From Data to Diagnosis: A Roadmap for Clinically Validating cfDNA Machine Learning Models

The integration of machine learning (ML) with cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis holds transformative potential for non-invasive cancer detection, therapy selection, and monitoring.

From Data to Diagnosis: A Roadmap for Clinically Validating cfDNA Machine Learning Models

Abstract

The integration of machine learning (ML) with cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis holds transformative potential for non-invasive cancer detection, therapy selection, and monitoring. However, translating these models from research to clinical practice requires rigorous validation in real-world cohorts. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational biology of cfDNA, state-of-the-art ML methodologies, strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls, and robust validation standards. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this guide aims to accelerate the development of reliable, clinically actionable cfDNA-based ML tools for precision oncology.

The Bedrock of cfDNA: Understanding Biology and Biomarkers for Machine Learning

Cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis has revolutionized non-invasive diagnostic approaches, enabling insights into human health and disease through a simple blood draw. The field of fragmentomics investigates the unique physical and molecular characteristics of these DNA fragments, leveraging the fact that their breakdown is not a random process. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three cornerstone fragmentomic features—nucleosome positioning, fragment size, and end motifs—focusing on their biological origins, measurement methodologies, and performance in clinical biomarker development. As machine learning models increasingly integrate these features for disease detection, understanding their individual and combined strengths, validated against large clinical cohorts, is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals.

Biological Foundations of cfDNA Fragmentomics

The landscape of cfDNA in the bloodstream is a mosaic of DNA fragments originating from various cell types. The composition and structure of these fragments are directly influenced by the biological processes within their cells of origin.

- Cellular Death and Chromatin Digestion: cfDNA is primarily released into the circulation during apoptotic cell death. During apoptosis, apoptotic nucleases systematically digest cellular chromatin. These enzymes preferentially cleave the linker DNA between nucleosomes, while the DNA wrapped around the histone core is protected. This process results in a population of DNA fragments whose ends and lengths carry an imprint of the nuclear architecture of the source cell [1] [2].

- Nucleosome Positioning as a Cellular Blueprint: The genomic positioning of nucleosomes is highly cell-type-specific, reflecting the unique epigenetic and transcriptional state of the cell [3] [1]. Genes that are actively transcribed or regulated by specific transcription factors exhibit distinct nucleosome occupancy patterns at their promoters and enhancers. Consequently, the nucleosome footprint recovered from cfDNA sequencing can be used to infer the relative contributions of different tissues to the circulating DNA pool, a principle foundational to "nucleosomics" [1].

- Transcription Factor Footprinting: In addition to nucleosomes, other DNA-binding proteins like transcription factors can protect DNA from nuclease digestion. This results in very short DNA fragments that footprint the binding sites of these regulatory factors, providing an additional layer of functional genomic information [3] [4].

The following diagram illustrates the journey of cfDNA, from its origin in the nucleus to its analysis in the laboratory, highlighting the key fragmentomic features covered in this guide.

Comparative Analysis of Key Fragmentomic Features

Table 1: Comparative overview of key cfDNA fragmentomic features.

| Feature | Biological Basis | Primary Measurement Method(s) | Key Clinical Performance Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleosome Positioning | Cell-type-specific nucleosome architecture protected from nuclease digestion [3] [1]. | Window Protection Score (WPS) [5], Promoter/Enhancer Coverage [4] [6], Coverage at ATAC-seq peaks [4]. | Ovarian Cancer: AUC improvement when combined with CNA scores [2].Preterm Birth (PTerm): AUC 0.849 in validation cohorts [6]. |

| Fragment Size | DNA cleavage periodicity around nucleosomes (10.4 bp) and protection by chromatosome (~167 bp) [3] [5]. | Fragment Length Distribution, Proportion of short fragments (<150 bp) [7], DELFI score [5] [7]. | Multi-Cancer Detection (DELFI): High performance in targeted panels [7].Cancer Detection: Short fragment proportion is a key metric [7]. |

| End Motifs | Sequence-specific cleavage preferences of DNase enzymes (e.g., DNASE1L3) [4]. | Frequency of 4-mer sequences at fragment ends, Motif Diversity Score (MDS) [5] [7]. | HCC vs. Healthy: Distinct end motif patterns [5].Cancer Typing: MDS at all exons was top metric for SCLC detection [7]. |

Nucleosome Positioning

Experimental Protocol for Nucleosome Footprinting: A standard protocol for inferring nucleosome positioning from cfDNA Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) data involves:

- LC-WGS: Perform low-coverage (e.g., 0.1x-1x) whole-genome sequencing of plasma cfDNA [6] [2].

- Read Alignment: Map sequenced reads to a reference human genome.

- Fragment Boundary Mapping: Extract the start and end coordinates of all cfDNA fragments.

- Nucleosome Score Calculation: Compare the fragment boundary profile to a reference set of known nucleosome positions (e.g., from healthy individuals) [2]. One common method is to calculate the distance from each fragment start to the nearest reference nucleosome center, generating an M-shaped distribution. Deviations from the healthy reference profile can be quantified using multinomial modeling to generate a nucleosome footprint score for each sample [2].

Fragment Size

Experimental Protocol for Fragment Size Analysis:

- High-Quality Data Generation: Sequence cfDNA (WGS or targeted) and retain only high-quality, uniquely mapped, non-duplicate reads [5].

- Fragment Length Calculation: Compute the insert size for each paired-end read.

- Genome-Wide Distribution: Plot the frequency distribution of all fragment lengths, which typically shows a peak at ~167 bp (mononucleosome) and smaller peaks at multiples thereof [3] [5].

- Feature Calculation: Calculate specific size-based metrics such as the proportion of fragments shorter than 150 bp, the ratio of long to short fragments in genomic windows, or the Shannon entropy of the size distribution in specific regions like gene exons [7].

End Motifs

Experimental Protocol for End Motif Analysis:

- Fragment End Extraction: From aligned BAM files, extract the first 4 nucleotides (4-mer) at both the 5' and 3' ends of each cfDNA fragment.

- Motif Frequency Calculation: Count the occurrence of each unique 4-mer sequence across all fragment ends in a sample.

- Motif Diversity Score (MDS): Calculate the MDS, which quantifies the heterogeneity of end motif usage. A higher MDS indicates greater diversity. This can be calculated genome-wide or within specific genomic intervals (e.g., 100 kb bins) to increase feature resolution [5].

- Differential Analysis: Identify end motifs that are significantly over- or under-represented in case samples (e.g., cancer patients) compared to healthy controls.

Table 2: Performance comparison of fragmentomic features across cancer types and detection limits.

| Feature Category | Specific Metric | Cancer Type / Condition | AUC / Performance | Detection Limit / Tumor Fraction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleosome Positioning | Promoter Profiling (PTerm) | Preterm Birth [6] | AUC 0.849 (Validation) | N/A |

| Nucleosome Positioning | Nucleosome Footprint Score | Ovarian Cancer [2] | Improved detection when combined with CNA | Complements CNA-low tumors |

| Fragment Size | Normalized Depth (All Exons) | Multi-Cancer (Targeted Panel) [7] | Avg. AUROC 0.943-0.964 | Varies by type (e.g., NSCLC: 0.873) |

| End Motifs | MDS (All Exons) | Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC) [7] | AUROC 0.888 | Specific to SCLC |

| End Motifs | End Motif Frequency | Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) [5] | Pattern significantly different from healthy | Data from patient plasma |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational tools for cfDNA fragmentomics.

| Item / Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in cfDNA Fragmentomics |

|---|---|---|

| TALEs (Transcription Activator-Like Effectors) [8] | Protein Reagent | Engineered to specifically bind methylated DNA sequences, enabling enrichment and detection of methylation patterns in fragmentomics. |

| DNASE1L3 [4] | Enzyme | An apoptotic nuclease whose cleavage preference is reflected in cfDNA end motifs (e.g., CCNN motif). |

| ATAC-seq Peaks [4] | Genomic Reference | Reference maps of open chromatin regions used to interpret cfDNA enrichment patterns and infer cell-of-origin. |

| FinaleToolkit [5] | Computational Tool | A fast, memory-efficient Python package for generating comprehensive fragmentation features (WPS, end motifs, MDS) from large cfDNA sequencing datasets. |

| NucPosDB [1] | Database | A curated database of in vivo nucleosome positioning and cfDNA sequencing datasets for fundamental and clinical research. |

| XGBoost [4] | Machine Learning Model | An interpretable ML algorithm used to train classifiers on cell-type-specific open chromatin features derived from cfDNA for cancer detection. |

Integration into Machine Learning Models and Clinical Validation

The true power of fragmentomic features is realized when they are integrated into machine learning models and rigorously validated in clinical cohorts.

Feature Combination Enhances Performance: Models that combine multiple fragmentomic features consistently outperform those relying on a single feature type. For instance, combining nucleosome footprint scores with copy number alteration (CNA) scores improved the pre-surgical diagnosis of invasive ovarian cancer, with nucleosome scoring being particularly effective for tumors characterized by low chromosomal instability [2]. Similarly, a comprehensive approach using normalized depth, fragment sizes, and end motifs across all exons of a targeted panel achieved high AUROCs (up to 0.964) for multi-cancer detection [7].

Interpretability and Biologically Informed Features: Using biologically informed features, such as signals from cell-type-specific open chromatin regions, not only improves cancer detection accuracy but also enhances model interpretability. This allows researchers to identify key genomic loci associated with the disease state, providing actionable biological insights beyond a simple classification output [4].

Validation in Large, Independent Cohorts: Robust validation is critical for clinical translation. The PTerm classifier for preterm birth, based on cfDNA promoter profiling, was developed and validated in a large-scale, multi-center study involving 2,590 pregnancies, achieving an AUC of 0.849 in independent validation cohorts [6]. This demonstrates the stability and generalizability of fragmentomics-based models.

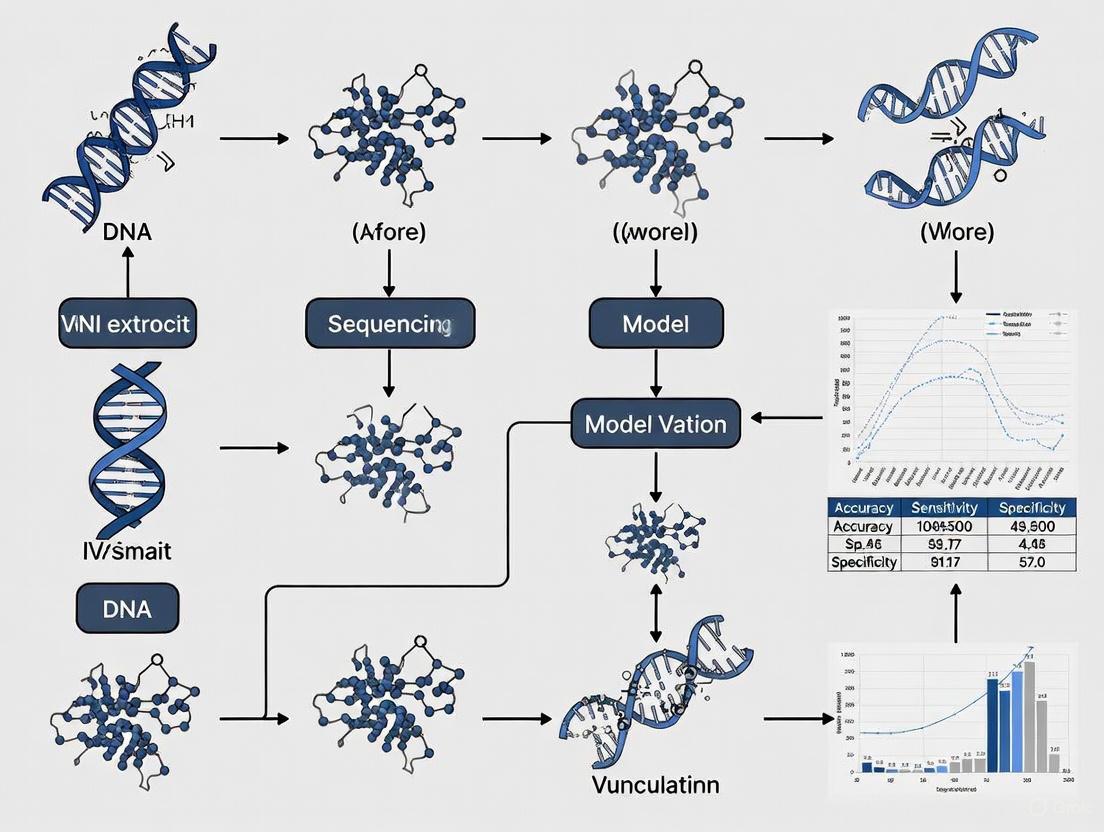

The following diagram summarizes the end-to-end workflow for building and validating a machine learning model using cfDNA fragmentomic features.

Tissue-of-origin (TOO) mapping for cell-free DNA (cfDNA) represents a transformative advancement in liquid biopsy, enabling non-invasive disease detection and monitoring. By deciphering the unique epigenetic and open chromatin signatures carried by cfDNA fragments, researchers can trace the cellular origins of these molecules, opening new frontiers in oncology, prenatal testing, and transplant monitoring. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the leading technological approaches in TOO mapping, focusing on their underlying mechanisms, performance characteristics, and clinical validation status. The field has evolved from genetic mutation-based analyses to sophisticated epigenetic profiling that captures the molecular footprints of active gene regulation across tissues. As these technologies mature, understanding their comparative strengths and technical requirements becomes essential for researchers and drug development professionals implementing liquid biopsy applications in clinical research and diagnostic development.

Comparative Analysis of TOO Mapping Technologies

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics and technical specifications of the primary TOO mapping approaches currently advancing in clinical research.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Major TOO Mapping Technologies

| Technology | Biological Target | Reported Sensitivity | Reported Specificity | Key Advantages | Clinical Validation Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open Chromatin Footprinting (TCI Method) | TSS coverage patterns of 2,549 tissue-specific genes [9] | High accuracy in pregnancy/transplant models [9] | Established reference intervals from 460 healthy individuals [9] | Simple, cost-effective, avoids bisulfite conversion [9] | Validated in healthy cohorts and specific clinical scenarios [9] |

| cfDNA Methylation Profiling | Genome-wide methylation patterns [10] | 88.1% for GI cancers (SPOGIT assay); detects early-stage (0-II) with 83.1% sensitivity [10] | 91.2% for GI cancers (SPOGIT assay) [10] | High sensitivity for early cancer detection; detects premalignant lesions [10] | Multicenter validation (n=1,079); projected to reduce late-stage diagnoses by 92% [10] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing (WGTS) | Combined mutation features, CNVs, SVs, and mutational signatures [11] | Informs TOO diagnosis in 71% of CUP cases unresolved by clinicopathology [11] | Detects additional reportable variants in 76% of cases vs. panels [11] | Comprehensive feature detection; superior to panel sequencing [11] | Feasibility demonstrated in 73 CUP tumors; informs treatment for 79% of patients [11] |

| cfDNA Fragmentomics | Fragment size ratios, CNV, and nucleosome footprint [12] | 90.5% for RCC detection; 87.8% for stage I RCC [12] | 93.8% for RCC detection; 100% for stage IV RCC [12] | Strong performance across cancer stages and subtypes [12] | Validation in 422 participants; presented at ASCO 2025 [12] |

Table 2: Technical Requirements and Resource Considerations

| Methodology | Minimum Input DNA | Sequencing Depth | Computational Requirements | Key Tissue Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open Chromatin Footprinting | Not specified | Not specified | TCI algorithm; 12 reference tissues [9] | 12 human tissues [9] |

| cfDNA Methylation (SPOGIT) | <30 ng [10] | Not specified | Multi-algorithm model (Logistic Regression/Transformer/MLP/Random Forest/SGD/SVC) [10] | Focused on gastrointestinal tract cancers [10] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing | Not specified | Not specified | CUPPA algorithm; complex bioinformatics pipeline [11] | Broad cancer type coverage [11] |

| cfDNA Fragmentomics | Not specified | 5X coverage (low-pass WGS) [12] | Stacked ensemble machine learning model [12] | Renal cell carcinoma and benign renal conditions [12] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Open Chromatin Footprinting with TCI Method

The Tissue Contribution Index (TCI) method leverages the principle that cfDNA coverage near transcription start sites (TSS) of actively transcribed genes decreases due to open chromatin accessibility. The protocol involves:

Reference Atlas Development: Identify 2,549 tissue-specific, highly expressed genes across 12 human tissues using resources like GTExv8 TPM values for bulk tissues [9].

Library Preparation and Sequencing: Plasma cfDNA is extracted and prepared for whole-genome sequencing without bisulfite conversion, preserving DNA integrity.

TSS Coverage Analysis: Map sequencing reads around TSS regions (±1 kb) to generate coverage profiles, with decreased coverage indicating open chromatin regions.

TCI Calculation: Apply the TCI algorithm to quantify tissue contributions by comparing observed TSS coverage patterns against the reference tissue atlas.

Validation: Establish reference intervals using plasma cfDNA from healthy individuals (n=460) and validate in specific clinical contexts such as pregnancy and transplantation [9].

Whole Genome and Transcriptome Sequencing for CUP

For cancers of unknown primary (CUP), the WGTS approach provides comprehensive molecular profiling:

Sample Preparation: Utilize FFPE or fresh tissue samples, with FFPE samples requiring additional quality control measures due to shorter fragment lengths and higher duplication rates [11].

Sequencing: Perform whole genome sequencing at sufficient depth to detect SNVs, indels, CNVs, and SVs, complemented by whole transcriptome sequencing where RNA quality permits.

Variant Calling and Analysis: Employ specialized tools for different variant types:

- SNVs/Indels: Standard mutation calling pipelines

- CNVs: PURPLE tool with adjustment for FFPE-derived noise [11]

- SVs: Structural variant callers optimized for complex rearrangements

TOO Prediction: Apply the CUP prediction algorithm (CUPPA) trained on WGTS data of known cancer types, incorporating driver mutations, passenger mutations, and mutational signatures [11].

Clinical Interpretation: Integrate molecular features with pathological assessment to resolve tissue of origin and inform treatment options.

cfDNA Methylation Analysis for Early Cancer Detection

The SPOGIT assay for gastrointestinal cancer detection exemplifies the methylation-based approach:

Assay Development: Identify informative methylation markers from large-scale public tissue methylation data and cfDNA profiles [10].

Library Preparation: Use capture-based approaches (e.g., Twist probe cfDNA profiles) to enrich for target regions, requiring as little as <30 ng of input cfDNA [10].

Multi-Algorithm Modeling: Apply an ensemble of machine learning models (Logistic Regression, Transformer, MLP, Random Forest, SGD, SVC) to analyze methylation patterns [10].

Cancer Signal Origin Prediction: Implement a complementary CSO model to localize the primary site with 83% accuracy for colorectal cancer and 71% for gastric cancer [10].

Clinical Validation: Conduct rigorous multicenter validation focusing on early-stage cancers and precancerous lesions, with simulation analyses projecting clinical impact [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for TOO Mapping

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Single strand Adaptor Library Preparation (SALP-seq) | Single-stranded DNA library preparation for highly degraded DNA [13] | Esophageal cancer biomarker discovery from cfDNA [13] |

| Cell-free Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (cfRRBS) | Genome-scale methylation analysis from limited cfDNA input (6-10 ng) [14] | Early detection and monitoring of lung cancer [14] |

| Tn5 Transposase (Tagment DNA Enzyme) | Simultaneous fragmentation and tagging of DNA for ATAC-seq libraries [15] | Chromatin accessibility mapping in brain and endocrine tissues [15] |

| Boruta Feature Selection Algorithm | Random forest-based feature selection identifying all relevant predictors [16] | Cardiovascular risk prediction in diabetic patients; applicable to methylation marker selection [16] |

| Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) | Handling missing data in clinical datasets through iterative imputation [16] | Addressing incomplete clinical variables in patient cohorts [16] |

| Illumina Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs) | Multiplexing samples while minimizing index hopping in NGS [15] | ATAC-seq library preparation for chromatin accessibility studies [15] |

Clinical Validation and Machine Learning Framework

Robust clinical validation of cfDNA-based TOO models requires addressing temporal dynamics in clinical data. A comprehensive diagnostic framework should incorporate:

Temporal Validation: Partition data from multiple years into training and validation cohorts to assess model longevity and performance consistency [17].

Drift Characterization: Monitor temporal evolution of patient characteristics, outcomes, and feature distributions that may impact model performance [17].

Feature Stability Analysis: Apply data valuation algorithms and feature importance methods (e.g., SHAP analysis) to identify stable predictors across time periods [17] [16].

Ensemble Approaches: Combine multiple algorithms to enhance robustness, as demonstrated by the SPOGIT assay's use of six different machine learning models [10].

For CUP patients, WGTS-informed treatment decisions have demonstrated clinical utility, with molecular profiling informing treatments for 79% of patients compared to 59% by panel testing [11]. This highlights the tangible clinical impact of comprehensive TOO mapping in difficult-to-diagnose cancers.

The evolving landscape of TOO mapping technologies offers researchers multiple pathways for leveraging epigenetic and open chromatin signatures in clinical liquid biopsy applications. Open chromatin footprinting provides a bisulfite-free, cost-effective approach particularly valuable for monitoring tissue damage and transplantation. Methylation-based profiling demonstrates superior sensitivity for early cancer detection and interception of premalignant progression. Whole genome sequencing offers the most comprehensive feature detection for complex diagnostic challenges like CUP, while fragmentomics emerges as a promising approach with minimal input requirements. The selection of an appropriate TOO mapping technology must consider clinical context, sample availability, and computational resources, with rigorous temporal validation essential for successful clinical implementation. As these technologies continue to mature, they hold immense potential to transform cancer diagnosis, monitoring, and personalized treatment strategies.

The analysis of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) has emerged as a cornerstone of precision oncology, enabling non-invasive access to tumor-derived genetic and epigenetic information. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), the fraction of cfDNA originating from cancer cells, carries tumor-specific alterations that provide a real-time snapshot of tumor burden and heterogeneity [18] [19]. The clinical utility of cfDNA analysis spans the entire cancer care continuum, from early detection and diagnosis to therapy selection and monitoring of minimal residual disease (MRD) [20] [21]. However, the full potential of cfDNA is only realized through advanced computational approaches that can decipher the complex biological signals embedded within these fragments.

Machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies have become indispensable for integrating the high-dimensional features derived from cfDNA analysis, including genetics, epigenetics, and fragmentomics [22]. These computational approaches leverage patterns in cfDNA characteristics—such as fragment length distributions, end motifs, nucleosome positioning, and genomic distributions—to develop classifiers capable of detecting cancer, identifying its tissue of origin, monitoring treatment response, and distinguishing tumor-derived signals from confounding sources like clonal hematopoiesis [22] [23] [7]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of how ML-powered cfDNA analysis is addressing critical clinical needs, with a focus on performance validation across diverse clinical applications and cohorts.

Comparative Performance of cfDNA ML Models Across Clinical Applications

Table 1: Performance comparison of ML-based cfDNA models across key clinical applications

| Clinical Application | ML Approach | Key Features | Performance Metrics | Validation Cohort | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer Detection | Fragmentome classifier | Genome-wide cfDNA fragmentation patterns | High sensitivity; Consistent across demographics/comorbidities [24] | 958 LDCT-eligible individuals (382 in validation) [24] | Blood-based adjunct to improve LDCT screening uptake [24] |

| MRD Monitoring | Tumor-informed vs. tumor-agnostic | Patient-specific mutations (informed) vs. computational ctDNA quantification (agnostic) | Tumor-informed: Higher sensitivity, especially early-stage [18] | Clinical experience across cancer types [18] | Detection of molecular relapse before clinical recurrence [18] [19] |

| Variant Origin Classification | MetaCH meta-classifier | Variant/gene embeddings, functional prediction scores, VAF, cancer type [23] | Superior auPR vs. base classifiers across 4 validation datasets [23] | External cfDNA datasets with matched WBC sequencing [23] | Distinguishes clonal hematopoiesis from true tumor variants in plasma-only samples [23] |

| Multi-Cancer Phenotyping | GLMnet elastic net | Normalized fragment read depth across exons [7] | AUROC: 0.943 (UW cohort), 0.964 (GRAIL cohort) [7] | 431 samples (UW), 198 samples (GRAIL) [7] | Accurate cancer type and subtype classification from targeted panels [7] |

Table 2: Fragmentomics metric performance for cancer phenotyping on targeted sequencing panels

| Fragmentomics Metric | UW Cohort AUROC (Range) | GRAIL Cohort AUROC (Range) | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normalized depth (all exons) | 0.943 (0.873-0.986) [7] | 0.964 (0.914-1.000) [7] | Best overall performance across cancer types [7] |

| Normalized depth (E1 only) | 0.930 (0.838-0.989) [7] | N/R | Strong performance, slightly inferior to all exons [7] |

| Normalized depth (full gene) | 0.919 (0.828-0.993) [7] | N/R | Combines all exons from one gene [7] |

| End motif diversity (all exons) | Variable (Best for SCLC: 0.888) [7] | N/R | Superior for specific cancer types (e.g., SCLC) [7] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Fragmentomics Analysis for Early Cancer Detection

The DELFI-L101 study (NCT04825834) demonstrated a robust protocol for developing and validating a fragmentome-based lung cancer detection test [24]. This multicenter, prospective case-control study enrolled 958 individuals eligible for lung cancer screening according to USPSTF guidelines. The study employed a split-sample approach, with approximately 60% of subjects (n=576) used for classifier training and the remaining 40% (n=382) for independent clinical validation [24].

The experimental workflow involved: (1) collection of peripheral blood samples from all participants; (2) extraction and low-coverage whole-genome sequencing of cfDNA; (3) analysis of genome-wide cfDNA fragmentation profiles (fragmentomes); (4) training of a machine learning classifier on fragmentome features from the training set; and (5) locking the classifier model before performance assessment in the validation set [24]. This methodology specifically leveraged the fact that changes to genomic architecture in cancer cells result in abnormal genome-wide patterns of cell-free DNA in circulation, with fragmentation patterns reflective of specific chromatin configurations of the cells and tissues of origin [24].

ML Framework for Distinguishing Clonal Hematopoiesis

The MetaCH framework addresses the critical challenge of distinguishing clonal hematopoiesis (CH) variants from true tumor-derived mutations in plasma-only samples [23]. This open-source machine learning framework processes variants through three stages:

- Feature Extraction: Variants, genes, and functional impacts are numerically represented using the Mutational Enrichment Toolkit (METk), which generates: variant embeddings (E~v~) based on sequence context, associated gene, and cancer type; gene embeddings (E~g~) capturing patterns of genes with variants within individual patients; and functional prediction scores (E~f~) quantifying the impact of non-synonymous variants on gene function [23].

- Base Classifier Training: Three binary classifiers are trained: (i) a cfDNA-based classifier using features from METk plus variant allele frequencies and cancer type; (ii) sequence-based classifiers trained on public datasets of CH and somatic tumor variants to predict CH-oncogenic and CH-non-oncogenic variants [23].

- Meta-Classification: A meta-classifier applies logistic regression to combine scores from the base classifiers into a final probability that a variant originates from CH [23].

The framework was validated using cross-validation of training samples and external validation across four independent cfDNA datasets with matched white blood cell sequencing, demonstrating superior performance compared to existing approaches [23].

MetaCH Framework Workflow: This diagram illustrates the three-stage MetaCH framework for classifying variant origin in cfDNA samples without matched white blood cell sequencing.

Fragmentomic Analysis on Targeted Sequencing Panels

Recent research has demonstrated that fragmentomics analysis can be effectively performed on targeted sequencing panels commonly used in clinical settings, rather than requiring whole-genome sequencing [7]. The experimental approach involves:

- Sequencing Data Processing: Targeted panel sequencing data from cfDNA samples is processed to extract fragment-level information including size, genomic coordinates, and sequence characteristics [7].

- Multi-Metric Fragmentomics Analysis: Thirteen different fragmentomics metrics are calculated, including: (A) fragment length proportions and diversity metrics; (B) normalized fragment read depth; (C) end motif diversity score; (D) fragments overlapping transcription factor binding sites; and (E) fragments overlapping open chromatin sites [7].

- Model Training and Validation: An elastic net model (GLMnet) with 10-fold cross-validation is used to predict cancer type and subtype based on these fragmentomics features, with performance assessed using area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) [7].

This approach has been validated across two independent cohorts—the University of Wisconsin cohort (431 samples) and the GRAIL cohort (198 samples)—demonstrating that normalized fragment read depth across all exons generally provides the best predictive performance for cancer phenotyping [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key research reagents and solutions for cfDNA ML model development

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Targeted Sequencing Panels | Capture and sequence specific genomic regions of interest | FoundationOne Liquid CDx (309 genes), Guardant360 CDx (55 genes), Tempus xF (105 genes) [7] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Tag individual DNA molecules to correct for PCR and sequencing errors | Suppression of technical artifacts in variant calling [19] [25] |

| Whole Genome Sequencing | Provide genome-wide coverage for fragmentomics analysis | DELFI approach for cancer detection and tissue of origin identification [24] |

| Methylation Atlas | Reference database for tissue-specific methylation patterns | Tissue-of-origin tracing of cfDNA; 39 cell types from 205 healthy tissue samples [22] |

| Error Correction Methods | Improve sequencing accuracy and reduce false positives | Duplex Sequencing, SaferSeqS, NanoSeq, Singleton Correction, CODEC [19] |

Technical Considerations and Implementation Challenges

Biological and Analytical Variables

The effective implementation of cfDNA-based ML models requires careful consideration of several biological and technical factors. The concentration and characteristics of cfDNA are influenced by multiple variables including age, gender, organ health, medication status, physical activity, and other individual factors [20]. Additionally, the half-life of cfDNA in circulation is estimated between 16 minutes and several hours, enabling real-time monitoring but also introducing temporal variability [19] [20].

From an analytical perspective, distinguishing true tumor-derived variants from those arising from clonal hematopoiesis remains a significant challenge. CH variants can comprise over 75% of cfDNA variants in individuals without cancer and more than 50% of variants in those with cancer [23]. Methods that rely on matched white blood cell sequencing are considered the gold standard but are often cost-prohibitive and impractical for routine clinical implementation [23].

Performance Across Commercial Panels

Fragmentomics-based cancer detection performance varies when applied to different commercial targeted sequencing panels. Research indicates that panels with larger gene content generally provide better performance, with the FoundationOne Liquid CDx panel (309 genes) outperforming smaller panels like Tempus xF (105 genes) and Guardant360 CDx (55 genes) in fragmentomics-based cancer classification [7]. However, even smaller panels maintain reasonable performance for many applications, suggesting that fragmentomics analysis can be successfully implemented across various clinical-grade panels.

cfDNA Fragmentomics Workflow: This diagram outlines the key steps in processing cfDNA samples for fragmentomics analysis, from blood draw to clinical interpretation.

Machine learning models applied to cfDNA analysis have demonstrated substantial progress in addressing critical clinical needs across the cancer care continuum. Currently, the most validated applications include cancer detection using fragmentomics patterns, particularly in lung cancer screening contexts [24], and monitoring treatment response through ctDNA dynamics [19] [21]. The discrimination of clonal hematopoiesis variants using ML approaches like MetaCH shows promising results but requires further validation in larger prospective cohorts [23].

For clinical implementation, tumor-informed MRD assays currently demonstrate superior sensitivity compared to tumor-agnostic approaches, especially in early-stage cancer settings where ctDNA fractions are minimal [18]. However, current evidence for MRD monitoring in early-stage breast cancer remains largely retrospective, highlighting the need for prospective clinical trials to establish clinical utility before routine adoption [18].

As the field advances, standardization of preanalytical steps, refinement of analysis strategies, and improved understanding of cfDNA biology will be crucial for translating these promising ML approaches into routine clinical practice. The integration of multi-omic features—including genetics, epigenetics, fragmentomics, and transcriptional data—through sophisticated machine learning models holds the potential to further enhance the sensitivity and specificity of cfDNA-based cancer management across all clinical applications.

The integration of machine learning (ML) with cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis represents a transformative advancement in noninvasive diagnostics for conditions such as cancer and fetal chromosomal aneuploidies [22]. As this field rapidly expands, a growing number of models with diverse architectures and objectives are being published. This surge necessitates a systematic, critical review to synthesize evidence, identify redundant research efforts, and inform the design of robust future studies [26]. This review aims to objectively compare the performance of existing ML models applied to cfDNA analysis, with a specific focus on their validation in clinical cohorts. By framing the comparison within the core requirements of Clear Objectives, Quantifiable Evaluation, and Well-Defined Extensibility [27], we provide a structured framework to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in avoiding redundancy and advancing the field through methodologically sound model development.

Methodology of the Systematic Review

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [26]. The process is summarized in Figure 1.

Research Question and Eligibility Criteria

The research question was structured using the PICO framework:

- Population/Problem: Clinical cohorts and studies involving cfDNA analysis.

- Intervention/Exposure: Application of machine learning models for diagnostic or prognostic purposes.

- Comparator: Alternative ML models or standard non-ML diagnostic methods.

- Outcome: Model performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, AUC), generalizability, and clinical validity.

Inclusion criteria encompassed peer-reviewed studies involving ML models applied to human cfDNA data for disease detection, classification, or monitoring. Exclusion criteria included review articles, conference abstracts without full data, studies not published in English, and those that did not validate findings in a clinical cohort.

Search Strategy and Study Selection

A comprehensive search was executed across multiple electronic databases, including MEDLINE, Embase, and CENTRAL, tailored to each platform's specific indexing terms and search features [26]. The search strategy combined key concepts using Boolean operators: ("cell-free DNA" OR "cfDNA" OR "circulating tumor DNA" OR "ctDNA") AND ("machine learning" OR "deep learning" OR "artificial intelligence") AND ("model" OR "framework" OR "prediction") [28].

Search results were imported into a reference manager, deduplicated, and screened in a two-stage process by two independent reviewers. The initial screening was based on titles and abstracts, followed by a full-text review of potentially eligible studies. Conflicts were resolved through consensus or by a third reviewer. The study selection process is documented in the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

Figure 1: PRISMA Flow Diagram of the Systematic Review Process. This diagram visualizes the stages of study identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and final inclusion [28].

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Data from included studies were extracted in duplicate using a standardized template. Key extracted information included: study author and year, clinical context (e.g., cancer type), model objective, ML algorithm used, input features (e.g., fragmentomics, epigenetics), cohort size, key performance metrics, and stated limitations.

The risk of bias in included studies was assessed using appropriate tools, such as the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for randomized trials or the QUADAS-2 for diagnostic studies [28]. The focus was on evaluating potential biases in patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing.

Core Principles for Evaluating cfDNA Machine Learning Models

To meaningfully compare models and avoid redundant research, evaluation must extend beyond simple performance metrics. The following principles provide a framework for critical appraisal.

Clear Objectives

A model's purpose must be precisely defined, as this dictates the choice of architecture and evaluation criteria [27]. In cfDNA analysis, common objectives include:

- Disease Detection: Differentiating cancer patients from healthy individuals using features like cfDNA fragmentation patterns [22] [4].

- Tissue of Origin Mapping: Pinpointing the origin of cfDNA, which is crucial for cancers of unknown primary [22].

- Deduction of Fetal/Tumor Fraction: Estimating the proportion of fetal or tumor-derived cfDNA in a sample, a critical factor for test sensitivity [22].

Quantifiable Evaluation

Performance metrics must be robust, statistically sound, and comparable across studies. This involves:

- Statistical Significance Testing: Using null hypothesis testing or paired t-tests to ensure performance differences between models are not due to random chance [29].

- Resampling Methods: Employing ten-fold cross-validation to assess model performance on different data splits and reduce overfitting [30] [29].

- Analysis of Learning Curves: Plotting training and validation error over time to diagnose overfitting (validation error increases while training error decreases) and identify the optimal stopping point [29].

Well-Defined Extensibility

A model's utility is determined by its performance beyond the initial training data. Extensibility involves:

- Generalization: Applying the model to independent, external validation cohorts to test its robustness [27].

- Knowledge Transfer: Assessing the model's ability to maintain performance when applied to related but distinct tasks, such as different cancer types or patient demographics [27].

Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Approaches in cfDNA Research

The following tables synthesize experimental data and methodologies from key studies applying ML to cfDNA analysis, highlighting how different approaches address the core principles.

Table 1: Comparison of ML Model Objectives and Architectures in cfDNA Studies

| Clinical Context | Model Objective | ML Algorithm(s) | Input Features | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast & Pancreatic Cancer Detection [4] | Cancer detection using chromatin features | XGBoost | Nucleosome enrichment at cell-type-specific open chromatin regions | Improved cancer prediction accuracy by leveraging open chromatin signals from both tumor and immune (CD4+ T-cell) cells. |

| Noninvasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT) & Cancer Liquid Biopsy [22] | Fetal DNA fraction deduction; Plasma DNA tissue mapping; Cancer detection & localization | Various ML/AI approaches (Review) | cfDNA genetics, epigenetics, transcriptomics, fragmentomics | ML can integrate high-dimensional cfDNA features to deduce tissue of origin and detect pathological states. |

| General Subject Classification [30] | Comparison of classification performance | RF, SVM (RBF kernel), LDA, kNN | Simulated data with varying features, sample size, correlation | For smaller, correlated feature sets, LDA outperforms others. SVM excels with larger feature sets and adequate sample size. |

Table 2: Experimental Protocols and Performance Metrics from Key Studies

| Study Context | Experimental Protocol Summary | Cohort Size (Training/Validation) | Key Performance Metrics | Extensibility Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer cfDNA Analysis [4] | 1. cfDNA isolated from patient plasma and cancer cell lines. 2. Sequencing libraries prepared and sequenced. 3. Nucleosome enrichment patterns analyzed at ATAC-seq peaks. 4. XGBoost trained on cell-type-specific open chromatin features. | 5 breast cancer patients, 6 healthy donors (cfDNA); Cell lines (T47D, KPL-1) | Model showed distinct improvement in cancer prediction accuracy for breast and pancreatic cancer. | Model identified key contributing genomic loci, providing interpretable, biologically grounded insights. |

| Model Comparison Study [30] | 1. Large-scale simulation of data with controlled factors (features, sample size, noise, etc.). 2. Models (RF, SVM, LDA, kNN) trained and evaluated using leave-one-out cross-validation. 3. Generalization errors compared across factor combinations. | Massive simulation study using high-performance computing | LDA: Best for small, correlated features. SVM (RBF): Superior for large feature sets (sample size ≥20). kNN: Improved with more features unless high data variability. | Performance guidelines provided for varying data characteristics, aiding model selection for new, specific problems. |

The data in these tables demonstrate that model performance is highly context-dependent. For instance, the choice between a simpler model like LDA and a more complex one like SVM depends on the dimensionality of the cfDNA feature set [30]. Furthermore, successful models increasingly leverage biologically informed features, such as open chromatin profiles, which not only boost accuracy but also enhance interpretability—a key consideration for clinical translation [4]. The experimental protocol for such analyses typically follows a workflow from sample collection to model interpretation, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: General Workflow for cfDNA Machine Learning Studies. This diagram outlines the common steps from biological sample collection to the generation of clinically actionable insights [22] [4].

Successful development and validation of ML models for cfDNA analysis rely on a suite of wet-lab and computational tools.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Key Resources for cfDNA ML Studies

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Plasma/Serum Samples | Source of cell-free DNA. | Requires careful collection and processing to avoid cellular DNA contamination [22]. |

| cfDNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality cfDNA from biofluids. | Critical for obtaining representative fragment size distributions [4]. |

| Library Prep Kits | Preparation of sequencing libraries from cfDNA. | Must be optimized for short, fragmented DNA; compatible with dual-indexing to reduce batch effects. |

| ATAC-seq/Specific Antibodies | Defining cell-type-specific open chromatin or histone modification maps. | Used to create reference feature sets for model training (e.g., cancer-specific enhancers) [4]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Training complex models and processing large-scale sequencing data. | Essential for running large-scale simulations and hyperparameter optimization [30]. |

| Experiment Tracking Tools | Logging parameters, code, data versions, and metrics for reproducibility. | Neptune.ai, TensorBoard; vital for comparing multiple parallel ML experiments [29]. |

| Reference Databases | Providing annotated genomes, methylation atlas, and variant databases. | High-resolution methylome atlases (e.g., [22]) are key for tissue-of-origin analysis. |

This systematic review underscores that avoiding redundancy in cfDNA ML model development requires a principled approach centered on clear objectives, quantifiable and statistically robust evaluation, and rigorous testing of extensibility. The comparative analysis reveals that there is no single best algorithm; the optimal choice depends on the specific clinical question, the nature and dimensionality of the cfDNA feature data, and the available sample size. Future work should prioritize the development of standardized, publicly available benchmark datasets to facilitate fair model comparisons [27]. Furthermore, the field will benefit from a stronger emphasis on interpretable ML and the integration of diverse biological features, which together will build the trustworthiness needed for these powerful models to transition into routine clinical practice.

Building the Model: Machine Learning Approaches and Feature Engineering for cfDNA Data

The analysis of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) via liquid biopsy has emerged as a transformative, non-invasive approach in oncology, enabling early cancer detection, treatment selection, and disease monitoring [31]. Machine learning (ML) models are pivotal for interpreting the complex, multi-dimensional features derived from cfDNA, such as fragmentomics patterns, copy number variations (CNVs), and nucleosome positioning [32]. The selection of an appropriate ML algorithm—from classical ensembles like XGBoost and Random Forests to sophisticated deep learning architectures—directly impacts the clinical utility of these models. However, given the high stakes of medical diagnostics, this selection cannot be based on performance metrics alone; it must be grounded in rigorous validation frameworks specific to clinical cohorts to ensure reliability, generalizability, and ultimately, patient safety [33] [34]. This guide provides an objective comparison of ML algorithms in the context of cfDNA analysis, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Algorithm Performance Comparison in Clinical cfDNA Studies

Different ML algorithms exhibit distinct strengths and weaknesses when applied to cfDNA data. The table below summarizes quantitative performance data from recent clinical studies and benchmarks, highlighting how algorithm choice affects key diagnostic metrics.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Algorithms in cfDNA Analysis

| Algorithm | Clinical Context | Performance Metrics | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | Time series forecasting [35]; Tumor type classification from genomic alterations [36] | Lower MAE & MSE vs. deep learning on stationary time series [35]; AUC 0.97 for 10-type tumor classification [36] | High performance on structured data; faster training than deep learning; handles feature importance well [35] [36] | May underperform on highly complex, non-stationary data where deep learning excels [35] |

| Random Forest (RF) | Time series forecasting [35] | Competitive performance, faster training than deep learning [35] | Robust to overfitting; provides feature importance [35] | Can be computationally heavy with many trees; may not match XGBoost's accuracy in some tasks [35] |

| Stacked Ensemble (XGBoost, GLM, DRF, Deep Learning) | Early detection of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (ESCC) using cfDNA fragmentomics [32] | AUC: 0.995 (Training), 0.986 (Independent Validation) [32] | Leverages strengths of multiple models; highly robust and accurate; performs well in low-coverage sequencing [32] | Complex to implement and tune; computationally intensive [32] |

| Recurrent Neural Network with LSTM (RNN-LSTM) | Time series forecasting [35] | Higher MAE & MSE vs. XGBoost on stationary vehicle flow data [35] | State-of-the-art for complex sequential data with long-range dependencies [35] | Can develop "smoother" predictions on stationary data; requires large data volumes; computationally costly [35] |

| Support Vector Machine (SVM) | Time series forecasting [35]; General model validation [34] | Competitive performance on time series [35] | Effective in high-dimensional spaces; versatile for classification and regression [34] | Performance is sensitive to kernel and hyperparameter choice [35] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols from Key Studies

Protocol 1: Stacked Ensemble Model for ESCC Detection

A study by Jiao et al. (2024) developed a robust stacked ensemble model for early ESCC detection using cfDNA fragmentomics, demonstrating a rigorous validation protocol [32].

- Objective: To develop a non-invasive assay for early detection of Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma (ESCC) that maintains high sensitivity and specificity, even in low-coverage whole-genome sequencing environments [32].

- Cohort Design: The study recruited 499 participants, split into a training cohort (n=207), an independent validation cohort (n=201), and an external validation cohort (n=91) to ensure generalizability [32].

- Feature Extraction: Four distinct fragmentomics features were extracted from low-pass whole-genome sequencing (5X coverage) of plasma cfDNA:

- Copy Number Variation (CNV): Identification of chromosomal arm-level gains and losses [32].

- Fragmentation Size Coverage (FSC): Analysis of genome-wide coverage patterns of cfDNA fragments [32].

- Fragmentation Size Distribution (FSD): Characterization of the length profile of cfDNA fragments [32].

- Nucleosome Positioning (NP): Mapping of nucleosome occupancy patterns, including identification of transcription factor-binding sites [32].

- Model Training and Stacking: Four base algorithms—XGBoost, Generalized Linear Model (GLM), Distributed Random Forest (DRF), and Deep Learning—were trained on the four fragmentomics features. Instead of using fixed hyperparameters, a random grid search was employed to select the top 10 best-performing base models for the stacking process. These base models' predictions were then combined to form the final stacked ensemble model [32].

- Validation: The model's performance was rigorously assessed on the independent validation and external cohorts, demonstrating consistent AUC, sensitivity, and specificity, thus confirming its robustness [32].

Protocol 2: XGBoost for Pan-Cancer Classification

A 2023 study developed an XGBoost model to classify tumor types based on somatic genomic alterations, showcasing the algorithm's power in handling large-scale, structured genomic data [36].

- Objective: To create a tool that can accurately distinguish between different cancer types based on somatic point mutations (SPMs) and copy number variations (CNVs) at the chromosome arm-level, which could aid in diagnosing cancers of unknown origin [36].

- Data Source and Transformation: Genomic data from 9,927 samples across 32 cancer types were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) via cBioportal. A Vector Space Model (VSM) transformation was applied, converting raw mutation and CNV data into a homogeneous dataset by counting the occurrences of SPMs and CNVs in the p-arm and q-arm of each chromosome for every sample [36].

- Model Training and Addressing Class Imbalance: An XGBoost classifier was trained on the transformed data. To handle the significant class imbalance between common and rare cancers, two strategies were employed:

- Training a model on the 10 most represented tumor types.

- Grouping the 18 most represented cancers into biologically relevant categories (endocrine-related carcinomas, other carcinomas, and other cancers) and training a specific XGBoost model for each group [36].

- Performance: The model achieved a balanced accuracy (BACC) of 77% and an AUC of 0.97 for the 10-tumor-type classification, demonstrating diagnostic potential comparable to or higher than other established methods [36].

Essential Validation Frameworks for Clinical cfML Models

Robust validation is non-negotiable for cfDNA machine learning models intended for clinical application. Proper validation ensures that performance estimates are unbiased and that the model will generalize to new, unseen patient cohorts [33] [34].

Table 2: Key Model Validation Techniques and Their Application in cfDNA Research

| Validation Technique | Core Principle | Application in cfDNA Clinical Cohorts | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Train/Test Split | Randomly split data into training (e.g., 70%) and testing (e.g., 30%) sets [33]. | A basic first step for initial performance estimation. | Prone to sampling bias if the single split is not representative of the overall cohort [33]. |

| k-Fold Cross-Validation (k-Fold CV) | Data is split into k folds (e.g., 5 or 10). The model is trained on k-1 folds and tested on the left-out fold, repeated for all k folds [33]. | Provides a more robust estimate of model performance by using all data for both training and testing. | The variance of scores across folds provides insight into model stability [33]. |

| Nested Cross-Validation | Uses two layers of k-fold CV: an inner loop for hyperparameter tuning and an outer loop for unbiased performance estimation [33]. | Crucial for avoiding optimistically biased performance estimates when tuning hyperparameters is part of the workflow. | Prevents data leakage from the tuning process into the evaluation process [33]. |

| Leave-One-Group-Out Cross-Validation (LOGOCV) | Each fold corresponds to an entire group (e.g., patients from a specific clinical center) [33]. | Ideal for validating model generalizability across multiple clinical sites in a multicenter trial. | Ensures the model is not relying on site-specific technical artifacts [33]. |

| Time-Series Split | Ensures that training data chronologically precedes test data in each split [33]. | Important for longitudinal cfDNA studies monitoring disease progression or treatment response. | Prevents over-optimism by respecting the temporal nature of the data [33]. |

| Statistical Significance Testing (e.g., Wilcoxon signed-rank test) | A non-parametric test applied to the k performance scores from two models to determine if one is significantly better [33]. | Allows for a statistically grounded comparison between two candidate cfDNA models, beyond simple average metric comparison. | Helps ensure that a perceived improvement is not due to random chance [33]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful development and validation of cfDNA machine learning models rely on a foundation of specific wet-lab and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for cfDNA ML Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Blood Collection Tubes (e.g., Streck, EDTA) | Stabilize blood cells to prevent lysis and release of genomic DNA that could dilute cfDNA [31]. | Standardized pre-analytical sample acquisition for all subjects in a clinical cohort. |

| cfDNA Extraction Kits | Isolate and purify cfDNA from plasma. Reproducible yield and purity are critical [31]. | Generating the input material for subsequent whole-genome sequencing. |

| Low-Pass Whole-Genome Sequencing (LP-WGS) | Sequences the entire genome at low coverage (e.g., 0.1-5X), sufficient for fragmentomics and CNV analysis [32] [12]. | A cost-effective method to generate fragmentomics features (CNV, FSC, FSD, NP) for model training. |

| Targeted Sequencing Panels | Focuses sequencing on specific genes or regions of interest at very high depth to detect rare mutations [31]. | Can be used to validate findings or as an alternative feature source for mutation-based models. |

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | A public repository containing multi-omics data from thousands of tumor samples [36]. | Serves as a benchmark dataset for training and testing pan-cancer classification models. |

| Python ML Libraries (e.g., scikit-learn, XGBoost, TensorFlow/PyTorch) | Open-source libraries that provide implementations of ML algorithms, from XGBoost to deep learning [33]. | The computational backbone for building, training, and validating all types of models discussed. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) | A game theory-based method to interpret the output of any ML model [35]. | Explainability analysis to identify which cfDNA features (e.g., specific CNVs) most influenced a model's prediction. |

The selection of a machine learning algorithm for cfDNA-based clinical research is a nuanced decision that balances performance, complexity, and interpretability. XGBoost and tree-based ensembles consistently demonstrate high accuracy and efficiency on structured genomic and fragmentomics data, often matching or surpassing the performance of more complex deep learning models in tasks like cancer classification and detection [32] [35] [36]. For the most challenging diagnostic problems, stacked ensemble models that leverage the strengths of multiple algorithms can provide superior robustness and accuracy [32]. Regardless of the algorithm chosen, the ultimate determinant of clinical success is a rigorous, multi-tiered validation strategy that includes independent and external cohorts, careful handling of data splits, and statistical testing to ensure the model is reliable, generalizable, and ready for translation into patient care [33] [34].

Multi-omics data integration represents a paradigm shift in cancer research, particularly in the realm of cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis for liquid biopsy applications. The simultaneous analysis of genomic, fragmentomic, and methylation data provides a multidimensional perspective on tumor biology that surpasses the capabilities of any single data type. Fragmentomics, the study of cfDNA fragmentation patterns, has emerged as a powerful approach that reflects nucleosome positioning and chromatin organization in tissue-of-origin cells [22]. When combined with methylation analysis and genomic alterations, these data layers enable sophisticated machine learning models to detect cancer, identify its tissue of origin, and monitor therapeutic response [7] [22].

The validation of such integrated models in clinical cohorts represents a critical step toward translation into routine practice. This guide objectively compares the performance of different integration strategies, wet-lab protocols, and computational methods based on recent experimental studies, providing researchers with a framework for selecting optimal approaches for their specific clinical research questions.

Comparative Performance of Multi-Omics Integration Methods

Statistical vs. Deep Learning Integration Approaches

Table 1: Performance comparison of multi-omics integration methods for cancer subtyping

| Integration Method | Cancer Type | Classification Accuracy | Key Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOFA+ (Statistical) [37] | Breast Cancer | F1-score: 0.75 (nonlinear classifier) | Superior feature selection; Identified 121 relevant pathways | Unsupervised; Requires downstream analysis |

| MOFA+ (Statistical) [38] | Glioblastoma | Successful subtype identification | Revealed AP-1, SMAD3, RUNX1/RUNX2 pathways | Bulk analysis may mask cellular heterogeneity |

| MOGCN (Deep Learning) [37] | Breast Cancer | Lower than MOFA+ | Handles complex nonlinear relationships | Identified only 100 pathways; Less interpretable |

| LASSO-MOGAT [39] | Pan-Cancer (31 types) | Accuracy: 95.9% | Effective with high-dimensional data | Complex implementation; Computationally intensive |

| Correlation-based Graph [39] | Pan-Cancer | Superior to PPI networks | Identifies shared cancer-specific signatures | May miss known biological interactions |

Fragmentomics Metrics Performance in Targeted Sequencing

Table 2: Performance of fragmentomics metrics in cancer detection using targeted panels

| Fragmentomic Metric | AUROC (UW Cohort) | AUROC (GRAIL Cohort) | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normalized depth (all exons) [7] | 0.943 | 0.964 | General purpose cancer detection |

| Normalized depth (E1 only) [7] | 0.930 | - | Promoter-associated changes |

| End Motif Diversity Score [7] | 0.888 (SCLC) | - | Small cell lung cancer specifically |

| TFBS entropy [7] | Variable | Variable | Transcription factor activity |

| ATAC entropy [7] | Variable | Variable | Open chromatin regions |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Data Generation

DNA Methylation Profiling Methodologies

Table 3: Comparison of DNA methylation detection methods

| Method | Resolution | DNA Input | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) [40] | Single-base | High | Gold standard; Comprehensive coverage | DNA degradation; High cost |

| Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing (EM-seq) [40] | Single-base | Lower than WGBS | Preserves DNA integrity; Better for GC-rich regions | Newer method; Less established |

| Illumina EPIC Array [40] | Pre-defined CpG sites | Low | Cost-effective; Standardized processing | Limited to pre-designed sites |

| Oxford Nanopore [40] | Single-base | High (~1μg) | Long reads; No conversion needed | Higher error rate; Custom analysis |

| FinaleMe (Computational) [41] | Inference from WGS | N/A | No bisulfite conversion; Uses existing WGS | Less accurate in CpG-poor regions |

Fragmentomics Analysis from Targeted Panels

Fragmentomics analysis typically begins with cfDNA extraction from plasma samples, followed by library preparation and sequencing using either whole-genome or targeted approaches. For targeted panels, the following steps are employed:

cfDNA Extraction and Quality Control: DNA is extracted using kits such as the DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit or specialized cfDNA extraction kits, with quantification via fluorometry and quality assessment using NanoDrop [40].

Library Preparation and Sequencing: Libraries are prepared according to panel-specific protocols, with hybridization-based capture for targeted panels. Sequencing depth varies by application - typically 3,000x for standard panels but exceeding 60,000x for ultra-sensitive applications [7].

Fragmentomic Feature Extraction: Multiple metrics are calculated from aligned BAM files:

- Fragment size distribution: Proportion of fragments in specific size bins (e.g., <150 bp) [7]

- Normalized depth: Read counts normalized by region length and sequencing depth [7]

- End motif analysis: Diversity of 4-mer sequences at fragment ends [7]

- Nucleosome positioning: Protection patterns indicating transcription factor binding [7]

Data Integration and Model Training: Features from multiple omics layers are integrated using methods like MOFA+ or deep learning approaches, with performance validation through cross-validation in independent cohorts [37] [7].

Multi-Omics Factor Analysis (MOFA+) Protocol

MOFA+ is a statistical framework for unsupervised integration of multiple omics datasets. The standard protocol includes:

Data Preprocessing: Each omics dataset is preprocessed independently. For RNA-seq, counts are transformed using variance stabilizing transformation (VST). DNA methylation data is log-transformed to approximate normality [38].

Feature Selection: To enhance model performance, the most variable features are selected - top 2% of variable CpG sites for methylation and top 50% of variable genes for expression data [38].

Model Training: The model is trained with multiple factors (typically 5-25), with the optimal number determined by the elbow method on the evidence lower bound. Models are run with slow convergence mode and appropriate likelihoods for each data type [38].

Downstream Analysis: Factors are interpreted based on their feature weights, with association to clinical variables and survival outcomes. Factors explaining >10% variance in at least one omic are typically retained for further analysis [38] [37].

Figure 1: MOFA+ Multi-Omics Integration Workflow. The statistical framework integrates diverse data types through factor analysis. [38] [37]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Key research reagents and platforms for multi-omics studies

| Category | Product/Platform | Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methylation Arrays | Illumina MethylationEPIC v2 [40] | Genome-wide methylation profiling | >935,000 CpG sites; Enhanced coverage of enhancer regions |

| Targeted Panels | Guardant360 CDx [7] | Clinical cfDNA analysis | 55 genes; FDA-approved for liquid biopsy |

| Targeted Panels | FoundationOne Liquid CDx [7] | Comprehensive cfDNA profiling | 309 genes; Broad genomic coverage |

| cfDNA Isolation | ApoStream [42] | Circulating tumor cell isolation | Preserves cellular morphology for downstream analysis |

| Spatial Analysis | ArchR [43] | Spatial multi-omics integration | Links chromatin accessibility with spatial context |

| Data Integration | Seurat v5 [43] | Multi-omics data integration | Bridge integration for unmatched datasets |

Fragmentomics-Based Methylation Inference

The FinaleMe algorithm represents a breakthrough in inferring DNA methylation states from standard whole-genome sequencing of cfDNA, bypassing the need for bisulfite conversion:

Model Architecture: FinaleMe employs a non-homogeneous Hidden Markov Model (HMM) that incorporates three key features: fragment length, normalized coverage, and the distance of each CpG to the center of the DNA fragment [41].

Training and Validation: The model is trained on matched WGS and WGBS data from the same blood samples, learning the relationship between fragmentation patterns and methylation status. Performance is validated by comparing predictions with actual methylation states from WGBS [41].

Performance Characteristics: The method achieves high accuracy in CpG-rich regions (auROC=0.91 for fragments with ≥5 CpGs) but is less accurate in CpG-poor regions. It successfully predicts tissue-of-origin fractions that correlate with tumor fractions estimated by copy number variation analysis [41].

Figure 2: FinaleMe Workflow for Methylation Inference. The computational method predicts methylation states from fragmentation patterns. [41]

Validation in Clinical Cohorts

Robust validation of multi-omics models requires careful study design and appropriate cohort selection:

Cohort Characteristics: Successful studies utilize well-characterized cohorts with appropriate sample sizes. The University of Wisconsin cohort (n=431) includes multiple cancer types with subtype information, while the GRAIL cohort (n=198) provides ultra-deep sequencing data [7].

Performance Metrics: Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) serves as the primary metric for classification performance, with additional evaluation using precision-recall curves and confusion matrices for subtype classification [37] [7].

Clinical Association: Validation includes association with clinical variables such as tumor stage, lymph node involvement, metastasis, and survival outcomes. Genes identified through multi-omics integration should show significant association with clinical phenotypes after false discovery rate correction [37].

Low Tumor Fraction Simulation: To assess real-world applicability, studies perform in silico dilution series to evaluate performance at low tumor fractions (0.1%-5%), mimicking minimal residual disease or early cancer detection scenarios [7].

The integration of genomics, fragmentomics, and methylation data represents a powerful approach for advancing liquid biopsy applications. Performance comparisons reveal that statistical integration methods like MOFA+ currently outperform deep learning approaches for feature selection in cancer subtyping, while fragmentomics metrics based on normalized depth provide the most robust classification across cancer types. The emergence of computational methods like FinaleMe that infer methylation from fragmentation patterns further expands the potential to extract maximal information from single assays. As these technologies mature, standardized validation in diverse clinical cohorts will be essential for translation into routine clinical practice, ultimately enabling more precise cancer detection, monitoring, and treatment selection.

The application of machine learning (ML) to cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis represents a transformative approach in clinical cancer research. cfDNA fragments circulating in blood plasma carry rich information, including genetic, epigenetic, and fragmentomic patterns that can reveal the presence of cancer, often at early stages [22] [44]. For researchers and drug development professionals, ensuring the validity and reliability of these ML models is paramount, as decisions based on their outputs may directly impact patient care and clinical trial outcomes.

The validation of cfDNA-based ML models extends beyond conventional performance metrics, requiring specialized strategies to address the unique challenges of clinical liquid biopsy applications. These challenges include typically low tumor DNA fractions in early-stage disease (often 1% or less), biological variability in cfDNA fragmentation patterns, and the critical need for model interpretability in clinical settings [45] [46]. This guide examines hyperparameter tuning strategies within this context, providing a structured comparison of methodologies to help researchers optimize model performance while maintaining scientific rigor and clinical relevance.

Hyperparameter Tuning Fundamentals in Machine Learning

Core Concepts and Terminology

Hyperparameters are configuration variables that govern the training process of machine learning models, set before the learning process begins. Unlike model parameters, which are learned from the data, hyperparameters control aspects such as model architecture, complexity, and learning rate [47]. In clinical cfDNA analysis, where datasets are often high-dimensional and complex, appropriate hyperparameter selection is crucial for building models that can detect subtle cancer signals amidst biological noise.

Hyperparameter optimization, or tuning, is the systematic process of finding the optimal combination of hyperparameter values that results in the best model performance [47] [48]. This process involves balancing bias (the ability to connect relationships between data points for accurate predictions) and variance (the ability to process new data) to create models that generalize well to unseen clinical samples [47].

The Hyperparameter Tuning Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for hyperparameter optimization in machine learning projects, particularly relevant to cfDNA analysis:

Comparative Analysis of Hyperparameter Tuning Methods

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Grid Search

Methodology: Grid Search is a brute-force approach that systematically works through every possible combination of hyperparameters from predefined sets [48] [49]. For each combination, it trains the model and evaluates performance using cross-validation. The algorithm exhaustively explores the search space, guaranteeing finding the optimal combination within the specified grid.

Experimental Protocol:

- Define a grid of hyperparameter values (e.g., for a random forest: nestimators = [50, 100, 150], maxdepth = [None, 10, 20])

- For each combination in the grid, train the model with k-fold cross-validation (typically 3-5 folds)

- Calculate the average performance metric across all folds for each combination

- Select the combination with the highest average performance [48]

Implementation Example (from cfDNA research):

This grid with 6 hyperparameters would require training 3×4×3×3×3×2 = 648 different models, each with k-fold cross-validation [49].

Random Search

Methodology: Random Search randomly samples hyperparameter combinations from specified distributions over a fixed number of iterations [48] [49]. Instead of exhaustive search, it explores the parameter space stochastically, which can be more efficient in high-dimensional spaces where only a few parameters significantly impact performance.

Experimental Protocol:

- Define distributions for each hyperparameter (e.g., n_estimators = randint(10, 200))

- Set the number of iterations (n_iter) based on computational budget

- For each iteration, randomly sample one value from each distribution

- Train and evaluate the model with cross-validation

- After all iterations, select the best-performing combination [48]

Implementation Example:

Bayesian Optimization

Methodology: Bayesian Optimization builds a probabilistic model (surrogate function) that maps hyperparameters to performance metrics, then uses this model to select the most promising hyperparameters to evaluate in the next iteration [47] [48]. It balances exploration (trying uncertain regions) and exploitation (focusing on known promising regions).

Experimental Protocol:

- Build a prior distribution over the objective function (performance metric)

- For several iterations:

- Select the next hyperparameter combination by optimizing an acquisition function

- Evaluate the objective function at the selected point

- Update the surrogate model with the new results

- Return the best-performing hyperparameter combination

Common surrogate models include Gaussian Processes, Random Forest Regression, and Tree-structured Parzen Estimators (TPE) [48].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Hyperparameter Tuning Methods

| Method | Computational Efficiency | Best For | Advantages | Limitations | cfDNA Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grid Search | Low - tests all combinations [49] | Small parameter spaces (≤4 parameters) [49] | Guaranteed optimal in grid; Simple implementation [48] | Exponential complexity; Wasted computation [48] | Limited utility; Suitable for final fine-tuning of 2-3 key parameters |

| Random Search | Medium - fixed number of samples [49] | Medium to large spaces; When some parameters unimportant [49] | More efficient for high dimensions; Better resource allocation [48] [49] | May miss optimum; No convergence guarantee [48] | Preferred for initial exploration of fragmentomic feature spaces |

| Bayesian Optimization | High - learns from previous trials [47] [48] | Complex spaces; Limited computational budget [48] | Requires fewer evaluations; Informed search strategy [47] [48] | Complex implementation; Overhead in model maintenance [48] | Ideal for clinical cfDNA models with constrained sample availability |

Table 2: Empirical Performance in Clinical cfDNA Studies

| Study Reference | Application | Tuning Method | Performance Metrics | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPOGIT Study [10] | GI cancer detection (multi-model) | Not specified (multiple algorithms) | 88.1% sensitivity, 91.2% specificity in multicenter validation (n=1,079) | Projected 92% reduction in late-stage diagnoses |

| DECIPHER-RCC [46] | Renal cell carcinoma detection | Stacked ensemble with automated tuning | AUC: 0.966 (validation), 0.952 (external) | High sensitivity for early-stage RCC with 92.9% specificity |

| Open Chromatin Guide [45] | Breast/pancreatic cancer detection | XGBoost with hyperparameter optimization | Improved accuracy using chromatin features | Identified key genomic loci associated with disease |

| Theoretical Comparison [49] | Breast cancer classification | Grid vs Random Search | Similar best scores (≈96.4%) with 60x fewer evaluations for random search | Significant computational savings without performance loss |

Domain-Specific Validation Strategies for cfDNA ML Models

Addressing Unique Challenges in cfDNA Analysis

Clinical cfDNA analysis presents distinctive challenges that necessitate specialized validation approaches beyond standard ML practices. These include low tumor fraction in early-stage disease (often 1-3% as reported in breast cancer studies [45]), biological variability in fragmentation patterns, and the multi-factorial nature of cfDNA signatures encompassing genetic, epigenetic, and fragmentomic features [22] [44].