [36].

Solution 2: Use U-Net++ Architecture. For tasks requiring high structural fidelity, U-Net++ with its nested skip connections and intermediate layers has been shown to provide superior denoising performance and enhanced structural preservation compared to standard U-Net, particularly under moderate noise levels [23].

FAQ: How do I choose between U-Net and DnCNN for my specific medical denoising task?

Answer: The choice depends on your primary objective: detail preservation versus efficient noise removal.

U-Net and its Variants (U-Net++, U-Tunnel-Net) are generally preferred when the goal is to preserve complex structures and anatomical boundaries, thanks to their encoder-decoder structure with skip connections that maintain spatial information [36] [23] [37]. They are particularly effective for medical images where structural integrity is critical for diagnosis.

DnCNN is often more effective for pure noise removal, especially when dealing with Gaussian-type noise. It uses residual learning to predict and subtract noise from the noisy input image [5] [38] [39]. A complex-valued DnCNN (ℂDnCNN) is particularly advantageous for MRI data as it processes both magnitude and phase information, unlike traditional real-valued networks [38].

Table: Comparative Analysis of Denoising Architectures

| Architecture | Strengths | Ideal Use Cases | Key Performance Metrics (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| U-Net with Multi-Attention | Excellent detail preservation, retains lesion edges | LDCT images, diagnostic tasks where feature preservation is critical | PSNR: 34.73, SSIM: 0.929 on QINLUNGCT [36] |

| U-Net++ | Enhanced structural fidelity, nested skip connections | Chest X-ray denoising, complex anatomical structures [23] | Competitive PSNR/SSIM, better LPIPS under low noise [23] |

| DnCNN | Efficient Gaussian noise removal, residual learning | General denoising, MRI data (when using complex-valued variant) [5] | High PSNR on Gaussian noise [5] |

| Non-blind ℂDnCNN | Handles complex-valued MRI data, preserves phase | Low-field MRI denoising, parallel imaging noise [38] | Improved SNR and visual quality for in vivo data [38] |

| U-Tunnel-Net | Superior speckle noise reduction, repositioned pooling | Ultrasound image despeckling, image restoration [37] | PSNR 30.21-39.52 on UNS dataset [37] |

FAQ: I'm experiencing extremely long training times with my 3D medical image data. What optimization strategies can I implement?

Answer: Distributed training and architectural optimization can significantly reduce training time.

Strategy 1: Implement Distributed Data Parallel (DDP) Training. Replace standard single-GPU or DataParallel training with PyTorch's DistributedDataParallel (DDP). Research shows this, combined with Automatic Mixed Precision (AMP), can reduce training time by over 60% compared to single-GPU training and outperforms standard DataParallel by over 40%, with only a minor accuracy drop [23].