From In Silico to In Vitro: A Practical Guide to Validating Computational Drug Predictions with Experimental IC50 Data

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating computational drug activity predictions with experimental IC50 values.

From In Silico to In Vitro: A Practical Guide to Validating Computational Drug Predictions with Experimental IC50 Data

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating computational drug activity predictions with experimental IC50 values. It covers the foundational role of IC50 in drug discovery, explores advanced machine learning and virtual screening methodologies for prediction, addresses common pitfalls and optimization strategies in model validation, and presents robust frameworks for comparative analysis. By synthesizing recent advances and best practices, this resource aims to bridge the gap between computational forecasts and experimental confirmation, ultimately enhancing the reliability and efficiency of the drug discovery pipeline.

The Cornerstone of Efficacy: Understanding IC50's Role in Modern Drug Discovery

In pharmacological research and drug discovery, the Half Maximal Inhibitory Concentration (IC50) serves as a fundamental quantitative measure of a substance's potency. Defined as the concentration of an inhibitor needed to reduce a specific biological or biochemical function by half, IC50 provides critical information for comparing drug efficacy, optimizing therapeutic candidates, and understanding biological interactions [1]. While seemingly a simple numerical value, IC50 embodies profound biochemical and clinical significance, bridging the gap between in vitro assays and in vivo therapeutic applications. Within the context of validating computational predictions with experimental data, IC50 values provide the essential empirical ground truth against which predictive models are tested and refined, forming a critical feedback loop in modern drug discovery pipelines.

Biochemical Foundation of IC50

Definition and Distinction from Related Metrics

IC50 is a potency measure that indicates how much of a particular inhibitory substance is required to inhibit a given biological process or biological component by 50% in vitro [1]. The biological component can range from enzymes and cell receptors to entire cells or microbes. It is crucial to distinguish IC50 from other common pharmacological metrics:

- IC50 vs. Kd: While IC50 measures functional inhibition, the dissociation constant (Kd) measures binding affinity between two molecules. Kd indicates how tightly a drug binds to its target, with lower values indicating stronger binding [2].

- IC50 vs. EC50: EC50 (half maximal effective concentration) represents the concentration of an agonist required to achieve 50% of its maximum effect, thus measuring activation rather than inhibition [1] [2].

A key biochemical consideration is that IC50 values are assay-specific and depend on experimental conditions, whereas Ki (inhibition constant) represents an absolute value for binding affinity [1]. The relationship between IC50 and Ki can be described using the Cheng-Prusoff equation for competitive inhibitors, demonstrating how IC50 depends on substrate concentration and the Michaelis constant (Km) [1].

The pIC50 Transformation

The transformation of IC50 to pIC50 (negative logarithm of IC50) offers significant advantages for data analysis and interpretation [3]. This conversion aligns with the logarithmic nature of dose-response relationships and facilitates more intuitive data comparison.

Table: IC50 to pIC50 Conversion Examples

| IC50 Value (M) | IC50 Value (Common Units) | pIC50 Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 × 10⁻⁶ | 1 μM | 6.0 |

| 1 × 10⁻⁹ | 1 nM | 9.0 |

| 3.7 × 10⁻³ | 3.7 mM | 2.43 |

The pIC50 scale provides a more linear representation of potency relationships, where higher values indicate exponentially more potent inhibitors [1] [3]. This transformation enables straightforward averaging of replicate measurements and eliminates common errors associated with geometric means of raw IC50 values [3].

Experimental Methodologies for IC50 Determination

Established and Emerging Assay Technologies

Multiple experimental approaches exist for determining IC50 values, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and appropriate applications.

Table: Comparison of IC50 Determination Methods

| Method | Key Principle | Throughput | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Measures binding-induced refractive index changes on sensor surface [4] | Medium | Label-free, provides kinetic parameters (ka, kd) [4] | Direct ligand-receptor interactions |

| Electric Cell-Substrate Impedance Sensing (ECIS) | Monitors impedance changes as indicator of cell viability/behavior [5] | Medium to High | Real-time, non-invasive, label-free [5] | Cell viability, cytotoxic compounds |

| In-Cell Western | Quantifies target protein expression/phosphorylation in intact cells [6] | High | Physiological relevance, multiplex capability [6] | Cellular target engagement |

| Colorimetric Assays (e.g., MTT, CCK-8) | Measures metabolic activity via tetrazolium salt reduction [7] | High | Simple, affordable, well-established [7] | General cell viability screening |

| Traditional Whole-Cell Systems | Functional response measurement in cellular environment [4] | Variable | Physiological context, functional output [4] | Pathway-specific inhibition |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: SPR-Based IC50 Determination

Surface Plasmon Resonance has emerged as a powerful technique for determining interaction-specific IC50 values, particularly useful for characterizing inhibitors of protein-protein interactions [4]. The following protocol outlines the key steps for SPR-based IC50 determination:

Surface Preparation: Immobilize anti-Fc antibody onto a CM5 sensor chip using standard amine-coupling chemistry. This surface serves as a capture platform for Fc-tagged receptors [4].

Receptor Capture: Inject receptor-Fc fusion proteins over the experimental and reference flow channels. Maintain low surface loading (approximately 200-300 response units) to minimize mass transport artifacts and steric hindrance [4].

Binding Analysis: For direct binding characterization, inject different concentrations of the ligand (e.g., BMP-4) over flow channels loaded with receptors or inhibitors. Use high flow rates (50 μL/min) to reduce mass transport limitations [4].

Inhibition Assay: Pre-incubate a fixed concentration of ligand (e.g., 60 nM BMP-4) with varying concentrations of the inhibitor. Inject these mixtures over the receptor-coated surfaces [4].

Data Analysis:

- Fit binding data to appropriate models (e.g., 1:1 Langmuir binding with mass transport limitation) using software such as BiaEvaluation.

- Generate inhibition curves by plotting response versus inhibitor concentration at a specific time point (e.g., 150 seconds into association phase).

- Calculate IC50 values using nonlinear regression in software such as GraphPad Prism [4].

Diagram 1: SPR-based IC50 determination workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful IC50 determination requires specific reagents and materials tailored to the chosen methodology:

Table: Essential Reagents for IC50 Determination

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Receptor-Fc Fusion Proteins | Capture molecule for SPR surfaces | Provides defined binding partner for ligands [4] |

| Anti-Fc Antibody | Immobilization agent for capture-based assays | Anchors Fc-tagged receptors to sensor surfaces [4] |

| Gold-Coated Nanowire Array Sensors | Nanostructured sensing platform | Enhances sensitivity in SPR imaging [7] |

| Poly-L-lysine | Surface coating for cell adhesion | Promotes cell attachment in impedance-based assays [5] |

| AzureSpectra Fluorescent Labels | Detection reagents for in-cell Western | Enables multiplex protein quantification [6] |

| CM5 Sensor Chips | SPR sensor surfaces with carboxymethyl dextran | Standard platform for biomolecular interaction analysis [4] |

Data Quality and Comparability Considerations

The use of public IC50 data presents significant challenges due to variability between assays and laboratories. Statistical analysis of ChEMBL IC50 data reveals that mixing results from different sources introduces moderate noise, with standard deviation of public IC50 measurements being approximately 25% larger than that of Ki data [8]. Key factors affecting IC50 comparability include:

- Assay conditions (e.g., substrate concentration for enzymes)

- Cell line characteristics for cellular assays

- Measurement timing and endpoint determination

- Laboratory-specific protocols and data normalization methods

Statistical filtering of public IC50 data has shown that approximately 93-94% of initial data points may be removed when applying rigorous criteria for independent measurements, author non-overlap, and error removal [8]. This highlights the importance of careful data curation when integrating IC50 values from public databases for computational model training.

IC50 in Computational Validation: Closing the Loop

The critical role of IC50 in computational prediction validation is exemplified by deep learning approaches such as DeepIC50, which integrates mutation statuses and drug molecular fingerprints to predict drug responsiveness classes [9]. In such frameworks, experimental IC50 values serve as the fundamental ground truth for training and validating predictive models. The performance of these models (e.g., AUC of 0.98 for micro-average in GDSC test set) demonstrates the predictive power achievable when computational approaches are firmly anchored to experimental IC50 data [9].

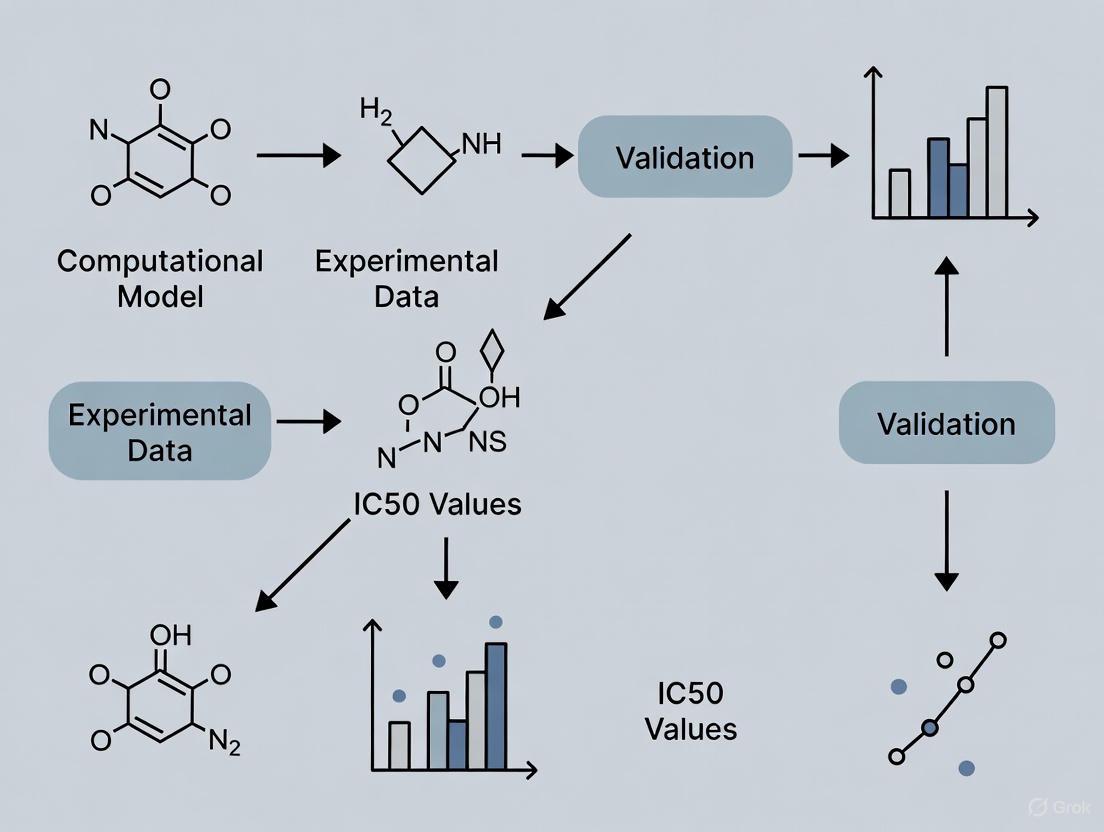

Diagram 2: IC50 in computational-experimental feedback loop.

Clinical Significance and Therapeutic Applications

Beyond the research laboratory, IC50 values inform critical decisions in therapeutic development and clinical practice. In oncology drug discovery, for example, lower IC50 values indicate higher potency, enabling efficacy at lower concentrations and reducing potential systemic toxicity [10]. The clinical relevance is particularly evident in heterogeneous cancers like gastric cancer, where computational prediction of IC50 values helps identify potential responders to targeted therapies like trastuzumab, even when biomarker expression is limited [9].

The transition from IC50 to pIC50 improves clinical decision support by providing a more intuitive scale for comparing compound potency across different therapeutic classes and experimental conditions [3]. This transformation facilitates clearer communication between research scientists and clinical development teams, ultimately supporting more informed choices in candidate selection and therapeutic optimization.

IC50 represents far more than a simple numerical output from laboratory experiments. Its proper determination, statistical treatment, and contextual interpretation form the foundation of robust drug discovery and development. As computational approaches increasingly integrate heterogeneous IC50 data for predictive modeling, understanding the biochemical nuances and methodological considerations underlying this fundamental metric becomes ever more critical. Through continued refinement of experimental protocols, appropriate data transformation, and careful consideration of assay context, researchers can ensure that IC50 values fulfill their essential role in bridging computational predictions with experimental reality in pharmacological research.

In modern drug discovery, computational predictions provide powerful tools for identifying potential therapeutic candidates. However, these in silico methods must be rigorously validated through experimental ground-truthing to ensure their reliability and translational value. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50), a quantitative measure of a compound's potency, serves as a critical benchmark for this validation, bridging the gap between theoretical predictions and biological reality. This guide compares the performance of computational approaches against experimental IC50 validation, providing researchers with a framework for robust drug development.

The Computational-Experimental Divide: A Case Study

A 2024 study on flavonoids from Alhagi graecorum provides a clear example of the essential partnership between computation and experiment. Researchers combined molecular docking and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations with in vitro tyrosinase inhibition assays to evaluate potential inhibitors [11].

- Computational Predictions: Molecular docking simulations showed all five tested flavonoids binding to tyrosinase's active site. MD simulations further analyzed the stability of these complexes, with Compound 5 exhibiting the most favorable binding energy calculations and the lowest predicted binding free energy (as per MM/PBSA analysis) [11].

- Experimental Validation: The in vitro assays provided the ground-truth data, measuring the actual IC50 values. The results confirmed Compound 5 as the most potent inhibitor, correlating with the computational predictions and thereby validating the model [11].

This case underscores that while computational tools can efficiently prioritize candidates, experimental IC50 determination remains the definitive step for confirming biological activity.

Quantitative Comparison: Computational Predictions vs. Experimental IC50

The following table summarizes key findings from recent studies that directly compare computational predictions with experimentally determined IC50 values.

Table 1: Case Studies Comparing Computational Predictions with Experimental IC50 Values

| Study Focus | Computational Method(s) | Key Prediction | Experimental IC50 (Validation) | Correlation & Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids as Tyrosinase Inhibitors [11] | Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Compound 5 had the most favorable binding energy and interactions. | Compound 5 showed the most potent (lowest) IC50. | Strong correlation; computational ranking matched experimental potency. |

| Piperlongumine in Colorectal Cancer [12] | Molecular Docking, ADMET Profiling | Strong binding affinity to hub genes (TP53, AKT1, etc.). | 3 μM (SW-480 cells) and 4 μM (HT-29 cells). | Validation successful; induced apoptosis and modulated gene expression as predicted. |

| SARS-CoV-2 Mpro Inhibitors [13] | Protein-Ligand Docking (GOLD), Semiempirical QM (MOPAC) | Poor predictive power for binding energies across 77 ligands. | Compared against reported IC50 values. | Initial poor correlation; improved after refining the ligand set and method (PM6-ORG). |

Essential Protocols for IC50 Validation

This protocol is critical for validating potential anti-pigmentation or anti-melanoma agents.

- Objective: To determine the IC50 value of a compound against the tyrosinase enzyme.

- Principle: The assay measures the rate of enzymatic conversion of L-tyrosine to L-DOPA and subsequently to dopaquinone, which polymerizes to form melanin. Inhibitors reduce this reaction rate.

- Key Reagents:

- Purified tyrosinase enzyme.

- L-tyrosine or L-DOPA substrate.

- Test compounds (e.g., isolated flavonoids).

- Phosphate buffer (pH 6.8).

- Spectrophotometer.

- Procedure:

- Prepare serial dilutions of the test compound.

- Pre-incubate the compound with tyrosinase in buffer.

- Initiate the reaction by adding the substrate (L-tyrosine/L-DOPA).

- Measure the absorbance change per unit time (e.g., at 475 nm for dopaquinone) using a spectrophotometer.

- Calculate the percentage inhibition for each concentration relative to a control (no inhibitor).

- Plot percentage inhibition vs. log(concentration) and calculate the IC50 value using non-linear regression.

This protocol evaluates a compound's cytotoxicity and potency in a more complex, cellular context.

- Objective: To determine the IC50 value of a compound for inhibiting the growth or viability of specific cancer cell lines.

- Principle: The assay measures a compound's ability to kill cells or inhibit their proliferation, typically after 48-72 hours of exposure.

- Key Reagents:

- Cancer cell lines (e.g., SW-480 and HT-29 for colorectal cancer).

- Cell culture media and supplements.

- Test compound.

- Cell viability assay kit (e.g., MTT, MTS, or PrestoBlue).

- Microplate reader.

- Procedure:

- Seed cells into 96-well plates at a pre-optimized density.

- After cell adherence, treat with a concentration gradient of the test compound.

- Incubate for a determined period (e.g., 48 hours).

- Add the viability reagent and incubate further to allow viable cells to metabolize the dye.

- Measure the absorbance or fluorescence of the formed product.

- Normalize data to untreated control wells, plot percentage viability vs. log(concentration), and calculate the IC50.

Diagram 1: IC50 determination involves a series of standardized steps to ensure reliable results.

Navigating Pitfalls in IC50 Determination

Several factors can introduce variability in IC50 values, highlighting the need for careful experimental design.

- Calculation Methods: A study on P-glycoprotein inhibition found that IC50 values can vary significantly depending on the equation and software used for calculation [14]. This points to a need for standardization within a laboratory.

- Assay System Dimensionality: Computational models suggest that IC50 values derived from 2D monolayer cell cultures can differ substantially from those in 3D spheroid cultures, which better mimic in vivo tumor geometry due to factors like limited drug diffusion [15]. The choice of assay system impacts the translational relevance of the result.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Computational and Experimental Validation

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Software | AutoDock Vina, GOLD, GUSAR, MOPAC | Performs molecular docking, (Q)SAR modeling, and binding energy calculations to generate initial predictions [11] [13] [16]. |

| Protein & Enzymes | Purified Tyrosinase, Recombinant Proteins | Used in in vitro enzymatic assays (e.g., tyrosinase inhibition) to measure direct compound-target interactions [11]. |

| Cell Lines | SW-480, HT-29, Caco-2 | Provide a physiological model for cell-based viability and IC50 assays, validating activity in a cellular context [14] [12]. |

| Viability/Cell Assays | MTT, MTS, PrestoBlue | Measure metabolic activity as a proxy for cell viability and proliferation after compound treatment [12]. |

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL, DrugBank, ZINC | Provide curated data on known bioactive molecules and their properties, used for training and benchmarking predictive models [17] [16] [18]. |

The journey from a computational prediction to a validated therapeutic candidate is fraught with challenges. As demonstrated, even advanced models can show poor predictive power without experimental refinement [13]. The integration of computational efficiency with experimental rigor creates a powerful, iterative feedback loop. Computational tools excel at screening vast chemical spaces and generating hypotheses, while experimental IC50 values provide the essential ground truth, validating predictions, refining models, and ultimately building the confidence required to advance drug candidates. In the high-stakes field of drug discovery, this synergy is not just beneficial—it is indispensable.

The Tectonic Shift Towards Computational-Aided Drug Discovery

The field of drug discovery is undergoing a fundamental transformation, shifting from traditional labor-intensive methods to sophisticated computational-aided approaches. This tectonic shift is driven by artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and advanced computational modeling that are revolutionizing how researchers identify and optimize potential therapeutic compounds [19]. Traditional drug discovery remains a complex, time-intensive process that spans over a decade and incurs an average cost exceeding $2 billion, with nearly 90% of drug candidates failing due to insufficient efficacy or unforeseen safety concerns [20]. In contrast, computational-aided drug design (CADD) leverages algorithms to analyze complex biological datasets, predict compound interactions, and optimize clinical trial design, significantly accelerating the identification of potential drug candidates while reducing costs [21] [20].

The validation of computational predictions against experimental data forms the critical bridge between in silico models and real-world applications. Among various validation metrics, the half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) serves as a crucial experimental benchmark for on-target activity in lead optimization [8]. This article explores the current landscape of computational-aided drug discovery, focusing specifically on the performance comparison of various computational methods and their experimental validation through IC50 values, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for evaluating these rapidly evolving technologies.

Performance Comparison of Computational Methods

The computational drug discovery landscape encompasses diverse approaches, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and performance characteristics. The table below provides a comparative overview of major methodologies based on their prediction capabilities, requirements, and validation metrics:

| Method Category | Examples | Primary Applications | IC50 Prediction Performance | Data Requirements | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure-Based Design | Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamics Simulations [21] | Binding site identification, binding mode prediction | Varies significantly by scoring function; requires experimental validation [18] | Target 3D structure (e.g., from AlphaFold [21]) | Limited by scoring function accuracy; computationally expensive [22] |

| Ligand-Based Design | QSAR, Pharmacophore Modeling [21] | Compound activity prediction, lead optimization | Can predict relative potency but requires correlation with experimental IC50 [18] | Known active compounds and their activities | Limited to chemical space similar to known actives [18] |

| Machine Learning Scoring | Random Forest, Support Vector Regressor [23] [18] | Binding affinity prediction, DDI magnitude prediction | 78% of predictions within 2-fold of observed values for DDIs [23] | Large training datasets of binding affinities | "Black box" interpretability challenges [20] |

| Deep Learning Methods | DeepAffinity, DeepDTA [18] | Drug-target binding affinity (DTBA) prediction | Emerging approach; performance highly dataset-dependent [18] | Very large labeled datasets (e.g., ChEMBL) | High computational requirements; limited interpretability [18] |

Performance Analysis and Key Insights

Machine learning methods demonstrate particularly strong performance for quantitative predictions. In predicting pharmacokinetic drug-drug interactions (DDIs), support vector regression achieved the strongest performance, with 78% of predictions falling within twofold of the observed exposure changes [23]. This regression-based approach provides more meaningful quantitative predictions compared to binary classification models, enabling better assessment of DDI risk and potential clinical impact.

The accuracy of IC50 data presents both opportunities and challenges for method validation. A statistical analysis of public ChEMBL IC50 data revealed that even when mixing data from different laboratories and assay conditions, the standard deviation of IC50 data is only approximately 25% larger than the more consistent Ki data [8]. This moderate increase in noise suggests that carefully curated public IC50 data can reliably be used for large-scale modeling efforts, though researchers should be aware of potential variability when interpreting results.

For structure-based methods, performance heavily depends on the quality of the target protein structure. Tools like AlphaFold have revolutionized this field by providing highly accurate protein structure predictions, enabling more reliable molecular docking studies even when experimental structures are unavailable [21]. The continued improvement of these structure prediction tools, such as the enhanced protein interaction capabilities of AlphaFold 3, further expands the applicability of structure-based approaches [21].

Experimental Validation with IC50 Values

The Role of IC50 in Computational Model Validation

The biochemical half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) represents the most commonly used metric for on-target activity in lead optimization, serving as a crucial experimental benchmark for validating computational predictions [8]. In the context of computational model validation, IC50 values provide quantitative experimental measurements against which virtual screening results, binding affinity predictions, and activity forecasts can be correlated and validated. This experimental validation is essential for establishing model credibility and guiding lead optimization decisions.

The Cheng-Prusoff equation provides the fundamental relationship between IC50 values and binding constants (Ki) for competitive inhibitors:

[Ki = \frac{IC{50}}{1 + \frac{[S]}{K_m}}]

where [S] is the substrate concentration and K_m is the Michaelis-Menten constant [8]. This relationship allows researchers to convert between these related metrics, though it requires knowledge of specific assay conditions that may not always be available in public databases.

IC50 Data Variability and Statistical Considerations

A comprehensive statistical analysis of IC50 data variability revealed several critical considerations for experimental validation:

Inter-laboratory variability: When comparing independent IC50 measurements on identical protein-ligand systems, the standard deviation of public ChEMBL IC50 data is greater than that of in-house intra-laboratory data, reflecting the inherent variability introduced by different experimental conditions and protocols [8].

Data quality assessment: Analysis of ChEMBL database entries identified that only approximately 6% of protein/ligand systems with multiple measurements remained after rigorous filtering to ensure truly independent data points, highlighting the importance of careful data curation for validation studies [8].

Conversion factors: For broad datasets such as ChEMBL, a Ki-IC50 conversion factor of 2 was found to be most reasonable when combining these related metrics for model training or validation [8].

The following diagram illustrates the recommended workflow for experimental validation of computational predictions using IC50 values:

IC50 Experimental Validation Workflow

Domain-Specific Metrics for Biopharma Applications

While IC50 values provide crucial quantitative validation, researchers in drug discovery are increasingly adopting domain-specific metrics that address the unique challenges of biomedical data. These include:

Precision-at-K: Particularly valuable for virtual screening, this metric evaluates the model's ability to identify true active compounds among the top K ranked candidates, directly relevant to lead identification efficiency [24].

Rare event sensitivity: Essential for predicting low-frequency events such as adverse drug reactions or toxicological signals, this metric emphasizes detection capability over overall accuracy [24].

Pathway impact metrics: These assess how well computational predictions identify biologically relevant pathways, ensuring that results have mechanistic relevance beyond statistical correlation [24].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Successful implementation and validation of computational drug discovery approaches require specific research reagents and tools. The following table details essential components of the research toolkit:

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function in Computational Validation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL [8], BindingDB [18] | Provide experimental IC50 data for model training and validation | Annotated bioactivity data extracted from literature; essential for benchmarking |

| Protein Structure Prediction | AlphaFold [21], RaptorX [21] | Generate 3D protein structures for structure-based design | Accurate protein structure prediction without experimental determination |

| Molecular Docking Software | Various commercial and open-source platforms [18] | Predict binding modes and affinities for virtual screening | Scoring functions to rank potential ligands; binding pose prediction |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Scikit-learn [23], DeepLearning | Implement regression models for affinity prediction | Pre-built algorithms for quantitative structure-activity relationship modeling |

| Experimental Assay Systems | Enzyme activity assays, Cell-based screening | Generate experimental IC50 values for validation | Standardized protocols for concentration-response measurements |

Methodologies for Key Experiments

Experimental Protocol for IC50 Determination

The experimental validation of computational predictions typically involves determining IC50 values through standardized laboratory protocols. A robust methodology includes:

Assay design: Develop biochemical or cell-based assays that measure the functional activity of the target protein. The assay should be optimized for appropriate substrate concentrations (typically near the K_m value) and linear reaction kinetics [8].

Compound preparation: Prepare serial dilutions of the test compound across a concentration range that spans the anticipated IC50 value. Typically, 3-fold or 10-fold dilutions across 8-12 data points are used to adequately define the concentration-response curve.

Data collection and analysis: Measure the inhibitory effect at each compound concentration and fit the data to a sigmoidal concentration-response model using nonlinear regression. The IC50 value is determined as the compound concentration that produces 50% inhibition of the target activity.

Statistical Validation Protocol

To ensure robust correlation between computational predictions and experimental IC50 values, researchers should implement rigorous statistical validation:

Data curation: Apply filtering steps to remove erroneous entries, including unit conversion errors, duplicate values, and unrealistic measurements [8]. For public database mining, remove data from reviews and focus on original research.

Correlation analysis: Calculate correlation coefficients (e.g., Pearson's R²) between predicted and experimental binding affinities. For IC50 data, use pIC50 values (-log10[IC50]) to normalize the data distribution [8].

Error metrics: Determine mean unsigned error (MUE) and median unsigned error (MedUE) to assess prediction accuracy. For pairs of measurements, divide these values by √2 to account for overestimation [8].

The following workflow illustrates the integrated computational-experimental pipeline for drug discovery:

Computational-Experimental Drug Discovery Pipeline

The tectonic shift toward computational-aided drug discovery represents a fundamental transformation in pharmaceutical research, enabling more efficient and targeted therapeutic development. The performance comparison presented in this guide demonstrates that while computational methods have reached impressive capabilities for predicting drug-target interactions and binding affinities, experimental validation through IC50 determination remains essential for establishing model credibility.

The continuing evolution of AI and ML approaches, coupled with increasingly accurate protein structure prediction tools like AlphaFold, suggests that computational methods will play an even more significant role in future drug discovery efforts. However, the successful integration of these technologies will require ongoing attention to experimental validation, careful consideration of domain-specific metrics, and robust statistical analysis of the correlation between computational predictions and experimental results. As these fields continue to converge, researchers who effectively bridge computational and experimental approaches will be best positioned to advance the next generation of therapeutics.

In pharmacological research and drug discovery, the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) has long been a cornerstone parameter for quantifying compound potency. This single-point measurement, representing the concentration of a drug required to inhibit a biological process by half, provides a straightforward means to compare the effectiveness of different compounds [7]. Its utility and simplicity have cemented its role as a standard benchmark for evaluating the efficacy of antitumor agents and other therapeutics [7].

However, a growing body of evidence suggests that this snapshot metric provides an incomplete picture of drug action. The dynamic and multi-faceted nature of biological systems, encompassing protein flexibility, mutation-induced resistance, and complex pharmacokinetics, cannot be fully captured by a single time-point measurement [25] [26]. This article explores the significant limitations of relying solely on IC50 values and makes the case for integrating dynamic, computational models that offer a more comprehensive framework for predicting drug efficacy, particularly when confronting challenges like drug resistance.

The Inherent Limitations of IC50 Measurements

Technical and Methodological Variability

The experimental determination of IC50 is not without its pitfalls. Different assay methods can yield significantly variable results for the same drug-target interaction. For instance, a novel surface plasmon resonance (SPR) imaging platform demonstrated the inability of conventional Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assays to quantitatively assess the cytotoxic effect on MCF-7 breast cancer cells, highlighting a critical limitation of enzymatic assays for certain cell types [7]. This methodological dependency challenges the reliability of directly comparing IC50 values obtained through different experimental setups.

The Oversimplification of Complex Biology

IC50 is typically measured at fixed time intervals, classifying it as an end-point assay. This static nature means critical temporal events, such as delayed toxicity or cellular recovery, may be entirely missed [7]. Biological processes are fundamentally dynamic; cells undergo continuous changes in morphology, adhesion, and signaling in response to drug exposure. Apoptosis (programmed cell death) and necrosis (uncontrolled cell death) both induce significant alterations in cell attachment, which are not captured by a single-point measurement [7].

The Critical Challenge of Drug Resistance

Perhaps the most compelling argument against the sole use of IC50 emerges in the context of drug resistance, particularly in diseases like chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). Resistance to first-line CML treatment develops in approximately 25% of patients within two years, primarily due to mutations in the target Abl1 enzyme [26]. Studies contest the use of fold-IC50 values (the ratio of mutant IC50 to wild-type IC50) as a reliable guide for treatment selection in resistant cases. Computational models of CML treatment reveal that the relative decrease of product formation rate, termed "inhibitory reduction prowess," serves as a better indicator of resistance than fold-IC50 values [26]. This is because mutations conferring resistance affect not only drug binding but also fundamental enzymatic properties like catalytic rate (kcat), factors which IC50 alone does not sufficiently integrate.

Structural Biases in Dataset Evaluation

In the era of data-driven drug discovery, the reliance on IC50 as a prediction label for machine learning models introduces another layer of complexity. The maximum concentration (MC) of a drug tested in vitro heavily influences the resulting IC50 value [27]. Consequently, models predicting IC50 may learn to exploit these concentration range biases rather than genuine biological relationships, a phenomenon known as "specification gaming" or "reward hacking" [27]. This can lead to models that perform well on standard benchmarks but fail to generalize to new drugs or cell lines, undermining their real-world utility.

Methodological Comparison: Traditional vs. Dynamic Approaches

Table 1: Comparison of Key Methodologies in Drug Potency Assessment

| Method | Core Principle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (e.g., MTT, CCK-8) | Measures drug concentration that inhibits 50% of activity at a fixed time point [7]. | Simple, affordable, and widely established [7]. | End-point measurement; misses dynamic events; assay reagents can interfere with results [7]. |

| SPR Imaging | Label-free, real-time monitoring of cellular adhesion changes in response to drugs via reflective properties of gold nanostructures [7]. | Accurate, high-throughput, label-free; enables real-time monitoring of cell adhesion as a viability proxy [7]. | Requires specialized nanostructure-based sensor chips and imaging systems [7]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Computationally simulates physical movements of atoms and molecules over time using Newton's laws of motion [25] [28]. | Accounts for full flexibility of protein and ligand; can reveal cryptic binding pockets; provides atomic-level detail [25]. | Computationally expensive; limited timescales; accuracy depends on force field parameters [25]. |

| Relaxed Complex Scheme (RCS) | Combines MD simulations with molecular docking by docking compounds into multiple receptor conformations sampled from MD trajectories [25]. | Accounts for target flexibility; can identify novel binding sites; improves docking accuracy for flexible targets [25]. | Even more computationally demanding than standard MD due to need for extensive sampling [25]. |

Experimental Protocols in Practice

1. Contrast SPR Imaging for IC50 Determination

This label-free protocol involves capturing SPR images of cells on gold-coated nanowire array sensors at three critical stages: during initial cell seeding, immediately after drug administration, and 24 hours post-treatment [7]. The nanostructures produce a reflective SPR dip, and changes in cell adhesion alter the local refractive index, shifting the SPR signal. The differential SPR response, calculated from red and green channel contrast images using a formula like γ = (I_G - I_R)/(I_G + I_R), reflects cell viability. By tracking these changes over time across different drug concentrations, a dose-response curve is generated to quantitatively determine the IC50 value [7].

2. Integrated Computational/Experimental Workflow for Tyrosinase Inhibition A study on flavonoids from Alhagi graecorum exemplifies a modern integrated approach [29]. The workflow begins with in silico methods: molecular docking simulations to predict the binding affinity and orientation of compounds to the tyrosinase active site, followed by molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to explore the stability and energy landscapes of these complexes over time. Key computational parameters, such as binding free energies calculated via MM/PBSA analysis, are used to rank compounds. The most promising candidates, such as the predicted-high-affinity "compound 5," are then synthesized or isolated and validated through in vitro tyrosinase inhibition assays to determine experimental IC50 values, closing the loop between prediction and validation [29].

Visualizing the Dynamic Drug Discovery Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the integrated cycle of modern, dynamic approaches to drug discovery that move beyond single-point data.

Dynamic and Integrated Drug Discovery Workflow. This diagram outlines a modern pipeline that uses dynamic computational methods to overcome the limitations of static approaches. Molecular dynamics simulations sample protein flexibility, enabling more effective virtual screening. Promising candidates are evaluated using dynamic resistance models before experimental validation, creating a feedback loop for continuous model improvement.

Advancing Beyond IC50: Superior Metrics and Models

Area Under the Dose-Response Curve (AUDRC)

To address the concentration-range bias inherent in IC50, the Area Under the Dose-Response Curve (AUDRC) is increasingly advocated as a more robust alternative [27]. Unlike IC50, which relies on a single point on the curve, AUDRC integrates the entire dose-response relationship, providing a more comprehensive summary of drug effect across all tested concentrations. This makes it less susceptible to the influence of arbitrary maximum concentration choices and a more reliable label for machine learning models in drug response prediction.

The "Inhibitory Reduction Prowess" Metric

In the specific context of overcoming enzyme-level drug resistance, a novel parameter called "inhibitory reduction prowess" has been proposed [26]. It is defined as the relative decrease in the product formation rate of the target enzyme (e.g., mutant Abl1) in the presence of an inhibitor. Computational models for CML treatment demonstrate that this dynamic metric, which incorporates information on catalysis, inhibition, and pharmacokinetics, is a better indicator of a drug's efficacy against resistant mutants than the traditional fold-IC50 value [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Advanced Drug Potency Studies

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Gold-Coated Nanowire Array Sensors | Serves as the substrate in reflective SPR imaging. Its periodic nanostructure (e.g., 400 nm periodicity) generates a surface plasmon resonance used to detect changes in cell adhesion as a proxy for viability [7]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD) | Software suites used to run MD simulations. They calculate the time-dependent behavior of a molecular system (protein-ligand complexes) based on Newtonian physics and specified force fields, revealing dynamics and cryptic pockets [25] [28]. |

| Docking Software (e.g., AutoDock Vina) | Programs that perform molecular docking, predicting the preferred orientation and binding affinity of a small molecule (ligand) to a target macromolecule (receptor) [25]. Often used in conjunction with MD in the Relaxed Complex Scheme [25]. |

| Ultra-Large Virtual Compound Libraries (e.g., REAL Database) | On-demand, synthetically accessible virtual libraries containing billions of drug-like compounds. They dramatically expand the accessible chemical space for virtual screening campaigns, increasing the chance of identifying novel hits [25]. |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | A database providing over 214 million predicted protein structures generated by the machine learning tool AlphaFold. It enables structure-based drug design for targets without experimentally determined 3D structures [25]. |

The evidence is clear: while the IC50 value offers a convenient and standardized metric for initial compound ranking, its nature as a single-point, static measurement renders it insufficient for navigating the complexities of modern drug discovery, especially in predicting and overcoming drug resistance. The future lies in embracing a multi-faceted and dynamic approach. This paradigm integrates computational techniques like molecular dynamics and the relaxed complex method—which account for the intrinsic flexibility of biological targets—with more informative experimental metrics like AUDRC and innovative, label-free real-time monitoring technologies. Furthermore, the development of novel, mechanism-informed parameters such as "inhibitory reduction prowess" promises to guide treatment selection more effectively in the face of resistance. By moving beyond the IC50-centric view and adopting these integrated strategies, researchers and drug developers can significantly enhance the predictive power of their workflows and accelerate the delivery of more effective and resilient therapeutics.

Methodologies in Action: Techniques for Predicting and Measuring Compound Activity

Structure-based virtual screening has become a cornerstone of early drug discovery, with growing interest in the computational screening of multi-billion compound libraries to identify novel hit molecules [30]. This approach leverages computational power to prioritize compounds for synthesis and testing, dramatically reducing the time and cost associated with traditional experimental high-throughput screening [31]. The success of virtual screening campaigns depends critically on the accuracy of computational docking methods to predict binding poses and affinities, and on the ability to implement these methods at an unprecedented scale [30]. As ultra-large "tangible" libraries containing billions of readily synthesizable compounds become more accessible, robust computational frameworks capable of efficiently screening these vast chemical spaces are increasingly valuable to drug discovery researchers [32]. This guide provides an objective comparison of current platforms and methodologies for large-scale virtual screening, with a specific focus on the experimental validation of computational predictions through binding affinity measurements.

Platform Comparison: Capabilities and Performance

Various computational platforms have been developed to address the formidable challenge of screening billion-compound libraries, each employing distinct strategies to balance speed, accuracy, and computational cost.

Table 1: Comparison of Large-Scale Virtual Screening Platforms

| Platform Name | Docking Engine | Scoring Function | Scale Demonstrated | Hit Rate Validation | Computational Infrastructure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RosettaVS (OpenVS) | Rosetta GALigandDock | Physics-based (RosettaGenFF-VS) with entropy | Multi-billion compounds | 14% (KLHDC2), 44% (NaV1.7) | HPC (3000 CPUs + GPU), 7 days screening [30] |

| Schrödinger Virtual Screening Web Service | Glide | Physics-based + Machine Learning | >1 billion compounds | Not specified | Cloud-based, 1 week turnaround [33] |

| warpDOCK | Qvina2, AutoDock Vina, and others | Vina-based or other compatible functions | 100 million+ compounds | Not specified | Oracle Cloud Infrastructure, cost-estimated [34] |

| DockThor-VS | DockThor | MMFF94S force field + DockTScore | Not specified for ultra-large scale | Not specified | Brazilian SDumont supercomputer [35] |

Performance Metrics and Experimental Validation

The ultimate measure of a virtual screening platform's success lies in its ability to identify compounds with experimentally confirmed activity. The RosettaVS platform demonstrated a 14% hit rate against the ubiquitin ligase target KLHDC2 and a remarkable 44% hit rate against the human voltage-gated sodium channel NaV1.7, with all discovered hits exhibiting single-digit micromolar binding affinity [30]. Furthermore, the platform's predictive accuracy was validated by a high-resolution X-ray crystallographic structure that confirmed the docking pose for a KLHDC2-ligand complex [30].

Benchmarking studies provide standardized assessments of docking performance. On the CASF-2016 benchmark, the RosettaGenFF-VS scoring function achieved a top 1% enrichment factor (EF) of 16.72, significantly outperforming other methods [30]. In studies targeting Plasmodium falciparum dihydrofolate reductase (PfDHFR), re-scoring with machine learning-based scoring functions substantially improved performance, with CNN-Score combined with FRED docking achieving an EF1% of 31 against the resistant quadruple-mutant variant [36].

Essential Protocols for Large-Scale Virtual Screening

The RosettaVS Two-Stage Screening Protocol

The RosettaVS method employs a structured workflow to efficiently screen ultra-large libraries while maintaining accuracy.

Figure 1: The two-stage RosettaVS screening workflow with experimental validation. This protocol enables efficient screening of billion-compound libraries while maintaining high accuracy through successive filtering stages.

Protocol Details:

Virtual Screening Express (VSX) Mode: Initial rapid screening performed with rigid receptor docking to quickly eliminate poor binders from the billion-compound library. This stage prioritizes speed over precision [30].

Active Learning Compound Selection: A target-specific neural network is trained during docking computations to intelligently select promising compounds for more expensive calculations, avoiding exhaustive docking of the entire library [30].

Virtual Screening High-Precision (VSH) Mode: A more computationally intensive docking stage that incorporates full receptor flexibility, including side-chain and limited backbone movements, to accurately model induced fit upon ligand binding [30].

Experimental Validation: Top-ranked compounds proceed to experimental testing, typically beginning with binding affinity measurements (IC50/Kd determination) followed by structural validation through X-ray crystallography when possible [30].

Machine Learning-Enhanced Screening Protocol

An alternative approach integrates machine learning scoring functions with traditional docking tools to improve screening performance, particularly for challenging targets like drug-resistant enzymes.

Protocol Details:

Initial Docking with Generic Tools: Compounds are initially docked using standard docking programs such as AutoDock Vina, FRED, or PLANTS [36].

ML-Based Re-scoring: Docking poses are subsequently re-scored using machine learning scoring functions such as CNN-Score or RF-Score-VS v2, which have demonstrated significant improvements in enrichment factors over classical scoring functions [36].

Enrichment Analysis: Performance is quantified using enrichment factors (EF1%), which measure the ability to identify true actives in the top fraction of ranked compounds, and pROC chemotype analysis to evaluate the diversity of retrieved actives [36].

Successful virtual screening campaigns require careful selection of computational tools, compound libraries, and experimental validation reagents.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Virtual Screening

| Resource Category | Specific Resource | Function and Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docking Software | Rosetta GALigandDock [30] | Physics-based docking with receptor flexibility | Models side-chain and limited backbone flexibility |

| AutoDock Vina [31] [36] | Widely-used docking program | Fast, open-source, good balance of speed and accuracy | |

| Qvina2 [34] | Docking engine for large-scale screens | Optimized for speed in high-throughput docking | |

| Scoring Functions | RosettaGenFF-VS [30] | Physics-based scoring with entropy estimation | Combines enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS) terms |

| CNN-Score, RF-Score-VS v2 [36] | Machine learning scoring functions | Improve enrichment when re-scoring docking outputs | |

| Compound Libraries | "Tangible" make-on-demand libraries [32] | Ultra-large screening collections | Billions of synthesizable compounds, increasingly diverse |

| ChemDiv Database [37] | Commercial compound library | 1.5+ million compounds for initial screening | |

| Experimental Validation Reagents | IC50 Binding Assays [30] [37] | Quantitative binding affinity measurement | Validates computational predictions with experimental data |

| X-ray Crystallography [30] | Structural validation of binding poses | Confirms accuracy of predicted ligand binding modes | |

| Target Protein Structures | Structural basis for docking | Wild-type and mutant forms (e.g., PfDHFR variants) [36] |

Key Considerations for Experimental Validation

Correlation Between Computational and Experimental Results

The relationship between computational docking scores and experimental binding affinities forms the critical bridge between in silico predictions and experimental reality. Studies have demonstrated that docking scores typically improve log-linearly with library size, meaning that screening larger libraries increases the likelihood of identifying better-fitting ligands [32]. However, this also increases the potential for false positives that rank artifactually well due to limitations in scoring functions [32].

Experimental validation remains essential, as even the best docking scores represent only approximations of binding affinity. The most convincing validation comes from cases where computational predictions are confirmed through multiple experimental methods, such as binding affinity measurements (IC50) supplemented by high-resolution structural biology approaches like X-ray crystallography [30].

Addressing the Challenge of Novel Chemical Space

Modern ultra-large libraries have significantly expanded the accessible chemical space for drug discovery, but this expansion comes with both opportunities and challenges. Unlike traditional screening collections that show strong bias toward "bio-like" molecules (metabolites, natural products, and drugs), newer billion-compound libraries contain substantially more diverse chemistry, with a 19,000-fold decrease in compounds highly similar to known bio-like molecules [32]. Interestingly, successful hits from large-scale docking campaigns consistently show low similarity to bio-like molecules, with Tanimoto coefficients typically below 0.6 and peaking around 0.3-0.35 [32]. This suggests that effective virtual screening platforms must be capable of identifying novel chemotypes beyond traditional drug-like space.

Virtual screening of billion-compound libraries represents a powerful approach for lead discovery in drug development, with platforms like RosettaVS, Schrödinger's Virtual Screening Web Service, and warpDOCK demonstrating capabilities to efficiently navigate this vast chemical space. The integration of advanced scoring functions, active learning methodologies, and machine learning-based re-scoring has significantly improved the enrichment of true hits from docking screens. Critical to the success of any virtual screening campaign is the rigorous experimental validation of computational predictions through binding affinity measurements and structural biology approaches. As tangible compound libraries continue to expand and computational methods evolve, the ability to effectively leverage these resources will become increasingly important for drug discovery researchers seeking to identify novel chemical starting points for therapeutic development.

In the field of drug discovery and precision oncology, the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) serves as a crucial quantitative measure of a compound's potency, representing the concentration required to inhibit a biological process by half. Accurate prediction of IC50 values is fundamental for assessing drug efficacy, prioritizing candidate compounds, and tailoring personalized treatment strategies. The advent of large-scale pharmacogenomic databases, such as the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) and the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer (GDSC), has provided researchers with extensive datasets containing molecular characterizations of cancer cell lines alongside drug sensitivity measurements, enabling the development of machine learning models for IC50 prediction.

Machine learning approaches have dramatically transformed the landscape of drug sensitivity prediction, offering powerful tools to decipher complex relationships between molecular features of cancer cells and their response to therapeutic compounds. These models range from traditional ensemble methods like Random Forests to sophisticated deep neural architectures, each with distinct strengths, limitations, and performance characteristics. The integration of diverse biological data types—including gene expression profiles, mutation data, and chemical compound representations—has further enhanced the predictive capability of these models, advancing their applications in virtual screening, drug repurposing, and personalized treatment recommendation.

This comprehensive comparison guide examines the current state of machine learning approaches for IC50 prediction, providing an objective evaluation of algorithmic performance across multiple experimental settings and datasets. By synthesizing empirical evidence from benchmarking studies and innovative methodological developments, this review offers researchers and drug development professionals a structured framework for selecting appropriate modeling strategies based on specific research objectives, data availability, and performance requirements.

Comparative Performance of Machine Learning Algorithms

Benchmarking Studies and Performance Metrics

Table 1: Performance Comparison of ML Algorithms for IC50 Prediction on GDSC Data

| Algorithm | Best-Performing DR Method | Average R² | Average RMSE | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elastic Net | PCA, mRMR | 0.43 | 0.64 | Lowest runtime, high interpretability, robust to overfitting | Linear assumptions may miss complex interactions |

| Random Forest | MACCS fingerprints | 0.45 | 0.62 | Handles non-linear relationships, robust to outliers | Longer training time, less interpretable than linear models |

| Boosting Trees | mRMR | 0.41 | 0.67 | High predictive power with proper tuning | Prone to overfitting without careful parameter tuning |

| Neural Networks | PCA | 0.38 | 0.71 | Captures complex interactions, flexible architectures | Computationally intensive, requires large data volumes |

Large-scale benchmarking studies provide critical insights into the relative performance of machine learning algorithms for IC50 prediction. A comprehensive evaluation of four machine learning algorithms—random forests, neural networks, boosting trees, and elastic net—across 179 anti-cancer compounds from the GDSC database revealed important performance patterns [38]. The study employed nine different dimension reduction techniques to manage the high dimensionality of gene expression data (17,419 genes) and trained models to predict logarithmized IC50 values.

The results demonstrated that elastic net models achieved the best overall performance across most compounds while maintaining the lowest computational runtime [38]. This superior performance of regularized linear models suggests that for many drug response prediction tasks, the relationship between gene expression and IC50 may be sufficiently captured by linear relationships when combined with appropriate feature selection. Random forests consistently displayed robust performance across diverse drug classes, particularly when using MACCS fingerprint representations for drug compounds [39]. The algorithm's ability to handle non-linear relationships and maintain performance with minimal hyperparameter tuning contributes to its widespread adoption in drug sensitivity prediction.

Neural networks generally showed more variable performance, excelling for specific drug classes but demonstrating poorer average performance across the entire compound library [38]. This performance pattern highlights the importance of dataset size and architecture optimization for deep learning approaches, as they typically require larger training samples to reach their full potential compared to traditional machine learning methods.

Domain Adaptation and Cross-Database Performance

Table 2: Cross-Database Model Performance (CCLE to GDSC Transfer)

| Model Architecture | RMSE | R² | Key Features | Transfer Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DADSP (Proposed) | 0.64 | 0.43 | Domain adversarial discriminator | Domain adaptation |

| DADSP-A (No pre-training) | 0.71 | 0.31 | Standard deep feedforward network | No transfer learning |

| DeepDSC-1 (Target only) | 0.69 | 0.35 | Stacked autoencoder | No source domain data |

| DeepDSC-2 (With pre-training) | 0.66 | 0.39 | Joint pre-training on both domains | Parameter transfer |

| SLA (Selective Learning) | 0.65 | 0.41 | Intermediate domain selection | Selective transfer |

The challenge of cross-database prediction represents a significant hurdle in computational drug discovery, as models trained on one dataset often experience performance degradation when applied to external datasets due to technical variations and batch effects. The DADSP (Domain Adaptation for Drug Sensitivity Prediction) framework addresses this challenge through a deep transfer learning approach that integrates gene expression profiles from both CCLE and GDSC databases [40]. This method employs stacked autoencoders for feature extraction and domain adversarial training to align feature distributions across source and target domains, significantly improving cross-database generalization.

Experimental results demonstrate that models incorporating domain adaptation strategies consistently outperform those trained exclusively on target domain data [40]. The DADSP model achieved an RMSE of 0.64 and R² of 0.43 in cross-database prediction tasks, representing approximately 10% improvement in RMSE compared to models without domain adaptation components [40]. This performance advantage highlights the value of transfer learning methodologies in addressing distributional shifts between pharmaceutical databases, a common challenge in computational drug discovery.

Beyond traditional IC50 prediction, recent research has pioneered models capable of predicting complete dose-response curves rather than single summary metrics [41]. The Functional Random Forest (FRF) approach represents a significant methodological advancement by incorporating region-wise response points or distributions in regression tree node costs, enabling prediction of entire dose-response profiles [41]. This functionality provides more comprehensive drug sensitivity characterization beyond IC50 values alone, capturing critical information about drug efficacy across concentration gradients.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

The foundational step in IC50 prediction involves meticulous data preprocessing and feature engineering to transform raw biological and chemical data into machine-learnable representations. For genomic features, the standard protocol involves normalization of gene expression data to mitigate technical variations between experiments. In the DrugS model framework, researchers implement log transformation and scaling of expression values for 20,000 protein-coding genes to minimize outlier influence and ensure cross-dataset comparability [42]. For chemical compound representation, extended-connectivity fingerprints (ECFPs) and MACCS keys serve as prevalent structural descriptors, capturing molecular substructures and key functional groups relevant to biological activity [39].

Dimensionality reduction represents a critical preprocessing step given the high-dimensional nature of genomic data (typically >17,000 genes) relative to limited cell line samples (typically hundreds to thousands). Benchmarking studies have systematically evaluated various dimension reduction techniques, including principal component analysis (PCA) and minimum-redundancy-maximum-relevance (mRMR) feature selection [38]. Results indicate that feature selection methods incorporating drug response information during feature selection generally outperform methods based solely on expression variance, underscoring the importance of response-guided feature engineering.

The experimental protocol for model development typically involves strict separation of training and test sets at the cell line level, with 80% of cell lines allocated for training and 20% held out for testing [38]. This splitting strategy ensures that model performance reflects generalization to unseen cell lines rather than memorization of training instances. For cross-database validation, additional steps include dataset harmonization to align gene identifiers and expression measurement units between source and target domains [40].

Model Training and Hyperparameter Optimization

The model training phase employs systematic hyperparameter optimization to maximize predictive performance while mitigating overfitting. For tree-based methods including Random Forests and boosting trees, critical hyperparameters include the number of trees in the ensemble, maximum tree depth, and the number of features considered for each split [38]. The benchmarking protocol typically involves 5-fold cross-validation on the training set to evaluate hyperparameter combinations, with the mean squared error (MSE) serving as the primary optimization metric [38].

For neural network architectures, hyperparameter space encompasses the number of hidden layers, activation functions, dropout rates, and learning rate schedules. The DrugS model employs a specialized architecture incorporating autoencoder-based dimensionality reduction to compress 20,000 genes into 30 latent features, which are then concatenated with 2,048 chemical features derived from compound SMILES strings [42]. This approach effectively addresses the "small n, large p" problem prevalent in drug sensitivity prediction, where the number of features vastly exceeds the number of samples.

The Functional Random Forest implementation introduces modified node cost calculations that incorporate the complete dose-response curve structure rather than individual response values [41]. This approach represents functional data using B-spline basis expansions and modifies the node splitting criterion to consider response distributions across concentration gradients, enabling more biologically-informed model training.

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for IC50 Prediction Models. This diagram illustrates the standard methodology for developing machine learning models to predict drug sensitivity, encompassing data sourcing, preprocessing, model training with cross-validation, and output generation.

Signaling Pathways and Biological Mechanisms

Genomic Determinants of Drug Sensitivity

Machine learning models for IC50 prediction have revealed important insights into the biological mechanisms and signaling pathways that govern drug sensitivity in cancer cells. Gene expression profiles consistently emerge as the most predictive features for drug response across multiple benchmarking studies [38] [42]. Clustering analyses of cancer cell lines based on gene expression patterns reveal distinct molecular subtypes that correlate with differential drug sensitivity, highlighting the fundamental relationship between transcriptional states and therapeutic response [42].

Pathway enrichment analyses of genes selected as important features in predictive models identify several key signaling pathways frequently associated with drug sensitivity mechanisms. These include the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, TNF signaling pathway, and NF-κB signaling pathway, all of which play critical roles in cell survival, proliferation, and death decisions [42]. Models trained specifically on pathway activity scores rather than individual gene expressions have demonstrated competitive performance while offering enhanced biological interpretability, directly linking predicted sensitivities to dysregulated biological processes.

For targeted therapies, specific genomic alterations serve as strong predictors of sensitivity or resistance. For instance, BRAF V600E mutations predict sensitivity to RAF inhibitors, while HER2 amplification status determines response to HER2-targeted therapies [42]. The integration of mutation data with gene expression profiles further enhances prediction accuracy for molecularly targeted agents, enabling more precise identification of patient subgroups likely to benefit from specific treatments.

Chemical and Structural Determinants of Compound Potency

Beyond cellular features, the chemical properties of compounds significantly influence their biological activity and potency. Molecular fingerprints that encode chemical structure information, particularly MACCS keys and Morgan fingerprints, have proven highly effective in representing compounds for sensitivity prediction [39]. These representations capture structural features relevant to target binding, membrane permeability, and metabolic stability, all of which contribute to compound efficacy.

Studies comparing alternative drug representations, including physico-chemical properties and explicit target information, found that structural fingerprints generally outperformed other representation schemes [39]. This advantage likely stems from their ability to encode complex structural patterns that correlate with biological activity, enabling models to identify structural motifs associated with potency against specific cancer types.

Figure 2: Key Signaling Pathways in Drug Sensitivity Mechanisms. This diagram illustrates the relationship between dysregulated cancer pathways, drug classes, and their mechanisms of action, highlighting biological processes that influence IC50 values.

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for IC50 Prediction Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Resource | Key Application | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacogenomic Databases | GDSC | Drug sensitivity data for 700+ cell lines | https://www.cancerrxgene.org |

| CCLE | Molecular characterization of 1000+ cell lines | https://sites.broadinstitute.org/ccle | |

| DrugComb | Harmonized drug combination screening data | https://drugcomb.org | |

| Chemical Databases | ChEMBL | Bioactivity data for drug-like molecules | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl |

| PubChem | Chemical structures and properties | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov | |

| Software Libraries | scikit-learn | Traditional ML algorithms (RF, EN) | https://scikit-learn.org |

| TensorFlow/Keras | Deep neural network implementation | https://www.tensorflow.org | |

| caret | Unified framework for model training | https://topepo.github.io/caret |

The development and validation of IC50 prediction models rely on specialized computational tools and data resources that enable reproducible research. Pharmacogenomic databases serve as foundational resources, providing comprehensive drug sensitivity measurements alongside molecular characterization data. The GDSC database contains sensitivity data for 198 drugs across approximately 700 cancer cell lines, while the CCLE provides complementary data for 947 cell lines and 24 compounds [41]. The recently established DrugComb portal further expands these resources by aggregating harmonized drug combination screening data from 37 sources, enabling development of models for combination therapy response [39].

For chemical data representation, resources including ChEMBL and PubChem provide standardized compound structures and bioactivity data essential for training structure-activity relationship models. The integration of Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) representations with molecular fingerprinting algorithms enables efficient encoding of chemical structures for machine learning applications [42]. Specialized packages like RDKit offer comprehensive cheminformatics functionality for fingerprint generation, molecular descriptor calculation, and chemical similarity assessment.

Machine learning libraries provide the algorithmic implementations necessary for model development. The scikit-learn library in Python offers efficient implementations of traditional algorithms including random forests and elastic net, while TensorFlow and Keras support development of deep neural architectures [38]. For R users, the caret package provides a unified interface for multiple machine learning algorithms with streamlined preprocessing and hyperparameter tuning capabilities [38]. These tools collectively establish a robust software ecosystem for developing, validating, and deploying IC50 prediction models.

The comprehensive comparison of machine learning approaches for IC50 prediction reveals a complex performance landscape where no single algorithm dominates across all scenarios. Elastic net regression demonstrates exceptional performance for many drug prediction tasks despite its relative simplicity, offering advantages in computational efficiency, interpretability, and robustness to overfitting [38]. Random forest models maintain strong performance across diverse experimental conditions, particularly when combined with appropriate chemical structure representations [39]. More complex deep neural architectures show promise for specific applications but require careful architecture design and substantial training data to achieve their full potential [42].

The evolution of IC50 prediction is moving beyond single summary metrics toward complete dose-response curve prediction [41]. Functional Random Forest approaches represent an important step in this direction, enabling prediction of response across concentration gradients rather than isolated IC50 values. This paradigm shift provides more comprehensive characterization of compound potency and efficacy, supporting more informed therapeutic decisions. Similarly, the development of models capable of predicting combination therapy response addresses a critical clinical need, as drug combinations increasingly represent standard care across multiple cancer types [39].

Future advancements in IC50 prediction will likely focus on improved generalization across datasets through enhanced domain adaptation techniques [40], integration of multi-omics data beyond transcriptomics, and development of interpretable models that provide biological insights alongside predictions. As these models continue to mature, their integration into drug discovery pipelines and clinical decision support systems holds significant promise for accelerating therapeutic development and personalizing cancer treatment.

In modern computational drug discovery, the representation of a chemical molecule is a fundamental determinant of the success of predictive models. The process of feature engineering—selecting and optimizing how molecules are translated into numerical vectors—lies at the heart of building reliable Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models. These models aim to predict biological activity, such as the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50), from chemical structure. Within the broader thesis of validating computational predictions with experimental IC50 values, understanding the strengths and limitations of different molecular representations is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals. This guide provides an objective comparison of the two primary families of molecular representations—molecular descriptors and structural fingerprints—by examining their performance across various experimental protocols and biological targets.

Molecular representations can be broadly classified into two categories: molecular descriptors and structural fingerprints.

- Molecular Descriptors are often calculated from the molecular structure and represent global physicochemical properties. Examples include molecular weight (MolWt), topological polar surface area (TPSA), and the octanol-water partition coefficient (logP) [43] [44]. They are typically continuous numerical values and are classified by the dimensionality of the information they encode (e.g., 1D, 2D, or 3D) [44].

- Structural Fingerprints are typically binary or count-based vectors that encode the presence or absence of specific substructures or topological patterns within the molecule [45]. Key types include:

- Circular Fingerprints (e.g., ECFP, FCFP, Morgan): These generate molecular features by iteratively considering the neighborhood around each atom up to a certain radius, creating a representation that captures local chemical environment [45] [46].

- Path-based Fingerprints (e.g., Atom Pairs, Topological Torsions): These analyze paths through the molecular graph, recording features based on atom pairs or sequences of connected bonds [45] [47].

- Substructure Key-based Fingerprints (e.g., MACCS Keys): These use a predefined dictionary of structural fragments, where each bit in the vector corresponds to the presence or absence of one specific fragment [45] [46].

The choice between descriptors and fingerprints is not merely technical; it influences the model's interpretability, its ability to generalize, and ultimately, how well its predictions can be validated with experimental IC50 assays.

Performance Comparison Across Benchmarks

Predictive Performance in Various Biological Contexts

Extensive benchmarking studies have evaluated these representations across diverse prediction tasks. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent research.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Molecular Representations on Different Prediction Tasks

| Prediction Task | Best Performing Representation | Algorithm | Key Performance Metric(s) | Source / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odor Perception | Morgan Fingerprints (ST) | XGBoost | AUROC: 0.828; AUPRC: 0.237 [43] | Curated dataset of 8,681 compounds [43] |

| ADME-Tox Targets(e.g., Ames, hERG, BBB) | Traditional 2D Descriptors | XGBoost | Superior to fingerprints for most targets [44] | Literature-based datasets (1,000-6,500 molecules) [44] |

| Drug Combination Sensitivity & Synergy | Data-Driven & Rule-Based Fingerprints (variable) | Multiple ML/DL models | Performance context-dependent [48] | 14 drug screening studies; 4153 molecules [48] |