From In Silico to In Vitro: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Pharmacophore Hits with Experimental Testing

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating pharmacophore models and their virtual screening hits.

From In Silico to In Vitro: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Pharmacophore Hits with Experimental Testing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating pharmacophore models and their virtual screening hits. It covers the foundational principles of pharmacophore modeling, outlines rigorous computational validation methodologies including decoy set and cost function analyses, discusses strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls, and details the transition to experimental testing through binding and functional assays. The guide synthesizes current best practices to bridge the gap between computational predictions and experimental confirmation, ensuring the identification of robust, biologically active lead compounds.

The Essential Blueprint: Understanding Pharmacophore Models and the Imperative for Validation

In the realm of computer-aided drug discovery (CADD), pharmacophore modeling stands as a pivotal technique for identifying and optimizing bioactive compounds. The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines a pharmacophore as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [1]. This abstract representation focuses not on specific chemical structures, but on the essential functional features required for biological activity, including hydrogen bond acceptors (HBAs), hydrogen bond donors (HBDs), hydrophobic areas (H), positively and negatively ionizable groups (PI/NI), and aromatic rings (AR) [1] [2].

Pharmacophore modeling has become an indispensable tool in modern drug discovery, finding applications in virtual screening, lead optimization, scaffold hopping, and de novo drug design [1]. By capturing the key molecular interactions necessary for target binding, pharmacophore models serve as efficient queries to rapidly screen large chemical databases and identify potential hit compounds with desired biological activities. The fundamental strength of pharmacophore approaches lies in their ability to identify structurally diverse compounds that share common bioactive features, thereby facilitating the discovery of novel chemical scaffolds with improved properties [2].

Two principal methodologies have emerged for pharmacophore model development: ligand-based and structure-based approaches. The selection between these strategies depends primarily on the availability of experimental data, either in the form of known active ligands or three-dimensional structures of the target protein [1] [2]. Both approaches aim to define the spatial and electronic requirements for molecular recognition, but they differ significantly in their underlying principles, implementation workflows, and application domains, as will be explored in this comprehensive comparison.

Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Conceptual Foundation and Methodology

Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling relies exclusively on information derived from a set of known active compounds that interact with a common biological target. This approach is particularly valuable when the three-dimensional structure of the target protein is unknown or difficult to obtain [3]. The fundamental premise is that compounds sharing similar biological activities against the same target must contain common pharmacophoric features in a specific three-dimensional arrangement that enables molecular recognition [1] [2].

The workflow for ligand-based pharmacophore modeling typically involves multiple stages [2]. First, a collection of active compounds with experimentally validated activities is selected. These compounds are then used to generate multiple conformations to account for molecular flexibility. The resulting conformers are subsequently aligned to identify common chemical features and their spatial relationships. From this alignment, the essential features responsible for biological activity are extracted to form the pharmacophore hypothesis. This model must then be validated using a testing dataset containing both active compounds and decoys (inactive compounds) to evaluate its ability to distinguish true actives [2]. Finally, the validated model can be applied to screen compound libraries for new potential hits.

Key Techniques and Experimental Protocols

Several computational techniques are integral to ligand-based pharmacophore modeling. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) analysis employs mathematical models to establish correlations between chemical structures and biological activity based on molecular descriptors such as electronic properties, hydrophobicity, and steric parameters [3]. Pharmacophore modeling itself involves identifying and mapping the common steric and electronic features that are necessary for molecular recognition [3]. Virtual screening then uses these models as queries to rapidly evaluate large compound libraries in silico and prioritize molecules for experimental testing [3] [1].

The experimental protocol for ligand-based pharmacophore modeling follows a systematic process [2]. Researchers begin with selecting experimentally validated active compounds, ensuring adequate structural diversity while maintaining consistent activity against the target. These compounds then undergo 3D conformation generation, typically using algorithms that explore rotational bonds and ring conformations to create a comprehensive set of low-energy conformers. Structural alignment follows, where conformers are superimposed based on shared pharmacophoric features or molecular shape similarity. From the aligned structures, key chemical features involved in target binding are identified and their spatial relationships quantified. The resulting pharmacophore model is then validated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and enrichment factors (EF) to assess its ability to discriminate between active and inactive compounds [4]. Finally, the validated model serves as a search query for screening natural product or chemical databases to identify novel potential active compounds [2].

Table 1: Key Techniques in Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Technique | Primary Function | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| QSAR Analysis | Correlates molecular descriptors with biological activity | Enables predictive modeling of compound activity |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Identifies essential steric and electronic features | Captures key interaction patterns independent of scaffold |

| Virtual Screening | Filters compound libraries using pharmacophore queries | Rapidly reduces chemical space for experimental testing |

| Shape-Based Alignment | Superimposes molecules based on volume overlap | Accounts for steric complementarity with target |

Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

Conceptual Foundation and Methodology

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling derives its hypotheses directly from the three-dimensional structure of the target protein, typically obtained through experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) [3] [1]. This approach analyzes the binding site characteristics of the target protein to identify interaction points that a ligand would need to complement for effective binding [1]. When available, structures of protein-ligand complexes provide particularly valuable information by directly revealing the specific interactions between the protein and a bound ligand in its bioactive conformation [1].

The structure-based workflow initiates with careful protein preparation, which involves evaluating residue protonation states, adding hydrogen atoms (often missing in X-ray structures), and assessing overall structure quality [1]. The next critical step involves identifying and characterizing the ligand-binding site, which can be accomplished using various computational tools such as GRID or LUDI that analyze protein surfaces to detect potential binding pockets based on geometric, energetic, or evolutionary properties [1]. From the binding site analysis, pharmacophoric features are generated that represent the complementary chemical functionalities a ligand would require to interact favorably with the protein. Finally, the most essential features are selected for inclusion in the final model, often by removing redundant or energetically less significant features to create a refined pharmacophore hypothesis [1].

Key Techniques and Experimental Protocols

Structure-based pharmacophore modeling leverages several structural biology and computational techniques. X-ray crystallography provides high-resolution protein structures by analyzing diffraction patterns from protein crystals, though it requires protein crystallization [3]. NMR spectroscopy studies protein structures in solution, making it particularly suitable for proteins difficult to crystallize and for studying flexible regions [3]. Cryo-electron microscopy enables structure determination of large protein complexes at near-atomic resolution without crystallization [3]. Molecular docking predicts how small molecules bind to protein targets, providing insights into binding modes and interactions [1].

The experimental protocol for structure-based pharmacophore modeling involves systematic steps [1] [4]. It begins with acquiring and preparing the target protein structure from sources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or through computational methods like homology modeling when experimental structures are unavailable. The binding site is then identified through analysis of known ligand positions, computational prediction tools, or manual inspection based on biological data. From the binding site, interaction points are mapped to identify regions conducive to hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, ionic contacts, and other molecular recognition events. These interaction points are translated into pharmacophore features such as hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, and charged groups. Exclusion volumes are often added to represent steric restrictions of the binding pocket. The resulting model is validated using known active compounds and decoys to assess its discriminative power before application in virtual screening [4].

Table 2: Key Techniques in Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Technique | Primary Function | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | Determines atomic-resolution protein structures | Provides detailed interaction information from co-crystals |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Resolves protein structures in solution | Captures dynamic flexibility and conformational changes |

| Cryo-EM | Visualizes large macromolecular complexes | Avoids crystallization requirements |

| Molecular Docking | Predicts ligand binding poses and interactions | Generates protein-ligand complexes for model building |

Comparative Analysis: Ligand-Based vs. Structure-Based Approaches

Direct Comparison of Key Parameters

The selection between ligand-based and structure-based pharmacophore modeling approaches depends on multiple factors, including data availability, target characteristics, and project goals. The table below provides a systematic comparison of both methodologies across critical parameters.

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of Ligand-Based vs. Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling

| Parameter | Ligand-Based Approach | Structure-Based Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirements | Set of known active compounds | 3D structure of target protein |

| Key Principles | Molecular similarity and common pharmacophoric features | Structural complementarity to binding site |

| When to Use | Target structure unknown; multiple active ligands available | Protein structure available; novel scaffold discovery |

| Information Used | Chemical features of active ligands | Binding site properties and protein-ligand interactions |

| Typical Features | HBA, HBD, hydrophobic, aromatic, ionizable groups | HBA, HBD, hydrophobic, aromatic, ionizable groups, exclusion volumes |

| Advantages | No need for target structure; can incorporate multiple chemotypes | Direct structural insights; can design novel scaffolds |

| Limitations | Dependent on quality and diversity of known actives | Requires high-quality protein structure |

| Validation Metrics | ROC curves, enrichment factors, AUC values [4] | ROC curves, enrichment factors, docking validation |

| Software Tools | LigandScout, MOE, Pharmer, Align-it [2] | LigandScout, MOE, Pharmit, PharmMapper [2] |

Performance and Application Considerations

In practical applications, both approaches have demonstrated significant value in drug discovery campaigns. Structure-based methods excel when high-quality protein structures are available, particularly when accompanied by experimental data on protein-ligand complexes. For example, in a study targeting XIAP protein, a structure-based pharmacophore model generated from a protein-ligand complex (PDB: 5OQW) successfully identified natural compounds with potential anticancer activity, demonstrating an excellent area under the ROC curve (AUC) value of 0.98 and an early enrichment factor (EF1%) of 10.0 [4].

Ligand-based approaches demonstrate particular strength when working with targets lacking experimental structures but with abundant ligand activity data. These methods can effectively capture common features across diverse chemical scaffolds, enabling scaffold hopping and identification of structurally novel active compounds. The performance heavily depends on the quality, diversity, and structural coverage of the known active compounds used for model generation [2].

Recent advances have integrated both approaches with artificial intelligence techniques. For instance, pharmacophore-guided deep learning models like PGMG (Pharmacophore-Guided deep learning approach for bioactive Molecule Generation) can generate novel bioactive molecules by using pharmacophore hypotheses as input, bridging different types of activity data and enabling flexible generation without further fine-tuning [5]. Similarly, novel frameworks have been developed that balance pharmacophore similarity to reference compounds with structural diversity, creating molecules that maintain biological relevance while introducing substantial structural novelty for improved patentability [6].

Experimental Validation of Pharmacophore Models

Validation Methodologies

Regardless of the modeling approach, rigorous validation is essential to establish the predictive power and reliability of pharmacophore models before their application in virtual screening. The validation process typically employs statistical measures and experimental verification to ensure model quality [4] [2].

A standard validation protocol involves testing the model against a dataset containing both known active compounds and decoy molecules (presumed inactives) [4]. The performance is evaluated using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves which plot the true positive rate against the false positive rate at various threshold settings. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) provides a single measure of overall model performance, with values closer to 1.0 indicating better discriminatory power [4]. Additionally, enrichment factors (EF) quantify the model's ability to selectively identify active compounds early in the screening process, with EF1% representing enrichment in the top 1% of the screened database [4].

For structure-based models, validation may also include assessment of the model's ability to reproduce known binding modes from crystallographic data and to predict activities of compounds with known experimental values. Ligand-based models are often validated through leave-one-out cross-validation or by dividing the compound set into training and test groups to evaluate predictive accuracy [2].

Integration with Experimental Testing

The ultimate validation of any pharmacophore model comes from experimental confirmation of newly identified hits. Promising compounds selected through virtual screening should undergo in vitro biological testing to verify predicted activities [4]. For successful hits, subsequent lead optimization cycles combine computational design with synthetic chemistry and pharmacological profiling to develop compounds with improved potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties [1] [4].

This iterative process of computational prediction and experimental validation forms the cornerstone of modern structure-based drug design, ensuring that pharmacophore models are continually refined and improved based on experimental feedback. The integration of computational approaches with experimental testing provides a powerful strategy for accelerating drug discovery while reducing costs and resource requirements [1] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

The implementation of pharmacophore modeling approaches relies on various software tools and computational resources. The table below summarizes key solutions available to researchers in the field.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| LigandScout | Software | Ligand- and structure-based pharmacophore modeling | Commercial |

| Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) | Software | Comprehensive drug discovery suite with pharmacophore capabilities | Commercial |

| Pharmer | Software | Ligand-based pharmacophore modeling and screening | Open-source |

| Align-it | Software | Align molecules based on pharmacophores | Open-source |

| Pharmit | Web Server | Structure-based pharmacophore screening | Free access |

| PharmMapper | Web Server | Target identification using pharmacophore mapping | Free access |

| ZINC Database | Database | Curated collection of commercially available compounds | Free access |

| RCSB PDB | Database | Experimentally determined protein structures | Free access |

| ChEMBL | Database | Bioactive molecules with drug-like properties | Free access |

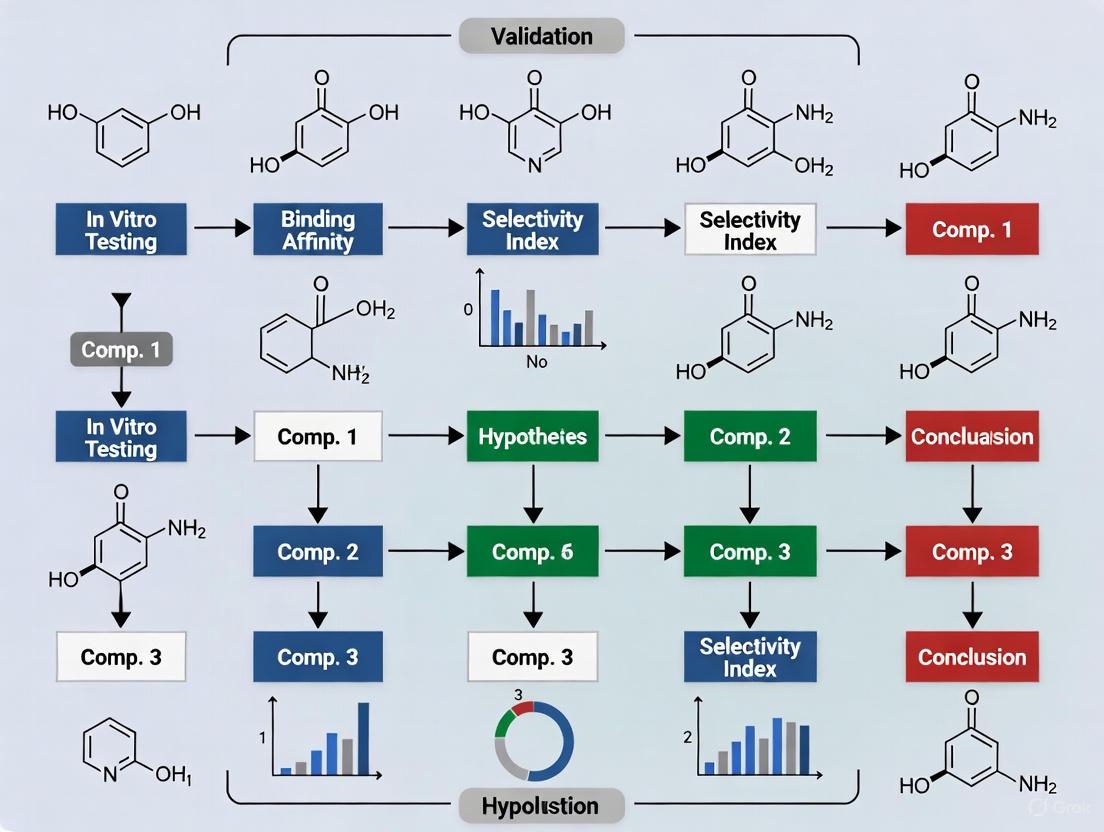

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the comparative workflows for ligand-based and structure-based pharmacophore modeling, highlighting key decision points and methodological differences.

Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow Decision Tree

Both ligand-based and structure-based pharmacophore modeling offer powerful, complementary approaches for modern drug discovery. The selection between these strategies should be guided by available data, target characteristics, and project objectives. Ligand-based methods provide robust solutions when structural information is limited but ligand activity data is abundant, while structure-based approaches offer direct insights into molecular recognition requirements when protein structures are available.

The integration of both methodologies, along with emerging artificial intelligence techniques, represents the future of pharmacophore-based drug discovery. By combining the strengths of each approach and maintaining a rigorous cycle of computational prediction and experimental validation, researchers can effectively navigate complex chemical spaces and accelerate the identification of novel therapeutic agents. As computational power increases and structural databases expand, pharmacophore modeling will continue to evolve as an indispensable tool in the drug discovery arsenal, particularly for challenging targets and personalized medicine applications.

In modern drug discovery, the ability to computationally identify potential drug candidates is paramount. Pharmacophore modeling serves as a cornerstone of Computer-Aided Drug Discovery (CADD), providing an abstract representation of the molecular functional features necessary for a compound to bind to a biological target and trigger a biological response [1]. However, the true value of any computational model lies not in its creation but in its rigorous validation. For researchers and drug development professionals, a pharmacophore model without robust validation is a hypothesis without proof; it may guide experiments but carries a high risk of costly failure. Validation transforms a theoretical construct into a reliable tool with demonstrated predictive power and robustness, ensuring that virtual hits identified through screening have a high probability of exhibiting real-world biological activity. This process is non-negotiable for derisking the drug discovery pipeline and is governed by structured principles that separate useful models from mere computational artifacts.

The Foundation: Understanding Pharmacophore Models

A pharmacophore is defined by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supra-molecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or to block) its biological response" [1]. It is not a physical molecule but a three-dimensional abstraction of the essential chemical interactions a ligand must form with its target.

- Core Features: The most important pharmacophoric features are represented as geometric entities like points, spheres, and vectors. These include Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA), Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD), Hydrophobic areas (H), Positively/Negatively Ionizable groups (PI/NI), and Aromatic rings (AR) [1].

- Modeling Approaches: The generation of a pharmacophore model typically follows one of two primary strategies, chosen based on data availability and the research question.

- Structure-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: This approach relies on the three-dimensional structure of the macromolecular target, obtained from sources like the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or through computational methods like homology modelling or AlphaFold2. The model is built by analyzing the ligand-binding site to derive a map of interactions and the spatial arrangement of complementary features. When a protein-ligand complex structure is available, the features can be generated more accurately from the ligand's bioactive conformation, and exclusion volumes (XVOL) can be added to represent the shape of the binding pocket [1].

- Ligand-Based Pharmacophore Modeling: When the 3D structure of the target is unavailable, this approach uses the physicochemical properties and structural features of a set of known active ligands. Methods like the HypoGen algorithm can develop a 3D-QSAR pharmacophore model from a training set of active compounds, identifying common features responsible for biological activity across diverse chemical scaffolds [7].

The following diagram illustrates the foundational concept of how a pharmacophore model, derived from either a structure or a set of ligands, serves as a query to identify new potential drug candidates.

The Critical Pillars of Model Validation

The validation of pharmacophore and associated QSAR models is systematically guided by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) principles. These principles provide a framework for establishing the scientific credibility of a model, with Principle 4 focusing specifically on performance metrics [8].

- Goodness-of-Fit: This measures how well the model reproduces the response variable (e.g., biological activity) of the training set data on which its parameters were optimized. Common parameters include the coefficient of determination (R²) and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE). It is a measure of internal consistency. However, it is crucial to recognize that goodness-of-fit parameters can misleadingly overestimate model performance on small samples, making them insufficient as a sole validation measure [8].

- Robustness (Internal Validation): This assesses the model's stability and reliability when subjected to small perturbations in the training data. It is typically evaluated through resampling methods like Leave-One-Out (LOO) cross-validation or Leave-Many-Out (LMO) cross-validation. In these methods, parts of the data are repeatedly omitted, the model is refitted, and its ability to predict the omitted data is quantified (e.g., using Q²). Robustness checks ensure the model is not over-fitted to the specific noise in its training set [8].

- Predictivity (External Validation): This is the ultimate test of a model's practical utility. It evaluates the model's ability to accurately predict the activity of compounds that were not included in the training set. An external test set of compounds is held back from the initial model-building process and used only for this final assessment. Metrics like Q²F2 or Concordance Correlation Coefficient (CCC) are used. Predictivity demonstrates the model's generalizability to new chemical matter [8].

The interplay of these validation pillars can be visualized as a sequential workflow that ensures a model is reliable before deployment.

Comparative Analysis: Validated vs. Non-Validated Models

The theoretical need for validation is clear, but its practical impact is best demonstrated through comparative data. The table below summarizes key performance indicators that distinguish a validated model from a non-validated one.

Table 1: Performance Comparison Between Validated and Non-Validated Pharmacophore Models

| Performance Indicator | Validated Model | Non-Validated or Weakly Validated Model |

|---|---|---|

| Goodness-of-Fit (R²) | High but interpreted in context of other metrics [8] | May be deceptively high, especially on small datasets [8] |

| Robustness (Q² LOO/LMO) | High Q² value, stable with data perturbation [8] | Low Q² value, significant performance drop on cross-validation |

| External Predictivity (Q² F2/CCC) | High predictive accuracy for novel compounds [8] | Poor generalization, fails to predict external test set activity |

| Hit Rate in Virtual Screening | Higher probability of identifying true active compounds [7] [9] | High rate of false positives, wasting experimental resources |

| Scaffold Hopping Potential | Can successfully identify novel chemotypes with desired activity [1] | Tied to the chemical scaffolds of the training set |

| Resistance to Chance Correlation | Verified through Y-scrambling; model fails when activity is randomized [8] | Susceptible to chance correlations, giving false confidence |

The consequences of skipping validation are not merely statistical; they directly impact research efficiency and outcomes. For instance, in a study seeking Topoisomerase I inhibitors, researchers developed a ligand-based pharmacophore model (Hypo1) from 29 camptothecin derivatives. They then validated it with a test set of 33 molecules before employing it for virtual screening. This rigorous process led to the identification of several potential "hit molecules" with confirmed stable interactions in molecular dynamics studies [7]. Similarly, a structure-based pharmacophore model for Apoptosis Signal-Regulating Kinase 1 (ASK1) inhibitors was used to screen 4160 natural compounds. The top candidates not only exhibited high docking scores but also underwent ADMET prediction and 100ns molecular dynamics simulations—advanced forms of validation that confirmed the stability of the ligand-protein complex [9]. These examples underscore that validation is the critical step that translates a computational idea into a tangible research lead.

Essential Experimental Protocols for Validation

For scientists implementing these principles, following detailed and standardized protocols is key. Below are outlined core methodologies for the key validation experiments.

Protocol for Internal Validation (Cross-Validation)

This protocol assesses the robustness of a pharmacophore or QSAR model.

- Data Preparation: Curate a training set of compounds with known biological activities. Ensure chemical diversity and a wide range of activity.

- Model Generation: Develop the pharmacophore or QSAR model using the entire training set.

- Data Omission: Remove one compound (LOO) or a subset of compounds (LMO, e.g., 20%) from the training set.

- Model Refitting: Recompute the model parameters using the reduced training set.

- Prediction: Use the refitted model to predict the activity of the omitted compound(s).

- Cycle Repetition: Repeat steps 3-5 until every compound in the training set has been omitted and predicted once.

- Calculation of Q²: Calculate the cross-validated correlation coefficient (Q²) using the predicted activities versus the actual activities. A high Q² indicates a robust model.

- Formula: ( Q^2 = 1 - \frac{\sum (y{actual} - y{predicted})^2}{\sum (y{actual} - \bar{y}{training})^2} ) where ( y{actual} ) is the actual activity, ( y{predicted} ) is the predicted activity, and ( \bar{y}_{training} ) is the mean activity of the training set.

Protocol for External Validation

This is the gold standard for evaluating a model's predictive power.

- Data Splitting: Before any model development, randomly divide the full dataset into a training set (typically 70-80%) and an external test set (20-30%). The test set must never be used in model building or training.

- Model Construction: Build the pharmacophore or QSAR model exclusively using the training set.

- Blind Prediction: Use the final model to predict the activities of the compounds in the external test set.

- Performance Calculation: Calculate predictive metrics by comparing the predictions to the known experimental activities.

- Key Metrics:

- Q²F2 / ( R^2_{ext} ): Similar to Q² but calculated for the external test set.

- Root Mean Square Error of Prediction (RMSEP): The standard deviation of the prediction residuals.

- Interpretation: A model with high Q²F2 and low RMSEP is considered predictive and reliable for practical use.

- Key Metrics:

Protocol for Y-Scrambling

This test ensures the model is not the result of chance correlation.

- Randomization: Randomly shuffle the biological activity values (Y-response) among the compounds in the training set, breaking the true structure-activity relationship.

- New Model Generation: Attempt to build a new model using the scrambled activity data.

- Iteration: Repeat steps 1 and 2 many times (e.g., 100-1000 iterations).

- Comparison: Compare the performance (R² and Q²) of the original model with the distribution of performance from the scrambled models.

- Result Interpretation: If the original model's performance is significantly better than any of the scrambled models, it is unlikely to be a product of chance correlation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Computational Solutions

The execution of pharmacophore modeling and validation relies on a suite of specialized software tools and data resources. The following table details essential "research reagent solutions" for the computational drug developer.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents & Computational Solutions for Pharmacophore Modeling and Validation

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Validation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery Studio (DS) | Software Suite | Provides integrated environment for ligand- and structure-based pharmacophore generation, HypoGen algorithm, and built-in cross-validation tools [7]. | Comprehensive toolset for model building, virtual screening, and molecular dynamics analysis. |

| RCSB Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Data Resource | Source of experimental 3D protein structures for structure-based pharmacophore modeling and target analysis [1]. | Critical for obtaining high-quality input data for model construction. |

| ZINC Database | Data Resource | A publicly available library of commercially available compounds for virtual screening of validated pharmacophore models [7]. | Allows transition from a theoretical model to a list of purchasable candidate molecules. |

| HypoGen Algorithm | Software Algorithm | Used for ligand-based 3D-QSAR pharmacophore generation from a set of active training compounds [7]. | Enables model creation when a protein structure is unavailable. |

| GOLD / AutoDock | Docking Software | Used for molecular docking to validate pharmacophore hits by studying binding poses and interaction energies with the target [7] [9]. | Provides a complementary method to confirm the binding mode predicted by the pharmacophore. |

| Schrödinger Suite | Software Suite | Offers a platform for structure-based pharmacophore creation, molecular docking, MM/GBSA calculations, and molecular dynamics simulations [9]. | Facilitates advanced validation and binding free energy calculations. |

In the demanding field of drug discovery, where resources are finite and the stakes are high, rigorous validation of computational tools is not an optional refinement—it is a fundamental requirement. Pharmacophore models, whether structure-based or ligand-based, must be subjected to the triad of goodness-of-fit, robustness, and predictivity assessments as outlined by OECD principles. As demonstrated, validated models are the ones that successfully transition from abstract hypotheses to practical tools, capable of identifying novel scaffolds like Topoisomerase I and ASK1 inhibitors with a high degree of confidence. They provide a reliable filter for navigating vast chemical space, ensuring that the compounds selected for costly and time-consuming experimental testing have the highest possible chance of success. For research teams aiming to accelerate their discovery pipeline and maximize return on investment, a non-negotiable commitment to thorough model validation is the most strategic decision they can make.

In the field of computer-aided drug discovery, pharmacophore models serve as essential tools for identifying and optimizing potential therapeutic compounds. These abstract representations of molecular interactions require rigorous validation to ensure their predictive power and practical utility in virtual screening. The validation process relies on key statistical performance indicators, primarily Predictive Correlation (Q²) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), to quantify how well a pharmacophore model can identify true active compounds and accurately predict their binding affinities. Within the broader context of validating pharmacophore hits with experimental testing research, these metrics provide the quantitative foundation for assessing model reliability before committing resources to costly laboratory experiments and synthesis. Q² offers insights into the model's correlative predictive ability, while RMSE provides a measure of its precision in estimating binding energies or biological activities. Furthermore, establishing the statistical significance of differences between model performances ensures that observed improvements are genuine and not merely due to random variations in the data. Together, these KPIs form a critical framework for evaluating pharmacophore models throughout the drug discovery pipeline, from initial virtual screening to lead optimization and experimental verification.

Defining the Core Performance Metrics

Predictive Correlation (Q²)

Predictive Correlation, commonly denoted as Q², serves as a crucial metric for evaluating the external predictivity of quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models and pharmacophore-based approaches. Unlike the traditional R² statistic, which measures how well a model fits its training data, Q² specifically assesses how well the model predicts the properties of an independent test set that was not used during model development. This distinction is particularly important in pharmacophore modeling, where the ultimate goal is to correctly predict the activity of novel compounds outside the training chemical space. Q² is mathematically defined as follows [10]:

where $y{observed}$ represents the actual experimental values, $y{predicted}$ denotes the model predictions for the test set, and $\bar{y}_{training}$ is the mean of the training set observations. In practical terms, Q² values closer to 1.0 indicate excellent predictive capability, while values near or below zero suggest the model has no predictive advantage over simply using the mean activity of the training compounds. For pharmacophore models, a Q² value above 0.5 is generally considered acceptable, while values above 0.7 indicate good to excellent predictive power in estimating binding affinities or biological activities of new chemical entities.

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE)

Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) quantifies the average magnitude of prediction errors, providing a measure of how close a model's predictions are to the actual observed values. In pharmacophore validation, RMSE is particularly valuable for assessing the precision of activity predictions, as it penalizes larger errors more heavily than smaller ones due to the squaring of individual errors. This characteristic makes RMSE highly relevant in drug discovery contexts, where large prediction errors could lead to misleading conclusions about compound potency. RMSE is calculated using the following formula [11] [12]:

where N represents the number of observations in the test set. The resulting value is expressed in the same units as the original response variable (typically pIC50 or pKi values in pharmacophore applications), making it intuitively interpretable. For instance, an RMSE of 0.5 log units in pKi prediction implies that, on average, the model's predictions differ from the experimental values by approximately half a log unit, which corresponds to roughly a 3-fold error in binding affinity. Lower RMSE values indicate better model precision, with values below 0.5 log units generally considered excellent for pharmacophore models, while values between 0.5-1.0 log units may be acceptable depending on the specific application and biological variability.

Table 1: Interpretation Guidelines for Q² and RMSE in Pharmacophore Validation

| Metric | Poor | Acceptable | Good | Excellent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q² | < 0.3 | 0.3 - 0.5 | 0.5 - 0.7 | > 0.7 |

| RMSE (pKi/pIC50) | > 1.2 | 0.8 - 1.2 | 0.5 - 0.8 | < 0.5 |

Statistical Significance Testing for Model Comparison

The Need for Statistical Significance in Model Comparison

When comparing multiple pharmacophore models or virtual screening methods, researchers often observe differences in performance metrics such as RMSE values. However, determining whether these differences reflect genuine improvements in model performance or merely result from random variation requires formal statistical testing. This distinction is particularly crucial in pharmacophore-based drug discovery, where selecting an inferior model could lead to missed therapeutic opportunities or wasted experimental resources. Statistical significance testing provides an objective framework for making these decisions, ensuring that observed performance differences are reliable and reproducible. The importance of such testing increases when dealing with small test sets, where random fluctuations can have substantial effects on performance metrics, or when comparing models with seemingly small differences in RMSE that could nonetheless have significant practical implications for compound prioritization in experimental testing campaigns.

Methods for Testing Significance of Differences Between RMSE Values

Several statistical approaches can determine whether the difference between two RMSE values is statistically significant. The appropriate method depends on the experimental design, particularly whether the predictions being compared come from the same test set compounds (paired design) or different test sets (unpaired design).

For the common scenario where two models are applied to the same test set compounds, a paired t-test approach is recommended [13]. This method involves calculating the differences in squared errors for each compound and then testing whether the mean of these differences is statistically significantly different from zero. The implementation involves the following steps:

- For each test set compound i, compute the squared error for both Model A and Model B: $SE{Ai} = (y{observedi} - y{predicted{Ai}})^2$ and $SE{Bi} = (y{observedi} - y{predicted{Bi}})^2$

- Calculate the difference in squared errors for each compound: $di = SE{Ai} - SE{B_i}$

- Compute the mean ($\bar{d}$) and standard deviation ($s_d$) of these differences

- Calculate the t-statistic: $t = \frac{\bar{d}}{s_d/\sqrt{n}}$, where n is the number of test set compounds

- Compare the t-statistic to the critical t-value from the t-distribution with n-1 degrees of freedom or compute the corresponding p-value

For time-series data or when errors may be correlated, the Diebold-Mariano test represents a more appropriate alternative [14]. This test specifically designed for comparing prediction accuracy accounts for potential correlations between forecast errors and can be applied to both short and long time series data.

When comparing models evaluated on different test sets, an unpaired approach becomes necessary. In this case, an F-test for the ratio of variances of the prediction errors can be employed, though this approach has lower statistical power and requires careful interpretation.

Table 2: Statistical Tests for Comparing Model Performance Based on RMSE

| Test Scenario | Recommended Test | Key Assumptions | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Same test set compounds (paired) | Paired t-test on squared errors | Normally distributed differences in squared errors | Simple to implement; widely available in statistical software |

| Time-series data | Diebold-Mariano test | Stationary prediction errors | Specifically designed for correlated forecast errors |

| Different test sets (unpaired) | F-test on error variances | Normally distributed errors in both test sets | Lower statistical power; requires careful interpretation |

Experimental Protocols for KPI Evaluation

Standard Workflow for Pharmacophore Model Validation

The validation of pharmacophore models using Q², RMSE, and statistical significance testing follows a systematic workflow designed to ensure unbiased performance assessment. This protocol incorporates best practices from QSAR modeling and computational drug discovery, emphasizing proper dataset partitioning, rigorous statistical evaluation, and empirical validation. The following diagram illustrates this standard workflow:

Step-by-Step Protocol for Performance Evaluation

Step 1: Data Collection and Curation Collect a comprehensive dataset of compounds with experimentally determined biological activities (e.g., IC50, Ki values) against the target of interest. The dataset should include sufficient structural diversity to ensure model generalizability while spanning an appropriate range of activity values. Standardize molecular structures, generate representative 3D conformations, and carefully curate activity data to ensure consistency and reliability. For pharmacophore modeling, typically 150-500 compounds are recommended, with a minimum of 20-30 compounds required for meaningful statistical validation.

Step 2: Dataset Partitioning Divide the curated dataset into training and test sets using appropriate methods. The training set (typically 70-80% of the data) is used for pharmacophore model generation, while the test set (the remaining 20-30%) is reserved exclusively for validation. Partitioning should maintain similar activity distributions and chemical space coverage in both sets. For small datasets, apply y-randomization or use cluster-based splitting to ensure representative distribution. For larger datasets, random sampling is generally acceptable. Never use test set compounds in any phase of model development to maintain validation integrity.

Step 3: Pharmacophore Model Generation Develop pharmacophore models using the training set compounds and their associated activity data. Common approaches include:

- Ligand-based methods: Identify common chemical features among active compounds

- Structure-based methods: Derive features from protein-ligand complex structures

- Fragment-based methods: Aggregate feature information from multiple fragment poses

Step 4: Internal Validation (Training Set) Assess model performance on the training set using internal validation techniques such as leave-one-out (LOO) or leave-many-out cross-validation. Calculate cross-validated Q² (also denoted as q²) to estimate internal predictive ability. While useful for model selection during development, internal validation metrics often provide overly optimistic estimates of external predictive performance.

Step 5: External Validation (Test Set Predictions) Apply the finalized pharmacophore model to predict activities of the test set compounds that were excluded from model development. This represents the most rigorous approach for estimating real-world predictive performance. Record both the predicted activities and the actual experimental values for all test set compounds.

Step 6: Performance Metric Calculation Compute Q² and RMSE values using the test set predictions and actual experimental values [10] [12]:

- Calculate Q² using the formula provided in Section 2.1

- Calculate RMSE using the formula provided in Section 2.2

- Additionally, compute mean absolute error (MAE) and determine if any systematic bias exists in the predictions

Step 7: Statistical Significance Testing If comparing multiple pharmacophore models, perform appropriate statistical tests to determine if performance differences are statistically significant:

- For paired comparisons (same test set), implement the paired t-test on squared errors as described in Section 3.2

- Report p-values and confidence intervals for performance differences

- Apply multiple testing corrections if comparing more than two models

Step 8: Results Interpretation and Model Selection Interpret the calculated metrics in the context of the specific drug discovery application. Select the most appropriate pharmacophore model based on a combination of statistical performance, chemical intuitiveness, and practical considerations for the intended virtual screening application.

Case Study: Fragment-Based Pharmacophore Screening for SARS-CoV-2 NSP13

Experimental Implementation and Results

A recent study demonstrating the application of Q², RMSE, and statistical significance testing in pharmacophore validation involved the development of FragmentScout, a novel fragment-based pharmacophore virtual screening workflow for identifying SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 helicase inhibitors [15]. The researchers developed joint pharmacophore queries by aggregating feature information from experimental fragment poses obtained through XChem high-throughput crystallographic screening. These queries were then used for virtual screening alongside traditional docking approaches with Glide software.

The performance of the FragmentScout pharmacophore method was systematically compared against docking-based virtual screening using multiple metrics, including enrichment factors, hit rates, and importantly, the accuracy of activity predictions for identified hits. The experimental validation included both biophysical ThermoFluor assays and cellular antiviral assays, providing a comprehensive assessment of model performance. The FragmentScout workflow demonstrated superior performance in identifying novel micromolar potent SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 helicase inhibitors, with several compounds showing broad-spectrum single-digit micromolar activity in cellular antiviral assays.

Performance Comparison and Statistical Analysis

The study implemented rigorous statistical comparisons to establish the significance of performance differences between pharmacophore-based and docking-based approaches. While the complete quantitative results are proprietary, the methodology included:

- Calculation of RMSE for activity predictions of identified hits versus experimental measurements

- Statistical comparison of enrichment factors and hit rates between methods

- Assessment of the structural diversity and novelty of identified hits

- Experimental validation of binding modes through co-crystallographic analysis

The superior performance of the FragmentScout pharmacophore approach, validated through statistical significance testing, highlights the value of advanced pharmacophore methods in contemporary drug discovery, particularly for challenging targets like SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 helicase.

Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacophore Validation

Table 3: Essential Research Tools and Resources for Pharmacophore Validation Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Software | Primary Function | Application in Pharmacophore Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | LigandScout, Catalyst, Phase | Pharmacophore model generation and screening | Create and optimize pharmacophore hypotheses; perform virtual screening |

| Docking Software | Glide, GOLD, AutoDock | Molecular docking and pose prediction | Comparative method for benchmarking pharmacophore performance |

| Cheminformatics Platforms | RDKit, OpenBabel, KNIME | Molecular data curation and manipulation | Prepare compound datasets; calculate molecular descriptors; manage workflow |

| Statistical Analysis Tools | R, Python (scipy, statsmodels), SPSS | Statistical computation and significance testing | Calculate Q², RMSE; perform statistical tests for model comparison |

| Visualization Software | PyMOL, Chimera, Spotfire | Structural and data visualization | Analyze pharmacophore-feature alignment; create publication-quality figures |

| Experimental Validation Assays | ThermoFluor, SPR, Cellular Antiviral Assays | Biophysical and biological compound profiling | Validate computational predictions with experimental data |

The rigorous validation of pharmacophore models using Predictive Correlation (Q²), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and statistical significance testing represents a critical component of modern computational drug discovery. These key performance indicators provide complementary information about model performance: Q² assesses the model's ability to correctly rank compounds by activity, RMSE quantifies the precision of activity predictions, and statistical significance testing determines whether performance differences between models are meaningful. When implemented within a proper validation framework that includes appropriate dataset partitioning, external testing, and experimental verification, these metrics enable researchers to select the most reliable pharmacophore models for virtual screening campaigns. This systematic approach to model validation ultimately enhances the efficiency of drug discovery by prioritizing the most promising computational methods and compound candidates for experimental testing, thereby increasing the likelihood of identifying genuine therapeutic candidates while conserving valuable resources.

In modern drug discovery, the journey from a computational pharmacophore model to a therapeutically viable lead compound is a critical yet complex pathway. A pharmacophore is defined as "the ensemble of steric and electronic features that is necessary to ensure the optimal supramolecular interactions with a specific biological target structure and to trigger (or block) its biological response" [16]. While computational methods can rapidly generate numerous potential hits, the true value of these candidates remains uncertain without rigorous experimental validation. This guide objectively compares the performance of various validation methodologies—both computational and experimental—that bridge the gap between virtual screening and confirmed biological activity, providing researchers with a structured framework for assessing pharmacophore-derived hits.

Computational Validation and Enrichment Assessment

Before committing to costly experimental work, initial computational validation ensures that pharmacophore models possess genuine predictive power and are not the result of chance correlations.

Statistical Validation Methods

Decoy Set Validation tests a model's ability to distinguish known active compounds from inactive molecules (decoys). A successful model will retrieve a high percentage of active compounds early in the screening process. Key metrics include the Enrichment Factor (EF) and the Goodness of Hit (GH) score, with values closer to 1.0 indicating excellent model performance [17] [18]. For example, a validated pharmacophore model targeting XIAP protein demonstrated an exceptional EF1% of 10.0 and an Area Under the Curve (AUC) value of 0.98, confirming its strong discriminatory power [18].

Fischer Randomization provides a statistical confidence measure by randomizing the activity data of training set compounds and regenerating pharmacophore hypotheses. If the original hypothesis cost is significantly lower than those from randomized sets, the model is unlikely to have occurred by chance. A 95% confidence level is typically used, requiring 19 random spreadsheets to be generated [17].

Structure-Based Validation through Molecular Docking

Following pharmacophore screening, molecular docking provides a complementary validation by predicting binding poses and affinities of hit compounds within the target's binding site. Docking can be performed hierarchically using high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS), standard precision (SP), and extra precision (XP) modes to progressively refine and validate potential hits [19]. The protocol involves preparing the protein structure, defining the binding site, generating compound conformations, and executing docking simulations. For instance, in the discovery of PKMYT1 inhibitors, molecular docking confirmed stable interactions with key residues like CYS-190 and PHE-240, while MM-GBSA calculations quantified binding free energies [19].

Table 1: Key Metrics for Computational Validation of Pharmacophore Models

| Validation Method | Key Metrics | Interpretation | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decoy Set Validation | Enrichment Factor (EF), Goodness of Hit (GH) | EF > 10-20 at 1% indicates strong model [17] [18] | EF1% = 10.0, AUC = 0.98 for XIAP model [18] |

| Fischer Randomization | Statistical significance, Cost difference | Cost difference > 40-60 bits indicates 75-90% true correlation [17] | 95% confidence level with 19 randomizations [17] |

| Molecular Docking | Glide Score, Binding affinity (kcal/mol), MM-GBSA | Lower scores indicate stronger binding | Interactions with CYS-190, PHE-240 in PKMYT1 [19] |

| Pharmacophore QSAR | RMSE, Correlation coefficient (r) | Lower RMSE, higher r indicate predictive power | Average RMSE of 0.62 across 250+ datasets [20] |

Figure 1: Computational Validation Workflow for Pharmacophore Models. This diagram illustrates the sequential validation steps, with pass/fail decision points that either progress toward a validated model or trigger model refinement.

Experimental Verification of Pharmacophore Hits

Once computational validation builds confidence in pharmacophore hits, experimental verification is essential to confirm genuine biological activity and therapeutic potential.

Orthogonal Binding Assays

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) provides label-free, real-time monitoring of molecular interactions by detecting changes in refractive index at a sensor surface when compounds bind to immobilized targets. SPR can quantify binding kinetics (kon and koff rates) and affinities (KD values), serving as a robust secondary validation [21].

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) measures the heat changes associated with binding events, providing direct measurement of binding affinity (KD), stoichiometry (n), and thermodynamic parameters (ΔH, ΔS). ITC is particularly valuable for confirming interactions suggested by docking studies, as it requires no labeling or immobilization [21].

Thermal Shift Assay (TSA), also known as differential scanning fluorimetry, monitors protein thermal stability changes upon ligand binding. Typically, binding stabilizes the protein, increasing its melting temperature (ΔTm). TSA is a rapid, low-consumption method suitable for early-stage validation of multiple hits [21].

Functional Activity Assays

Cell Viability Assays determine a compound's ability to inhibit cancer cell proliferation. For example, in validating the PKMYT1 inhibitor HIT101481851, researchers conducted dose-response experiments on pancreatic cancer cell lines, demonstrating concentration-dependent growth inhibition with lower toxicity toward normal pancreatic epithelial cells [19]. The MTT or MTS assays are commonly used, measuring mitochondrial activity as a proxy for cell viability.

Enzyme Inhibition Assays directly measure a compound's effect on target enzyme activity. These assays use specific substrates to quantify inhibition potency (IC50 values), providing functional validation beyond mere binding. For instance, in XIAP inhibitor discovery, researchers evaluated caspase activation as evidence of functional target engagement [18].

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Pharmacophore Hit Validation

| Validation Method | Key Parameters | Information Gained | Throughput | Sample Consumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | KD, kon, koff rates | Binding affinity & kinetics | Medium | Low |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | KD, ΔH, ΔS, n | Binding affinity & thermodynamics | Low | High |

| Thermal Shift Assay (TSA) | ΔTm, protein thermal stability | Ligand-induced stabilization | High | Very Low |

| Cell Viability Assay | IC50, % inhibition, selectivity index | Functional activity in cells | Medium | Medium |

| Enzyme Inhibition Assay | IC50, Ki, mechanism of inhibition | Direct target modulation | Medium-High | Low |

Case Study: Integrated Validation of a PKMYT1 Inhibitor

A recent study exemplifies the complete validation workflow for the PKMYT1 inhibitor HIT101481851, identified through structure-based pharmacophore modeling [19].

Computational Phase: Researchers developed pharmacophore models from four PKMYT1 co-crystal structures (PDB IDs: 8ZTX, 8ZU2, 8ZUD, 8ZUL) and performed virtual screening of 1.64 million compounds. Molecular docking prioritized HIT101481851 based on favorable binding characteristics. Molecular dynamics simulations confirmed stable interactions over 1 microsecond, with consistent contacts to key residues including CYS-190 and PHE-240 [19].

Experimental Verification: The compound progressed to in vitro testing against pancreatic cancer cell lines. Results demonstrated dose-dependent inhibition of cancer cell viability with significantly lower toxicity toward normal pancreatic epithelial cells. ADMET predictions further supported its drug-like properties with good gastrointestinal absorption and low off-target risk [19].

This case demonstrates how sequential computational and experimental validation de-risks the progression of pharmacophore hits toward lead compounds.

Figure 2: Integrated Validation Pathway for PKMYT1 Inhibitor. This case study illustrates the sequential computational and experimental validation steps that confirmed HIT101481851 as a promising PKMYT1 inhibitor for pancreatic cancer.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful validation requires specific reagents and tools tailored to each stage of the workflow.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Pharmacophore Hit Validation

| Reagent/Solution | Application | Function | Example Vendors/Platforms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Protein (>95% purity) | SPR, ITC, TSA, enzymatic assays | High-quality protein for binding and functional studies | R&D Systems, Sino Biological |

| Cell Lines (cancer & normal) | Cell viability assays | Assess compound efficacy and selectivity | ATCC, DSMZ |

| SPR Sensor Chips | Surface Plasmon Resonance | Immobilization surface for target protein | Cytiva, Bruker |

| ITC Reference Solution | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry | Matches sample heat capacity for baseline stability | MicroCal, TA Instruments |

| Fluorescent Dyes (SYPRO Orange) | Thermal Shift Assay | Reports protein unfolding at elevated temperatures | Thermo Fisher, Sigma-Aldrich |

| Cell Viability Kits (MTT/MTS) | Cellular proliferation assays | Measure metabolic activity as viability proxy | Abcam, Promega |

| Enzyme Substrates | Enzyme inhibition assays | Quantify target engagement and inhibition | Cayman Chemical, Enzo |

| ZINC/ChEMBL Databases | Virtual screening | Source compounds for pharmacophore screening | Publicly accessible |

The validation of pharmacophore hits progresses through a carefully orchestrated sequence from computational confidence to experimental verification. Initial computational validation through decoy sets, statistical testing, and molecular docking prioritizes the most promising candidates. Subsequent experimental verification using orthogonal binding assays (SPR, ITC, TSA) and functional activity studies (cell viability, enzyme inhibition) provides conclusive evidence of biological activity. The integrated case study of PKMYT1 inhibitor HIT101481851 demonstrates how this comprehensive workflow effectively transitions from virtual screening to experimentally confirmed hits with therapeutic potential. By objectively comparing validation methodologies and their performance metrics, this guide equips researchers with a structured framework for advancing pharmacophore-derived compounds through the critical hit validation pipeline.

The Validation Toolkit: Methodologies for Assessing Pharmacophore Model Performance

In pharmacophore-based drug discovery, the journey from a virtual screen to a experimentally confirmed hit is fraught with potential for false positives. Rigorous validation strategies are therefore critical to assess the true predictive power of a computational model before committing costly experimental resources. This process typically employs known active and inactive molecules to benchmark performance, ensuring the model can generalize from its training data to novel compounds. The validation landscape is primarily divided into internal validation, which assesses model performance on data held out from the training process, and external validation (or test set prediction), which provides the ultimate test of generalizability using a completely independent dataset [22] [23] [24]. This guide objectively compares the performance, protocols, and applications of these two fundamental validation approaches, providing scientists with the data needed to select and implement the most effective strategy for their research.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Validation Strategies

The choice between internal and external validation is not merely procedural; it has a direct and measurable impact on the reported performance and real-world applicability of a pharmacophore model. The following analysis synthesizes performance data from multiple studies to highlight key trends and differences.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Internal vs. External Validation in Recent Studies

| Study / Therapeutic Area | Model Type | Internal Validation Performance (AUC/c-index) | External Validation Performance (AUC/c-index) | Performance Delta |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression Risk Prediction [22] | Logistic Regression | 0.769 | 0.736 - 0.794 | -0.033 to +0.025 |

| Osteoporosis Risk Prediction [23] | Logistic Regression | 0.687 (95% CI: 0.674-0.700) | 0.679 (95% CI: 0.657-0.701) | -0.008 |

| CVD Mortality Prediction [24] | Gradient Boosting Survival | 0.837 (95% CI: 0.819-0.853) | N/A (Internal validation only) | N/A |

| SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 Inhibitors [15] | Pharmacophore Screening | N/A (Docking-based) | Experimental hit rate: 13 novel micromolar inhibitors | N/A |

The data reveals that a robust internal validation performance is a necessary but not sufficient condition for model success. A key observation from the depression risk study is that a well-constructed model can maintain stable performance upon external validation, with the external AUC (0.736-0.794) closely bracketing the internal AUC (0.769) [22]. This indicates minimal model overfitting. Conversely, even a modest performance drop upon external validation, as seen in the osteoporosis study, can be informative, highlighting subtle differences in population characteristics or data collection protocols between the development and external validation cohorts [23].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

A clear, reproducible experimental protocol is the foundation of credible validation. The following methodologies are adapted from recent high-impact studies.

Protocol for Internal Validation

The following workflow is standard for rigorous internal validation, often implemented via k-fold cross-validation or a single split into training and validation sets.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Computational Validation

| Research Reagent / Resource | Function in Validation | Example Sources/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Known Active Compounds | Serve as positive controls to test the model's ability to identify true binders. | ChEMBL, ZINC, PubChem [6] |

| Known Inactive/Decoy Compounds | Act as negative controls to test the model's ability to reject non-binders. | DUD-E, DEKOIS 2.0 |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software (e.g., LigandScout) | Used to generate and validate pharmacophore queries based on structural data. | Inte:ligand LigandScout [15] [6] |

| Conformational Database Generator (e.g., CONFORGE) | Generates multiple 3D conformations of molecules for pharmacophore mapping. | CONFORGE software [6] |

| Crystallographic Fragment Datasets (e.g., XChem) | Provides experimental data on weak binders for model building and testing. | XChem facility, Diamond LightSource [15] |

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Data Curation and Splitting: Compile a dataset of known actives and inactives. Randomly split this dataset into a training set (typically 70-80%) and an internal validation/test set (20-30%) [22] [23]. Ensure that the distributions of key molecular properties are similar between splits.

- Model Training: Use only the training set to build the pharmacophore model. This may involve identifying common pharmacophore features from a set of active ligands or creating a structure-based model from a protein-ligand complex.

- Internal Performance Assessment: Apply the finalized model to the held-out internal validation set. Calculate performance metrics such as AUC, enrichment factors, and early recall to quantify its discriminative power between known actives and inactives.

- Iterative Refinement (Optional): Based on the internal validation results, the model may be refined. However, the validation set must not be used for training, or the results will be optimistically biased.

Protocol for External Validation

External validation provides the most credible estimate of a model's real-world utility. The protocol for the depression risk prediction study offers a robust template [22].

Step-by-Step Workflow:

- Independent Cohort Selection: Secure a dataset that is entirely independent of the training data. This should come from a different source, such as a separate research institution, a different time period, or a distinct compound library [22] [23]. For the depression model, three separate external validation cohorts were used.

- Blinded Prediction: Apply the fully finalized model—without any further tuning or retraining—to this external set. It is critical that the model is treated as a fixed tool at this stage.

- Experimental Corroboration: The ultimate external validation for a pharmacophore model is experimental testing. As demonstrated in the SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 study, top-ranked virtual hits from the screen are procured or synthesized and tested in functional assays (e.g., ThermoFluor, cellular antiviral assays) to determine a true experimental hit rate [15].

- Performance Benchmarking: Calculate the same performance metrics (AUC, etc.) on the external set. A significant drop in performance suggests the model may have been overfitted to the training data or that the external set is fundamentally different.

Discussion: Strategic Implementation in Drug Discovery

The comparative data indicates that internal and external validation are complementary, not interchangeable. Internal validation is an efficient, necessary tool for model development and refinement during the initial phases. It allows for the rapid comparison of different algorithms and feature sets. For example, a study might use internal validation to choose between a logistic regression model (AUC=0.769) and an XGBoost model (AUC=0.758) before proceeding further [22].

In contrast, external validation is a gatekeeper for model deployment and trust. Its primary value lies in establishing generalizability. The use of multiple external cohorts, as seen in the depression risk study, is a particularly robust practice, as it tests the model against a wider range of population variances [22]. In the context of pharmacophore screening, external validation is synonymous with experimental testing, which transforms a computational prediction into a tangible starting point for medicinal chemistry. The discovery of 13 novel micromolar inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 NSP13 via a FragmentScout pharmacophore workflow stands as a successful example of this principle [15].

Both internal validation and external test set prediction are indispensable in the rigorous evaluation of pharmacophore models. Internal validation provides a foundational check for overfitting and guides model selection, while external validation, particularly when coupled with experimental assay data, delivers the definitive proof of a model's predictive power and practical utility. The most effective drug discovery pipelines strategically employ both methods: using internal validation to build the best possible model, and external validation to confirm its value before allocating significant resources to experimental work. This two-tiered approach maximizes the likelihood of translating in silico predictions into biologically active lead compounds.

In the pipeline of computer-aided drug discovery, virtual screening serves as a critical filter to identify potential lead compounds from vast chemical libraries. A core component of this process is decoy set validation, a method used to rigorously assess the performance of computational models, such as pharmacophores, by testing their ability to distinguish known active compounds from presumed inactives [25]. The ultimate goal is to produce a model with high screening power—the ability to select true binders from a mixture of binders and non-binders—before committing resources to expensive experimental testing [26]. This guide objectively compares the methodologies and performance of decoy set validation across various drug discovery campaigns, focusing on the critical metrics of Enrichment Factor (EF) and Goodness of Hit (GH) score.

Core Concepts: EF and GH Scores

The performance of a pharmacophore model in virtual screening is quantitatively assessed using two primary metrics: the Enrichment Factor (EF) and the Goodness of Hit (GH) score.

Enrichment Factor (EF): This metric measures how much better a model is at identifying active compounds compared to a random selection. It is defined as the ratio of the fraction of actives found in the hit list to the fraction of actives in the entire database [27] [28]. A higher EF indicates better performance.

Goodness of Hit Score (GH): This score provides a more holistic assessment by integrating the yield of actives, the model's ability to skip inactives, and the coverage of actives in the database. The GH score ranges from 0 (a null model) to 1 (an ideal model) [27]. A model is generally considered very good when the GH score exceeds 0.7 [27].

The mathematical definitions for these metrics, as consistently reported across multiple studies, are as follows [27] [29] [28]:

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | ( EF = \frac{(Ha / Ht)}{(A / D)} ) | Measures fold-improvement over random selection. |

| Goodness of Hit (GH) Score | ( GH = \frac{Ha}{A} \times \left( \frac{3A + Ht}{4Ht} \right) \times \left(1 - \frac{Ht - Ha}{D - A}\right) ) | Integrated score (0-1) of model quality. |

Where:

- Ht = Total number of hits retrieved from the database

- Ha = Number of active compounds in the hit list

- A = Total number of active compounds in the database

- D = Total number of molecules in the database

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and relationships in decoy set validation, from set creation to model evaluation:

Experimental Protocols for Decoy Validation

A standardized protocol for conducting decoy set validation is critical for generating comparable and meaningful results. The following workflow, synthesized from multiple studies, outlines the key steps.

Decoy Set Construction and Virtual Screening Workflow

The validation of a pharmacophore model through decoy screening follows a systematic sequence of steps. Adherence to this protocol ensures the reliability of the resulting EF and GH scores.

Key Methodological Details

Decoy Selection: Decoys are compounds chosen for their similar physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, logP) to the active compounds, but with different chemical structures to minimize the probability of actual binding [26] [30]. This ensures the model is challenged in a realistic manner. Common sources for decoys include:

- ZINC15: A large commercial compound library often used for random decoy selection [26].

- DUD-E (Directory of Useful Decoys - Enhanced): A dedicated database that provides carefully selected decoys for many biological targets, designed to avoid latent actives [28].

- Dark Chemical Matter (DCM): Compounds that have been tested repeatedly in high-throughput screens but never shown activity, providing high-confidence inactives [26].

Model Scoring: After virtual screening, the retrieved hit list is analyzed. The EF and GH scores are calculated using the standard formulas. The model's ability to rank active compounds early in the hit list (a key aspect of screening power) is often visualized using Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and quantified by the Area Under the Curve (AUC) [29] [25].

Comparative Performance Analysis

The table below summarizes the EF and GH scores from various pharmacophore modeling studies, demonstrating the application and typical performance ranges of these metrics across different protein targets.

| Target Protein | Model Type | EF | GH Score | Key Outcome & Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akt2 [27] [31] | Structure-Based | 69.57 | 0.72 | High EF and good GH; model is very good (GH > 0.7) for virtual screening. |

| FAK1 [28] | Structure-Based | Reported | Reported | Model successfully identified novel inhibitors; specific EF/GH values were part of the model selection criteria. |

| COX-2 [29] | Ligand-Based | Reported | Reported | Model showed high sensitivity and specificity; EF and GH were key validation metrics before virtual screening. |

| TGR5 [32] | Ligand-Based | Calculated | Calculated | The decoy test method with 30 actives and 570 decoys was used to validate the pharmacophore hypothesis. |

| Class A GPCRs [33] | Structure-Based (Automated) | Theoretical Max (8/8 targets) | N/R | Achieved maximum theoretical enrichment, indicating high performance in a prospective method. |

Abbreviation: N/R = Not Reported

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

A successful decoy validation experiment relies on a suite of computational tools and databases. The following table lists key resources used in the featured studies.

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in Validation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| ZINC / ZINC15 Database [26] [32] | Source of purchasable compounds for virtual screening and decoy generation. | Providing millions of molecules for screening and decoy sets [32]. |

| DUD-E Database [29] [28] | Provides pre-generated sets of active compounds and matched decoys for many targets. | Supplying 114 active and 571 decoy compounds for FAK1 pharmacophore validation [28]. |

| LUDe Tool [30] | Open-source tool for generating decoy sets with low risk of artificial enrichment. | Generating challenging decoys for benchmarking virtual screening models. |

| Pharmit [28] | Web-based platform for pharmacophore modeling, validation, and virtual screening. | Creating and validating structure-based pharmacophore models for FAK1. |

| Discovery Studio [27] [32] | Software suite with dedicated modules for pharmacophore modeling and virtual screening. | Generating 3D-QSAR and common feature pharmacophore models [27] [32]. |

The consistent application of EF and GH scoring across diverse targets, from kinases like Akt2 to GPCRs, underscores their role as indispensable, standardized metrics for validating the screening power of pharmacophore models. The experimental data confirms that a GH score > 0.7 is a robust indicator of a high-quality model suitable for virtual screening [27]. The ongoing development of advanced decoy selection strategies—such as using dark chemical matter [26] and tools like LUDe [30]—aims to further reduce bias and create more challenging validation sets. As the field progresses, the integration of these rigorous validation protocols with machine learning approaches [26] and their extension to novel target classes like RNA [34] will continue to enhance the reliability and success rate of structure-based drug discovery.