From Code to Cure: Integrating DNA and RNA Sequencing in Modern Oncology

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the principles and clinical applications of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) in oncology, covering both DNA and RNA sequencing.

From Code to Cure: Integrating DNA and RNA Sequencing in Modern Oncology

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the principles and clinical applications of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) in oncology, covering both DNA and RNA sequencing. It explores the foundational technology, detailing how NGS has surpassed traditional methods like Sanger sequencing. The piece delves into methodological workflows, from nucleic acid isolation to data analysis, and highlights advanced applications such as identifying expressed mutations, gene fusions, and tumor microenvironment signatures. It further addresses critical challenges in validation, troubleshooting, and optimization for clinical use. Finally, the article examines the transformative impact of integrated DNA and RNA sequencing on precision medicine, including its role in guiding tumor-agnostic therapies and improving patient outcomes through more accurate biomarker discovery and therapeutic targeting.

The Genomic Revolution: Core Principles of Next-Generation Sequencing in Cancer

The field of genomics has undergone a revolutionary transformation with the advent of Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS), moving from linear, single-fragment analysis to massively parallel processing. This technological evolution is particularly critical in oncology research, where comprehensive genomic profiling of tumors has become fundamental to understanding cancer biology and developing targeted therapies. The shift from Sanger sequencing, known as the first-generation method, to NGS represents more than just an incremental improvement—it constitutes a complete reimagining of sequencing scalability, efficiency, and application [1]. Where the Human Genome Project required 13 years and nearly $3 billion using Sanger technology, NGS can now sequence an entire human genome in approximately one week at a fraction of the cost [2] [3]. This dramatic enhancement in throughput has positioned NGS as an indispensable tool in modern oncology research, enabling scientists to decipher the complex genetic alterations that drive cancer progression, metastasis, and treatment resistance.

The fundamental distinction between these technologies lies in their core architecture: Sanger sequencing processes a single DNA fragment at a time, while NGS simultaneously sequences millions of fragments in parallel [4]. This massively parallel approach has unlocked unprecedented capabilities for comprehensive genomic analysis, from whole-genome sequencing to targeted panels of cancer-associated genes. In oncology, where tumors often harbor heterogeneous cell populations with diverse mutations, the ability to detect low-frequency variants and structural alterations across hundreds of genes in a single assay has transformed research methodologies and therapeutic development [2] [5]. This technical guide explores the throughput advantage of NGS through quantitative comparisons, experimental applications in oncology research, and detailed methodologies that highlight its transformative role in cancer genomics.

Fundamental Technological Differences: Sanger vs. NGS

Core Principles and Sequencing Chemistry

The fundamental difference between Sanger sequencing and NGS lies not in the basic biochemistry of DNA synthesis but in the scale and parallelization of the sequencing process. Both methods rely on DNA polymerase to incorporate nucleotides into a growing DNA strand complementary to the template being sequenced [4]. However, their implementation diverges significantly in how they manage this process and detect the incorporated nucleotides.

Sanger sequencing (chain-termination method) utilizes dideoxynucleoside triphosphates (ddNTPs), which lack the 3'-hydroxyl group necessary for forming a phosphodiester bond with the next nucleotide. When incorporated, these chain-terminating nucleotides halt DNA synthesis, producing DNA fragments of varying lengths [6]. In modern capillary electrophoresis implementations, each ddNTP is labeled with a distinct fluorescent dye, allowing separation by size and detection via laser excitation [6]. This process generates a single, long contiguous read (typically 500-1000 base pairs) per reaction, making it highly accurate for targeted sequencing but fundamentally limited in throughput [2] [6].

In contrast, NGS technologies employ massively parallel sequencing of millions to billions of DNA fragments simultaneously [4]. The most common approach, Sequencing by Synthesis (SBS), used by Illumina platforms, incorporates fluorescently-labeled reversible terminators that temporarily halt synthesis after each nucleotide incorporation [3]. After imaging to determine the incorporated base, the terminator is cleaved, and the process repeats [3]. This cyclical process occurs simultaneously across millions of DNA clusters on a flow cell, generating enormous volumes of data in a single run [2] [3]. Other NGS chemistries include ion semiconductor sequencing (detecting pH changes during nucleotide incorporation) and single-molecule real-time sequencing (observing incorporation in real-time) [2] [3].

Workflow Comparison: From Sample to Sequence

The experimental workflow from sample preparation to data output differs substantially between Sanger and NGS methods, with implications for throughput, scalability, and applications in oncology research.

Table 1: Comparative Workflows in Sanger Sequencing and NGS

| Workflow Step | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | PCR amplification of specific target regions | Fragmentation of DNA, adapter ligation, and library preparation |

| Template Amplification | Clonal amplification in bacterial vectors (historical) or PCR | Bridge amplification or emulsion PCR to create clustered DNA fragments |

| Sequencing Process | Capillary electrophoresis with fluorescent detection | Massively parallel sequencing by synthesis, ion semiconductor, or other methods |

| Data Output | Single sequence per run (up to 1,000 bp) | Millions to billions of short reads (50-600 bp) per run |

| Read Analysis | Direct sequence reading from electrophoretogram | Alignment to reference genome and variant calling through bioinformatics pipelines |

The library preparation step in NGS is particularly critical for oncology applications. DNA is fragmented into manageable pieces, and adapter sequences are attached to both ends. These adapters serve dual purposes: they enable binding to the sequencing platform and facilitate the amplification that creates clusters of identical DNA fragments [3]. For tumor samples, which often yield limited quantities of degraded DNA (especially from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens), specialized library preparation protocols have been developed to maximize data quality from suboptimal starting material [5].

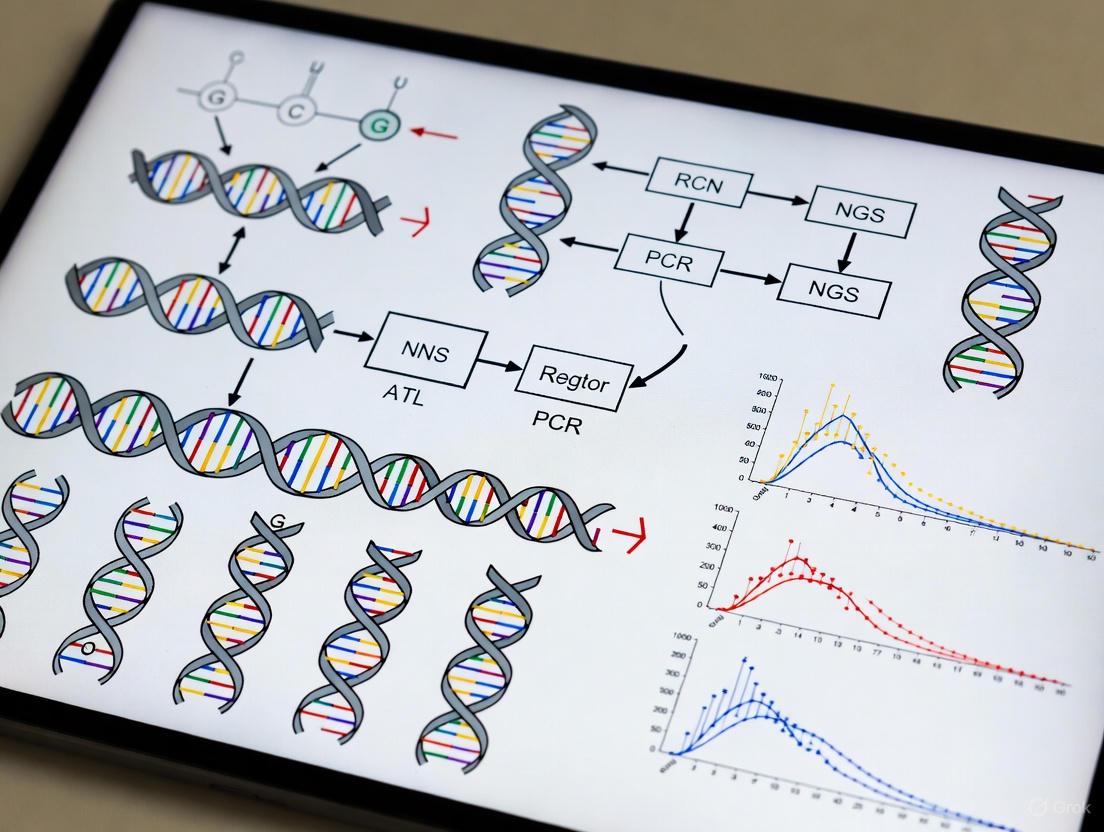

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in NGS library preparation and sequencing:

NGS Library Preparation and Sequencing Workflow

Quantitative Comparison: Throughput and Performance Metrics

Throughput, Sensitivity, and Cost Analysis

The throughput advantage of NGS becomes evident when examining quantitative performance metrics across multiple parameters critical to oncology research. The massively parallel nature of NGS enables a fundamental shift in sequencing capacity that transcends simple speed comparisons.

Table 2: Performance Comparison Between Sanger Sequencing and NGS

| Parameter | Sanger Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Single DNA fragment per reaction | Millions to billions of fragments simultaneously [4] |

| Sensitivity (Detection Limit) | 15-20% variant allele frequency [2] [4] | As low as 1-5% variant allele frequency [2] [7] |

| Human Genome Sequencing Time | Approximately 13 years (Human Genome Project) [3] | Approximately one week [2] |

| Cost per Human Genome | ~$3 billion (Human Genome Project) [3] | Under $1,000 [3] |

| Read Length | 500-1000 base pairs [2] [6] | 50-600 base pairs (short-read platforms) [3] |

| Applications in Oncology | Single-gene mutation confirmation | Multi-gene panels, whole exome/genome, transcriptomics, epigenomics [2] [8] |

| Variant Detection Capability | Limited to specific targeted regions | SNPs, indels, CNVs, structural variants, fusion genes [2] |

The sensitivity advantage of NGS is particularly significant in oncology applications. The ability to detect variants with ~1% variant allele frequency (VAF) compared to Sanger's 15-20% VAF enables identification of low-frequency mutations in heterogeneous tumor samples and early detection of emerging resistant clones [2] [4] [7]. This enhanced sensitivity stems from the deep sequencing capability of NGS, where each genomic region is covered hundreds to thousands of times, allowing statistical discrimination of true low-frequency variants from sequencing errors [2].

Economic and Operational Efficiency

The economic advantage of NGS emerges primarily through its massive parallelization and multiplexing capabilities. While the per-run cost of NGS is higher than Sanger sequencing, the cost per base is dramatically lower—making comprehensive genomic profiling economically feasible [6]. This economic model has enabled scaling of oncology research that would be prohibitively expensive with Sanger sequencing.

The multiplexing capability of NGS allows barcoding of hundreds of samples that can be pooled and sequenced simultaneously, further optimizing reagent use and operational efficiency [4]. For oncology drug development, where screening numerous cell lines, patient-derived xenografts, or clinical samples is routine, this multiplexing advantage significantly accelerates research timelines. The combination of higher throughput, greater sensitivity, and lower cost per base makes NGS particularly suited for the complex genomic landscape of cancer, which often requires interrogating hundreds of genes simultaneously to capture the full spectrum of clinically relevant mutations [5].

NGS Applications in Oncology Research

Comprehensive Genomic Profiling in Cancer Research

In oncology research, NGS has become the cornerstone technology for comprehensive genomic profiling of tumors, enabling a multifaceted approach to understanding cancer biology. The throughput advantage of NGS allows simultaneous assessment of multiple genomic alteration types across hundreds of cancer-associated genes, providing researchers with a complete molecular portrait of malignancy [2] [7]. This comprehensive approach has accelerated the discovery of driver mutations, fusion genes, and predictive biomarkers across diverse cancer types [2].

Targeted NGS panels specifically designed for oncology research typically focus on genes with established roles in carcinogenesis, such as KRAS, EGFR, TP53, PIK3CA, and BRCA1/2 [5]. These panels offer the advantage of deep sequencing coverage (often >500x) at lower cost compared to whole-genome approaches, making them ideal for detecting low-frequency variants in heterogeneous tumor samples [5]. The TTSH-oncopanel, a 61-gene panel described in recent research, demonstrates how targeted NGS can achieve 98.23% sensitivity for mutation detection while reducing turnaround time to just 4 days [5]. This efficiency in generating comprehensive genomic data accelerates therapeutic discovery and validation workflows.

Specialized Research Applications

The throughput advantage of NGS enables several specialized applications that are transforming oncology research:

Liquid Biopsy and Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) Analysis: NGS provides the sensitivity required to detect and sequence rare ctDNA fragments in blood samples, enabling non-invasive tumor genotyping and monitoring of treatment response [2] [7]. Research applications include tracking clonal evolution, detecting minimal residual disease, and identifying emerging resistance mechanisms during targeted therapy [7].

Transcriptomic Profiling (RNA-Seq): NGS-based RNA sequencing allows comprehensive analysis of gene expression, alternative splicing, and fusion transcripts in tumor samples [9]. Recent studies demonstrate how targeted RNA-seq can complement DNA-based mutation detection by confirming expression of identified variants and detecting additional clinically relevant fusions missed by DNA sequencing alone [9].

Immuno-oncology Biomarker Discovery: The throughput of NGS enables quantification of complex biomarkers such as tumor mutational burden (TMB), microsatellite instability (MSI), and immune repertoire profiling—all critical for immunotherapy development [2] [7]. These applications require genome-wide sequencing data that would be impractical with Sanger sequencing.

Single-Cell Sequencing: Emerging NGS applications in oncology research include single-cell RNA and DNA sequencing, which reveals tumor heterogeneity and microenvironment interactions at unprecedented resolution [2]. This application exemplifies how NGS throughput enables entirely new research paradigms in cancer biology.

Experimental Design and Methodology

Implementing Targeted NGS Panels in Oncology Research

The experimental workflow for implementing targeted NGS in oncology research requires careful consideration of multiple parameters to ensure robust, reproducible results. Based on recent research validating the TTSH-oncopanel, the following methodology provides a framework for targeted NGS in cancer genomics [5]:

Sample Preparation and Quality Control:

- Input Requirement: ≥50 ng of DNA from tumor samples

- Quality Metrics: DNA integrity number (DIN) ≥4.0 for formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples

- Extraction Method: Standard column-based or magnetic bead-based protocols

- Quality Assessment: Fluorometric quantification and fragment analysis

Library Preparation Protocol:

- DNA Fragmentation: Fragment genomic DNA to ~300 bp using acoustic shearing or enzymatic fragmentation

- Adapter Ligation: Attach platform-specific adapter sequences with sample barcodes using ligase-mediated approach

- Library Amplification: Amplify ligated fragments using 6-8 cycles of PCR with high-fidelity polymerase

- Library Quantification: Assess library concentration using fluorometric methods and validate fragment size distribution

Target Enrichment:

- Method: Hybridization capture with biotinylated oligonucleotide probes

- Panel Design: Custom probes targeting 61 cancer-associated genes (or research-specific gene set)

- Hybridization: Incubate library with probe pool for 16-24 hours at 65°C

- Wash Conditions: Stringent washing to remove non-specifically bound fragments

Sequencing Parameters:

- Platform: Illumina, MGI DNBSEQ-G50RS, or comparable system

- Read Configuration: Paired-end sequencing (2×150 bp)

- Coverage Target: Minimum 250x mean coverage with >98% of targets at ≥100x

- Sample Multiplexing: 24-96 samples per flow cell lane depending on desired coverage

Bioinformatics Analysis Pipeline

The massive data output from NGS requires sophisticated bioinformatics analysis, which represents both a challenge and opportunity in oncology research:

Primary Analysis:

- Base Calling: Convert raw signal data to nucleotide sequences

- Demultiplexing: Assign reads to specific samples based on barcode sequences

- Quality Control: FastQC evaluation of read quality, adapter content, and duplication rates

Secondary Analysis:

- Read Alignment: Map sequences to reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using BWA-MEM or similar aligner

- Variant Calling: Identify single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small indels using Mutect2, VarDict, or LoFreq [9]

- Annotation: Annotate variants with population frequency, functional impact, and clinical significance databases

Tertiary Analysis:

- Pathway Analysis: Identify significantly mutated pathways and biological processes

- Variant Prioritization: Filter variants based on frequency, predicted impact, and relevance to cancer phenotype

- Data Visualization: Create intuitive visualizations of mutation spectra and genomic landscapes

The following diagram illustrates the bioinformatics workflow for processing NGS data in oncology research:

Bioinformatics Workflow for NGS Data in Oncology

Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of NGS in oncology research requires specific reagents, platforms, and computational tools. The following table details essential components of the NGS research toolkit:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for NGS in Oncology

| Category | Specific Products/Platforms | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation | Illumina DNA Prep, KAPA HyperPlus, MGI EasySeq | Fragment DNA and add platform-specific adapters for sequencing |

| Target Enrichment | Sophia Genetics Oncopanel, Agilent ClearSeq, Roche Comprehensive Cancer Panel | Hybridization capture to enrich for cancer-related genes |

| Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, MGI DNBSEQ-G50, PacBio Sequel, Oxford Nanopore | Generate sequencing data with different read lengths and applications |

| Automation Systems | MGI SP-100RS, Hamilton NGS STAR | Automated library preparation to reduce hands-on time and variability |

| Bioinformatics Tools | BWA, GATK, Mutect2, VarDict, Sophia DDM | Align sequences, call variants, and annotate results [5] [9] |

| Reference Materials | Horizon Discovery HD701, Seraseq FFPE | Positive controls for assay validation and quality monitoring [5] |

Each component plays a critical role in the end-to-end NGS workflow. For example, automated library preparation systems like the MGI SP-100RS can improve reproducibility while reducing human error and contamination risk [5]. Bioinformatics platforms such as Sophia DDM incorporate machine learning algorithms for variant analysis and visualization, connecting molecular profiles to biological insights through specialized knowledge bases [5].

The transition from Sanger sequencing to Next-Generation Sequencing represents a fundamental shift in the scale and scope of genomic analysis possible in oncology research. The throughput advantage of NGS—enabled by massively parallel processing—has transformed cancer genomics from a gene-by-gene approach to comprehensive genomic profiling that captures the full complexity of malignant transformation. This technical evolution has accelerated therapeutic discovery, enabled personalized treatment approaches, and deepened our understanding of cancer biology.

Future developments in NGS technology continue to build upon this throughput foundation. Third-generation sequencing platforms offering long-read capabilities are addressing NGS limitations in resolving complex genomic regions [2] [3]. Single-cell sequencing methods are revealing tumor heterogeneity at unprecedented resolution [2]. Spatial transcriptomics technologies are adding morphological context to gene expression data [2]. The integration of artificial intelligence with NGS data is enhancing variant interpretation and biomarker discovery [2]. Each of these advancements extends the throughput advantage of NGS into new dimensions of genomic analysis, ensuring its continued central role in oncology research and drug development.

As NGS technologies continue to evolve, further reductions in cost and improvements in automation will make comprehensive genomic profiling increasingly accessible. However, the core principle remains: the massively parallel architecture of NGS provides a throughput advantage that has permanently transformed oncology research, enabling scientists to interrogate cancer genomes with a breadth and depth that was unimaginable with Sanger sequencing technology.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized oncology research by enabling comprehensive genomic profiling of tumors, facilitating the shift toward precision medicine [8] [10]. This transformative technology allows researchers to identify genetic alterations that drive cancer progression, detect hereditary cancer syndromes, and monitor treatment response through sensitive minimal residual disease detection [8]. Unlike traditional Sanger sequencing, which processes one DNA fragment at a time, NGS employs massively parallel sequencing to simultaneously analyze millions of fragments, significantly reducing time and cost while providing unprecedented genomic resolution [8] [10]. The core NGS workflow consists of four critical stages: sample preparation, library construction, sequencing, and data analysis, each requiring meticulous execution to generate reliable results for clinical decision-making in oncology [11] [8]. This technical guide details each step of the core NGS workflow within the context of modern cancer genomics research.

Sample Preparation

Sample preparation is the foundational step in the NGS workflow, transforming nucleic acids from biological samples into sequence-ready libraries. Proper execution is crucial, as any deficiencies at this stage can compromise sequencing success and downstream analysis [11].

Nucleic Acid Extraction

The initial step involves isolating DNA or RNA from various biological samples, including tumor tissues, blood, cultured cells, or urine [11]. In oncology, samples often present challenges such as formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue, which may yield degraded nucleic acids, or fine-needle biopsies with limited starting material [11] [12]. The quality of extracted nucleic acids directly depends on sample quality and appropriate storage conditions, with fresh material recommended but often supplemented with properly preserved specimens [11].

Essential protocols for nucleic acid extraction:

- DNA Extraction from FFPE Tissue: Using a QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue kit (Qiagen), extract genomic DNA after manual microdissection of representative tumor areas with sufficient tumor cellularity. Quantify DNA concentration using Qubit dsDNA HS Assay kit on Qubit 3.0 Fluorometer and assess purity with NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (A260/A280 ratio 1.7-2.2) [12].

- Cell Disruption: Employ mechanical, enzymatic, or chemical methods to lyse cells and release nucleic acids while maintaining integrity.

- Purification: Remove contaminants including proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates through organic extraction or column-based methods.

- Quality Assessment: Evaluate nucleic acid quantity and quality using fluorometric methods (Qubit, PicoGreen) for precision and spectrophotometry (Nanodrop) for purity assessment (DNA: 260/280 ratio 1.8-2.0; RNA: 260/280 ratio 1.8-2.1) [11] [13].

For challenging oncology samples with limited material, amplification through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may be necessary, though this introduces potential biases that must be minimized through specialized PCR enzymes and library complexity optimization [11].

Special Considerations for Oncology Samples

Oncology research frequently deals with heterogeneous tumor samples with varying tumor purity, requiring special considerations during sample preparation:

- Tumor Enrichment: Manual microdissection of FFPE blocks to select areas with sufficient tumor cellularity (>20% typically recommended) [12].

- Input Requirements: Minimum of 20 ng DNA for library generation, though higher amounts improve library complexity [12].

- Quality Thresholds: Samples with A260/A280 ratios outside 1.7-2.2 may indicate contamination and should be avoided [12].

- Liquid Biopsy Applications: Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) from blood samples requires high sensitivity to detect variants at low allele frequencies (as low as 0.5%) [14].

Library Construction

Library construction converts purified nucleic acids into formats compatible with NGS platforms through fragmentation and adapter ligation [11] [8]. This critical step determines the success of subsequent sequencing and analysis.

DNA Library Preparation

DNA library preparation involves several standardized steps to process genomic DNA for sequencing:

- Fragmentation: DNA is fragmented to desired lengths (typically 300 bp) using physical (acoustic shearing), enzymatic (transposase-based), or chemical methods. Physical methods provide more uniform fragment sizes, while enzymatic approaches offer convenience and rapid processing [11] [8].

- End Repair and A-Tailing: DNA fragment ends are repaired to create blunt ends, followed by addition of single adenosine nucleotides to facilitate adapter ligation. Efficient A-tailing prevents chimera formation during amplification [11] [13].

- Adapter Ligation: Platform-specific adapters containing sequencing primer binding sites are ligated to fragment ends. These adapters may include barcodes (indices) to enable sample multiplexing [11] [8].

- Size Selection: Libraries are size-selected to remove fragments too large or small for optimal sequencing, performed using magnetic bead-based clean-up or agarose gel electrophoresis [11].

- Amplification: PCR amplification enriches for adapter-ligated fragments, though PCR-free protocols are available to minimize amplification biases, particularly important for detecting low-frequency variants in cancer [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Nucleic Acid Fragmentation Methods

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical (Sonication) | Acoustic energy shears DNA | Uniform fragment size, minimal bias | Equipment cost, sample volume requirements | Whole genome sequencing, PCR-free libraries |

| Enzymatic (Tagmentation) | Transposase simultaneously fragments and tags DNA | Rapid, cost-effective, minimal hands-on time | Sequence bias potential, optimization required | High-throughput applications, targeted sequencing |

| Chemical | divalent cations fragment DNA | Simple, inexpensive | Less control over size distribution | Basic research applications |

RNA Library Preparation

RNA sequencing library construction requires additional steps to convert RNA to sequencing-compatible DNA:

- RNA Selection: Isolate mRNA using poly-A selection or deplete ribosomal RNA to enrich for protein-coding transcripts.

- cDNA Synthesis: Reverse transcribe RNA to complementary DNA (cDNA) using reverse transcriptase, as DNA is more stable and amplifiable using DNA polymerase [11] [8].

- Library Construction: Process cDNA similarly to DNA libraries through fragmentation, end repair, adapter ligation, and amplification. Strand-specific protocols preserve transcript orientation information [11] [13].

Quality Control in Library Construction

Rigorous quality control ensures library integrity before sequencing:

- Quantification: Use qPCR or fluorometric methods for accurate library quantification, as spectrophotometry may overestimate concentration [13].

- Size Distribution: Analyze fragment size distribution using Bioanalyzer or TapeStation systems, with ideal library sizes of 250-400 bp for Illumina platforms [12].

- Adapter Dimer Check: Verify absence of primer dimers which compete with library fragments during sequencing.

- Molarity Calculation: Precisely calculate library molarity for accurate clustering during sequencing.

For oncology applications, libraries must meet stringent quality thresholds, with at least 80% of targets achieving 100x coverage, and average mean depths of 500-1000x recommended for detecting low-frequency variants in heterogeneous tumor samples [12].

Sequencing

The sequencing phase involves massive parallel sequencing of prepared libraries using NGS platforms, generating vast amounts of raw data for downstream analysis [8].

Sequencing Technologies and Platforms

Multiple NGS platforms employ different sequencing chemistries and detection methods:

- Illumina Sequencing: Utilizes sequencing-by-synthesis with fluorescently labeled nucleotides. Library fragments are immobilized on a flow cell and amplified via bridge PCR to form clusters. During each cycle, fluorescently tagged nucleotides incorporate into growing DNA strands, with imaging detecting the incorporated base at each cluster [8].

- Ion Torrent Sequencing: Employs semiconductor technology detecting hydrogen ions released during DNA polymerization rather than optical signals, enabling faster run times.

- Pacific Biosciences SMRT Sequencing: Uses single molecule real-time sequencing with zero-mode waveguides to observe polymerase activity in real time, generating long reads beneficial for resolving complex genomic regions.

- Oxford Nanopore Sequencing: Measures changes in electrical current as DNA strands pass through protein nanopores, enabling ultra-long reads and real-time analysis.

Table 2: Comparison of Major NGS Sequencing Platforms

| Platform | Technology | Read Length | Throughput | Error Rate | Primary Oncology Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq | Sequencing-by-synthesis | 50-300 bp | 0.8-6.0 Tb | 0.1-0.6% | Whole genome, exome, transcriptome, targeted sequencing |

| Illumina NextSeq 550Dx | Sequencing-by-synthesis | 75-300 bp | 120-360 Gb | 0.1-0.6% | Targeted panels, clinical diagnostics [12] |

| Ion Torrent Genexus | Semiconductor sequencing | 200-400 bp | 40-500 Mb | ~1% | Rapid targeted sequencing, liquid biopsy |

| PacBio Revio | SMRT sequencing | 10-50 kb | 0.9-1.8 Tb | ~5% (random) | Structural variant detection, fusion genes, haplotype phasing |

| Oxford Nanopore PromethION | Nanopore sequencing | 10 kb-2 Mb+ | 2.5-14 Tb | 2-10% | Structural variants, epigenetics, isoform sequencing |

Sequencing Applications in Oncology

NGS enables various sequencing approaches tailored to specific oncology research questions:

- Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS): Determines the complete DNA sequence of the entire tumor genome, identifying coding and non-coding variants, structural rearrangements, and copy number alterations [11].

- Whole Exome Sequencing (WES): Targets protein-coding regions (exons), comprising ~1-2% of the genome, cost-effectively identifying coding variants responsible for cancer driver mutations [11] [8].

- Targeted Sequencing: Focuses on specific genes or genomic regions of clinical significance in cancer, using hybridization capture or amplicon-based approaches to achieve deep coverage for detecting low-frequency variants [11] [7].

- RNA Sequencing: Profiles the transcriptome to identify gene expression changes, fusion genes, alternative splicing, and mutation effects on transcription [11].

- Methylation Sequencing: Uses bisulfite treatment to detect DNA methylation patterns, revealing epigenetic modifications in cancer development [11].

Each application requires specialized library preparation methods, with targeted approaches particularly valuable in clinical oncology for focusing on established cancer-associated genes with high sensitivity [11] [7].

Data Analysis

NGS data analysis converts raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful information through complex computational workflows, representing a critical bottleneck in oncology genomics [8] [15].

Primary Data Analysis

The initial analysis phase processes raw instrument data into sequence reads:

- Base Calling: Converts raw signal data (fluorescence or ion potential) into nucleotide sequences, assigning quality scores (Phred scores) to each base.

- Demultiplexing: Separates pooled samples using barcode sequences added during library preparation, generating individual sequence files for each sample.

- Quality Assessment: Evaluates read quality using tools like FastQC to identify potential issues with sequencing runs, adapter contamination, or poor-quality regions.

Sequence Alignment and Processing

Processed reads are aligned to reference genomes to identify genomic variants:

- Read Alignment/Mapping: Maps sequence reads to reference genomes (e.g., GRCh38) using aligners like BWA, Bowtie2, or Novoalign, identifying genomic positions for each read [15].

- Post-Alignment Processing: Refines alignments through duplicate marking, base quality score recalibration, and local realignment around indels to improve variant detection accuracy.

- Variant Calling: Identifies genomic variants (single nucleotide variants, insertions/deletions, copy number variations, structural variants) using specialized algorithms:

Table 3: Bioinformatics Tools for NGS Data Analysis in Oncology

| Analysis Step | Common Tools | Key Features | Oncology Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Alignment | BWA, Bowtie2, Novoalign | Efficient mapping to reference genomes | Optimal for detecting somatic variants with high specificity [15] |

| SNV/Indel Calling | Mutect2, VarScan, Strelka2 | High sensitivity for low-frequency variants | Detection limit typically 2-5% VAF; lower for ultrasensitive applications [15] [12] |

| Copy Number Analysis | ASCATNGS, CNVkit | Resolves tumor purity and ploidy | Essential for identifying oncogene amplifications and tumor suppressor deletions [16] [12] |

| Structural Variant Calling | LUMPY, Delly | Detects rearrangements, fusions | Critical for identifying targetable fusions (e.g., RET, ALK, ROS1) [12] |

| Annotation | SnpEff, VEP | Functional consequence prediction | Annotates variants with clinical databases (ClinVar, COSMIC) [12] |

Variant Interpretation and Clinical Reporting

In oncology research, identified variants require careful interpretation to determine clinical significance:

- Variant Annotation: Annotates variants using tools like SnpEff or Variant Effect Predictor with functional predictions (SIFT, PolyPhen, CADD), population frequencies, and clinical databases (ClinVar, COSMIC) [17] [12].

- Tier Classification: Classifies variants according to standardized guidelines (e.g., Association for Molecular Pathology):

- Tier I: Variants of strong clinical significance (FDA-approved or professional guidelines)

- Tier II: Variants of potential clinical significance (different tumor types or investigational therapies)

- Tier III: Variants of unknown clinical significance

- Tier IV: Benign or likely benign variants [12]

- Actionability Assessment: Determines therapeutic implications based on evidence levels, including FDA-approved therapies, clinical trials, and preclinical evidence.

- Report Generation: Creates comprehensive reports documenting methodology, variants identified, clinical interpretations, and therapeutic recommendations.

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for NGS in Oncology

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Notes | Representative Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | Isolate DNA/RNA from various sample types | Critical for FFPE samples; ensure high purity with 260/280 ratio 1.7-2.2 | QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit [12] |

| DNA Quantitation Assays | Precisely measure DNA concentration | Fluorometric methods preferred over spectrophotometry for accuracy | Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit [12] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Convert nucleic acids to sequenceable libraries | Select based on application (WGS, WES, targeted, RNA-seq) | Illumina DNA Prep, Agilent SureSelectXT [12] |

| Target Enrichment Systems | Enrich specific genomic regions | Hybridization capture provides uniform coverage; amplicon-based offers simplicity | Agilent SureSelect (hybridization capture) [12] |

| Quality Control Instruments | Assess library quality and quantity | Essential for determining fragment size distribution and molarity | Agilent Bioanalyzer, TapeStation [12] |

| Sequencing Chemistries | Enable base detection during sequencing | Platform-specific reagents for cluster generation and sequencing | Illumina sequencing reagents, Ion Torrent supplies |

| Variant Calling Software | Identify genomic alterations from sequence data | Multiple algorithms recommended for comprehensive variant detection | GATK Mutect2, VarScan, Strelka2 [15] [12] |

| Bioinformatics Pipelines | Integrated analysis workflows | Combine mapping, variant calling, and annotation in reproducible workflows | GATK Best Practices, custom pipeline scripts [15] [17] |

The core NGS workflow represents a transformative technology in oncology research, enabling comprehensive molecular profiling that drives precision medicine approaches. From sample preparation through data analysis, each step requires meticulous execution and quality control to generate clinically actionable results. The integration of robust laboratory protocols with sophisticated bioinformatics pipelines allows researchers to detect diverse genomic alterations in cancer, including single nucleotide variants, insertions/deletions, copy number variations, and structural rearrangements. As NGS technologies continue to evolve with advancements in single-cell sequencing, liquid biopsies, and long-read sequencing, the workflow will further refine our understanding of tumor heterogeneity and treatment resistance mechanisms. Standardization of procedures, validation of bioinformatics pipelines, and interdisciplinary collaboration remain essential for maximizing the potential of NGS in advancing oncology research and improving patient outcomes through molecularly-guided therapies.

In the field of modern oncology research, next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized our approach to understanding and treating cancer. DNA sequencing (DNA-seq) and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) stand as two foundational technologies that provide complementary views of the molecular machinery driving carcinogenesis. While DNA-seq reveals the hereditary blueprint and acquired mutations within the tumor genome, RNA-seq illuminates the functional transcriptome activity, revealing which genetic instructions are actively being executed [8] [18]. The integration of both data types creates a more complete picture of cancer biology, enabling researchers and clinicians to move beyond static genetic maps to dynamic functional understanding. This technical guide explores the principles, methodologies, and synergistic applications of DNA and RNA sequencing within oncology research, providing scientists and drug development professionals with a framework for leveraging these technologies to advance precision medicine.

Fundamental Principles and Technological Comparisons

Core Objectives and Molecular Targets

DNA and RNA sequencing are designed to answer fundamentally different biological questions. DNA-seq aims to determine the precise order of nucleotides (A, T, C, G) within DNA molecules, thereby characterizing the genetic blueprint of an organism or tumor. This includes identifying genetic variations such as single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions and deletions (indels), copy number variations (CNVs), and structural rearrangements [18]. In oncology, this enables the discovery of inherited cancer predispositions, somatic driver mutations, and tumor-specific genetic alterations that may serve as therapeutic targets.

In contrast, RNA-seq analyzes the transcriptome—the complete set of RNA transcripts produced by the genome at a specific point in time. This technology captures dynamic gene expression patterns, revealing which genes are actively transcribed into RNA, and at what levels [18]. Beyond quantifying expression, RNA-seq provides critical insights into alternative splicing events, gene fusions, post-transcriptional modifications, and non-coding RNA species. This functional dimension is particularly valuable in cancer research for understanding how genetic alterations manifest as transcriptional changes that drive tumor behavior and therapeutic responses.

Technical Workflows and Methodological Considerations

The fundamental workflow differences between DNA and RNA sequencing begin at the sample preparation stage. For DNA-seq, extracted genomic DNA is fragmented, and adapters are ligated to create a sequencing library [8]. For RNA-seq, the process is more complex due to RNA's inherent instability; extracted RNA must first be reverse-transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) before library construction, requiring careful handling to prevent degradation [18]. Most sequencing platforms (e.g., Illumina, Ion Torrent, PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) can be used for both DNA and RNA sequencing, though platform selection depends on the specific research goals, required read length, and desired throughput [18] [19].

Table 1: Key Technical Differences Between DNA and RNA Sequencing

| Feature | DNA Sequencing | RNA Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Target | Genomic DNA | RNA transcripts (converted to cDNA) |

| Primary Information | Genetic sequence, mutations, structural variants | Gene expression levels, splice variants, fusion transcripts |

| Sample Stability | Relatively stable, degrades slowly | Labile, degrades rapidly, requires careful preservation |

| Library Preparation | DNA fragmentation, adapter ligation | RNA extraction, reverse transcription to cDNA, fragmentation |

| Key Applications in Oncology | Identifying somatic mutations, CNVs, SNVs, hereditary risk | Detecting gene fusions, expression profiling, alternative splicing |

| Common Analysis Tools | BWA, Bowtie, GATK, Samtools | STAR, HISAT2, DESeq2, EdgeR |

Detection Capabilities for Oncogenic Alterations

The complementary strengths of DNA and RNA sequencing become particularly evident when assessing their capabilities to detect different classes of oncogenic alterations. DNA-seq excels at identifying single nucleotide variants, small insertions/deletions, and copy number alterations across the entire genome or targeted regions [8] [18]. However, it has significant limitations in detecting gene fusions, as the breakpoints often occur within long intronic regions containing repetitive sequences that are difficult to sequence and map [18].

RNA-seq proves superior for fusion detection because it sequences the transcribed mRNA, effectively skipping over intronic regions and providing direct evidence of expressed fusion events [18]. This capability has profound clinical implications, as numerous targeted therapies are now approved for cancers harboring fusions in genes such as ALK, ROS1, RET, and NTRK [20]. A study of 1,211 non-small cell lung cancer specimens found that approximately 10% of cases required reflex RNA sequencing to identify clinically actionable fusions that were missed by initial amplicon-based DNA testing [20].

Table 2: Detection Capabilities for Key Cancer Genomic Alterations

| Alteration Type | DNA-Seq Performance | RNA-Seq Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) | Excellent (Gold Standard) | Good, but limited to expressed mutations [21] |

| Insertions/Deletions (Indels) | Excellent | Good for expressed indels [18] |

| Copy Number Variations (CNVs) | Excellent | Limited to inferring from expression levels |

| Gene Fusions | Limited due to intronic breakpoints [18] | Excellent, detects expressed fusion transcripts [18] [20] |

| Alternative Splicing | Cannot detect directly | Excellent, captures different transcript isoforms [18] |

| Gene Expression | Not applicable | Primary application, quantitative measurement |

Experimental Design and Implementation

Integrated Sequencing Approaches in Oncology Research

Sophisticated research protocols increasingly leverage both DNA and RNA sequencing to maximize molecular insights. A prominent approach involves using DNA-seq as a comprehensive discovery tool for genetic variants, followed by RNA-seq to validate functional expression and biological relevance of these alterations [21]. This integrated strategy is particularly valuable for distinguishing driver mutations that are actively transcribed from passenger mutations that may not contribute to the oncogenic phenotype.

Real-world evidence supports this combined approach. A 2025 study on clinical utility of targeted RNA-seq analyzed 2,310 neoplasms and demonstrated that RNA-seq provided valuable molecular data for 87% of patients, including revised diagnoses and identification of clinically actionable alterations that led to treatment changes [22]. Similarly, research on reference samples showed that RNA-seq can uniquely identify variants with significant pathological relevance that were missed by DNA-seq, while also confirming expression of DNA-identified variants [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of DNA and RNA sequencing protocols requires carefully selected reagents and tools. The following table outlines essential components for integrated sequencing experiments in oncology research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated Sequencing

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid Extraction Kits | AllPrep DNA/RNA/miRNA Universal Kit [23] | Simultaneous purification of gDNA and total RNA from limited samples, crucial for paired analysis |

| Target Enrichment Systems | Agilent Clear-seq; Roche Comprehensive Cancer panels [21] | Hybridization-capture baits for focused sequencing of cancer-related genes; variable probe lengths affect coverage |

| Library Preparation Chemistry | Illumina TruSeq; Ion Torrent Oncomine | Platform-specific reagents for NGS library construction; impact compatibility and multiplexing capabilities |

| RNA-Seq Specific Tools | Ribosomal RNA depletion kits; Reverse transcriptases | Remove abundant rRNA to enhance mRNA sequencing depth; critical for transcriptome analysis |

| Quality Control Assays | Bioanalyzer RNA integrity assessment; Fluorometric DNA/RNA quantification | Essential for evaluating sample quality pre-sequencing, particularly for FFPE-derived material |

| Hybridization Capture Reagents | Biotinylated probes; Strepavidin beads [20] | Enable targeted enrichment for fusion detection, especially valuable for novel fusion discovery |

Addressing Technical Challenges in Sequencing Workflows

Oncology researchers must navigate several technical challenges when implementing DNA and RNA sequencing. For RNA-seq, sample quality is paramount due to RNA's lability, particularly in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) clinical specimens where RNA degradation can occur [22]. Implementing rigorous quality control measures, such as RNA Integrity Number (RIN) assessment, is essential for generating reliable data. For DNA-seq, achieving sufficient sequencing depth in tumor samples with low purity or high stromal contamination requires careful experimental design and bioinformatic correction.

The choice between whole transcriptome sequencing and targeted RNA-seq represents another key consideration. While whole transcriptome approaches provide comprehensive expression profiling, targeted RNA-seq panels offer deeper coverage of clinically relevant genes and can improve detection of low-abundance transcripts [21]. Research demonstrates that targeted approaches are particularly valuable for detecting expressed mutations with higher accuracy and reliability, especially for rare alleles and evolving mutant clones [21].

Applications in Precision Oncology and Drug Development

Enhancing Therapeutic Target Discovery and Validation

The complementary nature of DNA and RNA sequencing creates powerful synergies for identifying and validating novel therapeutic targets in oncology. DNA-seq can comprehensively catalog all genetic alterations present in a tumor, while RNA-seq determines which of these alterations are actively transcribed and likely to contribute to the oncogenic phenotype. This integrated approach is particularly valuable for prioritizing targets for drug development, as it helps distinguish functionally relevant driver mutations from biologically inert passenger mutations [21].

In clinical practice, this combined methodology directly impacts patient care. Studies have demonstrated that RNA-seq identifies clinically actionable fusions in lung adenocarcinomas that had no mitogenic driver alteration detected by DNA sequencing alone [24] [22]. Furthermore, RNA-seq provides critical functional characterization of variants of uncertain significance (VUS) identified through DNA sequencing, enabling more accurate interpretation of their clinical relevance and guiding appropriate targeted therapy selection [21].

Advancing Biomarker Development and Clinical Trial Design

In drug development, integrating DNA and RNA sequencing enables more sophisticated biomarker strategies and patient stratification approaches. By capturing both genetic alterations and their functional consequences, researchers can develop composite biomarkers that better predict treatment response. This is particularly relevant for immuno-oncology, where RNA-seq-derived gene expression signatures can identify tumors with immunologically "hot" microenvironments that may respond better to checkpoint inhibitors.

Clinical trials increasingly incorporate both DNA and RNA sequencing in biomarker-informed designs. The use of RNA-seq to detect neoantigens for personalized cancer vaccines represents a cutting-edge application, where expressed mutations identified through RNA sequencing are prioritized for vaccine development [21]. This approach ensures that therapeutic interventions target immunogenic peptides that are actually presented on the tumor cell surface, increasing the likelihood of clinical efficacy.

Emerging Technologies and Methodological Innovations

The field of cancer genomics continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging technologies poised to enhance the complementary roles of DNA and RNA sequencing. Single-cell sequencing approaches now enable simultaneous DNA and RNA profiling at the individual cell level, revealing tumor heterogeneity and clonal evolution with unprecedented resolution. Long-read sequencing technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore facilitate more accurate detection of complex structural variants and full-length transcript isoforms, addressing limitations of short-read sequencing for characterizing gene fusions and alternative splicing events [19].

Methodologically, integrated bioinformatics pipelines are being developed to jointly analyze DNA and RNA sequencing data from the same samples, providing more powerful approaches for linking genetic alterations to their functional consequences. These tools are particularly valuable for identifying expressed neoantigens for personalized cancer immunotherapy and elucidating non-coding drivers of oncogenesis through their effects on gene expression [21].

DNA and RNA sequencing represent complementary rather than competing technologies in oncology research and clinical practice. While DNA-seq provides a comprehensive catalog of genetic alterations, RNA-seq adds the crucial dimension of functional activity, revealing which alterations are actively transcribed and likely to drive cancer pathogenesis. The integration of both data types creates a more complete understanding of tumor biology, enabling more accurate diagnosis, prognostic stratification, and therapeutic target identification.

As sequencing technologies continue to advance and become more accessible, the routine implementation of both DNA and RNA sequencing in cancer research and clinical diagnostics will maximize our ability to decipher the complex molecular mechanisms driving malignancy. This integrated approach represents the foundation of precision oncology, ensuring that patients receive targeted therapies matched to the specific genetic and functional characteristics of their tumors. For researchers and drug development professionals, leveraging the complementary strengths of both technologies provides the most powerful approach for advancing our understanding and treatment of cancer.

The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has fundamentally transformed oncology research and clinical practice, enabling a shift from histology-based to molecularly-driven cancer classification. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical overview of four cornerstone sequencing technologies: whole-exome sequencing (WES), whole-genome sequencing (WGS), targeted gene panels, and RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq). We examine the technical principles, clinical applications, advantages, and limitations of each method, supported by recent comparative data. Within the framework of precision oncology, we demonstrate how these technologies facilitate the identification of actionable biomarkers—including single nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions/deletions (indels), copy number variations (CNVs), structural variants (SVs), gene fusions, and tumor mutational burden (TMB)—that inform therapeutic decision-making. Detailed experimental protocols and workflow visualizations are provided to guide researchers in technology selection and implementation. The integration of these multidimensional genomic and transcriptomic data is paving the way for increasingly personalized cancer diagnostics and treatment strategies.

Precision oncology represents a paradigm shift in cancer care, moving from blanket treatment approaches to strategies tailored to the individual molecular profile of a patient's tumor [25] [26]. This approach is predicated on comprehensive molecular characterization to identify targetable alterations driving tumorigenesis. DNA and RNA sequencing technologies form the foundational toolkit enabling this transformation, each offering distinct insights into tumor biology.

The three principal forms of NGS include whole genome sequencing (WGS), whole exome sequencing (WES), and targeted sequencing (TS) or panel sequencing [27]. WGS provides the most comprehensive coverage of the entire ~3.2 billion base pair human genome, encompassing both coding and non-coding regions, while WES targets the ~1-2% of the genome that encodes proteins [26] [28]. In contrast, targeted panels focus on a curated set of genes known to be involved in tumorigenesis, allowing for deeper sequencing at lower cost and complexity [27]. RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) complements DNA-based methods by capturing the dynamic transcriptome, revealing gene expression levels, fusion events, and splice variants [26] [29].

The clinical utility of these technologies is evidenced by their ability to identify biomarkers such as microsatellite instability (MSI), tumor mutational burden (TMB), and homologous recombination deficiency (HRD), which predict response to targeted therapies and immunotherapies [30] [26]. As the diagnostic landscape evolves, understanding the technical specifications, applications, and trade-offs of each method becomes imperative for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to advance personalized cancer care.

Technology Comparison and Clinical Applications

Technical Specifications and Performance Characteristics

The selection of an appropriate sequencing methodology depends heavily on the research question, available resources, and desired clinical applications. Each platform offers distinct advantages and limitations in coverage, resolution, and cost-effectiveness.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Sequencing Technologies in Oncology

| Feature | Targeted Panels | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Coverage | Selected genes (dozens to ~500) | Protein-coding exons (~1-2% of genome) | Entire genome (~3.2 billion bp) | Full transcriptome (coding and non-coding RNA) |

| Primary Detectable Alterations | SNVs, indels, CNVs, specific fusions | SNVs, indels, CNVs | SNVs, indels, CNVs, SVs, non-coding variants | Gene expression, fusions, splice variants, allele-specific expression |

| Sequencing Depth | Very high (500–1000x or higher) | High (100–200x) | Moderate (30–60x) | Variable (depends on application) |

| Relative Cost | Low | Moderate | High | Moderate |

| Key Advantages | Cost-effective, high sensitivity for low-frequency variants, faster turnaround, simpler data analysis | Balances cost with comprehensive coverage of coding regions where most known disease variants reside | Most comprehensive; detects all variant types including structural variants and non-coding alterations; gold standard for germline | Functional view of biology; identifies expressed mutations, fusions, and immune context; crucial for resolving ambiguous cases |

| Major Limitations | Limited to known genes; may miss novel biomarkers and complex alterations | Misses non-coding and regulatory variants; may miss complex structural variants | Higher cost and data burden; may require greater computational resources | Does not directly detect DNA alterations; requires high-quality RNA |

Targeted panels, such as the TruSight Oncology 500, focus on a pre-defined set of genes with known clinical or functional significance in cancer, enabling deep sequencing (1000x or higher) that is ideal for detecting low-frequency variants in challenging samples like circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) or formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue [27]. WES provides a broader view, capturing approximately 95% of the exonic regions where an estimated 85% of disease-causing variants are located, making it a powerful tool for novel gene discovery while remaining more cost-effective than WGS [28]. In contrast, WGS interrrogates the entire genome, providing an unbiased platform for detecting the full spectrum of genomic alterations, including those in non-coding regulatory regions, and is considered the gold standard for identifying germline predisposition variants and complex structural rearrangements [26] [28].

RNA-Seq delivers a dynamic snapshot of gene expression, capturing the biologically relevant subset of DNA alterations that are actively transcribed [29]. It is particularly superior for detecting gene fusions and splice variants, as it sequences the actual transcript products, often revealing clinically actionable alterations that may be missed by DNA-only approaches [26] [29]. Emerging applications like single-cell RNA-Seq (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics further resolve tumor heterogeneity and cellular interactions within the tumor microenvironment [25] [29].

Clinical Utility and Biomarker Discovery

The translation of genomic findings into clinical action is the central tenet of precision oncology. Different sequencing technologies contribute uniquely to biomarker discovery and patient stratification.

Table 2: Clinical Applications and Key Biomarkers by Sequencing Technology

| Technology | Exemplary Clinical Applications | Key Biomarkers Detected | Impact on Therapy Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Panels | Routine molecular profiling for common solid tumors (e.g., NSCLC, CRC); therapy selection | SNVs/indels in EGFR, BRAF, KRAS; CNVs in HER2; MSI, TMB | Directs use of corresponding targeted therapies (e.g., EGFR inhibitors, BRAF inhibitors) |

| WES | Broad screening for rare cancers; identification of novel driver mutations; pediatric cancers | Somatic driver mutations (e.g., PIK3CA, BRCA1/2); CNVs; MSI, TMB | Expands therapeutic options beyond standard panels; identifies clinical trial eligibility |

| WGS | Hereditary cancer predisposition; complex structural variants; cases with ambiguous findings | Germline variants (e.g., Lynch syndrome); SVs, chromothripsis; HRD scores | Informs targeted therapy and immunotherapy; identifies familial risk |

| RNA-Seq | Diagnosis of fusion-driven cancers (e.g., sarcomas, lymphomas); resolving equivocal IHC/FISH | Gene fusions (e.g., ALK, ROS1, NTRK, RET); gene expression signatures (e.g., OncoPrism) | Critical for selecting fusion-targeted therapies (e.g., TRK inhibitors); improves ICI response prediction |

A direct comparative study of WES/WGS/TS and panel sequencing in 20 patients with rare or advanced tumors found that WES/WGS ± transcriptome sequencing (TS) generated a median of 3.5 therapy recommendations per patient, compared to 2.5 for the gene panel [30]. Crucially, approximately one-third of the therapy recommendations from WES/WGS ± TS relied on biomarkers not covered by the panel, and two out of ten implemented therapies were based on these additional findings, highlighting the potential for expanded clinical benefit with more comprehensive profiling [30].

From an economic perspective, comprehensive profiling can be cost-effective. In advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), a model-based analysis found that using WES/WTS reduced costs by $14,602 per patient compared to sequential single-gene testing while also improving survival outcomes by better identifying patients eligible for targeted therapies and clinical trials [31]. RNA-Seq further enhances this value; in scenarios where RNA fusion prevalence ranges from 2.5% to 14%, adding RNA to DNA sequencing reduced costs by $400–$1,724 per patient and increased the identification of actionable alterations by 2.3%–13.0% [31].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Comparative Sequencing Analysis

The following detailed methodology outlines a approach for comparing sequencing outputs from different platforms, as referenced in recent studies [30].

1. Sample Selection and Nucleic Acid Extraction:

- Select fresh-frozen or FFPE tumor tissue samples with matched normal tissue (e.g., blood, saliva) for germline comparison.

- Extract high-molecular-weight DNA and high-integrity RNA from the same tumor tissue block using standardized kits. Quantify and qualify nucleic acids using fluorometry (e.g., Qubit) and fragment analyzers (e.g., Bioanalyzer). For FFPE samples, prioritize RNA extraction protocols designed for degraded samples.

2. Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- WES Library: Use a hybridization-based capture kit (e.g., Illumina Nexome) to enrich for exonic regions. Fragment DNA, ligate adapters, and perform hybrid capture with biotinylated probes targeting the human exome.

- WGS Library: Utilize a PCR-free library preparation kit (e.g., Illumina DNA PCR-Free Prep) to minimize bias. Fragment DNA, repair ends, adenylate, and ligate with indexing adapters.

- Targeted Panel Library: Employ commercially available kits (e.g., Illumina TSO500) that use hybrid capture or amplicon-based approaches for a predefined gene set.

- RNA-Seq Library: For whole transcriptome, use kits with ribosomal RNA depletion (e.g., Illumina TruSeq Stranded Total RNA). For 3'-end counting from FFPE samples, use targeted methods like QuantSeq FPE [29]. Perform poly(A) selection for mRNA enrichment.

- Sequence all libraries on an appropriate NGS platform (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) to a desired median depth: WES (100–200x), WGS (30–60x), Panels (500–1000x), RNA-Seq (50–100 million reads).

3. Bioinformatic Analysis and Variant Calling:

- Data Preprocessing: Align sequence reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using aligners like BWA-MEM (for DNA) or STAR (for RNA).

- Variant Calling:

- SNVs/Indels: Use callers like GATK Mutect2 (somatic) and HaplotypeCaller (germline) for WES/WGS. Use panel-specific pipelines (e.g., Dragen) for targeted data.

- CNVs/SVs: Utilize tools like Control-FREEC (CNVs), Manta (SVs) for WES/WGS.

- RNA Fusions: Implement fusion callers such as Arriba and STAR-Fusion on RNA-Seq data [30] [26].

- Biomarkers: Calculate TMB (mutations/Mb), MSI from DNA data, and gene expression signatures from RNA data.

4. Clinical Interpretation and Actionability Assessment:

- Annotate variants using databases like ClinVar, COSMIC, and OncoKB.

- Curbate molecular findings and assess clinical relevance based on evidence levels (e.g., ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability).

- Present comprehensive report in a molecular tumor board to formulate integrated therapy recommendations.

Diagram 1: Integrated sequencing and analysis workflow for precision oncology.

Protocol for RNA-Based Biomarker Development

This protocol details the development of a gene expression classifier for predicting response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), as demonstrated by the OncoPrism test for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) [29].

1. Cohort Selection and Sample Preparation:

- Establish a retrospective cohort of patients with a specific cancer type (e.g., RM-HNSCC) treated with ICI monotherapy. Collect pre-treatment FFPE tumor biopsies and associated clinical outcome data (e.g., disease control, overall survival).

- RNA Extraction: Cut 5–10 μm sections from FFPE blocks. Deparaffinize using xylene and ethanol washes. Extract total RNA using a commercial FFPE RNA extraction kit, including a DNase digestion step. Assess RNA quality (e.g., DV200 score).

2. Targeted RNA-Seq Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Use a 3' mRNA-Seq method (e.g., QuantSeq FPE) for library preparation from 10–100 ng of total RNA. This method is optimized for degraded FFPE RNA and involves:

- First-Strand Synthesis: Use an oligo-dT primer containing an Illumina-compatible adapter sequence.

- RNA Template Degradation: Enzymatically degrade the original RNA template.

- Second-Strand Synthesis: Use a random primer containing the second Illumina adapter sequence.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the final library using a limited-cycle PCR with indexed primers.

- Purify the final libraries and quantify by qPCR. Pool libraries at equimolar ratios and sequence on a mid-output Illumina flow cell (e.g., NextSeq 500/550) to a depth of 5–10 million reads per sample.

3. Bioinformatics and Classifier Training:

- Expression Quantification: Trim adapter sequences and align reads to the reference transcriptome (e.g., GENCODE) using a lightweight aligner like STARsolo or Bowtie2. Quantify gene-level counts.

- Feature Selection: Perform quality control to remove low-quality samples. Using the training cohort, apply statistical methods (e.g., LASSO regression) to a predefined immune-related gene set to identify a minimal panel of features (e.g., ~60 genes) most predictive of clinical outcome.

- Model Training: Train a logistic regression model using the selected features to generate a continuous "OncoPrism Score" (0–100) predictive of disease control. The model is trained to weight the expression values of each feature to maximize predictive accuracy.

4. Clinical Validation:

- Validate the locked model in one or more independent validation cohorts.

- Stratify patients into risk groups (e.g., Low, Medium, High) based on the score threshold established in the training phase.

- Evaluate performance by calculating sensitivity, specificity, and negative/positive predictive values for predicting disease control and correlating the score with overall survival.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of sequencing protocols relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key materials used in the featured experiments and the broader field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Oncology Sequencing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products/Kits |

|---|---|---|

| FFPE RNA Extraction Kit | Isolves and purifies degraded RNA from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue samples, a common clinical source. | Qiagen RNeasy FFPE Kit, Thermo Fisher RecoverAll Total Nucleic Acid Isolation Kit |

| Hybridization Capture Probes | Biotinylated oligonucleotide probes that bind to and enrich target genomic regions (exome or gene panel) during library preparation. | Illumina Nexome, IDT xGen Exome Research Panel, TruSight Oncology 500 Probes |

| 3' mRNA-Seq Library Prep Kit | Generates strand-specific RNA-Seq libraries from the 3' end of transcripts, ideal for degraded RNA and gene expression quantification. | Lexogen QuantSeq FPE, Takara Bio SMART-Seq STRT |

| PCR-Free WGS Kit | Prepares sequencing libraries for whole genome analysis without PCR amplification steps, reducing bias and improving uniformity. | Illumina DNA PCR-Free Prep, TruSeq DNA PCR-Free |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | Software suites for aligning sequencing reads, calling genetic variants, and performing quality control. | GATK, Dragen, STAR, Arriba, Control-FREEC |

The expanding diagnostic toolbox in oncology, comprising targeted panels, WES, WGS, and RNA-Seq, provides researchers and clinicians with a powerful, multi-faceted approach to deciphering cancer complexity. While targeted panels offer a cost-effective and efficient method for routine screening of established biomarkers, comprehensive approaches like WES, WGS, and RNA-Seq are indispensable for uncovering the full spectrum of molecular alterations, especially in rare cancers or cases with inconclusive findings. The integration of DNA and RNA sequencing, in particular, maximizes the identification of clinically actionable alterations, improves diagnostic yield, and has been shown to be economically viable by better matching patients to effective therapies.

Future advancements will be driven by the continued reduction in sequencing costs, the maturation of bioinformatic tools and artificial intelligence for data interpretation, and the development of even more sophisticated single-cell and spatial multiomics technologies. As the list of biomarker-driven therapies grows, the strategic selection and integration of these core sequencing technologies will remain the cornerstone of accelerating translational cancer research and delivering on the promise of personalized medicine.

From Lab to Clinical Report: Methodological Workflows and Translational Applications

In modern oncology research, the quality of sequencing data is profoundly influenced by the initial sample input. The choice between formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE), fresh-frozen (FF), and liquid biopsy specimens represents a critical juncture in experimental design, with each source presenting unique advantages, challenges, and technical requirements. Within the broader principles of DNA and RNA sequencing, proper sample handling and preparation are not merely preliminary steps but fundamental determinants of data reliability and biological insight. This guide provides a comprehensive framework for navigating sample input decisions, offering best practices tailored to the distinct characteristics of each sample type to empower researchers in generating robust, reproducible sequencing data for cancer research and drug development.

Section 1: Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) Samples

Characteristics and Applications

FFPE tissues represent one of the most accessible biological resources in both research and clinical settings due to their widespread use in pathology for preserving tissue morphology. However, the process of formalin fixation and paraffin embedding introduces significant challenges for molecular analyses. FFPE-derived RNA is often fragmented, chemically modified, and degraded, making it suboptimal for gene expression profiling. The chemical crosslinks formed during fixation and continued degradation over time result in RNA of lower quality compared to fresh-frozen alternatives. Despite these limitations, the ubiquity of FFPE tissue specimens in tissue banks and pathology laboratories worldwide makes them an invaluable resource for translational research, particularly for biomarker discovery and validation studies [32] [33].

Technical Considerations and Best Practices

Successful sequencing from FFPE samples requires careful attention to multiple technical factors. RNA integrity is typically assessed using the DV200 metric (percentage of RNA fragments >200 nucleotides), with values above 30% generally indicating samples are usable for RNA-seq protocols. For library preparation, specialized stranded RNA-seq kits designed specifically for FFPE material are essential. A recent 2025 comparative analysis evaluated two prominent approaches: the TaKaRa SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit v2 (Kit A) and the Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep Ligation with Ribo-Zero Plus (Kit B). The study revealed that Kit A achieved comparable gene expression quantification to Kit B while requiring 20-fold less RNA input, a crucial advantage for limited samples, albeit with increased sequencing depth requirements. Kit B demonstrated superior performance in ribosomal RNA depletion (0.1% vs. 17.45% rRNA content) and lower duplication rates (10.73% vs. 28.48%) [32].

For data analysis, specialized normalization methods are recommended to address the unique characteristics of FFPE data. MIXnorm has been specifically developed for FFPE RNA-seq data to handle its prominent sparsity (excessive zero or small counts) caused by RNA degradation. This method employs a two-component mixture model that models non-expressed genes using zero-inflated Poisson distributions and expressed genes using truncated normal distributions, outperforming conventional normalization methods designed for fresh-frozen samples [33].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of FFPE-Compatible RNA-Seq Library Prep Kits

| Parameter | TaKaRa SMARTer Stranded Total RNA-Seq Kit v2 | Illumina Stranded Total RNA Prep Ligation with Ribo-Zero Plus |

|---|---|---|

| Minimum RNA Input | Low (20-fold less than Kit B) | Standard |

| rRNA Depletion Efficiency | 17.45% rRNA content | 0.1% rRNA content |

| Duplication Rate | 28.48% | 10.73% |

| Reads Mapping to Intronic Regions | 35.18% | 61.65% |

| Key Advantage | Superior for low-input samples | Better rRNA depletion and lower duplication |

| Sequencing Depth Recommendation | Higher | Standard |

Section 2: Fresh-Frozen (FF) Samples

Characteristics and Applications

Fresh-frozen tissues are considered the gold standard for molecular analysis as freezing rapidly preserves RNA, proteins, and DNA in a state closer to their native condition. FF tissues are well-suited for gene expression measurements and provide high-quality nucleic acids for a wide range of sequencing applications. The integrity of molecular components in FF samples makes them particularly valuable for comprehensive transcriptome analyses, including alternative splicing detection, novel transcript identification, and fusion gene discovery [33] [34].

Technical Considerations and Best Practices

The critical factor for FF sample quality is immediate preservation after collection. Cellular degradation and enzymatic activity begin immediately upon tissue excision, compromising sample integrity. According to Nature Protocols, tissue samples should be frozen within 30 minutes of excision to preserve RNA, protein, and DNA quality. Before freezing, samples should be kept on ice or at 4°C to prevent heat damage or accelerated degradation (pre-cooling) [34].

Snap-freezing in liquid nitrogen or on dry ice is the most effective preservation method for fresh-frozen tissue. This technique ensures rapid cooling, preventing the formation of ice crystals that could disrupt cellular structures. For optimal results, researchers should submerge tissue directly in liquid nitrogen or use a dry ice and isopentane bath. Slow freezing should be avoided as it allows ice crystal formation that causes significant tissue damage, particularly to delicate samples like brain or skeletal muscle [34].

Long-term storage of FF tissues should be at -80°C or lower in dedicated ultra-low temperature freezers. Liquid nitrogen storage provides an alternative for long-term preservation. To minimize degradation, researchers should avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles by aliquoting tissues during initial processing. During transportation, maintaining an unbroken cold chain is essential, using dry ice or liquid nitrogen dry shippers with temperature data loggers to monitor conditions throughout the shipping process [34].

Table 2: Fresh-Frozen Tissue Handling Guidelines

| Processing Stage | Key Practice | Technical Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Preservation Timing | Immediate freezing | Within 30 minutes of excision |

| Freezing Method | Snap-freezing | Liquid nitrogen submersion or dry ice-isopentane bath |

| Storage Temperature | Ultra-low temperature | -80°C or lower |

| Freeze-Thaw Cycles | Minimize | Aliquot during processing |

| Transport | Maintain cold chain | Dry ice with temperature monitoring |

Section 3: Liquid Biopsy Samples

Characteristics and Applications

Liquid biopsy represents a minimally invasive approach to cancer molecular profiling that analyzes tumor-derived materials from various body fluids, primarily blood. This methodology provides several advantages over traditional tissue biopsies, including the ability to perform serial sampling for monitoring disease progression and treatment response, capturing tumor heterogeneity, and profiling tumors that are difficult to access physically. Liquid biopsy is particularly valuable for patients unfit for invasive tissue biopsy procedures and for real-time monitoring of clonal evolution during treatment [35] [36].

The analytes used in liquid biopsy include circulating tumor cells (CTCs), circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), extracellular vesicles (EVs), and cell-free RNA (cfRNA). Each of these components offers unique biological information and presents distinct technical challenges for isolation and analysis. CTCs are rare cells shed from tumors into circulation (approximately 1 CTC per million leukocytes) with a short half-life of 1-2.5 hours in peripheral blood. ctDNA consists of short DNA fragments (20-50 base pairs) that constitute approximately 0.1-1.0% of total cell-free DNA in cancer patients [35].

Technical Considerations and Best Practices