Graph Neural Networks for Cancer Driver Gene Identification: Methods, Applications, and Future Directions

The identification of cancer driver genes is crucial for understanding tumorigenesis and developing targeted therapies.

Graph Neural Networks for Cancer Driver Gene Identification: Methods, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

The identification of cancer driver genes is crucial for understanding tumorigenesis and developing targeted therapies. This article explores the transformative role of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) in advancing this field. We provide a comprehensive overview of how GNNs integrate multi-omics data within biological network structures to overcome limitations of traditional methods. The content covers foundational concepts, cutting-edge methodologies like GCNs, GATs, and GTNs, along with optimization strategies for challenges such as data sparsity and network heterogeneity. Through comparative analysis of state-of-the-art frameworks including CGMega, MLGCN-Driver, and SEFGNN, we demonstrate how GNNs achieve superior performance in driver gene prediction. This resource is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage GNNs for precision oncology applications.

Understanding Cancer Driver Genes and Why GNNs Are a Transformative Approach

The Critical Importance of Identifying Cancer Driver Genes in Precision Oncology

Cancer is a complex and heterogeneous group of diseases driven by somatic mutations that confer a selective growth advantage to tumor cells [1]. Among these genetic alterations, cancer driver genes play a pivotal role in initiating and progressing the disease, distinguishing them from passenger mutations that do not promote cancer development [2] [1]. The accurate identification of these driver genes is fundamental to precision oncology, enabling a deeper understanding of cancer biology and guiding the development of targeted therapies tailored to a patient's unique genetic makeup [2] [3].

The emergence of graph neural networks represents a transformative advancement in computational biology, offering a powerful framework for identifying cancer driver genes by integrating complex, structured biological data [4] [5]. Unlike conventional methods, GNNs can efficiently model multimodal structured information—from molecular structures and biological networks to knowledge graphs—combining the high predictive performance of deep learning with intuitive graph structure representations that naturally align with biological systems [4]. This capability is particularly valuable for precision oncology, where integrating multi-omics data can reveal the intricate molecular interactions underlying cancer progression and treatment responses [2].

The Evolving Landscape of Cancer Genomics

Large-scale genomic studies have dramatically expanded our catalog of cancer driver genes. Recent research analyzing 10,478 cancer genomes across 35 cancer types identified 330 candidate driver genes, including 74 novel genes not previously associated with any cancer [3]. This discovery highlights the substantial genetic complexity of cancer and underscores that a significant proportion of drivers remain undiscovered, presenting both a challenge and an opportunity for therapeutic development.

A key insight from these studies is that cancer development is rarely the consequence of a single gene abnormality but rather reflects a complex interplay of multiple genes organized into functional modules [6]. This systems-level understanding necessitates computational approaches that can move beyond single-gene analysis to decipher the cooperative networks that drive oncogenic processes.

Table 1: Key Statistical Findings from Recent Cancer Genomics Studies

| Study Focus | Dataset Size | Key Finding | Implication for Precision Oncology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pan-cancer driver discovery | 10,478 genomes across 35 cancer types | 330 candidate driver genes identified (74 novel) | Vast potential for new therapeutic targets beyond currently known drivers [3] |

| Mutation distribution | 33 TCGA cancer types | 94.3% of mutations located in coding and non-coding genomic elements | Need for whole-genome approaches rather than exome-only sequencing [1] |

| Clinical actionability | 9,070 samples from 100kGP | ~55% of patients harbor ≥1 clinically relevant mutation | WGS can broaden scope of patients eligible for precision therapies [3] |

| Variant interpretation | 160,969 patients | ~80% of somatic mutations are variants of unknown significance (VUS) | AI methods critical for interpreting the "long tail" of rare mutations [7] |

Graph Neural Networks: A Primer for Cancer Research

Fundamental Concepts

Graph Neural Networks are deep learning models specifically designed to process graph-structured data, which consists of nodes (representing entities) and edges (representing relationships) [5]. In biological contexts, GNNs perform inference by integrating network topology with node features to learn meaningful representations of complex biological systems [8]. Through an iterative process of message passing, GNNs update node states by incorporating information from neighboring nodes, effectively capturing both local topology and global network structure [4] [5].

Comparative Advantage in Biological Applications

GNNs hold particular appeal for cancer research because they naturally represent many biological data types, from molecular structures and spatially resolved images to biological networks and knowledge graphs [4]. This congruence with biological data structures allows GNNs to overcome limitations of conventional deep learning approaches that struggle to capture contextual topological information [4]. Furthermore, GNNs differ fundamentally from traditional probabilistic graphical models like Bayesian networks; while the latter excel at probabilistic reasoning and causal inference under uncertainty, GNNs typically rely on information diffusion techniques like graph convolution to accomplish predictive tasks such as node classification [4].

GNN Architectures for Driver Gene Identification

Several GNN architectures have been specialized for identifying cancer driver genes, each with distinct mechanistic advantages:

Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs)

GCNs operate by aggregating features from a node's direct neighbors along with its own features, capturing local graph structure to learn node representations enriched with neighborhood information [8]. Frameworks like DriverOmicsNet leverage GCNs to integrate multi-omics data using STRING protein-protein interaction networks and correlation-based weighted gene correlation network analysis (WGCNA) [2]. This approach has demonstrated superior predictive accuracy for cancer-related features including homologous recombination deficiency, cancer stemness, and survival outcomes [2].

Graph Attention Networks (GATs)

GATs incorporate attention mechanisms that compute a weight for each neighbor based on feature vectors, allowing the model to assign different importance to contributions from neighboring nodes [6] [8]. This capability is particularly valuable in biological contexts where certain interactions may be more critical than others. The CGMega framework utilizes transformer-based graph attention to predict cancer genes and dissect cancer gene modules, achieving an AUPRC of 0.9140 in cancer gene prediction tasks [6].

Self-Supervised and Advanced GNN Frameworks

Recent innovations address challenges of incomplete and noisy biological networks through self-supervised learning. The SSCI method employs self-supervised graph convolutional networks to enhance network structure, achieving exceptional performance (AUROC: 0.966, AUPRC: 0.964, F1 score: 0.913) in cancer driver gene identification [8]. This approach uses feature masking and denoising to improve model robustness against network incompleteness, a common limitation in protein-protein interaction data [8].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of GNN Architectures in Driver Gene Identification

| GNN Architecture | Representative Framework | Key Innovation | Reported Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) | DriverOmicsNet | Integration of STRING PPI with WGCNA correlation networks | Superior predictive accuracy for HRD, stemness, immune clusters, and survival | [2] |

| Graph Attention Network (GAT) | CGMega | Transformer-based attention with multi-omics integration | AUPRC: 0.9140; outperformed GCN, MTGCN, EMOGI, and MODIG | [6] |

| Self-Supervised GCN | SSCI | Feature masking and denoising for network enhancement | AUROC: 0.966, AUPRC: 0.964, F1: 0.913 | [8] |

| Multi-task GCN | MTGCN | Joint optimization of node prediction and link prediction | AUPRC: 0.907, AUROC: 0.921, F1: 0.822 | [8] |

| Pre-trained GNN | SMG | Pre-training with node masking and reconstruction | AUPRC: 0.942, AUROC: 0.951, F1: 0.876 | [8] |

Application Notes: Experimental Protocols for GNN-Based Driver Gene Identification

Protocol 1: Multi-Omics Integration Using DriverOmicsNet

Principle: Integrate multi-omics data through graph convolutional networks combining prior knowledge from protein-protein interaction networks with data-driven correlation networks [2].

Procedure:

- Data Acquisition and Preprocessing:

- Obtain multi-omics data (mRNA gene expression, CNV, methylation, mutation) from platforms such as UCSC Xena.

- Normalize RNA-Seq expected counts using the voom method from the limma package.

- Process CNV data estimated by GISTIC2, thresholded to discrete values (-2, -1, 0, 1, 2).

- Represent methylation β-values from Illumina HumanMethylation450 array, grouped by genomic context and compressed using autoencoders.

Network Construction:

- Construct a STRING PPI network with genes as nodes and protein interactions as edges.

- Build a complementary correlation network using WGCNA based on gene expression profiles.

- Create a fused network that incorporates both topological structures.

Graph Convolutional Processing:

- Implement a two-component GCN architecture with separate models for STRING and WGCNA networks.

- Perform graph convolution operations that aggregate neighborhood information for each node.

- Generate latent embeddings from both networks and concatenate output vectors for final prediction.

Model Training and Validation:

- Train the model on 15 cancer types comprising 5,555 tumor samples.

- Evaluate using binary classification tasks for homologous recombination deficiency, cancer stemness, immune clusters, tumor stage, and survival outcomes.

- Validate predictive accuracy through cross-validation and comparison with non-graph methods.

Protocol 2: Interpretable Cancer Gene Module Discovery with CGMega

Principle: Dissect cancer gene modules using explainable graph attention networks with integrated multi-omics data, including 3D genome architecture [6].

Procedure:

- Multi-Omics Graph Construction:

- Define nodes representing genes with edges from protein-protein interactions.

- Compute node features by concatenating condensed Hi-C features (from ICE-normalized contact maps), promoter densities of ATAC, CTCF, histone modifications (H3K4me3, H3K27ac), and frequencies of SNVs and CNVs.

- Apply singular value decomposition to normalized Hi-C matrix to obtain condensed spatial features.

Graph Attention Network Implementation:

- Implement a transformer-based graph attention neural network over the multi-omics representation graph.

- Utilize attention mechanisms to weight neighbor contributions during message passing.

- Train the model in a semi-supervised manner for cancer gene prediction.

Model Interpretation with GNNExplainer:

- Apply GNNExplainer to identify compact subgraph structures and feature subsets crucial for predictions.

- Detect cancer gene modules comprising influential genes and their relationships.

- Extract gene-specific important features to characterize functional modules.

Validation and Transfer Learning:

- Evaluate model performance using AUPRC, AUROC, accuracy, and F1 score.

- Implement transfer learning by pre-training on well-studied cancer types (e.g., MCF7 cell line) and fine-tuning on rare cancers with limited labeled data.

- Assess robustness through repeated interpretation runs to ensure module consistency.

Protocol 3: Network Enhancement with Self-Supervised Learning (SSCI)

Principle: Improve cancer driver gene identification by enhancing incomplete and noisy PPI networks through self-supervised graph convolutional networks [8].

Procedure:

- Positive-Unlabeled Learning:

- Apply PU learning algorithm to infer reliable negative samples from unlabeled data.

- Parameterize the PPI network with initial node features.

Dual-Task GCN Training:

- Implement a GCN for node classification using the parameterized network.

- Simultaneously apply feature masking to the parameterized network.

- Employ a second GCN to perform feature denoising and reconstruction.

Network Structure Update:

- Combine denoised features with node classification outcomes.

- Update the PPI network structure iteratively for enhanced representation.

Model Evaluation:

- Validate using five-fold cross-validation repeated 10 times.

- Compare performance against baseline models (GCN, GAT, ChebNet, EMOGI, MTGCN, SMG) using AUROC, AUPRC, and F1 score.

- Assess biological interpretability through enrichment analysis and pathway mapping.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Resources for GNN-Based Driver Gene Identification

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Database | Function in Research Pipeline | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Resources | UCSC Xena Platform | Multi-omics data retrieval and preprocessing | Integrated access to TCGA, GTEx, and other cancer genomics data [2] |

| STRING Database | Protein-protein interaction network construction | Curated and predicted protein interactions with confidence scores [2] | |

| DriverDBv3 | Candidate cancer driver gene identification | Integrative multi-omics database with algorithm-curated drivers [2] [1] | |

| Software Libraries | GNN Frameworks (PyTorch Geometric, DGL) | Graph neural network implementation | Efficient implementations of GCN, GAT, and other graph architectures [6] [8] |

| GNNExplainer | Model interpretation and module detection | Identifies influential subgraphs and features for predictions [6] | |

| Analytical Tools | WGCNA | Correlation network construction | Weighted gene co-expression network analysis for data-driven graphs [2] |

| CHASMplus, BoostDM | Validation of computational predictions | Tumor type-specific driver mutation prediction [7] |

Validation and Clinical Translation

Functional and Clinical Validation Approaches

Validating computational predictions of driver genes requires multiple complementary approaches:

Association with Clinical Outcomes: Recent research has demonstrated that VUSs predicted to be pathogenic by AI methods in genes like KEAP1 and SMARCA4 show significant association with worse overall survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients (N=7,965 and 977 in two cohorts), unlike "benign" VUSs [7]. This real-world validation confirms the biological relevance of computational predictions.

Mutual Exclusivity Analysis: Pathogenic VUSs identified by AI methods exhibit mutual exclusivity with known oncogenic alterations at the pathway level, following established patterns of cancer evolution where driver mutations in the same pathway rarely co-occur [7].

Binding Site Enrichment: Mutations affecting protein binding residues are significantly more likely to be annotated as oncogenic (Fisher's test, q-value = 0, odds ratio = 10.02), and VUSs at these critical functional sites are preferentially classified as pathogenic by computational methods [7].

Integration with Precision Oncology Paradigms

The clinical utility of driver gene identification is demonstrated by the finding that approximately 55% of patients harbor at least one clinically relevant mutation predicting sensitivity or resistance to certain treatments or clinical trial eligibility [3]. This highlights the substantial impact of comprehensive driver gene analysis on personalizing cancer therapy.

Future Directions and Challenges

Despite significant progress, several challenges remain in the application of GNNs for cancer driver gene identification. Network incompleteness and noise in biological interaction data continue to limit model performance, prompting the development of self-supervised and network enhancement approaches [8]. The interpretation of non-coding variants represents another frontier, with methods like geMER developed to identify mutation enrichment regions across both coding and non-coding genomic elements [1].

Future research directions include the development of temporal GNN models that can capture the dynamic evolution of cancer genomes, integration of single-cell multi-omics data for higher-resolution analysis, and the creation of knowledge-infused GNNs that better incorporate existing biological knowledge into deep learning architectures [4] [5]. As these methods mature, their clinical translation will require rigorous validation in real-world settings and demonstration of utility in guiding treatment decisions and improving patient outcomes.

The integration of GNNs into the cancer researcher's toolkit represents a paradigm shift in computational oncology, offering unprecedented capabilities to decipher the complex genetic architecture of cancer and accelerate the development of precision therapies tailored to individual molecular profiles.

The identification of cancer driver genes is paramount for understanding oncogenesis, advancing personalized treatment, and informing drug development strategies. For years, computational methods for this task have predominantly fallen into three categories: mutation frequency-based methods, network-based methods, and conventional machine learning (ML) approaches. While these methodologies have laid a crucial foundation, they possess inherent limitations that can hinder the discovery of novel drivers, particularly those with low mutation frequency or complex functional impacts. With the emergence of graph neural networks (GNNs) as a powerful tool for cancer genomics, it is essential to clearly delineate the shortcomings of these traditional approaches. This application note provides a structured analysis of these limitations, supported by quantitative data and experimental protocols, to guide researchers in selecting and evolving methodologies for driver gene identification.

Quantitative Analysis of Traditional Method Limitations

The table below summarizes the core principles and inherent limitations of the three traditional methodological categories.

Table 1: Core Limitations of Traditional Cancer Driver Gene Identification Methods

| Method Category | Core Principle | Key Limitations | Impact on Driver Identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation Frequency-Based (e.g., MuSigCV, OncodriveCLUST) [9] [10] | Identifies genes with mutation rates significantly higher than a predefined background mutation rate [11]. | Struggles to estimate accurate background rates; fails to identify low-frequency drivers [11] [10]. | Misses rare but functionally important driver genes; biased towards highly mutated genes. |

| Network-Based (e.g., HotNet2, RWRH) [11] [10] | Assumes driver genes are not isolated but occupy key positions in biological networks (e.g., PPI) [10]. | Relies on incomplete/noisy network data; often ignores rich node-specific multi-omics features [11] [10]. | Predictions are constrained by prior network knowledge; limited integration of genomic context. |

| Conventional Machine Learning (e.g., TUSON, LOTUS) [9] [10] | Uses classifiers (SVM, Random Forest) on gene-level multi-omics features to distinguish drivers from passengers. | Treats genes as independent instances, ignoring the relational structure of biological networks [12] [10]. | Fails to capture system-level properties and functional modules, limiting predictive power. |

A critical limitation of frequency-based methods is their reliance on recurrence as a proxy for driver status, which overlooks the variable background mutability of different nucleotides and codons. Research shows that the mutability of a site can vary by over two orders of magnitude due to sequence context and DNA repair mechanisms [13]. Consequently, highly recurring mutations may sometimes reflect regions of high background mutability rather than positive selection in cancer. One study found that driver mutations actually had lower background mutability than passenger mutations, and adjusting for this mutability significantly improved driver prediction [13]. The following table illustrates this concept with quantitative data.

Table 2: Impact of Background Mutability on Mutation Observation (Pan-Cancer Model) [13]

| Category of Codon Substitutions | Mean Mutability | Statistical Significance |

|---|---|---|

| All theoretically possible mutations | 1.34 x 10-6 | Baseline |

| Mutations NOT observed in COSMIC cohort | 1.29 x 10-6 | 3-fold lower than observed mutations (p < 0.01) |

| Mutations OBSERVED in COSMIC cohort | 3.88 x 10-6 | 3-fold higher than unobserved mutations (p < 0.01) |

Experimental Protocols for Evaluating Traditional Methods

To systematically benchmark traditional methods and expose their limitations, the following experimental protocol is recommended.

Protocol: Benchmarking Driver Gene Prediction Methods

Objective: To compare the performance of frequency-based, network-based, and conventional ML methods against a validated ground truth dataset, evaluating their sensitivity in identifying known drivers and their ability to discover novel candidates.

Materials and Reagents:

- Benchmark Datasets: Curated lists of known driver and passenger genes from IntOGen, COSMIC Cancer Gene Census (CGC), and Network of Cancer Genes (NCG) [9] [10].

- Genomic Data: Somatic mutation (e.g., from TCGA, ICGC), gene expression, and DNA methylation data for a cohort of tumors [11] [10].

- Biological Networks: Protein-protein interaction networks from databases like STRING or Pathway Commons [12] [11].

- Software Tools: Implementation of methods like MutSigCV (frequency-based), HotNet2 (network-based), and a Random Forest classifier (conventional ML).

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: For the frequency-based approach, calculate the non-silent mutation frequency for each gene and normalize by gene length and background mutation model. For the ML approach, compile a feature matrix for each gene including mutation frequency, copy number variation, and epigenetic features.

- Method Execution:

- Frequency-Based: Run MutSigCV (or similar) to identify genes with significant mutation recurrence.

- Network-Based: Run HotNet2 on the PPI network using mutation scores as input to identify significantly mutated subnetworks.

- Conventional ML: Train a Random Forest classifier using the curated benchmark dataset to predict driver genes based on the multi-omics feature matrix.

- Performance Evaluation:

- Calculate standard metrics (Precision, Recall, F1-Score, AUC-ROC) for each method against the held-out ground truth dataset.

- Pay specific attention to the recall of drivers with low mutation frequency.

- Perform a comparative analysis of the top-ranked genes from each method, noting discrepancies and investigating false positives/negatives.

Expected Outcome: The benchmark will likely reveal that frequency-based methods miss low-frequency drivers, network methods are constrained by the quality of the underlying network, and conventional ML models fail to leverage network topology, resulting in inferior performance compared to modern GNNs that integrate these data types [12] [11] [10].

The Logical Pathway from Traditional Limitations to GNN Solutions

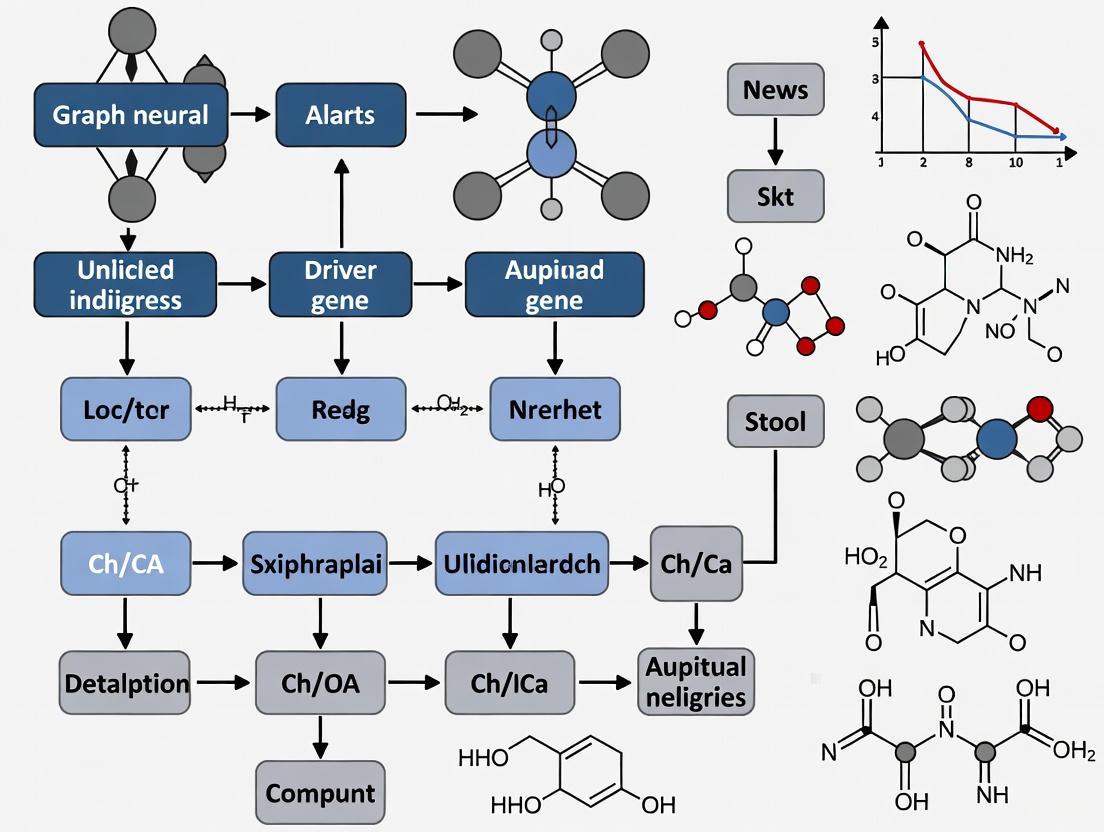

The limitations of traditional methods create a logical impetus for the adoption of graph neural networks. The following diagram illustrates this conceptual transition and the core advantages of the GNN paradigm.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources for implementing and benchmarking cancer driver gene identification methods.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Driver Gene Identification

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Relevance to Method Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| COSMIC Census (CGC) [10] [14] | Database | Curated list of genes with documented roles in cancer (ground truth). | Serves as a gold-standard benchmark for validating and comparing prediction methods. |

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [9] [11] | Data Repository | Provides multi-omics data (genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics) for thousands of tumors. | Primary source for feature extraction (mutation rates, expression) and cohort analysis. |

| STRING / Pathway Commons [12] [11] | Biological Network Database | Provides protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks and pathway information. | Used as the underlying graph structure for network-based and GNN methods. |

| MSK-IMPACT Cohort [13] | Clinical Sequencing Dataset | A large cohort of patients prospectively sequenced using a targeted gene panel. | Useful for validating the recurrence and clinical relevance of predicted driver mutations. |

| Node2Vec [11] | Algorithm | Learses node embeddings that capture topological features of a network. | Used in some GNN methods (e.g., MLGCN-Driver) to incorporate structural information. |

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) represent a specialized class of deep learning architectures designed to process data structured as graphs. In biological contexts, this capability is particularly valuable as many fundamental entities—from molecular structures to cellular systems and ecological networks—are naturally represented as graphs consisting of nodes (entities) and edges (relationships). GNNs operate through message-passing mechanisms, where nodes aggregate and combine feature information from their local neighborhoods in the graph, allowing them to learn complex relational patterns and dependencies within the network [15].

The application of GNNs in biology, especially in oncology, has seen rapid growth due to their ability to integrate and reason over multimodal, structured data. Biological networks are inherently non-Euclidean, meaning they contain complex relational patterns that conventional deep learning architectures like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) struggle to process effectively without losing topological information. GNNs address this limitation by preserving and leveraging the graph structure during learning, making them uniquely suited for tasks such as cancer driver gene identification, where biological context and interaction patterns are critical for accurate prediction [16] [15].

GNN Architectures for Biological Data

Several GNN architectures have been developed, each with distinct mechanisms for processing graph-structured information. The table below summarizes the primary architectures relevant to biological network analysis.

Table 1: Key GNN Architectures in Biological Research

| Architecture | Core Mechanism | Key Biological Applications | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) | Spectral graph convolution using normalized adjacency matrix [16] | Node classification, Graph-level prediction [11] | Efficient and simple; can suffer from over-smoothing in deep layers |

| Graph Attention Network (GAT) | Multi-head self-attention to weight neighbor node importance [17] [16] | Protein-protein interactions, Spatial omics [18] | Allows for differentiable weighting of neighbor contributions |

| Graph Autoencoder (GAE) | Encoder-decoder framework for graph representation learning [16] | Network reconstruction, Feature imputation | Learses compressed latent representations of graph structure |

| Graph Isomorphism Network (GIN) | Summation of neighbor features with learnable parameters [18] | Graph classification tasks | Provably as powerful as the Weisfeiler-Lehman graph isomorphism test |

In practice, these architectures are often adapted or combined to address specific biological challenges. For instance, multi-layer GCNs with initial residual connections and identity mappings have been developed to capture information from high-order neighbors in biological networks while mitigating the common issue of feature over-smoothing [11]. Similarly, multi-head attention mechanisms in GATs enable models to capture different types of relationships between biological entities, such as diverse gene-gene interactions within a protein-protein interaction network [17].

Application Protocol: Cancer Driver Gene Identification

A primary application of GNNs in computational oncology is the identification of cancer driver genes—genes whose mutations confer selective growth advantage to cancer cells. The following section outlines a detailed protocol for implementing this analysis, based on state-of-the-art methodologies.

The diagram below illustrates the end-to-end workflow for a GNN-based driver gene identification pipeline, synthesizing elements from multiple established methods.

Diagram 1: GNN driver gene identification workflow

Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Multi-omics Data Collection

- Somatic Mutation Data: Obtain non-silent single nucleotide variant (SNV) data from genomic databases such as The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) or the International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC). Calculate mutation frequency by dividing the number of non-silent SNVs by the exon gene length for each cancer type [11].

- Gene Expression Data: Acquire RNA-seq data from tumor and normal samples. Compute the differential expression level of each gene as log₂ fold change in tumor expression relative to normal samples, then average across all samples for each cancer type [11].

- DNA Methylation Data: Collect methylation array data (e.g., Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation450). Quantify differential DNA methylation through the average of methylation signals between tumor and normal samples [11].

- System-Level Features: Incorporate additional gene characteristics from tools like sysSVM2, which capture global properties including gene duplication, essentiality, tissue expression patterns, and network topological properties [11].

Biological Network Construction

- Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks: Source from databases such as STRING (PPNet), which contains experimentally validated and predicted interactions with confidence scores [11].

- Pathway Networks: Compile from KEGG and Reactome pathways (PathNet) to capture functional relationships between genes participating in shared biological processes [11].

- Gene-Gene Interaction Networks: Extract from repositories like the Encyclopedia of RNA Interactomes (GGNet) to include regulatory relationships [11].

Feature Engineering Protocol

Topological Feature Extraction with node2vec

- Installation: Implement the node2vec algorithm using available Python packages (e.g., node2vec in PyPI).

- Parameter Configuration: Set the return parameter (p) to 1.0 and the in-out parameter (q) to 0.5 to balance breadth-first and depth-first search strategies. These values have demonstrated effectiveness in capturing meaningful topological features from biological networks [11].

- Random Walk Execution: Perform random walks of length 80 for each node, generating 10 walks per node to sufficiently sample the network neighborhood.

- Embedding Training: Train the node2vec model using Word2Vec with a vector dimension of 128, resulting in a 128-dimensional topological feature vector for each gene.

Biological Feature Vector Construction

- Feature Concatenation: For each gene, concatenate the multi-omics features (somatic mutation, gene expression, DNA methylation) with system-level features to form a comprehensive biological feature vector. In pan-cancer studies, this typically results in a 58-dimensional vector (48 molecular features + 10 system-level features) [11].

- Feature Normalization: Apply Z-score normalization to each feature dimension to ensure consistent scales across different data types.

GNN Model Implementation: MLGCN-Driver

The MLGCN-Driver framework employs a dual-pathway architecture to integrate both biological and topological features [11].

Multi-Layer GCN with Residual Connections

- Graph Convolution Layers: Implement multiple graph convolutional layers with the following propagation rule:

- Each layer incorporates initial residual connections, adding some original node features to the transformed features to preserve information from earlier layers.

- Apply identity mapping by adding an identity matrix to the weight matrix at each layer to stabilize training and mitigate over-smoothing.

Dual-Pathway Architecture:

- Biological Feature Pathway: Process the biological feature vector through a multi-layer GCN to learn representations informed by both node features and network structure.

- Topological Feature Pathway: Process the node2vec-generated topological features through a separate multi-layer GCN to capture higher-order structural patterns.

Prediction Fusion: Combine outputs from both pathways using a weighted average, where the weight hyperparameter is optimized during cross-validation. This fusion leverages complementary information from both feature types.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of GNN Methods for Driver Gene Identification

| Method | Architecture | AUC | AUPRC | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLGCN-Driver | Multi-layer GCN with residual connections [11] | 0.923 (PPNet) | 0.191 (PPNet) | Captures high-order network features |

| GTCM | GCN + Transformer with cross-attention [19] | Not specified | Not specified | Dynamically learns connections between feature sets |

| EMOGI | GCN with multi-omics integration [11] | 0.905 (PPNet) | 0.173 (PPNet) | Incorporates genomic, epigenomic, and transcriptomic data |

| MTGCN | Multi-task GCN with topological features [11] | 0.902 (PPNet) | 0.175 (PPNet) | Integrates biological and topological features |

Model Training and Evaluation

Training Configuration

- Optimization: Use the Adam optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001 and weight decay of 5e-4 for regularization.

- Loss Function: Employ binary cross-entropy loss for the driver gene classification task.

- Training Framework: Implement a nested cross-validation strategy, with outer loops for performance estimation and inner loops for hyperparameter optimization to prevent overfitting and ensure robust performance assessment [18].

Evaluation Metrics

- Area Under ROC Curve (AUC): Measures overall classification performance across all possible thresholds.

- Area Under Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC): Particularly important for imbalanced datasets where driver genes represent a small minority of all genes.

- Cross-Validation: Perform patient-level or sample-level hold-out splits to avoid information leakage and ensure realistic performance estimation [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function in GNN Analysis | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | TCGA, ICGC, COSMIC [11] | Sources of multi-omics data and validated driver gene mutations | Publicly available portals with controlled access |

| Biological Networks | STRING, KEGG, Reactome, RNA Interactomes [11] | Provide structured interaction data for graph construction | Publicly available databases |

| Software Libraries | PyTorch Geometric [17] | Specialized deep learning for graph-structured data | Open-source Python library |

| Benchmark Datasets | Pan-cancer dataset (16 cancer types) [11] | Standardized data for model training and comparison | Derived from TCGA and other public sources |

| Implementation Code | GitHub repositories (e.g., Bioreaction-Variation Network) [17] | Reference implementations and model architectures | Publicly available code repositories |

Advanced GNN Applications in Oncology

Beyond driver gene identification, GNNs are being applied to increasingly complex problems in cancer research. In spatial omics analysis, GNNs model tissue architecture by representing individual cells as nodes and spatial proximity as edges. While these spatial models do not always outperform single-cell or pseudobulk representations for simple classification tasks like tumor grading, they capture biologically meaningful features such as tumor-grade-specific cell-type interactions and complex immune infiltration patterns in colorectal cancer [18].

The learned graph embeddings from these models often reveal clinically relevant patterns beyond their original training objectives. For instance, GNNs processing spatial omics data from breast cancer samples have been shown to recapitulate the sequential ordering of tumor grades (1, 2, and 3) in their embedding space, even when trained only with categorical classification loss. These embeddings also correlate with patient survival outcomes, demonstrating their ability to capture prognostically significant biological information [18].

Graph Neural Networks represent a powerful paradigm for biological network analysis, particularly in the context of cancer driver gene identification. By effectively leveraging both the topological structure of biological networks and rich multi-omics node attributes, GNNs enable more accurate and biologically informed predictions than traditional methods. The protocols outlined in this article provide a foundation for implementing GNN-based approaches, while the emerging applications highlight the expanding potential of these methods in oncology research. As GNN methodologies continue to evolve, they are poised to play an increasingly central role in extracting meaningful patterns from complex biological systems.

The Unique Advantage of GNNs for Integrating Multi-Omics Data in Biological Context

The identification of cancer driver genes (CDGs) represents a fundamental challenge in oncology research, essential for understanding cancer mechanisms and developing targeted therapies [11] [20]. Traditional computational methods for CDG identification often face significant limitations, including an inability to capture the complex, non-linear relationships across different biological layers and high-order network features [11]. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as a transformative solution to these challenges, providing a powerful framework for integrating heterogeneous multi-omics data within their native biological context [21] [22].

Biological systems inherently operate as complex networks, with molecules such as genes, proteins, and metabolites interacting through intricate pathways and regulatory mechanisms [22]. GNNs are uniquely suited to model these systems because they can directly process graph-structured data, preserving the relational information between biological entities that conventional machine learning methods often disregard [21]. By representing multi-omics data as biological networks where nodes correspond to molecular entities and edges represent their functional relationships, GNNs enable a more holistic analysis that captures both within-omics and cross-omics dependencies critical for accurate cancer driver gene identification [23].

The message-passing mechanism inherent to GNNs allows them to aggregate information from a node's local neighborhood in the biological network, effectively capturing the functional context of genes within pathways, protein complexes, and regulatory systems [21]. This capability is particularly valuable for identifying CDGs with low mutation frequencies but significant network influence, which traditional frequency-based methods often miss [11]. Furthermore, GNN architectures can be designed to integrate diverse omics layers—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and epigenomics—while maintaining the biological interpretability essential for translational research [24] [23].

Technical Advantages of GNNs for Multi-Omics Integration

Capturing High-Order Network Relationships

Conventional methods for cancer driver gene identification typically utilize shallow network architectures that limit their ability to capture information from high-order neighbors in biological networks [11]. GNNs address this limitation through deep architectures that propagate information across multiple network layers, enabling the model to learn from genes that are topologically distant but functionally related in the network. For instance, the MLGCN-Driver method employs multi-layer GCNs with initial residual connections and identity mappings to learn biological features while mitigating the over-smoothing problem common in deep GNN architectures [11].

The ability to capture these extended network relationships is crucial because cancer driver genes often exert their influence through complex pathways and functional modules rather than in isolation [22]. Methods like MLGCN-Driver additionally employ node2vec algorithm to extract topological structure features of the biological network, further enhancing the model's capacity to represent the complex relational patterns in omics data [11].

Modeling Cross-Omics Interactions

Unlike traditional integration approaches that either concatenate omics data early in processing or model omics separately before late-stage integration, advanced GNN frameworks explicitly model the interactions between different omics types [23]. The SynOmics framework, for example, employs bipartite graph convolutional networks (BGCN) to capture regulatory interactions between different omics layers, such as miRNA-mRNA targeting relationships [23].

This cross-omics modeling capability allows GNNs to identify coordinated signals across genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic layers that would be obscured in single-omics analyses. By constructing biologically meaningful networks in the feature space rather than relying solely on sample similarity networks, GNNs can capture fundamental biological mechanisms such as gene regulation and pathway dependencies that exist independently of individual samples [23].

Handling Data Heterogeneity and Complexity

Multi-omics data presents significant challenges in terms of heterogeneity, high-dimensionality, and noise [25]. GNNs provide several advantages for handling these challenges:

- Structured Data Representation: Knowledge graphs offer an elastic and scalable model for representing multi-relational biological information, organizing diverse omics data into entities (nodes) and their relationships (edges) [21] [25].

- Dimensionality Reduction: The message-passing mechanism in GNNs effectively reduces the feature dimensions by leveraging correlation structures in the data, enabling analysis of thousands of genes using hundreds of samples [24].

- Robustness to Noise: Approaches like SpaMI incorporate contrastive learning strategies that build corrupted graphs by randomly shuffling features while maintaining topological structure, making the models more robust to data noise [26].

Table 1: Comparative Performance of GNN Methods in Cancer Driver Gene Identification

| Method | Architecture | Key Features | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLGCN-Driver [11] | Multi-layer GCN | Initial residual connections, identity mappings, node2vec for topological features | Excellent performance in AUC and AUPRC on pan-cancer datasets |

| SEFGNN [20] | Multi-network fusion with DST | Dempster-Shafer theory for decision-level fusion, Soft Evidence Smoothing | Outperforms state-of-the-art baselines across three cancer datasets |

| deepCDG [27] | Deep GCN with attention | Shared-parameter GCN encoders, attention-based feature integration, residual connections | Effective predictive performance, robustness, and computational efficiency |

| EMOGI [11] | GCN with multi-omics features | Incorporates genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic data as gene features | Superior accuracy in predicting driver genes across diverse cancers |

| SGCD [11] | GCN with representation separation | Bimodal feature extractor, separate topological and multi-omics feature capture | Improved prediction accuracy through specialized architecture |

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol 1: Knowledge Graph Construction for Multi-Omics Data

Purpose: To create a structured biological knowledge graph that integrates multiple omics data types for downstream GNN analysis.

Materials:

- Multi-omics datasets (somatic mutations, gene expression, DNA methylation, proteomics)

- Biological network databases (STRING, KEGG, Reactome, Pathway Commons)

- Graph database platform (Neo4j or similar)

- Computational resources for data processing

Procedure:

Data Collection and Preprocessing

- Collect multi-omics data from sources such as TCGA, ICGC, or COSMIC [11]

- For each cancer type, calculate mutation frequency by dividing the number of non-silent SNVs by exon gene length

- Compute differential DNA methylation through average methylation signals between tumor and normal samples

- Determine differential expression levels using log2 fold change in tumor expression relative to normal samples [11]

- Normalize datasets to account for platform-specific technical variations

Biological Network Integration

Knowledge Graph Assembly

- Define nodes for each biological entity (genes, proteins, metabolites, pathways)

- Establish edges representing biological relationships (interactions, regulations, participations)

- Incorporate quantitative attributes (z-scores, expression values) as node properties [25]

- Implement hierarchical structure by organizing nodes into communities by tissue, cancer type, or gene family [25]

Validation and Quality Control

- Verify graph connectivity and biological consistency

- Cross-reference with established biological knowledge

- Ensure proper mapping between different identifier systems

Diagram 1: Knowledge graph construction workflow for multi-omics data integration.

Protocol 2: GNN Implementation for Cancer Driver Gene Identification

Purpose: To implement and train a graph neural network model for identifying cancer driver genes from multi-omics data.

Materials:

- Constructed biological knowledge graph

- Deep learning framework (PyTorch Geometric or Deep Graph Library)

- GPU acceleration resources

- Model interpretation tools (GNNExplainer, Integrated Gradients)

Procedure:

Graph Data Preparation

- Format knowledge graph into appropriate structure for GNN processing

- Create feature matrices for nodes using multi-omics data

- Generate adjacency matrices representing biological relationships

- Split data into training, validation, and test sets with appropriate stratification

GNN Model Architecture Setup

- Implement graph convolutional layers with appropriate aggregation functions

- Configure multi-layer architecture with residual connections to prevent over-smoothing [11]

- Incorporate attention mechanisms for adaptive feature integration [28]

- Design output layer for binary classification (driver vs. passenger genes)

Model Training and Optimization

- Initialize model parameters with appropriate strategy

- Define loss function suitable for imbalanced genomic data

- Implement training loop with forward and backward propagation

- Apply regularization techniques to prevent overfitting

- Monitor performance metrics (AUC, AUPRC) on validation set

Model Interpretation and Validation

- Apply GNNExplainer to identify important subgraphs for predictions [27]

- Use integrated gradients method to attribute prediction importance to input features [24]

- Validate identified driver genes against known cancer genes databases

- Perform biological pathway enrichment analysis on high-confidence predictions

Diagram 2: GNN architecture for cancer driver gene identification with interpretation components.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources

| Category | Specific Resource | Function in Analysis | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-omics Data | Somatic Mutations | Identifies genetic alterations in tumors | TCGA, ICGC, COSMIC [11] |

| Gene Expression | Measures transcript abundance and differential expression | RNA-seq datasets [11] | |

| DNA Methylation | Profiles epigenetic modifications | Methylation arrays [11] | |

| Proteomics Data | Quantifies protein abundance and post-translational modifications | Mass spectrometry data [24] | |

| Biological Networks | Protein-Protein Interactions | Maps physical and functional interactions between proteins | STRING database [11] |

| Pathway Databases | Provides curated biological pathways and processes | KEGG, Reactome [11] [24] | |

| Gene Regulatory Networks | Captures transcriptional regulatory relationships | Pathway Commons [24] | |

| Computational Tools | GNN Frameworks | Implements graph neural network architectures | PyTorch Geometric, DGL [11] |

| Interpretation Tools | Explains model predictions and identifies important features | GNNExplainer [27], Integrated Gradients [24] | |

| Graph Databases | Stores and queries biological knowledge graphs | Neo4j [25] |

Case Studies and Performance Evaluation

MLGCN-Driver for Pan-Cancer Driver Gene Identification

The MLGCN-Driver framework demonstrates the application of multi-layer graph convolutional networks for cancer driver gene identification across multiple cancer types [11]. In their implementation, the researchers constructed biomolecular networks from three different sources: a pathway network (PathNet) with 7,699 nodes and 92,710 edges, a gene-gene interaction network (GGNet) with 11,309 nodes and 621,988 edges, and a protein-protein interaction network (PPNet) with 11,473 nodes and 285,843 edges [11].

Each gene was represented by 58-dimensional multi-omics features, including 48-dimensional molecular features (somatic mutation, DNA methylation, and gene expression across 16 cancer types) and 10-dimensional system-level features capturing global gene characteristics [11]. The model employed two key technical innovations: (1) initial residual connections that add original features to each GCN layer to prevent over-smoothing, and (2) identity mappings that add an identity matrix to the weight matrix in each layer to preserve feature distinctness [11].

Experimental results demonstrated that MLGCN-Driver achieved excellent performance in terms of area under the ROC curve (AUC) and area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC) when compared with state-of-the-art approaches [11]. The method's ability to capture high-order network features and mitigate the smoothing of driver gene features by neighboring non-driver genes contributed significantly to its improved performance.

GNNRAI for Alzheimer's Disease Biomarker Discovery

While focused on Alzheimer's disease rather than cancer, the GNNRAI framework provides valuable insights into explainable GNN approaches for multi-omics integration [24]. This method leveraged prior knowledge from Alzheimer's disease biological domains (biodomains), which are functional units in the transcriptome/proteome reflecting AD-associated endophenotypes [24].

In their implementation, each sample was represented as multiple graphs structured by biodomain knowledge graphs from the Pathway Commons database [24]. The framework employed GNN-based feature extractors to process omics data coupled with these biological priors, producing low-dimensional embeddings that were then aligned across data modalities and integrated using a set transformer [24].

A key advantage of this approach was its ability to handle incomplete multi-omics measurements, avoiding reduction in statistical power that plagues many integration methods [24]. The researchers applied integrated gradients to identify predictive features, resulting in the identification of nine well-known and eleven novel AD-related biomarkers among the top twenty candidates [24]. In validation experiments, GNNRAI increased validation accuracy by 2.2% compared to MOGONET, demonstrating the value of incorporating biological prior knowledge directly into the graph structure [24].

SpaMI for Spatial Multi-Omomics Integration

The SpaMI framework addresses the unique challenges of integrating spatial multi-omics data sequenced from the same tissue section [26]. This approach is particularly relevant for understanding tumor microenvironments and spatial heterogeneity in cancer tissues.

SpaMI employs a graph convolutional network-based model that extracts features using a contrastive learning strategy for each omics type and integrates different omics through an attention mechanism [26]. The model constructs a spatial graph with each spot as a node and edges based on spatial coordinates, then uses a contrastive learning approach similar to deep graph infomax (DGI) to capture spatially dependent patterns [26].

In validation experiments on both simulated and real spatial multi-omics datasets, SpaMI demonstrated superior performance in identifying spatial domains and data denoising compared to state-of-the-art methods including Seurat, MOFA+, and SpatialGlue [26]. Quantitative metrics including adjusted Rand index (ARI), adjusted mutual information (AMI), normalized mutual information (NMI), and homogeneity score consistently showed SpaMI's advantage, particularly under increasing levels of Gaussian noise [26].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of GNN Methods Across Applications

| Application Domain | Method | Key Metrics | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer Driver Gene Identification | MLGCN-Driver [11] | AUC, AUPRC | Excellent performance on pan-cancer and cancer-specific datasets |

| SEFGNN [20] | Ranking stability, novel CDG discovery | Outperforms baselines across three cancer datasets | |

| EMOGI [11] | Prediction accuracy | Shows superior accuracy across diverse cancers | |

| Neurodegenerative Disease | GNNRAI [24] | Prediction accuracy, biomarker discovery | 2.2% accuracy improvement over MOGONET, identifies novel biomarkers |

| Spatial Multi-omics | SpaMI [26] | ARI, AMI, NMI, Homo | Superior spatial domain identification, robust to noise |

| General Multi-omics Integration | SynOmics [23] | Classification accuracy | Consistently outperforms state-of-the-art methods |

The application of GNNs for multi-omics integration in biological contexts, particularly cancer driver gene identification, continues to evolve with several promising research directions. Future methodological developments will likely focus on enhancing model interpretability through advanced explanation frameworks, incorporating temporal dynamics to model disease progression, and improving scalability to handle increasingly large and complex multi-omics datasets [22].

The integration of knowledge graphs with Graph RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) approaches presents a particularly promising avenue for addressing current limitations in multi-omics analysis [25]. This combination enables more transparent reasoning chains, improves retrieval precision, and provides better contextual depth by explicitly representing biological relationships [25]. As noted in recent research, GraphRAG can enhance semantic search by combining entity-aware graph traversal with semantic embeddings, facilitating connections between genes, pathways, clinical trials, and drug targets that are difficult to achieve with text-only retrieval [25].

Another significant direction involves the development of more sophisticated multi-view learning approaches that can effectively integrate complementary information from diverse biological networks without introducing conflicting information. Methods like SEFGNN, which employs Dempster-Shafer Theory for uncertainty-aware fusion at the decision level rather than enforcing feature-level consistency, represent important steps toward this goal [20].

In conclusion, GNNs provide unique advantages for integrating multi-omics data in biological contexts by directly modeling the network structure of biological systems, capturing both within-omics and cross-omics interactions, and enabling biologically interpretable model predictions. As these methods continue to mature and incorporate more sophisticated biological prior knowledge, they hold tremendous promise for advancing cancer research, identifying novel therapeutic targets, and ultimately improving patient outcomes through more precise molecular characterization of disease mechanisms.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are revolutionizing cancer driver gene identification research by providing a powerful framework for analyzing structured, multimodal biological data. The predictive performance of these models is intrinsically linked to the biological networks upon which they are built. These networks—Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI), gene Regulatory, and patient Similarity networks—provide the foundational graph topology that enables GNNs to learn meaningful biological representations through message passing and information diffusion. The selection and construction of these networks directly influence a model's ability to capture the complex functional relationships, regulatory mechanisms, and phenotypic patterns essential for accurate cancer gene identification. This protocol examines the three principal biological networks used in GNN applications for oncology research, detailing their construction, implementation, and performance characteristics to guide researchers in selecting appropriate network infrastructures for specific cancer genomics investigations.

Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Networks

Definition and Biological Rationale

Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks represent physical associations between proteins as graph structures, where nodes correspond to proteins and edges represent their documented or predicted interactions. The fundamental premise for using PPIs in cancer driver gene identification stems from the "guilt-by-association" principle, where proteins causing related phenotypes tend to interact with one another. Since cancer driver genes often function within coordinated pathways and protein complexes rather than in isolation, PPI networks provide crucial contextual information for identifying genes with driver potential, even those with low mutation frequencies that might be missed by frequency-based methods alone [11].

PPI networks are typically constructed using experimentally validated or computationally predicted interactions from public databases. The STRING database is frequently utilized, providing both physical and functional associations with confidence scores [29]. For cancer-specific applications, researchers often filter interactions based on co-expression, co-functionality, co-subcellular localization, or co-tissue expression to enhance biological relevance and reduce noise [11]. In the GNNMutation framework, researchers constructed a heterogeneous graph structure where patients and proteins represent distinct node types, connected by edges based on mutations in the patient's DNA that affect the corresponding proteins [29].

Protocol: Constructing a PPI Network for GNN Analysis

- Data Acquisition: Download protein interaction data from STRING, BioGRID, or HPRD databases

- Confidence Filtering: Apply a confidence score threshold (e.g., STRING score > 0.7) to retain high-quality interactions

- Gene Product Mapping: Map interacting proteins to their corresponding coding genes

- Cancer Context Filtering (Optional): Filter interactions present in relevant tissues or cancer types

- Network Formatting: Convert to appropriate format for GNN input (e.g., adjacency matrix or edge list)

Table 1: Key PPI Databases for Cancer GNN Applications

| Database | Interaction Types | Coverage | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| STRING | Physical, Functional | Comprehensive | General PPI context [29] |

| BioGRID | Physical, Genetic | Experimentally validated | High-confidence networks [11] |

| HPRD | Curated physical | Human-specific | Human cancer studies |

| Pathway Commons | Pathway-based | Pathway-oriented | Functional module identification |

GNN Implementation and Performance

PPI networks have been successfully implemented in various GNN architectures for cancer gene identification. The EMOGI framework utilizes PPI networks with multi-omics features to predict cancer driver genes, demonstrating superior accuracy compared to methods that don't incorporate network information [11]. The CGMega framework employs a transformer-based graph attention network over a multi-omics representation graph where edges are defined as PPIs between genes, achieving an AUPRC of 0.9140 in cancer gene prediction on MCF7 breast cancer cells [6]. The MLGCN-Driver method utilizes multi-layer graph convolutional networks on PPI networks with initial residual connections and identity mappings to learn biological multi-omics features, effectively capturing high-order network features for improved driver gene identification [11].

Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs)

Definition and Biological Rationale

Gene Regulatory Networks (GRNs) represent directed causal relationships between transcription factors and their target genes, capturing the hierarchical control mechanisms that coordinate cellular processes. In cancer research, GRNs are particularly valuable because tumor cells frequently exhibit deregulated transcriptional programs that facilitate uncontrolled growth and proliferation. The reconstruction of GRNs in tumors enables researchers to identify master regulatory genes whose inhibition may specifically target cancer cells while sparing normal tissues [30] [31]. Unlike PPIs that represent physical associations, GRNs capture directional regulatory influences, making them particularly suited for identifying upstream driver events in carcinogenesis.

GRN inference typically utilizes perturbation-based gene expression data, where genes are systematically knocked down or overexpressed and the transcriptional consequences are measured genome-wide. The L1000 dataset, which contains approximately 1000 gene perturbations across multiple cancer cell lines, represents a valuable resource for large-scale GRN construction [30]. However, these datasets often suffer from low signal-to-noise ratios, necessitating specialized preprocessing pipelines. Researchers have developed subset-selection algorithms that progressively remove the least informative genes based on signal-to-noise ratios until a sufficiently informative subset remains for accurate GRN inference [30].

Computational methods for GRN inference include:

- Least Squares with Cut-off (LSCO): Demonstrates superior accuracy and computational efficiency for GRN inference from noisy data [30]

- LASSO Regression: Provides sparse network solutions but may underperform compared to LSCO on particularly noisy datasets [30]

- Multi-layer Joint Graphical Models: Enable estimation of both common and cancer-type-specific regulatory components across multiple cancer types [32]

Table 2: GRN Inference Methods and Applications

| Method | Algorithm Type | Key Features | Cancer Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| LSCO | Regression with thresholding | Handles noisy data effectively | L1000 cancer cell line analysis [30] |

| Multi-layer Joint Graphical Model | Sparse regularized decomposition | Identifies shared and unique components | Pan-cancer regulatory mechanism discovery [32] |

| RNI (Robust Network Inference) | Bayesian | Incorporates prior knowledge | Context-specific network inference |

| CLR (Context Likelihood) | Information-theoretic | Identifies significant pairwise relationships | Large-scale network reconstruction |

GNN Implementation and Performance

While GRNs have traditionally been used with non-GNN approaches, recent research has begun incorporating regulatory information into graph neural network frameworks. The systematic assessment of GRN utility for predicting gene essentiality in cancer has yielded important insights; one comprehensive study found that mRNA abundance generally outperforms GRN-inferred activity in predicting sensitivity to gene inhibition in cancer cell lines across ten cancer types [31]. This suggests that careful consideration is needed when incorporating GRNs into predictive models for cancer gene identification.

The multi-layer joint graphical model represents an advanced approach for GRN analysis in cancer, decomposing each cancer-type-specific network into three components: globally shared, partially shared, and cancer-type-unique components [32]. This decomposition enables researchers to explore heterogeneous similarities between different cancer types while revealing regulatory mechanisms unique to each cancer type, providing a more nuanced understanding of pan-cancer and cancer-specific regulatory architectures.

Patient Similarity Networks

Definition and Biological Rationale

Patient Similarity Networks (PSNs) represent patients as nodes, with edges connecting patients who share similar molecular profiles based on multi-omics data. These networks leverage the principle that patients with similar molecular characteristics may share common disease mechanisms, treatment responses, and clinical outcomes. In cancer research, PSNs enable a personalized approach to driver gene identification by contextualizing molecular alterations within specific patient subgroups, facilitating the discovery of patient-specific or subtype-specific driver genes [29]. This approach is particularly valuable given the known heterogeneity of cancer, where different patients may exhibit distinct driver mechanisms despite similar clinical presentations.

PSNs are typically constructed from comprehensive multi-omics data, including somatic mutations, gene expression, DNA methylation, and other molecular profiles. The construction process involves:

- Feature Selection: Identifying informative molecular features across omics layers

- Similarity Calculation: Computing pairwise similarity metrics between patients (e.g., cosine similarity, Euclidean distance)

- Network Sparsification: Applying thresholds to retain only the most significant connections

In the GNNMutation framework, researchers created a heterogeneous graph structure where patient nodes are connected to protein nodes based on mutations in the patient's DNA, enabling simultaneous learning from both patient-specific mutations and general protein interaction knowledge [29]. This innovative approach represents a fusion of PSN and PPI network principles.

Protocol: Building Patient Similarity Networks

- Data Collection: Aggregate multi-omics data (mutations, expression, methylation) for patient cohort

- Feature Vector Creation: Create concatenated feature vectors for each patient

- Similarity Matrix Computation: Calculate pairwise similarity using appropriate metrics

- Threshold Application: Retain edges for similarity scores above predetermined cutoff

- Network Validation: Ensure network connectivity reflects known clinical subgroups

GNN Implementation and Performance

GNNs applied to PSNs can capture complex relationships between patients that may not be apparent through conventional clustering approaches. These models perform message passing between similar patients, allowing information about driver gene potential to propagate through the network based on molecular similarity. The heterogeneous graph approach used in GNNMutation, which combines patients and proteins in a unified graph structure, demonstrates high capacity for distinguishing between cancer cases and control groups across breast, prostate, lung, and colon cancers [29].

PSN-based GNN approaches offer particular advantages for:

- Identifying rare driver genes: By aggregating signal across similar patients

- Personalized driver gene prioritization: Generating patient-specific predictions

- Cancer subtype discovery: Revealing molecularly defined subgroups with distinct drivers

Comparative Analysis of Network Performance

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The three biological network types exhibit distinct performance characteristics in GNN applications for cancer driver gene identification. The following table summarizes quantitative performance metrics reported across recent studies:

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Biological Networks in GNN Applications

| Network Type | Reported Performance | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPI Networks | AUPRC: 0.9140 (CGMega) [6] | Biological context, functional interpretation | Static representation, tissue context absence |

| Regulatory Networks | Varies by method and data quality [30] | Directional causality, mechanistic insights | Inference challenges, noise sensitivity |

| Patient Similarity Networks | Effective case-control discrimination [29] | Personalization, accounts for heterogeneity | Cohort-dependent, requires large sample sizes |

Integration Approaches for Enhanced Performance

Leading-edge GNN frameworks increasingly integrate multiple network types to leverage their complementary strengths. The CGMega framework combines PPI networks with multi-omics features including 3D genome architecture, epigenomic profiles, and mutation patterns to achieve state-of-the-art performance in cancer gene prediction [6]. Similarly, MLGCN-Driver employs multi-layer GCNs that learn from both biological features and network topological features, using a weighted fusion approach to combine predictions from both streams [11].

The emerging trend toward heterogeneous graph structures represents a particularly promising direction, as exemplified by GNNMutation's approach of connecting patient nodes to protein nodes within a unified graph [29]. This architecture naturally integrates elements of PPI networks and patient similarity principles, enabling more comprehensive modeling of the complex relationships between molecular entities and patient phenotypes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Resources for Network-Based GNN Cancer Research

| Resource | Type | Function in Analysis | Representative Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| STRING Database | PPI Repository | Provides protein interaction network data | Network edge definition [29] |

| L1000 Dataset | Perturbation Data | Gene expression responses to perturbations | GRN inference [30] |

| UK Biobank | Patient Data | Whole exome sequencing and clinical data | Patient similarity networks [29] |

| TCGA/ICGC | Multi-omics Repository | Pan-cancer molecular and clinical data | Feature engineering and validation [11] |

| GNNExplainer | Interpretation Tool | Identifies influential subgraphs and features | Model interpretation [6] |

| Node2Vec | Algorithm | Extracts network topological features | Feature enhancement [11] |

The selection of biological networks represents a critical design decision in GNN applications for cancer driver gene identification. PPI networks provide valuable functional context and have demonstrated strong performance in multiple frameworks. Regulatory networks offer directional, mechanistic insights but require careful inference from noisy data. Patient similarity networks enable personalized approaches that account for cancer heterogeneity but depend on cohort size and composition. The most promising future direction involves the continued development of heterogeneous graph structures that integrate multiple network types and data modalities, potentially leading to more comprehensive and accurate models for identifying cancer driver genes across diverse populations and cancer types. As these methodologies mature, attention to model interpretability and biological validation will remain essential for translating computational predictions into clinically actionable insights.

GNN Architectures and Implementation Strategies for Driver Gene Identification

The identification of cancer driver genes is paramount for understanding tumorigenesis, progression, and for developing targeted therapies. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as powerful tools for this task, capable of integrating complex, structured biological data—such as molecular interaction networks and multi-omics features—to identify genes critical for cancer development [4] [33]. Unlike traditional methods that often rely on mutation frequency alone, GNNs can capture the context of genes within biological networks, leading to more accurate and nuanced predictions [11]. This note details the application of three predominant GNN architectures—Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN), Graph Attention Networks (GAT), and Graph Transformer Networks (GTN)—in cancer driver gene identification, providing structured performance data, experimental protocols, and key research reagents.

Architectures: Application Notes and Protocols

Graph Convolutional Network (GCN)

Application Notes: GCNs operate by aggregating features from a node's local neighbors, applying a spectral-based convolution to learn node representations within a graph. In cancer genomics, they excel at integrating multi-omics data with prior biological network knowledge, such as Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) networks, to predict driver genes [33] [11]. A key strength is their ability to leverage both node features (e.g., genomic data) and the graph structure simultaneously.

Quantitative Performance: Table 1: Performance of GCN-based Models in Driver Gene Identification

| Model | Application | Dataset | Key Metric | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDGCN [33] | Personalized Driver Gene Identification | TCGA ACC & KICH | AUROC (ACC) | 0.848 |

| AUROC (KICH) | 0.823 | |||

| MLGCN-Driver [11] | Pan-Cancer Driver Gene Identification | TCGA Pan-Cancer (PPNet) | AUROC | 0.906 |

| AUPRC | 0.616 | |||

| GCN (Baseline) [34] | ER Status Prediction | TCGA BRCA | AUROC | 0.9581 |

| GCN2 [35] | Cancer Driver Gene Identification | STRING PPI Network | Balanced Accuracy | 0.807 ± 0.035 |

Experimental Protocol for GCN-based Driver Gene Identification (e.g., MLGCN-Driver [11]):

- Data Preparation:

- Node Features: Compile a 58-dimensional feature vector for each gene, including somatic mutation frequency, differential DNA methylation, differential gene expression from 16 TCGA cancer types, and system-level features (e.g., gene essentiality, network topology).

- Graph Structure: Construct a biomolecular network (e.g., a PPI network from STRING) where nodes represent genes and edges represent interactions.

- Labels: Define positive labels using known driver genes from databases like CGC and NCG.

- Model Training:

- Employ a multi-layer GCN architecture with initial residual connections and identity mappings to prevent over-smoothing.

- Use the Node2Vec algorithm to extract additional topological features from the network.

- Train the model using a semi-supervised or supervised learning approach with a binary cross-entropy loss function to predict the probability of a gene being a driver gene.

- Validation:

- Evaluate model performance using Area Under the ROC Curve (AUROC) and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC) on held-out test sets.

- Perform cross-validation on multiple biological networks (PathNet, GGNet, PPNet) to ensure robustness.

Diagram 1: GCN workflow for driver gene identification.

Graph Attention Network (GAT)

Application Notes: GATs introduce an attention mechanism that assigns learned, differential importance to each neighbor during feature aggregation [34]. This is particularly powerful in biological systems where not all interactions are equally salient. For instance, in predicting a patient's specific driver genes, GATs can identify which neighboring genes in a PPI network most significantly influence the prediction, enhancing both performance and interpretability [36].

Quantitative Performance: Table 2: Performance of GAT-based Models in Cancer Analysis

| Model | Application | Dataset | Key Metric | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| omicsGAT [34] | ER Status Prediction | TCGA BRCA | AUROC | 0.9636 |

| PR Status Prediction | TCGA BRCA | AUROC | 0.9065 | |

| TN Status Prediction | TCGA BRCA | AUROC | 0.9611 | |

| MSL-GAT [36] | Bladder Cancer Prediction | TCGA BLCA | Accuracy | 97.72% |

| CGMega [6] | Cancer Gene Prediction | MCF7 Cell Line | AUPRC | 0.9140 |

| AUROC | 0.9630 |

Experimental Protocol for GAT-based Analysis (e.g., omicsGAT [34]):

- Graph Formulation:

- Construct a graph where nodes represent patient samples or genes.

- Build edges between nodes based on sample similarity metrics (e.g., correlation) or known biological interactions (e.g., PPI).

- Model Architecture:

- Implement a multi-head graph attention layer. This allows the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces.

- For each node, the layer computes a weighted sum of its neighbors' features, where the weights (attention coefficients) are learned by a shared attentional mechanism.

- The final node embeddings are used for downstream tasks like cancer subtype classification or survival prediction.

- Outcome Prediction & Interpretation: