Harnessing Bioinformatics for Novel Anticancer Target Discovery: A Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging bioinformatics to discover novel anticancer drug targets.

Harnessing Bioinformatics for Novel Anticancer Target Discovery: A Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging bioinformatics to discover novel anticancer drug targets. It explores the foundational role of multi-omics data from resources like TCGA and bioinformatics databases in identifying potential targets. The piece details advanced computational methodologies, including molecular docking, dynamics simulations, and AI-driven network biology, for target validation and drug screening. It further addresses critical challenges in data integration and computational demands, offering optimization strategies. Finally, the article covers the essential transition from computational prediction to experimental and clinical validation, highlighting successful case studies and the integration of real-world data to bridge research and clinical practice in precision oncology.

The Bioinformatics Foundation: Mining Multi-Omics Data for Target Discovery

The discovery of novel anticancer drug targets now heavily relies on the systematic analysis of large-scale genomic datasets. Among the most critical resources enabling this research are The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC), and the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC). These complementary platforms provide researchers with comprehensive molecular characterizations of thousands of tumor samples across cancer types, creating unprecedented opportunities for identifying oncogenic drivers and therapeutic vulnerabilities. TCGA, a landmark project jointly managed by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), molecularly characterized over 20,000 primary cancer and matched normal samples spanning 33 cancer types, generating over 2.5 petabytes of multi-omics data [1] [2]. ICGC complements this effort with international data contributions, while COSMIC serves as the world's largest expert-curated knowledgebase of somatic mutations, integrating data from TCGA, ICGC, and over 29,000 peer-reviewed publications [3] [4]. Together, these resources provide the foundational data necessary for advancing precision oncology through bioinformatics-driven approaches.

Table 1: Overview of Major Cancer Genomics Resources

| Resource | Primary Focus | Data Scale | Key Features | Primary Applications in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA | Multi-omics profiling of primary cancers | 20,000+ cases; 33 cancer types; 2.5 PB data | Genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic, proteomic data; matched normal samples | Identifying dysregulated pathways, molecular subtypes, and candidate therapeutic targets |

| ICGC | International genomic data collaboration | 1,600,000+ samples (in COSMIC) | Pan-cancer data from international cohorts; genomic and transcriptomic data | Cross-population validation of targets; expanding diversity of genomic insights |

| COSMIC | Somatic mutation curation and interpretation | 29,000,000+ variants; 1,600,000+ samples | Expert-curated mutations; therapeutic actionability; cancer gene census | Mutation pathogenicity assessment; clinical actionability prediction; resistance mutation identification |

Resource-Specific Profiles and Applications

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)

TCGA represents one of the most comprehensive cancer genomics initiatives, generating data through a highly organized research network structure. The project employed multiple molecular characterization platforms including next-generation sequencing for genome and transcriptome analysis, microarray technologies for nucleic acid and protein testing, and proteomic characterization techniques [2]. The data generation workflow involved Tissue Source Sites for biospecimen collection, Biospecimen Core Resources for sample processing, Genome Characterization Centers for molecular analysis, and Genome Sequencing Centers for high-throughput sequencing [2]. This coordinated approach ensured standardized data generation across participating institutions.

TCGA data encompasses multiple molecular levels, including genomic (somatic mutations, copy number alterations), epigenomic (DNA methylation), transcriptomic (gene expression, non-coding RNA), and proteomic (protein expression) data [5]. The program studied specific cancers based on criteria including poor prognosis, public health impact, and sample availability meeting standards for patient consent, quality, and quantity [6]. Many rare cancers were also included with support from patients, patient advocacy groups, and clinicians [6].

For drug target discovery, TCGA data enables researchers to identify dysregulated pathways, molecular subtypes within cancer types, and co-occurring genomic alterations that may inform combination therapy strategies. The rich clinical dataset associated with molecular profiles allows for correlation of molecular features with treatment response and survival outcomes [7] [8].

Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC)

COSMIC is the world's largest and most comprehensive resource for somatic mutations in cancer, manually curated by experts to provide highly standardized data. The knowledgebase contains over 29 million genomic variants across more than 1.6 million samples, including single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions and deletions, structural variants, copy number variations, and gene fusions [3] [4]. COSMIC integrates data from genome-wide screens and targeted analyses, enabling robust insights into cancer genomics.

The platform offers several specialized modules designed to support different aspects of cancer research and drug discovery. The COSMIC Gene Census identifies and ranks over 750 genes with documented roles in cancer, classifying them into Tier 1 (strong evidence) and Tier 2 (emerging evidence) categories [3]. The Mutation Census tracks coding mutations and differentiates between driver and passenger mutations based on pathogenicity and frequency [3]. The COSMIC Signatures module catalogues mutational patterns across different mutation types, helping identify underlying mutational processes [3].

For therapeutic development, the Actionability module provides data on available therapies and clinical trials for specific mutations, while the Resistance module curates mutations known to confer resistance to cancer treatments [3]. The COSMIC 3D module offers structural insights into protein mutations, enabling visualization of how mutations alter protein-drug interactions [3].

Table 2: COSMIC Database Content by Variant Type and Sample Source

| Variant Type | Count in COSMIC | Sample Source | Count in COSMIC |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNV | 23,000,000 | Solid Cancers | 1,150,000 |

| Insertions & Deletions | 2,000,000 | Blood & Lymphatic Cancers | 444,000 |

| Structural & Copy Number | 4,300,000 | Circulating Tumor DNA | 6,000 |

| Fusions | 20,000 | Most Prevalent Cancers (WHO) | |

| Trachea, bronchus, lung | 217,049 | ||

| Colorectum | 216,352 | ||

| Breast | 62,902 | ||

| Stomach | 29,858 | ||

| Prostate | 26,103 |

Data Integration and Complementary Strengths

While each resource has distinct strengths, their integration provides powerful insights for drug target discovery. TCGA offers deep multi-omics profiling of carefully selected primary tumors with matched normal controls, enabling comprehensive molecular characterization of specific cancer types [1] [8]. ICGC provides international diversity and additional cases that expand the scope beyond TCGA's primary focus. COSMIC delivers expert curation and integration of somatic mutation data from both large-scale projects and targeted studies, creating a comprehensive knowledgebase of cancer genomic alterations [3] [4].

The integration of these resources enables researchers to move from single-omics analyses to multi-omics integration, providing a more complete understanding of cancer biology. For example, combining genomic mutation data from COSMIC with transcriptomic and proteomic data from TCGA can reveal how mutations impact gene expression and protein function [8]. This integrated approach helps distinguish between passenger mutations that accumulate in cancer cells and driver mutations that directly contribute to oncogenesis, thereby prioritizing the most promising therapeutic targets.

Practical Access and Analytical Methodologies

Data Access Protocols

TCGA Data Access via Genomic Data Commons (GDC)

The primary hub for accessing TCGA data is the Genomic Data Commons (GDC) Data Portal, which provides harmonized data aligned to the GRCh38 reference genome [5]. The GDC workflow involves:

- Cohort Building: Using the "Cohort Builder" to select cases of interest based on project, disease type, demographic, or clinical criteria

- Data Selection: Filtering files in the "Repository" by data type (e.g., gene expression, mutations, methylation)

- Data Download: Downloading files directly for small datasets (<5GB) or using the GDC Data Transfer Tool for larger datasets [5]

Researchers should note that TCGA data is categorized as either open-access or controlled-access. Controlled data includes individual germline variants, primary sequence files (.bam), and clinical free text, requiring dbGaP authorization [5]. For programmatic access, the GDC API provides a powerful interface for querying and retrieving data [5].

Alternative TCGA Data Access Points

Several specialized portals offer alternative access to TCGA data with enhanced analytical capabilities:

- cBioPortal: Provides intuitive visualization of genetic alterations across cancer samples, including mutation rates, copy number alterations, and mRNA expression z-scores, coupled with survival analysis capabilities [9]

- Broad Institute's GDAC Firehose: Offers merged, analysis-ready files from TCGA, with pre-processed data structures suitable for R-based analysis [9]

- University of California Santa Cruz Xena: Enables integrated analysis of TCGA data with other genomic and phenotypic data through interactive visualizations

COSMIC Data Access and Utilization

COSMIC provides both web-based query interfaces and downloadable data sets for approved users. The typical workflow for leveraging COSMIC in target discovery involves:

- Gene Search: Querying specific genes of interest to retrieve mutation frequency, distribution, and functional impact data

- Tissue-Specific Analysis: Examining mutation patterns across different cancer types to identify tissue-specific versus pan-cancer mutations

- Pathogenicity Assessment: Using the Mutation Census to evaluate the likely functional impact of mutations

- Clinical Actionability Review: Consulting the Actionability and Resistance modules to understand therapeutic implications

Analytical Workflows for Target Discovery

The following diagram illustrates a representative integrated workflow for anticancer drug target discovery using public genomics resources:

Integrated Workflow for Cancer Target Discovery

Transcriptomics-Based Target Identification Protocol

A proven methodology for identifying novel therapeutic targets involves integrated analysis of transcriptomics data from TCGA with mutation information from COSMIC [7]:

- Sample Selection: Identify tumor and matched normal samples for the cancer type of interest using TCGA's clinical annotations

- Differential Expression Analysis: Calculate significantly upregulated genes in tumors compared to normal tissues using RNA-seq data

- Tissue-Specificity Filtering: Filter results to exclude genes with high expression in vital normal organs (e.g., heart, lungs, liver, kidney)

- Mutation Enrichment Analysis: Cross-reference upregulated genes with COSMIC mutation data to identify frequently mutated candidates

- Functional Annotation: Classify candidates using COSMIC's Gene Census and assess mutation impact using COSMIC 3D

- Survival Correlation: Evaluate the correlation between candidate gene expression and patient survival using clinical data

- Experimental Validation: Perform functional validation using RNA interference or CRISPR/Cas9 systems in relevant cancer cell models

This approach successfully identified several promising drug targets, including MELK (maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase), TOPK (T-lymphokine-activated killer cell-originated protein kinase), and BIG3 (brefeldin A-inhibited guanine nucleotide-exchange protein 3) in breast cancer [7].

Pan-Cancer Analysis Protocol

For identifying targets across multiple cancer types:

- Data Compilation: Aggregate mutation data from TCGA and ICGC via COSMIC's integrated dataset

- Mutational Significance Analysis: Identify genes with mutation rates significantly above background using mutational burden calculations

- Functional Impact Prediction: Filter mutations based on predicted functional consequences (e.g., missense vs. truncating)

- Pathway Enrichment: Map frequently mutated genes to signaling pathways using pathway databases

- Druggability Assessment: Evaluate the biochemical druggability of candidate targets using structural information

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Cancer Genomics

| Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function in Research | Application in Target Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Access Portals | GDC Data Portal; ICGC Data Portal; COSMIC Website | Centralized access to genomic data and annotations | Initial data retrieval and cohort selection |

| Analysis Platforms | cBioPortal; Firebrowse; TANRIC; MEXPRESS | Interactive analysis and visualization of cancer genomics data | Rapid hypothesis testing and data exploration |

| Bioinformatics Tools | GDC Data Transfer Tool; BigQuery; R/Bioconductor | Large-scale data processing and statistical analysis | Advanced computational analysis and integration |

| Experimental Validation | CRISPR/Cas9; RNAi; Organoid culture | Functional validation of candidate targets | Confirmation of target essentiality in disease models |

| Specialized Databases | COSMIC Gene Census; Cancer Proteome Atlas (TCPA) | Curated information on cancer genes and proteins | Target prioritization based on biological evidence |

The integration of TCGA, ICGC, and COSMIC resources provides an unprecedented foundation for anticancer drug target discovery. By leveraging the multi-omics data from TCGA, international diversity from ICGC, and expert-curated mutation information from COSMIC, researchers can identify and prioritize novel therapeutic targets with greater efficiency and confidence. The practical protocols and resources outlined in this whitepaper provide a roadmap for harnessing these powerful platforms to advance the development of targeted cancer therapies. As these resources continue to expand and improve, they will undoubtedly play an increasingly vital role in translating cancer genomics discoveries into clinical applications that improve patient outcomes.

The discovery of novel anticancer drug targets is a cornerstone in the fight against cancer, a disease that remains a leading cause of mortality worldwide [10] [11]. Traditional drug discovery processes are notoriously lengthy, expensive, and carry high failure rates in clinical trials [12] [13]. Bioinformatics has emerged as a transformative discipline, leveraging computational power and biological data to accelerate the identification and validation of new therapeutic targets. By integrating genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and pharmacological data, bioinformatics resources enable researchers to prioritize candidate genes and proteins with higher precision and efficiency [12] [14]. Among the plethora of available tools, three databases—cBioPortal, GEPIA2, and canSAR—have become indispensable for modern cancer research and drug development. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these core resources, detailing their functionalities, integrated application in experimental workflows, and their pivotal role in advancing anticancer drug discovery.

Database Profiles and Key Features

This section details the core characteristics, data sources, and primary functions of cBioPortal, GEPIA2, and canSAR, summarizing their key attributes for easy comparison.

Table 1: Core Features of cBioPortal, GEPIA2, and canSAR

| Feature | cBioPortal | GEPIA2 (Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis) | canSAR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Multidimensional cancer genomics data and clinical outcomes [15] | Gene expression profiling and interactive analysis [16] | Integrated translational research and drug discovery knowledgebase [17] |

| Core Data Types | Somatic mutations, DNA copy-number alterations, mRNA expression, DNA methylation, clinical data [15] | RNA-seq expression data from TCGA tumors and GTEx normal tissues [16] [18] | Genomic, protein, pharmacological, drug, chemical, structural biology, protein network, and druggability data [17] |

| Key Functionality | Visualize genetic alterations; query genes across samples; survival analysis; group comparison [15] | Differential expression analysis, profiling plotting, correlation, patient survival analysis, similar gene detection, dimensionality reduction [16] | Provides drug target prioritization, druggability assessment, and compound screening based on integrated data [17] |

| Unique Strengths | Intuitive visualization of complex genomic data in a clinical context; supports multi-gene queries [15] | Addresses the imbalance between tumor and normal samples by incorporating GTEx data; customizable analyses [16] | Multidisciplinary data integration; uses 3D structural information to assess protein druggability [17] |

cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics

cBioPortal is an open-access platform for the interactive exploration of multidimensional cancer genomics datasets [15]. It effectively translates complex genomic data into biologically and clinically actionable insights, making it particularly valuable for generating initial hypotheses about potential driver genes in specific cancer types.

GEPIA2 for Gene Expression Analysis

GEPIA2 was developed to fill the gap between cancer genomics big data and the delivery of integrated information to end users, utilizing standardized RNA-seq data from TCGA and GTEx projects [16]. A key innovation of GEPIA2 is its mitigation of sample imbalance by incorporating data from the GTEx project, providing a much larger set of normal tissue samples for robust comparison [16]. Its features allow for the identification of tumor-specific genes, which are often pursued as candidate drug targets [16].

canSAR for Drug Discovery

canSAR is a publicly available, multidisciplinary knowledgebase designed explicitly to support cancer translational research and drug discovery [17]. It stands out for its integration of diverse data types, including structural biology and druggability information, which are critical for assessing the potential of a protein to be modulated by a small-molecule drug or biologic [17].

Integrated Workflow for Target Discovery

The power of these resources is maximized when they are used in a coordinated, sequential workflow for target identification and validation. The following diagram and protocol outline a standard operational pipeline.

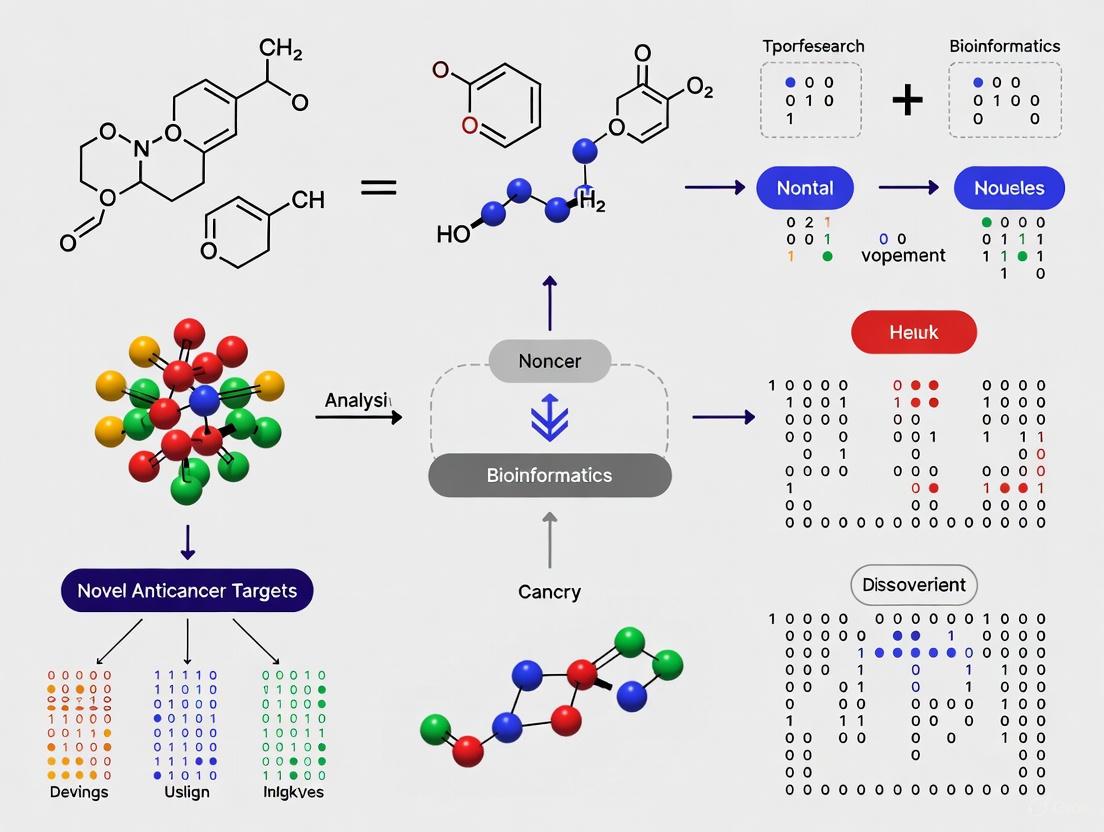

Figure 1: Integrated bioinformatics workflow for anticancer target discovery.

Protocol: A Multi-Database Target Screening Pipeline

This protocol describes a systematic approach to screen for and prioritize novel anticancer drug targets using cBioPortal, GEPIA2, and canSAR.

Step 1: Genetic Alteration Screening with cBioPortal

- Objective: Identify genes frequently altered in a cancer type of interest.

- Method:

- Access cBioPortal (https://www.cbioportal.org/).

- Select a cancer study (e.g., "Pancreatic Cancer (TCGA, PanCancer Atlas)").

- In the "Query" tab, enter a gene list or query a single gene.

- Execute the query and navigate to the "Cancer Types Summary" and "OncoPrint" tabs to visualize the frequency and types of genomic alterations (mutations, copy-number alterations) across the cohort.

- Output: A list of genes with high alteration frequencies, which are potential drivers of oncogenesis [15].

Step 2: Expression and Prognostic Validation with GEPIA2

- Objective: Validate the expression profile and clinical relevance of prioritized genes.

- Method:

- Access GEPIA2 (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/).

- For differential expression analysis, use the "Expression DIY" Boxplot function. Input the gene symbol, select the relevant cancer dataset (e.g., TCGA tumor vs. GTEx normal), and generate a plot to confirm tumor-specific overexpression.

- For clinical relevance, use the "Survival" function. Select the cancer type and generate Overall Survival or Disease-Free Survival plots using the log-rank test. A significant p-value (< 0.05) indicates prognostic value [16].

- Output: Genes that are differentially expressed in tumors and have a significant impact on patient survival.

Step 3: Druggability Assessment with canSAR

- Objective: Evaluate the potential of the validated gene products as druggable targets.

- Method:

- Access canSAR (http://cansar.icr.ac.uk).

- Search for the protein encoded by the validated gene.

- Review the integrated information, including the presence of known bioactive compounds, 3D protein structures, and predicted druggable pockets. A target with existing chemical probes or favorable structural features is more tractable [17].

- Output: A shortlist of high-confidence, druggable target proteins for experimental follow-up.

Successful execution of the bioinformatics workflow and subsequent experimental validation relies on a suite of key reagents and data resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Target Discovery

| Item | Function in Research | Example Sources / Identifiers |

|---|---|---|

| RNA-seq Datasets | Provide the foundational gene expression data for analysis in GEPIA2 and cBioPortal. | TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas), GTEx (Genotype-Tissue Expression) [16] |

| Clinical Annotation Data | Links molecular data to patient outcomes, enabling survival and correlation analyses. | TCGA clinical data files [16] |

| Drug-Target Interaction Databases | Provide information on known drug-target relationships for druggability assessment. | DrugBank [15], ChEMBL [17] |

| Protein Structure Data | Essential for canSAR's structure-based druggability predictions and molecular docking. | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [17] [14] |

| Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Data | Allows for network-level analysis to identify critical nodes as potential targets. | STRING database [14] |

The integration of bioinformatics databases like cBioPortal, GEPIA2, and canSAR has created a powerful, data-driven paradigm for anticancer drug target discovery. cBioPortal illuminates the genomic landscape of cancer, GEPIA2 validates the transcriptional and clinical relevance of candidate genes, and canSAR provides the critical translational bridge by assessing druggability. The structured workflow and toolkit presented in this whitepaper provide researchers with a clear, actionable strategy to navigate the complexity of cancer biology and efficiently prioritize the most promising targets for further experimental development, ultimately accelerating the journey toward novel cancer therapies.

The complexity of cancer biology, driven by tumor heterogeneity, diverse resistance mechanisms, and intricate microenvironment interactions, necessitates a systems-level approach to therapeutic discovery. Multi-omics integration represents a transformative paradigm in bioinformatics research that enables a comprehensive functional understanding of biological systems by combining data from multiple molecular layers [19]. This approach systematically integrates multidimensional data derived from genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and additional omics layers to develop a comprehensive atlas of tumor biological systems [20]. Unlike traditional single-omics analyses that provide limited insights, integrated multi-omics effectively captures cascade regulatory relationships across molecular hierarchies, thereby elucidating network-based mechanisms underlying drug resistance and identifying novel therapeutic vulnerabilities [20] [19].

In the context of anticancer drug target discovery, multi-omics technologies demonstrate distinct advantages by providing unprecedented insights into the molecular drivers of tumorigenesis and treatment resistance [20]. For instance, through the integration of transcriptomic and proteomic approaches, researchers can elucidate how neoplastic cells evade pharmacological interventions by modifying gene expression profiles and altering protein functional states [20]. The systematic integration of metabolomic datasets with systems biology modeling enables comprehensive delineation of molecular pathways underlying therapeutic resistance [20]. This holistic perspective is critical for addressing the fundamental challenge in contemporary oncology where tumor cells intricately regulate complex biological networks to circumvent drug-induced cytotoxic effects [20].

Omics Layers and Their Contributions

A comprehensive multi-omics approach encompasses several core molecular layers, each providing unique insights into cancer biology:

Genomics explores the composition, structure, function, and variations of the genetic material DNA, focusing on mutations, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), and structural variations including copy-number variations (CNVs) that may initiate oncogenic processes [19] [21]. Technologies include whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and whole-exome sequencing (WES), with functional genomics employing RNA interference, siRNA, shRNA, and CRISPR-based screening to validate gene-disease associations [19] [22].

Transcriptomics studies gene transcription and transcriptional regulation at the cellular level, revealing spatiotemporal differences in gene expression through technologies including RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) sequencing, and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) [19] [21]. This layer helps identify genes significantly upregulated or downregulated in tumor tissues, providing candidate targets for targeted therapy [19].

Proteomics enables the identification and quantification of proteins and their post-translational modifications (phosphorylation, glycosylation, ubiquitination), offering direct functional insights into cellular processes and signaling pathways [21]. Mass spectrometry-based methods, affinity proteomics, and protein chips are widely used, with phosphoproteomics revealing novel disease mechanisms [21].

Metabolomics focuses on studying small molecule metabolites (carbohydrates, fatty acids, amino acids) that immediately reflect dynamic changes in cell physiology and metabolic vulnerabilities in tumors [21]. Both untargeted and targeted metabolomics approaches are employed to elucidate mechanisms of disease progression [21].

Public Data Repositories for Multi-Omics Research

Table 1: Major Public Data Repositories for Multi-Omics Cancer Research

| Repository Name | Data Types Available | Cancer Focus | URL |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | RNA-Seq, DNA-Seq, miRNA-Seq, SNV, CNV, DNA methylation, RPPA | >33 cancer types, 20,000+ tumor samples | https://cancergenome.nih.gov/ |

| Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) | Proteomics data corresponding to TCGA cohorts | Various cancer types | https://cptac-data-portal.georgetown.edu/cptacPublic/ |

| International Cancer Genomics Consortium (ICGC) | Whole genome sequencing, somatic and germline mutations | 76 cancer projects, 20,383 donors | https://icgc.org/ |

| Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) | Gene expression, copy number, sequencing, drug response | 947 human cancer cell lines, 36 tumor types | https://portals.broadinstitute.org/ccle |

| Omics Discovery Index (OmicsDI) | Consolidated genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics | Multiple diseases from 11 repositories | https://www.omicsdi.org |

These repositories provide comprehensive molecular profiling data from thousands of tumor samples and cell lines, enabling researchers to access large-scale multi-omics datasets without conducting expensive, time-consuming experimental profiling [23]. The TCGA alone houses one of the largest collections of multi-omics data sets for more than 33 different types of cancer from over 20,000 individual tumor samples, providing rich molecular and genetic profiles that have enabled numerous discoveries about cancer progression, manifestation, and treatment [23].

Methodologies for Multi-Omics Data Integration

Computational Integration Strategies

Integration of multi-omics data presents significant computational challenges due to differences in data scale, noise ratios, preprocessing requirements, and the incomplete correlation between molecular layers [24]. Several computational strategies have been developed to address these challenges:

Matched (Vertical) Integration: Combines different omics data profiled from the same cells or samples, using the cell itself as an anchor for integration. This approach includes matrix factorization methods (MOFA+), neural network-based methods (scMVAE, DCCA, DeepMAPS), and network-based methods (cite-Fuse, Seurat v4) [24].

Unmatched (Diagonal) Integration: Integrates omics data drawn from distinct populations or cells by projecting cells into a co-embedded space to find commonality. Methods include Graph-Linked Unified Embedding (GLUE), which uses graph variational autoencoders to learn how to anchor features using prior biological knowledge [24].

Mosaic Integration: Employed when experimental designs have various combinations of omics that create sufficient overlap. Tools include COBOLT and MultiVI for integrating mRNA and chromatin accessibility data, and StabMap and bridge integration for more complex integrations [24].

Spatial Integration: Addresses the increasing development of spatial multi-omics methods that capture omics data within the confines of a cell or 'spot,' which serves as the integration anchor. Tools like ArchR have been successfully deployed for spatial integration [24].

Analytical Frameworks for Target Discovery

Several specialized analytical frameworks have been developed specifically for drug target identification using multi-omics data:

Transcriptome-Wide Association Studies (TWAS): Integrates GWAS and gene expression data to identify genes contributing to traits or diseases. The FUSION tool establishes precomputed predictive models to test associations throughout the transcriptome [25].

Proteome-Wide Association Studies (PWAS): Adapts the TWAS framework to analyze circulating proteins, identifying proteomic associations with cancer risk [25].

Summary-data-based Mendelian Randomization (SMR): Tests whether the effect of SNPs on cancers is mediated through gene expression, prioritizing causal genes for tumorigenesis. The heterogeneity in dependent instruments (HEIDI) test further determines if associations are attributable to linkage [25].

Bayesian Colocalization: Determines whether genetic associations with both identified genes and cancers share single causal variants, with a posterior probability of H4 (PP.H4) > 0.8 indicating strong colocalization [25].

These methods can be systematically combined into an integrated analytical pipeline for robust target identification, as demonstrated in recent studies that identified 24 genes (18 transcriptomic, 1 proteomic and 5 druggable genetic) showing significant associations with cancer risk [25].

Multi-Omics Data Integration Workflow

Experimental Design and Protocols

Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis Protocol

A comprehensive protocol for integrative multi-omics analysis in anticancer drug target discovery involves multiple coordinated steps:

Step 1: Sample Preparation and Data Generation

- Collect tumor and matched normal tissues from patient cohorts or appropriate cancer cell lines

- Extract DNA for whole-genome or whole-exome sequencing to identify genetic variants

- Isolate RNA for transcriptome sequencing (RNA-seq) to profile gene expression patterns

- Prepare protein lysates for mass spectrometry-based proteomic analysis

- Extract metabolites for metabolomic profiling via LC-MS or GC-MS platforms

- Ensure consistent sample processing across all omics platforms to minimize technical variability [21]

Step 2: Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

- Process genomic data: alignment to reference genome, variant calling, annotation of SNPs, indels, and CNVs

- Process transcriptomic data: read alignment, quantification of gene expression, normalization

- Process proteomic data: peptide identification, quantification, normalization

- Process metabolomic data: peak detection, compound identification, quantification

- Implement rigorous quality control measures specific to each data type [21] [24]

Step 3: Individual Omics Analysis

- Conduct differential expression/abundance analysis for each omics layer

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis on significantly altered molecules

- Identify molecular signatures associated with disease phenotypes or treatment response [25]

Step 4: Multi-Omics Data Integration

- Apply appropriate integration strategy based on data structure

- Implement computational tools for integrated analysis

- Identify concordant and discordant patterns across omics layers [24] [25]

Step 5: Target Prioritization and Validation

- Prioritize candidate targets based on multi-omics evidence

- Validate targets using experimental models (cell lines, organoids, animal models)

- Confirm mechanistic role through functional studies [20] [25]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Multi-Omics Studies

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in Multi-Omics Research |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, PacBio Sequel, Oxford Nanopore | Generate genomic and transcriptomic data at various resolutions and applications |

| Proteomics Platforms | Thermo Fisher Orbitrap mass spectrometers, Bruker timSTOF | Enable high-throughput protein identification and quantification |

| Metabolomics Platforms | Agilent LC/Q-TOF, Sciex Triple Quad systems | Facilitate comprehensive profiling of small molecule metabolites |

| Single-Cell Technologies | 10x Genomics Chromium, BD Rhapsody | Enable single-cell transcriptomic, proteomic, and multi-omic profiling |

| Spatial Omics Technologies | 10x Genomics Visium, NanoString GeoMx | Provide spatial context for transcriptomic and proteomic data |

| CRISPR Screening | Whole-genome CRISPR libraries | Enable functional validation of candidate targets in high-throughput |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Seurat, MOFA+, GLUE, FUSION | Perform data integration, visualization, and analysis across omics layers |

Case Studies in Anti-Cancer Drug Target Discovery

Successful Applications of Multi-Omics Integration

Several recent studies demonstrate the power of multi-omics integration for identifying novel anticancer drug targets:

CLDN18.2 in Gastrointestinal Cancers: Integrative analyses combining pharmaco-omics with genomic and transcriptomic datasets revealed that elevated expression of CLDN18.2 is significantly associated with poor prognosis in bladder cancer (BLCA), esophageal carcinoma (ESCA), and pancreatic adenocarcinoma (PAAD). This comprehensive elucidation of CLDN18.2's biological functions and clinical relevance offered novel insights for the development of targeted therapies [20].

IDO1 in Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Researchers employed proteomics, genomics, and bioinformatics tools to explore the function of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 1 (IDO1) within the tumor microenvironment. Findings indicated that tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) with elevated IDO1 expression contribute to an immunosuppressive TME, thereby reducing immunotherapy effectiveness. Analysis of RNA-seq data from TCGA involving 95 patients, supplemented by clinical validation in 77 patients, demonstrated that targeting IDO1 in TAMs could serve as a viable strategy to counteract immune resistance [20].

PCK2 in Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Integration of transcriptomic and proteomic data revealed the role of mitochondrial PCK2 in NSCLC. Researchers found that PCK2-driven gluconeogenesis helps cancer cells evade mitochondrial apoptosis, indicating that targeting metabolic pathways like gluconeogenesis could be a strategy to combat drug resistance in nutrient-poor tumor environments [20].

NRF2 Pathway in Multiple Cancers: A comprehensive integrative analysis of transcriptomic, proteomic, druggable genetic and metabolomic association studies identified 24 genes significantly associated with cancer risk. Enrichment analysis revealed that these genes were mainly enriched in the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) pathway, highlighting its importance as a therapeutic target across multiple cancer types [25].

Artificial Intelligence in Multi-Omics Target Discovery

AI and machine learning are increasingly transforming multi-omics-based drug target discovery:

Deep Learning Models: Neural networks capable of handling large, complex datasets such as histopathology images or omics data can identify patterns not discernible through traditional statistical methods [26] [22].

Target Identification: AI enables integration of multi-omics data to uncover hidden patterns and identify promising targets. For instance, ML algorithms can detect oncogenic drivers in large-scale cancer genome databases such as TCGA, while deep learning can model protein-protein interaction networks to highlight novel therapeutic vulnerabilities [26].

Drug Design and Optimization: Deep generative models, such as variational autoencoders and generative adversarial networks, can create novel chemical structures with desired pharmacological properties, significantly accelerating the drug discovery process [26].

Companies such as Insilico Medicine and Exscientia have reported AI-designed molecules reaching clinical trials in record times. Insilico developed a preclinical candidate for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in under 18 months, compared to the typical 3-6 years, with similar approaches being applied to oncology [26].

AI in Multi-Omics Target Discovery

Validation and Clinical Translation

Target Validation Workflows

The transition from computationally identified targets to clinically relevant therapeutics requires rigorous validation:

Experimental Validation

- Implement CRISPR-Cas9 knockout technology to quantitatively screen identified target genes individually [19]

- Use RNA interference (RNAi) approaches including small interfering RNA (siRNA) and short hairpin RNA (shRNA) for gene silencing validation [19] [22]

- Conduct functional assays to assess impact on cancer cell proliferation, invasion, metastasis, and treatment resistance

- Validate in multiple model systems including 2D cell cultures, 3D organoids, and animal models

Clinical Correlation

- Analyze target expression in patient cohorts and correlate with clinical outcomes

- Assess target prevalence across cancer subtypes and stages

- Evaluate target druggability using structural biology and chemical screening approaches

Pathway to Clinical Application

Successful translation of multi-omics discoveries to clinical applications involves:

Biomarker Development

- Develop companion diagnostics for patient stratification

- Identify predictive biomarkers of treatment response

- Discover resistance biomarkers to guide combination therapies

Therapeutic Development

- Prioritize targets with genetic support, as they demonstrate higher success rates in clinical trials [25]

- Repurpose existing drugs for new indications based on multi-omics insights

- Develop novel therapeutic modalities including small molecules, biologics, and cell therapies

The integrated approach has already yielded success stories, such as the identification of PCSK9, CCR5 and ACE2 as therapeutic targets for various diseases, highlighting the potential of genetics-driven drug development [25]. In oncology, multi-omics approaches have identified novel targets including CLDN18.2, IDO1, and components of the NRF2 pathway that are currently being evaluated in preclinical and clinical studies [20] [25].

Integrative multi-omics analysis represents a paradigm shift in anticancer drug target discovery, enabling a comprehensive understanding of the complex molecular networks driving tumorigenesis and treatment resistance. By simultaneously interrogating multiple molecular layers - genome, transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome - researchers can identify novel therapeutic vulnerabilities with higher precision and confidence. The continuing evolution of computational integration methods, coupled with advances in AI and machine learning, is further enhancing our ability to extract biologically meaningful insights from these complex datasets. As multi-omics technologies become more accessible and analytical methods more sophisticated, this approach will play an increasingly central role in precision oncology, ultimately leading to more effective, personalized cancer therapies that overcome the limitations of current treatment paradigms.

Identifying Driver Genes, Mutations, and Altered Signaling Pathways

The identification of driver genes, their mutations, and the signaling pathways they disrupt represents a cornerstone of modern precision oncology. Unlike "passenger" mutations, which occur incidentally without functional consequences, driver genetic events are causally implicated in oncogenesis, conferring a selective growth advantage that drives tumor initiation and progression [27]. The systematic discovery of these elements is fundamental to the discovery of novel anticancer drug targets, enabling the development of therapies that specifically target the molecular Achilles' heels of cancer cells [28]. This process is powered by advanced bioinformatics, which provides the computational frameworks necessary to interpret complex multi-omics data and translate genomic alterations into actionable biological insights and therapeutic strategies [29].

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Driver vs. Passenger Mutations

In the genomic landscape of a tumor, driver mutations are those that provide a selective advantage to the cell, promoting its proliferation and survival. These mutations are positively selected during tumor evolution. In contrast, passenger mutations do not confer a growth advantage and are merely carried along as the tumor cell divides. Distinguishing between these two classes is a primary goal of computational cancer genomics [27].

Cancer Driver Genes (CDGs) and Their Impact

Cancer driver genes are the genes harboring driver mutations. They can be further categorized as:

- Oncogenes: These genes promote cancer when mutated to become overly active or expressed. They often function in signaling pathways that stimulate cell growth and division (e.g., KRAS, BRAF). Their activity is typically likened to a stuck accelerator.

- Tumor Suppressor Genes (TSGs): These genes protect against cancer by repairing DNA, controlling cell death, or arresting cell growth. When inactivated by mutation, this protective function is lost (e.g., TP53, PTEN). Their loss is akin to a broken brake [27].

The functional deregulation of crucial molecular pathways via these driver events leads to abnormal gene expression, enabling hallmarks of cancer such as uncontrolled proliferation, resistance to cell death, and metastatic potential [27].

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

The discovery of driver genes relies on high-throughput technologies that generate vast amounts of multi-omics data.

Sequencing Technologies and Their Applications

Table 1: Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Technologies for Cancer Genomics

| Technology | Generation | Key Principle | Primary Application in Driver Discovery | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Second / Third | Sequences the entire genome, including coding and non-coding regions. | Identification of all genetic variants (SNPs, CNVs, structural variations) [29]. | Comprehensive; detects variants in non-coding regulatory regions. | Higher cost and data burden; requires complex analysis. |

| Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Second | Selectively sequences protein-coding exons (~1-2% of the genome). | Discovering coding region mutations, indels, and SNPs linked to disease [29]. | Cost-effective for targeting functional regions; covers ~85% of disease-causing mutations. | Misses non-coding and regulatory mutations. |

| RNA Sequencing (RNA-seq) | Second / Third | Sequences the transcriptome to determine RNA quantity and sequence. | Analyzing gene expression, fusion genes, alternative splicing, and novel transcripts [29]. | Reveals functional consequences of genomic changes; detects expressed fusions. | Does not directly assess genomic alterations. |

Public Data Repositories

Large-scale consortium efforts have generated publicly available datasets that are invaluable for research:

- The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): A comprehensive resource containing multi-omics data (genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, proteomic) for over 20,000 primary cancers across 33 cancer types [27] [28].

- cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics: An open-access platform that provides visualization, analysis, and download of large-scale cancer genomics data sets, including those from TCGA [27] [29].

- Genomic Data Commons (GDC): A unified data repository that enables data sharing across cancer genomic studies [29].

- OncoKB: A precision oncology knowledge base that contains information on the oncogenic effects and therapeutic implications of specific genetic alterations [27].

Computational Methodologies for Identification

A suite of bioinformatics tools and algorithms is required to process raw sequencing data and identify driver events.

Bioinformatic Workflow for Variant Discovery

The standard workflow for identifying somatic mutations from tumor sequencing data involves several key steps:

- Quality Control & Preprocessing: Assessing raw sequencing data quality using tools like FastQC and trimming adapters with Trimmomatic or Cutadapt.

- Alignment: Mapping sequencing reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using aligners such as STAR (for RNA-seq) or BWA (for DNA-seq).

- Variant Calling: Identifying genomic variants (SNPs, indels) relative to the reference genome using tools like GATK (Genome Analysis Toolkit) or MuTect2 for somatic mutations.

- Annotation: Predicting the functional impact of identified variants using tools like ANNOVAR or SnpEff, which cross-reference variants with databases of known genes, pathways, and protein domains [29] [28].

Diagram 1: Somatic Variant Calling Workflow

Advanced Computational Frameworks

Beyond basic variant calling, sophisticated computational methods are needed to distinguish drivers from passengers and to identify genes under positive selection.

a) Frequency-Based and Signal-Based Methods: Early approaches identified driver genes based on their significant mutational frequency across patient cohorts. Newer frameworks, like the one developed by Saad et al., integrate multiple data types. This framework combines genetic mutation, chromosome copy-number, and gene expression data from thousands of tumors to pinpoint genes that drive the loss of specific chromosome arms, a common event in cancer [30].

b) Network and Graph-Based Models: These methods contextualize genes within biological interaction networks (e.g., protein-protein interaction networks) to identify modules or genes whose network properties are perturbed in cancer.

- EMOGI: Integrates multi-omics data with a PPI network using graph convolutional networks (GCNs) to predict CDGs [31].

- SEFGNN (Soft-Evidence Fused Graph Neural Network): A novel framework that treats multiple biological networks (e.g., from STRING, PCNet) as independent evidence sources. It uses GNNs to extract features from each network and employs Dempster-Shafer Theory to perform uncertainty-aware fusion at the decision level, improving the robustness of CDG identification [31].

c) Personalized Driver Prioritization Algorithms (PDPAs): These tools move beyond cohort-level analysis to identify patient-specific driver mutations, which is critical for personalized therapy. A key challenge has been validating these predictions. The TARGET-SL framework addresses this by using PDPA predictions to produce a ranked list of predicted essential genes that can be validated against ground truth data from CRISPR-knockout and drug sensitivity screens [32].

Table 2: Key Bioinformatics Tools for Driver Gene and Biomarker Discovery

| Tool Category | Example Tools | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variant Callers | GATK, MuTect2, STAR | Identify genomic variants from sequenced reads versus a reference genome. | Foundational step in all WGS/WES analyses. |

| Variant Annotation | ANNOVAR, SnpEff | Annotate and predict functional impact of genetic variants. | Prioritizing mutations likely to be drivers. |

| Pathway & Network Analysis | Cytoscape, STRING, IPA, GSEA | Visualize and analyze molecular interaction networks and enriched pathways. | Understanding the functional context of driver genes. |

| Multi-Platform Portals | cBioPortal, Oncomine | Integrate, visualize, and analyze complex cancer genomics data. | Exploratory analysis and validation across datasets. |

| AI/ML Frameworks | SEFGNN, TARGET-SL, scikit-learn | Advanced prediction of driver genes and essentiality using machine learning. | Identifying novel CDGs and patient-specific vulnerabilities. |

Analyzing Altered Signaling Pathways

Once driver genes are identified, the next critical step is to map them onto the signaling pathways they disrupt.

Most Frequently Altered Pathways in Cancer

Pan-cancer analyses of thousands of tumors have revealed a consistent set of core signaling pathways that are deregulated in most cancers. A systemic analysis of TCGA data sorted the top ten most frequently mutated pathways as follows [27]:

- p53 pathway

- RTK-RAS pathway

- Lipid metabolism pathway

- PI-3-Kinase/Akt pathway

- Ubiquitination pathway

- β-catenin/Wnt pathway

- Notch pathway

- Cell cycle pathway

- Homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway

- Splicing pathway

Key Oncogenic Signaling Pathways

The p53 Pathway The TP53 gene, which encodes the p53 protein, is the most frequently altered gene in cancer [27]. p53 functions as a critical tumor suppressor, inducing cell cycle arrest, senescence, or apoptosis in response to cellular stress. Its disruption allows damaged cells to continue proliferating.

Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (RTK)-RAS Pathway This pathway is a central regulator of cell growth, proliferation, and survival. It includes upstream receptors (like EGFR, VEGFR, PDGFR) and downstream effectors such as the RAS-RAF-MAPK cascade. Dysregulation is common in cancers; for example, in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), targeting the VEGFR pathway with agents like bevacizumab is an established therapeutic strategy [33].

PI-3-Kinase/Akt Pathway This pathway is crucial for cell survival and metabolism. Upon activation by RTKs or other signals, PI3K phosphorylates lipids, leading to the activation of Akt, which promotes cell growth and inhibits apoptosis. Somatic mutations in components of this pathway are common in many cancers [27].

Wnt/β-catenin Pathway This pathway regulates cell fate and proliferation. In the absence of a Wnt signal, β-catenin is degraded. Oncogenic mutations, often in CTNNB1 or APC, lead to stabilized β-catenin, which translocates to the nucleus and activates transcription of proliferative genes. This is a key pathway in HCC and colorectal cancer [27] [33].

Diagram 2: Core Cancer Signaling Pathways

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Driver Gene Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Line Models | MCF-7 (breast cancer), K562 (leukemia), A549 (lung cancer) [31] | In vitro models for functional validation of driver genes via genetic manipulation and drug screening. |

| CRISPR Screening Libraries | Genome-wide sgRNA libraries (e.g., Brunello, GeCKO) | High-throughput functional genomics to identify genes essential for cancer cell survival (gene essentiality). |

| Biological Network Databases | STRING, CPDB, PCNet, iRefIndex, Multinet [31] | Provide curated protein-protein interaction data for network-based and GNN-driven driver gene identification. |

| Validated Reference Gene Sets | COSMIC Cancer Gene Census, NCG, CGC, OncoKB [27] [32] [31] | Curated lists of known cancer genes used as gold-standard positives for training and benchmarking computational models. |

| Drug Sensitivity Databases | GDSC (Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer), CTRP (Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal) | Correlate genetic alterations with drug response data to identify predictive biomarkers and therapeutic vulnerabilities. |

Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Targeting

The ultimate goal of identifying driver genes and pathways is to translate these discoveries into effective therapies for cancer patients.

From Driver Mutation to Targeted Therapy

The paradigm of targeted therapy involves developing drugs that specifically inhibit the products of driver genes.

- EGFR mutations in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) predict response to EGFR inhibitors like gefitinib [27] [29].

- BRCA1/2 mutations, which impair homology-directed repair, confer sensitivity to PARP inhibitors due to synthetic lethality [29] [28].

- BRAF V600E mutations in melanoma are targeted by BRAF inhibitors such as vemurafenib.

Pathway-Directed Immunotherapy

There is growing evidence that oncogenic signaling pathways influence the tumor immune microenvironment and response to immunotherapy. For instance, abnormal activation of the Wnt/β-catenin, p53, and PTEN pathways can promote tumor immune escape and resistance to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) like anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies. Therefore, targeting these pathways in combination with immunotherapy represents a promising strategy to overcome resistance [34].

Case Study: Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)

HCC treatment has been revolutionized by targeted therapies and immunotherapies aimed at specific pathways:

- VEGFR Pathway: The combination of the anti-VEGF antibody bevacizumab with the anti-PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab is a first-line standard for advanced HCC, demonstrating how targeting a driver pathway (angiogenesis) can synergize with immunotherapy [33].

- Multiple Kinase Inhibition: Sorafenib and lenvatinib are TKIs that target multiple kinases, including VEGFR, PDGFR, and RAF, effectively inhibiting several nodes in the RTK-RAS-MAPK pathway [33].

The systematic identification of driver genes, mutations, and altered signaling pathways is a fundamental pillar of anticancer drug discovery. This process, powered by ever-advancing bioinformatics tools and multi-omics data integration, has moved from a cohort-level understanding to patient-specific precision. The continued development of sophisticated computational frameworks, such as graph neural networks and personalized essentiality predictors, is dramatically accelerating the discovery of novel therapeutic targets. By mapping the intricate web of dysregulated signaling in cancer cells, researchers can design more effective combination therapies, overcome drug resistance, and ultimately deliver on the promise of precision oncology for improved patient outcomes.

The Role of Network Biology in Understanding Cancer Complexity and Dependencies

The traditional paradigm of targeting single oncogenes has yielded significant breakthroughs in cancer therapy, exemplified by drugs like Imatinib (Gleevec) for chronic myeloid leukemia and Vemurafenib (Zelboraf) for BRAF-mutant melanoma [35]. However, cancer's robust nature arises from complex, interconnected biological networks that allow tumors to adapt and develop resistance to targeted therapies. Network biology represents a paradigm shift that moves beyond this one drug–one target approach to instead model the intricate web of molecular interactions that define cancer phenotypes. By mapping these relationships systematically, researchers can now identify critical vulnerabilities that emerge from the network structure itself—dependencies that are not apparent when studying individual genes or proteins in isolation.

This whitepaper explores how network biology, powered by large-scale functional genomics and computational integration, is transforming the discovery of novel anticancer drug targets. We focus specifically on the foundational frameworks and methodologies that enable researchers to decode cancer complexity and identify therapeutically actionable dependencies within biological networks.

The Dependency Map (DepMap) Initiative: A Foundational Resource

The Cancer Dependency Map (DepMap) initiative represents a large-scale, systematic effort to identify and catalog genetic and molecular vulnerabilities across hundreds of cancer models [36]. The core premise is that the mutations driving cancer cell proliferation and survival simultaneously create unique, cancer-specific dependencies that normal cells lack [37]. These dependencies represent compelling therapeutic targets. DepMap aims to create a comprehensive "map" triangulating relationships between genomic features and these "Achilles' heels" across diverse cancer types through extensive genetic and small molecule perturbation studies [37].

This collaborative, open-science project generates genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screens, RNAi screens, and drug sensitivity profiles across thousands of genetically characterized cancer cell lines [36]. The resulting data is made publicly available through the DepMap portal, providing researchers worldwide with an unprecedented resource for exploring cancer vulnerabilities [37]. The DepMap consortium has demonstrated feasibility for large-scale approaches to pinpoint small molecule sensitivities, working in conjunction with characterization efforts such as the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) to accelerate molecular and therapeutic discovery [36] [37].

Key Technological Platforms and Data Types

Table 1: Core Data Generation Platforms in DepMap

| Platform/Assay | Primary Function | Scale and Coverage | Key Insights Generated |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Screens | Genome-wide knockout to identify essential genes | Hundreds of genome-wide screens across cancer cell lines [36] | Identification of lineage-specific dependencies and pan-essential genes [36] |

| RNAi Screens | Gene knockdown using short hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) | Large-scale compendiums (e.g., Project DRIVE) [36] | Validation of CRISPR findings; identification of synthetic lethal interactions [36] |

| PRISM Drug Screening | High-throughput drug sensitivity testing in pooled cell lines | 1450 drugs across 371 diverse cancer cell lines [38] | Drug response patterns and mechanisms of action [38] |

| Molecular Characterization | Genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic profiling | Integration with CCLE and other characterization efforts [36] [37] | Correlation of dependencies with molecular features for biomarker discovery [36] |

Computational Methodologies for Network-Based Dependency Analysis

Data Processing and Normalization Techniques

The raw data generated from dependency screens requires sophisticated computational processing before meaningful biological insights can be extracted. A critical challenge in CRISPR-Cas9 screens is correcting for copy number-associated false positives, where amplified genomic regions produce increased Cas9 cleavage activity that can be mistaken for true biological essentiality. The CERES algorithm was developed specifically to address this confounder, computationally correcting for copy number effects to improve the specificity of essentiality calls [36]. Similarly, the Chronos algorithm provides a cell population dynamics model that further refines the inference of gene fitness effects from CRISPR screening data [36].

For data analysis and exploration, tools like shinyDepMap provide user-friendly interfaces that allow researchers to identify targetable cancer genes and their functional connections without requiring advanced computational expertise [36]. These normalization methods and accessible tools collectively transform raw screening data into reliable, biologically meaningful dependency scores that accurately reflect gene essentiality across diverse cancer models.

Advanced Computational Tools for Target Discovery

Table 2: Computational Tools for Network Biology in Cancer Research

| Tool/Algorithm | Primary Function | Methodological Approach | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepTarget | Predicts anti-cancer mechanisms of small molecules | Integrates genetic deletion data with drug sensitivity profiles [38] | Drug repurposing; identification of secondary targets and context-specific mechanisms [38] |

| Chronos | Models CRISPR-Cas9 screening data | Cell population dynamics model for improved fitness effect inference [36] | Correction of screen artifacts; accurate essentiality scoring [36] |

| Sparse Dictionary Learning | Identifies pleiotropic effects from fitness screens | Decomposes complex dependency patterns into interpretable components [36] | Discovery of co-functional gene modules; pathway-level analysis [36] |

| Global Computational Alignment | Maps cell line profiles to human tumors | Unsupervised alignment of transcriptional profiles [36] | Assessment of clinical relevance for identified dependencies [36] |

The recently developed DeepTarget tool exemplifies the power of integrating genetic and pharmacological data to understand network perturbations. Unlike conventional approaches that rely primarily on chemical structure and predicted binding affinity, DeepTarget leverages the principle that genetic deletion of a drug's protein target via CRISPR-Cas9 can mimic the drug's inhibitory effects [38]. By analyzing data from 1450 drugs across 371 cancer cell lines, DeepTarget infers mechanistic insights not readily apparent from structural data alone, successfully predicting both primary and secondary drug targets with high accuracy [38].

Experimental Protocols for Dependency Validation

Genome-Scale CRISPR-Cas9 Viability Screens

Objective: To identify genes essential for the proliferation and survival of specific cancer cell lines.

Methodology:

- Library Design: Employ genome-wide lentiviral sgRNA libraries (e.g., Avana or Brunello libraries) targeting ~18,000 genes with multiple sgRNAs per gene to ensure statistical robustness [36].

- Viral Transduction: Transduce cancer cell lines at low multiplicity of infection (MOI ~0.3) to ensure most cells receive a single sgRNA, followed by selection with puromycin.

- Cell Propagation: Culture transduced cells for approximately 2-3 weeks (typically 14-21 population doublings) to allow depletion of cells bearing lethal sgRNAs.

- Sample Collection: Collect genomic DNA at baseline (T0) and endpoint (Tfinal) for sgRNA abundance quantification.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Amplify integrated sgRNA sequences by PCR and sequence using high-throughput platforms. Map sequences to the reference library and quantify abundance changes using specialized algorithms (e.g., CERES or Chronos) that calculate gene-level dependency scores [36].

Key Considerations: Include negative control sgRNAs targeting non-essential genomic regions and positive controls targeting essential genes. Perform computational correction for copy number effects to minimize false positives [36].

High-Throughput Drug Sensitivity Screening (PRISM)

Objective: To profile cancer cell line sensitivities to large compound collections in a multiplexed format.

Methodology:

- Cell Line Barcoding: Label each cell line with unique DNA barcodes that can be detected via quantitative PCR or next-generation sequencing.

- Pooled Screening: Combine barcoded cell lines into pools (typically 10-50 lines per pool) and plate in multiplexed format [36].

- Compound Treatment: Treat pooled cells with individual compounds across a range of concentrations (typically 8-point, 1:3 or 1:4 serial dilutions), including DMSO vehicle controls.

- Incubation and Viability Assessment: Incubate for 3-5 cell doublings (typically 5-7 days), then harvest cells and extract genomic DNA.

- Barcode Quantification: Amplify and sequence unique barcodes to determine the relative abundance of each cell line following compound treatment.

- Data Analysis: Normalize barcode counts to vehicle controls and calculate viability metrics (e.g., AUC or IC50) for each cell line-compound combination.

Key Considerations: The PRISM method enables highly efficient screening of many cell lines against extensive compound libraries, significantly enhancing throughput compared to traditional single-line screens [36].

Visualizing Biological Networks in Cancer Research

Diagram 1: DeepTarget Computational Workflow for Network-Based Drug Target Prediction

Diagram 2: Context-Specific Drug Targeting Revealed Through Network Analysis

Research Reagent Solutions for Network Biology Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Cancer Dependency Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Primary Function | Key Features | Application in Network Biology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome-Wide CRISPR Libraries | Knockout screening for gene essentiality | Multiple guides per gene; optimized for minimal off-target effects [36] | Systematic identification of genetic dependencies across cancer models [36] |

| RNAi Libraries (shRNA) | Gene knockdown studies | Lentiviral delivery; enables stable gene suppression [36] | Validation of CRISPR findings; synthetic lethal interaction studies [36] |

| PRISM Barcoded Cell Lines | Multiplexed compound screening | Unique DNA barcodes for cell line identification in pooled assays [36] | High-throughput drug sensitivity profiling in diverse genetic backgrounds [36] |

| CCLE Molecular Characterization Data | Genomic and molecular annotation | Multi-omics data (genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic) for cell lines [36] | Correlation of dependencies with molecular features for biomarker discovery [36] |

| Chronos Algorithm | Computational analysis of CRISPR screens | Corrects for copy number confounders and screen-specific artifacts [36] | Improved specificity in essentiality calling; accurate dependency mapping [36] |

Case Studies: Network Biology in Action

Ibrutinib Mechanism Elucidation in Lung Cancer

Ibrutinib, an established BTK inhibitor approved for blood cancers, presented a paradox when it demonstrated efficacy in lung cancer models where its canonical target BTK is largely absent. Through network biology approaches integrating dependency mapping and drug sensitivity data, DeepTarget predicted that mutant forms of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) serve as relevant targets in lung tumors [38]. This hypothesis was experimentally validated through collaborative work with Ani Deshpande's laboratory, explaining why Ibrutinib exhibits efficacy in lung cancer despite the absence of its canonical target [38]. This case exemplifies how network approaches can reveal context-specific drug mechanisms and identify novel therapeutic applications for existing drugs.

Phosphate Dysregulation in Ovarian Cancer

A network biology analysis of dependency relationships in ovarian cancer identified a novel vulnerability involving phosphate transport through the XPR1-KIDINS220 protein complex [36]. This dependency represents a non-oncogenic addiction that could be therapeutically exploited. The discovery emerged from systematic analysis of genetic dependencies across cancer lineages, followed by mechanistic studies that delineated the pathway and its critical role in specific ovarian cancer subtypes [36]. This case demonstrates how network approaches can identify non-obvious, therapeutically relevant vulnerabilities beyond traditional oncogenic drivers.

Network biology, powered by systematic dependency mapping and computational integration, is fundamentally transforming our approach to identifying novel anticancer drug targets. By modeling the complex web of molecular interactions within cancer cells, researchers can now identify critical vulnerabilities that emerge from the network structure itself. The DepMap initiative and associated computational tools like DeepTarget provide the foundational resources and methodologies needed to decode this complexity and advance therapeutic discovery.

Looking forward, several key developments will further enhance the impact of network biology in oncology. First, the expansion of dependency mapping to include more diverse cancer models, especially patient-derived organoids and in vivo models, will improve clinical translation. Second, the integration of additional data types, including proteomic, metabolomic, and spatial profiling data, will create more comprehensive network models. Finally, the development of more sophisticated computational methods, particularly artificial intelligence approaches that can predict emergent network properties, will accelerate the identification of targetable dependencies. As these advancements mature, network biology will play an increasingly central role in delivering on the promise of precision oncology by matching patients with therapies that target the specific dependency networks driving their cancer.

Computational Methodologies in Action: From In Silico Prediction to Candidate Prioritization

The discovery of novel anticancer drugs is a formidable challenge, characterized by extensive timelines, substantial financial investment, and high attrition rates [39] [12]. Traditional drug discovery approaches, heavily reliant on in vivo animal experiments and in vitro screening, are often expensive and laborious [40]. In this context, structure-based drug design (SBDD) has emerged as a transformative paradigm, leveraging computational power to streamline and enhance the drug development process [39]. SBDD utilizes the three-dimensional structural information of biological targets to design and optimize therapeutic candidates rationally [41]. Core to this approach are molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which together provide a comprehensive framework for predicting how small molecules interact with target proteins and assessing the stability of these complexes [39].

These computational methods are particularly crucial in oncology, where the complexity and heterogeneity of cancer demand a profound understanding of disease mechanisms at the molecular level [42] [43]. Bioinformatics bridges this gap by enabling the analysis of large-scale multi-omics data—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—to identify novel therapeutic targets and predict new drug candidates [12] [40] [43]. The integration of SBDD with bioinformatics has already facilitated the successful development of several approved cancer therapies, such as Imatinib (Gleevec) for chronic myeloid leukemia and Vemurafenib (Zelboraf) for BRAF-mutant melanoma, demonstrating the tangible impact of these computational approaches [35]. This guide details the core methodologies and protocols of molecular docking and MD simulations, framing them within the strategic pursuit of discovering novel anticancer drug targets.

Molecular Docking: Principles and Methodologies

Molecular docking is a computational structure-based method extensively used since the early 1980s to predict the preferred orientation, conformation, and binding affinity of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target macromolecule (receptor) [12]. Its primary goal is molecular recognition, achieving a complementary fit at the binding site [12]. In anticancer drug discovery, docking is pivotal for virtual screening of large chemical libraries to identify potential lead compounds, thereby saving significant time and experimental resources [39] [12].

A standard molecular docking workflow involves several essential steps, as illustrated in the diagram below.

System Preparation Protocols

The accuracy of molecular docking is profoundly influenced by the careful preparation of both the protein and ligand structures [44] [45].

Protein Preparation: This critical step ensures the protein structure is optimized for docking simulations. Best practices include:

- Adding Hydrogen Atoms: The inclusion of hydrogen atoms leads to better redocking scores and more accurate predictions of binding interactions [44].

- Optimizing Hydrogen Bonds: Networks of hydrogen bonds should be optimized, which may involve flipping the side chains of asparagine, glutamine, and histidine residues to achieve optimal bonding [45].

- Removing Atomic Clashes: Minor steric clashes present in crystal structures must be resolved through restrained energy minimization [45].

- Assigning Partial Charges: The choice of charge models (e.g., Gasteiger-Marsili, MMFF94) can significantly impact docking performance and should be selected based on the force field and system requirements [44].

Ligand Preparation: Small molecules require careful preprocessing to generate accurate and relevant structures:

- Generate 3D Geometries: For ligands lacking 3D coordinates, these must be generated from 1D or 2D representations, ensuring correct stereochemistry [12].

- Assign Bond Orders: Correct bond orders are essential for representing the electronic structure of the molecule accurately [45].

- Generate Tautomers and Ionization States: At physiological pH, ligands can exist as multiple tautomers or ionization states. It is crucial to generate all accessible states, as the correct form can be a key determinant of binding [45].

Docking Execution and Parameters

The docking process consists of two main components: sampling ligand conformations and scoring the resulting poses [12]. Key parameters that influence performance include:

- Search Space Definition: The size and location of the docking search box must encompass the entire binding site. An adequately sized box is necessary for thorough sampling, but excessive size can increase computation time and false positives [44].

- Search Exhaustiveness: This parameter controls the comprehensiveness of the conformational search. Higher exhaustiveness values generally lead to more reproducible results but require greater computational resources [44].

- Ligand Flexibility: The number of rotatable bonds in the ligand directly affects the complexity of the docking simulation. Molecules with fewer torsions typically achieve more accurate docking results [44].

The performance of different docking parameter combinations can be quantitatively assessed by re-docking a known ligand and calculating the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) between the predicted pose and the experimental crystal structure pose. An RMSD of less than 2.0 Å is generally considered a successful prediction [44].

Table 1: Impact of Key Preparation Parameters on Docking Performance [44] [45]

| Parameter | Protocol Option | Impact on Docking Enrichment | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrogen Atoms | Include | Improves redocking scores and interaction predictions | Always add and optimize |

| Partial Charges | Gasteiger-Marsili vs. MMFF94 | Varies by system; can significantly affect binding affinity predictions | Test multiple methods for your target |

| Ligand Tautomers | Generate accessible states | Critical for identifying correct binding pose; neglect degrades enrichment | Generate all probable states at pH 7.4 |

| Search Exhaustiveness | Low (8) vs. High (64) | Higher values improve pose recovery but increase computational time | Use ≥32 for production virtual screening |

| Binding Site Box Size | Small (15Å) vs. Large (25Å) | Oversized boxes reduce performance; appropriately sized boxes improve accuracy | Define based on known active site dimensions |

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

While molecular docking provides a static snapshot of ligand-receptor interactions, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations offer a dynamic view of the behavior and stability of the complex under near-physiological conditions [39]. MD simulations solve Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in the system, tracing their trajectories over time and enabling the study of conformational changes, binding pathways, and allosteric mechanisms that are inaccessible through static approaches [44].

Simulation Setup and Parameters

The accuracy of MD simulations depends critically on proper system setup and parameter selection, as outlined in the workflow below.

System Preparation: