Machine Learning in Oncology: Revolutionizing Cancer Risk Prediction and Prognosis for Precision Medicine

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in cancer risk prediction and prognosis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Machine Learning in Oncology: Revolutionizing Cancer Risk Prediction and Prognosis for Precision Medicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in cancer risk prediction and prognosis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of ML in oncology, details advanced methodologies and their specific applications across cancer types, addresses critical challenges and optimization strategies in model development, and offers a comparative analysis of model validation and performance. By synthesizing the latest research and clinical evidence, this review serves as a strategic resource for advancing the development and ethical integration of robust, clinically actionable AI tools in oncology.

The New Frontier: Foundations of Machine Learning in Cancer Prediction

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative force in oncology, enabling the analysis of complex, high-dimensional data to improve cancer risk prediction, diagnosis, and prognosis. As a multifaceted disease driven by genetic and epigenetic alterations, cancer presents unique challenges that traditional statistical methods often struggle to address, particularly with the advent of large-scale genomic data, electronic health records (EHR), and medical imaging [1] [2]. The core ML paradigms—supervised learning, unsupervised learning, and reinforcement learning—offer complementary approaches for extracting meaningful patterns from diverse oncology datasets. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these methodologies, their clinical applications in cancer research, and detailed experimental protocols for implementation, framed within the context of advancing personalized cancer medicine.

Supervised Learning in Oncology

Supervised learning utilizes labeled datasets to train predictive models for classification or regression tasks, making it particularly valuable for oncology applications where historical data with known outcomes exists. This approach has been widely applied to cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and survival prediction [3]. A systematic review of ML techniques for cancer survival analysis found that improved predictive performance was seen from the use of ML in almost all cancer types, with multi-task and deep learning methods yielding superior performance in many cases [1]. Supervised models have been developed to predict cancer susceptibility, recurrence risk, and treatment response using diverse data sources including genomic profiles, clinical features, and medical images [2].

A key application of supervised learning in oncology is survival analysis, which predicts time-to-event outcomes such as mortality or disease progression. Traditional statistical methods like the Cox proportional hazards (CPH) model have limitations including linearity assumptions and difficulties with high-dimensional data, which ML approaches can overcome [1]. ML techniques can capture complex, non-linear relationships between covariates and survival outcomes that traditional methods may miss [1].

Methodological Approaches

Regularized Survival Models: Regularized alternatives to the conventional CPH model have been developed for high-dimensional settings by adding penalty terms to the likelihood function [1]. The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) adds an L1 penalty that encourages sparsity by selecting important covariates and shrinking other coefficients toward zero. Ridge regression adds an L2 penalty that penalizes large coefficients without setting them to zero. Elastic net combines L1 and L2 penalties linearly, allowing both variable selection and coefficient shrinkage [1].

Tree-Based Methods: Tree-based approaches predict survival outcomes by recursively partitioning data into subgroups with comparable risks [1]. At each split, the covariate that maximizes a separation criterion (such as the log-rank test statistic or likelihood ratio test statistic) is selected. These methods can handle complex interactions without pre-specified hypotheses and are robust to non-linear relationships.

Performance Comparison: A systematic review comparing ML methods for cancer survival analysis found that predictive performance varied across cancer types, with no single method universally superior [1]. However, gradient boosting machines (GBM) demonstrated consistently strong performance across multiple cancer types. In one study evaluating prognostic models for several cancers, GBM achieved time-dependent AUCs of 0.783 for 1-year survival in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (aNSCLC), 0.814 for 2-year survival in metastatic breast cancer (mBC), 0.754 for metastatic prostate cancer (mPC), and 0.768 for metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC), outperforming traditional Cox models based on validated prognostic indices [4].

Table 1: Performance of Supervised Learning Models in Cancer Survival Prediction

| Cancer Type | Model | Prediction Timeframe | Performance (AUC) | Benchmark Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| aNSCLC | Gradient Boosting Machine | 1-year survival | 0.783 | Cox Model: 0.689 |

| mBC | Gradient Boosting Machine | 2-year survival | 0.814 | Outperformed Cox model |

| mPC | Gradient Boosting Machine | 2-year survival | 0.754 | Outperformed Cox model |

| mCRC | Gradient Boosting Machine | 2-year survival | 0.768 | Outperformed Cox model |

Experimental Protocol: Survival Prediction with Gradient Boosting Machines

Objective: Develop a GBM model to predict mortality risk from time of metastatic diagnosis.

Data Requirements:

- Input Features: Demographic information, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, cancer biomarkers, serum markers (albumin, hemoglobin, etc.), weight change at diagnosis [4].

- Output: Mortality risk scores representing likelihood of death by specific timepoints (e.g., 1-year for aNSCLC, 2-year for mBC, mPC, mCRC).

- Data Source: Electronic Health Records (EHR) with structured and unstructured data.

Implementation Steps:

- Data Preprocessing: Handle missing values, normalize continuous variables, encode categorical variables.

- Feature Selection: Use recursive feature elimination or domain knowledge-based selection.

- Model Training: Train GBM using survival objective functions (e.g., Cox loss, accelerated failure time).

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Optimize learning rate, maximum depth, number of trees via cross-validation.

- Validation: Assess performance using time-dependent AUC and calibration metrics on holdout test set.

Validation Framework:

- Temporal Validation: Train on earlier time period, validate on later period.

- Cross-Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation to assess model robustness.

- Clinical Validation: Evaluate model in clinical workflow for decision support.

Unsupervised Learning in Oncology

Unsupervised learning operates on unlabeled datasets to discover hidden patterns or structures, making it invaluable for exploratory analysis in oncology where underlying disease mechanisms may not be fully understood [3]. This approach uses clustering to find input regularities and reduce dimensionality, with applications in radiomics, pathology, and molecular subtyping [3]. In cancer research, unsupervised learning has been particularly impactful in identifying novel disease subtypes based on molecular profiles, which can inform treatment strategies and prognosis.

Unsupervised methods can analyze various data types including gene expression, proteomic profiles, and histopathological images to discover molecular patterns that may not be apparent through supervised approaches constrained by existing labels [2]. These techniques help researchers understand cancer biology by revealing intrinsic structures in high-dimensional data without predefined categories or hypotheses.

Methodological Approaches

Clustering Algorithms: Partition patients or samples into groups with similar characteristics using methods such as k-means, hierarchical clustering, or Gaussian mixture models. These can identify novel cancer subtypes with distinct prognostic implications.

Dimensionality Reduction: Techniques like principal component analysis (PCA), t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE), and uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) visualize high-dimensional oncology data in lower-dimensional spaces while preserving meaningful structure.

Deep Representation Learning: Autoencoders and variational autoencoders learn compressed representations of input data that capture essential features for downstream analysis tasks such as subtype discovery or biomarker identification.

Table 2: Unsupervised Learning Applications in Oncology

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Oncology Applications | Key Insights |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clustering | K-means, Hierarchical Clustering | Molecular subtyping, Patient stratification | Identification of novel cancer subtypes with prognostic significance |

| Dimensionality Reduction | PCA, t-SNE, UMAP | Visualization of high-dimensional data, Feature extraction | Discovery of inherent data structures and patterns |

| Deep Representation Learning | Autoencoders, Variational Autoencoders | Biomarker discovery, Feature learning | Learning compressed representations of complex cancer data |

Experimental Protocol: Molecular Subtyping Using Clustering Algorithms

Objective: Identify novel cancer subtypes based on genomic or transcriptomic profiles.

Data Requirements:

- Input Features: Gene expression data, mutation profiles, epigenetic markers.

- Data Source: Tumor sequencing data from repositories like TCGA or institutional biobanks.

Implementation Steps:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize gene expression data, handle missing values, remove low-variance features.

- Feature Selection: Select most variable genes or use pathway-based gene sets.

- Distance Calculation: Compute similarity matrix using appropriate distance metrics (Euclidean, correlation, etc.).

- Clustering: Apply clustering algorithm (e.g., k-means, hierarchical clustering) to group samples.

- Validation: Assess cluster stability using internal validation metrics (silhouette score, Dunn index).

- Biological Characterization: Evaluate clinical relevance of clusters using survival analysis or differential pathway activity.

Interpretation Framework:

- Clinical Correlation: Associate clusters with clinical outcomes (survival, treatment response).

- Pathway Analysis: Identify enriched biological pathways in each cluster.

- Validation: Confirm findings in independent datasets or through functional studies.

Reinforcement Learning in Oncology

Reinforcement learning (RL) focuses on goal-directed learning through interaction with environments, making it particularly suited for dynamic treatment regimes (DTRs) and personalized treatment planning in oncology [3] [5]. RL models learn optimal strategies by receiving rewards or penalties based on actions taken, enabling adaptation to evolving patient responses over time [3]. In clinical practice, RL can optimize sequential decision-making processes for chronic conditions like cancer, where treatments must be adjusted based on patient response and disease progression [5].

RL applications in oncology are concentrated in precision medicine and DTRs, with a focus on personalized treatment planning [3]. Since 2020, there has been a sharp increase in RL research in healthcare, driven by advances in computational power, digital health technologies, and increased use of wearable devices [3]. RL is uniquely equipped to handle complex decision-making tasks required for diseases like cancer that require continuous adjustment of treatment strategies over extended timeframes [3].

Methodological Approaches

Value-Based Methods: Learn the value of being in states and taking actions, then derive policies that maximize cumulative rewards. Q-learning is a prominent example that estimates action-value functions.

Policy Search Methods: Directly learn policies that map patient states to treatment actions without explicitly estimating value functions.

Actor-Critic Methods: Hybrid approaches that combine value-based and policy search methods, using both value function estimation and direct policy optimization [3].

Deep Reinforcement Learning: Combines deep learning with RL frameworks, allowing agents to make decisions from unstructured input data [3]. This approach is particularly valuable for processing complex medical data such as images or time-series signals from wearable devices.

Table 3: Reinforcement Learning Applications in Oncology

| Application Area | RL Methods | Clinical Context | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Treatment Regimes | Value-based methods, Policy search | Chemotherapy dosing, Drug sequencing | Reward specification, Safety constraints |

| Precision Medicine | Deep RL, Actor-Critic | Personalized therapy selection, Biomarker-based treatment | Interpretability, Heterogeneous patient responses |

| Treatment Personalization | Q-learning, Policy gradients | Adaptive radiation therapy, Immunotherapy scheduling | Data scarcity, Ethical considerations |

Experimental Protocol: Dynamic Treatment Regimes for Chemotherapy Optimization

Objective: Learn optimal personalized chemotherapy dosing strategies that maximize survival while minimizing toxicity.

Data Requirements:

- State Space: Tumor measurements, lab values, patient-reported outcomes, performance status.

- Action Space: Dosage adjustments, treatment changes, supportive care interventions.

- Reward Function: Composite measure incorporating tumor response, toxicity metrics, and quality of life.

Implementation Steps:

- Problem Formulation: Define state and action spaces, reward function, and decision timepoints.

- Model Selection: Choose appropriate RL algorithm based on data characteristics and clinical constraints.

- Policy Learning: Train RL agent using historical data or through simulation.

- Policy Evaluation: Assess learned policies using off-policy evaluation methods.

- Safety Validation: Validate safety through clinical review and simulated deployment.

Safety Considerations:

- Conservative Initialization: Start with clinically accepted policies.

- Constraints: Incorporate safety constraints into the learning process.

- Uncertainty Estimation: Quantify uncertainty in recommended actions.

- Clinical Oversight: Maintain human-in-the-loop review of RL recommendations.

Integrated Research Framework

Synergistic Application of ML Paradigms

The three ML paradigms can be integrated to create comprehensive oncology research pipelines. Supervised learning models can identify prognostic biomarkers, unsupervised learning can discover novel disease subtypes, and reinforcement learning can optimize treatment strategies for identified subtypes. This integrated approach facilitates the development of truly personalized cancer care strategies.

The TrialTranslator framework exemplifies this integration, using ML models to risk-stratify real-world oncology patients into distinct prognostic phenotypes before emulating landmark phase 3 trials to assess result generalizability [4]. This approach revealed that patients in low-risk and medium-risk phenotypes exhibit survival times and treatment-associated survival benefits similar to those observed in RCTs, while high-risk phenotypes show significantly lower survival times and treatment-associated survival benefits [4].

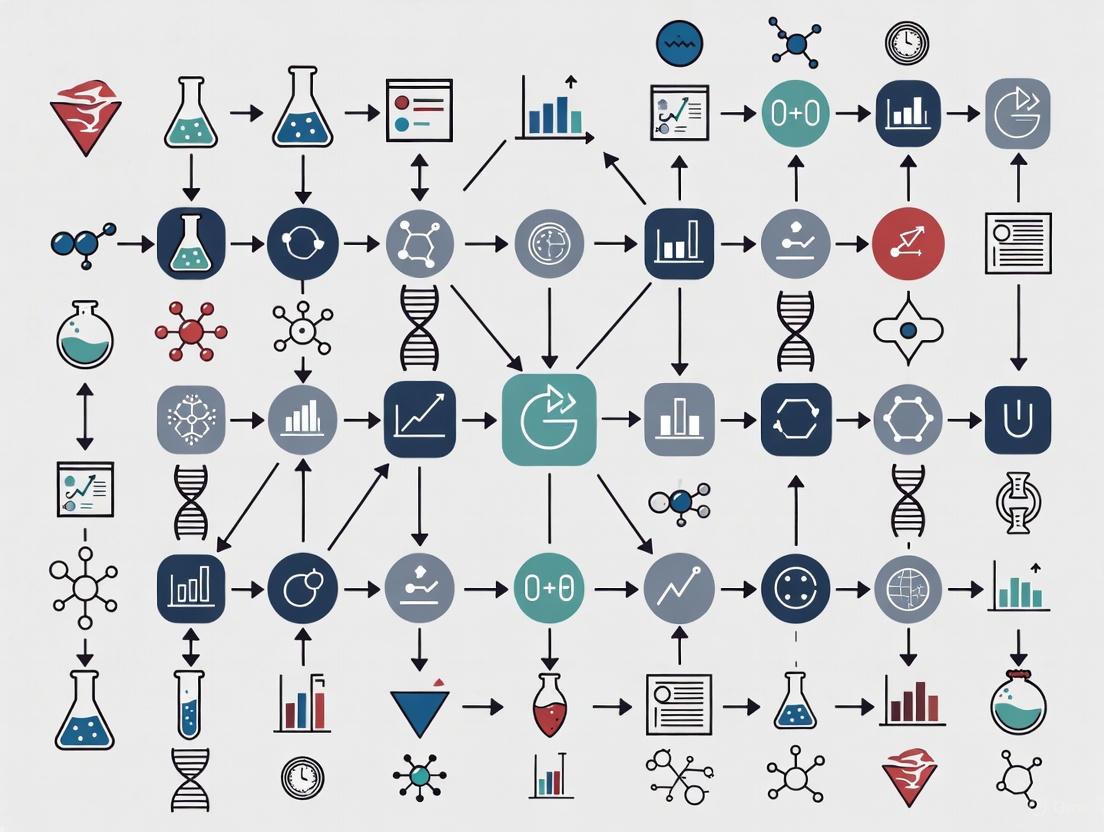

Visualization of ML Workflow in Oncology

ML Workflow in Oncology Research

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for ML in Oncology

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | Flatiron Health EHR database, TCGA, Institutional Biobanks | Provides structured and unstructured data for model development | Data privacy, Quality assurance, Standardization |

| Programming Frameworks | Python, R, Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Enables implementation of ML algorithms and models | Reproducibility, Version control, Documentation |

| Survival Analysis Libraries | Scikit-survival, Lifelines, R survival package | Implements specialized methods for time-to-event data | Censoring handling, Proportional hazards validation |

| Reinforcement Learning Platforms | OpenAI Gym, RLlib, Custom clinical simulators | Provides environments for training and testing RL agents | Safety constraints, Realistic environment modeling |

| Validation Frameworks | Bootstrapping, Cross-validation, Temporal validation | Assesses model performance and generalizability | Data leakage prevention, Clinical relevance assessment |

Future Directions and Challenges

The integration of ML paradigms in oncology faces several challenges, including data heterogeneity, model interpretability, and clinical translation. Future research should focus on developing more robust validation frameworks, improving model transparency for clinical adoption, and addressing ethical considerations in algorithmic decision-making. As ML technologies continue to advance, they hold tremendous potential for transforming cancer care through improved risk prediction, earlier detection, and more personalized treatment strategies [2].

The successful implementation of ML in oncology requires collaborative efforts across disciplines, involving data scientists, clinical researchers, and healthcare providers. By leveraging the complementary strengths of supervised, unsupervised, and reinforcement learning approaches, the oncology research community can accelerate progress toward more effective, personalized cancer care.

Cancer risk assessment has traditionally relied on isolated data streams, such as clinical indicators or family history. However, the multifactorial nature of cancer necessitates an integrated approach that synthesizes information across biological scales—from lifestyle factors to molecular-level genomic data [6]. The emergence of large-scale biomedical databases and advanced computational methods now makes this holistic integration possible, marking a significant evolution in predictive oncology.

This paradigm shift is driven by the understanding that complex diseases like cancer arise from dynamic interactions between genetic susceptibility, environmental exposures, and lifestyle factors [6]. Precision public health aims to provide the right intervention to the right population at the right time by leveraging these multidimensional data [6]. Meanwhile, machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in identifying complex, non-linear patterns within heterogeneous datasets that traditional statistical methods might overlook [7] [8].

This technical guide examines state-of-the-art methodologies for integrating clinical, lifestyle, and genomic data to construct comprehensive cancer risk assessment frameworks. We provide detailed experimental protocols, benchmark performance metrics, and practical toolkits to enable researchers to implement and advance these integrative approaches.

Clinical and Lifestyle Data

Clinical and lifestyle data provide the "macro-level" context for cancer risk assessment. These typically include structured information available through electronic health records (EHRs), population surveys, and clinical assessments.

The Belgian Health Interview Survey (BELHIS) exemplifies a comprehensive data source, containing population-based information on health status, health-related behaviors, use of healthcare facilities, and perceptions of physical and social environment [6]. When augmented with objective measurements from examination-based surveys like the Belgian Health Examination Survey (BELHES), such resources provide valuable multimodal data for risk modeling [6].

Key features frequently utilized in cancer risk prediction models include:

- Demographic factors: Age, gender, socioeconomic status

- Anthropometric measurements: Body Mass Index (BMI)

- Behavioral factors: Smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity levels

- Personal medical history: Previous cancer diagnoses, comorbidities

Genomic and Molecular Data

Molecular data spans multiple "omics" layers that capture biological processes at different resolutions:

- Genomics: DNA sequence variations, including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), copy number variations, and pathogenic germline variants

- Transcriptomics: RNA expression levels, including gene expression and microRNA profiles

- Epigenomics: DNA methylation patterns and chromatin modifications

- Proteomics: Protein expression and post-translational modifications

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and LinkedOmics repository provide curated multi-omics data for various cancer types, enabling researchers to access standardized datasets for method development and validation [9].

Data Linkage Challenges and Solutions

Integrating disparate data sources presents significant technical and ethical challenges. Genomic data is particularly sensitive due to its unique identifying properties, predictive health information, familial implications, and privacy risks [6]. Regulatory frameworks like the GDPR classify genomic data as particularly sensitive, requiring robust encryption, secure data storage, and strict access controls [6].

The implementation of a Belgian pilot study linking genomic data with population-level datasets demonstrated that the process from conceptualization to approval can take up to two years, highlighting the administrative complexity of such integrations [6]. Key challenges include:

- Variability in data access procedures across institutions

- Differences in data standards and formats

- Evolving ethical and legal frameworks for data reuse

Table 1: Data Types for Holistic Risk Assessment

| Data Category | Specific Data Types | Example Sources | Primary Applications in Risk Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical & Lifestyle | Age, gender, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity | BELHIS [6], EHR systems | Identification of modifiable risk factors and population risk stratification |

| Genetic Susceptibility | Genetic risk level, family history, pathogenic germline variants | Commercial genetic testing, research biobanks | Estimation of inherent genetic predisposition |

| Molecular Omics | SCNV, methylation, miRNA, RNAseq | TCGA [9], LinkedOmics | Understanding molecular mechanisms, identifying biomarkers, patient stratification |

| Medical History | Previous cancer diagnoses, comorbid conditions | Cancer registries, clinical databases | Assessment of recurrence risk and secondary cancer development |

Machine Learning Approaches for Integrated Risk Prediction

Traditional and Ensemble Machine Learning Methods

For structured datasets combining clinical, lifestyle, and genetic features, traditional supervised learning algorithms have demonstrated strong performance. A recent study evaluating nine algorithms on a dataset of 1,200 patient records found that Categorical Boosting (CatBoost) achieved the highest predictive performance with a test accuracy of 98.75% and an F1-score of 0.9820, outperforming other models including Logistic Regression, Decision Trees, Random Forest, and Support Vector Machines [7].

Ensemble methods, particularly boosting algorithms, excel at capturing complex interactions between different data types. These algorithms combine multiple simpler models to produce a single prediction with optimal generalization ability [10]. Feature importance analysis from such models consistently identifies cancer history, genetic risk level, and smoking status as the most influential predictors, validating biological and epidemiological knowledge [7].

Multi-Omics Integration with Deep Learning

For integrating high-dimensional molecular data, deep learning approaches offer significant advantages. Autoencoder-based frameworks can learn non-linear representations of each omics data type while preserving important biological information [9].

A proposed multi-omics framework employs autoencoders for dimensionality reduction of each omics layer (methylation, SCNV, miRNA, RNAseq), then applies tensor analysis to the concatenated latent variables for feature learning [9]. This approach effectively addresses the challenge of integrating omics datasets with different dimensionalities while avoiding overweighting of datasets with higher feature counts.

The resulting latent representations can significantly stratify patients into risk groups. For Glioma cancer, this approach separated patients into low-risk (N=147) and high-risk (N=183) groups with statistically significant differences in overall survival (p-value<0.05) [9].

Integrative Interpretation Frameworks

Advanced interpretation frameworks like the Molecular Oncology Almanac (MOAlmanac) enable integrative clinical interpretation of multimodal genomics data by considering both "first-order" and "second-order" molecular alterations [11].

- First-order alterations: Single gene-variant relationships (e.g., BRAF p.V600E)

- Second-order alterations: Interactions between first-order events and global molecular features (e.g., mutational signatures)

MOAlmanac incorporates 790 assertions relating molecular features to therapeutic sensitivity, resistance, and prognosis across 58 cancer types, significantly expanding the landscape of clinical actionability compared to first-order interpretation methods [11].

Multi-Omics Integration Workflow: This diagram illustrates the pipeline for integrating diverse data types through autoencoders and tensor analysis for cancer risk stratification.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

End-to-End ML Pipeline for Structured Data

For datasets combining clinical, lifestyle, and genetic features, a comprehensive ML pipeline includes the following stages:

Data Exploration and Preprocessing

- Handle missing values through imputation or exclusion

- Encode categorical variables (e.g., smoking status, genetic risk level)

- Normalize continuous variables (e.g., age, BMI)

Feature Scaling and Engineering

- Apply standardization to normalize feature ranges

- Create interaction terms between key variables (e.g., age × genetic risk)

Model Training with Cross-Validation

- Implement stratified k-fold cross-validation to preserve class distribution

- Partition data into training (70%) and testing (30%) sets

- Apply SMOTE or similar techniques to address class imbalance if present

Model Evaluation and Interpretation

- Assess performance using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC-ROC

- Employ SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) for feature importance analysis

- Validate on held-out test set to estimate real-world performance

A study implementing this pipeline achieved the best performance with CatBoost, with key predictive features being cancer history, genetic risk, and smoking status [7].

Multi-Omics Integration Protocol

For integrating diverse molecular data types, the following protocol has demonstrated success:

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Download omics data (SCNV, methylation, miRNA, RNAseq) from LinkedOmics or TCGA

- Perform quality control, normalization, and batch effect correction for each omics dataset

- Log-transform RNAseq data and apply beta-mixture quantile normalization for methylation data

Autoencoder Implementation

- Design autoencoder architecture with input layer, bottleneck layer, and output layer

- Train separate autoencoders for each omics type to capture non-linear relationships

- Use mean squared error as reconstruction loss function

- Extract latent variables from bottleneck layer as reduced representations

Tensor Construction and Analysis

- Concatenate latent variables from all omics types to form a multi-omics tensor

- Apply CORCONDIA technique to determine optimal tensor rank

- Perform CP decomposition to extract core features

Risk Group Stratification

- Apply hierarchical clustering to the extracted latent features

- Determine optimal number of clusters using silhouette score or similar metrics

- Validate clustering through survival analysis (Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank test)

This approach has successfully stratified Glioma and Breast Invasive Carcinoma patients into risk groups with significantly different overall survival (p-value<0.05) [9].

Explainable AI for Biomarker Interpretation

Understanding model predictions is crucial for clinical translation. SHAP analysis reveals how specific biomarkers contribute to risk predictions:

- In Glioma, SCNV biomarkers like 9p21.3 show positive SHAP values (0.0170), increasing risk prediction, while 4q12 shows negative values (-0.0243), decreasing risk prediction [9]

- In Breast cancer, miRNA biomarkers like hsa-mir-3935 demonstrate positive SHAP values (0.025), while hsa-mir-202 shows negative values (-0.019) [9]

Table 2: Performance Comparison of ML Algorithms in Cancer Risk Prediction

| Algorithm | Accuracy | F1-Score | AUC-ROC | Best For | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CatBoost | 98.75% [7] | 0.9820 [7] | Not reported | Structured clinical, lifestyle, and genetic data | Less effective for very high-dimensional omics data |

| Autoencoder + Tensor Analysis | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Multi-omics integration, risk stratification | Complex implementation, requires large sample sizes |

| Random Forest | Lower than CatBoost [7] | Lower than CatBoost [7] | Not reported | Feature importance analysis, handling missing data | May overfit without proper tuning |

| MOAlmanac | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Integrative interpretation of multimodal genomics | Focused on interpretation rather than primary prediction |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated Risk Assessment Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Sources | LinkedOmics repository | Provides multi-omics and clinical data for various cancer types | Accessing standardized datasets for method development and validation [9] |

| ML Frameworks | CatBoost | Gradient boosting algorithm for structured data | Predicting cancer risk from clinical, lifestyle, and genetic features [7] |

| Deep Learning Libraries | TensorFlow/PyTorch | Implementing autoencoders for dimensionality reduction | Learning non-linear representations of omics data [9] |

| Interpretation Tools | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | Explaining model predictions and feature contributions | Identifying impactful biomarkers in multi-omics data [9] |

| Integration Frameworks | MOAlmanac | Clinical interpretation algorithm for multimodal genomics | Nominating therapies based on integrative molecular profiles [11] |

| Statistical Analysis | Survival package (R) | Conducting survival analysis and generating Kaplan-Meier curves | Validating risk stratification in patient cohorts [9] |

Method Selection Framework: This diagram provides a decision pathway for selecting appropriate analytical methods based on data types and research objectives.

Validation and Clinical Translation

Validation Strategies

Robust validation is essential for clinically applicable risk models. Recommended approaches include:

- Stratified cross-validation: Preserves class distribution in training and validation sets

- Temporal validation: Assesses model performance on data collected from different time periods

- External validation: Tests models on completely independent datasets from different institutions

- Prospective validation: Evaluates model performance in real-world clinical settings

The ColonFlag AI model represents one of the few commercially available systems for colorectal cancer risk prediction, demonstrating the feasibility of translating these approaches to clinical practice [10].

Clinical Implementation Considerations

Successful clinical translation requires addressing several practical challenges:

- Interpretability: Models must provide explanations for their predictions to gain clinician trust. SHAP and similar XAI techniques are crucial for this purpose [10]

- Regulatory compliance: Systems must comply with evolving regulations like the European Health Data Space (EHDS) implementation [6]

- Integration with clinical workflows: Predictive tools should seamlessly integrate with existing EHR systems and clinical decision processes

- Generalizability: Models must perform consistently across diverse populations and healthcare settings

Future Directions and Challenges

Despite significant progress, several challenges remain in the field of integrated cancer risk assessment:

- Data standardization: Heterogeneous data formats and quality across sources complicate integration

- Sample size requirements: Deep learning approaches typically require large datasets, which may be unavailable for rare cancers

- Privacy concerns: Genomic data presents unique identification risks that require sophisticated protection approaches [6]

- Model transparency: The "black box" nature of complex ML models can hinder clinical adoption

Future research should focus on:

- Developing federated learning approaches that enable model training without data sharing

- Creating more efficient algorithms that require less data for training

- Establishing standards for reporting and validating ML-based prediction models

- Enhancing explainable AI techniques to build clinician trust

The integration of multi-omics data with clinical and lifestyle factors represents the future of cancer risk assessment. As methods continue to mature and datasets grow, these approaches will increasingly enable truly personalized risk prediction and targeted prevention strategies.

In the realm of oncology, machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) have catalyzed a paradigm shift from reactive treatment to proactive prognosis. Predictive modeling now serves as the cornerstone of precision oncology, yet distinct computational frameworks have emerged to address three fundamentally different clinical questions: susceptibility (who will develop cancer), recurrence (who will experience disease return), and survivability (how will the disease progress post-diagnosis). Each focus demands specialized data structures, algorithmic approaches, and validation methodologies tailored to its specific clinical context and temporal orientation.

This technical guide delineates the core differentiators between these predictive foci, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a structured framework for model selection, development, and interpretation. By synthesizing current research and emerging methodologies, we establish a comprehensive taxonomy of cancer prediction models and their appropriate clinical applications.

Cancer Susceptibility Prediction

Definition and Clinical Objective

Cancer susceptibility models identify individuals at high risk of developing cancer before clinical manifestation. These models operate on a preventive timeline, analyzing predisposing factors to enable early intervention strategies. The primary clinical value lies in stratifying populations for targeted screening programs and personalized prevention protocols.

Key Predictive Features and Data Structures

Susceptibility models integrate static and dynamic risk factors collected at a single time point, with feature importance varying by cancer type:

Table 1: Core Feature Categories for Susceptibility Modeling

| Feature Category | Specific Examples | Data Type | Temporal Character |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Profile | Genetic risk level, pathogenic variants (e.g., TP53), polygenic risk scores | Categorical/Continuous | Static |

| Demographic Factors | Age, gender, race/ethnicity | Categorical/Continuous | Static |

| Lifestyle Factors | Smoking status, alcohol consumption, physical activity level | Categorical/Ordinal | Dynamic |

| Clinical Metrics | Body Mass Index (BMI), personal history of cancer, family cancer history | Continuous/Categorical | Static/Dynamic |

| Environmental Exposures | Occupational hazards, radiation exposure, geographic factors | Categorical/Ordinal | Dynamic |

Recent research demonstrates that integrating genetic and modifiable lifestyle factors yields superior predictive performance. A study predicting general cancer risk using lifestyle and genetic data found that cancer history, genetic risk level, and smoking status were the most influential features through importance analysis [7].

Algorithmic Approaches and Performance

Both traditional and ensemble ML methods have been applied to susceptibility prediction, with notable performance differences:

Table 2: Algorithm Performance Comparison for Cancer Susceptibility Prediction

| Algorithm | Accuracy Range | Key Strengths | Interpretability | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | 85-92% | Established baseline, clinical acceptance | High | Low-dimensional data, regulatory contexts |

| Decision Trees | 88-94% | Handles non-linear relationships, visual interpretability | Medium | Feature importance exploration |

| Random Forest | 90-96% | Robust to overfitting, feature importance rankings | Medium | Multimodal data integration |

| Support Vector Machines | 89-95% | Effective in high-dimensional spaces | Low | Genetic data with many features |

| Categorical Boosting (CatBoost) | 95-99% | Handles categorical features natively, high accuracy | Medium | Mixed data types, large datasets |

| Neural Networks | 92-97% | Captures complex interactions, multimodal integration | Low | High-dimensional multimodal data |

In a direct comparison of nine supervised learning algorithms applied to a structured dataset of 1,200 patient records, Categorical Boosting (CatBoost) achieved the highest predictive performance with a test accuracy of 98.75% and an F1-score of 0.9820, outperforming both traditional and other advanced models [7].

Experimental Protocol for Susceptibility Model Development

Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Cohort Definition: Recruit participants with and without cancer incidence

- Feature Extraction: Collect genetic, lifestyle, clinical, and demographic data

- Data Cleaning: Handle missing values, outliers, and data inconsistencies

- Feature Encoding: Transform categorical variables (one-hot, label encoding)

- Data Partitioning: Split into training (70%), validation (15%), and test sets (15%)

Model Training and Validation:

- Algorithm Selection: Choose multiple algorithms from different classes

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Employ grid search or Bayesian optimization

- Cross-Validation: Implement stratified k-fold cross-validation (typically k=5 or k=10)

- Performance Evaluation: Assess using accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, AUC-ROC

- Feature Importance Analysis: Identify most predictive features for clinical interpretation

Implementation Consideration: The full end-to-end ML pipeline should encompass data exploration, preprocessing, feature scaling, model training, and evaluation using stratified cross-validation and a separate test set [7].

Susceptibility Model Workflow

Cancer Recurrence Prediction

Definition and Clinical Objective

Recurrence prediction models forecast the likelihood of cancer returning after initial treatment, addressing a fundamentally different clinical question than susceptibility. These models operate on a monitoring timeline, analyzing post-treatment biomarkers, imaging features, and pathological findings to identify patients who would benefit from adjuvant therapy or intensified surveillance.

Key Predictive Features and Data Structures

Recurrence models incorporate treatment response indicators, longitudinal biomarkers, and tumor microenvironment characteristics:

Table 3: Feature Categories for Recurrence Prediction Across Cancer Types

| Feature Category | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | Breast Cancer | Colorectal Cancer | Prostate Cancer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Biomarkers | TP53, KRAS mutations, PD-L1 expression, circulating tumor DNA | Oncotype DX gene panel, HER2 status, Ki-67 index | Microsatellite instability, CEA levels | PSA kinetics, PTEN deletion, TMPRSS2-ERG fusion |

| Imaging Features | Ground-glass opacities, pleural traction on CT | MRI radiomics, tumor texture, enhancement kinetics | CT texture analysis, liver metastasis features | Multiparametric MRI features, extracapsular extension |

| Pathological Factors | Tumor stage, lymphovascular invasion, surgical margin status | Tumor grade, lymph node involvement, hormone receptor status | TNM stage, lymph node ratio, vascular invasion | Gleason score, surgical margins, perineural invasion |

| Treatment Factors | Type of resection, adjuvant chemotherapy, immunotherapy response | Type of surgery, radiation therapy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy response | Surgical approach, adjuvant FOLFOX/CAPOX | Surgical technique, radiation dose, androgen deprivation |

| Longitudinal Markers | Post-treatment ctDNA clearance, serial imaging changes | Post-treatment MRI changes, serial tumor marker trends | Serial CEA measurements, surveillance CT findings | PSA doubling time, PSA velocity |

For lung cancer, AI models integrating genomic biomarkers (TP53, KRAS, FOXP3, PD-L1, CD8) have demonstrated superior performance compared to conventional methods, with AUCs of 0.73-0.92 versus 0.61 for TNM staging alone [12]. Multi-modal approaches that integrate gene expression, radiomics, and clinical data have achieved even higher accuracy, with SVM-based models reaching 92% AUC [12].

Algorithmic Approaches and Performance

Recurrence prediction benefits from temporal modeling and sophisticated feature integration:

Table 4: Algorithm Performance for Recurrence Prediction

| Algorithm | AUC Range | Clinical Implementation | Data Requirements | Interpretation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Support Vector Machines | 0.85-0.92 | High in specialized centers | Moderate | Medium |

| Random Survival Forests | 0.82-0.89 | Moderate | Moderate | Medium |

| Gradient Boosting Machines | 0.84-0.91 | Growing | Moderate | Medium |

| Neural Networks | 0.83-0.90 | Limited | High | High |

| Multimodal Deep Learning | 0.88-0.96 | Early adoption | High | High |

| Cox Proportional Hazards | 0.75-0.85 | Widespread | Low | Low |

A multimodal deep learning (MDL) model for breast cancer recurrence risk that integrated multiple sequence MRI imaging features with clinicopathologic characteristics demonstrated exceptional performance, achieving an AUC as high as 0.915 and a C-index of 0.803 in the testing cohort [13]. The model accurately differentiated between high- and low-recurrence risk groups, with AUCs for 5-year and 7-year recurrence-free survival (RFS) of 0.936 and 0.956 respectively in the validation cohort [13].

Experimental Protocol for Recurrence Model Development

Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Cohort Definition: Patients with confirmed cancer diagnosis completing initial treatment

- Longitudinal Data Collection: Serial measurements of biomarkers, imaging, clinical assessments

- Outcome Definition: Recurrence-free survival (RFS) or distant metastasis-free survival (DMFS)

- Feature Alignment: Temporal alignment of multimodal data points

- Data Augmentation: Techniques to address class imbalance in recurrence events

Model Training and Validation:

- Algorithm Selection: Prioritize models handling time-to-event data and censoring

- Temporal Validation: Use time-split validation rather than random splits

- Performance Metrics: Focus on time-dependent AUC, Brier score, C-index

- Clinical Calibration: Assess calibration at clinically relevant time points (1, 3, 5 years)

- Decision Curve Analysis: Evaluate clinical utility across risk thresholds

Technical Consideration: Proper stratification of recurrence risk is crucial for guiding treatment decisions. Models must balance sensitivity for high-risk cases while avoiding overtreatment of low-risk patients [13].

Recurrence Prediction Workflow

Cancer Survivability Prediction

Definition and Clinical Objective

Survivability models, also termed prognostic models, predict disease progression and overall survival after cancer diagnosis. These models operate on a trajectory timeline, estimating time-to-event outcomes to inform treatment selection, palliative care planning, and patient counseling about expected disease course.

Key Predictive Features and Data Structures

Survivability models incorporate comprehensive disease burden indicators, host factors, and treatment response metrics:

Table 5: Feature Hierarchy for Survivability Prediction

| Feature Category | Specific Examples | Predictive Strength | Data Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disease Staging | AJCC TNM stage, tumor grade, metastasis presence | Very High | High |

| Host Factors | Age, performance status, comorbidities, nutritional status | High | High |

| Treatment Response | Pathological complete response, RECIST criteria, early biochemical response | High | Medium |

| Molecular Subtypes | Hormone receptor status, HER2 amplification, mutational signatures | High | Medium |

| Genetic Markers | TP53 mutations, tumor mutational burden, specific driver mutations | Medium-High | Low |

| Laboratory Values | Lymphocyte count, albumin, LDH, anemia status | Medium | High |

| Imaging Features | Tumor volume, texture analysis, metabolic activity on PET | Medium | Medium |

A pan-cancer study developing prognostic survival models across ten cancer types found that patient's age, stage, grade, referral route, waiting times, pre-existing conditions, previous hospital utilization, tumor mutational burden and mutations in gene TP53 were among the most important features in cancer survival modeling [14]. The addition of genetic data improved performance in endometrial, glioma, ovarian and prostate cancers, showing its potential importance for cancer prognosis [14].

Algorithmic Approaches and Performance

Survivability prediction requires specialized algorithms that handle censored time-to-event data:

Table 6: Survival Analysis Algorithm Comparison

| Algorithm | C-index Range | Handling of PH Assumption | Complexity | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cox Proportional Hazards | 0.65-0.80 | Requires proportional hazards | Low | Widespread |

| Random Survival Forests | 0.70-0.82 | Assumption-free | Medium | Growing |

| Gradient Boosting Survival | 0.71-0.83 | Assumption-free | Medium | Specialized |

| DeepSurv | 0.69-0.81 | Accommodates non-PH | High | Limited |

| Parametric Models (Weibull, Log-normal) | 0.63-0.78 | Specific distributional assumptions | Low | Niche |

| Multi-task ML Models | 0.73-0.85 | Assumption-free | High | Research |

In a systematic review of ML techniques for cancer survival analysis, improved predictive performance was seen from the use of ML in almost all cancer types, with multi-task and deep learning methods appearing to yield superior performance, though they were reported in only a minority of papers [1]. Most models achieved good performance varying from 60% in bladder cancer to 80% in glioma with the average C-index of 72% across all cancer types [14]. Different machine learning methods achieved similar performance with DeepSurv model slightly underperforming compared to other methods [14].

Experimental Protocol for Survivability Model Development

Data Collection and Preprocessing:

- Study Design: Retrospective or prospective cohort with defined follow-up

- Outcome Definition: Overall survival (OS) or cancer-specific survival

- Censoring Handling: Appropriate handling of right-censored observations

- Time-Varying Covariates: Management of variables that change during follow-up

- Competing Risks: Accounting for non-cancer mortality where appropriate

Model Training and Validation:

- Algorithm Selection: Choose survival-specific algorithms

- Performance Metrics: Focus on C-index, time-dependent Brier score, calibration plots

- Validation Approach: Implement bootstrapping or cross-validation for internal validation

- Benchmarking: Compare against established clinical benchmarks (e.g., TNM staging)

- Clinical Utility Assessment: Decision curve analysis, net benefit analysis

Technical Consideration: Traditional survival methodologies have limitations, such as linearity assumptions and issues pertaining to high dimensionality, which machine learning methods have been developed to overcome towards improved prediction [1].

Survivability Prediction Workflow

Comparative Analysis Across Predictive Foci

Methodological Differentiation

The three predictive foci differ fundamentally in their temporal orientation, data requirements, and analytical approaches:

Table 7: Comparative Analysis of Predictive Foci Methodologies

| Characteristic | Susceptibility Models | Recurrence Models | Survivability Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporal Focus | Pre-diagnosis | Post-treatment | Post-diagnosis |

| Primary Outcome | Binary classification (cancer vs. no cancer) | Time-to-recurrence | Time-to-death |

| Data Structure | Cross-sectional | Longitudinal with baseline + follow-up | Time-to-event with censoring |

| Key Challenges | Class imbalance, feature reliability | Censoring, multimodal integration | Censoring, competing risks |

| Validation Approach | Standard classification metrics | Time-dependent AUC, C-index | C-index, calibration plots |

| Clinical Action | Risk stratification for screening | Adjuvant therapy decisions | Treatment intensity, palliative care |

| Ethical Considerations | Privacy of genetic data, psychological impact | Overtreatment vs. undertreatment | Prognostic disclosure, hope |

Integration of Multimodal Data

The most advanced models across all three foci increasingly leverage multimodal data integration:

Imaging and Text Integration: The MUSK (multimodal transformer with unified mask modeling) AI model developed at Stanford Medicine demonstrates the power of integrating visual information (medical images) with text (clinical notes). This model outperformed standard methods in predicting prognoses across diverse cancer types, identifying patients likely to benefit from immunotherapy, and pinpointing those at highest recurrence risk [15].

Genomic and Clinical Data Integration: A pan-cancer study incorporating genetic data from the 100,000 Genomes Project linked with clinical and demographic data showed that addition of genetic information improved performance in several cancer types, particularly endometrial, glioma, ovarian and prostate cancers [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 8: Essential Research Resources for Cancer Prediction Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Solutions | Function in Research | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Data Platforms | Oncotype DX, FoundationOne, 100,000 Genomes Project | Standardized molecular profiling, gene expression analysis | Cost, tissue requirements, turnaround time |

| Medical Imaging Tools | 3D Slicer, PyRadiomics, ITK-SNAP | Radiomic feature extraction, image segmentation | Standardization across scanners, segmentation variability |

| Natural Language Processing | BERT-based models, CLAMP, cTAKES | Clinical text processing, feature extraction from EMRs | De-identification, handling clinical jargon |

| Survival Analysis Software | survival R package, scikit-survival, PySurvival | Time-to-event analysis, survival model implementation | Censoring handling, proportional hazards validation |

| Multimodal Integration Frameworks | MUSK architecture, early fusion/late fusion approaches | Integrating disparate data types (images, text, genomics) | Alignment, missing data, computational complexity |

| Model Interpretation Tools | SHAP, LIME, partial dependence plots | Model explainability, feature importance visualization | Computational intensity, clinical interpretability |

Future Directions and Research Opportunities

Dynamic Prediction Models

Traditional static models are increasingly being supplemented by dynamic prediction approaches that update prognosis as new data becomes available during patient follow-up. Analysis of dynamic prediction model (DPM) applications revealed seven DPM categories: two-stage models (most common at 32.2%), joint models (28.2%), time-dependent covariate models (12.6%), multi-state models (10.3%), landmark Cox models (8.6%), artificial intelligence (4.6%), and others (3.4%) [16]. The distribution of DPMs has significantly shifted over 5 years, trending towards joint models and AI [16].

Federated Learning and Multi-Institutional Collaboration

The challenges of data privacy, heterogeneity, and small sample sizes for rare cancers are driving interest in federated learning approaches that enable model training across institutions without sharing raw patient data. This is particularly relevant for recurrence prediction where multi-institutional datasets can significantly enhance model generalizability.

Clinical Integration and Trustworthy AI

Future research must address the translational gap between model development and clinical implementation. Key challenges include standardization, regulatory approval, clinician trust, and workflow integration. Explainable AI approaches that provide interpretable predictions will be essential for clinical adoption, particularly for high-stakes decisions such as adjuvant therapy recommendations based on recurrence risk.

The differentiation between susceptibility, recurrence, and survivability prediction represents a fundamental taxonomy in cancer forecasting, with each focus demanding specialized methodological approaches tailored to distinct clinical questions and temporal frameworks. Susceptibility models leverage genetic and lifestyle factors for risk stratification; recurrence models integrate longitudinal multimodal data for post-treatment monitoring; and survivability models employ time-to-event analysis for prognosis estimation. The most impactful advances emerge from multimodal data integration, dynamic modeling approaches, and careful attention to each focus's unique clinical context and implementation requirements. As these fields mature, the convergence of richer datasets, more sophisticated algorithms, and thoughtful clinical integration will progressively enhance our capacity to forecast cancer outcomes across the disease continuum.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) into oncology represents a paradigm shift in cancer research, diagnosis, and treatment. The efficacy of these computational models is fundamentally constrained by the quality, volume, and diversity of the data used for their training. The contemporary data landscape for oncology AI is inherently multimodal, primarily leveraging three critical data types: Electronic Health Records (EHRs), genomic data, and medical imaging [17] [18]. Each data modality offers a unique and complementary perspective on the complex biology of cancer. EHRs provide a longitudinal view of patient health status, treatments, and outcomes; genomics reveals the molecular and hereditary underpinnings of disease; and medical imaging offers detailed structural and functional characterization of tumors [19]. The convergence of these data streams creates a comprehensive informational substrate from which ML models can learn to identify subtle patterns, predict cancer risk with high accuracy, and forecast patient prognosis [7] [2].

The central challenge—and opportunity—in modern oncology research lies in the effective harmonization of these disparate data types. This process, known as multimodal data fusion, aims to provide a more holistic view of a patient's disease than any single data source can offer [18]. However, this integration is non-trivial, presenting significant technical hurdles related to data heterogeneity, scale, and interpretation. This guide details the characteristics of each core data type, outlines methodologies for their processing and integration, and provides experimental protocols for developing robust, data-driven models in cancer research. The ultimate goal is to enable the development of precise, personalized risk assessment and prognostic tools that can transform patient care [17] [20].

Data Source Characteristics and Preprocessing

Electronic Health Records (EHRs)

EHRs are structured and unstructured digital records of patient health information generated during clinical encounters. They are a foundational data source for understanding patient history, comorbidities, and treatment trajectories.

- Key Data Elements: EHRs typically contain patient demographics, vital signs, laboratory results, medication histories, procedure codes (e.g., ICD-10), progress notes, and clinical narratives [20] [19].

- Role in Model Training: In cancer risk prediction and prognosis, EHR data is used to identify populations at high risk, stratify patients based on clinical factors, and track long-term outcomes. Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques are often applied to extract meaningful information from unstructured clinical notes [19].

- Preprocessing Challenges and Techniques: A major challenge is the presence of missing data, inconsistent formatting, and noise. Preprocessing involves:

- Structured Data: Handling missing values (e.g., via imputation or indicator flags), normalizing numerical values, and encoding categorical variables.

- Unstructured Data: Utilizing NLP pipelines for tokenization, named-entity recognition (NER) to identify medical terms, and sentiment analysis to gauge clinical context from narrative text [21].

Table 1: Key Characteristics and Preprocessing of EHR Data for Cancer ML Models

| Data Category | Specific Examples | Primary Use in ML | Common Preprocessing Steps |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | Age, gender, ethnicity | Risk stratification, bias mitigation | One-hot encoding, normalization |

| Clinical History | Smoking status, BMI, alcohol intake [7] | Feature engineering for risk prediction | Boolean encoding, binning continuous variables |

| Laboratory Values | Complete blood count, tumor markers | Prognostic modeling, treatment response | Handling missing data, outlier removal, normalization |

| Medications & Procedures | Chemotherapy drugs, surgery codes | Treatment outcome analysis | Multi-hot encoding, temporal feature extraction |

| Clinical Notes | Pathology reports, discharge summaries | Phenotyping, comorbidity identification | NLP (Tokenization, NER, TF-IDF, BERT embeddings) |

Genomic Data

Genomic data provides insights into the molecular mechanisms of cancer, from inherited susceptibility (germline mutations) to acquired somatic mutations that drive tumorigenesis.

- Key Data Elements: This includes data from Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS), Whole Exome Sequencing (WES), RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq), and targeted panels. Key features are single nucleotide variants (SNVs), copy number variations (CNVs), gene expression levels, and structural variants [18].

- Role in Model Training: Genomic features are paramount for precision oncology. They are used to classify cancer subtypes, predict responsiveness to targeted therapies and immunotherapies, and assess inherited cancer risk [17] [19]. Deep learning models can identify patterns in high-dimensional genomic data that are imperceptible to traditional statistical methods.

- Preprocessing Challenges and Techniques: Genomic data is characterized by its extremely high dimensionality (tens of thousands of genes) and a low sample size relative to the number of features, which risks model overfitting.

- Sequencing Data: Processing begins with raw sequencing reads (FASTQ files), which undergo quality control (e.g., FastQC), alignment to a reference genome (e.g., using BWA), and variant calling (e.g., using GATK) to generate a structured variant call format (VCF) file.

- Downstream Analysis: Critical steps include feature selection (e.g., using mutual information or LASSO regression) to reduce dimensionality and focus on the most informative genes or variants [2] [20]. Normalization (e.g., TPM for RNA-Seq, log-transformation) is essential for cross-sample comparison.

Table 2: Genomic Data Types and Processing Workflows for Cancer Models

| Data Type | Source Material | Key Information | Standardized Processing Pipelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | DNA (Tumor/Normal) | Germline & somatic mutations, structural variants | BWA-MEM (Alignment) -> GATK (Variant Calling) -> ANNOVAR (Annotation) |

| RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) | RNA (Tumor) | Gene expression levels, fusion genes, splice variants | STAR (Alignment) -> FeatureCounts (Quantification) -> DESeq2/edgeR (Normalization) |

| Methylation Arrays | DNA (Tumor) | Epigenetic regulation, gene silencing | minfi (Preprocessing) -> DMRcate (Differential Methylation) |

Medical Imaging Data

Medical images provide a non-invasive window into the in vivo morphology and physiology of tumors.

- Key Data Types: Common modalities include Computed Tomography (CT), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Positron Emission Tomography (PET), mammography, and digital histopathology slides [18] [19].

- Role in Model Training: Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are the cornerstone of image analysis in oncology. They are used for tasks such as tumor detection (e.g., lung nodules on CT), segmentation (delineating tumor boundaries), classification (benign vs. malignant), and predicting molecular subtypes from histopathology images (a field known as radiomics or pathomics) [18] [19].

- Preprocessing Challenges and Techniques: A primary challenge is data heterogeneity stemming from different scanners, protocols, and resolutions. Preprocessing is critical for model generalization.

- Standardization: Steps include resampling to isotropic voxels, co-registration of multi-modal scans (e.g., CT-PET), and intensity normalization (e.g., Z-scoring).

- Augmentation: To increase data diversity and prevent overfitting, techniques like random rotation, flipping, cropping, and elastic deformations are applied during model training.

Multimodal Data Integration Strategies

The fusion of EHR, genomic, and imaging data is where the most significant potential for discovery lies, as it mirrors the multi-faceted nature of cancer itself. Several computational strategies exist for this integration.

Diagram 1: Multimodal data fusion workflow for oncology AI.

Early Fusion (Feature-Level Integration)

This approach involves combining raw or preprocessed features from different modalities into a single, unified feature vector before feeding it into a machine learning model.

- Methodology: For example, quantitative features extracted from a CT scan (radiomics), such as tumor texture and shape, can be concatenated with key EHR variables (e.g., age, smoking status) and a panel of gene expression values to form one large input vector for a classifier like a Support Vector Machine (SVM) or Random Forest [18].

- Advantages: Allows the model to learn from correlations between features of different types from the outset.

- Disadvantages: Highly susceptible to the curse of dimensionality and requires careful normalization and handling of missing data across modalities. The model's performance can be degraded if one data type is noisier than the others.

Late Fusion (Decision-Level Integration)

In this strategy, separate models are trained on each data modality independently, and their predictions are combined at the final stage.

- Methodology: A CNN might be trained on histopathology images to predict cancer recurrence, while a separate gradient boosting model (e.g., XGBoost) is trained on EHR and genomic data for the same task. The outputs (e.g., probabilities) from these specialized models are then combined using a meta-learner (e.g., a logistic regression model) to make the final prediction [18].

- Advantages: More flexible and robust, as the failure of one model does not necessarily compromise the entire system. It allows for the use of modality-specific optimal architectures.

- Disadvantages: Cannot capture complex, non-linear interactions between low-level features across different data types.

Hybrid and Intermediate Fusion

This is often the most powerful approach, leveraging deep learning architectures designed to fuse data at intermediate layers.

- Methodology: Each data type is processed through a dedicated neural network branch (e.g., a CNN for images, an LSTM for temporal EHR data, a fully connected network for genomics). The embeddings or feature maps from these branches are then fused in a shared deep learning network, which learns a joint representation before the final prediction layer [18]. Transformer-based models and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are emerging as powerful architectures for this purpose, as they can model complex relationships within and between data types [18].

- Advantages: Capable of learning sophisticated interactions between modalities and is often more accurate than early or late fusion.

- Disadvantages: Computationally intensive and requires large amounts of data to train effectively without overfitting.

Experimental Protocols for Model Development

To ensure reproducible and clinically relevant results, a structured experimental protocol is essential. The following workflow outlines a robust methodology for developing a multimodal cancer prognosis model.

Protocol: Development of a Multimodal Prognostic Model

Objective: To develop and validate a deep learning model that integrates EHR, genomic, and imaging data to predict 5-year survival in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

1. Data Curation and Cohort Definition:

- Data Sources: Secure access to a retrospective cohort from multiple institutions (e.g., The Cancer Genome Atlas - TCGA for genomics/images, and partner hospital EHRs).

- Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria: Define cohort based on confirmed NSCLC diagnosis, availability of pretreatment CT scans, targeted sequencing data (e.g., for EGFR, KRAS, ALK), and complete baseline EHR data.

- Ethics and Privacy: Obtain IRB approval. De-identify all data. Anonymize DICOM headers.

2. Data Preprocessing Pipelines:

- EHR: Extract and clean structured data (stage, histology, smoking pack-years). Process clinical notes with a clinical BERT model to extract phenotypes like "cardiovascular disease."

- Genomics: Process VCF files from sequencing. Focus on a curated panel of 50 cancer-related genes. Encode variants as binary (present/absent) or ternary (0/1/2 for zygosity) features.

- Imaging: Identify the primary tumor on each CT scan. Employ a pre-trained nnU-Net or similar model for automatic tumor segmentation. Extract a standard set of 100 radiomic features (e.g., using PyRadiomics library) from the segmented volume, encompassing shape, intensity, and texture.

3. Model Training with Cross-Validation:

- Integration Strategy: Employ a hybrid fusion model. The architecture will consist of:

- A fully connected input branch for structured EHR and genomic data.

- A separate input branch for the radiomic features.

- A fusion layer that concatenates the embeddings from both branches.

- Several fully connected layers for the joint representation, ending in a sigmoid activation for binary classification (survival ≥5 years vs. <5 years).

- Training Regimen: Use a 5-fold stratified cross-validation on the training set to tune hyperparameters (learning rate, dropout). Use the Adam optimizer and binary cross-entropy loss. Implement early stopping to prevent overfitting.

4. Model Validation and Interpretation:

- Performance Metrics: Evaluate the final model on a held-out test set from a different institution to assess generalizability. Report AUC-ROC, accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

- Model Interpretability: Apply Explainable AI (XAI) techniques such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to determine the contribution of each feature (e.g., a specific mutation, a radiomic texture feature, smoking history) to the model's prediction [20]. This is critical for building clinical trust.

Diagram 2: Experimental protocol for multimodal model development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Success in developing ML models for oncology relies on a suite of computational tools and data resources. The following table details key "research reagents" essential for this field.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Oncology AI Research

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Relevance to Cancer Model Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programming & ML Frameworks | Python, R, PyTorch, TensorFlow, Scikit-learn | Core programming, model building, and data manipulation. | Foundation for implementing data preprocessing, custom model architectures (CNNs, Transformers), and training loops. |

| Genomic Data Analysis | GATK, ANNOVAR, DESeq2, STAR, BWA | Processing raw sequencing data, variant calling, and differential expression analysis. | Essential for converting raw FASTQ files into analyzable genomic features (mutations, expression values) for model input. |

| Medical Imaging Processing | ITK-SNAP, 3D Slicer, PyRadiomics, MONAI | Image segmentation, registration, and extraction of quantitative features (radiomics). | Used to delineate tumors on CT/MRI and compute feature sets that describe tumor phenotype for use in ML models. |

| Data & Model Management | DVC (Data Version Control), MLflow, TensorBoard | Versioning datasets, tracking experiments, and monitoring model training. | Critical for reproducibility, managing multiple data versions, and comparing the performance of hundreds of model experiments. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) | SHAP, LIME, Captum | Interpreting model predictions and understanding feature importance. | Crucial for clinical translation; helps answer why a model made a certain risk prediction, building trust with clinicians [20]. |

| Public Data Repositories | The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), UK Biobank, Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) | Sources of large-scale, multimodal, and often curated oncology datasets. | Provide the necessary volume and diversity of data (EHR, genomic, imaging) required for training and validating robust models [7] [20]. |

The effective leveraging of EHRs, genomics, and medical imaging is the cornerstone of modern machine learning applications in oncology. The journey from raw, heterogeneous data sources to a validated predictive model is complex, requiring meticulous preprocessing, thoughtful integration strategies, and rigorous experimental validation. While challenges such as data privacy, heterogeneity, and model interpretability remain significant, the systematic approach outlined in this guide provides a roadmap for researchers. The future of the field lies in the development of more sophisticated and transparent fusion architectures, the curation of larger, more diverse multimodal datasets, and the steadfast focus on clinical utility. By mastering this complex data landscape, researchers and drug development professionals can unlock the full potential of AI to drive breakthroughs in cancer risk prediction and precision prognosis.

From Algorithms to Action: Methodologies and Clinical Applications in Precision Oncology

The application of machine learning in oncology represents a paradigm shift from reactive treatment to proactive risk assessment and personalized intervention. Within this domain, a fundamental tension exists between traditional statistical models and modern ensemble algorithms regarding which approach offers superior predictive performance. Traditional models like Logistic Regression (LR) and Support Vector Machines (SVM) have established a strong foundation due to their interpretability and well-understood statistical properties. In contrast, ensemble methods such as Random Forest (RF), eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), and Categorical Boosting (CatBoost) offer sophisticated capabilities for capturing complex, non-linear relationships in high-dimensional data. This technical analysis examines the comparative performance of these algorithmic paradigms within the critical context of cancer risk prediction and prognosis, providing researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based guidance for model selection.

Theoretical Foundations: Algorithmic Mechanisms and Strengths

Traditional Models: Established Workhorses

Logistic Regression (LR): As a generalized linear model, LR predicts the probability of a binary outcome by fitting data to a logistic function. Its strengths lie in computational efficiency, high interpretability through coefficient analysis, and robust statistical foundations. However, it assumes a linear relationship between predictor variables and the log-odds of the outcome, limiting its capacity to capture complex interactions without manual feature engineering [22].

Support Vector Machines (SVM): SVM constructs an optimal hyperplane to separate classes in a high-dimensional feature space, employing kernel functions to handle non-linear decision boundaries. The algorithm excels in high-dimensional spaces and is effective where the number of dimensions exceeds sample size. Its performance is heavily dependent on appropriate kernel selection and regularization parameters, with the Radial Basis Function (RBF) kernel often preferred for cancer genomic classification tasks [23].

Ensemble Methods: Advanced Pattern Recognition

Random Forest (RF): An ensemble method based on bagging (bootstrap aggregating), RF constructs multiple decision trees during training and outputs the mode of their predictions for classification. This approach reduces variance and mitigates overfitting through inherent randomization, making it particularly robust for noisy biomedical data. RF provides native feature importance metrics but offers limited interpretability beyond these aggregate measures [20].

XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting): This boosting algorithm builds sequential decision trees where each tree corrects errors of its predecessor, optimizing a differentiable loss function through gradient descent. XGBoost incorporates regularization techniques to control model complexity, making it highly resistant to overfitting while delivering state-of-the-art results across diverse domains [24].

CatBoost: A recent advancement in gradient boosting, CatBoost specializes in efficiently handling categorical features through ordered boosting and permutation-driven encoding. This approach prevents target leakage and training shift, addressing common pitfalls in heterogeneous medical data that mixes continuous clinical measurements with categorical diagnostic codes [25].

Performance Benchmarking: Quantitative Evidence from Cancer Research

Predictive Accuracy Across Cancer Domains

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of Algorithms Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Algorithm | Accuracy (%) | AUC-ROC | F1-Score | Study Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer | Neural Networks | 97.0 | - | 0.98 | Treatment Prediction [26] |

| Breast Cancer | IQI-BGWO-SVM | 99.25 | - | - | Disease Diagnosis [27] |

| Multiple Cancers | CatBoost | 98.75 | - | 0.9820 | Risk Prediction [25] [7] |

| Thyroid Cancer | CatBoost | 97.0 | 0.99 | - | Recurrence Prediction [28] |

| Head & Neck Cancer | XGBoost | - | 0.890 | - | Radiation Dermatitis [24] |

| Noncardia Gastric Cancer | Logistic Regression | 73.2 | - | - | Risk Prediction [22] |

| Secondary Cancer | Decision Tree | - | 0.72 | 0.38 | Risk Prediction [29] |

Table 2: Relative Algorithm Performance in Cancer Prediction Tasks

| Algorithm | Interpretability | Handling of Non-Linear Relationships | Processing of Categorical Features | Robustness to Missing Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logistic Regression | High | Limited (requires feature engineering) | Requires encoding | Moderate (with imputation) |

| SVM | Moderate (linear kernel) to Low (non-linear kernels) | High (with appropriate kernel) | Requires encoding | Low |

| Random Forest | Moderate (feature importance available) | High | Native handling | High |

| XGBoost | Moderate (feature importance available) | High | Requires encoding | Moderate |

| CatBoost | Moderate (feature importance available) | High | Native handling with advanced encoding | High |