Machine Learning Accelerated Pharmacophore Virtual Screening: Revolutionizing Early Drug Discovery

This article explores the transformative integration of machine learning (ML) with pharmacophore-based virtual screening (VS) to overcome critical bottlenecks in early drug discovery.

Machine Learning Accelerated Pharmacophore Virtual Screening: Revolutionizing Early Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article explores the transformative integration of machine learning (ML) with pharmacophore-based virtual screening (VS) to overcome critical bottlenecks in early drug discovery. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive examination of how ML models are being used to drastically accelerate screening speeds, improve hit identification from ultra-large chemical libraries, and enable scaffold hopping. The scope covers foundational concepts, modern methodological advances including deep learning and ensemble models, practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing predictive performance, and rigorous validation approaches comparing ML-powered workflows to traditional techniques. By synthesizing current research and real-world applications, this article serves as a guide for implementing these cutting-edge, data-driven approaches to make the drug discovery pipeline more efficient and cost-effective.

The Foundation: Understanding Pharmacophore Screening and Its AI-Driven Evolution

Technical Troubleshooting Guide: Common Pharmacophore Modeling Issues

Q1: My pharmacophore model retrieves too many false positives during virtual screening. How can I improve its specificity?

A: A high rate of false positives often indicates that the pharmacophore model lacks the steric and electronic constraints necessary to distinguish true actives from inactive compounds [1]. To address this:

- Add Exclusion Volumes: Incorporate exclusion volumes (XVols) into your model. These volumes represent regions in space occupied by the target protein itself, preventing the mapping of compounds that would cause steric clashes [1]. This mimics the shape of the binding pocket and is a critical step for structure-based models.

- Refine Feature Definitions: Review the chemical features in your hypothesis. Ensure that hydrogen bond donor and acceptor features are correctly defined as vectors, not just points, to enforce directional constraints [1]. You may also adjust the tolerance (radius) of each feature sphere to make it more or less restrictive.

- Validate with Inactive Compounds: Use a validation set containing known inactive molecules and decoys. A quality pharmacophore model should be able to exclude these inactive compounds while recovering known actives. Metrics like the Enrichment Factor (EF) and the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) plot can quantitatively assess this performance [1] [2].

Q2: My ligand-based pharmacophore model fails to identify active compounds with novel scaffolds. What is the likely cause?

A: This is typically a problem of over-fitting to the training set's specific chemical structures rather than the underlying functional features [1].

- Increase Training Set Diversity: The training set of active molecules should be structurally diverse. If all training molecules share a common core scaffold, the resulting model will be biased towards that specific chemistry and unable to perform "scaffold hopping" [1].

- Re-evaluate Feature Selection: The model may contain too many mandatory features. Try designating some features as "optional" or allowing the model to omit one feature during screening. This makes the model more flexible and able to recognize molecules that possess most, but not all, of the essential interaction points [1].

- Switch to a Structure-Based Approach: If possible, develop a structure-based pharmacophore model. This approach derives features directly from the target's binding site and is inherently scaffold-agnostic, making it highly effective for identifying novel chemotypes [3] [2].

Q3: How can I account for protein and ligand flexibility in my structure-based pharmacophore model?

A: Traditional models from a single static crystal structure may miss alternative interaction patterns. To incorporate flexibility:

- Use Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Run MD simulations of the protein-ligand complex. You can then generate a pharmacophore model from each snapshot of the trajectory. This produces an ensemble of models that capture the dynamic interaction landscape [4].

- Employ a Consensus or Hierarchical Approach: Instead of picking one "best" model, use multiple models from the MD simulation in a consensus screening method, such as the Common Hits Approach (CHA) [4]. Alternatively, represent all models in a single Hierarchical Graph Representation of Pharmacophore Models (HGPM), which provides an intuitive visualization of feature relationships and frequencies, allowing for informed model selection [4].

- Leverage Machine Learning: Recent methods use machine learning to learn the essential interaction patterns from docking scores or MD data, creating models that implicitly incorporate flexibility and can accelerate screening by several orders of magnitude [5].

Machine Learning-Accelerated Pharmacophore Virtual Screening: Key Protocols

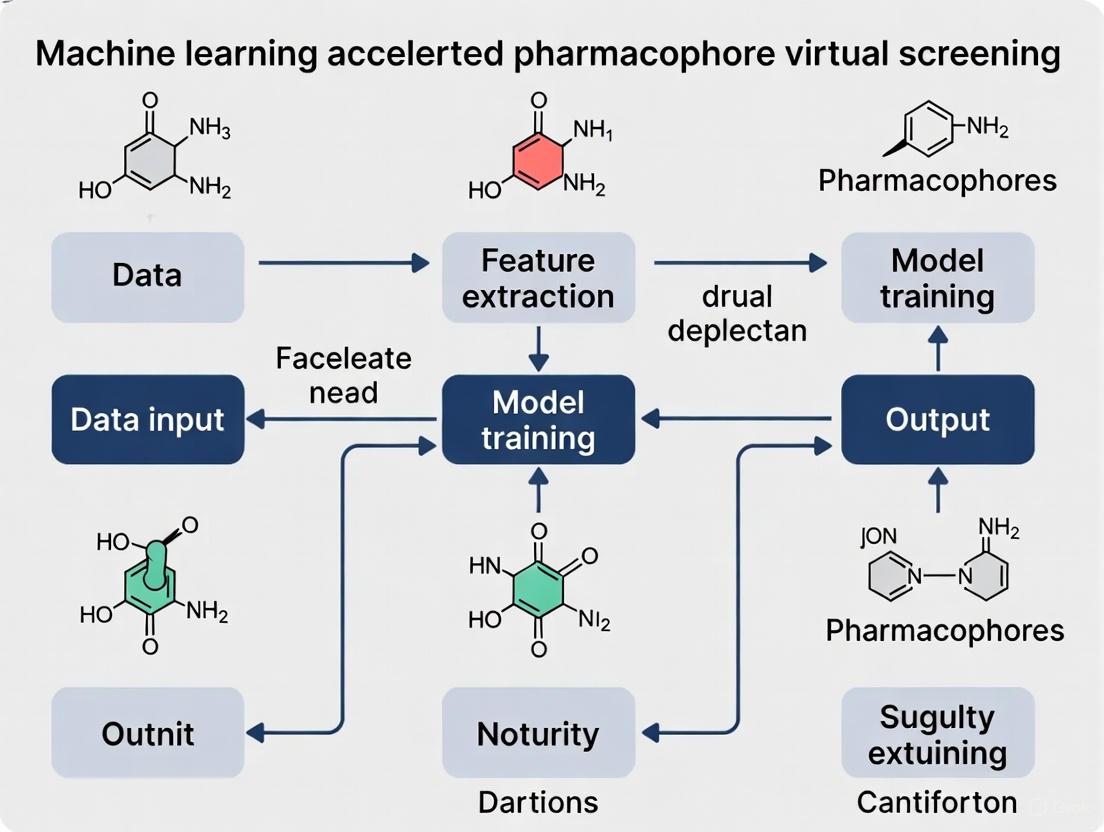

The integration of machine learning (ML) with pharmacophore modeling has created powerful new methodologies for ultra-rapid virtual screening. The core workflow and its acceleration via ML are summarized in the diagram below.

Protocol 1: Developing an ML Model to Predict Docking Scores

This protocol uses ML to bypass computationally expensive molecular docking, enabling the screening of ultra-large libraries [5].

- Data Preparation: Select a diverse set of ligands with known activity against your target (e.g., from ChEMBL). Generate their low-energy 3D conformations.

- Docking Score Calculation: Dock the prepared ligand set into your target's binding site using your preferred docking software (e.g., Smina) to obtain a docking score for each molecule. This score serves as the training label.

- Feature Extraction (Fingerprinting): Encode the structural and pharmacophoric characteristics of each ligand using molecular fingerprints. This can include:

- Classical Fingerprints: Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP).

- Pharmacophore Fingerprints: Ligand-based pharmacophore fingerprints that represent the spatial arrangement of chemical features [6].

- Model Training and Validation: Train an ensemble ML model (e.g., combining Random Forest and Support Vector Machines) to predict the docking score from the molecular fingerprints. Validate the model using a hold-out test set and scaffold-based splits to ensure its predictive power generalizes to new chemotypes [5].

- Virtual Screening: Apply the trained model to predict docking scores for millions of compounds in a database (e.g., ZINC). This ML-based screening can be ~1000 times faster than classical docking, allowing for the rapid prioritization of top-scoring compounds for synthetic acquisition and experimental testing [5].

Protocol 2: Pharmacophore-Guided Deep Learning for Molecular Generation

This protocol inverts the screening process by using a pharmacophore to generate novel, active molecules from scratch (de novo design) [7].

- Pharmacophore Hypothesis Input: Define a 3D pharmacophore hypothesis, either from a known active ligand or a protein structure. Represent this hypothesis as a complete graph where nodes are pharmacophore features and edges are inter-feature distances.

- Model Architecture: Employ a deep learning model such as PGMG (Pharmacophore-Guided Molecule Generation). This model typically uses:

- A Graph Neural Network (GNN) encoder to process the spatial distribution of pharmacophore features.

- A transformer decoder to generate SMILES strings of novel molecules.

- A latent variable to model the many-to-many relationship between pharmacophores and molecules, ensuring output diversity [7].

- Generation and Evaluation: The model generates molecules that match the input pharmacophore. Evaluate the generated molecules not only on their fit to the pharmacophore but also on key drug-like properties (validity, uniqueness, novelty) and predicted binding affinity through docking [7].

Performance Metrics & Benchmarking Data

The following tables summarize quantitative data relevant to evaluating and benchmarking pharmacophore and ML-based screening methods.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Virtual Screening Methods

| Method | Key Metric | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical Pharmacophore VS | Hit Rate (vs. random) | 5-40% (vs. typically <1%) | [1] |

| ML-Accelerated Docking Score Prediction | Speed Increase vs. Classical Docking | ~1000x faster | [5] |

| Pharmacophore-Guided Deep Learning (PGMG) | Novelty / Uniqueness of Generated Molecules | High (>80% novelty achieved) | [7] |

| Structure-Based Pharmacophore Validation | AUC / Enrichment Factor (EF1%) | AUC: 0.98; EF1%: 10.0 | [2] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Accelerated Pharmacophore Research

| Reagent / Resource | Function in Research | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Databases | Source of active/inactive ligands and decoys for model training and validation. | ChEMBL, ZINC, DrugBank, DUD-E [5] [1] |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Source of 3D macromolecular structures for structure-based pharmacophore modeling. | RCSB PDB [4] [2] |

| Molecular Docking Software | Generates binding poses and scores for training ML models or validating hits. | Smina, AutoDock Vina [5] [2] |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Creates 2D/3D pharmacophore hypotheses from structures or ligands. | LigandScout, Discovery Studio [4] [2] |

| MD Simulation Software | Samples protein-ligand dynamics to create ensembles of pharmacophore models. | AMBER, GROMACS [4] |

| Fingerprinting & ML Libraries | Generates molecular descriptors and builds predictive ML models. | RDKit, Scikit-learn [5] [6] |

FAQs on Core Concepts and Advanced Applications

Q1: What is the precise IUPAC definition of a pharmacophore?

A: According to IUPAC, a pharmacophore is "an ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [8] [9] [1]. It is crucial to understand that a pharmacophore is an abstract model of interactions, not a specific molecular scaffold or functional group.

Q2: What are the fundamental feature types used in building a 3D pharmacophore model?

A: The core features include [8] [1] [3]:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA)

- Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD)

- Hydrophobic (H) / Aromatic (AR)

- Positive / Negative Ionizable (PI/NI) These features are represented as 3D objects (points, vectors, spheres) in space to define the necessary interactions for biological activity.

Q3: How does the structure-based pharmacophore approach differ from the ligand-based approach?

A:

- Structure-Based: Directly extracts pharmacophore features from a 3D protein-ligand complex (from PDB or docking). It benefits from knowing the exact interactions and allows the inclusion of exclusion volumes [3] [2].

- Ligand-Based: Derives common pharmacophore features by aligning the 3D structures of multiple known active molecules. It is used when the 3D structure of the target is unknown but a set of active ligands is available [1] [3]. The diagram below illustrates these two primary approaches and their integration with modern ML techniques.

Q4: What are the emerging applications of pharmacophore modeling beyond simple virtual screening?

A: The pharmacophore concept is now applied in advanced areas such as [9] [10]:

- ADMET and Toxicity Prediction: Modeling properties related to absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (e.g., blood-brain barrier permeation) [6].

- Off-Target and Side Effect Prediction: Identifying unintended interactions with other biological targets to anticipate potential adverse effects.

- Target Identification (Polypharmacology): For a compound with unknown mechanism, a pharmacophore model can be used to screen against a panel of targets to identify potential primary and secondary targets.

- De Novo Molecular Generation: As detailed in Protocol 2, pharmacophores guide AI to generate novel, active molecules from scratch [7].

Contrasting Structure-Based vs. Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling Approaches

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is a pharmacophore? A pharmacophore is defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [3] [11] [12]. It is an abstract model of the essential functional features a molecule must possess to bind to a specific target.

What are the key pharmacophoric features? The most common chemical features used in pharmacophore models are [3] [13]:

- Hydrogen Bond Acceptor (HBA)

- Hydrogen Bond Donor (HBD)

- Hydrophobic (H)

- Positively / Negatively Ionizable (PI / NI)

- Aromatic (AR)

- Exclusion Volumes (XVOL) - Represent regions sterically forbidden by the receptor.

Comparative Analysis: Structure-Based vs. Ligand-Based Approaches

Table 1: Core differences between structure-based and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling.

| Aspect | Structure-Based Pharmacophore | Ligand-Based Pharmacophore |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data Input | 3D structure of the target protein or protein-ligand complex [3] | A set of known active ligands [14] |

| Key Prerequisite | Known 3D structure of the target (from PDB, homology modeling, or AlphaFold2) [3] | A collection of active compounds, ideally with diverse structures and known activities [11] |

| Fundamental Principle | Identifies key interaction points (features) directly from the binding site of the macromolecular target [3] [12] | Derives common chemical features from a set of superimposed active ligands [3] [14] |

| Typical Workflow | 1. Protein Preparation2. Binding Site Identification3. Interaction Points Mapping4. Feature Selection & Model Generation [3] | 1. Ligand Preparation & Conformational Analysis2. Molecular Alignment3. Common Feature Perception4. Hypothesis Generation [11] [14] |

| Ideal Use Case | Target with a known (or reliably modeled) 3D structure [3] | Target with unknown structure but multiple known active ligands [3] [15] |

| Advantages | Can identify novel interaction features not present in known ligands; does not require a set of pre-identified active compounds [3] | Does not require the 3D structure of the target; model is based on experimentally validated active compounds [15] |

| Challenges & Limitations | Quality of the model is highly dependent on the quality and resolution of the protein structure [3] | Handling ligand conformational flexibility and achieving a correct alignment are critical and non-trivial tasks [11] |

Workflow Visualization

Workflow for pharmacophore modeling.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: When should I choose a structure-based approach over a ligand-based one? Answer: The choice is primarily dictated by data availability.

- Use Structure-Based if: The 3D structure of your target is available from the PDB, or can be reliably generated through homology modeling or tools like AlphaFold2 [3]. This approach is powerful for discovering novel scaffolds (scaffold hopping) as it is not biased by existing ligand structures.

- Use Ligand-Based if: The target's structure is unknown, but you have a set of known active ligands (a training set). This is common for many membrane proteins like GPCRs [11] [15]. The quality of the model increases with the number, diversity, and potency of the known actives.

FAQ 2: My ligand-based pharmacophore model fails to distinguish active compounds from inactives during validation. What could be wrong? Troubleshooting Guide:

- Issue: Poor training set. The set of active ligands used to build the model might be too structurally diverse (preventing identification of a common pattern) or too congeneric (leading to an overly specific model) [11].

- Solution: Re-curate your training set. Include ligands with a range of potencies and ensure they are known to act via the same mechanism. Using a set that includes confirmed inactive compounds can also help refine the model by defining exclusion volumes [16].

- Issue: Incorrect ligand alignment. The model is highly sensitive to the spatial alignment of the input ligands [14].

- Solution: If automatic alignment fails, consider using a known bioactive conformation (e.g., from a crystal structure) as a template for manual or constrained alignment [16].

- Issue: Suboptimal feature selection. The model may have too many or too few features.

- Solution: Manually adjust the feature constraints in your software (e.g., in Schrödinger's Phase, you can set the minimum and maximum number of features and specify required features) [16]. Validate multiple hypotheses against a test set with known actives and decoys.

FAQ 3: How can I improve the accuracy of my structure-based pharmacophore model? Troubleshooting Guide:

- Issue: Low-quality protein structure. The model is only as good as the input structure [3].

- Solution: Carefully prepare the protein structure. Add missing hydrogen atoms, assign correct protonation states to residues (especially in the binding site), and correct any structural anomalies. If using a crystal structure, check its resolution.

- Issue: Incorrect or incomplete binding site definition.

- Solution: Use multiple tools (e.g., GRID, SiteMap) to characterize the binding pocket and confirm its relevance through literature or mutational data [3]. If a co-crystallized ligand is present, it provides a crucial reference for defining key interactions.

- Issue: Model is too rigid. A single, static structure may not represent the dynamic nature of binding.

- Solution: Incorporate protein flexibility. Generate pharmacophore models from multiple molecular dynamics (MD) simulation snapshots to create a dynamic pharmacophore or an ensemble of models [13].

FAQ 4: How is Machine Learning (ML) integrated with pharmacophore modeling to accelerate virtual screening? Answer: ML enhances pharmacophore-based virtual screening in several key ways [17]:

- Feature Learning and Selection: ML algorithms, particularly deep learning, can automatically learn complex, non-intuitive pharmacophoric patterns and molecular descriptors from large datasets of active and inactive compounds, reducing reliance on manual feature engineering [17].

- Improved Performance: ML models can be trained to predict the pharmacophore-matching score or the biological activity of a compound directly from its structure (e.g., from SMILES strings or molecular graphs), leading to faster and more accurate screening [17].

- Handling Molecular Flexibility: Techniques like pharmacophore fingerprints, which encode the presence or absence of pharmacophore features, can be used as input for ML models to efficiently screen vast chemical libraries while implicitly accounting for conformational diversity [18] [13].

Essential Research Reagents & Computational Tools

Table 2: Key software and resources for pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening.

| Tool / Resource Name | Type / Category | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Data Repository | Source for experimental 3D structures of proteins and protein-ligand complexes, the essential input for structure-based modeling [3] |

| LigandScout | Software | Platform for both structure-based (from PDB complexes) and ligand-based pharmacophore modeling, visualization, and virtual screening [18] [12] |

| Schrödinger Phase | Software | Comprehensive tool for developing ligand-based pharmacophore hypotheses, creating screening databases, and performing virtual screening [16] |

| ELIXIR-A | Software (Open-Source) | Python-based tool for refining and comparing multiple pharmacophore models, useful for analyzing results from MD simulations or multiple ligands [18] |

| Pharmit | Online Platform | Interactive tool for pharmacophore-based virtual screening of large compound databases like ZINC and PubChem [18] |

| Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD-e) | Benchmark Dataset | A curated database containing active compounds and "decoys" (structurally similar but physiochemically distinct inactive molecules) for objective validation of virtual screening methods [18] [16] |

| RDKit | Open-Source Toolkit | A collection of cheminformatics and machine learning tools useful for ligand preparation, conformational analysis, and basic pharmacophore feature handling [12] |

Experimental Protocol: Developing a Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Model using Schrödinger Phase

This protocol outlines the key steps for generating a pharmacophore hypothesis from a set of active ligands, as detailed in the Schrödinger tutorial [16].

1. Project Setup and Ligand Preparation

- Create a new project in Maestro and set the working directory.

- Import your prepared 3D ligand structures into the project. Ensure ligands have been pre-processed (e.g., using LigPrep) with correct ionization states, tautomers, and stereochemistry.

2. Defining Actives and Inactives

- In the

Develop Pharmacophore Hypothesespanel, selectMultiple ligands (selected entries). - Click

Defineto specify the active and inactive ligands from your set. This requires a property column (e.g.,pIC50).- Example Thresholding: Set active ligands as those with

pIC50 >= 7.3(equivalent to IC50 ≤ 50 nM) and inactives as those withpIC50 <= 5.0(IC50 ≥ 10 µM) [16].

- Example Thresholding: Set active ligands as those with

3. Configuring Hypothesis Generation Settings

- In the

Featurestab ofHypothesis Settings:- Set the range for the

Number of features in the hypothesis(e.g., 5 to 6). - Optionally, specify a

Preferred minimum number of features. - You can set constraints for specific features (e.g., minimum 1 Donor (D) and 1 Negative (N)).

- Use

Feature presetslike "Make acceptor and negative equivalent" if chemically justified.

- Set the range for the

- In the

Excluded Volumestab:- Check

Create excluded volume shell. - Generate the shell from both

ActivesandInactivesto define regions sterically forbidden by the receptor, improving model selectivity [16].

- Check

4. Running the Job and Analyzing Results

- Provide a

Job name(e.g.,my_pharmacophore) and clickRun. - Upon completion, analyze the generated hypotheses in the

Project Table. Hypotheses are automatically named based on their features (e.g.,DHNRRR). - Critical Validation Steps:

- Visually inspect how well active ligands align with the hypothesis features and avoid the excluded volumes.

- Check how inactive ligands fail to match the hypothesis, either through poor feature alignment or steric clashes with excluded volumes.

- The best hypothesis is typically the one with the highest survival score that also convincingly separates known actives from inactives.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why does my virtual screening workflow, which works well on small test sets, fail to scale effectively to ultra-large libraries?

The primary failure in scaling is the computational cost and time required by traditional methods. Classical molecular docking procedures become infeasible for screening billions of molecules [5]. Furthermore, the high steric tolerance and physical implausibility of poses generated by some deep learning methods can lead to false positives when applied to novel chemical spaces [19].

- Recommended Protocol for Scaling: Implement a hierarchical filtering approach. Begin with fast ligand-based methods like pharmacophore screening or 2D similarity searches if known active compounds exist [20]. Follow this with machine learning models trained to predict docking scores, which can accelerate screening by up to 1000 times compared to classical docking [5]. Reserve rigorous molecular docking for the final, greatly reduced subset of compounds.

FAQ 2: My QSAR model has high statistical accuracy, but its predictions for novel chemotypes are unreliable. What is the cause?

This is a classic problem of a model operating outside its Applicability Domain (AD). Traditional QSAR models suffer from the lack of a formal confidence score for each prediction, and their reliability is confined to the chemical space represented in their training data [21]. When presented with a novel scaffold (a new chemotype), the model's predictions cannot be trusted.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Assess Applicability Domain: Use tools to determine if your query molecules fall within the chemical space of the training set. A model cannot be expected to reliably extrapolate.

- Implement Conformal Prediction: Adopt newer QSAR approaches like Conformal Prediction (CP), which provides a confidence measure for each prediction and clearly identifies unreliable ones [21].

- Use Consensus Modeling: Combine predictions from multiple QSAR models built with different algorithms and descriptors. Consensus strategies have been proven to be more accurate and cover a wider area of chemical space than individual models on average [22].

FAQ 3: Why does a compound with an excellent docking score show no biological activity in the lab?

A high docking score does not equate to high binding affinity. Scoring functions are designed to identify plausible binding poses but are notoriously poor at predicting absolute binding affinity [23]. They often oversimplify critical physical phenomena.

- Key Limitations to Investigate:

- Inadequate Treatment of Solvation: Scoring functions struggle to model complex water networks and desolvation penalties accurately.

- Protein Rigidity: Most docking programs treat the protein as rigid, ignoring the induced fit and conformational changes that occur upon ligand binding [23].

- Ignoration of Entropy: The crucial role of conformational entropy and dynamics in binding is often not fully captured [23].

- Non-drug-like Properties: The compound might have poor pharmacokinetic properties, metabolic liability, or be synthetically inaccessible, issues docking does not assess [23].

FAQ 4: How can I improve the physical plausibility of the binding poses generated by deep learning docking tools?

While some DL docking methods, particularly generative diffusion models, achieve high pose accuracy, they can produce poses with steric clashes and incorrect bond geometries [19].

- Solution: Integrate post-docking refinement and validation. Use tools like the PoseBusters toolkit to systematically check generated poses for chemical and geometric consistency, including bond lengths, angles, and protein-ligand clashes [19]. Subsequently, refine top-scoring poses using more rigorous molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and rescore them with methods like MM-GBSA/MM-PBSA [23].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Hit Rate and Poor Enrichment in Virtual Screening

Problem: Your VS campaign returns a high number of false positives, failing to enrich for truly active compounds.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Library Preparation | Check for correct protonation states, tautomers, and stereochemistry. Verify the generation of bioactive conformers. | Use software like LigPrep [20], OMEGA [20], or RDKit's MolVS [20] for standardized, high-quality 3D compound preparation. |

| Over-reliance on a Single Protein Conformation | Check if your protein structure has known flexible loops or multiple crystallographic structures with different binding site conformations. | Perform ensemble docking using multiple protein structures. Generate these from different crystal structures or by clustering frames from Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations [23]. |

| Limitations of the Scoring Function | Test if your docking program can correctly re-dock and score known active ligands from co-crystal structures. | Use a consensus scoring approach. Combine results from multiple docking programs or different scoring functions to prioritize compounds identified by several methods [22]. |

| Ignoring Pharmacophore Constraints | Check if your top-scoring docking poses actually form key interactions known to be critical for activity (e.g., from SAR studies). | Develop a structure-based pharmacophore model from a protein-ligand complex and use it to filter docking results, ensuring poses match essential interaction features [3] [24]. |

Issue: QSAR Model with High Training Accuracy but Poor Predictive Performance

Problem: Your QSAR model performs well on its training and internal test sets but fails when applied to new external data.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Overfitting | Check if the model performance on the training set is significantly higher than on a rigorous external test set. | Simplify the model by reducing the number of descriptors. Use validation techniques like scaffold splitting (splitting data based on Bemis-Murcko scaffolds) to ensure the model is tested on new chemotypes [5]. |

| Narrow Applicability Domain | Analyze the chemical space of your external dataset compared to the training set using PCA or similarity metrics. | Use conformal prediction frameworks to assign a confidence level to each prediction, allowing you to flag and disregard predictions for molecules outside the model's domain [21]. |

| Data Inconsistency and Bias | Evaluate the source and quality of your training data. Check for activity cliffs and significant imbalances between active and inactive compounds. | Curate a high-quality, diverse dataset. For imbalanced data, use techniques like class weighting during model training [21]. Apply consensus modeling to integrate predictions from multiple models, improving robustness [22]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Building a Robust QSAR Model with an Defined Applicability Domain

This protocol is designed to create a generalizable QSAR model and quantify the confidence of its predictions.

- Data Curation and Preparation: Extract bioactivity data (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki) from curated databases like ChEMBL [21] [5]. Standardize structures, remove duplicates, and calculate molecular descriptors or fingerprints (e.g., Morgan fingerprints using RDKit) [21].

- Strategic Data Splitting: Instead of a simple random split, divide the dataset using Bemis-Murcko scaffolds. This ensures that the model is tested on structurally distinct scaffolds not seen during training, providing a more realistic assessment of its predictive power for novel chemotypes [5].

- Model Training and Validation: Train a machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest, Support Vector Machine) on the training set. Validate its performance on the scaffold-based test set.

- Define Applicability Domain with Conformal Prediction: Implement a conformal predictor using a calibration set. This will output predictions with a confidence measure (e.g., at 95% confidence), allowing you to identify and withhold predictions for molecules that are too dissimilar from the training data [21].

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Accelerated Docking Score Prediction

This protocol bypasses slow molecular docking by using ML models to predict docking scores directly from 2D structures, enabling ultra-large library screening [5].

- Generate Training Data: Perform molecular docking with your chosen software (e.g., Smina) on a diverse but manageable set of ligands (e.g., 10,000-50,000 compounds) to obtain docking scores [5].

- Train an Ensemble ML Model: Use the docked ligands and their scores as training data. Represent each molecule with multiple types of molecular fingerprints and descriptors. Train an ensemble of machine learning models (e.g., using different algorithms or features) to predict the docking score. This ensemble reduces prediction errors [5].

- High-Throughput Screening: Apply the trained ensemble model to predict docking scores for millions or even billions of compounds in the virtual library. This process is orders of magnitude faster than classical docking.

- Validation and Docking: Select the top-ranked compounds from the ML screen and run a full molecular docking calculation for final verification and pose generation.

Troubleshooting Workflow for VS Bottlenecks

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| ZINC Database | A publicly available library of over 20 million commercially available compounds for virtual screening. Provides a vast chemical space for discovering high-quality hits [25]. | Compounds are purchasable but not available in-house. Vendor IDs are provided for purchasing hits [25]. |

| ChEMBL Database | A curated public database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. Used to extract bioactivity data (pChEMBL values) for training QSAR and machine learning models [21] [5]. | Data requires careful curation and standardization. Activity data can be sparse for certain targets [21]. |

| RDKit | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit. Used for calculating molecular descriptors, generating conformers (via its ETKDG method), and standardizing chemical structures [21] [20]. | The freely available DG algorithm is robust but may be outperformed by some commercial systematic conformer generators [20]. |

| PoseBusters | A validation toolkit to check the physical plausibility of AI-generated docking poses against chemical and geometric criteria (bond lengths, clashes, etc.) [19]. | Critical for identifying false positives from deep learning docking methods that may have good RMSD but invalid physics [19]. |

| OMEGA & ConfGen | Commercial, high-performance conformer generation software. Systematically sample conformational space to produce low-energy, biologically relevant 3D structures for docking and pharmacophore modeling [20]. | Outperforms simpler methods in benchmarking studies and is crucial for ensuring the bioactive conformation is represented [20]. |

| AutoDock Vina & Glide | Widely used molecular docking programs (Vina is open-source, Glide is commercial). Used for binding pose prediction and structure-based virtual screening [19]. | Traditional methods like Glide SP show high physical validity and robustness, especially on novel protein pockets [19]. |

ML-Accelerated Virtual Screening Protocol

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

Q1: My ML model for predicting docking scores performs well on the training data but poorly on new, unseen chemotypes. How can I improve its generalization?

- Answer: This is a classic sign of overfitting, where the model learns the training data too well but fails to generalize. To address this:

- Implement Scaffold-Based Data Splitting: Instead of random splits, divide your dataset so that training and testing sets contain different molecular scaffolds (core structures). This ensures the model is tested on genuinely novel chemotypes and better simulates a real virtual screening scenario [5].

- Utilize Ensemble Models: Combine predictions from multiple models trained on different types of molecular fingerprints or descriptors (e.g., ECFP, molecular weight, topological descriptors). This approach reduces variance and overall prediction error, leading to more robust performance on diverse compounds [5].

Q2: Molecular docking is a bottleneck in my large-scale virtual screening workflow. Are there faster, structure-based alternatives?

- Answer: Yes, deep learning-based pharmacophore modeling offers a high-speed alternative.

- Solution: Tools like PharmacoNet provide fully automated, protein-based pharmacophore modeling. Instead of computationally intensive docking, these methods use a parameterized analytical scoring function to evaluate ligand potency based on pharmacophore feature alignment. This approach can screen hundreds of millions of compounds in a matter of hours on standard hardware, drastically accelerating the initial screening phase [26] [27].

- Troubleshooting Tip: If the hit rates from the initial pharmacophore screen are still too high for subsequent docking, you can apply a second filter using an ML model that predicts docking scores to further prioritize compounds [5].

Q3: How can I ensure the hits identified by my ML-driven virtual screening are not just artifacts but have real potential?

- Answer: Enhance the interpretability of your models and incorporate multiple validation strategies.

- Apply SHAP Analysis: Use SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis to interpret your ML model's predictions. This helps identify which specific molecular features or fingerprints are driving the activity prediction, adding a layer of plausibility and expert validation to the results [28].

- Conformational Ensembles: Train your ML models on docking results generated from multiple protein conformations, not just a single crystal structure. This accounts for protein flexibility and can improve the correlation between predicted and experimental activity [5].

- Experimental Triangulation: Always complement computational hits with in vitro testing. A successful workflow should synthesize and biologically evaluate top-ranked compounds to confirm inhibitory activity, as demonstrated in the MAO inhibitor study where 24 selected compounds were tested, leading to the discovery of active inhibitors [5].

Experimental Protocols for ML-Accelerated Pharmacophore Screening

The following protocol summarizes a methodology for machine learning-accelerated, pharmacophore-based virtual screening, as applied to Monoamine Oxidase (MAO) inhibitors [5].

1. Protein and Ligand Preparation

- Protein Structures: Obtain 3D coordinates of the target protein from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). For example, use PDB IDs 2Z5Y (for MAO-A) and 2V5Z (for MAO-B). Prepare the structure by removing native ligands and water molecules, and adding necessary hydrogen atoms [5].

- Ligand Library: Curate a library for screening, such as the ZINC database. Filter compounds based on drug-likeness rules (e.g., molecular weight < 700 Da) and remove highly flexible structures to simplify subsequent docking and modeling steps [5] [28].

2. Generating Training Data via Molecular Docking

- Docking Software: Perform molecular docking on a known set of active and inactive compounds using software like Smina to generate the ground-truth data [5].

- Output: The primary output is the docking score (DS) for each compound, which serves as the label for training the machine learning model.

3. Training the Machine Learning Model

- Feature Generation: Calculate multiple types of molecular representations for each compound, including:

- Molecular Fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4)

- Molecular Descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP, topological indices) [5]

- Model Training: Train an ensemble machine learning model (e.g., Random Forest) to predict the docking score based on the molecular features. The ensemble approach minimizes individual model errors [5] [28].

- Validation: Rigorously validate the model using a scaffold-based split to ensure its ability to generalize to new chemical classes [5].

4. Large-Scale Virtual Screening & Hit Identification

- Pharmacophore Constraint: Apply a pharmacophore model to filter the large screening library (e.g., ZINC), creating a constrained chemical space likely to bind the target [5].

- ML-Based Scoring: Use the trained ML model to rapidly predict docking scores for all compounds that pass the pharmacophore filter. This step is approximately 1000 times faster than running classical molecular docking on the entire library [5].

- Final Prioritization: Select the top-ranked compounds based on the predicted scores for synthesis and subsequent in vitro biological evaluation to confirm activity [5].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key computational tools and data resources essential for setting up an ML-accelerated virtual screening pipeline.

| Item Name | Function in the Experiment | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Smina [5] | Molecular docking software used to generate training data (docking scores) for the ML model. | Customizable scoring function; used for classic VS and creating labels for ML. |

| ZINC Database [5] | A publicly available library of commercially available compounds for virtual screening. | Source of millions to billions of purchasable molecules for screening. |

| Molecular Fingerprints (e.g., ECFP) [5] | 2D structural representations of molecules used as input features for the ML model. | Captures molecular patterns and features critical for activity prediction. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Defines essential steric and electronic features for molecular recognition, used as a constraint to filter libraries. | Can be traditional (e.g., in Schrodinger Maestro) or deep learning-based (e.g., PharmacoNet). |

| PharmacoNet [26] [27] | A deep learning framework for automated, structure-based pharmacophore modeling. | Enables ultra-fast screening; identifies key protein hotspots and pharmacophore features. |

| ChEMBL Database [5] | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. | Source of experimental bioactivity data (e.g., IC₅₀, Kᵢ) for known ligands. |

The table below consolidates key performance metrics from the reviewed studies, providing benchmarks for your own experiments.

| Metric | Reported Performance | Context / Model |

|---|---|---|

| Speed Gain | ~1000x faster than classical docking | ML-based docking score prediction vs. standard docking procedure [5]. |

| Screening Scale | 187 million compounds in < 21 hours | Performance of PharmacoNet on a single CPU for cannabinoid receptor inhibitors [26]. |

| Inhibition Activity | Up to 33% MAO-A inhibition | Best result from 24 synthesized and tested compounds identified via the ML/pharmacophore protocol [5]. |

| Model AUC | 0.99 | Interpretable Random Forest model for identifying GSK-3β inhibitors [28]. |

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the integrated machine learning and pharmacophore screening workflow.

ML Model Development Process

This diagram details the core process of creating the machine learning model that predicts docking scores.

An FAQ for Machine Learning-Accelerated Pharmacophore Virtual Screening

This guide addresses frequently asked questions and common troubleshooting scenarios for researchers applying Core ML concepts to pharmacophore-based virtual screening in drug discovery.

Core Concepts and Experimental Design

FAQ: What are the fundamental machine learning paradigms used in cheminformatics, and how are they applied to pharmacophore virtual screening?

Machine learning in cheminformatics is broadly categorized into three types, each with distinct applications in virtual screening [29] [30].

- Supervised Learning: Models are trained on labeled datasets where the correct output (e.g., "active" or "inactive" against a target) is known for each input molecule. These are extensively used for classification tasks (predicting categorical labels like bioactivity) and regression tasks (predicting continuous values like binding affinity) in quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and property prediction [29] [31] [30].

- Unsupervised Learning: Models find hidden patterns or intrinsic structures in unlabeled data. In virtual screening, this is crucial for clustering large chemical libraries to identify structural families or for dimensionality reduction to visualize and understand the chemical space of screened compounds [29] [30].

- Reinforcement Learning (RL): An agent learns optimal actions through trial-and-error interactions with an environment to maximize a cumulative reward. In drug discovery, RL is increasingly applied to de novo molecular design, where the agent learns to generate molecules with desired properties by sequentially building molecular structures [29] [32].

Table: Common Machine Learning Algorithms in Cheminformatics

| ML Paradigm | Algorithm Examples | Primary Use-Cases in Virtual Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN), Naïve Bayes (NB), Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) [29] | Bioactivity classification, binding affinity prediction (regression), ADMET property forecasting [29] [31] |

| Unsupervised Learning | k-Means Clustering, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [30] | Chemical library clustering, scaffold hopping, data exploration and visualization [29] |

| Reinforcement Learning | Deep Q-Networks (DQN), Policy Gradient Methods [29] | De novo drug design, optimizing multi-parameter objectives (potency, solubility, synthesizability) [29] [32] |

| Deep Learning (Subset of above) | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) [29] | Learning from complex data (e.g., molecular graphs, SMILES sequences), generating novel molecular structures [29] [33] |

FAQ: How do I choose the right machine learning algorithm for my virtual screening project?

Selecting an algorithm depends on your data and the specific question you are asking. The following workflow outlines a decision-making process for algorithm selection in a pharmacophore virtual screening context.

Troubleshooting Guide: My model's predictions are inaccurate and unreliable. What could be wrong?

Inaccurate models are often due to issues with input data or model configuration.

Problem: Poor Quality or Non-representative Training Data.

- Symptoms: Low accuracy on both training and test sets, model fails to generalize.

- Solution:

- Curate your data: For SMILES strings, use toolkits like RDKit to validate and standardize molecular structures. Remove duplicates and correct invalid representations [33].

- Address data bias: Ensure your negative dataset (inactives) is representative and not artificially easy to distinguish from actives.

- Apply feature scaling: Normalize or standardize numerical descriptors, especially for distance-based algorithms like SVM and kNN.

Problem: Data Leakage or Improper Validation.

- Symptoms: High accuracy during training/training but poor performance on truly external validation sets.

- Solution:

- Split data correctly: Strictly separate your data into training, validation, and test sets before any feature selection or model tuning [34].

- Use cross-validation: Apply k-fold cross-validation on the training set to get a more robust estimate of model performance and tune hyperparameters without touching the test set [34].

- Avoid target leakage: Ensure that no information from the validation/test set is used to inform the training process.

Problem: Suboptimal Algorithm or Hyperparameters.

- Symptoms: Model performance plateaus or is consistently worse than a simple baseline.

- Solution:

- Benchmark algorithms: Start by testing a few simple, interpretable models (e.g., Random Forest, SVM) as a baseline before moving to complex deep learning models [29].

- Perform hyperparameter tuning: Systematically search for the best hyperparameters (e.g., number of trees in RF, learning rate in neural networks) using methods like grid search or random search on the validation set.

Data Preparation and Feature Engineering

FAQ: How are molecular structures converted into a machine-readable format for model training?

Molecules are commonly represented as SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System) strings, a compact text-based notation that encodes the molecular structure [33]. Before training, these strings must be processed.

Table: Key Steps in SMILES Data Preprocessing

| Step | Description | Common Tools/Packages | Potential Issue if Skipped |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validation & Standardization | Check for and correct invalid SMILES; generate canonical forms to ensure one unique SMILES per molecule. | RDKit, OpenBabel | Model learns from incorrect or redundant structures, reducing generalizability. |

| Tokenization | Split the SMILES string into chemically meaningful units (e.g., atoms, bonds, branches). A regex-based tokenizer is preferred over character-level. | Custom regex functions, specialized cheminformatics libraries [33] | "Cl" (chlorine) is split into "C" and "l", confusing the model. |

| Embedding | Convert tokens into numerical vectors. This can be learned by the model or use pre-trained embeddings from models like ChemBERTa. | PyTorch (nn.Embedding), TensorFlow, Transformers libraries [33] |

Model treats each token as an independent symbol, missing chemical context. |

Troubleshooting Guide: My model fails to learn meaningful chemical patterns from SMILES data.

- Problem: Incorrect Tokenization of SMILES Strings.

- Symptoms: Model fails to converge, generates chemically invalid SMILES, or shows poor predictive performance.

- Solution: Implement a regular expression (regex)-based tokenizer that correctly handles multi-character atoms (e.g., "Cl", "Br") and complex bracketed expressions (e.g., "[Na+]") [33]. Do not use a naive character-level split.

Model Implementation and Workflow Integration

FAQ: What is a typical machine learning workflow for structure-based pharmacophore virtual screening?

A common strategy is to use a hybrid approach that combines structure-based methods with machine learning. The following workflow integrates SBVS with ML to improve screening efficiency.

Troubleshooting Guide: My virtual screening workflow is computationally too slow for large compound libraries.

- Problem: High Computational Cost of Structure-Based Screening.

- Symptoms: Docking millions of compounds takes days or weeks, creating a bottleneck.

- Solution:

- Implement a tiered screening approach: Use fast, ligand-based (LBVS) similarity searches (e.g., using Tanimoto coefficient on molecular fingerprints) or a simple ML classifier as a initial filter to reduce the library size before running more expensive SBVS [31].

- Optimize ML feature sets: Use dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA) or feature selection algorithms (e.g., Recursive Feature Elimination) to reduce the number of molecular descriptors fed to the ML model, speeding up training and prediction [30] [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table: Key Resources for ML-Driven Pharmacophore Screening

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | SMILES validation, descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation, molecular visualization. [33] | Data preprocessing, feature engineering, and result analysis. |

| Core ML Tools | Conversion Library | Converts models from PyTorch, TensorFlow into Core ML format for deployment on Apple devices. [35] [36] | Final model deployment and integration into mobile applications for on-device prediction. |

| Create ML | Model Training Tool (macOS) | Provides a no-code/low-code environment to train Core ML models on your Mac. [35] [36] | Rapid prototyping of ML models for tasks like image-based assay analysis or property prediction. |

| Schrödinger Suite | Commercial Software Platform | Physics-based molecular modeling, simulation, and high-throughput virtual screening. [37] | Structure-based pharmacophore generation, molecular docking (SBVS), and advanced simulation. |

| Exscientia AI Platform | AI-Driven Drug Discovery | Generative AI and automated design-make-test cycles for lead optimization. [37] | De novo molecular design and multi-parameter optimization of lead compounds. |

Deployment and Advanced Applications

FAQ: How can I deploy a trained cheminformatics model into a production environment for real-time screening?

Deployment strategies vary based on the target platform. For integrating models into applications on Apple devices (iOS, macOS, etc.), Core ML is the key framework [35] [36].

- Model Conversion: Trained models from popular frameworks like PyTorch and TensorFlow can be converted to the Core ML format (

.mlmodelfile) using the coremltools Python package [35] [36]. - On-Device Advantages: Core ML leverages the CPU, GPU, and Neural Engine on Apple hardware to run models on-device. This ensures data privacy, provides real-time inference without a network connection, and minimizes power consumption [35].

- Xcode Integration: The converted

.mlmodelfile can be directly integrated into your Xcode project, which automatically generates a ready-to-use Swift/Objective-C API for making predictions within your application [35].

Troubleshooting Guide: My deployed Core ML model performs differently than it did during training in Python.

- Problem: Discrepancy Between Training and Deployment Environments.

- Symptoms: Model accuracy drops or predictions are inconsistent after conversion to Core ML.

- Solution:

- Verify pre-processing parity: Ensure that the exact same data pre-processing steps (SMILES tokenization, feature scaling, etc.) are replicated identically in the deployment environment (e.g., your Swift app) as were used during model training in Python.

- Validate the converted model: Use Core ML Tools to validate the converted model on a sample dataset before deployment to check for conversion errors or precision losses [35] [36].

- Profile with Xcode: Use the Core ML performance reports and Instruments in Xcode to profile the model on the target device, checking for unexpected latency or hardware compatibility issues [35].

Methodologies in Action: AI Architectures and Workflows for Accelerated Screening

In machine learning-accelerated pharmacophore virtual screening, selecting and implementing the appropriate molecular representation is a foundational step that directly impacts the success of downstream tasks. This technical support center addresses common challenges researchers face when transitioning from traditional to modern AI-driven representation methods. The following guides and protocols are designed to help you navigate technical hurdles, optimize experimental setups, and validate your workflows within the context of advanced drug discovery research.

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: What are the primary considerations when choosing between SMILES strings and graph-based representations for a new virtual screening project?

The choice depends on your project's goals, data characteristics, and computational constraints. SMILES strings are text-based, human-readable, and work well with language models, but they can be syntactically invalid and struggle to explicitly capture complex topological information. Graph-based representations naturally model atoms (nodes) and bonds (edges), making them superior for tasks requiring an intrinsic understanding of molecular structure and topology, such as predicting complex bioactivity or generating novel scaffolds with specific stereochemistry. For a balanced approach, consider a hybrid model that uses both representations.

FAQ 2: Our model trained on ECFP fingerprints fails to generalize to novel scaffold classes. What could be the cause and potential solutions?

This is a classic problem of the "analogue bias" inherent in many fingerprint-based models. Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs) and other predefined descriptors may not capture the essential features responsible for bioactivity across structurally diverse compounds, leading to poor performance on out-of-distribution scaffolds.

- Solution 1: Employ Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). GNNs learn task-specific representations directly from the molecular graph, which can capture non-linear and complex structure-activity relationships that are opaque to fixed fingerprints [38].

- Solution 2: Utilize Contrastive Learning. Frameworks that use contrastive learning can learn embeddings by maximizing agreement between differently augmented views of the same molecule while pushing apart representations of different molecules. This forces the model to learn more robust, invariant features that are better for scaffold hopping [38].

- Solution 3: Implement a Hybrid Model. Combine ECFP features with learned representations from a GNN or other deep learning model to leverage both predefined chemical knowledge and data-driven insights.

FAQ 3: How can we effectively represent 3D molecular geometry and conformational information for pharmacophore-based models using standard 2D representations?

Standard 2D representations like SMILES or 2D graphs do not natively encode 3D conformation, which is critical for pharmacophore modeling where spatial relationships between features define biological activity.

- Approach 1: 3D Graph Representations. Enhance your graph representation by incorporating 3D spatial coordinates as node features. This allows GNNs to learn from both connectivity and geometric information.

- Approach 2: Geometric Deep Learning. Utilize specialized architectures like SE(3)-equivariant networks that are designed to be invariant to rotations and translations, making them inherently suited for 3D molecular data.

- Approach 3: Conformational Ensembles. For a simpler approach, generate multiple low-energy conformers for each molecule and represent the entire ensemble, either by pooling representations from each conformer or by using the conformer closest to the active pose for the target.

FAQ 4: What are the best practices for fine-tuning a pre-trained molecular transformer model (e.g., for a specific target family like GPCRs)?

Fine-tuning a pre-trained model on a smaller, target-specific dataset is an efficient way to achieve high performance.

- Model Selection: Choose a model pre-trained on a large, diverse chemical corpus (e.g., ChEMBL, ZINC).

- Data Preparation: Curate a high-quality, target-specific dataset. Ensure it is cleaned and standardized (e.g., canonical SMILES, removal of duplicates).

- Progressive Unfreezing: Do not unfreeze all layers at once. Start by fine-tuning only the last few layers, then progressively unfreeze earlier layers to avoid catastrophic forgetting.

- Task-Specific Head: Replace the pre-training head (e.g., masked language modeling) with a task-specific head suitable for your goal, such as a classification or regression layer.

- Learning Rate: Use a lower learning rate for the fine-tuning phase compared to the pre-training rate to make subtle adjustments to the weights.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Handling Invalid or Unrealistic SMILES from Generative Models

Problem: A generative model (e.g., a VAE or Transformer) produces a high rate of invalid or chemically unrealistic SMILES strings, hindering the discovery of viable lead compounds.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Check Training Data Quality: Ensure the training data consists of valid, canonicalized SMILES.

- Quantify Invalidity Rate: Calculate the percentage of invalid SMILES generated during sampling.

- Analyze Chemical Plausibility: Use rule-based filters (e.g., for unwanted functional groups) or a separate model to predict synthetic accessibility (SAscore) to check for unrealistic molecules even among valid SMILES.

Resolution Protocol:

- Switch to SELFIES: Consider using SELFIES (SELF-referencing Embedded Strings) instead of SMILES as the molecular representation. SELFIES are grammatically correct by design, guaranteeing 100% validity [38].

- Reinforce Validity during Training: Implement a reinforcement learning (RL) framework where the model receives a positive reward for generating valid and novel molecules, in addition to the primary objective (e.g., high predicted activity).

- Apply Post-Hoc Filtering: Integrate a robust post-processing pipeline that automatically discards invalid SMILES and filters chemically undesirable molecules using tools like RDKit.

Issue 2: Poor Model Performance on Imbalanced High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Data

Problem: A model trained on HTS data, where active compounds are rare, fails to identify true actives because it is biased toward the majority class (inactives).

Diagnosis Steps:

- Calculate Class Balance: Determine the ratio of active to inactive compounds in your dataset.

- Analyze Performance Metrics: Rely on metrics beyond accuracy, such as Precision-Recall (PR) curves, Area Under the PR Curve (AUPRC), and F1-score, which are more informative for imbalanced data.

- Review Data Splitting: Check if your training/test split preserves the class distribution (stratified splitting).

Resolution Protocol:

- Advanced Sampling Techniques:

- Apply SMOTE: Use Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique (SMOTE) to generate synthetic examples of the active class in the descriptor or embedding space.

- Use Weighted Random Sampling: During training, weight the sampling probability so that the model sees more examples from the under-represented active class.

- Algorithmic Cost-Sensitivity:

- Implement Focal Loss: Use Focal Loss, a modified cross-entropy loss that down-weights the loss assigned to well-classified examples, forcing the model to focus on hard, misclassified negatives (inactives mistaken for actives).

- Adjust Class Weights: Most ML libraries allow you to automatically adjust class weights inversely proportional to class frequencies in the loss function.

- Leverage Transfer Learning:

- Start with a model pre-trained on a large, balanced chemical dataset.

- Fine-tune the final layers on your specific, imbalanced HTS dataset. This provides a strong foundational understanding of chemistry before learning the specific task.

Issue 3: Inefficient Training or Inference with Graph Neural Networks on Large Virtual Compound Libraries

Problem: Training a GNN on a library of millions of compounds is prohibitively slow, or generating predictions (inference) for a virtual screen takes too long.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Profile Code: Use profiling tools to identify bottlenecks (e.g., data loading, graph convolution operations).

- Monitor Hardware Utilization: Check GPU/CPU and memory usage to see if resources are saturated.

- Check Batch Size: Determine if the batch size is too small (inefficient) or too large (causes memory overflow).

Resolution Protocol:

- Optimize Data Loading:

- Use a

DataLoaderthat supports parallel data loading. - Precompute and cache graph structures for the entire dataset to avoid on-the-fly processing during training.

- Use a

- Employ Graph Sampling:

- Use neighbor sampling methods (e.g., GraphSAGE) instead of full-graph training. This samples a node's local neighborhood for each batch, drastically reducing memory footprint and computation.

- Implement mini-batching of graphs for link prediction or graph classification tasks.

- Utilize Mixed-Precision Training:

- Use 16-bit floating-point precision (FP16) alongside 32-bit precision (FP32) to speed up computations and reduce memory usage on supported GPUs.

- Model Simplification:

- Reduce the number of GNN layers. Very deep GNNs can suffer from over-smoothing and are computationally expensive.

- Consider using simpler, faster convolution operations (e.g., SAGEConv instead of GINConv) for large-scale screening.

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Molecular Representations for Scaffold Hopping

Objective: To systematically evaluate the performance of different molecular representations in identifying structurally diverse compounds (different scaffolds) with similar biological activity.

Materials:

- Dataset: A curated bioactivity dataset (e.g., from ChEMBL) for a well-defined protein target, with known active compounds clustered by Bemis-Murcko scaffolds.

- Software: RDKit, DeepChem, PyTorch Geometric, or equivalent libraries.

Methodology:

- Data Preparation & Splitting:

- Cluster molecules by their Bemis-Murcko scaffolds.

- Perform a scaffold split, where all molecules from entire scaffolds are held out for the test set. This rigorously tests the model's ability to generalize to novel chemotypes.

- Model Training & Representation:

- Train identical machine learning models (e.g., a Random Forest or a simple GNN) using different molecular representations on the training set.

- Representations to Test:

- Fingerprint-based: ECFP6, MACCS Keys.

- Descriptor-based: A set of physicochemical descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP, TPSA).

- Graph-based: A Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN) operating on 2D graphs.

- Language model-based: Features extracted from a pre-trained molecular Transformer model.

- Evaluation:

- Predict activity on the held-out test set containing novel scaffolds.

- Evaluate using metrics focused on early retrieval: Hit Rate (top 1%), Enrichment Factor (EF) at 1%, and Area Under the Accumulative Recall Curve.

Anticipated Results: Graph-based and language model-based representations are expected to significantly outperform traditional fingerprints and descriptors on the scaffold-split test set, demonstrating their superior ability to capture the essential features of bioactivity beyond simple structural similarity [38].

Protocol 2: Integrating Multimodal Representations for ADMET Prediction

Objective: To improve the predictive accuracy of ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) properties by combining multiple molecular representations.

Methodology:

- Feature Extraction:

- Extract features for each molecule in the dataset using several representation methods concurrently.

- Modality 1 (Graph): A GNN to extract topological features.

- Modality 2 (SMILES): A Transformer encoder to extract sequential features.

- Modality 3 (3D): Geometric features from a low-energy conformer (e.g., 3D coordinates fed to a different network or used to compute 3D descriptors).

- Multimodal Fusion:

- Employ a fusion strategy to combine the extracted feature vectors. Simple early fusion (concatenation) can be used, or more complex late fusion (e.g., using an attention mechanism to weight the importance of each modality) can be implemented.

- Prediction:

- Feed the fused, multimodal representation into a final prediction head (a fully connected network) for the specific ADMET endpoint (e.g., hERG inhibition, microsomal stability).

Validation: Compare the performance of the multimodal model against unimodal baselines (using only graph, SMILES, or 3D features) via cross-validation on standard ADMET benchmarks like those in the MoleculeNet dataset. The multimodal approach is designed to provide a more holistic view of the molecule, leading to more robust and accurate predictions [38].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Molecular Representation Methods

| Representation Type | Example Methods | Data Structure | Key Advantages | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| String-Based | SMILES, SELFIES [38] | Sequential Text | Simple, compact, works with NLP models [38] | Molecular generation, language model pre-training |

| Fingerprint-Based | ECFP, MACCS Keys [38] | Fixed-length Bit Vector | Fast, interpretable, good for similarity search [38] | QSAR, high-throughput virtual screening, clustering |

| Graph-Based | GIN, MPNN [38] | Graph (Nodes/Edges) | Naturally encodes structure, powerful for property prediction [38] | Predicting complex bioactivity, scaffold hopping, lead optimization |

| 3D & Geometric | SchNet, SE(3)-Transformer | 3D Coordinates / Point Cloud | Captures spatial and conformational data | Pharmacophore screening, protein-ligand interaction prediction |

Table 2: Performance Benchmark of Representations on a Public Activity Dataset (e.g., HIV)

| Representation | Model | AUC-ROC (Random Split) | AUC-ROC (Scaffold Split) | Inference Speed (molecules/sec) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECFP6 | Random Forest | 0.81 | 0.65 | > 100,000 |

| Molecular Graph | GIN | 0.85 | 0.78 | ~ 10,000 |

| SMILES String | Transformer | 0.83 | 0.75 | ~ 5,000 |

| Multimodal (Graph+SMILES) | Fused GIN-Transformer | 0.87 | 0.80 | ~ 3,000 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Libraries for Molecular Representation Research

| Item | Function | Resource Link |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit for working with molecules (generating SMILES, fingerprints, graphs, descriptors). | https://www.rdkit.org |

| DeepChem | Deep learning library specifically for drug discovery, offering implementations of various molecular models and datasets. | https://deepchem.io |

| PyTorch Geometric | Library for deep learning on graphs, with extensive GNN architectures and easy-to-use molecular data loaders. | https://pytorch-geometric.readthedocs.io |

| Hugging Face Mol-Community | Platform hosting pre-trained molecular transformer models (e.g., ChemBERTa) for transfer learning. | https://huggingface.co/models?library=transformers&search=mol |

| Open Babel | A chemical toolbox for interconverting file formats and handling molecular data. | http://openbabel.org/wiki/Main_Page |

Workflow Diagrams

Molecular Representation and Model Evaluation Workflow

Multimodal Molecular Representation Fusion

What is the fundamental principle behind using Machine Learning to predict docking scores?

The core principle involves training machine learning (ML) models to learn the relationship between a compound's chemical structure and its docking score, bypassing the need for computationally intensive molecular docking simulations. These models use molecular fingerprints or descriptors as input to directly predict the binding energy score that traditional docking software would calculate. This approach can accelerate virtual screening by up to 1000 times compared to classical docking-based methods, enabling the rapid evaluation of extremely large chemical databases [5].

How does this ML approach differ from traditional molecular docking and QSAR models?

This ML methodology represents a hybrid approach that addresses key limitations of both traditional docking and Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models.

- Versus Traditional Docking: Molecular docking is computationally expensive, requiring time-consuming pose generation and scoring for each compound, making it infeasible for screening billions of molecules [5]. The ML approach predicts scores directly from 2D structures, dramatically increasing speed.

- Versus QSAR Models: Traditional QSAR models predict biological activity (e.g., IC₅₀) based on ligand structure but are highly dependent on the quality and quantity of experimental training data. They can be unreliable for novel chemotypes not represented in the training set [5]. In contrast, the described ML method learns from docking results, which are more readily generated in silico, and does not rely on scarce or incoherent experimental activity data [5].

The following table summarizes the key differences:

Table 1: Comparison of Virtual Screening Approaches

| Feature | Traditional Docking | Classical QSAR Models | ML-based Docking Score Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basis of Prediction | Physical simulation of binding | Ligand structure -> Experimental activity | Ligand structure -> Docking score |

| Computational Speed | Slow (hours/days for large libraries) | Fast | Very Fast (~1000x faster than docking) [5] |

| Data Dependency | Requires protein structure | Limited by available bioactivity data | Limited by docking data (can be generated) |

| Handling Novel Chemotypes | Good (structure-based) | Poor | Good (trained on diverse docking data) |

Experimental Protocol & Workflow

This section outlines a detailed, step-by-step protocol for implementing an ML-based docking score prediction pipeline, as demonstrated in the development of monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors [5].

Step 1: Data Set Curation and Preparation

- Source Bioactivity Data: Download known ligands for your target protein from public databases like ChEMBL. For MAO inhibitors, researchers retrieved 2,850 MAO-A and 3,496 MAO-B records with Ki and IC₅₀ values [5].

- Filter Compounds: Remove compounds with high molecular weight (e.g., >700 Da) and highly flexible structures to reduce docking complexity and errors [5].

- Generate Docking Scores:

- Prepare the protein structure (e.g., from PDB IDs 2Z5Y for MAO-A, 2V5Z for MAO-B) by removing native ligands and water molecules [5].

- Use docking software (e.g., Smina) to calculate a docking score for every compound in your curated dataset [5]. This score will be the target variable for the ML model.

- Transform Activity Data (Optional): For models predicting bioactivity directly, convert IC₅₀ values to pIC₅₀ (-log₁₀IC₅₀) to normalize the data distribution [5].

Step 2: Data Splitting Strategy

To rigorously evaluate the model's performance and generalizability, employ a careful data splitting strategy:

- Random Split: A simple random split (e.g., 70/15/15 for train/validation/test) repeated multiple times to account for data variability [5].

- Scaffold-Based Split: Split data based on compound Bemis-Murcko scaffolds to ensure the model is tested on entirely new chemotypes, providing a more realistic assessment of its screening capability [5].

- Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) Guided Split: Sample multiple splits and select those where the distribution of activity labels (e.g., pIC₅₀) across training, validation, and test sets is most similar, as measured by the lowest D statistic in a two-sample KS test [5].

Step 3: Feature Engineering and Molecular Representation

Generate numerical representations (features) for each compound that the ML model can learn from. Using an ensemble of different representations can reduce prediction errors [5].

- Molecular Fingerprints: Binary vectors that represent the presence or absence of specific substructures or patterns in the molecule.

- Molecular Descriptors: Numerical values that capture physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, logP, polar surface area).

Step 4: Machine Learning Model Training and Validation

- Model Selection: Train an ensemble model or use algorithms like Random Forest (RF), which is well-suited for this task and has been successfully applied in scoring functions like RF-Score [39].

- Training: Use the training set (molecular features as input, docking scores as output) to fit the model.

- Validation & Hyperparameter Tuning: Use the validation set to optimize model parameters and prevent overfitting.

- Performance Evaluation: Evaluate the final model on the held-out test set. Common metrics include Pearson's correlation coefficient (R) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) between predicted and actual docking scores.

The entire workflow for creating and applying the model is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Resources for ML-based Docking Score Prediction

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Reference/URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL | Database | Source of bioactive molecules with reported binding affinities (Ki, IC₅₀) for model training. | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/ [5] |

| PDBbind | Database | Comprehensive collection of protein-ligand complexes with binding data for benchmarking. | http://www.pdbbind.org.cn/ [39] |

| ZINC | Database | Large, commercially available database of compounds for virtual screening. | https://zinc.docking.org/ [5] |

| TCMBank / HERB | Database | Libraries of natural products for screening, as used in identifying GSK-3β inhibitors [28]. | N/A |

| Smina | Software | Molecular docking software used to generate the target docking scores for training. | https://sourceforge.net/projects/smina/ [5] |

| RF-Score | Software/Algorithm | A Random Forest-based scoring function demonstrating the application of ML to binding affinity prediction. | N/A [39] |

| KarmaDock | Software/Algorithm | A deep learning-based molecular docking platform used in integrated screening frameworks [28]. | N/A |

| ICM | Software | Commercial molecular modeling software suite with docking and scripting capabilities. | https://www.molsoft.com/ [40] |

Troubleshooting FAQs

Q1: My ML model shows excellent performance on the test set but fails to identify active compounds in real-world screening. What could be wrong?

A: This is a classic sign of the model failing to generalize, often due to an improper data splitting strategy.

- Solution: Avoid simple random splits. Use a scaffold-based splitting method, which ensures that the test set contains molecular scaffolds not seen during training. This more rigorously tests the model's ability to predict for truly novel chemotypes and provides a better estimate of real-world screening performance [5].

- Proactive Measure: Enhance the diversity and size of your training data. The performance of ML scoring functions like RF-Score has been shown to improve dramatically with increased training set size [39].