Integrating Radiomics and Digital Pathology: A New Paradigm for Precision Cancer Diagnostics and Drug Development

This article explores the transformative potential of integrating radiomics and digital pathology (pathomics) in oncology.

Integrating Radiomics and Digital Pathology: A New Paradigm for Precision Cancer Diagnostics and Drug Development

Abstract

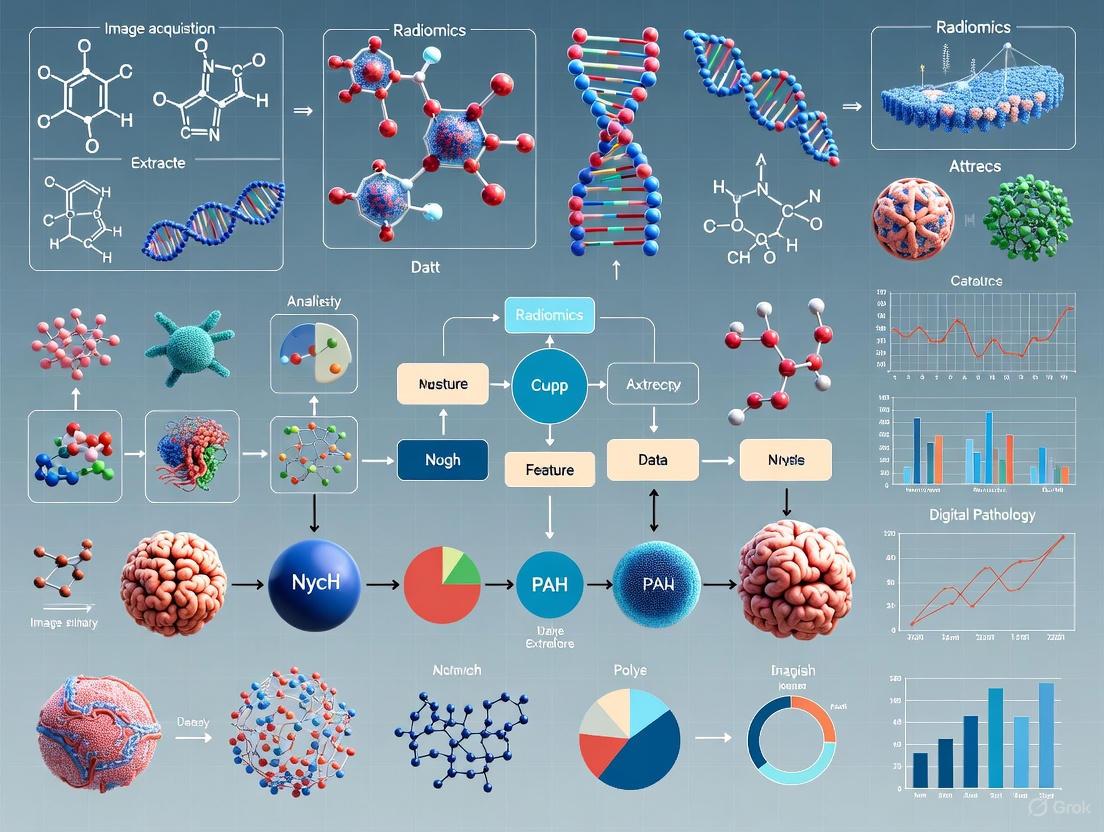

This article explores the transformative potential of integrating radiomics and digital pathology (pathomics) in oncology. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive overview of how these quantitative, AI-driven technologies are revolutionizing cancer diagnostics. We cover the foundational principles of radiomics and pathomics, detail the methodological pipelines for feature extraction and multi-omics fusion, and address key challenges in standardization and interpretability. The discussion extends to validation strategies and comparative performance analyses, highlighting how these tools enhance prognostic modeling, therapy response prediction, and biomarker discovery. By synthesizing the latest research and future directions, this article serves as a critical resource for advancing the development of robust, clinically translatable computational tools in precision oncology.

Demystifying Radiomics and Pathomics: Core Concepts and Value in Oncology

The field of oncology is undergoing a data-driven transformation, moving beyond qualitative visual assessment to the quantitative mining of medical images for prognostic and diagnostic insights. This paradigm shift is fueled by two complementary disciplines: radiomics and pathomics. Radiomics refers to the high-throughput extraction of quantitative features from radiological images, such as CT, MRI, or PET, converting images into mineable data that reveal sub-visual tissue heterogeneity [1] [2]. Pathomics applies the same principle to digitized histopathology slides, using advanced image analysis to "unlock" revealing sub-visual attributes about tumors from their morphology [3]. The core premise is that biomedical images contain information about disease-specific processes that are imperceptible to the human eye [1]. The integration of these image-based phenotypes with genomic data, known as genomics, offers a uniquely comprehensive portrait of a tumor's spatial and molecular characteristics, paving the way for more accurate assessment of disease aggressiveness in the era of precision oncology [3].

Field Definitions and Workflows

Radiomics: The Macroscopic Scale

Radiomics focuses on anatomic and functional characteristics at the macroscopic level, typically acquired through non-invasive procedures [3]. It quantifies underlying sub-visual tissue heterogeneity that is not always apparent to a human reader, allowing for the interrogation of disease regions and surrounding structures like the peri-tumoral region [3] [1]. The typical radiomics workflow involves several critical, sequential steps, as illustrated below and detailed in [1] and [2].

Pathomics: The Microscopic Scale

Pathomics, or quantitative histomorphometric analysis, is the process of extracting and mining computer-derived measurements from digitized histopathology images [3]. While pathologists visually read histopathology slides for diagnosis, pathomics can discover complex histopathological phenotypes, characterizing the spatial arrangement of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and the interplay between different histological primitives [3]. This provides a comprehensive portrait of a tumor's morphologic heterogeneity from a standard hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) slide. The workflow for pathomics shares conceptual similarities with radiomics but operates on whole-slide images (WSIs) at a much higher resolution, focusing on cellular and sub-cellular features.

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

The Radiomics Pipeline: A Step-by-Step Technical Guide

Image Acquisition and Dataset Definition

A solid radiomics study begins with a clear goal and a well-defined patient population [2]. The three cardinal rules are ensuring sufficient sample size, achieving balanced representation across patient populations, and upholding data quality. To avoid overfitting, the sample size should be at least 50 times the number of prediction classes and/or at least 10 times the number of selected features [2]. Images should ideally come from the same modality and scanner, using a consistent and standardized acquisition protocol to minimize the variability of radiomic features [2].

Image Preprocessing

Preprocessing ensures dataset uniformity and is crucial for feature repeatability and reproducibility [2]. The main steps are:

- Resampling: Altering the spatial resolution to a uniform grid (e.g., 1x1x1 mm³) to mitigate differences from varying acquisitions [1] [2].

- Intensity Discretization: Grouping pixel intensity values into a fixed number of bins or using a fixed bin width. This is critical for data with arbitrary units, like MRI [1].

- Normalization and Filtering: For CT and PET data, "range re-segmentation" excludes pixels outside a specified range. For MRI, intensity outlier filtering (e.g., excluding values outside μ ± 3σ) is common [1].

Image Segmentation

Segmentation defines the region or volume of interest (ROI/VOI). This can be done manually, semi-automatically, or fully automatically using deep learning (e.g., U-Net) [1]. Manual and semi-automated methods are time-consuming and introduce observer bias; thus, assessments of intra- and inter-observer reproducibility are essential. Automated segmentation is ideal but requires robust, generalizable algorithms [1].

Feature Extraction and Selection

Feature extraction quantifies the ROI/VOI using advanced mathematical analysis. The open-source pyRadiomics package in Python is commonly used and can extract a vast number of features [1]. These are often categorized into:

- First-Order Statistics: Describe the distribution of voxel intensities (e.g., entropy, kurtosis).

- Shape-based Features: Describe the 3D geometry of the ROI.

- Texture Features: Describe the spatial patterns of voxel intensities, often calculated from matrices like the Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) [1] [2]. Given the high dimensionality, feature selection is critical. Methods like the minimum redundancy maximum relevance (mRMR) algorithm select the most relevant features for the subsequent model building [2].

AI Model Building and Validation

The selected features are used to train machine learning models (e.g., Random Forest) for diagnostic, prognostic, or predictive tasks [2]. The dataset should be split (e.g., 70-20-10% for train-test-validation), and metrics like accuracy, F1-score, and AUC should be used for evaluation [2].

Table 1: Example Radiomics Study Workflow for Liver HCC Detection [2]

| Step | Key Question | Management in Example Study |

|---|---|---|

| Dataset Definition | Is there a sufficient sample size? | 104 patients with chronic liver disease (54 with HCC, 50 without) |

| Image Acquisition | What is the imaging modality? | 1.5 T liver MR scan with a standardized protocol |

| Image Preprocessing | Is resampling applied? | Resampling to 1x1x1 mm³ isotropic voxels |

| Segmentation | How is it performed? | Semi-automatic 3D segmentation by two radiologists in consensus |

| Feature Extraction | Which classes are extracted? | All feature classes from original and filtered images via pyRadiomics |

| Feature Selection | How is it performed? | mRMR algorithm to select 10 most relevant features from 1070 extracted |

| AI Model | Which model is chosen? | Random Forest (100 trees) with 70-20-10% train-test-validation split |

Pathomics and Multi-Omics Integration

Pathomics workflows involve digitizing H&E-stained tissue slides and using machine learning to identify and characterize various cell types, such as cancer cells, lymphocytes, and stromal cells [3] [4]. A key research focus is correlating and fusing these pathomic features with other data modalities.

- Correlating Pathomics and Genomics: This involves establishing associations between tumor morphology and large-scale genomic data to understand the inferential relationship for biomarker discovery. Methods range from classical Pearson correlation to advanced sparse canonical correlation analysis (CCA), which can identify correlated sets of genes and histomorphometrics [3]. For instance, one study correlated cellular diversity features from non-small cell lung carcinomas with bulk RNA data, finding associations with apoptotic signaling pathways [3].

- Fusion of Pathomics and Radiomics: Integrating the macroscopic view from radiology with the microscopic detail from pathology provides a multi-scale perspective on the tumor. This fusion can help understand the biological basis of specific quantitative imaging features and resolve confounding effects of tissue heterogeneity [3].

The integration of these multi-modal data offers a unique opportunity to comprehensively interrogate the cancer microenvironment, enabling a more accurate assessment of disease aggressiveness [3]. The following diagram illustrates this integrated multi-omics approach.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Tools and Platforms for Radiomics and Pathomics Research

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Image Scanners | Hardware | Generates primary radiological or pathological images. | MRI, CT, PET scanners; Whole Slide Imaging (WSI) scanners for pathology. |

| Image Segmentation Software | Software | Delineates Regions/Volumes of Interest (ROIs/VOIs). | 3D Slicer [1], ITK-SNAP [1], MeVisLab [1]; Deep learning models (e.g., U-Net) [1]. |

| Radiomics Feature Extraction Platforms | Software/Code Library | Extracts quantitative features from medical images. | pyRadiomics (Python) [1], LifEx [1]. |

| AI/ML Modeling Frameworks | Software/Code Library | Builds and validates diagnostic/prognostic models. | Scikit-learn (Python) for Random Forest, SVM; PyTorch, TensorFlow for deep learning. |

| Digital Pathology Standards | Data Standard | Ensures interoperability and data consistency for WSIs. | DICOM Standard Supplement 145 for WSI [5]; alternative modular architectures are under debate [6]. |

| Liquid Biopsy & AI Analysis | Wet-bench / Algorithm | Detects circulating tumor cells from blood samples. | The "RED" (Rare Event Detection) AI algorithm automates cancer cell detection in liquid biopsies [7]. |

Critical Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its promise, the field faces several significant challenges. The reproducibility of radiomic features is highly sensitive to variations in imaging scanners, acquisition parameters, and preprocessing steps [1] [2]. Initiatives like the Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance (QIBA) aim to standardize these processes [2]. Furthermore, the transition to digital pathology is hampered by interoperability hurdles and a lack of standardization, though the adoption of the DICOM standard for WSI is a positive step [5] [6]. The high cost and regulatory complexity of validating advanced diagnostic systems also limit widespread adoption, especially in resource-limited settings [8].

Future directions are focused on overcoming these hurdles. There is a strong push towards more robust and automated AI-driven tools, such as the RED algorithm for liquid biopsies, which can find rare cancer cells without human bias [7]. The market for cancer diagnostics, projected to grow from USD 65.5 billion in 2025 to USD 148.2 billion by 2035, will be driven by innovations in multi-cancer early detection (MCED) tests, liquid biopsies, and the integration of AI [8]. Ultimately, the convergence of radiomics, pathomics, and genomics into a unified analytical framework holds the key to unlocking deeper insights into cancer biology and improving patient outcomes through precision medicine.

Radiomics is a rapidly evolving field in medical imaging, particularly within oncology, that aims to extract high-dimensional quantitative data from standard-of-care images [9]. It is founded on the hypothesis that medical images contain information that reflects underlying pathophysiology and tumor heterogeneity, which may not be perceptible through visual assessment alone [10]. By converting digital images into mineable data, radiomics provides a non-invasive method to characterize tumors, potentially assisting in diagnosis, prognosis prediction, and treatment response assessment [11]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive, step-by-step overview of the radiomics pipeline, framed within cancer diagnostics research for an audience of researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The Radiomics Workflow: A Step-by-Step Guide

The radiomics workflow consists of several sequential steps, each with its own methodologies and considerations. The following diagram illustrates the complete pipeline from image acquisition to final analysis.

Figure 1: Comprehensive Radiomics Pipeline Workflow. This diagram outlines the sequential steps in a standardized radiomics analysis, from initial image acquisition to final model application, including key methodological considerations at each stage.

Image Acquisition

The initial step in any radiomics study involves acquiring medical images using various imaging modalities. Each modality offers distinct advantages and captures different aspects of tumor biology [11].

Key Imaging Modalities:

- Computed Tomography (CT): Widely accessible, time-efficient, and cost-effective with highly reproducible radiomics features [11].

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Provides high soft-tissue contrast resolution without ionizing radiation, with functional sequences (DWI, DCE-MRI) capturing various functional states of tumors [11].

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET): Offers insight into functional and biochemical changes, though features can be influenced by variations in reconstruction parameters [11].

- Ultrasound (US): Enables real-time imaging but suffers from high operator variability, reducing reliability and reproducibility [11].

Critical Considerations: Radiomic features are highly sensitive to variations in imaging acquisition parameters, including scanner equipment, acquisition techniques, reconstruction parameters, and contrast administration [12] [2]. To ensure feature reproducibility and study quality, researchers should:

- Use consistent imaging protocols across all subjects [2]

- Minimize variations in external conditions that may influence acquisition [2]

- Report detailed acquisition parameters, including slice thickness and reconstruction kernel [12]

- Consider initiatives like the Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance (QIBA) for standardization [2]

Image Preprocessing

Preprocessing is essential to ensure dataset uniformity and consistency, thereby enhancing the robustness and reliability of subsequent analyses [2]. This step addresses variations introduced during image acquisition and prepares images for feature extraction.

Table 1: Essential Image Preprocessing Steps in Radiomics

| Step | Purpose | Common Parameters | Impact on Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resampling | Standardize spatial resolution; mitigate differences from acquisition devices/protocols | Establish uniform voxel grid (e.g., 1×1×1 mm³, 2×2×2 mm³) | Reduces variability due to different voxel sizes; improves comparability |

| Intensity Discretization (Binning) | Group pixel intensity values into intervals (bins) | Fixed bin width (e.g., 25) | Influences capture of small intensity variations; affects texture features |

| Normalization | Standardize intensity values across images | Various scaling methods (MinMax, standard, robust) | Ensures consistent intensity ranges; reduces scanner-specific biases |

The specific preprocessing approach should be tailored to the study objectives, anatomical structures under analysis, and imaging techniques employed [2]. For instance, the optimal resampling strategy for PET images (which may use larger voxel sizes for statistical reasons) differs from that for high-resolution CT studies examining subtle bone structures [2].

Image Segmentation

Segmentation involves delineating regions of interest (ROIs), typically tumors or other pathologies, from which radiomic features will be extracted. This critical step directly influences feature values and requires careful execution.

Segmentation Methods:

- Manual Segmentation: Performed by expert readers (e.g., radiologists), considered gold standard but time-consuming and subject to inter-observer variability [10] [12].

- Semi-automated Segmentation: Combines algorithmic approaches with human supervision, improving efficiency while maintaining accuracy [10] [2].

- Fully Automated Segmentation: Utilizes deep learning algorithms for complete automation, offering high reproducibility but requiring extensive training data [10] [13].

Best Practices: Current trends show increased reporting of human supervision in segmentation to ensure accuracy [12]. For 3D analysis, full volumetric segmentation is preferred over 2D approaches as it captures complete spatial information [2]. Researchers should clearly document segmentation methodology, including the software tools used and whether inter- or intra-observer variability was assessed [12].

Feature Extraction

Feature extraction involves computing quantitative, mathematically defined features from the segmented ROIs. These features aim to characterize tissue properties at multiple levels.

Table 2: Major Classes of Radiomic Features and Their Characteristics

| Feature Class | Description | Representative Features | Biological Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-Order Statistics | Describe distribution of voxel intensities without spatial relationships | Mean, median, minimum, maximum, variance, skewness, kurtosis, entropy [10] [14] | Overall tumor intensity patterns; simple heterogeneity measures |

| Shape-Based Features | Capture geometric properties of ROI in 2D or 3D | Volume, surface area, sphericity, elongation, flatness [10] | Tumor morphology and gross structural characteristics |

| Second-Order Texture Features | Quantify spatial relationships between voxel pairs | GLCM: Contrast, entropy, energy, homogeneity [10] [14] | Intra-tumor heterogeneity; spatial patterns of intensity variation |

| Higher-Order Texture Features | Capture complex patterns through filter applications or specialized matrices | GLRLM, GLSZM, NGTDM, GLDM [10] [14] | Fine-textured patterns, heterogeneity at multiple scales |

Feature extraction is typically performed using standardized software packages like PyRadiomics (Python-based) [10] or through in-house solutions developed in platforms such as Matlab [10]. The Image Biomarker Standardization Initiative has established guidelines to promote feature standardization across studies [14].

Feature Selection and Analysis

Following feature extraction, the typically large number of features (often hundreds per ROI) must be reduced to avoid overfitting and identify the most biologically relevant features.

Feature Selection Methods:

- Filter Methods: Select features based on statistical measures (e.g., correlation with outcome) [15]

- Wrapper Methods: Use machine learning model performance to select features (e.g., recursive feature elimination) [15]

- Embedded Methods: Incorporate feature selection during model training (e.g., LASSO, random forest importance) [15]

Dimensionality Reduction Techniques:

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

- Minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR) [15]

The "curse of dimensionality" is particularly relevant in radiomics, where the number of features often far exceeds the number of samples [10] [15]. To mitigate overfitting, studies should maintain appropriate sample-to-feature ratios, with recommendations suggesting at least 10 samples per feature [2].

Model Building and Validation

The final pipeline stage uses selected features to build predictive models for classification, prognosis, or treatment response prediction.

Common Machine Learning Classifiers:

- Logistic Regression (LR)

- Support Vector Machines (SVM)

- Random Forests (RF)

- k-Nearest Neighbors (KNNs)

- Naive Bayes (NB)

- Adaptive Boosting (AdaBoost)

- Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) [15]

Validation Strategies: Robust validation is essential for assessing model generalizability:

- Train-Test Splits: Multiple splits (e.g., 10 iterations) mitigate selection bias inherent in single splits [15]

- Cross-Validation: k-fold cross-validation (5-fold for <100 samples, 10-fold for larger datasets) [15]

- External Validation: Testing on completely independent datasets provides the strongest evidence of generalizability [16] [12]

Performance metrics such as area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) and accuracy are commonly used for evaluation [15]. More advanced frameworks like RadiomiX systematically test classifier and feature selection combinations across multiple validations to identify optimal model configurations [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Tools and Software for Radiomics Research

| Tool Category | Examples | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Segmentation Software | 3D Slicer, ITK-SNAP, VivoQuant, Matlab [10] | ROI delineation | Manual, semi-automated, and automated segmentation capabilities |

| Feature Extraction Platforms | PyRadiomics [10], Quantitative Image Feature Pipeline (QIFP) [17] | Calculate radiomic features from segmented ROIs | Standardized feature definitions; batch processing; multiple imaging modalities |

| Integrated Analysis Platforms | Orange, KNIME [17], RadiomiX [15] | End-to-end radiomics analysis | Feature selection, machine learning, visualization; workflow management |

| Data Sources | The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) [17], ePAD [17] | Access to annotated imaging datasets | Publicly available datasets; standardized formats; clinical annotations |

Methodological Considerations for Experimental Design

Dataset Definition and Sample Size

A solid radiomics study begins with a clear goal and well-defined patient population [2]. Key considerations include:

- Sample Size: Adequate samples are crucial to capture complex patterns and avoid overfitting. Recommended guidelines include at least 50 times the number of prediction classes and/or at least 10 times the number of selected features [2].

- Population Balance: Datasets should have comparable sample sizes across populations. For imbalanced datasets, undersampling or oversampling techniques can be applied, each with distinct advantages and limitations [2].

- Data Quality: Consistent protocols on the same equipment under standardized conditions are essential [2].

Reproducibility and Generalizability

Reproducibility remains a significant challenge in radiomics, with sources of variation existing at each pipeline step [12]. Strategies to enhance reproducibility include:

- Standardizing imaging protocols across participating centers [16]

- Reporting detailed acquisition and reconstruction parameters [12]

- Performing test-retest analyses to assess feature stability [12]

- Using public datasets like the RIDER Lung collection for validation [12]

The radiomics quality score (RQS) provides a framework for evaluating methodological quality, though current literature shows generally low average scores, indicating room for improvement in study design and reporting [12].

The radiomics pipeline represents a comprehensive framework for converting standard medical images into mineable, high-dimensional data with potential applications across cancer diagnostics and therapeutics. While technical challenges remain—particularly regarding reproducibility, standardization, and validation—methodological advances continue to enhance the robustness of radiomics studies. For research and drug development professionals, understanding each component of this pipeline is essential for designing rigorous studies, developing reliable biomarkers, and ultimately translating radiomics into clinically valuable tools. Future directions include increased integration with pathomics and genomics data, development of more automated and standardized pipelines, and emphasis on external validation in diverse patient populations.

Pathomics, an emerging field at the intersection of digital pathology and artificial intelligence (AI), is revolutionizing cancer diagnostics and prognostics by extracting high-throughput, quantitative features from digitized histology images. This technical guide explores how pathomics uncovers critical prognostic information embedded within whole-slide images (WSIs) that eludes conventional visual assessment. Framed within the broader context of radiomics and multi-omics integration in cancer research, we detail the computational frameworks, experimental protocols, and clinical applications driving this innovative field. For researchers and drug development professionals, this whitepaper provides a comprehensive overview of current methodologies, validation strategies, and future directions for leveraging sub-visual histologic patterns to advance precision oncology.

The complex etiology and pronounced heterogeneity of malignant tumors present significant challenges in diagnosis, treatment selection, and prognosis prediction [18]. While histopathological assessment has long been the gold standard for cancer diagnosis, traditional evaluation is inherently subjective, leading to inter-observer variability and limited quantification of tumor biology [18] [19]. The advent of whole-slide imaging (WSI) has enabled the digitization of pathology, creating opportunities for computational analysis that surpass human visual capabilities.

Pathomics applies machine learning (ML) and deep learning (DL) algorithms to extract extensive datasets from WSIs, facilitating quantitative analyses that improve diagnosis, treatment planning, and prognostic prediction [18]. This approach detects subtle morphological patterns in tissue architecture and cellular organization that are imperceptible to the human eye but contain valuable prognostic information. When integrated with radiomics (which extracts quantitative features from medical images like CT and MRI) and other omics technologies, pathomics contributes to a comprehensive multi-modal understanding of tumor biology [20] [21] [22].

The clinical imperative for pathomics is particularly strong in oncology, where tumor heterogeneity influences therapeutic response and disease progression. Current biomarkers have limitations: their assessment often requires invasive tissue sampling, interpretation can be variable, and they frequently fail to capture the full spectrum of tumor heterogeneity [20]. Pathomics addresses these limitations by non-destructively mining rich information from standard histology samples, potentially serving as non-invasive biomarkers for personalized treatment strategies [11].

Technical Foundations of Pathomics

The Pathomics Workflow

The pathomics pipeline involves several critical steps that transform raw WSIs into quantifiable, clinically actionable insights [18]. The standardized workflow ensures reproducible and biologically meaningful feature extraction.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing: Researchers use high-resolution scanning devices to digitize tissue slides, followed by standardization procedures to produce high-quality, uniform images. Stain normalization techniques, such as the Macenko method which utilizes color deconvolution, are often employed to minimize the impact of staining variations on feature computation [23].

Segmentation and Annotation: Each WSI is subdivided into smaller patches or regions of interest (ROIs) that are meticulously annotated by pathologists. This step is crucial for accurate feature extraction in subsequent stages. Advanced algorithms can automatically segment tumor regions, cellular structures, and other histological compartments [24] [19].

Feature Extraction and Selection: Quantitative analysis of tissue structures—including cellular morphology, nuclear characteristics, and tissue architecture—is performed within target regions. Features are extracted at the patch level using pretrained models and subsequently aggregated into slide-level features via attention-based weighted averaging mechanisms [18]. Common feature classes include:

- Histogram-based features: First-order statistics describing intensity distributions

- Texture features: Gray-level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM) features that capture spatial relationships between pixels

- Wavelet features: Multi-resolution texture descriptors obtained through discrete wavelet transforms

- Local Binary Patterns (LBP): Rotation-invariant texture descriptors

Model Construction and Validation: Appropriate model architectures are selected to train on the extracted features, with performance evaluation using metrics including accuracy, precision, F1 score, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC), and decision curve analysis (DCA) [18].

Computational Architectures and Algorithms

In AI-driven pathomics studies, researchers rely on two main architectures: convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and vision transformers (ViTs) [18]. These architectures address core challenges including gigapixel-scale whole-slide images, diverse tumor patterns, and noisy clinical labels.

CNN Backbones: 50-layer ResNet or EfficientNet-B0, pretrained on ImageNet, remain fundamental for patch-level feature extraction. Slides are typically divided into 224 × 224 to 512 × 512 pixel tiles, balancing cellular detail and tissue context within typical GPU memory limits [18].

Vision Transformers: Newer pipelines introduce ViT-base transformers (12 layers) that tokenize slides into 16 × 16 or 32 × 32 pixel patches, learning relationships across distant tissue regions. This capability is particularly valuable for capturing global tissue architecture [18].

Multi-Instance Learning (MIL): Once extracted, patch features are aggregated via attention-based MIL modules. A 128-256-dimensional attention head scores each patch, patches are grouped into 3-5 clusters, and the top 10-20 scores are pooled. This mechanism downweights uninformative areas (e.g., blank space or artifacts) and amplifies diagnostically or prognostically relevant regions, yielding a robust slide-level prediction [18].

Optimization parameters typically include the Adam optimizer with weight decay (1 × 10⁻⁵ to 1 × 10⁻⁴), a learning rate of 1 × 10⁻⁴ to 1 × 10⁻⁵ (often cosine-annealed), and batch sizes of 16-32 tiles per GPU. Models generally train for 20-50 epochs with 20-50% dropout in final layers to prevent overfitting [18].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Prognostic Model Development

A representative experimental protocol for developing pathomics-based prognostic models, as demonstrated in high-grade glioma research [24], involves the following methodology:

Patient Selection and Data Collection:

- Inclusion criteria: Patients with confirmed diagnosis, no prior treatment before confirmed diagnosis, availability of postoperative histopathological findings and histological slides, and complete clinical information.

- Exclusion criteria: Patients without histopathological reports and microscopic sections, WSIs of insufficient resolution for diagnostic use, and lack of post-treatment follow-up data.

- Clinical endpoints: Progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) collected through regular follow-up imaging and clinical evaluation.

Image Preprocessing:

- ROI delineation by experienced pathologists using annotation software (e.g., QuPath)

- WSIs segmented into 512 × 512-pixel tiles at 20× magnification

- White background removal to eliminate tiles with sparse informative content

- Color standardization/normalization across all patches

- Result: Over 12 million viable patches from 80 WSIs in the referenced glioma study [24]

Deep Learning Model Training:

- Implementation of a dual-tier prediction framework combining patch-level predictions with multi-instance learning

- Weakly supervised learning approach labeling patches based on clinical outcomes (e.g., 1-year recurrence)

- Architecture comparison (e.g., densenet121, inception_v3, resnet101) to select optimal model

- Training parameters: Adam optimizer, cross-entropy loss, appropriate learning rate scheduling

Feature Extraction and Selection:

- Development of pathological signature using radiomics-like methodology

- Combination of patch-level predictions, probability histograms, and TF-IDF features

- Removal of redundant features using Pearson's correlation analysis (correlation coefficient threshold < 0.9)

- Further feature refinement using univariate Cox regression and ranking by p-values

- Final feature set determination through LASSO-Cox regression with optimal regularization parameter λ

Model Validation:

- Performance evaluation using concordance index (C-index) for survival models

- Kaplan-Meier survival analysis between high-risk and low-risk groups

- Stratification by molecular subtypes (e.g., IDH status in gliomas)

- Internal validation through bootstrapping or cross-validation

- External validation on independent cohorts when available

Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Pathomics

| Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Annotation Software | QuPath, ImageScope | ROI delineation and pathological annotation |

| AI Platforms | OnekeyAI Platform, TensorFlow, PyTorch | Deep learning model development and training |

| Feature Extraction | PyRadiomics, Custom MATLAB scripts | High-throughput feature quantification from WSIs |

| Whole Slide Imaging | Aperio, Hamamatsu, 3DHistech scanners | Digital conversion of glass slides |

| Statistical Analysis | R, Python (scikit-survival, lifelines) | Survival analysis and model validation |

| Visualization | MATLAB, Python (matplotlib, seaborn) | Feature visualization and result presentation |

Pathomics Applications in Cancer Prognostication

Cancer-Specific Implementation and Performance

Pathomics has demonstrated significant utility across multiple cancer types, with varying emphasis on clinical tasks depending on disease-specific needs [19].

Table 2: Pathomics Applications and Performance Across Cancer Types

| Cancer Type | Common Clinical Tasks | Key Pathomic Features | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate Cancer | Gleason grading, risk stratification | Wavelet features, Local Binary Patterns, glandular architecture | AUC 0.97-0.99 for diagnosis; AUC 0.72-0.73 for grading [23] |

| High-Grade Glioma | Survival prediction, progression risk | Morphological, texture, and deep learning features | C-index 0.847 (train), 0.739 (test) for combined model [24] |

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Diagnosis, histological classification, survival prediction | Nuclear morphology, tissue texture, architectural patterns | AUROC 0.998-1.000 for tumor identification [18] |

| Breast Cancer | Diagnosis, subtyping, treatment response | Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes, spatial arrangements | HER2+, ER+, PR+ subtyping with high accuracy [19] |

| Lung Cancer | Immunotherapy response, recurrence risk | Spatial features, shape-based descriptors | Integrated model achieved HR=8.35 for recurrence prediction [21] |

In prostate cancer, pathomics analysis has identified wavelet features and local binary pattern descriptors as particularly prominent for distinguishing high-grade from low-grade disease, while histogram-based features appear as key differentiators for diagnostic classification tasks [23]. The extremely high heterogeneity of prostate cancer makes it particularly suitable for pathomics approaches that can quantify subtle morphological patterns beyond Gleason grading.

For high-grade gliomas, pathomics models have successfully stratified patients into distinct prognostic groups. One study demonstrated that high-risk patients had a median progression-free survival of 10 months, while low-risk patients had not reached median PFS during the study period [24]. Furthermore, stratification by IDH status revealed significant PFS differences, highlighting how pathomics can enhance molecular classification.

Multi-Modal Integration: Radio-Pathomics

The integration of pathomics with radiomics represents a powerful approach for comprehensive tumor characterization, leveraging both macroscopic (imaging) and microscopic (histology) information [21] [11].

In lung cancer, integrated radio-pathomic models have significantly outperformed single-modality approaches across multiple clinical contexts:

- In early-stage NSCLC, a combined model achieved a hazard ratio of 8.35 (C-index: 0.71) for recurrence prediction, compared to HR=3.99 for radiomics alone and HR=4.83 for pathomics alone [21]

- For predicting immunotherapy response in advanced NSCLC, the integrated model showed an AUC of 0.75, representing a 2% improvement over radiomics and 8% over pathomics alone [21]

- In SCLC, the radio-pathomic model achieved an AUC of 0.78 for chemotherapy response prediction, a 5% improvement over radiomics and 22% over pathomics [21]

The most predictive features from pathomics in these integrated models often derive from spatial feature families, while radiomics contributions frequently come from Haralick entropy features [21]. This complementary information provides a more comprehensive representation of tumor heterogeneity.

Implementation Considerations and Standardization

Technical Validation and Reproducibility

The clinical translation of pathomics faces several challenges that must be addressed through rigorous validation and standardization:

Data Quality and Heterogeneity: Pathomics models are sensitive to variations in tissue processing, staining protocols, and scanning parameters. The National Cancer Institute has emphasized the need for data standardization, image quality assurance, and adoption of open standards such as DICOM for whole-slide imaging to address these challenges [25].

Model Generalizability: Many pathomics models demonstrate excellent performance on internal validation but suffer from performance degradation when applied to external datasets from different institutions. Prospective multi-center studies and the development of robust, explainable AI (XAI) are crucial to overcome this limitation [20] [18].

Regulatory Compliance: As of 2024, only three AI/ML Software as a Medical Device tools have received FDA clearance for digital pathology applications, highlighting the validation dataset gap rather than an absence of regulatory pathways [25]. Future initiatives should prioritize the enhancement of regulatory frameworks and establishment of industry-wide standardized guidelines.

Explainability and Clinical Trust

The inability to interpret extracted features and model predictions remains a major issue limiting the acceptance of AI models in clinical practice [23]. Pathomics approaches increasingly incorporate explainable AI (XAI) techniques such as SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to estimate the importance of pathomic features and their impact on prediction models [23]. This transparency helps build clinical trust and facilitates collaboration between computational scientists and pathologists.

Pathomics represents a paradigm shift in cancer diagnostics and prognostication, moving beyond qualitative histologic assessment to quantitative, data-driven analysis of tumor biology. As the field evolves, several key directions emerge:

Multi-Modal Integration: The combination of pathomics with radiomics, genomics, and clinical data will continue to provide more comprehensive tumor characterization [20] [21] [22]. Projects such as NAVIGATOR, a regional imaging biobank integrating multimodal imaging with molecular and clinical data, illustrate how research infrastructure is advancing to support these ambitions [22].

Foundation Models: Emerging pathological foundation models are revolutionizing traditional paradigms and providing a robust framework for the development of specialized pathomics models tailored to specific clinical tasks [18]. These models, pretrained on large diverse datasets, can be adapted to various cancer types with limited additional training data.

Prospective Validation: The field is moving from proof-concept retrospective studies to prospective validation in clinical trials. The integration of pathomics into cancer clinical trials will be essential for establishing its clinical utility and securing regulatory approval [25].

In conclusion, pathomics unlocks clinically valuable information embedded within routine histology samples that extends far beyond conventional assessment. For researchers and drug development professionals, these approaches offer powerful tools for biomarker discovery, patient stratification, and treatment optimization. As standardization improves and validation expands, pathomics is poised to become an integral component of precision oncology, working alongside established modalities to improve cancer care.

The contemporary paradigm of oncology is undergoing a fundamental shift, moving from isolated analyses of single data modalities to the integrated profiling of tumors through multiple, complementary lenses. This whitepaper delineates the compelling scientific and clinical rationale for creating holistic tumor profiles by integrating radiomics and digital pathology. Such a multimodal approach is paramount for addressing the profound challenge of tumor heterogeneity, both spatially and temporally, which often eludes characterization by single-scale analyses [11] [26]. The core premise is that radiological, histopathological, genomic, and clinical data provide orthogonal yet synergistic information; by computationally fusing these modalities, we can construct a more comprehensive digital representation of a tumor's state, leading to superior biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic response prediction [27]. The following sections provide a technical guide to the quantitative evidence, methodologies, and tools driving this integrative frontier in cancer research and drug development.

Quantitative Evidence for Multimodal Integration

Empirical evidence consistently demonstrates that integrated models outperform their unimodal counterparts. The enhanced performance stems from the complementary nature of the data: radiology describes gross tumor anatomy and phenotype, while histology and genomics reveal cellular and molecular characteristics [27].

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance of Single vs. Integrated Models in Cancer

| Cancer Type | Model Type | Key Modalities | Performance Metric | Value | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endometrial Cancer | Radiomics (CML) | MRI | Sensitivity / Specificity | 0.77 / 0.81 | [28] |

| Endometrial Cancer | Radiomics (DL) | MRI | Sensitivity / Specificity | 0.81 / 0.86 | [28] |

| Esophageal Cancer | Multimodal Radiomics | 18F-FDG PET, Enhanced CT, Clinical | AUSROC | Superior to single-modality | [11] |

| Rectal Cancer | Multiparameter MRI | T2, DWI, DCE | AUSROC | Superior to single-sequence | [11] |

The data in Table 1 underscores two critical trends. First, within a single modality like MRI, more advanced deep learning (DL) models can achieve higher diagnostic performance compared to conventional machine learning (CML) for tasks like detecting myometrial invasion in endometrial cancer [28]. Second, and more significantly, integrating multiple imaging modalities (e.g., PET and CT) or multiple MRI sequences consistently yields superior predictive power compared to any single source [11]. This principle extends beyond imaging; integrating macroscopic radiomic features with microscopic pathomic features—an approach termed radiopathomics—is an emerging frontier that offers innovative approaches for predicting the efficacy of neoadjuvant therapy [11].

Methodological Framework for Integrated Profiling

The workflow for creating a holistic tumor profile is a multi-stage, iterative process that requires rigorous standardization at each step.

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

- Radiomics: Images are acquired from CT, PET, or MRI scanners. For MRI, multiparametric (mpMRI) protocols incorporating T1/T2 anatomical imaging, Diffusion-Weighted Imaging (DWI), and Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced (DCE) MRI are critical for capturing tumor heterogeneity [11]. Preprocessing includes image normalization, resampling, and noise reduction to ensure feature robustness [26].

- Pathomics: Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E)-stained tissue sections are digitized into Whole Slide Images (WSIs) using high-resolution scanners [26]. Preprocessing may involve stain normalization to minimize inter-slide variability.

- Genomics: Data from next-generation sequencing (NGS), such as mutation status and gene expression profiles, are used [27] [26].

- Clinical Data: Patient demographics, laboratory values, treatment history, and outcomes are codified from Electronic Health Records (EHRs), often using Natural Language Processing (NLP) for unstructured text [26].

Feature Extraction and Selection

- Radiomic Feature Extraction: High-dimensional quantitative features are extracted from defined Regions of Interest (ROIs) or Volumes of Interest (VOIs). These include shape, intensity, and texture features (e.g., from Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix) [11]. Deep learning can also learn feature representations directly from image samples [26].

- Pathomic Feature Extraction: Features are extracted from WSIs, which can be expert-guided (e.g., quantifying Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes) or deep-learning derived to capture sub-visual patterns of tissue architecture and cell morphology [27].

- Feature Selection: Given the high dimensionality of the data, feature reduction is essential. Techniques include least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression, and methods that adjust for multiple testing to prevent overfitting [28] [29].

Experimental Protocol: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Framework

For researchers seeking to validate the performance of integrated models, a systematic review and meta-analysis provide the highest level of evidence. The following protocol, adapted from a recent study, offers a detailed methodology [28].

- Study Registration and Protocol: Pre-register the study protocol in a prospective register like PROSPERO to ensure transparency and reduce reporting bias.

- Eligibility Criteria (PICOS):

- Participants: Patients with a specific cancer type (e.g., endometrial cancer).

- Intervention/Index Test: Radiomics-based machine learning models, with or without other data integration.

- Comparator: Standard diagnostic methods or other models.

- Outcomes: Key performance metrics (AUC, sensitivity, specificity, etc.).

- Study Design: Cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional studies.

- Information Sources and Search Strategy: Systematically search electronic databases (PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, Web of Science) using Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and free-text keywords related to the cancer, radiomics, and machine learning.

- Study Selection and Data Extraction: Two independent reviewers screen titles/abstracts and then full-text articles against eligibility criteria. Data is extracted using a standardized form capturing author, year, sample size, model type, features, and performance metrics.

- Quality Assessment: Assess the risk of bias and methodological quality of included studies using the Radiomics Quality Score (RQS), a 16-item tool evaluating aspects like image protocol, feature reduction, validation, and open science [28] [29].

- Synthesis Methods: Pool performance estimates (sensitivity, specificity) using a bivariate random-effects model. Conduct subgroup analyses (e.g., CML vs. DL models) and assess publication bias.

Visualizing the Integrative Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the end-to-end pipeline for creating a holistic tumor profile, from multi-modal data acquisition to clinical application.

Successful execution of an integrated profiling study requires a suite of computational tools, data resources, and analytical techniques.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents & Solutions for Integrated Profiling

| Category | Item / Resource | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) | Public repository of cancer medical images (CT, MRI, etc.) for radiomics research. [30] |

| cBioPortal / GEO | Platforms for accessing and analyzing multidimensional cancer genomics data. [30] | |

| Pathway Commons / KEGG | Databases of biological pathways and networks for functional interpretation of molecular data. [31] | |

| Software & Libraries | R/Python with specialized packages (e.g., Pathview) | Statistical computing and creation of pathway visualizations integrated with genomic data. [31] |

| Cytoscape with plugins (WikiPathways, Reactome FI) | Network visualization and analysis, integrating pathways with other omics data. [31] | |

| Deep Learning Frameworks (TensorFlow, PyTorch) | Building and training complex models for feature extraction and data integration. [26] | |

| Analytical Techniques | Radiomics Quality Score (RQS) | A 16-item scoring system to ensure the methodological quality and reproducibility of radiomics studies. [28] [29] |

| Delta Radiomics | Quantifying changes in radiomic features during treatment to assess therapy response. [11] | |

| Graph Network Clustering | Identifying radiophenotypes with distinct prognoses from high-dimensional radiomic data. [30] | |

| Unbalanced Optimal Transport | A computational method used in clustering algorithms to handle datasets with complex distributions. [30] |

The integration of radiomics, pathomics, and genomics is not merely a technical exercise but a fundamental necessity for advancing precision oncology. The quantitative evidence is clear: multimodal models consistently provide a more accurate and robust characterization of tumor biology than any single data source can achieve alone. By adopting the rigorous methodologies, visual frameworks, and toolkits outlined in this guide, researchers and drug developers can systematically construct holistic tumor profiles. This approach promises to unlock deeper insights into tumor heterogeneity and therapy resistance, ultimately accelerating the development of more effective, personalized cancer therapies and improving patient outcomes. The future of cancer diagnostics and therapeutic development is unequivocally integrative.

Radiomics and digital pathology imaging artificial intelligence (AI) are revolutionizing oncology by transforming standard medical images into mineable, high-dimensional data. These fields represent a paradigm shift toward personalized, data-driven medicine, where quantitative features extracted from computed tomography (CT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and whole-slide images (WSI) provide insights far beyond what the human eye can detect [32] [11]. This integration of macroscopic radiological and microscopic pathological perspectives offers a comprehensive view of tumor heterogeneity—the variation in tumor cells between and within patients—which is a critical factor in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment response [11] [33]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding these technologies is essential for advancing precision oncology, developing more effective therapies, and designing smarter clinical trials that can stratify patients based on their likely treatment response.

Technical Foundations of Radiomics and Pathomics

Core Concepts and Definitions

- Radiomics: A high-throughput process that extracts large sets of quantitative features from standard-of-care medical images such as CT, PET, and MRI [34]. These features, including shape, texture, and intensity, provide a detailed description of tumor characteristics at a macroscopic level [33].

- Pathomics: The application of high-throughput image feature extraction techniques to digitized histopathology slides, especially hematoxylin–eosin–stained sections [33]. It quantifies microscopic patterns such as nuclear morphology, cellular distribution, and tissue architecture [11].

- Radiopathomics: The integration of macroscopic radiomic features with microscopic pathomic features to create a more comprehensive biomarker signature [11] [35]. This multi-scale approach aims to provide a more complete understanding of tumor biology.

The Radiomics and Pathomics Workflow

The machine learning (ML) pipeline for radiomics and pathomics generally follows a structured workflow, which can be implemented through different computational pathways [34]:

- Hand-crafted radiomics: Mathematically designed imaging features are extracted from a segmented region or volume of interest and used to build traditional statistical ML or neural network models.

- Deep radiomics: Deep learning models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), automatically learn and extract features from images.

- End-to-end deep learning: A DL model integrates the entire image processing pipeline, directly predicting outcomes from raw images without manual intervention.

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and pathways in a standard radiomics/pathomics analysis pipeline.

Figure 1: Radiomics and Pathomics Analysis Workflow. The pipeline processes medical images through preprocessing, segmentation, and feature extraction, followed by modeling via one of three primary pathways. CT: Computed Tomography; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; PET: Positron Emission Tomography; WSI: Whole-Slide Imaging; ROI: Region of Interest; VOI: Volume of Interest; CNN: Convolutional Neural Network.

Key Applications in Cancer Diagnostics and Staging

Tumor Characterization and Classification

Radiomics and pathomics enable refined tumor characterization by quantifying phenotypic differences that reflect underlying molecular and pathological subtypes.

- Molecular Subtype Prediction: In uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma (EC), radiomic features from Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) maps and post-contrast T1 (T1C) images show significant cross-scale correlations with pathomic features derived from histopathology images [33]. These correlations (with strengths ranging from 0.57 to 0.89 in absolute value for ADC) reflect variations in tumor aggressiveness and tissue composition, providing a non-invasive method to assess intratumoral heterogeneity [33].

- Pathomic Profiling: Quantitative analysis of digitized histopathology images in EC has revealed associations between cellular spatial patterns and radiological features, offering a bridge between in vivo imaging and ex vivo pathology [33].

Staging and Prognostication

AI-driven analysis improves the accuracy of cancer staging and provides prognostic information independent of traditional clinical factors.

- Lymph Node Metastasis Prediction: In rectal cancer, models based on multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) images taken before and after neoadjuvant therapy can predict lymph node metastasis, with combined pre- and post-treatment sequence models outperforming single-time-point models [11].

- Survival Stratification: A post hoc analysis of the CROWN trial in ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) used AI-derived early responses in brain lesions to stratify patients with baseline brain metastases into low- versus high-risk groups, with significantly longer median progression-free survival (mPFS) in the low-risk group (33.3 months versus 7.8 months in the high-risk group) [32].

Predicting Treatment Response

Methodology for Treatment Response Prediction

Predicting response to therapy, particularly to neoadjuvant treatment, is a primary application of radiomics and pathomics. The standard experimental protocol involves several key methodological considerations [11]:

- Imaging Modalities: CT, MRI, PET, and digital pathology WSI each offer distinct advantages. Multiparametric MRI, combining T2-weighted, DWI, and DCE sequences, is particularly valuable for capturing tumor heterogeneity [11].

- Timing of Imaging Examination:

- Pretreatment images capture the baseline heterogeneity of the primary tumor.

- Post-treatment images more directly reflect pathological remission status.

- Delta radiomics/pathomics analyzes changes in features during treatment, capturing dynamic tumor response patterns [11].

- Region of Interest (ROI) Selection: While most studies focus on the intratumoral region, the peritumoral region is increasingly recognized as containing valuable prognostic information about the tumor microenvironment [11].

- Outcome Evaluation: Common endpoints include pathologic complete response (pCR), overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), and RECIST-based assessments [36].

Application Across Cancer Types and Therapies

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies on predicting treatment response across various cancers.

Table 1: Quantitative Evidence for Treatment Response Prediction Using Radiomics and Pathomics

| Cancer Type | Therapy/Context | Biomarker Type | Key Performance Metrics | Study Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metastatic Colorectal Cancer [32] | Atezolizumab + FOLFOXIRI–bevacizumab | AI-driven digital pathology biomarker | - Biomarker-high pts: Superior PFS (p=0.036) and OS (p=0.024)- Treatment-biomarker interaction for PFS (HR 0.69) and OS (HR 0.54) | AtezoTRIBE trial (N=161), validated in AVETRIC (N=48) |

| Mesothelioma [32] | Niraparib (PARP inhibitor) | AI-based imaging (ARTIMES) + genomic ITH | - PFS in ITH-high pts: HR 0.19 (p=0.003)- Pre-treatment tumor volume prognostic for OS (p=0.01) | NERO trial, CT analysis (n=85) |

| Resectable NSCLC [32] | Neoadjuvant Immunotherapy (Atezolizumab) | Radiomics ± ctDNA | - Predicted pCR: AUC 0.82 (radiomics), AUC 0.84 (+ctDNA)- Associated with event-free survival | Exploratory AEGEAN trial analysis (n=111) |

| Advanced HR+/HER2- Breast Cancer [37] | Xentuzumab, Exemestane, Everolimus | Multimodal AI/Radiomics (CT + bone scans) | - 7 of 8 imaging biomarkers predicted clinical benefit- Lower liver/overall tumor volume linked to better response | Phase Ib/II trial, retrospective analysis (n=106) |

| Advanced Gastric Cancer [35] | Immunotherapy-based combination therapy | Radiopathomics Signature (RPS) | - AUCs: 0.978 (training), 0.863 (internal validation), 0.822 (external validation) | Multicenter cohort (n=298), 7 ML approaches |

Multi-Modal Integration for Enhanced Prediction

The integration of multiple data types—radiopathomics—consistently outperforms single-modality approaches.

- Gastric Cancer Immunotherapy: A radiopathomics signature (RPS) developed from baseline CT scans and digital H&E-stained pathology images using interpretable machine learning demonstrated high predictive accuracy for treatment response (AUC of 0.978 in training) and effectively stratified survival risk [35]. Genetic analyses revealed that the high-RPS group correlated with enhanced immune regulation pathways and increased infiltration of memory B cells, providing biological plausibility [35].

- Mesothelioma: A dual AI-genomic approach combining an AI model (ARTIMES) for quantifying tumor volume from routine CT scans with genomic intratumoral heterogeneity measures helped identify patients most likely to respond to PARP inhibitors [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of radiomics and pathomics research requires a suite of specialized tools and platforms for data acquisition, analysis, and validation.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Radiomics and Pathomics

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories & Clouds | NCI Cancer Research Data Commons (CRDC) [38], The Cancer Imaging Archive (TCIA) [33], CPTAC-UCEC [33] | Provides access to comprehensive collections of cancer research data (genomic, imaging, proteomic) for analysis and validation. |

| Visualization Software | Minerva [38], UCSC Xena [38], 3DVizSNP [38] | Light-weight browsers for multiplexed tissue images, exploration tools for multi-omic data, and 3D mutation visualization. |

| Analysis & Programming Tools | UpSetR [38], R/Python with ML libraries (e.g., Scikit-learn, PyRadiomics) [34] | R package for set intersection visualization; core programming environments for feature extraction and model building. |

| Validation Frameworks | METRICS (METhodological RadiomICs Score) [34], CLEAR checklist [36] | Critical tools for assessing the quality, robustness, and reproducibility of radiomics studies. |

| Digital Pathology Standards | DICOM for Whole-Slide Imaging (WSI) [25] | Emerging standard for digital pathology data, facilitating interoperability and data sharing in clinical trials. |

Technical Protocols for Key Experiments

Protocol: Developing a Hand-Crafted Radiomics Model

This protocol outlines the steps for building a predictive model using hand-crafted radiomic features [34].

- Image Acquisition and Preprocessing: Acquire medical images (e.g., CT, MRI) using a standardized protocol. Preprocessing may include image resampling, intensity normalization, and noise reduction to ensure feature robustness and reproducibility.

- Image Segmentation: Delineate the region of interest (ROI) or volume of interest (VOI), typically the primary tumor. This can be done manually by an expert radiologist, semi-automatically, or fully automatically. The segmentation step is critical as it directly impacts feature extraction.

- Feature Extraction: Use a dedicated software library (e.g., PyRadiomics) to extract a high-dimensional set of quantitative features from the segmented ROI/VOI. These features generally encompass:

- First-order statistics: Describe the distribution of voxel intensities (e.g., mean, median, kurtosis, skewness).

- Shape-based features: Describe the three-dimensional geometry of the tumor (e.g., volume, sphericity, surface area).

- Texture features: Describe the spatial relationship between voxels (e.g., Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix - GLCM, Gray-Level Run-Length Matrix - GLRLM).

- Feature Selection and Engineering: Reduce the high dimensionality of the feature set to avoid overfitting. Techniques include:

- Removal of non-informative or redundant features (e.g., low variance, high inter-feature correlation).

- Selection of the most predictive features using statistical tests (e.g., t-test, Mann-Whitney U test) or model-based importance (e.g., LASSO regression).

- Model Training and Validation: Split the dataset into training and validation cohorts. Train a machine learning model (e.g., logistic regression, random forest, support vector machine) on the training set using the selected features. Validate the model's performance on the hold-out validation set or via cross-validation. External validation on a completely independent dataset from a different institution is the gold standard to prove generalizability [36].

Protocol: Conducting a Radio-Pathomic Correlation Study

This protocol describes the methodology for correlating radiomic features with pathomic features, as exemplified in endometrial carcinoma research [33].

- Cohort Selection: Identify a patient cohort with available paired data: pre-treatment radiology images (e.g., MRI ADC maps, T1C images) and corresponding digital pathology whole-slide images (WSI) from subsequent surgical resection or biopsy. Apply inclusion/exclusion criteria based on image quality and tumor content.

- Radiomics Feature Extraction: Follow the hand-crafted radiomics protocol (Section 6.1, Steps 1-3) on the radiology images to generate a set of radiomic features.

- Pathomics Feature Extraction:

- WSI Processing: Digitize H&E-stained slides and generate cell detection maps and cell density maps at multiple resolutions.

- Feature Quantification: Extract a high-dimensional set of pathomic features characterizing cellular morphology, spatial architecture, and tissue texture from the annotated regions.

- Statistical Correlation Analysis: Perform a correlation analysis (e.g., using Spearman's rank correlation) between the extracted radiomic and pathomic features. Use additional statistical measures like Bayes Factor to assess the strength of evidence for the observed correlations. The goal is to identify significant cross-scale associations that link macroscopic imaging patterns to microscopic pathological findings.

Radiomics and digital pathology AI have established themselves as powerful tools in the oncologist's and researcher's arsenal, with demonstrated applications across the cancer care continuum—from refined diagnosis and staging to the prediction of treatment response for therapies including chemotherapy, targeted agents, and immunotherapy. The integration of these modalities into radiopathomics represents the forefront of this field, creating robust, biologically informed signatures that outperform single-modality biomarkers. However, for these technologies to transition from research tools to clinically actionable tests, the field must address challenges of standardization, reproducibility, and validation in large, multi-institutional cohorts. By adhering to rigorous methodological frameworks like METRICS, leveraging open-source data platforms, and fostering collaborative research, the scientific community can unlock the full potential of these technologies to guide precise, patient-specific treatment strategies and advance the field of precision oncology.

From Data to Decisions: Methodological Workflows and Translational Applications

The rise of computational oncology marks a shift toward data-driven cancer diagnostics. Radiomics and digital pathology (often termed pathomics) stand at the forefront of this transformation, enabling the high-throughput extraction of quantitative features from medical images and histology slides to characterize tumor heterogeneity and the microenvironment [11] [39]. These "omics" technologies move beyond qualitative visual assessment, uncovering sub-visual patterns that are intricately linked to clinical outcomes such as diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment response [39].

The technical workflows for processing this imaging data share a common, structured pipeline. This guide details the core computational procedures of image segmentation, feature extraction, and model construction, providing a foundational framework for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to build robust predictive models in oncology.

Foundational Concepts and Integrated Frameworks

Radiomics refers to the high-throughput extraction of a large number of quantitative features from standard-of-care medical images, such as CT, MRI, or PET [11] [39]. These features can capture intra-tumor heterogeneity and provide insights into the tumor microenvironment at a macroscopic level [11]. Pathomics applies a similar principle to digitized pathology whole-slide images (WSIs), providing microscopic details of the tumor from histology slides [11] [40].

While powerful as individual modalities, the integration of radiomics and pathomics into a radio-pathomic framework is an emerging and powerful area of research. This integration offers a more comprehensive view of the tumor by combining macroscopic radiological characteristics with microscopic pathological findings [11]. For instance, a 2025 study on lung cancer demonstrated that integrated radio-pathomic models significantly outperformed models based on either modality alone in predicting disease recurrence and treatment response [21]. This synergy highlights the importance of the underlying technical workflows that enable such multi-modal integration.

The Core Technical Workflow

The standard technical pipeline for radiomics and pathomics is composed of several methodically interconnected stages. The workflow progresses from data preparation through to model deployment, with each stage being critical for the development of a clinically valid and generalizable model [39].

Image Acquisition and Pre-processing

The initial stage involves acquiring medical images or pathology slides and converting them into a standardized, digital format suitable for computational analysis.

- Radiomics Imaging Modalities: Common modalities include Computed Tomography (CT), Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Positron Emission Tomography (PET), and Ultrasound (US). Each offers distinct advantages; CT features are highly reproducible, MRI offers superior soft-tissue contrast, and PET provides insight into functional and biochemical changes [11].

- Digital Pathology Creation: Glass pathology slides are digitized using whole-slide scanners to create high-resolution whole-slide images (WSIs) [40]. The quality of these images is paramount, requiring high-fidelity scanners and appropriate display monitors for pathologist review [41] [40].

- Pre-processing: This step ensures data consistency and quality. In radiomics, it may involve bias field correction (e.g., for MRI), image resampling to isotropic voxels, and intensity normalization [42]. For pathomics, it includes managing stain variation and ensuring focus across the entire WSI.

The following diagram illustrates the complete end-to-end workflow, from data input to clinical application:

Diagram 1: The core technical workflow from data to decision support.

Image Segmentation

Image segmentation is the process of delineating the Region of Interest (ROI) or Volume of Interest (VOI) from which features will be extracted. This is a critical step, as the accuracy of segmentation directly impacts the relevance of the extracted features [39].

- Segmentation Methods:

- Manual Segmentation: Performed by a radiologist or pathologist. It is considered the gold standard but is time-consuming and can suffer from inter-observer variability.

- Semi-Automatic Segmentation: The expert guides and refines an algorithm-driven segmentation, offering a balance between accuracy and efficiency.

- Fully Automatic Segmentation: Utilizes deep learning models (e.g., U-Net, Mask R-CNN) to segment the ROI without human intervention. While highly efficient, it requires large, annotated datasets for training and rigorous validation [39].

- Region of Interest (ROI): The focus is most commonly the primary tumor (intratumoral region). However, increasing evidence shows that the tissue immediately surrounding the tumor (peritumoral region) also contains biologically meaningful information, and incorporating it can improve model performance [11].

Feature Extraction

Feature extraction involves converting the segmented ROI into a set of quantitative, mineable data. These features can be broadly categorized as hand-crafted or deep learning-based.

- Hand-crafted Radiomic/Pathomic Features:

- First-order Statistics: Describe the distribution of voxel/intensities within the ROI without considering spatial relationships (e.g., mean, median, variance, skewness, kurtosis) [39].

- Second-order (Texture) Features: Describe the statistical relationships between voxel intensities and their neighbors. These are calculated from matrices like the Gray-Level Co-occurrence Matrix (GLCM) and Gray-Level Run-Length Matrix (GLRLM) [39] [21].

- Shape-based Features: Quantify the three-dimensional geometry of the ROI (e.g., volume, sphericity, surface area-to-volume ratio) [39].

- Higher-order Features: Derived from filtered images (e.g., using Wavelet, Laplacian of Gaussian, or Gabor filters) to extract repetitive or non-repetitive patterns [42].

- Deep Learning-based Features: Instead of pre-defined feature classes, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) can automatically learn a hierarchical representation of features directly from the image data. While this bypasses manual feature engineering, it often results in less interpretable "black box" models [39].

Table 1: Categories of Hand-Crafted Features in Radiomics and Pathomics

| Feature Category | Description | Example Features | Biological Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| First-Order Statistics | Distribution of voxel/pixel intensities | Mean, Median, Entropy, Energy, Kurtosis | Cellular density, Necrosis |

| Shape & Size | 3D geometry and morphology of the ROI | Volume, Surface Area, Sphericity, Compactness | Tumor growth pattern, Aggressiveness |

| Texture Features | Intra-tumor spatial heterogeneity | Contrast, Correlation, Homogeneity, Entropy (from GLCM, GLRLM) | Tumor heterogeneity, Treatment resistance |

| Transform-based Features | Patterns from filtered image domains | Wavelet, Gabor, Laplacian of Gaussian (LoG) | Underlying textural patterns at multiple scales |

Feature Selection and Model Construction

After extracting a high-dimensional set of features (often exceeding 1,000 per ROI), feature selection is a pivotal step to reduce dimensionality, mitigate overfitting, and improve model generalizability [39] [42].

- Feature Selection Methods:

- Filter Methods (e.g., mRMRe, ReliefF): Select features based on univariate statistical tests (e.g., Wilcoxon rank-sum) or correlation with the outcome, independent of the classifier.

- Wrapper Methods (e.g., Boruta, Recursive Feature Elimination - RFE): Use a predictive model's performance as the criterion to evaluate and select feature subsets. They are computationally intensive but can yield high-performing feature sets.

- Embedded Methods (e.g., LASSO, Random Forest variable importance): Perform feature selection as an inherent part of the model construction process [42].

- Model Construction and Validation: The selected features are used to train a machine learning model for a specific clinical task (e.g., classification, regression, survival analysis). Common algorithms include Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests (RF), and regularized linear models (e.g., LASSO) [42]. Model performance must be rigorously evaluated using appropriate metrics (e.g., AUC, C-index, sensitivity, specificity) and validation techniques, preferably on an independent, external dataset [11] [39].

Table 2: Common Feature Selection Methods and Their Characteristics

| Method | Type | Mechanism | Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| LASSO (L1) | Embedded | Performs variable selection and regularization via L1-penalty | Creates sparse, interpretable models; Handles multicollinearity |

| Boruta | Wrapper | Compares original features with "shadow" features using Random Forest | Robust; Selects all relevant features, not just non-redundant ones |

| Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) | Wrapper | Iteratively removes the weakest feature(s) based on model weights | Effective at finding high-performing feature subsets |

| mRMRe | Filter | Selects features with Max-Relevance and Min-Redundancy | Balances predictive power and feature independence |

| ReliefF | Filter | Weights features based on ability to distinguish nearest neighbors | Non-parametric; Effective for binary and multi-class problems |

The following diagram details the iterative process of feature selection and model building:

Diagram 2: The iterative process of feature selection and model construction.

Advanced Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Delta-Radiomics/Pathomics

A powerful advanced methodology is delta-radiomics/pathomics, which involves analyzing the change in features over time. Instead of relying solely on a single pre-treatment scan, serial images are acquired (e.g., during or after therapy). Models are then built on the temporal changes (delta) of the features, which can more directly reflect tumor treatment sensitivity and pathological remission status [11]. Studies in esophageal and gastric cancers have shown that delta-radiomics models can achieve higher predictive performance for pathological response than models based only on pre-treatment images [11].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Building a Radio-Pathomic Model

The following protocol is adapted from a 2025 study that integrated CT-based radiomics and H&E-based pathomics to predict outcomes in lung cancer [21].

- Objective: To develop an integrated radio-pathomic model for predicting disease recurrence in early-stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC).

- Cohort: 194 patients with early-stage NSCLC.

- Image Acquisition:

- Radiomics: Pre-treatment CT scans were collected. A standard clinical protocol (e.g., slice thickness ≤ 1.5 mm, standard kernel) should be used and documented.

- Pathomics: Digitized H&E-stained whole-slide images from diagnostic biopsies or surgical resections were obtained using a high-resolution slide scanner.

- Image Segmentation:

- Radiomics: The primary tumor was manually segmented on each CT slice by an experienced radiologist to define the 3D VOI.

- Pathomics: The tumor region on each H&E WSI was annotated by a certified pathologist.

- Feature Extraction:

- Radiomics: 1218 radiomic features were extracted from the CT VOIs using the PyRadiomics library in Python. Features included shape, first-order statistics, and texture features (e.g., Haralick, Gabor, Laws).