Foundation Models for Cancer Imaging Biomarkers: A New Paradigm in Precision Oncology

Foundation models, large-scale deep learning models pre-trained on vast datasets through self-supervised learning, are revolutionizing the discovery of cancer imaging biomarkers.

Foundation Models for Cancer Imaging Biomarkers: A New Paradigm in Precision Oncology

Abstract

Foundation models, large-scale deep learning models pre-trained on vast datasets through self-supervised learning, are revolutionizing the discovery of cancer imaging biomarkers. This article explores their foundational principles, methodological applications, and transformative potential for researchers and drug development professionals. We detail how these models facilitate robust biomarker development, even with limited annotated data, for tasks ranging from lesion classification and malignancy diagnosis to prognostic outcome prediction. The content further addresses critical challenges in implementation, including data heterogeneity and model generalizability, and provides a comparative analysis of model performance and validation strategies. By synthesizing evidence from recent studies and benchmarks, this article serves as a comprehensive guide to the current state and future trajectory of foundation models in accelerating the translation of quantitative imaging biomarkers into clinical and research practice.

The Paradigm Shift: Understanding Foundation Models and Their Role in Biomarker Discovery

Defining Foundation Models and Self-Supervised Learning in Medical Imaging

Foundation Models (FMs) represent a transformative class of artificial intelligence systems characterized by their training on vast, diverse datasets using self-supervised learning (SSL) techniques, enabling them to serve as adaptable base models for numerous downstream tasks [1] [2]. In medical imaging, these models fundamentally shift the development paradigm from building task-specific models from scratch to adapting powerful pre-trained models for specialized clinical applications. Self-supervised learning provides the foundational methodology that enables this approach by learning representative features from unlabeled data, circumventing one of the most significant bottlenecks in medical AI: the scarcity of expensive, expertly annotated datasets [3] [4]. Within oncology, this technological convergence creates unprecedented opportunities for discovering and validating cancer imaging biomarkers by leveraging the rich information encoded in medical images without complete reliance on labeled datasets [4] [5].

Core Technical Principles

Architectural Foundations of Foundation Models

Foundation models in medical imaging typically leverage transformer-based architectures or convolutional networks, scaled to unprecedented sizes and trained on massive, multi-institutional datasets. The 3DINO-ViT model exemplifies this approach, implementing a vision transformer (ViT) adapted for 3D medical volumes while incorporating a 3D ViT-Adapter module to inject spatial inductive biases critical for dense prediction tasks like segmentation [3]. These architectures succeed through pre-training on extraordinarily diverse datasets; for instance, 3DINO-ViT was trained on approximately 100,000 3D scans spanning MRI, CT, and PET modalities across over 10 different organs [3] [6]. This diversity forces the model to learn robust, general-purpose representations rather than features specific to any single modality or anatomical region.

Self-Supervised Learning Methodologies

SSL methods construct learning signals directly from the structure of unlabeled data. The 3DINO framework implements a sophisticated approach combining both image-level and patch-level objectives, adapting the DINOv2 pipeline to 3D medical imaging inputs [3]. As shown in the experimental workflow, this process involves generating multiple augmented views of each 3D volume—typically two global and eight local crops—then training the model using a self-distillation objective where a student network learns to match the output of a teacher network across these different views [3]. Alternative SSL approaches include masked autoencoders, which randomly mask portions of input images and train models to reconstruct the missing content, and contrastive learning, which learns representations by maximizing agreement between differently augmented views of the same image while minimizing agreement with other images [2].

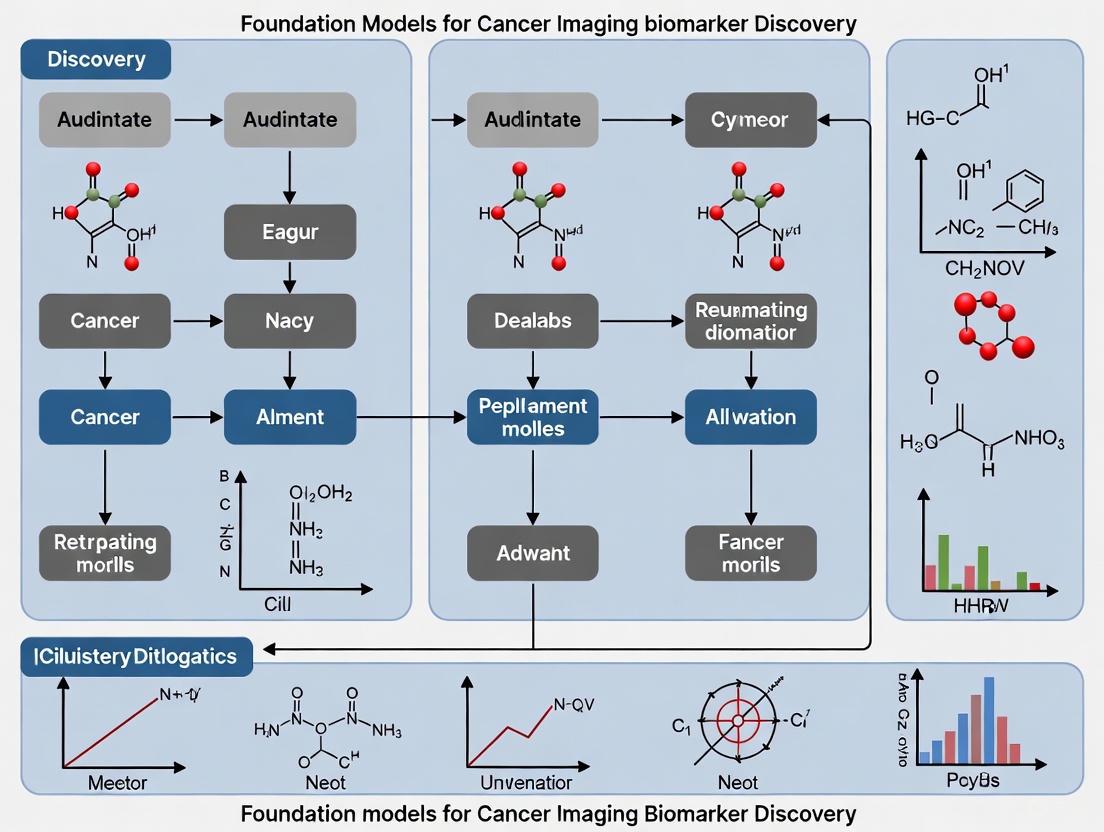

Figure 1: Self-distillation with no labels (3DINO) workflow for 3D medical imaging.

Application to Cancer Imaging Biomarker Discovery

Enhanced Biomarker Discovery with Limited Data

Foundation models demonstrate particular utility in scenarios with limited annotated data, which frequently challenges cancer biomarker discovery. In one comprehensive study, a foundation model trained on 11,467 radiographic lesions significantly outperformed conventional supervised approaches and other state-of-the-art pre-trained models, especially when training dataset sizes were severely limited [4]. The model served as a powerful feature extractor for various cancer imaging tasks, including lesion anatomical site classification (balanced accuracy: 0.804), lung nodule malignancy prediction (AUC: 0.944), and prognostic biomarker development for non-small cell lung cancer [4]. When training data was reduced to only 10% of the original dataset, the foundation model implementation showed remarkably robust performance, declining only 9% in balanced accuracy compared to significantly larger drops observed in baseline methods [4].

Quantitative Performance in Downstream Tasks

Table 1: Performance comparison of foundation models versus baseline methods on medical imaging tasks

| Task | Dataset | Foundation Model Performance | Next Best Baseline Performance | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brain Tumor Segmentation | BraTS (10% data) | 0.90 Dice [3] | 0.87 Dice (Random) [3] | +3.4% [3] |

| Abdominal Organ Segmentation | BTCV (25% data) | 0.77 Dice [3] | 0.59 Dice (Random) [3] | +30.5% [3] |

| COVID-19 Classification | COVID-CT-MD | 23% higher AUC [3] | Next best baseline | Significant [3] |

| Lung Nodule Malignancy | LUNA16 | 0.944 AUC [4] | 0.917 AUC (Med3D) [4] | +2.9% [4] |

| Age Classification | ICBM | 13.4% higher AUC [3] | Next best baseline | Significant [3] |

Table 2: Impact of limited data on foundation model performance for anatomical site classification

| Training Data Percentage | Foundation Model (Features) Balanced Accuracy | Foundation Model (Fine-tuned) Balanced Accuracy | Best Baseline Balanced Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100% | 0.779 [4] | 0.804 [4] | 0.775 (Med3D fine-tuned) [4] |

| 50% | 0.765 [4] | 0.781 [4] | 0.743 (Med3D fine-tuned) [4] |

| 20% | 0.741 [4] | 0.752 [4] | 0.692 (Med3D fine-tuned) [4] |

| 10% | 0.709 [4] | 0.698 [4] | 0.631 (Med3D fine-tuned) [4] |

Experimental Framework and Methodologies

Implementation Approaches for Downstream Tasks

Two primary implementation strategies have emerged for adapting foundation models to specific cancer imaging biomarker tasks. The feature extraction approach uses the pre-trained foundation model as a fixed feature extractor, with a simple linear classifier trained on top of these features for the specific downstream task [4]. This method offers computational efficiency and strong performance in limited-data regimes. The fine-tuning approach further trains the foundation model's weights on labeled data from the target task, typically achieving superior performance when sufficient labeled data is available but requiring more computational resources and carrying higher risk of overfitting with small datasets [4]. Research indicates that the feature extraction approach often outperforms fine-tuning in severely data-limited scenarios common to specialized cancer biomarker applications [4].

Validation Frameworks and Evaluation Metrics

Rigorous evaluation of foundation models for biomarker discovery necessitates multi-tiered validation frameworks. The AI4HI network advocates for decentralized clinical validation and continuous training frameworks to ensure model reliability across diverse populations and clinical settings [2]. Comprehensive benchmarks like those established across 11 medical datasets in the MedMNIST collection evaluate models on both in-domain performance and out-of-distribution generalization [7]. Critical evaluation metrics include area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for classification tasks, Dice coefficient for segmentation accuracy, and balanced accuracy for multi-class problems with imbalanced distributions [3] [4]. Additionally, biomarker discovery applications require assessment of model stability through test-retest analyses and evaluation of biological relevance via correlation with genomic expression data [4].

Figure 2: Multi-dataset validation framework for foundation models in biomarker discovery.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential computational resources for implementing foundation models in medical imaging research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools & Frameworks | Function in Research Pipeline |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Models | 3DINO-ViT, Med3D, Models Genesis | Provide foundational feature extractors for downstream tasks, reducing computational requirements [3] [4] |

| SSL Frameworks | 3DINO, SimCLR, SwAV, NNCLR | Enable self-supervised pre-training on unlabeled datasets [3] [4] |

| Medical Imaging Platforms | MONAI, NVIDIA CLARA | Offer specialized implementations of medical AI algorithms and data loaders [3] |

| Model Architectures | Vision Transformer (ViT), Swin Transformer, Convolutional Encoders | Provide backbone networks for foundation models [3] [4] |

| Evaluation Benchmarks | MedMNIST+, BraTS, BTCV, LUNA16 | Standardized datasets for comparative performance assessment [3] [7] |

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite their promising performance, foundation models in medical imaging face several significant challenges. Data heterogeneity across institutions, modalities, and scanner manufacturers can limit model generalizability [2]. Limited transparency and explainability remain concerns for clinical adoption, particularly for high-stakes applications like cancer diagnosis [2] [5]. Computational requirements for training and deploying large foundation models present practical barriers for widespread implementation [3]. Additionally, models may perpetuate or amplify biases present in training data if not carefully addressed [2].

Future development directions include creating more efficient model architectures, improving explainability through techniques like attention visualization, establishing standardized validation frameworks across institutions, and developing federated learning approaches to train models on distributed data without centralization [2]. The integration of imaging biomarkers with other data modalities—including genomics, proteomics, and clinical records—represents a particularly promising direction for creating comprehensive biomarker signatures in oncology [8] [5]. As these technologies mature, foundation models are poised to significantly accelerate the discovery and validation of imaging biomarkers, ultimately enhancing precision oncology through improved diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection.

The development of artificial intelligence (AI) for cancer imaging represents a paradigm shift in oncology, promising enhanced diagnostic precision, prognostic stratification, and personalized treatment strategies. However, this potential is constrained by a critical bottleneck: the scarcity of large, annotated medical imaging datasets. Unlike natural image analysis where massive labeled datasets like ImageNet contain millions of images, medical imaging research faces fundamental limitations in data availability due to patient privacy concerns, the specialized expertise required for annotation, and the resource-intensive nature of data collection in clinical settings [9]. This scarcity profoundly impacts the development of robust AI models, particularly deep learning networks that typically require extensive labeled examples to generalize effectively without overfitting [9].

Within this challenging landscape, foundation models have emerged as a transformative approach. These models, characterized by large-scale architectures pretrained on vast amounts of unannotated data, can be adapted to various downstream tasks with limited task-specific labels [4] [10]. In cancer imaging biomarker discovery, foundation models pretrained through self-supervised learning (SSL) techniques demonstrate remarkable capability to overcome data scarcity constraints, enabling more accurate and efficient development of imaging biomarkers even when labeled training samples are severely limited [4]. This technical guide examines the foundational principles, methodological frameworks, and experimental evidence supporting the use of foundation models to address the critical challenge of data scarcity in cancer imaging research.

Foundation Models: A Technical Framework for Overcoming Data Scarcity

Conceptual Architecture and Core Principles

Foundation models in medical imaging are built on a core architectural principle: a single large-scale model trained on extensive diverse data serves as the foundation for various downstream tasks [4]. These models are typically pretrained using self-supervised learning (SSL), a paradigm that leverages the inherent structure and relationships within unlabeled data to learn generalized, task-agnostic representations [4]. The pretraining phase eliminates the dependency on manual annotations, thereby bypassing the primary constraint of labeled data scarcity.

The conceptual workflow follows a two-stage process:

- Pretraining Phase: A model (typically a convolutional encoder) is trained on large-scale unlabeled medical imaging datasets using SSL objectives that create supervisory signals from the data itself.

- Adaptation Phase: The pretrained model is adapted to specific clinical tasks (e.g., lesion classification, malignancy prediction) through two primary approaches:

- Feature Extraction: Using the foundation model as a fixed feature extractor with a simple linear classifier trained on top.

- Fine-tuning: Updating the weights of the pretrained model on downstream tasks with limited labeled data [4].

This approach fundamentally addresses data scarcity by transferring knowledge acquired from large unlabeled datasets to specialized tasks with limited annotations, significantly reducing the demand for labeled training samples in downstream applications [4] [10].

Self-Supervised Learning Strategies for Medical Imaging

The efficacy of foundation models hinges on selecting appropriate SSL strategies tailored to medical imaging characteristics. Research systematically comparing various pretraining approaches has revealed performance differentials critical for implementation decisions:

- Contrastive Learning Methods: A modified version of SimCLR (a contrastive framework that learns representations by maximizing agreement between differently augmented views of the same image) has demonstrated superior performance for cancer imaging tasks, achieving a balanced accuracy of 0.779 (95% CI: 0.750-0.810) in lesion anatomical site classification, significantly outperforming (p < 0.001) other approaches [4].

- Comparative Performance: In systematic evaluations, SimCLR variants surpassed other state-of-the-art SSL approaches including SwAV (a clustering-based method that enforces consistency between cluster assignments for different augmentations) and NNCLR (which uses nearest neighbors in the latent space to create positive pairs) [4].

- Baseline Comparisons: Traditional autoencoder-based pretraining (which reconstructs original images from corrupted inputs) performed worst compared to modern contrastive SSL methods, highlighting the importance of selecting contemporary approaches [4].

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of different pretraining strategies evaluated on lesion anatomical site classification:

Table 1: Comparison of Self-Supervised Pretraining Strategies for Medical Imaging Foundation Models

| Pretraining Strategy | Balanced Accuracy | Mean Average Precision (mAP) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modified SimCLR | 0.779 (95% CI: 0.750-0.810) | 0.847 (95% CI: 0.750-0.810) | Contrastive learning with customized augmentations for medical images |

| SimCLR | 0.696 (95% CI: 0.663-0.728) | 0.779 (95% CI: 0.749-0.811) | Standard contrastive framework with augmented views |

| SwAV | 0.652 (95% CI: 0.619-0.685) | 0.737 (95% CI: 0.705-0.769) | Online clustering with swapped assignments |

| NNCLR | 0.631 (95% CI: 0.597-0.665) | 0.719 (95% CI: 0.686-0.752) | Nearest-neighbor positive pairs in latent space |

| Autoencoder | 0.589 (95% CI: 0.554-0.624) | 0.675 (95% CI: 0.640-0.710) | Image reconstruction objective |

Experimental Evidence and Performance Benchmarks

Technical Validation: In-Distribution Task Performance

The performance advantage of foundation models becomes particularly evident in scenarios with limited labeled data. In a technical validation study classifying lesion anatomical sites (using 3,830 lesions for training/tuning and 1,221 for testing), foundation model implementations demonstrated significant superiority over conventional approaches, especially as training data decreased [4].

Table 2: Foundation Model Performance on Lesion Anatomical Site Classification Under Limited Data Scenarios

| Training Data Percentage | Foundation Model Implementation | Balanced Accuracy | Performance Advantage Over Baselines |

|---|---|---|---|

| 100% (n=3,830) | Features + Linear Classifier | 0.792 | Significant improvement over all baselines (p < 0.05) |

| 100% (n=3,830) | Fine-tuned Foundation Model | 0.804 | Outperformed all baselines (p < 0.01) |

| 50% (n=2,526) | Features + Linear Classifier | 0.773 | Significant improvement over all baselines |

| 20% (n=1,010) | Features + Linear Classifier | 0.746 | Significant improvement over all baselines |

| 10% (n=505) | Features + Linear Classifier | 0.722 | Smallest performance decline (9%) with reduced data |

Notably, the feature extraction approach demonstrated remarkable robustness, maintaining 74.2% of its maximum performance with only 10% of training data, whereas conventional supervised models exhibited substantially steeper performance degradation [4]. This stability underscores the particular value of foundation models in real-world research settings where labeled data is invariably scarce.

Clinical Application: Out-of-Distribution Generalization

The true test of foundation models lies in their generalization capability to unseen data distributions and clinical tasks. In developing a diagnostic biomarker for predicting lung nodule malignancy using the LUNA16 dataset (507 nodules for training, 170 for testing), the fine-tuned foundation model achieved an AUC of 0.944 (95% CI: 0.907-0.972) and mAP of 0.953 (95% CI: 0.915-0.979), significantly outperforming (p < 0.01) most baseline implementations [4].

For prognostic biomarker development in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), foundation models demonstrated strong associations with underlying biology, particularly correlating with immune-related pathways, and exhibited enhanced stability to input variations including inter-reader differences and acquisition parameters [4] [10]. This biological relevance and robustness further validate the utility of foundation models for discovering clinically meaningful imaging biomarkers despite data limitations.

Implementation Protocols and Methodological Guidelines

Experimental Workflow for Foundation Model Development

The development and application of foundation models for cancer imaging follows a structured workflow encompassing data curation, model pretraining, and task-specific adaptation. The diagram below illustrates this comprehensive experimental pipeline:

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Data Curation and Preprocessing Protocol

Effective foundation models require diverse, large-scale medical imaging data for pretraining. The referenced research utilized 11,467 radiographic lesions from computed tomography (CT) scans encompassing diverse lesion types including lung nodules, cysts, and breast lesions [4] [10]. The preprocessing protocol involves:

- Volumetric Processing: Handling 3D CT volumes with consistent spatial normalization

- Intensity Standardization: Normalizing Hounsfield units across different scanner types

- Data Augmentation: Applying specialized transformations appropriate for medical images including:

- Controlled random cropping and resizing

- Rotation and flipping with anatomical constraints

- Noise injection and contrast variation within clinically plausible ranges

- Quality Control: Implementing rigorous exclusion criteria for corrupted or low-quality scans [4]

Self-Supervised Pretraining Implementation

The modified SimCLR framework implemented for cancer imaging foundation models includes these critical components:

- Positive Pair Generation: Creating multiple augmented views of the same lesion instance

- Encoder Network: Training a convolutional encoder (e.g., ResNet-50) to extract representations

- Projection Head: Mapping representations to a latent space where contrastive loss is applied

- Contrastive Loss Function: Using normalized temperature-scaled cross entropy (NT-Xent) to maximize agreement between positive pairs while repelling negative pairs

- Training Configuration: Optimizing with LARS optimizer, cosine learning rate decay, and global batch normalization [4]

Downstream Task Adaptation Methods

For applying pretrained foundation models to specific cancer imaging tasks, two primary adaptation strategies were systematically evaluated:

Feature Extraction Approach:

- Keeping the foundation model weights frozen

- Extracting feature representations from the penultimate layer

- Training a linear classifier (typically logistic regression or linear SVM) on these features

- Advantages: Computational efficiency, stability with very small datasets (<100 samples)

Fine-tuning Approach:

- Initializing task-specific models with foundation model weights

- Updating all parameters or only later layers using task-specific labels

- Employing reduced learning rates and early stopping to prevent catastrophic forgetting

- Advantages: Potential for higher peak performance with adequate data [4]

Successful implementation of foundation models for cancer imaging biomarker discovery requires access to specialized computational resources, datasets, and software frameworks. The table below details essential research reagents referenced in the foundational studies:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Foundation Model Development in Cancer Imaging

| Resource Category | Specific Resource | Function and Application | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Datasets | DeepLesion (11,467 lesions) | Foundation model pretraining; lesion anatomical site classification | Publicly available [4] [11] |

| Validation Datasets | LUNA16 | Lung nodule malignancy prediction (diagnostic biomarker) | Publicly available [4] [11] |

| Validation Datasets | LUNG1 & RADIO | Prognostic biomarker validation in NSCLC | Publicly available [4] [11] |

| Software Framework | MHub.ai | Containerized implementation for clinical deployment | Platform access [11] |

| Code Repository | GitHub (AIM Program) | Data preprocessing, model training, inference replication | Open source [11] |

| Benchmarking Tools | TumorImagingBench | Standardized evaluation across 6 datasets (3,244 scans) | Publicly released [12] |

| Radiomics Datasets | RadiomicsHub | 29 curated datasets (10,354 patients) for multi-center validation | Public repository [13] |

Comparative Analysis and Implementation Decision Framework

Performance Under Varying Data Constraints

The relative advantage of foundation models compared to conventional supervised approaches is inversely proportional to the amount of available labeled data. The diagram below illustrates this critical relationship and the recommended implementation decisions:

Integration with Existing Radiomics Workflows

Foundation models can be effectively integrated with traditional radiomics pipelines to enhance biomarker discovery:

- Complementary Feature Extraction: Deep learning features from foundation models can supplement hand-crafted radiomics features (shape, texture, intensity statistics) to create more comprehensive tumor profiles [13] [5].

- Multi-Modal Data Fusion: Foundation model embeddings can be combined with genomic, transcriptomic, and clinical data for multi-omics biomarker discovery, providing more holistic tumor characterization [5].

- Transfer Across Imaging Modalities: While typically pretrained on CT, foundation models can be adapted to MRI, PET, and multi-parametric imaging through transfer learning techniques [13].

- Standardized Validation Frameworks: Resources like TumorImagingBench enable systematic evaluation of foundation models across diverse cancer types and imaging protocols [12].

The critical challenge of scarce labeled medical datasets represents a fundamental constraint in cancer imaging biomarker discovery. Foundation models, pretrained through self-supervised learning on large-scale unlabeled imaging data, offer a transformative solution by significantly reducing the demand for annotated samples in downstream applications. Experimental evidence demonstrates that these models not only maintain robust performance in limited data scenarios but also enhance model stability, biological interpretability, and generalizability across clinical tasks.

The methodological frameworks, experimental protocols, and implementation guidelines presented in this technical guide provide researchers with practical resources to leverage foundation models in overcoming data scarcity constraints. As the field advances, the integration of these approaches with multi-institutional collaborations, standardized benchmarking, and explainable AI frameworks will accelerate the translation of imaging biomarkers into clinical practice, ultimately enhancing precision oncology and patient care.

How Foundation Models Learn Generalizable Representations from Unannotated Data

Foundation models represent a paradigm shift in artificial intelligence, characterized by their training on vast, diverse datasets through self-supervised learning (SSL) to acquire generalizable representations that adapt efficiently to various downstream tasks [14]. In cancer imaging biomarker discovery, these models directly address the critical bottleneck of annotated data scarcity by learning robust, transferable features directly from unannotated medical images [4] [15]. The capacity to learn from data without expensive, time-consuming manual labeling enables more rapid development of imaging biomarkers that can inform cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment response assessment.

These models fundamentally differ from conventional supervised approaches by leveraging the inherent structure and information within the data itself through pretext tasks, creating representations that capture underlying biological patterns rather than merely memorizing labeled examples [15] [14]. This technical guide explores the mechanisms through which foundation models achieve this capability, with specific emphasis on their application in cancer imaging research, providing researchers with both theoretical understanding and practical implementation frameworks.

Core Learning Mechanisms

Self-Supervised Learning Paradigms

Foundation models circumvent the need for manual annotations by employing self-supervised learning objectives that create supervisory signals directly from the data [14]. In medical imaging, this typically involves training models to solve pretext tasks that force the network to learn meaningful representations without human intervention. Common approaches include:

- Image Reconstruction: Training models to reconstruct missing or corrupted portions of medical images, forcing the network to learn anatomical and pathological priors to complete the task successfully [4] [14].

- Contrastive Learning: Learning representations by maximizing agreement between differently augmented views of the same image while minimizing agreement with other images in the dataset [4] [15]. This approach, exemplified by frameworks like SimCLR and its derivatives, has demonstrated particular effectiveness in medical imaging domains.

- Masked Image Modeling: Randomly masking portions of input images and training the model to predict the missing content, effectively learning contextual relationships within anatomical structures [14].

The learned representations capture fundamental characteristics of medical images that transcend specific diagnostic tasks, creating a foundation that can be efficiently adapted to various downstream applications with minimal labeled examples [4].

Architectural Foundations

The architectural implementations of foundation models for medical imaging typically employ:

- Convolutional Encoders: Traditional convolutional neural networks that process local spatial relationships effectively, particularly suited for the textural patterns found in medical images [4] [16].

- Vision Transformers: Self-attention based architectures that capture long-range dependencies in image data, potentially beneficial for understanding relationships between distant anatomical structures [15] [14].

- Multimodal Architectures: Models that process multiple data types simultaneously, such as combining imaging data with clinical notes or genomic information through cross-attention mechanisms [15] [14].

These architectures create representation spaces where semantically similar images (and image regions) are positioned proximally, enabling efficient knowledge transfer to new tasks through fine-tuning or linear probing approaches [4] [15].

Table 1: Common Self-Supervised Learning Approaches in Medical Imaging Foundation Models

| Method Category | Key Mechanism | Representative Architectures | Advantages in Medical Imaging |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contrastive Learning | Maximizes similarity between augmented views of same image | SimCLR, NNCLR, SwAV | Effective with diverse lesion appearances; robust to acquisition variations |

| Masked Modeling | Predicts masked image regions based on context | Masked Autoencoders (MAE), Vision Transformers | Learns anatomical context; strong spatial reasoning |

| Reconstruction-based | Reconstructs original input from transformed version | Autoencoders, Denoising Autoencoders | Learns complete anatomical representations; stable training |

Technical Implementation in Cancer Imaging

Experimental Framework for Cancer Biomarker Discovery

The implementation of foundation models for cancer imaging biomarker discovery follows a structured pipeline that leverages self-supervised pre-training followed by task-specific adaptation:

Phase 1: Large-Scale Pre-training In this foundational phase, models are trained on extensive, diverse datasets of unannotated medical images. For example, one cancer imaging foundation model was pre-trained on 11,467 radiographic lesions from 2,312 unique patients, encompassing multiple lesion types including lung nodules, cysts, and breast lesions [4]. The training employs a task-agnostic contrastive learning strategy that learns invariant features by maximizing agreement between differently augmented views of the same lesion.

Phase 2: Downstream Task Adaptation The pre-trained foundation model is then adapted to specific clinical tasks through:

- Linear Probing: Training a simple linear classifier on top of frozen features extracted from the foundation model, requiring minimal labeled data and computational resources [4].

- Fine-Tuning: Updating all or subset of the foundation model's weights using task-specific labeled data, typically achieving higher performance but requiring more resources [4] [17].

This approach was experimentally validated across multiple clinically relevant applications, including lesion anatomical site classification (technical validation), lung nodule malignancy prediction (diagnostic biomarker), and non-small cell lung cancer prognosis (prognostic biomarker) [4].

Quantitative Performance Evidence

Empirical studies demonstrate the effectiveness of foundation models in cancer imaging applications. In lesion anatomical site classification, a foundation model approach achieved a balanced accuracy of 0.804 (95% CI: 0.775–0.835) and mean average precision (mAP) of 0.857 (95% CI: 0.828–0.886), significantly outperforming conventional supervised approaches and other pre-training methods [4]. The advantage was particularly pronounced in limited data scenarios, with the foundation model maintaining robust performance even when training data was reduced to 10% of the original size [4].

In lung nodule malignancy prediction, foundation model fine-tuning achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.944 (95% CI: 0.907–0.972) and mAP of 0.953 (95% CI: 0.915–0.979), demonstrating strong generalization to out-of-distribution tasks [4]. Recent benchmarking studies evaluating ten different foundation models across six cancer imaging datasets further confirmed these findings, with top-performing models like FMCIB, ModelsGenesis, and VISTA3D showing consistent performance across diagnostic and prognostic tasks [17].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Foundation Models vs. Traditional Approaches in Cancer Imaging Tasks

| Task Domain | Dataset | Foundation Model Performance | Traditional/Baseline Performance | Key Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion Site Classification | 1,221 test lesions | 0.804 balanced accuracy | 0.696 balanced accuracy (Med3D) | Balanced Accuracy |

| Lung Nodule Malignancy | LUNA16 (170 test nodules) | 0.944 AUC | 0.917 AUC (Med3D fine-tuned) | Area Under Curve (AUC) |

| NSCLC Prognosis | NSCLC-Radiomics | 0.582 AUC (VISTA3D) | 0.449 AUC (CTClip) | Area Under Curve (AUC) |

| Renal Cancer Prognosis | C4KC-KiTS | 0.733 AUC (ModelsGenesis) | 0.463 AUC (CTFM) | Area Under Curve (AUC) |

Implementation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for developing and validating a foundation model for cancer imaging applications:

Foundation Model Development Workflow: The diagram illustrates the three-phase pipeline for developing cancer imaging foundation models, from self-supervised pre-training through task adaptation to clinical validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Foundation Model Development

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Imaging Datasets | 11,467 radiographic lesions [4], LUNA16 [17], NSCLC-Radiomics [17] | Pre-training and benchmarking | Diverse lesion types and anatomical sites improve model generalizability |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | TensorFlow [16], PyTorch, Caffe [16] | Model implementation and training | Open-source libraries with medical imaging extensions |

| Self-Supervised Algorithms | Modified SimCLR [4], SwAV [4], NNCLR [4] | Representation learning | Contrastive methods show superior performance in medical domains |

| Computational Infrastructure | GPU clusters, Cloud computing (AWS, GCP, Azure) | Model training and inference | Foundation models require significant computational resources for pre-training |

| Evaluation Metrics | AUC, Balanced Accuracy, Mean Average Precision [4] | Performance quantification | Multiple metrics provide comprehensive assessment of clinical utility |

Discussion and Future Directions

Foundation models represent a transformative approach to cancer imaging biomarker discovery by learning generalizable representations from unannotated data. The core innovation lies in their ability to capture fundamental patterns in medical images through self-supervised objectives, creating representations that transfer efficiently to diverse clinical tasks with minimal fine-tuning [4] [14].

The demonstrated performance advantages, particularly in limited data scenarios common in medical applications, highlight the potential of these models to accelerate the development and clinical translation of imaging biomarkers [4] [17]. Furthermore, foundation models show increased stability to input variations and stronger associations with underlying biology compared to traditional approaches [4].

Future research directions include developing more sophisticated multimodal foundation models that integrate imaging with clinical, genomic, and pathology data [15] [14], addressing challenges related to model interpretability and fairness [14], and establishing standardized benchmarking frameworks like TumorImagingBench [17] to enable reproducible comparison of foundation models across diverse cancer imaging applications. As these models continue to evolve, they hold significant promise for advancing precision oncology through more accessible, robust, and biologically-relevant imaging biomarkers.

Foundation models are revolutionizing the discovery of cancer imaging biomarkers by leveraging large-scale, self-supervised learning (SSL) on extensive unlabeled datasets. These models are characterized by their pre-training on broad data, which allows them to be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks with minimal task-specific supervision [18]. In the context of medical imaging, where large, annotated datasets are scarce and expensive to produce, this paradigm offers a transformative approach [4] [19]. The core advantages of foundation models align perfectly with the needs of this field: they enable more efficient model development, exhibit remarkable transferability across clinical tasks and cohorts, and significantly reduce the reliance on large annotated datasets. This technical guide explores these advantages within the framework of cancer imaging biomarker research, providing evidence from recent studies, detailed methodologies, and resources for the practicing scientist.

Efficiency: Performance Gains in Data-Limited Scenarios

A primary advantage of foundation models in cancer imaging is their ability to achieve high performance with limited labeled data for downstream tasks, making the development process highly efficient.

Quantitative Evidence of Data Efficiency

Research demonstrates that foundation models maintain robust performance even when fine-tuning data is severely restricted. The following table summarizes key findings from a foundational study that developed a model trained on 11,467 radiographic lesions [4].

Table 1: Performance of a Foundation Model on Lesion Anatomical Site Classification with Limited Data [4]

| Training Data Used | Number of Lesions | Foundation Model (Balanced Accuracy) | Conventional Supervised Model (Balanced Accuracy) | Performance Drop vs. Full Data (Foundation Model) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100% | 3,830 | 0.804 | 0.696 (Med3D fine-tuned) | Baseline |

| 50% | 1,915 | 0.781 | ~0.67 (estimated) | -2.9% |

| 20% | 766 | 0.752 | ~0.63 (estimated) | -6.5% |

| 10% | 383 | 0.732 | ~0.60 (estimated) | -9.0% |

In a diagnostic task for lung nodule malignancy prediction on the LUNA16 dataset, a fine-tuned foundation model achieved an Area Under the Curve (AUC) of 0.944, significantly outperforming other state-of-the-art pre-trained models [4]. This efficiency is crucial for investigating rare cancers or specific molecular subtypes where large, labeled datasets are impractical to assemble.

Experimental Protocol for Efficiency Validation

To systematically evaluate the data efficiency of a proposed foundation model, researchers typically follow this protocol:

- Foundation Model Pre-training: A convolutional encoder (e.g., ResNet) is trained using a self-supervised, task-agnostic contrastive learning strategy (e.g., a modified SimCLR framework) on a large, diverse dataset of unlabeled medical images (e.g., 11,467 CT lesions from 2,312 patients) [4] [19].

- Downstream Task Definition: Specific clinical tasks are selected, such as lesion anatomical site classification (in-distribution technical validation) or lung nodule malignancy prediction (out-of-distribution generalizability test) [4].

- Comparative Model Training:

- The foundation model is implemented in two ways: as a feature extractor with a simple linear classifier on top, and via fine-tuning the entire model.

- Baseline models are trained for comparison, including models trained from scratch in a supervised manner and other publicly available pre-trained models (e.g., Med3D, ModelsGenesis) [4] [17].

- Data Ablation Study: The downstream models are trained on progressively smaller subsets (e.g., 100%, 50%, 20%, 10%) of the available labeled data for the task.

- Performance Evaluation: Models are evaluated on a held-out test set using metrics such as balanced accuracy, mean Average Precision (mAP), and AUC. The relative performance drop for each model as training data is reduced is a key metric of efficiency [4].

Diagram 1: Workflow for Validating Foundation Model Efficiency.

Transferability: Generalizability Across Tasks and Cohorts

Transferability refers to a foundation model's ability to adapt to diverse clinical tasks, disease types, and patient populations, a critical feature for robust biomarker discovery.

Evidence of Cross-Task and Cross-Cohort Generalization

Benchmarking studies have systematically evaluated the transferability of multiple foundation models. The table below shows the performance of select models across different diagnostic and prognostic tasks [17].

Table 2: Transferability of Foundation Models Across Various Cancer Imaging Tasks [17]

| Foundation Model | LUNA16 (Diagnostic)\nAUC - Lung Nodule Malignancy | NSCLC-Radiomics (Prognostic)\nAUC - 2-Year Survival | C4KC-KiTS (Prognostic)\nAUC - 2-Year Survival (Renal) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMCIB [4] | 0.886 | 0.577 | N/A | Trained on diverse CT lesions |

| ModelsGenesis | 0.806 | 0.577 | 0.733 | Self-supervised learning on CTs |

| VISTA3D | 0.711 | 0.582 | N/A | Strong in prognostic tasks |

| Voco | 0.493 | 0.526 | N/A | Lower overall performance |

The data indicates that no single model is universally superior, but models pre-trained on diverse datasets (e.g., FMCIB, ModelsGenesis) consistently rank high across tasks. For instance, FMCIB excelled in diagnostic tasks, while VISTA3D showed relative strength in prognostic tasks [17]. This demonstrates that the features learned by these models are not task-specific but capture fundamental phenotypic characteristics of disease.

Protocol for Benchmarking Transferability

To assess the transferability of a foundation model, a rigorous benchmarking framework is essential:

- Model Selection: A suite of publicly available foundation models with varied architectures (CNN vs. Transformer), pre-training strategies (contrastive, generative), and source data (CT only, multi-modal) is selected [17] [18].

- Benchmark Curation: A benchmark comprising multiple public datasets (e.g., TumorImagingBench with 3,244 scans) is assembled. These datasets should span different clinical endpoints (diagnosis, prognosis), cancer types (lung, kidney, liver), and institutions to test generalizability [17].

- Embedding Extraction & Evaluation: For each dataset, embeddings (high-dimensional feature vectors) are extracted from the images using each foundation model. A simple classifier (e.g., k-nearest neighbors or a linear model) is then trained on these embeddings to predict the clinical endpoint [17] [20].

- Multi-Dimensional Analysis: Performance is evaluated not only on endpoint prediction (AUC) but also on robustness to input variations (test-retest reliability), saliency-based interpretability, and mutual similarity of the learned embeddings across models [17].

Reduced Reliance on Annotations: The Self-Supervised Learning Core

The reduced need for manual annotation is the foundational pillar enabling the efficiency and transferability of these models. This is achieved through self-supervised learning (SSL).

The Self-Supervised Pre-training Protocol

SSL allows models to learn powerful representations from data without manual labels by defining a "pretext task" that generates its own supervision from the data's structure. The core technical steps for pre-training a foundation model for cancer imaging are as follows [4] [18]:

- Data Curation: A large dataset of medical images (e.g., 11,467 CT lesions) is assembled without the need for detailed annotations. Only weak labels, such as the presence of a lesion, may be used [4] [11].

- Pretext Task - Contrastive Learning: A popular and effective SSL method is contrastive learning. In a framework like SimCLR:

- Augmentation: Each image in a batch is randomly transformed twice (e.g., via rotation, cropping, noise addition, color distortion), creating two correlated "views."

- Encoding: Both views are passed through a convolutional encoder network.

- Projection: The resulting embeddings are mapped to a latent space via a small projection head.

- Contrastive Loss: The learning objective is to maximize the agreement (similarity) between the two views of the same image while minimizing agreement with views from other images in the same batch [4] [18].

- Model Output: After pre-training, the projection head is discarded, and the encoder is used as the feature extractor for downstream tasks.

This process forces the model to learn robust, invariant features that are relevant to the image content itself, rather than features that are specific to a narrow labeled task.

Diagram 2: Self-Supervised Pre-training via Contrastive Learning.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Translating these concepts into practice requires a set of key resources. The following table details essential "research reagents" for working with foundation models in cancer imaging biomarker discovery.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Foundation Model-Based Biomarker Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Example(s) | Function and Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Models | FMCIB [4], ModelsGenesis [17], VISTA3D [17], CONCH (Pathology) [20] | Provides a starting point for downstream task adaptation, eliminating the need for costly pre-training from scratch. |

| Public Datasets | DeepLesion [11], LUNA16 [4], LUNG1 & RADIO [11], The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Serves as sources for pre-training data and, more importantly, as standardized benchmarks for evaluating model performance and transferability. |

| Code & Software Platforms | Project-lighter YAML configurations [11], MHub.ai platform [11], 3D Slicer Integration [11] | Provides reproducible code for training and inference, containerized models for ease of use, and integration with clinical research workflows. |

| Benchmarking Frameworks | TumorImagingBench [17], Pathology FM Benchmark [20] | Offers a curated set of tasks and datasets for the systematic evaluation and comparison of different foundation models, guiding model selection. |

Foundation models represent a paradigm shift in quantitative cancer imaging. Their core advantages—efficiency in low-data settings, exceptional transferability across clinical tasks, and a fundamentally reduced reliance on annotations—directly address the most significant bottlenecks in traditional biomarker discovery. By leveraging self-supervised learning on large datasets, these models learn a deep, generalized representation of disease phenotypes that can be efficiently adapted with minimal fine-tuning. As benchmarking studies show, this leads to more robust and accurate imaging biomarkers. The availability of pre-trained models, public datasets, and software platforms is now empowering researchers to harness these advantages, accelerating the translation of AI-derived biomarkers from research into clinical practice and drug development.

Positioning Foundation Models within the Broader AI Landscape in Oncology

Foundation models represent a paradigm shift in artificial intelligence (AI) for oncology. These models are characterized by their training on vast, broad datasets using self-supervised learning (SSL), which enables them to serve as versatile base models for a wide array of downstream clinical tasks without requiring task-specific architectural changes [4]. In cancer care, where labeled medical data is notoriously scarce and expensive to produce, foundation models offer a transformative solution by learning generalizable, task-agnostic representations from extensive unannotated data [4] [11]. These models excel particularly in reducing the demand for large labeled datasets in downstream applications, making them exceptionally valuable for specialized oncological tasks where large annotated datasets are often unavailable [4].

The positioning of foundation models within the broader AI landscape marks a critical evolution from narrow, single-task models toward generalist AI systems capable of adapting to multiple clinical challenges. Traditional supervised deep learning approaches in oncology have typically required large labeled datasets for each specific task—such as tumor detection, classification, or prognosis prediction—limiting their applicability in data-scarce scenarios [4]. Foundation models overcome this limitation through pretraining on diverse, unlabeled datasets, capturing fundamental patterns of cancer imaging characteristics that can be efficiently transferred to various downstream applications with minimal task-specific training [4] [21]. This approach mirrors the success of foundation models in other domains, such as natural language processing, but applies these principles to the complex, multimodal world of oncology [4].

Comparative Advantages Over Traditional AI Approaches

Foundation models demonstrate significant advantages over conventional supervised learning and other pretrained models, particularly in scenarios with limited data availability. In direct performance comparisons, foundation models consistently outperform traditional approaches across multiple cancer imaging tasks [4].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI Approaches in Cancer Imaging Tasks

| Task Description | Model Type | Performance Metrics | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lesion Anatomical Site Classification [4] | Foundation (fine-tuned) | mAP: 0.857 (95% CI 0.828-0.886) | Significantly outperformed all baseline methods (p<0.05) |

| Foundation (features) + Linear classifier | mAP: 0.847 (95% CI 0.750-0.810) | Outperformed compute-intensive supervised training | |

| Lung Nodule Malignancy Prediction [4] | Foundation (fine-tuned) | AUC: 0.944 (95% CI 0.907-0.972) | Significant superiority (p<0.01) over most baselines |

| Traditional supervised | AUC: <0.917 | Lower performance compared to foundation approaches | |

| Anatomical Site Classification with 10% Data [4] | Foundation model | Smallest performance decline (9% balanced accuracy) | Superior data efficiency and robustness in limited data scenarios |

The stability and biological relevance of foundation models further distinguish them from traditional approaches. These models demonstrate increased robustness to input variations and show strong associations with underlying biology, as validated through deep-learning attribution methods and gene expression data correlations [4]. This biological grounding enhances the clinical relevance of the derived imaging biomarkers and supports their potential for discovery of novel cancer characteristics not previously captured by handcrafted radiomic features or supervised deep learning approaches [4].

Technical Architectures and Methodological Approaches

Self-Supervised Learning Strategies for Pretraining

The effectiveness of foundation models in oncology stems from sophisticated self-supervised learning approaches that enable the model to learn meaningful representations without explicit manual annotations. Several SSL strategies have been evaluated for cancer imaging applications, with contrastive learning approaches demonstrating particular effectiveness [4].

Table 2: Self-Supervised Learning Strategies for Oncological Foundation Models

| Pretraining Strategy | Key Mechanism | Performance in Anatomical Site Classification | Relative Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Modified SimCLR [4] | Contrastive learning with task-specific modifications | Balanced Accuracy: 0.779 (95% CI 0.750-0.810) | Superior to all other approaches (p<0.001) |

| Standard SimCLR [4] | Instance discrimination via contrastive loss | Balanced Accuracy: 0.696 (95% CI 0.663-0.728) | Second-best performing approach |

| SwAV [4] | Online clustering with swapped predictions | Performance lower than SimCLR variants | Moderate performance |

| NNCLR [4] | Contrastive learning with nearest-neighbor positives | Performance lower than SimCLR variants | Moderate performance |

| Autoencoder [4] | Image reconstruction | Lowest performance | Outperformed by contrastive SSL methods |

The modified SimCLR approach, which builds upon the standard SimCLR framework with domain-specific adaptations for medical imaging, has demonstrated remarkable robustness when training data is limited. When evaluated with progressively reduced training data (50%, 20%, and 10% of original dataset), this approach showed the smallest decline in performance metrics—only 9% reduction in balanced accuracy and 12% in mean average precision when reducing training data from 100% to 10% [4]. This robustness to data scarcity is particularly valuable in clinical oncology settings where collecting large annotated datasets is challenging.

Multimodal Architecture Integration

Advanced foundation models in oncology are increasingly embracing multimodal architectures that integrate diverse data types to enhance clinical utility. The Multimodal transformer with Unified maSKed modeling (MUSK) represents a cutting-edge vision-language foundation model trained on both pathology images and clinical text [22]. This model was pretrained on 50 million pathology images from 11,577 patients and one billion pathology-related text tokens using unified masked modeling, followed by additional pretraining on one million pathology image-text pairs to align visual and language features [22]. This architecture enables the model to leverage complementary information from both imaging and clinical narratives, supporting tasks ranging from image-text retrieval to biomarker prediction and outcome forecasting [22].

Diagram 1: Multimodal Foundation Model Architecture

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

Foundation Model Development Protocol

The development of a robust foundation model for cancer imaging requires a systematic approach to data curation, model training, and validation. A representative protocol, as implemented by Pai et al., involves several critical phases [4] [11]:

Phase 1: Data Curation and Preprocessing

- Collect comprehensive dataset of radiographic lesions (e.g., 11,467 lesions from 2,312 unique patients) [4]

- Include diverse lesion types: lung nodules, cysts, breast lesions, and numerous others [4]

- Implement standardized preprocessing: image normalization, resampling to consistent resolution, and data augmentation [4]

- Split data into training, validation, and test sets, ensuring patient-wise separation to prevent data leakage [11]

Phase 2: Self-Supervised Pretraining

- Implement modified SimCLR framework with domain-specific augmentations [4]

- Train convolutional encoder using contrastive learning objective

- Optimize using Adam optimizer with learning rate warmup and cosine decay

- Monitor training progress using contrastive loss and representation quality metrics

Phase 3: Downstream Task Adaptation

- Evaluate two implementation approaches: feature extraction with linear classifier and full fine-tuning [4]

- For feature extraction: freeze foundation model weights, train linear classifier on extracted features

- For fine-tuning: initialize with foundation model weights, fine-tune entire architecture on downstream task

- Compare against supervised baselines and other pretrained models (Med3D, Models Genesis) [4]

Phase 4: Comprehensive Validation

- Technical validation on in-distribution tasks (e.g., lesion anatomical site classification) [4]

- Generalizability assessment on out-of-distribution tasks (e.g., malignancy prediction on external datasets) [4]

- Robustness evaluation through test-retest and inter-reader consistency analyses [4]

- Biological relevance assessment via correlation with genomic data [4]

Benchmarking and Performance Evaluation

Rigorous benchmarking is essential for evaluating foundation models in oncology. The TumorImagingBench framework provides a standardized approach, curating multiple public datasets (3,244 scans) with varied oncological endpoints to assess model performance across diverse clinical contexts [12]. This evaluation extends beyond traditional endpoint prediction to include robustness to clinical variability, saliency-based interpretability, and comparative analysis of learned embedding representations [12].

Diagram 2: Experimental Validation Workflow

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Oncological Foundation Models

| Resource Category | Specific Tool/Dataset | Function/Purpose | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public Datasets | DeepLesion [11] | RECIST-bookmarked lesions for pretraining and anatomical site classification | Openly accessible |

| LUNA16 [4] [11] | Lung nodules for diagnostic biomarker development | Publicly available | |

| LUNG1 and RADIO [11] | NSCLC datasets for prognostic biomarker validation | Publicly available | |

| Computational Frameworks | MHub.ai [11] | Containerized, ready-to-use model implementation supporting various input workflows | Platform access |

| 3D Slicer Integration [11] | Clinical integration and application framework | Open source | |

| Project-lighter [11] | Training and replication via customizable YAML configurations | GitHub repository | |

| Benchmarking Tools | TumorImagingBench [12] | Curated benchmark with 3,244 scans across 6 datasets for systematic evaluation | Publicly released code and datasets |

| Model Architectures | Modified SimCLR [4] | Contrastive SSL framework optimized for medical imaging | Code available in repository |

| MUSK [22] | Vision-language foundation model for pathology | GitHub repository with model weights | |

| Validation Resources | Molecular Data Integration [4] | Gene expression correlation analysis for biological validation | Dependent on specific institutional resources |

Implementation Pathways and Clinical Translation

The translation of foundation models from research to clinical application follows multiple implementation pathways, each with distinct advantages for specific clinical scenarios. Two primary approaches have demonstrated significant utility: using the foundation model as a fixed feature extractor with a linear classifier, and full fine-tuning of the model for specific downstream tasks [4].

The feature extraction approach provides substantial computational benefits with reduced memory requirements and training time, while still achieving performance comparable to or better than compute-intensive supervised training [4]. This method is particularly valuable for rapid prototyping and applications with limited computational resources. In contrast, the fine-tuning approach typically achieves the highest performance on specific clinical tasks but requires more computational resources and careful management of training dynamics to prevent catastrophic forgetting of the pretrained representations [4].

For clinical deployment, platforms like MHub.ai provide containerized, ready-to-use implementations that support various input workflows and integration with clinical systems such as 3D Slicer [11]. This approach significantly lowers the barrier for both academic and clinical researchers to leverage foundation models without requiring deep expertise in model architecture or training procedures. The availability of these models through simple package installations and standardized APIs further accelerates their adoption in diverse research and clinical settings [11].

The demonstrated performance of foundation models in predicting clinically relevant endpoints—including lesion characterization, malignancy prediction, and cancer prognosis—combined with their robustness to input variations and association with underlying biology, positions them as powerful tools for accelerating the discovery and translation of imaging biomarkers into clinical practice [4]. As these models continue to evolve and validate across diverse patient populations and clinical contexts, they hold tremendous potential to enhance precision oncology and improve patient care through more accurate, efficient, and biologically grounded imaging biomarkers.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Foundation Models for Oncology Biomarkers

The emergence of foundation models represents a paradigm shift in medical artificial intelligence (AI), offering unprecedented capabilities for cancer imaging biomarker discovery. These models, characterized by large-scale architectures trained on vast amounts of unannotated data, serve as versatile starting points for diverse downstream tasks through transfer learning. Within this transformative context, researchers face a critical architectural decision: convolutional encoders versus transformer-based models. This choice fundamentally influences model performance, data efficiency, computational requirements, and ultimately the clinical translation of imaging biomarkers.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) have long served as the workhorse of medical image analysis, leveraging their innate inductive biases for processing spatial hierarchies in imaging data. In contrast, Vision Transformers (ViTs) have recently emerged as powerful competitors, utilizing self-attention mechanisms to capture global contextual information. For foundation models aimed at cancer imaging biomarkers—which must extract meaningful, reproducible, and biologically relevant signatures from radiographic data—this architectural choice carries significant implications for discovery potential. This technical guide provides an in-depth analysis of both architectures within this specific research context, offering evidence-based insights, comparative evaluations, and practical implementation frameworks to inform researcher decisions.

Architectural Fundamentals and Key Properties

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

CNNs process medical images through a hierarchical series of convolutional layers, pooling operations, and nonlinear activations. The core operation is convolution, where filters slide across input images to detect local patterns through shared weights. This design incorporates strong inductive biases particularly suited to medical imagery: translation invariance, spatial locality, and hierarchical feature learning. These properties enable CNNs to efficiently recognize patterns like textures, edges, and shapes that are fundamental to radiographic interpretation [23].

The architectural properties of CNNs make them particularly well-suited for medical imaging tasks where local tissue characteristics and spatial patterns provide diagnostic value. Their parameter sharing across spatial domains confers significant computational efficiency, while their progressive receptive field expansion through layered convolutions enables learning of complex feature hierarchies from local pixels to global structures [23]. However, this localized processing approach presents limitations in capturing long-range dependencies across image regions—a potential drawback for cancer imaging contexts where relationships between distant anatomical structures or distributed tumor characteristics may carry prognostic significance.

Vision Transformers (ViTs)

Vision Transformers fundamentally reimagine image processing by treating images as sequences of patches. Unlike CNNs' local processing, ViTs utilize self-attention mechanisms that compute pairwise interactions between all patches in an image, enabling direct modeling of global dependencies. The core operation is scaled dot-product attention, which dynamically weights the influence of different image regions on each other [23].

This architecture provides several distinctive properties valuable for cancer imaging biomarker discovery. The global receptive field available from the first layer allows ViTs to capture relationships between distant anatomical structures without the progressive field expansion required in CNNs. The self-attention mechanism also enables dynamic feature weighting based on content, potentially identifying clinically relevant image regions without explicit spatial priors [24]. However, these capabilities come with substantial computational requirements and typically demand larger training datasets to reach optimal performance—a significant consideration in medical imaging domains where annotated data may be limited [23].

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of CNN and Transformer Architectures

| Property | Convolutional Encoders | Transformer-Based Models |

|---|---|---|

| Core Operation | Convolution with localized filters | Self-attention between all image patches |

| Receptive Field | Local initially, expands through depth | Global from the first layer |

| Inductive Bias | Strong (translation invariance, locality) | Weak (minimal built-in assumptions) |

| Parameter Efficiency | High (weight sharing across spatial dimensions) | Lower (attention weights scale with input) |

| Data Efficiency | Generally requires less training data | Typically requires large-scale pre-training |

| Long-Range Dependency | Limited, requires many layers | Strong, captured directly via self-attention |

| Computational Complexity | O(n) for n input pixels | O(n²) for n input patches |

Performance Comparison in Medical Imaging Tasks

Classification and Diagnostic Biomarker Development

Both architectures have demonstrated strong performance in diagnostic classification tasks, though their relative advantages depend on specific task requirements and data constraints. In cancer imaging applications, CNNs have shown particular strength in scenarios with limited training data. A foundational study developing a CNN-based foundation model for cancer imaging biomarkers achieved outstanding performance across multiple clinical tasks, including nodule malignancy prediction with an AUC of 0.944 (95% CI 0.907-0.972) on the LUNA16 dataset [4]. This model, pre-trained on 11,467 radiographic lesions through self-supervised learning, significantly outperformed conventional supervised approaches, especially when fine-tuning data was limited [4] [11].

Comparative analyses reveal a more nuanced picture of relative strengths. A 2024 systematic review noted that transformer-based models frequently achieve superior performance compared to conventional CNNs on various medical imaging tasks, though this advantage often depends on appropriate pre-training [23]. However, a 2025 comparative analysis across chest X-ray pneumonia detection, brain tumor classification, and skin cancer melanoma detection found task-specific advantages: ResNet-50 (CNN) achieved 98.37% accuracy on chest X-rays, while DeiT-Small (Transformer) excelled in brain tumor detection (92.16% accuracy), and EfficientNet-B0 (CNN) led in skin cancer classification (81.84% accuracy) [25]. This suggests that optimal architecture selection may be problem-dependent rather than universally prescribed.

Segmentation and Morphometric Biomarker Extraction

Medical image segmentation represents a critical task for cancer imaging biomarker discovery, enabling precise quantification of tumor morphology, volume, and tissue characteristics. Traditional U-Net architectures based on CNNs have dominated this domain, but recent transformer-based approaches are showing competitive or superior performance in specific contexts.

The TransUNet framework, which integrates transformers into U-Net architectures, has demonstrated significant improvements in challenging segmentation tasks. In multi-organ abdominal CT segmentation, TransUNet achieved a 1.06% average Dice improvement compared to the highly competitive nn-UNet, while showing more substantial gains (4.30% average Dice improvement) in pancreatic tumor segmentation—a particularly challenging task involving small targets [26]. The study attributed these improvements to the transformer's ability to capture global contextual relationships that help resolve ambiguous boundaries and identify small structures.

Hybrid architectures that strategically combine both approaches are emerging as particularly powerful solutions. The AD2Former network, incorporating alternate CNN and transformer blocks in the encoder alongside a dual-decoder structure, demonstrated strong performance in capturing target regions with fuzzy boundaries in multi-organ and skin lesion segmentation tasks [27]. This design allows mutual guidance between local and global feature extraction throughout the encoding process rather than simply cascading the two modalities.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Medical Imaging Tasks

| Task | Dataset | Best-Performing CNN Model | Best-Performing Transformer Model | Performance Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nodule Malignancy Prediction | LUNA16 | Foundation CNN (AUC: 0.944) | Not specified | CNN superior [4] |

| Chest X-ray Classification | Chest X-ray | ResNet-50 (Accuracy: 98.37%) | ViT-Base (Accuracy: Not specified) | CNN superior [25] |

| Brain Tumor Classification | Brain Tumor | EfficientNet-B0 (Accuracy: Not specified) | DeiT-Small (Accuracy: 92.16%) | Transformer superior [25] |

| Multi-organ Segmentation | Synapse | nn-UNet (Dice: Baseline) | TransUNet (Dice: +1.06%) | Transformer superior [26] |

| Pancreatic Tumor Segmentation | Pancreas CT | nn-UNet (Dice: Baseline) | TransUNet (Dice: +4.30%) | Transformer superior [26] |

| TIL Level Prediction | Breast US | DenseNet121 (AUC: 0.873) | Vision Transformer (AUC: Not specified) | Comparable [28] |

Practical Implementation Considerations

Data Requirements and Pre-training Strategies

The data efficiency of architectural choices represents a critical consideration for cancer imaging biomarker discovery, where annotated datasets are typically limited. CNNs generally demonstrate superior performance in data-scarce scenarios due to their built-in inductive biases. The cancer imaging foundation model developed using a convolutional encoder maintained robust performance even when downstream training data was reduced to just 10% of the original dataset, declining by only 9% in balanced accuracy compared to significantly larger drops in other approaches [4].

Vision Transformers typically require substantial pre-training to compensate for their weaker inductive biases. As noted in a comparative review, "pre-training is important for transformer applications" in medical imaging [23]. However, once adequately pre-trained, ViTs can excel in transfer learning scenarios. Self-supervised learning (SSL) has emerged as a particularly powerful strategy for both architectures in medical imaging, reducing dependency on scarce manual annotations. The convolutional foundation model for cancer imaging was pre-trained using a modified SimCLR framework, a contrastive SSL approach that significantly outperformed autoencoder and other SSL strategies [4].

Computational Requirements and Model Efficiency

Computational resources represent a practical constraint in architectural selection. CNNs generally offer greater computational efficiency, with linear scaling relative to input size versus the quadratic scaling of transformer self-attention. This difference becomes particularly significant with high-resolution 3D medical images common in oncology applications like CT and MRI [23].

Efforts to optimize transformer efficiency for medical imaging include patchified processing, hierarchical architectures, and hybrid designs. The Swin Transformer introduced a windowed attention mechanism that reduces computational complexity while maintaining global modeling capabilities [29]. Similarly, the TransUNet framework processes feature maps from a CNN backbone rather than raw image patches, improving efficiency while leveraging global context [26]. For large-scale foundation model development and deployment, these efficiency considerations directly impact feasibility, iteration speed, and clinical translation potential.

Robustness and Interpretability

Model robustness to technical variations in image acquisition is essential for clinically viable imaging biomarkers. The convolutional foundation model for cancer imaging demonstrated superior stability to input variations compared to supervised approaches [4]. Transformers may offer advantages in certain robustness metrics due to their global processing, though their performance can be more variable across domain shifts [23].

Interpretability remains challenging for both architectures, though both have established visualization techniques. CNNs typically utilize activation mapping approaches like Grad-CAM to highlight influential image regions [28]. Transformers can leverage attention weights to visualize patch interactions, though interpreting these complex interaction patterns remains an active research area [23]. For cancer biomarker discovery, biological plausibility and association with underlying pathology are crucial validation steps, with the CNN foundation model demonstrating strong associations with gene expression data [4].

Integrated Frameworks and Future Directions

Hybrid Architectures

The complementary strengths of CNNs and Transformers have motivated numerous hybrid architectures that strategically integrate both approaches. These designs aim to preserve local feature precision while incorporating global contextual understanding. The AD2Former exemplifies this trend with an alternate encoder that enables real-time interaction between local and global information, allowing both to mutually guide learning [27]. This architecture demonstrated particular strength in capturing fuzzy boundaries and small targets in challenging segmentation tasks.

Other integration strategies include parallel pathways, sequential arrangements, and attention-enhanced convolutional blocks. The TransUNet offers flexible configuration options, allowing researchers to implement transformer components in the encoder only, decoder only, or both, depending on task requirements [26]. Empirical results suggest that the encoder benefits are most pronounced for modeling interactions among multiple abdominal organs, while transformer decoders show particular strength in handling small targets like tumors [26].

Foundation Models for Cancer Imaging

Foundation models represent a particularly promising application for these architectural considerations. The successful implementation of a CNN-based foundation model for cancer imaging biomarkers demonstrates the potential of this approach [4] [11]. This model, pre-trained on 11,467 diverse radiographic lesions, facilitated efficient adaptation to multiple downstream tasks including lesion anatomical site classification, lung nodule malignancy prediction, and prognostic biomarker development for non-small cell lung cancer [4].

Ongoing benchmarking efforts like TumorImagingBench are systematically evaluating diverse foundation model architectures for quantitative cancer imaging phenotypes [12]. Such initiatives provide critical empirical evidence to guide architectural selection for specific oncological applications and imaging modalities. As the field progresses, task-specific rather than universally optimal architectural choices are likely to emerge, informed by comprehensive comparative evaluations.

Figure 1. Architectural Workflows for Cancer Imaging Foundation Models

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Self-Supervised Pre-training Framework

The development of foundation models for cancer imaging typically begins with self-supervised pre-training on large-scale unannotated datasets. The following protocol, adapted from successful implementations, provides a methodological framework for architectural comparison:

Data Curation and Preparation:

- Collect comprehensive dataset of radiographic lesions (e.g., 11,467 lesions from 2,312 patients)

- Ensure diversity in lesion types, anatomical locations, and imaging characteristics

- Standardize image preprocessing: resampling to consistent resolution, intensity normalization, and data augmentation (random cropping, flipping, rotation, contrast adjustment)

Self-Supervised Learning Implementation:

- For CNN architectures: Implement contrastive learning framework (e.g., modified SimCLR)

- For Transformer architectures: Consider masked autoencoding or contrastive approaches

- Train with balanced batch sampling to ensure representation of diverse lesion types

- Optimize using Adam or LAMB optimizer with cosine learning rate decay

Validation and Model Selection:

- Evaluate learned representations through linear probing on held-out validation tasks

- Assess training stability and convergence metrics

- Select optimal checkpoint based on representation quality and training efficiency