Machine Learning vs. Deep Learning for Cancer Detection: A Comparative Analysis for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) methodologies for cancer detection, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Machine Learning vs. Deep Learning for Cancer Detection: A Comparative Analysis for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) methodologies for cancer detection, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of both approaches, detailing their application across diverse data modalities including medical imaging, genomics, and clinical records. The scope extends to methodological implementation, troubleshooting common challenges like data scarcity and model interpretability, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing current evidence and performance benchmarks, this analysis aims to guide the selection and optimization of AI tools to accelerate oncological research and the development of precise diagnostic solutions.

Core Concepts and Data Landscapes: Understanding ML and DL in Oncology

In the field of oncology, the choice between classical Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL) architectures is pivotal for developing effective cancer detection tools. Classical ML relies on human-engineered features and often requires less computational power, making it suitable for smaller datasets. In contrast, DL models autonomously learn hierarchical features from raw data, typically achieving superior performance with large-scale, complex data but at a greater computational cost. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these paradigms to inform researchers and developers in selecting the appropriate tool for their specific cancer detection projects [1] [2].

Performance Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes key performance metrics and characteristics of classical ML and DL models as reported in recent cancer detection studies.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ML and DL Models in Cancer Detection

| Cancer Type | Model Category | Best Performing Model(s) | Reported Accuracy | Key Strengths / Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-Cancer (7 types) [3] | Deep Learning | DenseNet121 | 99.94% | Highest accuracy; low loss (0.0017) and RMSE [3]. |

| Brain Tumor [1] | Deep Learning | ResNet18 (CNN) | 99.77% (mean) | Best overall performance and cross-domain generalization (95% accuracy) [1]. |

| Brain Tumor [1] | Deep Learning | Vision Transformer (ViT-B/16) | 97.36% (mean) | Strong performance; captures long-range spatial features [1]. |

| Brain Tumor [1] | Deep Learning | SimCLR (Self-Supervised) | 97.29% (mean) | Effective with limited labeled data; 2-stage training [1]. |

| Brain Tumor [1] | Classical ML | SVM with HOG features | 96.51% (mean) | Competitive on original data; poor cross-domain generalization (80% accuracy) [1]. |

| Lung & Colon [4] | Hybrid (Fusion) | EfficientNetB0 + Handcrafted Features | 99.87% | Combines DL with LBP, GLCM; excellent generalizability [4]. |

| Cancer Risk Prediction (Structured Data) [5] | Classical ML | CatBoost (Ensemble) | 98.75% | Effective on tabular genetic/lifestyle data; handles complex interactions [5]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Understanding the methodology behind these performance metrics is crucial for replication and critical assessment.

This study offers a direct comparison of four distinct model paradigms.

- Objective: To classify brain MRIs into "tumor" or "no tumor" and evaluate model robustness.

- Dataset: 2,870 T1-weighted brain MRIs from Figshare (4 classes: glioma, meningioma, pituitary, no tumor). A separate cross-dataset was used for generalization testing [1].

- Models & Training:

- SVM+HOG: Represented classical ML. HOG features were extracted and fed into a linear SVM classifier [1].

- ResNet18: A standard CNN. The model was fine-tuned with frozen initial layers and used heavy data augmentation (affine transformations, flipping, Gaussian blur) [1].

- Vision Transformer (ViT-B/16): Leveraged self-attention mechanisms. It was pretrained and fine-tuned on the medical image dataset [1].

- SimCLR: A self-supervised learning model. It first learns representations from unlabeled data via contrastive learning, then is fine-tuned on a smaller labeled dataset [1].

- Evaluation: Models were evaluated on a hold-out test set from the primary dataset (within-domain) and a completely separate cross-dataset to assess generalization [1].

This research evaluated multiple advanced DL architectures across seven cancer types.

- Objective: To automate cancer detection and classify seven cancer types from histopathology images.

- Dataset: Publicly available image datasets for brain, oral, breast, kidney, Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia (ALL), lung and colon, and cervical cancer [3].

- Models & Training: Ten pre-trained CNN models (including DenseNet121, DenseNet201, Xception, InceptionV3, VGG19, ResNet152V2) were compared using transfer learning [3].

- Image Preprocessing: A significant part of the methodology involved advanced image segmentation techniques, including grayscale conversion, Otsu binarization, noise removal, and watershed transformation. Contour features (perimeter, area) were also extracted to enhance region identification [3].

- Evaluation: Models were evaluated based on accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) [3].

This study demonstrates a state-of-the-art approach that integrates classical and deep learning.

- Objective: To improve classification of lung and colon cancer histopathology images.

- Dataset: LC25000 dataset, with external validation on NCT-CRC-HE-100K and HMU-GC-HE-30K [4].

- Models & Training:

- Deep Features: Extracted using an extended EfficientNetB0 model [4].

- Classical Features: Handcrafted features were extracted in parallel, including:

- Fusion & Training: A transformer-based attention mechanism was used to fuse the classical and deep features dynamically. The model was trained using an adaptive incremental learning strategy to prevent catastrophic forgetting as new data was introduced [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Tools for Cancer Detection Research

| Item / Solution | Function / Description | Relevance in Cancer Detection |

|---|---|---|

| Whole Slide Imaging (WSI) [6] | High-resolution digital scans of entire histology slides. | Enables digital analysis of tissue morphology; foundational for DL-based pathology. |

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [7] | A public repository of cancer genomics and imaging data. | Provides comprehensive, multi-modal datasets for training and validating ML/DL models. |

| LC25000 Dataset [4] | A balanced dataset of 25,000 images for lung and colon cancer. | A standard benchmark for developing and testing histopathology image classification models. |

| Clustering-constrained Attention Multiple Instance Learning (CLAM) [6] | A weakly-supervised deep learning method. | Analyzes gigapixel WSI scans without dense, pixel-level annotations, streamlining workflow. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Tools [7] [8] | Techniques to interpret model decisions (e.g., saliency maps). | Critical for building clinical trust by visualizing regions of interest identified by "black box" models. |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [7] [2] | Neural networks that generate synthetic data. | Used for data augmentation to balance classes and improve model robustness with limited data. |

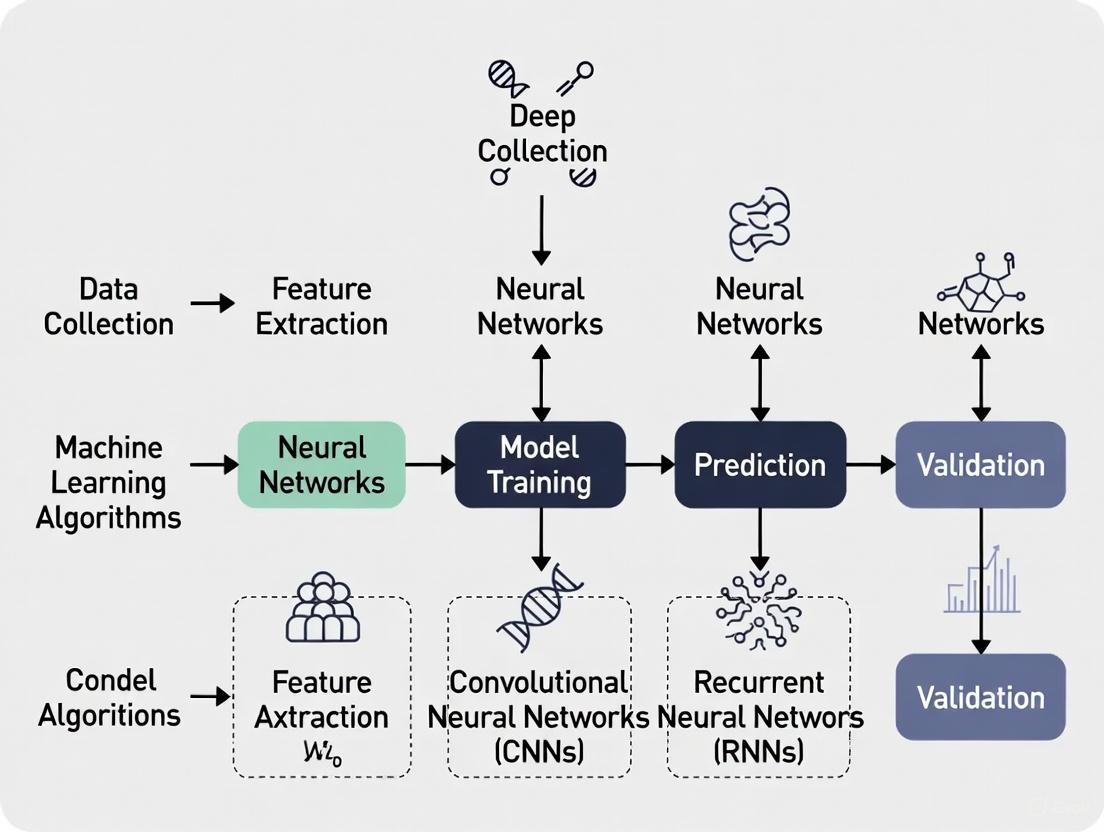

Workflow and Logical Diagrams

The diagrams below illustrate the core architectural and procedural differences between the two paradigms.

Key Selection Guidelines

The optimal model choice depends on the specific research context, driven by data, resources, and project goals.

Choose Classical ML When:

- Working with small to medium-sized datasets (n < 10,000 samples) [1].

- The data is structured or tabular (e.g., patient records with genetic risk, lifestyle factors) [5].

- Computational resources are limited, and model interpretability is a primary concern [1].

- Domain knowledge is strong, allowing for effective manual feature engineering (e.g., using HOG, GLCM) [4].

Choose Deep Learning When:

- Dealing with large-scale, complex data (e.g., high-resolution images, genomic sequences) [3] [2].

- The problem requires automatic feature extraction from raw data, minimizing the need for domain-specific feature engineering [2].

- Maximum predictive accuracy is the critical goal, and sufficient computational resources (e.g., GPUs) are available [3].

- Using pre-trained models with transfer learning can be effectively applied, even if the original labeled dataset is not massive [3] [8].

Consider Hybrid or Advanced Approaches When:

- Aiming for state-of-the-art performance on histopathology images, where fusing classical and deep features has proven highly effective [4].

- Labeled data is scarce, where self-supervised learning (SSL) methods like SimCLR can reduce annotation costs [1].

- Working with multi-modal data (e.g., imaging + genomics), requiring sophisticated fusion strategies [2].

Cancer remains a devastating global health challenge, with nearly 20 million new cases and 9.7 million deaths reported in 2022 alone [9]. The timely and accurate detection of cancer is crucial for improving patient survival rates and treatment outcomes. In contemporary oncology practice, three primary data modalities have emerged as fundamental to cancer detection: medical imaging, genomic data, and clinical records. The integration of artificial intelligence, particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), is revolutionizing how these data modalities are analyzed to detect cancer earlier and with greater precision.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of how ML and DL approaches leverage imaging, genomics, and clinical records for cancer detection. By examining the performance characteristics, implementation requirements, and clinical applications of each modality, we aim to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals about the current landscape and future directions in oncologic AI.

Comparative Analysis of Data Modalities

The table below provides a systematic comparison of the three primary data modalities used in ML/DL approaches for cancer detection.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Data Modalities in Cancer Detection

| Data Modality | Key ML/DL Applications | Reported Performance Metrics | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Imaging [7] [10] | CNNs, Vision Transformers (ViTs) for classification & segmentation | ViTs: 99.92% accuracy (mammography) [10]; CNN/Ensemble models: >97% accuracy [11] [12] | Non-invasive, rich spatial data, enables early detection | Domain shift across institutions, annotation cost, model interpretability |

| Genomics [7] [9] [13] | ML for biomarker discovery; DL for sequencing analysis | Imaging genomics models predict molecular subtypes, therapeutic efficacy [9] | Reveals molecular mechanisms, enables personalized treatment | High cost, complex data integration, tissue heterogeneity |

| Clinical Records [14] [15] | NLP for data extraction; ML for risk stratification & outcome prediction | NLP-derived features outperformed genomic data or stage alone in survival prediction [14] | Real-world data, comprehensive patient context, widely available | Unstructured data, privacy concerns, requires extensive preprocessing |

Detailed Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Medical Imaging Analysis with Deep Learning

Experimental Protocol: A standard workflow for applying DL to medical imaging for cancer detection involves multiple stages of data processing and model development [10].

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Collect large datasets of medical images (e.g., mammograms, MRI, whole-slide images). Apply preprocessing techniques including normalization, resizing, and data augmentation using Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to address class imbalance [10].

- Model Training: Implement Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) such as ResNet or DenseNet for feature extraction. Alternatively, employ Vision Transformers (ViTs) which divide images into patches and use self-attention mechanisms to capture global contextual information [10]. Transfer learning is commonly used by fine-tuning models pre-trained on large datasets like ImageNet.

- Validation: Perform rigorous internal validation using k-fold cross-validation (e.g., stratified k-fold) and external validation on independent datasets from different institutions to assess generalizability [10] [11]. Metrics such as accuracy, AUC, sensitivity, and specificity are reported.

The following diagram illustrates a typical deep learning workflow for medical image analysis in cancer detection.

Integrating Imaging and Genomics (Radiogenomics)

Experimental Protocol: Imaging genomics, or radiogenomics, aims to establish relationships between radiological features and genomic biomarkers [9].

- Data Collection: Acquire matched pairs of medical images (CT, MRI, etc.) and genomic data (from tissue samples or liquid biopsies) from the same patient cohort.

- Feature Extraction: Extract handcrafted radiomic features (e.g., texture, shape) or deep learning-based features from the images. In parallel, process genomic data to identify mutations, gene expression signatures, or other relevant biomarkers.

- Association Mapping and Model Building: Use statistical methods and ML algorithms (e.g., random forests, linear models) to identify significant correlations between imaging features and genomic markers. Build predictive models that can infer genomic status directly from imaging data, which can be less invasive than repeated biopsies [9].

Table 2: Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Radiogenomics

| Item/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PyRadiomics [9] | Open-source platform for extraction of handcrafted radiomic features from medical images. | Standardized feature extraction for association studies with genomic data. |

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [7] | Public repository containing matched clinical, imaging, and genomic data. | Provides a foundational dataset for training and validating radiogenomic models. |

| CNN-based Feature Extractors [9] | Deep learning models that automatically learn relevant features from images. | Used as an alternative to handcrafted features for radiogenomic analysis. |

| Statistical/Machine Learning Models (e.g., Random Forest, Linear Regression) [9] | Algorithms to identify and model correlations between imaging features and genomic data. | Building the core predictive maps linking phenotypes (imaging) to genotypes. |

Leveraging Clinical Records with NLP and Machine Learning

Experimental Protocol: Harnessing real-world data from clinical records requires processing unstructured text and integrating it with structured data [14].

- Data Integration and Harmonization: Combine structured data (medications, demographics, tumor registry) with unstructured free-text from clinician notes, radiology, and pathology reports into a unified dataset (e.g., MSK-CHORD) [14].

- Automatic Annotation with NLP: Train and validate transformer-based NLP models to automatically annotate key features from text. These features include cancer progression, tumor sites, receptor status (e.g., HER2), and smoking history. Rule-based models can be used for more structured information [14].

- Predictive Modeling for Outcomes: Use the annotated, multimodal dataset to train ML models for predicting clinical outcomes like overall survival. Models incorporating NLP-derived features have been shown to outperform those based solely on genomic data or cancer stage [14].

The workflow for building predictive models from clinical records using NLP is shown below.

Discussion and Future Directions

The comparative analysis reveals that each data modality offers distinct advantages and faces unique challenges. Medical imaging is unparalleled for non-invasive, early detection but requires sophisticated DL models to achieve high accuracy. Genomic data provides fundamental insights into disease mechanisms and enables personalized therapy, though integration with other modalities remains complex. Clinical records offer a rich, real-world context that significantly enhances outcome prediction when processed with advanced NLP techniques.

The future of cancer detection lies not in using these modalities in isolation, but in their strategic integration. Multimodal AI, which combines imaging, genomics, and clinical data, holds the greatest promise for building comprehensive and accurate predictive models [7] [14]. Key areas for future development include improving model interpretability through Explainable AI (XAI) [7] [12], addressing data bias to ensure equitable performance across diverse populations [16] [10], and establishing standardized protocols for the clinical validation and deployment of these advanced AI tools [7] [13].

The Rise of Deep Learning in Analyzing Complex Cancer Datasets

The intricate and heterogeneous nature of cancer has long demanded sophisticated analytical approaches. The field of artificial intelligence (AI) has responded with two powerful subsets: classical Machine Learning (ML) and Deep Learning (DL). While ML has established a strong foundation in cancer informatics, DL is now rising to the forefront, demonstrating a remarkable capacity to analyze complex, high-dimensional datasets. This guide provides a comparative analysis of ML and DL models as research tools in cancer detection, framing them within the broader thesis of their respective roles in computational oncology. We objectively compare their performance across various cancer types, detail experimental protocols from key studies, and provide visualizations of core workflows to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the data needed to select appropriate methodologies for their work.

The fundamental distinction lies in their approach to feature handling. ML models typically require domain expertise for manual feature extraction and engineering, such as calculating specific morphological or texture descriptors from images or selecting relevant genomic markers [17]. In contrast, DL models, particularly deep neural networks, autonomously learn hierarchical feature representations directly from raw data, such as whole images or genomic sequences [18] [3]. This capability allows DL to identify subtle, complex patterns often imperceptible to human experts or traditional ML algorithms.

To objectively evaluate the landscape, the table below synthesizes experimental performance data for ML and DL models across several cancer types, as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ML and DL Models in Cancer Detection

| Cancer Type | Best Performing ML Model | Reported ML Accuracy | Best Performing DL Model | Reported DL Accuracy | Key Dataset(s) / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer | Gradient-Boosted Trees [15] | 90.0% | Single-Hidden-Layer Neural Network [15] | 92.86% | Kaggle patient symptom & lifestyle data [15] |

| Multi-Cancer Image Classification | Not Applicable (Benchmark) | N/A | DenseNet121 [3] | 99.94% | Combined dataset of 7 cancer types (Brain, Oral, Breast, etc.) [3] |

| Breast Cancer (Mammography) | Not Directly Compared | N/A | Deep Learning Model (Model B) [19] | AUC: 0.93 | 129,434 screening exams from BreastScreen Norway [19] |

| Leukemia (Microarray Gene Data) | Not Directly Compared | N/A | Weighted CNN with Feature Selection [18] | 99.9% | Microarray gene data; highlights genomic application [18] |

| General Cancer Prediction | Random Forest / Ensemble Methods [17] | Varies (Review) | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) [17] | Generally Higher (Review) | Survey of 191 studies (2018-2023) [17] |

The performance advantage of DL is evident, particularly in tasks involving image and genomic data. The Norwegian breast cancer screening study, a large-scale real-world validation, demonstrated that DL models could identify 93.7% of screen-detected cancers while correctly localizing the lesions [19]. Furthermore, DL excels in multi-cancer classification, with models like DenseNet121 achieving near-perfect accuracy on a complex 7-class image dataset [3]. In genomics, the integration of DL with feature selection techniques has enabled the analysis of tens of thousands of genes, achieving exceptional diagnostic precision for leukemia [18].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Multi-Cancer Image Classification with Transfer Learning

A 2024 study in Scientific Reports provides a robust protocol for using DL to classify seven cancer types from histopathology and radiology images [3].

A. Workflow Overview The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end experimental workflow.

B. Detailed Methodology

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Publicly available image datasets for seven cancer types (brain, oral, breast, kidney, Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia (ALL), lung & colon, and cervical) were collected. Images underwent grayscale conversion and noise removal to standardize quality [3].

- Segmentation and Feature Extraction: The preprocessed images were segmented using Otsu binarization and watershed transformation techniques. Subsequently, contour features—including perimeter, area, and epsilon—were computationally extracted from the identified cancer regions to provide quantitative descriptors for the models [3].

- Model Selection and Training: Ten pre-trained CNN models, including DenseNet121, DenseNet201, Xception, and VGG19, were selected for a transfer learning approach. These models, already trained on large general image datasets like ImageNet, were fine-tuned on the multi-cancer dataset [3].

- Evaluation: Model performance was rigorously evaluated using metrics such as accuracy, loss, precision, recall, F1-score, and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). DenseNet121 emerged as the most effective model, achieving a validation accuracy of 99.94% and the lowest RMSE values [3].

Protocol 2: Lung Cancer Prediction from Symptomatic and Lifestyle Data

A 2025 study offered a direct comparison of ML and DL for lung cancer prediction using non-image data, highlighting the importance of feature engineering for ML [15].

A. Workflow Overview The diagram below contrasts the parallel paths for ML and DL model development.

B. Detailed Methodology

- Data Preparation: A lung cancer dataset from Kaggle containing patient symptoms and lifestyle factors was used. The data was preprocessed through outlier removal and normalization [15].

- Critical Feature Selection: Pearson’s correlation was applied to identify and select the most relevant predictive features from the dataset. This step was noted as crucial for enhancing the accuracy of both ML and DL models, but it was especially critical for the performance of traditional ML algorithms [15].

- Model Training and Comparison: Multiple ML classifiers (Random Forest, SVM, Logistic Regression, etc.) were implemented and compared against neural networks with 1, 2, and 3 hidden layers. The models were evaluated using k-fold cross-validation and an 80/20 train/test split [15].

- Results: The single-hidden-layer neural network, trained for 800 epochs, achieved the highest prediction accuracy of 92.86%, outperforming all the tested traditional ML models [15].

For researchers aiming to replicate or build upon these studies, the following table details key computational reagents and resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for DL in Cancer Detection

| Resource / Tool | Type | Primary Function in Research | Example in Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained CNN Models (DenseNet, VGG, ResNet) | Deep Learning Architecture | Feature extraction and image classification; enables transfer learning, reducing data and computational needs. | DenseNet121 for multi-cancer image classification [3]. |

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Data Repository | Provides large-scale, standardized multi-omics (genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic) and clinical data for model training and validation. | Used as a primary data source in many genomic studies reviewed in [7] [18]. |

| Federated Learning Frameworks | Privacy-Preserving Technique | Enables training ML/DL models across multiple decentralized data sources (e.g., different hospitals) without sharing raw data. | Emerging solution to data privacy and siloing challenges in clinical deployment [7] [18]. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Methods (e.g., SHAP) | Interpretation Tool | Provides post-hoc explanations for "black-box" model predictions, increasing transparency and trust for clinicians. | SHAP used to explain a hybrid CNN-RF model for breast cancer detection [20]. |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Deep Learning Model | Generates synthetic medical data to augment training datasets, helping to address class imbalance and data scarcity. | Used for data augmentation in breast cancer imaging studies [10]. |

The comparative analysis clearly indicates that while classical ML remains a valuable tool, particularly for structured data with expert-derived features, DL has demonstrated superior performance in analyzing the complex, high-dimensional datasets prevalent in modern oncology. Its ability to autonomously learn discriminative features from raw images and genomic sequences has resulted in groundbreaking accuracy in detection and classification tasks.

The future of DL in cancer research hinges on addressing key challenges, including the need for large, diverse, and well-annotated datasets to mitigate bias and improve generalizability [10] [18]. Furthermore, the integration of Explainable AI (XAI) is paramount for translating these powerful "black-box" models into trusted clinical tools [20]. Finally, the emergence of multimodal DL models that can seamlessly integrate imaging, genomic, and clinical data promises to unlock a new era of holistic cancer diagnostics and personalized treatment planning, ultimately advancing the fight against this complex disease [7] [18] [21].

Strengths and Inherent Limitations of ML and DL Approaches

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into oncology represents a paradigm shift in cancer detection, offering unprecedented opportunities to improve diagnostic accuracy, speed, and accessibility [7]. Within the AI landscape, machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) have emerged as pivotal technologies, each with distinct capabilities and limitations for cancer research applications. ML refers to algorithms that automatically learn and adapt from data without explicit programming, while DL is a specialized subset that mimics the human brain using multi-layered neural networks to process complex information [22] [23]. This comparative analysis examines the respective strengths and limitations of ML and DL approaches within cancer detection research, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with evidence-based insights for selecting appropriate methodologies based on specific research contexts and constraints. The framework established in this guide aims to inform strategic decisions in algorithm development and experimental design for oncological applications.

Fundamental Technical Distinctions

ML and DL differ fundamentally in their data processing approaches, architectural complexity, and feature engineering requirements. These technical distinctions directly influence their applicability to different cancer detection scenarios.

Architecture and Feature Engineering: Traditional ML relies on structured data and requires significant human intervention for feature selection and extraction [24]. In contrast, DL operates with deep neural networks that learn directly from raw, often unstructured data, automatically determining relevant features through multiple processing layers [25]. This architectural difference makes DL particularly suited for complex data types like medical images where meaningful features may be difficult to define manually.

Data Requirements and Processing: ML algorithms typically perform well with organized, structured data represented in well-defined variables and can achieve meaningful results with smaller datasets [24]. DL models require substantially larger volumes of data for training but can process and find patterns in unstructured data formats including images, audio, and text without extensive preprocessing [25]. The scalability of DL comes at the cost of computational intensity, typically demanding robust GPU-powered infrastructures not always required for ML implementations [24].

Table: Fundamental Differences Between ML and DL Approaches

| Characteristic | Machine Learning (ML) | Deep Learning (DL) |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirements | Moderate amounts of structured data | Large volumes of unstructured data |

| Feature Engineering | Manual feature extraction required | Automatic feature learning |

| Computational Demand | Lower, can run on CPU systems | High, typically requires GPU acceleration |

| Interpretability | More transparent and explainable | "Black box" nature, less interpretable |

| Infrastructure Needs | Lighter, distributed computing environments | Robust architectures with parallel processing |

Performance Analysis in Cancer Detection

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Rigorous evaluation of ML and DL performance across various cancer types reveals distinct patterns in their detection capabilities. A comprehensive analysis of 130 research studies published between 2018-2023 demonstrated that both approaches can achieve high accuracy, with DL techniques reaching up to 100% accuracy in optimal conditions, while ML techniques achieved a maximum of 99.89% accuracy [26]. However, the lowest accuracy reported for DL was 70%, compared to 75.48% for ML, indicating potentially more significant performance variations in DL applications [26].

For multi-cancer image classification, a 2024 study evaluating ten DL architectures on seven cancer types (brain, oral, breast, kidney, Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia, lung and colon, and cervical cancer) found DenseNet121 achieving the highest validation accuracy at 99.94% with a loss of 0.0017 [3]. The Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) values were 0.036056 for training and 0.045826 for validation, demonstrating exceptional performance in classifying diverse cancer imagery [3].

Table: Performance Comparison Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Best Performing ML Model | Accuracy | Best Performing DL Model | Accuracy | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | Multiple ML Algorithms | 99.89% [26] | DenseNet121 | 99.94% [3] | Intraclass variability, high similarity between malignant and benign cases [27] |

| Skin Cancer | Ensemble Methods | 99.2% [26] | CNN Architectures | 100% [26] | Bias in training data for darker skin tones, equipment variability [22] |

| Brain Tumor | Traditional SVM | 98.5% [26] | Custom CNN | 99.1% [26] | Tumor segmentation complexity, image quality variations |

| Lung Cancer | Random Forest | 97.8% [26] | CNN with CT scans | 98.7% [26] | Nodule detection accuracy, false positive reduction |

Analysis of Performance Patterns

The performance differential between ML and DL approaches varies significantly by data type and complexity. For structured genomic data, ML algorithms often achieve comparable performance to DL with greater efficiency and interpretability [2]. In contrast, DL consistently outperforms ML for image-based cancer detection, particularly with complex unstructured data like histopathology images and CT scans [3]. This performance advantage comes with substantial computational costs and data requirements that must be factored into research planning.

The Mammography Screening with Artificial Intelligence (MASAI) randomized controlled trial demonstrated the real-world impact of these technologies, where an AI system used for triage increased cancer detection rates by 20% while reducing radiologists' workload by half [22]. This illustrates how DL integration can enhance both efficiency and effectiveness in clinical screening scenarios.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Typical DL Experimental Protocol for Image Analysis

Dataset Preparation and Preprocessing: DL experiments typically begin with extensive data collection and augmentation. A standard protocol involves gathering large datasets of medical images, such as the 129,450 biopsy-proven photographic images used in a seminal dermatology study [22]. Images undergo preprocessing including grayscale conversion, Otsu binarization, noise removal, and watershed transformation for segmentation [3]. Contour feature extraction follows, with parameters such as perimeter, area, and epsilon computed to enhance cancer region identification.

Model Architecture and Training: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) represent the most prevalent DL architecture in cancer detection research [2]. The convolution operation follows the mathematical formula: (f ∗ g)(t) = ∫f(τ)g(t-τ)dτ, where f denotes the input image and g represents the filter [2]. Pooling operations, including Max Pooling and Average Pooling, reduce feature map dimensionality while preserving salient features [2]. Transfer learning approaches utilizing pre-trained models like DenseNet121, InceptionV3, and ResNet152V2 have demonstrated particular effectiveness, especially with limited datasets [3].

Validation and Interpretation: Rigorous validation follows training, typically employing k-fold cross-validation and hold-out test sets. Performance metrics including precision, accuracy, F1 score, RMSE, and recall are calculated [3]. For clinical applicability, techniques like Grad-CAM and other explainable AI (XAI) methods provide visual explanations of model decisions, addressing the "black box" limitation inherent in DL approaches [7].

Typical ML Experimental Protocol for Genomic Analysis

Feature Extraction and Selection: ML protocols for genomic cancer detection begin with identifying relevant genetic markers and variations. For whole genome data, researchers often apply effect functions to mutations with location-specific weights, quantified as ∑w_i * f(m_i), where w_i represents the weight of the mutation location and f(m_i) denotes the effect function of the mutation [2]. Feature selection algorithms then identify the most discriminative genetic markers, reducing dimensionality to enhance model performance and interpretability.

Model Training and Optimization: Following feature selection, researchers implement and compare multiple ML algorithms, typically including Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests, and gradient boosting methods. Regularization techniques prevent overfitting by limiting the weight models assign to specific variables, making results more generalizable and accurate [25]. This is particularly crucial with genomic data where the number of features often exceeds sample sizes.

Validation and Clinical Correlation: ML models undergo rigorous validation using techniques like bootstrapping and cross-validation. Performance is assessed through standard metrics with particular attention to clinical applicability. Models are correlated with known clinical outcomes and biological pathways to ensure translational relevance, with mutation signatures in genes like BRCA1 and BRCA2 linked to specific cancer risks and treatment responses [2].

Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of ML and DL approaches in cancer detection relies on specialized computational tools and datasets. The following table details essential research reagents and their functions in developing and validating cancer detection models.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ML/DL Cancer Detection

| Research Reagent | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | Algorithm Architecture | Automatically extracts features from medical images | Analysis of CT scans for lung nodules, mammogram interpretation [2] [22] |

| Whole Slide Images (WSI) | Data Type | Digital pathology slides for model training | Histopathological cancer classification [7] |

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Dataset | Comprehensive genomic database | Identifying mutation patterns across cancer types [7] |

| Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Algorithm Architecture | Generates synthetic data to address class imbalance | Augmenting rare cancer subtype datasets [7] [27] |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Tools | Software Library | Provides model interpretability and decision explanations | Visualizing areas of interest in medical images [7] |

| Federated Learning Frameworks | Deployment Architecture | Enables collaborative training without data sharing | Multi-institutional models while preserving patient privacy [7] |

| Variational Autoencoders (VAE) | Algorithm Architecture | Learns efficient data encodings for dimensionality reduction | Processing high-dimensional genomic data [7] |

Strengths and Limitations Analysis

Machine Learning Strengths and Limitations

Key Strengths:

- Data Efficiency: ML algorithms achieve meaningful results with moderate-sized datasets, making them suitable for rare cancer types where large datasets are unavailable [24]

- Computational Efficiency: ML models require less computational power and can often run on standard CPU-based systems, reducing infrastructure costs [25]

- Interpretability: ML models, particularly those like decision trees and linear models, offer greater transparency in decision-making, which is crucial for clinical adoption and regulatory approval [24]

- Structured Data Excellence: ML excels with structured data types, including genomic sequences and electronic health records, where features can be clearly defined [25]

Inherent Limitations:

- Feature Engineering Dependency: ML performance heavily depends on manual feature engineering and domain expertise to identify relevant variables [24]

- Limited Complex Pattern Recognition: ML struggles with unstructured data like medical images where patterns may be subtle and hierarchical [25]

- Performance Plateau: With complex data types, ML algorithms often reach performance ceilings below what DL can achieve [3]

Deep Learning Strengths and Limitations

Key Strengths:

- Automatic Feature Learning: DL eliminates the need for manual feature engineering by automatically learning relevant features directly from raw data [3]

- Superior Complex Pattern Recognition: DL excels at identifying subtle, hierarchical patterns in unstructured data like histopathology images and CT scans [22]

- State-of-the-Art Performance: For most image-based cancer detection tasks, DL has demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional ML approaches [3]

- Scalability: DL models can improve with more data and benefit from transfer learning approaches that leverage pre-trained models [25]

Inherent Limitations:

- Data Hunger: DL requires large volumes of labeled training data, which can be challenging for rare cancer types or in resource-limited settings [2]

- Computational Intensity: Training complex DL models demands substantial computational resources, typically requiring GPU acceleration [24]

- Black Box Nature: The complexity of DL models makes them difficult to interpret, raising challenges for clinical trust and regulatory approval [7]

- Generalization Challenges: DL models may suffer from performance degradation when applied to data from different institutions or demographic groups [22]

Emerging Solutions and Future Directions

Several innovative approaches are emerging to address the inherent limitations of both ML and DL approaches in cancer detection:

Federated Learning: This approach enables collaborative model training across multiple institutions without sharing sensitive patient data, addressing both data scarcity and privacy concerns [7]. By training models locally and sharing only parameter updates, federated learning facilitates the development of robust models while maintaining data confidentiality.

Explainable AI (XAI): To mitigate the "black box" problem of DL models, XAI techniques provide visual explanations and decision rationales, enhancing clinical trust and adoption [7]. These methods help clinicians understand model decisions and identify potential failure modes before clinical implementation.

Synthetic Data Generation: Generative adversarial networks (GANs) and variational autoencoders (VAEs) can create synthetic medical images to address class imbalance and data scarcity issues, particularly for rare cancer types [7] [27]. This approach enables more robust model training without compromising patient privacy.

Multimodal Data Fusion: Advanced architectures that integrate diverse data types (genomic, imaging, clinical) show promise for more comprehensive cancer detection [2]. These approaches leverage the strengths of both ML and DL for different data modalities within unified frameworks.

Transfer Learning: Leveraging pre-trained models and adapting them to specific cancer detection tasks helps address data limitations and reduces computational requirements [3]. This approach has proven particularly effective in medical imaging applications where labeled data is scarce.

The comparative analysis of ML and DL approaches for cancer detection reveals a nuanced landscape where each methodology offers distinct advantages depending on the specific research context. ML provides interpretability, computational efficiency, and effectiveness with structured data, while DL delivers superior performance with complex unstructured data at the cost of transparency and resource requirements. The optimal approach depends on multiple factors including data type and volume, computational resources, interpretability needs, and specific clinical requirements. Future research directions point toward hybrid methodologies that leverage the strengths of both approaches, with federated learning, explainable AI, and multimodal data fusion addressing current limitations. As these technologies continue to evolve, their thoughtful implementation holds significant promise for advancing cancer detection capabilities and ultimately improving patient outcomes through earlier and more accurate diagnosis.

Algorithmic Implementation and Real-World Clinical Applications

Within computational oncology, the analysis of structured, or tabular, data is a prevalent task, encompassing everything from patient clinical records to genomic data. While deep learning has revolutionized fields like image and speech processing, its superiority is not as pronounced when it comes to structured data [28]. In this domain, traditional machine learning (ML) algorithms often remain the gold standard, demonstrating equivalent or even superior performance compared to more complex deep learning models [28].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of three ML workhorses—Random Forests (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and XGBoost—within the critical context of cancer detection research. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, selecting the right algorithm is not merely an academic exercise; it directly impacts the accuracy of diagnostics and prognostics. We objectively compare these algorithms by synthesizing findings from recent peer-reviewed studies, presenting quantitative performance data, and detailing the experimental protocols used to generate them. The aim is to offer a clear, evidence-based resource for selecting the optimal model for structured data in oncology applications.

Algorithm Fundamentals and Comparative Mechanics

This section breaks down the core principles, strengths, and weaknesses of each algorithm to establish a foundational understanding.

Random Forest

- Core Concept: An ensemble method that constructs a "forest" of numerous decision trees during training [29]. It introduces randomness by training each tree on a different subset of the data and features, a process known as "bagging." For prediction, the outputs of all trees are aggregated—through majority voting for classification or averaging for regression [29].

- Strengths: Highly accurate and robust, resistant to overfitting due to its ensemble nature, handles missing data effectively, and can manage datasets with a wide range of features without significant performance loss [29] [30].

- Weaknesses: Can be computationally expensive with large datasets or a large number of trees, and the ensemble model operates as a "black box," making global interpretability challenging despite the interpretability of individual trees [29].

Support Vector Machine (SVM)

- Core Concept: A powerful classifier that finds the optimal hyperplane in a high-dimensional space to separate data points of different classes with the maximum possible margin [31]. It can handle non-linear relationships through the use of kernel functions, such as the Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel.

- Strengths: Effective in high-dimensional spaces, memory efficient, and versatile due to the kernel trick. It is less prone to overfitting in high-dimensional spaces compared to other algorithms [29] [31].

- Weaknesses: Performance is highly sensitive to the choice of kernel and its parameters (e.g., penalty parameter

Cand RBF kernel parameterσ). It can be less interpretable and does not directly provide probability estimates [31]. It can also be computationally intensive for very large datasets.

XGBoost (Extreme Gradient Boosting)

- Core Concept: An advanced implementation of gradient boosting where new models are created to correct the errors of existing models in a sequential, additive manner [32]. It uses gradient descent to minimize a loss function and incorporates regularization techniques (L1 and L2) to control model complexity and prevent overfitting [29] [32].

- Strengths: Known for its high predictive accuracy and efficiency. It supports parallel processing, can automatically handle missing values, and includes built-in routines for feature importance [32].

- Weaknesses: Can be more susceptible to overfitting on noisy datasets if not properly regularized, and requires careful tuning of hyperparameters [29]. While providing feature importance, the model itself is complex and can be difficult to interpret fully.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of RF, SVM, and XGBoost

| Feature | Random Forest (RF) | Support Vector Machine (SVM) | XGBoost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Mechanism | Bagging of decision trees | Maximum-margin hyperplane | Boosting with gradient descent |

| Primary Strength | Robustness, handles missing data | Effectiveness in high-dimensional spaces | High predictive accuracy & speed |

| Key Weakness | "Black box" model, computational cost | Sensitivity to kernel parameters | Risk of overfitting without tuning |

| Interpretability | Medium (feature importance available) | Low | Medium (feature importance available) |

| Handling Non-Linearity | Inherent (tree splits) | Requires kernel function | Inherent (tree splits) |

Workflow Diagram: Model Training and Optimization

The following diagram illustrates the core training and optimization logic shared by these ML workhorses, highlighting their key differences in approach.

Performance Benchmarking in Cancer Detection

Empirical evidence from recent oncology research demonstrates the practical performance of these algorithms. The following table synthesizes results from multiple studies on different cancer types.

Table 2: Experimental Performance in Cancer Detection Studies

| Cancer Type | Algorithm | Performance Metrics | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | SVM (Optimized with IQI-BGWO) | Accuracy: 99.25%, Sensitivity: 98.96%, Specificity: 100% | [31] |

| Breast Cancer | KNN | High accuracy on original dataset | [33] [11] |

| Breast Cancer | XGBoost (via AutoML) | High accuracy on synthetic dataset | [33] [11] |

| Breast Cancer | Random Forest | Competitively high accuracy | [11] |

| Colorectal Cancer | Stacked RF Model | Specificity: 80.3%, Sensitivity: 65.2% (41% for Stage I) | [34] |

| Gastrointestinal Tract Cancers | Random Forest | Prediction accuracy >80% for survival rates | [30] |

| Cervical Cancer | Multiple ML Models (Pooled) | Sensitivity: 0.97, Specificity: 0.96 | [35] |

Key Insights from Benchmarking

- SVM's Peak Performance: When meticulously optimized, as with the Improved Quantum-Inspired Grey Wolf Optimizer (IQI-BGWO), SVM can achieve state-of-the-art results, as seen in breast cancer diagnosis on the MIAS dataset [31].

- Random Forest's Clinical Robustness: RF consistently demonstrates high accuracy and reliability, particularly in prognostication tasks. A systematic review of GI tract malignancies found RF models outperformed conventional statistical methods, with several studies reporting over 80% accuracy in predicting survival rates [30].

- The Power of Ensemble and Hybrid Strategies: The top-performing models often involve ensembling (like stacked RF [34]) or sophisticated optimization of base algorithms (like SVM with IQI-BGWO [31]). This underscores that model tuning and combination can be as critical as algorithm selection itself.

- Context-Dependent Performance: No single algorithm is universally superior. For example, in one breast cancer study, KNN performed best on the original dataset, while an AutoML approach based on XGBoost excelled on synthetic data [11], highlighting the importance of data characteristics.

Experimental Protocols in Detail

To ensure the reproducibility of results and provide a template for future research, this section details the methodologies from two key studies cited in the benchmarks.

Protocol 1: Optimized SVM for Breast Cancer Diagnosis

This protocol outlines the methodology from the study achieving 99.25% accuracy in breast cancer classification [31].

- 1. Objective: To enhance breast cancer classification accuracy by determining the optimal SVM parameters (RBF kernel parameter

σand error penaltyC) using an improved optimization algorithm. - 2. Dataset: The Mammographic Image Analysis Society (MIAS) dataset was used.

- 3. Preprocessing: Regions of Interest (ROI) were extracted from mammography images. Feature extraction was performed to characterize textures and patterns.

- 4. Optimization Algorithm: An Improved Quantum-Inspired Binary Grey Wolf Optimizer (IQI-BGWO) was developed. This algorithm combines the social hierarchy and hunting behavior of grey wolves with quantum computing concepts (e.g., qubit representation) to improve search capabilities and escape local optima.

- 5. Model Training & Validation: The IQI-BGWO was hybridized with the SVM (IQI-BGWO-SVM). The optimizer's role was to find the optimal (

C,σ) pair that maximized classification performance. The model was evaluated using a 10-fold cross-validation scheme to ensure robustness and avoid overfitting. - 6. Evaluation Metrics: Performance was assessed using mean accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity calculated across the validation folds.

Protocol 2: Stacked Random Forest for Colorectal Cancer Detection

This protocol details the approach used to develop a low-cost, blood-based screening model for colorectal cancer (CRC) [34].

- 1. Objective: To develop a robust machine learning model using Complete Blood Count (CBC) data to predict CRC risk and help prioritize colonoscopy referrals.

- 2. Study Design & Data Collection: A multicenter study was conducted with participants who underwent CBC testing within three months before a colonoscopy. The dataset included 1,795 CRC cases and 26,380 cancer-free individuals.

- 3. Feature Set: The model used 24 CBC features and 5 combined CBC components derived from hematology analyzer data.

- 4. Model Architecture: A stacking ensemble machine learning model was employed. While the core learner was Random Forest, stacking combines multiple base models (e.g., RF, SVM, etc.) using a meta-learner to generate final predictions, potentially capturing complementary patterns.

- 5. Validation: The model underwent external validation, meaning it was tested on data from a different source than it was trained on. This is a rigorous method to evaluate real-world generalizability.

- 6. Evaluation Metrics: Performance was reported using the Area Under the Curve (AUC), specificity, and sensitivity, with a focus on detecting early-stage (Stage I) cancer.

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Cancer Detection

The following diagram generalizes the experimental workflow common to the detailed protocols, providing a blueprint for developing ML models in cancer detection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Success in ML-driven oncology research relies on a suite of "research reagents"—both data and software. Below is a curated list of essential resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ML in Cancer Detection

| Item Name | Type | Function & Application | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Cancer Datasets | Data | Provide standardized, annotated data for model training and benchmarking. | MIAS (Mammography) [31] [36], DDSM/CBIS-DDSM (Mammography) [36], INBreast [36], UCI Breast Cancer [11] |

| Synthetic Data Generators | Data/Software | Augment limited datasets and improve model generalizability by creating realistic synthetic data. | Gaussian Copula (GC), Tabular Variational Autoencoder (TVAE) [11] |

| Optimization Algorithms | Software | Automate the tuning of model hyperparameters to maximize predictive performance. | Improved Quantum-Inspired Grey Wolf Optimizer (IQI-BGWO) [31], Grid Search, Random Search [29] |

| AutoML Frameworks | Software | Automate the end-to-end ML process, from model selection to tuning, reducing manual effort. | H2O AutoML [11], Auto-SKlearn, TPOT [11] |

| Model Interpretation Tools | Software | Provide insights into model decisions, enhancing trust and facilitating clinical adoption. | LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) [29], SHAP, built-in Feature Importance (XGBoost, RF) |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that Random Forests, SVMs, and XGBoost are formidable algorithms for analyzing structured data in cancer research. Their performance is not absolute but is highly dependent on the specific context—the type of cancer, the nature of the data, and, crucially, the rigor of the experimental design and optimization.

- Random Forest stands out for its robustness, ease of use, and consistent high performance, especially in clinical prognostic studies [30].

- SVM remains a powerful choice, capable of achieving top-tier accuracy when its parameters are meticulously optimized, as demonstrated in medical image-based diagnosis [31].

- XGBoost is a highly accurate and efficient algorithm that excels in structured data tasks and is often a key component in winning solutions in data science competitions [32] [11].

The future of ML in oncology lies not in seeking a single dominant algorithm, but in the intelligent application, optimization, and combination of these workhorses. Integrating tools for explainability (XAI) and leveraging synthetic data will be key to translating these powerful models from research benchmarks into trusted tools in clinical practice, ultimately aiding in the early detection and effective treatment of cancer.

In the field of deep learning, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Transformers represent two dominant architectural paradigms, each with distinct inductive biases that make them particularly suited for different types of data. CNNs process information through a hierarchical structure that emphasizes local relationships and translation invariance, making them exceptionally powerful for image analysis and computer vision tasks [37] [38]. In contrast, Transformers utilize self-attention mechanisms to capture global dependencies across entire sequences, establishing themselves as the architecture of choice for sequential data processing, including natural language processing (NLP) and time-series analysis [39] [40]. This architectural divergence creates a natural specialization that has significant implications for applied research, particularly in critical domains such as cancer detection where both imaging data (e.g., histopathology, radiology) and sequential data (e.g., genomic sequences, temporal patient records) play crucial roles.

Understanding the fundamental operational principles of these architectures is essential for selecting the appropriate tool for a given research problem. The comparative analysis of these deep learning powerhouses within cancer research enables more informed model selection, potentially leading to improved diagnostic accuracy, prognostic stratification, and therapeutic discovery. This guide provides an objective comparison of CNN and Transformer architectures, with supporting experimental data and methodological protocols to assist researchers in leveraging these technologies effectively.

Architectural Breakdown: Core Components and Workflows

CNN Architecture for Image Analysis

Convolutional Neural Networks are specifically designed to process data with a grid-like topology, such as images, through a series of convolutional, pooling, and fully-connected layers [41] [38]. The architecture operates on the principle of hierarchical feature learning, where early layers detect simple patterns (edges, colors, textures) and subsequent layers combine these into increasingly complex structures (shapes, objects) [41].

The CNN workflow typically follows this sequence:

- Input Layer: Receives raw pixel values of the image.

- Convolutional Layers: Apply learnable filters that slide across the input, computing dot products to create feature maps that highlight relevant patterns [41] [38]. These layers exploit two key principles: parameter sharing (using the same filter across all spatial positions) and sparse connectivity (each neuron connects only to a local region).

- Activation Functions: Introduce non-linearity to the system, typically using Rectified Linear Units (ReLU) [41].

- Pooling Layers: Perform downsampling operations (e.g., max pooling, average pooling) to reduce spatial dimensions, control overfitting, and provide translational invariance [41] [38].

- Fully-Connected Layers: Integrate extracted features for final classification or regression tasks, often using softmax activation for multi-class prediction [41].

Transformer Architecture for Sequential Data

Transformers process sequential data using an encoder-decoder structure built around self-attention mechanisms, which compute relevance scores between all elements in a sequence regardless of their positional distance [39] [40]. This global receptive field from the start allows Transformers to capture long-range dependencies more effectively than previous sequential models like RNNs and LSTMs.

The key components of the Transformer architecture include:

- Input Embedding and Positional Encoding: Convert input tokens to vectors and inject information about their position in the sequence, essential since Transformers lack inherent recurrence or convolution [39] [40].

- Multi-Head Self-Attention: The core innovation that allows the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces at different positions, calculating weighted sums where weights are determined by compatibility between elements [39] [40].

- Feed-Forward Networks: Apply pointwise fully-connected transformations with non-linear activation to each position separately and identically [39].

- Layer Normalization and Residual Connections: Stabilize training and facilitate gradient flow through deep networks [39].

- Output Layer: Generates probabilities for next-token prediction or sequence classification [39].

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Analysis

Benchmark Performance Across Domains

Table 1: Performance comparison of CNN and Transformer models on standard benchmarks

| Model Architecture | ImageNet Accuracy (Top-1) | GLUE Score (NLP) | Training Efficiency (Image) | Inference Latency | Data Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN (ResNet-50) | 76.0-80.0% [42] | N/A | High [37] | Low [37] | High [37] |

| Vision Transformer (ViT-L/16) | 85.0-91.0% [37] [42] | N/A | Medium [37] | Medium [37] | Low [37] |

| BERT (Transformer) | N/A | 80.5-82.2 [39] | N/A | Medium [40] | Low [43] |

| Hybrid (ConvNeXt) | 87.0-90.0% [37] [42] | N/A | Medium-High [37] | Low-Medium [37] | Medium [37] |

Performance in Data-Constrained Environments

Table 2: Performance comparison with limited training data (critical for medical applications)

| Model Type | <100 Samples | ~1,000 Samples | ~10,000 Samples | >100,000 Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | Moderate[cite:10] | Good[cite:10] | Excellent[cite:1] | Excellent[cite:1] |

| Transformer | Poor[cite:10] | Moderate[cite:10] | Very Good[cite:1] | State-of-the-Art[cite:1] |

The performance characteristics reveal a clear trade-off: CNNs demonstrate superior data efficiency and computational performance with limited data, while Transformers achieve higher asymptotic performance with sufficient data and compute resources [37] [43]. This has direct implications for medical imaging applications, where large, annotated datasets are often difficult to acquire. A 2023 study on radiology report classification found that Transformers required approximately 1,000 training samples to match or surpass the performance of traditional machine learning methods and CNNs [43].

Experimental Protocols for Cancer Detection Research

CNN Protocol for Histopathology Image Analysis

Objective: Classify tumor histology from whole slide images (WSIs) of tissue samples.

Dataset Preparation:

- Collect and annotate WSIs according to standardized cancer grading systems (e.g., Gleason score for prostate cancer, Nottingham grade for breast cancer).

- Perform data augmentation including rotation, flipping, color jittering, and elastic deformations to increase dataset size and improve model robustness.

- Extract patches of 512×512 pixels at 10×-20× magnification, ensuring representative sampling of tumor and normal regions.

Model Training:

- Utilize a pre-trained ResNet-50 or EfficientNet architecture with ImageNet weights.

- Replace the final classification layer with number of classes specific to your cancer grading system.

- Employ progressive training: first freeze backbone and train only classifier, then fine-tune entire network with reduced learning rate.

- Use cross-entropy loss with class weighting for imbalanced datasets.

- Optimize with SGD with momentum (0.9) or AdamW, with learning rate scheduling (cosine annealing).

Evaluation Metrics:

- Calculate accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and area under ROC curve (AUC).

- Perform statistical significance testing using McNemar's test or bootstrapped confidence intervals.

- Conduct attention visualization using Grad-CAM to highlight discriminative regions.

Transformer Protocol for Genomic Sequence Analysis

Objective: Predict cancer type or subtype from DNA/RNA sequencing data.

Data Preprocessing:

- Obtain genomic sequences from sources like TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) or ICGC (International Cancer Genome Consortium).

- Convert nucleotide sequences to tokenized representations (k-mers of length 3-6).

- Add special tokens for sequence start ([CLS]) and separation ([SEP]) following established practices [43].

- Implement padding/truncation to handle variable sequence lengths.

Model Configuration:

- Initialize with domain-specific pre-trained weights (e.g., DNABERT, BioBERT [43]).

- Configure model dimensions: hidden size (768), number of layers (12), attention heads (12).

- Apply dropout (0.1) and layer normalization for regularization.

- Use masked language modeling (MLM) for pre-training if domain adaptation is needed.

Training Procedure:

- Use cross-entropy loss for classification tasks.

- Optimize with AdamW (learning rate: 5e-5) with linear warmup and decay.

- Train with mixed-precision (FP16) to reduce memory usage.

- Implement gradient accumulation for effective batch size adjustment.

Validation Approach:

- Perform k-fold cross-validation (k=5) to account for dataset variability.

- Conduct ablation studies to measure contribution of different components.

- Use t-SNE or UMAP to visualize learned representations.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Implementation

Table 3: Essential research reagents and computational tools for CNN and Transformer experiments

| Category | Specific Tools | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX | Model implementation, training, and inference | Both CNN and Transformer |

| Computer Vision Libraries | OpenCV, scikit-image | Image preprocessing, augmentation, and transformation | Primarily CNN |

| NLP Processing Libraries | Hugging Face Transformers, NLTK, spaCy | Tokenization, text preprocessing, model hub | Primarily Transformer |

| Medical Imaging Tools | ITK, MONAI, PyDicom | Medical image I/O, domain-specific transforms | Primarily CNN |

| Genomic Data Tools | Biopython, BEDTools, SAMtools | Genomic sequence processing and analysis | Primarily Transformer |

| Model Visualization | TensorBoard, Weights & Biases | Experiment tracking, metric visualization | Both CNN and Transformer |

| Interpretability Tools | Grad-CAM, SHAP, LIME | Model decision explanation and validation | Both CNN and Transformer |

Hybrid Architectures: Combining Strengths for Enhanced Performance

The distinction between CNNs and Transformers is increasingly blurred by hybrid architectures that leverage the strengths of both approaches. Models such as ConvNeXt modernize CNN designs by incorporating Transformer-inspired elements [37], while Vision Transformers like DaViT (Dual Attention Vision Transformer) integrate both spatial and channel attention mechanisms [42]. These hybrids demonstrate state-of-the-art performance across multiple benchmarks while maintaining favorable computational characteristics.

In cancer detection research, hybrid approaches show particular promise for multimodal data integration. For instance, a hybrid architecture could use CNN-based encoders for histopathology images alongside Transformer encoders for clinical notes or genomic data, with cross-attention mechanisms enabling information exchange between modalities. This approach captures both local morphological features critical for cancer diagnosis and global contextual relationships that inform prognosis and treatment planning.

The comparative analysis reveals that CNNs and Transformers are complementary rather than competing technologies, with optimal application depending on data characteristics and research objectives. For cancer detection research, the following guidelines emerge:

Select CNNs when working primarily with imaging data (histopathology, radiology), with limited training samples, or under computational constraints. Their inductive biases for spatial locality and translation invariance align well with visual patterns in medical images [37] [38].

Choose Transformers when processing sequential data (genomic sequences, temporal records), when global context is critical, or when large-scale pretraining can be leveraged. Their ability to capture long-range dependencies makes them valuable for integrative analysis [39] [40].

Consider hybrid approaches for multimodal data integration or when seeking state-of-the-art performance without prohibitive computational costs [37] [42].

As deep learning methodologies continue to evolve, the strategic selection and implementation of these architectural paradigms will play an increasingly important role in advancing cancer detection, prognosis prediction, and therapeutic development. Researchers should consider both current performance characteristics and emerging trends when building their analytical pipelines for maximum impact in oncological applications.

Lung cancer remains a leading cause of global cancer mortality, with early detection being critical for improving patient survival rates [15]. The application of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL), has emerged as a transformative approach for early lung cancer prediction using symptomatic and lifestyle data [15] [44]. While ML models have traditionally been used for such predictive tasks, the potential of DL models to automatically learn complex patterns from raw data presents a compelling alternative [45] [46].

This case study provides a systematic comparison of ML and DL approaches for lung cancer prediction based on symptomatic and lifestyle features. We examine their relative performance, optimal application scenarios, and implementation requirements to guide researchers and clinicians in selecting appropriate methodologies for lung cancer risk assessment.

Experimental Protocols and Performance Comparison

Dataset Characteristics and Preprocessing

The foundational dataset for this analysis was sourced from Kaggle and contained patient symptom and lifestyle factors [15]. Prior to model development, rigorous data preprocessing was employed, including:

- Feature selection using Pearson's correlation to identify the most predictive variables

- Outlier removal to enhance data quality

- Normalization to ensure features were on comparable scales [15]

This preprocessing pipeline ensured optimal model training and performance evaluation across both ML and DL approaches.

Machine Learning Implementation

Multiple traditional ML classifiers were implemented using Weka software, including:

- Decision Trees (DT)

- K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN)

- Random Forest (RF)

- Naïve Bayes (NB)

- AdaBoost

- Logistic Regression (LR)

- Support Vector Machines (SVM) [15]

These models were evaluated using K-fold cross-validation and an 80/20 train/test split to ensure robust performance assessment [15].

Deep Learning Implementation

Neural network models with 1, 2, and 3 hidden layers were developed in Python within a Jupyter Notebook environment [15]. These architectures were designed to automatically learn feature representations from the input data without extensive manual feature engineering.

Performance Comparison

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ML and DL Models for Lung Cancer Prediction

| Model Type | Specific Model | Accuracy | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deep Learning | Single-hidden-layer NN (800 epochs) | 92.86% | Superior accuracy with symptomatic/lifestyle data [15] | Requires careful parameter tuning [15] |

| Machine Learning | Stacking Ensemble | 88.7% AUC | Excellent for questionnaire data [47] | Lower accuracy than DL in symptomatic analysis [15] |

| Machine Learning | LightGBM | 88.4% AUC | Handles mixed-type data well [47] | Performance varies with data type [47] |

| Machine Learning | XGBoost, Logistic Regression | ~100% (staging) | Excellent for cancer level classification [48] | Specialized to staging task [48] |

| Deep Learning | 3D CNN (CT scans) | 86% AUROC | Superior with imaging data [45] | Requires volumetric data [45] |

| Deep Learning | 2D CNN (CT scans) | 79% AUROC | Good performance with 2D slices [45] | Lower performance than 3D models [45] |

Key Findings and Interpretation

Performance Analysis

The comparative analysis revealed that a single-hidden-layer neural network trained for 800 epochs achieved the highest prediction accuracy of 92.86% using symptomatic and lifestyle data [15]. This DL model outperformed all traditional ML approaches implemented in the study, demonstrating the advantage of neural networks in capturing complex relationships between patient features and cancer risk [15].

However, the superiority of DL models is context-dependent. In lung cancer staging tasks, traditional ML models like XGBoost and Logistic Regression achieved nearly perfect classification accuracy (approximately 100%), outperforming DL approaches [48]. This suggests that for well-structured clinical data with clear feature relationships, traditional ML models can provide exceptional performance without the complexity of DL architectures.

Impact of Feature Selection

The study highlighted the critical importance of feature selection for enhancing model accuracy across both ML and DL approaches [15]. By employing Pearson's correlation for feature selection before model training, researchers significantly improved predictive performance, underscoring the value of thoughtful feature engineering even in DL approaches.

Data Modality Considerations

The optimal model choice depends heavily on data modality:

- Symptomatic and lifestyle data: DL models showed superior performance [15]

- Structured epidemiological questionnaires: Ensemble ML methods excelled [47]

- CT scan data: 3D DL models outperformed 2D variants [45]

Methodology and Workflow

Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive experimental workflow for comparing ML and DL models in lung cancer prediction:

Model Architecture Comparison

The structural differences between ML and DL approaches significantly impact their application and performance:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for ML/DL Lung Cancer Prediction

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weka | Software Platform | Implementation of traditional ML algorithms [15] | Comparative ML model development |

| Python with Jupyter Notebook | Programming Environment | DL model development and experimentation [15] | Neural network implementation |

| Kaggle Lung Cancer Dataset | Data Resource | Symptomatic and lifestyle features for prediction [15] | Model training and validation |

| NLST (National Lung Screening Trial) Dataset | Data Resource | CT scans and clinical data [45] | Imaging-based model development |

| MATLAB R2024b | Software Platform | Image processing and ML pipeline development [49] [50] | Medical image analysis |

| Scikit-learn Library | Code Library | ML model implementation and hyperparameter tuning [47] | Traditional model development |

This case study demonstrates that both ML and DL approaches offer distinct advantages for lung cancer prediction from symptomatic data. The single-hidden-layer neural network achieved superior performance (92.86% accuracy) compared to traditional ML models, highlighting DL's capability to discern complex patterns in symptomatic and lifestyle data [15]. However, traditional ML models, particularly ensemble methods, remain highly competitive for structured clinical data and cancer staging tasks [48] [47].

The selection between ML and DL approaches should be guided by data characteristics, available computational resources, and specific clinical objectives. DL models show particular promise for complex pattern recognition in heterogeneous symptomatic data, while carefully tuned ML models provide excellent performance for structured clinical variables with greater interpretability. Future research should focus on developing hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both methodologies while enhancing model transparency for clinical adoption.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI), particularly deep learning (DL), into oncology represents a paradigm shift in cancer detection and diagnosis. This case study focuses on the application of DL-driven detection in breast cancer imaging and pathology, situating it within the broader thesis of comparing machine learning (ML) with DL for cancer detection research. While traditional ML models often rely on handcrafted features and can struggle with the complexity and high dimensionality of medical images, DL models, with their hierarchical learning structure, can automatically extract relevant features from raw data, offering a significant performance advantage for complex visual tasks [51]. This analysis will objectively compare the performance of various DL architectures against traditional methods and other alternatives, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Performance Comparison: Deep Learning vs. Alternatives

Deep learning models have demonstrated remarkable accuracy in breast cancer detection across multiple imaging modalities, often surpassing both traditional machine learning methods and human expert performance.

Performance Across Imaging Modalities

Table 1: Performance of DL Models in Breast Cancer Detection Across Different Modalities

| Imaging Modality | Deep Learning Model | Reported Performance | Comparative Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mammography | Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Accuracy: 99.96% [52] | Surpasses traditional mammography sensitivity (77-95%) and specificity (92-95%) [52]. |

| Ultrasound | Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Accuracy: 100% [52] | Higher sensitivity than standard ultrasound (67.2%) [10]. |