How 3D-QSAR Predicts Anticancer Compound Activity: A Computational Guide for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of 3D Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling in predicting the activity of anticancer compounds.

How 3D-QSAR Predicts Anticancer Compound Activity: A Computational Guide for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of 3D Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling in predicting the activity of anticancer compounds. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of 3D-QSAR, detailing key methodological approaches like CoMFA and CoMSIA. The content further addresses model troubleshooting, rigorous validation protocols, and practical integration with other computational techniques such as molecular docking and dynamics simulations. By synthesizing recent case studies and advancements, this guide serves as a resource for leveraging 3D-QSAR to accelerate the rational design of novel, potent, and selective anticancer agents.

Understanding 3D-QSAR: The Foundation of Modern Anticancer Drug Design

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a cornerstone of modern computational chemistry, enabling researchers to correlate the chemical structure of compounds with their biological activity. While traditional QSAR methods utilize one or two-dimensional molecular descriptors, Three-Dimensional QSAR (3D-QSAR) extends this concept by incorporating the crucial three-dimensional spatial and electronic properties of molecules. This advanced approach has emerged as an indispensable predictive tool in pharmaceutical and agrochemical design, significantly decreasing the trial-and-error factor in drug development by facilitating the selection of the most promising candidates for synthesis [1].

The fundamental principle underlying all QSAR formalism is that differences in structural properties are responsible for variations in biological activities between compounds [1]. In contrast to classical QSAR, which treats molecules as collections of numerical descriptors without spatial context, 3D-QSAR considers each molecule as a three-dimensional object with specific shape characteristics and interaction potential fields surrounding it. These fields represent regions where molecular bulk may create steric hindrance or where electrostatic potentials may attract or repel binding partners [2]. By quantifying these 3D characteristics, 3D-QSAR models can predict biological activity with greater mechanistic insight and higher precision than their 2D counterparts.

The conceptual foundation of 3D-QSAR rests on the lock-and-key principle of molecular recognition, where complementary interactions between a ligand and its biological target determine binding affinity and subsequent biological effect [3]. Within computer-aided drug design (CADD), 3D-QSAR is classified as a ligand-based drug design (LBDD) approach, meaning it relies on information from known active compounds rather than the 3D structure of the target protein itself [4] [3]. When the exact structure of the biological target is unknown, 3D-QSAR becomes particularly valuable as it extracts critical pharmacophoric information from ligand properties and previously obtained experimental data [3].

Methodological Framework of 3D-QSAR

The development of a robust and predictive 3D-QSAR model follows a systematic workflow with several critical stages, each requiring careful execution to ensure model reliability and relevance.

Data Collection and Preparation

The initial phase involves assembling a dataset of compounds with experimentally determined biological activities, typically expressed as IC₅₀ or EC₅₀ values [2]. The integrity of this dataset is paramount, requiring selection of molecules that are structurally related yet sufficiently diverse to capture meaningful structure-activity relationships [2]. All activity data must be acquired under uniform experimental conditions to minimize noise and systemic bias that could compromise predictive value [2]. For QSAR modeling, IC₅₀ values (concentration required for 50% inhibition) are typically converted to pIC₅₀ (-logIC₅₀) to create a more linear relationship with free energy changes [5]. The assembled dataset is then divided into training and test sets, typically with approximately 75-80% of compounds used for model development and the remaining 20-25% reserved for external validation [6] [5].

Molecular Modeling and Alignment

With the dataset defined, 2D molecular structures are converted into three-dimensional coordinates using cheminformatics tools like RDKit or Sybyl [2]. These initial 3D structures undergo geometry optimization using molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., Universal Force Field) or more accurate quantum mechanical methods to ensure each molecule adopts a realistic, low-energy conformation [2].

Molecular alignment constitutes one of the most critical and technically demanding steps in 3D-QSAR [2]. The objective is to superimpose all molecules within a shared 3D reference frame that reflects their putative bioactive conformations [2]. This process assumes all compounds share a similar binding mode to the same biological target. Alignment can be guided by various approaches:

Table 1: Molecular Alignment Methods in 3D-QSAR

| Method | Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Common Substructure (MCS) | Identifies the largest substructure shared among a set of molecules | Useful for comparing diverse chemotypes even when scaffolds aren't clearly defined [2] |

| Bemis-Murcko Scaffold | Defines a core structure by removing all side chains and retaining only ring systems and linkers | Widely used for clustering and scaffold-based analysis of congeneric series [2] |

| Field-Based Alignment | Aligns molecules based on similarity of molecular interaction fields rather than atom positions | Handles structurally diverse molecules without identical chemical moieties [7] |

| Pharmacophore-Based Alignment | Uses key pharmacophoric features (H-bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic centers, etc.) as alignment points | Effective when common pharmacophoric elements are known [3] |

The critical importance of proper alignment cannot be overstated, as even minor deviations from optimal superposition can introduce significant errors in subsequent model predictions [7]. Innovative approaches like the AlphaQ method perform pairwise 3D structural alignments by optimizing quantum mechanical cross-correlation with a template molecule, offering advantages for handling structurally diverse molecules without identical chemical moieties [7].

Molecular Descriptors and Field Calculation

Following alignment, 3D molecular descriptors are computed that numerically represent the steric and electrostatic environments of each molecule. The most established approaches in 3D-QSAR are:

Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) uses a lattice of grid points surrounding the aligned molecules [2] [8]. At each grid point, a probe atom (typically a sp³ carbon with +1 charge) measures steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) interaction energies with the molecule [2] [8]. This process effectively maps how a molecular "feel" its environment at various locations, creating a fingerprint-like descriptor of the molecule's 3D shape and electrostatic profile [2].

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) extends this approach by using Gaussian-type functions to evaluate multiple molecular fields simultaneously: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor fields [2]. The Gaussian functions smooth out abrupt field changes that occur near molecular surfaces in CoMFA, making CoMSIA less sensitive to minor alignment discrepancies and enhancing interpretability across structurally diverse compounds [2].

Table 2: Comparison of CoMFA and CoMSIA Approaches

| Feature | CoMFA | CoMSIA |

|---|---|---|

| Fields Calculated | Steric and electrostatic | Steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, H-bond donor, H-bond acceptor |

| Calculation Method | Lennard-Jones and Coulomb potentials on a 3D grid | Gaussian-type similarity functions |

| Sensitivity to Alignment | Highly sensitive; precise alignment crucial | More robust to small alignment changes |

| Application Scope | Best for congeneric series with high structural similarity | Suitable for structurally diverse datasets |

| Interpretation | May have abrupt field changes near molecular surfaces | Smoother field transitions enhance interpretability |

Model Building and Validation

With descriptors computed for all training set molecules, the next step establishes a mathematical relationship between the 3D descriptor values and biological activity. Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression is the most commonly used statistical technique in 3D-QSAR studies, as it effectively handles the large number of highly correlated descriptors generated by field calculation methods [2] [5]. PLS projects the descriptor variables into a smaller set of latent variables that maximize the covariance between descriptor blocks and the response variable (biological activity) [5].

Model validation represents a critical phase in 3D-QSAR development to ensure predictive reliability for new compounds. Multiple validation strategies are employed:

- Internal Validation: Typically performed through cross-validation techniques like leave-one-out (LOO), where each compound is sequentially excluded from training and predicted by a model built from remaining compounds [2] [8].

- External Validation: Uses the previously reserved test set compounds to evaluate model predictivity on completely unknown data [8] [5].

- Statistical Metrics: Model quality is quantified using parameters including R² (goodness-of-fit), Q² (cross-validated correlation coefficient), and R²pred (predictive correlation coefficient for test set) [2] [5]. Robust models typically exhibit high values for all metrics (Q² > 0.5, R²pred > 0.6) [6] [5].

- Applicability Domain Analysis: Determines the chemical space region where model predictions can be considered reliable [5].

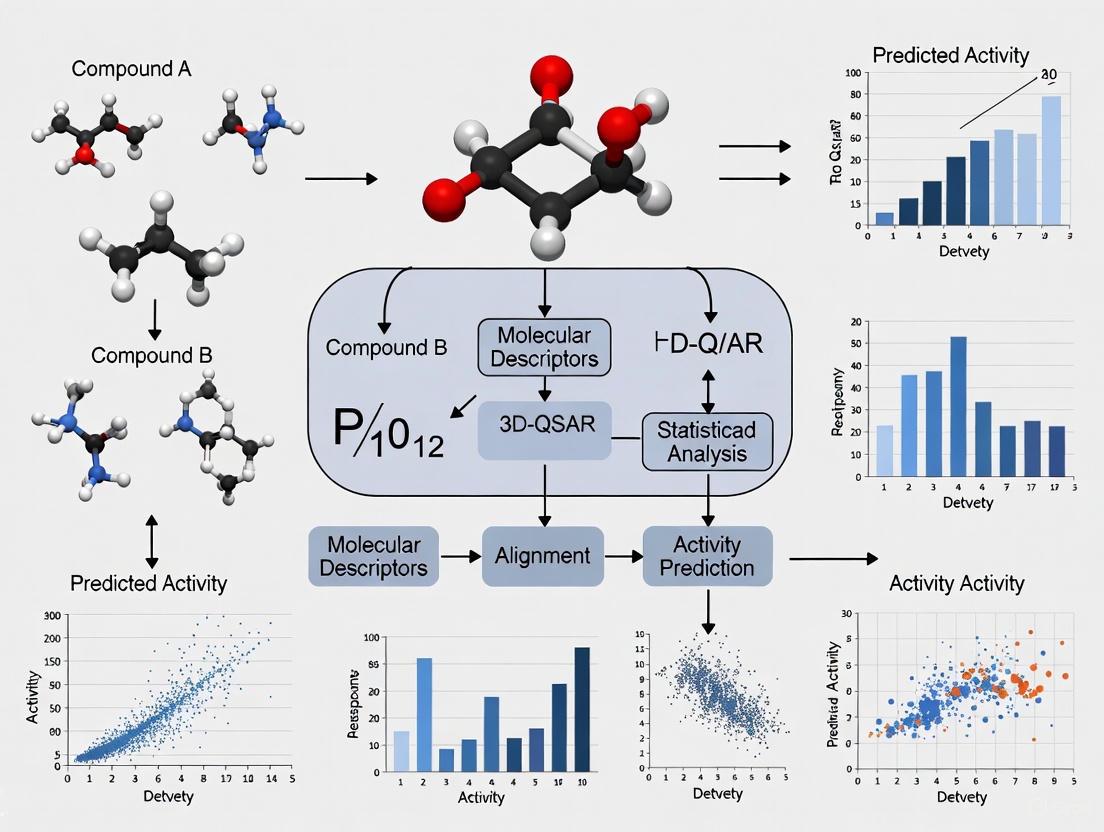

The following diagram illustrates the complete 3D-QSAR workflow from data preparation to model application:

3D-QSAR in Anticancer Drug Discovery: A Case Study on PI3Kα Inhibitors

The application of 3D-QSAR in anticancer drug discovery is effectively illustrated by recent research on PI3Kα inhibitors. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) has emerged as a promising molecular target for novel anticancer agents, with selective inhibition of the PI3Kα isoform representing a favorable strategy for achieving therapeutic efficacy with improved safety profiles [9].

In a comprehensive CADD study, benzoxazepine and thiazole derivatives were investigated through integrated computational approaches including molecular dynamics, ensemble docking, and 3D-QSAR studies [9]. The research aimed to identify structural features critical for PI3Kα activity and selectivity over other isoforms (PI3Kβ, PI3Kγ, PI3Kδ). The 3D-QSAR analysis revealed key structural determinants for potent and selective PI3Kα inhibition:

- Specific molecular interactions with αVal851 in the hinge region were identified as crucial for PI3Kα inhibition [9].

- Additional substructures binding to the hydrophobic region, particularly interacting with αGln859, contributed significantly to isoform selectivity [9].

- The 3D-QSAR predictions guided scaffold-hopping and R-group replacement strategies to design structurally diverse PI3Kα inhibitors with improved selectivity profiles [9].

This case study demonstrates how 3D-QSAR contour maps provide visual guidance for medicinal chemists by identifying spatial regions where specific molecular features enhance or diminish biological activity. For example, steric contour maps highlight regions where adding bulky groups is favorable (green contours) or unfavorable (yellow contours), while electrostatic maps indicate areas that benefit from electronegative (red) or electropositive (blue) groups [2]. These visualizations translate complex statistical models into intuitive design rules for optimizing anticancer compounds.

The outcome of this integrated computational approach was the identification of new chemotypes with selective PI3Kα inhibitory potential, including chromeno[3,4-d]imidazole, 2H-benzo[b][1,4]oxazine, and quinoline derivatives [9]. This exemplifies how 3D-QSAR establishes a rational framework for anticancer drug design, providing foundation for the development of targeted therapies with potentially improved efficacy and reduced off-target effects.

Successful implementation of 3D-QSAR in anticancer drug discovery requires specialized computational tools and resources. The following table summarizes key components of the 3D-QSAR research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for 3D-QSAR

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Function in 3D-QSAR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Cheminformatics Software | RDKit, ChemOffice | Convert 2D structures to 3D coordinates; generate molecular descriptors [2] [6] |

| 3D-QSAR Specialized Platforms | FLARE, Sybyl | Perform molecular alignment, field calculations, and PLS regression modeling [6] |

| Molecular Visualization | Discovery Studio Visualizer | Analyze contour maps and ligand-receptor interactions [6] |

| Protein Structure Databases | RCSB PDB | Source experimental protein structures for structure-based alignment [6] |

| Compound Libraries | PubChem | Access chemical structures and properties for dataset assembly [6] |

| Force Field Packages | UFF, AMBER, CHARMM | Geometry optimization and molecular dynamics simulations [2] |

| Quantum Chemical Software | Gaussian, ORCA | Calculate quantum mechanical descriptors (electrostatic potentials) [7] |

Advanced computational infrastructure has significantly enhanced 3D-QSAR capabilities in recent years. Structure prediction tools like AlphaFold have revolutionized protein structure determination, enabling more accurate structure-based alignments when experimental structures are unavailable [4]. Similarly, integration of quantum mechanical descriptors has demonstrated improved predictive capability compared to traditional empirical potential functions [7]. In one recent application, quantum mechanical electrostatic potential (ESP) descriptors combined with artificial neural network algorithms yielded highly predictive 3D-QSAR models for hERG channel blockers, with squared correlation coefficients exceeding 0.79 for external test sets [7].

The continuing evolution of these computational resources ensures that 3D-QSAR remains at the forefront of anticancer drug discovery, providing increasingly sophisticated and predictive models to guide therapeutic design.

3D-QSAR represents a mature yet continuously evolving methodology within the computer-aided drug design landscape. By leveraging the three-dimensional structural and electronic properties of molecules, 3D-QSAR provides critical insights into the molecular determinants of biological activity that extend beyond conventional 2D QSAR approaches. The integration of 3D-QSAR with complementary computational techniques—including molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and virtual screening—creates a powerful framework for rational drug design and optimization.

In the specific context of anticancer compound discovery, 3D-QSAR has demonstrated significant utility in identifying critical structural features governing target inhibition and selectivity, as exemplified by the PI3Kα inhibitor case study. The methodology's ability to translate complex structural-activity relationships into visual contour maps provides medicinal chemists with intuitive guidance for molecular design. Furthermore, ongoing advancements in computational infrastructure, including improved alignment algorithms, quantum mechanical descriptors, and machine learning integration, continue to enhance the predictive power and application scope of 3D-QSAR models.

As anticancer drug discovery increasingly focuses on targeted therapies with precise mechanism of action, the role of 3D-QSAR in elucidating subtle structure-activity relationships will remain indispensable. By enabling rational design of compounds with optimized potency, selectivity, and safety profiles, 3D-QSAR contributes significantly to the development of next-generation anticancer therapeutics with improved clinical outcomes.

In modern anticancer drug discovery, the high failure rates and immense costs associated with developing new therapies necessitate more efficient approaches. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a computational cornerstone in this endeavor, mathematically linking a chemical compound's structure to its biological activity. The transition from traditional 2D-QSAR to three-dimensional (3D) methods marks a critical evolution, enabling researchers to account for the spatial and electronic properties that govern molecular interactions with cancer-related biological targets. These integrative computational strategies are now indispensable for prioritizing promising drug candidates, reducing reliance on animal testing, and guiding rational chemical modifications to improve efficacy [10] [11].

Within oncology, 3D-QSAR techniques are particularly valuable for understanding how potential drug molecules interact with specific cancer targets, such as aromatase in breast cancer or tubulin in various carcinomas. By employing 3D-QSAR-based pharmacophore modeling and molecular field analysis, researchers can decode the essential structural features required for anticancer activity and predict the potency of novel compounds before they are ever synthesized. This review details the core principles of these methods, focusing on their application in predicting anticancer compound activity, and provides a detailed examination of the methodologies, validation techniques, and practical implementations that define the current state of the field [10] [12].

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

The Fundamental Principle of 3D-QSAR

3D-QSAR models operate on the principle that the biological activity of a compound (such as its potency against a cancer cell line) is a function of its three-dimensional molecular properties. Unlike conventional QSAR, which uses generalized physicochemical descriptors, 3D-QSAR incorporates spatial and electronic characteristics relative to a defined molecular conformation and alignment. The general form of this relationship can be expressed as:

Biological Activity = f(Steric Field, Electrostatic Field, ...other 3D properties...)

Where the function 'f' is derived through statistical analysis of a training set of molecules with known activities [11]. These models aim to identify and quantify the critical regions around molecules where changes in steric bulk or electrostatic potential enhance or diminish biological activity. The resulting contour maps provide visual guidance for medicinal chemists, indicating where structural modifications are likely to improve compound potency [13].

Core Components of 3D-QSAR

- Molecular Alignment: The accurate superposition of training set molecules into a common coordinate system is a critical first step, typically based on their presumed binding mode or common pharmacophoric features [13].

- Molecular Fields: These are computed properties sampled in 3D space around the aligned molecules. The most common are:

- Steric (van der Waals) Fields: Representing shape and bulk.

- Electrostatic (Coulombic) Fields: Representing charge distribution.

- Statistical Correlation: Techniques like Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression correlate the variations in molecular field values with variations in biological activity across the compound set [13].

Methodological Framework

Pharmacophore Hypothesis Generation

The pharmacophore represents the essential, minimal set of structural features necessary for a molecule to interact with its biological target. In 3D-QSAR studies, pharmacophore modeling often serves as the foundation for molecular alignment. The generation of pharmacophore hypotheses is a systematic process [12]:

- Feature Identification: The software identifies potential pharmacophoric features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors, hydrogen bond acceptors, aromatic rings, hydrophobic regions) present in a set of active molecules.

- Hypothesis Generation: Multiple pharmacophore models are created by finding common feature configurations among the active compounds. For example, a study on tubulin inhibitors identified a six-point pharmacophore model, AAARRR.1061, consisting of three hydrogen bond acceptors (A) and three aromatic rings (R) [12].

- Hypothesis Scoring and Selection: Generated models are ranked based on a survival score, which evaluates how well the hypothesis explains the biological activity data and the geometric fit of the compounds. The model with the highest correlation coefficient (R²), cross-validation coefficient (Q²), and F value is typically selected for subsequent 3D-QSAR studies [12].

Table 1: Representative Pharmacophore Model Validation Statistics

| Model Name | R² | Q² | F Value | Features | Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AAARRR.1061 [12] | 0.865 | 0.718 | 72.3 | 3 HBA, 3 Ar | Tubulin |

| Example Model 2 | >0.8 | >0.6 | N/A | Variable | Variable |

Molecular Field Analysis: SOMFA

Self-Organizing Molecular Field Analysis (SOMFA) is a grid-based, alignment-dependent 3D-QSAR technique that uses molecular shape and electrostatic potential to build predictive models. The detailed protocol is as follows [13]:

- Data Set Curation: A series of compounds (e.g., 24 quinazoline derivatives as HER2 inhibitors) with known biological activity (pIC₅₀ = -logIC₅₀) is compiled from literature.

- Conformational Sampling and Alignment:

- The lowest energy conformation of each molecule is determined using molecular mechanics (e.g., MM+) and semi-empirical methods (e.g., AM1).

- A reference compound is selected, and all other molecules are superimposed onto it using an atom-based alignment method to minimize the root-mean-square (RMS) deviation of selected atoms.

- Molecular Field Calculation:

- A common 3D grid is defined that encompasses all aligned molecules.

- For each molecule, two master variables are calculated at every grid point:

- Shape Value: The relative distance from the grid point to the molecular surface.

- Electrostatic Value: The molecular electrostatic potential at that grid point.

- PLS Analysis and Model Validation:

- The generated field data (independent variables) are correlated with the biological activity (dependent variable) using Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression.

- The model is validated through leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation, yielding a cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²). A model with a q² > 0.5 is generally considered predictive.

- The final model is assessed by its non-cross-validated correlation coefficient (r²) and F-test value.

Table 2: Statistical Outcomes of a Representative SOMFA Study on HER2 Inhibitors

| Conformation Source | q² (LOO) | r² (non-CV) | F-test Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | 0.767 | 0.815 | 97.22 | [13] |

| HyperChem | 0.662 | 0.792 | 81.92 | [13] |

| AutoDock 4.2 | 0.608 | 0.782 | 76.45 | [13] |

Integrated Computational Strategies in Practice

Synergy with Other In-Silico Methods

Modern anticancer drug discovery rarely relies on 3D-QSAR alone. It is most powerful when integrated into a combined computational strategy. A representative study on aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer exemplifies this integrated approach [10]:

- Initial Screening with 3D-QSAR and ANN: Predictive 3D-QSAR models, sometimes enhanced with non-linear Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), are built and rigorously validated. These models virtually screen and prioritize novel drug candidates (e.g., L1-L12) based on predicted activity.

- Molecular Docking: The top-ranked candidates are subjected to molecular docking studies to evaluate their binding mode and affinity within the target's active site (e.g., the aromatase enzyme). This step helps confirm the structural basis for the activity predicted by QSAR.

- ADMET Prediction: The absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) profiles of the candidates are predicted in silico to filter out compounds with unfavorable pharmacokinetic or toxicological properties.

- Stability and Binding Affinity Assessment: Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are run over time (e.g., 100 ns) to assess the stability of the protein-ligand complex in a simulated biological environment. The binding free energy is often calculated precisely using MM-PBSA (Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area) methods.

- Retrosynthetic Analysis: Finally, for the most promising hit (e.g., candidate L5), a feasible synthetic route is proposed via retrosynthetic analysis, bridging the gap between in-silico design and laboratory synthesis [10].

Advanced Topics: Model Diversity and Visualization

Given the stochastic nature of many feature selection algorithms used in QSAR, it is common to generate multiple models. A key challenge is identifying whether different models capture unique molecular properties or are functionally equivalent due to correlated descriptors. A correlation-based model similarity measure has been developed to address this [14].

This method calculates the similarity between two feature sets by considering the Pearson correlation coefficient between their descriptors. The pairwise similarities between all models can then be visualized using dimensionality reduction techniques like Stochastic Proximity Embedding (SPE). On the resulting 2D map, each point represents a QSAR model, and the distances between points reflect the similarities of the underlying feature sets. This visualization allows researchers to easily identify clusters of closely related models and select a diverse, non-redundant set of models for further analysis or to create a more robust ensemble predictor [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for 3D-QSAR in Anticancer Research

| Tool Category | Example Software/Resource | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Descriptor Calculation | PaDEL-Descriptor, Dragon, RDKit [11] | Generates numerical representations (descriptors) of molecular structures from chemical input. |

| Molecular Docking | AutoDock 4, AutoDock Vina [13] | Predicts the optimal binding orientation and affinity of a small molecule within a protein's binding site. |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, CHARMM [10] | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time to assess complex stability. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Phase (Schrödinger), MOE | Creates and validates pharmacophore hypotheses from a set of active molecules. |

| 3D-QSAR Specific | SOMFA Software [13] | Performs Self-Organizing Molecular Field Analysis to build 3D-QSAR models. |

| Data Set Curation | PubChem, ChEMBL | Provides public repositories of chemical structures and associated bioactivity data for training models. |

The journey from a pharmacophore hypothesis to a refined molecular field analysis model encapsulates the power of computational rational design in modern oncology research. Techniques like 3D-QSAR and SOMFA provide a quantitative and visual framework to understand the intricate relationships between molecular structure and anticancer activity. As the field advances, the integration of these methods with artificial intelligence, robust validation protocols, and diverse model visualization will be paramount. This integrated approach, firmly situated within the broader thesis of computational anticancer drug discovery, significantly accelerates the identification and optimization of novel, potent therapeutic agents against challenging targets like HER2, tubulin, and aromatase, ultimately contributing to the fight against cancer.

In modern drug discovery, Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling serves as a pivotal computational approach that correlates the chemical structure of compounds with their biological activity. While traditional 2D-QSAR utilizes numerical molecular descriptors that are invariant to conformation, three-dimensional QSAR (3D-QSAR) extends this paradigm by incorporating the molecule's spatial orientation and interaction potentials into the analysis [2]. This advancement is particularly valuable in anticancer research, where understanding the precise interaction between inhibitors and their protein targets can accelerate the development of more effective and selective therapies.

The fundamental premise of 3D-QSAR is that biological activity correlates with interaction energy fields surrounding molecules. By analyzing these fields across a series of compounds, researchers can identify structural features that enhance or diminish activity against specific cancer targets [2]. Techniques such as Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA), Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), and pharmacophore modeling have become indispensable tools for medicinal chemists working to optimize lead compounds. These methods have been successfully applied to various cancer targets including polo-like kinase 1 (PLK1), B-Raf kinase, aromatase, and tubulin, demonstrating their broad utility in oncology drug discovery [15] [16] [17].

Theoretical Foundations and Methodological Framework

Core Principles of 3D-QSAR

3D-QSAR methodologies operate on the principle that a compound's biological activity can be predicted from its three-dimensional interaction fields. Unlike traditional QSAR that uses global molecular descriptors, 3D-QSAR represents each molecule with detailed field values measured at numerous spatial points, providing finer resolution of molecular interactions [2]. This approach requires all molecules to be aligned in a shared 3D reference frame that presumably reflects their bioactive conformations when bound to the target protein.

The statistical foundation of 3D-QSAR typically employs Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, which handles the large number of correlated descriptors by projecting them into a smaller set of latent variables [16] [2]. Model quality is assessed through both internal validation (e.g., leave-one-out cross-validation) and external validation using test set compounds not included in model building. Key statistical metrics include Q² (cross-validated correlation coefficient), R² (conventional correlation coefficient), and SEE (standard error of estimation) [18] [16].

Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA)

CoMFA, one of the most established 3D-QSAR methods, calculates steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) interaction energies between each molecule and a probe atom placed at grid points surrounding the molecular ensemble [2] [17]. The resulting interaction energy matrices serve as descriptors for PLS analysis, generating a model that reveals how steric and electrostatic properties influence biological activity.

A significant advantage of CoMFA is its直观的contour maps that highlight regions where specific molecular modifications would enhance activity. However, CoMFA is highly sensitive to molecular alignment and orientation, requiring careful preparation of the molecular dataset [2]. The method also suffers from abrupt changes in potential energy near molecular surfaces, which can be mitigated by various techniques including field smoothing.

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA)

CoMSIA extends beyond CoMFA by incorporating Gaussian-type functions to evaluate similarity indices across multiple fields: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donor/acceptor properties [18] [2]. This approach avoids the singularities inherent in CoMFA's potential functions and provides more stable models less sensitive to molecular alignment.

The inclusion of hydrophobic and hydrogen-bonding fields in CoMSIA often yields models with greater biological relevance, as these interactions frequently mediate ligand binding to protein targets. The method's contour maps directly indicate favorable and unfavorable regions for specific chemical features, providing clear guidance for molecular design [18] [2].

Pharmacophore Modeling

Pharmacophore modeling identifies the essential structural features responsible for biological activity, abstracting specific molecules into a set of generalized chemical functionalities [15] [17]. A pharmacophore model typically includes features such as hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, charged groups, hydrophobic regions, and aromatic rings that collectively define the interaction profile required for binding to a target protein.

Pharmacophore models can be derived either ligand-based (from a set of active compounds) or structure-based (from protein-ligand complexes) [17]. These models serve multiple purposes in drug discovery: they help rationalize structure-activity relationships, guide molecular design, and function as queries for virtual screening of compound databases to identify novel chemotypes with potential bioactivity [19] [17].

Comparative Analysis of 3D-QSAR Methodologies

Table 1: Comparison of CoMFA and CoMSIA Methodologies

| Parameter | CoMFA | CoMSIA |

|---|---|---|

| Fields Calculated | Steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulomb) | Steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor/acceptor |

| Probe Function | Potential functions | Gaussian-type similarity functions |

| Alignment Sensitivity | High - requires precise molecular alignment | Moderate - more robust to alignment variations |

| Contour Interpretation | Shows regions where steric bulk/electrostatics affect activity | Shows favorable/unfavorable regions for chemical features |

| Advantages | Established method with straightforward interpretation | Broader interaction fields, smoother sampling |

| Limitations | Sensitive to orientation, abrupt potential changes | More parameters to optimize, computationally intensive |

Table 2: Statistical Parameters for 3D-QSAR Model Validation

| Statistical Parameter | Interpretation | Acceptable Threshold |

|---|---|---|

| Q² (LOO cross-validation) | Predictive capability of model | > 0.5 [16] |

| R² | Goodness of fit | > 0.8 |

| SEE | Standard error of estimate | Lower values preferred |

| F value | Statistical significance | Higher values preferred |

| R²pred | Predictive power for test set | > 0.6 [16] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflow

Standard 3D-QSAR Workflow

The development of a robust 3D-QSAR model follows a systematic workflow with multiple critical stages. The diagram below illustrates this process:

Data Collection and Preparation

The initial stage involves assembling a dataset of compounds with experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., IC₅₀ values) obtained under uniform conditions [2]. For anticancer applications, this typically includes compounds screened against specific cancer targets or cell lines. The dataset should contain structurally related yet diverse compounds that span a sufficient range of activity values. A common practice involves dividing the dataset into training (∼80%) and test (∼20%) sets to enable model validation [16].

Molecular Modeling and Conformation Generation

2D molecular structures are converted into 3D coordinates using cheminformatics tools like RDKit or Sybyl [18] [2]. These structures undergo geometry optimization through molecular mechanics (e.g., Tripos force field) or quantum mechanical methods to ensure they represent realistic, low-energy conformations [16] [2]. The selection of appropriate bioactive conformations is critical, as this significantly influences subsequent alignment and descriptor calculation.

Molecular Alignment Strategies

Molecular alignment constitutes one of the most technically demanding steps in 3D-QSAR. The objective is to superimpose all molecules in a shared 3D reference frame that reflects their putative binding modes [2]. Common alignment methods include:

- Distill-based alignment: A rigid alignment approach implemented in Sybyl-X software [16]

- Pharmacophore-based alignment: Using common pharmacophore features to guide superposition [17]

- Docking-based alignment: Using binding poses from molecular docking to align molecules [16]

- Maximum Common Substructure (MCS): Identifying the largest shared substructure for alignment [2]

The alignment assumption presumes all compounds share a similar binding mode to the target protein. Imperfect alignment introduces inconsistencies that undermine model quality, particularly for CoMFA [2].

Descriptor Calculation and Model Building

Following alignment, 3D molecular descriptors are computed. In CoMFA, a lattice of grid points surrounds the molecules, with steric and electrostatic interaction energies calculated at each point using a probe atom [2] [17]. CoMSIA employs Gaussian functions to evaluate similarity indices across multiple fields at grid points [18] [2].

The resulting descriptor matrices are analyzed using PLS regression to build models correlating field values with biological activity [16] [2]. The optimal number of components is determined through cross-validation to avoid overfitting. The model is then subjected to rigorous validation before interpretation and application.

Model Validation Techniques

Robust 3D-QSAR models require comprehensive validation to ensure predictive reliability:

- Internal validation: Leave-one-out (LOO) or leave-several-out cross-validation assessing Q² values [16]

- External validation: Prediction of test set compounds not used in model building [16]

- Statistical significance: Fischer randomization testing to confirm model robustness [20]

- Applicability domain: Defining the chemical space where the model provides reliable predictions [21]

Applications in Anticancer Research

Case Study: Pteridinone Derivatives as PLK1 Inhibitors

PLK1 overexpression occurs in numerous cancers (lung, prostate, colon), making it a promising broad-spectrum anticancer target [16]. A 3D-QSAR study on pteridinone derivatives demonstrated excellent predictive models with CoMFA (Q² = 0.67, R² = 0.992) and CoMSIA (Q² = 0.69, R² = 0.974) [16]. Molecular docking identified key interacting residues (R136, R57, Y133, L69, L82, Y139), while molecular dynamics simulations confirmed binding stability over 50 ns. The models successfully identified compound 28 as a promising candidate for prostate cancer treatment, validated by ADMET property screening [16].

Case Study: Indole Derivatives as Aromatase Inhibitors

Aromatase inhibition represents a proven strategy for treating ER+ breast cancer, which accounts for >70% of breast cancer cases [15]. Integrated 3D-QSAR, molecular docking, pharmacophore mapping, and MD simulation studies on indole derivatives identified key pharmacophoric features: one hydrogen bond acceptor and three aromatic rings essential for optimum aromatase inhibitory activity [15]. The most potent compound (4) demonstrated superior binding affinity compared to letrozole, a standard treatment. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed stable binding over 100 ns, and the designed compound S8 showed predicted pIC₅₀ of 0.719 nM, comparable to the most active compound [15].

Case Study: Imidazopyridines as B-Raf Inhibitors

B-Raf kinase mutations occur in approximately 7% of human cancers, with particularly high frequency in melanoma (50-70%), ovarian (35%), and thyroid (30%) cancers [17]. 3D-QSAR studies on imidazopyridine inhibitors generated a CoMSIA model with excellent predictive power (q² = 0.621, r²pred = 0.885) [17]. Pharmacophore modeling revealed two acceptor atoms, three donor atoms, and three hydrophobes as critical features. Virtual screening using this pharmacophore identified novel B-Raf inhibitor scaffolds with potential therapeutic utility [17].

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for 3D-QSAR in Anticancer Research

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Application in 3D-QSAR Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Modeling | Sybyl-X, RDKit, ChemDraw | Compound construction, optimization, 3D conformation generation [18] [16] |

| Molecular Alignment | GALAHAD, Maximum Common Substructure | Superposition of molecules in 3D space [2] [17] |

| Descriptor Calculation | CoMFA, CoMSIA | Computation of steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic fields [18] [16] |

| Statistical Analysis | Partial Least Squares (PLS) | Model building, latent variable analysis [16] [2] |

| Molecular Docking | AutoDock, Vina | Binding mode prediction, structure-based alignment [16] |

| Dynamics Simulation | GROMACS, AMBER | Binding stability assessment [15] [18] |

Integration with Complementary Computational Methods

Modern 3D-QSAR studies increasingly integrate multiple computational approaches to enhance predictive accuracy and biological relevance:

Molecular Docking and 3D-QSAR

Molecular docking predicts the binding orientation of small molecules in protein targets, providing structural insights for 3D-QSAR alignment [16]. Docking-derived alignments can be particularly valuable when compounds lack an obvious common scaffold for ligand-based alignment. The combination of docking and 3D-QSAR has been successfully applied to various cancer targets including PLK1, B-Raf, and aromatase [15] [16] [17].

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations assess the stability of protein-ligand complexes over time, validating docking poses used in 3D-QSAR studies [15] [18]. For instance, MD simulations confirmed the stable binding of compound 4 to aromatase over 100 ns, with RMSD values fluctuating between 1.0-2.0 Å, indicating conformational stability [15] [18]. These simulations provide dynamic insights that complement the static picture from docking and 3D-QSAR.

Pharmacophore-Based Virtual Screening

Pharmacophore models derived from 3D-QSAR serve as effective queries for virtual screening of large compound databases [19] [17]. This approach has identified novel scaffolds with potential anticancer activity against targets including tubulin, B-Raf, and histone deacetylases [19] [17]. The integration of pharmacophore screening with 3D-QSAR creates a powerful workflow for lead identification and optimization.

The field of 3D-QSAR continues to evolve with advancements in computational power, algorithms, and integration with artificial intelligence. Machine learning approaches, particularly deep learning, are increasingly being applied to enhance predictive models and explore complex structure-activity relationships [21] [22]. The growing availability of large-scale chemical libraries and target structures further expands the potential applications of 3D-QSAR in anticancer drug discovery [22].

In conclusion, 3D-QSAR methodologies including CoMFA, CoMSIA, and pharmacophore modeling represent powerful approaches for rational anticancer drug design. By correlating three-dimensional molecular properties with biological activity, these techniques provide valuable insights for optimizing lead compounds and identifying novel chemotypes. When integrated with complementary computational methods and experimental validation, 3D-QSAR significantly streamlines the drug discovery process, contributing to the development of more effective and selective anticancer therapies.

The Critical Role of 3D-QSAR in Targeting Specific Cancer Proteins (e.g., TRAP1, VEGFR-2, AKT1)

The development of targeted cancer therapies relies heavily on understanding the intricate molecular interactions between potential drug compounds and their protein targets. Three-dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling has emerged as a pivotal computational approach that enables researchers to predict the biological activity of compounds by analyzing their spatially-dependent physicochemical properties [23]. Unlike traditional 2D-QSAR methods that utilize molecular descriptors derived from two-dimensional structures, 3D-QSAR incorporates the critical third dimension, accounting for steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding features that fundamentally govern molecular recognition and binding [24] [25]. This advanced methodology has become indispensable in oncology drug discovery, particularly for targeting specific cancer proteins such as VEGFR-2, where it facilitates the rational design of inhibitors with enhanced potency and selectivity [26] [27].

The core premise of 3D-QSAR is that differences in biological activity among compounds can be correlated with changes in their molecular interaction fields when aligned in three-dimensional space [25]. By employing techniques such as Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), researchers can generate contour maps that visually identify regions where specific chemical modifications would enhance or diminish binding affinity to a target protein [23] [28]. This spatial guidance enables medicinal chemists to prioritize synthetic efforts toward analogs with the highest probability of success, significantly accelerating the drug discovery pipeline while reducing costs associated with experimental screening [23].

Key 3D-QSAR Methodologies and Their Application to Cancer Targets

Fundamental 3D-QSAR Approaches

Several sophisticated computational techniques constitute the methodological foundation of 3D-QSAR studies in cancer research, each with distinct advantages for specific scenarios. The most widely adopted approaches include CoMFA (Comparative Molecular Field Analysis), CoMSIA (Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis), and Topomer CoMFA, all of which leverage statistical correlation methods to establish quantitative relationships between molecular fields and biological activity [26] [28].

CoMFA analyzes steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulombic) interaction energies between a probe atom and aligned molecules at regularly spaced grid points, generating three-dimensional contour maps that highlight regions where specific structural modifications would enhance activity [28]. CoMSIA extends this concept by incorporating additional similarity indices, including hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor fields, providing a more comprehensive description of ligand-receptor interactions [23] [28]. Recent studies on phenylindole derivatives as multitarget cancer inhibitors demonstrated the exceptional predictive power of CoMSIA models, with statistical parameters of R² = 0.967 and Q² = 0.814, indicating high reliability for designing novel compounds [28].

Topomer CoMFA represents an alignment-independent methodology that fragments molecules into topomerically aligned segments, making it particularly valuable for virtual screening of large compound databases [26]. A recent investigation of VEGFR-2 inhibitors utilized Topomer CoMFA to develop stable predictive models (q² > 0.5), enabling efficient identification of novel chemotypes with potential antiangiogenic activity [26].

Machine Learning-Enhanced 3D-QSAR Models

The integration of machine learning algorithms with traditional 3D-QSAR approaches has significantly enhanced predictive accuracy and model robustness in recent years [29]. Algorithms such as Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) have demonstrated superior performance compared to conventional statistical methods, particularly for complex targets like estrogen receptor alpha (ERα) [29]. In one notable study, machine learning-based 3D-QSAR models outperformed established VEGA models in accuracy, sensitivity, and selectivity when predicting the endocrine disruption potential of novel chemical entities, offering a more reliable approach for early-stage toxicity assessment [29].

Table 1: Key 3D-QSAR Methodologies and Their Applications in Cancer Research

| Methodology | Key Fields Analyzed | Statistical Parameters | Cancer Targets | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CoMSIA | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic, H-bond Donor/Acceptor | R² = 0.967, Q² = 0.814 [28] | CDK2, EGFR, Tubulin [28] | |

| CoMFA | Steric, Electrostatic | q² = 0.569, R² = 0.915 [23] | MAO-B [23] | |

| Topomer CoMFA | Steric, Electrostatic | q² > 0.5 [26] | VEGFR-2 [26] | |

| Field-Based QSAR | Shape, Electrostatics, Hydrophobicity | R² = 0.92, q² = 0.75 [25] | AKR1B10, NR3C1, PTGS2, HER2 [25] | |

| ML-Based 3D-QSAR | Multiple field types combined with ML algorithms | Superior accuracy/sensitivity vs VEGA models [29] | ERα [29] |

Experimental Protocols for 3D-QSAR in Cancer Protein Targeting

Standardized Workflow for 3D-QSAR Model Development

The development of robust 3D-QSAR models follows a systematic workflow encompassing multiple critical stages, from data preparation to model validation. The initial phase involves compound selection and activity data curation, where a structurally diverse set of compounds with reliable biological activity data (typically IC₅₀ or Ki values) against the specific cancer target is assembled [25] [30]. For instance, a recent study targeting Tubulin for breast cancer therapy compiled 32 triazine derivatives with experimentally determined IC₅₀ values against MCF-7 breast cancer cells, ensuring sufficient structural diversity and activity range for model development [30].

The subsequent molecular alignment step represents perhaps the most critical phase, where all compounds are spatially superimposed according to a hypothesized bioactive conformation [28]. Both ligand-based and structure-based alignment strategies are employed, with the distill alignment technique in SYBYL using the most active compound as a template being a common approach [28]. For cases where the target-bound structure is unknown, field-based template methods such as FieldTemplater can generate pharmacophore hypotheses based on molecular field similarity [25].

Following alignment, molecular field calculations are performed at grid points surrounding the aligned molecules. In CoMSIA methodology, five different fields (steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor) are computed using a probe atom with specific characteristics [28]. The final stage involves Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression analysis to establish correlations between the field descriptors and biological activity, with model quality assessed through cross-validation techniques such as Leave-One-Out (LOO) and external test set validation [28] [30].

Validation Protocols and Statistical Assessment

Rigorous validation is essential to ensure the predictive reliability and applicability domain of 3D-QSAR models. The Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation technique is widely employed, where each compound is systematically removed from the training set, and its activity is predicted using a model built from the remaining compounds [25] [30]. The cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²) serves as a key indicator of model robustness, with values above 0.5 generally considered acceptable and above 0.7 indicating excellent predictive ability [28].

External validation using a test set of compounds not included in model development provides the most stringent assessment of predictive power [28] [30]. For phenylindole derivatives targeting multiple cancer proteins, external validation yielded a high predictive R² (R²Pred = 0.722), confirming model utility for designing novel inhibitors [28]. Additional statistical parameters, including the conventional correlation coefficient (R²), standard error of estimate (SEE), and F-value, collectively provide a comprehensive assessment of model quality and statistical significance [23] [28].

Table 2: Representative Validation Statistics from Recent 3D-QSAR Studies in Cancer Research

| Study Focus | Training/Test Set | R² | Q² (LOO-CV) | R²Pred (External) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenylindole Derivatives (CDK2, EGFR, Tubulin) | 28/5 compounds | 0.967 | 0.814 | 0.722 | [28] |

| 6-Hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamide (MAO-B) | Not specified | 0.915 | 0.569 | Not specified | [23] |

| Maslinic Acid Analogs (MCF-7) | 47/27 compounds | 0.92 | 0.75 | Not specified | [25] |

| Dihydropteridone Derivatives (PLK1) | 26/8 compounds | 0.928 | 0.628 | Not specified | [24] |

| 1,2,4-Triazine-3(2H)-one (Tubulin) | 80:20 split ratio | 0.849 | Not specified | Not specified | [30] |

Case Studies: Targeting Specific Cancer Proteins

Targeting VEGFR-2 for Antiangiogenic Therapy

Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-2 (VEGFR-2) plays a pivotal role in tumor angiogenesis, making it a prime target for anticancer drug development. Recent 3D-QSAR investigations have successfully identified critical structural features governing VEGFR-2 inhibition, guiding the design of novel chemotherapeutic agents [26] [27]. In a comprehensive study combining machine learning with 3D-QSAR, researchers developed predictive models with 82.4% and 80.1% accuracy for training and test sets, respectively, using the K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN) algorithm [26]. The subsequent Topomer CoMFA approach yielded a stable model (q² > 0.5) that highlighted the significance of steric bulkiness, electrostatic effects, and hydrogen bond acceptor capacity for inhibitory potency [26] [27].

Molecular docking simulations integrated with these 3D-QSAR findings revealed that optimal VEGFR-2 inhibitors form crucial hydrogen bonds with key residues Asp1046 and Glu885 in the binding pocket [26]. This integrated approach led to the identification of five promising compounds with Total Scores greater than 6, indicating strong hydrogen bonding interactions and high binding affinity [26]. These results demonstrate how 3D-QSAR contour maps can directly inform molecular optimization strategies to enhance interactions with specific subpockets of VEGFR-2, potentially leading to improved antiangiogenic agents with reduced side effects compared to existing therapeutics.

Multitarget Inhibition for Overcoming Cancer Resistance

The emerging paradigm of multitarget therapy addresses the challenge of drug resistance in cancer treatment by simultaneously inhibiting multiple key proteins involved in tumor progression. A recent groundbreaking study on 2-phenylindole derivatives exemplifies the power of 3D-QSAR in designing such multifaceted inhibitors [28]. The developed CoMSIA model exhibited exceptional statistical reliability (R² = 0.967, Q² = 0.814) and successfully guided the design of six novel compounds with predicted enhanced activity against three critical cancer targets: CDK2, EGFR, and Tubulin [28].

Molecular docking confirmed the superior binding affinities of the newly designed compounds (-7.2 to -9.8 kcal/mol) compared to reference drugs and the most active molecule in the original dataset [28]. Particularly noteworthy was the stability of these complexes, validated through 100 ns molecular dynamics simulations that demonstrated minimal structural fluctuations (RMSD between 1.0-2.0 Å) and tight binding conformations [28]. This comprehensive approach underscores how 3D-QSAR can facilitate the rational design of single compounds capable of simultaneously modulating multiple cancer pathways, potentially overcoming the limitations of monotherapies and addressing compensatory resistance mechanisms.

Targeting Tubulin for Breast Cancer Therapy

Microtubules composed of tubulin heterodimers represent well-established targets for anticancer therapy, with their disruption leading to mitotic arrest and apoptosis in rapidly dividing cancer cells. Recent 3D-QSAR investigations have focused on optimizing 1,2,4-triazine-3(2H)-one derivatives as potent tubulin inhibitors for breast cancer treatment [30]. The developed QSAR model achieved a predictive accuracy (R²) of 0.849 and identified absolute electronegativity and water solubility as key descriptors significantly influencing inhibitory activity [30].

Molecular docking studies revealed that the designed compound Pred28 exhibited exceptional binding affinity (-9.6 kcal/mol) to the tubulin colchicine binding site [30]. Subsequent molecular dynamics simulations over 100 ns confirmed the remarkable stability of this complex, with the lowest root mean square deviation (RMSD) of 0.29 nm and minimal fluctuations (RMSF) indicative of a tightly bound conformation [30]. These computational findings were further supported by ADMET profiling, which predicted favorable pharmacokinetic properties and reduced toxicity risks, highlighting the potential of these derivatives as promising therapeutic candidates for breast cancer treatment [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of 3D-QSAR studies requires a comprehensive suite of computational tools and software resources. The following table summarizes essential research reagent solutions routinely employed in the field, along with their specific functions in the 3D-QSAR workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for 3D-QSAR Studies

| Tool/Software | Primary Function | Application in 3D-QSAR Workflow | Representative Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| SYBYL | Molecular modeling and analysis | Molecular alignment, CoMFA/CoMSIA studies, PLS analysis | Alignment of phenylindole derivatives [28] |

| ChemDraw | 2D structure drawing | Initial structure sketching and representation | Drawing dihydropteridone derivatives [24] |

| Gaussian 09W | Quantum chemical calculations | Geometry optimization, electronic descriptor calculation | DFT optimization of triazine derivatives [30] |

| Forge | Field-based modeling | 3D-QSAR model development using field points | Field-based QSAR on maslinic acid analogs [25] |

| Discovery Studio | Molecular docking and descriptor calculation | Binding site analysis, molecular descriptor generation | Virtual screening of VEGFR-2 inhibitors [26] |

| GROMACS | Molecular dynamics simulations | Stability assessment of protein-ligand complexes | MD simulations of tubulin-inhibitor complexes [30] |

| VEGA | QSAR model development and validation | Building and validating predictive models | Estrogen receptor binding affinity prediction [29] |

| CODESSA | Molecular descriptor calculation | Computing quantum chemical, structural, and topological descriptors | Descriptor calculation for dihydropteridone derivatives [24] |

3D-QSAR methodologies have unequivocally established their critical role in modern anticancer drug discovery, particularly for targeting specific cancer proteins such as VEGFR-2, tubulin, and multitarget combinations. By providing three-dimensional insights into structure-activity relationships, these computational approaches enable rational drug design that significantly accelerates the identification and optimization of promising therapeutic candidates. The integration of 3D-QSAR with complementary techniques including molecular docking, dynamics simulations, and machine learning algorithms has created a powerful paradigm for addressing the complex challenges of cancer therapy, particularly drug resistance and selectivity issues.

Future advancements in 3D-QSAR will likely focus on enhanced integration with artificial intelligence, improved handling of protein flexibility, and more accurate prediction of ADMET properties at earlier stages of drug design. As computational power continues to grow and algorithms become increasingly sophisticated, 3D-QSAR methodologies will undoubtedly remain at the forefront of targeted cancer therapy development, providing researchers with invaluable spatial guidance for molecular optimization and expanding the frontiers of structure-based drug discovery in oncology.

Building and Applying Robust 3D-QSAR Models for Cancer Targets

In modern anticancer drug discovery, Three-Dimensional Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (3D-QSAR) modeling has emerged as a pivotal computational technique for predicting compound activity and guiding rational drug design. Unlike traditional QSAR methods that utilize numerical molecular descriptors, 3D-QSAR incorporates the three-dimensional spatial structures of molecules to correlate their interaction fields with biological activity against specific cancer targets [2]. This approach is particularly valuable in oncology research, where understanding the precise steric and electrostatic requirements for target binding can significantly accelerate the identification of promising therapeutic candidates.

The foundational principle of 3D-QSAR rests on the concept that differences in biological activity correlate with changes in the shapes and intensities of non-covalent interaction fields surrounding molecules [31]. For anticancer applications, this enables researchers to identify critical molecular features necessary for inhibiting cancer-relevant targets such as protein kinases, mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (mIDH1), PI3Kα isoforms, and monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) [9] [18] [32]. The workflow presented in this guide forms an essential component of a comprehensive framework for predicting anticancer compound activity, with proper execution of dataset curation, molecular alignment, and conformational analysis being prerequisites for developing robust predictive models.

Data Set Curation

Compound Selection and Activity Data

The initial and most critical phase in 3D-QSAR model development involves assembling a high-quality dataset of compounds with experimentally determined biological activities. For anticancer research, this typically involves half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) or half-maximal effective concentration (EC50) values measured against specific cancer cell lines or molecular targets [2] [25].

Key requirements for dataset curation include:

- Select structurally related compounds with sufficient diversity to capture meaningful structure-activity relationships

- Obtain all activity data under uniform experimental conditions to minimize protocol-induced variability

- Include compounds spanning a broad range of activity values (typically 3-4 orders of magnitude)

- Verify compound purity and structural identity through appropriate analytical methods

In recent 3D-QSAR studies focused on anticancer agents, datasets have ranged from approximately 30-80 compounds, with activities converted to pIC50 (-logIC50) values for modeling [18] [16] [25]. For example, a study on maslinic acid analogs against breast cancer MCF-7 cells utilized 74 compounds, while research on pteridinone derivatives as PLK1 inhibitors employed 28 compounds [16] [25].

Training and Test Set Division

Proper division of the dataset into training and test sets is essential for model development and validation. The training set builds the statistical model, while the test set evaluates its predictive capability [16].

Table 1: Common Dataset Division Strategies in 3D-QSAR Studies

| Division Method | Application | Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity Stratified Selection | Maslinic acid analogs study [25] | Maintains similar activity distribution in both sets | Ensures representative sampling across activity range |

| Random Selection (80:20 Ratio) | Pteridinone derivatives as PLK1 inhibitors [16] | Simple implementation | May create activity gaps if dataset is small |

| Structural Clustering | Novel mIDH1 inhibitors [32] | Captures structural diversity | Requires molecular similarity calculations |

Molecular Modeling and Conformational Analysis

Generation of 3D Structures

With the dataset defined, two-dimensional molecular structures are converted into three-dimensional coordinates using specialized software tools. Common applications for this process include ChemDraw, ChemBio3D, RDKit, and Sybyl-X [2] [18] [25]. The initial 3D structures subsequently undergo geometry optimization to ensure they adopt realistic, low-energy conformations.

Energy minimization methods:

- Molecular Mechanics Force Fields (e.g., TRIPOS, UFF): Faster computation suitable for large datasets

- Quantum Mechanical Methods (e.g., DFT): Higher accuracy for electronic property calculation

For example, in a study on 6-hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamide derivatives as MAO-B inhibitors, structures were constructed in ChemDraw and optimized using Sybyl-X software with the standardized TRIPOS force field [18].

Conformational Analysis and Bioactive Conformation

Since the selected conformation critically influences alignment and descriptor calculation, identifying putative bioactive conformations represents a crucial step. When structural information for the target-bound state is unavailable, specialized approaches are required.

Methods for bioactive conformation identification:

- FieldTemplater: Uses field and shape similarity to generate a pharmacophore hypothesis from active compounds [25]

- XED Force Field: Employes molecular field-based similarity for conformational search [25]

- Docking-Based Alignment: Uses protein structures (when available) to guide conformation selection

In the maslinic acid analogs study, researchers used FieldTemplater with five active compounds to develop a field-based pharmacophore hypothesis, followed by conformational generation using the XED force field with a gradient cut-off of 0.1 [25]. Each compound typically generates 100-200 conformations for subsequent analysis [33].

Molecular Alignment

Alignment Strategies

Molecular alignment constitutes the most critical and technically demanding step in 3D-QSAR, with proper alignment directly determining model quality [34]. The objective is to superimpose all molecules within a shared 3D reference frame that reflects their putative bioactive orientations.

Table 2: Molecular Alignment Methods in 3D-QSAR

| Alignment Method | Principle | Applications | Software Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Common Substructure | Superimposes atoms of shared molecular framework | Congeneric series with clear common core | Sybyl, Forge, Py-Align |

| Maximum Common Substructure (MCS) | Identifies largest shared substructure among molecules | Diverse chemotypes with partial structural similarity | RDKit, Forge |

| Field and Shape Similarity | Aligns molecules based on electrostatic and steric field similarity | Structurally diverse compounds without obvious common core | Forge, Torch |

| Pharmacophore-Based | Uses identified pharmacophore features as alignment points | When bioactive conformation hypothesis exists | Forge, FieldTemplater |

Practical Alignment Workflow

A robust alignment protocol for 3D-QSAR studies typically follows this sequence [34]:

- Select a reference molecule that represents the dataset, investing time to establish its putative bioactive conformation through comparison with crystal structures or FieldTemplater

- Align remaining compounds to the reference using substructure or field-based algorithms

- Manually inspect alignments for inconsistencies, particularly for molecules with substituents exploring regions not covered by the initial reference

- Add additional reference molecules (typically 3-4 total) to fully constrain the alignment space

- Re-align the complete dataset using substructure alignment with maximum scoring mode

- Iterate until alignment quality is satisfactory across all compounds

Critical consideration: Alignment must be performed before running QSAR analysis and without consideration of activity values to avoid introducing bias and invalidating the model [34]. A common error involves tweaking alignments based on model outliers, which compromises statistical integrity.

Descriptor Calculation and Model Building

3D Molecular Descriptors

Following alignment, 3D molecular descriptors numerically represent steric and electrostatic environments. The classic Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) method uses a lattice of grid points surrounding aligned molecules, with steric (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic (Coulomb) fields calculated at each point using a probe atom [2].

Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) extends this approach by incorporating Gaussian-type functions to evaluate multiple fields while reducing sensitivity to alignment artifacts [2] [18].

Table 3: Field Descriptors in CoMFA and CoMSIA

| Method | Field Types | Probe Atoms | Alignment Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| CoMFA | Steric, Electrostatic | sp³ carbon with +1 charge | High - precise alignment critical |

| CoMSIA | Steric, Electrostatic, Hydrophobic, Hydrogen Bond Donor/Acceptor | Various atom types depending on field | Moderate - more tolerant to minor misalignments |

Statistical Modeling and Validation

With descriptors calculated, the relationship between 3D field values and biological activity is established using Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression, which handles the large number of correlated descriptors by projecting them to latent variables [2] [16].

Model validation is essential and employs multiple strategies:

- Internal Validation: Leave-One-Out (LOO) or Leave-Group-Out cross-validation yielding Q²

- External Validation: Predictive correlation coefficient (R²pred) using test set molecules

- Statistical Metrics: Standard Error of Estimate (SEE), F-value, and optimal number of components

For a model to be considered predictive, Q² should exceed 0.5 and R²pred should be greater than 0.6 [16]. In successful anticancer 3D-QSAR studies, reported Q² values typically range from 0.66-0.77, with conventional R² values of 0.97-0.99 [32] [16] [25].

Experimental Protocols

Standardized 3D-QSAR Protocol for Anticancer Compounds

The following detailed methodology is adapted from recent studies on PLK1 inhibitors and maslinic acid analogs [16] [25]:

Software Requirements: Sybyl-X 2.1, Forge v10, or equivalent molecular modeling software

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Dataset Preparation

- Convert 2D structures to 3D using converter modules (e.g., ChemBio3D, RDKit)

- Add hydrogen atoms and assign Gasteiger-Hückel atomic partial charges

- Perform energy minimization using TRIPOS force field with convergence criterion of 0.005 kcal/mol Å and 1000 iterations

Molecular Alignment

- Identify common substructure or use field-based template for alignment

- Apply rigid body alignment using distill alignment protocol in Sybyl or field similarity in Forge

- Verify alignment quality through visual inspection of superimposed molecules

Descriptor Calculation

- Set grid spacing to 1.0-2.0 Å extending 4.0 Å beyond molecular dimensions in all directions

- Calculate steric and electrostatic fields using sp³ carbon with +1 charge as probe atom

- Apply energy truncation of 30 kcal/mol for both steric and electrostatic fields

PLS Model Development

- Set maximum number of components to 10-20

- Use cross-validated Q² to determine optimal number of components

- Apply column filtering of 2.0 kcal/mol to improve signal-to-noise ratio

Model Validation

- Perform leave-one-out and leave-group-out cross-validation

- Calculate predictive R² for test set compounds

- Conduct y-scrambling (50+ iterations) to verify non-chance correlation

Web-Based Implementation

For researchers without access to commercial software, the www.3d-qsar.com portal provides web-based tools for building 3D-QSAR models through standard browsers without additional installations [31]. The platform includes:

- Py-MolEdit: Dataset compilation and molecular editing

- Py-ConfSearch: Conformational analysis engines

- Py-Align: Automated molecular alignment

- Py-CoMFA: Model building and validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 4: Essential Resources for 3D-QSAR in Anticancer Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Modeling | ChemDraw, ChemBio3D, RDKit | 2D to 3D structure conversion and editing | Initial structure preparation and optimization |

| Molecular Alignment | Sybyl-X, Forge, Py-Align | Molecular superposition and conformational analysis | Critical alignment step for 3D-QSAR |

| Field Calculation | CoMFA, CoMSIA modules in Sybyl or Forge | Steric and electrostatic field computation | Descriptor generation for QSAR models |

| Statistical Analysis | PLS implementation in Sybyl, R packages | Partial Least Squares regression | Model development and validation |

| Validation Tools | Custom scripts, y-scrambling algorithms | Model robustness assessment | Verification of model predictive power |

| Web Platforms | www.3d-qsar.com portal | Integrated 3D-QSAR modeling | Accessible alternative to commercial software |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete 3D-QSAR workflow for anticancer drug discovery, integrating dataset curation, molecular alignment, and conformational analysis into a cohesive research pipeline:

The meticulous execution of dataset curation, molecular alignment, and conformational analysis forms the essential foundation for developing predictive 3D-QSAR models in anticancer compound research. When properly implemented, this workflow enables researchers to extract critical structural insights and generate reliable activity predictions for novel compounds. The integration of these computational approaches with experimental validation creates a powerful strategy for accelerating anticancer drug discovery, ultimately contributing to the development of more effective therapeutic agents for oncology applications.

Within the broader thesis on how 3D-QSAR predicts anticancer compound activity, this case study exemplifies the integrated computational workflow essential for modern oncology drug discovery. The development of inhibitors for TRAP1 (Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor-Associated Protein 1), a mitochondrial chaperone kinase significantly overexpressed in various cancers, presents a compelling target for therapeutic intervention [35] [36]. This technical guide details the construction and validation of a highly predictive 3D-QSAR model for pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine-based TRAP1 inhibitors, a study that demonstrated exceptional statistical performance with an R² of 0.96 and a Q² of 0.57 [35] [37]. The reliability of this model underscores the power of computational approaches in accelerating the identification and optimization of novel anticancer agents by elucidating the critical structural features governing biological activity.

Data Set Preparation and Pharmacophore Modeling

Data Collection and Curation

The foundational step involved curating a data set of 34 pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine analogs with known half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC₅₀) values against TRAP1 from published literature [35]. The biological activity values (IC₅₀ in µM) were converted into pIC₅₀ (-log IC₅₀) to ensure a linear relationship for QSAR analysis. The data set was partitioned into a training set (75%) for model generation and a test set (25%) for external validation [35] [38]. All molecular structures were sketched using ChemDraw Professional 16.0, energy-minimized, and converted into their three-dimensional conformations using the LigPrep module within Maestro v12.1 [35].

Table 1: Representative Data Set of Pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine Analogs and Their TRAP1 Inhibitory Activity

| Compound | R1 Substituent | R Substituent | IC₅₀ (µM) | pIC₅₀ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | Not Specified | Not Specified | 0.50 | 6.30 |

| 9 | Not Specified | Not Specified | 19.00 | 4.72 |

| 42 | Not Specified | Not Specified | 0.44 | 6.36 |

| 46 | Not Specified | Not Specified | 0.47 | 6.33 |

| 59 | Not Specified | Not Specified | 1.00 | 6.00 |

Pharmacophore Hypothesis Generation

Pharmacophore modeling was performed using the PHASE module in Schrödinger [35]. A common pharmacophore hypothesis, DHHRR.1, was identified as the most significant. This hypothesis comprises five distinct chemical features: one hydrogen bond donor (D), two hydrophobic groups (H), and two aromatic rings (R) [35]. The nitrogen atom in the pyrimidine ring often serves as the hydrogen bond donor, critical for interaction with the TRAP1 active site [35].

Diagram: Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

3D-QSAR Modeling and Validation

Model Development and Statistical Outcomes

An atom-based 3D-QSAR model was developed using the PHASE module. The model's robustness was evaluated using a leave-one-out (LOO) cross-validation method, resulting in a Q² value of 0.57, indicating good predictive ability [35]. The non-cross-validated model demonstrated an impressive R² value of 0.96, signifying an excellent fit to the training set data [35]. The model's predictive power was further validated against the external test set, yielding a predictive R² (R²Pred) of 0.58 [35] [37].

Table 2: Statistical Parameters of the 3D-QSAR Model

| Parameter | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| R² | 0.96 | Excellent fit to the training set data |

| Q² (LOO) | 0.57 | Good internal predictive ability |

| R² CV | 0.58 | Satisfactory cross-validated correlation |

| R²Pred | 0.58 | Good external predictive ability |

| PLS Factors | 5 | Number of latent variables used |

Contour Map Analysis and Structural Insights

The 3D-QSAR model generated contour maps around a reference ligand, providing visual guidance for structural optimization. These maps highlight regions where specific chemical features favorably or unfavorably influence biological activity. For instance: