Liquid Biopsy and Circulating Tumor DNA: A Revolutionary Tool for Cancer Detection and Monitoring

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of liquid biopsy and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis in modern oncology.

Liquid Biopsy and Circulating Tumor DNA: A Revolutionary Tool for Cancer Detection and Monitoring

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of liquid biopsy and circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis in modern oncology. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biology of ctDNA, cutting-edge detection methodologies like NGS and dPCR, and their clinical applications in multi-cancer early detection (MCED), minimal residual disease (MRD) monitoring, and guiding targeted therapies. The content also critically addresses current technical challenges, optimization strategies, and the robust validation framework from clinical trials that is cementing ctDNA's utility in precision medicine, shaping the future of cancer diagnostics and treatment.

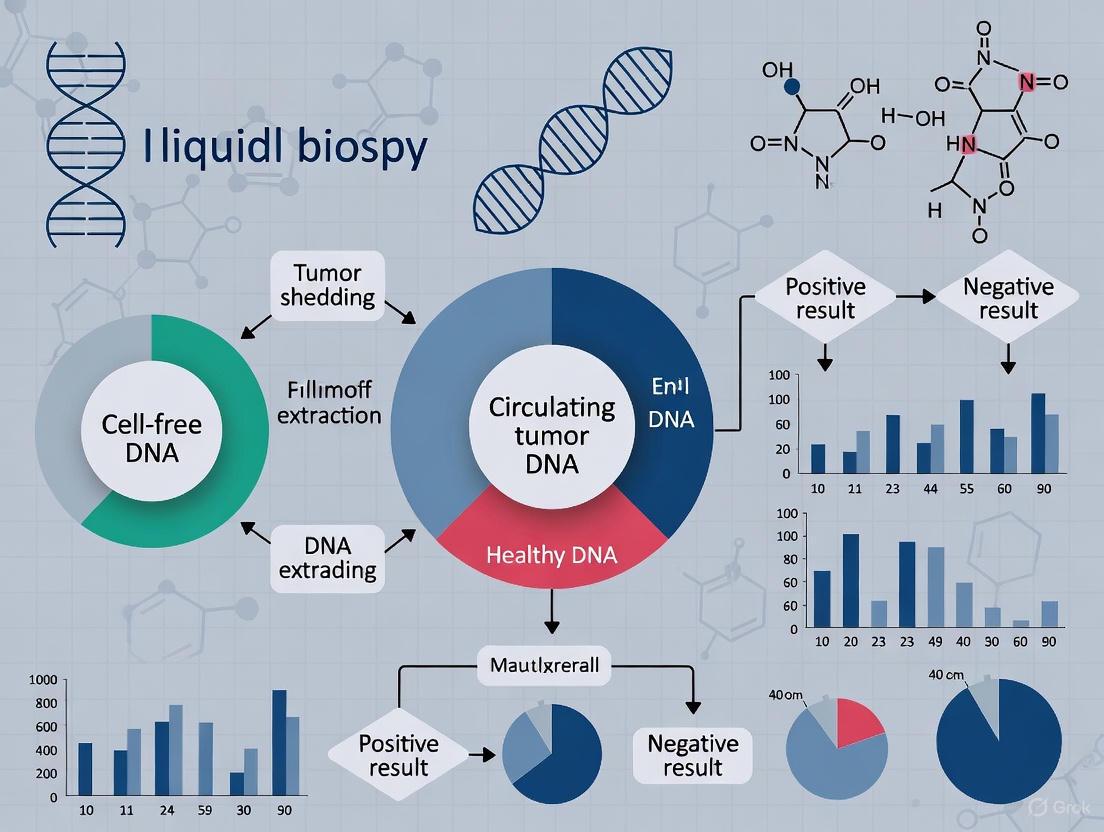

The Biology and Rising Significance of Circulating Tumor DNA

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) refers to fragmented DNA released from tumor cells into the bloodstream and other bodily fluids [1] [2]. As a component of cell-free DNA (cfDNA), ctDNA carries tumor-specific genetic and epigenetic alterations, making it a critical analyte in liquid biopsies for cancer detection, monitoring, and management [3] [4]. The analysis of ctDNA provides a non-invasive means to assess tumor dynamics, genomic heterogeneity, and treatment response, representing a paradigm shift in precision oncology [5] [6]. This technical guide examines the fundamental biological characteristics of ctDNA, its mechanisms of release and clearance, and the advanced methodologies employed in its detection, providing a scientific foundation for its application in cancer research and drug development.

Biological Origins and Mechanisms of Release

ctDNA originates through several biological processes, with contributions from various cellular compartments within the tumor ecosystem. The diagram below illustrates the primary mechanisms of ctDNA release into the bloodstream.

The primary sources of ctDNA include:

Apoptotic Tumor Cells: This is considered a major source of ctDNA [1]. Apoptosis produces characteristic DNA fragments of approximately 166 base pairs, corresponding to mono-nucleosomes, which display a "ladder-like" distribution upon electrophoresis [1] [7]. During programmed cell death, cellular DNA is cleaved by endonucleases, and the resulting fragments are packaged into apoptotic bodies that may be cleared by phagocytes or released into circulation [1].

Necrotic Tumor Cells: Cells undergoing necrotic death due to hypoxia or metabolic stress release DNA in a more random, non-specific fragmentation pattern, often producing longer DNA fragments [1] [7]. Patients with advanced cancer and substantial tumor necrosis often demonstrate higher plasma ctDNA levels [1].

Active Secretion from Living Tumor Cells: Evidence suggests that viable tumor cells can actively release DNA and DNA-protein complexes through secretion mechanisms independent of cell death [1] [7]. One in vitro study found that ctDNA release from cultured cancer cells correlated with the percentage of cells in G1 phase rather than apoptosis or necrosis levels [7].

Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs): CTCs that have detached from the primary tumor and entered circulation can release DNA directly into the bloodstream [1]. However, given the relatively low abundance of CTCs compared to the total tumor cell burden, this is unlikely to be the primary source of ctDNA [7].

The relative contribution of each mechanism varies depending on tumor type, location, disease stage, and treatments administered [7].

ctDNA in Metastasis: The Genometastasis Hypothesis

Beyond its role as a passive biomarker, experimental evidence suggests ctDNA may actively participate in cancer progression through the "genometastasis" hypothesis [1]. This proposes that ctDNA fragments containing oncogenes might be taken up by susceptible normal cells in distant organs, leading to their oncogenic transformation and potentially contributing to metastasis formation [1]. Studies have demonstrated that plasma from tumor-bearing rats and supernatants from human cancer cells can transform normal cells in vitro, an effect abolished when DNA is removed from these fluids [1]. While intriguing, this hypothesis requires further validation, particularly through in vivo clinical studies [1].

Physical and Molecular Characteristics

Quantitative and Structural Properties

ctDNA exhibits distinct physical and molecular characteristics that differentiate it from non-tumor cfDNA and inform detection methodologies.

Table 1: Physical and Molecular Characteristics of ctDNA

| Characteristic | Description | Research Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Size Distribution | Typically shorter fragments (90-150 bp) than non-tumor cfDNA; some studies report both extremely long and short fragments in cancer patients [1] [5]. | Enables size-selection enrichment strategies; short fragment enrichment can increase variant allele frequency in sequencing libraries [5]. |

| Molecular Form | Primarily double-stranded DNA, existing as mono- and oligonucleosomes, or within extracellular vesicles (1-10 µm) [1] [7]. | Influences isolation methods; vesicle-associated DNA may be protected from degradation [7]. |

| Concentration Range | Highly variable (0.01% to >90% of total cfDNA); correlates with tumor burden, stage, and metabolic activity [7] [4]. | Early-stage/low-shedding tumors present detection challenges; requires highly sensitive techniques [5] [4]. |

| Half-Life | Short half-life, estimated between 16 minutes to several hours [4]. | Enables real-time monitoring of tumor dynamics and treatment response [4]. |

| Genetic Features | Harbors tumor-specific alterations: point mutations, copy number variations, chromosomal rearrangements, methylation changes, and viral sequences [1] [3]. | Provides markers for detection, monitoring, and therapeutic targeting [1] [6]. |

The half-life of ctDNA is particularly noteworthy for its clinical applications. The brief circulation time, estimated between 16 minutes and several hours, reflects efficient clearance mechanisms primarily by the liver, kidneys, and nuclease activity in the blood [4]. This rapid turnover enables ctDNA levels to reflect real-time tumor dynamics, making it a valuable biomarker for monitoring treatment response and disease progression [4].

Comparative Analysis: ctDNA vs. General cfDNA

Understanding the differences between ctDNA and total cfDNA is fundamental for assay development.

Table 2: Key Differences Between ctDNA and General cfDNA

| Parameter | Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) | General Cell-Free DNA (cfDNA) |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Exclusively derived from tumor cells [1] [2]. | Derived from apoptosis/necrosis of normal cells, primarily hematopoietic lineages (e.g., white blood cells, erythrocyte progenitors) [7] [8]. |

| Genetic Content | Contains tumor-specific somatic mutations, copy number alterations, methylation changes, and rearrangements [1] [5]. | Reflects germline genome of the individual without tumor-specific alterations [2]. |

| Typical Fragment Size | Often shorter fragments; can show more diverse fragmentation patterns [1] [5] [3]. | More uniform fragment distribution, with a peak around 166 bp [8]. |

| Proportion in Blood | Can vary from <0.01% in early-stage disease to >90% in advanced metastatic cancer [5] [4]. | Comprises the majority of cell-free DNA in plasma, even in cancer patients [8]. |

| Clinical Utility | Biomarker for cancer detection, prognosis, treatment response, MRD, and resistance mutation identification [5] [6] [2]. | Useful in non-oncology applications (e.g., non-invasive prenatal testing, transplant rejection) [6] [8]. |

Advanced Detection Methodologies and Protocols

The low abundance of ctDNA in total cfDNA, particularly in early-stage cancers or minimal residual disease (MRD), demands highly sensitive and specific detection technologies [5] [6]. The following workflow outlines a generalized protocol for ctDNA analysis, from sample collection to data interpretation.

Critical Experimental Steps and Considerations

Sample Collection and Processing: Blood samples are collected in stabilizing tubes (e.g., Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT) to prevent genomic DNA contamination from white blood cell lysis [5]. Plasma is separated from whole blood via a two-step centrifugation process within hours of collection to ensure sample integrity [5] [4].

cfDNA Extraction and Quantification: cfDNA is isolated from plasma using specialized kits optimized for short fragments, such as magnetic bead-based technologies (e.g., MagMAX Cell-Free DNA Isolation Kit) [5] [8]. The extracted DNA is then quantified using fluorometric methods sensitive to low concentrations.

Library Preparation and Enhancement:

- Size Selection: Libraries can be enriched for shorter fragments (90-150 bp) to increase the relative abundance of tumor-derived DNA, improving the detection of low-frequency variants [5].

- Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs): Short nucleotide barcodes are added to individual DNA molecules before amplification. This allows bioinformatic correction of PCR amplification errors and sequencing artifacts, significantly improving detection sensitivity and specificity [4].

Analysis and Detection:

- PCR-Based Methods: Digital PCR (dPCR) and droplet digital PCR (ddPCR) enable absolute quantification of known mutations with high sensitivity (down to ~0.1% variant allele frequency) and rapid turnaround, suitable for monitoring specific mutations like ESR1 in breast cancer or KRAS in colorectal cancer [3] [4].

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS):

- Targeted NGS Panels: Methods like CAPP-Seq (Cancer Personalized Profiling by Deep Sequencing) and TEC-Seq (Targeted Error Correction Sequencing) focus on specific genomic regions of interest, allowing for deep sequencing and detection of rare variants down to ~0.01% VAF [5] [4].

- Structural Variant (SV) Analysis: Identifying tumor-specific chromosomal rearrangements (e.g., translocations) can achieve parts-per-million sensitivity, as these breakpoints are virtually absent in non-tumor DNA [5].

- Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS): Low-coverage WGS can assess copy number alterations and fragmentation patterns (fragmentomics) to infer the presence of cancer, even without prior knowledge of specific mutations [3] [4].

Emerging Sensing Technologies: Nanomaterial-based electrochemical biosensors are under development for rapid, sensitive ctDNA detection. These platforms use graphene, molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂), or magnetic nano-electrodes to transduce DNA hybridization events into electrical signals, achieving attomolar sensitivity in some cases [5].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful ctDNA analysis requires a suite of specialized reagents and instruments throughout the workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for ctDNA Analysis

| Reagent/Solution Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes | Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT, PAXgene Blood ccfDNA Tubes | Stabilize nucleated blood cells to prevent lysis and preserve cfDNA profile post-phlebotomy. |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | MagMAX Cell-Free DNA Isolation Kit, QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit | Isolation and purification of short-fragment cfDNA from plasma/serum with high efficiency and reproducibility. |

| Library Preparation Kits | KAPA HyperPrep Kit, Illumina DNA Prep Kit | Convert fragmented, double-stranded cfDNA into sequencing-ready libraries via end-repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation. |

| Target Enrichment Probes | IDT xGen Lockdown Probes, Twist Pan-Cancer Panel | Hybridization-based capture of genomic regions of interest (e.g., cancer gene panels) from complex sequencing libraries. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | IDT UMI Adapters, Twist UMI Adapters | Molecular barcoding of original DNA molecules pre-amplification to enable accurate error correction and quantification. |

| PCR Reagents | ddPCR Supermix, Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplification of target sequences with high specificity and fidelity for detection (ddPCR) or library generation (NGS). |

| Sequence Capture Beads | MyOne Streptavidin T1 Beads, AMPure XP Beads | Magnetic bead-based purification and size selection of nucleic acids during library preparation and target enrichment. |

ctDNA is a dynamically informative biomarker with defined biological origins, distinct physical characteristics, and a short half-life that enables real-time monitoring of cancer [1] [4]. Its detection relies on sophisticated technologies capable of discriminating rare tumor-derived fragments against a background of normal cfDNA [5] [6]. As research continues to refine detection methodologies and validate clinical applications, ctDNA analysis is poised to become an increasingly integral component of precision oncology, offering a non-invasive window into tumor evolution, treatment response, and resistance mechanisms [9] [6] [4]. Future directions will focus on standardizing protocols, validating clinical utility in large-scale trials, and integrating multi-omic data to fully realize the potential of liquid biopsies in cancer management.

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), comprising small fragments of DNA shed from tumor cells into the bloodstream, has emerged as a pivotal biomarker in oncology [3]. Its analysis, a core component of liquid biopsy technologies, represents a paradigm shift from traditional tissue biopsies by offering a non-invasive method for cancer detection, treatment monitoring, and prognosis [10]. The global market for ctDNA technologies is experiencing explosive growth, propelled by advances in precision oncology, rising cancer prevalence, and increasing demand for minimally invasive diagnostic tools [11]. This trajectory is underpinned by a rapidly expanding evidence base from clinical trials, demonstrating the utility of ctDNA assays in everything from early cancer detection to guiding therapy in advanced disease [9]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth analysis of the projected market growth, key technological drivers, and the experimental frameworks establishing the clinical validity of ctDNA analysis.

Global Market Size and Projections

The circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) market is on a steep growth curve, transforming from a niche research area into a multi-billion-dollar clinical industry. The market expansion is quantified by a robust Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR), reflecting widespread adoption and continued innovation [11].

Table 1: Global ctDNA Market Size Projections (2025-2034)

| Year | Market Size (USD Billion) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 2025 | 7.96 | Calculated base year [11] |

| 2026 | 9.14 | [11] |

| 2034 | 27.67 | Projected value [11] |

| CAGR (2025-2034) | 14.85% | [11] |

This growth is not uniformly distributed geographically. Current dominance and future hotspots are clear:

- North America dominated the market in 2024, holding a 51% share [11]. The U.S. market alone is projected to grow from USD 3.09 billion in 2025 to approximately USD 10.90 billion by 2034, at a slightly higher CAGR of 15.02% [11].

- Asia-Pacific is identified as the fastest-growing region from 2025 to 2034, driven by expanding healthcare infrastructure, rising cancer incidence, and growing investment in precision medicine [11].

Key Market Drivers and Segment Analysis

The market's expansion is fueled by several interconnected factors. The rising global prevalence of cancer is a primary driver, creating an urgent need for better diagnostic and monitoring tools [11] [12]. Concurrently, there is a growing clinical and patient demand for non-invasive diagnostics to overcome the limitations of invasive tissue biopsies, such as procedural risks, sampling bias due to tumor heterogeneity, and inability to perform frequent monitoring [10] [13]. Furthermore, advancements in sequencing technologies and the broader growth of precision oncology, which relies on detailed genetic profiling to select targeted therapies, are fundamental enablers of the ctDNA market [11].

The market can be segmented to provide a clearer picture of its dynamics and leading applications.

Table 2: Key Market Segments and Leading Applications

| Segment | Leading Sub-Segment and Share | Fastest-Growing Sub-Segment |

|---|---|---|

| Technology | Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) (48% share in 2024) [11] | PCR-based assays [11] |

| Application | Cancer Diagnosis and Screening (53% share in 2024) [11] | Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) Monitoring [11] |

| Sample Test | Blood (82% share in 2024) [11] | Urine [11] |

| End-User | Clinical Laboratories & Diagnostic Centers (51% share in 2024) [11] | Biopharma Companies [11] |

The dominance of NGS is due to its ability to analyze multiple genetic alterations simultaneously without prior knowledge of the tumor's mutation profile, making it ideal for comprehensive genomic profiling [3] [11]. Meanwhile, PCR-based assays are growing rapidly due to their cost-effectiveness, high sensitivity for detecting known mutations, and faster turnaround times, making them suitable for targeted applications like monitoring specific mutations [3] [11]. The leadership of the cancer diagnosis and screening segment underscores the critical role of ctDNA in early detection. However, the MRD monitoring segment's rapid growth highlights a pivotal application: using ctDNA to detect trace amounts of cancer cells after curative-intent therapy (surgery or chemo/radiation), often months before clinical or radiological recurrence [3] [14] [12].

Market Growth Drivers and Key Segments

Technological Foundations and Experimental Protocols

The clinical utility of ctDNA is made possible by highly sensitive analytical methods capable of detecting rare mutant DNA molecules in a vast background of wild-type cell-free DNA (cfDNA) derived from normal cells [3] [10].

Core Detection Technologies

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): This is the workhorse for comprehensive ctDNA profiling. Methods include:

- Targeted Error Correction Sequencing (TEC-Seq): An ultra-deep, highly multiplexed sequencing method that uses redundant sequencing and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to distinguish true low-frequency mutations from errors introduced during PCR and sequencing [3].

- CAncer Personalized Profiling by deep Sequencing (CAPP-Seq): A method that uses selector probes to enrich for genomic regions that are frequently mutated in a particular cancer type, allowing for efficient and sensitive monitoring of tumor-derived DNA [3].

- Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) & Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES): Used for hypothesis-free discovery of mutations, though their use in ctDNA is sometimes limited by cost and the need for high sequencing depth to achieve good sensitivity [3].

- PCR-Based Methods: These are highly sensitive for detecting pre-specified mutations.

- Digital Droplet PCR (ddPCR): Partitions a sample into thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets, so that each droplet contains either zero or one target DNA molecule. After PCR amplification, the droplets are counted as positive or negative, allowing for absolute quantification of the mutant allele with very high sensitivity [3].

- BEAMing (Beads, Emulsion, Amplification, and Magnetics): Similar in principle to ddPCR, it uses emulsion PCR on magnetic beads to isolate and amplify single DNA molecules, which are then detected via flow cytometry [3] [10].

- Emerging Approaches:

- Methylomics: Analyzes the DNA methylation patterns on ctDNA, which are highly cell-type specific. Methods include whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) to identify cancer-specific methylation signatures that can be used for early detection and cancer typing [3] [10].

- Fragmentomics: Analyzes the patterns of cfDNA fragmentation, such as fragment size and end motifs, which differ between non-cancer and cancer-derived DNA. The DELFI (DNA evaluation of fragments for early interception) method uses machine learning on low-coverage WGS data to detect cancer based on these fragmentation profiles [3].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Tumor-Informed ctDNA MRD Detection

The following protocol, as used in studies like the VICTORI trial for colorectal cancer, details the gold-standard approach for detecting Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) with high sensitivity [14].

Objective: To detect the presence of ctDNA in plasma following curative-intent surgery to identify patients with MRD who are at high risk of relapse.

Workflow:

Tumor-Informed MRD Detection Workflow

- Tumor Whole Exome/Genome Sequencing: DNA is extracted from the patient's resected primary tumor tissue and matched normal sample (e.g., buffy coat from blood). Whole exome or genome sequencing is performed to identify a set of somatic mutations unique to the patient's tumor [14].

- Personalized Panel Design: A custom sequencing panel is computationally designed for the patient, targeting up to 1,800 somatic single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small insertions/deletions (indels) identified in step 1. This patient-specific "fingerprint" is what allows for ultra-sensitive tracking [14].

- Longitudinal Plasma Collection: Blood samples are collected at defined timepoints:

- Pre-operatively (to confirm baseline ctDNA detectability).

- Post-operatively every 2 weeks for the first 8 weeks (a critical window for adjuvant therapy decisions).

- Thereafter, every 3 months for long-term monitoring (e.g., 3 years) [14].

- Plasma Processing and cfDNA Extraction: Blood samples are processed to isolate plasma. Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) is then extracted from the plasma using commercial kits based on magnetic bead-based technology, which maximizes recovery of short, fragmented DNA [14] [13].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Sequencing libraries are prepared from the extracted cfDNA using the personalized panel for target enrichment. The libraries are then sequenced on a high-throughput NGS platform [14].

- Bioinformatic Analysis and Variant Calling: The NGS data is processed through a customized bioinformatics pipeline. This pipeline performs alignment, UMI-aware deduplication, and ultra-sensitive variant calling to detect the patient-specific mutations in the plasma. Sensitivity can reach levels as low as 2 parts per million (ppm), enabling the detection of minute amounts of ctDNA [14].

- Interpretation: A sample is called "ctDNA positive" if a statistically significant number of patient-specific variants are detected above the background noise level.

Key Findings from this Protocol (VICTORI Interim Analysis):

- ctDNA was detected 198 days earlier than imaging on average, with one case detected 416 days prior to clinical recurrence [14].

- 87% of patients who later had a clinical recurrence were ctDNA-positive within the first 8 weeks after surgery [14].

- Higher ctDNA levels at first detection correlated with a shorter time to clinical relapse, providing prognostic value [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful ctDNA research and assay development relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions and their critical functions in the experimental workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ctDNA Analysis

| Research Solution | Critical Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| cfDNA Extraction Kits (Magnetic Bead-Based) | Isolation of high-quality, short-fragmented cfDNA from plasma/serum while inhibiting nucleases. Maximizes yield from limited samples (<1 mL plasma) [13]. | Superior recovery of short fragments vs. traditional column-based methods. Automation-compatible for high-throughput processing and consistency [13]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) Adapters | Tagging of individual DNA molecules pre-amplification to enable bioinformatic error correction and accurate quantification. Essential for distinguishing low-frequency mutations from sequencing artifacts [3]. | Reduces background noise, enabling ultra-sensitive detection down to <0.1% variant allele frequency (VAF). |

| Multiplex PCR Panels & Hybridization Capture Probes | Target enrichment for NGS. Panels amplify specific genes; probes hybridize to and pull down regions of interest from complex genomic libraries [3] [15]. | Allows focused, deep sequencing of cancer-associated genes (e.g., 33-gene pan-cancer panel [15]) or patient-specific mutations. |

| Digital PCR Master Mixes & Assays | Absolute quantification of known mutations without the need for NGS. Provides high sensitivity and specificity in a rapid workflow [3]. | Ideal for longitudinal monitoring of specific mutations (e.g., ESR1 in breast cancer [9]) after they have been identified. |

| Bisulfite Conversion Reagents | Chemical modification of unmethylated cytosines to uracils, allowing for subsequent PCR-based discrimination of methylated DNA. Foundational for methylomic analysis [3]. | Enables study of DNA methylation biomarkers. Bisulfite-free methods (e.g., MeDIP-Seq) are emerging to avoid DNA degradation [3]. |

| Automated Nucleic Acid Purification Systems | High-throughput, hands-free purification of cfDNA from large sample volumes. Reduces manual labor and inter-sample variability [13]. | Critical for reproducible processing in large-scale clinical trials and commercial testing laboratories. |

Clinical Trial Evidence and Current Challenges

Recent clinical trials presented in 2025 have significantly advanced the evidence base for ctDNA, moving from prognostic validation to demonstrations of clinical utility.

- SERENA-6 Trial (Advanced Breast Cancer): This landmark study demonstrated that switching therapy based on ctDNA findings improves patient outcomes. Patients with advanced HR+/HER2- breast cancer receiving first-line aromatase inhibitor and CDK4/6 inhibitor therapy were monitored with ctDNA for emerging ESR1 mutations. Those with ESR1 mutation detected without radiological progression were randomized to switch to camizestrant (a SERD) or continue aromatase inhibitor. The study met its primary endpoint, showing a statistically significant improvement in Progression-Free Survival (PFS) and Quality of Life (QoL) for the group that switched therapy, establishing the utility of ctDNA to guide therapy in advanced disease [9].

- DYNAMIC-III Trial (Stage III Colon Cancer): This was the first prospective randomized study of ctDNA-informed management in resected stage III colon cancer. While ctDNA positivity after surgery was confirmed as a strong prognostic marker for recurrence, the primary analysis showed that treatment escalation based on ctDNA status did not improve Recurrence Free Survival (RFS). This highlights a critical challenge: while ctDNA is excellent for identifying risk, the effectiveness of the strategy depends on having therapies capable of eradicating MRD. The results suggest limitations in the available chemotherapy escalation regimens (FOLFOXIRI vs. doublet) rather than in the ctDNA assay itself [9].

- Real-World Evidence: A large retrospective study from Memorial Sloane Kettering, analyzing a real-world cohort of over 4,900 patients with advanced breast cancer, found that early on-treatment ctDNA dynamics were associated with time to next treatment, reinforcing the potential of ctDNA as a dynamic biomarker for treatment efficacy in routine practice [9].

Despite the progress, challenges remain. In early cancer detection, the limited sensitivity of non-tumor-informed ctDNA assays for early-stage cancers (due to very low ctDNA levels) is a key hurdle [9]. There is also a lack of standardization in sample collection, analysis, and clinical interpretation across platforms [3]. Furthermore, confounding factors from non-cancerous conditions (e.g., chronic inflammatory diseases) can release cfDNA and potentially interfere with tests [3]. Finally, as seen in DYNAMIC-III, the clinical utility of ctDNA-driven interventions is contingent on the availability of effective treatments for MRD-positive patients [9].

The global market trajectory for ctDNA is one of robust, sustained growth, firmly rooted in technological advancement and mounting clinical evidence. The market's projected expansion to over USD 27 billion by 2034 is driven by the critical convergence of clinical need, technological innovation (particularly in NGS and PCR), and the demonstrated utility of ctDNA in managing cancer, especially in the realms of MRD monitoring and therapy selection in advanced disease. For researchers, scientists, and drug developers, the focus is now shifting from validating ctDNA as a prognostic tool to designing and executing prospective interventional trials that definitively prove its ability to improve patient outcomes. Overcoming challenges related to sensitivity in early detection, standardization, and integration with effective therapies will be the key to fully realizing the potential of this transformative technology in precision oncology.

Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) refers to fragmented, tumor-derived DNA circulating in the bloodstream, representing a subset of cell-free DNA (cfDNA). Liquid biopsy is the minimally invasive technique that analyzes ctDNA from blood samples to provide real-time molecular information about a patient's cancer. This paradigm has emerged as a transformative alternative to traditional tissue biopsies, offering a dynamic window into tumor biology through a simple blood draw. The fundamental distinction lies in ctDNA's origin from apoptotic or necrotic tumor cells, carrying the same genetic alterations as the tumor tissue from which it was shed.

The clinical and research relevance of ctDNA stems from its ability to overcome critical limitations inherent to traditional tissue sampling. Tissue biopsies provide a static, geographically limited snapshot of tumor heterogeneity, are invasive with associated procedural risks, and cannot be frequently repeated for monitoring purposes. In contrast, ctDNA captures contributions from all tumor sites, including primary and metastatic lesions, providing a more comprehensive representation of the tumor's genetic landscape. This capability for frequent serial monitoring enables researchers and clinicians to track molecular evolution, treatment response, and resistance mechanisms in real time, establishing ctDNA as a cornerstone of modern precision oncology.

Technical Advantages of ctDNA Analysis

Comprehensive Assessment of Tumor Heterogeneity

Traditional tissue biopsies are limited by tumor spatial heterogeneity. A single biopsy may not capture the complete genomic landscape of a tumor, especially in cancers with significant regional genetic variation or multiple metastatic sites. ctDNA, however, is released into the bloodstream from tumor cells throughout the body, effectively providing a composite molecular profile. Studies have demonstrated that ctDNA analysis can detect mutations present in different tumor regions that are missed by a single tissue biopsy [5] [16]. This is critically important for understanding the full spectrum of therapeutic targets and resistance mechanisms.

Dynamic and Real-Time Monitoring Capability

The short half-life of ctDNA, estimated between 16 minutes and several hours, makes it an exceptionally dynamic biomarker [4]. Changes in tumor burden or cell death in response to therapy are rapidly reflected in ctDNA levels, allowing for near real-time assessment of treatment efficacy. This enables researchers to:

- Monitor treatment response much earlier than radiographic imaging, often within days or weeks of treatment initiation [5] [17].

- Detect the emergence of resistance by identifying new molecular alterations (e.g., resistance mutations like EGFR T790M in NSCLC) weeks or months before clinical progression is evident [5] [4].

- Guide adaptive therapy, allowing for treatment modifications based on molecular response rather than waiting for anatomical changes.

Superior Sensitivity for Minimal Residual Disease (MRD)

The detection of Minimal Residual Disease (MRD)—the presence of microscopic tumor cells after curative-intent therapy—is a paramount challenge in oncology. Traditional imaging lacks the sensitivity to detect MRD, leading to late diagnosis of relapse. Ultrasensitive ctDNA assays can identify MRD at variant allele frequencies (VAF) as low as 0.001%, predicting recurrence many months before it becomes clinically or radiographically apparent [5] [18]. In diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), for example, a positive ctDNA test at the end of treatment is a powerful predictor of relapse, even when PET scans are negative [18].

Practical and Logistical Benefits

From a practical standpoint, liquid biopsy offers significant advantages:

- Minimally Invasive: A standard blood draw poses minimal risk and discomfort compared to surgical or core needle biopsies, improving patient compliance for serial sampling [4] [17].

- Rapid Turnaround Time: Some platforms, like digital PCR and electrochemical sensors, can provide results within hours, facilitating quicker clinical decision-making [5].

- Overcoming Tissue Limitations: ctDNA analysis is viable when tissue is insufficient, unavailable, or when a biopsy is medically contraindicated [19] [16].

Table 1: Core Advantages of ctDNA over Traditional Tissue Biopsies

| Feature | Traditional Tissue Biopsy | ctDNA Liquid Biopsy |

|---|---|---|

| Invasiveness | High (surgical/surgical) | Low (blood draw) |

| Spatial Representation | Limited to sampled site | Composite, systemic |

| Temporal Resolution | Static, single time point | Dynamic, enables serial monitoring |

| Turnaround Time | Days to weeks | Hours to days |

| Sensitivity for MRD | Very low | Very high (down to 0.001% VAF) |

| Ability to Capture Heterogeneity | Low | High |

| Feasibility for Serial Sampling | Low | High |

Advanced Detection Technologies and Methodologies

The accurate detection of ctDNA is technically challenging due to its low abundance in a high background of wild-type cfDNA, especially in early-stage disease or MRD settings. This has driven the development of highly sensitive and specific analytical platforms.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Approaches

NGS-based methods allow for broad profiling of multiple genomic alterations across many genes.

- Hybrid-Capture Methods: Techniques like CAPP-Seq (Cancer Personalized Profiling by deep Sequencing) use biotinylated oligonucleotide probes to enrich for genomic regions of interest before sequencing. This allows for sensitive detection of mutations, indels, and structural variants across hundreds of kilobases [4].

- Phased Variant Enrichment: Methods like PhasED-Seq (Phased Variant Enrichment and Detection Sequencing) significantly improve sensitivity by targeting multiple mutations occurring on the same DNA molecule (phased variants), making them easier to distinguish from background sequencing errors [5].

- Error-Corrected Sequencing: To overcome PCR and sequencing errors, techniques employ Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs). Each original DNA molecule is tagged with a unique barcode before amplification. Bioinformatic consensus building allows for the filtering of errors that are not present in the original molecule. Duplex Sequencing further improves accuracy by sequencing both strands of the DNA duplex and requiring mutations to be present on both strands [4].

Table 2: Key NGS-Based ctDNA Detection Technologies

| Technology | Core Principle | Key Advantage | Reported Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAPP-Seq [4] | Hybrid-capture with bioinformatic suppression | Broad, personalized profiling of mutations and SVs | ~0.01% VAF |

| PhasED-Seq [5] | Detection of multiple mutations on a single DNA fragment | Ultra-sensitive detection for low-concentration ctDNA | Parts-per-million level |

| TEC-Seq [4] | Targeted error correction with deep sequencing | High-depth, multi-gene panel with error suppression | ~0.01% VAF |

| Safe-SeqS [4] | Assignment of UMIs to each original DNA molecule | Distinguishes true mutations from PCR/sequencing errors | High (specific % not stated) |

| Duplex Sequencing [4] | Sequencing both strands of DNA duplex for error correction | Extremely high accuracy; considered a gold standard | 1000-fold higher accuracy than NGS |

PCR-Based and Other Ultrasensitive Platforms

For applications requiring rapid, highly sensitive detection of a limited set of known mutations, non-NGS platforms are highly effective.

- Droplet Digital PCR (ddPCR): The sample is partitioned into thousands of nanoliter-sized droplets, and PCR is performed in each droplet individually. This allows for absolute quantification of mutant alleles with high sensitivity and specificity without the need for standard curves. It is prized for its rapid turnaround and cost-effectiveness for serial monitoring [4] [17].

- Beads, Emulsion, Amplification, and Magnetics (BEAMing): This technique combines ddPCR with flow cytometry. DNA templates are bound to magnetic beads and amplified within emulsion droplets, followed by fluorescent hybridization and detection via flow cytometry, enabling highly sensitive detection [4].

- Electrochemical Biosensors: Emerging platforms use nanomaterials (e.g., magnetic nanoparticles with gold coatings, graphene) to capture ctDNA. Binding events are transduced into measurable electrical signals (e.g., changes in impedance), achieving attomolar sensitivity within minutes, showing great promise for point-of-care applications [5].

Specialized Library Preparation and Bioinformatic Techniques

- Fragment Size Selection: ctDNA fragments are typically shorter (90-150 bp) than non-tumor cfDNA. Library preparation methods that intentionally enrich for these shorter fragments can significantly increase the tumor fraction in the sequencing library, thereby improving the detection of low-frequency variants [5].

- Methylation Analysis: Analyzing the ctDNA methylome provides an orthogonal layer of tumor-specific information. Tumor cells exhibit distinct hypermethylation and hypomethylation patterns in promoter regions, which can be used for cancer detection, classification, and monitoring [5] [16].

- Bioinformatic Error Suppression: Proprietary algorithms, such as the High-Quality unique Sequence (HQS) technology used in the AlphaLiquid100 assay, leverage context-specific background error models and advanced UMI handling to further enhance variant calling accuracy and specificity [19].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for NGS-based ctDNA analysis, highlighting key steps from sample collection to data interpretation.

Key Experimental Protocols in ctDNA Research

Protocol for Longitudinal MRD Monitoring

Objective: To detect Minimal Residual Disease and predict relapse after curative-intent therapy in colorectal cancer.

Methodology:

- Pre-Treatment Baseline: Perform whole-exome or deep-panel sequencing of the primary tumor tissue to identify patient-specific somatic mutations (single nucleotide variants, insertions/deletions, and/or structural variants).

- Assay Design: Create a personalized, tumor-informed multiplex PCR or hybrid-capture panel targeting 16-50 identified clonal mutations.

- Blood Collection and Processing: Collect peripheral blood in cfDNA-stabilizing tubes (e.g., Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT). Within 4-6 hours, centrifuge at 1600 ×g for 15 minutes to separate plasma. Perform a second centrifugation at 16,000 ×g for 10 minutes to remove residual cells. Extract cfDNA from 2-4 mL of plasma using a commercial kit (e.g., Maxwell RSC cfDNA Plasma Kit).

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Construct sequencing libraries with the addition of Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) to each original DNA fragment. Enrich for target regions using the custom panel. Sequence on a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) to a minimum depth of 50,000x.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Process raw data through a pipeline including: demultiplexing, alignment to reference genome (GRCh38), UMI family consensus building to generate error-corrected reads, and variant calling. The assay's limit of detection is determined using synthetic controls, typically aiming for a VAF sensitivity of 0.01% or lower.

- Longitudinal Sampling and Analysis: Schedule blood draws at defined time points: post-surgery (baseline), after adjuvant chemotherapy (End-of-Treatment), and every 3-6 months during surveillance. For each sample, calculate the mean variant allele frequency across all tracked mutations. A sample is classified as MRD-positive if ctDNA is detected above the assay's predefined significance threshold.

Application: This protocol has demonstrated in studies that ctDNA positivity at the end of treatment is highly predictive of recurrence, with a lead time of over 1 year compared to standard imaging [5] [4].

Protocol for Monitoring Targeted Therapy Response

Objective: To assess molecular response to Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors (TKIs) in advanced Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) with EGFR mutations.

Methodology:

- Baseline Genotyping: Identify an actionable driver mutation (e.g., EGFR L858R) in plasma ctDNA using a validated NGS panel (e.g., AlphaLiquid100) or ddPCR assay.

- Treatment Initiation: Begin therapy with a relevant TKI (e.g., Osimertinib).

- Serial Blood Collection: Collect blood at predefined intervals: pre-treatment (Day 0), early on-treatment (Week 3-4), and late on-treatment (Week 7-10). Use consistent collection and processing protocols as in 4.1.

- Quantitative ctDNA Analysis: For each time point, quantify the VAF of the EGFR L858R mutation using ddPCR for rapid, absolute quantification. Simultaneously, a broader NGS panel can be used to monitor for the emergence of resistance mutations (e.g., EGFR T790M, C797S).

- Define Molecular Response (MR): Apply predefined thresholds to categorize response:

- MR Deep Response: ≥90% decrease in mutant allele concentration from baseline.

- MR Clearance: ctDNA becomes undetectable.

- Correlation with Outcome: Correlate molecular response at the early (Week 3-4) and late (Week 7-10) time points with standard clinical endpoints such as Progression-Free Survival (PFS) and Overall Survival (OS).

Application: The ctMoniTR project aggregated data from multiple trials using this approach, establishing that early ctDNA clearance in TKI-treated NSCLC patients is strongly associated with superior PFS and OS, supporting its use as an early endpoint in clinical trials [20] [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful ctDNA analysis requires a suite of specialized reagents and tools to ensure sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for ctDNA Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| cfDNA Blood Collection Tubes | Stabilizes nucleated blood cells to prevent genomic DNA release, preserving the native cfDNA profile. | Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT, PAXgene Blood ccfDNA Tube |

| cfDNA Extraction Kits | Isolate and purify short-fragment cfDNA from plasma with high efficiency and low contamination. | Maxwell RSC cfDNA Plasma Kit (Promega), QIAamp Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen) |

| Library Prep Kits | Prepare sequencing libraries from low-input, fragmented cfDNA; often include UMI integration. | Kits from Illumina, Swift Biosciences, Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) |

| Target Enrichment Panels | Hybrid-capture or multiplex PCR panels to enrich for cancer-relevant genomic regions. | Custom tumor-informed panels (e.g., from Natera, Personalis); Fixed panels (e.g., Guardant360, FoundationOne Liquid CDx) |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences ligated to each DNA fragment to enable error correction. | Integrated into modern library prep kits. Critical for distinguishing true low-VAF variants from artifacts. |

| Positive Control Reference Materials | Synthetic or cell-line derived cfDNA spikes with known mutations at defined VAFs for assay validation and QC. | Seraseq ctDNA Mutation Mix (LGC Clinical Diagnostics), Horizon Multiplex I cfDNA Reference Standard |

| ddPCR/Rare Mutation Assays | Probe-based assays for ultra-sensitive detection and absolute quantification of specific mutations. | Bio-Rad ddPCR Mutation Assays, Thermo Fisher Scientific QuantStudio Absolute Q Digital PCR Assays |

Clinical and Research Applications with Supporting Data

The utility of ctDNA spans the entire cancer care continuum, from diagnosis to advanced disease management. The following table summarizes key clinical applications supported by robust data.

Table 4: Clinical Applications and Validation Data for ctDNA

| Application | Cancer Type(s) | Key Supporting Data / Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|

| Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) & Recurrence | Colorectal, Breast, DLBCL [5] [18] | DLBCL: EOT ctDNA positivity: HR for progression=13.69 [18].CRC: ctDNA detects recurrence >1 year before imaging [5]. |

| Monitoring Targeted Therapy Response | NSCLC (EGFR-mutant) [19] [20] [17] | NSCLC: ctDNA clearance on TKIs associated with improved OS & PFS (Aggregate analysis of 8 trials) [17]. Assays detect VAF as low as 0.02% [19]. |

| Guiding Immunotherapy | NSCLC, Urothelial Cancer [20] [21] | Urothelial Cancer: On-treatment increase in ctDNA fraction associated with poorer response (18.7% vs 76.1%) and shorter PFS (2.8 vs 9.8 months) [21]. |

| Identifying Resistance Mechanisms | NSCLC, Breast Cancer [5] [4] | NSCLC: Detection of EGFR T790M resistance mutation in plasma allows for timely switch to 3rd-gen TKIs [5]. Breast Cancer: ESR1 mutations conferring resistance to aromatase inhibitors can be detected in ctDNA [4]. |

| Prognostic Stratification | DLBCL, various solid tumors [5] [18] | DLBCL: High baseline ctDNA concentration associated with increased risk of progression (HR: 2.50) and worse OS (HR: 2.67) [18]. |

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its promise, the widespread clinical adoption of ctDNA analysis faces several hurdles. Pre-analytical variability in blood collection, processing, and storage can significantly impact results, necessitating standardized protocols [5] [17]. Analytical variability exists between different technology platforms, making it difficult to compare results across studies or labs; efforts to harmonize and validate assays are ongoing [5] [19]. The high cost of advanced technologies like NGS and digital PCR can limit access, particularly in resource-limited settings [22]. Biological confounders like Clonal Hematopoiesis of Indeterminate Potential (CHIP), where blood cells acquire mutations unrelated to the cancer, can lead to false-positive results if not properly accounted for bioinformatically [19] [16].

Future research is focused on overcoming these challenges and expanding applications. Key areas include:

- Standardization: Initiatives like the ctMoniTR project are working to define optimal time points and molecular response criteria for use in clinical trials [20] [17].

- Novel Technologies: Integration of CRISPR-based detection, microfluidic point-of-care devices, and AI-based error suppression methods aim to enhance sensitivity, speed, and accessibility [5].

- Multi-Modal Liquid Biopsies: Combining ctDNA with other analytes like methylation patterns, fragmentomics (fragmentation patterns), and circulating tumor cells (CTCs) will provide a more comprehensive view of the tumor [5] [4] [23].

- Clinical Trial Endpoints: As evidence mounts, ctDNA-based metrics like Molecular Response and MRD detection are increasingly being validated as surrogate endpoints for accelerated drug approval [20] [17].

ctDNA analysis has unequivocally established itself as a dynamic, sensitive, and minimally invasive biomarker that surpasses traditional tissue biopsies in its ability to provide a comprehensive, real-time view of tumor dynamics. Its core advantages—capturing tumor heterogeneity, enabling serial monitoring, and detecting minimal residual disease with high sensitivity—are revolutionizing both clinical oncology and cancer research. As technologies continue to evolve towards even greater sensitivity and as the field moves towards standardized, validated protocols, ctDNA is poised to become an integral component of precision oncology, enabling more personalized, proactive, and effective cancer management.

Liquid biopsy represents a transformative approach in oncology, enabling the minimally invasive detection and analysis of tumor-derived components from bodily fluids such as blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid [24] [10]. This paradigm shift from traditional tissue biopsy addresses critical limitations including invasiveness, sampling constraints, and inability to serially monitor tumor evolution [24] [10]. As tumors continuously undergo evolutionary changes influenced by therapy and progression, liquid biopsy provides a dynamic window into tumor heterogeneity and clonal evolution [24]. The analytical focus of liquid biopsy centers on three principal categories of biomarkers: circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), circulating tumor cells (CTCs), and extracellular vesicles (EVs), each offering complementary biological information and clinical applications [25] [26]. This technical guide examines these key analytes within the broader context of advancing cancer detection research, with particular emphasis on their roles in precision medicine, treatment monitoring, and the identification of therapeutic resistance markers [24].

The clinical adoption of liquid biopsy has accelerated rapidly, with recent annual meetings of prominent oncology organizations like the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) and American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) dedicating significant sessions to liquid biopsy research, highlighting its expanding role across the cancer care continuum [27] [28]. This review provides an in-depth technical comparison of ctDNA, CTCs, and EVs, summarizing their distinct characteristics, detection methodologies, and applications to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate analytical approaches for specific research objectives.

Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA): Biology, Detection, and Applications

Biological Characteristics and Origin

Circulating tumor DNA comprises fragmented DNA molecules released into the bloodstream through processes including apoptosis, necrosis, and active secretion by tumor cells [10]. These fragments typically range from 160 to 200 base pairs in length and represent a subset of total cell-free DNA (cfDNA), with ctDNA proportion (tumor fraction) varying from 0.01% to 90% depending on tumor burden and cancer type [29]. A critical advantage of ctDNA is its short half-life of approximately 15 minutes to 2.5 hours, which enables real-time monitoring of tumor dynamics and treatment response [29]. Compared to protein biomarkers that may persist for weeks, this transient nature allows for nearly contemporaneous assessment of tumor status [29].

ctDNA carries the complete mutational signature of tumors, including point mutations, copy number alterations, gene fusions, and epigenetic modifications such as DNA methylation patterns [24] [10]. The fragmentomic pattern of ctDNA—its size distribution and fragmentation characteristics—also provides distinctive information that can differentiate cancer patients from healthy individuals, with recent studies demonstrating that ctDNA fragments in cancer patients are typically shorter than non-tumor cfDNA fragments [10].

Detection Methodologies and Platforms

The detection of ctDNA requires highly sensitive technologies capable of identifying rare mutant alleles against a background of wild-type DNA. Current methodologies primarily leverage PCR-based and next-generation sequencing (NGS) approaches, each with distinct advantages for specific applications.

Table 1: Key Platforms for ctDNA Detection and Analysis

| Platform/Assay | Technology Base | Key Features | Detectable Alterations | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guardant360 CDx [29] | NGS | Analyzes over 800 genomic targets; 15 Mb epigenomic targets | SNVs, indels, CNVs, fusions, methylation | Therapy selection, treatment monitoring, resistance detection |

| FoundationOne Liquid CDx [29] | NGS | Comprehensive genomic profiling of ctDNA | SNVs, indels, CNVs, rearrangements | Personalized treatment decisions, resistance monitoring |

| Signatera [29] | PCR/NGS | Patient-specific custom assay | Tumor-informed mutations | MRD detection, recurrence monitoring |

| UltraSEEK Lung Panel [26] | MassARRAY System | Multiplex PCR followed by single base extension | 74 hot-spot mutations in 5 NSCLC genes | Targeted mutation detection in lung cancer |

| MUTE-Seq [27] | CRISPR-Cas9 enriched NGS | Engineered FnCas9-AF2 variant selectively eliminates wild-type DNA | Low-frequency cancer-associated mutations | Ultrasensitive MRD detection |

| ddPCR [27] | PCR | Absolute quantification without standards | Known point mutations | MRD monitoring, especially in low TF samples |

For optimal ctDNA analysis, preanalytical steps are critical. The Liquid IQ panel assesses preanalytical parameters including long DNA templates from cell necrosis, white blood cell contamination, and amplifiable ctDNA copies to calculate optimal input amounts [26]. Ultrasensitive detection methods like MUTE-Seq (Mutation tagging by CRISPR-based Ultra-precise Targeted Elimination in Sequencing) have demonstrated significant improvements in detecting low-frequency cancer-associated mutant alleles, enabling more sensitive minimal residual disease (MRD) evaluation in non-small cell lung cancer and pancreatic cancer [27].

Research and Clinical Applications

ctDNA analysis has demonstrated substantial utility across multiple cancer management domains:

Early Cancer Detection and Screening: Multi-cancer early detection (MCED) platforms utilize ctDNA methylation patterns and fragmentomics to identify cancer signals and predict tissue of origin. Recent studies report specificities exceeding 98.5% with overall sensitivities around 59.7%, improving to 84.2% in late-stage tumors [27]. The Vanguard Study, part of the NCI Cancer Screening Research Network, confirmed the feasibility of implementing MCED tests in real-world settings across diverse populations [27].

Minimal Residual Disease (MRD) Monitoring: The high sensitivity of ctDNA detection enables identification of molecular residual disease following curative-intent treatment. In the VICTORI study on colorectal cancer, 87% of recurrences were preceded by ctDNA positivity, while no ctDNA-negative patients relapsed [27]. Similar findings have been reported across multiple cancer types, establishing ctDNA as a predictive biomarker for recurrence.

Treatment Response Monitoring and Resistance Identification: Dynamic changes in ctDNA levels and mutation profiles provide early indicators of treatment efficacy and emerging resistance mechanisms. Studies have demonstrated that ctDNA monitoring can predict treatment response weeks to months before radiographic imaging [27] [29].

Therapeutic Target Identification: ctDNA analysis identifies actionable mutations guiding treatment selection, such as EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer and PIK3CA mutations in breast cancer [10] [29]. The combination of tissue and liquid biopsy has been shown to increase detection of actionable alterations, leading to improved survival outcomes [27].

Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs): Biology, Detection, and Applications

Biological Characteristics and Origin

Circulating tumor cells are intact cancer cells that detach from primary tumors or metastatic deposits and enter the circulation, where they represent a fundamental mechanism of cancer dissemination [30] [25]. These cells are exceptionally rare, with approximately 1 CTC found per 1 million leukocytes in peripheral blood, creating significant technical challenges for their isolation and detection [30] [10]. Most CTCs undergo rapid apoptosis within 1-2.5 hours in circulation, though a small subset possesses the capacity to initiate metastatic colonies at distant sites [10].

CTCs exhibit considerable heterogeneity in size, morphology, molecular phenotype, and metastatic potential [25]. They can exist as single cells or clusters, with the latter demonstrating enhanced metastatic potential [30]. The molecular characterization of CTCs has revealed substantial plasticity, including epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) states that may facilitate intravasation and extravasation [30] [25]. Unlike ctDNA, which provides a snapshot of tumor genetics, CTCs represent a more comprehensive biological entity containing DNA, RNA, proteins, and functional capabilities that can be investigated through in vitro culture and functional assays [25].

Detection Methodologies and Platforms

CTC isolation and detection strategies leverage both physical properties (size, density, deformability) and biological characteristics (surface protein expression) to overcome the challenge of extreme rarity in blood samples.

Table 2: Comparison of Major CTC Detection Technologies

| Technology | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Capture Efficiency/Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CellSearch System [25] [29] [26] | Immunomagnetic separation targeting EpCAM | FDA-approved, standardized, high specificity | Limited to EpCAM-positive CTCs, may miss heterogeneous populations | Standardized for metastatic breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer |

| Parsortix PC1 System [29] | Microfluidic size-based separation | Label-free, preserves cell viability, enables downstream molecular analysis | Potential loss of smaller CTCs | Captures broader CTC phenotypes including EpCAM-low cells |

| Microfluidic CTC-iChip [30] | Integrated inertial focusing & immunomagnetic separation | High throughput, combines multiple separation principles | Complex design, higher cost | High purity and viability maintained |

| IsoFlux [30] | Immunomagnetic capture with flow control | High sensitivity, compatible with downstream analysis | Limited to antigen-positive cells | Efficient isolation for molecular characterization |

| DEPArray [30] | Dielectrophoretic cell manipulation | Enables single-cell isolation, high purity | Low throughput, complex operation | 100%-pure CTC clusters isolated |

| 3D Printed CTC Chip [30] | Microfluidic immunoaffinity capture | Enhanced surface area, customizable design | Requires specific antibodies | 87-92% capture efficiency for various cancer cell lines |

Recent advancements in CTC detection have incorporated machine learning algorithms to improve identification and classification. ML-powered image analysis automates CTC enumeration, reducing human error and enhancing reproducibility [30]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) can learn distinctive features of CTCs autonomously, improving classification accuracy particularly for rare and heterogeneous cell populations [30].

Research and Clinical Applications

CTCs provide unique insights into cancer biology and clinical management:

Prognostic Stratification: Numerous studies have established that CTC enumeration provides independent prognostic information. In metastatic breast, prostate, and colorectal cancers, elevated CTC counts correlate with reduced progression-free and overall survival [10] [29]. The CellSearch system received FDA clearance for prognostic use in these malignancies based on robust clinical validation [29].

Treatment Response Monitoring: Dynamic changes in CTC counts during therapy provide early indicators of treatment efficacy. Studies have demonstrated that persistent CTC detection during therapy predicts poor response and earlier progression [29].

Molecular Characterization and Biomarker Discovery: Comprehensive analysis of CTCs at the genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic levels reveals heterogeneity and identifies potentially targetable alterations. In metastatic prostate cancer, morphological evaluation of chromosomal instability in CTCs (CTC-CIN) has predicted taxane resistance and treatment benefit [27].

Understanding Metastatic Biology: Functional studies of CTCs, including in vitro culture and patient-derived xenograft models, provide insights into the metastatic cascade and mechanisms of treatment resistance [25]. The detection of CTC clusters has been associated with enhanced metastatic potential and worse clinical outcomes [30].

Extracellular Vesicles (EVs): Biology, Detection, and Applications

Biological Characteristics and Origin

Extracellular vesicles are lipid bilayer-enclosed nanoparticles released by virtually all cell types, including cancer cells, through multiple biogenesis pathways [31] [32]. Tumors actively secrete EVs, which participate in intercellular communication within the tumor microenvironment and systemically [25] [31]. EVs are categorized based on size and biogenesis mechanism: exosomes (30-150 nm) originate from multivesicular bodies, microvesicles (100-1000 nm) bud directly from the plasma membrane, and apoptotic bodies (1-5 μm) are released during programmed cell death [31].

The molecular cargo of tumor-derived EVs mirrors the composition of parent cells, containing proteins, lipids, DNA, mRNA, microRNA, long non-coding RNA, and metabolites [25] [32]. This cargo is protected from degradation by the lipid bilayer, enhancing stability in circulation compared to non-vesicular biomarkers [32]. EVs play functional roles in cancer progression by facilitating primary tumor growth, immune suppression, angiogenesis, preparation of metastatic niches, and drug resistance [25] [31].

Detection Methodologies and Platforms

EV isolation and analysis present technical challenges due to their nanoscale size and heterogeneity. Current approaches exploit physical properties and surface characteristics for separation:

Ultracentrifugation: The most widely used method, involving sequential centrifugation steps at increasing forces (up to 100,000-200,000 × g) to pellet EVs based on density and size. Differential, isopycnic, and moving zone ultracentrifugation techniques can reduce EV loss and improve purity [24].

Precipitation-Based Methods: Chemical polymers (e.g., polyethylene glycol) or commercial kits (e.g., Total Exosome Precipitation Reagent) that reduce EV solubility and facilitate low-speed pelleting [26] [32].

Size-Based Chromatography and Filtration: Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) separates EVs from smaller contaminants based on hydrodynamic radius, while nanomembrane ultrafiltration concentrators offer a promising approach for gentle EV concentration [24].

Immunoaffinity Capture: Antibodies against EV surface proteins (e.g., CD9, CD63, CD81, tumor-specific antigens) enable selective isolation of subpopulations. Microfluidic devices with antibody-functionalized surfaces enhance capture efficiency [30] [31].

Microfluidic Technologies: Lab-on-a-chip devices that integrate multiple separation principles (immunoaffinity, size, acoustic, electrophoretic) for high-purity EV isolation with minimal sample requirements [30] [32].

Analytical approaches for EV characterization include nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), tunable resistive pulse sensing (TRPS), flow cytometry, transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and Western blot for size distribution, concentration, and marker validation [31]. Molecular profiling of EV cargo employs proteomics, transcriptomics, lipidomics, and metabolomics to identify disease-specific signatures [32].

Research and Clinical Applications

EV-based liquid biopsy applications are rapidly expanding:

Early Cancer Detection: EV biomarkers show promise for early cancer identification. In liver cancer, EV-based analyses distinguished cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma from healthy states with high accuracy (AUC=0.92) [27]. Proteomic analyses of EVs have identified specific protein signatures associated with cancer risk [27].

Prognostic Stratification: EV characteristics correlate with clinical outcomes. In metastatic non-small cell lung cancer, high concentrations of PD-L1-positive small EVs were significantly correlated with overall survival, and when combined with CTC detection, identified patients with particularly poor prognosis [26]. In neuroblastoma, EV concentration and nucleolin expression were elevated in high-risk patients, suggesting utility for risk stratification [27].

Therapy Response Prediction: EV biomarkers may predict treatment efficacy and toxicity. In trastuzumab deruxtecan-treated patients, elevated inflammatory proteins in EVs (notably CXCL11) were associated with impending interstitial lung disease/pneumonitis [27].

Mechanistic Insights into Cancer Biology: EV analysis provides windows into tumor-stroma interactions, immune modulation, and metabolic reprogramming in the tumor microenvironment [31] [32].

Advanced computational approaches like the MWENA (Meta-Weight Elastic Net Algorithm) address challenges in EV omics data analysis, including high dimensionality, small sample sizes, and class imbalance, improving classification performance for disease diagnosis, staging, and subtyping [32].

Comparative Analysis and Integrative Approaches

Technical and Biological Comparison

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of Key Liquid Biopsy Analytes

| Parameter | ctDNA | CTCs | Extracellular Vesicles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Nature | Cell-free nucleic acids | Intact tumor cells | Lipid bilayer-enclosed particles |

| Size Range | 160-200 bp (fragments) | 10-30 μm (cells) | 30-1000 nm (vesicles) |

| Abundance in Blood | 0.1-10% of total cfDNA | 1-10 cells per 10 mL blood | 10^8-10^12 particles per mL |

| Half-Life | 15 min - 2.5 hours | 1-2.5 hours | Hours to days |

| Cargo Information | Genetic & epigenetic alterations | Whole genome, transcriptome, proteome, functional properties | Proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, metabolites |

| Sensitivity Challenges | Low tumor fraction, clonal hematopoiesis | Extreme rarity, heterogeneity | Heterogeneity, non-tumor background |

| Key Isolation Methods | Silica membrane columns, magnetic beads | Immunomagnetic, microfluidic, filtration | Ultracentrifugation, precipitation, size exclusion |

| Primary Analysis Platforms | ddPCR, NGS, MassARRAY | CellSearch, Parsortix, microfluidics | NTA, TEM, flow cytometry, omics |

| Clinical Applications | MRD, treatment monitoring, target identification | Prognosis, treatment monitoring, metastasis research | Early detection, prognosis, mechanism studies |

| Regulatory Status | FDA-approved for EGFR in NSCLC | FDA-approved for prognosis in breast, prostate, colorectal cancer | Research use, early commercial development |

Integrated Multi-Analyte Approaches

Emerging evidence suggests that combining multiple liquid biopsy analytes provides complementary information that enhances clinical utility. In metastatic NSCLC, the combination of CTC detection and high PD-L1-positive sEV concentration identified patients with significantly worse prognosis (HR=7.65, 95% CI=3.11-18.83, P<0.001) compared to either analyte alone [26]. Similarly, studies have demonstrated that combining EV RNA analysis with ctDNA mutation detection increases the sensitivity for identifying EGFR mutations in plasma samples from NSCLC patients [26].

The ROME trial exploratory analysis revealed that despite only 49% concordance between tissue and liquid biopsies in detecting actionable alterations, combining both modalities significantly increased overall detection of actionable alterations and led to improved survival outcomes in patients receiving tailored therapy [27]. This highlights the importance of integrated approaches in precision oncology.

Multi-analyte liquid biopsy panels that simultaneously interrogate ctDNA mutations, CTC phenotypes, and EV cargo may provide a more comprehensive assessment of tumor burden, heterogeneity, and evolving molecular characteristics throughout the disease course and treatment continuum.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Liquid Biopsy Applications

| Category | Specific Product/Platform | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes | CellSave Preservative Tubes [26] | Stabilizes CTCs for up to 96 hours | Required for CellSearch system |

| Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT [29] | Stabilizes nucleated blood cells and cfDNA | Prevents dilution from white blood cell lysis | |

| Nucleic Acid Extraction | Circulating Nucleic Acid Kit (Qiagen) [26] | Isolation of ctDNA from plasma | Maintains fragment integrity |

| CTC Enrichment | CellSearch CTC Kit [26] | Immunomagnetic CTC enrichment | FDA-approved for prognostic use |

| Parsortix PC1 System [29] | Size-based microfluidic CTC capture | Enables downstream molecular analysis | |

| ctDNA Analysis | Guardant360 CDx [29] | Comprehensive ctDNA NGS panel | FDA-approved for therapy selection |

| FoundationOne Liquid CDx [29] | ctDNA-based genomic profiling | Identifies FDA-approved biomarkers | |

| Signatera [29] | Tumor-informed MRD assay | Customized for individual patients | |

| EV Isolation | Total Exosome Precipitation Reagent [26] | Chemical precipitation of EVs | Compatible with downstream analyses |

| Detection Reagents | Liquid IQ Panel [26] | Preanalytical ctDNA quality control | Assesses amplifiable ctDNA copies |

| UltraSEEK Lung Panel [26] | Multiplex mutation detection | MassARRAY-based platform | |

| Analysis Software | MWENA Algorithm [32] | EV omics data classification | Handles high-dimensional, imbalanced data |

The comparative analysis of ctDNA, CTCs, and extracellular vesicles reveals distinct advantages and limitations for each class of biomarker, highlighting their complementary roles in cancer detection and monitoring. ctDNA offers superior sensitivity for detecting genetic alterations and monitoring minimal residual disease, with relatively straightforward analytical workflows and growing regulatory acceptance. CTCs provide unique insights into metastatic biology and tumor heterogeneity, with functional capabilities that enable deeper investigation of mechanisms underlying cancer dissemination and treatment resistance. Extracellular vesicles offer stable, information-rich packages of tumor-derived molecules, with emerging applications in early detection and unique windows into tumor-stroma interactions.

Future directions in liquid biopsy research will likely focus on standardizing preanalytical protocols, enhancing sensitivity for early detection applications, developing multi-analyte integration algorithms, and validating clinical utility in prospective interventional trials. The rapid pace of technological innovation, particularly in microfluidics, single-cell analysis, and computational methods, continues to expand the potential applications of liquid biopsy across the cancer care continuum. As these technologies mature and validation evidence accumulates, liquid biopsy is poised to transform cancer management through increasingly precise, dynamic, and minimally invasive assessment of tumor biology.

Cutting-Edge Technologies and Clinical Applications in Oncology

The analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in liquid biopsies has become a cornerstone of modern precision oncology, enabling non-invasive genomic profiling to guide cancer diagnosis, treatment selection, and disease monitoring [33] [34]. Two technological platforms form the foundational pillars of this field: Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR)-based assays. NGS provides comprehensive, hypothesis-free genomic analysis capable of detecting multiple variant types across hundreds of genes simultaneously, while PCR-based methods offer exceptional sensitivity for detecting specific, known mutations with minimal input DNA requirements [35] [36]. The complementary strengths of these platforms address the fundamental challenges of liquid biopsy analysis, where ctDNA often represents a tiny fraction (<0.1% to >10%) of the total cell-free DNA in circulation [34]. This technical guide examines the principles, methodologies, and applications of both NGS and PCR platforms within the context of ctDNA analysis, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the experimental protocols and technical specifications essential for implementing these technologies in cancer research.

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Technology

Fundamental Principles and Platform Comparisons

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) represents a paradigm shift from first-generation Sanger sequencing, employing massively parallel sequencing to simultaneously decode millions to billions of DNA fragments [35] [37]. This high-throughput approach has reduced the cost of sequencing a human genome from billions of dollars to under $1,000 and decreased processing time from years to hours [37]. The core principle underlying NGS involves fragmenting DNA samples, attaching oligonucleotide adapters, and performing sequential cycles of nucleotide incorporation and detection across millions of clusters in a flow cell [35]. The most prevalent method, Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS) utilized by Illumina platforms, employs fluorescently-labeled reversible terminator nucleotides that are imaged after each incorporation cycle to determine sequence identity [35] [38].

Table 1: Comparison of Major NGS Platform Technologies

| Platform/Technology | Sequencing Principle | Read Length | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations | Common Applications in Liquid Biopsy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina SBS | Sequencing by Synthesis with reversible dye-terminators | Short-read (50-300 bp) | High accuracy (>99.9%), low cost per base | Short reads struggle with repetitive regions | Targeted panels, whole exome, whole genome sequencing [35] |

| Ion Torrent | Semiconductor sequencing detecting H+ ions | Short-read (200-400 bp) | Fast run times, no optical detection | Homopolymer error rates | Targeted gene panels, tumor sequencing [35] |

| PacBio SMRT | Single Molecule Real-Time sequencing | Long-read (10,000-25,000 bp average) | Extremely long reads, detects epigenetics | Higher cost, lower throughput | Structural variant detection, complex rearrangement analysis [35] |

| Oxford Nanopore | Nanopore electrical signal detection | Long-read (10,000-30,000 bp average) | Real-time sequencing, portability | Higher error rate (~15%) | Metagenomics, structural variants, transcriptomics [35] |

The selection of appropriate NGS platforms depends on research objectives, with short-read technologies (Illumina, Ion Torrent) dominating clinical applications requiring high accuracy for single nucleotide variant detection, while long-read platforms (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) address challenges in characterizing structural variants, complex genomic regions, and epigenetic modifications [35] [37].

Key NGS Applications in Liquid Biopsy and ctDNA Analysis

In liquid biopsy applications, NGS enables comprehensive genomic profiling of ctDNA through several targeted approaches:

Targeted Gene Panels: Focused panels (e.g., 50-500 genes) provide deep sequencing coverage (500-10,000x) to detect low-frequency variants with variant allele frequencies (VAF) as low as 0.1-0.5% in ctDNA [33] [34]. These panels optimize cost-effectiveness while maintaining sensitivity for clinically actionable mutations in cancer-related genes.

Whole Exome Sequencing (WES): Captures coding regions of ~20,000 genes, providing broad coverage of protein-altering variants without the cost of whole genome sequencing. In liquid biopsy, WES enables hypothesis-free exploration of tumor evolution and heterogeneity [39].

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS): Provides complete genomic coverage, enabling detection of structural variants, copy number alterations, and genomic rearrangements across the entire genome, though with less sensitivity for low VAF variants in ctDNA due to distributed sequencing coverage [39].

The PAN100 panel exemplifies a hybridization capture-based NGS approach designed for liquid biopsy, targeting 101 genes with demonstrated ability to detect variants at 0.3% VAF with 73.1% positive percent agreement for single-nucleotide variants compared to tissue NGS [33]. Similarly, the Northstar Select assay demonstrates recent advancements with improved sensitivity (0.15% VAF for SNVs/indels) across 84 genes, addressing the challenge of low-shedding tumors through enhanced capture and bioinformatics methods [34].

Experimental Protocol: Hybridization Capture-Based NGS for ctDNA Analysis

The following protocol outlines the key steps for implementing hybridization capture-based NGS in liquid biopsy analysis, as validated in the PAN100 panel study [33]:

Step 1: Sample Collection and Plasma Processing

- Collect whole blood in cell-stabilization tubes (e.g., Streck Cell-Free DNA BCT) to prevent genomic DNA contamination and preserve ctDNA integrity.

- Process within 4-6 hours of collection: centrifuge at 1,600-2,000 × g for 10-20 minutes at 4°C to separate plasma from cellular components.

- Transfer plasma to microcentrifuge tubes and perform a second centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 minutes to remove residual cells.

- Store plasma at -80°C if not processing immediately.

Step 2: Cell-Free DNA Extraction

- Extract cell-free DNA from 4-10 mL plasma using silica membrane-based kits or magnetic bead systems specifically validated for low-abundance DNA recovery.