Mastering Real-Time PCR Data Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Gene Expression Profiling in Biomedical Research

This comprehensive guide explores the foundational principles, methodologies, and best practices for real-time PCR data analysis in gene expression profiling.

Mastering Real-Time PCR Data Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Gene Expression Profiling in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This comprehensive guide explores the foundational principles, methodologies, and best practices for real-time PCR data analysis in gene expression profiling. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers essential techniques from basic quantification methods to advanced optimization strategies. The article provides practical insights into data analysis approaches, troubleshooting common challenges, and validating results, with emphasis on current market trends including AI integration and spatial transcriptomics. By synthesizing established protocols with emerging technologies, this resource aims to enhance accuracy and reproducibility in gene expression studies critical for drug discovery, clinical diagnostics, and precision medicine applications.

Foundations of Gene Expression Analysis: Principles and Market Landscape of Real-Time PCR Technologies

The gene expression market encompasses products and services used to analyze and quantify how genetic information is used to synthesize functional gene products like proteins and RNA. This field is a cornerstone of modern molecular biology, supporting applications from basic research to clinical diagnostics and drug discovery [1] [2]. The market is experiencing significant growth, driven by technological advancements, rising demand for personalized medicine, and increasing investment in genomics research.

Quantitative Market Projections

Table 1: Global Gene Expression Market Size and Growth Projections

| Source | Base Year (2024) | Base Year Value (USD Billion) | Forecast Year | Forecast Value (USD Billion) | CAGR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Straits Research | 2024 | 15.15 | 2033 | 24.38 | 4.87% [1] |

| The Business Research Company | 2024 | 11.55 | 2029 | 19.81 | 11.8% [3] [4] |

| Towards Healthcare | 2024 | 15.45 | 2034 | 25.26 | 5.04% [5] |

| Precedence Research | 2024 | 14.88 | 2034 | 40.40 | 10.50% [2] |

| Coherent Market Insights | 2025 | 16.56 | 2032 | 23.61 | 5.2% [6] |

Table 2: Gene Expression Market Size by Application Segment (2025 Projections)

| Application | Projected Market Share (%) | Key Growth Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Discovery & Development | 45.6% [6] | Target identification, biomarker discovery, therapeutic efficacy and safety evaluation [1] [6] |

| Clinical Diagnostics | Fastest Growing Segment [5] | Precision medicine needs, disease biomarker identification, and early disease detection [5] [2] |

| Biotechnology & Microbiology | Significant share | Widespread use in basic research and industrial applications [1] |

Key Market Dynamics

Primary Growth Drivers

- Rising Demand for Personalized and Precision Medicine: Personalized medicine, which tailors treatments to an individual's genetic profile, is a major growth driver. Gene expression analysis is critical for identifying genetic signatures, disease subtypes, and biomarkers that predict treatment response, enabling more effective and targeted therapies [1] [3] [4].

- Increasing Prevalence of Chronic Diseases: The growing global burden of chronic diseases, particularly cancer, fuels market growth. Gene expression profiling helps unravel disease mechanisms, identify molecular targets for new drugs, and develop diagnostic and prognostic tests [3] [5].

- Technological Advancements: Continuous innovation in technologies such as Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), digital PCR, and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-Seq) enhances the throughput, sensitivity, and affordability of gene expression analysis. The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning further revolutionizes data interpretation and biomarker discovery [5] [6] [7].

Major Market Restraints and Opportunities

- Market Restraints: The high cost of advanced instruments and specialized reagents can limit accessibility for smaller research institutions and laboratories. Furthermore, the complexity of managing and interpreting the vast, intricate datasets generated by modern technologies like RNA-Seq presents a significant challenge, requiring sophisticated bioinformatics tools and expertise [1] [5] [7].

- Market Opportunities: Key growth opportunities lie in the development of high-throughput, cost-effective technologies for single-cell gene expression profiling, which is transforming understanding of cellular heterogeneity. There is also significant potential in emerging markets, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region, and in the growing demand for cloud-based bioinformatics solutions that simplify data analysis [1] [5] [8].

Regional Market Analysis

Table 3: Regional Market Share and Growth Trends

| Region | 2024/2025 Market Share | Growth Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| North America | Largest share (39.3% - 47%) [2] [6] | Mature market driven by advanced research infrastructure, major industry players, significant government funding, and high adoption of precision medicine. |

| Asia-Pacific (APAC) | Fastest-growing region [3] [5] [2] | Rapid growth fueled by increasing healthcare spending, government investments in genomics, a burgeoning biotechnology sector, and a large patient population. |

| Europe | Significant market share [6] | Well-established healthcare and research infrastructure, with strong national support for biotech innovation and life sciences research. |

Key Technologies and Techniques in Gene Expression Analysis

Gene expression analysis relies on several core technologies, each with distinct applications in research and diagnostics.

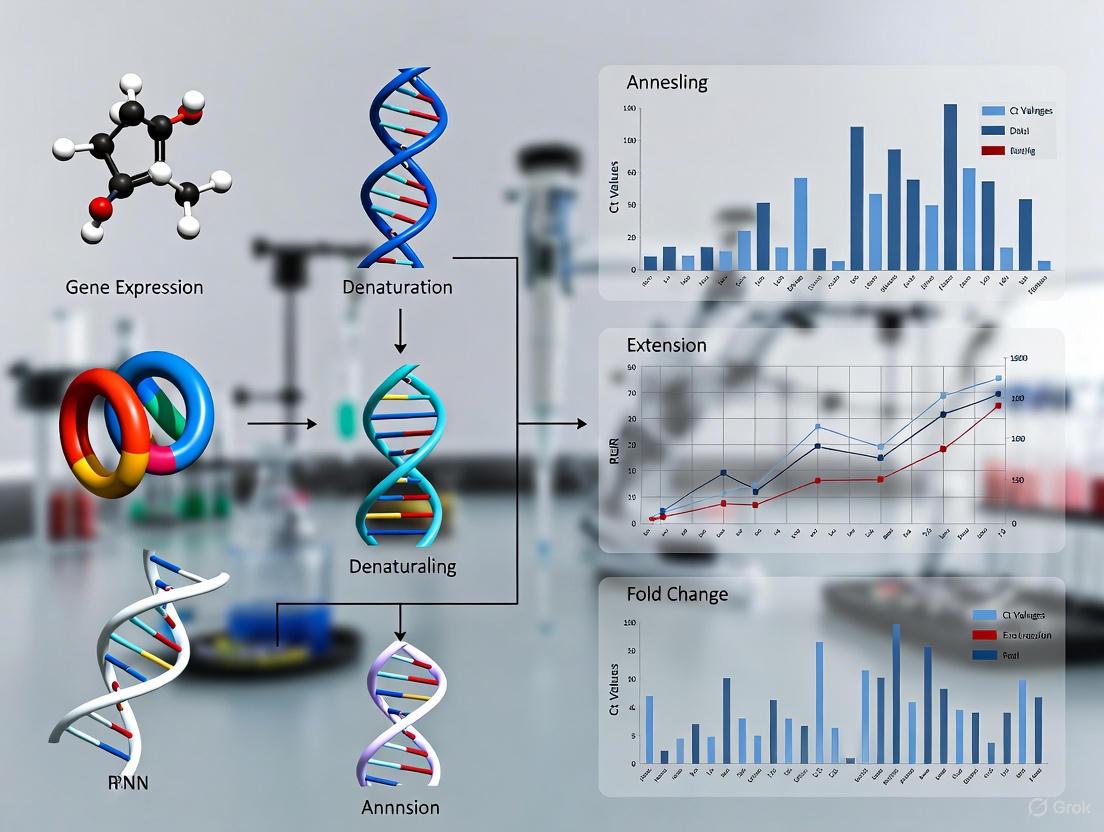

Diagram: Gene Expression Analysis Core Workflow. This flowchart outlines the primary steps and technology options in a gene expression study, from sample preparation to data interpretation.

Dominant Technology Segments

- By Product: The kits and reagents segment dominates the market in terms of consistent revenue due to their routine and repetitive use in virtually every gene expression experiment [1] [5]. However, the instruments segment (including PCR systems, NGS platforms, and microarray scanners) also commands a major market share, projected at 48.1% in 2025, as they form the foundational infrastructure for analysis [6].

- By Technique: RNA Expression analysis, especially via qRT-PCR and RNA-Seq, is a dominant segment due to its direct measurement of transcript levels [5]. DNA Microarray technology also holds a significant share, valued for its proven reliability and cost-effectiveness in high-throughput profiling [6]. The fastest-growing technique is single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-Seq), which enables the resolution of gene expression at the individual cell level, revealing cellular heterogeneity previously masked in bulk tissue analyses [5] [7].

Experimental Protocol: Gene Expression Profiling via Real-Time PCR

Real-time PCR (qPCR) is a gold-standard method for targeted gene expression analysis due to its sensitivity, specificity, and quantitative nature. The following protocol provides a detailed methodology for reliable gene expression profiling.

Workflow and Reagent Solutions

Diagram: qPCR Gene Expression Workflow. A sequential overview of the key stages in a qPCR-based gene expression experiment.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR Gene Expression Analysis

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Isolation Kits | Purify high-quality, intact total RNA from cell or tissue samples. | Select kits with DNase treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination. Quality of RNA is critical for assay success [3] [5]. |

| Reverse Transcription Kits | Synthesize first-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template using reverse transcriptase enzyme. | Contains reverse transcriptase, buffers, dNTPs, and primers (oligo-dT, random hexamers, or gene-specific) [3] [5]. |

| qPCR Reagent Kits | Enable amplification and fluorescent detection of target cDNA. Includes master mix, primers, and probes. | Master mix contains hot-start DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and a fluorescent dye (e.g., SYBR Green) or probe (e.g., TaqMan). Optimized primer pairs are essential for specificity [3] [7]. |

| Reference Gene Assays | Detect constitutively expressed genes (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin) for data normalization. | Required for the ΔΔCq method to correct for sample-to-sample variation. Must be validated for the specific experimental conditions [5]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Diluent for reagents and samples. | Essential to prevent degradation of RNA and enzymes by RNases. |

Detailed Experimental Methodology

Sample Collection, RNA Extraction & Quality Control

- Procedure: Collect tissue or cells, immediately stabilize RNA using reagents like RNAlater, and snap-freeze in liquid nitrogen. Extract total RNA using a spin-column-based kit. The typical protocol involves cell lysis, binding of RNA to a silica membrane, washing with ethanol-based buffers, and elution in nuclease-free water.

- Critical Step: Assess RNA quality and quantity using spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio ~2.0) and/or microfluidic analysis (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer, RNA Integrity Number >8.0). High-quality RNA is essential for accurate cDNA synthesis [5].

cDNA Synthesis and Conversion

- Procedure: Set up a reverse transcription reaction containing 0.1-1 µg of total RNA, reverse transcriptase enzyme, reaction buffer, dNTPs, RNase inhibitor, and primers. A common approach is to use a mix of oligo-dT and random hexamers to ensure comprehensive cDNA representation.

- Thermocycler Conditions:

- Primer Annealing: 25°C for 5-10 minutes.

- Reverse Transcription: 42-50°C for 30-60 minutes.

- Enzyme Inactivation: 85°C for 5 minutes.

- Output: The resulting cDNA is used as the template for qPCR amplification [5].

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Amplification

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a qPCR mix containing cDNA template, qPCR master mix (with DNA polymerase, dNTPs, MgCl₂, and fluorescent dye), and gene-specific forward and reverse primers. Each sample should be run in technical replicates.

- qPCR Run Protocol:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2-5 minutes.

- Amplification (40-45 cycles):

- Denature: 95°C for 10-30 seconds.

- Anneal/Extend: 60°C for 30-60 seconds (acquire fluorescence signal at this step).

- Output: The Cq (Quantification Cycle) value for each reaction, which is the cycle number at which the fluorescence signal crosses a defined threshold [5].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Normalization: Normalize the Cq values of the target genes to the Cq values of one or more stable reference genes to account for variations in input and efficiency. This yields the ΔCq value [5].

- Relative Quantification (ΔΔCq Method): Calculate the ΔΔCq by comparing the ΔCq of the experimental sample to the ΔCq of a calibrator sample (e.g., untreated control). The final fold-change in gene expression is calculated as 2^(-ΔΔCq) [5].

- Statistical Analysis: Perform appropriate statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA) on the ΔCq or fold-change values to determine significance. Visualization using bar graphs of fold-change is standard.

The gene expression market is on a robust growth path, underpinned by its indispensable role in advancing personalized medicine, drug discovery, and clinical diagnostics. While challenges related to cost and data complexity persist, they are being addressed through technological innovation. The continued evolution of techniques like qPCR, NGS, and single-cell analysis, augmented by AI, will further solidify gene expression profiling as a fundamental tool for researchers and drug development professionals worldwide.

Core Principles of Real-Time PCR Fluorescence Detection Mechanisms

Real-time PCR (qPCR) is a powerful molecular technique that allows for the monitoring of nucleic acid amplification as it occurs, enabling both detection and quantification of specific DNA or RNA targets. The core of this technology lies in its fluorescence detection mechanisms, which provide a direct, real-time signal proportional to the amount of amplified product [9]. For gene expression profiling research, understanding these principles is fundamental to generating accurate, reproducible, and biologically meaningful data. This guide details the chemistries, protocols, and analytical frameworks that underpin reliable qPCR experimentation.

Fundamental Detection Chemistries

The fluorescence detection methods in real-time PCR can be broadly classified into two categories: non-specific DNA-binding dyes and sequence-specific fluorescent probes [10] [9] [11]. The choice between them is a critical first step in experimental design, balancing specificity, cost, and flexibility.

Non-Specific Detection: DNA-Binding Dyes

SYBR Green I is the most widely used DNA-binding dye [12] [11]. It is an asymmetric cyanine dye that binds to the minor groove of double-stranded DNA (dsDNA). Its key property is a massive increase in fluorescence (over 1000-fold) upon binding to dsDNA compared to its unbound state in solution [12] [11]. As the PCR progresses, the accumulation of amplicons leads to more dye binding and a corresponding increase in fluorescence signal measured at the end of each elongation step [13].

- Primary Advantage: Cost-effectiveness and assay design simplicity, as only two target-specific primers are required.

- Major Disadvantage: Lack of inherent specificity; SYBR Green I will bind to any dsDNA present in the reaction, including non-specific products like primer-dimers. This can lead to overestimation of the target concentration [12] [13].

- Specificity Verification: The non-specific nature of dye-based detection makes post-amplification melting curve analysis essential. After the final PCR cycle, the temperature is gradually increased while fluorescence is continuously monitored. As the temperature passes the melting temperature (Tm) of each dsDNA species, the strands separate, and the dye is released, causing a rapid drop in fluorescence. A single, sharp peak in the derivative plot of fluorescence versus temperature indicates a single, specific amplicon. Multiple peaks suggest the presence of non-specific amplification or primer-dimer artifacts [12].

Other dyes, such as EvaGreen, have also been developed and may offer improved performance in some applications, but SYBR Green I remains the most popular [10].

Sequence-Specific Detection: Fluorescent Probes

Probe-based chemistries offer a higher degree of specificity by requiring hybridization of a third, target-specific oligonucleotide in addition to the two primers. This ensures that the fluorescent signal is generated only upon amplification of the intended target [10].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Sequence-Specific Probe Chemistries

| Probe Type | Core Mechanism | Key Components | Primary Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrolysis Probes (TaqMan) | The 5'→3' exonuclease activity of Taq polymerase cleaves a probe hybridized to the target, separating a reporter dye from a quencher [13] [9]. | Oligonucleotide with 5' reporter dye (e.g., FAM) and 3' quencher (e.g., BHQ, TAMRA) [12]. | High specificity, suitability for multiplexing with different colored dyes [13]. | Gene expression, viral load quantification, SNP genotyping [9]. |

| Molecular Beacons | A stem-loop structured probe undergoes a conformational change upon hybridization, separating the reporter and quencher [12] [11]. | Hairpin oligonucleotide with reporter and quencher at opposite ends of the stem. | Excellent specificity due to the stem-loop structure, low background signal [11]. | SNP detection, pathogen identification [11]. |

| FRET Hybridization Probes | Two adjacent probes hybridize to the target, enabling FRET from a donor fluorophore to an acceptor fluorophore [12] [11]. | Two separate probes, one with a donor dye (e.g., fluorescein), another with an acceptor dye (e.g., LC Red 640, LC Red 705). | Signal is reversible, allowing for melting curve analysis for genotyping or mutation detection [11]. | High-resolution melting analysis, mutation scanning [11]. |

| Scorpion Probes | The probe element is covalently linked to a primer, creating an intramolecular hybridization event that is highly efficient [12]. | Single oligonucleotide combining a primer with a probe domain, separated by a blocker. | Fast reaction kinetics and high efficiency due to the unimolecular probing mechanism [12]. | SNP scoring, real-time genotyping [12]. |

A critical component of most probe systems is the quencher. Early quenchers like TAMRA were themselves fluorescent, which could lead to background noise. Modern dark quenchers (e.g., Black Hole Quencher - BHQ, Onyx Quencher - OQ) do not emit light, absorbing the reporter's energy and releasing it as heat, thereby providing a superior signal-to-noise ratio [12].

The qPCR Workflow and Quantitation

A standard qPCR workflow for gene expression analysis involves RNA extraction, reverse transcription to complementary DNA (cDNA), and the real-time PCR reaction itself [9]. Quantitation is based on the principle that the number of amplification cycles required for the fluorescence signal to cross a predetermined threshold is inversely proportional to the starting quantity of the target.

Key Quantitative Parameters

- Amplification Curve: The plot of fluorescence versus cycle number. It typically shows a baseline (initial cycles with no significant signal increase), an exponential phase (where amplification is most efficient and quantitative), and a plateau phase (where reagents become limiting) [9].

- Threshold: An arbitrary fluorescence level set within the exponential phase of amplification, significantly above the background baseline [13] [9].

- Ct (Threshold Cycle): The fractional PCR cycle number at which the sample's fluorescence exceeds the threshold. A sample with a lower Ct value contained a higher starting concentration of the target [13] [9].

Absolute vs. Relative Quantitation

- Absolute Quantitation: Involves interpolating the quantity of an unknown sample from a standard curve generated using known concentrations of a standard (e.g., a plasmid with the target sequence). This is used to determine the exact copy number of a target [13].

- Relative Quantitation: Determines the change in target expression in a test sample relative to a control sample (e.g., untreated vs. treated). This method requires a stable reference gene (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB) for normalization to account for variations in RNA input and cDNA synthesis efficiency. The 2^(-ΔΔCt) method is a widely used computational approach for this type of analysis [14] [9].

Experimental Protocol: Gene Expression Profiling via Two-Step RT-qPCR

This protocol outlines the steps for profiling differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using a two-step RT-qPCR approach with SYBR Green I chemistry, as employed in validation studies [14] [15].

Step 1: RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription

- Total RNA Isolation: Extract total RNA from tissues or cells of interest (e.g., fibrous root, tuberous root, stem, leaf) using a commercial kit. Assess RNA integrity and purity via spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio ~2.0) and/or agarose gel electrophoresis.

- DNase Treatment: Treat the purified RNA with DNase I to remove any contaminating genomic DNA.

- First-Strand cDNA Synthesis: Using 1 µg of total RNA, perform reverse transcription with a cDNA synthesis kit. Use a mixture of random hexamers and oligo-dT primers to ensure comprehensive conversion of both mRNA and other RNA species. Typical reaction conditions: 25°C for 10 minutes (annealing), 42°C for 50 minutes (extension), 70°C for 15 minutes (enzyme inactivation). Dilute the resulting cDNA for use in qPCR.

Step 2: Quantitative Real-Time PCR

- Reaction Setup: Prepare reactions in a total volume of 20 µL containing:

- 1X SYBR Green I PCR Master Mix (includes DNA polymerase, dNTPs, Mg2+, and SYBR Green I dye)

- Forward and Reverse Primers (e.g., 250 nM each, designed for a 50-150 bp amplicon)

- cDNA template (e.g., 2 µL of diluted cDNA)

- Nuclease-free water to volume.

- Thermal Cycling: Run the reactions in a real-time PCR instrument with the following cycling protocol:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 10 minutes (activates the hot-start polymerase).

- 40-45 Cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 seconds.

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 minute (data acquisition at the end of this step).

- Melting Curve Analysis: 65°C to 95°C, with continuous fluorescence measurement (e.g., increment of 0.5°C every 5 seconds).

Data Analysis

- Ct Acquisition: Determine the Ct value for each reaction using the instrument's software.

- Normalization: Normalize the Ct values of the target genes to the geometric mean of one or more stable reference genes (e.g., IbACT, IbARF, IbCYC in sweet potato) [15]. The stability of reference genes must be validated for the specific tissues and conditions under study using algorithms like GeNorm or NormFinder [15].

- Fold-Change Calculation: Calculate the relative fold change in gene expression using the 2^(-ΔΔCt) method [14]. For example, a study on hypertension genes reported fold changes calculated this way, showing 3-times higher expression for upregulated genes like ADM and ANGPTL4 [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR

| Item | Function / Role in the Workflow |

|---|---|

| SYBR Green I Master Mix | A pre-mixed, optimized solution containing buffer, dNTPs, hot-start DNA polymerase, MgCl₂, and the SYBR Green I dye. Simplifies reaction setup and ensures reproducibility [13]. |

| TaqMan Gene Expression Assay | A pre-designed and validated set of primers and a FAM-labeled TaqMan MGB probe for a specific gene target. Offers high specificity and convenience, eliminating assay design and optimization [13]. |

| RNA Extraction Kit | For the isolation of high-quality, intact total RNA from various biological sources. The quality of the starting RNA is the most critical factor for reliable gene expression data. |

| Reverse Transcription Kit | Contains reagents (reverse transcriptase, buffers, primers, dNTPs) for the efficient synthesis of first-strand cDNA from an RNA template [9]. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Essential for preparing all reaction mixes to prevent degradation of RNA, DNA, and enzymes by environmental nucleases. |

| Optical Plates & Seals | Specialized microplates and adhesive films designed for optimal thermal conductivity and optical clarity for fluorescence detection in real-time PCR cyclers. |

| Validated Reference Genes | Genes with stable expression across all experimental test conditions, used for data normalization (e.g., IbACT, IbARF for sweet potato tissues; GAPDH, β-actin for mammalian cells) [15]. |

Visualization of Probe Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate the mechanisms of the two most common probe-based detection chemistries.

Mastering the core principles of real-time PCR fluorescence detection is paramount for designing robust experiments, critically evaluating data, and advancing research in gene expression profiling and drug development. The continuous evolution of chemistries, instruments, and analysis frameworks further solidifies qPCR's role as an indispensable tool in the molecular life sciences.

In gene expression profiling research, accurate nucleic acid quantification is fundamental for understanding cellular function, disease mechanisms, and drug responses. The two principal methodologies for quantifying gene expression data are absolute quantification and relative quantification. Absolute quantification determines the exact number of target DNA or RNA molecules in a sample, expressed as copies per microliter or other concrete units [16]. In contrast, relative quantification measures changes in gene expression by comparing the target amount to a reference gene (often a housekeeping gene) across different experimental conditions, expressing the result as a fold-difference relative to a calibrator sample (e.g., an untreated control) [16]. The choice between these methods significantly impacts data interpretation, requiring researchers to align their selection with specific experimental goals, from validating biomarker levels to understanding differential expression in response to therapeutic compounds.

Within the context of real-time PCR (qPCR) data analysis, this choice dictates the entire experimental workflow, from assay design and standard preparation to data normalization and statistical analysis. Absolute quantification is often synonymous with high-stakes applications like viral load determination in vaccine studies or validating transcript numbers in pre-clinical drug development [16]. Relative quantification, being more straightforward to implement, dominates studies of gene expression changes in response to stimuli, such as screening the effects of a new drug candidate on a pathway of interest [16]. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison to empower researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select and implement the optimal quantification strategy for their specific research objectives.

Core Principles and Methodologies

Absolute Quantification

Absolute quantification provides a precise count of the target nucleic acid molecules present in a sample without relying on a reference or calibrator. This approach can be executed through two main technological paths: the digital PCR (dPCR) method and the standard curve method using real-time PCR [16].

The digital PCR (dPCR) method represents a paradigm shift in quantification. The sample is partitioned into thousands to millions of individual reactions so that each partition contains either zero or one (or a few) target molecules [17]. Following end-point PCR amplification, the partitions are analyzed as positive or negative based on fluorescence. The absolute copy number concentration is then calculated directly from the ratio of positive to total partitions using Poisson statistics, entirely eliminating the need for a standard curve [16]. This partitioning makes dPCR highly resistant to PCR inhibitors and exceptionally precise for quantifying rare targets and small-fold changes [16]. A key advantage is that "the target of interest can be directly quantified with precision determined by the number of digital PCR replicates" [16].

The standard curve method in qPCR, while also providing absolute numbers, operates on a different principle. It requires the creation of a calibration curve using standards of known concentration [16]. These standards, often serial dilutions of purified plasmid DNA or in vitro transcribed RNA, are run simultaneously with the unknown samples. The cycle threshold (Ct) values of the standards are plotted against the logarithm of their known concentrations to generate a standard curve. The concentration of an unknown sample is then determined by interpolating its Ct value onto this curve [16]. This method's accuracy is heavily dependent on the quality and precise quantification of the standards, requiring accurate pipetting for dilution and careful consideration of standard stability [16].

Relative Quantification

Relative quantification is used to analyze changes in gene expression in a given sample relative to another reference sample, such as an untreated control in a drug treatment experiment [16]. The core outcome is a fold-change value, which indicates how much a gene's expression has increased or decreased under experimental conditions compared to the control state. This method does not provide information about the absolute number of transcript copies but is highly effective for comparative studies. The two primary calculation methods are the standard curve method and the comparative Cт (ΔΔCт) method [16].

In the standard curve method for relative quantification, standard curves are prepared for both the target gene and an endogenous reference gene (e.g., GAPDH, β-actin) [16]. For each experimental sample, the amount of target and reference is determined from their respective standard curves. The target amount is then divided by the endogenous reference amount to obtain a normalized target value. This normalized value is subsequently divided by the normalized target value of the calibrator sample (e.g., the untreated control) to generate the final relative expression level [16]. A significant advantage here is that "because the sample quantity is divided by the calibrator quantity, the unit from the standard curve drops out," meaning any stock nucleic acid with the target can be used to prepare standards, as only relative dilutions need to be known [16].

The comparative Cт (ΔΔCт) method offers a more streamlined approach. It directly compares the Cт value of the target gene to that of the reference gene within the same sample, using the formula 2^–ΔΔCт to calculate the relative fold-change [16]. This method eliminates the need to run separate wells for a standard curve, thereby increasing throughput and conserving precious samples. However, a critical requirement for this method's validity is that "the efficiencies of the target and endogenous control amplifications must be approximately equal" [16]. Researchers must perform a validation experiment to confirm that the amplification efficiencies of both assays are similar and close to 100% before proceeding with the ΔΔCт calculation.

Technical Comparison and Experimental Selection

The decision between absolute and relative quantification, and further between dPCR and qPCR-based methods, hinges on the specific requirements of sensitivity, precision, throughput, and cost.

Table 1: Comparison of Absolute and Relative Quantification Methods

| Feature | Absolute Quantification (dPCR) | Absolute Quantification (Standard Curve) | Relative Quantification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification Output | Exact copy number of the target [16] | Exact copy number of the target [16] | Fold-change relative to a calibrator sample [16] |

| Requires Standard Curve | No [16] [17] | Yes [16] | Yes (for standard curve method), No (for ΔΔCт method) [16] |

| Requires Reference Gene | No [16] | Optional for normalization | Yes (endogenous control) [16] |

| Key Advantage | High precision and sensitivity; resistant to inhibitors; no standards needed [16] [17] | Well-established; suitable for high-throughput workflows [17] | Simple data interpretation; increased throughput (ΔΔCт method) [16] |

| Primary Limitation | Lower throughput; higher cost per sample; limited dynamic range [18] | Variability in standard preparation and dilution [16] | Does not provide absolute copy number; requires efficiency validation (ΔΔCт method) [16] |

| Ideal Application | Rare mutation detection, viral load quantification, liquid biopsy, NGS library quantification [17] | Viral copy number correlation with disease state, quantifying cell equivalents [16] | Gene expression in response to stimuli (e.g., drug treatment), pathway analysis [16] |

A recent study comparing dPCR and Real-Time RT-PCR during the 2023-2024 respiratory virus "tripledemic" highlighted the performance advantages of dPCR. The study found that "dPCR demonstrated superior accuracy, particularly for high viral loads of influenza A, influenza B, and SARS-CoV-2," and showed "greater consistency and precision than Real-Time RT-PCR, especially in quantifying intermediate viral levels" [18]. This makes dPCR a powerful tool for applications where the exact quantity is critical for clinical or diagnostic decisions. However, the study also noted that the "routine implementation is currently limited by higher costs and reduced automation compared to Real-Time RT-PCR" [18], which is a key practical consideration for many labs.

Table 2: Guidelines for Choosing a Quantification Method

| Research Goal | Recommended Method | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Detecting rare alleles or mutations | Digital PCR (Absolute) | "Capable of analyzing complex mixtures" and provides the sensitivity needed for low-abundance targets [16]. |

| Absolute viral copy number in a sample | Digital PCR or Standard Curve (Absolute) | dPCR allows determination "without reference to a standard," while the standard curve method is a proven alternative [16]. |

| Gene expression changes from drug treatment | Relative Quantification | Designed to "analyze changes in gene expression... relative to another reference sample" like an untreated control [16]. |

| High-throughput gene expression screening | Relative Quantification (ΔΔCт) | "You don't need a standard curve and can increase throughput because wells no longer need to be used for the standard curve samples" [16]. |

| Working with samples containing PCR inhibitors | Digital PCR (Absolute) | dPCR is "Highly tolerant to inhibitors" due to the partitioning of the reaction [16]. |

Experimental Protocols for Robust Quantification

Protocol: Absolute Quantification via Standard Curve qPCR

This protocol is critical for applications like correlating viral copy number with a disease state [16].

- Step 1: Standard Preparation. Create a standard using a plasmid containing the target sequence or in vitro transcribed RNA for gene expression. Determine the concentration by A260 measurement and calculate the copy number based on molecular weight. Perform serial dilutions (e.g., 10-fold) over a range that encompasses the expected concentration in unknown samples. "Accurate pipetting is required because the standards must be diluted over several orders of magnitude." To ensure stability, "Divide diluted standards into small aliquots, store at –80°C, and thaw only once before use" [16].

- Step 2: Nucleic Acid Extraction and Reverse Transcription. Extract total RNA from test samples using a validated method (e.g., spin-column or magnetic bead-based kits). Include an RNase-free DNase treatment step to remove genomic DNA contamination. Convert RNA to cDNA using a reverse transcription kit. Note that "It is generally not possible to use DNA as a standard for absolute quantification of RNA because there is no control for the efficiency of the reverse transcription step" [16].

- Step 3: Real-Time PCR Setup and Run. Prepare a master mix containing buffer, dNTPs, polymerase, and fluorescent probe (e.g., TaqMan) or dye (e.g., SYBR Green). Aliquot the mix into a PCR plate, then add the standard dilutions and unknown cDNA samples in triplicate. Run the plate on a real-time PCR instrument with the appropriate cycling conditions.

- Step 4: Data Analysis. The instrument software will generate a standard curve by plotting the Cт values of the standards against the log of their known copy numbers. Ensure the curve has a slope between -3.1 and -3.6, indicating an amplification efficiency of 90-110%. The software will then interpolate the Cт values of the unknown samples against this curve to determine the absolute copy number in each sample.

Protocol: Relative Quantification via the Comparative Cт (ΔΔCт) Method

This protocol is ideal for fast, high-throughput analysis of gene expression changes, such as in response to a drug [16].

- Step 1: Validation of Amplification Efficiency. Before running the actual experiment, a validation experiment is mandatory. Prepare a dilution series of a representative cDNA sample. Amplify both the target gene and the endogenous control (reference gene) using the same cDNA dilutions. Plot Cт values versus the log of the dilution factor. The absolute value of the slope of the resulting line for each gene should be less than 0.1 for the ΔΔCт method to be valid [16].

- Step 2: Experimental qPCR Run. Extract RNA and synthesize cDNA from all experimental and control (calibrator) samples. Set up a real-time PCR reaction for each sample in triplicate for both the target gene and the endogenous control. To save time and reduce pipetting errors, "you can amplify the target and endogenous control in the same tube," provided that the assays are optimized and do not interfere with each other [16].

- Step 3: ΔΔCт Calculation. First, calculate the ΔCт for each sample: ΔCт = Cт (Target Gene) - Cт (Endogenous Control). Next, calculate the ΔΔCт for each experimental sample: ΔΔCт = ΔCт (Experimental Sample) - ΔCт (Calibrator Sample). Finally, calculate the fold-change in gene expression using the formula: Fold Change = 2^(–ΔΔCт).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of quantification experiments relies on high-quality reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for qPCR/dPCR Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| TaqMan Probe Assays | Provide high specificity for target detection through a fluorescently-labeled probe that binds to a specific sequence [19]. | Essential for multiplexing and for applications requiring the highest specificity, such as SNP genotyping. |

| SYBR Green Dye | A fluorescent dye that intercalates with double-stranded DNA, providing a simple and cost-effective detection method [19]. | Requires careful optimization and melt curve analysis to ensure specificity, as it binds to any dsDNA. |

| dPCR Partitioning Plates/Cartridges | Microfluidic devices that split the PCR reaction into thousands of individual nanoliter-scale reactions for absolute counting [18]. | The number of partitions (e.g., ~26,000 in a nanowell system [18]) impacts the precision of the final copy number. |

| MagMax Viral/Pathogen Kit | A magnetic-bead based nucleic acid extraction kit optimized for RNA/DNA purification from complex biological samples [18]. | Efficient removal of PCR inhibitors is critical for robust and reproducible results in both qPCR and dPCR. |

| RNase Inhibitor | An enzyme that protects RNA samples from degradation during handling and storage. | Crucial for maintaining RNA integrity from the moment of sample collection through the reverse transcription step. |

| Low-Binding Tubes and Tips | Plasticware treated to minimize the adhesion of biomolecules to their surfaces. | For dPCR, "It is important to use low-binding plastics as much as possible... Since digital PCR emphasizes assaying limiting dilution, any sample that sticks... will be lost and skew results" [16]. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows and decision processes for the quantification methods discussed.

Diagram 1: Absolute Quantification Workflows. This diagram contrasts the standard curve (green) and dPCR (red) paths for obtaining absolute copy numbers.

Diagram 2: Relative Quantification via the ΔΔCт Method. This workflow shows the path for calculating fold-change in gene expression relative to a control sample.

Key Applications in Drug Discovery and Clinical Diagnostics

Quantitative PCR (qPCR), also referred to as real-time PCR, has revolutionized molecular biology by providing a method for the accurate and sensitive measurement of gene expression levels [20]. This technique seamlessly combines the amplification power of traditional PCR with real-time detection, allowing researchers to monitor the accumulation of PCR products as the reaction occurs. In the demanding fields of drug discovery and clinical diagnostics, the ability to generate robust, quantitative data is paramount. qPCR meets this need, enabling the detection of even low-abundance transcripts in complex biological samples, which is often critical for identifying subtle but biologically significant changes [20] [21]. Its applications are broad, spanning from gene expression profiling and biomarker discovery to the validation of drug targets and the detection of pathogens with high sensitivity and specificity [20] [21].

The core process for gene expression analysis involves several critical steps: extraction of high-quality RNA, reverse transcription to generate complementary DNA (cDNA), and the amplification and detection of target sequences using fluorescent dyes or probes [20]. A key distinction is made between qPCR (quantification of DNA) and RT-qPCR (reverse transcription quantitative PCR), with the latter involving an additional step of reverse transcribing RNA into cDNA before quantification, making it the standard for gene expression studies [20]. The adoption of this technology in professional settings is driven by its significant advantages over traditional end-point PCR, including the generation of accurate quantitative data, a vastly increased dynamic range of detection, and the elimination of post-PCR processing, which enhances throughput and reduces the potential for contamination [20].

Core Applications in Drug Discovery

Target Identification and Validation

The initial stage of drug discovery relies heavily on identifying and validating potential biological targets, such as specific genes or proteins, whose modulation is expected to have a therapeutic effect. RT-qPCR is an indispensable tool in this phase due to its precision and sensitivity. Researchers use it to quantify changes in gene expression that may be associated with a disease state. For instance, by comparing gene expression profiles in diseased versus healthy tissues, scientists can identify genes that are significantly upregulated or downregulated. These genes become candidates for further investigation as potential drug targets [21]. The technology's ability to verify results from high-throughput screenings, like microarrays, by providing precise, quantitative data on a smaller set of candidate genes ensures that only the most promising targets move forward in the expensive drug development pipeline [20].

Cancer Genomics and Personalized Medicine

In oncology, RT-qPCR has become a cornerstone for enabling personalized medicine. It is extensively used to identify genetic mutations, amplify specific gene sequences, and analyze expression profiles that guide treatment decisions [21]. A prominent example is the detection of HER2 gene amplification in breast cancer patients. The quantification of HER2 expression levels via RT-qPCR helps clinicians determine which patients are likely to benefit from HER2-targeted therapies. Studies have indicated that RT-qPCR-based diagnostics can increase treatment efficacy by up to 30% by ensuring that the right patients receive the right drugs [21]. This application highlights the role of qPCR in moving away from a one-size-fits-all treatment model towards more effective, tailored therapeutic strategies.

Biomarker Discovery and Pharmacodynamics

Biomarkers are measurable indicators of a biological state or condition and are crucial throughout the drug development process. RT-qPCR is widely used for biomarker discovery, helping to identify RNA signatures that correlate with disease prognosis, diagnosis, or response to treatment [20] [21]. Furthermore, during clinical trials, RT-qPCR is employed in pharmacodynamic studies to assess if a drug is engaging its intended target and producing the desired molecular effect. By measuring changes in the expression levels of target genes or pathway-specific genes before and after treatment, researchers can obtain early evidence of a drug's biological activity, informing critical go/no-go decisions [20].

Core Applications in Clinical Diagnostics

Infectious Disease Diagnostics

RT-qPCR remains the gold standard for the detection and quantification of infectious agents, including viruses, bacteria, and fungi [21]. Its role in managing the COVID-19 pandemic underscored its value in public health, enabling the early and precise detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA, which facilitated timely isolation and treatment measures [21]. The technique offers exceptional sensitivity (>95%) and specificity (>99%), with results often available within a few hours [21]. This rapid and reliable turnaround is vital for controlling the spread of contagious diseases and initiating appropriate antiviral or antibacterial therapies. The high throughput capability of modern automated RT-qPCR systems also allows public health laboratories to process large volumes of samples efficiently during outbreaks [22] [21].

Pathogen Detection in Food Safety and Environmental Monitoring

Beyond human diagnostics, RT-qPCR is critical for ensuring public health through food safety and environmental monitoring. Food producers routinely use this technology to detect pathogenic microorganisms like Salmonella, Listeria, and E. coli [21]. The rapid detection capability, providing results within hours rather than days required by traditional culture methods, allows for swift intervention to prevent contaminated products from reaching consumers, thereby reducing the risk of outbreaks and product recalls [21]. Similarly, environmental agencies employ RT-qPCR to track microbial populations in water, soil, and air samples. For example, it is used to detect harmful cyanobacteria in water supplies, helping to prevent toxin outbreaks and assess overall ecosystem health [21].

Essential Methodologies and Protocols

Experimental Workflow and Reagent Solutions

A successful RT-qPCR experiment depends on a series of meticulously executed steps and the use of high-quality reagents. The standard workflow progresses from sample collection and RNA extraction to reverse transcription, qPCR amplification, and finally, data analysis. Below is a visualization of this core workflow, followed by a table detailing the essential reagents required at each stage.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for RT-qPCR Workflow

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Detection Chemistry | SYBR Green dye, TaqMan probes [20] | Monitors accumulation of PCR product in real-time; SYBR Green binds double-stranded DNA, while TaqMan probes offer target-specific detection [20]. |

| Reverse Transcription Enzymes | Reverse transcriptase [20] | Catalyzes the synthesis of complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template, the critical first step in gene expression analysis [20]. |

| PCR Master Mix | DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffers, MgCl₂ [23] | Provides the essential components for efficient DNA amplification during the qPCR step. The performance of the master mix directly impacts PCR efficiency [23]. |

| Primers & Probes | Gene-specific primers, TaqMan assays [20] | Dictate the specificity of the reaction by annealing to the target sequence of interest. Predesigned assays are available for many genes [20]. |

| Reference Genes | ACTB, GAPDH, 18S rRNA [20] | Serve as endogenous controls (housekeeping genes) for data normalization, correcting for variations in RNA input and quality [20]. |

Data Analysis and Quantification Methods

Interpreting RT-qPCR data requires an understanding of the amplification curve and key metrics like the Cycle threshold (Ct). The Ct value is the cycle number at which the sample's fluorescence crosses a threshold line set above the baseline, and it is a relative measure of the target's starting concentration—a lower Ct indicates a higher starting amount [23]. The reaction progresses through exponential, linear, and plateau phases, with the exponential phase providing the most reliable data for quantification [20].

There are two primary methods for quantifying data:

- Absolute Quantification: Used to determine the exact copy number of a target sequence in a sample, such as for viral load measurements or gene copy number determination. This method requires a standard curve of known concentrations [20] [23].

- Relative Quantification: This more common method compares the expression level of a target gene between test and control samples relative to a reference gene. The two main approaches are the Livak (ΔΔCt) method and the Pfaffl method [23]. The Comparative CT (ΔΔCT) method is a widely used form of relative quantification [20].

A critical prerequisite for accurate quantification, especially with the Livak method, is determining the PCR efficiency. Efficiency, ideally between 90-110%, is calculated from a standard curve of serial dilutions. The formula for calculating efficiency is: Efficiency (%) = (10^(-1/slope) - 1) x 100 [23].

The standard workflow for relative quantification using the ΔΔCt method is outlined below.

Table 2: Key Quantitative Data from qPCR Applications

| Application Area | Key Quantitative Metric | Typical Result / Output |

|---|---|---|

| Infectious Disease Diagnostics | Detection of viral/bacterial RNA [21] | Sensitivity >95%, Specificity >99% [21] |

| Cancer Genomics | Gene expression fold-change (e.g., HER2) [21] | Up to 30% increase in treatment efficacy [21] |

| PCR Efficiency Validation | Slope of standard curve [23] | Ideal efficiency: 90–110% [23] |

| Workflow Automation | Miniaturization success rate [22] | >70% success with 1.5x miniaturization [22] |

| Contrast Requirements (WCAG) | Luminosity contrast ratio [24] [25] | Minimum 4.5:1 for large text, 7:1 for standard text [24] [25] |

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

The field of qPCR continues to evolve, with trends pointing toward increased automation, miniaturization, and integration with digital health platforms [21]. Automation of the entire RT-qPCR workflow, from sample preparation to data analysis, reduces manual errors and increases throughput, which is crucial for clinical diagnostics and large-scale drug screening [22] [21]. Studies have successfully automated and miniaturized reactions to 1.5x of the standard volume, maintaining a success rate greater than 70% without compromising data quality or reproducibility, thereby reducing reagent costs and enabling high-density plating [22].

Future advancements are expected to make RT-qPCR more accessible and affordable, with a strong emphasis on point-of-care testing through portable devices and AI-driven data analysis [21]. These innovations will facilitate the decentralization of testing from core facilities to clinics and field settings, expanding the technology's reach in both clinical diagnostics and environmental monitoring [21]. While challenges such as regulatory hurdles and the need for skilled personnel remain, the ongoing integration of qPCR into personalized medicine, agricultural biotechnology, and public health surveillance ensures its position as a versatile and powerful tool in life sciences for the foreseeable future [21].

Real-time PCR, also known as quantitative PCR (qPCR), is a powerful molecular technique that has revolutionized biological sciences and medicine. It allows for the monitoring of the amplification of a targeted DNA molecule during the PCR process, i.e., in real-time, rather than at its end-point [9]. When applied to RNA analysis through reverse transcription, the technique is known as RT-qPCR and serves as one of the most widely used and sensitive methods for gene expression analysis [20]. The accuracy, sensitivity, and quantitative nature of real-time PCR make it indispensable for a range of applications, from diagnostic testing—as underscored by its role as the gold standard for COVID-19 diagnosis—to gene expression profiling, pathogen detection, and biomarker discovery [9] [26]. This technical guide details the core components—instruments, reagents, and software—required to establish a robust real-time PCR platform for gene expression research within drug development and scientific discovery.

Core Instruments: The Real-Time PCR Platform

The real-time PCR instrument, or thermocycler, is the central piece of hardware that facilitates the amplification and simultaneous quantification of nucleic acids. These instruments perform precise thermal cycling to facilitate the DNA amplification process while also containing an optical system to excite fluorophores and measure the resulting fluorescence signal at each cycle [9]. The table below summarizes the key specifications and features of a standard real-time PCR instrument.

Table 1: Key Components and Specifications of a Real-Time PCR Instrument

| Component/Feature | Description and Technical Specifications |

|---|---|

| Thermal Cycler Block | Precisely controls temperature for denaturation, annealing, and extension cycles. Must have high thermal uniformity and rapid heating/cooling rates. |

| Optical Excitation Source | A lamp or LED array to provide light at specific wavelengths to excite the fluorescent dyes. |

| Detection System | A spectrometer or filter-based photodetector (e.g., CCD camera or photomultiplier tube) to capture fluorescence emission. |

| Multi-Channel Detection | The ability to detect multiple fluorophores simultaneously through distinct optical filters, enabling multiplex PCR. |

| Throughput | Defined by the well format (e.g., 96-well, 384-well) and compatibility with automation for high-throughput screening. |

| Software Integration | Onboard software for run setup, data acquisition, and initial analysis (e.g., Ct value determination). |

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and components of a real-time PCR instrument.

Critical Reagents and Chemical Components

The success of a real-time PCR experiment is critically dependent on the quality and composition of the reagents used. These components work in concert within the reaction mix to enable specific and efficient amplification.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Real-Time PCR and RT-qPCR

| Reagent | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Template Nucleic Acids | The target DNA or RNA to be amplified and quantified. | RNA Integrity/Purity: Critical for gene expression (RIN > 8). DNA Contamination: Must be avoided in RT-qPCR [26]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Enzyme that synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA) from an RNA template. | Essential for RT-qPCR; efficiency impacts overall yield [9]. |

| Thermostable DNA Polymerase | Enzyme that synthesizes new DNA strands complementary to the target sequence. | Must be heat-stable (e.g., Taq polymerase). Fidelity and processivity affect efficiency [9]. |

| Oligonucleotide Primers | Short, single-stranded DNA sequences that define the start and end of the target region to be amplified. | Specificity is paramount; designed to avoid primer-dimer formation [27]. |

| Fluorescent Detection Chemistry | A system that generates a fluorescent signal proportional to the amount of amplified DNA. | See Table 3 for details on probe-based vs. dye-based chemistries [9] [20]. |

| dNTPs | Deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dATP, dCTP, dGTP, dTTP); the building blocks for new DNA strands. | Quality and concentration are crucial for efficient amplification. |

| Reaction Buffer | Provides optimal chemical environment (pH, ionic strength) for polymerase activity and stability. | Often includes MgCl₂, a essential cofactor for DNA polymerase. |

Fluorescent Detection Chemistries

The choice of detection chemistry is a fundamental decision that influences the specificity, cost, and multiplexing capability of a real-time PCR assay.

Table 3: Comparison of Common Real-Time PCR Detection Chemistries

| Chemistry Type | Mechanism of Action | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA-Binding Dyes(e.g., SYBR Green) | Intercalates non-specifically into double-stranded DNA, emitting fluorescence when bound [20]. | - Inexpensive- Flexible (no probe needed)- Simple assay design | - Binds to any dsDNA (non-specific products, primer-dimers)- Requires post-run melt curve analysis for specificity verification |

| Hydrolysis Probes(e.g., TaqMan Probes) | A sequence-specific probe with a reporter fluorophore and a quencher. During amplification, the probe is cleaved, separating the fluorophore from the quencher and increasing fluorescence [9] [20]. | - High specificity- Suitable for multiplexing- No need for melt curve analysis | - More expensive- Requires separate probe design for each target- Probe optimization can be complex [27] |

| Other Probe-Based Systems(e.g., Molecular Beacons, Scorpion Probes) | Utilize FRET and stem-loop structures to remain dark when not bound to the specific target sequence, fluorescing only upon hybridization [9]. | - High specificity- Low background signal | - Complex design and synthesis- Generally higher cost |

Software Platforms for Data Acquisition and Analysis

Software is integral to the real-time PCR workflow, serving three primary functions: instrument operation and data acquisition, initial data processing, and advanced statistical analysis for gene expression quantification.

Table 4: Categories of Software in Real-Time PCR Analysis

| Software Category | Core Functions | Examples & Features |

|---|---|---|

| Instrument Control & Acquisition | - Run setup (plate layout, dye definitions)- Control of thermal and optical modules- Real-time fluorescence data collection | Vendor-provided software (e.g., Applied Biosystems QuantStudio, Bio-Rad CFX Maestro). |

| Primary Data Analysis | - Baseline and threshold setting- Determination of Quantification Cycle (Cq or Ct) values- Amplification efficiency calculation from standard curves [28] | Often part of the instrument software. Can also be found in third-party analysis tools. |

| Gene Expression & Advanced Statistical Analysis | - Normalization using reference genes [29]- Relative quantification (e.g., ΔΔCt method) [20] [28]- Statistical comparison between sample groups (t-tests, ANOVA) [29]- Management of data from multiple plates | Dedicated qPCR analysis software (e.g., Thermo Fisher's Relative Quantification App, GenEx, qBase+), R-based packages, or custom analysis in Excel. |

The following diagram outlines the standard data analysis workflow from raw fluorescence to comparative gene expression data.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Relative Quantification of Gene Expression

This protocol outlines the two-step RT-qPCR process for determining the relative change in gene expression between experimental and control samples, a cornerstone of gene expression profiling research [20] [28].

RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription (cDNA Synthesis)

- RNA Extraction: Isolate high-quality total RNA from tissue or cells using a guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform-based method or a silica-membrane spin column kit. Assess RNA purity (A260/A280 ratio ~2.0) and integrity (e.g., using an Agilent Bioanalyzer; RIN > 8.0 is ideal).

- DNase Treatment: Treat the RNA sample with DNase I to remove any contaminating genomic DNA.

- Reverse Transcription (RT):

- For the two-step method, set up a reaction using 0.1–1 µg of total RNA.

- Use either random hexamers (to prime all RNA sequences) or oligo-d(T) primers (to prime only mRNA with a poly-A tail) [20].

- Include reverse transcriptase, dNTPs, and an RNase inhibitor in the reaction mix.

- Incubate according to the enzyme manufacturer's protocol (e.g., 25°C for 10 min, 50°C for 60 min, 70°C for 15 min).

- The resulting cDNA can be diluted and stored for future use.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) Setup and Run

- Assay Design: Design and validate primer pairs (and probes, if used) for both the target gene(s) and one or more validated reference genes (e.g., GAPDH, ACTB, HPRT1). The reference genes must exhibit stable expression across all experimental conditions [29] [28].

- Reaction Mixture: Prepare the qPCR master mix on ice. A typical 20 µL reaction contains:

- 1X PCR buffer (often supplied with the DNA polymerase)

- 2–4 mM MgCl₂ (concentration may require optimization)

- 0.2 mM of each dNTP

- 0.2–0.5 µM of each forward and reverse primer

- 0.5X–1X concentration of fluorescent dye (SYBR Green) or 0.1–0.2 µM of hydrolysis probe

- 0.5–1.25 units of thermostable DNA polymerase

- 2–5 µL of cDNA template (or a standard dilution for a standard curve)

- Experimental Design:

- Include no-template controls (NTCs) for each assay to check for contamination.

- Include an inter-run calibrator (IRC) on each plate if the experiment spans multiple plates to account for plate-to-plate variation [29].

- Perform at least three biological replicates (independent samples) per condition to account for biological variability.

- For each biological replicate, run at least two technical replicates (repeated reactions from the same cDNA sample) to account for pipetting errors [29].

- Thermal Cycling: Run the plate on the real-time PCR instrument using a standard cycling protocol, for example:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2–10 min

- 40–50 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 15 sec

- Annealing/Extension: 60°C for 1 min (acquire fluorescence at this step)

Data Analysis: The ΔΔCt Method for Relative Quantification

The following steps assume the use of the SYBR Green chemistry. If using a probe-based system, the principles are identical.

- Calculate Average Ct: For each biological replicate, calculate the average Ct value from its technical replicates for both the target gene and the reference gene(s).

- Determine PCR Efficiency: For each primer pair, calculate the amplification efficiency (E) using a dilution series of a pooled cDNA sample. The slope of the plot of Ct vs. log (dilution factor) is used in the formula: Efficiency (E) = 10^(-1/slope). An ideal reaction with 100% efficiency has a slope of -3.32 and E = 2. Acceptable efficiency typically ranges from 90% to 110% [28].

- Normalize to Reference Gene(s): Calculate the ΔCt for each sample.

- ΔCt = Ct (Target Gene) - Ct (Reference Gene)

- Normalize to Control Group: Calculate the ΔΔCt for each experimental sample.

- ΔΔCt = ΔCt (Test Sample) - ΔCt (Control Sample)

- Calculate Fold-Change: Calculate the normalized relative quantity (NRQ) or fold-change in gene expression.

- If assuming 100% efficiency (E=2) for all assays: Fold-Change = 2^(-ΔΔCt)

- If using experimentally derived efficiencies (E) [28]: Fold-Change = (Etarget)^(-ΔCt target) / (Ereference)^(-ΔCt reference)

- Statistical Analysis: Perform statistical tests (e.g., t-test, ANOVA) on the ΔCt or log-transformed Fold-Change values to determine if the observed differences in gene expression are statistically significant [29].

The field of gene expression profiling is critically dependent on robust and reliable molecular techniques, with real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) serving as a cornerstone technology for precise quantification of transcript levels. The global market for these technologies is dynamic, characterized by distinct regional trends that influence their adoption, application, and development. This analysis provides a detailed examination of the qPCR and digital PCR (dPCR) markets across two key regions: the established leadership of North America and the rapidly expanding Asia-Pacific landscape. Understanding these regional dynamics is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to navigate the evolving ecosystem of reagents, instruments, and technological capabilities that underpin modern gene expression analysis.

Regional Market Size and Growth Trajectory

The global digital PCR (dPCR) and real-time PCR (qPCR) market is experiencing significant growth, valued at USD 9.4 billion in 2023 and projected to reach USD 14.8 billion by 2029, reflecting a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.1% [30]. Within this global context, North America and Asia-Pacific represent the dominant and the fastest-growing regional markets, respectively.

Table 1: Comparative Regional Market Analysis for qPCR and dPCR

| Region | Market Size (Base Year) | Projected Market Size (Forecast Year) | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North America | USD 1.34 billion (2024) [31] | USD 2.92 billion (2033) [31] | 9.02% [31] | Mature market, technological leadership, high healthcare spending, strong regulatory framework. |

| Asia-Pacific | USD 9.45 billion (2024) [32] | USD 17.79 billion (2032) [32] | 8.23% [32] | Rapid growth, expanding healthcare infrastructure, large patient populations, increasing local manufacturing. |

North America: A Profile of Market Leadership

North America, particularly the United States, continues to be the largest regional market for qPCR and dPCR technologies [30] [33]. This leadership is anchored by several key factors:

- Advanced Healthcare Infrastructure: The region benefits from well-established diagnostic laboratories, widespread adoption of molecular diagnostics, and significant investments in precision medicine [34] [33].

- Substantial R&D Investment: Strong funding from both government agencies (e.g., NIH grants) and private sectors fuels continuous innovation and early adoption of advanced PCR technologies in both clinical and research settings [34] [33].

- Presence of Key Industry Players: Leading companies such as Thermo Fisher Scientific, Bio-Rad Laboratories, and Roche Diagnostics are headquartered or have a major presence in the region, contributing to its technological edge [30] [33].

- Regulatory Agility and Standards: Agencies like the U.S. FDA and CLIA establish stringent yet evolving standards that ensure quality and safety, with recent approvals (e.g., during the COVID-19 pandemic) demonstrating the importance of regulatory pathways in accelerating market access for novel diagnostic tools [34].

Asia-Pacific: A Profile of Rapid Growth

The Asia-Pacific region is emerging as the fastest-growing market for PCR technologies, driven by a confluence of economic and strategic factors [30] [35].

- Healthcare Modernization: Countries like China, India, Japan, and South Korea are investing heavily in modernizing their healthcare infrastructure and molecular diagnostic networks [30] [32].

- Rising Disease Burden and Diagnostic Awareness: The growing prevalence of infectious diseases, cancer, and genetic disorders, coupled with increasing awareness of early disease detection, is creating substantial demand for accurate diagnostic tools like qPCR [32] [36].

- Government Initiatives and Investments: Strategic government investments in public health programs, genomic research, and local biotechnology sectors are accelerating market expansion [32].

- Growth of Local Manufacturing: The presence of local biotech startups and manufacturing facilities is producing more affordable and region-specific PCR systems, making these technologies increasingly accessible [35]. China, in particular, is projected to register the highest growth rate within the region [32].

Core Technical Principles of qPCR for Gene Expression

A thorough understanding of qPCR is fundamental for accurate gene expression profiling. qPCR, also known as real-time PCR, combines the amplification of a target DNA sequence with the simultaneous quantification of the amplified products [20]. Unlike traditional PCR, which provides end-point detection, qPCR monitors the accumulation of PCR products in real-time during the exponential phase of amplification, which provides the most precise and accurate data for quantitation [20].

Reverse Transcription qPCR (RT-qPCR) Workflow

For gene expression analysis, the process begins with RNA. Reverse Transcription qPCR (RT-qPCR) involves converting RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) before the qPCR amplification [20]. This can be performed as a one-step or a two-step procedure, with the two-step method being more common for gene expression studies due to its flexibility in primer selection and the ability to store cDNA for future use [20].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RT-qPCR Gene Expression Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality, intact total RNA from biological samples. | Purity and integrity of RNA are critical; must effectively remove contaminants like polyphenolics and polysaccharides that can inhibit downstream reactions [37]. |

| Reverse Transcriptase | Synthesizes cDNA from an RNA template. | Choice between one-step and two-step RT-qPCR protocols [20]. |

| qPCR Master Mix | Contains DNA polymerase, dNTPs, buffer, and salts necessary for amplification. | Includes fluorescent detection chemistry (e.g., SYBR Green or TaqMan probes) [20]. |

| Sequence-Specific Primers | Amplify the gene of interest. | Must be designed for high specificity and efficiency (90-110%); checked against sequence databases [20]. |

| Fluorescent Detection Chemistry | Reports amplification in real-time. | SYBR Green: Binds double-stranded DNA (non-specific). TaqMan Probes: Sequence-specific hydrolysis probes offer higher specificity [20]. |

| Reference Gene Assays | Provide stable endogenous controls for data normalization. | Crucial for reliable results; genes like ribosomal proteins (e.g., RPL32, RPS18) often show high stability, but this must be validated for specific experimental conditions [38]. |

Diagram 1: RT-qPCR Gene Expression Workflow

Advanced Methodologies and Experimental Design

Quantification Methods in qPCR

When designing a qPCR experiment for gene expression, selecting the appropriate quantification method is paramount. The two primary methods for relative quantitation are:

- Comparative CT Method (ΔΔCT): This method is widely used for determining the relative fold change in gene expression between a test sample and a control sample [20]. It normalizes the C_T (threshold cycle) of the target gene to both a reference gene and the control sample, providing a fold-change value.

- Standard Curve Method (Absolute Quantitation): This method involves creating a standard curve with known concentrations of a target template, allowing for the absolute quantification of the target copy number in unknown samples [20].

The Critical Role of Reference Gene Validation

A key source of inaccuracy in qPCR data is the use of inappropriate reference genes for normalization. Historically, so-called "housekeeping genes" involved in basic cellular functions were assumed to be stable. However, numerous studies have demonstrated that their expression can vary significantly with experimental conditions [38]. It is therefore essential to empirically validate the stability of candidate reference genes for any specific experimental system.

A study on stingless bees, for example, highlighted that ribosomal protein genes (e.g., rpl32, rps5, rps18) exhibited high stability across various conditions, while genes like gapdh and ef1-α showed much greater variability [38]. Researchers should use algorithms like geNorm, NormFinder, and BestKeeper to evaluate the stability of several candidate genes in their specific experimental context before proceeding with full-scale gene expression analysis [38].

Diagram 2: Reference Gene Validation Protocol

Multiplex qPCR

Multiplex qPCR allows for the simultaneous amplification and detection of multiple targets in a single reaction tube by using different fluorescent dyes for each assay [20]. This is highly efficient for applications like analyzing multiple genes or pathways simultaneously, or for including an endogenous control in the same well as the target gene (duplex PCR). While it requires careful optimization to avoid cross-reactivity and to balance amplification efficiencies, it reduces running costs and pipetting errors [20].

Market Outlook and Future Directions

The future of the PCR market is shaped by technological innovation and evolving clinical and research needs. Key trends that will influence gene expression profiling include:

- Technological Convergence and Digital PCR (dPCR): dPCR, which provides absolute quantification without a standard curve by partitioning a sample into thousands of nano-reactions, is gaining traction for applications requiring ultra-sensitive detection, such as liquid biopsies in oncology [34] [30]. While qPCR remains the workhorse for most gene expression applications, dPCR offers advantages for detecting low-abundance transcripts.

- Point-of-Care (POC) Testing and Miniaturization: There is a growing shift toward decentralized healthcare models, driving demand for portable, automated, and user-friendly PCR platforms that can deliver rapid results in clinics, pharmacies, or remote settings [30] [33] [35].

- Digital Integration and Automation: Leading players are investing in cloud-based data management, AI-powered analytics, and fully integrated automated workflows to enhance throughput, reproducibility, and data connectivity in high-throughput laboratories [34] [30].

- Sustainability Initiatives: The market is seeing an increased focus on eco-friendly reagents and reduced plastic consumables, aligning with broader environmental goals [30].

In conclusion, the regional dynamics of the North American and Asia-Pacific PCR markets present a landscape of robust leadership and explosive growth. For the gene expression researcher, this translates into a continuously evolving toolkit. Success hinges not only on accessing these advanced technologies but also on the rigorous application of sound methodological practices, particularly the validation of reference genes, to ensure the generation of accurate and biologically meaningful data.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) has established itself as a cornerstone technology in molecular biology, enabling the accurate and quantitative measurement of gene expression levels by combining the amplification capabilities of traditional PCR with real-time detection [20]. The ability to monitor the accumulation of PCR products as they form provides researchers with precise data for gene expression profiling, verification of microarray results, and detection of genetic mutations [20]. Meanwhile, artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a transformative tool in healthcare, capable of enhancing diagnostics, treatment planning, and predictive analytics by analyzing complex datasets, including electronic health records, medical imaging, and genomic profiles [39]. The integration of AI with qPCR technologies represents a paradigm shift in personalized medicine, allowing for unprecedented precision in gene expression analysis and clinical decision-making. This confluence enables the identification of subtle patterns in gene expression data that would remain undetectable through conventional analysis methods, thereby accelerating the development of tailored therapeutic interventions based on individual molecular profiles.

The evolution of both fields has created a unique opportunity for synergistic advancement. qPCR provides the robust, sensitive quantitative data on gene expression, while AI offers the computational framework to extract meaningful patterns from these complex datasets. This technical guide explores the emerging trends at this intersection, focusing specifically on how AI-driven approaches are revolutionizing real-time PCR data analysis for gene expression profiling in research and clinical applications. By leveraging machine learning and deep learning algorithms, researchers can now overcome traditional limitations in qPCR data interpretation, paving the way for more accurate, efficient, and clinically relevant insights in the era of personalized medicine.

Foundational Principles of qPCR and Data Analysis

Core qPCR Methodology and Key Parameters

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) serves as one of the most widely used and sensitive gene analysis techniques available, with applications spanning quantitative gene expression analysis, genotyping, copy number determination, drug target validation, and biomarker discovery [20]. The fundamental principle underlying qPCR involves monitoring the amplification of DNA in real-time using fluorescent reporter molecules, such as TaqMan probes or SYBR Green dye, which increase in signal intensity as the target amplicon accumulates [20]. Unlike traditional PCR that relies on end-point detection, qPCR measures amplification as it occurs, providing critical data for determining the starting concentration of nucleic acid in a sample.

The qPCR process generates amplification curves that progress through three distinct phases: exponential, linear, and plateau. The exponential phase provides the most reliable data for quantification because the reaction efficiency is highest and most consistent during this period, with exact doubling of product occurring at every cycle assuming 100% reaction efficiency [20]. It is within this exponential phase that the critical parameters for quantification are determined, including the threshold and Ct value. The threshold represents the level of detection at which a reaction reaches a fluorescent intensity above background, while the Ct (threshold cycle) refers to the PCR cycle at which the sample's amplification curve crosses the threshold [20] [40]. The Ct value serves as the primary metric for both absolute and relative quantitation in qPCR experiments, with lower Ct values indicating higher starting concentrations of the target sequence.

Critical Factors in qPCR Data Quality and Interpretation